Abstract

By using the mixed solvent of 50% H2O/50% D2O and employing deuterium decoupling, TROSY experiments exclusively detect NMR signals from semideuterated isotopomers of carboxamide groups with high sensitivities for proteins with molecular weights up to 80 kDa. This isotopomer-selective strategy extends TROSY experiments from exclusively detecting backbone to both backbone and side-chain amides, particularly in large proteins. Because of differences in both TROSY effect and dynamics between 15N–HE{DZ} and 15N–HZ{DE} isotopomers of the same carboxamide, the 15N transverse magnetization of the latter relaxes significantly faster than that of the former, which provides a direct and reliable stereospecific distinction between the two configurations. The TROSY effects on the 15N–HE{DZ} isotopomers of side-chain amides are as significant as on backbone amides.

Keywords: TROSY, NMR spectroscopy, Sensitivity enhancement, Isotopomer selectivity, Stereospecific NMR assignment, Side-chain amides

1. Introduction

Carboxamide moieties of asparagine (Asn) and glutamine (Gln) residues can serve as either hydrogen bond donors and/or acceptors. Consequently, many Asn and Gln residues play important structural and functional roles in proteins [1]. The geminal protons of the carboxamides usually have different chemical shifts, as a result of the slow interconversion of two possible configurations due to the partial double-bond character of the side-chain C′–Nδ/ε (Asn/Gln) amide bond. The geminal amide proton with a trans (E) configuration with respect to the carboxamide oxygen atom normally shows a relatively downfield chemical shift, whereas the other in the cis (Z) configuration has an upfiled chemical shift. However, this order could be reversed due to neighboring aromatic ring current effects and/or strong hydrogen bonding interactions. Therefore, the stereospecific assignment of carboxamide resonances is the kickoff step towards further structural and functional studies of these important groups by NMR.

Traditionally, the resonance assignment of side-chain amide groups in small proteins is obtained mainly through the analysis of HNCACB [2] and (H)CC(CO)-NH-TOCSY [3–4] data, or by employing H2N-HSQC-based [5] triple-resonance NMR experiments [2,5–8]. Very often, the task can not be fulfilled exclusively with these through-bond correlations, and the through-space information, i.e. NOE [9] data, is required as a remedy. Alternatively, the assignment can be achieved by performing H2NCOE.COSY [10], EZ-HMQC-NH2 [11] and the multiplicity-edited 15N–1H HSQC experiments [12–13]. However, all these methods rely on small scalar couplings and hence the procedure is rather time-consuming and uncertainties may arise in practice. For large proteins, the requisition for partially or fully deuterated NMR samples has significantly limited the amount of NOEs available and resonances from 15N1H2 groups are not observable at all if TROSY-based triple-resonance experiments are performed under normal experimental and sample conditions.

The TROSY [14] NMR technique, which makes constructive use of chemical shift anisotropy/dipole–dipole (CSA/DD) relaxation interferences in protein backbone amides and imino groups in nucleic acids, has pushed the size limit of biomacromolecules for NMR structural studies beyond 100 kDa [15–17]. However, the resonances of amino moieties, e.g. Asn/Gln side-chain amides in proteins and NH2 groups in nucleic acids, are not observed in standard TROSY experiments. Pervushin et al. reported a simple modification of the normal TROSY method for the simultaneous detection of backbone 15N–1H amide, aromatic 13C–1H and side chain 15N–1H2 moieties [18]. By shortening delay times in both INEPT [19] and ST2-PT [20] elements from the usual 2.7 ms, which is optimized for 15N–1H moieties, to 1.7 ms, resonances stemming from some 15N–1H2 moieties of OmpA solubilized in DHPC could be restored at the cost of some attenuation of signals of backbone amides [18]. The observed NH2-TROSY signal is the narrowest component among eight possible multiplets for each amide proton in the fully coupled HSQC spectrum, assuming the scalar coupling between geminal protons can be ignored. Unfortunately, unlike an NH moiety, whose CSA/DD interactions may cancel out almost completely at the magnetic field strength around 1 GHz of proton frequency [14], relaxation properties of 15N1H2/13C1H2 groups are much more complicated [21–23]. The TROSY effect on N1H2 groups is rather limited in comparison with 13C1H2 groups, due to the additional large CSA interaction of the 15N nucleus. Apparently, all NH2 TROSY signals in the literature were from flexible solvent-exposed side-chain amides (see Fig. 3 in reference [18]).

In this communication, we show that the TROSY methodology is also applicable to the detection of side-chain amides with high sensitivity, especially for large proteins, by using the mixed solvent of 50% H2O/50% D2O and employing deuterium decoupling. Such TROSY experiments exclusively detect semideuterated isotopomers of side-chain carboxamides of Asn/Gln residues with enhanced sensitivity just as in the detection of backbone amides. This isotopomer-selective (IS) TROSY strategy has been applied to the NMR measurement of side-chain amides of yeast cytosine deaminase (yCD), a 35 kDa homodimeric protein with 11 Asn/Gln residues in each protomer. All side-chain amides showed strong signals in the IS-TROSY-based experiments, whereas signals of about half of these amides were either very weak or not detectable at all in standard HSQC experiments with a comparable measuring time. In addition, due to differences in both TROSY effects and dynamics between the 15N–HE{DZ} and 15N–HZ{DE} isotopomers of the same carboxamide, the 15N transverse magnetization of the former relaxes far more slowly than that of the latter, which provides a direct and sensitive method for the stereospecific assignment of side-chain amide protons.

2. Results and discussion

Instead of detecting NH2 signals directly with standard protein NMR samples in 95% H2O/5% D2O, there is another way around for the observation of side-chain amides. In the mixed solvent of 50% H2O/50% D2O, there are four possible isotopomers, NHEHZ, NHEDZ, NDEHZ and NDEDZ, for a given NH2 moiety, where E stands for the configuration in which the amide proton or deuteron is trans to the carboxamide oxygen and Z for the cis configuration. Without losing generality, it is assumed that the relative population of each isotopomer is about equal, i.e. D/H isotope fractionation factors at all sites are close to one [24–25]. Since the gyromagnetic ratio of a deuteron is 6.5 times smaller than that of a proton, semideuterated NHD isotopomers potentially have a much better relaxation behavior than an NH2 group. In fact, the Wüthrich group reported an elegant scheme for the indirect measurement of deuterium relaxation rates of Asn/Gln side-chain amides through selectively observing NHE{DZ}/NHE{DZ} isotopomers with 15N-labeled protein/DNA samples in the solvent of 45% H2O and 55% D2O [26]. However, the pulse sequence was derived from the conventional 2D 15N–1H HSQC experiment and no TROSY was included. Moreover, signal intensities were significantly attenuated by the strong scalar relaxation of the second kind [27] from deuterium during the total 24 ms 15N↔2H magnetization transfer periods since deuterium relaxes so fast. As a result, the method could only be applied to relatively small proteins. The observed small difference in deuterium relaxation rates between NHEDZ and NDEHZ isotopomers confirmed the earlier prediction and led to the conclusion that in general the E configuration is slightly more flexible than the Z configuration [26].

In this work, we employed TROSY NMR techniques for the exclusive detection of semideuterated NHE{DZ} and N{DE}HZ isotopomers of protein side-chain amides with high sensitivities in the 50% H2O/50% D2O mixed solvent. To demonstrate this strategy, we recorded a set of 2D 15N–1H IS-TROSY and conventional 15N–1H HSQC spectra of yCD, a 35 kDa homodimeric enzyme [29–30], in complex with the inhibitor 5FPy, a transition state analogue for the activation of the prodrug 5-fluorocytosine, on a Bruker AVANCE 900 MHz (1H frequency) spectrometer running at either room temperature, 25 °C, or 5 °C to mimic a larger molecule. The ratio of principle components of the diffusion tensor, Dz:Dy:Dx, is 1.14:1.07:1.00 for the yCD complex based on 15N spin relaxation data recorded on a 600 MHz NMR spectrometer at 25 °C, indicating that the motional anisotropy of yCD is very small. The global tumbling time (correlation time τc) is 18.6 ns. The rotational diffusion tensor and correlation time were obtained from R2/R1 ratios using the program TENSOR2 [32]. The correlation time was estimated to be ~40 ns at 5 °C using Stokes' Law, which corresponds to a 70–80 kDa protein at room temperature [33]. This estimation is consistent with the result of the 42 kDa MBP/β-cyclodextrin complex that has correlation times of 23 ns at 25 °C and 46 ns at 5 °C [16]. yCD has six Asn and five Gln residues per protomer. In 2D 15N–1H HSQC spectra of yCD, only 8 pairs out of all 11 Asn/Gln side-chain NH2 resonances showed up after an hour of data accumulation; side-chain NH2 resonances of Asn 51 and Gln 55 were hardly seen even after up to two hours of accumulation and those of Asn 40, Asn 111 and Asn 113 were rather weak and could not be assigned with conventional triple-resonances NMR experiments [34–36]. Ironically, all Asn/Gln residues with missing or weak side-chain resonances are either structurally or catalytically important and those that showed strong signals are flexible and exposed to solvent [29–30,37]. However, strong signals of side-chain amide for all 11 Asn/Gln residues can be restored through the combined use of 50% H2O/50% D2O mixed solvent and deuterium decoupling in TROSY/HSQC experiments. Most importantly, just like backbone resonances, the lineshape of these side-chain signals in TROSY spectra is sharper than the corresponding peaks in HSQC spectra, demonstrating the applicability of the IS-TROSY technique to side-chain amides of large proteins.

Shown in Figure 1 are close-ups of (a) 2D 15Nδ–1HE and (b) 2D 15Nδ–1HZ correlation peaks of Asn 113, where E stands for the trans configuration and Z for the cis configuration, together with neighboring resonances of backbone amides of Gln 55, Asn 113, Lys 115 and Glu 119. For a given side-chain amide, the relative population of each of four isotopomers, NHEHZ, NHEDZ, NDEHZ and NDEDZ, is about 25% in the solvent of 50% H2O/50% D2O. On the other hand, the population of the NH2 group is over 90% in the solvent of 93% H2O/7% D2O. Thus, one would expect a two-fold sensitivity enhancement of either the downfield or upfield NH2 resonance in the solvent of 93% H2O/7% D2O over the resonance of either NHEDZ or NDEHZ isotopomer in the solvent of 50% H2O/50% D2O. In practice, however, the sensitivity of NH2 resonances is largely offset by faster relaxation rates and the resonance intensity is significantly attenuated. This is clearly indicated by comparing relative intensities of corresponding resonances as shown in Figure 1. At 25 °C, the HSQC resonance of semideuterated isotopomers in 50% H2O/50% D2O (panel B) is at least two times stronger than the NH2 resonance in 93% H2O/7% D2O (panel A) and at 5 °C the NH2 resonance is not even observable (panel F). More importantly, the TROSY resonance of the semideuterated isotopomers is much stronger than the corresponding HSQC signal. At 25 °C, in the deuterium decoupled 15N–1H HSQC spectrum (panel B), the upfield NH{D} resonance in 15N dimension is much stronger (6 times in peak height) than the downfield NH2 signal, although the populations of the two isotopomers are expected to be similar [24–25]. Without 15N/1H decoupling (panel C), TROSY components in the HSQC spectrum, which are at upfield in 1H dimension and downfield in 15N dimension in each quartet, are much stronger than the corresponding non-TROSY components for both backbone and side-chain amides. The corresponding TROSY peak (panel D), as recorded with the deuterium-decoupled TROSY experiment which exclusively detects the NH{D} isotopomer, is 2 times stronger than the corresponding peak in the HSQC spectrum (panel B), i.e. 12 times stronger than the NH2 peak, and has a narrower linewidth. By shortening the delay time in INEPT [19] and ST2-PT [20] elements from 2.7 ms (panel D) to 1.7 ms (panel E), the intensity of NH{D} TROSY resonance is similar, but a tiny NH2 TROSY peak, as suggested by Pervushin et al. [18], emerges at ~ 90 Hz downfield in 15N dimension, which is much weaker than that of NH{D} isotopomer. Lowering the measuring temperature to 5 °C, which makes the apparent molecular weight of yCD commensurate with an 80 kDa protein at room temperature, neither the NH2 HSQC peak (panels F-H) nor the NH2 TROSY peak (panels I and J) is detectable, but the NH{D} IS-TROSY resonance is still prominent (panels I and J, with 2.7 ms and 1.7 ms INEPT/ST2-PT delay times, respectively), verifying the importance of employing IS-TROSY for large proteins. Significant TROSY effects on both E, panels of (a), and Z, panels of (b), configurations have been observed. The large TROSY effect on side-chain carboxamides makes it possible to perform triple-resonance experiments for NMR structural and dynamics studies on these important side-chain groups in large proteins. Even more interestingly, the TROSY component of the E configuration has a narrower linewidth than that of the corresponding Z configuration (panels D, E, I and J), in particular at lower temperature (panels I and J), i.e. for larger proteins, indicating that the TROSY effect is more significant in the E configuration (see Figure 2 and the discussion in the text).

Fig. 1.

Close-ups of (a) 2D 15Nδ–1HE correlation peaks and (b) 2D 15Nδ–1HZ correlation peaks of Asn 113 side-chain amide of 100% 13C/15N-labeled and 75% deuterated (random) yCD (1.8 mM protomer concentration) in complex with the inhibitor 5FPy (20 mM). The mixed solvent of 50% H2O/50% D2O or 93% H2O/7% D2O was buffered with 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0) with addition of 100 μM NaN3 and 20 μM DSS as an internal NMR reference. The NMR sample had been equilibrated at room temperature for weeks before measuring. All spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE 900 MHz spectrometer equipped with a room temperature TXI probe with three-axis actively shielded pulsed field gradients. Each spectrum was accumulated for about 2 hours with 8 scans and a 2 s delay time. Maximum acquisition times were 71 ms and 66 ms in the direct and indirect dimensions, respectively. Data were zero-filled before Fourier transformation by a factor of 2 in 1H dimension and 3 in 15N dimension. All spectra were processed in the same manner. NMR experiments were performed at either 25 °C (panels A–E) or 5 °C (panels F–J). Panels A and F are FHSQC [28] spectra with deuterium decoupling in the indirect dimension using the sample in 93% H2O/7% D2O and all other panels are spectra with the sample in 50% H2O/50% D2O. Panels B and G are FHSQC spectra with deuterium decoupling in the indirect dimension; spectra in panels C and H were recorded with the same experiment but without 15N/1H decoupling in both dimensions. Panels D and I are IS-TROSY spectra with a 2.7 ms delay time in both INEPT [19] and ST2-PT [20] elements; spectra of panels E and J are the same as D and I, respectively, but with a shorter (1.7 ms) INEPT/ST2-PT delay time. The small arrow in each panel indicates the position where the slice was taken. The tiny peak indicated with an asterisk in panels D and E of (a) is the folded side-chain resonance of an arginine residue. Backbone resonances of residues Q55, N113, K115 and E119 that are close to the side-chain resonances of N113 are also indicated.

Fig. 2.

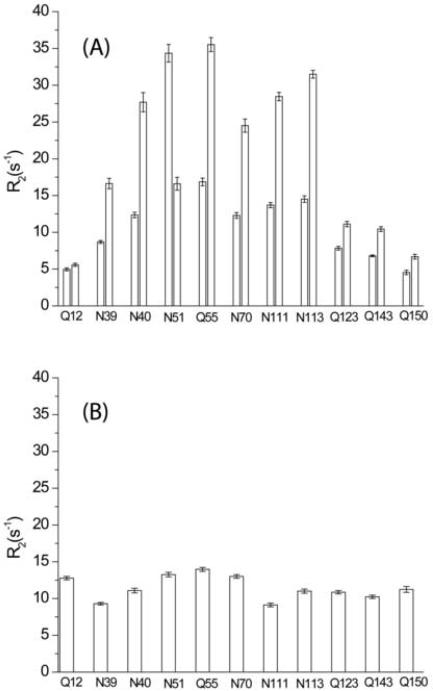

Transverse relaxation rates of Asn/Gln residues in yCD as measured with the isotopomer-selective TROSY-CPMG experiment, which is derived from the standard TROSY-CPMG relaxation dispersion experiment [48] with the addition of broad-band deuterium decoupling whenever the 15N magnetization is transverse. Data were recorded at 25 °C with 32 transients for each FID and a 2.5 s repetition time, resulting in ~ 5 hours for each spectrum. A 0.5 ms CPMG interval was used and 10 points were measured with total CPMG delay times of 0, 4, 8, 16, 24, 36, 64, 88, 112, and 160 ms. Relaxation decays were fitted with a monoexponential function and errors were propagated from the noise level of NMR spectra. Panels A and B are the histograms of 15N transverse relaxation rates, R2, of the side-chain and main-chain amides of Asn/Gln residues, respectively. For side-chain amides (panel A), each residue has two bars has a pair of bars with the left and the right bar corresponding to the 15N1HE{DZ} isotopomer and the right bar to the 15N1HZ{DE} isotopomer. Note that the 1HE resonance of Asn 51 is upfield relative to the 1HZ resonance.

It is worthwhile to point out the importance of employing broad-band deuterium decoupling whenever the 15N magnetization is transverse. At the outset of the development of heteronuclear NMR techniques for biomolecular applications, it had been noticed that adjacent to Asn/Gln side-chain NH2 correlation peaks there were distinct shadow-like signals at about −0.70 ppm upfield in the 15N dimension [38]. These small peaks are known as the result of deuterium isotope effects from the semideuterated NHD isotopomers, since protein NMR samples usually contain 5%–10% D2O for locking the field. The lineshape of these satellites is sharp in 1H dimension. Because the strong proton-proton DD interaction in an NH2 moiety has been substituted by the much weaker proton-deuteron interaction, and the small scalar coupling between geminal protons is removed. On the other hand, the short longitudinal relaxation time, T1, of the coupled deuterium significantly shortens the transverse relaxation time, T2, of the nitrogen and thus a broad lineshape in the indirect dimension results. Fortunately, the scalar relaxation can be efficiently quenched with continuous broad-band deuterium decoupling schemes [38–39]. Consequently, a much better relaxation behavior of the semideuterated NHD isotopomers is restored and the shadow signals are sharpened in the indirect dimension. The use of 50% H2O/50% D2O mixed solvent maximizes the population of NHD isotopomers.

The rationale of the application of TROSY techniques to side-chain carboxamides lies in the fact that the electronic distribution and molecular geometry, and thus magnitudes and orientations of DD and CSA interactions, of Asn/Gln side-chain carboxamides are very similar to the backbone peptide bond [40], and thus the large TROSY effect on backbone amide is expected to hold on Asn/Gln side-chains as well. Because physical constants and spatial variables of Hamiltonians for both DD and CSA interactions can be expressed with second-order spherical harmonics, they have the same transformation properties under rotation. Therefore, interference processes or the so called “cross-correlations” between the two different relaxation mechanisms may arise. For simplicity, we consider a backbone amide or a side-chain NH{D} isotopomer moiety of a deuterated protein in 50% H2O/50% D2O mixed solvent as an isolated 15N–1H spin pair. For 1JNH < 0, if neglecting the contribution from conformational exchange, the 15N transverse relaxation rate of the TROSY [14] component (the downfield 15N doublet component) can be denoted as [41–44]

| (1) |

where λ is the autorelaxation rate and η the cross-correlation relaxation rate. Both of them can be expressed in terms of spectral density functions [27]

| (2) |

and

| (3) |

in which

| (4) |

| (5) |

where α is defined as the ratio of the strength of 15N CSA and 15N–1H DD interactions, rNH is the 15N–1H internuclear distance, σ‖ and σ⊥ are the parallel component (aligned with the unique axis) and perpendicular component of the CSA tensor, respectively, and Jdd(ω), Jcc(ω), and Jcd(ω) are the spectral density functions for dipolar autocorrelation, CSA autocorrelation, and dipolar–CSA cross correlations, respectively. For a rigid molecule with isotropic rotational diffusion, the following relationship holds among the spectral density functions [41]:

| (6) |

As pointed out by Tjandra et al. [42], this relationship is still a good approximation even in the presence of internal motion that can be described by equivalent independent restricted rotations around three mutually orthogonal axes, as long as the angle θ between the unique axes of the CSA and dipolar tensors is small. For large molecules under slow isotropic tumbling rotations, the contribution of the high frequency terms in equation (2) can be safely ignored and the equation is reduced to

| (7) |

Taken equations (3), (6) and (7) together, the ratio of the cross-correlation relaxation rate and the autorelaxation rate becomes

| (8) |

Similarly, analysis of the 1HN transverse relaxation rate of the TROSY [14] component (the upfield 1H doublet component) leads to the ratio

| (9) |

Now α is the ratio of the strength of 1HN CSA and 15N–1H DD interactions. When the DD and CSA interactions cancel out completely, ρN reaches its maximum, 1, and a perfect TROSY effect results. But due to imperfect cancellation the TROSY effect is smaller in practice. As pointed out by Pervushin et al. [14], at a magnetic field around 1 GHz (1H frequency), strengths of DD and CSA interactions within the 15N–1H moiety are about equal, i.e. α≈ 1, and therefore the second-rank Legendre polynomial of cosine function of the angle θ, P2(cosθ) = (3cos2θ − 1)/2, serves as a scaling factor for the TROSY effect. When α≈ 1, the ratio ρH is close to ρN for large biological molecules at high magnetic fields, since J(0) is much larger than J(ωN). Because the angle θ is small (17–24°) [45–46] for protein backbone amides, both ratios of equations (8) and (9) are rather close to 1 (0.75–0.87) and a significant TROSY effect results.

For side-chain amides, however, the situation is not apparent due to the existence of geminal amide protons. In essence, both the electronic distribution and the molecular geometry and thus the strengths and orientations of corresponding DD and CSA interactions of a side-chain carboxamide are very similar to those of a backbone peptide bond, if taking the position of the E proton as the backbone amide proton and the Z proton as the α-carbon atom [40,47]. Hence, without considering the contribution from the 1HZ proton, the TROSY effect on the 15N–1HE pair should be similar to that on the backbone, provided that the angle between the unique axes of CSA and dipolar tensors is small. Indeed, previous solid-state NMR studies [47] have shown that the angle θ within the 15N–1HE pair of an Asn side-chain amide is about 30° and the corresponding angle within the 15N–1HZ pair is about 150°. Thus, both moieties have the same TROSY scaling factor, 0.63, which should lead to similar significant TROSY effects on the two configurations, but the TROSY effects are slightly smaller than that on the backbone amides. The situation for a Gln side-chain amide is likely to be the same as for an Asn carboxamide. The simplest way to mimic the absence of either the E or Z proton is replacing one of them, but not both, with a deuteron, which has a much smaller gyromagnetic ratio, then either 15N–1HE{DZ} or 15N–1HZ{DE} isotopomer should behave just like the backbone 15N–1HN moiety. These semideuterated isotopomers can be most conveniently prepared with NMR samples in the 50% H2O/50% D2O mixed solvent. Moreover, signals of semideuterated isotopomers can be exclusively detected by the TROSY technique and manifest a high sensitivity as those of backbone amides, when broad-band deuterium decoupling is employed. As shown in Figure 1, significant TROSY effects on both semideuterated isotopomers are observed, but the relative transverse relaxation rates of the two isotopomers appear different.

Figure 2 shows histograms of transverse relaxation rates, R2, of 15N spins of side-chain amides in yCD as measured with an IS-TROSY-CPMG experiment. Unexpectedly, the 15NHZ{DE} moiety (the Z configuration) relaxes much faster than the corresponding 15NHE{DZ} moiety (the E configuration), particularly those of “rigid” hydrogen-bonded ones, Asn 40, Asn 51, Gln 55, Asn 70, Asn 111 and Asn 113. The 15NHZ{DE} moieties of these residues relax about 2 times faster than the corresponding 15NHE{DZ} moieties (note that the 1HE resonance of Asn 51 is upfield relative to the 1HZ resonance). More interestingly, the latter have similar relaxation rates to the backbone amide. It should be noted that backbone amides of all Asn/Gln residues are hydrogen bonded, with the sole exception of Gln 12. Dose such a significant difference in relaxation rates between the two isotopomers reflect a major contribution of different dynamics? The deuterium relaxation studies performed by Pervushin et al. [26] nicely confirmed the previous prediction that the E configuration is more flexible than the Z configuration for a given Asn/Gln side-chain amide due to the restricted rotational freedom in the latter. However, this difference in dynamics is too small to account for the difference in transverse relaxation rates of the TROSY components as observed in the IS-TROSY-CPMG experiment. Therefore, the observation in Figure 2 must stem from the difference in the cancellation between DD and CSA interactions. Although 15N–1HE and 15N–1HZ bonds are assumed to have the same length (1.02 Å) for most NMR applications, the 15N–1HE bond is likely to be 1–2% shorter than the 15N–1HZ bond [49–50], resulting in up to 4% larger DD interaction and possibly a 10% difference in the TROSY effect. But this is still marginal to account for the large difference in the relaxation rates. Then, the only possible explanation is that the angle θ for the 15N–1HE pair is not 30° but smaller. For instance, a 20–25° angle leads to a scaling factor of 0.73–0.83, similar to that for backbone amides. On the other hand, the corresponding angle for the 15N–1HZ pair will be 140–145° and result in a scaling factor of 0.38–0.50, about half of that for the 15N–1HE pair. Side-chain amides of the rest Asn/Gln residues, Q12, N39, Q123, Q143 and Q150, are not hydrogen bonded. The difference in relaxation rates of these side-chains is much smaller, because of conformational and chemical exchange averaging, but still very clear.

Because the above difference in the relaxation properties is independent of chemical shifts, the measurement can be directly used for the stereospecific NMR assignment of Asn/Gln carboxamides. Relaxation rates of semideuterated isotopomers with the E configuration are similar to that of the corresponding backbone amides, indicating a similar TROSY effect and thus justifying the applicability of TROSY-based NMR experiments for the measurement of side-chain amides. Actually, we have achieved a simultaneous assignment of both backbone and side-chain amides of yCD with IS-TROSY-based triple-resonance NMR experiments [51].

3. Conclusions

In this work, we have demonstrated that the TROSY methodology, which has been very successful in the NMR detection of backbone amides of large proteins, can be used for the measurement of side-chain carboxamides of Asn and Gln residues. By using the mixed solvent of 50% H2O/50% D2O and employing deuterium decoupling, TROSY experiments exclusively detect signals from semideuterated isotopomers of carboxamide groups with high sensitivities for proteins of up to 80 kDa. The strategy has been applied to the 35 kDa yCD, a homodimeric protein, which contains 11 Asn and Gln residues per protomer. This IS-TROSY approach can be readily incorporated into the existing TROSY-based NMR experiments for both structural and dynamics studies of side-chain amides in large proteins. For instance, NOEs involving side-chain amides are missing in normal TROSY-based NOESY measurements [52–55], but can be restored with the strategy as described in this work. The strategy can also be readily incorporated into the existing CPMG-based 15N relaxation dispersion methods [48,56] for measuring the dynamic properties of this class of important functional groups.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work made use of a Bruker AVANCE 900 MHz NMR spectrometer funded in part by Michigan Economic Development Corporation and a Varian INOVA 600 MHz NMR spectrometer funded in part by NSF Grant BIR9512253. The work was partially supported by NIH Grant GM58221 (H.Y.). A.L. was a recipient of an IRGP New Faculty Award at MSU.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Appendix A. Supporting data Supporting data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at ……

References

- [1].Creighton TE. Proteins: Structures and Molecular Properties. Second Edition Freeman, W. H. and Company; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wittekind M, Mueller L. HNCACB, a high-sensitivity 3D NMR experiment to correlate amide-proton and nitrogen resonances with the alpha-carbon and beta-carbon resonances in proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 1993;B 101:201–205. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Grzesiek S, Anglister J, Bax A. Correlation of backbone amide and aliphatic side-chain resonances in 13C/15N-enriched proteins by isotropic mixing of 13C magnetization. J. Magn. Reson. 1993;101 B:114–119. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Logan TM, Olejniczak ET, Xu RX, Fesik SW. A general method for assigning NMR spectra of denatured proteins using 3D HC(CO)NH-TOCSY triple resonance experiments. J. Biomol. NMR. 1993;3:225–231. doi: 10.1007/BF00178264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Farmer BT, II, Venters RA. Assignment of aliphatic side-chain 1H/15N resonances in perdeuterated proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 1996;7:59–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00190457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yamazaki T, Yoshida M, Nagayama K. Complete assignments of magnetic resonances of ribonuclease H from Escherichia coli by double- and triple-resonance 2D and 3D NMR spectroscopies. Biochemistry. 1993;32:5656–5669. doi: 10.1021/bi00072a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Vis H, Boelens R, Mariani M, Stroop R, Vorgias CE, Wilson KS, Kaptein R. 1H,13C, and 15N resonance assignments and secondary structure analysis of the HU protein from Bacillus stearothermophilus using two- and three-dimensional double- and triple-resonance heteronuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 1994;33:14858–14870. doi: 10.1021/bi00253a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schubert M, Oschkinat H, Schmieder P. MUSIC, selective pulses, and tuned delays: amino acid type-selective 1H–15N correlations, II. J. Magn. Reson. 2001;148:61–72. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2000.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wüthrich K. NMR of Proteins and Nucleic Acids. Wiley; New York: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Löhr F, Rüterjans H. H2NCO–E.COSY, a simple method for the stereospecific assignment of side-chain amide protons in proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 1997;124:255–258. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1996.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].McIntosh LP, Brun E, Kay LE. Stereospecific assignment of the NH2 resonances from the primary amides of asparagine and glutamine side chains in isotopically labeled proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 1997;9:306–312. doi: 10.1023/A:1018635110491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Parella T, Sánchez-Ferrando F, Virgili A. Improved sensitivity in gradient-based 1D and 2D multiplicity-edited HSQC experiments. J. Magn. Reson. 1997;126:274–277. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cai M, Huang Y, Clore GM. Accurate orientation of the functional groups of asparagine and glutamine side chains using one- and two-bond dipolar couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:8642–8643. doi: 10.1021/ja0164475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Pervushin K, Riek R, Wider G, Wüthrich K. Attenuated T2 relaxation by mutual cancellation of dipole-dipole coupling and chemical shift anisotropy indicates an avenue to NMR structures of very large biological macromolecules in solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:12366–12371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Salzmann M, Pervushin K, Wider G, Senn H, Wüthrich K. NMR assignment and secondary structure determination of an octameric 110 kDa protein using TROSY in triple resonance experiments. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:7543–7548. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yang D, Kay LE. TROSY triple-resonance four-dimensional NMR spectroscopy of a 46 ns tumbling protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:2571–2575. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Fiaux J, Bertelsen EB, Horwich AL, Wüthrich K. NMR analysis of a 900K GroEL-GroES complex. Nature. 2002;418:207–211. doi: 10.1038/nature00860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Pervushin K, Braun D, Fernández C, Wüthrich K. [15N, 1H]/[13C, 1H]-TROSY for simultaneous detection of backbone 15N–1H, aromatic 13C–1H and side-chain 15N–1H2 correlations in large proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 2000;17:195–202. doi: 10.1023/a:1008399320576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Morris GA, Freeman R. Enhancement of nuclear magnetic resonance signals by polarization transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1979;101:760–762. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Pervushin K, Wider G, Wüthrich K. Single transition-to-single transition polarization transfer (ST2-PT) in [15N, 1H]-TROSY. J. Biomol. NMR. 1998;12:345–348. doi: 10.1023/A:1008268930690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Fagerness PE, Grant DM, Kuhlmann KF, Mayne CL, Parry RB. Spin-lattice relaxation in coupled three spin systems of the AIS type. J. Chem. Phys. 1975;63:2524–2532. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kumar A, Grace RCR, Madhu PK. Cross-correlations in NMR. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2000;37:191–319. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Miclet E, Williams DC, Jr., Clore GM, Bryce DL, Boisbouvier J, Bax A. Relaxation-optimized NMR spectroscopy of methylene groups in proteins and nucleic acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:10560–10570. doi: 10.1021/ja047904v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].LiWang A, Bax A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. Equilibrium protium/deuterium fractionation of backbone amides in u-13C/15N labeled human ubiquitin by triple resonance NMR. 1996;118:12864–12865. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Loh SN, Markley JL. Hydrogen bonding in proteins as studied by amide hydrogen D/H fractionation factors: application to staphylococcal nuclease. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1029–1036. doi: 10.1021/bi00170a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Pervushin K, Wider G, Wüthrich K. Deuterium relaxation in a uniformly 15N-labeled homeodomain and its DNA complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:3842–3843. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Abragam A. The Principles of Nuclear Magnetism. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1961. [Google Scholar]

- [28].Mori S, Abeygunawardana C, Johnson MO, van Zijl PCM. Improved sensitivity of HSQC spectra of exchanging protons at short interscan delays using a new fast HSQC (FHSQC) detection scheme that avoids water saturation. J. Magn. Reson. 1995;B 108:94–98. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1995.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ireton GC, Black ME, Stoddard BL. The 1.14 Å crystal structure of yeast cytosine deaminase: evolution of nucleotide salvage enzymes and implication for genetic chemotherapy. Structure. 2003;11:961–972. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ko T-P, Lin J-J, Hu C-Y, Hsu Y-H, Wang AH-J, Liaw S-H. Crystal structure of yeast cytosine deaminase: insights into enzyme mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:19111–19117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300874200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Palmer AG, III, Rance M, Wright PE. Intramolecular motions of a zinc finger DNA-binding domain from Xfin characterized by proton-detected natural abundance 13C heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:4371–4380. [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dosset P, Hus JC, Blackledge M, Marion D. Efficient analysis of macromolecular rotational diffusion from heteronuclear relaxation data. J. Biomol. NMR. 2000;16:23–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1008305808620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kreishman-Deitrick M, Egile C, Hoyt DW, Ford JJ, Li R, Rosen MK. NMR analysis of methyl group at 100–500 kDa: model systems and Arp2/3 complex. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8579–8586. doi: 10.1021/bi034536j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bax A, Grzesiek S. Methodological advances in protein NMR. Acc. Chem. Res. 1993;26:131–138. [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sattler M, Schleucher J, Griesinger C. Heteronuclear multidimensional NMR experiments for the structure determination of proteins in solution employing pulsed field gradients. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 1999;34:93–158. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Cavanagh J, Fairbrother WJ, Palmer AG, III, Skelton NJ. Protein NMR Spectroscopy. Principles and Practice, Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Yao L, Li Y, Wu Y, Liu A, Yan H. Product release is rate-limiting in the activation of the prodrug 5-fluorocytosine by yeast cytosine deaminase. Biochemistry. 2005;44:5940–5947. doi: 10.1021/bi050095n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bax A, Ikura M, Kay LE, Torchia DA, Tschudin R. Comparison of different modes of 2-dimensional reverse-correlation NMR for the study of proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 1990;86:304–318. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Liu A, Hu W, Qamar S, Majumdar A. Sensitivity enhanced NMR spectroscopy by quenching scalar coupling mediated relaxation: application to the direct observation of hydrogen bonds in 13C/15N-labeled proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 2000;17:55–61. doi: 10.1023/a:1008340116418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Harbison GS, Jelinski LW, Stark RE, Torchia DA, Herzfeld J, Griffin RG. 15N chemical shift and 15N–13C dipolar tensors for the peptide-bond in [1-13C]glycyl[15N] glycine hydrochloride monohydrate. J. Magn. Reson. 1984;60:79–82. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Goldman M. Interference effects in the relaxation of a pair of unlike spin-1/2 nuclei. J. Magn. Reson. 1984;60:437–452. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Tjandra N, Szabo A, Bax A. Protein backbone dynamics and 15N chemical shift anisotropy from quantitative measurement of relaxation interference effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:6986–6991. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Tessari M, Vis H, Boelens R, Kaptein R, Vuister GW. Quantitative measurement of relaxation interference effects between 1HN CSA and 1H–15N dipolar interaction: correlation with secondary structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:8985–8990. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Fushman D, Cowburn D. Model-independent analysis of 15N chemical shift anisotropy from NMR relaxation data. Ubiquitin as a test example. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:7109–7110. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Pervushin K. Impact of transverse relaxation optimized spectroscopy (TROSY) on NMR as a technique in structural biology. Quart. Rev. Biophys. 2000;33:161–197. doi: 10.1017/s0033583500003619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Vasos PR, Hall JB, Kümmerle R, Fushman D. Measurement of 15N relaxation in deuterated amide groups in proteins using direct nitrogen detection. J. Biomol. NMR. 2006;36:27–36. doi: 10.1007/s10858-006-9063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Herzfeld J, Roberts JE, Griffin RG. Sideband intensities in two-dimensional NMR spectra of rotating solids. J. Chem. Phys. 1987;86:597–602. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Loria JP, Rance M, Palmer AG., III A TROSY CPMG sequence for characterizing chemical exchange in large proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 1999;15:151–155. doi: 10.1023/a:1008355631073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].de Jong AF, Kentgens APM, Veeman WS. Two-dimensional exchange NMR in rotating solids: a technique to study very slow molecular reorientations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1984;109:337–342. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Harbinson OS, Spiess HW. Two-dimensional magic-angle-spinning NMR of partially ordered systems. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1986;124:128–134. [Google Scholar]

- [51].Liu A, Li Y, Yao L, Yan H. Simultaneous NMR assignment of backbone and side chain amides in large proteins with IS-TROSY. J. Biomol. NMR. 2006;36:205–214. doi: 10.1007/s10858-006-9072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Brutscher B, Boisbouvier J, Pardi A, Marion D, Simorre JP. Improved sensitivity and resolution in 1H–13C NMR experiments of RNA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:11845–11851. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Zhu G, Kong XM, Sze KH. Gradient and sensitivity enhancement of 2D TROSY with water flip-back, 3D NOESY-TROSY and TOCSY-TROSY experiments. J. Biomol. NMR. 1999;13:77–81. doi: 10.1023/A:1008398227519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Pervushin KV, Wider G, Riek R, Wüthrich K. the 3D NOESY-[1H,15N,1H]-ZQ-TROSY NMR experiment with diagonal peak suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:9607–9612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Meissner A, Sørensen OW. Suppression of diagonal peaks in TROSY-type 1H NMR NOESY spectra of 15N-labeled proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 1999;140:499–503. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1999.1860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Mulder FAA, Skrynnikov NR, Hon B, Dahlquist FW, Kay LE. Measurement of slow (μs–ms) time scale dynamics in protein side chains by 15N relaxation dispersion NMR spectroscopy: application to Asn and Gln residues in a cavity mutant of T4 lysozyme. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:967–975. doi: 10.1021/ja003447g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.