Abstract

Objective

Isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid, or 13-cis-RA) (Accutane), approved by the FDA for the treatment of acne, carries a black box warning related to the risk of depression, suicide, and psychosis. Retinoic acid (RA), the active form of vitamin A, regulates gene expression in the brain, and isotretinoin is its 13-cis isomer. Retinoids represent a group of compounds derived from vitamin A that perform a large variety of functions in many systems, in particular the CNS, and abnormal retinoid levels can have neurological effects. Although infrequent, proper recognition and treatment of psychiatric side effects in acne patients is critical given the risk of death and disability. This paper reviews the evidence for a relationship between isotretinoin, depression and suicidality.

Data Sources

Evidence examined includes: 1) case reports; 2) temporal association between onset of depression and exposure to the drug; 3) challenge-rechallenge cases; 4) class effect (other compounds in the same class, like vitamin A, having similar neuropsychiatric effects); 5) dose response; and 6) biologically plausible mechanisms.

Study Selection

All papers in the literature related to isotretinoin, depression and suicide were reviewed, as well as papers related to class effect, dose response, and biological plausibility.

Data Extraction

Information from individual articles in the literature was extracted.

Data Synthesis

The literature reviewed is consistent with an association between isotretinoin administration, depression and suicide in some individuals.

Conclusions

The relationship between isotretinoin and depression may have implications for a greater understanding of the neurobiology of affective disorders.

1. Introduction

Isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid (RA) (Accutane), is a medication for the treatment of acne that has been associated with psychiatric side effects, including depression, suicide, aggression, and psychosis. Isotretinoin is a retinoid that occurs naturally in the body; retinoids are a group of molecules derived from vitamin A that are essential in regulating the function of multiple organ systems in the embryonic and adult mammal.1 The majority of these functions are performed by the vitamin A metabolite all-trans-retinoic acid (RA), which binds to retinoid receptors to control gene transcription.2 RA has a number of functions, which include regulation of brain development in utero; thus administration of retinoids (including isotretinoin) during pregnancy is associated with neurological side effects.3-5

Isotretinoin works for the treatment of acne in part by inhibiting sebaceous gland function, as well as decreasing keratinization, and suppressing the inflammatory response. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved this drug for the treatment of cystic and nodular acne that is not responsive to other forms of treatment.6-8 Isotretinoin is the same molecule as the transcriptionally active form of RA, all-trans RA, but is altered subtly in shape (i.e. is an isomer) by having one of its double bonds, at the 13th carbon, in cis conformation. 13-cis RA is an endogenous isomer of RA, and can be present at similar concentrations in the plasma as all-trans RA.9 It is the all-trans isomer of RA that has a high affinity for the RA receptor to regulate transcription and the bioactivity of 13-cis RA is most likely achieved via isomerization in tissue to all-trans RA.10, 11 Although this implies the activity of 13-cis RA is less than that of the all-trans isomer, 13-cis RA is more resistant to catabolism and has an elimination half-life of 20 hours, in contrast to only 0.9 hours for all-trans RA, and the peak plasma concentrations for 13-cis RA are reached 2-4 hours after oral dosage.12 The side effect profile of isotretinoin led it originally to be approved only for severe nodular or cystic acne, however dermatologists in the US have frequently prescribed it for less severe acne.8 For instance, in 1999, of patients treated with isotretinoin only around 8% suffered severe acne, while the majority had mild to moderate acne.8

Recently there has been increased attention to the potential psychiatric side effects of isotretinoin.13-26 This is related to the increase in warnings since its first introduction, including the application of a black box warning for suicide, depression, aggression and psychosis, as well as the institution of the IPLEDGE program, a required registry of manufacturers, pharmacists, patients and doctors, established by the FDA in 2005.

In this paper we discuss the evidence for an association between isotretinoin and depression. The neurobiology of retinoids as they relate to affective disorders, which is the basis for the biological plausibility component of assessing the effects of isotretinoin on depression, was extensively discussed in our earlier review.27 The focus of the current paper is the clinical literature supporting an association between isotretinoin, suicide and depression; however we also review new biological research performed since the time of that review as well as studies in humans on the effect of isotretinoin on metabolic pathways associated with depression as well as effects of isotretinoin on the human CNS.

2. Methods

Major searchable indexes including medline and pubmed were searched from 1960 to June 2010 for the key words “isotretinoin”, “retinoids”, “retinoic acid” “depression” “depressive disorders” and “vitamin A”.

3. Results

3.1 Neuropsychiatric Effects of Vitamin A

Referring to the spectrum of retinoids used in the pharmacological treatment of dermatologic disorders, Silverman et al28 in their 1987 paper entitled, “Hypervitaminosis A syndrome: A paradigm of retinoid side effects”, stated that “although each new retinoid is developed with the aim of maximizing specific therapeutic effects and minimizing toxicity, the fact remains that the major side effects of retinoid treatment are those of hypervitaminosis A syndrome. There appear to be no “new” side effects or toxicities encountered during the clinical use of first-, second-, or third-generation retinoids that cannot be found in the hypervitaminosis A literature. Hypervitaminosis A was described as being “most commonly” associated with symptoms of lethargy, depression, cyclothymia, insomnia and hypersomnolence, skin changes, hair loss, headache, bone and joint pain, and liver enlargement. It was also noted that it could cause irritability and frank psychosis. The authors noted that mental symptoms could be subtle and not attributed by the patients to hypervitaminosis A, and therefore clinicians should specifically ask about them. Other retinoids have also been associated with depression (in one case with a positive rechallenge)29 as well as suicidality,30 providing evidence for a “class effect”, or common occurrence of side effects, with the retinoids.

A number of cases have been reported in the literature of mental symptoms associated with vitamin A toxicity, including irritability, depression, lethargy, mood lability, and psychosis.31-39 These symptoms resolve with discontinuation of vitamin A.36, 38, 40-42 For instance, Restak40 reported a case of vitamin A toxicity associated with the development of aggression, personality changes, and depression, which resolved with discontinuation. McCance-Katz and Price43 reported a case of chronic vitamin A intoxication which was associated with a one-year history of depressed mood, poor concentration, tearfulness, and guilty rumination. The patient had no prior history or family history of depression. He also had fatigue and fears of cancer with a Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D, a quantitative measure of depression) score of 29, indicating severe depression. Four weeks after discontinuation of vitamin A the HAM-D Score dropped to 6, and the patient was completely normal two months after treatment. The authors concluded that this was a case of vitamin A-induced major depression. Fishbane et al44 reported two cases of vitamin A toxicity where blood levels confirmed high concentrations of vitamin A; these cases were associated with neurological effects of drowsiness and inability to grasp objects in one patient, and in the second patient psychotic symptoms of insects crawling over the body with the bizarre behavior of trying to cut off his son’s hair because he thought insects had infested his son’s body. There was no prior history of psychiatric disorder and the symptoms resolved with the discontinuation of vitamin A. Haupt 45 also reported a case of psychosis with vitamin A intoxication. Frame et al31 described a 16 year old boy with emotional lability and loss of appetite associated with taking high doses of vitamin A. After discontinuation of the supplement the symptoms resolved. Bifulco reported a 52 year old woman who took daily high doses of vitamin A. She developed insomnia, loss of weight and appetite. She became “completely disinterested in her surroundings and was found to brood all the time.” One week after discontinuation of vitamin A her symptoms resolved.

One of the more unusual cases of possible vitamin A overexposure is a syndrome known as pibloktoq suffered by people living within the Arctic Circle. This syndrome includes symptoms ranging from depression to explosive outbursts. Landy46 proposed that this syndrome resulted from excess consumption of vitamin A due to a diet that included polar bear liver as well as various internal organs from other indigenous animals, all of which contain very high vitamin A levels. There are possible parallels with symptoms reported in Arctic explorers who, after consuming polar bear liver, exhibited symptoms including headaches nausea, drowsiness, and behavioral changes. Further, repeated ingestion resulted in a return of the symptoms, indicating a challenge/dechallenge effect.46 Such behavioral effects of vitamin A are not surprising considering the fact that there have been multiple case reports of vitamin A intoxication associated with the neurological disorder of benign intracranial hypertension, or pseudotumor cerebri.33, 37, 47-54

3.2 Suicide and Depression in Acne Patients Treated with Isotretinoin

3.2.1 Individual accounts of depression following isotretinoin treatment

There are a number of cases reported in the literature of isotretinoin treatment being associated with depression and suicide, as well as psychosis and aggression. A list of case reports are described in Table 1. One patient was an 18 year-old man who developed depressed mood, loss of interest, apathy, insomnia, anergia, anhedonia, and irritability, with feelings of guilt and loss of work and social function after two months of isotretinoin treatment. This patient attempted suicide on the fifth month of isotretinoin treatment. At the time of psychiatric evaluation his HAM-D score was 31, representing clinically significant depression. He had been receiving trazodone for the prior six weeks without benefit, and was still on isotretinoin at the time of the suicide attempt. After discontinuation of isotretinoin and administration of fluoxetine, there was an improvement in mood over 4 weeks with a Ham D score of five at follow up. A second patient was a 20 year old women treated with isotretinoin who developed depression, tearfulness, suicidal ideation, feelings of worthlessness and agitation, anergia and anhedonia, irritability and anger. Her HAM-D score was 29. The patient also had symptoms of headache. Following supposed discontinuation of isotretinoin and treatment with imipramine and several other antidepressants there was a poor response. She later revealed that she had been surreptitiously continuing the isotretinoin, but after she finally stopped, and fluoxetine was started, she had a reduction of symptoms within two weeks and a follow-up HAM-D score of 8. A third patient was reported to have several months of symptoms of depressed mood, irritability, aggression, agitation, decreased sleep, decreased appetite, reduced concentration, anhedonia, and early morning awakening that began during a course of isotretinoin therapy. These symptoms resulted in the breakup of her marriage. At the time of the evaluation she continued to have depressive symptoms even though she had been off isotretinoin for 10 months. Her Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) score was 26, consistent with clinically significant depression, and fell to 9 five weeks after administration of an antidepressant, indicating successful treatment of depression. The authors described three other cases that resolved with discontinuation of isotretinoin 17, 55

Table 1. Case Reports and Case Series of Depression and Suicide Associate with Isotretinoin.

| Author | Number | Depression | Suicidal | Psychosis | Violence & Aggression |

Past Psych History |

Onset | De challenge |

Re challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazen 83 | 6/110 | ++++++ | + (5−) | 2 wks | 6 | ||||

| Bruno 84 | 10/94 | ++++++++++ | NR | 1 month | 10 | ||||

| Lindemayr 86 |

1 | + | + | NR | 2 mos | ||||

| Burket 87 | 1 | + | NR | 20 wks | + | ||||

| Bigby 88 | 3 | +++ | + | NR | 6 wks, 2 mos |

+ | |||

| Villalobos 89 |

1 | + | NR | 2 wks | + | + | |||

| Scheinmann 90 |

7/700 | +++++++ | + | Irritability | ++ (5−) | During treatment |

+++++++ | + | |

| Hepburn 90 | 1 | + | + | + | NR | 2 mos | + | ||

| Gatti 91 | 1 | + | + C | NR | 1 mo after Rx |

||||

| Bravard 93 | 3 | +++ | +, +C | − − − | 2 mos, 3 mos (2) |

+ | |||

| Duke 93 | 2 | ++ | + | + | + | − − | 1 mo (2) | ++ | |

| Byrne 95 | 3 | +++ | ++ | − − − | During treatment |

+++ | |||

| Aubin 95 | 1 | + | NR | 1 day | |||||

| Cotterill 97 | 2 | +C, +C | NR | 2 mos | |||||

| Byrne 98 | 3 | +++ | + | +++ | + (2−) | During Rx , 2 mos, 10 mos after Rx |

++ | ||

| Cott 99 | 1 | + | + | + | 4 wks | + | |||

| Middelkoop 99 |

1 | + | + C | NR | During treatment |

||||

| Hull 00 | 5/121 | +++++ | + (4−_ | 2 wks | |||||

| Pitts 00 | 41 | 41 | NR | During Rx |

41 | 41 | |||

| Ng 01 | 1 | + | + | + | − | 2 wks | + | + | |

| Wysowski 01 |

431 | 394 | 37 C | 8 | During treatment |

||||

| Ng 02 | 5/174 | +++++ | NR | During treatment |

+ | ||||

| Robusto 02 | 1 | + | NR | During treatment |

|||||

| Van Broekhaven 03 |

1 | + | + C | + | During treatment |

||||

| La Placa 05 | 1 | + | + | NR | 5 wks | ||||

| Barak 05 | 5/500 | +++++ | +++ (2−) |

3-11 mos | ++++ | ||||

| Bachmann 07 |

1 | + | − | 6 mos | + | + | |||

| Cohen 07 | 2/100 | ++ | NR | ||||||

| Schaffer 10 | 9/10 | +++++++ | +++ | NR | 4-20 wks | ++++++++ |

C=committed suicide

+=number of subjects within this report that had the associated effect.

NR=not reported

Bravard et al56 described a 17 year old with a prior history of depression treated with isotretinoin at 0.5 mg/kg/day. At the time of treatment initiation he was free of signs of depression. However, following a further four months of treatment he tried to commit suicide by shooting himself. He reported that before the suicide attempt he had two months of fatigue, insomnia, and unhappy thoughts. In another case a 17 year-old man without prior psychiatric history who was treated with isotretinoin at 1 mg/kg/day developed growing fatigue which forced him to stop sports, and after four months he developed unhappy thoughts and asked to stop treatment. It was later learned that he committed suicide three months after stopping treatment. Another young woman with no psychiatric history began having crying spells after three months of isotretinoin treatment that lead to cessation of treatment.

Not all cases of depression concurrent with isotretinoin treatment are associated with suicidal ideation, but can include a multiplicity of unusual, sometimes extreme, behaviors. For instance,57 a 15-year-old girl who was previously without psychiatric history developed strange behavior one month after initiating treatment with 1 mg/kg/day of isotretinoin, including cutting the hair off of one side of her head, showing personality changes to her family, and leaving home. At that time she developed sleep disturbances and irritability, and became sullen and withdrawn. At that point the medication was stopped because of symptoms of depression. Two days later she threatened to cut her wrists and set fire to her clothes. After several months of being off of the medication she was reported to be normal again. The authors reported another case of depression that alleviated with cessation of the drug. A number of other cases, most of which resolved with discontinuation of treatment (de-challenge) and some that returned with re-challenge, have been described in the literature and are not described in detail here. These reports are summarized in Table 1.16, 17, 55-81

Isotretinoin has also been associated with symptoms of mania and psychosis.62, 68, 82 Two male and three female acne patients with no prior history of psychiatric diagnosis and with a mean age of 19 reported “manic psychosis” with their symptoms developing after a mean of eight months [range 3-11 months] following start of treatment with isotretinoin. Four patients had an improvement in symptoms with antipsychotic treatment while one was treated with antipsychotics without a response. Three patients attempted suicide at some time after initiation of treatment.78 This drug may also exacerbate pre-existing psychiatric conditions;62, 68, 76 for instance, Schaffer et al81 examined the charts of 300 patients with bipolar disorder. Ten of the patients were found to have been treated with isotretinoin. Of those, 9/10 had an exacerbation of their psychiatric symptoms with treatment, and three developed suicidal ideation. In the 9 patients, 6 had a mixed depressive and manic response, 1 was hypomanic, and 2 depressed. Symptoms began from 4-20 weeks after initiation of therapy, and resolved with discontinuation in all but one.

The evidence from the literature hence shows that isotretinoin treatment affects individuals in differing ways, but even though the diversity and severity of symptoms vary, all have adverse effects on the mental well being of these individuals. The physiological effects of isotretinoin are presumably on pathways that are part of the pathology of these psychiatric conditions, but with the most prominent effects being on those pathways that engender depression.

3.2.2 The evidence of an isotretinoin/depression association from group studies

In one series of 121 isotretinoin-treated patients, 5 (4%) developed persistent depression; 31 (26%) developed fatigue.70 In another series, 6/110 (5.5%) of isotretinoin treated patients (1-2 mg/kg/day) developed symptoms of depressed mood, crying spells, malaise and forgetfulness.59 Of these six patients, four were women and two men with a mean age of 28 while one patient had a prior history of depression. Isotretinoin was discontinued in one patient because of depression and forgetfulness. In another report, 10/94 (11%) of isotretinoin treated patients developed depression. In patients treated with high doses (>.75 mg/kg/day), 7% reported insomnia, 22% fatigue, 11% headache, 7% weight loss, 2% impotence, and 9% loss of libido, while no subjects with untreated acne reported these side effects.58 In a clinical trial of 700 patients treated with isotretinoin, seven developed depression; two were male and five female and their mean age was 32.63 The diagnosis of depression was made based on patient self-report with confirmation by a psychiatrist in 3 of the patients; in the other 4 patients the symptoms resolved with discontinuation of medication before there was a chance for a psychiatric interview. In 5 out of 7 patients the symptoms of depression developed during the first course of treatment with the medication; the other patients had one or two prior courses of treatment with isotretinoin. Patients reported symptoms of depression following administration of isotretinoin including fatigue, irritability, sadness, decreased concentration, crying spells, loss of motivation, forgetfulness and loss of pleasure. One patient had suicidal ideation. Symptoms resolved in all cases after discontinuation of medication within 2-7 days.

In another study, 5/174 isotretinoin treated versus 0/41 antibiotic treated patients developed depression and dropped out of the study or were withdrawn from treatment by their dermatologists. Two of the patients who developed depression on isotretinoin were evaluated by a psychiatrist and felt to have concurrent psychosocial stressors while three refused to be evaluated by a psychiatrist. Of these three, no concurrent stressors were identified in two, and one had a remission of symptoms with discontinuation of isotretinoin.74. A study of members of the Israeli armed services looked at 1419 conscripts who had used isotretinoin83 and found a statistically significant increase in suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts as well as a significant increase in mental health services utilization in those individuals compared to controls.

Not all studies though have shown a clear link between isotretinoin use and depression. In 132 subjects treated with isotretinoin or antibiotic, scores on the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale, a measure of depression, went from 8.1 to 6.6 in the isotretinoin group and 9.3 to 8.4 in the antibiotic group. Although no statistically significant changes with treatment were reported, the authors nevertheless stated that “treatment of acne either with conservative treatment or isotretinoin was associated with a decrease in depressive symptoms”.84 In a study of 45 Turkish patients treated for acne with 0.5-1 mg/kg for 16 weeks there was no change in depression as measured with the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale 85. Only 23 patients completed treatment. Kaymak et al studied 100 Turkish acne patients before and after treatment with isotretinoin at .75-1.0 mg/kg.86 Patients had an increase in depressive scores measured with a Turkish version of the Hamilton Depression Scale after three months of treatment with one patient developing clinically significant depression. Depression ratings decreased from three to six months of treatment. The authors suggest that these changes might be part of a clinical effect of isotretinoin, however they differ from other accounts of isotretinoin associated depression in that depression resolves while the subject is still using isotretinoin. In a second study from this group, acne patients were given either isotretinoin (N=37) or topical treatment (N=41). After four months, a quantitative measure showed better quality of life in the isotretinoin group, and at four months there were also better scores for depression as measured with the BDI.87 Rehn et al88 studied 126 acne patients treated with isotretinoin. There was no increase in depressive symptoms in the group as a whole as measured with the BDI. One patient attempted suicide. Kellett and Gawkrodger89 studied 33 patients at baseline and after 8 and 16 weeks of isotretinoin treatment. There was no effect of isotretinoin on depression, either increased or decreased, as measured with the Beck Depression Inventory.

Strauss et al 90 studied 300 acne patients given 1.0 mg/kg isotretinoin and 300 patients given 0.4 mg/kg micronized isotretinoin. Eleven patients in the micronized isotretinoin group had psychiatric side effects, and four had to drop out for depression and/or mood swings, with the symptoms improving with cessation of treatment. One patient in the regular isotretinoin group had depression requiring cessation of treatment which resolved after removal of the drug. The apparently higher rate of depression in the group receiving micronized isotretinoin raises the question of whether the higher bioavailability of isotretinoin in this form is associated with an increased risk of depression.

Schulpis et al91 studied 38 patients with cystic acne before and after 30 days of treatment with 0.5 mg/kg isotretinoin and compared them to 30 controls. Subjects were assessed with the Profile of Mood States, Hopkins Symptom Checklist, and NIMH Mood States Questionnaire (MSQ). Although cystic acne patients had elevated levels of depression and anxiety at baseline compared to controls, isotretinoin had no effect on symptoms of depression. Only the NIMH MSQ showed significant reductions in anxiety with treatment.

Cohen et al80 studied 100 acne patients treated with isotretinoin and 41 treated with oral antibiotics and 59 treated with topical creams. Subjects were evaluated before and after treatment with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale and the Zung Depression Status Inventory. Zung Depression scores went from 30 to 31.5 in the group as a whole, with no significant difference between groups. Two patients in the isotretinoin group became depressed with treatment as defined as a CES-D score going above 15; no one in the control group became depressed. The authors failed to report Zung score before and after treatment by treatment group, although the p value reported of 0.2 suggested that with a larger sample size the difference could have been significant.

Thus, there is disparity between studies, likely due variability in techniques and limitations in sample size. Analysis of the four largest studies though showed an association between isotretinoin treatment and depression that ranged from 1%63 to 2%80 to 4%70 to 6%59 to 11% of patients.58 Some of the studies that showed a lower frequency of association included results that relied on self-reporting, and it has been described that subjects report behavioral changes such as decreased school or work performance or impulsivity with less frequency than do family members.92 In studies that report no difference in mean scores on measures of depression, it is possible that the fact that most people were not affected by the drug, obscures the fact that the drug is affecting a select number. Overall these studies do not have large enough sample sizes to address the question at hand, given the fact that most patients taking isotretinoin do not develop depression. Nevertheless, there is a consistent pattern of cases of depression developing in a sub-population of patients on isotretinoin in these studies.

3.2.3 The evidence of an isotretinoin/depression association from large databases studies

Studies analyzing large databases have been used to assess the relationship between isotretinoin and depression. In one study funded by the manufacturer of isotretinoin,93 a retrospective study from a database of 2,281 patients who had used isotretinoin and/or an antidepressant found that patients treated with isotretinoin were no more likely to receive antidepressant than those not using isotretinoin. However this study is limited by the possibility that dermatologists may stop isotretinoin in the setting of depression without antidepressant treatment, or that patients may refuse psychiatric referral or treatment. In the study of Ng and colleagues{Ng, 2002 #2511 described above, this was in fact the case of all five patients who developed mood changes on isotretinoin. In another study funded by the manufacturer,15 medical data was examined for the association between isotretinoin use and the frequency of suicide, attempted suicide, and “neurotic and psychotic disorders” in patients in the UK and Canada; there was not found to be an increase in these parameters with isotretinoin treatment. Wysowski94 pointed out limitations of this study, including the lack of standardized diagnosis or inclusion of data on psychoactive drug treatment, lack of patient interview for depression, under-ascertainment of suicides (the death certificate data was not examined), lack of data on acne severity, lack of control group, absence of information about length of treatment, differences in prescribing between the U.K. and Canada, and the limited sample size for the U.K. sample. Another study involved an analysis of the United Healthcare database. Although a published abstract from 2001 showed no increase in coding for depression in isotretinoin users,95 if instead coding for diagnosis of depression and/or antidepressant prescription is used to compare control and isotretinoin treated groups then a statistically significant increase in depression is evident in isotretinoin prescribed patients.

Azoulay et al studied a group of patients in Quebec who between 1984 and 2003 had obtained an isotretinoin prescription. Cases were defined as individuals who were diagnosed or hospitalized for depression and who filled a prescription for an antidepressant within 30 days after the diagnosis or hospitalization. Subjects who received an antidepressant in the prior 12 months were excluded. Rates of exposure to isotretinoin in the five months before the event were compared to a five month control period. Out of 30,496 subjects examined, 126 met criteria. The adjusted relative risk of depression after receiving isotretinoin was 2.68 (CI = 1.10-6.48), providing a strong case for the increased risk of depression with isotretinoin treatment.96

An analysis of reports of adverse drug reactions (ADR) was performed from data from Roche, WHO and the United Kingdom Medicines Control Agency (MCA) from 1982-1998.69 This found that the association between isotretinoin and suicides or psychiatric adverse events is much greater than that of antibiotics when used for acne treatment; 60% of all adverse psychiatric events associated with acne treatment were coupled with isotretinoin use despite the fact that antibiotics are employed more frequently than isotretinoin. Detailing the numbers from WHO, there were 47 reports of suicide, 67 attempted suicides and 56 cases of suicidal ideation.69 Description of the reported psychiatric symptoms included mood swings, depression, amnesia, anxiety and insomnia as well as suicide.

The FDA reported 431 ADRs for isotretinoin between the years 1982 and 2000 16. Of these 37 had committed suicide, 110 were hospitalized for either depression, suicidal ideation, or suicide attempts while 284 suffered depression without hospitalization. The Adverse Events Reporting System (AERS) database placed isotretinoin as the 5th ranking drug for reports of serious depression, 4th ranking for depression. For attempted suicide isotretinoin ranks number 10 and it is the only nonpsychiatric drug that ranks in this top ten list. A study of the ADRs from the FDA also suggests a challenge/dechallenge effect for isotretinoin with remission of depression resulting between cessation and restarting the drug. When the 2002 FDA reports were examined 3104 cases of psychiatric adverse effects were found for isotretinoin, 173 of which were suicides.97

A 2004 analysis of the FDA’s Medwatch database showed that between 1989 and June 2003, there were 216 reported drug-linked suicides in under 18 year olds. Of these, 72 suicides were linked to Accutane.98 The FDA states that MedWatch reflects as few as 1% of actual adverse drug events,16 meaning that 72 Accutane suicide reports could represent as many as 7,200 suicides.

A number of drug regulatory bodies from countries outside of the US have reported psychiatric side effects of isotretinoin administration. For example, the Canadian Adverse Drug Reaction Monitoring Program (CADRMP) reported 16 psychiatric reactions with isotretinoin including depression (5), aggressive reaction (4), emotional lability (4), irritability (3), suicidal tendency (3), amnesia (2), abnormal thinking (1), aggravated depression (1), manic reaction (1) and suicide attempt (1). In the reports that indicated an outcome, 7 patients recovered with discontinuation of isotretinoin, 3 recovered with residual effects, and 1 had not yet recovered at the time of reporting.99 222 adverse events were reported to Health Canada between 1983-2002, and 56 (25%) of these were psychiatric adverse events and included depression and suicidal ideation.100 An analysis of a subset of Canadian ADRs reported in children from 1998-2002 showed that isotretinoin was the medication most commonly associated with ADRs 101. Of 1193 reported ADRs, 56 were for isotretinoin, including two deaths and 26 cases of psychiatric ADRs. The Australian Adverse Drug Reactions Committee, between 1985 and 1998, catalogued 129 reports of adverse reactions, 12 of which included depression. In four cases there were symptoms of psychosis. Three patients had suicidal thoughts, two attempted suicide and one completed suicide. Three recovered with withdrawal of isotretinoin and one with antidepressant.102 The Irish Medicine Boards, between 1983 to 1988, received 6 reports of depression associated with isotretinoin treatment, one of which was suicide 103. The Australian ADR Committee, up to June 2005, received 21 reports or either suicide attempts or ideation with isotretinoin use, one which led to a Coronial investigation.104. The Danish Medicine Agency, between 1997 and 2001, recorded 34 psychiatric adverse events with isotretinoin treatment, 23 of which included depression.105

Studies from databases allow trends to be observed in a large population and a number of these analyses link the use of isotretinoin to an increased occurrence of depressive behavior and suicide. The lack of a finding of an association between isotretinoin in some of the studies may be due to the lack of standardized diagnosis, lack of patient interview for depression, under-ascertainment of suicides, and the absence of control groups. The relatively small increase in risk of depression, for instance from the Azoulay et al study which found a 2.68 fold rise96, likely accounts for this increase not being found significant in all studies.

3.2.4 Positive behavioral effects of isotretinoin – improved self-image does not cure depression

The dermatology literature has frequently emphasized the potential for positive behavioral effects with isotretinoin because of the effectiveness of this drug in clearing acne.106-109 Although acne is associated with a decrease in self-esteem, anxiety about appearance and unhappiness about appearance,110-112 studies have not been able to demonstrate a correlation between symptoms of clinical depression and objective severity of acne, or an improvement in clinical depression with treatment. Furthermore, although studies have shown improvements in self esteem and anxiety about appearance with acne treatment, they have not clearly shown an increase in actual cases of depression based on standardized structured clinical interviews in non-cystic acne patients. For instance, studies have not shown an association between dermatological conditions and psychiatric disorders in long term care psychiatric patients.113

Some studies114 have found higher levels of trait and state anxiety in cystic and non-cystic acne compared to normal controls or higher levels of social anxiety in patients with severe acne.115 However, a larger number of studies have not been able to show abnormal levels of anxiety in acne patients or a correlation between acne severity and anxiety measured with the STAI116 or other measures of psychological distress or quality of life.117-122 Studies have not shown a significant effect of isotretinoin treatment on measures of anxiety and depression,20, 123, 124 or have shown an only modest effect on only one of multiple measures of anxiety and depression.122, 125

A recent study looked at 244 high school students at baseline and at 6 and 12 months; there was no relationship between presence of acne or acne severity and measures of depression or anxiety.126 Furthermore there was no evidence of a causal role for acne in the development of symptoms of depression or anxiety.

Some of the dermatology literature, however, has selectively cited studies to support the idea that acne causes depression and that treatment leads to an improvement in depression. For instance, one of the most cited studies112 involved only ten patients with acne assessed with a non-structured psychiatric interview and measures of depression with no control group and no statistics reported. Two patients were reported as no longer having depression after treatment while depression persisted in one. Another report from these authors127 involved 480 dermatologic patients including 72 with non-cystic acne. Six percent of the acne patients reported suicidal ideation, cited as higher than the 3% of general medical patients reporting suicidal ideation. Patients with acne had higher CRSD scores than patients with other dermatologic conditions (atopic dermatitis, alopecia, outpatient psoriasis), with the exception of inpatients with psoriasis, a difference that was statistically significant. However this study did not involve non-medical controls.

In short, these studies provide a strong indication that there is an improvement in self-image following isotretinoin treatment for acne. However they do not support the conclusion, often repeated in the dermatology literature, that acne results in clinical depression, or that treatment of acne with isotretinoin leads to an improvement in clinical depression.

3.2.5 The temporal relationship between isotretinoin treatment and depression

The fact that the development of depression is temporally related to the initiation of treatment with isotretinoin supports the causal role that isotretinoin plays in the development of depression. Most cases of isotretinoin associated depression developed after 1-2 months of treatment.13, 14, 17, 55-65, 68-70, 72, 73, 75, 77, 82, 92 In other cases depression or suicide occurred at later stages of treatment, around 2-4 months after drug commencement. Temporal analysis of these reports though can be difficult as these details are not always provided and symptoms possibly not fully reported.55, 56, 63, 67, 73, 74, 78 This may explain the case of Gatti65 who developed depression and social problems one month after discontinuation of a four month course of treatment and killed himself three weeks later. Similarly Bravard56 described a case of depression after three months of treatment with completed suicide three months after the end of treatment. From the case reports and data of Wysowski73 it appears there is a longer lag time between initiation of isotretinoin therapy and committed suicides (three months) than the first onset of depressive symptoms (one month), possibly because patients suffer in silence with depression for some time before they commit suicide. One case of suicide on the first day of isotretinoin treatment does not fit the profile of other cases and was unlikely to have been related to the drug.66

Overall, review of these cases indicates that depression and suicide do not follow immediately after treatment but commonly 1-2 months after commencement, sometimes with a longer delay. This suggests that the biological mechanism may not be via immediate influence of 13-cis RA on a crucial neurotransmitter or other signal pathway but may be through a secondary system or possibly alteration of neuroplasticity or metabolic process known to be influenced by RA, as previously described 27 and discussed below in section 3.3. Alternatively, changes in neurochemical systems may occur more rapidly, but it may take weeks or months before a behavioral effect is seen, as is the case with the mechanism of action of antidepressants.

There have been multiple reports in the literature of depression associated with isotretinoin use that resolved after discontinuation of the drug, and in some cases returned with re-introduction of the drug.55-57, 61, 62, 74 For instance, the FDA have 41 reports of positive challenge/dechallenge/rechallenge with isotretinoin128 and 67% of these are not associated with a psychiatric history. In one series of seven cases of depression associated with isotretinoin treatment63 symptoms resolved in all cases after discontinuation of medication within 2-7 days. One patient of this series returned to isotretinoin treatment and, within 3 months of this, exhibited a recurrence of depression.78 Ng et al72 described the example of depression in a 17 year old male two weeks after commencing isotretinoin treatment and who showed improved symptoms following a reduction in isotretinoin dose as well as application of an antidepressant (sertraline). When the dose of isotretinoin was increased again the depressive symptoms returned, in spite of a clearing of acne, with an associated suicide attempt. When the dose was stopped the depressive symptoms rapidly resolved. Bachmann et al79 reported a case of a 16 year old boy who developed symptoms of depression that resolved after discontinuation of isotretinoin. Review of his history showed that he had an episode of isotretinoin-associated depression that resolved three years earlier after discontinuation of the drug.

In another series several cases were described,16 including a 19 year old with no psychiatric history who during a 3-4 month course of isotretinoin therapy developed personality changes, mood swings, and depression. After completion of treatment he returned to normal. The patient started a second course of isotretinoin treatment at a later date. Again he experienced the same symptoms, but returned to normal at the end of four months of treatment. Sometime later he started a third course of treatment. This time his symptoms recurred and persisted after the end of isotretinoin treatment. A year later he was referred for counseling. In a second case an 18 year old man with no history of mental disorder received 1.1 mg/kg/day of isotretinoin. After 29 days he experienced depression, loss of interest in daily activities, and decreased school performance. Isotretinoin was stopped and symptoms cleared in 8 days. The drug was started at 0.5 mg/kg/day and the symptoms returned after five days. Isotretinoin was stopped and the symptoms cleared in 7 days. He later was treated at the lower dose without recurrence of symptoms. The report concluded that multiple lines of evidence pointed to an association between isotretinoin treatment and depression.

These examples of depression resulting from isotretinoin use, remission on discontinuation of the drug and in some cases the return of depression on re-introduction of isotretinoin, make for a very strong case for their link in some individuals. It also implies that, although the promotion of depression by isotretinoin is relatively slow, the biological change can, in some cases, be restored to normal when the drug is removed.

3.2.6 Dose response relationship between isotretinoin treatment and depression

The fact that higher doses of isotretinoin are associated with a greater risk of depression is further indication that isotretinoin is responsible for the development of depression. For example, when doses were as high as 3 mg/kg/day, which is 3-6 times higher than the standard dose, then 25% of patients92 exhibited depression, contrasting with the 3-4% that is described in several other reports. One case involved a lawyer who was no longer able to argue cases in court, and a man who precipitously divorced his wife. The author concluded that the “psychological changes may be dose related.” It would also be predicted that a decrease in isotretinoin dose would reduce symptoms of depression and a “possible dose response” was evident in six cases where isotretinoin dose was reduced and depression symptoms declined.128 In another case72 symptoms of depression with isotretinoin improved with reduction of isotretinoin dose combined with sertraline treatment. When the dose of isotretinoin was increased again the depressive symptoms returned, in spite of a clearing of acne, with an associated suicide attempt. When the dose was stopped the depressive symptoms rapidly resolved. In another study higher doses of isotretinoin were associated with symptoms of depression including depressed libido (9% of high dose versus 2% of low dose), impotence (2% versus 0%), and weight loss (7% versus 0%). These symptoms were higher than a group of acne patients not on isotretinoin, who reported none of these symptoms.58

These studies provide some evidence for a dose response effect for isotretinoin and psychiatric side effects, where higher doses are associated with more side effects. A dose response has been established related to isotretinoin for other non-psychiatric side effects, like mucocutaneous side effects129 using dosages of 1.0-3.3 mg/kg/day. However, these early studies of different dosing levels did not use specific measures of behavior, and current practice employs lower doses in a more restricted range (0.5-1 mg/kg/day). This combined with the fact that cases of depression are not common makes it difficult to measure a dose response relationship for psychiatric side effects related to isotretinoin.

3.3 Biological Plausibility

In order for a drug to cause a particular adverse event, there needs to be a plausible mechanism of action. Since depression is a disorder that is based in the brain, isotretinoin must have an effect on brain function.27

We will first briefly describe how RA influences gene expression in cells of the nervous system, then describe new results on RA signaling in the hypothalamus, a brain region linked with depression. Finally, two potential metabolic pathways associated with depression, and which are disrupted by isotretinoin, are discussed.

3.3.1 Retinoic acid signaling

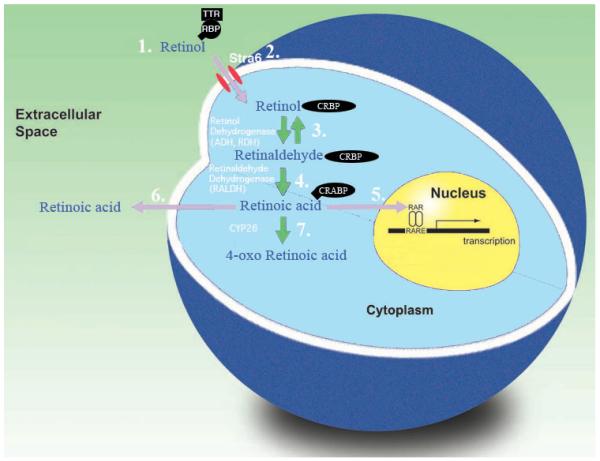

As previously described, all-trans RA is an endogenous regulator of gene expression acting via specific receptors that function as ligand (in this case RA) activated transcription factors. The dietary substrate of RA is vitamin A, stored as a reservoir of retinyl esters in the liver. These retinyl esters can be hydrolyzed and the resulting retinol released, circulating bound to retinol binding protein (RBP) and transthyretin (TTR). The events that lead to activation of gene expression in a cell are shown in figure 1. Uptake of retinol by target cells is facilitated by the RBP receptor Stra6.130, 131 Intracellular retinol is bound to cellular retinol binding protein (CRBP) before being oxidized to retinal by the ubiquitous enzymes alcohol dehydrogenase or retinol dehydrogenase. Retinal is further oxidized to RA by retinaldehyde dehydrogenase (RALDH) an enzyme that is only expressed in regions where RA is required. RA is bound to cellular retinoic acid binding protein (CRABP) and translocates to the nucleus where it binds to retinoic acid receptors (RAR) that form heterodimers with retinoid X receptors (RXR). These ligand-receptor complexes are bound to the retinoic acid response elements (RARE) located in the promoter regions of certain genes and promote transcription. This signaling system can be inactivated by the P450 enzyme CYP26 that generates further oxidized derivatives including 4-oxo RA. A balance of RA synthesis and catabolism in the cell maintains the correct levels of RA regulated transcription. Exposure of the cells to isotretinoin, which is isomerized in tissue to the active all-trans RA10, 11, will destabilize this balance and result in inappropriate gene transcription.

Figure 1.

Cellular retinoic acid signaling. 1. Retinol in the circulation is bound to retinol binding protein (RBP), which itself is bound to transthyretin (TTR). 2. Retinol enters the cells which may be assisted by the membrane protein Stra6. 3. Retinol in the cell is bound by cellular retinol binding protein (CRBP) and can then be oxidized to retinaldehyde by an alcohol dehydrogenase or retinol dehydrogenase in a reversible reaction. 4. Retinaldehyde is oxidized irreversibly to RA by a retinaldehyde dehydrogenase. 5. RA may then enter the nucleus to bind to RA receptors (RAR) to activate transcription or 6. leave the cell to act on adjacent tissue. 7. Alternatively the system may be turned off by further oxidation of RA to oxidative metabolites including 4-oxo RA.

3.3.2 Retinoic acid function in the hypothalamus

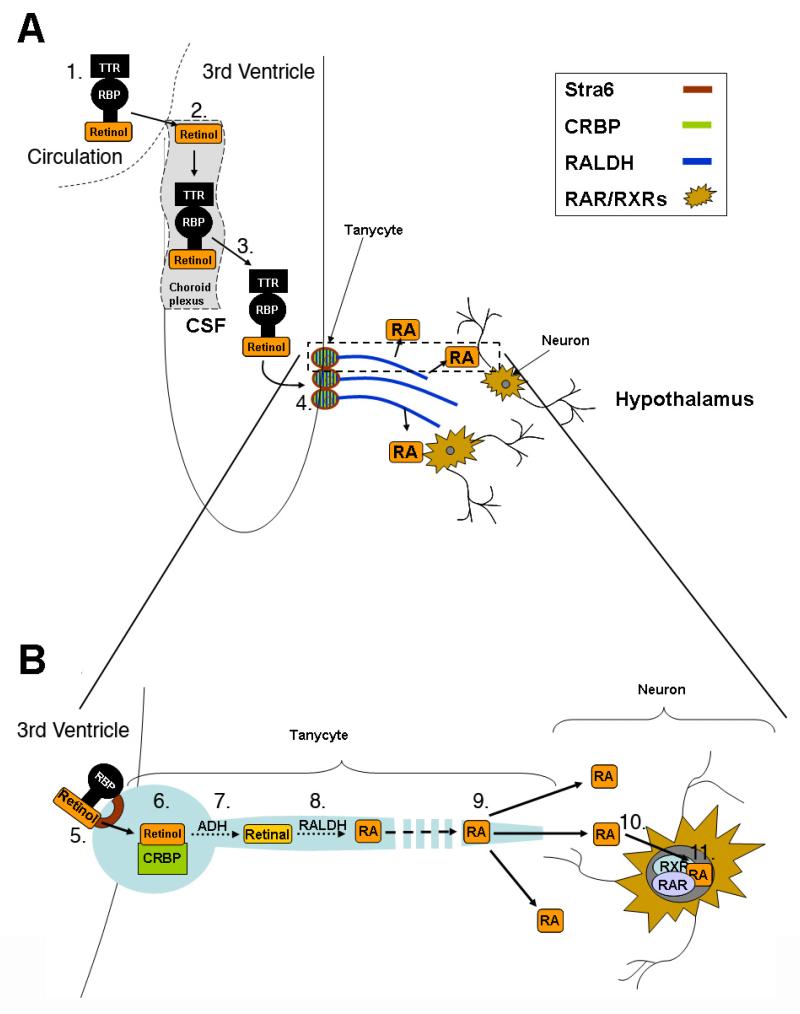

Brain regions that are endogenously regulated by RA, and which may be disrupted by isotretinoin to potentially promote depression, have been described in our previous review and include the striatum, hippocampus and frontal cortex.27 An area of the brain, however, that has been little considered for retinoid action is the hypothalamus. The hypothalamus is the hormone regulatory center of the brain and, as part of the hypothalamus/pituitary/adrenal (HPA) axis, is a central component in the response to stress. Hyperactivity of this system is a reproducible finding in depression. Although several elements of the RA synthetic pathway had been previously identified in the hypothalamic regions of Siberian hamsters as a measure of photoperiodic change,132 it was not recognized that endogenous RA could be synthesized and function in this region. Shearer et al (2009)133 identified the crucial RA synthetic RALDH enzymes in the processes of tanycytes, the specialized ependymal cells that provide a boundary between the CSF in the third ventricle and neural cells of the hypothalamus where RAR’s and RXRγ receptors are found to reside. As illustrated in figure 2, retinol present in the CSF can be taken up by the tanycytes, CRBP carrying this substrate within the cell to the RA synthetic enzymes. RA can be released into the hypothalamus via the long processes of the tanycytes that reach into the hypothalamus and regulate a number of genes including the RA receptor RARβ as well as ACTH.133 It was found in this same study that photoperiod regulates RALDH in tanycytes as well as RAR/RXR’s in the hypothalamus, therefore showing changes in RA signaling driven by seasonal changes. Given that seasonal affective disorder is a form of depression driven by seasonality there is the potential for RA to influence this disorder.

Figure 2.

RA synthesis and action in the hypothalamus.

A. Transport of retinol into the CSF. 1. Retinol circulates in the blood in a bound complex with retinol binding protein (RBP) and transthyretin (TTR). 2. Retinol is taken up by the choroid plexus. 3. The choroid plexus synthesizes RBP and TTR and these are exported into the CSF with retinol. 4. Retinol in the CSF carried by RBP and TTR is taken up by tanycytes B. Detailed view of RA synthesis by tanycytes and release of RA to act on hypothalamic neurons 5. Stra6 receptors present in the membrane of the tanycyte cell bodies lining the third ventricle facilitate the uptake of retinol into these cells. 6. Intracellular retinol is bound to cellular retinol binding protein (CRBP) and 7. Retinol is converted to retinaldehyde by an alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). 8. A retinaldehyde dehydrogenase (RALDH) oxidises retinaldehyde to RA and 9. RA is released by the long tanycyte processes into proximal areas of the hypothalamus. 10. RA enters hypothalamic neurons and 11. RA receptors in these neurons convey the RA signal to regulate gene transcription.

One particular RA regulated gene in the hypothalamus that may provide a link between RA and depression is corticotrophin-releasing hormone (CRH)134 a key regulatory factor in the HPA axis135 which may contribute to HPA axis hyperactivity in depression.136, 137 Chen et al have described increased density of RARα expressing cells in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of patients with affective disorder138 and this receptor colocalized with those neurons expressing CRH. Similarly, in a rat model of depression, RARα levels were raised in the PVN.138 These results further emphasize the importance of RA in the hypothalamus and the potential for overlap between RA regulated hypothalamic pathways and those that underlie depression. In particular, increased RA signaling promoted by isotretinoin in the human may mimic the augmentation of this pathway resulting from the elevation in RARα seen by Chen et al in the PVN of depressed patients.138 This provides a new mechanism by which isotretinoin may promote depression.

3.3.3 Metabolic effects of isotretinoin and depression

Isotretinoin administration has also been shown to affect metabolic pathways, alterations of which have been linked to depression; two examples are given below involving biotin and homocysteine. Biotin, a member of the B vitamin family (vitamin B-7) is a required nutrient that is involved in the biosynthesis of fatty acids, gluconeogenesis, and metabolism of amino acids. Side effects of biotin deficiency include hair loss, conjunctivitis, neuromuscular dysfunction, skin changes, neurological dysfunction, and of note for this review, depression.139-143 For instance, Baugh described a dietary induced case of biotin deficiency resulting in anorexia, nausea, vomiting, glossitis, skin changes and depression,144 while Levenson139 described a biotin deficiency case which was associated with depression and thoughts of suicide. These symptoms went away after biotin supplementation. One mechanism by which biotin is recycled in the body, maintaining its availability, is supported by the enzyme biotinidase.145 Mutations in this enzyme result in biotin deficiency.140, 145-151 Isotretinoin administration to human subjects is associated with a decrease of biotinidase,152 and the presumed decrease in biotin that would result from this may contribute to depression.

Homocysteine is a sulphur containing amino acid that is involved in carbon transfer reactions.153 Homocysteine can receive a methyl group from 5′-methyltetrahydrofolate and become re-methylated to methionine, the immediate precursor of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM), a donor of methylation reactions involved in the synthesis of DNA, proteins, phospholipids, neurotransmitters and polyamines. SAM is involved in the synthesis in the brain of dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin, neurotransmitters that have been linked to depression,154, 155 and many studies have found a relationship between elevated homocysteine levels, lower folate concentrations, and depression.153, 156-164 Increased concentrations of homocysteine have also been associated with attacks of violent anger.165 Isotretinoin administration to human subjects was shown to be associated with increased concentrations of homocysteine,166 as well as decreases in 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate,167 providing a potential metabolic mechanism by which isotretinoin may promote depression.

3.3.4 Evidence of effects of isotretinoin on human brain function

The fact that isotretinoin is associated with neurological side effects demonstrates that it has an effect on brain function. Adverse reactions are common with isotretinoin, with at least 90% of patients treated reporting at least one side effect.168 Bigby and Stern62 reviewed adverse reactions to isotretinoin reported to the Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting System between 1982 and 1985. They reported 104 side effects which included (in decreasing frequency): skin reactions (dryness), central nervous system complaints, musculoskeletal system and pregnancy difficulties, and eye, hematopoietic, gastrointestinal, cardiorespiratory, and genitourinary disorders. Other less common side effects in this study were liver and bone abnormalities. The most common neurological adverse reaction was headache in 11 patients. In four of the subjects this was associated with pseudotumor cerebri, an idiopathic increase in intracranial pressure with papilledema and headache, and normal CT/MRI and CSF fluid; a swelling of the brain that can be fatal. Headache was the most common side effect of isotretinoin after dry skin62 while a number of other reports have associated isotretinoin with pseudotumor cerebri.54, 169-171 The occurrence of headache with isotretinoin usage has been linked to depression172 suggesting that patients who show a CNS side effect such as headache may also be more susceptible to isotretinoin-induced depression. Certainly, these neurological side effects are further evidence that 13-cis RA can influence the brain.

There is evidence that some of the neurological side effects are not immediately reversible. Neurological events reported to the Norwegian Medicines Agency were assessed in patients treated with isotretinoin. There were 91 total adverse events reported from 1985-2005. Thirty nine included long lasting neurological or muscular symptoms. Long lasting neurological symptoms including memory loss, dizziness, headache, loss of concentration and ataxia were present in 17 cases. Symptoms persisted 2-18 months after stopping treatment.173

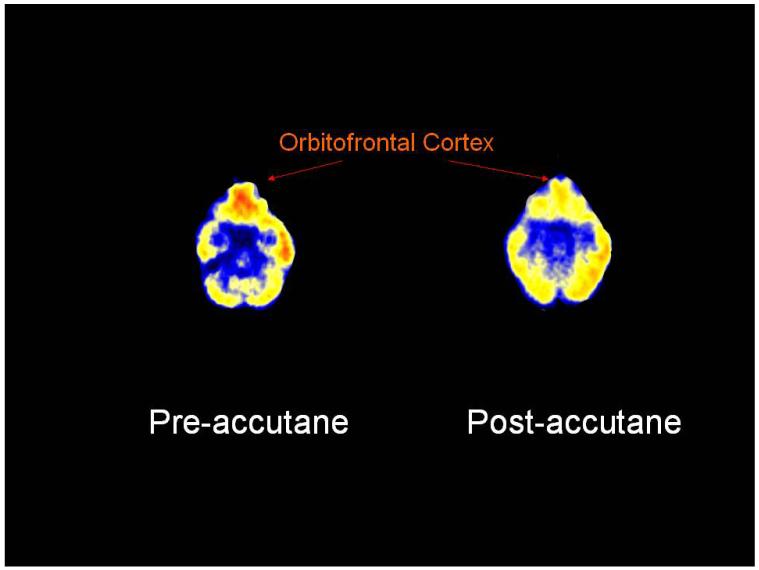

The influence of isotretinoin on brain metabolism has been directly investigated using PET FDG, a technique that maps regional differences in glucose uptake in the brain. Twenty-eight subjects with acne were imaged before and after four months treatment with 13-cis RA or antibiotics (13 with 13-cis RA, 15 with antibiotics). Patients were also assessed for depression using the Hamilton Depression Scale (Ham-D). This study revealed that four months of 13-cis RA treatment led a to significant reduction in brain metabolism in the orbitofrontal cortex (Fig. 3),174 a region that has been associated with depression.

Fig. 3.

The influence of 13-cis RA on brain glucose metabolism measured by PET FDG. Four months 13-cis RA treatment results in a clear decrease in orbitofrontal cortical function in this representative subject. The same subject had symptoms of headache and slight behavioral change, although not clinical depression.

In the case of patients reported to the Norwegian Medicines Agency, single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) of the brain was performed in 15 cases who reported lasting neurological symptoms. Altered brain function was seen in all cases involving altered or reduced frontal lobe blood flow.173 Ten of these patients were evaluated to have organic brain damage.

4. Discussion

This paper has outlined the evidence for a relationship between isotretinoin and depression, which includes evidence from case reports in the literature, temporal association, challenge-rechallenge studies, dose response, biological plausibility and class effect. According to Strom,175 the existence of challenge-rechallenge cases alone are adequate to establish a causal link between a side effect and a drug. However, as reviewed in this paper, there are a number of lines of evidence showing that isotretinoin can cause depression and suicide in some susceptible individuals.

Drug regulatory agencies world-wide are now warning patients about the risk of depression and suicide with isotretinoin, which has had an impact on prescribing behavior. Additionally, there is a growing consensus in the medical and mental health community that this is a real problem that can affect a minority of treated individuals, and that patients treated with isotretinoin need to be monitored closely for psychiatric side effects, and that patients and families should be fully informed of the risks and benefits of this medication.19, 176-179 Nonetheless the dermatology community continues to incorrectly state that acne causes depression and that treating acne with isotretinoin is a treatment for depression, rather than a cause of depression in some individuals. However the evidence for an association is comparable to other drugs, such as steroids, which are accepted as being associated with psychiatric side effects.

An interesting finding from the brain imaging studies in isotretinoin treated subjects was that the patients with headache were more likely to have decreased orbitofrontal function with isotretinoin. This finding parallels the findings of Wysowski and Swartz172 that headache is associated with depression in isotretinoin-treated patients. It raises the possibility that subjects who are sensitive to isotretinoin induced effects on the CNS, such as headache, may also be susceptible to other neural side-effects of this drug such as depression.

Studies that make use of double blind placebo controlled randomizations to assess the effects of isotretinoin on symptoms of depression and mood lability will be useful in the identification of factors that put individual patients at risk. The FDA recommended such studies after a 2 day meeting on the topic in 2000, however in 2002 the FDA then advised against such a study as it would be too difficult to adequately blind, because of the dry skin side effects of isotretinoin. However, topical retinol can be given as a control treatment, which dries the skin, and results in minimal absorption into the bloodstream. Based on the literature to date, clinicians should carefully consider whether or not to rechallenge patients who have previously experienced depression while on isotretinoin. Similarly, the treatment of patients with a psychiatric disorder, especially bipolar disorder, appears to pose a high risk for exacerbation of symptoms.

Studies performed to date have had limitations, including the use of retrospective databases with insufficient information, the lack of sufficient sample size to determine whether an effect on depression exists, lack of placebo controls and randomization, the lack of specific standardized assessments of depression and other behaviors. Large placebo controlled trials assessing the effects of isotretinoin on depression would be a scientific advance, however the ethics of conducting such a trial when there is adequate aggregate information supporting a causal role of isotretinoin in the development of depression in some individuals, given the risks of the drug, is questionable.

Acknowledgements

PM and KS gratefully acknowledge the Wellcome Trust for their financial support of this research and Ms Lynn Doucette for her work on Figure 1. JDB received support from NIH research grants R01 HL088726, K24 MH076955, T32 MH067547-01, and R01 MH56120. JDB has worked as an expert witness for plaintiffs in legal cases involving isotretinoin (not in past 12 months).

PM received funding from the Wellcome Trust. JDB received support from NIH research grants R01 HL088726, K24 MH076955, T32 MH067547-01, and R01 MH56120. JDB has worked as an expert witness for plaintiffs in legal cases involving isotretinoin (not in past 12 months).

References

- 1.Maden M. The role of retinoic acid in embryonic and post-embryonic development. Proceedings of the Nutritional Society. 2000;59:65–73. doi: 10.1017/s0029665100000082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sporn MB, Roberts AB, Goodman DS. The Retinoids: Biology, Chemistry, and Medicine. Raven Press; New York: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lammer EJ, Armstrong DL. In: Malformations of hindbrain structures among humans exposed to isotretinoin (13-cis-retinoic acid) during early embryogenesis. Morris-Kay GM, editor. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCaffery PJ, Adams J, Maden M, Rosa-Molinar E. Too much of a good thing: retinoic acid as an endogenous regulator of neural differentiation and exogenous teratogen. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18:457–472. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coberly S, Lammer E, Alashari M. Retinoic acid embryopathy: case report and review of literature. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med. 1996;16:823–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orfanos CE, Zouboulis CC, Almond-Roesler B, Geilen CC. Current use and future potential role of retinoids in dermatology. Drugs. 1997;53:358–384. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199753030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunliff WJ, van der Kerkhof PCM, Caputo R, Caicchini S, Cooper A, Fyrand OL, Gollnick H, Layton AM, Leyden JJ, Mascaro J-M, Ortonne J-P, Shalita A. Roaccutane treatment guidelines: Results of an international survey. Pharm Treatment. 1997;194:351–357. doi: 10.1159/000246134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goulden V, Layton AM, Cunliffe WJ. Current indications for isotretinoin as a treatment for acne vulgaris. Pharm Treatment. 1995;190:284–287. doi: 10.1159/000246717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eckhoff C, Nau H. Identification and quantitation of all-trans- and 13-cis-retinoic acid and 13-cis-4-oxoretinoic acid in human plasma. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:1445–1454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsukada M, Schroder M, Roos TC, Chandraratna RA, Reichert U, Merk HF, Orfanos CE, Zouboulis CC. 13-cis retinoic acid exerts its specific activity on human sebocytes through selective intracellular isomerization to all-trans retinoic acid and binding to retinoid acid receptors. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:321–327. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shih TW, Shealy YF, Strother DL, Hill DL. Nonenzymatic isomerization of all-trans- and 13-cis-retinoids catalyzed by sulfhydryl groups. Drug Metabol Dispos. 1986;14:698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weigan U-W, Chou RC. Pharmacokinetics of oral isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:S8–12. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70438-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hull PR, D’Arcy C. Acne, depression, and suicide. Dermatol Clin. 2005;23:665–674. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hull PR, D’Arcy C. Isotretinoin use and subsequent depression and suicide: Presenting the evidence. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:493–505. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200304070-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jick SS, Kremers HM, Vasilakis-Scaramozza C. Isotretinoin use and risk of depression: Psychotic symptoms, suicide, and attempted suicide. Arch Dermatol. 2000;136:1231–1236. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.10.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wysowski DK, Pitts M, Beitz J. An analysis of reports of depression and suicide in patients treated with isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:515–519. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.117730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Byrne A, Costello M, Greene E, Zibin T. Isotretinoin therapy and depression-evidence for an association. Irish J Psychosom Med. 1998;15:58–60. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bremner JD. Does isotretinoin cause depression and suicide? Psychopharmacol Bull. 2003;37:5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ng CH, Schweitzer I. The association between depression and isotretinoin use in acne. Aust N Z J Psych. 2003;37:78–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacobs DG, Deutsch N, Brewer M. Suicide, depression, and isotretinoin: Is there a causal link? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:S168. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.118233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Donnell J. Overview of existing research and information linking isotretinoin (Accutane), depression, psychosis and suicide. Am J Ther. 2003;10:148–159. doi: 10.1097/00045391-200303000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marqueling AL, Zane LT. Depression and suicidal behavior in acne patients treated with isotretinoin: A systematic review. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2005;24:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.sder.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strahan JE, Raimer S. Isotretinoin and the controversy of psychiatric adverse effects. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:789–799. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bremner JD. Isotretinoin and depression: Is there a causal link? Practical Dermatology. 2005;2:30–33. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kontaxakis VP, Skourides D, Ferentinos P, Havaki-Kontaxaki BJ, Papadimitriou GN. Isotretinoin and psychopathology: A review. Annals of General Psychiatry. 2009;8:2–8. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Enders SJ, Enders JM. Isotretinoin and psychiatric illness in adolescents and young adults. Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2003;37:1124–1127. doi: 10.1345/aph.1C415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bremner JD, McCaffery P. The neurobiology of retinoic acid in affective disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:315–331. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Silverman AK, Ellis CN, Voorhees JJ. Hypervitaminosis A syndrome: A paradigm of retinoid side effects. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:1027–1039. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70133-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henderson CA, Highet AS. Depression induced by etrinate [letter] Brit Med J. 1989;298:96. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6678.964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arican O, Sasmaz S, Ozbulut O. Increased suicidal tendency in a case of psoriasis vulgaris under acitretin treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:464. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01447.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frame B, Jackson CE, Reynolds WA, Umphrey JE. Hypercalcemia and skeletal effects in chronic hypervitaminosis A. Ann Intern Med. 1974;80:44–48. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-80-1-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw EW, Niccoli JZ. Hypervitaminosis A: Report of a case in an adult male. Ann Intern Med. 1953;39:131–134. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-39-1-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gerber A, Raab AP, Sobel AE. Vitamin A poisoning in adults: With description of a case. Am J Med. 1954;16:729–745. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(54)90281-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muenter MD, Perry HO, Ludwig J. Chronic vitamin A intoxication in adults. Hepatic, neurologic and dermatologic complications. Am J Med. 1971;50:129–136. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(71)90212-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elliott RA, Dryer RL, Hypervitaminosis A. Report of a case in an adult. JAMA. 1956;161:1157–1159. doi: 10.1001/jama.1956.62970120005010a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soler-Bechara J, Soscia JL. Chronic hypervitaminosis A. Report of a case in an adult. Arch Intern Med. 1963;112:462–466. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1963.03860040058003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morrice G, Havener WH, Kapetansky F. Vitamin A intoxication as a cause of pseudotumor cerebri. JAMA. 1960;173:100–103. doi: 10.1001/jama.1960.03020340020005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Persson B, Tunnell R, Ekengren K. Chronic vitamin A intoxication during the first half year of life: description of five cases. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1965;54:49–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1965.tb06345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliver TK, Havener WH. Eye manifestions of chronic vitamin A intoxication. Archives of Opthalmology. 1958;60:19–22. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1958.00940080033004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Restak RM. Pseudotumor cerebri, psychosis, and hypervitaminosis A. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1972;155:155–172. doi: 10.1097/00005053-197207000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bifulco E. Vitamin A intoxication: report of a case in an adult. N Engl J Med. 1953;248:690–692. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195304162481606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shaywitz BA, Siegal NJ, Pearson HA. Megavitamins for minimal brain dysfunction. A potentially dangerous therapy. JAMA. 1977;238:1749–1750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCance-Katz EF, Price LH. Depression associated with Vitamin A intoxication. Psychosomatics. 1992;33:117. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3182(92)72033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fishbane S, Frei GL, Finger M, Dressler R, Silbiger S. Hypervitaminosis A in two hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25L:346–349. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haupt R. Akute symptomatische psychose bei Vitamin A-Intoxikation. Der Nervaenarzt. 1977;48:91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Landy D. Pibloktoq (hysteria) and Inuit nutrition: Possible implication of hypervitaminosis A. Soc Sci Med. 1985;21:173–185. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(85)90087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Marie J, See G. Acute hypervitaminosis A of the infant. Its clinical manifestation with benign acute hydrocephaly and pronounced bulge of the fontanel. A clinical and biologic study. Am J Dis Child. 1954;73:731–736. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1954.02050090719008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lombaert A, Carton H. Benign intracranial hypertension due to A-hypervitaminosis in adults and adolescents. European Neurology. 1976;14:340–350. doi: 10.1159/000114758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oliver TK, Havener WH. Eye manifestations of chronic Vitamin A intoxication. AMA Arch Opthalmol. 1958;60:19–22. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1958.00940080033004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Selhorst JB, Waybright EA, Jennings S, Corbett JJ. Liver lover’s headache: Pseudotumor cerebri and vitamin A intoxication. JAMA. 1984;252:3365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alemayehu W. Pseudotumor cerebri (Toxic effect of the “magic bullet”) Ethiop Med J. 1995;33:265–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Seigel NJ, Spackman TJ. Chronic hypervitaminosis A with intracranial hypertension and low cerebrospinal fluid concentration of protein. Clin Pediatr. 1972;11:580–584. doi: 10.1177/000992287201101011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gomber S, Chellani H. Acute toxicity of vitamin A administered with measles vaccine. Indian Pediatr. 1996;33:1053–1055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spector RH, Carlisle J. Pseudotumor cerebri caused by a synthetic vitamin A preparation. Neurology. 1984;34:1509–1511. doi: 10.1212/wnl.34.11.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Byrne A, Hnatko G. Depression associated with isotretinoin therapy [letter] Can J Psychiat. 1995;40:567. doi: 10.1177/070674379504000915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bravard P, Krug M, Rzeznick JC. Isotretinoine et depression: soyons vigilants. Nouvelle Dermatology. 1993;12:215. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duke EE, Guenther L. Psychiatric reactions to the retinoids. Can J Dermatol. 1993;5:467. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bruno NP, Beacham BE, Burnett JW. Adverse effects of isotretinoin therapy. Cutis. 1984;33:484–489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hazen PG, Carney JF, Walker AE, Stewart JJ. Depression-a side effect of 13-cis-retinoic acid therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;9:278–279. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(83)80154-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lindemayr H. Isotretinoin intoxication in attempted suicide. Acta Dermato-Venereologica. 1986;66:452–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Burket JM, Storrs FJ. Nodulocystic infantile infantile acne occurring in a kindred of steatocystoma. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:432–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bigby M, Stern RS. Adverse reactions to isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:543–552. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(88)70078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Scheinman PL, Peck GL, Rubinow DR, DiGiovanna JJ, Abangan DL, Ravin PD. Acute depression from isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1112–1114. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)81018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hepburn NC. Deliberate self-poisoning with isotretinoin. Brit J Dermatol. 1990;122:840–841. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb06279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gatti S, Serri F. Acute depression from isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:132. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(08)80509-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aubin S, Lorette G, Muller CR, Vaillant L. Massive isotretinoin intoxication. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1995;20:348–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1995.tb01341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cotterill JA, Cunliff WJ. Suicide in dermatological patients. Brit J Dermatol. 1997;137:246–250. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.18131897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cott AD, Wisner KL. Isotretinoin treatment of a woman with bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:407–408. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v60n0611a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Middelkoop T. Roaccutane (Isotretinoin) and the risk of suicide: Case report and a review of the literature and pharmacovigilance reports. J Pharm Practice. 1999;12:374–378. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hull PR, Demkiw-Bartel C. Isotretinoin use in acne: prospective evaluation of adverse events. J Cut Med Surg. 2000;4:66–70. doi: 10.1177/120347540000400205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pitts M. FDA Hearings on Isotretinoin and Suicide and Depression. FDA; Washington, DC: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ng CH, Tam MM, Hook SJ. Acne, isotretinoin treatment and acute depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2001;2:159–161. doi: 10.3109/15622970109026803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wysowski DK, Pitts M, Beitz J. Depression and suicide in patients treated with isotretinoin. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:460. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ng CH, Tam MM, Celi E, Tate B, Schweitzer I. Prospective study of depressive symptoms and quality of life in acne vulgaris patients treated with isotretinoin compared to antibiotic and topical therapy. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;45:262–268. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-0960.2002.00612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Robusto O. Depressao por antiacneico. Acta Med Port. 2002;15:325–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.van Broekhoven F, Verkes RJ, Janzing JG. Psychiatric symptoms during isotretinoin therapy. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2003;147:2341–2343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.La Placa M. Acute depression from isotretinoin. Another case. Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:380–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2004.01120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Barak Y, Wohl Y, Greenberg Y, Bar Dayan Y, Friedman T, Shoval G, Knobler HY. Affective psychosis following Accutane (isotretinoin) treatment. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20:39–41. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bachmann C, Grabarkiewicz J, Theisen FM, Remschmidt H. Isotretinoin, depression and suicide ideation in a adolescent boy. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2007;40:128–131. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-972575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cohen J, Adams S, Patten S. No association found between patients receiving isotretinoin for acne and the development of depression in a Canadian prospective cohort. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;14:e227–e233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Schaffer LC, Schaffer CB, Hunter S, Miller A. Psychiatric reactions to isotretinoin in patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2010;122:306–308. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Villalobos D, Ellis M, Snodgrass WR. Isotretinoin (Accutane)-associated psychosis. Vet Human Toxicol. 1989;31:362. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Friedman T, Wohl Y, Knobler HY, Lubin G, Brenner S, Levi Y, Barak Y. Increased mental health services related to isotretinoin treatment: A 5-year analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharm. 2006;16:413–416. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chia CY, Lane W, Chibnall J, Allen A, Siegfried E. Isotretinoin therapy and mood changes in adolescents with moderate to severe acne. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:557–560. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.5.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]