Abstract

Hair cells in the auditory, vestibular, and lateral-line systems of vertebrates receive inputs through a remarkable variety of accessory structures that impose complex mechanical loads on the mechanoreceptive hair bundles. Although the physiological and morphological properties of the hair bundles in each organ are specialized for detecting the relevant inputs, we propose that the mechanical load on the bundles also adjusts their responsiveness to external signals. We use a parsimonious description of active hair-bundle motility to show how the mechanical environment can regulate a bundle’s innate behavior and response to input. We find that an unloaded hair bundle can behave very differently from one subjected to a mechanical load. Depending on how it is loaded, a hair bundle can function as a switch, active oscillator, quiescent resonator, or low-pass filter. Moreover, a bundle displays a sharply tuned, nonlinear, and sensitive response for some loading conditions and an untuned or weakly tuned, linear, and insensitive response under other circumstances. Our simple characterization of active hair-bundle motility explains qualitatively most of the observed features of bundle motion from different organs and organisms. The predictions stemming from this description provide insight into the operation of hair bundles in a variety of contexts.

Keywords: auditory system, hair cell, Hopf bifurcation, transduction, vestibular system

As the mechanosensitive organelle of a hair cell, the hair bundle detects acceleration in the vestibular system, sound in the auditory system, and fluid flow in the lateral-line system. Stimulation of any of these organs results in hair-bundle deflection and the consequent generation of an electrical signal by the hair cell (1). The hair bundle is more than a passive detector, however, for it can mechanically amplify an external input (2). Moreover, an active hair bundle can be tuned to specific frequencies, can oscillate spontaneously, and can exhibit a nonlinear response to external forcing. In contrast, a passive bundle is untuned, quiescent, and linear (2–6).

The mechanical load imposed upon a hair bundle, which varies greatly depending on the receptor organ, might be expected to adjust the bundle’s performance. In the mammalian cochlea, the hair bundles of outer hair cells are sensitive to the displacement of the overlying tectorial membrane to which they are attached. In contrast, the hair bundles of inner hair cells in the same organ are free of accessory structures but are deflected by fluid flow. Linear acceleration is detected in the utricle and saccule by hair bundles loaded with calcareous aggregates, the otoconia, embedded in an otolithic membrane. These hair bundles are deflected by the inertial force owing to the mass of the otoconia. The semicircular canals, the sensory organs for angular acceleration, contain groups of hair bundles encased in a gelatinous cupula. Head rotation induces within the canals a fluid flow that the bundles detect. The organization of hair bundles in lateral-line neuromasts from fish and amphibians resembles that of the semicircular canals. These organs can detect oscillatory and sustained fluid flows as well as pressure gradients.

It has been proposed that the activity and nonlinearity of the hair bundle confer exquisite sensitivity, sharp frequency tuning, and broad dynamic responsiveness upon auditory organs (7). Unloaded bundles, whose attachments to accessory structures have been broken, are observed to be insufficiently sensitive, tuned, and nonlinear to account for the properties of the auditory system in vivo. It is not clear, though, how these bundles function when mechanically loaded by accessory structures. Motivated by the variety of mechanical environments in which hair cells occur, we have used a simplified model of active hair-bundle motility to examine the effects of mechanical loading on the behavior of hair bundles.

Results

A Simple Active Hair Bundle.

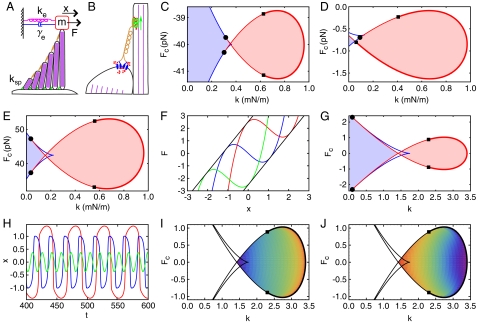

The apical end of each hair cell bears a mechanosensitive hair bundle that comprises an erect cluster of actin-packed, cylindrical processes known as stereocilia that pivot at their bases (Fig. 1A). Each stereocilium is attached to its shortest neighbor by a proteinaceous tip link at whose lower end lie two mechanoelectrical-transduction channels (8). In response to the change in tip-link tension resulting from hair-bundle deflection, these channels open to admit a cation current (1) (Fig. 1B). The gating of these channels confers nonlinear stiffness upon the bundle (9).

Fig. 1.

Characteristics of hair bundles. (A) A hair bundle loaded by an external stiffness ke, a damping γe, and a mass m is stimulated by an external force F. The rigidity of each stereocilium in the hair bundle is determined by its cytoskeletal network of parallel actin filaments (purple). Stereocilia are interconnected by tip links (orange) and pivot elastically about their bases with a total pivotal stiffness ksp. (B) Two adjacent stereocilia are connected by a tip link (orange) that is thought to be attached at its base to two mechanoelectrical-transduction channels (blue). An adaptation process controls the gating of the channels and thus affects both the current into and displacement of the hair bundle. This process may correspond to the dynamics of the channels, the intracellular Ca2+ concentration (red), or the activity of myosin motors (green). (C)–(E) State diagrams show that the behavior of the loaded hair bundle depends upon the constant offset force F = Fc and the stiffness k = ksp + ke. The loops of Hopf bifurcations (red) and the lines of saddle-node bifurcations (blue) determine the main types of hair-bundle behavior: a bundle may be monostable (white regions), bistable (light blue regions), or spontaneously oscillating (light red regions). The amplitude of spontaneous oscillations is zero along the supercritical part (thick) and nonzero along the subcritical part (thin) of the Hopf loop; the transitions between these regimes occur at the Bautin bifurcation points (black squares). The Hopf bifurcation loop ends at the Bogdanov–Takens points (black circles). Similar state diagrams arise from three different models of adaptation dynamics based on (C) the state of the transduction channels, (D) the intracellular Ca2+ concentration, and (E) the position of the myosin motors. (F)–(J) Results for the simple hair bundle (Eq. 1) with rescaled units. (F) The instantaneous displacement-force relation of the hair bundle, F = kx - a(x - f) + (x - f)3, moves upwards along lines of slope k = 2 (black) as the adaptation force f increases; f = -1 (green), f = 0 (blue) and f = 1 (red). When k < a there is a region of negative stiffness of width  . (G) The state diagram for the simple hair bundle includes a loop of Hopf bifurcations (red, Eq. S10) and lines of saddle-node bifurcations (blue, Eq. S9). (H) Spontaneous hair-bundle oscillations of various forms emerge for different stiffnesses: k = 1.8 (red); k = 2.5 (blue); k = 3.3 (green). (I) The amplitudes of spontaneous oscillations, which are encoded by a color spectrum within the fish’s head, range from zero (red) to 1.77 (violet). (J) The frequencies of spontaneous oscillations range from 0.06 (red) to 0.41 (violet). Unless specified otherwise, all panels in all figures correspond to a = 3.5, b = 0.5, τ = 10, γe = 0, m = 0, and Fc = 0.

. (G) The state diagram for the simple hair bundle includes a loop of Hopf bifurcations (red, Eq. S10) and lines of saddle-node bifurcations (blue, Eq. S9). (H) Spontaneous hair-bundle oscillations of various forms emerge for different stiffnesses: k = 1.8 (red); k = 2.5 (blue); k = 3.3 (green). (I) The amplitudes of spontaneous oscillations, which are encoded by a color spectrum within the fish’s head, range from zero (red) to 1.77 (violet). (J) The frequencies of spontaneous oscillations range from 0.06 (red) to 0.41 (violet). Unless specified otherwise, all panels in all figures correspond to a = 3.5, b = 0.5, τ = 10, γe = 0, m = 0, and Fc = 0.

Hair bundles exhibit adaptation whereby the mechanically sensitive channels reclose owing to the influx of Ca2+ through the channels, suggesting that Ca2+ regulates a cytoplasmic adaptation element (1) (Fig. 1B). Three alternative models have been proposed to explain adaptation. The degree of adaptation might be defined by the state of the channel, which may be open or closed and may have Ca2+ bound to one or more sites (10). Adaptation might alternatively correspond to the dynamics of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration itself (11). Finally, adaptation might reflect the position of myosin motors that actively adjust the tension in the tip links (5, 12).

An accessory structure loads a hair bundle with stiffness, damping, mass, and constant force. In the absence of mass and external damping, the behavior of the bundle is described by the state diagrams for the three alternative models of adaption (Figs. 1 C–E and SI Appendix). The hair bundle is either monostable, bistable, or spontaneously oscillating depending upon the mechanical operating point of the system, defined by the constant force Fc and the total linear stiffness k (Fig. 1A). Each state diagram resembles a fish: the head region contains mechanical operating points at which the hair bundle oscillates spontaneously whereas the tail corresponds to switch or bistable behavior. The heads are demarcated by a loop of Hopf bifurcations and the tails by lines of saddle-node bifurcations. The Hopf bifurcation loops end at the intersection with the saddle-node bifurcations at points known as Bogdanov–Takens bifurcations and change from supercritical to subcritical at the Bautin points (13). Although each diagram corresponds to a different adaptation mechanism described by distinct dynamical equations, the diagrams are all qualitatively alike: independent of the details of the adaptation mechanisms, all three models describe hair bundles with similar behavior when loaded by a stiffness and an offset force.

We propose the following simplified description of the mechanics of a loaded active hair bundle:

|

[1] |

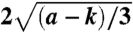

in which x is the hair bundle’s displacement, f is the force applied to the bundle by the adaptation system, g(x, f) = a(x - f) - (x - f)3 is the gating force associated with the transduction channels, τ is the relaxation time of the adaptation force, a is a stiffness, and b is a stiffness coupling adaptation to hair-bundle displacement. The external load on the hair bundle stems from the stiffness ke, damping γe, mass m, and constant offset force F = Fc (Fig. 1A). The total linear stiffness of the system is k = ke + ksp, in which ksp is the stiffness of the bundle’s stereociliary pivots. The total damping of the system is γ = 1 + γe, in which the reference damping of the hair bundle is rescaled to unity. The parameters ke, γe, m, and Fc may also be viewed as contributions to the intrinsic stiffness, damping, mass, and offset force of an unloaded hair bundle. The number of independent parameters in these equations has been minimized by rescaling (SI Appendix).

This formulation is based on four key experimental observations. First, the hair bundle’s instantaneous displacement-force relation is nonlinear owing to the gating force g(x, f) (6, 9, 14) (Fig. 1F). Next, the instantaneous displacement-force relation moves along a line of finite slope as adaptation proceeds (15) (Fig. 1F), which occurs if g(x, f) is a function of the difference x - f. Third, adaptation is a function of bundle displacement, which controls the intracellular Ca2+ concentration upon which adaptation depends (1). And finally, adaptation relaxes on a particular timescale τ (16).

When m = 0 and γe = 0, the state diagram for this system is qualitatively similar to those for the three more complex models of hair-bundle motility (Fig. 1G). The position of the fish’s tail and the size of its head depend upon the values of the internal parameters a, b, and τ. The system exhibits additional richness in behavior not shown in Fig. 1G (SI Appendix).

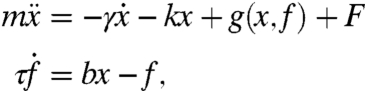

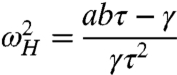

For mechanical operating points inside the fish’s head and close to its tail, the hair bundle displays relaxation oscillations similar to those observed experimentally (Fig. 1H) (2, 3, 5). In qualitative agreement with observations, these spontaneous oscillations decrease in amplitude, increase in frequency, and become more sinusoidal as the stiffness k increases (Fig. 1 H–J) (5). In general, the frequency of oscillation ωH along the line of supercritical Hopf bifurcations is given by

|

[2] |

and is independent of Fc. The Bogdanov–Takens points correspond to the case in which ωH = 0.

Forcing.

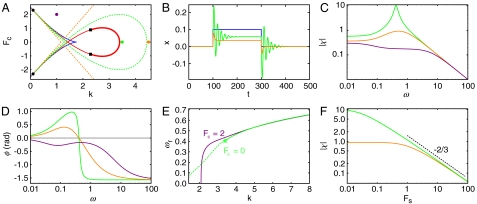

We next examine the effect of loading on the signal-detection ability of a monostable hair bundle. Within a region surrounding the Hopf loop the hair bundle is underdamped and rings in response to step stimulation, whereas beyond this region the bundle is overdamped (Fig. 2 A and B). The hair bundle stimulated by a force step initially moves in the direction of the force and then reverses its direction, an experimentally observed phenomenon known as a twitch (17, 18). In agreement with our description, a twitch occurs in experiments for only a specific range of offset forces Fc (SI Appendix) (17). Unlike a damped harmonic oscillator, the hair bundle can overshoot its steady-state position in the overdamped region owing to the dynamics of the adaptation variable (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, in agreement with observations on mammalian hair bundles (6), the model shows that a quiescent hair bundle stimulated with a force step can actively displace an attached fiber (SI Appendix).

Fig. 2.

The hair bundle’s response to forcing. (A) An underdamped region surrounds the fish (green dashed line). This region is contained within a larger region within which the hair bundle exhibits a resonant response to small sinusoidal forces (orange dashed lines). In (B)–(D) and (F) the colors correspond to the mechanical operating points shown in (A): green, k = 3.5; orange, k = 4.5; purple, k = 1 and Fc = 2. (B) An external force pulse (blue) evokes a ringing response in the underdamped region (green) but not in the overdamped region (orange). (C) The magnitude of the sensitivity χ for weak forcing is shown as a function of the stimulus frequency. The sensitivity displays a peak for mechanical operating points inside the resonant region (green, orange) that contrasts with its behavior as a low-pass filter outside this region (purple). The peak of the sensitivity is larger and sharper for mechanical operating points near the Hopf bifurcation (green) than for those more distant (orange). (D) The phase of the hair bundle’s response to weak forcing is positive for ω < ωϕ: the bundle leads the stimulus when the mechanical operating points are in the resonant region (green, orange). The phase is negative at all frequencies for mechanical operating points outside this region (purple). At high frequencies the phase converges in all cases to -π/2. (E) The resonant frequency ωr (solid green line) and the frequency of spontaneous oscillations (dashed green line) increase as a function of the stiffness k. The resonant frequency equals the frequency of spontaneous oscillation at the Hopf bifurcation (ωH, green star). There is no resonance for k < 2 within the monostable region when Fc = 2 (purple). (F) The sensitivity |χ| for weak forcing at the resonant frequency declines as a function of the forcing amplitude Fs. The sensitivity has a larger linear regime for the mechanical operating point far from the Hopf bifurcation (orange) than for that near the bifurcation (green). The black dashed line indicates the power-law dependence of the sensitivity on force when the mechanical operating point lies at the Hopf bifurcation.

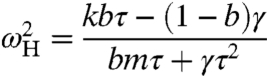

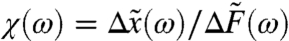

Load has a large effect on the hair bundle’s sensitivity to periodic signals. The effect of an external force F = Fc + Fs cos(ωt) on the hair bundle is defined by the response function χ (Fig. 2 C and D). For a small forcing amplitude Fs,

|

[3] |

Here  , with

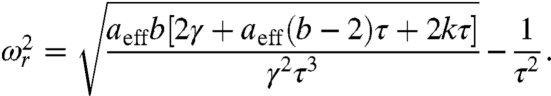

, with  being the Fourier transform of x at the driving frequency ω, and aeff = a - 3(x∗)2(1 - b)2, with x∗ being the value of x for the stable state. Despite the presence of the adaptation process, we recover the sensitivity for a damped harmonic oscillator when aeff = 0. There is a region surrounding the fish within which the monostable hair bundle is resonant (Fig. 2A). Within this region the sensitivity for weak forcing peaks at the resonant frequency ωr (Fig. 2C; Eq. S14). When m = 0 the resonant frequency is given by

being the Fourier transform of x at the driving frequency ω, and aeff = a - 3(x∗)2(1 - b)2, with x∗ being the value of x for the stable state. Despite the presence of the adaptation process, we recover the sensitivity for a damped harmonic oscillator when aeff = 0. There is a region surrounding the fish within which the monostable hair bundle is resonant (Fig. 2A). Within this region the sensitivity for weak forcing peaks at the resonant frequency ωr (Fig. 2C; Eq. S14). When m = 0 the resonant frequency is given by

|

[4] |

This resonant frequency increases with k and equals the Hopf frequency ωH for mechanical operating points on the supercritical Hopf line (Fig. 2E).

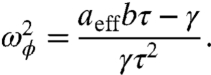

The displacement of a resonant hair bundle exhibits a phase lead with respect to the external force for a range of frequencies ω < ωϕ specified by

|

[5] |

This behavior, which confirms the active nature of a hair bundle, has been observed in oscillating bundles (Fig. 2D) (2). In general, ωϕ ≤ ωr, with the equality holding at the Hopf bifurcation. In contrast, hair bundles outside the resonant region always lag the external force (Fig. 2 A, C, and D).

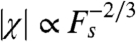

As predicted for hair bundles near a Hopf bifurcation and as observed previously (4, 10, 19, 20), the sensitivity is a nonlinear function of the forcing amplitude and scales as  for a limited range of forcing amplitudes (Fig. 2F). When k increases, however, the range of linear hair-bundle behavior grows as the mechanical operating point recedes from the Hopf bifurcation. Again the behavior of a quiescent active hair bundle differs qualitatively from that of a damped harmonic oscillator. The responsiveness peaks even for mechanical operating points in the overdamped region (Fig. 2

A and C), a phenomenon that cannot occur for a damped harmonic oscillator. Moreover, the step response of a resonant hair bundle can resemble that of a high-pass filter (Fig. 2

B and C).

for a limited range of forcing amplitudes (Fig. 2F). When k increases, however, the range of linear hair-bundle behavior grows as the mechanical operating point recedes from the Hopf bifurcation. Again the behavior of a quiescent active hair bundle differs qualitatively from that of a damped harmonic oscillator. The responsiveness peaks even for mechanical operating points in the overdamped region (Fig. 2

A and C), a phenomenon that cannot occur for a damped harmonic oscillator. Moreover, the step response of a resonant hair bundle can resemble that of a high-pass filter (Fig. 2

B and C).

Damping.

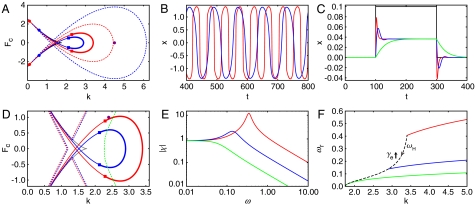

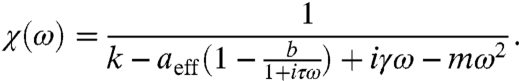

Although viscous damping typically limits the performance of a passive, linear signal detector, its effects on an active, nonlinear system are more complex. The addition of damping decreases the size of the fish’s head but has no effect on its tail (Fig. 3A). Damping also slows spontaneous oscillations (Fig. 3B). Increasing the damping coefficient γe has several additional effects. The underdamped region increases in size such that an overdamped hair bundle can become underdamped (Fig. 3 A and C). This paradoxical behavior, which is not observed for a damped harmonic oscillator, occurs because underdamped behavior requires that the timescale of adaptation τ be comparable to the relaxation time of the hair bundle’s deflection, which is proportional to γ. Very heavy damping eliminates the twitch (Fig. 3C). The resonant region decreases in size and eventually moves towards higher values of k (Fig. 3D). The sensitivity to weak forcing declines, as does the resonant frequency (Fig. 3E, Eq. 4). Finally, the width of the resonance increases (Fig. 3E). A sufficiently large amount of damping can move the resonant region away from the mechanical operating point until the system becomes a low-pass filter (Fig. 3E). The fish’s head disappears when the Hopf loop collides with the cusp at the critical value of γ = τab. At this point the Hopf frequency given by

|

[6] |

equals zero as does the resonant frequency, but the monostable hair bundle can nonetheless resonate for nearby mechanical operating points (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

The effect of damping on the hair bundle. The damping coefficients are γe = 0 (red) and γe = 5 (blue) for all panels. (A) Damping has no effect on the saddle-node tail (black) but reduces the size of the fish’s head (red and blue solid lines), which disappears at a codimension-three bifurcation when γe = 16.5. The equation for the loop of Hopf bifurcations is of the same form as Eq. S10 with τ → τ/γ. Both the Bogdanov–Takens points (circles) and the Bautin points (squares) move as γe changes. The underdamped region increases in size as γe increases (red and blue dashed lines). (B) Damping slows spontaneous hair-bundle oscillations with k = 1.8. (C) For the step response at k = 4.5 [purple circle in (A)], an increase in damping causes an overdamped hair bundle (red) to become underdamped (blue). However, a sufficiently large amount of damping (green, γe = 90) results in motion without any twitch. (D) The boundary of the resonant region (red and blue dashed lines) loses its fishtail structure and moves to higher values of k as damping increases (green dashed line, γe = 30). (E) The magnitude of hair-bundle sensitivity is shown for weak forcing as a function of the driving frequency at the purple circle in (D). Damping reduces the sensitivity and moves the peak to lower frequencies. The hair bundle acts as a low-pass filter when damping moves the resonant region away from the mechanical operating point (green, γe = 30). (F) The resonant frequency for three different values of γe (green, γe = 16.5) increases as a function of k. The Hopf frequency at Fc = 0 (black dashed line) declines as γe increases and equals zero at the point where the shrinking fishhead disappears (green, k = a(1 - b)). The resonant frequency equals the Hopf frequency at the Hopf bifurcation for all values of γe.

Mass.

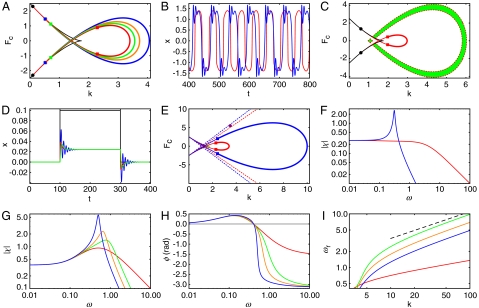

For many operating points, increasing the mass loading of a hair bundle raises its sensitivity. Mass increases the size of the fish’s head and the extent of the supercritical Hopf bifurcations without changing the tail or the positions of the Bogdanov–Takens bifurcations (Fig. 4A). Mass also decreases the frequency of spontaneous hair-bundle oscillations and causes the bundle to ring at the end of each stroke (Fig. 4B). Unlike the response of a damped harmonic oscillator, the ringing exhibits more than one frequency component as it slows with time. The extent of the overdamped region decreases as the mass increases (Fig. 4C) and the entire monostable region is underdamped when m > 1 and γe = 0. The step response displays ringing when mass is included. Ringing can be suppressed by increasing the damping and vanishes in the absence of mass for large values of the stiffness k (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

The effect of mass on the hair bundle. (A) Mass increases the size of the fish’s head but has no effect on the tail: m = 0, red; m = 1, green; m = 2, orange; m = 4, blue. The loop of Hopf bifurcations is given by Eq. S11. The Bogdanov–Takens points (circles) do not change but the Bautin points (squares) move as m grows such that the region of supercritical Hopf bifurcations increases. (B) Spontaneous oscillations are shown for k = 1.8 without mass (red) and with mass m = 4 (blue). The mass slows these relaxation oscillations and causes the hair bundle to ring at the end of each oscillation stroke. (C) When m = 4 and γe = 5 the overdamped region (green) decreases in size as m increases. (D) The step response at k = 5.9 is shown for m = 0 with γe = 0 (red), m = 4 with γe = 0 (blue), and m = 4 with γe = 5 (green). The last mechanical operating point lies in the overdamped region shown in (C). Mass loading causes an overdamped bundle to ring, an effect that can be suppressed by damping. (E) The resonant region increases in size from m = 0 (dashed red lines) to m = 40 (dashed blue lines). (F) A plot of the magnitude of the sensitivity for weak forcing discloses that the nonresonant hair bundle (red) exhibits a resonance upon mass loading (blue, k = 3.5 and Fc = 5.5; purple circle in panel E). The color code in panels G-I indicates the mass and is the same as in (A). (G) The sensitivity and sharpness of tuning rise as the mass increases (k = 4.5). (H) The high-frequency limit of the phase of hair-bundle motion relative to that of the external force changes from -π/2 (red) to -π when the hair bundle is loaded with a mass (k = 4.5). (I) The resonant frequency increases as a function of the stiffness for different values of mass loading. The ordinate axis begins at the Hopf frequency, which is the same for all the curves because it is independent of the mass and stiffness k when Fc is zero (Eq. 6). The black dashed line indicates the dependence of the resonant frequency on the stiffness for a simple harmonic oscillator.

The resonant region grows with an increase in mass such that a nonresonant hair bundle can become resonant (Fig. 4 E and F). At a fixed mechanical operating point, mass can increase a hair bundle’s sensitivity and sharpness of tuning owing to a change in the position of the fish’s head (Fig. 4G).

Independent of the mass, the phase of an active hair bundle leads that of an external force (Fig. 4H) for driving frequencies below ωϕ (Eq. 5). For all nonzero values of the mass, the phase lag converges to -π as the driving frequency approaches infinity. The resonant frequency initially decreases with m and then, like that of a simple harmonic oscillator, increases for large values of k as  (Fig. 4I). At the Hopf bifurcation the resonant frequency equals the Hopf frequency, which is independent of the mass and stiffness k when Fc is zero (Eq. 6).

(Fig. 4I). At the Hopf bifurcation the resonant frequency equals the Hopf frequency, which is independent of the mass and stiffness k when Fc is zero (Eq. 6).

Discussion

Despite the fundamental morphological similarities between hair bundles from different receptor organs in various organisms, there are many physiological differences between the bundles derived from different sources. Twitches have been observed in the vestibular cupulae of fishes and in the hair bundles of amphibians and reptiles including birds, but not in the bundles of the mammalian cochlea (6, 17, 18, 21, 22). Piscine, amphibian, and reptilian hair bundles can oscillate spontaneously, but autonomous oscillation of bundles from mammals has not been observed (3, 5, 23). Vestibular hair bundles exhibit negative stiffness, but those of auditory receptors and lateral-line organs do not despite their nonlinear stiffnesses (6, 14, 15, 24).

Although these differences may result from fundamental dissimilarities in hair-bundle structure across organs and organisms, the variations may simply reflect distinct mechanical operating points of the hair bundles. Whether an unloaded bundle exhibits negative stiffness, produces a twitch, or oscillates spontaneously depends upon its stiffness and force offset. More generally, our simple description demonstrates that, for different mechanical operating points, the hair bundle can function as a resonator, a low-pass filter, an active oscillator, or a bistable switch. In addition, a bundle can respond nonlinearly or linearly to external forces for mechanical operating points respectively close to or far from the fish’s head. These regimes of behavior depend upon the bundle’s intrinsic stiffness, damping, mass, and force offset.

A key prediction of the work presented here is that a hair bundle can behave very differently when loaded than when unloaded. Thus a hair bundle of the frog’s sacculus, which oscillates spontaneously at low frequencies when unloaded, may be quiescent and resonate at higher frequencies when attached to the stiff otolithic membrane (25). A quiescent hair bundle from the mammalian cochlea or vestibular system may similarly display increased sensitivity, become resonant, and even start oscillating when confronted by the mass of the tectorial or otolithic membrane. Finally, the sensitivity of a hair bundle may be controlled by embedding it in a viscous cupula, as may be the case for the bundles of semicircular canals and lateral-line neuromasts.

Passive hair bundles are typically overdamped and do not resonate, whereas active hair bundles can be tuned (4). Although the load of a spring and a mass influences the resonance of an active bundle, the resonant frequency is not necessarily equal to that of the load. The idea also accords with a description of mammalian cochlear mechanics showing that resonance in the cochlea depends upon active processes (26).

Unlike a damped harmonic oscillator, an active hair bundle can overshoot without ringing, resonate when overdamped, and display a phase lead with respect to the stimulus. The bundle can change from being obviously active and nonlinear when it is oscillating spontaneously to appearing passive and linear when its passive properties dominate its activity. Indeed, a hair bundle functions as a damped harmonic oscillator when the load stiffness is very large.

Although there is uncertainty about the exact nature of the adaptation process in a hair bundle, the qualitative behavior of the bundle’s displacement and its response to mechanical stimulation are independent of the detailed adaptation mechanism. Different models for adaptation thus yield similar results and may be difficult to distinguish solely on the basis of a bundle’s mechanical response. Even the simple model presented here exhibits very complex behavior in the region where the head and tail of the fish overlap (SI Appendix). Additional complexities arise from the effects of noise and the interplay between multiple adaptation mechanisms (11, 20, 27).

Our results indicate that a hair bundle can serve diverse roles in the various mechanical environments imposed by different organs. Owing to its simplicity and the parsimonious assumptions underlying it, the description presented here provides a framework for understanding active hair-bundle motility and the effects of loading. In addition to unifying observations from different organisms and organs, the analysis provides several testable predictions of how the behavior of hair bundles and their performance as signal detectors can be controlled.

Materials and Methods

Calculations were performed using Mathematica 7 and AUTO with XPPAUT 6.00. Further details are given in the SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank the members of the Laboratory for Sensory Neuroscience for constructive comments on the manuscript. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DC000241 and by the Spanish Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación and European Regional Development Fund under Grant FIS2007-60327 (FISICOS). D.Ó M. is a Research Associate and A.J.H. an Investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1120298109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hudspeth AJ. How the ear’s works work. Nature. 1989;341:397–404. doi: 10.1038/341397a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin P, Hudspeth AJ. Active hair-bundle movements can amplify a hair cell’s response to oscillatory mechanical stimuli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14306–14311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. The mechanical properties of ciliary bundles of the turtle cochlear hair cells. J Physiol. 1985;364:359–379. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin P, Hudspeth AJ. Compressive nonlinearity in the hair bundle’s active response to mechanical stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:14386–14391. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251530498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin P, Bozovic D, Choe Y, Hudspeth AJ. Spontaneous oscillations by the hair bundles of the bullfrog’s sacculus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4533–4548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04533.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kennedy HJ, Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. Force generation by the mammalian hair bundle supports a role in cochlear amplification. Nature. 2005;433:880–883. doi: 10.1038/nature03367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hudspeth AJ. Making an effort to listen: Mechanical amplification in the ear. Neuron. 2008;59:530–545. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beurg M, Fettiplace R, Nam J-H, Ricci AJ. Localization of inner hair cell mechanotransducer channels using high speed calcium imaging. Nature Neurosci. 2009;12:553–558. doi: 10.1038/nn.2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howard J, Hudspeth AJ. Compliance of the hair bundle associated with gating of mechanoelectrical transduction channels in the bullfrog’s saccular hair cell. Neuron. 1988;1:189–199. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(88)90139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choe Y, Magnasco MO, Hudspeth AJ. A model for amplification of hair-bundle motion by cyclical binding of Ca2+ to mechanoelectrical-transduction channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:15321–15326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vilfan A, Duke T. Two adaptation processes in auditory hair cells together can provide and active amplifier. Biophys J. 2003;85:191–203. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74465-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tinevez J, Jülicher F, Martin P. Unifying the various incarnations of active hair-bundle motility by the vertebrate hair cell. Biophys J. 2007;93:4053–4067. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.108498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuznetsov YA. Elements of Applied Bifurcation Theory. 2nd edition. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ricci AJ, Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. Mechanisms of active hair bundle motion in auditory hair cells. J Neurosci. 2002;22:44–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00044.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martin P, Mehta AD, Hudspeth AJ. Negative hair bundle stiffness betrays a mechanism for mechanical amplification by the hair cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:12026–12031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.210389497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le Goff L, Bozovic D, Hudspeth AJ. Adaptive shift in the domain of negative stiffness during spontaneous oscillation by hair bundles from the internal ear. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:16996–17001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508731102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benser ME, Hudspeth AJ. Rapid, active hair bundle movements in the hair cells from the bullfrog’s sacculus. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5629–5643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-18-05629.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ricci AJ, Crawford AC, Fettiplace R. Active hair bundle motion linked to fast transducer adaptation in auditory hair cells. J Neurosci. 2000;20:7131–7142. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-19-07131.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eguíluz VM, Ospeck M, Choe Y, Hudspeth AJ, Magnasco MO. Essential nonlinearities in hearing. Phys Rev Lett. 2000;84:5232–5235. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.5232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camalet S, Duke T, Jülicher F, Prost J. Auditory sensitivity provided by self-tuned critical oscillations of hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3183–3188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabbitt RD, Boylec R, Highstein SM. Mechanical amplification by hair cells in the semicircular canals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3864–3869. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906765107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudspeth AJ, Choe Y, Mehta AD, Martin P. Putting ion channels to work: Mechanoelectrical transduction, adaptation, and amplification by hair cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11765–11772. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rüsch A, Thurm U. Spontaneous and electrically induced movements of ampullary kinocilia and sterovilli. Hear Res. 1990;48:247–263. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90065-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Netten SM, Khanna SM. Stiffness changes of the cupula associated with the mechanics of hair cells in the fish lateral line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1549–1553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.4.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strimbu CE, Kao A, Tokuda J, Ramunno-Johnson D, Bozovic D. Dynamic state and evoked motility in coupled hair bundles of the bullfrog sacculus. Hear Res. 2010;265:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ó Maoiléidigh D, Jülicher F. The interplay between active hair bundle motility and electromotility in the cochlea. J Acoust Soc Am. 2010;128:1175–1190. doi: 10.1121/1.3463804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roongthumskul Y, Fredrickson-Hemsing L, Kao A, Bozovic D. Multiple-timescale dynamics underlying spontaneous oscillations of saccular hair bundles. Biophys J. 2011;101:603–610. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2011.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.