Abstract

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are pattern recognition receptors that recognize specific molecular patterns present in molecules that are broadly shared by pathogens, but are structurally distinct from host molecules. The TLR7-agonistic imidazoquinolines are of interest as vaccine adjuvants given their ability to induce pronounced Th1-skewed humoral responses. Minor modifications on the imidazoquinoline scaffold result in TLR7-antagonistic compounds which may be of value in addressing innate immune activation-driven immune exhaustion observed in HIV. We describe the syntheses and evaluation of TLR7 and TLR8 modulatory activities of dimeric constructs of imidazoquinoline linked at the C2, C4, C8, and N1-aryl positions. Dimers linked at the C4, C8 and N1-aryl positions were agonistic at TLR7; only the N1-aryl dimer with a 12-carbon linker was dual TLR7/8 agonistic. Dimers linked at C2 position showed antagonistic activities at TLR7 and TLR8; the C2 dimer with a propylene spacer was maximally antagonistic at both TLR7 and TLR8.

Keywords: Toll-like receptor, TLR7, TLR8, Imidazoquinoline, Interferon, Cytokines, Chemokines

Introduction

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are pattern recognition receptors that recognize specific molecular patterns present in molecules that are broadly shared by pathogens, but are structurally distinct from host molecules.1;2 There are 10 TLRs in the human genome.2 The ligands for these receptors are highly conserved microbial molecules such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) (recognized by TLR4), lipopeptides (TLR2 in combination with TLR1 or TLR6), flagellin (TLR5), single stranded RNA (TLR7 and TLR8), double stranded RNA (TLR3), CpG motif-containing DNA (recognized by TLR9), and profilin present on uropathogenic bacteria (TLR 11).3;4 TLR1, -2, -4, -5, and -6 respond to extracellular stimuli, while TLR3, -7, -8 and -9 respond to intracytoplasmic pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), being associated with the endolysosomal compartment.2

We have earlier explored structure activity-relationships in TLR2- and TLR7-active ligands5;6 toward exploiting them as potential vaccine adjuvants;7;8 the TLR7-agonistic imidazoquinolines are of particular interest in that they induce pronounced Th1-skewed humoral responses in animal models.9 Of equal interest is our finding that relatively minor modifications on the imidazoquinoline scaffold result in TLR7-antagonistic compounds10;11 which may be of value in addressing the relentless innate immune activation-driven immune exhaustion observed in HIV.12–14

Several TLRs are thought to signal via ligand-induced dimerization,15 as evident in the crystal structures of TLR216;17 and TLR3.18 It is not yet understood, however, how TLR7 and TLR8 whose endogenous ligands are single-stranded viral RNA (ssRNA), recognize and transduce signals upon engagement by small, non-polymeric molecules such as the imidazoquinolines19;20 and the oxoadenines.21;22 We were not only desirous of examining the effect of variously configured, pre-organized dimeric constructs of the imidazoquinolines on TLR7 and TLR8 in our continuing efforts to identify efficacious and safe vaccine adjuvants, but also motivated in the hope that we may, by design or accident, discover small-molecule modulators of TLR3. It may be noted that although TLR3, like TLR7, is an attractive target for adjuvant design and development, 23–28 polyriboinosinic:polyribocytidylic acid, poly(I:C), is presently the only available synthetic TLR3 agonist. 29 No small molecule agonists for TLR3 have been described to date; however, benzothiophene antagonists of TLR3 have been reported recently.30

We describe in the paper the syntheses and evaluation of TLR7, -8, and -3 modulatory activities of dimeric constructs of imidazoquinoline linked at the C2, C4, C8, and N1-aryl positions. Dimers linked at the C4, C8 and N1-aryl positions were agonistic at TLR7; only the N1-aryl dimer with a 12-carbon linker was found to be dual TLR7/8 agonistic. The imidazoquinoline dimers linked at C2 position showed antagonistic activities at TLR7 and TLR8; the C2 dimer with a 3-carbon spacer was found to be maximally antagonistic at both TLR7 and TLR8, and its activities were preserved in secondary screens employing human blood.

Results and Discussion

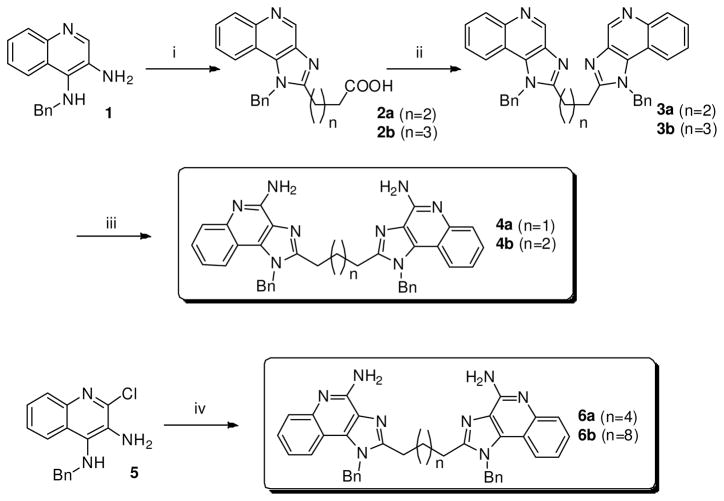

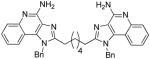

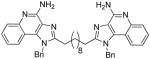

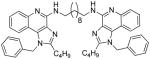

The majority of TLRs signal via homo- or hetero-dimerization,15 and it was therefore of interest to examine dimeric constructs with differing geometries. The first series of dimeric imidazoquinolines were linked at the C2 position and their syntheses necessitated two different routes. Whereas the hexamethylene- and decamethylene-bridged compounds 6a and 6b could be conveniently obtained from 5 by a direct, one-step, bis-amidation using the corresponding dicarboxylic acid chlorides and cyclization (Scheme 1), the shorter chain analogues were not amenable to this method because of intramolecular cyclization, giving rise to undesired quinolin-3-yl piperidinediones. This problem was circumvented by first reacting glutaric or adipic anhydride with 1, which yielded the monocarboxylic imidazoquinolines 2a and 2b, respectively; these intermediates were taken forward without purification and reacted again with 1 to afford the C4, C4′-des-amino precursors 3a and 3b (Scheme 1). Compounds 4a and 4b (with amines at C4 and C4′, respectively) were obtained by sequential N-oxidation of the quinoline nitrogen, reaction with benzoyl isocyanate to afford the C4 and C4′ N-benzoyl intermediate and, finally, cleavage of the N-benzoyl group using sodium methoxide as described by us earlier.5;11

Scheme 1.

Syntheses of imidazoquinoline dimers linked at C2.

Reagents: i. Glutaric anhydride (n=2) or adipic anhydride (n=3), Et3N, THF, 110°C; ii. 1, HBTU, Et3N, DMAP, DMF, 90 °C; iii. (a) 3-Chloroperoxybenzoic acid, CH2Cl2, CHCl3, MeOH, 45 °C; (b) Benzoyl isocyanate, CH2Cl2, 45 °C; (c) NaOCH3, MeOH, 80 °C; iv. (a) Suberoyl chloride (n=4) or dodecanedioyl dichloride (n=8), Et3N, THF; (b) NH3/MeOH, 150 °C.

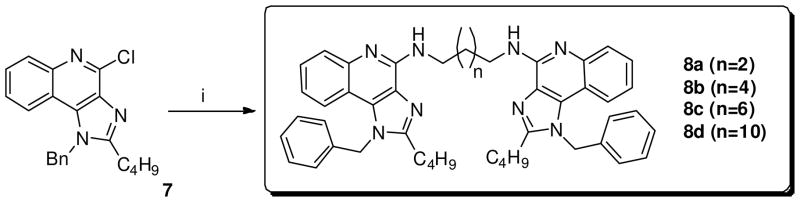

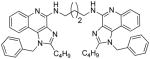

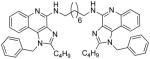

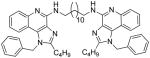

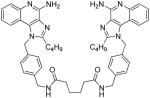

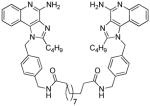

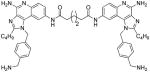

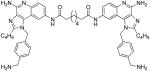

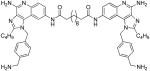

Next, the dimers linked via the C4-NH2 (8a-d) were synthesized by direct SNAr on 7 using α, ω-bis-amino alkanes (Scheme 2). Similarly, dimers linked at the N1 position on the 4-aminomethylene benzyl group (10a-c) were obtained using appropriate dicarboxylic acid chlorides (Scheme 3).

Scheme 2.

Syntheses of imidazoquinoline dimers linked at C4-NH2.

Reagents: i. 1,4-Diaminobutane (n=2) or 1,8-diaminooctane (n=4) or 1,10-diaminodecane (n=6) or 1,12-diaminododecane (n=10), MeOH, 140 °C;

Scheme 3.

Syntheses of imidazoquinoline dimers linked at N1-(4-aminomethylene)benzyl.

Reagents: i. Adipoyl chloride (n=1) or suberoyl chloride (n=3) or dodecanedioyl dichloride (n=7), Et3N, THF.

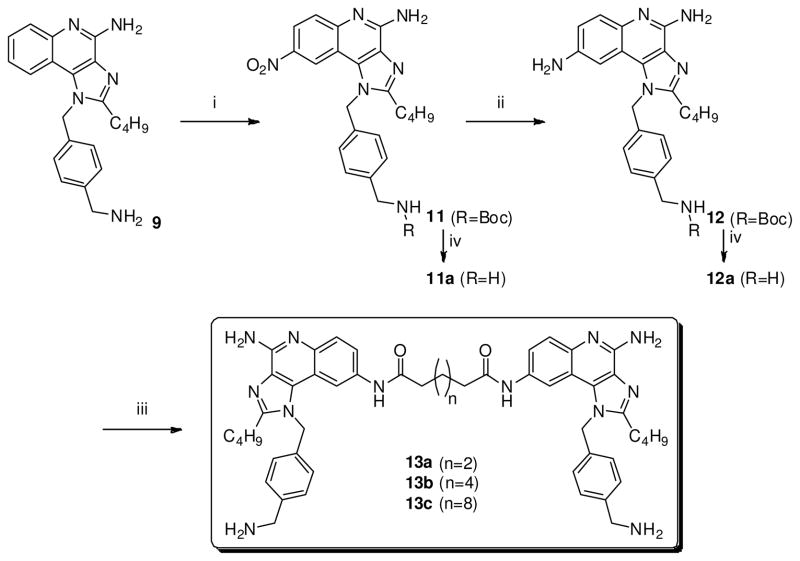

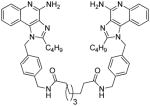

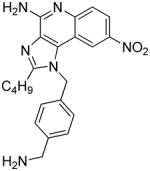

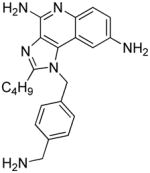

Linking the 13 series of dimers via the quinoline ring required the introduction of an additional amine at position C8. This was achieved via carefully controlled nitration of 9 using 1.2–1.3 equiv. of HNO3, followed by N-Boc protection of the amine on the N1 substituent, and subsequent reduction. Dimerization of the 4,8-diaminoimidazoquinoline 12 proceeded smoothly using dicarboxylic acid chlorides as described in the previous schemes. It is to be noted that the mono-nitro and mono-amino precursors 11 and 12 were also N-Boc deprotected and tested for TLR-modulatory activities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Agonistic and antagonistic activities of the dimers in TLR7 and TLR8 reporter gene assays. ND= not detected; NT=not tested.

| Compound number | Structure | TLR7 | TLR8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agonism (μM) | Antagonism (μM) | Agonism (μM) | Antagonism (μM) | ||

| 4a |

|

ND | 3.1 | ND | 3.2 |

| 4b |

|

ND | ND | ND | 15.63 |

| 6a |

|

ND | ND | ND | 10.92 |

| 6b |

|

ND | 17.88 | ND | 4.65 |

| 8a |

|

2.05 | ND | ND | ND |

| 8b |

|

0.56 | ND | ND | ND |

| 8c |

|

3.00 | ND | ND | ND |

| 8d |

|

1.42 | ND | ND | ND |

| 10a |

|

0.11 | ND | ND | ND |

| 10b |

|

0.24 | ND | ND | ND |

| 10c |

|

0.17 | ND | 4.78 | ND |

| 11a |

|

0.56 | ND | ND | ND |

| 12a |

|

0.45 | ND | ND | ND |

| 13a |

|

7.24 | ND | ND | ND |

| 13b |

|

4.02 | ND | ND | ND |

| 13c |

|

5.4 | ND | ND | ND |

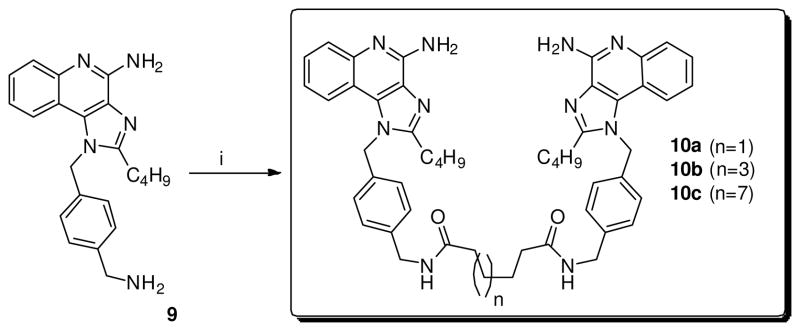

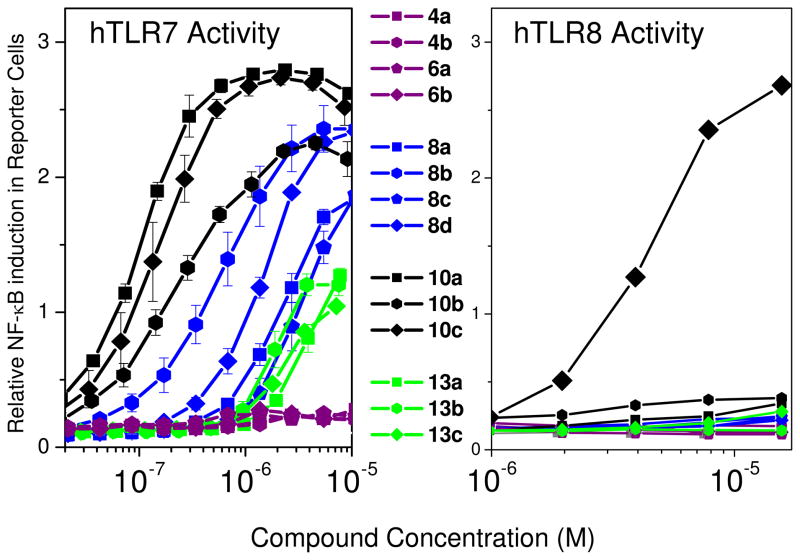

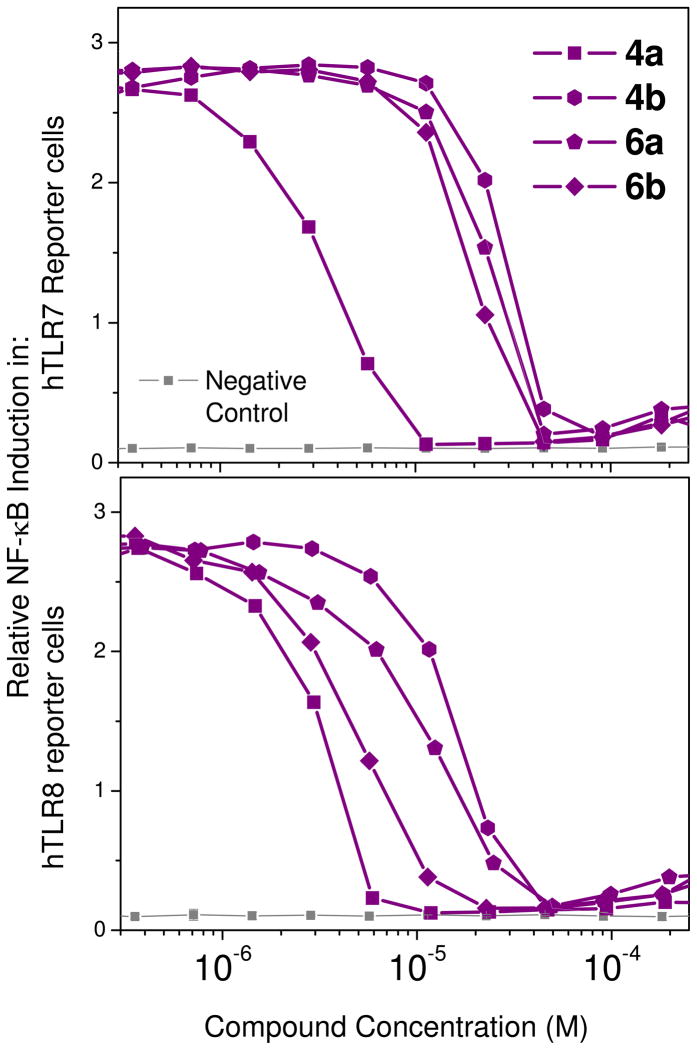

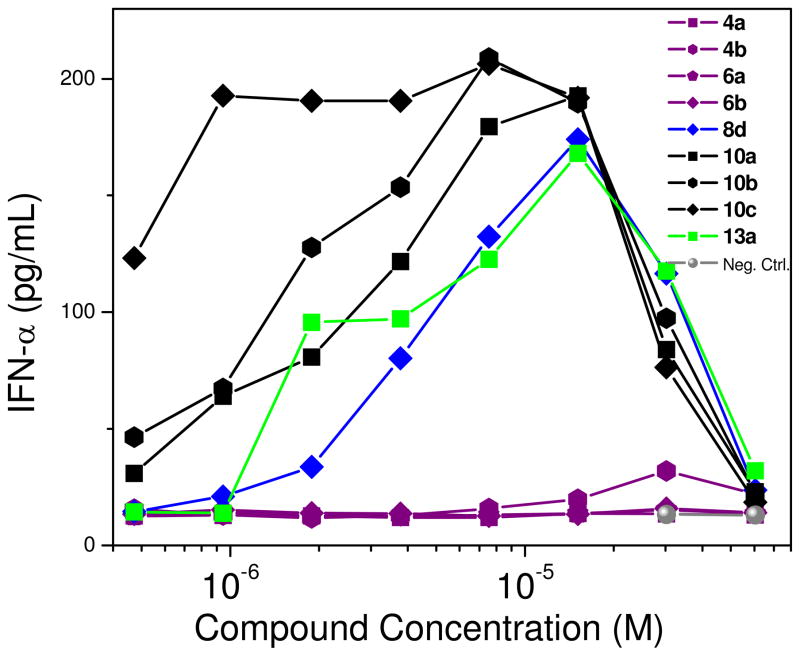

All compounds were unfortunately found to be inactive in TLR3 reporter gene assays. However, with the exception of 4 and 6 series of compounds, all other dimers retained TLR7-agonistic properties, the 10 series being the most potent (Fig. 1); interestingly, only 10c displayed both TLR7 and TLR8 agonism (Fig. 1 and Table 1), pointing to the necessity of a long linker for dual agonism. The C2-linked dimeric compounds 4a, 4b, 6a, and 6b unexpectedly showed potent antagonistic activity in both TLR7 and TLR8 assays, with 4a being most potent (IC50 values of 3.1 and 3.2 μM in TLR7 and TLR8 assays, respectively; Fig. 2, Table 1). A distinct relationship between linker length and inhibitory potency was not observed in this series. Given that the propylene linked 4a was the most active compound, it appeared possible that a shorter homolog with an ethylene linker may further enhance antagonistic activity; however, the solubility of this compound was intractably poor despite our attempts at evaluating a variety of salt forms, and we therefore decided not to include it in our bioassay screens.

Figure 1.

TLR7 and TLR8 agonistic activities of the imidazoquinoline dimers in human TLR-specific reporter gene assays.

Figure 2.

TLR7 (top) and TLR8 (bottom) antagonistic activities of the imidazoquinoline dimers 4a–b and 6a–b in human TLR-specific reporter gene assays.

Both agonistic and antagonistic compounds were then tested in appropriate secondary screens employing ex vivo human blood-derived models. The ligation of TLR7 and TLR8 trigger inflammatory responses characterized by the elaboration of type I interferon (IFN-α/β) by virus-infected cells via activation of downstream NF-κB and IFN-β promoters.31–36 IFN production is a hallmark response underlying cellular antiviral immune responses. It was desirable to verify that TLR7 agonism that we had observed (Fig. 1) manifested in IFN production in secondary screens. Using an ex vivo stimulation model using human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (hPBMC), it was demonstrated that IFN-α was indeed induced in a dose-dependent, bimodal manner as expected for innate immune responses (Fig. 3). Compound 10c was found to be the most potent; we surmise that this is due to its dual TLR7/8 agonistic activity. The 4 and 6 series were quiescent (Fig. 2), consistent with their apparent antagonistic behavior.

Figure 3.

IFN-α induction by select dimers in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. IFN-α was assayed by analyte specific ELISA after incubation of hPBMCs with graded concentrations of the test compound for 12h. A representative experiment of three independent experiments is shown.

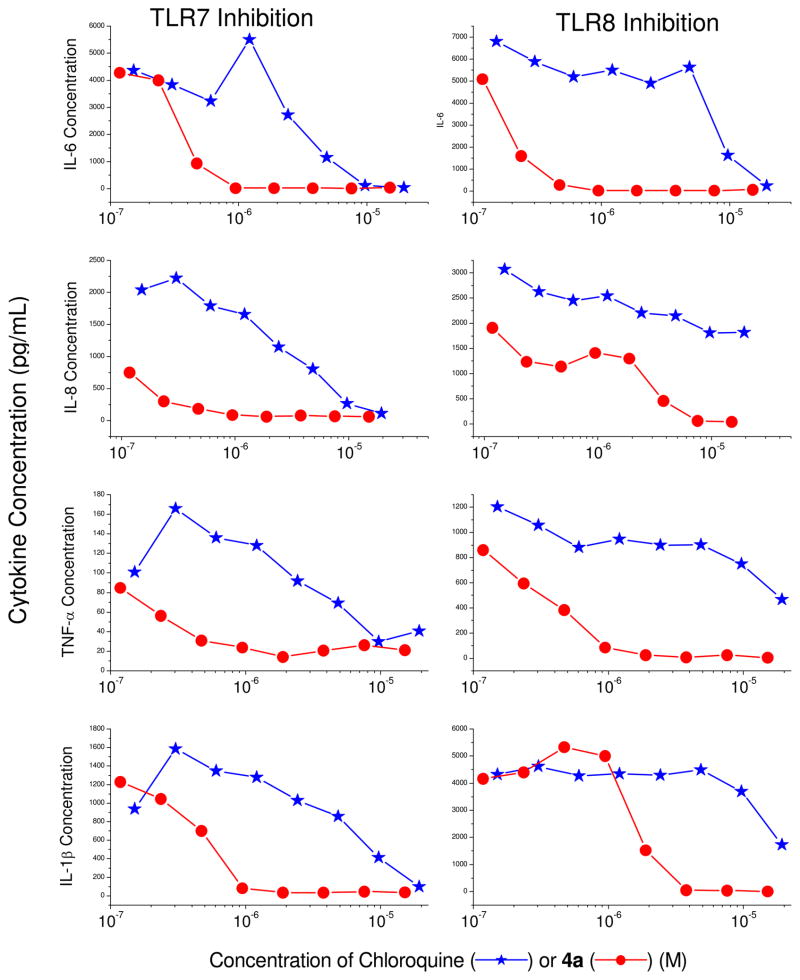

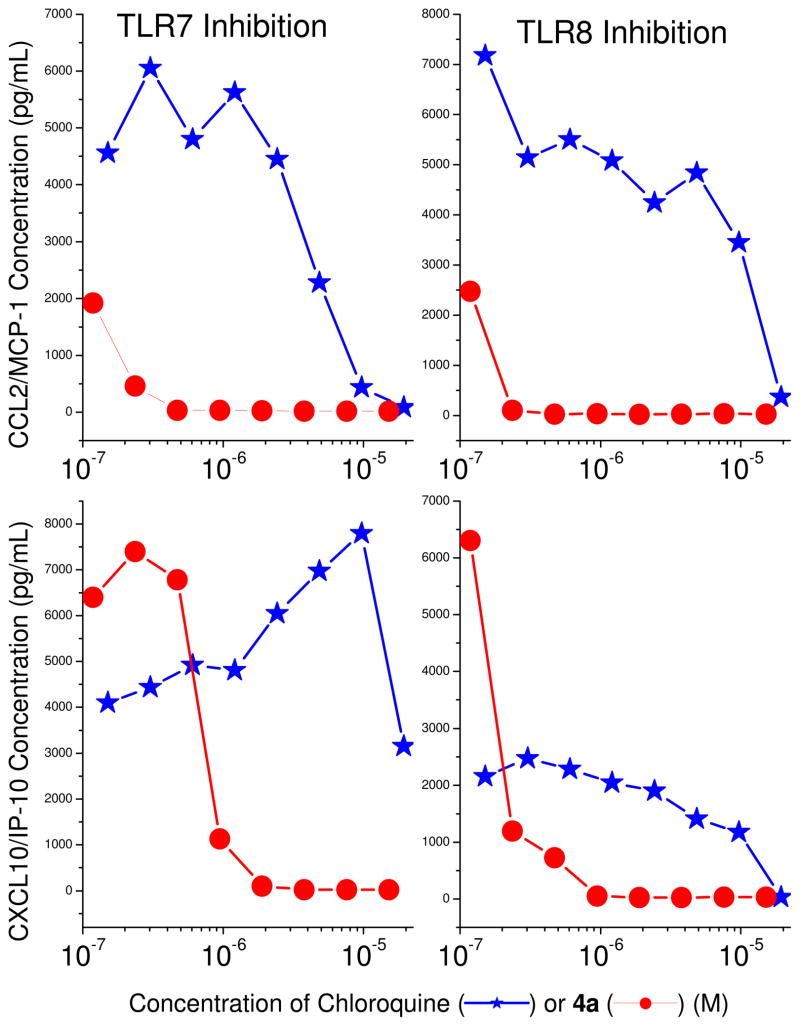

We elected to examine in detail the antagonistic properties of 4a in inhibiting TLR7 and TLR8- mediated induction of proinflammatory cytokines (Fig. 4) and chemokines (Fig. 5) in ex vivo models using human blood, since this compound was found to be the most potent antagonist in the series in primary screens (Table 1). We compared the potency of 4a alongside chloroquine, which is known to selectively suppress intracellular TLR7, but not TLR8 signaling via inhibition of endolysosomal acidification.37;38 We found 4a to be a potent inhibitor of both TLR7 and TLR8-induced cytokine and chemokine release with IC50 values of about 0.05–0.3 μM (Figs 4, 5). TLR8 signaling manifests predominantly in the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β.39;40 Chloroquine, a TLR7 antagonist, is a feeble inhibitor of TNF-α and IL-1β, while 4a, as would be expected for a TLR8 antagonist, potently inhibits the production of these proinflammatory cytokines (Fig. 4), as well as IL-6 and IL-8 which are typically induced secondarily, in an autocrine/paracrine manner.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of TLR7- and TLR8-mediated proinflammatory cytokine production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by chloroquine or 4a. Proinflammatory cytokines were assayed by cytokine bead array methods after incubation of hPBMCs with graded concentrations of the test compound for 12h in the presence of 10 μg/ml of either CL075 (TLR8 agonist) or gardiquimod (TLR7 agonist). A representative experiment of three independent experiments is shown.

Figure 5.

Inhibition of TLR7- and TLR8-mediated chemokine production in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells by chloroquine or 4a. Chemokines were assayed by cytokine bead array methods after incubation of hPBMCs with graded concentrations of the test compound for 12h in the presence of 10 μg/ml of either CL075 (TLR8 agonist) or gardiquimod (TLR7 agonist). A representative experiment of three independent experiments is shown.

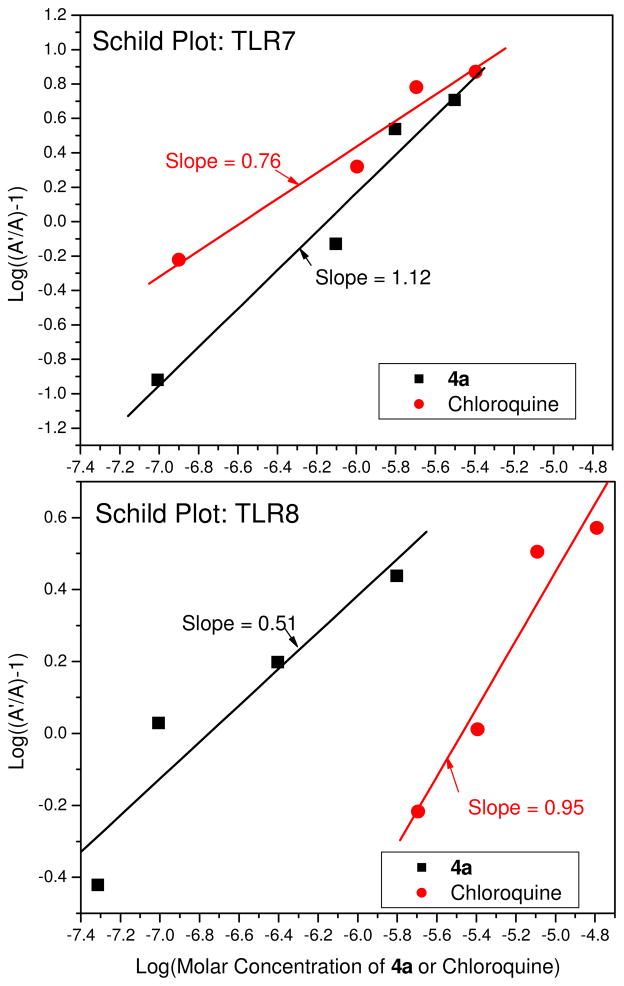

The relative specificity of chloroquine in inhibiting TLR7 as well as the dual TLR7/8-inhibitory activities of 4a are also evident in Schild plots (Fig. 6). Although the relationship between antagonist concentration and change in EC50 for TLR7 inhibition by 4a is near-ideal (slope: 1.12, Fig. 6), a distinct deviation from ideal competitive inhibition for TLR8 is observed (slope: 0.51), suggesting that additional mechanisms for TLR8 inhibition, possibly allosteric, may be operational. This is being investigated in greater detail.

Figure 6.

Schild plot analyses of inhibition of TLR7- and TLR8-induced activation. Experiments were performed in checker-board format, using a liquid handler, in 384-well plates which permitted the concentrations of both agonist and antagonist to be varied simultaneously along the two axes of the plate. Either imidazoquinoline (TLR7-specific agonist) or CL075 (TLR8-specific agonist) was used at a starting concentration of 20 μg/mL, and were two-fold diluted serially (along the rows). Next, 4a or chloroquine were two-fold diluted serially in HEK detection medium (along columns). Reporter cells were then added, incubated, and NF-κB activation measured as described in the text. A and A′ (Y-axis) are defined respectively as the EC50 value in the absence of antagonist, and the EC50 values in the presence of varying concentrations of antagonist.

In conclusion, we have observed that the C4, C8, and N1-aryl-linked dimers are agonists, with the last being most potent. The N1-aryl-linked dimers are of particular interest as potential vaccine adjuvants are currently being evaluated in animal models. The C2-linked dimers were found to be potently antagonistic at both TLR7 and TLR8 and may be useful as small molecule probes for examining the effects of inhibiting endolysosomal TLR signaling in HIV.

Experimental Section

All of the solvents and reagents used were obtained commercially and used as such unless noted otherwise. Moisture- or air-sensitive reactions were conducted under nitrogen atmosphere in oven-dried (120 °C) glass apparatus. The solvents were removed under reduced pressure using standard rotary evaporators. Flash column chromatography was carried out using RediSep Rf ‘Gold’ high performance silica columns on CombiFlash Rf instrument unless otherwise mentioned, while thin-layer chromatography was carried out on silica gel CCM pre-coated aluminum sheets. Purity for all final compounds was confirmed to be greater than 97% by LC-MS using a Zorbax Eclipse Plus 4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm analytical reverse phase C18 column with H2O-isopropanol or H2O-CH3CN gradients and an Agilent ESI-TOF mass spectrometer (mass accuracy of 3 ppm) operating in the positive ion acquisition mode. All the compounds synthesized were obtained as solids.

Synthesis of Compound 4a: 2,2′-(propane-1,3-diyl)bis(1-benzyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-4-amine)

To a solution of 1 (100 mg, 0.4 mmol) in anhydrous THF, were added triethylamine (53 mg, 0.52 mmol) and glutaric anhydride (60 mg, 0.52 mmol) and the reaction vessel was heated in a microwave for 2 hours at 110 °C. The solvent was then removed under vacuum to obtain the crude product 2, which was then dissolved in anhydrous DMF and to this solution, were added HBTU (167 mg, 0.44 mmol), triethylamine (53 mg, 0.52 mmol), 1 (100 mg, 0.4 mmol) and a catalytic amount of DMAP. The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 hours at 90 °C. The solvent was then removed under vacuum and the residue was purified using column chromatography (12% MeOH/dichloromethane) to obtain the intermediate the compound 3 (157 mg). To a solution of 3 in solvent mixture of MeOH:dichloromethane:chloroform (0.1:1:1), was added 3-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (242 mg, 1.4 mmol) and the reaction mixture was refluxed at 45 °C for 40 minutes. The solvent was then removed and the residue was purified using column chromatography (35 % MeOH/dichloromethane) to obtain the bis-N-oxide derivative (130 mg). bis-N-oxide derivative (110 mg, 0.19 mmol) was then dissolved in anhydrous dichloromethane, followed by the addition of benzoyl isocyanate (96 mg, 0.67 mmol) and heated at 45 °C for 15 minutes. The solvent was then removed under vacuum and the residue was dissolved in anhydrous MeOH, followed by addition of excess of sodium methoxide and heated at 80 °C for 2 hours. The solvent was then removed under vacuum and the residue was purified using column chromatography (50% MeOH/dichloromethane) to obtain the compound 4a (25 mg, 11%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ 14.30 (s, 2H), 9.48 – 8.30 (bs, 4H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.65 – 7.60 (m, 2H), 7.38 – 7.34 (m, 2H), 7.26 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H), 7.17 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.03 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 5.94 (s, 4H), 3.16 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 4H), 2.44 – 2.35 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO) δ 156.22, 148.86, 135.32, 135.30, 133.48, 129.51, 128.93, 127.57, 125.47, 124.72, 124.54, 121.49, 118.31, 112.16, 48.35, 25.21, 24.43. MS (ESI) calculated for C37H32N8, m/z 588.2750, found 589.2860 (M + H)+.

Compound 4b was synthesized similarly as described for compound 4a

4b

1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO) δ 13.86 (s, 2H), 8.88 (bs, 4H), 7.93 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.83 – 7.79 (m, 2H), 7.66 – 7.61 (m, 2H), 7.39 – 7.34 (m, 2H), 7.27 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H), 7.18 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.01 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 5.94 (s, 4H), 2.99 (s, 4H), 1.83 (s, 4H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO) δ 156.55, 148.75, 135.38, 133.62, 129.50, 128.95, 127.60, 125.42, 124.74, 124.54, 121.54, 118.48, 112.28, 48.34, 26.49, 26.14. MS (ESI) calculated for C38H34N8, m/z 602.2906, found 603.3272 (M + H)+ and 302.1705 (M + 2H)2+

Synthesis of Compound 6a: 2,2′-(hexane-1,6-diyl)bis(1-benzyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-4-amine)

To a solution of 5 (60 mg, 0.21 mmol) in anhydrous THF, were added triethylamine (54 mg, 0.53 mmol), and suberoyl chloride (23 mg, 0.11 mmol) and the reaction mixture was stirred for 6 hours. The solvent was then removed under vacuum and the residue was dissolved in EtOAc and washed with water/brine. The EtOAc fraction was then dried using sodium sulfate and evaporated under vacuum to obtain the intermediate amide compound, which was then dissolved in 1 mL solution of 2M ammonia in MeOH and heated at 150 °C for 15 hours. The solvent was then removed under vacuum and the residue was purified using column chromatography (20% MeOH/dichloromethane) to obtain the compound 6a (8 mg, 12 %). 1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.96 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.65 (dd, J = 11.5, 4.2 Hz, 2H), 7.39 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 7.25 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 7.06 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 5.93 (s, 4H), 2.97 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 4H), 1.85 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 4H), 1.43 (s, 4H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, MeOD) δ 158.93, 137.73, 136.20, 135.30, 131.11, 130.47, 129.31, 126.65, 126.57, 125.81, 122.94, 119.65, 114.20, 50.13, 29.70, 27.92. MS (ESI) calculated for C40H38N8, m/z 630.3219, found 631.3415 (M + H)+.

Compound 6b was synthesized similarly as described for compound 6a

6b

1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.86 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.69 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.51 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.32 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 4H), 7.28 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.06 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 5.88 (s, 4H), 2.96 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H), 1.79 (dt, J = 15.3, 7.7 Hz, 4H), 1.37 (dd, J = 14.9, 7.4 Hz, 4H), 1.32 – 1.24 (m, J = 11.6 Hz, 4H), 1.23 (d, J = 10.1 Hz, 4H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, MeOD) δ 157.44, 151.60, 136.61, 130.41, 129.74, 129.22, 126.69, 126.46, 124.90, 123.38, 122.15, 115.12, 50.05, 30.32, 30.25, 30.17, 28.49, 28.17. MS (ESI) calculated for C44H46N8, m/z 686.3845, found 687.3749 (M + H)+ and 344.1949 (M + 2H)2+

Synthesis of Compound 8b: N1,N8-bis(1-benzyl-2-butyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-4-yl)octane-1,8-diamine

To a solution of 7 (50 mg, 0.14 mmol) in 1 mL of anhydrous MeOH, was added 1,8-diaminooctane (10 mg, 0.07 mmol) and the reaction mixture was heated at 140 °C for 4 hours. The solvent was then removed under vacuum and the residue was purified using column chromatography (8% MeOH/dichloromethane) to obtain the compound 8b (12 mg, 22%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.87 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.68 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.36 – 7.26 (m, 6H), 7.09 – 7.01 (m, 6H), 5.78 (s, 2H), 5.72 (s, 4H), 3.77 (dd, J = 12.8, 6.6 Hz, 4H), 2.92 – 2.83 (m, 4H), 1.87 – 1.74 (m, 8H), 1.58 – 1.50 (m, 4H), 1.45 (dt, J = 15.1, 7.5 Hz, 8H), 0.93 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 153.34, 150.78, 145.51, 135.62, 129.20, 127.93, 127.41, 127.07, 126.68, 125.59, 121.34, 119.52, 114.87, 48.81, 40.76, 30.18, 29.98, 29.50, 27.21, 22.56, 13.77. MS (ESI) calculated for C50H58N8, m/z 770.4784, found 771.4963 (M + H)+ and 386.2570 (M + 2H)2+.

Compounds 8a, 8c and 8d were synthesized similarly as described for compound 8b

8a

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.86 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.65 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.0 Hz, 2H), 7.41 – 7.35 (m, 2H), 7.35 – 7.24 (m, 6H), 7.09 – 6.99 (m, 6H), 5.86 (s, 2H), 5.69 (s, 4H), 3.87 (s, 4H), 2.88 – 2.81 (m, 4H), 2.00 (s, 4H), 1.76 (ddd, J = 13.0, 9.0, 7.7 Hz, 4H), 1.46 – 1.37 (m, 4H), 0.90 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 151.27, 148.66, 143.44, 133.52, 130.85, 128.77, 127.28, 127.13, 125.85, 125.38, 124.95, 124.60, 123.50, 123.40, 119.29, 117.45, 112.81, 46.71, 38.40, 28.01, 25.51, 25.10, 20.47, 11.68. MS (ESI) calculated for C46H50N8, m/z 714.4158, found 715.4333 (M + H)+ and 358.2263 (M + 2H)2+

8c

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.84 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.66 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.0 Hz, 2H), 7.40 – 7.36 (m, 2H), 7.33 – 7.26 (m, 6H), 7.07 – 7.01 (m, 6H), 5.73 (s, 2H), 5.70 (s, 4H), 3.74 (dd, J = 12.7, 6.5 Hz, 4H), 2.88 – 2.83 (m, 4H), 1.80 – 1.72 (m, 8H), 1.53 – 1.24 (m, 16H), 0.91 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 151.76, 149.23, 143.97, 134.05, 131.32, 127.81, 127.63, 126.36, 125.85, 125.50, 125.10, 124.01, 123.84, 119.75, 117.95, 113.30, 47.23, 39.17, 28.62, 28.39, 28.06, 27.95, 25.65, 20.98, 12.20. MS (ESI) calculated for C52H62N8, m/z 798.5097, found 799.5416 (M + H)+ and 400.2799 (M + 2H)2+

8d

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.84 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.65 (dd, J = 8.2, 1.0 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (ddd, J = 8.3, 7.1, 1.3 Hz, 2H), 7.34 – 7.24 (m, 6H), 7.06 – 7.00 (m, 6H), 5.74 (s, 2H), 5.69 (s, 4H), 3.74 (dd, J = 12.6, 6.5 Hz, 4H), 2.86 (dd, J = 17.4, 9.6 Hz, 4H), 1.83 – 1.69 (m, 8H), 1.56 – 1.30 (m, 20H), 0.91 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 151.81, 149.27, 144.02, 134.08, 131.36, 127.68, 126.41, 125.87, 125.53, 125.16, 124.05, 119.81, 118.00, 113.34, 47.27, 39.25, 28.65, 28.44, 28.15, 28.13, 28.01, 25.70, 25.68, 21.03, 12.24. MS (ESI) calculated for C54H66N8, m/z 826.5410, found 827.5796 (M + H)+ and 414.2977 (M + 2H)2+

Synthesis of Compound 10b: N1,N8-bis(4-((4-amino-2-butyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-1-yl)methyl)benzyl)octanediamide

To a solution of 9 (25 mg, 0.058 mmol) in anhydrous THF, were added triethylamine (15 mg, 0.15 mmol) and suberoyl chloride (6 mg, 0.029 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 hour and then the solvent was removed under vacuum. The residue was then purified using column chromatography (30% MeOH/dichloromethane) to obtain the compound 10b (8 mg, 32%) 1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.65 (dd, J = 8.3, 0.9 Hz, 2H), 7.55 – 7.51 (m, 2H), 7.27 (ddd, J = 8.3, 7.1, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 7.12 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 4H), 6.95 (ddd, J = 8.2, 7.2, 1.1 Hz, 2H), 6.88 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 4H), 5.69 (s, 4H), 4.18 (s, 4H), 2.84 – 2.78 (m, 4H), 2.03 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 4H), 1.64 (dt, J = 15.4, 7.6 Hz, 4H), 1.47 – 1.37 (m, 4H), 1.30 (dq, J = 14.8, 7.4 Hz, 4H), 1.16 – 1.10 (m, 4H), 0.80 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, MeOD) δ 176.03, 156.18, 152.62, 144.89, 140.08, 136.09, 135.55, 129.44, 128.54, 126.95, 126.86, 126.21, 123.42, 121.58, 115.75, 49.58, 43.58, 36.85, 30.85, 29.75, 27.82, 26.74, 23.43, 14.11. MS (ESI) calculated for C52H60N10O2, m/z 856.4901, found 879.4711 (M + Na+) and 429.2430 (M + 2H)2+

Compounds 10a and 10c were synthesized similarly as described for compound 10b

10a

1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.85 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 7.68 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 7.52 – 7.45 (m, 2H), 7.26 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 4H), 7.23 – 7.16 (m, 2H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 4H), 5.85 (s, 4H), 4.30 (s, 4H), 2.99 – 2.93 (m, 4H), 2.19 (t, J = 6.0 Hz, 4H), 1.80 (dd, J = 15.3, 7.7 Hz, 4H), 1.58 (t, J = 3.1 Hz, 4H), 1.45 (dd, J = 15.0, 7.5 Hz, 4H), 0.94 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 174.28, 156.00, 150.28, 138.78, 135.01, 134.27, 128.13, 128.05, 125.44, 123.28, 121.97, 120.73, 113.67, 48.28, 42.15, 35.17, 29.21, 26.38, 25.03, 21.96, 12.68. MS (ESI) calculated for C50H56N10O2, m/z 828.4588, found 829.4440 (M + H)+ and 415.2244 (M + 2H)2+

10c

1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.69 (dd, J = 8.3, 0.8 Hz, 2H), 7.54 (dd, J = 8.4, 0.7 Hz, 2H), 7.31 (ddd, J = 8.4, 7.2, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 4H), 7.00 (ddd, J = 8.2, 7.2, 1.1 Hz, 2H), 6.90 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 4H), 5.73 (s, 4H), 4.20 (s, 4H), 2.85 – 2.81 (m, 4H), 2.06 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 4H), 1.66 (dt, J = 15.4, 7.6 Hz, 4H), 1.44 (dt, J = 14.4, 7.3 Hz, 4H), 1.31 (dq, J = 14.8, 7.4 Hz, 4H), 1.10 (dd, J = 29.4, 26.2 Hz, 12H), 0.81 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, MeOD) δ 176.17, 156.64, 152.26, 143.34, 140.20, 135.93, 135.90, 129.44, 128.92, 126.85, 126.77, 125.13, 123.90, 121.81, 115.51, 49.64, 43.55, 36.99, 30.78, 30.36, 30.23, 30.11, 27.82, 26.96, 23.41, 14.11. MS (ESI) calculated for C56H68N10O2, m/z 912.5527, found 913.5886 (M + H)+ and 457.2974 (M + 2H)2+

Synthesis of Compound 11: tert-butyl 4-((4-amino-2-butyl-8-nitro-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-1-yl)methyl)benzylcarbamate

To a solution of 9 (500 mg, 1.16 mmol) in H2SO4, was added HNO3 (95 mg, 1.511 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 hours, followed by neutralization of sulfuric acid by slow addition of sodium carbonate solution. EtOAc was added to this solution to extract the compound, followed by washing with water/brine. The EtOAc fraction was then dried using sodium sulfate and evaporated under vacuum to obtain the residue. The residue as dissolved in MeOH and di-tert-butyl dicarbonate was added to it. The reaction was stirred for 30 minutes followed by removal of the solvent under vacuum to obtain the residue, which was purified using column chromatography (7% MeOH/dichloromethane) to obtain the compound 11 (200 mg, 34%).1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.67 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 8.24 – 8.18 (m, 1H), 7.76 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H), 7.28 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 7.08 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 5.95 (s, 2H), 5.76 (s, 2H), 4.87 (s, 1H), 4.29 (d, J = 5.5 Hz, 2H), 3.05 – 2.95 (m, 2H), 1.88 (dt, J = 15.5, 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.51 (dd, J = 14.9, 7.3 Hz, 2H), 1.45 (s, 9H), 0.99 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, CDCl3) δ 155.18, 153.33, 148.68, 141.64, 139.53, 133.91, 133.29, 128.41, 127.42, 127.25, 125.92, 121.27, 117.28, 113.88, 48.81, 44.09, 30.00, 28.35, 27.20, 22.54, 13.78. MS (ESI) calculated for C27H32N6O4, m/z 504.2485, found 505.2541 (M + H)+

Synthesis of Compound 11a: 1-(4-(aminomethyl) benzyl)-2-butyl-8-nitro-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-4-amine

Compound 11 (10 mg, 0.02 mmol) was dissolved in 1 mL solution of HCl/dioxane and stirred for 12 hours. The solvent was then removed under vacuum and the residue was washed with diethyl ether to afford the compound 11a in quantitative yields. 1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.77 (d, J = 1.7 Hz, 1H), 8.47 – 8.41 (m, 1H), 7.98 (d, J = 9.1 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 6.09 (s, 2H), 4.11 (s, 2H), 3.12 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 1.98 – 1.88 (m, 2H), 1.59 – 1.49 (m, 2H), 1.00 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 158.58, 150.14, 143.93, 137.46, 135.58, 135.36, 133.41, 129.86, 126.29, 125.89, 123.43, 119.40, 117.94, 112.44, 48.52, 42.36, 29.05, 26.44, 21.94, 12.71. MS (ESI) calculated for C22H24N6O2, m/z 404.1961, found 405.1993 (M + H)+

Synthesis of Compound 12: tert-butyl 4-((4,8-diamino-2-butyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-1-yl)methyl)benzylcarbamate

To a solution of 11 (190 mg, 0.377 mmol) in anhydrous MeOH, were added a catalytic amount of Pd/C and the reaction mixture was subjected to hydrogenation at 60 psi hydrogen pressure for 4 hours. The reaction mixture was then filtered through celite and the filtrate was evaporated under vacuum to obtain the compound 12 (160 mg, 90%).1H NMR (400 MHz, MeOD) δ 7.49 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.25 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.14 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.97 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 5.75 (s, 2H), 4.19 (s, 2H), 2.92 – 2.86 (m, 2H), 1.73 (dt, J = 15.4, 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.43 (s, 9H), 0.92 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (101 MHz, MeOD) δ 154.56, 148.78, 142.89, 139.42, 136.71, 134.64, 133.60, 127.53, 125.80, 125.57, 118.16, 115.16, 103.42, 78.81, 43.18, 29.41, 27.33, 26.41, 22.01, 12.67. MS (ESI) calculated for C27H34N6O2, m/z 474.2743, found 475.2733 (M + H)+

Synthesis of Compound 12a: 1-(4-(aminomethyl)benzyl)-2-butyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinoline-4,8-diamine

Compound 12 (10 mg, 0.021 mmol) was dissolved in 1 mL of HCl/dioxane solution and stirred for 12 hours. The solvent was then removed under vacuum and the residue was washed with diethyl ether to obtain the compound 12a in quantitative yields. 1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.10 (s, 1H), 7.97 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (dd, J = 8.9, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 6.04 (s, 2H), 4.12 (s, 2H), 3.03 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 1.92 – 1.84 (m, 2H), 1.53 – 1.43 (m, 2H), 0.96 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, DMSO) δ 156.84, 147.83, 135.56, 134.67, 133.58, 129.58, 129.54, 126.08, 125.63, 124.97, 119.52, 113.08, 48.08, 41.64, 29.09, 26.17, 21.75, 13.66. MS (ESI) calculated for C22H26N6, m/z 374.2219, found 375.2508 (M + H)+

Synthesis of Compound 13b: N1,N8-bis(4-amino-1-(4-(aminomethyl)benzyl)-2-butyl-1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolin-8-yl)octanediamide

To a solution of 12 (74 mg, 0.156 mmol) in anhydrous THF, were added triethylamine (39 mg, 0.39 mmol) and suberoyl chloride (15 mg, 0.07 mmol), and the reaction mixture was stirred for 1 hour. The solvent was then removed under vacuum and the residue was purified using column chromatography (20% MeOH/dichloromethane) to obtain the bis-N-Boc protected compound which was then dissolved in 1 mL of HCl/dioxane solution and stirred for 14 hours. The solvent was then removed under vacuum and the residue was washed with diethyl ether to afford the compound 13b (12 mg, 19%; low yields were due to partial acylation of the C4-NH2 which was found to be unstable). 1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.62 (s, 2H), 7.70 – 7.65 (m, 2H), 7.61 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.44 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 4H), 7.18 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 4H), 5.93 (s, 4H), 4.07 (s, 4H), 2.98 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 4H), 2.37 (dd, J = 16.6, 9.4 Hz, 4H), 1.85 (dt, J = 15.0, 7.6 Hz, 4H), 1.71 (s, 4H), 1.52 – 1.40 (m, 8H), 0.94 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, MeOD) δ 174.75, 159.05, 149.75, 137.64, 137.34, 137.11, 134.51, 131.24, 130.93, 127.87, 126.22, 123.18, 119.97, 114.28, 111.99, 49.82, 43.82, 37.93, 30.27, 30.01, 27.81, 26.63, 23.36, 14.11. MS (ESI) calculated for C52H62N12O2, m/z 886.5119, found 909.5031 (M + Na+) and 444.2632 (M + 2H)2+.

Compounds 13a and 13c were synthesized similarly as described for compound 13b

13a

1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.57 (s, 2H), 7.62 – 7.54 (m, 4H), 7.35 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 4H), 7.10 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H), 5.85 (s, 4H), 3.98 (s, 4H), 2.90 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H), 2.36 (s, 4H), 1.77 (dt, J = 15.2, 7.6 Hz, 4H), 1.73 – 1.61 (m, 4H), 1.45 – 1.30 (m, 4H), 0.86 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, MeOD) δ 174.43, 159.11, 149.83, 137.66, 137.40, 137.16, 134.53, 131.33, 130.94, 127.89, 126.30, 123.18, 120.01, 114.38, 112.05, 49.82, 43.83, 37.65, 30.32, 27.81, 26.28, 23.37, 14.12. MS (ESI) calculated for C50H58N12O2, m/z 858.4806, found 859.4131 (M + H)+ and 430.2113 (M + 2H)2+.

13c

1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD) δ 8.63 (s, 2H), 7.66 (d, J = 9.0 Hz, 2H), 7.58 (d, J = 8.9 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 4H), 7.15 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 4H), 5.91 (s, 4H), 4.04 (s, 4H), 2.96 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 4H), 2.33 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 4H), 1.83 (dt, J = 15.2, 7.7 Hz, 4H), 1.65 (s, 4H), 1.44 (dq, J = 14.7, 7.3 Hz, 4H), 1.38 – 1.21 (m, 12H), 0.92 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 6H). 13C NMR (126 MHz, MeOD) δ 174.82, 159.01, 149.63, 137.68, 137.27, 137.10, 134.50, 131.24, 130.93, 129.84, 127.86, 126.00, 123.16, 120.01, 114.24, 111.92, 49.87, 43.82, 43.75, 38.04, 30.45, 30.34, 30.29, 30.23, 27.78, 26.78, 23.35, 14.11. MS (ESI) calculated for C56H70N12O2, m/z 942.5745, found 943.5746 (M + H)+ and 472.2987 (M + 2H)2+.

TLR3/7/8 Reporter Gene assays (NF-κB induction)

The induction of NF-κB was quantified using HEK-Blue-3, HEK-Blue-7 and HEK-Blue-8 cells as previously described by us.5;7;11 HEK293 cells were stably transfected with human TLR3 (or human TLR7 or human TLR8), MD2, and secreted alkaline phosphatase (sAP), and were maintained in HEK-Blue™ Selection medium containing zeocin and normocin. Stable expression of secreted alkaline phosphatase (sAP) under control of NF-κB/AP-1 promoters is inducible by the TLR3 (or TLR7 or TLR8) agonists, and extracellular sAP in the supernatant is proportional to NF-κB induction. HEK-Blue cells were incubated at a density of ~105 cells/ml in a volume of 80 μl/well, in 384-well, flat-bottomed, cell culture-treated microtiter plates until confluency was achieved, and subsequently graded concentrations of stimuli. sAP was assayed spectrophotometrically using an alkaline phosphatase-specific chromogen (present in HEK-detection medium as supplied by the vendor) at 620 nm.

Antagonism assays were done as described by us earlier10 using the following agonists at a constant concentration: TLR3 Poly(I:C) (10 ng/mL); TLR7: gardiquimod (1 μg/mL); TLR8: CL075(1 μg/mL) mixed with graded concentrations of the test compounds.

IFN-α induction in human PBMCs

Aliquots (106 cells in 100 μL) of hPBMCs isolated from blood obtained from healthy human donors after informed consent by conventional Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation were stimulated for 12 h with graded concentrations of test compounds. The supernatant was isolated by centrifugation, diluted 1:20, and IFN-α was assayed in triplicate using a high-sensitivity human IFN-α-specific ELISA kit (PBL Interferon Source, Piscataway, NJ).

Cytokine and chemokine in human PBMCs

Aliquots (106 cells in 100 μL) of hPBMCs isolated from blood obtained from healthy human donors after informed consent by conventional Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation were stimulated for 12 h with graded concentrations of test compounds. The supernatant was isolated by centrifugation, diluted 1:20, and cytokines and chemokines were assayed in triplicate using analyte-specific cytokine/chemokine bead array assays as reported by us previously.41

Supplementary Material

Scheme 4.

Syntheses of imidazoquinoline dimers linked at C8-NH2.

Reagents: i. (a) HNO3, H2SO4; (b) (Boc)2O, Et3N, MeOH; ii. H2, Pt/C, MeOH, 60 psi; iii. (a) Adipoyl chloride (n=2) or suberoyl chloride (n=4) or dodecanedioyl dichloride (n=8), Et3N, THF; (b) HCl/dioxane, iv. HCl/dioxane.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH/NIAID contract HHSN272200900033C.

Abbreviations

- DMAP

4-dimethylaminopyridine

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- EC50

half-maximal effective concentration

- ELISA

enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- ESI-TOF

electrospray ionization-time of flight

- HBTU

O-benzotriazole-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyl uronium hexafluorophosphate

- HEK

human embryonic kidney

- hPBMCs

human peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- IFN

interferon

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- m-CPBA

meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-kappa B

- PAMP

pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- sAP

secreted alkaline phophatase

- ssRNA

single stranded RNA

- Th1

helper T–type 1

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- TLR

Toll-like receptor

Footnotes

Supporting Information: Characterization of intermediates and final compounds (1H, 13C, mass spectra). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumagai Y, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pathogen recognition by innate receptors. J Infect Chemother. 2008;14:86–92. doi: 10.1007/s10156-008-0596-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akira S. Innate immunity to pathogens: diversity in receptors for microbial recognition. Immunol Rev. 2009;227:5–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen recognition and innate immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shukla NM, Malladi SS, Mutz CA, Balakrishna R, David SA. Structure-activity relationships in human toll-like receptor 7-active imidazoquinoline analogues. J Med Chem. 2010;53:4450–4465. doi: 10.1021/jm100358c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu W, Li R, Malladi SS, Warshakoon HJ, Kimbrell MR, Amolins MW, Ukani R, Datta A, David SA. Structure-activity relationships in toll-like receptor-2 agonistic diacylthioglycerol lipopeptides. J Med Chem. 2010;53:3198–3213. doi: 10.1021/jm901839g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hood JD, Warshakoon HJ, Kimbrell MR, Shukla NM, Malladi S, Wang X, David SA. Immunoprofiling toll-like receptor ligands: Comparison of immunostimulatory and proinflammatory profiles in ex vivo human blood models. Hum Vaccin. 2010;6:1–14. doi: 10.4161/hv.6.4.10866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Warshakoon HJ, Hood JD, Kimbrell MR, Malladi S, Wu WY, Shukla NM, Agnihotri G, Sil D, David SA. Potential adjuvantic properties of innate immune stimuli. Hum Vaccin. 2009;5:381–394. doi: 10.4161/hv.5.6.8175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shukla NM, Lewis TC, Day TP, Mutz CA, Ukani R, Hamilton CD, Balakrishna R, David SA. Toward self-adjuvanting subunit vaccines: model peptide and protein antigens incorporating covalently bound toll-like receptor-7 agonistic imidazoquinolines. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:3232–3236. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shukla NM, Malladi SS, Day V, David SA. Preliminary evaluation of a 3H imidazoquinoline library as dual TLR7/TLR8 antagonists. Bioorg Med Chem. 2011;19:3801–3811. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2011.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shukla NM, Kimbrell MR, Malladi SS, David SA. Regioisomerism-dependent TLR7 agonism and antagonism in an imidazoquinoline. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:2211–2214. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.02.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sabado RL, O’Brien M, Subedi A, Qin L, Hu N, Taylor E, Dibben O, Stacey A, Fellay J, Shianna KV, Siegal F, Shodell M, Shah K, Larsson M, Lifson J, Nadas A, Marmor M, Hutt R, Margolis D, Garmon D, Markowitz M, Valentine F, Borrow P, Bhardwaj N. Evidence of dysregulation of dendritic cells in primary HIV infection. Blood. 2010;116:3839–3852. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-273763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fraietta JA, Mueller YM, Do DH, Holmes VM, Howett MK, Lewis MG, Boesteanu AC, Alkan SS, Katsikis PD. Phosphorothioate 2′, deoxyribose oligomers as microbicides that inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection and block Toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) and TLR9 triggering by HIV-1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4064–4073. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00367-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mandl JN, Barry AP, Vanderford TH, Kozyr N, Chavan R, Klucking S, Barrat FJ, Coffman RL, Staprans SI, Feinberg MB. Divergent TLR7 and TLR9 signaling and type I interferon production distinguish pathogenic and nonpathogenic AIDS virus infections. Nat Med. 2008;14:1077–1087. doi: 10.1038/nm.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Botos I, Segal DM, Davies DR. The structural biology of Toll-like receptors. Structure. 2011;19:447–459. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin MS, Kim SE, Heo JY, Lee ME, Kim HM, Paik SG, Lee H, Lee JO. Crystal structure of the TLR1-TLR2 heterodimer induced by binding of a tri-acylated lipopeptide. Cell. 2007;130:1071–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jin MS, Lee JO. Structures of TLR-ligand complexes. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:414–419. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu L, Botos I, Wang Y, Leonard JN, Shiloach J, Segal DM, Davies DR. Structural basis of toll-like receptor 3 signaling with double-stranded RNA. Science. 2008;320:379–381. doi: 10.1126/science.1155406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hemmi H, Kaisho T, Takeuchi O, Sato S, Sanjo H, Hoshino K, Horiuchi T, Tomizawa H, Takeda K, Akira S. Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:196–200. doi: 10.1038/ni758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerster JF, Lindstrom KJ, Miller RL, Tomai MA, Birmachu W, Bomersine SN, Gibson SJ, Imbertson LM, Jacobson JR, Knafla RT, Maye PV, Nikolaides N, Oneyemi FY, Parkhurst GJ, Pecore SE, Reiter MJ, Scribner LS, Testerman TL, Thompson NJ, Wagner TL, Weeks CE, Andre JD, Lagain D, Bastard Y, Lupu M. Synthesis and structure-activity-relationships of 1H-imidazo[4,5-c]quinolines that induce interferon production. J Med Chem. 2005;48:3481–3491. doi: 10.1021/jm049211v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weterings JJ, Khan S, van der Heden van Noort GJ, Melief CJ, Overkleeft HS, van der Burg SH, Ossendorp F, Van der Marel GA, Filippov DV. 2-Azidoalkoxy-7-hydro-8-oxoadenine derivatives as TLR7 agonists inducing dendritic cell maturation. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:2249–2251. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.02.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kurimoto A, Hashimoto K, Nakamura T, Norimura K, Ogita H, Takaku H, Bonnert R, McInally T, Wada H, Isobe Y. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 8-oxoadenine derivatives as toll-like receptor 7 agonists introducing the antedrug concept. J Med Chem. 2010;53:2964–2972. doi: 10.1021/jm100070n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams M, Navabi H, Jasani B, Man S, Fiander A, Evans AS, Donninger C, Mason M. Dendritic cell (DC) based therapy for cervical cancer: use of DC pulsed with tumour lysate and matured with a novel synthetic clinically non-toxic double stranded RNA analogue poly [I]:poly [C(12)U] (Ampligen R) Vaccine. 2003;21:787–790. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00599-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ichinohe T, Watanabe I, Ito S, Fujii H, Moriyama M, Tamura S, Takahashi H, Sawa H, Chiba J, Kurata T, Sata T, Hasegawa H. Synthetic double-stranded RNA poly(I:C) combined with mucosal vaccine protects against influenza virus infection. J Virol. 2005;79:2910–2919. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.5.2910-2919.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma Y, Ross AC. The anti-tetanus immune response of neonatal mice is augmented by retinoic acid combined with polyriboinosinic:polyribocytidylic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13556–13561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506438102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cui Z, Qiu F. Synthetic double-stranded RNA poly(I:C) as a potent peptide vaccine adjuvant: therapeutic activity against human cervical cancer in a rodent model. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2006;55:1267–1279. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0114-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ichinohe T, Kawaguchi A, Tamura S, Takahashi H, Sawa H, Ninomiya A, Imai M, Itamura S, Odagiri T, Tashiro M, Chiba J, Sata T, Kurata T, Hasegawa H. Intranasal immunization with H5N1 vaccine plus Poly I:Poly C12U, a Toll-like receptor agonist, protects mice against homologous and heterologous virus challenge. Microbes Infect. 2007;9:1333–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2007.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Houston WE, Crabbs CL, Stephen EL, Levy HB. Modified polyriboinosinic-polyribocytidylic acid, an immunological adjuvant. Infect Immun. 1976;14:318–319. doi: 10.1128/iai.14.1.318-319.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsumoto M, Seya T. TLR3: interferon induction by double-stranded RNA including poly(I:C) Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2008;60:805–812. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng K, Wang X, Yin H. Small-molecule inhibitors of the TLR3/dsRNA complex. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:3764–3767. doi: 10.1021/ja111312h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsumoto M, Funami K, Oshiumi H, Seya T. Toll-like receptor 3: a link between toll-like receptor, interferon and viruses. Microbiol Immunol. 2004;48:147–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2004.tb03500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoebe K, Beutler B. LPS, dsRNA and the interferon bridge to adaptive immune responses: Trif, Tram, and other TIR adaptor proteins. J Endotoxin Res. 2004;10:130–136. doi: 10.1179/096805104225004031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sen GC, Sarkar SN. Transcriptional signaling by double-stranded RNA: role of TLR3. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005;16:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sioud M. Innate sensing of self and non-self RNAs by Toll-like receptors. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kawai T, Akira S. Antiviral signaling through pattern recognition receptors. J Biochem. 2007;141:137–145. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uematsu S, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and Type I interferons. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:15319–15323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuznik A, Bencina M, Svajger U, Jeras M, Rozman B, Jerala R. Mechanism of endosomal TLR inhibition by antimalarial drugs and imidazoquinolines. J Immunol. 2011;186:4794–4804. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee J, Chuang TH, Redecke V, She L, Pitha PM, Carson DA, Raz E, Cottam HB. Molecular basis for the immunostimulatory activity of guanine nucleoside analogs: activation of Toll-like receptor 7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6646–6651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631696100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gorden KB, Gorski KS, Gibson SJ, Kedl RM, Kieper WC, Qiu X, Tomai MA, Alkan SS, Vasilakos JP. Synthetic TLR agonists reveal functional differences between human TLR7 and TLR8. J Immunol. 2005;174:1259–1268. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gorski KS, Waller EL, Bjornton-Severson J, Hanten JA, Riter CL, Kieper WC, Gorden KB, Miller JS, Vasilakos JP, Tomai MA, Alkan SS. Distinct indirect pathways govern human NK-cell activation by TLR-7 and TLR-8 agonists. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1115–1126. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kimbrell MR, Warshakoon H, Cromer JR, Malladi S, Hood JD, Balakrishna R, Scholdberg TA, David SA. Comparison of the immunostimulatory and proinflammatory activities of candidate Gram-positive endotoxins, lipoteichoic acid, peptidoglycan, and lipopeptides, in murine and human cells. Immunol Lett. 2008;118:132–141. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.