Abstract

Aims

Renin-angiotensin system antagonists have been found to improve glucose metabolism in obese hypertensive and type 2 diabetic subjects. The mechanism of these effects is not well understood. We hypothesized that the angiotensin receptor antagonist losartan would improve insulin-mediated vasodilation, and thereby improve insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle of insulin resistant subjects.

Materials and Methods

We studied subjects with obesity and insulin resistance but without hypertension, hypercholesterolemia or dysglycemia (age 39.0±9.6 yrs [mean±SD], BMI 33.2±5.9 kg/m2, BP 115.8±12.2/70.9±7.2 mmHg, LDL 2.1±0.5 mmol/L). Subjects were randomized to 12 weeks’ double-blind treatment with losartan 100 mg once daily (n=9) or matching placebo (n=8). Before and after treatment, under hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp conditions we measured whole-body insulin stimulated glucose disposal, insulin-mediated vasodilation, and insulin-stimulated leg glucose uptake by the limb balance technique.

Results

Whole-body insulin-stimulated glucose disposal was not significantly increased by losartan. Insulin-mediated vasodilation was augmented following both treatments (increase in leg vascular conductance: pre-treatment 0.7±0.3 L*min−1*mmHg−1[losartan, mean ±SEM] and 0.9±0.3 [placebo], post-treatment 1.0±0.4 [losartan] and 1.3±0.6 [placebo]) but not different between treatment groups (p=0.53). Insulin’s action to augment NO production and to augment endothelium-dependent vasodilation were also not improved. Leg glucose uptake was not significantly changed by treatments, and not different between groups (p=0.11).

Conclusions

These findings argue against the hypothesis that losartan might improve skeletal muscle glucose metabolism by improving insulin-mediated vasodilation in normotensive insulin resistant obese subjects. The metabolic benefits of angiotensin receptor blockers may require the presence of hypertension in addition to obesity-associated insulin resistance.

Introduction

Improvements in insulin resistance and reductions in the incidence of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus have been observed in clinical trials of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and type 1 angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB) (1–3). Many physiological studies using these classes of agents have demonstrated improvements in insulin-stimulated whole body glucose disposal (3–14) but this is not seen in all cases (15–18).

It is now well recognized that insulin acts in skeletal muscle in part via endothelium-dependent, regulated vasodilator actions to redistribute blood flow (3, 19–21). This effect contributes ~25% of insulin’s net actions on glucose uptake in skeletal muscle (22), and impairment in these responses contributes to net metabolic insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus. ACEI and ARB class medications improve endothelial dysfunction and nitric oxide production in hypertension (8, 23–25) and in insulin resistant states (26, 27). In this light, it is possible that beneficial effects of ACEI or ARB class medications on the endothelium could improve insulin’s endothelium-dependent actions (17, 28). We therefore hypothesized that the type 1 angiotensin receptor antagonist losartan would improve insulin-mediated vasodilation, and thereby improve insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in skeletal muscle, in insulin resistant obese subjects without hypertension.

Methods

Nondiabetic obese subjects were recruited through newspaper advertisement, and classified as obese using body mass index cutpoints of ≥26 kg/m2 for men or ≥28 for women to select for equivalent degrees of obesity across sexes (29). Exclusion criteria included hypertension (SBP>140/DBP>90) or antihypertensive therapy, elevated serum lipids (total cholesterol >5.2 mmol/L, LDL >2.3 mmol/L or TG >2.0 mmol/L), biochemical evidence of renal or hepatic dysfunction, or significant underlying medical conditions. Age below 20 or above 55 years was an exclusion criterion, as were pregnancy and known hypersensitivity to losartan. All subjects underwent a standard 75g oral glucose tolerance test to screen for diabetes mellitus, and had body composition assessed by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) measurement. When originally designed, obesity plus dysglycemia were required enrollment criteria; after the first 6 months of recruitment these criteria were modified to allow normoglycemia but require elevated fasting insulin concentrations (>10.0 mU/mL) in order to focus enrollment of insulin resistant subjects. This study was approved by the local Institutional Review Board, and all subjects gave written informed consent. All procedures were performed in accordance with institutional guidelines. This study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT00402194.

Design

Following screening and enrollment, subjects underwent baseline measurements of insulin’s systemic and vascular actions as detailed below. Randomized treatment assignment was done by a third party not involved in study measurements, using a randomly generated assignment sequence. Treatment assignments were masked to the investigator and the participants. Subjects were treated with 50 mg losartan once daily (or matched placebo) for the initial two weeks to document tolerability and a lack of significant change in serum potassium, then increased to 100 mg once daily (or matched placebo) for the remainder of the randomized treatment period. Subjects who failed to complete the study were replaced, with the next enrolled subject assigned to the same treatment as the lost participant in an attempt to maintain balance in treatment assignment. The decision to compare losartan to placebo rather than comparing losartan to a non-RAAS antihypertensive agent was based on an expectation of modest blood pressure effects in this normotensive population, plus a planned correction of endpoints for any changes in blood pressure that did occur (explained in detail below).

Subjects underwent end-of-study measurements following 12±1 weeks of treatment. Subjects did not take their study medication on the morning of the study in order to ensure that any measured changes represented effects of chronic exposure and not the immediately preceding dose. Women with a regular menstrual cycle were studied within the first 11 days of their cycle on both occasions, to minimize the confounding effects of changes in sex steroids on vascular function. Medication compliance was assessed by pill counting.

Procedures and Measurements

Whole leg vascular responses were measured using thermodilution, a highly sensitive technique that has been extensively used to demonstrate vascular effects of insulin (22, 30–32). Before and after treatment, subjects underwent measurements of leg vascular function under basal and insulin-stimulated conditions, to measure insulin’s effect to stimulate glucose uptake for the whole body and the leg. Measurements were made under fasting conditions following an overnight fast.

A 6F sheath (Cordis Corp, Miami, FL) was placed into the right femoral vein to allow the insertion of a custom-designed 5F double-lumen thermodilution catheter (Baxter Scientific, Edwards Division, Irvine, CA) to measure leg blood flow (LBF). The right femoral artery was cannulated with a 5.5F double-lumen catheter to allow simultaneous infusion of vasoactive agents and invasive blood pressure monitoring (Spacelabs, Redmond, WA). All hemodynamic measurements were obtained with the subjects in the supine position in a quiet temperature-controlled room. Basal measurements were obtained ≥30 minutes after the insertion of the catheters. Femoral vein thermodilution was used to measure rates of LBF, calculated by integration of the area under the curve, using a cardiac output computer (model 9520A, American Edwards Laboratories). Reported values are the mean of at least 10 measurements taken at each study stage. Invasively determined MAP was recorded with every other LBF determination.

Endothelium-dependent vasodilation was measured using the cholinergic agonist methacholine chloride, and endothelium-independent vasodilation was measured using sodium nitroprusside, both infused directly into the femoral artery in three sequential doses. Following baseline measurements of vasodilator responses, a hyperinsulinemic euglycemic glucose clamps were performed using an insulin infusion rate of 120 mU*m−2*min−1. Insulin was administered systemically via an antecubital vein. This insulin dose was used in view of the anticipated insulin resistance in the vasculature, in order to ensure a measureable response. Blood samples from the femoral artery were measured every 5 minutes to ensure maintenance of euglycemia. Once steady state of the insulin infusion was achieved (minimum of 180 minutes from initiation of the procedure) repeat vascular measurements were performed. At the end of each study, L-NMMA (Clinalfa, Basel, Switzerland), a competitive antagonist of L-arginine, was infused at 16 mg/min into the femoral artery to block NO generation by nitric oxide synthase. This is the standard infusion rate used in our laboratory (33), chosen on the basis that it provides near-maximal effect across all populations.

The primary endpoint for this study was insulin-mediated vasodilation, measured at baseline and following 12 weeks of therapy. Because of anticipated changes in blood pressure with the angiotensin receptor blocker, we pre-specified leg vascular conductance (leg blood flow divided by concurrent intra-arterial mean arterial pressure) as the main variable of interest for assessing insulin-mediated vasodilation. Secondary endpoints included insulin’s effect to augment methacholine-stimulated vasodilation; vascular responses to nitric oxide synthase inhibition with L-NMMA; skeletal muscle insulin sensitivity for glucose uptake (leg glucose uptake = leg blood flow multiplied by arterio-venous glucose difference at steady state of the insulin infusion); and whole body insulin sensitivity. Nonlinear modeling of the complete clamp datasets was applied to extract steady state rates of whole body glucose disposal and A-V glucose differences (34).

Blood for serum glucose determinations was put in untreated polypropylene tubes, and centrifuged. The glucose concentration of the supernatant was then measured by the glucose oxidase method (Model 2300 Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH). Blood for determination of plasma insulin was frozen at −20°C. Insulin determinations were made using a dual-site radioimmunoassay (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Free (nonesterified) fatty acid measurements were performed using a colorimetric assay. Standard methodologies for cholesterol and triglyceride determinations were performed through our local hospital’s clinical laboratory.

Power Calculations

Our main endpoint of interest was insulin-mediated vasodilation. We therefore made sample size calculations using this parameter, and estimated demonstrable effects for secondary parameters of interest using the sample size obtained in this way. We reasoned that a correction of the impaired effect of insulin in the skeletal muscle vasculature would convert the response observed in obese subjects into that typically observed in lean subjects. Based on related prior studies, this was estimated as a difference in insulin-stimulated vasodilation (IMV) of 0.11 L* min−1 (leg blood flow) or 1.2 ×10−4 L*min−1*mmHg−1 (leg vascular conductance) between the two treatment groups. Effects of this size had been observed with studies using endothelin antagonists in our laboratory (31, 35). We estimated a priori that 9 subjects per group would provide 80% power to detect this effect size, recognizing that likelihood of detecting smaller effect sizes is accordingly reduced. This number of subjects was then used to estimate detectable differences (with 80% power) in insulin-stimulated whole body glucose uptake of 2.7 mg*kg−1*min−1 (~35% increase), and differences in insulin-stimulated leg glucose uptake of 41 mg/min (~50% increase). Again, these effect sizes are within the range demonstrated in our laboratory previously (31). With paired studies in our population we have historically seen a 15% noncompletion rate and to allow for this we planned to recruit 11 subjects per group.

Statistics

Chi square or one-way ANOVA were applied for group comparisons at a single time point. Linear mixed modeling was applied to assess repeated measures treatment effects, in order to use all available data. Standard covariance matrices were applied, and data were not transformed.

Results

We screened 32 consecutive volunteer subjects for participation in this protocol. Of these, 22 met inclusion/exclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study. Due to dropouts, we completed the project with 9 subjects in the losartan group and 8 in the placebo group. No losartan-treated subjects withdrew, and no subjects reported medication-related side effects as a reason for withdrawal from the study.

The characteristics of the study population are described in Table 1. Despite randomization, there was a modest difference in the body mass index (BMI) between treatment groups (with a greater mean BMI in the losartan-treated subjects), although the waist circumferences did not differ. This population was normoglycemic but hyperinsulinemic with correspondingly elevated HOMA-IR scores. Baseline cuff blood pressure and lipid parameters were not statistically different between groups, and as designed these parameters were well below current treatment thresholds. Subjects who withdrew from the study were not statistically different from those who completed the study in any of these parameters (not shown). By pill counting, compliance was greater than 95% for both treatment groups. Serum potassium was unaffected by study drug treatment, and no subjects had treatment dose modified or were excluded from the study on this basis.

Table 1.

Subject Characteristics

| Parameter | Placebo | Losartan | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race (C/AA) | 4/4 | 5/4 | 0.86 |

| Sex (M/F) | 3/5 | 4/5 | 0.38 |

| Age (yrs) | 36.5±10.1 | 41.0±8.7 | 0.34 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.3±2.9 | 36.4±6.6 | 0.03 |

| Waist (cm) | 91.0±26.1 | 95.2±11.1 | 0.91 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 121±10 | 122±10 | 0.60 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 75±7 | 78±8 | 0.16 |

| Glucose Fasting (mmol/L) | 5.2±0.5 | 5.2±0.4 | 0.77 |

| Glucose OGTT 120min (mmol/L) | 7.1±1.3 | 7.1±2.5 | 0.99 |

| Non-esterified fatty acids Fasting (mmol/L) | 0.40±0.18 | 0.46±0.26 | 0.50 |

| Insulin Fasting (mU/mL) | 17.2±14.3 | 20.4±10.2 | 0.48 |

| HOMA-IR (U) | 3.4±2.4 | 4.4±1.7 | 0.35 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.23±0.73 | 1.18±0.69 | 0.91 |

| Total Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.37±0.64 | 3.69±0.55 | 0.28 |

| LDL Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 2.00±0.46 | 2.29±0.42 | 0.19 |

| HDL Cholesterol (mmol/L) | 0.92±0.29 | 0.96±0.27 | 0.79 |

| Baseline LBF (L/min) | 0.26±0.05 | 0.24±0.05 | 0.53 |

| Baseline GDR120 (mg/kg/min) | 6.8±2.0 | 5.9±2.2 | 0.33 |

Values are presented as mean±sd. P values are presented for comparison of placebo versus losartan by one-way ANOVA.

Vascular outcomes

Cuff blood pressure measurements were not statistically changed by randomized treatments (not shown). Modest reductions in intra-arterial blood pressure were seen (Figure 1), not achieving significance in this normotensive population.

Figure 1.

Effects of Losartan on Intra-Arterial Blood Pressure. Upper panel, systolic blood pressure. Lower panel, diastolic blood pressure. Treatment groups were not statistically different at baseline. The principal comparison of interest is treatment effect across groups, designated ‘Treatment effect’ and reflecting the statistical interaction term of treatment*time.

The main study question was whether losartan treatment would augment insulin-mediated vasodilation. Prior to receiving treatment, insulin-induced increases in leg vascular conductance for the combined study population were : baseline 2.74±0.15 ×10−4 L*min−1*mmHg−1 (mean ±SEM) to insulin 3.61±0.23 in the placebo group and baseline 2.40±0.17 to insulin 3.07±0.31 in the losartan group (p <0.001 for insulin effect; p=0.31 comparing pre-treatment data across groups; Figure 2 upper panel). By comparison, unpublished and previously published data from our laboratory show that this insulin exposure caused a larger increase in leg vascular conductance from 2.33±0.37 to 4.81±1.91 in lean subjects (N=14; p=0.03 comparing to this baseline effect in our population). Therefore this pre-treatment effect reflects impaired insulin-mediated vasodilation at baseline, as expected for this obese insulin resistant population.

Figure 2.

Effects of Losartan on Insulin-Stimulated Vascular Response. Upper panel, vascular actions of insulin; middle panel, augmentation of leg vascular conductance at steady state; lower panel, reduction in leg vascular conductance following treatment with L-NMMA at steady state. The principal comparison of interest is treatment effect across groups, designated ‘Treatment effect’ and reflecting the statistical interaction term of treatment*time.

Following 3 months’ treatment, there was no evident change in basal unstimulated leg vascular conductance in either group, and the effect of insulin was essentially unchanged from prior to treatment (placebo: basal LVC 2.34±0.31 ×10−4 to insulin 3.68±0.57; losartan: basal 2.67±0.30 to insulin 3.59±1.89; p=0.51 for insulin*treatment interaction; Figure 2 middle panel).

A complementary measure of effects of treatment on insulin’s vascular effects is provided by the effect of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor L-NMMA to decrease leg vascular conductance In these studies this was only measured at steady state of the insulin infusion, and therefore reflects insulin-stimulated nitric oxide bioavailability. The pre-treatment decrements in LVC with L-NMMA were not statistically different between treatment groups (Figure 2 bottom panel). Losartan did not improve insulin-stimulated NO bioavailability (i.e. no increase in magnitude of L-NMMA – induced decrement in LVC following treatment).

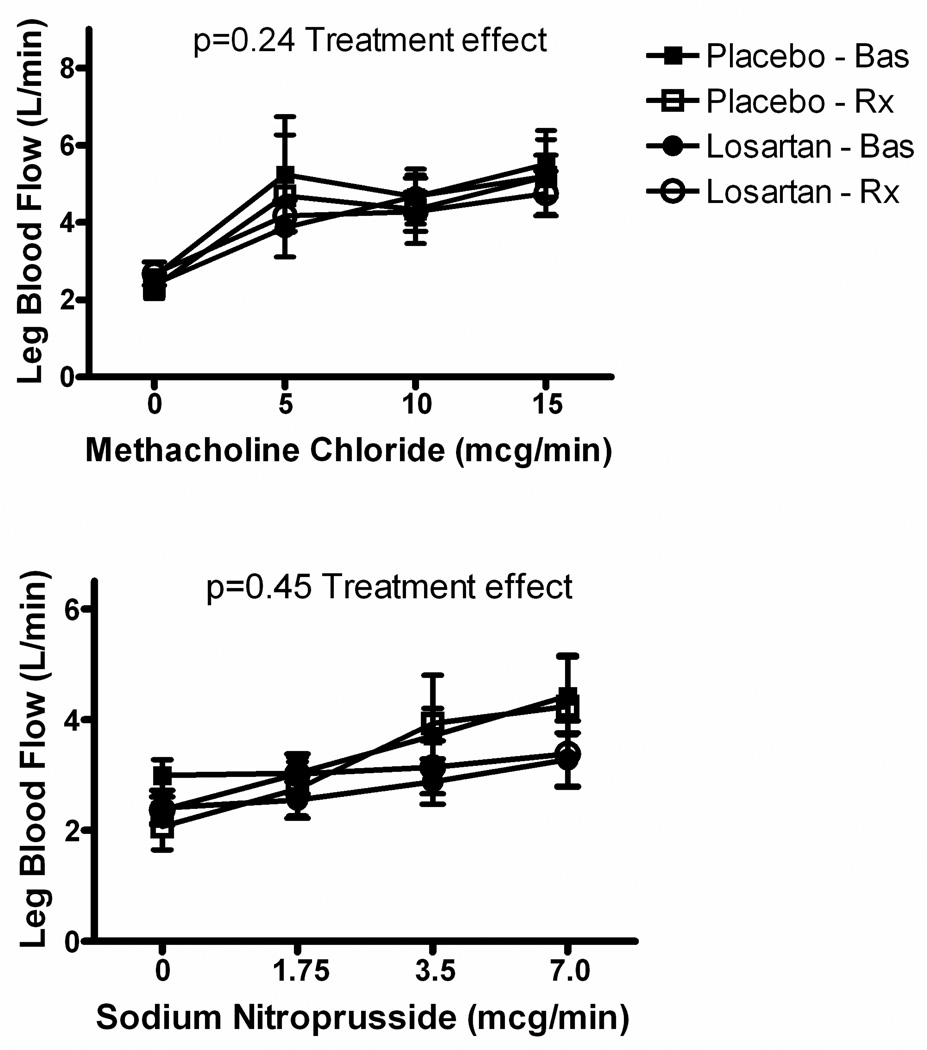

Endothelium-dependent vasodilation

We measured endothelium-dependent vasodilation in two ways. First, the direct effects of the endothelium-dependent vasodilator methacholine were evaluated. Second, we measured the effect of insulin to augment methacholine-stimulated vasodilation, an effect that can be additive and depends on insulin’s action as an endothelium-dependent vasodilator (36).

Methacholine-stimulated increases in leg blood flow were not statistically different between pre- and post-treatment measurements, nor between treatment groups (Figure 3 upper panel). Endothelium-independent vasodilation, assessed as nitroprusside-stimulated vasodilation, was also not affected by losartan treatment (Figure 3 lower panel).

Figure 3.

Effects of Losartan on Vascular Function. Upper panel, endothelium-dependent vasodilation; lower panel, endothelium-independent vasodilation. Methacholine-induced vasodilation did not differ at baseline between treatment groups, and was not changed in either group following treatment. Nitroprusside-induced vasodilation was reduced in the Losartan-treated group at baseline (p<0.03), but treatment did not augment this effect in either group. Bas = baseline conditions; Rx = post-treatment conditions.

In the pre-treatment studies there was no evident cross-sectional correlation of insulin sensitivity (whole body insulin-stimulated glucose uptake) with methacholine-induced vasodilation or with insulin-mediated vasodilation. Treatment with losartan did not bring out such relationships (not shown).

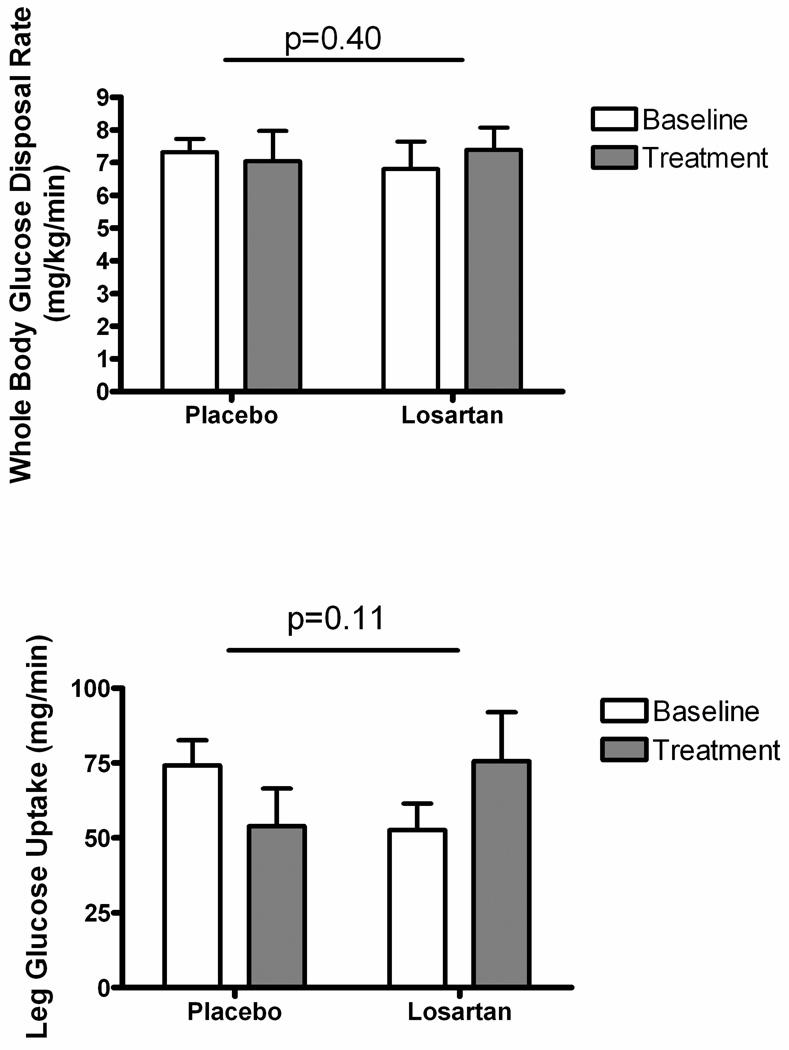

Metabolic actions of insulin

Insulin-stimulated whole body glucose uptake was not different between treatment groups at study entry, with an observed range of 3.2 to 9.8 mg/kg/min. There was no apparent effect of losartan treatment to alter whole-body insulin sensitivity (p=0.40; Figure 4 upper panel).

Figure 4.

Effects of Losartan on Glucose Disposal. Upper panel, whole body glucose disposal at steady state of the insulin infusion; lower panel, leg glucose disposal at steady state of the insulin infusion. Statistical significance is presented for the comparison of treatment effect across groups.

Effects of insulin on skeletal muscle metabolism were measured as insulin-stimulated leg glucose uptake (calculated as leg blood flow*A-V glucose difference, according to the Fick principle). These results are presented in Table 2 and Figure 4 lower panel. Losartan did not significantly augment insulin-stimulated increases in leg blood flow compared with placebo, consistent with the lack of treatment effect on leg vascular conductance described above. Arteriovenous glucose difference (i.e. leg glucose extraction) was not different between treatment groups at baseline, and not different between groups following treatment. There was no significant effect of losartan to increase insulin-stimulated leg glucose uptake compared with placebo (p=0.11 for treatment differences across groups).

Table 2.

Effect of Losartan on Skeletal Muscle Vascular Responses to Insulin

| Placebo | Losartan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Treatment | Baseline | Treatment | p | |

| Leg blood flow -Basal (L/min) | 0.257±0.016 | 0.222±0.020 | 0.243±0.016 | 0.271±0.016 | 0.09 |

| Leg blood flow - SS (L/min) | 0.356±0.028 | 0.327±0.049 | 0.289±0.026 | 0.353±0.046 | 0.24 |

| A-V glucose difference–SS (mmol/L) | 1.16±0.14 | 0.96±0.16 | 1.02±0.13 | 1.17±0.14 | 0.21 |

| Leg glucose uptake-SS (mmol/min) | 0.41±0.05 | 0.30±0.09 | 0.29±0.05 | 0.42±0.08 | 0.11 |

Note: P values represent the effect of treatment across groups. SS indicates steady state of the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp. Values are presented as mean±SEM.

Planned post-hoc analyses were performed comparing responses in subjects whose baseline insulin sensitivity was above or below the median, in order to consider the possibility of an effect manifesting only in the more insulin-resistant subjects. There was no significant effect of losartan treatment to augment insulin’s vascular or metabolic actions in any of the above parameters even within the insulin resistant subset of subjects (not shown). We also repeated the core analyses incorporating blood pressure covariates. Here we observed a significant relationship of baseline blood pressures with whole body glucose uptake, leg A-V glucose difference, insulin-mediated vasodilation and leg glucose uptake (not shown). These relationships were unchanged with treatment. Losartan did not significantly affect BMI (not shown), or beta cell function or adipose insulin sensitivity (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effects of Losartan on Systemic Metabolism

| Placebo | Losartan | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Treatment | Baseline | Treatment | P value | |

| Fasting glucose (mmol/L) | 5.7±0.3 | 5.4±0.3 | 5.8±0.3 | 5.6±0.2 | 0.85 |

| 2hr OGTT glucose (mmol/L) | 7.7±0.7 | 7.1±0.3 | 7.0±0.8 | 6.9±0.8 | 0.44 |

| Insulinogenic Index (mU/mmol*100) | 3.88±0.65 | 3.72±1.21 | 4.37±1.38 | 3.58±1.04 | 0.38 |

| Fasting FFA (mmol/L) | 0.50±0.07 | 0.31±0.05 | 0.46±0.09 | 0.46±1.0 | 0.16 |

| Clamp ΔFFA (mmol/L) | 0.43±0.04 | 0.17±0.05 | 0.37±0.07 | 0.39±0.09 | 0.06 |

Note: P values represent the effect of treatment across groups. Values are presented as mean±SEM. FFA = free fatty acids. Clamp ΔFFA indicates insulin-induced suppression of free fatty acids.

Discussion

We evaluated a hypothesized effect of losartan to augment insulin-mediated vasodilation in skeletal muscle, and thereby to augment whole body insulin sensitivity, in obese insulin resistant subjects without hypertension or type 2 diabetes mellitus. We found no evidence for an effect of losartan to improve any parameter of insulin’s vascular actions in skeletal muscle in this study population. Insulin-stimulated leg glucose uptake and insulin-stimulated whole body glucose uptake were also not significantly improved by losartan. These findings argue against an effect of losartan to improve whole-body insulin sensitivity by augmenting insulin-mediated vasodilation in obese insulin resistant subjects without hypertension or type 2 diabetes.

Many studies of metabolic effects of ACE inhibitors (ACEI) and angiotensin receptor antagonists (ARBs) have reported significant improvements in whole-body insulin-mediated glucose disposal (3–14) but there have been notable exceptions (15–18). Positive and negative findings have been reported in studies using both ACEI and ARBs. The most important difference between prior positive studies and the current report is that our study included obese subjects without hypertension or diabetes mellitus. A related observation is that subjects with Type 1 diabetes without hypertension and with acceptable glucose control do not receive the same benefits in prevention of microvascular disease with ACEI/ARBs (37, 38). Together with the current results, these observations point to benefits of ACEI/ARB in diabetes that are tied to the presence of hypertension.

The changes in blood pressure, together with the evidence from pill counting, argue against a false negative finding due to poor medication compliance, and the 12 week exposure was chosen to avoid concerns about insufficient treatment duration. We observed slightly greater measurement noise in this study than used in our power calculations, but the unchanged apparent mean responses in insulin-mediated vasodilation (measured either as leg blood flow or leg vascular conductance) support the conclusion of an absent effect. The statistical design was configured to detect clinically relevant effects, namely changes on the order of the difference between lean and obese subjects. The observed effects did not even approach this magnitude of difference, as reflected in the high p values. Further, negative findings were obtained with 3 different ways of evaluating insulin’s vascular actions (direct vasodilation, NO-dependent effects, and augmentation of acetylcholine-induced dilation). Together these findings convincingly argue that the lack of improvement in insulin-mediated vasodilation is a true negative, not limited by statistical power.

Where beneficial effects of ACEI and ARB on glucose metabolism have been observed, data do not consistently support vascular actions as a mediator of these benefits. Paolisso and colleagues (39), studying effects of losartan in hypertensive subjects, and Bonora and colleagues (7), studying effects of lisinopril in type 2 diabetic subjects, reported improvements in non-oxidative glucose disposal with losartan treatment, sufficient to explain the observed augmentation in whole-body insulin resistance (i.e. without invoking effects on insulin’s vascular actions). In the former study insulin-induced augmentation of femoral artery blood flow, measured using ultrasound, was concurrently increased by losartan, with a positive correlation between changes in insulin’s vascular and metabolic effects (39). Studying obese type 2 diabetic subjects, Hermann and colleagues found that quinapril augmented insulin-induced vasodilation and insulin’s effects to augment endothelium-dependent vasodilation in forearm resistance vessels (40). In a LIFE substudy, Olsen and colleagues reported worsening whole-body insulin-stimulated glucose disposal with atenolol but stable values with losartan (17). This was interpreted as preservation of insulin sensitivity with losartan. Similar findings were reported in a large clinical trial using simple measures of insulin sensitivity (13). It is possible that using other techniques, such as microbubble measurement of tissue perfusion effects of insulin (20, 21), could allow demonstration of pertinent vascular effects that contribute to tissue insulin actions without resulting in whole-limb changes in blood flow.

The observed changes in leg glucose uptake did not achieve significance but were directionally consistent with a beneficial losartan effect. This was not a predicted outcome under the current study hypothesis. Since no beneficial effects on insulin’s vascular actions were seen, this suggests instead a potential effect on tissue glucose extraction. There is only one published study to compare against our data regarding arteriovenous glucose differences and effects on limb glucose uptake. Galletti and colleagues (8) compared effects of nifedipine and trandolapril on whole-body insulin resistance, and evaluated effects of treatment on insulin-stimulated arm glucose uptake in a manner parallel to the current report. Similar to the current report, they saw no treatment effect on limb blood flow, but did observe a modest increase in A-V glucose difference and a ~70% increase in limb glucose uptake in ACEI-treated subjects. Our losartan-treated subjects exhibited a ~45% increase in leg glucose uptake, not reaching significance. Together these observations, suggest a possible effect of ACEI or ARB on cellular glucose extraction independent of effects on tissue perfusion. This question has been directly evaluated using reverse microdialysis in healthy humans (41). In that report, perfusion of subcutaneous fat with enalaprilat and bradykinin augmented tissue glucose transport, but this was not seen with losartan. This novel hypothesis requires further study.

We measured serum potassium concentrations as a safety parameter before and following 2 weeks’ treatment on study medications, and did not observe any clinically important changes. We did not obtain repeat measures at end of study. Similarly, we did not measure treatment effects on other circulating factors of potential relevance such as angiotensin metabolites, aldosterone, catecholamines, endothelin, or natriuretic peptides. These might have been of interest as hypothesis-generating measures to explore potential mediators of an observed benefit, but with the current results we chose not to pursue such measurements.

The mechanism of previously reported beneficial effects of ACEI/ARB on systemic metabolism remains unexplained. We did not observe beneficial effects of losartan treatment on other aspects of whole-body metabolism, although we did observe a treatment difference in adipose insulin sensitivity that approached significance (Table 3). Other authors have reported improvements in beta cell function (12, 14), including one report where gold-standard measures of first and second phase glucose-stimulated insulin release were improved by valsartan (12). We saw no improvement in the insulinogenic index, but we did not study individuals with baseline defects in beta cell function. Other potential non-vascular mechanisms include improvements in circulating adiponectin (42), reductions in oxidative stress (43), and reductions in circulating inflammatory mediators (44). Further study is required to explore these mechanisms.

In conclusion, 3 months’ treatment with losartan in obese normotensive insulin resistant subjects failed to improve insulin-mediated vasodilation, skeletal muscle glucose uptake, or whole-body glucose uptake. This is in contrast to prior studies in hypertensive subjects, suggesting that metabolic benefits of RAS antagonists may require the presence of hypertension.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by an Investigator Initiated Studies Program grant from Merck, Inc. We were also supported by the Indiana University General Clinical Research Center (NIH M01 RR00750). Dr Mather was supported in part by an American Diabetes Association Career Development Award. The expert technical assistance and hyperinsulinemic clamp expertise of Paula Robinett RN and Robin Chisholm RN is gratefully acknowledged.

Duality of Interest: This project was sponsored by Merck, Inc., under an Investigator Initiated Studies program. The sponsor had no input into the collection, analysis, interpretation or presentation of the results. Dr Mather serves on the Merck Speakers’ Bureau, regarding diabetes medications. Dr. Considine has support from Merck for unrelated projects, and has no other relationship with the sponsor.

Footnotes

No other authors have any dualities of interest to report.

References

- 1.Lindholm LH, Ibsen H, Borch-Johnsen K, Olsen MH, Wachtell K, Dahlof B, et al. Risk of new-onset diabetes in the Losartan Intervention For Endpoint reduction in hypertension study. J Hypertens. 2002;20(9):1879–1886. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200209000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abuissa H, Jones PG, Marso SP, O'Keefe JH., Jr Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers for prevention of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46(5):821–826. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yusuf S, Ostergren JB, Gerstein HC, Pfeffer MA, Swedberg K, Granger CB, et al. Effects of candesartan on the development of a new diagnosis of diabetes mellitus in patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2005;112(1):48–53. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.528166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torlone E, Britta M, Rambotti AM, Perriello G, Santeusanio F, Brunetti P, et al. Improved insulin action and glycemic control after long-term angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in subjects with arterial hypertension and type II diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1993;16(10):1347–1355. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.10.1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moan A, Hoieggen A, Nordby G, Eide IK, Kjeldsen SE. Effects of losartan on insulin sensitivity in severe hypertension: connections through sympathetic nervous system activity? J Hum Hypertens. 1995;9(Suppl 5):S45–S50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paolisso G, Tagliamonte MR, Gambardella A, Manzella D, Gualdiero P, Varricchio G, et al. Losartan mediated improvement in insulin action is mainly due to an increase in non-oxidative glucose metabolism and blood flow in insulin- resistant hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens. 1997;11(5):307–312. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonora E, Targher G, Alberiche M, Bonadonna RC, Saggiani F, Zenere MB, et al. Effect of chronic treatment with lacidipine or lisinopril on intracellular partitioning of glucose metabolism in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(5):1544–1550. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.5.5700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galletti F, Strazzullo P, Capaldo B, Carretta R, Fabris F, Ferrara LA, et al. Controlled study of the effect of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition versus calcium-entry blockade on insulin sensitivity in overweight hypertensive patients: Trandolapril Italian Study (TRIS) J Hypertens. 1999;17(3):439–445. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917030-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lender D, Arauz-Pacheco C, Breen L, Mora-Mora P, Ramirez LC, Raskin P. A double blind comparison of the effects of amlodipine and enalapril on insulin sensitivity in hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12(3):298–303. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(98)00259-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olsen MH, Andersen UB, Wachtell K, Ibsen H, Dige-Petersen H. A possible link between endothelial dysfunction and insulin resistance in hypertension. A LIFE substudy. Losartan Intervention For Endpoint-Reduction in Hypertension. Blood Press. 2000;9(2–3):132–139. doi: 10.1080/080370500453474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aksnes TA, Reims HM, Guptha S, Moan A, Os I, Kjeldsen SE. Improved insulin sensitivity with the angiotensin II-receptor blocker losartan in patients with hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors. J Hum Hypertens. 2006;20(11):860–866. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Zijl NJ, Moors CC, Goossens GH, Hermans MM, Blaak EE, Diamant M. Valsartan improves {beta}-cell function and insulin sensitivity in subjects with impaired glucose metabolism: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(4):845–851. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sowers JR, Raij L, Jialal I, Egan BM, Ofili EO, Samuel R, et al. Angiotensin receptor blocker/diuretic combination preserves insulin responses in obese hypertensives. J Hypertens. 2010;28(8):1761–1769. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833af380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki K, Nakagawa O, Aizawa Y. Improved early-phase insulin response after candesartan treatment in hypertensive patients with impaired glucose tolerance. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2008;30(5):309–314. doi: 10.1080/10641960802269927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fogari R, Zoppi A, Lazzari P, Preti P, Mugellini A, Corradi L, et al. ACE inhibition but not angiotensin II antagonism reduces plasma fibrinogen and insulin resistance in overweight hypertensive patients. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1998;32(4):616–620. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199810000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petrie JR, Morris AD, Ueda S, Small M, Donnelly R, Connell JM, et al. Trandolapril does not improve insulin sensitivity in patients with hypertension and type 2 diabetes: a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(5):1882–1889. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.5.6599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olsen MH, Fossum E, Hoieggen A, Wachtell K, Hjerkinn E, Nesbitt SD, et al. Long-term treatment with losartan versus atenolol improves insulin sensitivity in hypertension: ICARUS, a LIFE substudy. J Hypertens. 2005;23(4):891–898. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000163160.60234.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parhofer KG, Birkeland KI, DeFronzo R, Del Prato S, Bhaumik A, Ptaszynska A. Irbesartan has no short-term effect on insulin resistance in hypertensive patients with additional cardiometabolic risk factors (i-RESPOND) Int J Clin Pract. 2010;64(2):160–168. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2009.02246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baron AD, Clark MG. Role of blood flow in the regulation of muscle glucose uptake. [Review] [34 refs] Annu Rev Nutr. 1997;17:487–499. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.17.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rattigan S, Barrett EJ, Clark MG. Insulin-mediated capillary recruitment in skeletal muscle: is this a mediator of insulin action on glucose metabolism? Curr Diab Rep. 2003;3(3):195–200. doi: 10.1007/s11892-003-0063-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vincent MA, Clerk LH, Lindner JR, Klibanov AL, Clark MG, Rattigan S, et al. Microvascular recruitment is an early insulin effect that regulates skeletal muscle glucose uptake in vivo. Diabetes. 2004;53(6):1418–1423. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.6.1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baron AD, Steinberg HO, Chaker H, Leaming R, Johnson A, Brechtel G. Insulin-mediated skeletal muscle vasodilation contributes to both insulin sensitivity and responsiveness in lean humans. J Clin Invest. 1995;96(2):786–792. doi: 10.1172/JCI118124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yavuz D, Koc M, Toprak A, Akpinar I, Velioglu A, Deyneli O, et al. Effects of ACE inhibition and AT1-receptor antagonism on endothelial function and insulin sensitivity in essential hypertensive patients. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2003;4(3):197–203. doi: 10.3317/jraas.2003.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomiyama H, Motobe K, Zaydun G, Koji Y, Yambe M, Arai T, et al. Insulin sensitivity and endothelial function in hypertension: a comparison of temocapril and candesartan. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(2 Pt 1):178–182. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flammer AJ, Hermann F, Wiesli P, Schwegler B, Chenevard R, Hurlimann D, et al. Effect of losartan, compared with atenolol, on endothelial function and oxidative stress in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension. J Hypertens. 2007;25(4):785–791. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3280287a72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taddei S, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Sudano I, Salvetti A. Antihypertensive drugs and reversing of endothelial dysfunction in hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2000;2(1):64–70. doi: 10.1007/s11906-000-0061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheetham C, Collis J, O'Driscoll G, Stanton K, Taylor R, Green D. Losartan, an angiotensin type 1 receptor antagonist, improves endothelial function in non-insulin-dependent diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(5):1461–1466. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00933-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrie JR, Ueda S, Webb DJ, Elliott HL, Connell JM. Endothelial nitric oxide production and insulin sensitivity. A physiological link with implications for pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 1996;93(7):1331–1333. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.7.1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paradisi G, Smith L, Burtner C, Leaming R, Garvey WT, Hook G, et al. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry assessment of fat mass distribution and its association with the insulin resistance syndrome. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(8):1310–1317. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.8.1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baron AD, Steinberg H, Brechtel G, Johnson A. Skeletal muscle blood flow independently modulates insulin-mediated glucose uptake. Am J Physiol. 1994;266(2 Pt 1):E248–E253. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.266.2.E248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lteif A, Vaishnava P, Baron AD, Mather KJ. Endothelin limits insulin action in obese/insulin-resistant humans. Diabetes. 2007;56(3):728–734. doi: 10.2337/db06-1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lteif AA, Fulford AD, Considine RV, Gelfand I, Baron AD, Mather KJ. Hyperinsulinemia fails to augment ET-1 action in the skeletal muscle vascular bed in vivo in humans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295(6):E1510–E1517. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.90549.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mather KJ, Lteif A, Steinberg HO, Baron AD. Interactions between endothelin and nitric oxide in the regulation of vascular tone in obesity and diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53(8):2060–2066. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.8.2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singal P, Muniyappa R, Chisholm R, Hall G, Chen H, Quon MJ, et al. Simple Modeling Allows Prediction of Steady-State Glucose Disposal Rate from Early Data in Hyperinsulinemic Glucose Clamps. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009 doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00603.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mather KJ, Mirzamohammadi B, Lteif A, Steinberg HO, Baron AD. Endothelin contributes to basal vascular tone and endothelial dysfunction in human obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2002;51(12):3517–3523. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.12.3517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steinberg HO, Chaker H, Leaming R, Johnson A, Brechtel G, Baron AD. Obesity/insulin resistance is associated with endothelial dysfunction. Implications for the syndrome of insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(11):2601–2610. doi: 10.1172/JCI118709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harindhanavudhi T, Mauer M, Klein R, Zinman B, Sinaiko A, Caramori ML. Benefits of Renin-Angiotensin blockade on retinopathy in type 1 diabetes vary with glycemic control. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(8):1838–1842. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mauer M, Zinman B, Gardiner R, Suissa S, Sinaiko A, Strand T, et al. Renal and retinal effects of enalapril and losartan in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):40–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paolisso G, Tagliamonte MR, Gambardella A, Manzella D, Gualdiero P, Varricchio G, et al. Losartan mediated improvement in insulin action is mainly due to an increase in non-oxidative glucose metabolism and blood flow in insulin-resistant hypertensive patients. J Hum Hypertens. 1997;11(5):307–312. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1000434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hermann TS, Li W, Dominguez H, Ihlemann N, Rask-Madsen C, Major-Pedersen A, et al. Quinapril treatment increases insulin-stimulated endothelial function and adiponectin gene expression in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(3):1001–1008. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frossard M, Joukhadar C, Steffen G, Schmid R, Eichler HG, Muller M. Paracrine effects of angiotensin-converting-enzyme- and angiotensin-II-receptor- inhibition on transcapillary glucose transport in humans. Life Sci. 2000;66(10):PL147–PL154. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00679-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nielsen S, Lihn AS, OS T, Mogensen CE, Schmitz O. Increased plasma adiponectin in losartan-treated type 1 diabetic patients. a mediator of improved insulin sensitivity? Horm Metab Res. 2004;36(3):194–196. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-814346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou MS, Schulman IH, Raij L. Role of angiotensin II and oxidative stress in vascular insulin resistance linked to hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;296(3):H833–H839. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01096.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Togashi N, Ura N, Higashiura K, Murakami H, Shimamoto K. The contribution of skeletal muscle tumor necrosis factor-alpha to insulin resistance and hypertension in fructose-fed rats. J Hypertens. 2000;18(11):1605–1610. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018110-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]