Abstract

Objectives To assess whether the mortality benefit from screening men aged 65-74 for abdominal aortic aneurysm decreases over time, and to estimate the long term cost effectiveness of screening.

Design Randomised trial with 10 years of follow-up.

Setting Four centres in the UK. Screening and surveillance was delivered mainly in primary care settings, with follow-up and surgery offered in hospitals.

Participants Population based sample of 67 770 men aged 65-74.

Interventions Participants were individually allocated to invitation to ultrasound screening (invited group) or to a control group not offered screening. Patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm detected at screening underwent surveillance and were offered surgery if they met predefined criteria.

Main outcome measures Mortality and costs related to abdominal aortic aneurysm, and cost per life year gained.

Results Over 10 years 155 deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm (absolute risk 0.46%) occurred in the invited group and 296 (0.87%) in the control group (relative risk reduction 48%, 95% confidence interval 37% to 57%). The degree of benefit seen in earlier years of follow-up was maintained in later years. Based on the 10 year trial data, the incremental cost per man invited to screening was £100 (95% confidence interval £82 to £118), leading to an incremental cost effectiveness ratio of £7600 (£5100 to £13 000) per life year gained. However, the incidence of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms in those originally screened as normal increased noticeably after eight years.

Conclusions The mortality benefit of screening men aged 65-74 for abdominal aortic aneurysm is maintained up to 10 years and cost effectiveness becomes more favourable over time. To maximise the benefit from a screening programme, emphasis should be placed on achieving a high initial rate of attendance and good adherence to clinical follow-up, preventing delays in undertaking surgery, and maintaining a low operative mortality after elective surgery. On the basis of current evidence, rescreening of those originally screened as normal is not justified.

Trial registration Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN37381646.

Introduction

National screening programmes for abdominal aortic aneurysm in men have recently been introduced in England and Scotland1 2 and in the United States as part of Medicare.3 The United Kingdom Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS)4 5 has provided most of the worldwide randomised evidence for the mortality benefit after ultrasound screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm.6 7 The UK screening programme for men aged 65 is based closely on the protocol and procedures in MASS. Some uncertainties relating to screening remain, however, including its long term benefit in terms of mortality and cost effectiveness, whether rescreening those with a previously normal scan is warranted, and the extent to which incidental detection of abdominal aortic aneurysm erodes the benefit of a systematic screening policy over time. It might be expected that the mortality benefit seen in the early years after one-off screening would decrease over time. MASS, started in 1997, runs more than 10 years ahead of the UK national screening programme and is uniquely positioned to tackle these uncertainties and to inform the development of the national programme.

Results from MASS were last published after seven years of follow-up.5 The only existing evidence from randomised trials after seven years comes from the much smaller Chichester trial,8 in which a possibly substantial increase in ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms among participants screened as normal was noted during later follow-up.9 Such an increase would reduce the long term benefit from a single initial scan. Moreover, long term cost effectiveness has been estimated only through health economic modelling,10 11 and such models extrapolated from short term data may be misleading.12 13 To provide more reliable evidence, we present new information from the 10 years of follow-up now available in MASS.

Methods

The design of MASS is described in detail elsewhere.4 Briefly, a population based sample of 67 770 men aged 65-74 was recruited during 1997-9 from four centres in the UK and randomised to receive an invitation to screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm (invited group) or not (control group). Among the 33 883 men invited to screening, principally in a primary care setting, 27 204 (80%) attended and 1334 aneurysms (diameter ≥3.0 cm) were detected. Within this group of detected aneurysms, surveillance involved rescanning: annually for those with diameters of 3.0-4.4 cm and every three months for those of 4.5-5.4 cm. Patients were referred to a hospital outpatient clinic for possible elective surgery when the aneurysm reached 5.5 cm, the aneurysm had expanded by 1.0 cm or more in one year, or symptoms attributable to the aneurysm were reported.

We collected additional data from local hospital records on follow-up ultrasound scanning done within medical imaging departments and surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm. The UK Office for National Statistics notified us of deaths up to 31 March 2008, after matching on the unique National Health Service (NHS) number for each participant. Follow-up ranged from 8.9 to 11.2 years (mean 10.1 years). The primary outcome of interest—deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm—is defined as all deaths within 30 days of any surgery (elective or emergency) for abdominal aortic aneurysm plus all deaths with codes 441.3-441.6 (international classification of diseases, ninth revision; see table 1).

We used unadjusted Cox regression to compare deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm (censoring other causes of death) and all cause mortality between the two randomised groups. Life years gained was derived as the area between the Kaplan-Meier curves of deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm for the control and invited groups, adjusting for the effect of deaths from other causes.14 We also obtained an unbiased randomisation based estimate of the benefit of attending initial screening.15 This estimate was calculated by subtracting from the controls a group that is equivalent to the non-attending group among those invited, thus leaving a control group comparable to those attending in the invited group.

We estimated the cost effectiveness of screening from a UK health service perspective, for follow-up truncated at 10 years. The relevant unit costs are taken from a recent UK Department of Health report16; these are based on a detailed costing exercise at 2000-1 prices17 uplifted to reflect 2008-9 prices. Events costed include each invitation to screening (£1.74; €2.02; $2.88), reinvitation to screening (£1.70), initial scan (£25.31), recall scan (£61.07), referral for consideration for elective surgery (£411.07), elective surgery (£9165), and emergency surgery (£14 825). We applied discounting at the currently recommended rate of 3.5% per year for both costs and effects. Incremental costs and the cost effectiveness ratio take into account censoring at the end of follow-up by dividing the follow-up into intervals of six months.18 19 We used Fieller’s method to calculate the confidence interval for the incremental cost effectiveness ratio.20

Results

The flow of participants in the trial is as reported previously,5 except for two features. Firstly, of the 1334 men with abdominal aortic aneurysm detected at initial scan, 72% (n=963) had complete clinical follow-up to 10 years according to the protocol; this compares with 76% at seven years. Secondly, inability to follow up deaths because some men may have moved was 2.7% at 10 years, compared with 2.1% at seven years; these men were censored at the time they were last known to be alive.

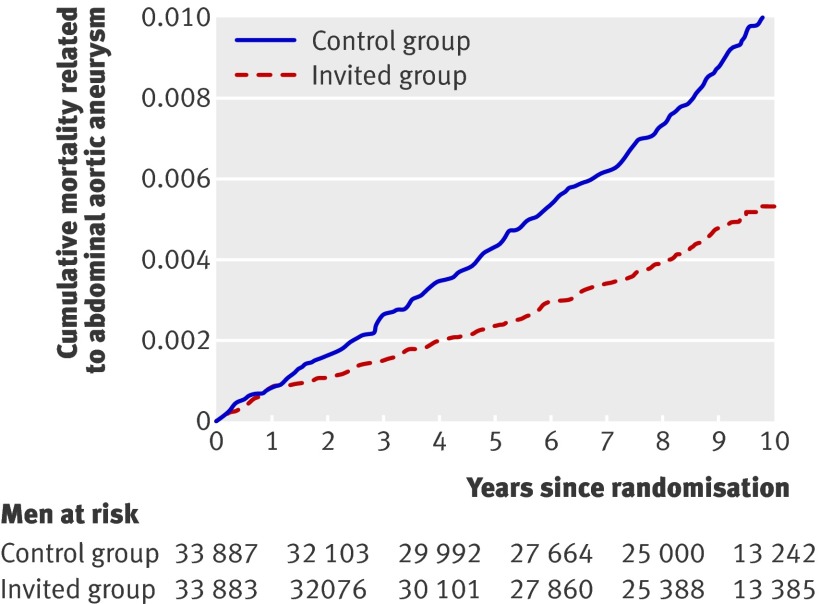

Overall, 155 deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm (absolute risk 0.46%) occurred in the invited group compared with 296 (0.87%) in the control group, a relative risk reduction of 48% (hazard ratio 0.52, 95% confidence interval 0.43 to 0.63; table 1). The benefit seen in earlier years of follow-up was maintained in the later years of follow-up, with continued divergence of the cumulative curves of deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm in the two groups (fig 1). The mean age at death was similar in the invited and control groups (75.0 v 75.4 years). Non-fatal ruptures of abdominal aortic aneurysms were also about halved in the invited group (table 1). Twenty one men in the invited group died within 30 days of elective surgery, and another six men after more than 30 days. Additionally, despite being invited for screening, 170 men subsequently had a ruptured aneurysm. Many of these were, however, excluded from the potential benefit of screening—for example, among those who did not attend screening, those who did not keep an outpatient appointment, those who refused surgery, and those who were considered unfit for surgery (table 2).

Table 1.

Deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm*, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm, and other causes of death

| Category | Control group (n=33 887) | Invited group (n=33 883) |

|---|---|---|

| Deaths related to aneurysm: | ||

| <30 days after elective surgery† | 13 | 21 |

| Ruptured aneurysm‡ | 251 | 110 |

| Ruptured aneurysm of unspecified site§ | 32 | 24 |

| Total No | 296 | 155 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 0.52 (0.43 to 0.63) |

| Ruptured aneurysm: | ||

| Non-fatal rupture | 78 | 42 |

| Total incidence of rupture¶ | 374 | 197 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 0.52 (0.44 to 0.62) |

| Other causes of death: | ||

| Ischaemic heart disease | 2448 | 2324 |

| Other cardiovascular | 1391 | 1430 |

| Non-cardiovascular** | 6346 | 6365 |

| All deaths | 10 481 | 10 274 |

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | 1 (reference) | 0.97 (0.95 to 1.00) |

*Codes 441.3-6 (international classification of diseases, ninth revision), or equivalently codes I71.3-4 and 8-9 (international classification of diseases, 10th revision).

†Those with ICD-9 codes 441.3-6 who died within 30 days of elective surgery are classified here.

‡ICD-9 codes 441.3 (ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm) and 441.4 (abdominal aortic aneurysm without mention of rupture), and all deaths occurring within 30 days of emergency surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm.

§ICD-9 codes 441.5 (ruptured aortic aneurysm at unspecified site) and 441.6 (aortic aneurysm at unspecified site without mention of rupture).

¶Deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm plus incidence of non-fatal ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm.

**Includes 19 deaths of unknown cause.

Fig 1 Cumulative deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm, by time since randomisation

Table 2.

Timing of incidence of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm and deaths in 33 883 men aged 65 or more invited to screening

| Category | Incidence of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (n=197)* | Deaths (n=155) |

|---|---|---|

| Aneurysm not identified by screening programme | ||

| Between randomisation and scan | 3 | 3 |

| After non-attendance at screening (n=6679)† | 72 | 61 |

| After unclear initial scan (n=329) | 2 | 1 |

| After normal initial scan (n=25 541) | 25 | 19 |

| Aneurysm identified by screening programme | ||

| Aneurysm <5.5 cm detected (n=727)‡: | ||

| Between recall scans | 15 | 9 |

| After non-attendance at outpatient department | 15 | 14 |

| Aneurysm ≥5.5 cm detected (n=607)‡: | ||

| After non-attendance at outpatient department | 1 | 1 |

| After refusal of surgery | 4 | 4 |

| After declared unfit for surgery | 12 | 12 |

| Pending decision on surgery | 15 | 6 |

| While awaiting surgery | 9 | 2 |

| After return to surveillance§ | 3 | 2 |

| After elective surgery: | ||

| ≤30 days | 16 | 16 |

| >30 days | 5 | 5 |

*Deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm (including all deaths within 30 days of surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm) and incidence of non-fatal ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm

†Includes six deaths after elective surgery (five within 30 days) after incidental detection of abdominal aortic aneurysm.

‡Aneurysm size based on maximum observed from all scans.

§Aneurysm ≥5.5 cm not confirmed at outpatient visit.

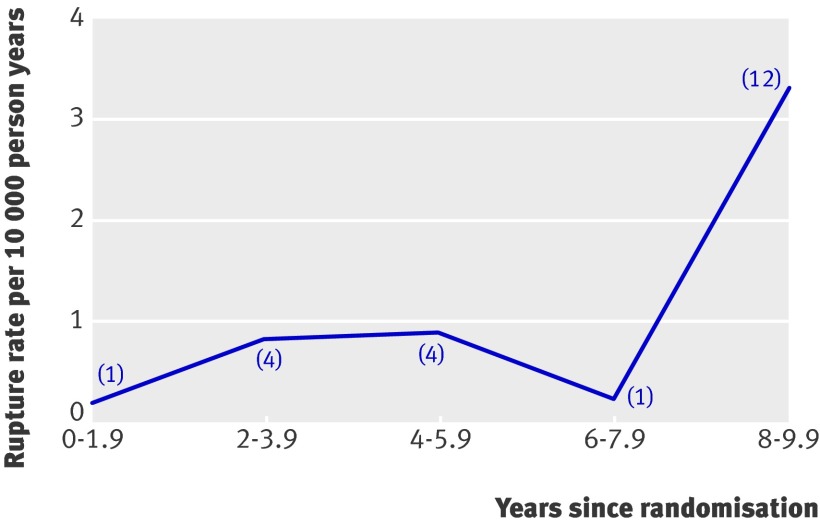

Among those who could potentially benefit from screening, some aneurysms ruptured between recall scans, pending a decision about surgery and while awaiting surgery (table 2). Twenty five ruptures also occurred after the men had had normal initial scans, of which 19 were fatal. The rate of these ruptures increased noticeably after eight years of follow-up (fig 2). In years 8, 9, and 10 (when censoring impacts on the follow-up data available) six, six, and three ruptures occurred, respectively, with corresponding rupture rates per 10 000 person years of 3.0, 3.8, and 5.7. Time since initial scan, rather than age, was the main determinant of this increased risk of rupture.

Fig 2 Rate of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms (number of ruptures in brackets) in men originally screened as normal, by time since randomisation. Three more ruptures were recorded in the limited follow-up after 10 years

Over the 10 years 552 elective operations took place in the invited group and 226 in the control group. The respective 30 day mortality rates of 4% (21/552) and 6% (13/226) were not significantly different (P=0.23). Sixty two men underwent emergency surgery in the invited group compared with 141 in the control group. The respective 30 day mortality rates of 29% (18/62) and 36% (50/141) were not significantly different (P=0.37). Nearly all the operations in MASS were open surgical repairs, with endovascular repair occurring only in the later period of follow-up. Two endovascular repairs were undertaken as emergency procedures (both patients died within 30 days) and 68 as elective procedures, representing 9% (68/778) of all elective operations. The 30 day mortality rate for elective endovascular repair was 3% (2/68).

The benefit of a screening programme is diluted by those who, despite being invited, do not attend: the unbiased estimate of the reduction in deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm among men who were screened was 60% (hazard ratio 0.40, 95% confidence interval 0.32 to 0.50). This estimate is relevant when providing information to individuals about the benefit of screening or when considering the benefit from a screening programme that achieves an attendance rate different to the 80% achieved in MASS.

Total mortality at 10 years was about 30% in each group (table 1). Because deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm comprise about 2% of all deaths and there were no clear differences in any other causes of death, only a small difference was found in all cause mortality (hazard ratio 0.97, 0.95 to 1.00). Although 124 fewer deaths from ischaemic heart disease occurred in the invited group, this difference was not statistically convincing (P=0.06), and the mean age of the men who died was 74.7 in both groups. These findings do not suggest any major general differences in health care between the groups as a result of screening.

The costs per person were greater in the invited group (through the costs of screening and more elective surgery but offset by fewer emergency operations), by an average of £100 (table 3). The extent of reduction in number of deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm in the invited group led to an estimated incremental cost effectiveness ratio of £7600 (95% confidence interval £5100 to £13 000) per life year gained over the 10 years of the trial.

Table 3.

Discounted mean costs and effects per person, based on 10 year follow-up in Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS)

| Variable | Costs (£) | Survival (life days) |

|---|---|---|

| Control group | 108 | 2743.0 |

| Invited group | 208 | 2747.8 |

| Difference (95% CI) | 100 (82 to 118) | 4.8 (2.9 to 6.7) |

| Cost per life year gained (95% CI) | £7600 (£5100 to £13 000) | |

£1.00 (€1.18; $1.65).

Costs based on 2008-9 prices; discounting both costs and survival at 3.5% per year. Survival based on deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm, adjusted for other causes of deaths.

Discussion

The benefit of inviting men aged 65-74 to screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm continues at about the same rate 7-10 years after screening, as observed in previous years. The reduction in number of deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm in MASS is estimated as 42% at four years,4 47% at seven years,5 and now 48% at 10 years. This is surprising as it might be expected that ruptures of the aneurysm in those originally screened as normal and incidental detection of abdominal aortic aneurysm in the control group would erode the benefit over time. Being based on a population based sample of UK men, these figures correspond to the expected benefit that will derive from the UK national screening programme. About 1900 deaths each year, half of the deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm that occur in men aged 65 or more in the UK,21 should be prevented in due course by the screening programme. Such a programme will never prevent all ruptures but to optimise performance our results show that emphasis should be placed on achieving a high initial attendance rate and good adherence to clinical follow-up, preventing delays in undertaking surgery, and maintaining a low operative mortality after elective surgery. More evidence may be needed to choose the best intervals between recall scans, for different sizes of aneurysm less than 5.5 cm22; any strategy needs to balance the effectiveness in preventing ruptures while under surveillance against the costs.

A crucial problem is the extent to which those screened as normal will go on to develop an aneurysm that ruptures and whether rescreening of participants after a normal scan is justified at any stage. We observed a noticeable increase in ruptures after eight years of follow-up; although most were fatal, the absolute numbers remained small. For example, 15 fatal ruptures occurred during years 8-10; over the same period there was an overall reduction of 40 deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm in the group invited to screening compared with the control group. Hence the deaths due to rupture after a normal scan seem not to have impacted yet on the diverging curves from deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm shown in figure 1. Recommending rescreening those with an initial normal scan would only become justified in subsequent years if future analyses show that there is a further noticeable increase in ruptures in this group that is not sufficiently offset by the reduction in number of deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm for those with an aneurysm detected (or rendered unimportant by the overall toll of mortality from all causes).

Cost effectiveness of screening

The survival advantage in terms of life years gained continues to increase with time, as indicated by the diverging curves in figure 1. Because the main costs of the programme (initial screening and elective surgery for those with aneurysm diameter >5.5 cm) occur early on, whereas the benefit in terms of life years increases over time, the cost effectiveness improves when considered over longer time scales. Using the same unit costs and discount rates as in the current analysis, the cost per life year gained is estimated as £41 000 after four years, £14 000 after seven years, and now £7600 after 10 years. The estimate and confidence interval at 10 years is well below the guideline figure of around £25 000 per life year gained for the acceptance of medical technologies and interventions in the NHS.23 Sensitivity analyses using alternative unit costs5 did not change this conclusion. Moreover, the estimates from MASS over time are in line with the figures predicted from a long term health economic model, which was developed based on the first four years of follow-up in MASS.10 This congruence lends credibility to the estimate derived from the model of £2300 per life year gained over the full lifetime for men aged 65, indicating an extremely cost effective programme and even more favourable than estimates from other recent models.11 24

New treatments for aneurysms

New treatments for abdominal aortic aneurysm may impact on a national screening programme and increase its effectiveness. Endovascular repair of aneurysms rather than conventional open repair is now used more widely for elective surgery but was used for only 9% of the elective procedures in MASS. In patients who are fit for open repair, and anatomically suitable for endovascular repair, endovascular repair has lower operative mortality than open repair and fewer deaths related to abdominal aortic aneurysm in the longer term25 26 27 28; it may therefore be preferred by both patients and surgeons. Reliable evidence comparing endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms with open repair is currently available only up to four years of follow-up; it shows no difference in all cause mortality28 but a substantial incidence of graft problems (for example, leaks around the graft or movement of the graft) and need for reinterventions after endovascular repair.26 27 These incur costs, as does the requirement for surveillance of the graft. Based on the large UK trial of endovascular repair, a cost effectiveness modelling study concluded that endovascular repair was more expensive than open repair, was unlikely to be cost effective at current prices, and should be retained as a research technology.29 In patients who are not fit for open repair, the randomised evidence also does not support the use of endovascular repair.30 Recent guidance from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence31 is more optimistic, however, being based on more favourable assumptions about the initial costs and later complications after endovascular repair. It concluded that endovascular repair was an appropriate treatment for abdominal aortic aneurysm, both for fit and unfit patients, provided due account was taken of the patient’s age and fitness, and the size and morphology of the aneurysm. It is clear from these reports that what is required is robust evidence, principally in terms of longer term follow-up from randomised trials of endovascular repair. Until this is available it may be reasonable to assume that endovascular repair has similar cost effectiveness to open repair, a conclusion supported by some recent evidence suggesting roughly equal costs for open repair and endovascular repair over 2.5 years.32 On this basis, the overall cost effectiveness of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm would not be expected to change much if endovascular repair was used, when appropriate, in place of elective open repair. General agreement is that endovascular repair should not be currently used for emergency repairs, except in the context of research studies.31

Although patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm should receive a statin because of their high general cardiovascular risk,33 and the possibility that statins reduce the expansion rate of aneurysms,34 to date no medical treatments have been convincingly shown to reduce the rate of aneurysm expansion over time. Results from observational data suggesting that angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors may be an effective treatment35 require confirmation in a large scale randomised trial.

Limitations of the study

Some potential limitations of the current analyses of MASS should be mentioned. The inclusion of deaths from aortic aneurysm at an unspecified site may have provided a conservative estimate of the benefit of screening, since the use of codes 441.5 and 441.6 (international classification of diseases, ninth revision) may result in the inclusion of some deaths related to thoracic aortic aneurysm. Investigation of the accuracy of cause of death coding on the death certificates in the first four years of follow-up was carried out by an independent mortality working party blinded to group allocation, and showed that inaccuracies in coding had a minimal impact on study outcomes.4 The quality of life data collected in the trial around the time of screening showed no clear adverse or beneficial effects of screening or any long term effects after surgery.4 36 Using general population age specific norms for quality of life,37 the cost per quality adjusted life year (QALY) in MASS at 10 years was £9400 (95% confidence interval £6300 to £16 000).

Although the loss to follow-up for deaths was small as participants were tracked through their NHS number, identification of all patients who had undergone surgical repair was more difficult to achieve. Surgical follow-up was through review of data on surgery for abdominal aortic aneurysm carried out at the local hospitals in each screening area, thus missing operations among those patients who had moved away or had surgery at other hospitals; subsequent deaths within 30 days of surgery would not necessarily be recorded as related to abdominal aortic aneurysm on the death certificate. We were able to estimate the extent of this problem in one MASS centre, by calculating the number of deaths in hospital that occurred outside the area from information on death certificates; this gave a value of 278/4241 (7%). Since this proportion is small, indicating that few people of this age group move out of the area and would be potentially lost to surgical follow-up, it should only have a minor impact on the trial’s results.

Conclusions

We conclude that the UK national screening programme for abdominal aortic aneurysm should, in the long term, halve the mortality rate related to abdominal aortic aneurysm in men aged 65 or more, and that it will be a cost effective programme for the NHS. Rescreening of those originally screened as normal is not currently justified.

What is already known on this topic

Ultrasound screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm in men aged 65 or more reduces mortality in the short term

Rupture of aneurysm in those originally screened as normal, and incidental detection of aneurysms, could reduce the effectiveness of screening over time

What this study adds

The mortality benefit of one-off screening of men aged 65-74 for abdominal aortic aneurysm is maintained up to 10 years, despite an increase in ruptures among those screened as normal

About half of all aneurysm related deaths should be prevented by a national screening programme

The long term cost effectiveness of screening is highly favourable

We thank Stephanie Druce (Chichester) and Liz Hardy (Oxford) for data collection, Martin Buxton (Brunel) for advice on health economics, Lois Kim (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine) for help with statistical programming, and the referees for their comments.

Contributors: SGT, current principal investigator of MASS, supervised the statistical analysis, drafted the paper, and is the guarantor. HAA is the overall trial coordinator for MASS. LG undertook the statistical analyses. RAPS, the original principal investigator of MASS, is responsible for the clinical aspects. All authors reviewed the manuscript and contributed to the final version.

Funding: This work was supported by the Medical Research Council (grant numbers G0601031 and U.1052.00.001). The funder had no role in the design, implementation, analysis, or interpretation of the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Southampton and south west Hampshire ethics committee approved the extended follow-up in MASS.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;338:b2307

References

- 1.UK National Screening Committee. Abdominal aortic aneurysm screening, May 2007. 2008. www.library.nhs.uk/screening/.

- 2.NHS National Services Scotland. Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) screening, Aug 2008. www.nhsnss.org/uploads/board_papers/B0893%20AAAScreening.pdf.

- 3.US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:198-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study Group. The Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study (MASS) into the effect of abdominal aortic aneurysm screening on mortality in men: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:1531-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim LG, Scott RAP, Ashton HA, Thompson SG. A sustained mortality benefit from screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:699-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fleming C, Whitlock EP, Beil TL, Lederle FA. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a best-evidence systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:203-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosford PA, Leng GC. Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(2):CD002945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashton HA, Gao L, Kim LG, Druce PS, Thompson SG, Scott RAP. Fifteen-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial of ultrasonographic screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms. Br J Surg 2007;94:696-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hafez H, Druce PS, Ashton HA. Abdominal aortic aneurysm development in men following a “normal” aortic ultrasound scan. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008;36:553-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim LG, Thompson SG, Briggs AH, Buxton MJ, Campbell HE. How cost-effective is screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms? J Med Screen 2007;14:46-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henriksson M, Lundgren F. Decision-analytical model with lifetime estimation of costs and health outcomes for one-time screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm in 65-year-old men. Br J Surg 2005;92:976-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell HE, Briggs AH, Buxton MJ, Kim LG, Thompson SG. The credibility of health economic models for health policy decision-making: the case of population screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Health Serv Res Policy 2007;12:11-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim LG, Thompson SG. Uncertainty and validation of health economic decision models. Health Econ 2009. Feb 10 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Lin CC, Johnson NJ. Decomposition of life expectancy and expected life-years lost by disease. Stat Med 2006;25:1922-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loeys T, Goetghebeur E. A causal proportional hazards estimator for the effect of treatment actually received in a randomized trial with all-or-nothing compliance. Biometrics 2003;59:100-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UK Department of Health. Impact assessment of a national screening programme for abdominal aortic aneurysms, Jul 2008. www.ialibrary.berr.gov.uk/ImpactAssessment/.

- 17.Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study Group. Multicentre aneurysm screening study (MASS): cost effectiveness analysis of screening for abdominal aortic aneurysms based on four year results from randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2002;325:1135-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin DY, Feuer EJ, Etzioni R, Wax Y. Estimating medical costs from incomplete follow-up data. Biometrics 1997;53:419-34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Willan AR, Lin DY, Manca A. Regression methods for cost-effectiveness analysis with censored data. Stat Med 2005;24:131-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willan AR, O’Brien BJ. Confidence intervals for cost-effectiveness ratios: an application of Fieller’s theorem. Health Econ 1996;5:297-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Office for National Statistics. Review of the national statistician on deaths in England and Wales, 2007. www.statistics.gov.uk.

- 22.Brady AR, Thompson SG, Fowkes FGR, Greenhalgh RM, Powell JT. Abdominal aortic aneurysm expansion: risk factors and time intervals for surveillance. Circulation 2004;110:16-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rawlins MD, Culyer AJ. National Institute for Clinical Excellence and its value judgments. BMJ 2004;329:224-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wanhainen A, Lundkvist J, Bergqvist D, Björck M. Cost-effectiveness of different screening strategies for abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 2005;41:741-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.EVAR Trial Participants. Comparison of endovascular aneurysm repair with open repair in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 1), 30-day operative mortality results: randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2004;364:843-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.EVAR Trial Participants. Endovascular aneurysm repair versus open repair in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 1): randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;365:2179-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dutch Randomized Endovascular Aneurysm Management (DREAM) Trial Group. Two-year outcomes after conventional or endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2398-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lederle FA, Kane RL, MacDonald R, Wilt TJ. Systematic review: repair of unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:735-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Epstein DM, Sculpher MJ, Manca A, Michaels J, Thompson SG, Brown LC, et al. Modelling the long-term cost-effectiveness of endovascular or open repair for abdominal aortic aneurysm. Br J Surg 2008;95:183-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.EVAR Trial Participants. Endovascular aneurysm repair and outcome in patients unfit for open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm (EVAR trial 2): randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;365:2187-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Abdominal aortic aneurysm—endovascular stent-grafts: technology appraisal, Feb 2009. www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/TA167.

- 32.Mani K, Björck M, Lundkvist J, Wanhainen A. Similar cost for elective open and endovascular AAA repair in a population-based setting. J Endovasc Ther 2008;15:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brady AR, Fowkes FGR, Thompson SG, Powell JT. Aortic aneurysm diameter and the risk of cardiovascular mortality. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis and vascular biology 2001;21:1203-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guessous I, Periard D, Lorenzetti D, Cornuz J, Ghali WA. The efficacy of pharmacotherapy for decreasing the expansion rate of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2008;3:e1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hackam DG, Thiruchelvam D, Redelmeier DA. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and aortic rupture: a population-based case-control study. Lancet 2006;368:659-65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marteau TM, Kim LG, Upton J, Thompson SG, Scott RAP. Poorer self-assessed health in a prospective study of men with screen detected abdominal aortic aneurysm: a predictor or consequence of screening outcome? J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:1042-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kind P, Hardman G, Macran S. UK population norms for EQ-5D. Discussion paper 172. University of York, Centre for Health Economics, 1999.