Abstract

Albumin is the most abundant protein in blood where it has a pivotal role as a transporter of fatty acids and drugs. Like IgG, albumin has long serum half-life, protected from degradation by pH-dependent recycling mediated by interaction with the neonatal Fc receptor, FcRn. Although the FcRn interaction with IgG is well characterized at the atomic level, its interaction with albumin is not. Here we present structure-based modelling of the FcRn–albumin complex, supported by binding analysis of site-specific mutants, providing mechanistic evidence for the presence of pH-sensitive ionic networks at the interaction interface. These networks involve conserved histidines in both FcRn and albumin domain III. Histidines also contribute to intramolecular interactions that stabilize the otherwise flexible loops at both the interacting surfaces. Molecular details of the FcRn–albumin complex may guide the development of novel albumin variants with altered serum half-life as carriers of drugs.

Albumin transport proteins circulate in the blood and are protected from degradation by interaction with the neonatal Fc receptor. Andersen et al. investigate the albumin binding site of the neonatal Fc receptor and find pH sensitive ionic networks at the binding interface.

Albumin transport proteins circulate in the blood and are protected from degradation by interaction with the neonatal Fc receptor. Andersen et al. investigate the albumin binding site of the neonatal Fc receptor and find pH sensitive ionic networks at the binding interface.

Albumin is a multifunctional transporter of a range of different endogenous as well as exogenous compounds, such as ions, fatty acids, amino acids, hemin, bilirubin and various drugs1. It is the most abundant protein in blood and thus contributes to maintaining the osmotic pressure. The high serum concentration of albumin is due to the rate of synthesis that takes place in the liver and its interaction with the neonatal Fc receptor, abbreviated FcRn2,3. FcRn is a dual binding receptor that, in addition to albumin, binds IgG, and protects both proteins from intracellular degradation3,4,5. Thus, FcRn has a key role in prolonging their half-lives.

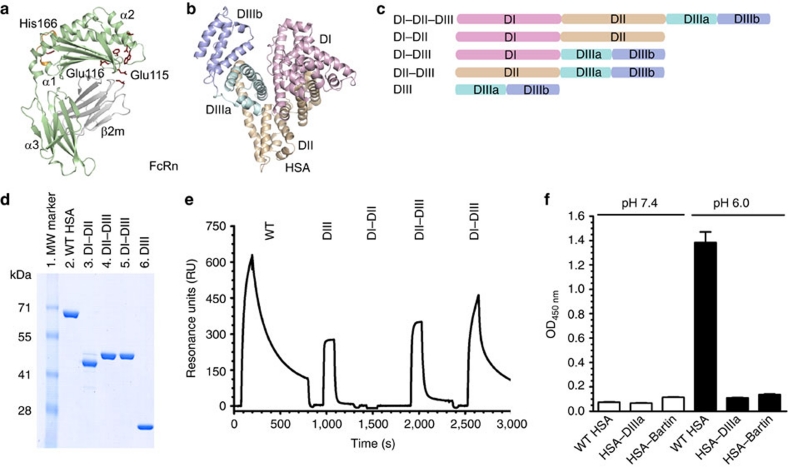

FcRn is a nonclassical major histocompatibility (MHC) class I molecule that consists of a unique transmembrane heavy chain (HC) that is non-covalently associated with the common β2-microglobulin (β2m). Crystal structures of FcRn show the extracellular part of the HC with an amino-terminal α1–α2 platform of eight antiparallel β-pleated strands topped by two long α-helices followed by the membrane proximal α3-domain (Fig. 1a)6,7,8. The β2m unit is tightly bound to residues located below the α1–α2 platform and to the α3-domain. Whereas classical MHC class I molecules bind to short peptides in their peptide-binding groove, located between the two α-helices on the α1-α2 platform, this groove is occluded and empty in FcRn7,8. Instead, the MHC class I fold of FcRn has evolved to bind to IgG and albumin.

Figure 1. Domain architecture of HSA and hFcRn binding properties of HSA hybrid molecules.

(a) Overall structure of hFcRn showing the location of the pH-dependent flexible loop (orange) and His-166 relative to the IgG binding site (red residues in ball-and-stick)23. (b) The crystal structure of full-length HSA shows three α-helical domains; DI (pink), DII (orange) and DIII (cyan/blue)20. The DIII is split into subdomains DIIIa (cyan) and DIIIb (blue). (c) Domain organization of constructed hybrid HSA molecules (DI–DII, DI–DIII, DII-DIII, DIII). (d) SDS–PAGE gel migration of the HSA domain variants. (e) Representative SPR sensorgrams of equal amounts of WT HSA and domain combinations injected over immobilized hFcRn at pH 6.0. (f) ELISA showing pH-dependent binding of 5 μg ml−1 of WT HSA, HSA–DIIIa and HSA–Bartin to hFcRn at pH 7.4 and pH 6.0. n=4. All data are presented as mean±s.d.

Both IgG and albumin bind to FcRn in a strictly pH-dependent manner, with binding at acidic and no binding or release at neutral pH (refs 2,7,9). The model of how the receptor mediates rescue from lysosomal degradation has been deduced from imaging studies of FcRn–IgG trafficking in live cells5,10,11,12. In short, FcRn, predominantly localized in acidic endosomal compartments, encounters proteins continuously taken up by fluid-phase endocytosis. The low pH in the vesicles allows ligand binding. Subsequently, FcRn-ligand complexes are exported to the cell surface, where exposure to the higher physiological pH of the bloodstream triggers release of the ligands by a so-called kiss-and-run exocytotic mechanism5,10. Proteins that do not bind to FcRn progress to lysosomes for proteolytic degradation.

A key role for FcRn in half-life regulation has been demonstrated using genetically modified mice, as mice lacking FcRn have serum levels of IgG and albumin that are four to five and two to three -fold lower than normal mice, respectively2,13. The cell types responsible for FcRn recycling have been revealed using mice conditionally deleted for FcRn in endothelial or haematopoietic cells that show serum levels of IgG and albumin four and two-fold lower than in normal mice, respectively14. A human example is familial hypercatabolic hypoproteinemia, where deficiency in FcRn expression results in abnormally low levels of both ligands15. Furthermore, variants of HSA with carboxy-terminal truncations have unusual low serum levels16. In line with this, the so-called HSA–Bartin variant, known to lack the C-terminal DIII except for the first 29 amino acids, shows severely reduced FcRn binding17,18.

Our molecular understanding of the FcRn–IgG interaction has been deduced from site-directed mutagenesis, and the atomic-resolution structure of a complex between rat FcRn and rat IgG2a Fc that reveals a key role for a cluster of amino acids in the IgG Fc elbow region (Ile-253, His-310 and His-435)4,5. These residues are highly conserved across species, and the involvement of the histidines explains the strict pH dependence of the interaction. Histidines are positively charged at pH 6.0, and can interact with the negatively charged Glu-115 and Glu-116 in the FcRn HC (Fig. 1a).

Although the FcRn–IgG interaction is very well characterized, the FcRn interaction with albumin is not. To gain detailed insight, we constructed a structural model of the complex between hFcRn and HSA based on available crystal structures, and, using site-directed mutagenesis, we targeted amino-acid residues in both molecules to identify key players. Domain DIII of HSA was confirmed as the principal binding domain, and a natural HSA variant (Casebrook), characterized by a single point mutation in a long loop connecting subdomains DIIIa and DIIIb19, showed reduced affinity for hFcRn. We identified three conserved histidine residues in albumin to be crucial for pH-dependent binding, one in each of subdomains DIIIa (His-464) and DIIIb (His-535), in addition to one in the aforementioned loop connecting the two (His-510). In addition, we reveal a regulatory role for His-166 in the α2-domain of hFcRn in stabilizing a flexible loop within the α1-domain of the receptor that forms an ordered structure at acidic pH required for efficient HSA binding. The structural modelling predicts that this loop binds in a crevice on the surface of HSA formed by the loop connecting the DIII subdomains and the last C-terminal α-helix. In particular, His-510 on HSA interacts with Glu-54 on hFcRn, and Glu-505 on HSA with His-166 of hFcRn. Extra loops on both molecules contribute to the interaction interface, again characterized by histidine-dependent pH-sensitive ionic networks. Our data present a network of interactions that gives a molecular basis for the pH-dependence of the binding, which is a prerequisite for FcRn-dependent recycling and half-life regulation of albumin.

Results

HSA DIIIb is crucial for pH-dependent binding to hFcRn

Albumin consists of three homologous domains (DI, DII and DIII), each comprising α-helices stabilized by a complex network of twelve cysteine residues forming six disulfide bridges20. The three domains are linked by loops and form a heart-shaped structure (Fig. 1b). To investigate how each individual domain contributes to hFcRn binding, several domain variants (DI–DIII, DII–DIII, DI–DII, DIII) as well as wild-type (WT) HSA (Fig. 1c) were expressed in yeast (Fig. 1d). The binding of each variant to immobilized recombinant hFcRn was measured by surface plasmon resonance (SPR). Equal amounts of the HSA variants were injected at pH 6.0 and pH 7.4. The HSA variant consisting solely of DIII bound hFcRn, whereas the variant lacking DIII did not bind to FcRn at all (Fig. 1e). Furthermore, the DI–DIII variant bound slightly stronger to hFcRn than DIII alone (Table 1). DII, on the other hand, did not seem to contribute to binding.

Table 1. SPR-derived kinetics for binding of HSA variants to hFcRn.

| Albumin variant | ka (103 per Ms) | kd (10−3 per s) | kD (μM)a | kD (μM)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | 5.9±0.1 | 7.0±0.2 | 1.1 | 2.4 |

| DIII | 2.6±0.0 | 72.0±0.0 | 27.6 | 17.4 |

| DI–DII | NDc | ND | ND | ND |

| DII–DIII | 1.4±0.2 | 30.0±0.2 | 21.4 | 22.3 |

| DI–DIII | 3.2±0.1 | 45.2±0.1 | 14.1 | 15.0 |

| Q417A | 5.0±0.0 | 11.1±0.1 | 2.2 | 3.3 |

| H440Q | 5.1±0.0 | 7.0±0.1 | 1.3 | 2.5 |

| H464Q | NAd | NA | NA | 14.1 |

| D494N (Casebrook) | 3.8±0.0 | 8.5±0.0 | 2.2 | 4.6 |

| D494A | 5.9±0.1 | 21.0±0.0 | 3.6 | 4.2 |

| D494Q | 5.4±0.2 | 25.5±0.1 | 4.7 | 5.3 |

| E495Q | 4.2±0.0 | 13.1±0.0 | 3.1 | 3.2 |

| E495A | 3.8±0.1 | 13.0±0.0 | 3.4 | 3.1 |

| T496A | 5.4±0.0 | 7.6±0.2 | 1.4 | 2.5 |

| D494N/T496A | 5.4±0.1 | 8.5±0.2 | 1.5 | 2.5 |

| Casebrook | 3.6±0.1 | 9.7±0.1 | 2.7 | 3.8 |

| P499A | 2.6±0.0 | 12.1±0.0 | 4.6 | 3.9 |

| K500A | 14.3±0.2 | 47.8±0.0 | 33.4 | 25.0 |

| E501A | 5.1±0.0 | 9.8±0.0 | 1.9 | 2.6 |

| H510Q | NA | NA | NA | 12.1 |

| H535Q | NA | NA | NA | 16.2 |

| K536A | 4.4±0.2 | 9.3±0.1 | 2.1 | 3.7 |

| P537A | 3.7±0.1 | 14.3±0.2 | 3.9 | 5.5 |

| K538A | 3.9±0.0 | 7.1±0.0 | 1.8 | 2.9 |

| HSA 568Stop | NA | NA | NA | 17.0 |

| HSA DIIIa |

ND |

ND |

ND |

ND |

aThe kinetic rate constants were obtained using a simple first-order (1:1) Langmuir bimolecular interaction model, which assumes that one HSA molecule binds one FcRn. The kinetic values represent the average of triplicates.

bThe steady-state affinity constant was obtained using an equilibrium (Req) binding model supplied by the BIAevaluation 4.1 software. The affinities derived from equilibrium binding data represent the average of triplicates.

cND, not determined because of no or very weak binding.

dNA, not acquired because of fast binding kinetics.

Each of the three HSA domains has two subdomains, a and b. To address the importance of the C-terminal subdomain DIIIb, we engineered an HSA variant where this domain was deleted (HSA–DIIIa). Lack of DIIIb completely abolished hFcRn binding (Fig. 1f). For comparison, we included a recombinant version of HSA–Bartin, which lacks DIII except from the first 29 amino acids17. These results demonstrate that an intact DIII is crucial for receptor binding.

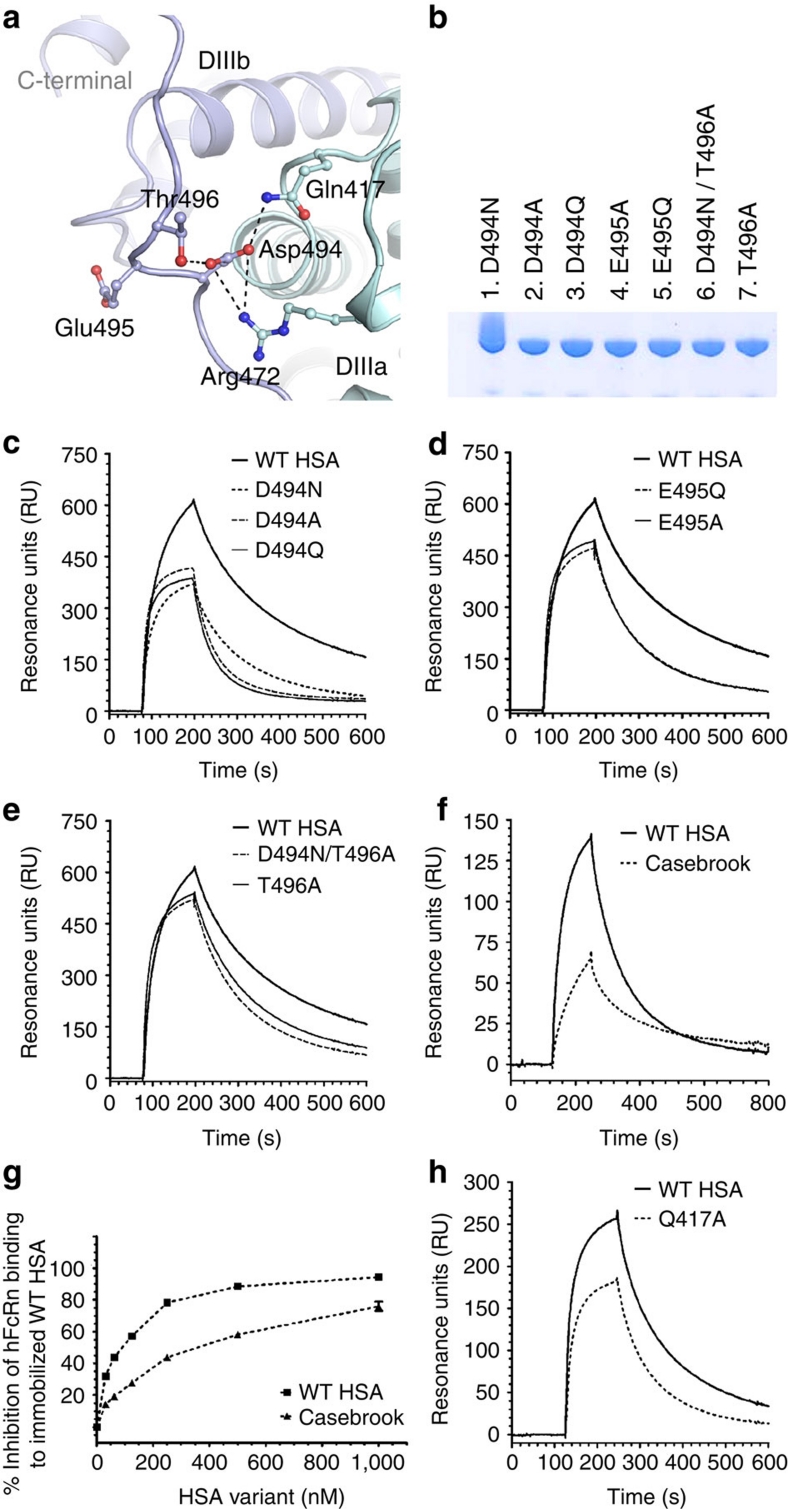

A point mutation alters hFcRn binding in HSA Casebrook

HSA is normally non-glycosylated, but a few exceptions exist because of rare mutations16. One such variant (Casebrook) has a single nucleotide substitution that changes the coding from Asp to Asn at amino-acid residue 494 (ref. 19), localized in the stretch of amino acids (residue 490–510) that form a long loop connecting subdomains DIIIa and DIIIb (Figs 2a and 3a). This point mutation introduces a glycosylation motif (494Asn-Glu-Thr496) and attachment of an N-linked oligosaccharide. We studied migration in SDS–PAGE and hFcRn binding of a number of recombinant HSA variants that allowed us to dissect the role of the oligosaccharide and individual amino acids at 494Asn-Glu-Thr496. The recombinant version of Casebrook (D494N) migrated more slowly than WT HSA in SDS–PAGE, which reflects attachment of oligosaccharides (Fig. 2b). Moreover, in six variants, D494A, D494Q, E495Q, E495A, T496A and D494N/T496A, the glycosylation motif was disrupted, and consequently, all of these mutants migrated like their WT counterpart (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. The structural implications of HSA Casebrook on hFcRn binding.

(a) Close-up view of the interaction network around Asp-494 in HSA. Asp-494 is located in the loop connecting subdomain DIIIa (cyan) and DIIIb (blue). Asp-494 forms an ionic interaction with Arg-472 and a hydrogen-bond interaction with Gln-417, both of which are located in subdomain DIIIa. Asp-494 also forms a hydrogen bond with Thr-496, thus stabilizing the loop connecting DIIIa and DIIIb. (b) SDS–PAGE gel migration of the mutants D494N, D494A, D494Q, E495Q, E495A, T496A and D494N/T496A. (c) Representative SPR sensorgrams showing binding of immobilized hFcRn to 1 μM of WT HSA and recombinantly produced Casebrook (D494N), D494A and D494Q. (d) E495Q and E495A and (e) T496A and D494N/T496A at pH 6.0. (f) Representative SPR sensorgrams of immobilized hFcRn binding to 1 μM of WT HSA and Casebrook isolated from a heterozygote patient. (g) Competitive binding of WT HSA and Casebrook to hFcRn at pH 6.0. The receptor (100 nM) was injected in the presence of titrated amounts of WT or Casebrook HSA (0.015–1,000 nM) over immobilized HSA. (h) SPR sensorgrams showing binding of immobilized hFcRn to 1 μM of WT HSA and Q417A at pH 6.0.

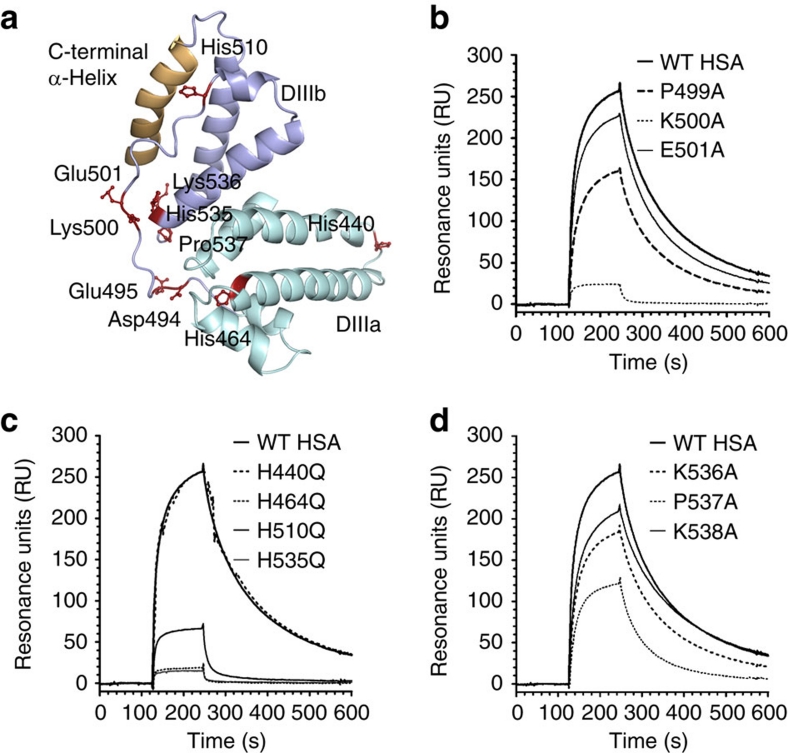

Figure 3. Conserved histidines are fundamental for binding to hFcRn.

(a) Structural location of selected residues in DIII of HSA. Residues in the loop connecting the subdomains DIIIa and DIIIb selected for mutagenesis (Asp-494, Glu-495, Lys-500 and Glu-501) as well as extra residues close to the connecting loop, such as the conserved histidines (His-464, His-510 and His-536), Lys-536 and Pro-537 are displayed as ball-and-stick (maroon). The non-conserved His-440 is distally localized. The last C-terminal α-helix is highlighted in yellow. Representative SPR sensorgrams showing binding of immobilized hFcRn to 1 μM of WT HSA and (b) P499A, K500A and E501A, and (c) H440Q, H464Q, H510Q and H535Q as well as (d) K536A, P537A and K538A at acidic pH (6.0).

All variants were tested for binding to immobilized hFcRn by SPR, and distinct binding differences were detected at acidic pH with a hierarchy from strongest to weakest binding as follows; WT>T496A>D494N/T496A>D494N>E495Q>E495A>D494A>D494Q (Fig. 2c–f; Table 1). The same trend was obtained by ELISA (Supplementary Fig. S1). The binding kinetics revealed major differences in dissociation rates for most mutants, while recombinant Casebrook (D494N) showed a twofold reduced affinity resulting from both altered association and dissociation constants. Mutation of Asp-494 and Glu-495 to a neutral alanine or a glutamine had a large effect on receptor binding, whereas mutation of the flanking Thr-496 had only a small effect. The HSA Casebrook variant isolated from a heterozygous individual bound hFcRn similar to its recombinant counterpart (Fig. 2f; Supplementary Fig. S2; Table 1).

The Casebrook variant is present at a two to three-fold lower level than normal HSA in serum of heterozygous individuals19. To mimic an in vivo situation where the Casebrook variant exists in the presence of large amounts of WT HSA that competes for FcRn binding, we used a competitive SPR-based assay and found that the ability of the natural Casebrook variant to compete for receptor binding was reduced by almost 50% compared with HSA WT (Fig. 2g), a finding that mirrors the twofold reduction in binding affinity (Table 1).

Structural implications of HSA Casebrook

To investigate whether the HSA mutants (T496A, D494N/T496A, D494N, E495Q, E495A, D494A and D494Q) had any major impact on the global structure, their secondary structural elements were determined by circular dichroism (CD). No major difference from that of WT HSA was observed for any of the mutants at either pH 7.4 or pH 6.0 (Supplementary Fig. S3; Supplementary Table S1).

Next, we inspected a crystal structure of HSA20, and found Asp-494 to be involved in an intramolecular network of polar interactions involving amino acids in both DIIIa and DIIIb (Fig. 2a). The carboxylic side chain of Asp-494 forms a charged-stabilized salt-bridge with Arg-472 as well as hydrogen bonds with both Gln-417 and Thr-496. N-linked glycosylation of Asn-494 will reduce its hydrogen-bonding capacity and eliminate the negative component of the salt-bridge, which may be important for stabilizing the loop. In support of this is the finding that a Q417A mutation also shows twofold reduced binding affinity for hFcRn (Fig. 2h; Table 1). Furthermore, glycosylation, that is, an introduction of a bulky moiety, may destabilize the N-terminal end of the loop encompassing residues 490–495, and thus affect its conformation and ability to interact with hFcRn.

Besides Asp-494, Glu-495 and Thr-496 at the N-terminal end of the loop, we targeted two charged residues (Lys-500 and Glu-501) in addition to Pro-499 in the middle of the loop (Fig. 3a) by mutagenesis and investigated the effect on hFcRn binding. We found moderate effects of P499A and E501A, while mutation of the positively charged Lys-500 dramatically reduced binding to the receptor by more than 30-fold (Fig. 3b; Table 1).

Crucial roles of conserved histidines in HSA DIII

Guided by the fact that histidine residues are key players in the strictly pH-dependent IgG–FcRn interaction4,5, we assessed the role of the four histidines found within HSA DIII. Of these, three are highly conserved across species (His-464, His-510 and His-535) and one is not (His-440) (Supplementary Table S2). Whereas His-440 and His-464 are found within DIIIa, His-510 is localized to the end of the loop connecting DIIIa and DIIIb, and His-535 is found in one of the α-helices of DIIIb (Fig. 3a). All four histidines were mutated individually to glutamine, and the corresponding mutants were expressed in yeast (Supplementary Fig. S4) before they were tested for binding to hFcRn at pH 6.0. Mutation of each of the three conserved histidines almost completely abolished binding, whereas mutation of the non-conserved His-440 did not (Fig. 3c; Table 1). Thus, we pinpoint these three histidines within DIII as fundamental for pH-dependent hFcRn binding, which parallels the requirement for histidines in the Fc region of IgG (His-310 and His-435)4,5.

Furthermore, alanine substitutions of two positively charged lysines (Lys-536 and Lys-538) and Pro-537 in the vicinity of His-535 were also shown to moderately attenuate binding to hFcRn (Fig 3d; Table 1). Taken together, the binding data define a core structural area on DIII important for pH-dependent hFcRn binding.

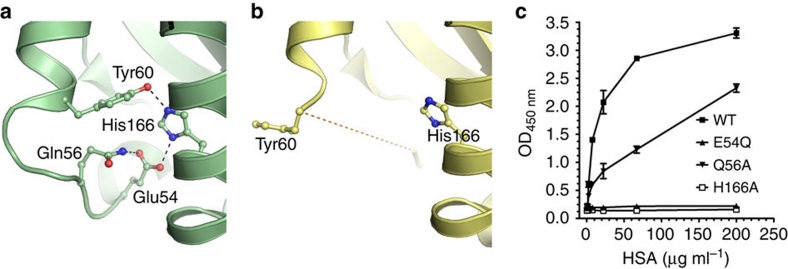

Mapping the HSA binding site on hFcRn

We have previously identified a highly conserved histidine residue localized to the α2-domain of both mouse and human FcRn HC to be crucial for albumin binding (His-168 and His-166, respectively)21,22. To obtain a molecular explanation, we inspected a crystal structure of hFcRn that was recently solved under acidic conditions (pH 4.2) (Fig. 1a)23. We found that His-166 is engaged in a network of intramolecular interactions that involves charge-stabilized hydrogen bonds with Glu-54 and Tyr-60 found on a surface-exposed loop within the α1-domain (residue 51–60) (Fig. 4a). At low pH, His-166 will carry a positive charge, and we propose that uncharged His-166 will lose its interactions with Glu-54 and Tyr-60 at physiological pH, which will result in a more flexible loop. This explanation is supported by the fact that this loop region is structurally disordered in the crystal structure of hFcRn solved at basic pH (pH 8.5) (Fig. 4b). Further, the corresponding loop is also ordered with a defined conformation in the rat FcRn–IgG2a Fc co-crystal structure solved at acidic pH (ref. 6). A comparison of the two hFcRn structures at low and high pH suggests a pivotal regulatory role of His-166 in locking and release of the flexible loop between Trp-51 and Tyr-60 (Fig. 4a,b).

Figure 4. His-166 of hFcRn stabilizes a flexible loop in a pH-dependent manner.

Close-up view of the FcRn HC loop area at different pH conditions. (a) At low pH (4.2), the positively charged His-166 forms charge-stabilized hydrogen-bond interactions with Glu-54 and Tyr-60 within the surface-exposed loop in hFcRn23. (b) At high pH (8.2), the uncharged His-166 looses the interactions with Glu-54 and Tyr-60, and the loop between residues Trp-51 and Tyr-60 becomes flexible and structurally disordered (represented by the dashed line)8. (c) Binding of 0.5 μg ml−1 of hFcRn WT and mutants (E54Q, Q56A and H166A) to titrated amount of HSA (0.3–200 μg ml−1) coated in ELISA wells at pH 6.0. n=4. All data are presented as mean±s.d.

Glu-54 is also involved in an interaction with Gln-56 in the crystal structure of hFcRn (Fig. 4a). To address the importance of these residues in loop stabilization and HSA binding, both were individually mutated to glutamine or alanine, respectively, and the resulting receptor variants (hFcRn E54Q and hFcRn Q56A) were tested for binding to HSA by ELISA at pH 6.0. The impact of E54Q was striking, as almost no receptor binding to HSA was detected, whereas Q56A partially lost binding to HSA (Fig. 4c). Thus, our data demonstrate that His-166 stabilizes the α1-domain loop of hFcRn in a pH-dependent fashion through binding to Glu54, and that an ordered structure of this loop at acidic pH is indispensable for efficient HSA binding.

A proposed mode of binding

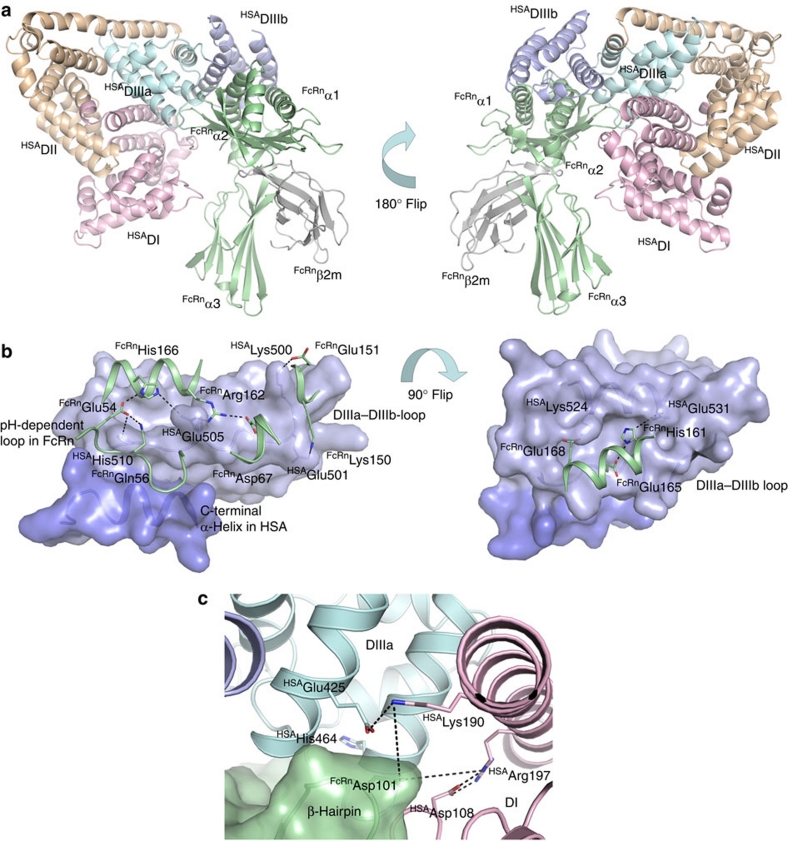

On the basis of the binding studies, we used the ZDOCK algorithm to create a structural model of the hFcRn–HSA complex using two different crystal structures of hFcRn; the 2.7 Å resolution structure solved at pH 8.2 and the 2.6 Å resolution structure solved at pH 4.2 (refs 8, 23). The program was run with bias towards docking solutions involving His-161 and His-166 in hFcRn and the residues His-464, His-510 and His-535 in HSA in the protein–protein interface20. The software returned one model for the docking of DIII against hFcRn with an ordered loop at pH 4.2 and eight models for hFcRn at pH 8.2, lacking loop residues 52–59. Of these eight models, five evidently showed incompatible poses as judged by the position of HSA DI and DII, and were rejected. The three remaining models were closely related and had the same general structural pose. Superimposing of the low pH form of hFcRn on these then showed that the structured loop made no severe conflicts with the docked HSA.

The final selected model reveals interaction areas that fit very well with the obtained binding data (Fig. 5a). Particularly, the long loop between subdomains DIIIa and DIIIb (490–510) as well as the last C-terminal α-helix of HSA form a crevice on the surface of HSA into which the pH-dependent and flexible loop in hFcRn (residues 51–60) may bind (Fig. 5b). The structure of hFcRn shows that His-166 stabilizes this loop through an intramolecular interaction with Glu-54 (Fig. 4a); however, the model suggests that His-166 may additionally be engaged in binding to Glu-505 of HSA (Fig. 5b). Glu-505 may also interact with Arg-162 of the receptor. A key role of His-510 is supported by the fact that it is predicted to interact with Glu-54 within the pH-dependent α1-domain loop (Fig. 5b). Mutation of His-510 (H510Q) reduced binding by 14-fold (Fig. 3c; Table 1). Thus, His-166 in hFcRn and His-510 in HSA seem to be involved in regulating an ionic network in the core of the hFcRn–HSA interaction interface.

Figure 5. A proposed hFcRn-HSA docking model.

(a) An overview of the docked molecules in two orientations showing the FcRn HC (green), β2m (grey) and the three HSA α-helical domains DI (pink), DII (orange) and DIII (cyan/blue). The HSA DIII is split into DIIIa (cyan) and DIIIb (blue). (b) Close-up view of the interaction interface between hFcRn (green cartoon) and HSA (blue surface) in the docking model. The C-terminal end of HSA (dark blue) and the loop corresponding to residues 490–510 between subdomains DIIIa and DIIIb form a crevice on the HSA surface into which the pH-dependent and flexible loop in hFcRn (residues 51–59) might bind. His-166 of hFcRn may form strong, charge-stabilized interactions with HSA residues Glu-54 and Glu-505. HSA Glu-505 could further interact with hFcRn Arg-162. Possible salt-bridges are formed between Lys-150 and Glu-151 of hFcRn with Glu-501 and Lys-500 of HSA. A cleft on the HSA surface is formed between the loop connecting DIIIa and DIIIb and the α-helix encompassing residues 520–535. His-161 of hFcRn may interact with Glu-531 of HSA at low pH, and the complex could be further reinforced by the salt-bridge between hFcRn Glu-168 and HSA Lys-524. (c) Interaction interface between hFcRn (green surface) and HSA (pink, blue and cyan cartoon) in the docking model. A β-hairpin loop in hFcRn is wedged in-between domains DI (pink) and DIIIa (cyan) in HSA. The hFcRn Asp-110 could be a partner to either Lys-190 or Arg-197 of HSA following some structural rearrangements in this interface. The conserved His-464 is located in the DIIIa α-helix contacting the β-hairpin loop.

Furthermore, the predicted involvement of the C-terminal α-helix of HSA is supported by the finding that deletion of the last 17 amino acids of DIIIb (568Stop) reduced binding affinity to hFcRn by more than 17-fold (Supplementary Fig. 5; Table 1). The model also predicts salt-bridges between Lys-150 and Glu-151 in hFcRn on one hand and Glu-501 and Lys-500 in HSA (Fig. 5b). This is in line with the binding data that show reduced binding capacity of HSA variants mutated at these positions (Fig. 3b).

Another cleft on the surface of HSA is formed between the DIIIa–DIIIb connecting loop and one of the other α-helices of DIIIb (residues 520–535). Here His-161 of hFcRn may interact with Glu-531 at acidic pH (Fig. 5b). This is in agreement with our previous finding where a tenfold reduced binding affinity was found when His-161 was mutated22. The complex could be further reinforced by a salt-bridge formed between Glu-168 of hFcRn and Lys-524 of DIII, a prediction that is supported by the fact that mutation of Glu-168 moderately reduces binding to HSA (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Moreover, His-535 may interact favourably with Phe-157 while His-464 is localized close to a β-hairpin within hFcRn encompassing residues 99–102 that is wedged in-between DI and DIIIa in HSA (Fig. 5c). Here hFcRn Asp-101 has several possible partners in DI such as Arg-197 and Lys-190, however, they must necessarily undergo some conformational changes in order to get close to Asp-101. Interestingly, this β-hairpin has two different conformations in the low and high pH-forms of hFcRn8,23, suggesting that Asp-101 is indeed located in a flexible element of hFcRn.

Discussion

FcRn has evolved to protect IgG and albumin from catabolism5,18,22. Although FcRn binding to IgG has been studied in great detail for decades, its recently discovered interaction with albumin is poorly understood at the molecular level. In the present study, we provide mechanistic evidence for the importance of several interaction interfaces on both molecules, revealing how FcRn and HSA interact in a pH-sensitive fashion that facilitates cellular recycling.

Our finding that DIII alone, unlike DI-DII, could bind to the receptor, modulated by pH, conclusively shows that DIII harbours the principal core-binding site for FcRn, as in agreement with previous reports9,17. However, we also show that binding to DIII alone is considerably weaker than that for full-length HSA, a finding that suggests that there may be a moderate contribution to receptor binding from DI or DII, either directly or indirectly. Furthermore, a DI–DIII construct-bound hFcRn slightly stronger than DIII. One may speculate that this is due to structural stabilization of DIII or that DI interacts with hFcRn when fused to DIII, although DI in the DI–DIII fusion has a different location than DI in WT HSA. Interestingly, the model suggests that there may be a minor interaction between DI and hFcRn.

Several naturally occurring HSA variants, with mutations in DIII, have altered blood levels16. One such variant, Casebrook, with a point mutation that introduces an N-linked oligosaccharide attachment site, constitutes about 35% of total HSA in heterozygous carriers19. Introduction of the mutation in rabbit albumin resulted in a 50% reduction in half-life when injected into rabbits24. On the basis of these observations, we engineered an HSA variant mimicking Casebrook and found that it had a twofold reduced affinity for hFcRn. This was indeed also the case for Casebrook isolated from a heterozygous individual.

When inspecting the crystal structure of hFcRn solved at acidic pH, we found the partially exposed and protonated His-166 to be engaged in stabilizing a loop that was disordered at basic pH, through binding to an acidic (Glu-54) and a polar (Tyr-60) amino acid. The disorder of the loop is likely explained by loss of protonation of His-166 at basic pH, which then regulates the flexibility and conformation of the loop in a pH-dependent manner.

Four histidine residues in HSA DIII were individually mutated to glutamines, and three highly conserved histidines (His-464, His-510 and His-535; Supplementary Table S2) were found to be important for binding at acidic pH. This fact as well as the prerequisite for hFcRn His-166 for binding to HSA, were used to guide the hFcRn–HSA models output by the docking algorithm. The best model reveals that DIII forms the major interaction interface with a possible minor contribution from DI. Furthermore, IgG and HSA bind to hFcRn to non-overlapping sites without interfering with binding of each other9,21, a fact that fits well with the docking model where no hindrance exists for simultaneous binding (Supplementary Fig. S7). Whether or not HSA binding induces conformation changes in the receptor or vice versa cannot be excluded.

Following inspection of the docking model, no direct contact was found between hFcRn and the oligosaccharide attachment site (Asn-494) present in HSA Casebrook. However, Asp-494 is part of an extended loop (490–510) connecting DIIIa and DIIIb, and it is very likely that alteration of the composition at the N-terminal end of the loop induces conformation changes in the loop at large. The structural importance of Asp-494 and Glu-495 is supported by the fact that both residues are highly conserved across species (Supplementary Table S2). Notably, the structural model suggests that several residues in the C-terminal end of the loop are in direct contact with the α1–α2-platform of the receptor, with predicted key residues being His-510 and Glu-505 in HSA, as well as Glu-54 in hFcRn.

Of the remaining two conserved histidines on DIII, His-535 may reinforce the HSA–hFcRn complex by aromatic stacking or stabilization of this important loop. His-464, on the other hand, may interact, directly or indirectly, with a flexible β-hairpin element in hFcRn. Interestingly, this β-hairpin loop is the most flexible part of hFcRn, except for the pH-dependent loop stabilized by His-166, as judged by a comparison of low and high pH crystal structures. The flexible β-hairpin is in contact with both the α-helix in HSA that contains His-464 as well as a long loop in DI, suggesting an indirect conformational 'tuning' of the hFcRn–HSA interface involving DI and DIIIa. Our data support a study showing that mutation of the conserved histidines to alanine resulted in increased clearance of HSA DIII fused to antibody fragments when injected into mice25.

The principal function of albumin is to transport fatty acids that are bound asymmetrically to hydrophobic pockets within or between the three domains1,26,27. DIII harbours two high affinity binding sites, and the fatty acids bind close to the loop between DIIIa and DIIIb, which also includes several residues found to affect hFcRn binding. Comparison of the fatty acid bound and free states of HSA20,27, shows no substantial rearrangements within DIII, but a considerable shift in orientation of DI relative to DIII (Supplementary Fig. S8). In effect, superimposing DIII in the fatty acid binding HSA onto the corresponding domain in our structural model reveals that DI may move away from hFcRn when binding to fatty acids.

The half-life regulatory function of FcRn may be utilized for therapy, as discussed elsewhere28,29. Obviously, drugs may fail to show convincing effects in vivo if their half-lives are short as a consequence of their size being below the renal clearance threshold30,31. This limits transition from lead candidate to drugs on the market. A solution may be genetic fusion of the therapeutics to albumin or the IgG Fc, which have shown to improve biodistribution and pharmacokinetics29.

The serum half-life of IgG may also be altered, as demonstrated for engineered IgGs with mutations in their IgG1 Fc that result in improved pH-dependent FcRn binding, and consequently extended half-life in vivo4,5,32. No examples have so far been presented for albumin, except for the observation that mouse albumin binds more strongly to hFcRn than HSA21. The structural hFcRn–HSA model presented in this study may guide the development of HSA variants with altered half-life, which could be attractive for delivery of both chemical and biological drugs.

Tumours and inflamed tissues show increased accumulation of albumin as a result of leaky capillaries and defective lymphatic drainage33. Consequently, albumin-based therapeutics or diagnostics accumulate at the site of tumour or inflammation. Because of tissue toxicity of the fused molecules, fine-tuning of albumin half-life may be an attractive approach to improve tumour targeting and imaging, as previously shown for IgGs with attenuated affinity for FcRn34,35. The HSA variants described in this paper, with substantially reduced or intermediate FcRn binding affinities, may serve as attractive candidates.

Methods

Production of hFcRn variants

Production of hFcRn has previously been described36. Gene-segments encoding mutant hFcRn variants (E54Q, Q56A and E168A) were ordered from Genscript, subcloned and produced as described36.

Production of HSA variants

Escherichia coli DH5a37 was used for manipulation, propagation and preparation of HSA DNA. Expression cassettes (NotI cassettes) contain the Saccharomyces cerevisiae PRB1 promoter, a leader sequence (MKWVSFISLLFLFSSAYSRSLDKR (FL) fused in-frame with the HSA gene (ALB) and the S. cerevisiae ADH1 terminator sequence. Plasmids were generated using standard cloning techniques (Supplementary Table S3) or a mixture of this and gap-repair in S. cerevisiae (Supplementary Table S4). DNAs containing mutations within the ALB gene (GeneArt GmbH or DNA2.0) were subcloned into NcoI/SacI-digested pDB2243 (a derivative of pAYE316 (ref. 38) to create plasmids pDB3876–pDB3882 (Supplementary Table S3). Expression cassettes (NotI fragments) were obtained from pDB3876–pDB3886 and ligated into NotI-digested pSAC35 (ref. 39 to generate pDB3887–pDB3893 (Supplementary Table S3).

Plasmids used for gap-repair were generated by digesting pDB2244 (containing NotI cassette from pDB2243 in NotI-digested pSAC35) with SwaI and the 9.545 kb fragment (containing the S. cerevisiae LEU2 gene, and the HSA NotI cassette) was ligated to produce pDB3927. Expression cassettes were generated using DNA fragments (NcoI/Bsu36I, AvrII/SphI or SacI/Sph) containing mutations, subcloned into NcoI/Bsu36I, AvrII/SphI or SacI/Sph-digested pDB3927 (Supplementary Table S4), and then generated in S. cerevisae by gap repair.

A truncated HSA variant (residues 1-567) was generated by PCR and gap-repair using the oligonucleotides xAP314 and xAP307 (5′-CTCAAGAAACCTAGGAAAAGTGGGCAGC-3′ and 5′-GAATTAAGCTTATTATAAGCCTAAGGCAGCTTGACTTGCAGCAACAAGTTTTTTACCCTCCTCGGCTTAGCAGG-3′) and Phusion Polymerase (New England Biolabs), to amplify a 493 bp fragment from pDB3927. A stop codon was engineered into xAP307 so that translation terminated following a.a. 567. The fragment was digested with AvrII/Bsu36I and subcloned into AvrII/Bsu36I-digested pDB3927 to produce pDB4557, which was used for gap-repair experiments.

Plasmids and S. cerevisiae strains expressing HSA DI–DII (residues 1–387) and DII–DIII (residues 183–585) are described40. The plasmid for DI–DIII (residues 1–194 and 381–585, respectively) was generated using PCR and gap-repair in S. cerevisiae. Two DNA fragments were amplified by PCR from pDB2244 using oligonucleotide pairs xAP032/xAP058 (5′-ATGTCTGCCCCTAAGAAGATCGTC-3′ and 5′-GTTTGATTAAATTCTGAGGCTCTTCCACGGCAGACGAAGCCTTCCCTTCATC-3′) and xAP059/xAP033 (5′-GTGGAAGAGCCTCAGAATTTAATCAAAC-3′ and (5′-GTGGAAGAGCCTCAGAATTTAATCAAAC-3′). PCR fragments were purified using a Qiagen PCR Purification kit before being used with Acc65I/BamHI-digested pDB3936 to co-transform S. cerevisiae.

A plasmid encoding HSA DIII (residues 381–585) (pDB3855) was generated using a BfrI/HindIII fragment (containing 3′ region of the PRB1 promoter and DNA encoding the S. cerevisiae leader sequence and DIII) (GeneArt) ligated into BfrI/HindIII pDB2923 (ref. 41) to create pDB3827. The HSA DIII cassette was obtained as a NotI fragment from pDB3827 and then ligated into pSAC35 to produce pDB3855, which was used to transform S. cerevisiae.

Production of HSA variants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae

The plasmids pDB3887–pDB3893 (Supplementary Table S4) were used to transform S. cerevisiae D638cir0 (pmt1 mutant derived of DYB7 (ref. 42)), as described in ref. 43. Transformation of D638cir0 by gap-repair was done by digesting the plasmids with BstEII/BsrBI before each digest was purified using the Qiagen PCR Purification kit. 100 ng of each BstEII/BsrBI-digested pDB3927 derivative was mixed with 100 ng Acc65I/BamHI pDB3936 before being used to transform D638cir0 as described in ref. 43.

10 ml BMMD medium (2% w/v glucose) was inoculated with yeast and grown for 48 h at 30 °C with shaking at 200 r.p.m. 4 ml of each culture was used to inoculate 2×200 ml BMMD media43, and grown for 120 h at 30°C with shaking at 200 r.p.m.. Cells were collected by filtration through 0.2-μm vacuum filter membranes (Millipore), and the supernatant retained was concentrated using a Pall Filtron LV system fitted with an Omega 10 kDa filter (LV Centramate cassette, Pall Filtron).

HSA variants were purified using the AlbuPure matrix (ProMetic BioSciences) where supernatants were applied to packed bed pre-equilibrated with 50 mM sodium acetate pH 5.3, washed with 10 column volume (CV) of equilibration buffer followed by 50 mM ammonium acetate pH 8.0 (10 CV). Protein was eluted with 50 mM ammonium acetate, 10 mM octanoate pH 8.0, 50 mM ammonium acetate, 30 mM sodium octanoate pH 8.0 or 200 mM potassium thiocyanate. Eluted fractions were concentrated and filtered against 10 CV of 50 mM NaCl using Vivaspin20 10 kDa PES (Sartorius). HSA variants were quantified by GP–HPLC using a TSK G3000SWXL column (Tosoh Bioscience).

Samples were chromatographed in 25 mM sodium phosphate, 100 mM sodium sulphate, 0.05% (w/v) sodium azide, pH 7.0 at 1 ml min−1, and quantified by UV detection at 280 nm, relative to a HSA standard. Proteins were analysed using precast NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris gels run with MOPS SDS buffer (Invitrogen). Samples (1 μg) were diluted 1:1 with reducing sample buffer (NuPAGE LDS sample buffer) and heated to 70 °C for 5 min. Electrophoresis was performed for 50 min at 200 V, and gels were stained with InstantBlue protein stain (Expedeon).

Construction of GST-tagged HSA variants

A HSA variant lacking subdomain DIIIb (HSA–DIIIa; residues 1–513) was constructed by amplifying a fragment using oligonucleotide pairs HSA_Forw (5′-TAAGAATTCACCATGAAGTGGGTAACCTTTATTTCC-3′) and HSA_Rev513 (5′-AATACTCGAGTATATCTGCATGGAAGGT-3′) and the vector pcDNA3-HSAWT–GST–oriP, previously described17. The DNA fragment with flanking restriction sites (EcoRI/XhoI) was ligated into pcDNA–GST–oriP in-frame of a DNA encoding glutathione-S-transferase (GST) from Schistosoma japonicum (pcDNA3–HSADIIIa–GST–oriP). GST-tagged WT HSA, HSA–DIIIa and HSA–Bartin were produced as previously reported17.

Isolation of HSA Casebrook

Citrate anti-coagulated plasma was dialysed against 16 mM sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.2) and applied to a 2.6 cm×15 cm column of DEAE Sephadex A50 equilibrated in the same buffer. Bound HSA was eluted with 600 ml of this buffer using a pH gradient (5.2–4.4) at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. The total HSA eluted as a single peak where the leading and trailing third of the peak were pooled separately, then concentrated, dialysed and freeze-dried. Analysis on SDS–PAGE showed these were ∼95% pure WT and HSA Casebrook, respectively.

ELISA

Microtiter wells (Nunc) were coated with 100 μl of titrated amounts of HSA variants (0.7–100 μg ml−1), incubated overnight at 4 °C, and washed 3 times with PBS/0.005% Tween 20 (PBS/T), pH 6.0. Wells were then blocked with 4% skimmed milk (Acumedia) for 1 h at room temperature (RT) and washed as above. GST-tagged hFcRn (0.5 μg ml−1) diluted in PBS/T pH 6.0/4% skimmed milk was added for 1 h at RT before washing as above. Bound receptor was detected using a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-GST antibody (GE Healthcare), added for 1 h at RT followed by washing with PBS/T pH 6.0, and then visualized using tetramethylbenzidine substrate (Calbiochem). The coating levels of HSA variants were controlled using a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-HSA antibody (Abcam). Binding of 1 μg ml−1 of HSA WT-GST, HSA–DIIIA–GST and HSA–Bartin was measured using hFcRn (2 μl ml−1) coated in wells following by washing and detection as described above.

SPR

A Biacore 3000 instrument (GE Healthcare) was used with CM5 sensor chips coupled with hFcRn–GST (∼1,000–2,000 RU) using amine coupling chemistry as described by the manufacturer. The coupling was performed by injecting 10–12 μg ml−1 of each protein into 10 mM sodium acetate, pH 4.5 (GE Healthcare). Phosphate buffer (67 mM phosphate buffer, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.005% Tween 20) at pH 6.0 or 7.4, or HBS-P buffer (0.01 M HEPES, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.005% surfactant P20) at pH 7.4 were used as running buffer and dilution buffer. Kinetic measurements were performed by injecting serial dilutions of HSA variants (80–0.1 μM) at 25 °C with 50 μl min−1. All data were zero adjusted, and the reference cell value was subtracted. Kinetics were calculated using the Langmuir 1:1 ligand model and steady-state affinity model provided by the BIAevaluation 4.1 software. Competitive binding was measured by injecting hFcRn (100 nM) alone or together with HSA variants (0.015–1,000 nM) over immobilized HSA (∼2,000–2,500 RU).

CD spectroscopy

CD spectra were recorded using a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter (Jasco International) calibrated with ammonium d-camphor-10-sulfonate (Icatayama Chemicals). Measurements were performed with HSA (2 mg ml−1) in 10 mM PBS (pH 6.0) without NaCl added, at 23 °C using a quartz cuvette (Starna) with a path length of 0.1 cm. Each sample was scanned 7 times at 20 nm min−1 (bandwidth of 1 nm, response time of 1 s) with wavelength range set to 190–260 nm. The data were averaged and the spectrum of a sample-free control was subtracted. Secondary structural elements were calculated using the neural network program CDNN version 2.1 and the supplied neural network based on the 33-member basis set44.

Docking procedure

Docking models of HSA and hFcRn were generated using the ZDOCK Fast Fourier Transform docking program45. The coordinates for HSA DIII (a.a. 382–582) were retrieved from the crystal structure of HSA at 2.5 Å (PDB code 1bm0)20. Two different models of hFcRn were used: the 2.7 Å resolution structure of hFcRn at pH 8.2 (PDB code 1exu) and the 2.6 Å resolution structure at pH 4.2 (PDB code 3m17)8,23. The β2m domain was included in the docking. The ZDOCK program was run with preferences for docking poses with the two histidines, His-161 and His-166, in hFcRn, and residues His-464, His-510 and His-535 in HSA were part of the protein–protein interface. All crystal structure figures were designed using PyMOL (DeLano Scientific).

Author contributions

J.T.A., B.D., J.C., A.P. M.B. and I.S. designed research; J.T.A, B.D., J.C., M.B.D., A.P., L.E., S.O.B. and K.S.G. performed research; J.T.A., B.D., J.C., M.B.D, A.P. and S.O.B. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; J.T.A., B.D., J.C., M.B., L.E., A.P., D.M., D.S. S.O.B. and I.S. analysed data; J.T.A, B.D. and I.S. wrote the paper.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Andersen J. T. et al. Structure-based mutagenesis reveals the albumin-binding site of the neonatal Fc receptor. Nat. Commun. 3:610 doi: 10.1038/nocmms1607 (2012).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S8 and Supplementary Tables S1-S4

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Sathiaruby Sivaganesh for excellent technical assistance. J.T.A. was supported by the Norwegian Research Council (Grant no. 179573/V40) and South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority (Grant no. 39375). K.S.G. was supported by the Norwegian Research Council (Grant no.179573). M.B. and B.D. were supported by the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority Technology Platform for Structural Biology and Bioinformatics (Grant no. 2009100 and 2011040).

Footnotes

I.S., J.T.A., B.D., J.C., A.P., L.E. and D.S. are co-inventors on pending patent applications, which are entitled 'Albumin Variants' and relate to the data described in this paper. The remaining authors have no competing financial interest to declare.

References

- Peters T. Jr. Serum albumin. Adv. Protein Chem. 37, 161–245 (1985). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury C. et al. The major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor for IgG (FcRn) binds albumin and prolongs its lifespan. J. Exp. Med. 197, 315–322 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson C. L. et al. Perspective–FcRn transports albumin: relevance to immunology and medicine. Trends Immunol. 27, 343–348 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roopenian D. C. & Akilesh S. FcRn: the neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 7, 715–725 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward E. S. & Ober R. J. Chapter 4: Multitasking by exploitation of intracellular transport functions the many faces of FcRn. Adv. Immunol. 103, 77–115 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister W. P., Huber A. H. & Bjorkman P. J. Crystal structure of the complex of rat neonatal Fc receptor with Fc. Nature 372, 379–383 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister W. P., Gastinel L. N., Simister N. E., Blum M. L. & Bjorkman P. J. Crystal structure at 2.2 A resolution of the MHC-related neonatal Fc receptor. Nature 372, 336–343 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West A. P. Jr. & Bjorkman P. J. Crystal structure and immunoglobulin G binding properties of the human major histocompatibility complex-related Fc receptor. Biochemistry 39, 9698–9708 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury C., Brooks C. L., Carter D. C., Robinson J. M. & Anderson C. L. Albumin binding to FcRn: distinct from the FcRn-IgG interaction. Biochemistry 45, 4983–4990 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ober R. J., Martinez C., Lai X., Zhou J. & Ward E. S. Exocytosis of IgG as mediated by the receptor, FcRn: an analysis at the single-molecule level. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 11076–11081 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ober R. J., Martinez C., Vaccaro C., Zhou J. & Ward E. S. Visualizing the site and dynamics of IgG salvage by the MHC class I-related receptor, FcRn. J. Immunol. 172, 2021–2029 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhat P. et al. Elucidation of intracellular recycling pathways leading to exocytosis of the Fc receptor, FcRn, by using multifocal plane microscopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 5889–5894 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roopenian D. C. et al. The MHC class I-like IgG receptor controls perinatal IgG transport, IgG homeostasis, and fate of IgG-Fc-coupled drugs. J. Immunol. 170, 3528–3533 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoyo H. P. et al. Conditional deletion of the MHC class I-related receptor FcRn reveals the sites of IgG homeostasis in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 2788–2793 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wani M. A. et al. Familial hypercatabolic hypoproteinemia caused by deficiency of the neonatal Fc receptor, FcRn, due to a mutant beta2-microglobulin gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 5084–5089 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minchiotti L., Galliano M., Kragh-Hansen U. & Peters T. Jr. Mutations and polymorphisms of the gene of the major human blood protein, serum albumin. Hum. Mutat. 29, 1007–1016 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen J. T., Daba M. B. & Sandlie I. FcRn binding properties of an abnormal truncated analbuminemic albumin variant. Clin. Biochem. 43, 367–372 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen J. T. & Sandlie I. A receptor-mediated mechanism to support clinical observation of altered albumin variants. Clin. Chem. 53, 2216 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peach R. J. & Brennan S. O. Structural characterization of a glycoprotein variant of human serum albumin: albumin Casebrook (494 Asp----Asn). Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1097, 49–54 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugio S., Kashima A., Mochizuki S., Noda M. & Kobayashi K. Crystal structure of human serum albumin at 2.5 A resolution. Protein Eng. 12, 439–446 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen J. T., Daba M. B., Berntzen G., Michaelsen T. E. & Sandlie I. Cross-species binding analyses of mouse and human neonatal Fc receptor show dramatic differences in immunoglobulin G and albumin binding. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 4826–4836 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen J. T., Dee Qian J. & Sandlie I. The conserved histidine 166 residue of the human neonatal Fc receptor heavy chain is critical for the pH-dependent binding to albumin. Eur. J. Immunol. 36, 3044–3051 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezo A. R., Sridhar V., Badger J., Sakorafas P. & Nienaber V. X-ray crystal structures of monomeric and dimeric peptide inhibitors in complex with the human neonatal Fc receptor, FcRn. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27694–27701 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield W. P., Marques J. A., Bhakta V. & Smith I. J. Modulation of clearance of recombinant serum albumin by either glycosylation or truncation. Thromb. Res. 99, 613–621 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenanova V. E. et al. Tuning the serum persistence of human serum albumin domain III:diabody fusion proteins. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 23, 789–798 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simard J. R. et al. Locating high-affinity fatty acid-binding sites on albumin by x-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 17958–17963 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry S., Mandelkow H., Brick P. & Franks N. Crystal structure of human serum albumin complexed with fatty acid reveals an asymmetric distribution of binding sites. Nat. Struct. Biol. 5, 827–835 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo T. T. et al. Neonatal Fc receptor: from immunity to therapeutics. J. Clin. Immunol. 30, 777–789 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen J. T. & Sandlie I. The versatile MHC class I-related FcRn protects IgG and albumin from degradation: implications for development of new diagnostics and therapeutics. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 24, 318–332 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werle M. & Bernkop-Schnurch A. Strategies to improve plasma half life time of peptide and protein drugs. Amino Acids 30, 351–367 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGregor D. P. Discovering and improving novel peptide therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 8, 616–619 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalevsky J. et al. Enhanced antibody half-life improves in vivo activity. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 157–159 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stehle G. et al. Plasma protein (albumin) catabolism by the tumor itself--implications for tumor metabolism and the genesis of cachexia. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 26, 77–100 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenanova V. et al. Tailoring the pharmacokinetics and positron emission tomography imaging properties of anti-carcinoembryonic antigen single-chain Fv-Fc antibody fragments. Cancer Res. 65, 622–631 (2005). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenanova V. et al. Radioiodinated versus radiometal-labeled anti-carcinoembryonic antigen single-chain Fv-Fc antibody fragments: optimal pharmacokinetics for therapy. Cancer Res. 67, 718–726 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen J. T. et al. Ligand binding and antigenic properties of a human neonatal Fc receptor with mutation of two unpaired cysteine residues. FEBS J. 275, 4097–4110 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock D. M. et al. Quantitative evaluation of Escherichia coli host strains for tolerance to cytosine methylation in plasmid and phage recombinants. Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 3469–3478 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleep D. et al. Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that overexpress heterologous proteins. Biotechnology (NY) 9, 183–187 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinery S. A. & Hinchliffe E. A novel class of vector for yeast transformation. Curr. Genet. 16, 21–25 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twine S. M. Characterisation of rHA Domain Fragments. PhD thesis, University of Southampton (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Finnis C. J. et al. High-level production of animal-free recombinant transferrin from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microb. Cell Fact. 9, 87 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne T. et al. Modulation of chaperone gene expression in mutagenized Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains developed for recombinant human albumin production results in increased production of multiple heterologous proteins. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 7759–7766 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans L. et al. The production, characterisation and enhanced pharmacokinetics of scFv-albumin fusions expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Protein Expr. Purif. 73, 113–124 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm G., Muhr R. & Jaenicke R. Quantitative analysis of protein far UV circular dichroism spectra by neural networks. Protein Eng. 5, 191–195 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Li L. & Weng Z. ZDOCK: an initial-stage protein-docking algorithm. Proteins 52, 80–87 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S8 and Supplementary Tables S1-S4