Abstract

Background:

This article addresses the treatment of VTE disease.

Methods:

We generated strong (Grade 1) and weak (Grade 2) recommendations based on high-quality (Grade A), moderate-quality (Grade B), and low-quality (Grade C) evidence.

Results:

For acute DVT or pulmonary embolism (PE), we recommend initial parenteral anticoagulant therapy (Grade 1B) or anticoagulation with rivaroxaban. We suggest low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) or fondaparinux over IV unfractionated heparin (Grade 2C) or subcutaneous unfractionated heparin (Grade 2B). We suggest thrombolytic therapy for PE with hypotension (Grade 2C). For proximal DVT or PE, we recommend treatment of 3 months over shorter periods (Grade 1B). For a first proximal DVT or PE that is provoked by surgery or by a nonsurgical transient risk factor, we recommend 3 months of therapy (Grade 1B; Grade 2B if provoked by a nonsurgical risk factor and low or moderate bleeding risk); that is unprovoked, we suggest extended therapy if bleeding risk is low or moderate (Grade 2B) and recommend 3 months of therapy if bleeding risk is high (Grade 1B); and that is associated with active cancer, we recommend extended therapy (Grade 1B; Grade 2B if high bleeding risk) and suggest LMWH over vitamin K antagonists (Grade 2B). We suggest vitamin K antagonists or LMWH over dabigatran or rivaroxaban (Grade 2B). We suggest compression stockings to prevent the postthrombotic syndrome (Grade 2B). For extensive superficial vein thrombosis, we suggest prophylactic-dose fondaparinux or LMWH over no anticoagulation (Grade 2B), and suggest fondaparinux over LMWH (Grade 2C).

Conclusion:

Strong recommendations apply to most patients, whereas weak recommendations are sensitive to differences among patients, including their preferences.

Summary of Recommendations

Note on Shaded Text: Throughout this guideline, shading is used within the summary of recommendations sections to indicate recommendations that are newly added or have been changed since the publication of Antithrombotic and Thrombolytic Therapy: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Recommendations that remain unchanged are not shaded.

2.1. In patients with acute DVT of the leg treated with vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy, we recommend initial treatment with parenteral anticoagulation (low-molecular-weight heparin [LMWH], fondaparinux, IV unfractionated heparin [UFH], or subcutaneous [SC] UFH) over no such initial treatment (Grade 1B).

2.2.1. In patients with a high clinical suspicion of acute VTE, we suggest treatment with parenteral anticoagulants compared with no treatment while awaiting the results of diagnostic tests (Grade 2C).

2.2.2. In patients with an intermediate clinical suspicion of acute VTE, we suggest treatment with parenteral anticoagulants compared with no treatment if the results of diagnostic tests are expected to be delayed for more than 4 h (Grade 2C).

2.2.3. In patients with a low clinical suspicion of acute VTE, we suggest not treating with parenteral anticoagulants while awaiting the results of diagnostic tests, provided test results are expected within 24 h (Grade 2C).

2.3.1. In patients with acute isolated distal DVT of the leg and without severe symptoms or risk factors for extension, we suggest serial imaging of the deep veins for 2 weeks over initial anticoagulation (Grade 2C).

2.3.2. In patients with acute isolated distal DVT of the leg and severe symptoms or risk factors for extension (see text), we suggest initial anticoagulation over serial imaging of the deep veins (Grade 2C).

Remarks: Patients at high risk for bleeding are more likely to benefit from serial imaging. Patients who place a high value on avoiding the inconvenience of repeat imaging and a low value on the inconvenience of treatment and on the potential for bleeding are likely to choose initial anticoagulation over serial imaging.

2.3.3. In patients with acute isolated distal DVT of the leg who are managed with initial anticoagulation, we recommend using the same approach as for patients with acute proximal DVT (Grade 1B).

2.3.4. In patients with acute isolated distal DVT of the leg who are managed with serial imaging, we recommend no anticoagulation if the thrombus does not extend (Grade 1B); we suggest anticoagulation if the thrombus extends but remains confined to the distal veins (Grade 2C); we recommend anticoagulation if the thrombus extends into the proximal veins (Grade 1B).

2.4. In patients with acute DVT of the leg, we recommend early initiation of VKA (eg, same day as parenteral therapy is started) over delayed initiation, and continuation of parenteral anticoagulation for a minimum of 5 days and until the international normalized ratio (INR) is 2.0 or above for at least 24 h (Grade 1B).

2.5.1. In patients with acute DVT of the leg, we suggest LMWH or fondaparinux over IV UFH (Grade 2C) and over SC UFH (Grade 2B for LMWH; Grade 2C for fondaparinux).

Remarks: Local considerations such as cost, availability, and familiarity of use dictate the choice between fondaparinux and LMWH.

LMWH and fondaparinux are retained in patients with renal impairment, whereas this is not a concern with UFH.

2.5.2. In patients with acute DVT of the leg treated with LMWH, we suggest once- over twice-daily administration (Grade 2C).

Remarks: This recommendation only applies when the approved once-daily regimen uses the same daily dose as the twice-daily regimen (ie, the once-daily injection contains double the dose of each twice-daily injection). It also places value on avoiding an extra injection per day.

2.7. In patients with acute DVT of the leg and whose home circumstances are adequate, we recommend initial treatment at home over treatment in hospital (Grade 1B).

Remarks: The recommendation is conditional on the adequacy of home circumstances: well-maintained living conditions, strong support from family or friends, phone access, and ability to quickly return to the hospital if there is deterioration. It is also conditional on the patient feeling well enough to be treated at home (eg, does not have severe leg symptoms or comorbidity).

2.9. In patients with acute proximal DVT of the leg, we suggest anticoagulant therapy alone over catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) (Grade 2C).

Remarks: Patients who are most likely to benefit from CDT (see text), who attach a high value to prevention of postthrombotic syndrome (PTS), and a lower value to the initial complexity, cost, and risk of bleeding with CDT, are likely to choose CDT over anticoagulation alone.

2.10. In patients with acute proximal DVT of the leg, we suggest anticoagulant therapy alone over systemic thrombolysis (Grade 2C).

Remarks: Patients who are most likely to benefit from systemic thrombolytic therapy (see text), who do not have access to CDT, and who attach a high value to prevention of PTS, and a lower value to the initial complexity, cost, and risk of bleeding with systemic thrombolytic therapy, are likely to choose systemic thrombolytic therapy over anticoagulation alone.

2.11. In patients with acute proximal DVT of the leg, we suggest anticoagulant therapy alone over operative venous thrombectomy (Grade 2C).

2.12. In patients with acute DVT of the leg who undergo thrombosis removal, we recommend the same intensity and duration of anticoagulant therapy as in comparable patients who do not undergo thrombosis removal (Grade 1B).

2.13.1. In patients with acute DVT of the leg, we recommend against the use of an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter in addition to anticoagulants (Grade 1B).

2.13.2. In patients with acute proximal DVT of the leg and contraindication to anticoagulation, we recommend the use of an IVC filter (Grade 1B).

2.13.3. In patients with acute proximal DVT of the leg and an IVC filter inserted as an alternative to anticoagulation, we suggest a conventional course of anticoagulant therapy if their risk of bleeding resolves (Grade 2B).

Remarks: We do not consider that a permanent IVC filter, of itself, is an indication for extended anticoagulation.

2.14. In patients with acute DVT of the leg, we suggest early ambulation over initial bed rest (Grade 2C).

Remarks: If edema and pain are severe, ambulation may need to be deferred. As per section 4.1, we suggest the use of compression therapy in these patients.

3.0. In patients with acute VTE who are treated with anticoagulant therapy, we recommend long-term therapy (see section 3.1 for recommended duration of therapy) over stopping anticoagulant therapy after about 1 week of initial therapy (Grade 1B).

3.1.1. In patients with a proximal DVT of the leg provoked by surgery, we recommend treatment with anticoagulation for 3 months over (i) treatment of a shorter period (Grade 1B), (ii) treatment of a longer time-limited period (eg, 6 or 12 months) (Grade 1B), or (iii) extended therapy (Grade 1B regardless of bleeding risk).

3.1.2. In patients with a proximal DVT of the leg provoked by a nonsurgical transient risk factor, we recommend treatment with anticoagulation for 3 months over (i) treatment of a shorter period (Grade 1B), (ii) treatment of a longer time-limited period (eg, 6 or 12 months) (Grade 1B), and (iii) extended therapy if there is a high bleeding risk (Grade 1B). We suggest treatment with anticoagulation for 3 months over extended therapy if there is a low or moderate bleeding risk (Grade 2B).

3.1.3. In patients with an isolated distal DVT of the leg provoked by surgery or by a nonsurgical transient risk factor (see remark), we suggest treatment with anticoagulation for 3 months over treatment of a shorter period (Grade 2C) and recommend treatment with anticoagulation for 3 months over treatment of a longer time-limited period (eg, 6 or 12 months) (Grade 1B) or extended therapy (Grade 1B regardless of bleeding risk).

3.1.4. In patients with an unprovoked DVT of the leg (isolated distal [see remark] or proximal), we recommend treatment with anticoagulation for at least 3 months over treatment of a shorter duration (Grade 1B). After 3 months of treatment, patients with unprovoked DVT of the leg should be evaluated for the risk-benefit ratio of extended therapy.

3.1.4.1. In patients with a first VTE that is an unprovoked proximal DVT of the leg and who have a low or moderate bleeding risk, we suggest extended anticoagulant therapy over 3 months of therapy (Grade 2B).

3.1.4.2. In patients with a first VTE that is an unprovoked proximal DVT of the leg and who have a high bleeding risk, we recommend 3 months of anticoagulant therapy over extended therapy (Grade 1B).

3.1.4.3. In patients with a first VTE that is an unprovoked isolated distal DVT of the leg (see remark), we suggest 3 months of anticoagulant therapy over extended therapy in those with a low or moderate bleeding risk (Grade 2B) and recommend 3 months of anticoagulant treatment in those with a high bleeding risk (Grade 1B).

3.1.4.4. In patients with a second unprovoked VTE, we recommend extended anticoagulant therapy over 3 months of therapy in those who have a low bleeding risk (Grade 1B), and we suggest extended anticoagulant therapy in those with a moderate bleeding risk (Grade 2B).

3.1.4.5. In patients with a second unprovoked VTE who have a high bleeding risk, we suggest 3 months of anticoagulant therapy over extended therapy (Grade 2B).

3.1.5. In patients with DVT of the leg and active cancer, if the risk of bleeding is not high, we recommend extended anticoagulant therapy over 3 months of therapy (Grade 1B), and if there is a high bleeding risk, we suggest extended anticoagulant therapy (Grade 2B).

Remarks (3.1.3, 3.1.4, 3.1.4.3): Duration of treatment of patients with isolated distal DVT refers to patients in whom a decision has been made to treat with anticoagulant therapy; however, it is anticipated that not all patients who are diagnosed with isolated distal DVT will be prescribed anticoagulants (see section 2.3).

In all patients who receive extended anticoagulant therapy, the continuing use of treatment should be reassessed at periodic intervals (eg, annually).

3.2. In patients with DVT of the leg who are treated with VKA, we recommend a therapeutic INR range of 2.0 to 3.0 (target INR of 2.5) over a lower (INR < 2) or higher (INR 3.0-5.0) range for all treatment durations (Grade 1B).

3.3.1. In patients with DVT of the leg and no cancer, we suggest VKA therapy over LMWH for long-term therapy (Grade 2C). For patients with DVT and no cancer who are not treated with VKA therapy, we suggest LMWH over dabigatran or rivaroxaban for long-term therapy (Grade 2C).

3.3.2. In patients with DVT of the leg and cancer, we suggest LMWH over VKA therapy (Grade 2B). In patients with DVT and cancer who are not treated with LMWH, we suggest VKA over dabigatran or rivaroxaban for long-term therapy (Grade 2B).

Remarks (3.3.1-3.3.2): Choice of treatment in patients with and without cancer is sensitive to the individual patient’s tolerance for daily injections, need for laboratory monitoring, and treatment costs.

LMWH, rivaroxaban, and dabigatran are retained in patients with renal impairment, whereas this is not a concern with VKA.

Treatment of VTE with dabigatran or rivaroxaban, in addition to being less burdensome to patients, may prove to be associated with better clinical outcomes than VKA and LMWH therapy. When these guidelines were being prepared (October 2011), postmarketing studies of safety were not available. Given the paucity of currently available data and that new data are rapidly emerging, we give a weak recommendation in favor of VKA and LMWH therapy over dabigatran and rivaroxaban, and we have not made any recommendations in favor of one of the new agents over the other.

3.4. In patients with DVT of the leg who receive extended therapy, we suggest treatment with the same anticoagulant chosen for the first 3 months (Grade 2C).

3.5. In patients who are incidentally found to have asymptomatic DVT of the leg, we suggest the same initial and long-term anticoagulation as for comparable patients with symptomatic DVT (Grade 2B).

4.1. In patients with acute symptomatic DVT of the leg, we suggest the use of compression stockings (Grade 2B).

Remarks: Compression stockings should be worn for 2 years, and we suggest beyond that if patients have developed PTS and find the stockings helpful.

Patients who place a low value on preventing PTS or a high value on avoiding the inconvenience and discomfort of stockings are likely to decline stockings.

4.2.1. In patients with PTS of the leg, we suggest a trial of compression stockings (Grade 2C).

4.2.2. In patients with severe PTS of the leg that is not adequately relieved by compression stockings, we suggest a trial of an intermittent compression device (Grade 2B).

4.3. In patients with PTS of the leg, we suggest that venoactive medications (eg, rutosides, defibrotide, and hidrosmin) not be used (Grade 2C).

Remarks: Patients who value the possibility of response over the risk of side effects may choose to undertake a therapeutic trial.

5.1. In patients with acute PE, we recommend initial treatment with parenteral anticoagulation (LMWH, fondaparinux, IV UFH, or SC UFH) over no such initial treatment (Grade 1B).

5.2.1. In patients with a high clinical suspicion of acute PE, we suggest treatment with parenteral anticoagulants compared with no treatment while awaiting the results of diagnostic tests (Grade 2C).

5.2.2. In patients with an intermediate clinical suspicion of acute PE, we suggest treatment with parenteral anticoagulants compared with no treatment if the results of diagnostic tests are expected to be delayed for more than 4 h (Grade 2C).

5.2.3. In patients with a low clinical suspicion of acute PE, we suggest not treating with parenteral anticoagulants while awaiting the results of diagnostic tests, provided test results are expected within 24 h (Grade 2C).

5.3. In patients with acute PE, we recommend early initiation of VKA (eg, same day as parenteral therapy is started) over delayed initiation, and continuation of parenteral anticoagulation for a minimum of 5 days and until the INR is 2.0 or above for at least 24 h (Grade 1B).

5.4.1. In patients with acute PE, we suggest LMWH or fondaparinux over IV UFH (Grade 2C for LMWH; Grade 2B for fondaparinux) and over SC UFH (Grade 2B for LMWH; Grade 2C for fondaparinux).

Remarks: Local considerations such as cost, availability, and familiarity of use dictate the choice between fondaparinux and LMWH.

LMWH and fondaparinux are retained in patients with renal impairment, whereas this is not a concern with UFH.

In patients with PE where there is concern about the adequacy of SC absorption or in patients in whom thrombolytic therapy is being considered or planned, initial treatment with IV UFH is preferred to use of SC therapies.

5.4.2. In patients with acute PE treated with LMWH, we suggest once- over twice-daily administration (Grade 2C).

Remarks: This recommendation only applies when the approved once-daily regimen uses the same daily dose as the twice-daily regimen (ie, the once-daily injection contains double the dose of each twice-daily injection). It also places value on avoiding an extra injection per day.

5.5. In patients with low-risk PE and whose home circumstances are adequate, we suggest early discharge over standard discharge (eg, after first 5 days of treatment) (Grade 2B).

Remarks: Patients who prefer the security of the hospital to the convenience and comfort of home are likely to choose hospitalization over home treatment.

5.6.1.1. In patients with acute PE associated with hypotension (eg, systolic BP < 90 mm Hg) who do not have a high bleeding risk, we suggest systemically administered thrombolytic therapy over no such therapy (Grade 2C).

5.6.1.2. In most patients with acute PE not associated with hypotension, we recommend against systemically administered thrombolytic therapy (Grade 1C).

5.6.1.3. In selected patients with acute PE not associated with hypotension and with a low bleeding risk whose initial clinical presentation, or clinical course after starting anticoagulant therapy, suggests a high risk of developing hypotension, we suggest administration of thrombolytic therapy (Grade 2C).

5.6.2.1. In patients with acute PE, when a thrombolytic agent is used, we suggest short infusion times (eg, a 2-h infusion) over prolonged infusion times (eg, a 24-h infusion) (Grade 2C).

5.6.2.2. In patients with acute PE when a thrombolytic agent is used, we suggest administration through a peripheral vein over a pulmonary artery catheter (Grade 2C).

5.7. In patients with acute PE associated with hypotension and who have (i) contraindications to thrombolysis, (ii) failed thrombolysis, or (iii) shock that is likely to cause death before systemic thrombolysis can take effect (eg, within hours), if appropriate expertise and resources are available, we suggest catheter-assisted thrombus removal over no such intervention (Grade 2C).

5.8. In patients with acute PE associated with hypotension, we suggest surgical pulmonary embolectomy over no such intervention if they have (i) contraindications to thrombolysis, (ii) failed thrombolysis or catheter-assisted embolectomy, or (iii) shock that is likely to cause death before thrombolysis can take effect (eg, within hours), provided surgical expertise and resources are available (Grade 2C).

5.9.1. In patients with acute PE who are treated with anticoagulants, we recommend against the use of an IVC filter (Grade 1B).

5.9.2. In patients with acute PE and contraindication to anticoagulation, we recommend the use of an IVC filter (Grade 1B).

5.9.3. In patients with acute PE and an IVC filter inserted as an alternative to anticoagulation, we suggest a conventional course of anticoagulant therapy if their risk of bleeding resolves (Grade 2B).

Remarks: We do not consider that a permanent IVC filter, of itself, is an indication for extended anticoagulation.

6.1. In patients with PE provoked by surgery, we recommend treatment with anticoagulation for 3 months over (i) treatment of a shorter period (Grade 1B), (ii) treatment of a longer time-limited period (eg, 6 or 12 months) (Grade 1B), or (iii) extended therapy (Grade 1B regardless of bleeding risk).

6.2. In patients with PE provoked by a nonsurgical transient risk factor, we recommend treatment with anticoagulation for 3 months over (i) treatment of a shorter period (Grade 1B), (ii) treatment of a longer time-limited period (eg, 6 or 12 months) (Grade 1B), and (iii) extended therapy if there is a high bleeding risk (Grade 1B). We suggest treatment with anticoagulation for 3 months over extended therapy if there is a low or moderate bleeding risk (Grade 2B).

6.3. In patients with an unprovoked PE, we recommend treatment with anticoagulation for at least 3 months over treatment of a shorter duration (Grade 1B). After 3 months of treatment, patients with unprovoked PE should be evaluated for the risk-benefit ratio of extended therapy.

6.3.1. In patients with a first VTE that is an unprovoked PE and who have a low or moderate bleeding risk, we suggest extended anticoagulant therapy over 3 months of therapy (Grade 2B).

6.3.2. In patients with a first VTE that is an unprovoked PE and who have a high bleeding risk, we recommend 3 months of anticoagulant therapy over extended therapy (Grade 1B).

6.3.3. In patients with a second unprovoked VTE, we recommend extended anticoagulant therapy over 3 months of therapy in those who have a low bleeding risk (Grade 1B), and we suggest extended anticoagulant therapy in those with a moderate bleeding risk (Grade 2B).

6.3.4. In patients with a second unprovoked VTE who have a high bleeding risk, we suggest 3 months of therapy over extended therapy (Grade 2B).

6.4. In patients with PE and active cancer, if there is a low or moderate bleeding risk, we recommend extended anticoagulant therapy over 3 months of therapy (Grade 1B), and if there is a high bleeding risk, we suggest extended anticoagulant therapy (Grade 2B).

Remarks: In all patients who receive extended anticoagulant therapy, the continuing use of treatment should be reassessed at periodic intervals (eg, annually).

6.5. In patients with PE who are treated with VKA, we recommend a therapeutic INR range of 2.0 to 3.0 (target INR of 2.5) over a lower (INR < 2) or higher (INR 3.0-5.0) range for all treatment durations (Grade 1B).

6.6. In patients with PE and no cancer, we suggest VKA therapy over LMWH for long-term therapy (Grade 2C). For patients with PE and no cancer who are not treated with VKA therapy, we suggest LMWH over dabigatran or rivaroxaban for long-term therapy (Grade 2C).

6.7. In patients with PE and cancer, we suggest LMWH over VKA therapy (Grade 2B). In patients with PE and cancer who are not treated with LMWH, we suggest VKA over dabigatran or rivaroxaban for long-term therapy (Grade 2C).

Remarks (6.6-6.7): Choice of treatment in patients with and without cancer is sensitive to the individual patient’s tolerance for daily injections, need for laboratory monitoring, and treatment costs.

Treatment of VTE with dabigatran or rivaroxaban, in addition to being less burdensome to patients, may prove to be associated with better clinical outcomes than VKA and LMWH therapy. When these guidelines were being prepared (October 2011), postmarketing studies of safety were not available. Given the paucity of currently available data and that new data are rapidly emerging, we give a weak recommendation in favor of VKA and LMWH therapy over dabigatran and rivaroxaban, and we have not made any recommendation in favor of one of the new agents over the other.

6.8. In patients with PE who receive extended therapy, we suggest treatment with the same anticoagulant chosen for the first 3 months (Grade 2C).

6.9. In patients who are incidentally found to have asymptomatic PE, we suggest the same initial and long-term anticoagulation as for comparable patients with symptomatic PE (Grade 2B).

7.1.1. In patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTPH), we recommend extended anticoagulation over stopping therapy (Grade 1B).

7.1.2. In selected patients with CTPH, such as those with central disease under the care of an experienced thromboendarterectomy team, we suggest pulmonary thromboendarterectomy over no pulmonary thromboendarterectomy (Grade 2C).

8.1.1. In patients with superficial vein thrombosis (SVT) of the lower limb of at least 5 cm in length, we suggest the use of a prophylactic dose of fondaparinux or LMWH for 45 days over no anticoagulation (Grade 2B).

Remarks: Patients who place a high value on avoiding the inconvenience or cost of anticoagulation and a low value on avoiding infrequent symptomatic VTE are likely to decline anticoagulation.

8.1.2. In patients with SVT who are treated with anticoagulation, we suggest fondaparinux 2.5 mg daily over a prophylactic dose of LMWH (Grade 2C).

9.1.1. In patients with acute upper-extremity DVT (UEDVT) that involves the axillary or more proximal veins, we recommend acute treatment with parenteral anticoagulation (LMWH, fondaparinux, IV UFH, or SC UFH) over no such acute treatment (Grade 1B).

9.1.2. In patients with acute UEDVT that involves the axillary or more proximal veins, we suggest LMWH or fondaparinux over IV UFH (Grade 2C) and over SC UFH (Grade 2B).

9.2.1. In patients with acute UEDVT that involves the axillary or more proximal veins, we suggest anticoagulant therapy alone over thrombolysis (Grade 2C).

Remarks: Patients who (i) are most likely to benefit from thrombolysis (see text); (ii) have access to CDT; (iii) attach a high value to prevention of PTS; and (iv) attach a lower value to the initial complexity, cost, and risk of bleeding with thrombolytic therapy are likely to choose thrombolytic therapy over anticoagulation alone.

9.2.2. In patients with UEDVT who undergo thrombolysis, we recommend the same intensity and duration of anticoagulant therapy as in similar patients who do not undergo thrombolysis (Grade 1B).

9.3.1. In most patients with UEDVT that is associated with a central venous catheter, we suggest that the catheter not be removed if it is functional and there is an ongoing need for the catheter (Grade 2C).

9.3.2. In patients with UEDVT that involves the axillary or more proximal veins, we suggest a minimum duration of anticoagulation of 3 months over a shorter period (Grade 2B).

Remarks: This recommendation also applies if the UEDVT was associated with a central venous catheter that was removed shortly after diagnosis.

9.3.3. In patients who have UEDVT that is associated with a central venous catheter that is removed, we recommend 3 months of anticoagulation over a longer duration of therapy in patients with no cancer (Grade 1B), and we suggest this in patients with cancer (Grade 2C).

9.3.4. In patients who have UEDVT that is associated with a central venous catheter that is not removed, we recommend that anticoagulation is continued as long as the central venous catheter remains over stopping after 3 months of treatment in patients with cancer (Grade 1C), and we suggest this in patients with no cancer (Grade 2C).

9.3.5. In patients who have UEDVT that is not associated with a central venous catheter or with cancer, we recommend 3 months of anticoagulation over a longer duration of therapy (Grade 1B).

9.4. In patients with acute symptomatic UEDVT, we suggest against the use of compression sleeves or venoactive medications (Grade 2C).

9.5.1. In patients who have PTS of the arm, we suggest a trial of compression bandages or sleeves to reduce symptoms (Grade 2C).

9.5.2. In patients with PTS of the arm, we suggest against treatment with venoactive medications (Grade 2C).

10.1. In patients with symptomatic splanchnic vein thrombosis (portal, mesenteric, and/or splenic vein thromboses), we recommend anticoagulation over no anticoagulation (Grade 1B).

10.2. In patients with incidentally detected splanchnic vein thrombosis (portal, mesenteric, and/or splenic vein thromboses), we suggest no anticoagulation over anticoagulation (Grade 2C).

11.1. In patients with symptomatic hepatic vein thrombosis, we suggest anticoagulation over no anticoagulation (Grade 2C).

11.2. In patients with incidentally detected hepatic vein thrombosis, we suggest no anticoagulation over anticoagulation (Grade 2C).

This article provides recommendations for the use of antithrombotic agents as well as the use of devices or surgical techniques in the treatment of patients with DVT and pulmonary embolism (PE), which are collectively referred to as VTE. We also provide recommendations for patients with (1) postthrombotic syndrome (PTS), (2) chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTPH), (3) incidentally diagnosed (asymptomatic) DVT or PE, (4) acute upper-extremity DVT (UEDVT), (5) superficial vein thrombosis (SVT), (6) splanchnic vein thrombosis, and (7) hepatic vein thrombosis.

Table 1 describes the populations, interventions, comparators, and outcomes (ie, PICO elements) for the questions addressed in this article and the design of the studies used to address them. Refer to Garcia et al,1 Ageno et al,2 and Holbrook et al3 in these guidelines for recommendations on the management of parenteral anticoagulation (dosing and monitoring) and oral anticoagulation (dosing and monitoring). Refer to Bates et al4 and Monagle et al5 in these guidelines for recommendations for pregnancy and neonates and children. The current article builds on previous versions of these guidelines and, most recently, the eighth edition.6

Table 1.

—Structured Clinical Questions

| Issue (Informal Question) | Structured PICO Question |

Methodology | |||

| Population | Intervention | Comparators | Outcome | ||

| Patient with acute DVT of the leg

(2.0-3.0) | |||||

| Initial anticoagulant (2.1) |

Patients with acute DVT of the leg |

Anticoagulation |

No anticoagulation |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs |

| Whether to treat while awaiting the results of the diagnostic

work-up (2.2.1-2.2.3) |

Patients with suspected acute DVT of the leg awaiting the results of

diagnostic tests |

Anticoagulation |

No anticoagulation |

PE, major bleeding, and mortality |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Whether to treat isolated distal thrombosis (2.3.1-2.3.4) |

Patient with acute isolated distal DVT of the leg |

Anticoagulation |

No anticoagulation |

DVT extension, PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Timing of initiation of VKA relative to the initiation of parenteral

anticoagulation (2.4) |

Patients with acute DVT of the leg |

Early initiation of VKA |

Delayed initiation of VKA |

DVT extension, PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Duration of initial anticoagulation (2.4) |

Patients with acute DVT of the leg |

Longer duration |

Shorter duration |

DVT extension, PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Choice and route of initial anticoagulant (2.5.1, 2.5.2,

2.6) |

Patients with acute DVT of the leg |

UFH IV or SQ |

LMWH, fondaparinux, rivaroxaban |

DVT extension, PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and PTS |

RCTs |

| Setting of initial anticoagulation (2.7) |

Patients with acute DVT of the leg |

In-hospital treatment |

At-home treatment |

DVT extension, PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and PTS |

RCTs |

| Role of thrombolytic and mechanical interventions

(2.9-2.12) |

Patients with acute proximal DVT of the leg |

Catheter directed thrombolysis |

No active thrombus removal or another method of thrombus

removal |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL,

PTS, shorter ICU and hospital stays, and acute

complications |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Systemic thrombolytic therapy | |||||

| Operative venous thrombectomy | |||||

| Role of IVC filters in addition to anticoagulation

(2.13.1) |

Patients with acute DVT of the leg started on

anticoagulation |

IVC filter |

No IVC filter |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, PTS, and

complications of procedure |

RCTs |

| Role of IVC filters when anticoagulation is contraindicated

(2.13.2) |

Patients with acute DVT of the leg and a contraindication to

anticoagulation |

IVC filter |

No IVC filter |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, PTS, and

complications of procedure |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Role of anticoagulation in patients who initially received an IVC

filter when contraindication to anticoagulation resolves

(2.13.3) |

Patients with acute DVT of the leg who initially received an IVC

filter, now contraindication to anticoagulation resolved |

Anticoagulation in addition to IVC filter |

No anticoagulation in addition to IVC filter |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, PTS, and

complications of procedure |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Role of early ambulation (2.14) |

Patients with acute DVT of the leg started on anticoagulant

treatment |

Early ambulation |

Initial bed rest |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, PTS, and

complications of procedure |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Long-term anticoagulation therapy (3.0) |

Patients with acute VTE of the leg |

Long-term anticoagulation therapy |

No long-term anticoagulation therapy |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs |

| Duration of long-term anticoagulation (3.1.1- 3.1.5) |

Patients with an acute DVT of the leg |

Longer duration |

Shorter duration |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs |

| Intensity of VKA (3.2) |

Patients with acute DVT of the leg |

INR 2-3 |

Higher or lower INR ranges |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs |

| Choice of long-term anticoagulant (3.3.1, 3.3.2, 3.4) |

Patients with acute DVT of the leg. |

LMWH, dabigatran, rivaroxaban |

VKA |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs |

| Whether to treat an incidentally diagnosed asymptomatic acute DVT of

the leg (3.5) |

Patients with incidentally diagnosed asymptomatic DVT of the

leg |

Anticoagulation |

No anticoagulation |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs |

| Patients with PTS of the leg | |||||

| Role of compression stocking in preventing PTS (4.1) |

Patients with acute DVT of the leg started on anticoagulant

treatment |

Compression stockings |

No compression stockings |

QOL, PTS, and recurrent DVT |

RCTs |

| Role of compression stocking in PTS (4.2.1) |

Patients with PTS of the leg |

Compression stockings |

No compression stockings |

QOL, symptomatic relief, ulceration |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Role of intermittent pneumatic compression in PTS (4.2.2) |

Patients with PTS of the leg |

Intermittent pneumatic compression |

No intermittent pneumatic compression |

QOL, symptomatic relief, ulceration |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Role of venoactive medications in PTS (4.3) |

Patients with PTS of the leg |

Venoactive medications |

No venoactive medications |

QOL, PTS, and recurrent DVT |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Patient with acute PE | |||||

| Initial anticoagulant (5.1) |

Patients with acute PE |

Anticoagulation |

No initial anticoagulation |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs |

| Whether to treat while awaiting the results of the diagnostic

work-up (5.2.1-5.2.3) |

Patients with suspected acute PE awaiting the results of the

diagnostic tests |

Anticoagulation |

No anticoagulation |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Timing of initiation of VKA relative to the initiation of parenteral

anticoagulation (5.3) |

Patients with acute PE |

Early initiation of VKA |

Delayed initiation of VKA |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Duration of initial anticoagulation (5.3) |

Patients with acute PE |

Longer duration |

Shorter duration |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Choice and route of initial anticoagulant (5.4.1, 5.4.2) |

Patients with acute DVT of the leg |

UFH IV or SQ |

LMWH, fondaparinux, and rivaroxaban |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs |

| Setting of initial anticoagulation (5.5) |

Patients with acute PE |

In-hospital treatment |

At-home treatment |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs |

| Thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute PE (5.6.1.1, 5.6.1.2,

5.6.1.3) |

Patients with acute PE |

Thrombolytic therapy |

No thrombolytic therapy |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs |

| Infusion time for thrombolytic therapy (5.6.2.1) |

Patients with acute PE requiring thrombolytic therapy |

Longer infusion time |

Shorter infusion time |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Venous access for thrombolytic therapy (5.6.2.2) |

Patients with acute PE requiring thrombolytic therapy |

Peripheral vein |

Pulmonary catheter |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Role of catheter-assisted thrombus removal (5.7) |

Patients with acute PE |

Use of catheter-assisted thrombus removal |

No use of catheter-assisted thrombus removal |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Role of surgical pulmonary embolectomy (5.8) |

Patients with acute PE |

Surgical pulmonary embolectomy |

No surgical pulmonary embolectomy |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Role of IVC filter in addition to anticoagulation in patients with

acute PE (5.9.1) |

Patients with acute PE started on anticoagulation |

IVC filter |

No IVC filter |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Role of IVC filters when anticoagulation is contraindicated

(5.9.2) |

Patients with acute PE and a contraindication to

anticoagulation |

IVC filter |

No IVC filter |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Role of anticoagulation in patients who initially received an IVC

filter when contraindication to anticoagulation resolves

(5.9.3) |

Patients with acute PE who initially received an IVC filter, now

contraindication to anticoagulation resolved |

Anticoagulation in addition to IVC filter |

No anticoagulation in addition to IVC filter |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Duration of long-term anticoagulation in patients with acute PE

(6.1-6.4) |

Patients with acute PE |

Longer duration |

Shorter duration |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Intensity of VKA (6.5) |

Patients with acute PE |

INR 2-3 |

Higher or lower INR range |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Choice of long-term anticoagulant (6.6, 6.7, 6.8) |

Patients with acute PE |

LMWH, dabigatran, rivaroxaban |

VKA |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs |

| Whether to treat an incidentally diagnosed asymptomatic acute PE

(6.9) |

Patients with incidentally diagnosed asymptomatic PE |

Anticoagulation |

No anticoagulation |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohorts |

| Patient with CTPH | |||||

| Role of oral anticoagulation in CTPH (7.1.1) |

Patients with CTPH |

Oral anticoagulation |

No oral anticoagulation |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Role of pulmonary thromboendarterectomy in CTPH (7.1.2) |

Patients with CTPH |

Pulmonary thromboendarterectomy |

No pulmonary thromboendarterectomy |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Patient with SVT | |||||

| Role of anticoagulation in SVT (8.1.1, 8.1.2) |

Patients with SVT |

Anticoagulation |

No anticoagulation or other anticoagulant |

DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, symptomatic relief, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Patient with acute UEDVT | |||||

| Acute anticoagulation (9.1.1, 9.1.2) |

Patients with UEDVT |

Parenteral anticoagulation |

No anticoagulation |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, and

PTS |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Role of thrombolytic therapy (9.2.1, 9.2.2) |

Patients with UEDVT |

Systemic thrombolytic therapy |

No systemic thrombolytic therapy |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, PTS, shorter

ICU and hospital stays, and acute complications |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Whether indwelling central venous catheter should be removed

(9.3.1) |

Patients with UEDVT and indwelling central venous catheter |

Removal of indwelling central venous catheter |

No removal of indwelling central venous catheter |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, PTS, shorter

ICU and hospital stays, and acute complications |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Duration of long-term anticoagulation (9.3.2-9.3.5) |

Patients with UEDVT and indwelling central venous catheter |

Longer duration |

Shorter duration |

Recurrent DVT and PE, major bleeding, mortality, QOL, PTS, shorter

ICU and hospital stays, and acute complications |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Prevention of PTS of the arm (9.4) |

Patients with UEDVT |

Compression sleeves or venoactive medications |

No compression sleeves or venoactive medications |

QOL, PTS, and recurrent DVT |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Treatment of PTS of the arm (9.5.1, 9.5.2) |

Patients with PTS of the arm |

Compression sleeves or venoactive medications |

No compression sleeves or venoactive medications |

QOL, symptomatic relief, and ulceration |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Patient with thrombosis in unusual

sites | |||||

| Role of anticoagulation in splanchnic vein thrombosis (10.1,

10.2) |

Patients with splanchnic vein thrombosis |

Anticoagulation |

No anticoagulation |

Mortality, bowel ischemia, major bleeding, QOL, and symptomatic

relief |

RCTs and cohort studies |

| Role of anticoagulation in hepatic vein thrombosis (11.1, 11.2) | Patients with hepatic vein thrombosis | Anticoagulation | No anticoagulation | Mortality, liver failure, PE, major bleeding, QOL, and symptomatic relief | RCTs and cohort studies |

CTPH = chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; INR = international normalized ratio; IVC = inferior vena cava; LMWH = low-molecular-weight heparin, PE = pulmonary embolism; PICO = population, intervention, comparator, outcome; PTS = postthrombotic syndrome, QOL = quality of life; RCT = randomized controlled trial; SVT = superficial vein thrombosis; UEDVT = upper-extremity DVT; UFH = unfractionated heparin, VKA = vitamin K antagonist.

1.0 Methods

1.1 Presentation as DVT or PE

In addressing DVT, we first review studies that included (1) only patients who presented with symptomatic DVT or (2) patients who presented with DVT or PE (ie, meeting the broader criterion of VTE). For the PE components, we review studies (and subgroups within studies) that required patients to have presented with symptomatic PE (who may also have had symptoms of DVT). For this reason and because more patients with VTE present with symptoms of DVT alone than with symptoms of PE (including those who also have symptoms of DVT), the DVT section deals with a larger body of evidence than the PE section.

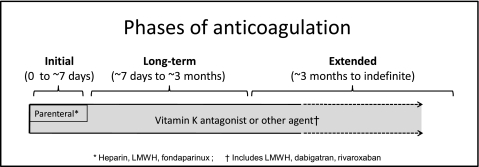

In the evaluation of anticoagulant therapy, there are a number of justifications for inclusion of patients who present with DVT and PE in the same study, and for extrapolating evidence obtained in patients with one presentation of VTE (eg, DVT) to the other presentation (eg, PE). First, a majority of patients with symptomatic DVT also have PE (symptomatic or asymptomatic), and a majority of those with symptomatic PE also have DVT (symptomatic or asymptomatic).7,8 Second, clinical trials of anticoagulant therapy have yielded similar estimates for efficacy and safety in patients with DVT alone, in those with both DVT and PE, and in those with only PE. Third, the risk of recurrence appears to be similar after PE and after proximal DVT.7,9 Consequently, the results of all studies of VTE have been considered when formulating recommendations for short- and long-term anticoagulation of proximal DVT and PE (Fig 1), and these recommendations are essentially the same for proximal DVT or PE.

Figure 1.

Phases of anticoagulation. LMWH = low-molecular-weight heparin.

There are, however, some important differences between patients who present with PE and those who present with DVT that justify separate consideration of some aspects of the treatment of PE. First, the risk of early death (within 1 month) from VTE due to either the initial acute episode or recurrent VTE is much greater after presenting with PE than after DVT9; this difference may justify more aggressive initial treatment of PE (eg, thrombolytic therapy, insertion of an inferior vena cava (IVC) filter, more intensive anticoagulant therapy) compared with DVT. Second, recurrent episodes of VTE are about three times as likely to be PE after an initial PE than after an initial DVT (ie, about 60% after a PE vs 20% after a DVT)7,9,10; this difference may justify more aggressive, or more prolonged, long-term therapy. Third, the long-term sequelae of PE are cardiorespiratory impairment, especially due to pulmonary hypertension, rather than PTS of the legs or arms. These differences are most important for recommendations about the use of thrombus removal procedures (eg, thrombolytic therapy) in patients who present with DVT and PE.

1.2 Outcomes Assessed

The outcomes important to patients we considered for most recommendations are recurrent VTE, major bleeding, and all-cause mortality. These outcomes are categorized in two different ways in the evidence profiles. Whenever data were available, fatal episodes of recurrent VTE and bleeding were included in the mortality outcome, and nonfatal episodes of recurrent VTE and bleeding were reported separately in their own categories to avoid reporting an outcome more than once in an evidence profile. However, many original reports and published meta-analyses did not report fatal and nonfatal events separately. In this situation, we have reported the outcome categories of mortality, recurrent VTE, and major bleeding, with fatal episodes of VTE and bleeding included in both mortality and two specific outcomes (ie, fatal episodes of VTE and bleeding are included in two outcomes of the evidence profile).

With both ways of reporting outcomes, we tried to specifically identify deaths from recurrent VTEs and major bleeds. As part of the assessment of the benefits and harms of a therapy, we generally assume that ∼5% of recurrent episodes of VTE are fatal11,12 and that ∼10% of major bleeds are fatal,12‐14 and if we deviated from these estimates, we noted the reasons for so doing. We did not consider surrogate outcomes (eg, vein patency) when there were adequate data addressing the corresponding outcome of importance to patients (eg, PTS).

When developing evidence profiles, we tried to obtain the baseline risk of outcomes (eg, risk of recurrent VTE or major bleeding) from observational studies because these estimates are most likely to reflect real-life incidence. In many cases, however, we used data from randomized trials because observational data were lacking or were of low quality. Methodologic issues specific to duration of anticoagulation are addressed in the section 3.1 under the subsection on general consideration in weighing the benefits and risks of different durations of anticoagulant therapy.

1.3 Patient Values and Preferences

In developing our recommendations, we took into account average patient values for each outcome and preferences for different types of antithrombotic therapy. As described in MacLean et al15 and Guyatt et al16 in these guidelines, these values and preferences for the most part were obtained from ratings that all panelists for these guidelines provided in response to standardized descriptions of different outcomes and treatments, supplemented with the findings of a systematic review of the literature on this topic.15 However, we also took into account that values and preferences vary markedly among individual patients and that often there is appreciable uncertainty about the average patient values we used.

On average, we assumed that patients attach equal value (or dislike [disutility]) to nonfatal thromboembolic and major bleeding events. Concern that the panelist rating exercise that attached a similar disutility to vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy (frequent blood testing and telephone or clinic visits, attention to changes in other medications) and long-term low-molecular-weight-heparin (LMWH) therapy (daily subcutaneous [SC] injection, injection site bruising or nodules) may have been misguided led us to request a review of this issue at the final meeting of all panelists. Our judgment that, on average, patients would prefer VKA therapy to long-term LMWH therapy was confirmed at that meeting.

1.4 Influence of Bleeding Risk and Cost

Usually, we did not assess how an individual patient’s risk of bleeding would influence each recommendation because (1) we considered that most recommendations would be unlikely to change based on differences in risk of bleeding (eg, anticoagulation vs no anticoagulation for acute VTE, comparison of anticoagulant regimens), (2) there are few data assessing outcomes in patients with different risks of bleeding, and (3) there is a lack of well-validated tools for stratifying risk of bleeding in patients with VTE. However, for a small number of the recommendations in which the risk of bleeding is very influential (eg, use of extended-duration anticoagulation), we stratified recommendations based on this risk (Table 2). Unless otherwise stated, the cost (eg, to the patient, a third-party payer, or society) associated with different treatments did not influence our recommendations. In most situations of uncertain benefit of a treatment, particularly if it was potentially harmful, we took the position of primum non nocere (first do no harm) and made a weak recommendation against the treatment.

Table 2.

—[Section 2.3, 3] Risk Factors for Bleeding With Anticoagulant Therapy and Estimated Risk of Major Bleeding in Low-, Moderate-, and High-Risk Categories

| Risk Factorsa | |||

| Age > 65 y17-25 | |||

| Age > 75 y17-21,23,25-34 | |||

| Previous

bleeding18,24,25,30,33-36 | |||

| Cancer20,24,30,37 | |||

| Metastatic cancer36.38, | |||

| Renal failure18,24,25,28,30,33 | |||

| Liver failure19,21,27,28 | |||

| Thrombocytopenia27,36 | |||

| Previous stroke18,25,27,39 | |||

| Diabetes18,19,28,32,34 | |||

| Anemia18,21,27,30,34 | |||

| Antiplatelet

therapy19,27,28,34,40 | |||

| Poor anticoagulant

control22,28,35 | |||

| Comorbidity and reduced functional

capacity24,28,36 | |||

| Recent surgery21,41,b | |||

| Frequent falls27 | |||

| Alcohol abuse24,25,27,34 | |||

| Estimated Absolute Risk of Major

Bleeding, % | |||

| Categorization of Risk of Bleedingc |

Low Riskd (0 Risk Factors) |

Moderate Riskd (1 Risk Factor) |

High Riskd (≥ 2 Risk

Factors) |

| Anticoagulation 0-3 moe | |||

| Baseline risk (%) |

0.6 |

1.2 |

4.8 |

| Increased risk (%) |

1.0 |

2.0 |

8.0 |

| Total risk (%) |

1.6e |

3.2 |

12.8f |

| Anticoagulation after first 3 mog | |||

| Baseline risk (%/y) |

0.3h |

0.6 |

≥ 2.5 |

| Increased risk (%/y) |

0.5 |

1.0 |

≥ 4.0 |

| Total risk (%/y) | 0.8i | 1.6i | ≥ 6.5 |

See Table 1 legend for expansion of abbreviations.

The increase in bleeding associated with a risk factor will vary with (1) severity of the risk factor (eg, location and extent of metastatic disease, platelet count), (2) temporal relationships (eg, interval from surgery or a previous bleeding episode),29 and (3) how effectively a previous cause of bleeding was corrected (eg, upper-GI bleeding).

Important for parenteral anticoagulation (eg, first 10 d) but less important for long-term or extended anticoagulation.

Although there is evidence that risk of bleeding increases with the prevalence of risk factors,20,21,25,27,30,33,34,36,42,43 this categorization scheme has not been validated. Furthermore, a single risk factor, when severe, will result in a high risk of bleeding (eg, major surgery within the past 2 d, severe thrombocytopenia).

Compared with low-risk patients, moderate-risk patients are assumed to have a twofold risk and high-risk patients an eightfold risk of major bleeding.18,20,21,27,28,30,36,44

The 1.6% corresponds to the average of major bleeding with initial UFH or LMWH therapy followed by VKA therapy (Table S6 Evidence Profile: LMWH vs IV UFH for initial anticoagulation of acute VTE). We estimated baseline risk by assuming a 2.6 relative risk of major bleeding with anticoagulation (footnote g in this table).

Consistent with frequency of major bleeding observed by Hull et al41 in high-risk patients.

We estimate that anticoagulation is associated with a 2.6-fold increase in major bleeding based on comparison of extended anticoagulation with no extended anticoagulation (Table S27 Evidence Profile: extended anticoagulation vs no extended anticoagulation for different groups of patients with VTE and without cancer). The relative risk of major bleeding during the first 3 mo of therapy may be greater that during extended VKA therapy because (1) the intensity of anticoagulation with initial parenteral therapy may be greater than with VKA therapy; (2) anticoagulant control will be less stable during the first 3 mo; and (3) predispositions to anticoagulant-induced bleeding may be uncovered during the first 3 mo of therapy.22,30,35 However, studies of patients with acute coronary syndromes do not suggest a ≥ 2.6 relative risk of major bleeding with parenteral anticoagulation (eg, UFH or LMWH) compared with control.45,46

Our estimated baseline risk of major bleeding for low-risk patients (and adjusted up for moderate- and high-risk groups as per footnote d in this table).

2.0 Treatment of Acute DVT

2.1 Initial Anticoagulation of Acute DVT of the Leg

The first and only randomized trial that compared anticoagulant therapy with no anticoagulant therapy in patients with symptomatic DVT or PE was published in 1960 by Barritt and Jordan.50 Trial results suggested that 1.5 days of heparin and 14 days of VKA therapy markedly reduced recurrent PE (0/16 vs 10/19) and appeared to reduce mortality (1/16 vs 5/19) in patients with acute PE. In the early 1990s, a single randomized trial established the need for an initial course of heparin in addition to VKA as compared with starting treatment with VKA therapy alone51 (Table 3, Table S1). (Tables that contain an “S” before the number denote supplementary tables not contained in the body of the article and available instead in an online data supplement. See the “Acknowledgments” for more information.) The need for an initial course of heparin is also supported by the observation that there are high rates of recurrent VTE during 3 months of follow-up in patients with acute VTE treated with suboptimal heparin therapy.1,3,52,53 We discuss whether isolated distal (calf) DVT should be sought and if isolated distal DVT is diagnosed, whether and how it should be treated in section 2.3.

Table 3.

—[Section 2.1] Summary of Findings: Parenteral Anticoagulation vs No Parenteral Anticoagulation in Acute VTEa,51

| Outcomes | No. of Participants (Studies), Follow-up | Quality of the Evidence (GRADE) | Relative Effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute

effects |

|

| Risk With No Parenteral Anticoagulation | Risk Difference With Parenteral Anticoagulation (95% CI) | ||||

| Mortality |

120 (1 study), 6 mo |

Moderateb,c due to imprecision |

RR 0.5 (0.05-5.37) |

33 per 1,000 |

16 fewer per 1,000 (from 31 fewer to 144 more) |

| VTE symptomatic extension or recurrence |

120 (1 study), 6 mo |

Moderateb,d due to imprecision |

RR 0.33 (0.11-0.98) |

200 per 1,000 |

134 fewer per 1,000 (from 4 fewer to 178 fewer) |

| Major bleeding | 120 (1 study), 6 mo | Moderateb,c due to imprecision | RR 0.67 (0.12-3.85) | 50 per 1,000 | 16 fewer per 1,000 (from 44 fewer to 142 more) |

The basis for the assumed risk (eg, the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Working group grades of evidence are as follow: High quality, further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect; moderate quality, further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; low quality, further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; very-low quality, we are very uncertain about the estimate. GRADE = Grades of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; RR = risk ratio.

Both groups treated with acenocoumarol

Study described as double blinded; outcome adjudicators blinded. None of the study participants were lost to follow-up. Intention-to-treat analysis. Study was stopped early for benefit.

CI includes values suggesting no effect as well as values suggesting either appreciable benefit or appreciable harm.

Low number of events caused by the early stoppage of the trial.

Recommendation

2.1. In patients with acute DVT of the leg treated with VKA therapy, we recommend initial treatment with parenteral anticoagulation (LMWH, fondaparinux, IV unfractionated heparin [UFH], or SC UFH) over no such initial treatment (Grade 1B).

2.2 Whether to Treat With Parenteral Anticoagulation While Awaiting the Results of Diagnostic Work-up for VTE

We identified no trial addressing this question. The decision regarding treatment while awaiting test results requires balancing (1) minimizing thrombotic complications in patients with VTE and (2) avoiding bleeding in those without VTE. Our recommendations are based on two principles. First, the higher the clinical suspicion for VTE (use of validated prediction models for probability of having DVT54 or PE55,56 can usefully inform this assessment,57 the shorter the acceptable interval without treatment until results of diagnostic testing become available. Second, the higher the risk of bleeding, the longer the acceptable interval without treatment until results are available.

Our recommendations assume that patients do not have major risk factors for bleeding, such as recent surgery. The recommendations also take into account that starting anticoagulant therapy in patients who ultimately have DVT excluded is costly and is a burden to patients and the health-care system. Poor cardiopulmonary reserve may also encourage the use of anticoagulant therapy while awaiting diagnostic testing. If clinicians choose to administer anticoagulant therapy and diagnostic testing will be completed within 12 h, we suggest using a 12-h over a 24-h dose of LMWH. VKA therapy usually should not be started before VTE has been confirmed.

Recommendations

2.2.1. In patients with a high clinical suspicion of acute VTE, we suggest treatment with parenteral anticoagulants compared with no treatment while awaiting the results of diagnostic tests (Grade 2C).

2.2.2. In patients with an intermediate clinical suspicion of acute VTE, we suggest treatment with parenteral anticoagulants compared with no treatment if the results of diagnostic tests are expected to be delayed for more than 4 h (Grade 2C).

2.2.3. In patients with a low clinical suspicion of acute VTE, we suggest not treating with parenteral anticoagulants while awaiting the results of diagnostic tests, provided test results are expected within 24 h (Grade 2C).

2.3 Whether and How to Prescribe Anticoagulants to Patients With Isolated Distal DVT

Whether to Look for Isolated Distal DVT and When to Prescribe Anticoagulants if Distal DVT Is Found:

Whether patients with isolated distal DVT (DVT of the calf [peroneal, posterior tibial, anterior tibial veins] without involvement of the popliteal or more proximal veins) are identified depends on how suspected DVT is investigated.57 If all patients with suspected DVT have ultrasound examination of the calf veins (whole-leg ultrasound), isolated distal DVT accounts for about one-half of all DVT diagnosed.58 If a diagnostic approach is used that does not include ultrasound examination of the calf veins or that only performs ultrasound examination of the calf veins in selected patients, isolated distal DVT is rarely diagnosed.59

The primary goal of diagnostic testing for DVT is to identify patients who will benefit from anticoagulant therapy. This does not mean that all symptomatic DVT need to be identified. Isolated distal DVT do not need to be sought and treated provided that (1) there is strong evidence that the patient does not have a distal DVT that will extend into the proximal veins (ie, the patient is unlikely to have a distal DVT, and if a distal DVT is present, it is unlikely to extend); (2) if this criterion is not satisfied, a follow-up proximal ultrasound is done after 1 week to detect distal DVT that has extended into the proximal veins, in which case anticoagulant therapy is started; and (3) the patient does not have severe symptoms that would require anticoagulant therapy if the symptoms were due to a distal DVT.

Diagnostic approaches to suspected DVT that do not examine the calf veins (eg, use of a combination of clinical assessment, D-dimer testing, single and serial proximal vein ultrasound examination to manage patients) or only examine the calf veins in selected patients (eg, those who cannot have DVT excluded using the previously noted tests) have been proven safe and are presented in Bates et al57 in these guidelines. If the calf veins are imaged (usually with ultrasound) and isolated distal DVT is diagnosed, there are two management options: (1) treat patients with anticoagulant therapy or (2) do not treat patients with anticoagulant therapy unless extension of the DVT is detected on a follow-up ultrasound examination (eg, after 1 and 2 weeks or sooner if there is concern [there is no widely accepted protocol for surveillance ultrasound testing]).60 Natural history studies suggest that when left untreated, ∼15% of symptomatic distal DVT will extend into the proximal veins and that if extension does not occur within 2 weeks, it is unlikely to occur subsequently.7,60‐62 The risk of extension of isolated distal DVT will vary among patients (see later discussion).

As noted in Bates et al,57 these guidelines favor diagnostic approaches to suspected DVT other than routine whole-leg ultrasound. If isolated distal DVT is diagnosed, depending on the severity of patient symptoms (the more severe the symptoms, the stronger the indication for anticoagulation) and the risk for thrombus extension (the greater the risk, the stronger the indication for anticoagulation), we suggest either (1) anticoagulation or (2) withholding of anticoagulation while performing surveillance ultrasound examinations to detect thrombus extension. We consider the following to be risk factors for extension: positive D-dimer, thrombosis that is extensive or close to the proximal veins (eg, > 5 cm in length, involves multiple veins, > 7 mm in maximum diameter), no reversible provoking factor for DVT, active cancer, history of VTE, and inpatient status.7,60,63,64 Thrombosis that is confined to the muscular veins has a lower risk of extension than true isolated distal DVT.63,65 We anticipate that isolated distal DVT detected using a selective approach to whole-leg ultrasound often will satisfy criteria for initial anticoagulation, whereas distal DVT detected by routine whole-leg ultrasound often will not. A high risk for bleeding (Table 2) favors ultrasound surveillance over initial anticoagulation, and the decision to use surveillance or initial anticoagulation is expected to be sensitive to patient preferences. The evidence supporting recommendations to prescribe anticoagulants for isolated calf DVT is low quality because it is not based on direct comparisons of the two management strategies, and the ability to predict extension of distal DVT is limited.

How to Treat With Anticoagulants:

A single controlled trial of 51 patients with symptomatic isolated distal DVT, all of whom were initially treated with heparin, found that 3 months of VKA therapy prevented DVT extension and recurrent VTE (29% vs 0%, P < .01).66 The evidence in support of parenteral anticoagulation and VKA therapy for isolated distal DVT, which includes indirect evidence from patients with acute proximal DVT and PE that is presented elsewhere in this article, is of moderate quality (there is high-quality evidence that anticoagulation is effective, but uncertainty that benefits outweigh risks). There have not been evaluations of alternatives to full-dose anticoagulation of symptomatic isolated distal DVT, and it is possible that less-aggressive anticoagulant strategies may be adequate. Duration of anticoagulation for isolated distal DVT is discussed in section 3.1.

Recommendations

2.3.1. In patients with acute isolated distal DVT of the leg and without severe symptoms or risk factors for extension (see text), we suggest serial imaging of the deep veins for 2 weeks over initial anticoagulation (Grade 2C).

2.3.2. In patients with acute isolated distal DVT of the leg and severe symptoms or risk factors for extension (see text), we suggest initial anticoagulation over serial imaging of the deep veins (Grade 2C).

Remarks: Patients at high risk for bleeding are more likely to benefit from serial imaging. Patients who place a high value on avoiding the inconvenience of repeat imaging and a low value on the inconvenience of treatment and on the potential for bleeding are likely to choose initial anticoagulation over serial imaging.

Recommendations

2.3.3. In patients with acute isolated distal DVT of the leg who are managed with initial anticoagulation, we recommend using the same approach as for patients with acute proximal DVT (Grade 1B).

2.3.4. In patients with acute isolated distal DVT of the leg who are managed with serial imaging, we recommend no anticoagulation if the thrombus does not extend (Grade 1B); we suggest anticoagulation if the thrombus extends but remains confined to the distal veins (Grade 2C); we recommend anticoagulation if the thrombus extends into the proximal veins (Grade 1B).

2.4 Timing of Initiation of VKA and Associated Duration of Parenteral Anticoagulant Therapy

Until ∼20 years ago, initiation of VKA therapy was delayed until patients had received about 5 days of heparin therapy, which resulted in patients remaining in the hospital until they had received ∼10 days of heparin. Three randomized trials41,67,68 provided moderate-quality evidence that early initiation of VKA, with shortening of heparin therapy to ∼5 days, is as effective as delayed initiation of VKA with about a 10-day course of heparin (Table 4, Table S2). Shortening the duration of initial heparin therapy from about 10 to 5 days is expected to have the added advantage of reducing the risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia.69 If the international normalized ratio (INR) exceeds the therapeutic range (ie, INR > 3.0) prematurely, it is acceptable to stop parenteral therapy before the patient has received 5 days of treatment.

Table 4.

—[Recommendation 2.4] Summary of Findings: Early Warfarin (and Shorter Duration Heparin) vs Delayed Warfarin (and Longer Duration Heparin) for Acute VTEa-d,41,67,68

| Outcomes | No. of Participants (Studies), Follow-up | Quality of the Evidence (GRADE) | Relative Effect (95% CI) | Anticipated Absolute

Effects |

|

| Risk With Delayed Warfarin Initiation (and Longer Duration Heparin) | Risk Difference With Early Warfarin Initiation (and Shorter Duration Heparin) (95% CI) | ||||

| Mortality |

688 (3 studies), 3 moe |

Moderatef,g due to imprecision |

RR 0.9 (0.41-1.95) |

24 per 1,000h |

2 fewer per 1,000 (from 14 fewer to 23 more) |

| Recurrent VTE |

688 (3 studies), 3 moe |

Moderatef,g due to imprecision |

RR 0.83 (0.4-1.74) |

47 per 1,000h |

8 fewer per 1,000 (from 28 fewer to 35 more) |

| Major bleeding | 688 (3 studies), 3 moi | Highf,j,k | RR 1.48 (0.68-3.23) | 16 per 1,000h | 14 more per 1,000 (from 9 fewer to 66 more) |

The basis for the assumed risk (eg, the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Working group grades of evidence are as follow: High quality, further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect; moderate quality, further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; low quality, further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; very-low quality, we are very uncertain about the estimate. See Table 1 and 3 legends for expansion of abbreviations.

Most patients had proximal DVT, some had isolated distal DVT, most DVT were symptomatic (asymptomatic DVT included in Hull et al41), and few had PE (only included in Gallus et al67).

The early initiation of VKA was associated with a fewer number of days of heparin therapy (4.1 vs 9.5 in Gallus et al67; 5 vs 10 in Hull et al41) and a fewer number of days of hospital stay (9.1 vs 13.0 in Gallus et al; 11.7 vs 14.7 in Hull et al; 11.9 vs 16.0 in Leroyer et al68).

VKA therapy started within 1 day of starting heparin therapy (UFH in two studies and LMWH in one study).

VKA therapy delayed for 4 to 10 d.

Outcome assessment was at hospital discharge in the study by Gallus et al67 (although there was also extended follow-up) and 3 mo in the studies by Hull et al41 and Leroyer et al.68

Patients and investigators were not blinded in two studies (Gallus et al67 and Leroyer et al68) and were blinded in one study (Hull et al41). Concealment was not clearly described but was probable in the three studies. Primary outcome appears to have been assessed after a shorter duration of follow-up in the shorter treatment arm of one study because of earlier discharge from hospital, and 20% of subjects in this study were excluded from the final analysis postrandomization (Gallus et al).

The 95% CI on relative effect includes both clinically important benefit and clinically important harm.

Event rate corresponds to the median event rate in the included studies.

Bleeding was assessed early (in hospital or in the first 10 d) in two studies (Gallus et al67 and Hull et al41) and at 3 mo in one study (Leroyer et al68).

It is unclear whether bleeding was assessed at 10 d in all subjects or just while heparin was being administered, which could yield a biased estimate in favor of short-duration therapy in one study (Hull et al41).

Because the shorter duration of heparin therapy is very unlikely to increase bleeding, the wide 95% CIs around the relative effect of shorter therapy on risk of bleeding is not a major concern.

Recommendation

2.4. In patients with acute DVT of the leg, we recommend early initiation of VKA (eg, same day as parenteral therapy is started) over delayed initiation, and continuation of parenteral anticoagulation for a minimum of 5 days and until the INR is 2.0 or above for at least 24 h (Grade 1B).

2.5 Choice of Initial Anticoagulant Regimen in Patients With Proximal DVT

Initial anticoagulant regimens vary according to the drug, the route of administration, and whether dose is adjusted in response to laboratory tests of coagulation. Six options are available for the initial treatment of DVT: (1) SC LMWH without monitoring, (2) IV UFH with monitoring, (3) SC UFH given based on weight initially, with monitoring, (4) SC UFH given based on weight initially, without monitoring, (5) SC fondaparinux given without monitoring, and (6) rivaroxaban given orally. We considered the SC UFH options as a single category because results were similar in studies that used SC UFH with and without laboratory monitoring (Table 5, Tables S3-S5). Rivaroxaban is used in the acute treatment of VTE without initial parenteral therapy; studies of its use for the acute treatment of VTE are reviewed under long-term treatment of DVT (section 3.1) and PE (section 6) of this article. Recommendations for dosing and monitoring of IV UFH, SC UFH, and SC LMWH are addressed in Garcia et al1 and Holbrook et al3 in these guidelines. Because LMWH, fondaparinux, and rivaroxaban have substantial renal excretion, these agents should be avoided (eg, use UFH instead) or should be used with coagulation monitoring (test selection is specific to each agent and requires expert interpretation) in patients with marked renal impairment (eg, estimated creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min [in a 70-year-old weighing 70 kg, a creatinine clearance of 30 mL/min corresponds to a serum creatinine of about 200 μmol/L (2.3 mg/dL) in a man and 175 μmol/L (2.0 mg/dL) in a woman] http://www.nephron.com/cgi-bin/CGSIdefault.cgi).

Table 5.

—[Section 2.5.1] Summary of Findings: LMWH vs SC UFH for Initial Anticoagulation of Acute VTE70,71,76,77

| Outcomes | No. of Participants (Studies), Follow-up | Quality of the Evidence (GRADE) | Relative Effect (95% CI) | Anticipated Absolute

Effects |

|

| Risk With SC UFH | Risk Difference With LMWH (95% CI) | ||||

| All-cause mortality |

1,566 (3 studies), 3 mo |

Moderatea,b due to imprecision |

RR 1.1 (0.68-1.76) |

33 per 1,000c |

3 more per 1,000 (from 11 fewer to 25 more) |

| Recurrent VTE |

1,563 (3 studies), 3 mo |

Moderatea,b due to imprecision |

RR 0.87 (0.52-1.45) |

42 per 1,000c |

5 fewer per 1,000 (from 20 fewer to 19 more) |

| Major bleeding | 1,634 (4 studies), 3 mo | Moderatea,b due to imprecision | RR 1.27 (0.56-2.9) | 16 per 1,000c | 4 more per 1,000 (from 7 fewer to 30 more) |

The basis for the assumed risk (eg, the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). Working group grades of evidence are as follow: High quality, further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect; moderate quality, further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate; low quality, further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; very-low quality, we are very uncertain about the estimate. SC = subcutaneous. See Table 1 and 3 legends for expansion of abbreviations.

In the two largest trials (Prandoni et al,70 Kearon et al;71 87% of patients), allocation was concealed, outcome adjudicators and data analysts were concealed, analysis was intention to treat, and there were no losses to follow-up.

Precision judged from the perspective of whether SC heparin is noninferior to LMWH. The total number of events and the total number of participants were relatively low.

Event rate corresponds to the median event rate in the included studies.

LMWH Compared With IV UFH for the Initial Treatment of DVT: