Abstract

Objective To describe variation in antibiotic prescribing for acute cough in contrasting European settings and the impact on recovery.

Design Cross sectional observational study with clinicians from 14 primary care research networks in 13 European countries who recorded symptoms on presentation and management. Patients followed up for 28 days with patient diaries.

Setting Primary care.

Participants Adults with a new or worsening cough or clinical presentation suggestive of lower respiratory tract infection.

Main outcome measures Prescribing of antibiotics by clinicians and total symptom severity scores over time.

Results 3402 patients were recruited (clinicians completed a case report form for 99% (3368) of participants and 80% (2714) returned a symptom diary). Mean symptom severity scores at presentation ranged from 19 (scale range 0 to 100) in networks based in Spain and Italy to 38 in the network based in Sweden. Antibiotic prescribing by networks ranged from 20% to nearly 90% (53% overall), with wide variation in classes of antibiotics prescribed. Amoxicillin was overall the most common antibiotic prescribed, but this ranged from 3% of antibiotics prescribed in the Norwegian network to 83% in the English network. While fluoroquinolones were not prescribed at all in three networks, they were prescribed for 18% in the Milan network. After adjustment for clinical presentation and demographics, considerable differences remained in antibiotic prescribing, ranging from Norway (odds ratio 0.18, 95% confidence interval 0.11 to 0.30) to Slovakia (11.2, 6.20 to 20.27) compared with the overall mean (proportion prescribed: 0.53). The rate of recovery was similar for patients who were and were not prescribed antibiotics (coefficient −0.01, P<0.01) once clinical presentation was taken into account.

Conclusions Variation in clinical presentation does not explain the considerable variation in antibiotic prescribing for acute cough in Europe. Variation in antibiotic prescribing is not associated with clinically important differences in recovery.

Trial registration Clinicaltrials.gov NCT00353951.

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance is a growing problem worldwide, with 10% of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates recorded as non-susceptible to penicillin in 30 countries in 2007.1 There is wide variation in antibiotic prescribing for ambulant patients in Europe.2 We do not know if this variation is explained by differences in presentation of illness or to which conditions it applies. Acute cough is one of the most common reasons for consulting. The proportion of European patients consulting in general practice with lower respiratory tract infection who are prescribed antibiotics ranges from about 27% in the Netherlands (for cough and bronchitis) to 75% in the United Kingdom.3 4 Trial evidence suggests that most antibiotic prescriptions do not help these patients to get better any quicker, although the datasets are sometimes small and the impact of case mix at presentation is unclear.5 6 7 Variation in antibiotic prescribing that does not improve outcomes for patients wastes resources, undermines self care for similar conditions in the future, puts patients at unnecessary risk of side effects, and increases selection of resistant organisms, and so represents an opportunity for improved care through greater standardisation. Higher levels of prescribing in certain settings, however, might be explained by differences in severity of illness and so variation might not always indicate inappropriate prescribing. We examined variation in antibiotic prescribing for acute cough in primary care in Europe and its impact on recovery, controlling for presentation.

Methods

Networks

The Genomics to combat Resistance against Antibiotics in Community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections in Europe (GRACE) (www.grace-lrti.org) Network of Excellence recruited 14 primary care research networks (based in Antwerp, Helsinki, Rotenburg, Utrecht, Balatonfured, Milan, Tromso, Lodz, Bratislava, Barcelona, Mataro, Jonkoping, Cardiff, Southampton) in 13 countries (Belgium, Finland, Germany, Holland, Hungary, Italy, Norway, Poland, Slovakia, Spain (two networks), Sweden, UK (Wales and England)).

Recruited networks had access to a minimum of 20 000 patients and had a track record of conducting research. A national network coordinator and a national network facilitator took responsibility for their network’s set up, recruitment, and data management.

Study materials and procedures

Study materials (protocol, patient diary, and case report form) and study procedures were developed with advice from all networks. The coordinators and facilitators undertook face to face training in study procedures, including entering data on to the GRACE online system (GOS), and cascaded training to all participating general practitioners.

Study documents required by ethics review committees and participants (general practitioners and patients) were translated into local languages. Back translation by independent translators ensured accuracy.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible patients were aged 18 and over who were consulting with an illness where an acute or worsened cough was the main or dominant symptom or had a clinical presentation that suggested a lower respiratory tract infection with a duration of up to and including 28 days, were consulting for the first time within this illness episode, were seen within normal consulting hours, had not previously participated in the study, were able to fill out study materials, had provided written informed consent, and were considered immunocompetent. These broad inclusion criteria captured a wide range of patients with community acquired lower respiratory tract infection. Although almost all patients with this infection have a cough, the additional eligibility criterion of clinical presentation suggestive of lower respiratory tract infection was added to make those with infection but no cough also eligible.

Recruitment of patients

Participating general practitioners were asked to recruit consecutive eligible patients in October and November 2006 and from late January to March 2007. The scheduled two month gap enabled us to explore the effect of possible temporal variations in causes of cough during the winter.

Data collection

Clinicians (general practitioners and nurse practitioners) recorded aspects of patients’ history, symptoms, comorbidities (diabetes, chronic lung disease, and cardiovascular disease), clinical findings, and management, including antibiotic prescription and other treatments and investigations, on a case report form. They indicated the presence or absence of 14 symptoms (cough, phlegm production, shortness of breath, wheeze, coryza, fever during this illness, chest pain, muscle aching, headache, disturbed sleep, feeling generally unwell, interference with normal activities, confusion/disorientation, and diarrhoea) and then rated whether each of the symptoms constituted “no problem,” “mild problem,” “moderate problem,” or a “severe problem” for the patient. The colour of any sputum produced was recorded as clear, white, yellow, green, or bloodstained.

Clinicians recorded the patient’s body temperature with a disposable thermometer (TempaDot, 3M Health Care) provided in each individual patient study pack.

Patient reported follow-up

Patients were given a symptom diary. They were asked to rate 13 symptoms each day until recovery (or for 28 days if symptoms were ongoing) on a seven point scale from “normal/not affected” to “as bad as it can be.” Patients rated the same symptoms as the clinicians apart from confusion/disorientation and diarrhoea. In addition they were asked to rate the impact of their illness on their social activities. There were questions about smoking and course of the illness, including subsequent management and contacts with the health service over the next 28 days.

Data management

All data from case report forms and patients’ diaries were entered via a remote secure data entry portal onto the GRACE online system that was compliant with regulatory guidelines. Central and internal monitoring and checking ensured the accuracy of data collection and entry. Patients were telephoned four to seven days after inclusion to provide them with the opportunity to ask questions and discuss any problems with diary completion.

Sample size

Sample size estimation was based on an estimate of a probability of 50% for certain events such as treatment decisions (50% is the most conservative estimate of probabilities in statistical terms; more common or more rare events would give more power). This required a total sample size of 270 per network to give 95% confidence intervals of 44 to 56 around detecting that 50% probability within each network. Though we had no information on the likely level of clustering of antibiotic prescribing within different networks, we considered that this conservative approach to estimation would give enough power for analyses between networks while accounting for clustering.

Symptom scores

The categories for clinicians to rate the severity of each symptom as “no problem,” “mild problem,” “moderate problem,” or “severe problem” were scored 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Scores were calculated for patients with a minimum of 85% (that is, 12 out of 14 symptoms) of their symptoms recorded. This score was scaled to range between 0 and 100 so that it could be interpreted as a percentage of maximum symptom severity.

We calculated patients’ self reported daily symptom severity scores from the diary data, with scores for 13 symptoms summed and scaled to range between 0 and 100 so that the symptom severity score for a given individual on a given day could be interpreted as a percentage of maximum possible symptom severity. This daily symptom severity score was used as the outcome variable in patient outcome model.

Analysis

Descriptives—Descriptive statistics by network and overall were calculated by using means and standard deviations (SD), medians (interquartile ranges), and proportions as appropriate. Presented SDs were inflated for clustering.8

Antibiotic prescribing—Differences in clinical presentation were controlled for by using 13 of the 14 symptoms recorded by clinicians (cough was excluded as it was present in 99.8% of cases), sputum type, temperature, age, and comorbidities. Antibiotic prescribing by networks was investigated by using a two level hierarchical logistic model9 fitted to the data from the case report forms with patients nested within clinicians. The dependent variable was whether the clinician prescribed antibiotics or not, with patients who were given a prescription and advised to delay taking the antibiotics counted as receiving a prescription. Network was included as a fixed effect, with all networks being compared with the overall mean. The impact of smoking status and duration of illness before consulting was explored in the subset of patients with complete data (diary responders).

Patients’ recovery—A three level hierarchical ARMA (1,1) model10 was fitted to the logged daily symptom scores reported by patients (box). We controlled for differences in clinical presentation using the same variables as in the previous model, along with smoking status and duration of illness before consulting. We included the impact of differences in antibiotic management as both a main effect and an interaction with time (to allow for different recovery rates over time for those with and without antibiotics).

ARMA model used to assess variation in outcome in relation to antibiotic prescribing

An ARMA (1,1) model comprises an autoregressive part and a moving average part and expresses each observation as a combination of the two:

Xt=εt+Xt−1+εt−1

where Xt is the symptom severity score at time t, εt is the error term. This allows for each individual’s symptom severity scores and the related error term to be correlated with the previous day.

Statistical analysis software—Descriptive analyses were performed with SPSS version 14.0 (Chicago, ILL). All modelling was performed in the R programming language and environment11 using the lme412 and nlme13 packages.

Results

Patients

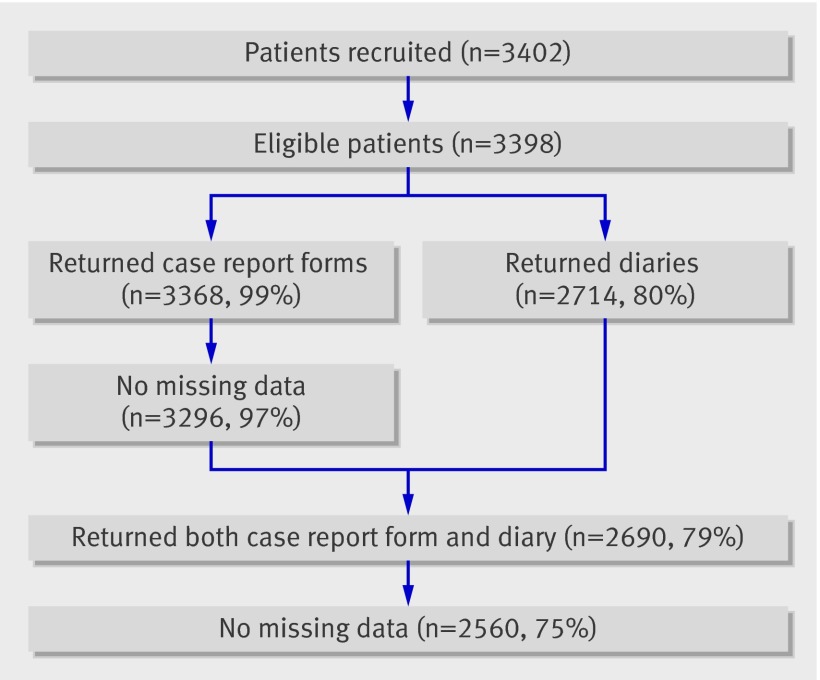

A total of 3402 patients were recruited by 387 practitioners. Six networks included 270 patients or more, and all included over 100 (table 1). Four patients were later found to be ineligible and were excluded from further analysis. Case report forms were completed for 3368 (99%) and diary data were obtained from 2714 (80%) patients. Exclusion of patients with missing data reduced the case report form dataset to 3296 (97%) and the diary dataset to 2560 (75%) (fig 1). Those who filled in the diary tended to be older than those who did not (median age 45 (interquartile range 33-58) v 36 (27-48)). There were no significant differences in the proportions by sex. There was some variation in the response rates from each network, with patients from Eastern European networks being most likely to return the symptom diary. Those who did not fill in a diary were no more or less likely to have been prescribed antibiotics than the others.

Table 1.

Countries, networks, general practitioners, practices, and included patients

| Site | Patients/practices/clinicians | Men* | Age (years)† | Symptom severity†‡ | Oral temperature*§ | Comorbidity*¶ | Antibiotic treatment | Duration of course (days)† | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Normal | High | R | H | D | ||||||||

| Belgium | |||||||||||||

| Antwerp | 216/18/26 | 46.80 (101) | 47 (36-60) | 31 (21-40) | 19.70 (42) | 62.90 (134) | 17.40 (37) | 23.60 (51) | 8.30 (18) | 3.70 (8) | 25.90% (56) | 8 (7-8) | |

| Finland | |||||||||||||

| Helsinki | 103/2/26 | 24.30 (25) | 45 (34-56) | 31 (24-43) | 17.50 (18) | 76.70 (79) | 5.80 (6) | 13.60 (14) | 2.90 (3) | 2.90 (3) | 41.70% (43) | 9 (7-10) | |

| Germany | |||||||||||||

| Rotenberg | 229/16/16 | 31.00 (71) | 40 (29-52) | 33 (24-43) | 28.50 (65) | 65.40 (149) | 16.10 (14) | 15.30 (35) | 7.90 (18) | 4.40 (10) | 34.50% (79) | 7 (6-7) | |

| Holland | |||||||||||||

| Utrecht | 200/11/34 | 44 (88) | 57 (42-67) | 33 (24-43) | 28.50 (57) | 68.50 (137) | 3.00 (6) | 27.00 (54) | 15 (30) | 7.50 (15) | 41.50% (83) | 7 (7-7) | |

| Hungary | |||||||||||||

| Balatonfured | 323/11/11 | 39.90 (129) | 42 (29-53) | 26 (17-36) | 11.50 (37) | 51.10 (165) | 37.50 (121) | 9.30 (30) | 9.00 (29) | 4.00 (13) | 74.60% (241) | 5 (5-7) | |

| Italy | |||||||||||||

| Milan | 207/13/12 | 33.30 (69) | 43 (36-58) | 19 (12-29) | 13.50 (28) | 79.20 (164) | 7.20 (15) | 12.60 (26) | 7.20 (15) | 2.90 (6) | 74.90% (155) | 7 (5-7) | |

| Norway | |||||||||||||

| Tromso | 203/11/41 | 36.50 (74) | 50 (37-57) | 36 (26-43) | 21.40 (42) | 70.90 (139) | 7.70 (15) | 22.70 (46) | 7.40 (15) | 5.40 (11) | 30% (203) | 10 (7-10) | |

| Poland | |||||||||||||

| Lodz | 301/9/21 | 30.60 (92) | 40 (28-55) | 36 (26-45) | 33.20 (100) | 52.50 (158) | 14.30 (43) | 13.30 (40) | 19.90 (60) | 2.70 (8) | 71.40% (215) | 7 (5-7) | |

| Slovakia | |||||||||||||

| Bratislava | 299/5/23 | 33.10 (99) | 41 (30-52) | 26 (19-36) | 2.70 (8) | 71.80 (209) | 25.40 (74) | 13.00 (39) | 17.10 (51) | 3.30 (10) | 87.60% (262) | 7 (7-7) | |

| Spain | |||||||||||||

| Barcelona | 277/3/25 | 33.60 (93) | 43 (29-59) | 19 (14-29) | 20.70 (57) | 72.40 (199) | 6.90 (19) | 9.40 (26) | 3.60 (10) | 3.60 (10) | 20.60% (57) | 8 (6-8) | |

| Mataro | 196/3/21 | 39.80 (78) | 46 (33-64) | 19 (13-29) | 24.50 (48) | 70.90 (139) | 4.60 (9) | 16.80 (33) | 10.20 (20) | 5.60 (11) | 34.20% (67) | 8 (5-8) | |

| Sweden | |||||||||||||

| Jonkoping | 300/12/81 | 36.70 (110) | 47.5 (37-61) | 38 (29-49) | 18.90 (56) | 70.70 (210) | 10.40 (31) | 16.00 (48) | 5.30 (16) | 3.30 (10) | 38% (114) | 9 (9-10) | |

| UK | |||||||||||||

| Cardiff | 300/5/26 | 38.30 (115) | 45 (34-59) | 36 (24-45) | 21.30 (64) | 74.30 (223) | 4.30 (13) | 26 (78) | 8.00 (24) | 5.00 (15) | 69.70% (209) | 7 (5-7) | |

| Southampton | 214/6/23 | 39.30 (84) | 49 (36-59.75) | 36 (26-43) | 10.90 (23) | 82.50 (174) | 6.60 (14) | 20.60 (44) | 9.30 (20) | 3.70 (8) | 62.60% (214) | 7 (7-7) | |

| Total | 3368/125/387 | 36.50 (1228/3368) | 45 (33-58) | 31 (19-40) | 19.30 (645) | 68.20 (2279) | 12.50 (417) | 15.30 (515) | 7.90 (266) | 4.10 (138) | 52.70% (1776) | 7 (6-7) | |

*Percentage (number).

†Median (interquartile range).

‡Score scaled to range between 0 and 100.

§Low (<36°c), normal (≥36°c and ≤37.2°c), high (>37.2°c).

¶R=respiratory illness (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, other lung disease); H=heart disease (heart failure, ischaemic heart disease, other heart disease); D=diabetes.

Fig 1 Patient flow chart

The median age of patients was 45.0 (interquartile range 35-58), 37% (1228) were men, 98% (3309) were seen at the office or surgery, 15% (515) had an existing respiratory condition, 8% (266) had a cardiovascular related illness, and 4% (138) had diabetes (table 1). The three most common presenting symptoms, other than cough (99.7%, 3358), were being generally unwell (80%, 2698), phlegm production (77%, 2592), and interference with normal activities (69%, 2335). The median number of symptoms recorded by a clinician was eight (6-9). Patients were unwell before the consultation for a median of five days (3-8). The average temperature was 36.8ºC (SD 1.59).

Antibiotic prescribing

Antibiotics were prescribed for 53% (1776) of included patients for a median of seven days (6-7) (table 1). There were notable differences between networks in the unadjusted proportion of patients who were prescribed antibiotics. Clinicians from networks based in Bratislava, Milan, Balatonfured, Lodz, and Cardiff were more likely to prescribe antibiotics than the overall average.

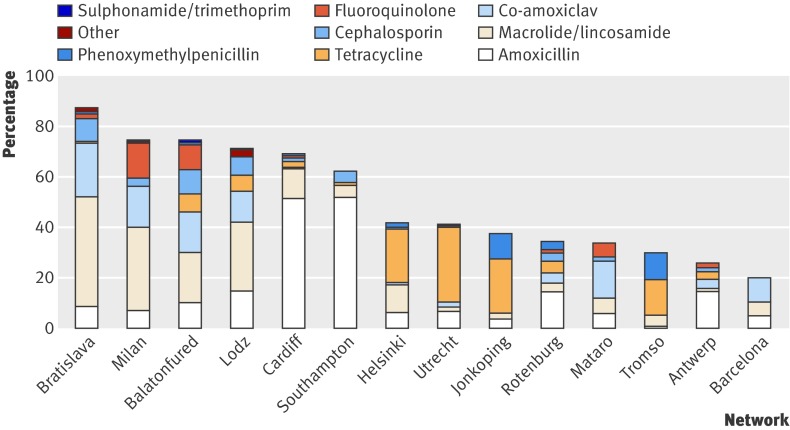

Amoxicillin accounted for 29% of prescriptions, ranging from 3% in Tromso to 83% in the Southampton network (fig 2). Macrolides/lincosamides were prescribed for 26% of patients, ranging from 4% in Utrecht to 50%, 45%, and 38% in the Bratislava, Milan, and Lodz networks, respectively. Co-amoxiclav was prescribed for 15%, though this varied widely, from 0% in Jonkoping and Tromso to 47% in Barcelona (it was the most commonly prescribed antibiotic in both Barcelona and Mataro (43%)). Tetracyclines were prescribed for 14%. Three networks did not prescribe tetracyclines at all (Barcelona, Mataro, and Milan), and they were the first choice in three networks (Utrecht 72%, Jonkoping 56%, and Helsinki 51%). Cephalosporins were prescribed for 7% (ranging from 0% to 13%) and fluoroquinolones for 5%. Fluoroquinolones were most commonly prescribed in the Milan, Mataro, and Balatonfured networks (18%, 16%, and 13%, respectively) and were not prescribed at all in six networks (Southampton, Barcelona, Lodz, Jonkoping, Tromso, and Helsinki).

Fig 2 Choice of antibiotic by network

Antibiotic prescribing by networks adjusted for clinical presentation

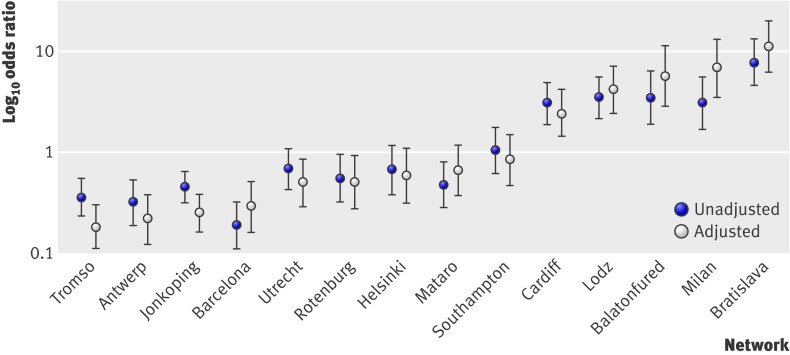

Significant variation between networks remained after adjustment for clinical presentation, with antibiotic prescribing in 11 networks significantly different from the overall mean at the 5% level (table 2). Figure 3 shows the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for antibiotic prescribing for all networks.

Table 2.

Two level logistic regression model* of odds of being prescribed antibiotic in each network (3296 patients from 384 clinicians). Figures are odds ratios (95% confidence intervals)

| Network | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Antwerp | 0.22 (0.12 to 0.38) | <0.001 |

| Balatonfured | 5.69 (2.88 to 11.26) | <0.001 |

| Barcelona | 0.29 (0.16 to 0.51) | <0.001 |

| Bratislava | 11.2 (6.20 to 20.27) | <0.001 |

| Cardiff | 2.44 (1.42 to 4.19) | <0.01 |

| Helsinki | 0.58 (0.31 to 1.09) | 0.09 |

| Jonkoping | 0.25 (0.16 to 0.38) | <0.001 |

| Lodz | 4.14 (2.4 to 7.16) | <0.001 |

| Mataro | 0.66 (0.37 to 1.18) | 0.16 |

| Milan | 6.81 (3.49 to 13.27) | <0.001 |

| Rotenberg | 0.5 (0.27 to 0.92) | 0.03 |

| Southampton | 0.84 (0.47 to 1.5) | 0.55 |

| Tromso | 0.18 (0.11 to 0.30) | <0.001 |

| Utrecht | 0.5 (0.29 to 0.85) | 0.01 |

*Model controls for clinician rated symptom scores and clinical presentation. Clinician level variance component was 23.3%, using π2/3 estimator.

Fig 3 Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for antibiotic prescribing by network (both adjusted for clustering within clinician). All networks are compared with overall mean

There were no significant differences between the two recruitment periods in overall rate of antibiotic prescribing. The model was also fitted to the subsample of patients with usable diary data to check the effect of duration of illness before consultation and smoking status on prescribing. Both variables were significantly associated with receiving a prescription for antibiotics, with a 2% increase in the odds of receiving an antibiotic for each additional day of illness before consulting (odds ratio 1.02, 95% confidence interval 1.01 to 1.04) and a 38% increase in the odds for smokers (1.38, 1.09 to 1.76). Adjustment for these factors, however, had no effect on the magnitude or significance of the variation between networks and therefore we have presented the model with the larger sample.

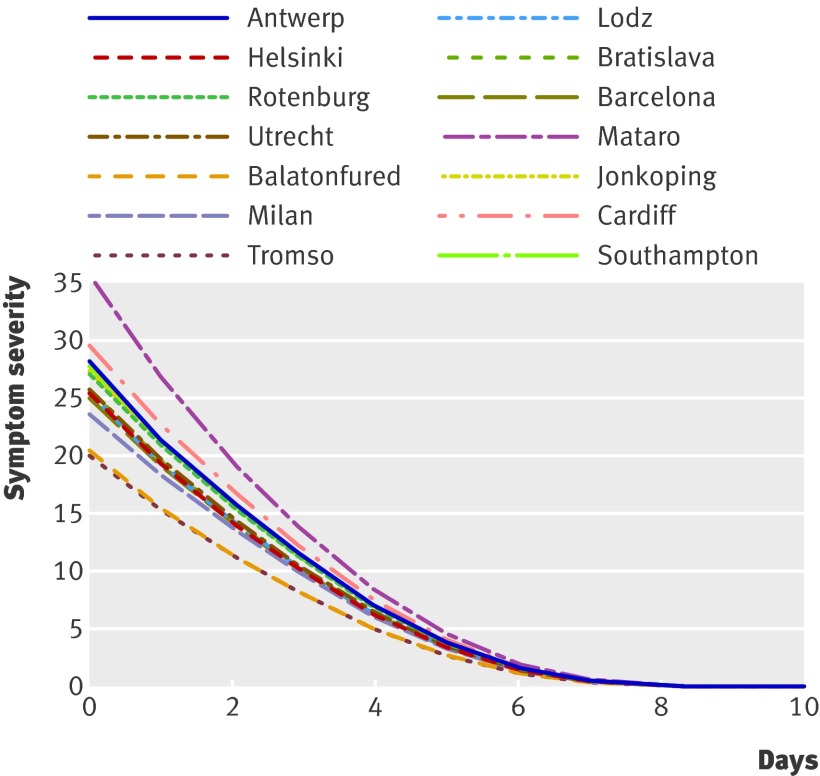

Patients’ recovery

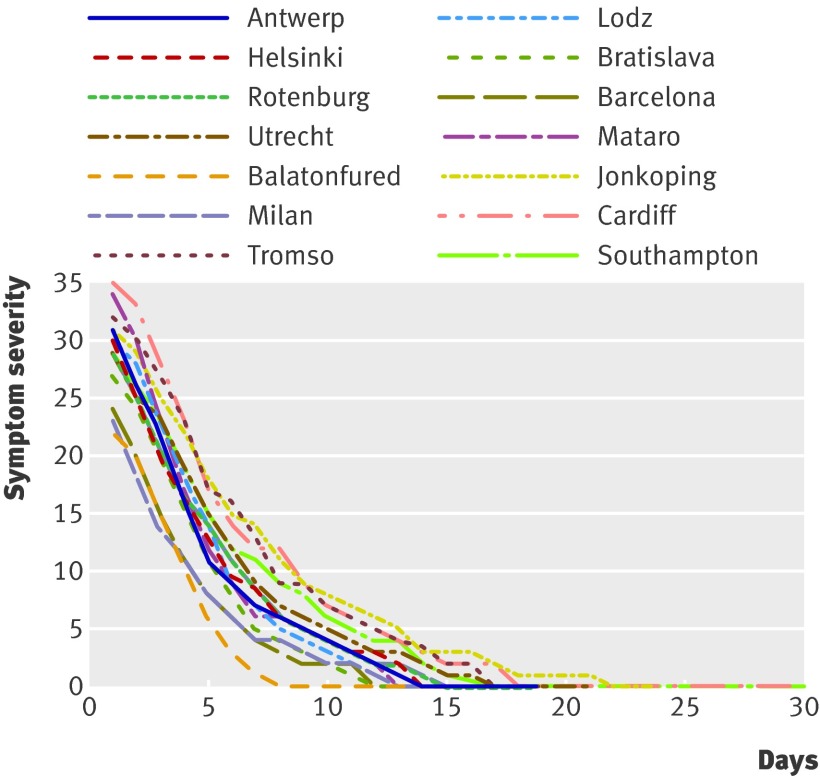

There was considerable variation between networks in the rate of recovery after presentation, as shown by the median symptom trajectory plots (fig 4). The median time to patients reporting feeling recovered (single item) was 11 days. The median time for patients’ symptom severity scores to drop to 0 was 15 days. Respiratory comorbidity was associated with initial higher symptom severity scores. Those who waited longer before presenting had higher initial symptom severity scores.

Fig 4 Unadjusted median symptom severity scores over time by network

Significant variation in outcome remained across networks after adjustment for clinical presentation, with two of the networks (Balatonfured and Mataro) reporting differences in patients’ reported symptom severity at baseline compared with the overall mean, three networks (Cardiff, Milan, and Jonkoping) reporting significantly slower recovery rates, and three networks (Mataro, Balatonfured, Antwerp) reporting significantly faster recovery. While there were significant differences in the symptom trajectories across the networks, differences were not large. Almost all the symptom trajectories converged after a week (fig 5). Being prescribed antibiotics was associated with a faster reduction in symptom severity scores, as indicated by the significant interaction between prescribing antibiotics and day. This association, however, was small (table 3).

Fig 5 Predicted recovery curves by network for those prescribed antibiotics from ARMA model

Table 3.

Estimates for ARMA (1,1) model*: symptom severity scores over time (65 541 observations in 2560 patients from 364 clinicians)

| Parameter estimate, P value | Interactions with time, P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Management | ||

| Prescribed antibiotics | 0.05, 0.26 | −0.01, <0.01 |

| Network | ||

| Antwerp | 0.05, 0.52 | -0.01, 0.03 |

| Balatonfured | -0.27, <0.001 | -0.01, 0.02 |

| Barcelona | -0.07, 0.32 | 0.00, 0.84 |

| Bratislava | -0.04, 0.50 | -0.00, 0.29 |

| Cardiff | 0.09, 0.17 | 0.01, 0.02 |

| Helsinki | 0.03, 0.72 | 0.00, 0.62 |

| Jonkoping | 0.02, 0.78 | 0.01, <0.001 |

| Lodz | -0.05, 0.38 | -0.01, 0.07 |

| Mataro | 0.28, <0.001 | -0.02, <0.001 |

| Milan | -0.13, 0.08 | 0.01, <0.01 |

| Rotenberg | 0.02, 0.77 | 0.00, 0.98 |

| Southampton | 0.01, 0.90 | 0.01, 0.08 |

| Tromso | 0.11, 0.14 | 0.00, 0.42 |

| Utrecht | -0.05, 0.52 | 0.00, 0.88 |

*Model controls for clinician recorded symptom scores and clinical presentation as well as allowing recovery trajectory to follow cubic polynomial.

The impact of antibiotic prescribing, while statistically significant, represents a tenth of a single percentage difference in symptom severity score (not presented), and therefore it is reasonable to consider it clinically unimportant. Such a small effect is entirely consistent with a placebo effect.

Hospital admission

Overall, 1.1% (28) of patients were admitted to hospital after inclusion. For individual networks this ranged from none to 4.3% (9).

Discussion

Main findings

In this large prospective international comparative study of the management of acute cough among adults in primary care we found considerable variation in the 13 countries studied. Major differences in the decision whether or not to prescribe an antibiotic in these settings remained, even after we adjusted for clinical presentation (symptoms, duration of illness, smoking, age, comorbidity, and temperature). Patients included by networks based in Bratislava, Milan, Balatonfured, Lodz, and Cardiff were at least twice as likely to be prescribed antibiotics than the overall mean. Patients included by networks based in Tromso, Antwerp, and Jonkoping were at least four times less likely to be prescribed antibiotics than the overall mean.

We also identified marked differences between networks in choice of antibiotic. For example, while amoxicillin was overall the most common antibiotic prescribed, this ranged from 3% in the Tromso network to 83% in Southampton. While fluoroquinolones were prescribed for 5% overall, they were prescribed for 18% of patients included in the Milan network. These differences might be attributable to different guidelines and habits in different countries. This will be further explored in a parallel qualitative study.

There were two main findings regarding patients’ recovery. Firstly, there were significant differences between networks in both severity of symptoms on day one (intercept) and the recovery rate (slope). Differences in the recovery rate, however, were small (fig 5), and patients recovered at a similar rate regardless of network. Secondly, whether a patient was prescribed antibiotics or not was statistically associated with outcome. The magnitude of this association amounted to a difference of a tenth of a single per cent in the symptom severity score after seven days, which is not clinically relevant.

Strengths and limitations

We prospectively described antibiotic prescribing for a well defined population of patients in a large number of countries recruited at the same time. Recruitment was for two periods over a single winter, and findings by recruitment period were similar, suggesting local or temporal variations in cause were unlikely to have explained the observed differences.

The clinicians who participated (and therefore their patients) were all affiliated to a research network and so might not have been representative. In general, research minded clinicians might be more likely to practice according to guidelines.14 They would have been aware of our interest in exploring international differences in antibiotic prescribing, which might have led to an underestimation of the differences we found.

Bias

As the study spanned 13 European countries, there is no guarantee that perceptions of health and reporting of symptoms were consistent. We do not know how cultural differences influenced our results. We are exploring these issues in a parallel qualitative study with patients and clinicians in nine of the networks. Response bias was not relevant to data from the case report forms as there was a 99% completion rate. Completion rates for patients’ diaries ranged from 60% in the Cardiff network to almost 100% in the Bratislava network. The overall response rate to the diary was high (80%). Non-responders might have deteriorated more than responders, but given similar rates of antibiotic prescribing between the two groups and the generally benign natural clinical course of this condition this is unlikely. Ascertainment bias was minimised by a data collection protocol used by all networks. While every network followed this protocol, some networks implemented additional strategies to improve diary return rates. The impact of different intensities of contact with patients during follow-up is uncertain.

Sample size

This international study was adequately powered to explore antibiotic prescribing. Only a small number of patients were admitted to hospital, and there were no deaths. While this reflects the natural course of acute cough and the fact that it is managed almost exclusively in primary care, the low number of such complications made Europe-wide comparisons on admission to hospital impossible. For the analysis of recovery, the combination of the large number of data points per patient with the large number of patients made this analysis overpowered with some significant findings having little or no clinical relevance.

Comparison with previous studies

A study of antibiotic treatment for lower respiratory tract infection in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK over 10 years ago asked general practitioners to retrospectively describe their management of cases. Overall, community acquired pneumonia accounted for 18% of cases, making this a highly unusual sample. Retrospective data collection carries particular risks of selection bias and incomplete ascertainment of comparable clinical data. Overall, 83% were prescribed antibiotics.15

In a two country comparison, general practitioners in Spain and Denmark recorded their management of respiratory tract infections. Spanish general practitioners prescribed more antibiotics for patients with a presumed tonsillar and bronchi/lung infection focus. There was no adjustment for severity and duration of illness or smoking.16

Implications for practice and research

Some interventions have been shown to successfully reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in general practice,17 18 19 20 21 and prescribing fewer antibiotics at the general practice level is associated with local reductions in antibiotic resistance.22

We identified marked differences in whether and what antibiotics are prescribed for acute cough throughout Europe that remained after adjustment for clinical presentation based on the clinician’s assessment of symptoms, duration of illness, smoking, patient’s history (the presence of any comorbidities), age, and temperature.

We also found that large differences in antibiotic prescribing did not translate to clinically important differences in patients’ recovery. Therefore management of acute cough is an issue that is appropriate for standardised international care pathways promoting conservative antibiotic prescribing.

What is already known on this topic

Acute cough is a major reason for antibiotic prescribing in primary care, with many prescriptions resulting in no clinical benefit

There is considerable variation in antibiotic prescribing to ambulatory patients across Europe

There are inadequate patient level data to determine whether this variation is justified by variation in clinical presentation.

What this study adds

Considerable variation in antibiotic prescribing for acute cough remains throughout Europe even after adjustment for illness severity, comorbidity, temperature, age, duration of illness before to consultation, and smoking status

Recovery is not meaningfully influenced by variation in antibiotic prescribing

We acknowledge the entire GRACE team for their diligence, expertise, and enthusiasm. The GRACE team are: Zseraldina Arvai, Zuzana Bielicka, Francesco Blasi, Alicia Borras, Curt Brugman, Jo Coast, Mel Davies, Kristien Dirven, Peter Edwards, Iris Hering, Judit Holczerné, Helena Hupkova, Kristin Alise Jakobsen, Bernadette Kovaks, Chrisina Lannering, Frank Leus, Katherine Loens, Michael Moore, Magdalena Muras, Carol Pascoe, Tom Schaberg, Matteu Serra, Richard Smith, Jackie Swain, Paolo Tarsia, Kirsi Valve, Robert Veen, and Tricia Worby. We thank all the clinicians and patients who consented to be part of GRACE, without whom this study would not have been possible.

Contributors: All authors contributed to either the conception and design or the analysis and interpretation of the data; contributed to drafting and revising the manuscript; and approved the final version of the manuscript. CCB is guarantor.

Funding: This study was funded by 6th Framework Programme of the European Commission (LSHM-CT-2005-518226). The South East Wales Trials Unit is funded by the Wales Office for Research and Development. All authors declare that they are independent of the funders.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Ethic review committees in each country approved the study.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b2242

References

- 1.Grundmann H. EARSS annual report 2007. Bilthoven, Netherlands: European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System, 2007:40.

- 2.Goossens H, Ferech M, Vander Stichele R, Elseviers M. Outpatient antibiotic use in Europe and association with resistance: a cross-national database study. Lancet 2005;365:579-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macfarlane J, Lewis SA, Macfarlane R, Holmes W. Contemporary use of antibiotics in 1089 adults presenting with acute lower respiratory tract illness in general practice in the UK: implications for developing management guidelines. Respir Med 1997;91:427-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akkerman AE, Kuyvenhoven MM, van der Wouden JC, Verheij TJM. Prescribing antibiotics for respiratory tract infections by GPs: management and prescriber characteristics. Br J Gen Pract 2005;55:114-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smucny J, Fahey T, Becker L, Glazier R, McIsaac W. Antibiotics for acute bronchitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(4):CD000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Macfarlane J, Holmes W, Gard P, Macfarlane R, Rose D, Weston V, et al. Prospective study of the incidence, aetiology and outcome of adult lower respiratory tract illness in the community. Thorax 2001;56:109-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Little P, Rumsby K, Kelly J, Watson L, Moore M, Warner G, et al. Information leaflet and antibiotic prescribing strategies for acute lower respiratory tract infection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005;293:3029-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donner A, Klar N. Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. London: Arnold, 2000.

- 9.Goldstein H. Multilevel statistical models. London: Hodder Arnold, 2003.

- 10.Box GEP, Jenkins GM. Time series analysis: forecasting and control. Rev ed. San Francisco: Holden-Day, 1976.

- 11.R Development Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2007.

- 12.Bates D. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes. 2007; R package version 0.99875-8.

- 13.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, The R Core team. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. 2007; R package version 3.1-83.

- 14.Akkerman AE, Kuyvenhoven MM, Verheij TJM, van Dijk L. Antibiotics in Dutch general practice: nationwide electronic GP database and national reimbursement rates. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2008;17:378-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huchon GJ, Gialdroni-Grassi G, Leophonte P, Manresa F, Schaberg T, Woodhead M. Initial antibiotic therapy for lower respiratory tract infection in the community: a European survey. Eur Respir J 1996;9:1590-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bjerrum L, Boada A, Cots J, Llor C, Fores Garcia D, et al. Respiratory tract infections in general practice: considerable differences in prescribing habits between general practitioners in Denmark and Spain. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2004;60:23-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altiner A, Brockmann S, Sielk M, Wilm S, Wegscheider K, Abholz H-H. Reducing antibiotic prescriptions for acute cough by motivating GPs to change their attitudes to communication and empowering patients: a cluster-randomized intervention study. J Antimicrob Chemother 2007;60:638-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnold SR, Straus SE. Interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing practices in ambulatory care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;(4):CD003539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coenen S, Van Royen P, Michiels B, Denekens J. Optimizing antibiotic prescribing for acute cough in general practice: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. J Antimicrob Chemother 2004;54:661-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Welschen I, Kuyvenhoven MM, Hoes AW, Verheij TJ. Effectiveness of a multiple intervention to reduce antibiotic prescribing for respiratory tract symptoms in primary care: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2004;329:431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cals JWL, Butler CB, Hopstaken RM, Hood K, Dinant G. Effect of point of care testing for C reactive protein and training in communication skills on antibiotic use in lower respiratory tract infections: cluster randomised trial. BMJ 2009;338;b1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Butler CC, Dunstan F, Heginbothom M, Mason B, Roberts Z, Hillier S, et al. Containing antibiotic resistance: decreased antibiotic-resistant coliform urinary tract infections with reduction in antibiotic prescribing by general practices. Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:785-92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]