Abstract

Metallointercalating photooxidants interact intimately with the base stack of double-stranded DNA and exhibit rich photophysical and electrochemical properties, making them ideal probes for the study of DNA-mediated charge transport (CT). The complexes [Rh(phi)2(bpy′)]3+ (phi = 9,10-phenanthrenequinone diimine; bpy′ = 4-methyl-4′-(butyric acid)-2,2′-bipyridine), [Ir(ppy)2(dppz′)]+ (ppy = 2-phenylpyridine; dppz′ = 6-(dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazin-11-yl)hex-5-ynoic acid), and [Re(CO)3(dppz)(py′)]+ (dppz = dipyrido[2,3-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine; py′ = 3-(pyridin-4-yl)-propanoic acid) were each covalently tethered to DNA in order to compare their photooxidation efficiencies. Biochemical studies show that upon irradiation, the three complexes oxidize guanine by long-range DNA-mediated CT with the efficiency: Rh > Re > Ir. Comparison of spectra obtained by spectroelectrochemistry after bulk reduction of the free metal complexes with those obtained by transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy of the conjugates suggests that the reduced metal states form following excitation of the conjugates at 355 nm. Electrochemical experiments and kinetic analysis of the TA decays indicate that the thermodynamic driving force for CT, variations in the efficiency of back electron transfer, and coupling to DNA are the primary factors responsible for the trend observed in the guanine oxidation yield of the three complexes.

INTRODUCTION

Cellular DNA is continually under the threat of oxidation from a host of sources.1–4 Left unrepaired, oxidative damage to DNA leads to health problems, including cancer.5–7 In order to improve our understanding of the chemical mechanisms underlying oxidative damage, as well as the biological factors affecting the prevalence, detection, and repair of such damage, it is necessary to utilize a wide variety of chemical and biological tools and techniques.

One especially useful tool for the study of oxidative damage in DNA is DNA-mediated charge transport (CT). Due to orbital overlap between the π systems of neighboring nucleobases, DNA can serve as a bridge in long-range electron transfer (ET) reactions. Unlike photocleavage mechanisms, many of which result in the formation of nonspecific damage by reactive oxygen species,8–10 or photoligation mechanisms, which lead to the formation of unnatural adducts between metal complexes and DNA,11 DNA-mediated CT results in preferential damage at sites of low oxidation potential. Oxidative events at low potential guanine sites (E°[G•+/G] = 1.29 V vs. NHE)12 can be initiated by many different DNA-bound oxidants, including organic molecules, transition metal complexes, and DNA base analogues,13–18 allowing for the study of DNA oxidation in a wide variety of environments and sequence contexts. Additionally, oxidative probes are capable of inducing damage in regions far from the site of charge injection. In solution studies, damage at guanine sites was observed almost 200 Å away from a DNA-bound oxidant.19 Recently, our laboratory observed the propagation of robust redox signals over a distance of 100 base pairs, or 340 Å, in DNA monolayers on gold electrodes.20 DNA CT may fulfill biological roles as well. The observed funneling of oxidative damage to regions of mitochondrial DNA that contain genes necessary for replication may serve as a check against the propagation of damaged genetic material in situations of high oxidative stress.21 DNA CT also may be involved in other capacities within the cell,22 for example, to activate transcription23,24 and to perform long-range signaling.25

In order to study such reactions in the laboratory, it is necessary to have a convenient method for initiating DNA CT reactions.26 Transition metal complexes have proven especially amenable for use as oxidants in the study of DNA damage due to their synthetic versatility and the ability to tune their redox properties. In addition, an appropriate ligand set enables metal complexes to interact strongly with DNA through intercalative binding, allowing for the initiation of long-range DNA-mediated oxidation by optical excitation of the bound complex. Complexes of the type [Rh(phi)2(L)]3+ (phi = 9,10-phenanthrenequinone diimine), where L = bpy (2,2′-bipyridine) or phen (phenanthroline), are especially strong photooxidants. These complexes, which bind DNA through intercalation of the phi ligand, were used to establish the ability of DNA to propagate charge.27 Photoexcitation of DNA-bound [Rh(phi)2(L)]3+ at 365 nm leads to injection of a positive charge into the DNA base stack, which then equilibrates at sites of low redox potential (guanine and guanine repeats).19,28 Iridium complexes have also been used to initiate DNA-mediated CT processes. The complex [Ir(ppy)2(dppz)]+ (ppy = 2-phenylpyridine; dppz = dipyrido[2,3-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine) intercalates into DNA via the dppz ligand. Interestingly, from the excited state, the complex is a strong enough reductant and oxidant to promote both the reduction and the oxidation of DNA.29 This remarkable ability has enabled characterization of DNA-mediated electron transfer and DNA-mediated hole transfer in identical sequence contexts, showing that both have a shallow distance dependence.30,31 Tricarbonyl rhenium complexes are of interest due to the strong infrared absorption of the carbonyl ligands. Excitation and reduction of such complexes can be followed temporally by observing dynamic changes in the stretching frequencies of the carbonyl ligands.32–34 In addition, complexes such as [Re(CO)3(dppz)(L)]n+ act as “light switches,”35 luminescing only when bound to DNA.36–39 Such interesting photophysical properties provide additional means of monitoring DNA CT events.

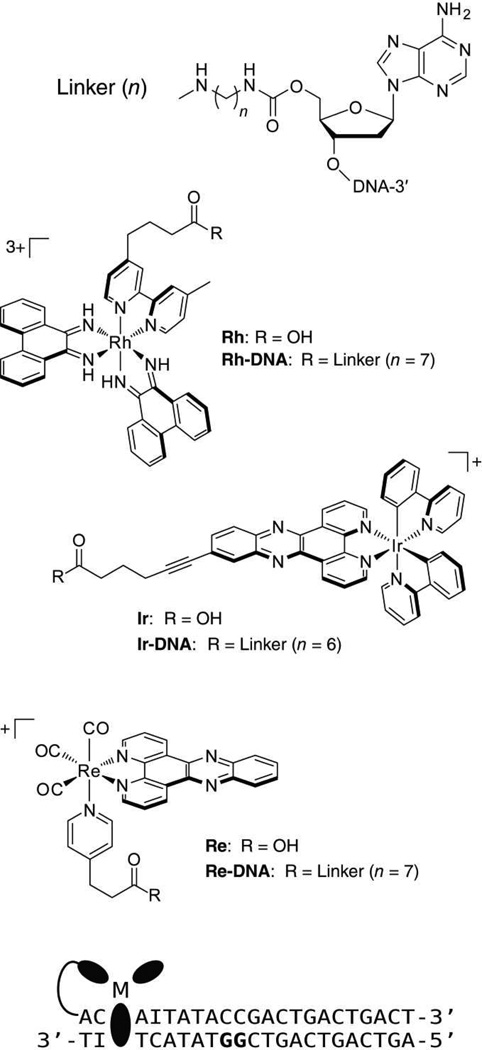

Due to the large number of factors that affect the relative efficiency of DNA CT, such as DNA binding strengths, redox properties, and photophysical behavior of various metal complexes, it is necessary to compare DNA oxidants in identical environments. In the present study, we have examined the ability of three metal complexes to report on DNA-mediated oxidation events through the appearance of their reduced states. We have focused on investigation of the reduced states of [Rh(phi)2(bpy′)]3+, [Ir(ppy)2(dppz′)]+, and [Re(CO)3(dppz)(py′)]+ [Rh, Ir, and Re, respectively; bpy′ = 4-methyl-4′-(butyric acid)-2,2′-bipyridine; dppz′ = 6-(dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazin-11-yl)hex-5-ynoic acid; py′ = 3-(pyridin-4-yl)-propanoic acid] and their DNA-conjugates (Rh-DNA, Ir-DNA, and Re-DNA) in aqueous and organic solutions, as well as their efficiencies of DNA photooxidation. The structures of the complexes and conjugates are shown in Figure 1. We have used steady-state spectroelectrochemistry and nanosecond transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy to record the electronic spectra of the reduced states of the metal complexes and the charge transfer products of the metal-DNA conjugates, respectively. In addition, we have compared these spectral profiles with the redox properties and efficiency of DNA photooxidation of the three complexes.

Figure 1.

Structures of complexes and DNA sequences used in biochemical and spectroscopic experiments. The complexes were used free in solution or were covalently attached to the DNA sequence shown via an alkyl linker (n = 6 or 7). The 5′-GG-3′ site is shown in bold. Physical models suggest that the tethered complexes intercalate 1–3 bases from the end of the duplex.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Materials

Unless indicated otherwise, all reagents and solvents were of reagent grade or better and were used as received without further purification. All reagents for DNA synthesis were purchased from Glen Research (Sterling, VA). The complexes Ir and Rh were laboratory stocks and had been prepared from published protocols.29,40

Synthesis of Metal Complexes

The synthesis of [fac-Re(CO)3(dppz)(py′)][Cl] closely followed the procedure of Stoeffler, et al.37 A mixture of 253 mg (0.7 mmol) Re(CO)5Cl and 147 mg (0.7 mmol) 1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione in 7 mL toluene was refluxed (110 °C) for 4.5 h. The crude solid product was collected by suction filtration, purified by silica gel using THF as an eluent, and dried under vacuum to yield Re(CO)3Cl(1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione) as an orange microcrystalline solid. Re(CO)3Cl(dppz) was formed by heating 160 mg (0.31 mmol) Re(CO)3Cl(1,10-phenanthroline-5,6-dione) in 15 mL EtOH to reflux (85 °C), adding 55 mg (0.6 mmol) o-phenylenediamine, and refluxing the mixture for 1 h. The yellow-ochre solid product was collected by suction filtration. 1H NMR (300 MHz) in DMSO indicated the presence of the dppz ligand: δ 8.22 (q, 2H), 8.31 (m, 2H), 8.55 (q, 2H), 9.58 (d, 2H), 9.88 (d, 2H). The desired product was obtained following substitution for the Cl ligand. A suspension of 160 mg (0.27 mmol) Re(CO)3Cl(dppz) was heated under Ar to 50 °C in 25 mL dry DMF. After addition of 280 mg (1.1 mmol) AgPF6, the reaction mixture was heated at 50 °C for 5 min., then 250 mg (1.7 mmol) py′ was added and the mixture was refluxed at 70 °C under Ar for 6 h. The reaction was cooled, and the AgCl precipitate was removed by gravity filtration, yielding an orange-yellow solution. The crude product was purified by silica gel using 5% methanol in chloroform as the eluent, and then dried under vacuum to yield [Re(CO)3(dppz)(py′)](PF6). The PF6 counter ion was exchanged for chloride using Sephadex QAE A-25 anion exchange resin, and the resulting solution was concentrated using a C18 Sep-Pak to yield fac-[Re(CO)3(dppz)(py′)]Cl as a bright yellow solid. 1H NMR (PF6 salt, 300 MHz, CD3CN): δ 9.79 (dd, 2H), 9.65 (dd, 2H), 8.37 (dd, 2H), 8.23 (m, 4H), 8.09 (dd, 2H), 7.13 (d, 2H), 2.73 (t, 2H), 2.44 (t, 2H). 13C NMR (PF6 salt, 300 MHz, CD3CN): δ 155.3, 155.0, 151.3, 149.0, 142.4, 136.5, 132.4, 129.3, 128.2, 126.3, 32.3, 28.9. ESI: calcd 703.7 for C29H19N5O5Re (M+), found 703.9.

The related ethyl ester was prepared in the same way following the Fischer esterification of py′. 1H NMR (PF6 salt, 300 MHz, CD3CN): δ 9.90 (dd, 2H), 9.65 (dd, 2H), 8.45 (dd, 2H), 8.26 (dd, 2H), 8.20 (dd, 2H), 8.13 (dd, 2H), 7.09 (d, 2H), 3.88 (q, 2H), 2.72 (t, 2H), 2.41 (t, 2H), 0.99 (t, 3H). ESI: calcd 731.8 for C31H23N5O5Re (M+), found 732.0.

DNA Synthesis and Modification

Oligonucleotides were prepared using standard solid-phase phosphoramidite chemistry on an Applied Biosystems 3400 DNA synthesizer. Covalent tethers were appended to the 5′-ends of resin-bound oligonucleotides in two ways. For the Ir-DNA conjugate, an amino-terminated C6-alkyl phosphoramidite was added in the last step of the automated synthesis; for the Rh- and Re-DNA conjugates, a diaminononane linker was added as previously described.41 Agitation of the amine modified strands in the presence of metal complex, O-(benzotriazol-1-yl)-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate (HBTU), 1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate (HOBT), and diisopropylethylamine (DIEA) in anhydrous DMF resulted in covalent attachment of the metal complexes to the DNA. Cleavage from the resin was effected by incubation in NH4OH at 60 °C for 6 h. Strands were purified by reversed-phase HPLC (50 mM aqueous ammonium acetate/acetonitrile gradient) using a Clarity 5μ Oligo-RP column (Phenomenex). Oligonucleotides were characterized by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and quantitated by UV/visible spectroscopy. Annealing was accomplished by incubating solutions containing equimolar amounts of complementary strands in buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl buffer; pH 7.5) at 90 °C for 5 min. followed by slow cooling over 90 min. to ambient temperature. The melting temperature (Tm) of each duplex was determined by monitoring the 260 nm absorbance of a dilute sample while heating slowly (1 °C min−1) from ambient temperature to 100 °C; the Tm is taken as the inflection point of the melting curve.

Electrochemistry

Electrochemical measurements were carried out using an electrochemical workstation (CH Instruments 650A). Cyclic voltammetry (CV) was performed at ambient temperature using a standard three electrode apparatus with a glassy carbon working electrode, a Pt auxiliary electrode, and a Ag/AgCl reference electrode. The use of an internal ferrocene/ferrocenium standard for CV measurements facilitated conversion of the potentials referenced vs. Ag/AgCl to NHE. Immediately prior to measurement, samples were degassed rigorously with N2. All samples were measured in the presence of 0.1 M tetra-n-butylammonium hexafluorophosphate electrolyte. All redox potentials are reported herein vs. NHE.

Gel Electrophoresis

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) experiments were performed based on published procedures.42 Briefly, DNA strands were radioactively labeled on the 5′-end with [γ-32P]-ATP (MP Biomedicals), treated with 10% piperidine for 25 min at 90 °C, and purified by 20% PAGE. Duplexes were formed by heating a mixture of the purified, labeled strands (8 pmol), unlabeled strands of the same sequence (192 pmol), and complement strands bearing tethered metal complexes (200 pmol) at 90 °C for 5 min followed by slow cooling over 90 min to ambient temperature. Irradiation of 2 µM (duplex) samples for various times was carried out using an Oriel Instruments solar simulator (300–440 nm) equipped with a 355 nm long-pass filter. Samples were treated with 0.2 units calf thymus DNA to improve sample recovery and 10% piperidine (v/v) to induce strand cleavage at damaged sites, heated for 30 min at 90 °C, and dried in vacuo. Following separation by 20% PAGE, gels were developed using a Molecular Dynamics Storm 820 phosphorimager and Molecular Dynamics phosphorimaging screens. Gels were visualized and quantified using ImageQuant software (Molecular Dynamics). Damage at specific sites is determined as percent counts relative to the total counts per lane.

Spectroelectrochemistry

UV-visible spectroelectrochemistry was carried out using a custom-built, optically transparent, thin-layer electrode (OTTLE) cell (path length = 0.1 mm) consisting of vapor-deposited platinum working and pseudoreference electrodes and a Pt-wire auxiliary electrode.43 The potential of the cell was controlled by an electrochemical workstation (CH Instruments 650A). Samples consisted of saturated solutions of metal complexes in dry organic solvents that were degassed under N2 and introduced into the optical cell using a gastight syringe. The cell was held at a reducing potential, and spectra were acquired every 4 s until the sample was fully reduced using a spectrophotometer (Hewlett Packard 8452A).

Time-Resolved Spectroscopy

Steady-state emission spectra were recorded on a Fluorolog-3 spectrofluorometer (Jobin Yvon) using 2 mm slits. Scattered light was rejected from the detector by appropriate filters.

Time-resolved spectroscopic measurements were carried out at the Beckman Institute Laser Resource Center. Time-resolved emission and TA measurements were conducted using instrumentation that has been described.44 Briefly, the third harmonic (355 nm) of a 10 Hz, Q-switched Nd:YAG laser (Spectra-Physics Quanta-Ray PRO-Series) was used as an excitation source (pump pulse duration ≈ 8 ns). For the measurement of transient absorbance spectra, a white light flashlamp of ~15 ns duration was employed as the probe lamp, and two photodiode arrays (Ocean Optics S1024DW Deep Well Spectrometer) detected the measurement and reference beams. For the measurement of transient kinetics, the probe light was provided by a pulsed 75 W arc lamp (PTI model A 1010) and detected with a photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu R928) following wavelength selection by a double monochromator (Instruments SA DH-10). For both spectral and kinetic measurements, the pump and probe beams were collinear, and scattered laser light was rejected from the detectors using suitable filters. The samples were held in 1 cm path length quartz cuvettes (Starna) equipped with stir bars and irradiated at 355 nm with 500–1000 laser pulses at 5 mJ/pulse. Samples were monitored for degradation by UV/visible absorbance and exchanged for fresh sample when necessary. Samples were prepared with a maximum absorbance of 0.7 in order to achieve high signal-to-noise ratios in TA experiments. TA measurements were made with and without excitation, and were corrected for background light, scattering, and fluorescence. Transient spectra were smoothed using a boxcar algorithm to reduce the effect of instrumental noise.

Kinetic traces were fit to exponential equations of the form I(t) = a0 + Σan exp(−t/τn), where I(t) is the signal intensity as a function of time, a0 is the intensity at long time, an is a pre-exponential factor that represents the relative contribution from the nth component to the trace, and τn is the lifetime of the nth component. Up to two exponential terms were used in the model function to obtain acceptable fits. Kinetic traces were smoothed logarithmically prior to fitting in order to decrease the weight of long time data on the fit.

RESULTS

Metal Complex Synthesis and Characterization

The Rh and Ir metal complexes each contain one intercalating ligand (phi in Rh and dppz in Ir) and two ancillary ligands, resulting in the formation of Δ and Λ stereoisomers. The efficiency of DNA CT depends strongly on the extent of coupling between the DNA base stack and the bound metal complex, so the stronger binding Δ-isomer is preferred for CT experiments.41 While the diastereomers of Rh-DNA conjugates are easily resolved by reversed-phase HPLC, those of Ir-DNA conjugates are not. For this reason, only the Δ-isomer of Rh-DNA was used in experiments involving metal complex-DNA conjugates, while Ir-DNA was used as an isomeric mixture. For experiments involving free metal complexes, isomeric mixtures were used. The Re complex was synthesized using the published protocol for the analogous complex, fac-[Re(CO)3(dppz)(4-methylpyridine)]+.37 Only the facial stereoisomer is expected to form during synthesis, so enantiomeric separation was not a consideration during purification.

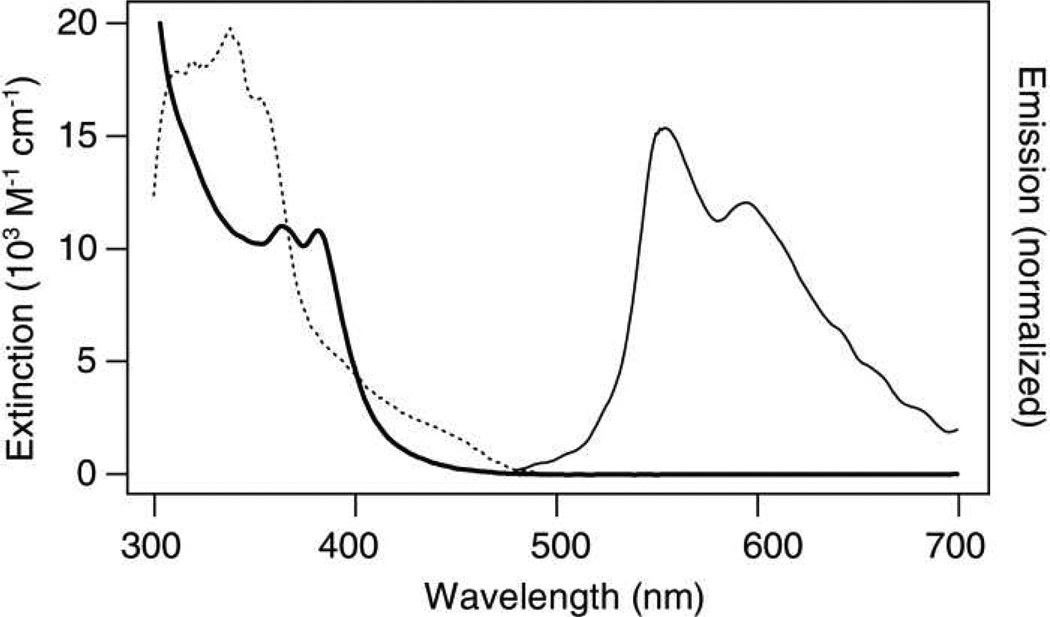

Spectroscopically, Re resembles other dppz-bearing tricarbonyl Re complexes (Figure 2).36–39,45–51 The complex displays absorption maxima at 364 nm and 382 nm in acetonitrile (ε ≈ 11,000 M−1 cm−1),37,39 with a weak tail extending into the visible region. The emission spectrum (λex = 355 nm) in acetonitrile is bifurcated, exhibiting maxima at 555 nm and 595 nm. The excitation spectrum of Re in acetonitrile (λem = 550 nm) indicates the evolution of prominent luminescence at 570 nm upon excitation between 300 nm and 370 nm, with less emission at higher excitation wavelengths. In aqueous solution, the complex behaves as a DNA light switch,35 emitting only in the presence of DNA. The luminescence spectrum of the complex bound to DNA displays a maximum at 570 nm and a shoulder near 610 nm. Interestingly, when bound to a 30-mer consisting of only G•C base pairs, emission of this complex is almost completely quenched.52 The persistent luminescence of Re in the constructs studied here may be due to the lack of guanine adjacent to the Re binding site or to sequence-specific differences in binding. The photophysical properties of Rh and Ir have been described.29,40

Figure 2.

UV/visible steady-state characteristics of [Re(CO)3(dppz)(py′)]+. The absorbance spectrum (bold), emission spectrum (λex = 355 nm; solid), and excitation spectrum (λem = 570 nm; dotted) of the complex (18 µM) in degassed acetonitrile are shown.

Electrochemistry

In order to compare the energetics of the three complexes, the electrochemical behavior of the carboxylic acid-terminated Re, as well as that of the related ethyl ester, [Re(CO)3(dppz)(ethyl 3-(pyridin-4-yl)propanoate)]+ (Re-OEt), was probed by CV. The CV trace of Re shows several overlapping peaks upon reduction and one sharp peak upon reoxidation, indicating aggregation of the complex at the electrode surface, while the CV of Re-OEt is much cleaner, showing one reversible redox wave at −850 mV (Figure S1). Because the carboxylate functionality is so far removed from the metal center, the ground state redox properties of the ester are expected to be identical to those of the carboxylic acid. Further reduction of Re-OEt to −1.8 V shows several additional irreversible reduction waves.

The excited state reduction potential of Re-OEt, E°(*Re+/Re0), was estimated using the formula

where E00 is the zero-zero excited-state energy and E°(Re+/Re0) is the ground state reduction potential.53 Considering that DNA-mediated CT may occur from several excited states in Re, depending on the relative rates of CT and conversion between excited states,45 E00 is best approximated as a range of values. The lower bound for E00 can be estimated as the emission maximum (570 nm in aqueous solution, or 2.18 eV), and the upper bound can be estimated as the crossover point between the emission and excitation spectra (480 nm, or 2.58 eV). Thus, for E°(Re+/Re0) = −850 mV, E°(*Re+/Re0) is estimated to lie between 1.33 V and 1.73 V. Considering the redox potentials of the base nucleosides (E°[G•+/G] = 1.29 V; E°[A•+/A] = 1.42 V; E°[T•+/T] = 1.6 V; E°[C•+/C] = 1.7 V),12 the oxidation strength of excited Re, as well the oxidation strengths of excited Rh (E°[*Rh3+/Rh2+] = 2.0 V vs. NHE)54 and Ir (E°[*Ir+/Ir0] = 1.7 V vs. NHE),29 should be sufficient to oxidize guanine.

Spectroelectrochemistry

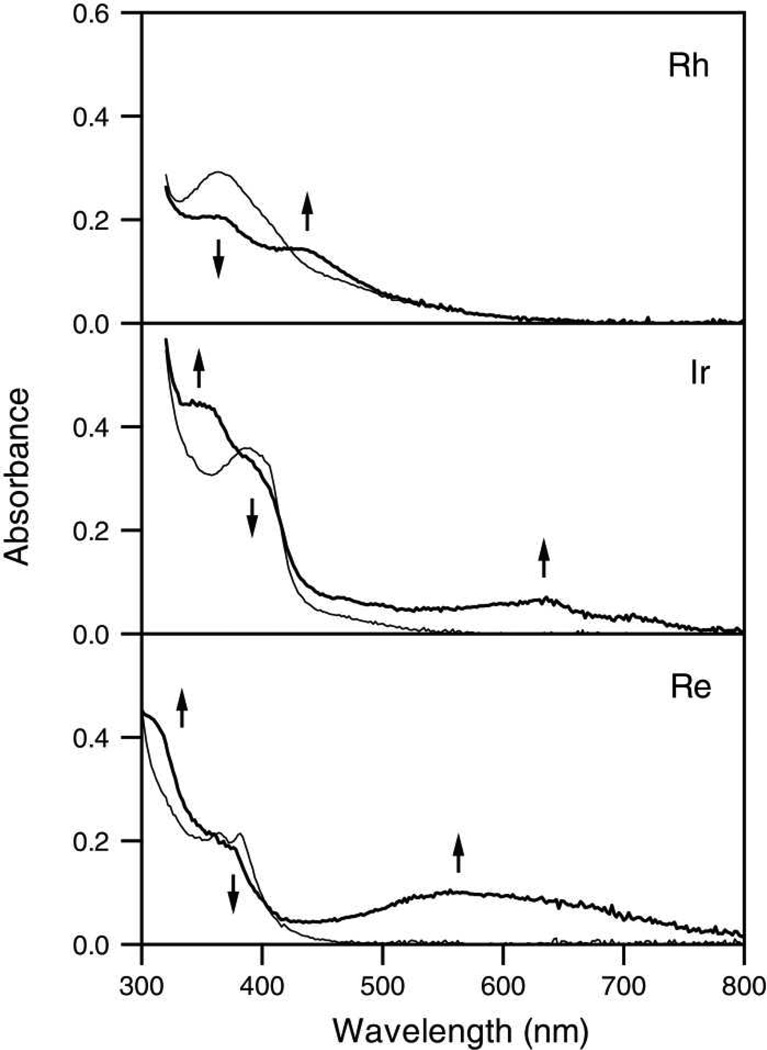

Absorbance spectra of the reduced metal complexes were determined using spectroelectrochemistry. Spectra of saturated solutions of metal complexes in organic solvents were recorded at regular time intervals during reduction. For Rh and Ir in 0.1 M TBAH/DMF, the potential was held at < −1.0 V vs. Ag/AgCl. For Re in 0.1 M TBAH/CH3CN, the potential was held at −1.25 V vs. Ag/AgCl. These potentials are sufficient for single-electron reduction of the complexes. Figure 3 shows the initial ground state spectrum of each sample, as well as the spectrum resulting from exhaustive reduction. For all three samples, reduction causes a decrease in the intensity of the most prominent near-UV band, with the concomitant appearance of broad bands at lower energies. In the spectra of Ir and Re, absorption bands also appear at higher energies. For Ir, subsequent oxidation at 0 V resulted in quantitative regeneration of the initial species, but Rh and Re showed only incomplete (~95%) recovery. These results indicate that the reduction of Ir, but not that of Rh or Re, is completely reversible on the timescale of the experiment (~10 s). Even so, electrogenerated side products observed in spectroelectrochemistry experiments are not expected to interfere in time-resolved spectroscopic experiments employing fast laser pulses.

Figure 3.

Steady-state UV/visible absorbance spectra of metal complexes before (thin line) and after (thick line) reduction by bulk electrolysis. Top: 16 µM [Rh(phi)2(bpy′)]3+ in DMF; middle: 12 µM [Ir(ppy)2(dppz′)]+ in DMF; bottom: 20 µM [Re(CO)3(dppz)(py′-OEt)]+ in acetonitrile. Arrows indicate changes in the spectra upon reduction.

Design and Synthesis of Metal Complex-DNA Conjugates

In order to better understand the interactions between metal complexes and DNA, and the ability of metal complexes to oxidize DNA, three metal complex-DNA conjugates were synthesized. The three conjugates contain identical DNA sequences, and the metal complex in each conjugate is covalently tethered to one end of the duplex via a long alkyl linker. The structures of the complexes and conjugates are shown in Figure 1. The tether in each case is designed to provide considerable conformational flexibility, allowing the complexes to bind DNA as they would in the absence of the covalent linker. However, the tether is not sufficiently long to allow for binding at sites past three base pairs from the end of the duplex, assuming intercalation from the major groove.55 By limiting the position at which each complex is free to bind, it is possible to control the distance between the photooxidant and the low potential 5′-GG-3′ hole trap, negating possible effects of differential distance on the yield and kinetics of DNA CT. Notably, the metal binding site and the 5′-GG-3′ trap are separated by at least five base pairs (17 Å), so oxidation at the guanine doublet is presumed to be DNA-mediated. Since identical DNA sequences are used in all three conjugates, each complex experiences a similar electronic environment when bound. In order to increase the yield of long-range oxidative damage, inosine, rather than guanine, has been incorporated at the metal binding site. Due to its relatively low redox potential (1.29 V vs. NHE12), guanine is easily oxidized, and the radical formed can participate in facile back electron transfer (BET) to regenerate the initial state of the system.56 Inosine, although structurally similar to guanine, has a higher redox potential (1.5 V vs. NHE18) and is not oxidized as readily. These considerations ensure that the distance of DNA CT and the environment of the metal complex are the same in the three conjugates.

Previous experiments have shown that all three complexes bind DNA by intercalation, as evidenced by hypochromism and a red shift in the near-UV absorption upon addition of DNA.29,37,57 Support for this binding mode is also provided by an increase in the DNA duplex melting temperature in the presence of the metal complexes (Table 1), since π-stacking interactions between the bases and the intercalating ligands are expected to stabilize the duplexes. Interestingly, the presence of the covalent linker on the intercalating ligand of Ir does not inhibit intercalation of this complex. Presumably, the complex interacts with the DNA bases during annealing, so that when the duplex is formed, the construct resembles a threaded needle, with the metal center on one side of the duplex, the tether on the other, and the intercalated dppz ligand connecting them.29

Table 1.

Melting Temperature and Guanine Oxidation Yield for Metal Complex-DNA Conjugates.

Measured using 2 µM duplexes in buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl; pH 7.5); uncertainty in Tm estimated as 1 °C.

Guanine oxidation yield determined via PAGE analysis; reported as the combined counts at both guanine sites of the 5′-GG-3′ doublet after 120 min irradiation relative to counts per lane, and normalized to the amount of damage observed for Rh-DNA.

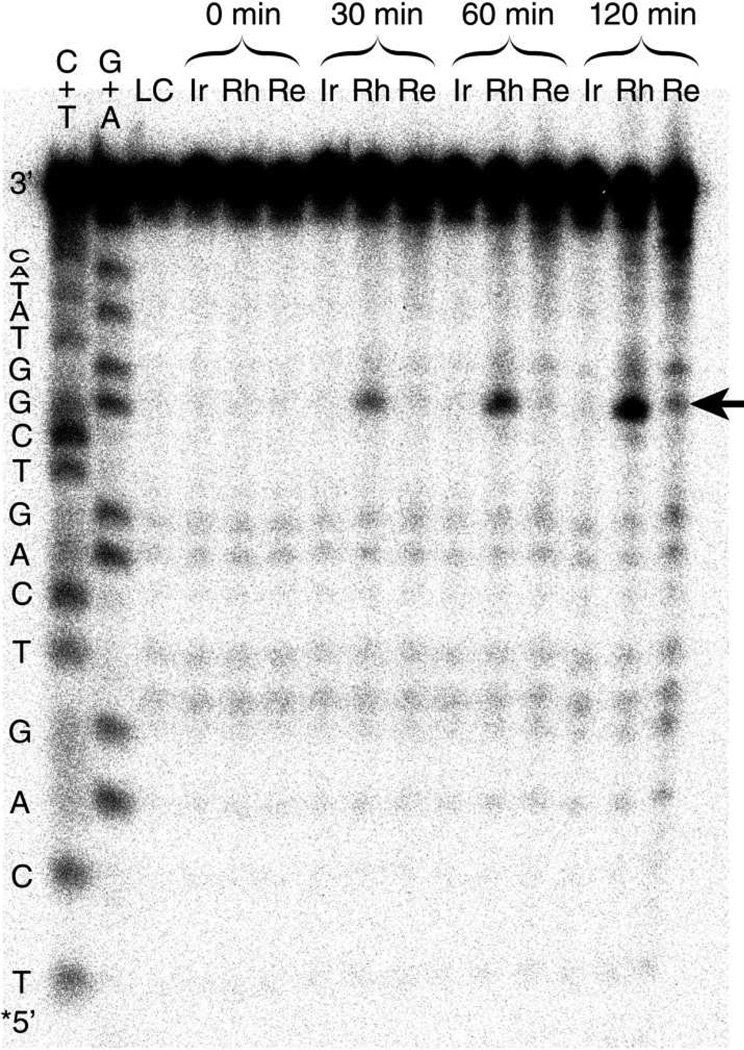

Guanine Oxidation Observed by PAGE

An assay for guanine damage was carried out in order to establish directly the ability of Re to oxidize guanine and to enable comparison between the yield of oxidation observed upon excitation of each of the three metal complexes. Figure 4 shows the result of the photodamage experiment. Irradiation of DNA in the presence of each metal complex results in damage, although to varying degrees. Most prominently, extensive damage at the 5′-G of the 5′-GG-3′ doublet in Rh-DNA appears after only 30 minutes of irradiation. At this time point, damage in Ir-DNA is undetectable, and damage in Re-DNA is faint. Damage accrues linearly in all three samples with increasing irradiation time (Figure S2). After 120 minutes of irradiation, damage in Ir-DNA has accumulated beyond the baseline, and damage in Re-DNA has become pronounced. The damage yield at both guanines of the 5′-GG-3′ site increases as Ir-DNA < Re-DNA < Rh-DNA (Table 1). The absolute quantum yield of damage could not be determined accurately due to the nature of the sample geometry, but these values are expected to comparable to those observed in similar conjugates between DNA and [Rh(phi)2(bpy′)]3+ (2 × 10−6).17 Interestingly, the amount of damage does not correlate with the number of photons absorbed per sample. Based only on absorbance, Ir, which has a higher extinction coefficient (ε405 = 30,600 M−1 cm−1)29 than Rh (ε390 = 19,000 M−1 cm−1)58 and Re (ε388 = 11,000 M−1 cm−1),37,39 and which has better spectral overlap with the excitation source, would be expected to be the most efficient photooxidant. Additionally, the pattern of damage differs in the three conjugates. While the Rh-DNA sample shows damage mainly at the 5′-G of the guanine doublet, the Re-DNA sample shows comparable damage at both guanines of the doublet, as well as pronounced damage close to the presumed complex binding site. This pattern of cleavage for Re-DNA does not appear to be the result of sensitization of singlet oxygen, given the lack of damage at T’s and the absence of damage enhancement in D2O reported elsewhere.38 Importantly, at the duplex concentrations used in these experiments (2 µM), interduplex guanine oxidation is not expected to be significant at the concentrations used here.19 These results indicate that although each complex has the ability to carry out guanine oxidation at long range from the excited state, competing reaction pathways operate differently in the three systems.

Figure 4.

PAGE analysis following photooxidation of guanine by [Rh(phi)2(bpy′)]3+, [Ir(ppy)2(dppz′)]+, and [Re(CO)3(dppz)(py′)]+ covalently bound to DNA. Metal-DNA conjugates (2 µM in buffer: 10 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) were irradiated for 0, 30, 60, or 120 min. DNA strand cleavage at sites of oxidation was achieved by treatment with 10% piperidine. Cleavage products were separated by 20% PAGE and visualized by phosphorimagery. C+T and G+A: Maxam-Gilberts sequencing lanes; LC: light control (no metal complex); Ir, Rh, Re: the corresponding metal-DNA conjugates, irradiated for the indicated times. The DNA sequence is shown along the left edge of the gel. The position of the radiolabel is indicated by *. The 5′-G of the 5′-GG-3′ doublet is indicated by an arrow.

Transient Absorption Spectra

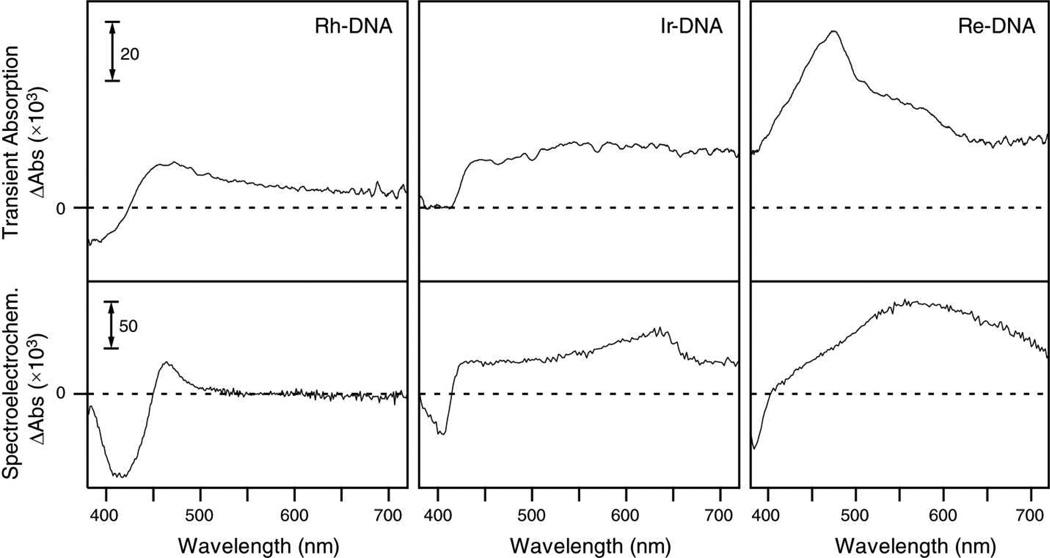

TA spectra of the three conjugates are shown in Figure 5. The spectra illustrate the difference in absorbance observed 60 ns after 355 nm excitation of 15 µM aqueous buffered samples (10 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl; pH 7.5). In general, the three conjugates display similar difference spectra. Rh-DNA shows a strong bleach near 390 nm due to depletion of the ground state, as well as a positive transient centered at 460 nm with a long tail extending into the red. This is similar to the TA spectrum obtained for [Rh(phi)2(bpy)]3+ in water 30 ns after 420 nm excitation, except that in the latter case, an additional broad transient was observed centered near 680 nm.54 Ir-DNA also shows a strong transient that is red-shifted from the ground state absorbance. However, in the case of Ir-DNA, the band is quite broad and featureless, extending into the near-IR region. No bleach was observed in the transient spectrum of Ir-DNA at 405 nm. An attempt to observe the excited state difference spectrum of [Ir(ppy)2(dppz)]+ in DMF after 355 nm (~10 ns pulse duration) yielded only broad absorption throughout the visible region. Finally, Re-DNA shows a strong, broad absorption throughout the visible region with a maximum near 460 nm and a shoulder near 550 nm, similar to what was observed for the excitation of [Re(CO)3(dppz)(py)]+ in acetonitrile upon 400 nm excitation.45 While the intensity of the TA signal is comparable for Rh-DNA and Ir-DNA, the signal for Re-DNA at 60 ns is over twice as strong.

Figure 5.

Comparison between transient absorption difference spectra and spectroelectrochemical difference spectra. Top: TA spectra obtained 60 ns after excitation at 355 nm of 15 µM [Rh(phi)2(bpy′)]3+, [Ir(ppy)2(dppz′)]+, and [Re(CO)3(dppz)(py′)]+ covalently bound to DNA. Bottom: spectroelectrochemistry difference spectra for (from left to right) 16 µM [Rh(phi)2(bpy′)]3+ in DMF, 12 µM [Ir(ppy)2(dppz′)]+ in DMF, and 20 µM [Re(CO)3(dppz)(py′-OEt)]+ in acetonitrile.

Difference spectra between the reduced and non-reduced metal complexes in organic solvents, measured by spectroelectrochemistry, are also shown in Figure 5. Interestingly, there are several similarities between these difference spectra and those obtained by TA. For example, while the spectroelectrochemistry difference spectrum of Rh does not show the extended tail to long wavelengths observed in the TA spectrum of Rh-DNA, the positions of the bleaches and of the absorbance maxima are roughly the same. Similarly, while the spectroelectrochemistry difference spectrum of Ir shows a bleach at 405 nm and the TA difference spectrum of Ir-DNA does not, bands in both spectra exhibit a sharp increase in absorbance near 420 nm and are relatively flat throughout the visible region. Finally, although the electrochemical difference spectrum of Re exhibits a bleach near 390 nm while the TA difference spectrum of Re-DNA does not, and although their band shapes are different, both absorb strongly into the near-IR. Although the spectra of metal complexes bound to DNA are not expected to be completely analogous to those observed in organic solvents due to differences in the solvation environments, the spectroelectrochemistry difference spectra and the TA difference spectra show remarkable similarities. This result suggests that both techniques probe similar molecular states.

Kinetics

The emission and TA lifetimes of the metal complexes in acetonitrile are quite different from those of the DNA conjugates in aqueous solution. Kinetic parameters obtained from least-squares analysis are shown in Table 2. In general, lifetimes of the three complexes differ by several orders of magnitude. In acetonitrile, Rh and Ir are non-emissive upon excitation at 355 nm, but Re shows strong emission at 570 nm that decays biexponentially with lifetimes of 180 ns and 17 µs. The behavior of Re-OEt is similar, although its emission decay lifetime is consistently observed to be shorter than that of Re, even after exhaustive degassing of the solvent via the freeze-pump-thaw method. The lifetimes of non-emissive excited states can be inferred from TA measurements. Excitation of Rh in acetonitrile at 355 nm results in a weak transient signal at 460 nm (the TA maximum) with a lifetime of 81 ns. Similarly, excitation of Ir gives a transient at 540 nm that decays with a lifetime of 270 ns. Presumably, the 19 µs decay observed by TA for Re corresponds to the 17 µs decay observed through emission.

Table 2.

Least-Squares Parameters for Fits to Time-Resolved Emission and TA Data.

| Speciesa | Emission | Transient Absorption | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| λprobe, nm | τ, ns (% contribution)b | λprobe, nm | τ, ns (% contribution)b | |

| Rh | — | — | 460 | 81 |

| Ir | — | — | 540 | 270 |

| Re | 570 | 180 (12), 17000 (88) | 475 | 19000 |

| Re-OEt | 570 | 210 (11), 7600 (89) | 475 | 8000 |

| Rh-DNA | — | — | 460 | 73 (79), 1100 (21) |

| Ir-DNA | — | — | 540 | 5.9 (94), 280 (6) |

| Re-DNA | 570 | 265 | 475 | 3200 (37), 35000 (63) |

Complexes were dissolved in deaerated acetonitrile; metal complex-DNA conjugates were prepared in buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl; pH 7.5).

Uncertainty in lifetimes estimated as 10%; values in parentheses correspond to the pre-exponential coefficients an following normalization of the signal.

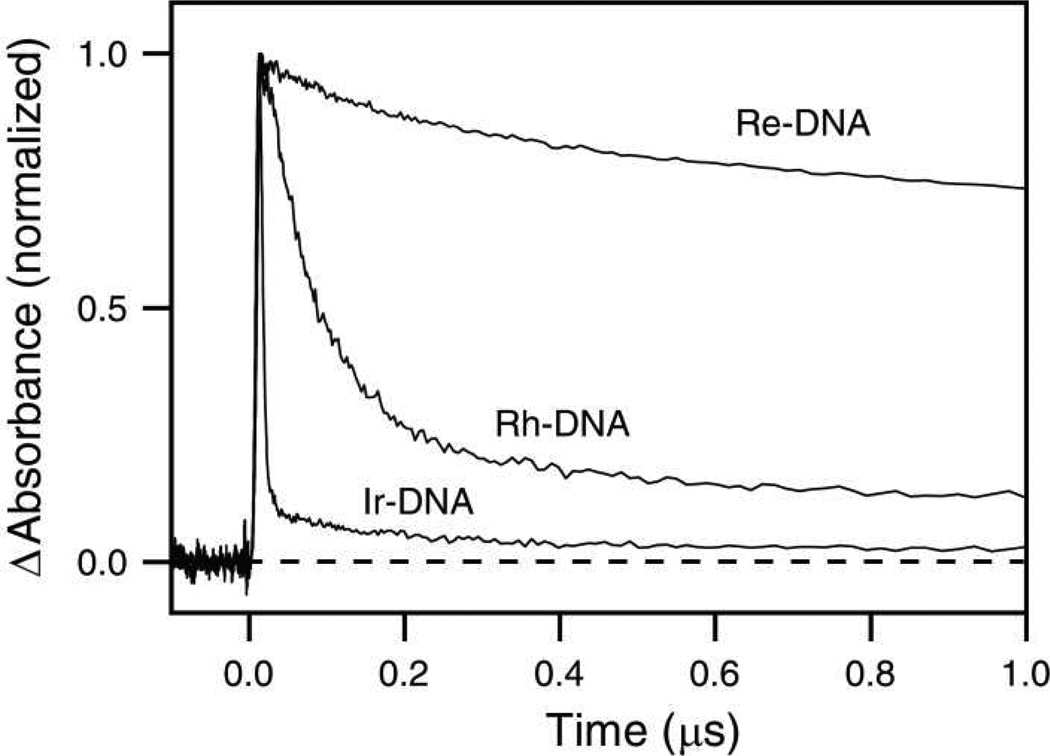

TA decays for the three metal complex-DNA conjugates are shown in Figure 6. Again, the lifetimes of the transients differ greatly between the conjugates. In particular, transient signals measured for systems containing DNA-conjugated Rh and Re have much longer lifetimes than those observed in organic solvents. For Rh-DNA, the best fit gives lifetimes of 73 ns and 1.1 µs. For Re-DNA, photoexcitation yields a more persistent transient signal, with lifetimes of 3.2 µs and 35 µs. Ir-DNA, on the other hand, exhibits a very prominent (94%), short-lived component with a lifetime on the order of 6 ns and a longer-lived component with a lifetime of 280 ns. The spectroscopic differences observed between the three conjugates underscore the diversity of their photophysical behavior and the differences in their interactions with DNA.

Figure 6.

Transient absorption decay traces for 15 µM [Rh(phi)2(bpy′)]3+ (460 nm), [Ir(ppy)2(dppz′)]+ (540 nm), and [Re(CO)3(dppz)(py′)]+ (475 nm) covalently bound to DNA following excitation at 355 nm.

DISCUSSION

Excited State Assignments

The steady-state photophysical properties of Rh, Ir, and Re resemble those of analogous complexes. For example, good agreement between the TA spectra of several phi-containing complexes following excitation at 420 nm has enabled assignment of the 390 nm absorption band in [Rh(phi)2(phen)]3+ to a combination of π → π* (phen) and π → π* (phi) transitions, which quickly relax (< 60 ns) to an intraligand charge transfer (ILCT) state in which electron density has shifted to the phenanthrene portion of the phi ligand.54 Due to the similarities between the photophysics of [Rh(phi)2(phen)]3+ and [Rh(phi)2(bpy)]3+, a similar process is expected in the latter complex and in its tether-functionalized analogue, Rh. The absorption profiles of Re and Ir are also attributed to a mixture of several transitions. The close resemblance between the absorption spectra of complexes of the type fac-[Re(CO)3(dppz)(L)]n+ and the free dppz ligand has suggested that the absorption maxima observed near 360 nm and 380 nm result from a π → π* (dppz) IL transition.37,45 However, the long, low-intensity tail into the visible region, as well as a slight red shift of these bands compared to the free dppz ligand, indicate the presence of an underlying dπ (Re) → π* (dppz) metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) transition.36,45 Re shares these characteristics, suggesting that irradiation with light in the near-UV populates several excited states in this species, namely MLCT states and IL transitions centered on the phenanthrene (ILphen) and phenazine (ILphz) parts of dppz.45,46,48,49,59 Over time, the initially excited singlet states are expected to decay to 3MLCT, 3ILphen and 3ILphz states.45 Similarly, Ir exhibits a strong absorption band in the near-UV in acetonitrile, as well as a weak, broad band centered near 450 nm.29 As in Re, the higher energy bands are likely due to an IL transition on dppz, while the lower energy band is probably MLCT in character. Thus, in all three complexes, a MO of the intercalating ligand is populated upon excitation.

Reduced Metal Complexes

The identity of reduced Rh may be determined by comparing it with the reduced states of other phi complexes. For example, E°(Ru2+/Ru+) in [Ru(bpy)2(phi)]2+ appears at a more positive potential than in [Ru(bpy)3]2+, indicating that in complexes with mixed bpy and phi ligands, phi is reduced more readily than bpy.60 The product of single-electron reduction of Rh can therefore be assigned as [RhIII(phi)(phi•−)(bpy′)]2+. The reduced states of Re and Ir can be assigned based on analogy to other complexes ligated by dppz. It has been shown that electrochemical reduction of dppz results in the addition of an electron to the phenazine-centered orbital of dppz rather than the α-diimine-centered orbitals that are populated upon excitation to the MLCT state.61 Spectroscopically, reduction of dppz is manifested as the appearance of an absorption band centered near 570 nm that absorbs throughout the visible spectral range.61 The resemblance between the difference spectrum of reduced dppz and that of reduced Re and Ir suggests that reduction of Re and Ir results in addition of an electron to the phenazine-centered orbital of the dppz ligand as well. These assignments are consistent with those of reduced [Os(phen)2(dppz)]2+ and [Ru(dppz)3]2+, which show similar spectral behavior.62 The reduced states of the three complexes, therefore, also involve the intercalating ligand. The participation in photophysical and electrochemical process of the intercalating ligand, which is intimately associated with the DNA base stack, may be necessary for efficient DNA-mediated CT to proceed.63

Comparison of Spectroelectrochemical and TA Difference Spectra

The TA difference spectra of Rh-DNA and Re-DNA are similar to spectra observed upon photoexcitation of [Rh(phi)2(bpy)]3+ in water54,64 and [Re(CO)3(dppz)(py)]+ in acetonitrile,45 respectively. However, the TA spectra of the three conjugates also exhibit features in common with the reduced state spectra observed by spectroelectrochemistry. Considering the favorable driving force for guanine oxidation by excited Rh, Ir, and Re, the oxidative damage observed in PAGE experiments, and numerous reports in the literature confirming the ability of similar complexes to oxidize guanine from a distance,19,28,30,64–66 the observation of reduced states in the TA spectra is expected. In each system, oxidation of guanine by the photoexcited metal complex must result in the reduction of the metal complex. The observed TA spectra, therefore, likely consist of mixtures of excited and reduced states.

Analysis of the TA lifetimes supports the formation of a mixture of states. In all three samples, DNA-mediated CT is expected to occur at a rate faster than the time resolution of the instrument.27,67,68 In Rh-DNA, the TA decay exhibits two lifetimes, the shorter of which is within error of the TA lifetime of Rh in acetonitrile and can therefore be ascribed to decay from the excited state of complex molecules that are not well coupled to the DNA base stack at the time of excitation. However, as is even apparent by gel analysis, Rh-DNA shows the highest level of guanine damage. This supports the idea that DNA-mediated CT is fast compared to the TA instrumentation; eighty percent of the decay appears from the excited state as unquenched and uncoupled, but a faster static quenching must occur. This static quenching component reflects DNA-mediated CT that gives rise to the guanine damage. The second lifetime component, which is over an order of magnitude slower, is not observed in the absence of DNA, and is attributed to absorption of the reduced state.

The TA decay of Ir-DNA is also biexponential; however, in this case, it is the lifetime of the longer-lived component that shares similarity with the lifetime of Ir in acetonitrile. Here, the interpretation is slightly different. Considering the driving force for guanine oxidation, it is still probable that the reduced state of the complex is formed in Ir-DNA, but that its lifetime is much shorter in Ir-DNA than the lifetime of the reduced state in Rh-DNA. The longer lifetime in Rh-DNA and the shorter lifetime in Ir-DNA, then, reflect the rates of BET in these systems. Importantly, this interpretation is consistent with the results of the PAGE experiment: the low yield of guanine damage in Ir-DNA is due to fast BET in that system.

In Re-DNA, no component is observed which matches the excited state lifetime of Re or Re-OEt, suggesting that the DNA environment affects the photodynamics of this complex. However, excitation in the presence of DNA does lead to formation of a long-lived transient. A similar result was observed for [Re(CO)3(dppz)(4-methylpyridine)]+ in the presence of calf thymus DNA.37 Interestingly, in that case, the transient decay was also biphasic in the presence of DNA, and as the DNA concentration was increased, the longer time component became more dominant. Both phases were assigned to formation of the 3IL(dppz) excited state, while the ten-fold difference in lifetime between the two phases was attributed to two different binding modes or differences in solvent accessibility. While these factors can influence excited state lifetimes, it is probable that excited state quenching by guanine to form the reduced metal complex also occurs, similar to what we propose for Ir-DNA and Rh-DNA.

A Model for DNA-Mediated Guanine Oxidation

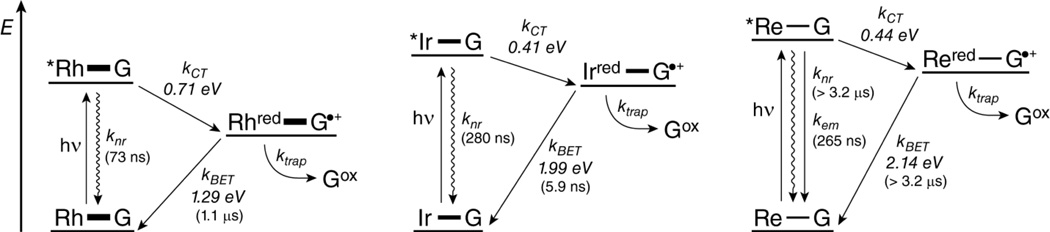

From these considerations, a model for the DNA-mediated oxidation of guanine by intercalating photooxidants can be constructed (Figure 7). Prior to excitation, the system exists as an equilibrium of two populations: one in which the metal complex is poorly coupled to the base stack (not shown in Figure 7) and one in which the complex is well coupled. Excitation of the metal complex may be followed by luminescent or non-radiative relaxation, or (in the well coupled system) by charge injection to form the reduced metal complex and the guanine radical cation. From the charge-separated state, the formation of permanent guanine oxidation products by reaction with water or oxygen competes with BET. If charge injection is slow (due to poor coupling between the oxidant and the DNA base stack), decay to the ground state will preclude the eventual formation of guanine damage. If charge injection is fast, the yield of permanent damage may still be attenuated by facile BET. This mechanism combines the results observed by PAGE and transient absorption, and it is expected to be general for any intercalating metal complex photooxidant.

Figure 7.

Proposed model for the DNA-mediated oxidation of guanine by metallointercalating photooxidants. Conjugates are represented as M—G, where the thickness of the line connecting M and G represents the extent of coupling between the metal complex and the base stack. Wavy arrows represent non-radiative decay from the excited state (*Rh, *Ir, or *Re). Reduced metal complex states are represented as Mred. The guanine radical cation (G•+) is distinguished from permanent guanine oxidation products (Gox). Energy level differences are to scale. Thermodynamic driving forces are shown for charge injection and back electron transfer (BET), and lifetimes are shown in parentheses. In each scheme, the equilibrium with the poorly coupled system is omitted for clarity.

Factors Affecting the Efficiency of Guanine Oxidation

According to the model, the quantum yield of guanine damage, ΦGox, can be expressed as

where ΦCT is the quantum yield of CT, ktrap and kBET are the rates of hole trapping (to form permanent guanine products) and BET, respectively, and

depends on F, the fraction of conjugates that exists in a CT-active conformation at the time of excitation, and the rates of CT (kCT), emission (kem, if applicable), and non-radiative decay processes (knr). Here, kCT refers to the intrinsic rate of CT through DNA, assuming a maximally coupled system, and dynamic aspects of the equilibrium between well-coupled and poorly coupled systems have not been considered. Using the definition of quantum yield, the amount of damage observed, NGox, can be expressed as a function of Nabs, the number of photons absorbed:

This function nicely summarizes the many factors that affect the yield of guanine damage. A greater number of photons absorbed, a greater fraction of the population in a CT-active conformation, and faster rates of CT and trapping increase the yield; conversely, faster rates of emission, non-radiative decay, and BET decrease the yield.

The extent of electronic coupling between the photooxidant and the hole acceptor is expected to have a strong influence on the amount of damage observed. Intercalation confers superior coupling between the oxidant and the DNA base stack. Functionally, the intercalated ligand “becomes” an additional base, linking the electronic system of the metal complex to that of the base stack. Poor coupling, therefore, disrupts this linkage and decreases the rate of charge injection. Factors that affect the degree of coupling between the oxidant and the base stack include the planarity and size of the intercalating ligand,63,69 the charge of the complex, the dynamics of the oxidant within the intercalation site,68 and the size, shape, and hydrophobicity of the ancillary ligands.64,70,71 Experimentally, the extent of coupling of the metal complex to the base stack is reflected in part by the increase in DNA melting temperature in the presence of the intercalator and by the extent of hypochromism associated with binding. From melting temperature data (Table 1), coupling in the conjugates increases as Re-DNA < Ir-DNA < Rh-DNA. The stronger coupling observed in Rh-DNA is likely due to its higher charge (+3 for Rh, compared to +1 for Ir and Re), as well as the use of only the diastereomer bearing the tighter binding Δ-isomer.

In general, the extent of coupling between the bases themselves also affects the yield of damage. Indeed, the efficiency of DNA CT depends on the DNA sequence72–74 and base motions,75,76 and examination of DNA CT in solution77 and through DNA monolayers on gold surfaces78–80 has illustrated the acute sensitivity of DNA CT to intervening mismatches and lesions. In our tethered systems, such sequence-dependent and dynamic effects are not expected to cause differences in the guanine oxidation yield, since they will have equal bearing on the results for each of the three conjugates. Variations in CT associated with distance have not been determined in these experiments but would be expected to be comparable for the different assemblies. Not only do the tethered binding positions appear to be comparable based on model building, but more importantly, for well coupled probes the distance dependence of DNA-mediated CT has been found to be equally shallow independent of the probe.19,31,81,82

The rate of any CT process is related to the thermodynamic driving force according to Marcus theory.83 For the CT reaction, thermodynamic analysis predicts that *Rh should be the strongest oxidant (E°[*Rh3+/Rh2+] = 2.0 V vs. NHE54), while *Ir (E°[*Ir+/Ir0] = 1.7 V vs. NHE,29 with E00 calculated as the crossover point between the absorbance and emission spectra) is expected to yield a similar amount of damage as *Re (E°[*Re+/Re0] = 1.73 V, calculated in a similar way), but this trend is not observed. One factor that contributes to the greater yield in Re-DNA is the much longer lifetime (slower kem and knr) observed for the excited state of Re (Table 2). Besides decreasing the denominator in Eq. 3, a longer excited state lifetime will increase F, since more conformational states of DNA can be sampled prior to relaxation of the excited state. This increases the probability of achieving a CT-active conformation within the excited state lifetime. Another contributing factor is facile BET in Ir-DNA, which deactivates the charge-separated precursor before damage can occur. TA experiments have shown that in the absence of BET, the lifetime of the guanine radical extends into the millisecond regime.56 Any process that neutralizes the radical within its lifetime will decrease the yield of permanent damage.17 As an extreme example, BET completely prevents the formation of oxidative guanine damage when thionine is used as an intercalating photooxidant, despite the favorable driving force for this reaction (~0.7 eV).84 The driving force for BET in each of the conjugates increases approximately as Rh-DNA (1.29 eV)54 < Ir-DNA (1.99 eV)29 < Re-DNA (2.14 eV). Due to the large free energy changes associated with BET, these processes are expected to lie in the Marcus inverted region.85 From these considerations alone, the rate of BET is therefore predicted to be fastest in Rh-DNA and slowest in Re-DNA. The observation of faster BET in Ir-DNA than in Rh-DNA by TA spectroscopy indicates that other factors, such as reorganization energy, may affect the rate of BET. Interestingly, effective coupling is needed for efficient BET as well as CT. In Re-DNA, poorer coupling to the base stack could decrease the efficiency of BET, further enhancing the yield of guanine damage in this conjugate.

The trend observed in the guanine oxidation assay can be explained by the interplay of these many factors. The higher yield of damage in the Rh-DNA sample is likely due to the strong driving force for guanine oxidation. For Rh, this value is 0.71 eV, compared to 0.51 eV for Ir-DNA and 0.54 eV for Re-DNA. This strong driving force leads to a fast kCT. The high yield in the Rh-DNA sample is also due to strong coupling, evidenced by the high melting temperature differential observed for Rh-DNA: (8 °C, compared to 7 °C for Ir-DNA and 1 °C for Re-DNA. Presumably, BET in Rh-DNA is offset by these factors. In comparing Ir-DNA and Re-DNA, which have the same intercalating ligand, the same charge, and show a similar driving force for guanine oxidation, other factors become important. In these conjugates, the stronger coupling of Ir to the base stack results in faster rates of CT and BET, decreasing the yield of damage, while the longer excited-state lifetime and strongly inverted BET in Re-DNA increase damage.

CONCLUSIONS

The electrochemical and photophysical properties of three metal complexes and their DNA conjugates have been observed in the same sequence context. All of the complexes have high excited state reduction potentials, and gel electrophoresis experiments indicate that guanine oxidation by the excited complexes can occur via DNA CT. Comparison between spectroelectrochemical difference spectra and TA difference spectra suggests that photoexcitation of metal complex-DNA conjugates results in a mixture of excited and reduced metal states, allowing for the observation of charge-separated intermediates and measurement of the relative rates of charge recombination (BET). The ability to oxidize guanine indicates effective coupling of all of the complexes to the DNA base stack, signifying that these or similar complexes could be useful for triggering oxidation in more complex experimental systems.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to the NIH (GM49216) for financial support. E.D.O. also thanks E.D.A. Stemp, J.R. Winkler, and B. Elias for technical assistance and fruitful discussions.

Footnotes

Supporting Information. Cyclic voltammetry traces of Re and Re-OEt in acetonitrile, accumulation of guanine damage with irradiation. This material is available free of charge via the internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Møller P, Folkmann JK, Forchhammer L, Bräuner EV, Danielsen PH, Risom L, Loft S. Cancer lett. 2008;266:84–97. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooke MS, Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Lunec J. FASEB J. 2003;17:1195–1214. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0752rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klaunig JE, Kamendulis LM. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2004;44:239–267. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishikawa M. Cancer lett. 2008;266:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Loon B, Markkanen E, Hübscher U. DNA repair. 2010;9:604–616. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovell MA, Markesbery WR. J. Neurosci. Res. 2007;85:3036–3040. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.David SS, O’Shea VL, Kundu S. Nature. 2007;447:941–950. doi: 10.1038/nature05978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joyce LE, Aguirre JD, Angeles-Boza AM, Chouai A, Fu PK-L, Dunbar KR, Turro C. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:5371–5376. doi: 10.1021/ic100588d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sasmal PK, Saha S, Majumdar R, Dighe RR, Chakravarty AR. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:849–859. doi: 10.1021/ic900701s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hussain A, Saha S, Majumdar R, Dighe RR, Chakravarty AR. Ind. J. Chem. 2011;50:519–530. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Le Gac S, Foucart M, Gerbaux P, Defrancq E, Moucheron C, Kirsch-De Mesmaeker A. Dalton Trans. 2010;39:9672–9683. doi: 10.1039/c0dt00355g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steenken S, Jovanovic SV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:617–618. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Delaney S, Barton JK. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:6475–6483. doi: 10.1021/jo030095y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schuster GB, editor. Topics in Current Chemistry: Long-Range Charge Transfer in DNA I. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valis L, Wang Q, Raytchev M, Buchvarov I, Wagenknecht H-A, Fiebig T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:10192–10195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600957103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanii L, Schuster GB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:11545–11546. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Williams TT, Dohno C, Stemp EDA, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:8148–8158. doi: 10.1021/ja049869y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelley SO, Barton JK. Science. 1999;283:375–381. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5400.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Núñez ME, Hall DB, Barton JK. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:85–97. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Slinker JD, Muren NB, Renfrew SE, Barton JK. Nature Chem. 2011;3:228–233. doi: 10.1038/nchem.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merino EJ, Barton JK. Biochemistry. 2008;47:1511–1517. doi: 10.1021/bi701775s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genereux JC, Boal AK, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:891–905. doi: 10.1021/ja907669c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Augustyn KE, Merino EJ, Barton JK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:18907–18912. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709326104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee PE, Demple B, Barton JK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:13164–13168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906429106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boal AK, Genereux JC, Sontz PA, Gralnick JA, Newman DK, Barton JK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:15237–15242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908059106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barton JK, Olmon ED, Sontz PA. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010;255:619–634. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy CJ, Arkin MR, Jenkins Y, Ghatlia ND, Bossmann SH, Turro NJ, Barton JK. Science. 1993;262:1025–1029. doi: 10.1126/science.7802858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hall DB, Holmlin RE, Barton JK. Nature. 1996;382:731–735. doi: 10.1038/382731a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shao F, Elias B, Lu W, Barton JK. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:10187–10199. doi: 10.1021/ic7014012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shao F, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14733–14738. doi: 10.1021/ja0752437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Elias B, Shao F, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:1152–1153. doi: 10.1021/ja710358p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turner JJ, George MW, Johnson FPA, Westwell JR. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1993;125:101–114. [Google Scholar]

- 33.George MW, Turner JJ. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1998;177:201–217. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vlček A. Top. Organomet. Chem. 2010;29:73–114. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friedman AE, Chambron J-C, Sauvage J-P, Turro NJ, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:4960–4962. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruiz GT, Juliarena MP, Lezna RO, Wolcan E, Feliz MR, Ferraudi G. Dalton Trans. 2007;3:2020–2029. doi: 10.1039/b614970g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stoeffler HD, Thornton NB, Temkin SL, Schanze KS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:7119–7128. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yam VW-W, Lo KK-W, Cheung K-K, Kong RY-C. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1997;14:2067–2072. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yam VW-W, Lo KK-W, Cheung K-K, Kong RY-C. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1995;3:1191–1193. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pyle AM, Chiang MY, Barton JK. Inorg. Chem. 1990;29:4487–4495. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holmlin RE, Dandliker PJ, Barton JK. Bioconjugate Chem. 1999;10:1122–1130. doi: 10.1021/bc9900791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zeglis BM, Barton JK. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:357–371. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boyle PD, Boyd DC, Mueting AM, Pignolet LH. Inorg. Chem. 1988;27:4424–4429. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dempsey JL, Winkler JR, Gray HB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1060–1065. doi: 10.1021/ja9080259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dyer J, Blau WJ, Coates CG, Creely CM, Gavey JD, George MW, Grills DC, Hudson S, Kelly JM, Matousek P, McGarvey JJ, McMaster J, Parker AW, Towrie M, Weinstein JA. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2003;2:542–554. doi: 10.1039/b212628a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dyer J, Creely CM, Penedo JC, Grills DC, Hudson S, Matousek P, Parker AW, Towrie M, Kelly JM, George MW. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2007;6:741–748. doi: 10.1039/b618651c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dyer J, Grills DC, Matousek P, Parker AW, Towrie M, Weinstein JA, George MW. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2002:872–873. doi: 10.1039/b200586g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kuimova MK, Alsindi WZ, Blake AJ, Davies ES, Lampus DJ, Matousek P, McMaster J, Parker AW, Towrie M, Sun X-Z, Wilson C, George MW. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:9857–9869. doi: 10.1021/ic800753f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuimova MK, Sun Z, Matousek P, Grills DC, Parker AW, Towrie M, George MW. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2007;6:1158–1163. doi: 10.1039/b705002j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waterland MR, Gordon KC, McGarvey JJ, Jayaweera PM. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1998;10:609–616. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Waterland MR, Gordon KC. J. Raman Spec. 2000;31:243–253. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olmon ED, Sontz PA, Blanco-Rodríguez AM, Towrie M, Clark IP, Vlček A, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:13718–13730. doi: 10.1021/ja205568r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Juris A, Balzani V, Barigelletti F, Campagna S, Belser P, Von Zelewsky A. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1988;84:85–277. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Turro C, Evenzahav A, Bossmann SH, Barton JK, Turro NJ. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 1996;243:101–108. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dupureur CM, Barton JK. Inorg. Chem. 1997;36:33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stemp EDA, Arkin MR, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:2921–2925. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sitlani A, Long EC, Pyle AM, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:2303–2312. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holmlin RE, Dandliker PJ, Barton JK. Bioconjugate Chem. 1999;10:1122. doi: 10.1021/bc9900791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kuimova MK, Alsindi WZ, Dyer J, Grills DC, Jina OS, Matousek P, Parker AW, Porius P, Sun XZ, Towrie M, Wilson C, Yang J, George MW. Dalton Trans. 2003:3996–4006. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Belser P, von Zelewsky A, Zehnder M. Inorg. Chem. 1981;20:3098–3103. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fees J, Kaim W, Moscherosch M, Matheis W, Klíma J, Krejčík M, Záliš S. Inorg. Chem. 1993;32:166–174. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fees J, Ketterle M, Klein A, Fiedler J, Kaim W. Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions. 1999:2595–2600. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Delaney S, Pascaly M, Bhattacharya PK, Han K, Barton JK. Inorg. Chem. 2002;41:1966–1974. doi: 10.1021/ic0111738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Turro C, Hall DB, Chen W, Zuilhof H, Barton JK, Turro NJ. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:5708–5715. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hall DB, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:5045–5046. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Elias B, Creely C, Doorley GW, Feeney MM, Moucheron C, Kirsch-DeMesmaeker A, Dyer J, Grills DC, George MW, Matousek P, Parker AW, Towrie M, Kelly JM. Chem. Eur. J. 2008;14:369–375. doi: 10.1002/chem.200700564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Arkin MR, Stemp EDA, Holmlin RE, Barton JK, Hörmann A, Olson EJ, Barbara PF. Science. 1996;273:475–480. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5274.475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wan C, Fiebig T, Kelley SO, Treadway CR, Barton JK, Zewail AH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:6014–6019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ren J, Jenkins TC, Chaires JB. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8439–8447. doi: 10.1021/bi000474a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Terbrueggen RH, Johann TW, Barton JK. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:6874–6883. doi: 10.1021/ic980837j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ernst RJ, Song H, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2359–2366. doi: 10.1021/ja8081044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stemp EDA, Holmlin RE, Barton JK. Inorganica Chimica Acta. 2000;297:88–97. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Williams TT, Odom DT, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:9048–9049. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shao F, Augustyn KE, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:17445–17452. doi: 10.1021/ja0563399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.O’Neill MA, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:13234–13235. doi: 10.1021/ja0455897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.O’Neill MA, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:11471–11483. doi: 10.1021/ja048956n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bhattacharya PK, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:8649–8656. doi: 10.1021/ja010996t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kelley SO, Boon EM, Barton JK, Jackson NM, Hill MG. Nucl. Acids Res. 1999;27:4830–4837. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.24.4830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Boon EM, Ceres DM, Drummond TG, Hill MG, Barton JK. Nature biotechnology. 2000;18:1096–1100. doi: 10.1038/80301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Boal AK, Barton JK. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:312–321. doi: 10.1021/bc0497362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pascaly M, Yoo J, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:9083–9092. doi: 10.1021/ja0202210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Augustyn KE, Genereux JC, Barton JK. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007;46:5731–5733. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Clark CD, Hoffman MZ. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1997;159:359–373. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dohno C, Stemp EDA, Barton JK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:9586–9587. doi: 10.1021/ja036397z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gray HB, Winkler JR, Wiedenfeld D. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2000;200–202:875–886. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.