Abstract

Objectives

To determine the prevalence and health outcomes of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) colonisation in elderly care home residents. To measure the effectiveness of improving infection prevention knowledge and practice on MRSA prevalence.

Setting

Care homes for elderly residents in Leeds, UK.

Participants

Residents able to give informed consent.

Design

A controlled intervention study, using a stepped wedge design, comprising 65 homes divided into three groups. Baseline MRSA prevalence was determined by screening the nares of residents (n=2492). An intervention based upon staff education and training on hand hygiene was delivered at three different times according to group number. Scores for three assessment methods, an audit of hand hygiene facilities, staff hand hygiene observations and an educational questionnaire, were collected before and after the intervention. After each group of homes received the intervention, all participants were screened for MRSA nasal colonisation. In total, four surveys took place between November 2006 and February 2009.

Results

MRSA prevalence was 20%, 19%, 22% and 21% in each survey, respectively. There was a significant improvement in scores for all three assessment methods post-intervention (p≤0.001). The intervention was associated with a small but significant increase in MRSA prevalence (p=0.023). MRSA colonisation was associated with previous and subsequent MRSA infection but was not significantly associated with subsequent hospitalisation or mortality.

Conclusions

The intervention did not result in a decrease in the prevalence of MRSA colonisation in care home residents. Additional measures will be required to reduce endemic MRSA colonisation in care homes.

Article summary

Article focus

To assess the effectiveness of an educational intervention on the prevalence of MRSA in care homes for the older people.

Key messages

There was a high rate of MRSA colonisation in elderly residents of care homes during the study period.

The intervention improved the infection prevention knowledge and practice of staff working in care homes but did not reduce the prevalence of MRSA colonisation of residents.

MRSA colonisation was associated with previous and subsequent MRSA infection but was not significantly associated with subsequent hospitalisation or mortality.

Additional measures are required to reduce endemic MRSA colonisation in care homes.

Strengths and limitations of this study

This is a large prospective study, including 65 homes and 2492 residents. MRSA prevalence was monitored over a 28-month period.

The intervention was plausible, unlikely to be harmful, and the assessments of the intervention were reasonable.

A significant improvement was seen in scores for all three intervention assessment methods; however, the intervention was associated with a small but significant increase in MRSA prevalence.

It was not possible to identify or control for the factors responsible for the increase in MRSA prevalence following the intervention.

Introduction

Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a significant cause of mortality and morbidity in both healthcare and community settings.1 2 Numerous surveillance schemes,3 4 recommendations5 6 and guidelines7 8 have been developed with the aim of reducing levels of MRSA infection associated with healthcare. In the UK, mandatory surveillance of cases of MRSA bacteraemia was introduced in all acute NHS Trusts in England in 2001.3 Recently, levels of MRSA bacteraemia in hospitals have been decreasing markedly.9

The elderly population living in care homes often require frequent contact with healthcare. This situation, known as the ‘revolving door’ syndrome,10 when residents are admitted to hospital and then discharged back into a care home, means that care home residents are more likely to be carriers of MRSA. Small studies in the UK during the 1990s identified levels of MRSA colonisation in care home residents between 0.8% and 17%.11–13 More recently, our group14 and Baldwin et al15 reported that MRSA colonisation levels among residents in care homes in the UK were >20%. MRSA prevalence rates of >36% have been reported in long-term care facilities in France and the USA.16 17 There is a paucity of large-scale longitudinal studies monitoring the occurrence of MRSA in the care home setting14 15 and the assessment of health outcomes of residents colonised with MRSA are not commonly reported.

Guidance for infection control in care homes was issued by the Department of Health in 2006.8 These guidelines comprised recommendations rather than statutory requirements and were not specific for the control of MRSA. In a recent Care Quality Commission (CQC) survey, however, 25% of participating care homes were not using the Department of Health guidance,8 including specific requirements that all staff should receive training in infection prevention and control.10 Most evidence for the effectiveness of infection control strategies has been generated in the acute healthcare setting.7 18 Although some infection prevention recommendations designed for acute healthcare may be applicable to other settings,7 successful translation to the care home environment cannot be assumed.10 During compilation of a Cochrane review of infection control strategies for preventing MRSA transmission in nursing homes, no studies met the systematic selection criteria.18 Robust data referring to strategies for preventing MRSA transmission in care homes are lacking, and studies are needed to test infection prevention interventions that are deliverable in the care home setting.18

The objectives of this study were to determine prospectively the prevalence and risk factors for MRSA colonisation in a large sample of elderly residents of care homes in Leeds Primary Care Trust (PCT) and to determine whether training and education of care home staff in the area of infection prevention, in particular hand hygiene, can minimise the risk of MRSA transmission. Health outcomes (rates of subsequent hospitalisation, infection and mortality) of residents according to MRSA colonisation were also examined.

Methods

Setting

According to the Care Standards Act (2000), a care home is defined as ‘any home that provides accommodation, together with nursing or personal care, for any person who is, or has been ill, or is disabled or infirm’.19 In the UK, all homes that meet the definition of a care home are registered with the CQC, formerly known as the Commission for Social Care Inspection.20 Care homes may be owned by the local authority or by independent providers. A care home without nursing capability was defined as a home that provided residents with accommodation, social and personal care. A home with nursing capability was defined as a home that employed registered nurses and provided nursing care in addition to accommodation, social and personal care to residents. Care homes with nursing capability were listed on the CQC register as a nursing home. All care homes, with 20 or more beds, registered in Leeds, UK, were eligible to take part in the study, excluding those that provided care for people with mental, physical or mental handicap. Ninety of the 186 registered care homes met the study criteria and were invited to participate. Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust (LTHT) was the main acute care provider for all the care homes included in the study.

Data collection

Each participating care home was given a unique identifying number and was anonymised to laboratory staff. Details such as home owner, number of beds and whether or not a home had nursing capability were recorded for each home. Each resident who was considered to be eligible to participate by the care home staff was verbally given information about the nature of the study. In the first instance, written consent was obtained, followed by verbal consent if the resident agreed to participate in subsequent surveys. The sampling process was anonymised, with no specific infection prevention interventions being initiated on the identification of a resident who was colonised. At each survey, the total number of residents present in the home and the number of residents able to consent was collected by age and sex category. Data pertaining to the age, sex and presence of an invasive device were collected per participant, per survey.

Once the collection of swabs had been completed, further data were collected. The Microbiology Laboratory Information Management System was used to determine whether each resident had a record of clinical samples being sent for microbiological investigation and whether or not MRSA had been isolated before or after each survey. For the purposes of this study, MRSA infection was defined as a record of MRSA isolated from any invasive sample type (ie, blood culture, tissue, bone, bronchoalveolar lavage) or MRSA isolated as pure culture from a non-invasive sample type (ie, swab, sputum, urine). MRSA colonisation was defined as a record of MRSA isolated from a urine sample collected via a catheter or MRSA isolated from a non-invasive sample type in the presence of other bacteria. Data regarding contact with healthcare facilities were collected using the Patient Administration System (PAS) for LTHT. This included the total number of hospital days spent in LTHT during the 12 months before a screening swab was collected and the number of hospital admissions prior to this period. Any attendance at outpatient clinics was also recorded. All-cause mortality data were collected both from PAS and from a database held by Leeds Primary Care Trust.

Study design

This study was a controlled before and after intervention study and followed a stepped wedge design (table 1).21 After an initial MRSA prevalence survey, care homes were randomly allocated into three groups. Random allocation was stratified by number of beds and baseline MRSA prevalence. Implementation of staff training and education intervention was dependent on the group to which the home had been allocated. Homes in group 1 received the intervention between January and October 2007, in group 2 between November 2007 and February 2008 and in group 3 between July and September 2008. Scores for audits of hand hygiene facilities, staff hand hygiene observations and an educational questionnaire were collected before and after the intervention.

Table 1.

Intervention schedules for stepped wedge design; ‘pre’ represents a pre-intervention survey and ‘post’ represents surveys occurring post-intervention

| Group | Survey/period of collection |

|||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| November to December 2006 | October to November 2007 | May to June 2008 | January to February 2009 | |

| 1 | Pre | Post | Post | Post |

| 2 | Pre | Pre | Post | Post |

| 3 | Pre | Pre | Pre | Post |

Intervention

An intervention based on staff training and education on the topic of infection prevention and effective hand hygiene was used to assess the effect on MRSA prevalence. The intervention consisted of a structured session of education, combined with two audits that assessed hand hygiene practice and facilities in the care home. Scores for the educational questionnaire and for audit of hand hygiene facilities and staff hand hygiene observations were collected before and after the training session. Written feedback concerning the results of the audits that took place before the training session was returned to each home. Specific suggestions for improvement were included when necessary.

The education session, lead by an Infection Control Nurse employed by Leeds PCT, lasted approximately 45 min and was delivered using a Microsoft Office PowerPoint presentation with strictly controlled content. Topics included how and when to wash hands and barriers to effective hand washing. The use of alcohol gel and personal protective equipment were also included. A DVD outlining correct hand hygiene procedures was shown during the training. Attendees participated in a practical demonstration of good hand hygiene technique by using hand cream containing ultraviolet-responsive particles and a ultraviolet light box. A questionnaire comprising 12 short answer questions was completed, directly before (pre) and after (post) the educational session, by personnel who attended the training. Approximately 4 weeks after the training was completed, three members of staff were chosen at random to complete the same questionnaire; this is referred to as the extended-time questionnaire. The same materials and session format were used for all intervention groups. The study aimed to deliver the educational input to at least 80% of the whole-time equivalent staff.

An audit of the hand hygiene practice and facilities was carried out for each home at the beginning of the relevant intervention period, using an audit tool from the Infection Control Nurses Association.22 Issues such as staff education, compliance with requirements relating to uniform policy and provision of liquid soap and paper towels were assessed. The same audit was carried out after written feedback had been given to the home. The Lewisham hand hygiene assessment tool23 was used to perform observational audits of hand hygiene practice before and, a minimum of 4 weeks, after the educational input for each intervention group. During each of these audits, three care home staff members, selected at random, were shadowed for a period of 20 min each. A comparison between the number of times hand decontamination occurred versus the number of hand washing opportunities arising was determined to give a percentage figure for compliance.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Stata data analysis and statistical software (StataCorp). χ2 Tests were used to compare resident and care home characteristics. Descriptive statistics were used to compare home characteristics between the three groups into which homes were allocated and to compare those homes participating in the study to those not consenting to take part. χ2 Tests were used to compare proportions, t tests for comparing continuous variables between two groups and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for comparing continuous data between more than two groups. Analytical approaches used in stepped wedge designs are susceptible to separate time trends within subgroups21; therefore, the presence of a significant time trend within subgroups of care homes and residents was investigated. The impact of the intervention was then investigated using a random effects logistic regression model controlling for resident characteristics and subgroup by time trend interactions. A χ2 test was used to compared hand hygiene proportions and a t test to compare educational scores. Scores from the audit of hand hygiene facilities were not normally distributed, and a Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for comparison. To investigate whether being identified with an infection was associated with prior MRSA carriage, survival analysis was performed using a Cox proportional hazards model. Residents that had a record of an MRSA infection prior to entering the study were excluded from this analysis. The analysis investigated the time from the resident entering the survey to the time of identification of an MRSA infection or until 9 August 2009. A random effects logistic regression model was used to assess whether mortality was associated with prior MRSA carriage. For all analyses, statistical significance was defined as p<0.05.

Microbiological methods

Amies' Transport swabs (Barloworld Scientific, Stone, Staffordshire, UK) were used to sample the anterior nares of consenting residents during four periods: 16 November 2006 to 13 December 2006 (survey 1), 1 October 2007 to 12 November 2007 (survey 2), 1 May 2008 to 26 June 2008 (survey 3) and 5 January to 12 February 2009 (survey 4). Each swab was used to inoculate a single MRSA Select Agar plate (Bio-Rad, Marnes la Coquette, France), which was incubated for 18–24 h at 37°C. Bright fuchsia–pink colonies were considered presumptive MRSA. Presumptive MRSA colonies were confirmed to be S aureus by DNAse agar testing and positive agglutination reaction using the Pastorex Staph Plus Kit (Bio-Rad). Meticillin resistance was confirmed by breakpoint susceptibility testing using Iso-Sensitest agar (Oxoid, Hampshire, UK) supplemented with 4, 8 and 12 mg/l methicillin, respectively (Medical Wire and Equipment Co. Ltd., Wiltshire, UK) or 4 mg/l cefoxitin (Mast Diagnostics, Merseyside, UK). Isolates that had an equivocal meticillin susceptibility result by breakpoint method were analysed further using the Mastalex MRSA Kit (MAST Diagnostics, Merseyside, UK). Meticillin-susceptible S aureus strain NCTC 6571 and MRSA strain NCTC 10442 were used as control organisms.

Results

Participating care homes

Of the 90 homes that were invited, 68 homes participated in the first part of the study. There was no significant difference in the homes taking part and those that refused in terms of the number of residents (p=0.15, t test), the proportion with nursing capability (p=0.62, χ2) or the proportion that were owned by the local authority (p=0.18, χ2). After the initial survey, the 68 homes that participated were randomly allocated into three groups. The number of homes that were in each group and their characteristics are shown in table 2.

Table 2.

Home characteristics according to intervention group

| Groups |

|||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Total homes (n) | 28 | 18 | 22 |

| Mean number of places per home (n) | 44 | 39 | 42 |

| Homes with nursing capability (n) | 14 | 8 | 10 |

| Local authority homes (n) | 8 | 1 | 6 |

There was no significant difference between homes allocated to different intervention groups with respect to the number of homes that provided nursing care (p=0.9, χ2), the mean number of beds per home (p=0.6, ANOVA) and the owner of the home (p=0.12, χ2). There were no significant differences in mean age (p=0.9, ANOVA), sex distribution (p=0.4, χ2) or overall number of residents (p=0.43, t test) between the three intervention groups; however, there were fewer residents in homes owned by the local authority in group 2. Following the first survey, two homes withdrew from the study leaving 66 homes in the second survey. A further home withdrew following survey 2 leaving 65 homes in surveys 3 and 4. The following analyses report data from those homes that participated in all four surveys.

The 65 homes that participated in all four surveys had 2772 beds. Fourteen homes were operated by the local authority, none of which had nursing capability (n=463 beds, range 20–40, mean 33). Fifty-one homes were owned by independent providers (n=2309 beds, range 20–180, mean 44); 31 homes (n=1648 beds) had nursing capability. Homes with nursing capability comprised 48% (n=30) of the homes in this study and housed 59% (n=1621) of the beds.

Participating residents and swabs collected

In total, 4327 swabs were collected, 1210 from survey 1, 1067 from survey 2, 1023 from survey 3 and 1027 from survey 4. Two swabs were removed from survey 4 due to participant duplication (n=1) and incomplete data, leaving 4325 swabs suitable for analysis. The number of swabs collected from individual care homes during any survey ranged from 5 to 93. On average, 46% of residents that were present in homes at the time of a survey were swabbed (ie, able to provide consent and available for swabbing).

The study included 2492 residents. The majority (n=1405, 56%) of residents participated in a single survey, 550 (22%) participated in two surveys, 328 (13%) in three surveys and 209 (8%) participated in all four surveys. The majority (n=1404) of residents had been admitted to hospital within the 12 months before being included in the study. Of those that did not have a record of hospital admission within 12 months of being sampled, 664 had a record of previous hospital admission according to LTHT PAS. There were 424 (17%) residents that had no record of hospital admission to LTHT; however, 154 of these had a record of contact with outpatient clinics. There were 270 residents that did not have any record of contact with healthcare; of these, 18% were found to be MRSA positive in at least one survey. The corresponding proportion for those who had had healthcare contact was 28% (p<0.001).

Staff knowledge and behaviour

There were significant improvements in the mean scores for staff knowledge following the intervention, 71% scores after education versus 43% before education (p<0.001, t test). The mean knowledge score achieved at the extended-time questionnaire was 57% (vs baseline p<0.001, t test). There were significant improvements in the mean scores following the intervention for the audit of hand hygiene facilities (85% post-intervention vs 69% pre-intervention, p<0.001, Wilcoxon-signed rank test) and observations of hand hygiene (82% of 455 opportunities after the intervention versus 58% of 568 opportunities before, p<0.001, χ2 test).

MRSA colonisation

A total of 888 swabs (21%) of anterior nares were MRSA positive; this comprised 238 participants in survey 1 (20%), 204 in survey 2 (19%), 228 in survey 3 (22%) and 218 in survey 4 (21%). The prevalence of MRSA colonisation in residents within individual homes ranged from 0% to 60%. One home, a privately owned care home without nursing capability (n=24 beds), with 21 participants, did not have any residents with nasal colonisation with MRSA identified in any of the four surveys. There was no significant difference in prevalence of MRSA between surveys (p=0.28, χ2), and there was no significant trend in MRSA prevalence overall (p=0.15, ANOVA) across the four surveys. When other factors were controlled for (age, sex, hospital admissions, invasive devices), however, a significant increase in MRSA colonisation across the four surveys was identified (OR=1.08, p=0.031, logistic regression). In order to identify factors associated with the increasing trend, subgroup analyses (homes with nursing capability, privately owned homes or large homes (>35 beds)) were performed. The increase in MRSA prevalence remained significant in homes with nursing capability (OR=1.61, 95% CI 1.15 to 2.26, p=0.006, logistic regression) and for residents in the >90-year age group (OR=1.14, p=0.044, logistic regression). Both trends were taken into account during multivariate analysis.

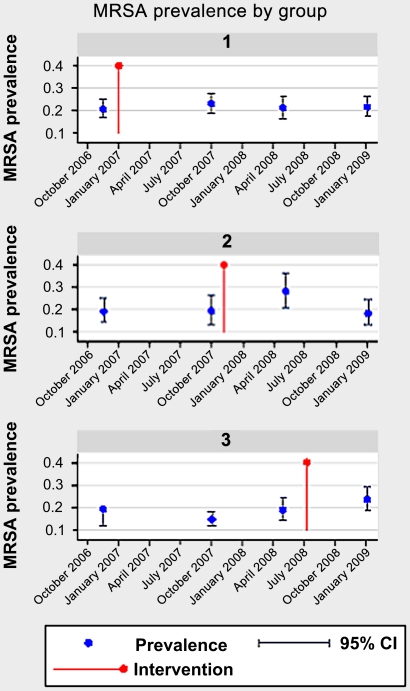

Multivariate analysis of risk factors for MRSA colonisation in residents showed that the intervention was associated with a small but significant increase in prevalence of MRSA (p=0.02, logistic regression) (table 3). Overall, MRSA prevalence prior to the intervention was 18.6%, which increased to 22.4% after the intervention. When analysed according to group, there was a significant difference between MRSA prevalence before and after the intervention in groups 2 (p=0.04, χ2) and 3 (p=0.02, χ2) but not in group 1 (p=0.44, χ2) (figure 1). The significant increase in prevalence occurred in the survey directly after the intervention but was not sustained in the group that had follow-up (figure 1). The following factors were also significantly associated with MRSA colonisation: the number of hospital admissions in the last 12 months, the total number of days a participant spent in hospital in the 12 months before sampling, male sex and having a record of an MRSA infection prior to entering the study (table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression of risk factors for colonisation with meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) among 2492 residents of care homes in Leeds, UK, according to care home capability

| Risk factor | Comparison group | Overall |

Care home |

||||

| Without nursing capability |

With nursing capability |

||||||

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | ||

| After intervention | No intervention | 1.36 (1.04 to 1.79) | 0.02 | 1.61 (1.03 to 2.52) | 0.034 | 1.26 (0.91 to 1.75) | 0.159 |

| No. of hospital admissions in the last 12 months | – | 1.18 (1.11 to 1.26) | <0.001 | 1.23 (1.11 to 1.36) | <0.001 | 1.14 (1.05 to 1.24) | 0.001 |

| No. of hospital admission days in the last 12 months | – | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 0.001 | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.01) | 0.046 | 1.00 (1.00 to 1.00) | 0.006 |

| Presence of an invasive device | Absence of invasive device | 2.36 (1.70 to 3.29) | <0.001 | 1.81 (0.86 to 3.82 | 0.116 | 2.46 (1.70 to 3.56) | <0.001 |

| Record of MRSA infection prior to study | No previous record | 2.12 (1.49 to 3.02) | <0.001 | 3.73 (1.78 to 7.82) | <0.001 | 1.78 (1.19 to 2.65) | 0.005 |

| Age 80–89 years | <80 years | 1.13 (0.92 to 1.39) | 0.24 | 1.14 (0.80 to 1.64) | 0.454 | 1.15 (0.90 to 1.48) | 0.246 |

| Age 90+ years | <80 years | 1.29 (0.94 to 1.78) | 0.11 | 1.54 (0.91 to 2.6) | 0.101 | 1.13 (0.75 to 1.7) | 0.537 |

| Male | Female | 1.48 (1.24 to 1.78) | <0.001 | 1.37 (1.0 to 1.87) | 0.042 | 1.55 (1.25 to 1.93) | <0.001 |

Figure 1.

Changes in meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) prevalence by intervention group per survey, before and after the intervention.

To investigate the increase in MRSA prevalence occurring after the intervention, care homes with and without nursing capability were analysed separately with controls (table 3). This analysis showed that the intervention was no longer associated with an increase in MRSA prevalence in homes with nursing capability (p=0.159, logistic regression); however, in care homes without nursing capability, the intervention remained significantly associated with an increase in MRSA prevalence (p=0.034, logistic regression). When the same analysis was performed only including participants who were present in at least two surveys (n=1087), the intervention remained associated with an increase in MRSA prevalence in both care homes with nursing capability (OR=2.07, 95% CI 1.22 to 3.52, p=0.007, logistic regression) and those without (OR=2.55, 95% CI 1.3 to 4.97, p=0.006, logistic regression).

Outcome of MRSA colonisation

Residents were followed for a median of 21 months to determine MRSA infection and survival outcomes. The length of follow-up varied significantly according to the survey in which the resident participated; residents in the first survey had a possible follow-up of 33 months compared with those in the last survey, who had possible follow-up of 6 months. Hospital admission data in the period 12 months after the date of colonisation were collected for residents that participated in survey 1 (n=1210). The RR for hospitalisation within 12 months of the date of colonisation was 1.27 (p>0.05). Subsequent infection with MRSA was significantly associated with prior MRSA colonisation when other factors were controlled for (OR=2.5, 95% CI 1.2 to 5.24, p=0.014, Cox proportional hazards model) (table 4). Of the 2492 residents included in the study, 90 residents were recorded as having an MRSA infection prior to entering the study, leaving 2442 suitable for further analysis. The majority (n=1800) of residents were not colonised with MRSA and had no record of an MRSA infection. There were 612 residents who were colonised with MRSA but had no record of MRSA infection, 16 residents had no MRSA colonisation and had a subsequent record of an MRSA infection and 14 residents were identified with colonisation and had subsequently developed an MRSA infection. Eight residents had a record of MRSA bacteraemia. Two per cent of residents colonised with MRSA had a record of MRSA infection subsequent to a survey compared with 0.9% for those residents without MRSA colonisation (p=0.008, χ2). Death was recorded for 897 of the 2492 residents that participated. Colonisation with MRSA was not significantly associated with mortality (OR=1.16, 95% CI 0.95 to 1.41, p=1.32, logistic regression); however, mortality was significantly associated with advanced age, male sex, the presence of an invasive device and the number of hospital admissions within 12 months (table 4).

Table 4.

(A) Proportional hazards model of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection taken from the time of entering the study to either MRSA infection or 9 August 2009, whichever occurred first, and (B) logistic regression model of mortality associated with prior MRSA carriage

| Risk factor | (A) MRSA infection |

(B) Mortality |

||

| HR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| MRSA colonisation during study | 2.51 (1.2 to 5.24) | 0.014 | 1.16 (0.95 to 1.41) | 0.132 |

| Age | 1.00 (0.96 to 1.05) | 0.728 | 1.04 (1.03 to 1.05) | <0.001 |

| Male | 1.41 (0.65 to 3.08) | 0.377 | 1.39 (1.14 to 1.69) | 0.001 |

| Presence of an invasive device | 0.67 (0.09 to 5.02) | 0.701 | 5.45 (3.32 to 8.95) | <0.001 |

| No. of hospital admissions in the previous 12 months | 1.11 (0.92 to 1.34) | 0.244 | 1.06 (1.00 to 1.12) | 0.038 |

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the largest prospective study that has monitored the level of nasal colonisation of MRSA in elderly residents of care homes in the UK. Sixty-five homes and 2492 residents participated in the study, which took place over a 28-month period (November 2006 to February 2009). The study included a large proportion of care homes in the area served by Leeds Primary Care Trust, including homes of different sizes (n=20–180 beds), homes owned by the local authority and by independent providers and homes with and without nursing capability. In total, 888 MRSA isolates were identified from 4325 nasal swabs during the periods of screening stated. The mean level of MRSA colonisation was 20% (95% CI 18% to 23%), which was higher than levels recorded during the 1990s but comparable to those reported recently (95% CI 22%–23%).14 17 Interestingly, a recent survey of 748 residents in 51 care homes in Gloucestershire and Bristol found that only 7.9% residents were positive for MRSA by nasal screening, indicating marked geographical variation in MRSA prevalence in care homes.24

The health outcomes of residents are not commonly included in studies of MRSA prevalence in the care home.17 25 26 The findings of the present study support the hypothesis that although MRSA infections in the care home setting are infrequent, colonised residents have an increased risk of developing an infection.15 27 MRSA colonisation was associated with previous and subsequent MRSA infection; residents colonised with MRSA were two and a half times more likely to develop an MRSA infection than non-carriers. Notably, however, MRSA colonisation was not significantly associated with mortality in a logistic regression model, a finding that has been reported by others, albeit in a lower prevalence setting.28

The intervention applied in the present study was intended to improve awareness of good practice and knowledge of infection control in care homes, with an emphasis on hand hygiene. The present study assessed the infection prevention knowledge of over 1000 members of staff and the infection prevention practice of >300 individuals. The stepped wedge design allowed measurement of MRSA prevalence before the intervention, directly after the intervention and further follow-up in two of the three study groups. Participating residents and staff in each group of homes acted as controls for each other. Three established methods were used to measure staff knowledge and behaviour following the intervention and scores improved after the intervention for all three assessments.

Overall, no significant difference in MRSA prevalence was identified during the survey periods. Directly following the intervention, however, there was a significant increase in MRSA prevalence, although this returned to baseline levels in one group that had follow-up. Stepped wedge designs are particularly susceptible to trends within subgroups, but when the subgroups were adjusted for linear trends, the increase in MRSA prevalence after the intervention remained significant. It is possible that other confounding factors resulted in a non-linear trend in MRSA prevalence in certain homes. It has not been possible to identify or control for these factors. MRSA infections are unlikely to be independent events and a cluster of MRSA cases may explain temporary increases in prevalence following the intervention in some homes. LTHT was the main acute care provider for all the homes in the study. The small increase in MRSA prevalence following the intervention is unlikely to relate to the extent of MRSA infection in LTHT as during the period of the study, there was a decreasing trend in the MRSA bacteraemia rates reported by LTHT.3

Other studies have used a similar intervention strategy in care homes.29–31 A study based in Taiwan introduced a programme of hand hygiene training into three care homes and identified significant improvements in scores for staff knowledge and behaviour after the training, difference between hand hygiene knowledge pre- and post-intervention, p<0.001, difference between hand hygiene observations pre- and post-intervention, p=0.001.30 Although no direct measure of microbiological outcome was included, rates of infection based on the total number of urinary tract infections lower respiratory infections and rates of influenza recorded by each facility were significantly lower following the intervention (1.52%) compared with rates recorded for two periods before the intervention: December 2004 to February 2005 (1.74%) and June to August 2005 (2.04%) (p<0.001).

Around the same time as the present study, Baldwin et al29 implemented an infection control education and training programme in nursing homes in the Belfast area of Northern Ireland. The study screened 793 residents and 338 members of staff for MRSA colonisation. The education programme, occurring at baseline and at 3 and 6 months, consisted of multiple training sessions for staff. An existing member of staff in each intervention home was assigned the role of infection control link worker, the role of which was to reinforce good infection control practice in the home. Practice was observed and recorded, with feedback, for an audit of 10 specified infection control standards involving the following subject areas: cleanliness, decontamination (hand and environment), waste management, personal protective equipment and the management of wounds, urinary catheters and enteral feeding. Using a cluster randomised controlled study design, audit scores and MRSA colonisation of residents and staff were compared for homes in the intervention group (n=16) with those homes in the control group (n=16); homes in the control group did not receive training or feedback. While scores for the infection control audits significantly improved in eight of the 10 standards (82% vs 64% in intervention and control homes, respectively, p<0.0001), levels of MRSA colonisation did not change over the 12-month study period in either residents or staff.

In contrast, Gopal et al31 evaluated whether enhanced infection control support in nursing homes had an impact on improving infection control practice. The intervention included extensive support from a dedicated infection control team, including an infection control nurse, infection control nurse specialist and an infection control doctor. Twelve homes were included in the study and were divided into two groups of six, an intervention group and a control group, based on the number of residents. The study found no statistical difference between the control group and the group of homes that received the intervention at baseline and final assessment for hand hygiene facilities (p=0.69), environmental cleanliness (p=0.43) and disposal of clinical waste (p=0.96). There was no microbiological investigation included in this evaluation.

In principle, the intervention applied in the present study was plausible and unlikely to be harmful. The assessments were reasonable, albeit focused on short-term effects; however, the following limitations of the study must be acknowledged. It is likely that the prevalence reported here is an underestimation of the true level of MRSA colonisation because of the use of nasal screening alone. To achieve a high level of sensitivity of detection (>90%) of MRSA carriers, multiple sites (eg, axilla, groin, nose and throat) need to be screened.32 33 Screening urethral catheters, legs ulcers and pressure sores would have increased the sensitivity of MRSA detection and may have provided further information regarding the infection status of the resident. Although pooling swabs from multiple sites could have been done at the same cost, screening the anterior nares as a single site using chromagar as a growth medium was a compromise, taking into account the difficulties of obtaining consent and practical issues associated with more extensive sampling of a predominantly frail, elderly population and the need for a cost-effective approach. Participation of residents was voluntary, and on average, 46% of the residents were tested for MRSA colonisation. Reasons for non-participation of residents were not collected; care homes for people with dementia were not specifically excluded from the study, but residents with dementia were excluded. It is acknowledged that residents who were not considered eligible to participate due to their level of dependency may be at a greater risk of MRSA colonisation.

Other potentially informative data were not collected. For example, the type of room available per resident (ie, single, shared, en-suite), local cleaning policies (routine and incident related), laundry provision and the uniform policy of the home would have provided a fuller description of the care home setting. Staff turnover in each care home was assessed at baseline, but more frequent data collection may have enabled a better assessment of the effect of the intervention. We did not collect information about length of stay of each resident, movement of individuals between homes, which we understand is uncommon, the number of admissions per home and sources of admission (ie, own home, hospital, other care home).

The study aimed to deliver educational input to at least 80% whole-time equivalent staff, which was achieved in 32% of the homes. Resources were available to provide each home with a maximum of three educational sessions, although exceptions were made for those homes with >100 beds. Availability of care home staff due to work demands or sickness and closure of homes due to outbreaks of norovirus were reasons for not achieving the educational target in some homes. Such issues highlight the operational barriers to infection prevention measures, especially those that require behavioural change.

Other challenges to a study of this design include the requirement for ethical approval, which may result in the inability to screen residents who cannot give consent, and the need to maintain the anonymity of participating residents and staff. Limited resources, home ownership, lack of isolation facilities, the high throughput of employees and a high resident-to-carer ratio may influence the effectiveness of infection control strategies in care homes.18 34 In the absence of mandatory requirements relating to infection control in care homes, it may be difficult to implement infection prevention strategies in the primary care setting.

Although observational methods of assessing hand hygiene compliance are considered the gold standard,35 increased productivity due to observation, known as the Hawthorne effect, must be considered.36 37 Despite long-term microbiological follow-up (8–25 months), the duration of follow-up with regard to staff knowledge and behaviour remained short (approximately 4 weeks). While the anonymous design of the present study kept assessment of the intervention informal, it did not enable the long-term follow-up of knowledge and practice in individual staff.

The intervention applied in the present study focused on a particular area of infection prevention, that of hand hygiene, skin care and personal protective equipment. Hand hygiene is considered to be an educational priority; however, there is little evidence to suggest that improvements in hand hygiene alone result in a significant reduction in MRSA infection or colonisation.38 Clearly, hand hygiene may still be beneficial, and without emphasis on such practice, it is plausible that transmission of MRSA and other pathogens would increase. Reinforcement of message and/or use cognitive behavioural theory could be explored to optimise hand hygiene and thus its effectiveness. Additional educational topics may include risk factors for infection and how to identify residents at risk, care of wounds and invasive devices and education about the judicious use of antibiotics.39 Implementation of an intervention in a setting such as that of the care home, which experiences a high level of change, in terms of employee and resident throughput, cannot be expected to last long term without regular input. A single session of education per staff member is unlikely to make a large difference to long-term practice. Alternative training and education strategies may include more frequent educational sessions, with additional learning resources, such as e-learning. Others have reported, however, that the introduction of multiple training sessions did not result in a decrease in MRSA prevalence,29 and cares homes that had access to extensive infection control support failed to show improvements in audit scores.31

The use of interventions that focus on screening and decolonisation of residents and/or staff may reduce MRSA prevalence in care homes. Given the difficulty of achieving MRSA decolonisation in individuals with multiple risk factors for persistence, this would be a considerable undertaking and may risk resistance selection. Control of risk factors for MRSA colonisation, such as improved management of wounds and invasive devices, may be beneficial.39 Evaluation would be required to assess the cost versus benefit of interventions involving screening and decolonisation in the care home setting, along with consideration about the source of funding if such approaches were to be recommended.40 41 Given the large recent and continuing decreases in incidence of invasive MRSA infection in England,9 it remains possible that control measures in the secondary care setting will lead to reduced MRSA carriage in care home residents.

Conclusions

These results reinforce previous reports of high MRSA colonisation rates in elderly residents of care homes. The intervention applied in the present study improved staff practice and knowledge but did not reduce MRSA prevalence in residents. These data provide an important baseline for future surveillance of MRSA in the care home setting. Further work is needed regarding screening, decolonisation and re-entry to the care home and continued surveillance is needed to understand the interaction between MRSA in care homes and hospitals. Clear policy decisions need to be made about how to manage with the burden of MRSA colonisation in care home residents. The high burden of MRSA in residents has implications for other healthcare institutions who manage these individuals. Admission arrangements (isolation/screening, etc) of care home residents may need to be adjusted to take account the risk of MRSA colonisation for individuals. Reducing MRSA infection and possibly colonisation in hospital patients may in turn affect the prevalence of MRSA in care home residents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the residents and staff of all the participating care homes, the Infection Control Nurses at North East Leeds PCT, Richard Dixon (Information Manager at Leeds Primary Care Trust), Warren Fawley and the Infection Control laboratory staff at the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, James Riach for assistance with data entry and Dr John Heritage (University of Leeds) for advice and assistance in writing this manuscript.

Footnotes

To cite: Horner C, Wilcox M, Barr B, et al. The longitudinal prevalence of MRSA in care home residents and the effectiveness of improving infection prevention knowledge and practice on colonisation using a stepped wedge study design. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000423. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000423

Funding: This is an independent report commissioned and funded by the Policy Research Programme in the Department of Health. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Department.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study received approval from the East Leeds Research Ethics Committee: MREC reference number 06/Q1206/162.

Contributors: MW was the lead investigator and obtained funding for the study. All authors were involved in the study design and reviewed the draft of this report. CH coordinated the data management and drafted this report. GH and DT were integral to the setting up and management of the study. BB carried out the statistical analysis. PP was responsible for laboratory protocol development. DH carried out the data collection and the sampling of residents with assistance from other Infection Control Nurses, North East Leeds PCT. MW is the guarantor of the study. All authors have approved the final submitted version of the manuscript.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Gardam M. Is methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus an emerging community pathogen? A review of the literature. Can J Infect Dis 2000;11:202–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grundmann H, Aires-de-Sousa M, Boyce J, et al. Emergence and resurgence of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a public-health threat. Lancet 2006;368:874–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Health Protection Agency Mandatory Staphylococcus aureus Bacteraemia Surveillance Scheme. 2009. http://www.hpa.org.uk/HPA/Topics/InfectiousDiseases/InfectionsAZ/1191942169773/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hope R, Livermore DM, Brick G, et al. Non-susceptibility trends among staphylococci from bacteraemias in the UK and Ireland, 2001-06. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008;62(Suppl 2):ii65–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Department of Health Bloodborne MRSA Infection Rates to be Halved by 2008. 2004. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Pressreleases/DH_4093533 (accessed 6 Jan 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Department of Health Screening for Meticillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) Colonisation: A Strategy for NHS Trusts - A Summary of Best Practice, 2006. 2009. http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/@dh/@en/documents/digitalasset/dh_063187.pdf (accessed 6 Jan 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coia JE, Duckworth GJ, Edwards DI, et al. Guidelines for the control and prevention of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in healthcare facilities. J Hosp Infect 2006;63(Suppl 1):S1–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Department of Health Infection Control Guidance for Care Homes. London: England, Department of Health, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Health Protection Agency Quarterly Epidemiological Commentary: Mandatory MRSA Bacteraemia & Clostridium difficile Infection (October 2007 to December 2009). 2010. http://www.hpa.org.uk/web/HPAwebFile/HPAweb_C/1267551242367 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Care Quality Commission Working Together to Prevent and Control Infections. 2009. http://spic.co.uk/media/Infection%20Control/CQC%20document%20Working%20together.pdf (accessed 6 Jan 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cox RA, Bowie PE. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in nursing home residents: a prevalence study in Northamptonshire. J Hosp Infect 1999;43:115–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraise AP, Mitchell K, O'Brien SJ, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in nursing homes in a major UK city: an anonymized point prevalence survey. Epidemiol Infect 1997;118:1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Namnyak S, Adhami Z, Wilmore M, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: a questionnaire and microbiological survey of nursing and residential homes in Barking, Havering and Brentwood. J Infect 1998;36:67–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barr B, Wilcox MH, Brady A, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization among older residents of care homes in the United Kingdom. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007;28:853–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baldwin NS, Gilpin DF, Hughes CM, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in residents and staff in nursing homes in Northern Ireland. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009;57:620–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eveillard M, Charru P, Rufat P, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage in a long-term care facility: hypothesis about selection and transmission. Age Ageing 2008;37:294–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stone ND, Lewis DR, Lowery HK, et al. Importance of bacterial burden among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriers in a long-term care facility. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2008;29:143–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hughes CM, Smith MB, Tunney MM. Infection control strategies for preventing the transmission of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in nursing homes for older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(1):CD006354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Care Standards Act. 2000. London, England: The Stationery Office Limited, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Care Quality Commission. 2009. http://www.cqc.org.uk/ [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussey MA, Hughes JP. Design and analysis of stepped wedge cluster randomized trials. Contemp Clin Trials 2007;28:182–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Infection Control Nurses Association Audit Tool for Monitoring Infection Control Standards in Community Settings. 2005. http://www.ips.uk.net/template1.aspx?PageID=10&cid=19&category=Resources [Google Scholar]

- 23.NHS. Lewisham Hand Hygiene Audit Tool. 2006. http://www.clean-safe-care.nhs.uk/index.php?pid=5 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lasseter G, Charlett A, Lewis D, et al. Staphylococcus aureus carriage in care homes: identification of risk factors, including the role of dementia. Epidemiol Infect 2010;138:686–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mody L, Kauffman CA, Donabedian S, et al. Epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus colonization in nursing home residents. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:1368–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Baum H, Schmidt C, Svoboda D, et al. Risk factors for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus carriage in residents of German nursing homes. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2002;23:511–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bradley SF, Terpenning MS, Ramsey MA, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: colonization and infection in a long-term care facility. Ann Intern Med 1991;115:417–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Datta R, Huang SS. Risk of infection and death due to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in long-term carriers. Clin Infect Dis 2008;47:176–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Baldwin NS, Gilpin DF, Tunney MM, et al. Cluster randomised controlled trial of an infection control education and training intervention programme focusing on meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in nursing homes for older people. J Hosp Infect 2010;76:36–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang TT, Wu SC. Evaluation of a training programme on knowledge and compliance of nurse assistants' hand hygiene in nursing homes. J Hosp Infect 2008;68:164–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gopal RG, Jeanes A, Russell H, et al. Effectiveness of short-term, enhanced, infection control support in improving compliance with infection control guidelines and practice in nursing homes: a cluster randomized trial. Epidemiol Infect 2009;137:1465–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall C, Spelman D. Re: is throat screening necessary to detect methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus colonization in patients upon admission to an intensive care unit? J Clin Microbiol 2007;45:3855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lautenbach E, Nachamkin I, Hu B, et al. Surveillance cultures for detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: diagnostic yield of anatomic sites and comparison of provider- and patient-collected samples. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009;30:380–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larssen K, Jacobsen T, Bergh K, et al. Outbreak of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in two nursing homes in Central Norway. J Hosp Infect 2005;60:312–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moret L, Tequi B, Lombrail P. Should self-assessment methods be used to measure compliance with handwashing recommendations? A study carried out in a French university hospital. Am J Infect Control 2004;32:384–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kohli E, Ptak J, Smith R, et al. Variability in the Hawthorne effect with regard to hand hygiene performance in high- and low-performing inpatient care units. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009;30:222–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Holden JD. Hawthorne effects and research into professional practice. J Eval Clin Pract 2001;7:65–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Backman C, Zoutman DE, Marck PB. An integrative review of the current evidence on the relationship between hand hygiene interventions and the incidence of health care-associated infections. Am J Infect Control 2008;36:333–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manzur A, Gavalda L, Ruiz de GE, et al. Prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and factors associated with colonization among residents in community long-term-care facilities in Spain. Clin Microbiol Infect 2008;14:867–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Coates T, Bax R, Coates A. Nasal decolonization of Staphylococcus aureus with mupirocin: strengths, weaknesses and future prospects. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009;64:9–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dancer SJ. Considering the introduction of universal MRSA screening. J Hosp Infect 2008;69:315–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.