Abstract

Gonadal hormones modulate behavioral responses to sexual stimuli, and communication signals can also modulate circulating hormone levels. In several species, these combined effects appear to underlie a two-way interaction between circulating gonadal hormones and behavioral responses to socially salient stimuli. Recent work in songbirds has shown that manipulating local estradiol levels in the auditory forebrain produces physiological changes that affect discrimination of conspecific vocalizations and can affect behavior. These studies provide new evidence that estrogens can directly alter auditory processing and indirectly alter the behavioral response to a stimulus. These studies show that: 1. Local estradiol action within an auditory area is necessary for socially-relevant sounds to induce normal physiological responses in the brains of both sexes; 2. These physiological effects occur much more quickly than predicted by the classical time-frame for genomic effects; 3. Estradiol action within the auditory forebrain enables behavioral discrimination among socially-relevant sounds in males; and 4. Estradiol is produced locally in the male brain during exposure to particular social interactions. The accumulating evidence suggests a socio-neuro-endocrinology framework in which estradiol is essential to auditory processing, is increased by a socially relevant stimulus, acts rapidly to shape perception of subsequent stimuli experienced during social interactions, and modulates behavioral responses to these stimuli. Brain estrogens are likely to function similarly in both songbird sexes because aromatase and estrogen receptors are present in both male and female forebrain. Estrogenic modulation of perception in songbirds and perhaps other animals could fine-tune male advertising signals and female ability to discriminate them, facilitating mate selection by modulating behaviors. Keywords: Estrogens, Songbird, Social Context, Auditory Perception

Although estrogens have long been recognized for their role in facilitating female behavioral responses to sexual stimuli, there has been a recent explosion of information that suggests a significant estrogenic influence on brain structures that serve learning and memory processes in both sexes. The 1990s brought a series of studies which showed that cellular effects of estrogens could mediate changes in memory function. For example, the hippocampus, a structure that is important in memory formation, was shown to undergo morphological changes in response to naturally fluctuating or experimentally manipulated estrogens in females, and electrophysiological responses in hippocampal slice preparations were changed when estradiol (specifically, 17β-estradiol; E2) was added to the bath (Gould et al., 1990; Woolley, 1992; Woolley et al., 1996; Wong and Moss, 1992). Systemic injection and intra-hippocampal estradiol infusion improved performance on learning tasks in rodents (Packard, 1998). These kinds of results support the proposal that memory deficits in perimenopausal and/or menopausal women might result from estradiol deficiency (for discussion see Frick, 2009; Shors, 2005). If so, some form of estrogen therapy could safeguard against memory loss. In addition, immunohistochemical and electrophysiological experiments have identified both classical (ERα, ERβ) and novel (e.g. ERx, GPR-30) estrogen receptors on neuronal membranes, allowing estrogens to influence cellular physiology rapidly through non-genomic mechanisms, in addition to the classical steroid mechanism in which an estrogen binds to its intra-cellular receptors and ultimately influences gene transcription (reviewed in Woolley, 2007; McEwen, 2001; Mermelstein and Micevych, 2008; Roepke et al., 2011; Kelly and Levin, 2001). Our understanding of the proximate effects of estrogens on behavior has been advanced (and complicated) by the discovery of classical, and novel estrogen receptors in the brains of mammalian (McEwen, 2001; Simerly et al., 1990; Toran-Allerand, 2003; Taylor and Al-Azzawi, 2000; Kuiper et al., 1998) and non-mammalian species, including birds (Gahr, 2001; Ball et al., 2002; Saldanha et al., 2000), frogs (Chakroborty and Burmeister, 2010), and fish (Forlano et al., 2005; Pellegrini et al., 2005). In addition, the enzyme aromatase, which converts androgens to estrogens, also has been identified within male and female brains of many species (Callard et al., 1978; Saldanha et al., 2000; Beigon et al., 2010; Azcotia et al.; 2011; Forlano et al., 2005; Balthazart et al., 1996), allowing for the possibility that estrogens could be produced and act on nearby receptors to influence brain activity (Saldanha et al., 2011). Recent anatomical and physiological studies (Charitidi and Canlon, 2010) have also located intra- and extra-nuclear ERs at all levels of the auditory system from the inner hair cells to the cortex, encouraging research to discover their function in these auditory structures.

Decades of work revealing estrogenic influences on behavior, its diverse mechanisms and sites of action, now provide an exciting opportunity to determine how estradiol and other estrogens modulate brain function and alter behavioral responses to stimuli. Even more challenging is to ask how estrogenic interactions influence behaviors occurring within a realistic ethological context and time frame. Thirty years ago, experimenters in this field proposed the idea that hormones could modulate behaviors on a minute-to-minute basis (Harding, 1981; Wingfield, 1985). In addition, hormones can act in a region/steroid-specific manner (Adkins-Regan, 1981), thus enabling an animal to alter its behavior to changing conditions in the environment and ultimately ensure survival or reproduction.

In particular, gonadal hormones increase during some social interactions. For example, circulating androgens in males of several species increase within minutes of exposure to a conspecific female (see Harding, 1981). In male song sparrows, a territorial songbird species in which song functions in territorial defense, testosterone increases following exposure to conspecific song (Wingfield, 1985). Other examples of socially induced hormonal fluctuations are found among fish species (e.g., toadfish and midshipman fish) in which the males emit calls to attract females and defend their territory (reviewed in Bass, 2008). In male toadfish, playback of conspecific male calls induces increases in androgens and call frequency within minutes (Remage-Healey and Bass, 2005, 2006). These rapid fluctuations in steroid hormones occur in addition to longer, seasonal fluctuations, for which conversion to estrogens in specific brain areas is necessary to activate male copulatory behavior in some species (see Adkins-Regan, 1981; Balthazart et al., 2009).

One example of how an estrogen can act within a specific brain area to induce a specific change in behavioral response is illustrated by a careful set of experiments performed over many years by Pfaff and colleagues (reviewed in Pfaff et al., 2008). His group demonstrated that estrogenic action within the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) is necessary for and facilitates the female lordosis response to male mounting attempts in rodents; estradiol implants within the VMH elicit the response, lesions to this area prevent it (Pfaff and Sakuma, 1979); and a subset of these VMH neurons project to the central grey nucleus of the midbrain, an area whose stimulation elicits lordosis (Sakuma and Pfaff, 1980). From a functional perspective, estradiol could influence a female’s behavioral response by binding to cells within the hypothalamus, inducing changes in the motor response for receptivity and, as Pfaff et al. (2008) suggest, establish coherency between the behavioral response to a sexually relevant stimulus and the reproductive capability of the body within a given time period.

Enriching the wide and comparative literature documenting estrogenic influences on reproductive behaviors (see Schlinger, 1998; Weil et al., 2010; Charlier, 2009), investigation of the estrogen-brain-behavior connection in a songbird model lends credence to the idea that hormones can influence behavior not only at the limbic level, but also by acting rapidly within a specific area of the auditory system to directly alter auditory processing and indirectly alter an animal’s behavioral response to a given stimulus. This work identifies estrogens, specifically estradiol, as essential to auditory discrimination and the behavioral preference for certain sounds. Furthermore, changes in neurophysiology and behavior are modulated by estradiol produced within the brain itself. The studies reviewed here show that: 1. Local estradiol action within an auditory area is necessary for socially-relevant sounds to induce normal physiological responses in the brains of both sexes; 2. These physiological changes occur much more quickly than predicted by the classical time frame for genomic effects; 3. Estradiol action within this auditory area enables behavioral discrimination among socially-relevant sounds in males; and 4. Local estradiol production occurs in males during exposure to particular social interactions. The following sections present a brief overview of song function in songbirds, the properties of an auditory area involved in perceiving this social signal, and summarize the most recent studies investigating estradiol’s role in auditory perception.

Female Mate Choice, Male Advertisements, and the Importance of Discrimination

Whereas many mammalian species rely on odor as a primary mode of communication among conspecifics (e.g., rodents scent-mark to indicate dominance over a territory and this behavior is abolished in presence of predatory odors; see Arakawa et al., 2008), songbirds rely on auditory signals (sometimes combined with visual displays) and communicate with each other through a variety of calls and songs (Zann, 1996; Williams, 2008). In most migratory songbirds, only the males sing; males learn their songs from an adult male “tutor” and will sing in a variety of social contexts including courtship and territory defense (e.g., court a female by singing to her or defend his territory by singing to other males; Zann, 1996; Jarvis et al., 1998; Nowicki and Searcy, 2004). As a trait that is sexually selected (see Nowicki and Searcy, 2004), a male’s song advertises an “honest” signal of mate quality and females select their mate (sometimes for life) based on song preferences. Females will respond to males singing a song they prefer (Brenowitz, 1991; Zann, 1996) with approach behaviors and a series of movements called copulation solicitation displays (CSDs). This receptive behavior (comparable to lordosis in rodents) has been adopted as an assay to determine behavioral preference for different song types; it is modulated by estrogen and reproductive state. Female canaries that are photostimulated by increasing the number of daylight hours to increase estradiol perform CSDs to playback of male songs, whereas females concurrently treated with an estrogen-synthesis inhibitor do not exhibit CSDs during the course of the treatment, and show delays in displaying and egg-laying after treatment has ended (Leboucher et al., 1998). Estradiol treatment administered peripherally induces receptive behavior in female birds in species that ordinarily do not exhibit CSDs to song stimulation in captivity (e.g. zebra finches; Vyas et al., 2008). For male advertisement songs to be effective, females must perceive this signal, then discriminate the characteristics that distinguish a quality mate from a poor one, and finally respond appropriately to the eliciting stimulus.

NCM: Estrogen-Receptor and Aromatase Rich, Important for Discrimination of Sounds

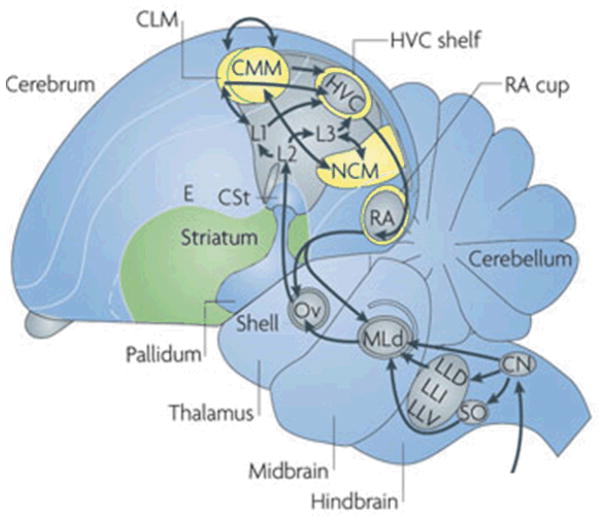

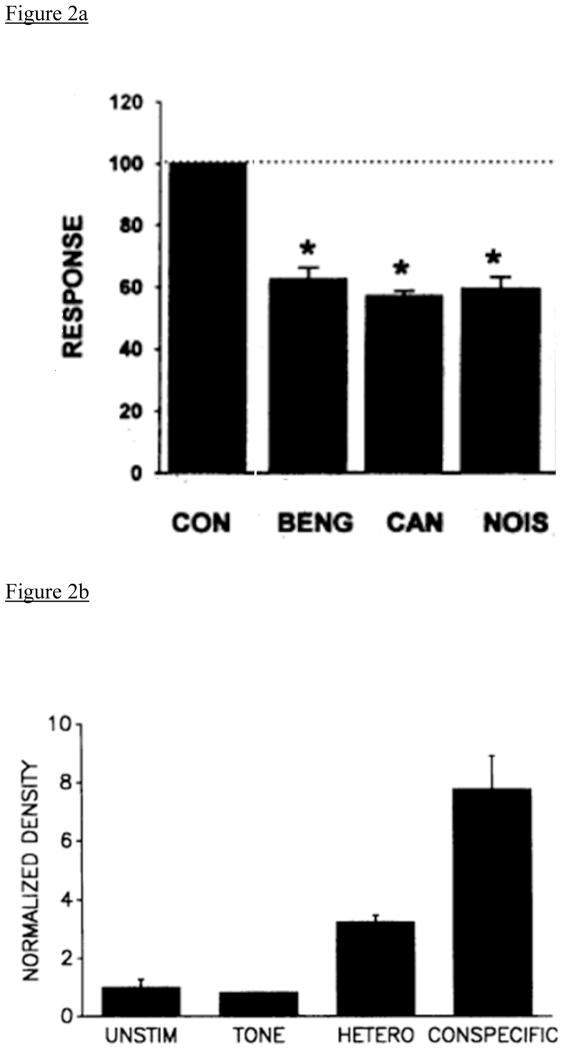

The ability to discriminate and recognize conspecific songs has been documented in an avian auditory forebrain area called the caudomedial nidopallium (NCM). NCM is an auditory processing area that responds differentially to the individual vocalizations (calls and songs) of other birds (Chew et al., 1996a). As shown in Figure 1, NCM receives projections from the Field L complex, the avian primary auditory area, and performs higher-order processing of auditory stimuli. NCM may be comparable to superficial layers of A1 in mammals (Karten, 1991; Wang et al., 2010), or to a secondary auditory area. Both electrophysiological and gene-expression studies have characterized NCM response patterns to playback of different sound types (Figure 2). First, electrophysiological recordings of NCM neurons have shown that NCM responds more robustly (i.e., higher response amplitude) to conspecific than to heterospecific vocalizations or tones (Figure 2a). A similar pattern is observed in studies that measure Zenk, (the protein product of the immediate early gene ZENK, also known as zif-268, Egr-1, NGFI-A and krox-24) that is expressed in NCM in response to species-specific vocalizations (Figure 2b; Chew et al., 1995, 1996a, 1996b; Mello et al., 1992, 1995; review by Clayton, 2000).

Figure 1.

Ascending auditory relays within the Avian Brain. Sound information from the peripheral cochlea is transmitted to the cochlear nucleus (CN) within the brainstem and on to MLd, the homolog of mammalian inferior colliculus. Projections from MLd then enter the thalamic Nucleus Ovoidalis (Ov; homolog of mammalian Medial geniculate nucleus). In mammals, these thalamic neurons project to the layered auditory cortex. In the avian system, they project first to the areas of Field L, which sends projections to both NCM and CMM (yellow). Figure from Bolhuis et al, 2010. Reprinted with permission from MacMillan Publishers Ltd: Nature Reviews Neuroscience (11), copyright 2010.

Figure 2.

Figures 2a and 2b. (a) Multiunit NCM response strength differs when an animal hears playback of different sound types. Conspecific song (zebra finch, in this case) playback elicits a significantly higher response than playback of either heterospecific song types or noise. (BENG: benagalese finch, CAN: canary) Figure from Chew et al, 1996a. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 93(5), 1950–55. Copyright 1996, National Academy of Sciences, USA. (b) Expression of the IEG ZENK shows a response pattern similar to electrophysiological measures. Baseline levels of Zenk are low in unstimulated zebra finches but increases following auditory stimulation. Expression is greatest following playback of conspecific song, intermediate after heterospecific song, and near baseline after tone stimuli. Figure adapted from Mello et al., 1992. Song presentation induces gene expression in the songbird forebrain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 89 (15), 6818–22. Copyright 1992, National Academy of Sciences, USA.

Neural responses to auditory stimuli recorded in NCM have an intriguing property. When an individual stimulus is presented repeatedly, the response amplitude (observed as single-unit responses or multi-unit activity in a population of neurons) decreases asymptotically with each successive trial to reach a final level for any given stimulus (Chew et al., 1995; Stripling et al., 1997). However, when a different, novel stimulus (e.g., the song of another individual bird) is played, the response is reinstated (Chew et al., 1995). These adaptation profiles are independent for each individual stimulus, a phenomenon known as stimulus-specific adaptation. Gene expression studies reveal a similar adaptation phenomenon in response to conspecific song playback: NCM expresses more Zenk in response to playback of a novel stimulus than after playback of a familiar one heard 24h earlier (Mello et al., 1995). Physiological adaptation is longer-lasting for conspecific song stimuli (>24h) than for heterospecific stimuli (<6h). Thus, NCM maintains an ”independent neuronal record of each stimulus” that the bird has heard (Chew et al., 1995), and seems to be specialized for recognizing and remembering familiar conspecific signals.

NCM is a good candidate region in which to focus investigations of the putative direct influence of estrogens on auditory processing and memory. Previous studies using immunohistochemical techniques have found high concentrations of estrogen receptors (Gahr, 2001; Saldanha et al., 2000, 2011) and the enzyme aromatase, which converts the androgen testosterone to estradiol, (Schlinger, 1997, 1998; Remage-Healey et al., 2010b; Saldanha et al., 2000) within NCM of both males and females, laying an inviting foundation for studying estrogenic effects on brain responses to auditory stimuli in this region.

Importantly, the high aromatase levels and estrogen receptors expressed in the telencephalon of songbirds (outside of areas typically involved in the control of reproduction) are not found in other bird species that do not learn their vocalizations, such as the quail (Silverin et al., 2000; Gahr et al., 1993). This difference raises the question of what special role estrogens might play in song learning, discrimination and memory, since NCM is involved in these processes and expresses a high level of both estrogen receptors and the aromatase enzyme that produces estradiol from its precursor. Phan et al. (2006) used electrophysiological measures to show that the memory for the tutor-song in adult male NCM is strongly correlated with the quality of song imitation in each bird. London and Clayton (2008) showed that bilateral blockade of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway (which is upstream of and necessary for ZENK induction; Cheng and Clayton, 2004) in NCM during tutoring impairs learning and results in poor copies of the tutor’s song in adult males (reviewed in Hahnloser and Kotowicz, 2010). In adulthood, NCM responds robustly to socially relevant stimuli. For example, NCM expresses more Zenk in males exposed to playbacks of their tutor’s song and these males show a behavioral preference for this song over that of a novel conspecific (Terpstra et al., 2004). Lesions of NCM in adult males (Gobes and Bolhuis, 2007) suppress this behavioral preference for the tutor-song. In female starlings, the behavioral preference for long-bout song over short-bout song parallels the ZENK induction bias towards long-bout songs in NCM (Gentner et al., 2001). NCM is likely to participate in a host of other discriminations observed among conspecifics (in the wild and the laboratory), such as recognizing and responding to a mate’s vocalizations (Miller, 1979; Caryl, 1976) or responding to the singing of a territorial intruder (Jarvis et al., 1997; Vehrencamp, 2001). Few data are available regarding NCM responses during these social interactions, but recent work is beginning to elucidate how the behavioral relevance of a stimulus and prior exposure to that stimulus, as well as the social context in which it is heard, all influence NCM ZENK induction (Vignal et al, 2005; 2008). The work reviewed here strongly encourages the investigation of estrogenic effects on NCM during these social interactions.

Manipulating Estradiol Induces Changes in NCM Processing

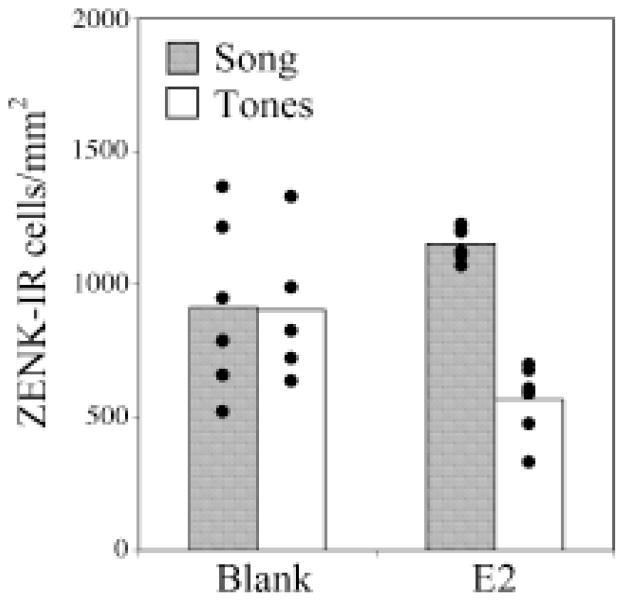

The functional effect of estrogens on NCM processing and behavior can be explored by manipulating estradiol or its availability and assessing changes in the known response patterns in NCM. Maney et al. (2006) increased circulating estradiol in females via subcutaneous implants and examined the density of Zenk-positive cells in NCM after playback of different sounds. In this study, female white-throated sparrows were caught and maintained on short-day light cycle, which places this seasonally breeding species into a non-breeding state. Birds then received estradiol-filled or blank implants and were tested for behavioral and cellular (ZENK induction) responses to male song or tone stimuli. Only the estradiol-treated females performed CSDs in response to male song. In these same birds, Zenk expression was measured in NCM. In females that received blank implants, the levels of Zenk expression did not differ between birds that heard tones versus those that heard song. However, the estradiol-treated females showed differential Zenk expression in NCM that depended on the stimulus played to them; estradiol-treated birds hearing tones showed less gene expression than those hearing song (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

ZENK-ir cells in NCM of blank-implanted and Estrogen implanted female white-throated sparrows listening to song (grey bars) or synthetic tones (white bars). Birds hearing song had more ZENK-ir cells than those hearing tones, but this effect was significant only in E2-treated birds. Among the birds hearing tones, E2-birds had significantly fewer ZENK-ir cells in NCM than blank-implanted birds. Used with permission from Maney, DL; Cho, E & Goode, CT (2006). Estrogen-dependent selectivity of genomic responses to birdsong. European Journal of Neuroscience, 23(6), 1523-9. Copyright 2006, Wiley.

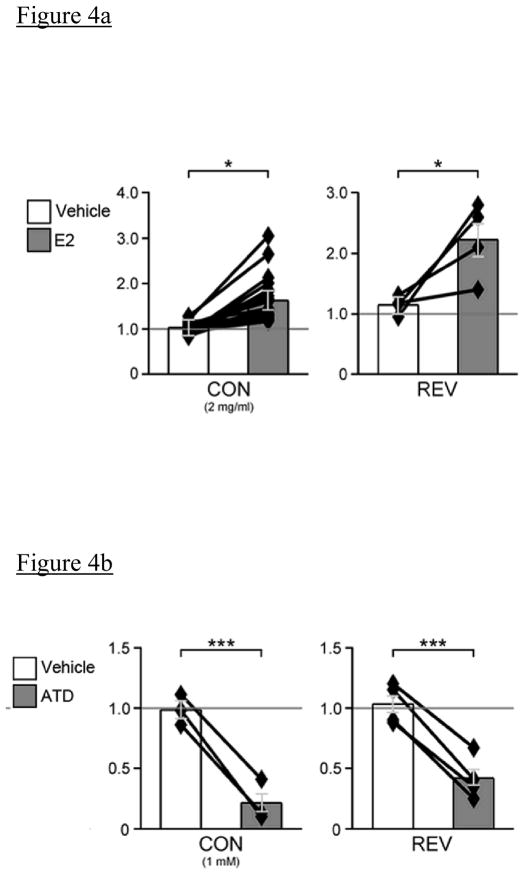

Rather than using systemic manipulations, some investigators have injected or retrodialyzed estradiol or its antagonists locally into NCM to determine the effects on auditory responses. Tremere et al. (2009) directly injected estradiol into the NCM of male and female songbirds and recorded electrophysiological activity during sound playbacks. They found an increase in the firing rate of individual neurons in NCM during playback of both conspecific and reversed conspecific song when estradiol was injected (Figure 4a). When estradiol synthesis was inhibited with the aromatase inhibitor 1, 4, 6-androstatrien-3, 17-dione (ATD), NCM responses decreased to both stimulus types (Figure 4b). A similar decrease in response amplitude was observed when estrogen receptors were blocked by injecting the receptor antagonist Tamoxifen. The authors also reported changes in the amplitude of NCM multiunit activity (MUA) in response to stimulus playbacks (see Figure 4). In a different set of animals given the same treatments, gene expression was measured following exposure to various types of auditory stimuli. Not only did estradiol injection into NCM increase Zenk expression in birds exposed to song playback, but it also increased Zenk expression in birds exposed to silence. When estradiol synthesis was prevented by injecting ATD, the normally observed induction of ZENK to hearing song was prevented, suggesting that locally synthesized estradiol within NCM is necessary for the normal gene expression typically observed in untreated birds after hearing song (as observed in Mello et al., 1992).

Figure 4.

Figure 4a and 4b. Manipulation of estradiol levels within NCM alters neural responses to auditory stimuli playback following injection of estradiol (a) or the aromatase inhibitor ATD (b). X-axes represent the ratio of multiunit response amplitudes of NCM to playback of sound stimuli (pre/post). Pictured are two examples from Tremere et al, 2009, representing changes in response amplitude that occur in response to conspecific song and reversed song stimuli (CON: conspecific song, REV: a conspecific song played in reverse). Figure used with permission from Journal of Neuroscience, 29 (18), Copyright 2009, Society for Neuroscience.

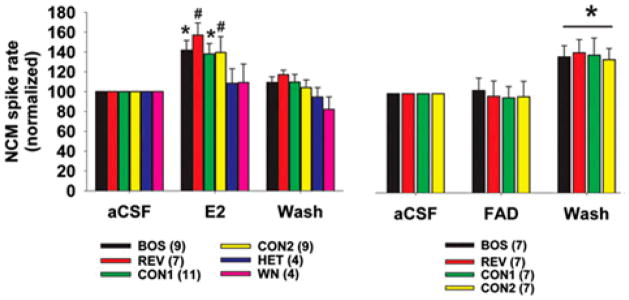

In a similar study performed in anesthetized birds, Remage-Healey et al. (2010a) used retrodialysis to administer estradiol directly into male NCM and also reported the estradiol-induced increase in firing rate to conspecific song playback observed by Tremere et al (2009). Figure 5 illustrates the changes in firing rate that occur during infusion of estradiol (left panel) or the aromatase inhibitor Fadrozole (right panel) into NCM during playback of several types of auditory stimuli that represent distinct categories of sounds known to induce differential responses in NCM. As previously noted, NCM typically exhibits a response bias towards conspecific over heteropecific songs or noise (Chew et al., 1996a; Mello at al., 1992). Areas other than NCM also express selectivity for certain song types. For example, the higher vocal center (HVC), which is important in vocal production, responds more strongly to the bird’s own song (BOS) than to the BOS played in reverse (REV) or to the songs of conspecifics (CON); Theunissen et al., 2004). In contrast, it should be noted that, in NCM, playback of the BOS and reversed BOS elicit similar responses (see Figure 5). During the period of estradiol infusion (Figure 5, left panel), firing rate increased only to playback of stimuli within the conspecific stimulus class, including the BOS, REV, and CON. A comparable increase did not occur to the heterospecific (HET) or white noise (WN) stimuli presented. When Fadrozole was administered via the same method in a different set of birds (Figure 5, right panel), firing rate remained unaffected during playback of the conspecific song stimuli, despite the fact that conspecific stimuli were previously shown to elicit estradiol production in NCM. However, during the drug “washout” period, increased neuronal responses to conspecific song were seen, suggesting that local estradiol is necessary for increased firing rate to occur to conspecific song.

Figure 5.

NCM activity to conspecific song playback increased during microinfusion of estrogen (left panel), relative to microinfusion of aCSF in the same animals. Though a decrease in response was not observed when estrogen synthesis was blocked by administering the aromatase inhibitor Fadrozole (right panel), responses “rebounded” during the drug washout period. Figure from Remage-Healey et al., 2010. Brain estrogens rapidly strengthen auditory encoding and guide song preference in a songbird. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(8), 3852-7. Copyright 2010, National Academy of Sciences, USA.

In the same set of studies (Remage-Healey et al., 2010a), the investigators showed that the manipulation of estradiol within NCM by these methods also influenced male behavioral preferences for song types within a two-choice playback test, which is frequently used to measure song preferences or recognition in birds. During the test, a bird is placed into a cage containing a speaker on either end, each one playing a different stimulus, and an observer records the amount of time the bird spends near each speaker. Under normal conditions, a bird will spend more time near the speaker emitting the BOS or the song of its tutor (see Holveck and Riebel, 2007; Bolhuis and Gahr, 2006), indicating that the bird remembers this song and can discriminate it from other stimuli. During an initial aCSF (vehicle) infusion into NCM, males spent more time near the speaker playing the BOS. This behavioral preference was abolished when Fadrozole was infused (preventing estradiol synthesis), suggesting that these males no longer discriminated their own song from other, unfamiliar songs. This effect was specific to the blockade, because the behavioral preference was reinstated during the final vehicle infusion. Interestingly, the experimenters only observed the suppression of BOS preference when Fadrozole was retrodialyzed into the left hemisphere, but not the right, potentially supporting the idea that the processing of learned communication signals is lateralized within the brain (for review on lateralization, see Tommasi, 2009). Phan and Vicario (2010) have recently demonstrated a form of lateralization in zebra finches, showing that playbacks of songs and calls elicits different responses from left and right NCM (measured as absolute response magnitude and adaptation rate). They further showed that the lateralization process depends on developmental experience with communication signals, since birds raised in acoustic and social isolation did not exhibit these lateral NCM differences.

The studies conducted by Tremere and Pinaud (2011) extend the Remage-Healey et al. (2010a) finding and support the hypothesis that local estradiol action in NCM is necessary for accurate discrimination of sounds, specifically songs. In this study, they manipulated local estradiol levels within NCM and then tested male birds for their preference for a familiar song (the song of their tutor) versus a novel conspecific one, using the two-choice paradigm. Birds that first received bilateral NCM injections of saline exhibited this normally observed preference for the tutor-song. However, when the same birds were injected bilaterally with the estrogen receptor antagonists Tamoxifen (TMX) or 7α,17β-[9-[(4,4,5,5,5-pentafluoropentyl)sulfinyl]nonyl]estra-1,3,5(10)-triene-3,17-diol](ICI) or the estrogen synthesis inhibitors Fadrozole or ATD, the preference for the tutor-song was no longer observed. Interestingly, this effect appears to be specific to discrimination of individual songs, since performance of animals subjected to the same treatments and tested in a call discrimination task was unaffected by interference with estradiol production in NCM. The typically expressed preference for female rather than male long calls (as observed in Vicario et al, 2001) was observed both before and after drug infusion. Together, these studies suggest that local estradiol synthesis may be necessary for normal discrimination of some socially relevant auditory stimuli, and that it is sufficient to induce changes in behavioral response to these stimuli. However, the relationship between estradiol and behavior appears to be more complex and even bidirectional: studies have shown that not only can estradiol induce changes in auditory responses but that exposure to sound alone can induce changes in estradiol production.

As mentioned earlier in this review, social interactions can induce rapid increases in circulating hormones, and it appears that they can induce similar increases within the brain (also see Maney et al, 2007). Remage-Healey et al (2008) reported increases in locally synthesized estradiol in male NCM within 30min, measured by in vivo microdialysis, following exposure to a nearby female, and these increases were blocked when the estrogen-synthesis inhibitor Fadrozole was retrodialyzed. Because the presentation of a female usually resulted in the male singing to her (not all of the males in this study sang, but estrogen was increased even in the one that did not), the experimenters also tested whether exposure to different types of auditory stimuli could also increase local estradiol in NCM. Estradiol levels increased in the group of males exposed to male song (individual male or a mixed aviary recording) but not in males exposed to tones or female “chirp” calls (short calls produced by males and females). A similar study should be conducted in female NCM to determine whether a similar local increase in estradiol occurs in response to male song. Playback of male vocalizations can increase circulating estradiol in female frogs (Lynch and Wilczynki, 2006; Wilczynki and Lynch, 2011; reviewed in Arch and Narins, 2009) and ring doves (Lehrman and Friedman, 1969; Cheng, 1986). Tchernichovski et al. (1998) showed that female zebra finches exposed to playback of male song have increased circulating estradiol levels after five days, and subsequently begin to lay eggs two or more days after this increase. Presumably, the song playbacks were sexually stimulating to the females and triggered estradiol synthesis within the gonads, but it would be interesting to determine the chain of events that preceded this increase in circulating steroid level and subsequent egg-laying. For example, if local increases in NCM estradiol were observed during or after song playback, would this be the result of local synthesis (as has been observed in males), the result of circulating estradiol, or both? It is possible that estradiol production in NCM occurs first in response to hearing song, alters subsequent perception of male song, and stimulates gonadal estrogen synthesis, increasing circulating estradiol as observed in previous playback experiments.

Estrogen Acts on Many Targets and on Multiple Time Scales

Importantly, estrogen manipulations within NCM induced effects rapidly in many of the studies described above. The field is currently developing a better understanding of the modalities through which estrogen interacts with the brain to influence basic processes of learning and memory, and this has led to a distinction between “classical” versus “non-classical” steroid effects, each with its own time course (see McEwen, 2001; Woolley, 2007). A requirement of both routes is that estrogen binds to an estrogen receptor, but the distinction depends on whether receptor-bound estrogen interacts with the cell nucleus. In the classical perspective, estradiol (which is lipophilic) traverses the cell membrane, binds to one of its receptors (alpha or beta) located within either the cell’s cytoplasm or nucleus, interacts with Estrogen Response Elements (ERE) in DNA and initiates gene expression. The time frame for these events requires at least 45 minutes (for new protein synthesis to occur) and longer for changes that are downstream, but estradiol has been shown to induce increases in cell firing within seconds of application (e.g., in the hippocampus: Wong and Moss, 1992). In the non-classical (rapid) timeframe (Kelly and Levin, 2001), estrogen could bind with the more recently discovered extranuclear receptors (ERα, ERβ, ERx, GPR30) to activate cellular signaling events (e.g. protein kinases) and ultimately change cellular responses to stimuli (Woolley, 2007; Roepke et al., 2011). Estrogen has been demonstrated to work via the non-genomic pathway to influence synaptic transmission (e.g, altering calcium influx) and cellular responsivity (e.g, indirectly inhibiting GABAergic transmission by altering its receptor conformation; Kelly and Wagner, 1999). Other work suggests that even faster estrogenic modulation may be mediated via steroid receptor sites on neurotransmitter receptors (e.g. GABA, Qui et al., 2003; nicotinic, Paradiso et al., 2001) These interactions occur on a time scale of seconds to minutes and can therefore affect cellular and, presumably, behavioral responses quickly.

The rapid influence on behavior (within 30 minutes) thus far observed via manipulation of estradiol within NCM implies that it must be exerting its actions through the non-genomic mechanism (perhaps by influencing the activity of neurotransmitters) rather than through the much slower classical mechanism involving a cytoplasmic receptor that ultimately induces gene expression. For example, Remage-Healey et al. (2008, 2010a) observed increases in both estrogen synthesis (2008) and NCM firing rate in male songbirds within 30 minutes following exposure to male song, although the increase could have occurred on an even shorter time frame, since the experimenters were limited to half hour intervals of dialysate collection. Likewise, Tremere et al. (2009) documented IEG-expression changes within 30 minutes in animals administered local estrogen and firing increases within a few minutes under the same estrogenic conditions during male song playback.

Another remarkable phenomenon that could contribute to the rapid action of estradiol is the speed with which it can be synthesized in particular areas of the brain. Studies conducted in quail (reviewed in Balthazart, 2009) have shown that several male sexual behaviors are modulated by the synthesis of estradiol and its effects within the hypothalamic-preoptic area (HPOA). Balthazart et al. (2004) have demonstrated that local estradiol increases can result from increases in the concentration of the aromatase enzyme (requires transcription and takes hours to days) or from conformational changes of existing enzyme molecules (e.g. due to changes in phosphorylation, which do not require transcription and take seconds to minutes). In the non-genomic mechanism, aromatase can shift between “inactive” and “active” states when phosphorylated or dephosphorylated, respectively, triggered by changes in the local cellular environment (e.g., calcium concentrations, neurotransmitter release). This kind of mechanism, which can alter the concentration of estradiol within minutes, may underlie the rapid estradiol production observed in NCM during exposure to socially relevant stimuli. Two very recent papers suggest this could reflect the modulation of aromatase activity in presynaptic terminals. Remage-Healey et al. (2011) show that estradiol concentrations can be modulated by pre-synaptic calcium influx into NCM neurons. Saldanha et al. (2011) develop the concept of “synaptocrine signaling” to describe the non-classical mechanisms by which activity-dependent modulation of “gonadal” steroids at the synapse can influence neural activity and behavior.

Toward a Socio-Neuro-Endocrinology Perspective

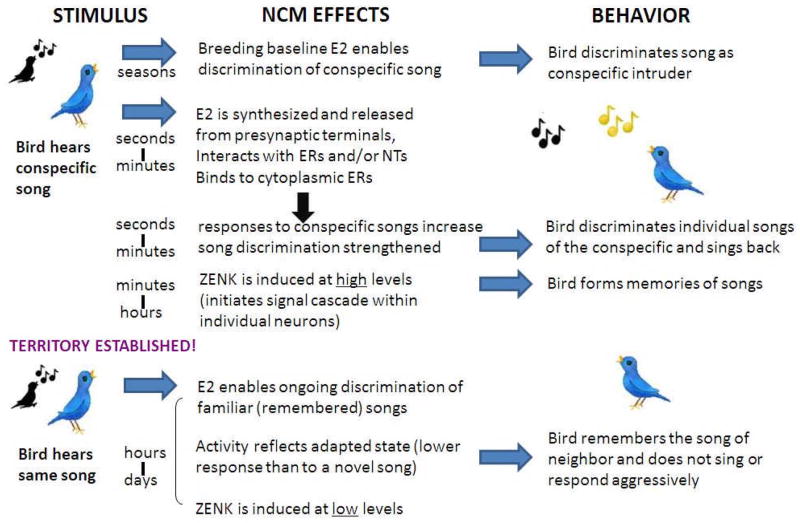

Based on the results of the studies conducted to date, it appears that estrogen action within the auditory system is complex; estrogens appear to rapidly modulate auditory processing and be modulated by internal (reproductive state) and external (social, auditory) factors. This accumulating evidence suggests that understanding estrogenic actions in the brain will require a socio-neuro-endocrinology perspective. Many situations that a bird experiences in the wild require rapid behavioral responses that reflect both stimulus conditions and the animal’s state. In addition, many social behaviors, such as the complex set of behaviors during courtship or territorial disputes, unfold in a social dialog over a period of time. Studies reviewed above imply that songbirds require a minimum level of estradiol in NCM to recognize, then respond appropriately to particular auditory stimuli in their environment. Thus, estradiol appears to function as a necessary modulator of perception and thus contributes to the resultant behaviors.. In addition, the ensemble of data reviewed above support the hypothesis that certain patterns of auditory (or other social) stimulation induce a temporarily higher level of estradiol (due to aromatase modulation) which then enables sharper discrimination and/or memory when similar stimuli are heard subsequently (minutes later) as part of an ongoing interaction or repeated contact (as with neighbors). This kind of repeated interaction could occur during courtship (Zann, 1996), or during the establishment/maintenance of territorial boundaries in some songbird species, such as the song sparrow or banded wrens (Vehrencamp, 2001; Molles and Vehrencamp, 2001). Males of these species engage in song-matching competitions in order to defend their territory from conspecific males (Vehrencamp, 2001). Estradiol action within NCM may play a necessary role in the process and outcome of such competitions (as schematized in Figure 6), since a male defending his territory must discriminate the songs of the intruder from one another and from the song of his neighbors (Molles and Vehrencamp, 2001) and respond appropriately.

Figure 6.

A hypothetical flow chart depicting how estradiol might act in the brain to modulate behavior during the process of song matching in a territorial songbird. Top: A resident male hears an unfamiliar conspecific male singing nearby. A baseline level of estradiol (reflecting seasonal factors) allows the bird to make coarse discriminations among categories of sounds, thus identifying the song as that of an intruder. As the intruder continues to sing, estradiol concentrations within NCM increase as a result of rapid pre-synaptic “synaptocrine” signaling mechanisms that rapidly convert androgen precursors. Estradiol interacts with NCM neurons though non-genomic mechanisms and both increases responses to song and sharpens discrimination. As a result, the resident male and counter-sings an appropriate matching song and successfully defends his territory. During this interaction, conspecific song induces immediate early genes (e.g. ZENK) in NCM neurons, initiating a signaling cascade that enables the male to form memories of the intruder’s songs. Bottom: Following this territorial dispute, the resident male hears the song of his new neighbor once again. Estradiol may contribute to recognition of his neighbor’s song. Electrophysiological responses are lower and adapt more slowly to repeated hearings of the song (reflecting a memory for the song), compared with the previous encounter. As a result, the bird recognizes the song and does not engage in aggressive behavior towards his neighbor. In addition, ZENK is induced at a low level, typical of familiar songs. (E2: estradiol, ER: estrogen receptor, NT: neurotransmitter)

It appears that a baseline level of estradiol could enable gross discrimination among categories of sounds during social encounters. Classically, NCM responds more robustly to conspecific than to heterospecific novel songs, and given the studies reviewed here, this selectivity may be suppressed under estradiol blockade. Recent work in our laboratory has shown that systemic blockade of estradiol synthesis in female zebra finches reduces the neural response bias towards conspecific song (Yoder and Vicario, 2010). Phillmore et al. (2011) have also shown that NCM in male black-capped chickadees expresses more Zenk in response to conspecific than heterospecific vocalizations during the breeding season, but not during the non-breeding season, suggesting a role for hormonal modulation (a seasonal change in the estradiol baseline) of discrimination as measured by Zenk. Behaviorally, this gross discrimination of conspecific from heterospecific vocalizations may be important for both sexes: for females, selecting a suitor from her own species, and for males, defending a territory. During exposure to song playback, estradiol increases from its baseline level, as shown in microdialysis studies conducted by Remage-Healey et al. (2008, 2011). This increase could affect subsequent auditory processing, because estradiol retrodialyzed into NCM selectively increases the firing rate to conspecific songs but not heterospecific songs or white noise (Remage-Healey et al., 2010a).

An increase in local estradiol synthesis from baseline can be induced by exposure to a particular “triggering,” behaviorally relevant stimulus, e.g., song of conspecific male or visual encounter with a female. For example, Remage-Healey et al. (2008) showed that male song but not female vocalizations elicited an increase in local estradiol production within 30 minutes. This increase could serve to sharpen discrimination because it affects auditory processing to increase response size (Remage-Healey et al., 2010a). In addition, Tremere and Pinaud (2011) showed that blocking estradiol disrupts the auditory coding of NCM neurons, so that neural responses no longer discriminate as well between individual conspecific songs. Thus elevated estradiol, by improving auditory discrimination, could help to improve behavioral discrimination among stimuli. Remage-Healey et al. (2010a) and Tremere and Pinaud (2011) have shown that blocking estrogenic action in NCM impairs behavioral discrimination of BOS or tutor-song from unfamiliar songs. So far, existing data show that estradiol within NCM is required for neural and behavioral discrimination of novel versus these particular forms of familiar song, but may also be necessary for behavioral discriminations among songs heard for the first time in an ongoing behavioral context.

An additional possibility is that estradiol production induced by particular stimuli might contribute to underlying memory processes that allow a bird to form new memories for recently-heard songs. Induction of the IEG ZENK, which is implicated in memory processes and exhibits stimulus specific adaptation (Clayton, 2000), does not occur in response to hearing conspecific vocalizations when estrogen receptors are blocked or its synthesis is inhibited (Tremere et al., (2009). If ZENK induction is a necessary component of memory formation and requires estradiol, then blocking estradiol action might prevent memory formation for specific songs. Consistent with this, an electrophysiological study showed that neuronal memories for recently-heard songs are disrupted in birds treated with Fadrozole (Yoder and Vicario, 2010). Given that blocking estradiol within NCM suppressed the behavioral response for BOS (Remage-Healey et al., 2010a), estradiol also might contribute to recalling a previously formed memory, since the task requires the animal to discriminate a familiar stimulus (BOS) from a novel one.

The socio-neuro-endocrine hypothesis allows a dynamic interaction among an animal’s environment, auditory processing, and local estradiol concentrations. The baseline level of estradiol in NCM could fluctuate with the animals circulating gonadal hormone levels. In seasonal species, circulating gonadal hormones are modulated by photoperiod (Wingfield and Hahn, 1994; Soma and Wingfield, 2001; Ball et al., 2004). Local concentrations of estradiol in NCM may be increased during this period, enabling discrimination of conspecific songs and facilitating territorial establishment/defense and mate selection. In males, more testosterone would be available for conversion to estradiol. In females, an increase in circulating estrogens produced by the ovaries could influence NCM activity directly, since Remage-Healey et al. (2008) showed that estradiol injected peripherally also induces increases in NCM. Maney et al. (2006) showed that differential Zenk expression to songs versus tones could be induced by photo period change (short-long days) or by estrogen implants in female birds. Fluctuations in circulating concentrations of estradiol could “prime” the auditory system to process and discriminate sexually salient stimuli during a time when birds must establish territories, or select mates, and when reproduction is more likely to be successful. In the non-breeding season, plasma levels of steroids in songbirds are considerably lower (Soma et al, 2003; Wingfield and Hahn, 1994; Soma and Wingfield, 2001) and this can impact auditory discrimination in NCM. In non-breeding male chickadees, NCM Zenk expression in response to hearing CON vs. HET stimuli does not differ (Phillmore at al, 2011). In female white-throated sparrows maintained on short days, Zenk expression was not different for songs vs. tones (Maney et al, 2006), suggesting that even coarse discrimination was poor when baseline estradiol levels were presumably low. The dynamic induction of estradiol within the auditory forebrain by hearing song stimuli (reviewed above) has not yet been compared between breeding and non-breeding birds.

Though published studies to date have measured the fluctuating estradiol levels locally within male NCM, it may be that the rapid increase in estradiol observed in male zebra finches upon song playback also occurs in females, since NCM of both sexes contains aromatase and estrogen receptors, and because manipulation of estrogen via receptor antagonism or inhibiting its synthesis yielded similar physiological (Tremere et al., 2009) effects in both sexes. Females do express less aromatase in NCM than males (Saldanha et al., 2000), but females are able to produce estrogens gonadally (unlike males), which could sustain a baseline level within NCM. This has to be tested directly in females, but Remage-Healey et al. (2008) showed that local estradiol levels increased in male NCM when estradiol was injected systemically, suggesting that estradiol synthesized elsewhere is also able to influence NCM activity. Additionally, indirect evidence suggests that a baseline level of estrogen is present in male and female NCM, since inhibiting its action or conversion leads to alteration in physiological discrimination measures in both sexes (Tremere et al., 2009; Tremere and Pinaud, 2011). Together, these results suggest that estradiol (whether produced locally or gonadally) could influence NCM activity in the same way regardless of sex.

Experimentally, the fact that local estrogenic action could be influenced by circulating estradiol or by exposure to particular contexts complicates the process of testing its effects, since one needs to control for all the relevant (including possibly unknown) variables. On the other hand, the multiple routes of activation afford investigators the opportunity to influence estradiol production via manipulation of context (exposure to male song, e.g.) or pharmacology (direct injection into brain areas), investigate through which mechanisms estrogens are enabling the observed changes in behavioral and physiological (zenk, electrophysiology), and importantly, determine on what time scale these chains of events occur. Precise experiments designed to address these questions would provide valuable insight into how perception and behavior are modulated by estrogens during social interactions. Some of these questions could even be addressed in human experiments using brain imaging techniques to examine aromatase activity and overlapping activation of brain areas (e.g., temporal structures) during different social activities of different intensity and salience. A recent study that employed PET overlaid with MRI images was able to identify concentrations of aromatase in several brain regions (including non-limbic regions) in human participants (Biegon et al., 2010), laying the foundation for future studies regarding estrogen synthesis and its influence on brain physiology in humans.

Conclusion

The studies reviewed here not only identify estrogens as essential components of auditory processing and discrimination but also provide an exciting example of how estrogens can be activated within a single area of the auditory system to alter an animal’s behavioral response to a particular stimulus or stimulus class during ongoing social interactions. Continued efforts that employ a socio-neuro-endocrinology framework will contribute to the intriguing possibility that brain-estrogen interactions could influence behaviors occurring in a “realistic”, ethological context and time frame, not only in songbirds but in other species, bringing us one step closer to understanding the interactive relationship between brain and behavior. Estrogens might modulate perception similarly during exchange of social information in humans and other mammals, given the widespread presence of receptors and aromatase within the brains of many species. Some disorders characterized by social deficits may be due to problems in interpreting communication signals, and these processing deficits could reflect abnormalities in estradiol synthesis or receptor systems in relevant sensory areas. Potentially, investigations that explore the neuro-socio-endocrine hypothesis could lead to treatments that facilitate communication in individuals with social deficits.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tracey Shors and John McGann for helpful discussions during the preparation of this manuscript. We would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers, who provided valuable suggestions and greatly improved its quality.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at www.apa.org/pubs/journals/bne

References

- Adkins-Regan E. Hormone specificity, androgen metabolism, and social behavior. American Zoologist. 1981;21:257–71. [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa H, Blanchard DC, Arakawa K, Dunlap C, Blanchard RJ. Scent marking behavior as an odorant communication in mice. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32(7):1236–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arch VS, Narins PM. Sexual hearing: The influence of sex hormones on acoustic communication in frogs. Hearing Research. 2009;252:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azcotia I, Yague JG, Garcia-Segura LM. Estradiol synthesis within the human brain. Neuroscience. 2011;191:139–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball GF, Riters LV, Balthazart J. Neuroendocrinology of song behavior and avian brain plasticity: Multiple sites of action of sex steroid hormones. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2002;23:137–78. doi: 10.1006/frne.2002.0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball GF, Auger CJ, Bernard DJ, Charlier TD, Sartor JJ, Riters LV, Balthazart J. Seasonal plasticity in the song control system: Multiple brain sites of steroid hormone action and the importance of variation in song behavior. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1016:586–610. doi: 10.1196/annals.1298.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazart J, Absil P, Foidart A, Houbart M, Harada N, et al. Distribution of aromatase-immunoreactive cells in the forebrain of zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata): Implications for the neural action of steroids and nuclear definition in the avian hypothalamus. Journal of Neurobiology. 1996;31:129–48. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4695(199610)31:2<129::AID-NEU1>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazart J, Baillien M, Cornil CA, Ball GF. Preoptic aromatase modulates male sexual behavior: slow and fast mechanisms of action. Physiology and Behavior. 2004;83(2):247–70. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazart J, Taziaux M, Holloway K, Ball GF, Cornil CA. Behavioral effects of brain-derived estrogens in birds. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2009;1163:31–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2008.03637.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass AH. Steroid-dependent plasticity of vocal motor systems: Novel insights from a teleost fish. Brain Research Reviews. 2008;57(2):299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biegon A, Kim SW, Alexoff DL, Jayne M, Carter P, et al. Unique distribution of aromatase in the human brain: in vivo studies with PET and [N-methyl-11C]vorozole. Synapse. 2010;64(11):801–7. doi: 10.1002/syn.20791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolhuis JJ, Gahr M. Neural mechanisms of birdsong memory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2006;7(5):347–57. doi: 10.1038/nrn1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolhuis JJ, Okanoya K, Scharff C. Twitter evolution: Converging mechanisms in birdsong and human speech. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2010;11:747–59. doi: 10.1038/nrn2931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenowitz EA. Altered perception of species-specific song by birds after lesions of a forebrain nucleus. Science. 1991;251:303–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1987645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callard GV, Petro Z, Ryan KJ. Conversion of androgen to estrogen and other steroids in the vertebrate brain. Integrative and Comparative Biology. 1978;18(3):511–23. [Google Scholar]

- Caryl PG. Sexual behavior in the zebra finch Taeniopygia guttata: Response to familiar and novel partners. Animal Behaviour. 1976;24(1):93–107. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty M, Burmeister SS. Estradiol induces sexual behavior in female túngara frogs. Hormones and Behavior. 2009;55(1):106–12. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charitidi K, Canlon B. Estrogen receptors throughout the auditory system. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;165(3):923–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlier TD. Importance of steroid receptor coactivators in the modulation of steroid action on brain and behavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:S20–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew SJ, Mello C, Nottebohm F, Jarvis E, Vicario DS. Decrements in auditory responses to a repeated conspecific song are long-lasting and require two periods of protein synthesis in the songbird forebrain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1995;92:3406–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew SJ, Vicario DS, Nottebohm F. A large-capacity memory system that recognizes the calls and songs of individual birds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1996a;93(5):1950–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew SJ, Vicario DS, Nottebohm F. Quantal duration of auditory memories. Science. 1996b;274(5294):1909–14. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5294.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng MF. Female cooing promotes ovarian development in ring doves. Physiology & Behavior. 1986;37 (2):371–374. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90248-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HY, Clayton DF. Activation and habituation of erxtracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylation in zebra finch auditory forebrain during song presentation. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(34):7503–13. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1405-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton DF. The genomic action potential. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2000;74:185–216. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2000.3967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forlano PM, Deitcher DL, Bass AH. Distribution of estrogen receptor alpha mRNA in the brain and inner ear of a vocal fish with comparisons to sites or aromatase expression. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2005;483(1):91–113. doi: 10.1002/cne.20397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick KM. Estrogens and age-related memory decline in rodents: What have we learned and where do we go from here? Hormones and Behavior. 2009;55(1):2–23. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahr M. Distribution of sex steroid hormone receptors in the avian brain: functional implications for neural sex differences and sexual behaviors. Microscopy Research and Technique. 2001;55(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahr M, Guttinger H, Kroodsma DE. Estrogen receptors in the avian brain: Survey reveals general distribution and forebrain areas unique to songbirds. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1993;327(1):112–22. doi: 10.1002/cne.903270109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentner TQ, Hulse SH, Duffy D, Ball GF. Response biases in auditory forebrain regions of female songbirds following exposure to sexually relevant variation in male song. Journal of Neurobiology. 2001;46(1):48–58. doi: 10.1002/1097-4695(200101)46:1<48::aid-neu5>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobes SM, Bolhuis JJ. Birdsong memory: A neural dissociation between song recognition and production. Current Biology. 2007;17:789–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E, Woolley CS, Frankfurt M, McEwen BS. Gonadal steroids regulate dendritic spine density in hippocampal pyramidal cells in adulthood. 1990 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-04-01286.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahnloser RHR, Kotowicz A. Auditory representations and memory in birdsong learning. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2010;20(3):332–9. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding CF. Social modulation of circulating hormone levels in the male. American Zoologist. 1981;21:223–31. [Google Scholar]

- Holveck MJ, Riebel K. Preferred songs predict preferred males: Female zebra finches show consistent and repeatable preferences across different testing paradigms. Animal Behaviour. 2007;74:297–309. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis ED, Schwabl H, Ribiero S, Mello CV. Brain gene regulation by territorial singing behavior in freely ranging songbirds. Neuroreport. 1997;8(8):2073–7. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199705260-00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis ED, Scharff C, Grossman MR, Ramos JA, Nottebohm F. For whom the bird sings: context-dependent gene expression. Neuron. 1998;21(4):775–88. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80594-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karten HJ. Homology and Evolutionary Origins of the ‘Neocortex’. Brain, Behavior, and Evolution. 1991;38(4–5):264–72. doi: 10.1159/000114393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MJ, Levin ER. Rapid actions of plasma membrane estrogen receptors. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2001;12(4):152–6. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MJ, Wagner EJ. Estrogen modulation of G-protein-coupled receptors. Trends in Endocrinology Metabolism. 1999;10(9):369–74. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(99)00190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GC, Shughrue PJ, Mercanthaler I, Gustafsson JA. The estrogen receptor beta subtype: a novel mediator of estrogen action in neuroendocrine systems. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 1998;19(4):253–86. doi: 10.1006/frne.1998.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrman DS, Friedman M. Auditory stimulation of ovarian activity in the ring dove (Streptopelia risoria) Animal Behaviour. 1969;17(3):494–7. doi: 10.1016/0003-3472(69)90152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leboucher G, Depraz V, Kreutzer M, Nagle L. Male song stimulation of female reproduction in canaries: Features relevant to sexual displays are not relevant to nest-building or egg-laying. Ethology. 1998;104:613–24. [Google Scholar]

- London SE, Clayton DF. Functional identification of sensory mechanisms required for developmental song learning. Nature Neuroscience. 2008;11:579–86. doi: 10.1038/nn.2103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch K, Wilczynki W. Social regulation of plasma estradiol concentration in a female anuran. Hormones and Behavior. 2006;50(1):101–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maney DL, Cho E, Goode CT. Estrogen-dependent selectivity of genomic responses to birdsong. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2006;23(6):1523–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04673.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maney DL, Goode CT, Lake JI, Lange HS, O’Brien S. Rapid neuroendocrine responses to auditory courtship signals. Endocrinology. 2007;148:5611–13. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen B. Invited review: Estrogens effects on the brain: Multiple sites and molecular mechanisms. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2001;91(6):2785–801. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.6.2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C, Vicario DS, Clayton DF. Song presentation induces gene expression in the songbird forebrain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1992;89(15):6818–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.15.6818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello C, Nottebohm F, Clayton D. Repeated exposure to one song leads to a rapid and persistent decline in an immediate early gene’s response to that song in zebra finch telencephalon. Journal of Neuroscience. 1995;15(10):6919–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06919.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mermelstein PG, Micevych PE. Nervous system physiology regulated by membrane estrogen receptors. Reviews in Neuroscience. 2008;19 (6):413–24. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2008.19.6.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DB. The acoustic basis of mate recognition by female zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) Animal Behavior. 1979;27:376–80. [Google Scholar]

- Molles LE, Vehrencamp SL. Neighbor recognition by resident males in the banded wren, Thryothorus pleurostictus, a tropical songbird with high song type sharing. Animal Behaviour. 2001;61(1):119–27. doi: 10.1006/anbe.2000.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowicki S, Searcy WA. Song function and the evolution of female preferences: why birds sing, why brains matter. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1016:704–23. doi: 10.1196/annals.1298.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packard MG. Posttraining estrogen and memory modulation. Hormones and Behavior. 1998;34(2):126–39. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1998.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradiso K, Zhang J, Steinbach JH. The C terminus of the human nicotinic alpha4beta2 receptor forms a binding site required for potentiation by an estrogenic steroid. Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;21(17):6561–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06561.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrini E, Menuet A, Lethimonier C, Adrio F, Gueguen NM, Tascon C, Anglade I, et al. Relationships between aromatase and estrogen receptors in the brain of a teleost fish. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 2005;142(1–2):60–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff DW, Kow LM, Loose MD, Flanagan-Cato LM. Reverse engineering the lordosis behavior circuit. Hormones and Behavior. 2008;54(3):347–54. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaff DW, Sakuma Y. Deficit in the lordosis reflex of female rats caused by lesions in the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus. Journal of Physiology. 1979;288:203–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan ML, Pytte CL, Vicario DS. Early auditory experience generates long-lasting memories that may subserve vocal learning in songbirds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103(4):1088–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510136103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phan ML, Vicario DS. Hemispheric differences in processing of vocalizations depend on early experience. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107(5):2301–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900091107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillmore LS, Veysey AS, Roach SP. Zenk expression in auditory regions changes across breeding condition in male Black-capped chickadees (Poecile atricapillus) Behavioural Brain Research. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu J, Bosch MA, Tobias SC, Grandy DK, Scanlan TS, et al. Rapid signaling of estrogen in hypothalamic neurons involves a novel G-protein-coupled estrogen Receptor that Activates Protein Kinase C. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(29):9529–40. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-29-09529.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remage-Healey L, Bass AH. Rapid elevations in both steroid hormones and vocal signaling during playback challenge: A field experiment in Gulf toadfish. Hormones and Behavior. 2005;47(3):297–305. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2004.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remage-Healey L, Bass AH. From social behavior to neural circuitry: Steroid hormones rapidly modulate advertisement calling via a vocal pattern generator. Hormones and Behavior. 2006;50(3):432–41. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remage-Healey L, Coleman ME, Oyama RK, Schlinger BA. Brain estrogens rapidly strengthen auditory encoding and guide song preference in a songbird. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010a;107(8):3852–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906572107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remage-Healey L, London SE, Schlinger BA. Birdsong and the neural production of steroids. Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 2010b;39(2):72–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2009.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remage-Healey L, Maidment NT, Schlinger B. Forebrain steroid levels fluctuate rapidly during social interactions. Nature Neuroscience. 2008;11(11):1327–34. doi: 10.1038/nn.2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remage-Healey L, Maidment NT, Dong SM, Schlinger BA. Presynaptic control of rapid estrogen fluctuations in the songbird auditory forebrain. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(27):10034–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0566-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roepke TA, Ronnekleiv OK, Kelly MJ. Physiological consequences of membrane-initiated estrogen signaling in the brain. Frontiers in Bioscience. 2011;16:1560–73. doi: 10.2741/3805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuma Y, Pfaff DW. Excitability of female rat central gray cells with medullary projections: Changes produced by hypothalamic stimulation and estrogen treatment. Journal of Neurophysiology. 1980;44(5):1012–23. doi: 10.1152/jn.1980.44.5.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha CJ, Tuerk MJ, Kim YH, Fernandes AO, Arnold AP, Schlinger BA. Distribution and regulation of telencephalic aromatase expression in the zebra finch revealed with a specific antibody. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2000;423(4):619–30. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20000807)423:4<619::aid-cne7>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha CJ, Remage-Healey L, Schlinger BA. Synaptocrine signaling: Steroid synthesis and action at the synapse. Endocrinology Reviews. 2011 doi: 10.1210/er.2011-0004. (epub) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlinger BA. Sex-steroids and their actions on the bird song system. Journal of Neurobiology. 1997;35:619–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlinger BA. Sexual differentiation of avian brain and behavior: Current views on gonadal hormone-dependent and independent mechanisms. Annual Review of Physiology. 1998;60:407–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shors TJ. Estrogen and learning: Strategy over parsimony. Learning and Memory. 2005;12(2):84–5. doi: 10.1101/lm.93305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverin B, Baillien M, Foidart A, Balthazart J. Distribution of aromatase activity in the the brain and peripheral tissues of passerine and nonpasserine avian species. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 2000;117(1):34–53. doi: 10.1006/gcen.1999.7383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simerly RB, Swanson LW, Chang C, Muramatsu M. Distribution of androgen and estrogen receptor mRNA-containing cells in the rat brain: An in situ hybridization study. The Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1990;294 (1):76–95. doi: 10.1002/cne.902940107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soma KK, Schlinger BA, Wingfield JC, Saldanha CJ. Brain aromatase, 5α,-reductase, and 5β,-reductase change seasonally in wild male song sparrows: Relationship to aggressive and sexual behavior. Journal of Neurobiology. 2003;56(3):209–21. doi: 10.1002/neu.10225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soma KK, Wingfield JC. Dehydroepiandrosterone in songbird plasma: Seasonal regulation and relationship to territorial aggression. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 2001;123(2):144–55. doi: 10.1006/gcen.2001.7657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stripling R, Volman SF, Clayton DF. Response modulation in the zebra finch neostriatum: relationship to nuclear gene regulation. Journal of Neuroscience. 1997;17(10):3883–93. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03883.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor AH, Al-Azzawi F. Immunolocalisation of oestrogen receptor beta in human tissues. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 2000;24(1):145–55. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0240145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchernichovski O, Schwabl H, Nottebohm F. Context determines the sex appeal of male zebra finch song. Animal Behavior. 1998;55:1003–10. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1997.0673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terpstra NJ, Bolhuis JJ, den Boer-Visser AM. An analysis of the neural representation of birdsong memory. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(21):4971–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0570-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theunissen FE, Amin N, Shaevitz SS, Woolley SM, Fremouw T, Hauber ME. Song selectivity in the song system and in the auditory forebrain. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1016:222–45. doi: 10.1196/annals.1298.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tommasi L. Mechanisms and functions of brain and behavioural asymmetries. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 2009;364(1519):855–9. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toran-Allerand CD. Mini-Review: A plethora of estrogen receptors in the brain: Where will it end? Endocrinology. 2003;145(3):1069–74. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremere LA, Jeong JK, Pinaud R. Estradiol shapes auditory processing in the adult brain by regulating inhibitory transmission and plasticity-associated gene expression. Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;29(18):5949–63. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0774-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremere LA, Pinaud R. Brain-generated estradiol drives long-term optimization of auditory coding to enhance the discrimination of communication signals. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31(9):271–89. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4355-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vehrencamp SL. Is song-type matching a conventional signal of aggressive intentions? Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. 2001;268(1476):1637–42. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2001.1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicario DS, Naqvi NH, Raksin JN. Behavioral discrimination of sexually dimorphic calls by male zebra finches requires an intact vocal motor pathway. Journal of Neurobiology. 2001;47(2):109–20. doi: 10.1002/neu.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignal C, Andru J, Mathevon N. Social context modulates behavioural and brain immediate early gene responses to sound in male songbird. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;22(4):949–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignal C, Mathevon N, Mottin S. Mate recognition by female zebra finch: Analysis of individuality in male call and first investigations on female decoding process. Behavioural Processes. 2008;77:191–8. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas A, Harding C, McGowan J, Snare R, Bogdan D. Noradrenergic neurotoxin, N-(2-chloroethyl)-N-ethyl-2-bromobenzylamine hydrochloride (DSP-4), treatment eliminates estrogenic effects on song responsiveness in female zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) Behavioral Neuroscience. 2008;122(5):1148–57. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.122.5.1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Brzozowska-Prechtl A, Karten HJ. Laminar and columnar auditory cortex in avian brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:28, 12676–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1006645107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil ZM, Murakami G, Pfaff DW. Reproductive behaviors: New developments in concepts and in molecular mechanisms progress in brain research. Progress in Brain Research. 2010;181:35–41. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)81003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilczynki W, Lynch K. Female sexual arousal in amphibians. Hormones and Behavior. 2011;59(5):630–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams H. Birdsong and singing behavior. In: Zeigler H Philip, Marler Peter., editors. Neuroscience of Birdsong. Cambridge Univerity Press; Cambridge: 2008. pp. 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield JC. Short-term changes in plasma-levels of hormones during establishment and defense of a breeding territory in male song sparrows, Melospiza-Melodia. Hormones and Behavior. 1985;19:174–87. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(85)90017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingfield JC, Hahn TP. Testosterone and territorial behavior in sedentary and migratory sparrows. Animal Behaviour. 1994;47(1):77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Moss SJ. Long-term and short-term electrophysiological effects of estrogen on the synaptic properties of hippocampal CA1 neurons. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12(8):3217–25. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-08-03217.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS. Estradiol mediates fluctuation in hippocampal synapse density during the estrous cycle in the adult. Journal of Neuroscience. 1992;12(7):2549–54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-07-02549.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS. Acute effects of estrogen on neuronal physiology. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2007;47:657–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, Gould E, Frankfurt M, McEwen BS. Naturally occurring spine density on adult hippocampal pyramidal neurons. 1996 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-12-04035.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoder KM, Vicario DS. Auditory discrimination and memory for conspecific vocal signals: a role for estrogen? Program No. 815.2/NNN7; 2010 Neuroscience Meeting Planner; San Diego, CA: Society for Neuroscience; 2010. Online. [Google Scholar]

- Zann R. The zebra finch: A synthesis of field and laboratory studies. New York: Oxford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]