Abstract

Mixed models are commonly used to represent longitudinal or repeated measures data. An additional complication arises when the response is censored, for example, due to limits of quantification of the assay used. While Gaussian random effects are routinely assumed, little work has characterized the consequences of misspecifying the random-effects distribution nor has a more flexible distribution been studied for censored longitudinal data. We show that, in general, maximum likelihood estimators will not be consistent when the random-effects density is misspecified, and the effect of misspecification is likely to be greatest when the true random-effects density deviates substantially from normality and the number of noncensored observations on each subject is small. We develop a mixed model framework for censored longitudinal data in which the random effects are represented by the flexible seminonparametric density and show how to obtain estimates in SAS procedure NLMIXED. Simulations show that this approach can lead to reduction in bias and increase in efficiency relative to assuming Gaussian random effects. The methods are demonstrated on data from a study of hepatitis C virus.

Keywords: Censoring, HCV, HIV, Limit of quantification, Longitudinal data, Random effects

1. INTRODUCTION

Longitudinal or repeated measures data are commonly represented by mixed effects models. A complication occurs when the response is censored for some of the observations, which often arises when assay measures are collected over time and the assay procedure is subject to limits of quantification (Hughes, 1999; Jacqmin-Gadda and others, 2000; Wu, 2002, and references therein).

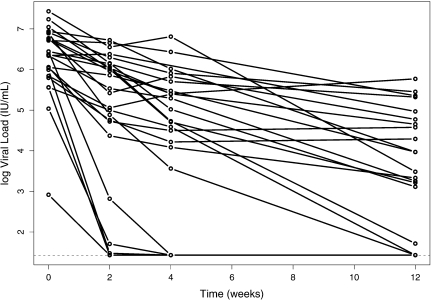

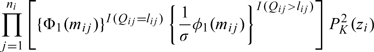

As an example, we consider data from the Individual Dosing Efficacy versus Flat Dosing to Assess Optimal Pegylated Interferon Therapy (IDEAL) study, which tracked the viral load progression of treatment-naive patients with hepatitis C (Thompson and others, 2010). One objective was to characterize the viral load decline in patients receiving standard treatment, pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin, over the first 12 weeks of treatment. Within-subjects, the trajectory of the log10 viral load over the first 12 weeks is approximately linear, but responses were censored from below at 1.431 log10 IU/mL, the lower limit of quantification of the assay used. Over the first 12 weeks, 10.5% of all observations were censored, and 35.2% were censored at week 12. The trajectories of 25 randomly selected subjects are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1.

Trajectory of log10 viral load of 25 randomly selected subjects with genotype CT from the IDEAL study. For graphical purposes, the lower limit of quantification, 1.431 log10 IU/mL, was imputed for the censored responses.

A standard analysis would impute the censored responses as the limit or half limit of quantification and then fit a mixed model for uncensored longitudinal data. However, Jacqmin-Gadda and others (2000) showed through simulation studies that such crude parameter estimators are badly biased even for modest levels of censoring. A refined analysis would postulate a likelihood that accounts for the censoring and obtain the maximum likelihood estimates. However, methods using this full-likelihood approach have all assumed Gaussian random effects and intra-subject error (Hughes, 1999; Jacqmin-Gadda and others, 2000; Wu, 2002; Vaida and Liu, 2009). While intra-subject error may be reasonably assumed to be normally distributed, the assumption of Gaussian random effects may be too restrictive in many applications. In the IDEAL study, some patients do not respond to treatment, while others show marked declines in the viral load, so the distribution of subject-specific slopes is unlikely to be approximately Gaussian.

For noncensored linear mixed-effects models, the maximum likelihood estimators for the fixed-effects and covariance components are consistent under broad regularity conditions even when the random-effects distribution is misspecified (Verbeke and Lesaffre, 1997). For nonlinear mixed-effects models, which include mixed models with censored responses and generalized linear mixed models, the maximum likelihood estimators will not, in general, be consistent if the random-effects distribution is misspecified. The effect of misspecification has been well studied in generalized linear mixed models (Neuhaus and others, 1992; Heagerty and Kurland, 2001; Agresti and others, 2004; Litière and others, 2008), but the potential effect of misspecification of the random-effects distribution when the response is censored has not been examined.

A variety of methods have been proposed to relax the Gaussian assumption for the random effects (Magder and Zeger, 1996; Verbeke and Lesaffre, 1997; Kleinman and Ibrahim, 1998; Aitkin, 1999; Zhang and Davidian, 2001; Chen and others, 2002; Lee and Thompson, 2008); however, none of these methods has been implemented for censored longitudinal data. For linear mixed models, Zhang and Davidian (2001) assumed that the random effects follow a “smooth” density that can be represented by the seminonparametric (SNP) formulation proposed by Gallant and Nychka (1987). They showed the log-likelihood can be written in a closed form leading to straightforward estimation.

We show how the SNP representation can be implemented for the random-effects density in linear mixed models when the response is potentially censored. In Section 2, we formulate the censored-response mixed model with Gaussian random effects and show that incorrectly assuming the random effects are Gaussian leads to inconsistent estimators of model parameters. In addition, we suggest general scenarios where estimation is likely to be particularly poor. In Section 3, we discuss the censored-response linear mixed model, where the random effects are assumed to follow a smooth continuous density and introduce the SNP representation. Section 4 describes how to fit the SNP model using SAS procedure NLMIXED, how to select the degree of flexility in the model, and how to choose starting values. Section 5 presents the results of several simulations. In Section 6, we illustrate the method by application to data from the IDEAL study.

2. GAUSSIAN LINEAR MIXED MODEL WITH CENSORED RESPONSE

For ease of presentation, we assume that responses are potentially left censored, but developments are easily generalized to right- or interval-censored data. Let Yij, i = 1,…,m and j = 1,…,ni be the jth response for subject i that would have been observed had there been no censoring. Consider the usual linear mixed model for longitudinal data

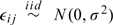

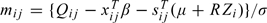

| (2.1) |

where vij = (xijT,sijT)T, δ = (βT,δT), and bi = γ + ui; β and γ are the p- and q-dimensional fixed-effects parameters associated with covariates xij and sij, respectively; ui are the q-dimensional, mean zero subject-specific random-effects vectors associated with covariates sij, independent across i; and  are the intra-subject error, which are independent of ui. We adopt the rightmost representation in (2.1) and note that the centered random effects bi can be written as bi = μ + RZi, where μ is a (q×1) vector, R is a (q×q) lower triangular matrix, and Zi is a (q×1) vector of random effects. Typically, Zi are assumed to follow a standard q-dimensional normal distribution, which implies that bi are normally distributed with mean μ = γ and covariance matrix (ui) = RRT.

are the intra-subject error, which are independent of ui. We adopt the rightmost representation in (2.1) and note that the centered random effects bi can be written as bi = μ + RZi, where μ is a (q×1) vector, R is a (q×q) lower triangular matrix, and Zi is a (q×1) vector of random effects. Typically, Zi are assumed to follow a standard q-dimensional normal distribution, which implies that bi are normally distributed with mean μ = γ and covariance matrix (ui) = RRT.

As an example, a special case of (2.1) is the linear random coefficient model with baseline covariate xi given by

| (2.2) |

where bi = (b0i,b1i)T and sij = (1,tij)T.

Due to left censoring, we observe Qij which takes the value Yij for Yij > lij and takes the value lij, the known lower limit of quantification for the jth response on subject i, otherwise. Letting r = vech(R) be the nonzero elements of R, the parameters of interest are θ = (βT,μT,rT,σ2)T, and the likelihood assuming Gaussian random effects is

|

(2.3) |

where  , Q is the vector of all responses observed, and φn(·) and Φn(·) are the standard n-dimensional normal density and distribution.

, Q is the vector of all responses observed, and φn(·) and Φn(·) are the standard n-dimensional normal density and distribution.

Alternatively, we can express (2.1) as Yi = Viδ + Siui + ϵi, where Vi{ni×(p + q)} and Si(ni×q) are the matrices with rows vijT and sijT, respectively, and Yi = (Yi1,…,Yini)T and similarly for ϵi, li, and Qi.

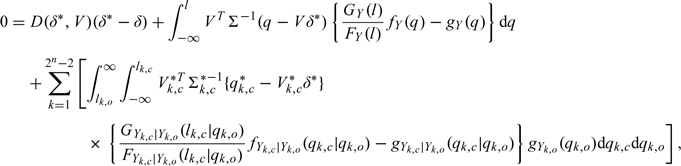

To simplify the following argument, we assume that the design matrix is fixed, Vi = V and ni = n for i = 1,…,m and also suppress the index i throughout. To express (2.3) using vector notation, let fY(y;θ) and FY(y;θ) be the multivariate normal density and distribution, respectively, with mean Vδ and covariance matrix Σ = SRRTST + σ2In. Define fY1|Y2(y1|y2;θ) and FY1|Y2(y1|y2;θ) to be the conditional multivariate normal density and distribution, respectively, of the vector Y1 given the vector Y2. There are 2n − 2 patterns of censoring/noncensoring that could be observed for an individual with at least one censored and one noncensored observation. Index each of these 2n − 2 distinct censoring patterns by k. Let Yk,o (Yk,c, respectively) be the random vector containing elements of Y that would be observed (censored) under censoring pattern k. If the kth pattern were observed for a particular subject, then the likelihood contribution from that subject assuming normal random effects is given by FYk,c|Yk,o(lk,c|Qk,o;θ)fYk,o(Qk,o;θ), where Qk,o is the vector of noncensored responses and lk,c (lk,o, respectively) is the limit of quantification for the censored observations (noncensored observations) under censoring pattern k. The likelihood contribution from one subject can now be written as

|

If the random-effects distribution is incorrectly specified, the maximum likelihood estimator  will converge to value of θ that solves E{∂/∂θlogℒ(θ;Q)} = 0, where the expectation is taken with respect to the true random-effects distribution. Assuming that the covariance components are known and using a first-order Taylor series expansion, we show in the supplementary material (available at Biostatistics online) that

will converge to value of θ that solves E{∂/∂θlogℒ(θ;Q)} = 0, where the expectation is taken with respect to the true random-effects distribution. Assuming that the covariance components are known and using a first-order Taylor series expansion, we show in the supplementary material (available at Biostatistics online) that  will converge to the value of δ that solves

will converge to the value of δ that solves

|

(2.4) |

where gY(q;δ*) and GY(q;δ*) are the true marginal density and distribution, respectively, of Y; all densities in (2.4) are evaluated at δ*, the true parameter value; and D(δ*,V), Qk,c*, Vk,c*, and Σk,c* are given in the supplementary material available at Biostatistics online.

While complex, the approximation reveals important insights on the asymptotic bias when the random effects are incorrectly specified. In the likely case that the random-effects distribution is misspecified, the bias is driven by the difference in the true conditional distribution of the censored response given the noncensored response (i.e. gYk,c|Yk,o(qk,c|qk,o)) and the same conditional distribution induced by the Gaussian random effects (i.e. fYk,c|Yk,o(qk,c|qk,o)), weighted by the likelihood of the noncensored response (i.e. gYk,o(qk,o)). Practically, this suggests that small deviations from normality will lead to only slight asymptotic bias. If we have correctly specified the intra-subject error distribution, then gYk,c|Yk,o(yk,c|yk,o) will be approximately normal if the dimension of Yk,o is large regardless of the true random-effects density. Thus, if there is a large probability of observing many noncensored observations on each subject, then the asymptotic bias is likely to be slight. This suggests that the overall percentage of censored responses is immaterial in determining the asymptotic bias. Instead, the absolute number of noncensored responses for each subject is critical.

3. SEMIPARAMETRIC LINEAR MIXED MODEL WITH CENSORED RESPONSE

We offer a summary of semiparametric linear mixed models and refer the reader to Zhang and Davidian (2001) for a complete description. We now assume that the distribution of Zi belongs to the smooth class of continuous densities described by Gallant and Nychka (1987). This class is sufficiently flexible to include skewed, thick- and thin-tailed, and multimodal distributions but does not include densities with jumps, kinks, or oscillations. These densities can be represented as an infinite series but can be approximated by a truncated series. The densities that are part of the truncated series are referred to as seminonparametric (SNP).

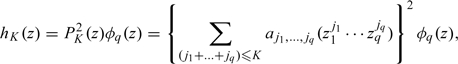

We thus assume that the density of Zi can be approximated by the SNP representation with degree of truncation K given by

|

(3.1) |

where jl ≥ 0 for l = 1,…,q and K is the order of the polynomial PK(z). For example, with K = 2 and q = 2, PK(z) = a00 + a10z1 + a01z2 + a20z12 + a11z1z2 + a02z22. When K = 0, we show below that a0,…,0 must equal 1, and the density of Zi is a standard q-dimensional normal. K controls the degree of flexibility of the density hK(z); we discuss in Section 4 how to select K.

The coefficients aj1,…,jq must be chosen so that hK(z) integrates to one. The constraint ∫hk(z)dz = 1 is equivalent to imposing E{PK2(U)} = 1, where U follows a standard q-dimensional normal distribution (Zhang and Davidian, 2001). Let a be the d-dimensional vector of coefficients for the polynomial PK(z) and let j1,…,jq be the subscripts corresponding to the jth element. Then the above constraint can be rewritten as E{PK2(U)} = aTAa = 1, where A is the matrix with (j,k) element equal to {E(U1j1 + k1)⋯E(U1jq + kq)} and U1 is distributed as a standard normal.

Rather than impose a constraint on a, we may rewrite the (d×1) vector a as a function of d − 1 parameters. Because A must be positive definite, there exists a matrix B such that A = B2. If we let c = Ba, then aTAa = 1 implies cTc = 1. As c and − c will result in the same density hK(z), c = (c1,…,cd)T must lie in the half-unit sphere of ℛd. Therefore, we can express c in terms of a polar coordinate transformation, where c1 = sin(ξ1), c2 = cos(ξ1)sin(ξ2),…, cd − 1 = cos(ξ1)…cos(ξd − 2)sin(ξd − 1),cd = cos(ξ1)…cos(ξd − 1), − π/2 ≤ ξj ≤ π/2 for j = 1,…,d − 1, and ξ = (ξ1,…,ξd − 1)T. The vector a can be written as B − 1c, which only involves d − 1 parameters. The parameters of interest are now θSNPK = (βT,μT,rT,σ2,ξT)T, which includes an additional d − 1 parameters compared to when normality is assumed.

Note that the SNP density does not impose E(Zi) = 0, so that E(bi) = γ = μ + R{ E (Zi)} and Var(bi) = R{Var(Zi)}RT. The moments of Zi are linear combinations of the moments of a standard normal density, which can be found using recursion formulas.

4. ESTIMATION USING SAS NLMIXED

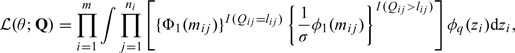

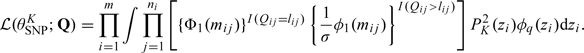

In the case where there is no censoring of the response variable, the log-likelihood assuming the SNP representation of the random effects can be expressed in a closed form (Zhang and Davidian, 2001). Censoring necessitates numerical integration. For a fixed K, the likelihood of θSNPK is given by

|

(4.1) |

For each observation i, this requires evaluation of a q-dimensional integral, which, in practice, would likely only have dimension 1 or 2. In contrast, we could integrate over the marginal density of Yi for each censored observation. However, the dimension of that integral would equal the number of censored observations for subject i, which could be quite large and computationally intractable.

The SAS procedure NLMIXED has been developed to obtain maximum likelihood estimates for mixed models with Gaussian random effects. Except when K = 0, the SNP random-effects density will not be normally distributed. However, if we consider

|

(4.2) |

to be the likelihood for Qij conditioned on the random effects, then the random effects Zi can be thought to follow a standard q-dimensional normal distribution (Liu and Yu, 2008). Example code to implement SNP for left-censored mixed models is given in the supplementary material (available at Biostatistics online). In practice, given that (4.2) is highly nonlinear, we have found optimization routines within NLMIXED to obtain the empirical Bayes estimates of Zi, required for the default adaptive Gaussian quadrature used to evaluate the integrals to be unstable and computationally intractable for q ≥ 2. To approximate the integral in (4.1), we recommend using nonadaptive Gaussian quadrature with quadrature points centered at the empirical Bayes estimates of bi from assuming Gaussian random effects. Among the optimization routines available in NLMIXED, dual-quasi Newton optimization works well. The inverse Hessian matrix may be used to obtain standard errors for the parameter estimates and is computed as part of the standard output in NLMIXED.

The preceding discussion assumes a fixed K. We treat K as a tuning parameter and select K by visually comparing the estimated densities and computing information criteria evaluated at the estimates,  , of

, of  from model fits for different values of K (Zhang and Davidian, 2001). The information criteria are of the form

from model fits for different values of K (Zhang and Davidian, 2001). The information criteria are of the form  where p is the number of parameters in the model. For the Akaike information criterion (AIC), C(m) = 2; Hannan–Quinn information criterion (HQIC), C(m) = 2loglogm; and Bayesian information criterion (BIC), C(m) = logm. Because the HQIC will select a model that is of intermediate complexity compared to those chosen by AIC and BIC, this criterion is often preferred (Davidian and Gallant, 1993). Prior research has shown that K need not be greater than 2 to capture many complex densities (Davidian and Gallant, 1993; Zhang and Davidian, 2001; Chen and others, 2002).

where p is the number of parameters in the model. For the Akaike information criterion (AIC), C(m) = 2; Hannan–Quinn information criterion (HQIC), C(m) = 2loglogm; and Bayesian information criterion (BIC), C(m) = logm. Because the HQIC will select a model that is of intermediate complexity compared to those chosen by AIC and BIC, this criterion is often preferred (Davidian and Gallant, 1993). Prior research has shown that K need not be greater than 2 to capture many complex densities (Davidian and Gallant, 1993; Zhang and Davidian, 2001; Chen and others, 2002).

Optimization for SNP can be highly dependent on the starting values used for θSNPK and especially for ξ. We suggest the following approach advocated by Doehler and Davidian (2008). Initial estimates of β, E(bi), v a r ( b i), and σ2 should be obtained, perhaps by fitting a mixed model assuming Gaussian random effects. The log-likelihood (4.1) can then be evaluated over a grid of ξ with starting values for β and σ2 set to the initial estimates and starting values for μ and r selected to give the same value for E(bi) and v a r ( b i) as the initial estimates. The sets of starting values that yield local maxima among all the grid points can then be used for optimization.

5. SIMULATION

We conducted a variety of simulation studies both to assess the impact of erroneously assuming Gaussian random effects and to gauge the ability of SNP to represent a broad range of random-effects distributions. We report on a subset of these with q = 2 here; results of additional simulations are included in the supplementary material (available at Biostatistics online).

The first part of the simulation study examined the effect of misspecification of the random-effects distribution on estimation and inference of model parameters. We considered (2.2) where xi is equal to 0 or 1 with equal probability, ϵijiid∼N(0,σ2), and ti = (ti1,…,ti5)T = (0,1,2,3,4)T≡tA for all i = 1,…,m. For all simulations, β = 0.5, σ2 = 0.25, and (b0i,b1i)T were generated from distributions that were shifted and scaled so that E(b0i) = 5.75, E(b1i) = − 0.60, v a r ( b 0 i) = 0.36, v a r ( b 1 i) = 0.9025, and c o v ( b 0 i, b 1i) = − 0.228.

The random effects, bi were drawn from 1 of 4 shifted and scaled distributions: (1) bivariate normal; (2) a bivariate t5 distribution; (3) a 70–30 mixture of normal densities with mean components (5.6, − 0.1071)T (70% component) and (6.1, − 1.75)T, which gives a skewed marginal density for b1i; and (4) a 70–30 mixture of normal densities with mean components (5.6, − 0.03)T (70% component) and (6.1, − 1.93)T, which produces a bimodal marginal density for b1i. For (3) and (4), the covariance matrices of the components were equal to each other. For each of the 4 distributions, 500 Monte Carlo simulations were generated with 500 subjects each. Here, we report the results for censoring level lij≡4 for all subjects and time points.

The models were fit using SAS procedure NLMIXED assuming Gaussian random effects. The likelihood (2.3) was approximated using adaptive Gaussian quadrature with the number of quadrature points selected adaptively to achieve a tolerance of 10 − 4. Dual-quasi Newton was used for optimization with the true values used as starting values.

Within each of the simulation scenarios, nearly all subjects had at least one noncensored measurement, and approximately 90% had at least 2 noncensored observations. With the exception of the data generated from the bimodal random-effects density (4) where 42.4% of subjects had at least one censored observation, a slight majority in each of the other scenarios had at least one censored observation. A complete description of the censoring pattern is given in the supplementary material (available at Biostatistics online).

The results are given in Table 1. When the random effects are correctly specified, parameter estimators are unbiased, and the coverage probabilities attain their stated level of confidence. When the random effects have heavy tails (t5 distribution), parameter estimators are still unbiased although coverage probabilities for the covariance components do degrade slightly. Equation (2.4) suggests that the asymptotic bias in this scenario would be slight. When the random slope is slightly skewed, parameter estimators are biased, especially for E(b1i) (6.0%) and v a r ( b 1 i) ( − 10.0%). Coverage probabilities for these parameters in particular are far from nominal. This illustrates that even slight departures from normality can lead to erroneous inference when the number of noncensored observations for each subject is small. In the case of severe misspecification with bimodal random slopes, the bias of all the parameter estimators increases in comparison to that under skewed random effects; the bias in the estimators for E(b1i) and v a r ( b 1 i) is substantial (13.0% and − 18.9%, respectively), and coverage probabilities for these parameters are poor.

Table 1.

Simulation results when Gaussian random effects were assumed for all models regardless of the true distribution of the random effects. The simulation included 500 data sets with 500 subjects each

| Distribution | (b0i) | (b1i) | β0 | (b0i) | (b0i, b1i) | (b1i) | |

| Truth | 5.750 | – 0.600 | 0.500 | 0.360 | – 0.228 | 0.903 | |

| MC Avg | Normal | 5.749 | – 0.604 | 0.504 | 0.360 | – 0.230 | 0.907 |

| t5 | 5.752 | – 0.599 | 0.498 | 0.349 | – 0.224 | 0.859 | |

| Skewed | 5.736 | – 0.564 | 0.496 | 0.349 | – 0.202 | 0.813 | |

| Bimodal | 5.718 | – 0.522 | 0.494 | 0.341 | – 0.180 | 0.732 | |

| MC SD | Normal | 0.043 | 0.047 | 0.060 | 0.037 | 0.037 | 0.074 |

| t5 | 0.042 | 0.042 | 0.057 | 0.040 | 0.041 | 0.082 | |

| Skewed | 0.045 | 0.046 | 0.058 | 0.035 | 0.036 | 0.065 | |

| Bimodal | 0.045 | 0.048 | 0.058 | 0.035 | 0.036 | 0.067 | |

| Avg SE | Normal | 0.044 | 0.046 | 0.059 | 0.035 | 0.036 | 0.069 |

| t5 | 0.044 | 0.044 | 0.058 | 0.034 | 0.035 | 0.065 | |

| Skewed | 0.044 | 0.043 | 0.059 | 0.034 | 0.035 | 0.065 | |

| Bimodal | 0.044 | 0.042 | 0.059 | 0.034 | 0.033 | 0.062 | |

| CP | Normal | 0.956 | 0.950 | 0.956 | 0.932 | 0.950 | 0.938 |

| t5 | 0.952 | 0.962 | 0.949 | 0.869 | 0.905 | 0.786 | |

| Skewed | 0.928 | 0.832 | 0.960 | 0.920 | 0.852 | 0.678 | |

| Bimodal | 0.878 | 0.532 | 0.956 | 0.896 | 0.662 | 0.268 |

MC Avg, Monte Carlo average of the parameter estimates; MC SD, Monte Carlo standard deviation of the parameter estimates; Avg SE, average of the standard error estimates; CP, Monte Carlo coverage probability of the 95% Wald-type confidence intervals.

We also examined the effect of adding design points where there was unlikely to be any censoring and where censoring was likely. We generated 500 data sets with bimodal random effects, where ti = (0,1,2,3,3.5,4,4.5)T≡tB and ti = ( − 2, − 1,0,1,2,3,4)T≡tC for all subjects. With measurements at tij = − 2 and tij = − 1, 99.9% and 90.5% of subjects had at least 3 and 4 noncensored measurements, respectively. Adding measurements at tij = 3.5 and tij = 4.5 increased the overall percentage of censored observations to 25.5% from 21.8%.

Simulation results with bimodal random effects and taking tito be each oftA, tB, and tC are shown in Table 2. When there are more design points where censored observations are unlikely, bias is mitigated substantially and coverage probabilities improve, which is consistent with the asymptotic results in Section 2. Conversely, increasing the number of design points where censoring is likely has little effect on parameter estimation, illustrating that the overall censoring level has little to do with the bias.

Table 2.

Simulation results when Gaussian random effects were assumed for the bimodal random effects but ti in (2.2) was varied. The simulation included 500 data sets with 500 subjects each

| Time points | (b0i) | (b1i) | β0 | (b0i) | (b0i, b1i) | (b1i) | |

| Truth | 5.750 | – 0.600 | 0.500 | 0.360 | – 0.228 | 0.903 | |

| MC Avg | tA | 5.718 | – 0.522 | 0.494 | 0.341 | – 0.180 | 0.732 |

| tB | 5.715 | – 0.520 | 0.496 | 0.337 | – 0.175 | 0.722 | |

| tC | 5.757 | – 0.590 | 0.500 | 0.360 | – 0.234 | 0.886 | |

| MC SD | tA | 0.045 | 0.048 | 0.058 | 0.035 | 0.036 | 0.067 |

| tB | 0.046 | 0.048 | 0.059 | 0.033 | 0.034 | 0.066 | |

| tC | 0.040 | 0.044 | 0.054 | 0.027 | 0.029 | 0.049 | |

| Avg SE | tA | 0.044 | 0.042 | 0.059 | 0.034 | 0.033 | 0.062 |

| tB | 0.043 | 0.041 | 0.058 | 0.032 | 0.032 | 0.061 | |

| tC | 0.039 | 0.043 | 0.053 | 0.026 | 0.030 | 0.058 | |

| CP | tA | 0.878 | 0.532 | 0.956 | 0.896 | 0.662 | 0.268 |

| tB | 0.864 | 0.474 | 0.950 | 0.864 | 0.586 | 0.212 | |

| tC | 0.944 | 0.930 | 0.948 | 0.938 | 0.962 | 0.960 |

tA = (0, 1, 2, 3, 4)T; tB = (0, 1, 2, 3, 3.5, 4, 4.5)T; tC = (– 2, – 1, 0, 1, 2, 3, 4)T; MC Avg, Monte Carlo average of the parameter estimates; MC SD, Monte Carlo standard deviation of the parameter estimates; Avg SE, average of the standard error estimates; CP, Monte Carlo coverage probability of the 95% Wald-type confidence intervals.

We also conducted simulation studies of the performance of SNP density estimation for censored longitudinal data analysis. We considered the same simulation scenarios as above except for the t5 random-effects distribution, as assuming Gaussian random effects did not adversely affect inference. To obtain estimates of parameters with SNP random effects, we again used SAS procedure NLMIXED. Models were fit for K = 0,1, and 2, and K was chosen using HQIC. The likelihood (4.1) was approximated using Gaussian quadrature with quadrature points centered at the empirical Bayes estimates of bi derived from assuming Gaussian random effects and with the number of quadrature points selected with a stated tolerance of 10 − 4. Dual-quasi Newton was used for optimization. 500 Monte Carlo data sets were generated for each scenario. To obtain starting values, the log-likelihood was evaluated over a grid of ξ of 50 points for K = 1 and 150 points for K = 2 with starting values for β and σ2 set to the true values and for μ and r set to the values that would give the true values for E(bi) and v a r ( b i).

The results when K was selected by HQIC are shown in Table 3. When the random effects are normally distributed, HQIC selects K = 0 for 94.8% of the data sets. However, when the random-effects density was skewed and bimodal, K = 0 was selected only 0.2% and 0.0% of the time, respectively, and K = 2 was selected for 95.2% and 36.4% of the data sets, respectively. This illustrates that even with a modest sample size and loss of information due to censoring, the method is able to detect slight departures from normality while not over-fitting models where the true random-effects density is Gaussian. A complete table on the proportion of data sets that selected K = 0, 1, and 2 by information criterion is given in the supplementary material (available at Biostatistics online).

Table 3.

Simulation results when SNP was used to estimate the random effects. Models with K = 0, K = 1, and K = 2 were fit and K was selected using the HQIC. The simulation included 500 data sets with 500 subjects each

| Distribution | (b0i) | (b1i) | 0 | (b0i) | (b0i, b1i) | (b1i) | |

| Truth | 5.750 | – 0.600 | 0.500 | 0.360 | – 0.228 | 0.903 | |

| MC Avg | Normal | 5.749 | – 0.603 | 0.504 | 0.358 | – 0.229 | 0.905 |

| Skewed | 5.750 | – 0.598 | 0.496 | 0.358 | – 0.227 | 0.900 | |

| Bimodal | 5.747 | – 0.590 | 0.496 | 0.360 | – 0.222 | 0.878 | |

| MC SD | Normal | 0.043 | 0.047 | 0.060 | 0.040 | 0.038 | 0.077 |

| Skewed | 0.046 | 0.050 | 0.060 | 0.044 | 0.041 | 0.090 | |

| Bimodal | 0.045 | 0.048 | 0.058 | 0.037 | 0.039 | 0.080 | |

| Avg SE | Normal | 0.044 | 0.045 | 0.058 | 0.035 | 0.036 | 0.069 |

| Skewed | 0.043 | 0.046 | 0.057 | 0.035 | 0.037 | 0.072 | |

| Bimodal | 0.044 | 0.045 | 0.058 | 0.034 | 0.035 | 0.062 | |

| CP | Normal | 0.950 | 0.952 | 0.948 | 0.916 | 0.936 | 0.932 |

| Skewed | 0.930 | 0.934 | 0.940 | 0.904 | 0.932 | 0.908 | |

| Bimodal | 0.944 | 0.920 | 0.952 | 0.932 | 0.916 | 0.860 | |

| Ratio MSE | Normal | 0.999 | 1.004 | 0.999 | 0.843 | 0.949 | 0.917 |

| Skewed | 1.080 | 1.372 | 0.960 | 0.688 | 1.160 | 1.532 | |

| Bimodal | 1.493 | 3.440 | 1.006 | 1.149 | 2.285 | 4.801 |

MC Avg, Monte Carlo average of the parameter estimates; MC SD, Monte Carlo standard deviation of the parameter estimates; Avg SE, average of the standard error estimates; Ratio MSE, ratio of the Monte Carlo mean square error between K = 0 and K selected by the HQIC.

The SNP estimators when the random effects are not normally distributed are less biased than the estimators when Gaussian random effects were assumed. When the random effects were skewed, the bias for E(b1i) and v a r ( b 1 i) is reduced to 0.5% and − 0.3%, respectively, which leads to large efficiency gains (Table 3). The coverage probabilities for these parameters improve substantially although for bimodal random effects are still below the stated level. Because K = 0 is selected so frequently when the random effects are Gaussian, there is little loss in efficiency from considering a more flexible class of random effects. Estimated contour and marginal density plots of the random effects from assuming that the random effects follow the SNP density is provided in the supplementary material (available at Biostatistics online).

6. APPLICATION

We now illustrate the proposed methods using data from 811 subjects in the IDEAL study with the CT genotype at polymorphic site upstream of interleukin (IL) 28B which is associated with virologic response (Thompson and others, 2010).

Subjects had viral load measurements taken at baseline and at 2, 4, and 12 weeks after treatment began, some of which were censored at the lower limit of quantification of 1.431 log10 IU/mL. As shown in Figure 1, the viral load change over the first 12 weeks within subject can be well approximated by a linear trajectory, and the measurement error and biological fluctuations at each time point can be assumed reasonably to be independent and Gaussian. However, standard therapy is not effective for all subjects, so the assumption that the subject-specific slopes are normally distributed is questionable.

Based on these observations, we consider the semiparametric model

| (6.1) |

where Yij is the log10 viral load for patient i at the jth time, tij is the time in weeks since starting treatment, xij is null, sij = (1,tij)T, ϵijiid∼N(0,σ2), and bi = (b0i,b1i)T is the vector of subject-specific intercept and slope, which we assume can be written as bi = μ + RZi with Zi = (Z0i,Z1i)T, μ = (μ1,μ2)T, and R a (2×2) lower triangular matrix. We assume that Zi follows the density (3.1) for the K described below. We do not observe Yij but instead observe Qij with lij≡1.431.

All patients included in this analysis have noncensored baseline measurements, and greater than 94% of measurements taken at 2 and 4 weeks after starting treatment are uncensored. Still, 12.8% of patients only have 1 or 2 noncensored measurements. At week 12, 35.2% of subjects' responses are censored.

The fit statistics and relevant parameter estimates from fitting model (6.1) with K = 0, K = 1, and K = 2 appear in Table 4; additional parameter estimates are given in the supplementary material (available at Biostatistics online). While most of the parameter estimates are only altered marginally as K increases, the estimate for E(b1i), the average weekly log viral load decline, changes substantially. When K = 1 and K = 2, the estimate is more than one standard error away from the estimate when K = 0.

Table 4.

Information criteria and parameter estimates from fitting model (6.1) concerning the IDEAL study with K = 0, K = 1, and K = 2

|

K = 0 |

K = 1 |

K = 2 |

||||

| AIC | 7152.4 | 6952.5 | 6836.0 | |||

| HQIC | 7162.2 | 6978.3 | 6855.8 | |||

| BIC | 7180.6 | 6990.1 | 6887.7 | |||

| Estimate | Standard error | Estimate | Sandard error | Estimate | Standard error | |

| (b0i) | 6.171 | 0.020 | 6.174 | 0.020 | 6.186 | 0.020 |

| (b1i) | – 0.379 | 0.012 | – 0.380 | 0.013 | – 0.393 | 0.014 |

| var(b0i) | 0.212 | 0.017 | 0.204 | 0.017 | 0.200 | 0.017 |

| cov(b0i, b1i) | 0.085 | 0.008 | 0.080 | 0.008 | 0.080 | 0.009 |

| var(b1i) | 0.108 | 0.007 | 0.116 | 0.008 | .135 | 0.011 |

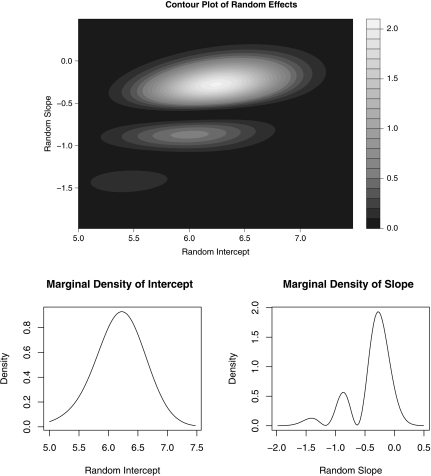

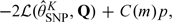

Each of the information criteria preferred K = 2, so we present the density estimates from that model in Figure 2. The contour plot for the bivariate random effects shows the presence of 2 or possibly 3 modes. SNP density estimation results in a spurious mode to capture mass in what is actually a long tail, so one should be cautious about over interpreting this third mode. The marginal density estimates show a large departure from normality for the subject-specific slope, confirming our prior hypothesis, but little departure from normality in the baseline log10 viral load. The majority of patients with the CT genotype experience very modest weekly viral load changes around –0.25 log10 IU/mL/week. However, the remaining patients experience greater viral load decline with the mode at approximately –0.85 log10 IU/mL/week.

Fig. 2.

Contour plot of the bivariate density estimate and marginal density estimates for the subject-specific intercepts and slopes with K = 2 from model (6.8) concerning the IDEAL study.

One possible clinical explanation for the nonnormal random slopes is that some patients respond to standard therapy while the majority with the CT genotype do not show substantial improvement. The IL28B genotype has been shown to be a strong predictor of virological response for patients with hepatitis C undergoing standard therapy. However, the analysis here suggests that, even within this genotype, there are responders and nonresponders, and more research is required to determine why patients respond to therapy. This example illustrates that fitting a flexible model for the random effects when the response is censored cannot only substantially alter the estimates of clinically relevant parameters like E(b1i) but can also lead to a fuller understanding of the underlying process. Given the multi modality of the subject-specific slopes, some would even question if E(b1i) is a useful parameter with which to characterize the population.

7. DISCUSSION

We have shown how the SNP random-effects density can be extended to linear mixed models with a censored response. The implementation within SAS and the example code given in the supplementary material (available at Biostatistics online) allow the method to be applied easily in practice. If one is interested purely in inference for the fixed-effects parameters, we have shown that the asymptotic bias from erroneously assuming Gaussian random effects is likely to be greatest when the true random-effects distribution deviates from normality and the probability of observing a small number of noncensored observations is not trivially small. That is, the overall level of censoring is unimportant, but rather the absolute number of noncensored responses for each subject is relevant. Simulations show that the deviation from normality need not be substantial to affect inference. Since there is little efficiency loss from using the SNP density when the random effects are Gaussian, we recommend using the SNP density for censored longitudinal data when the number of noncensored observations is small to avoid erroneous inference. More specifically, we suggest fitting SNP models for several K to determine if the random-effects density deviates from normality. Visual inspection of the estimated densities for each K > 0 as well as information criteria can be used to assess if the random-effects density is non normal. When the random-effects distribution deviates from normality, the information criteria rarely select K = 0 even with modest sample sizes, indicating the method's ability to detect nonnormal distributions. In addition to improved inference, one gains insight into the data generating process if a flexible random-effects model is used.

Within the economics literature, there has been substantial work on developing tests to determine if the error distribution is Gaussian in censored regression models with independent responses. Future work could extend those tests to random-effects densities.

We have focused on linear mixed models with a censored response. However, nonlinear trajectories can be easily incorporated in procedure NLMIXED, so the methods could easily be transferred to a nonlinear mixed model with censored response. Future work could examine the benefit of assuming a flexible random-effects distribution in this setting.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at http://biostatistics.oxfordjournals.org.

FUNDING

National Institutes of Health (R01CA085848, R01CA051962, R37AI031789, and P01CA142538).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Merck for approving the use of the IDEAL study and Oliver Schabenberger for helpful discussions on procedure NLMIXED. Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- Agresti A, Caffo B, Ohman-Strickland P. Examples in which misspecification of a random effects distribution reduces efficiency, and possible remedies. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 2004;47:639–653. [Google Scholar]

- Aitkin M. A general maximum likelihood analysis of variance components in generalized linear models. Biometrics. 1999;55:117–128. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Zhang D, Davidian M. A Monte Carlo EM algorithm for generalized linear mixed models with flexible random effects distribution. Biostatistics. 2002;3:347–360. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/3.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidian M, Gallant AR. The nonlinear mixed effects model with a smooth random effects density. Biometrika. 1993;80:475–488. [Google Scholar]

- Doehler K, Davidian M. Smooth inference for survival functions with arbitrarily censored data. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27:5421–5439. doi: 10.1002/sim.3368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallant AR, Nychka DW. Semi-nonparametric maximum likelihood estimation. Econometrica. 1987;55:363–390. [Google Scholar]

- Heagerty PJ, Kurland BF. Misspecified maximum likelihood estimates and generalised linear mixed models. Biometrika. 2001;88:973–985. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes JP. Mixed effects models with censored data with application to HIV RNA levels. Biometrics. 1999;55:625–629. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacqmin-Gadda H, Thiébaut R, Chêne G, Commenges D. Analysis of left-censored longitudinal data with application to viral load in HIV infection. Biostatistics. 2000;1:355–368. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/1.4.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman KP, Ibrahim JG. A semiparametric Bayesian approach to the random effects model. Biometrics. 1998;54:921–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KJ, Thompson SG. Flexible parametric models for random-effects distributions. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27:418–434. doi: 10.1002/sim.2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Litière S, Alonso A, Molenberghs G. The impact of a misspecified random-effects distribution on the estimation and the performance of inferential procedures in generalized linear mixed models. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27:3125–3144. doi: 10.1002/sim.3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Yu Z. A likelihood reformulation method in non-normal random effects models. Statistics in Medicine. 2008;27:3105–3124. doi: 10.1002/sim.3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magder LS, Zeger SL. A smooth nonparametric estimate of a mixing distribution using mixtures of Gaussians. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1996;91:1141–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Neuhaus JM, Hauck WW, Kalbfleisch JD. The effects of mixture distribution misspecification when fitting mixed-effects logistic models. Biometrika. 1992;79:755–762. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson AJ, Muir AJ, Sulkowski MS, Ge D, Fellay J, Shianna KV, Urban T, Afdhal NH, Jacobson IM, Esteban R others. Interleukin-28b polymorphism improves viral kinetics and is the strongest pretreatment predictor of sustained virologic response in genotype 1 hepatitis C virus. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:120–129. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaida F, Liu L. Fast implementation for normal mixed effects models with censored response. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2009;18:797–817. doi: 10.1198/jcgs.2009.07130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke G, Lesaffre E. The effect of misspecifying the random-effects distribution in linear mixed models for longitudinal data. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 1997;23:541–556. [Google Scholar]

- Wu L. A joint model for nonlinear mixed-effects models with censoring and covariates measured with error, with application to AIDS studies. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2002;97:955–964. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Davidian M. Linear mixed models with flexible distributions of random effects for longitudinal data. Biometrics. 2001;57:795–802. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00795.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.