Abstract

Autophagy is a process of lysosomal degradation that was originally described as a cellular response to adapt to a lack of nutrients and to enable the elimination of damaged organelles. Autophagy is increasingly recognized as a process that is also involved in innate and adaptive immune responses against pathogens. Studies on the regulation of autophagy have uncovered components of the autophagic cascade that can be manipulated pharmacologically. Approaches to modulate autophagy may result in novel strategies for the treatment and prevention of various infections.

Keywords: bacteria, cytokine, lysosome, protozoa, vaccine, virus

Degradation of macromolecules is an essential aspect of cellular homeostasis. There are two major pathways for catabolism of macromolecules. One of them is dependent on the proteasome, a structure responsible for selective degradation of short-lived proteins. The second pathway, known as macroautophagy leads to lysosomal degradation of various macromolecules, including long-lived proteins and organelles [1]. Macroautophagy, usually referred to as autophagy, is a process conserved in all eukaryotes whereby a portion of the cytosol or whole organelles are encircled by an isolation membrane [2,3]. The expansion of this membrane results in the complete engulfment of the cytosol/organelle within a double-membrane vesicle called an autophagosome. This structure then fuses with late endosomes and lysosomes resulting in lysosomal degradation of its contents. Autophagy is a homeostatic mechanism that is present at basal levels in almost all cells. Autophagy is enhanced in various conditions of cellular stress, such as nutrient deprivation or accumulation of damaged organelles [2–5]. The breakdown of the contents of the auto-phagosome provides substrates necessary for cell survival during periods of starvation and can also serve the purpose of elimination of damaged organelles.

The role of autophagy extends beyond that of a catabolic process that enables cell survival during starvation and organelle turnover. Autophagy is now known to result in cell death when apoptosis is inhibited [6,7]. In addition, autophagy is important in development, aging and protection against cancer and various neurodegenerative, liver and muscle diseases [8–16]. There is also increasing evidence that links autophagy to mechanisms of resistance against pathogens [17].

Signaling pathways that regulate autophagy

The fact that autophagy is involved in the pathogenesis of numerous diseases has made this cellular response an attractive therapeutic target. Effective manipulation of autophagy requires understanding of the molecular events that govern this process. The pathways that control autophagy are complex and have been the subject of recent reviews [18,19]. Here, we will summarize some of the most salient aspects of the molecular pathways involved in autophagy.

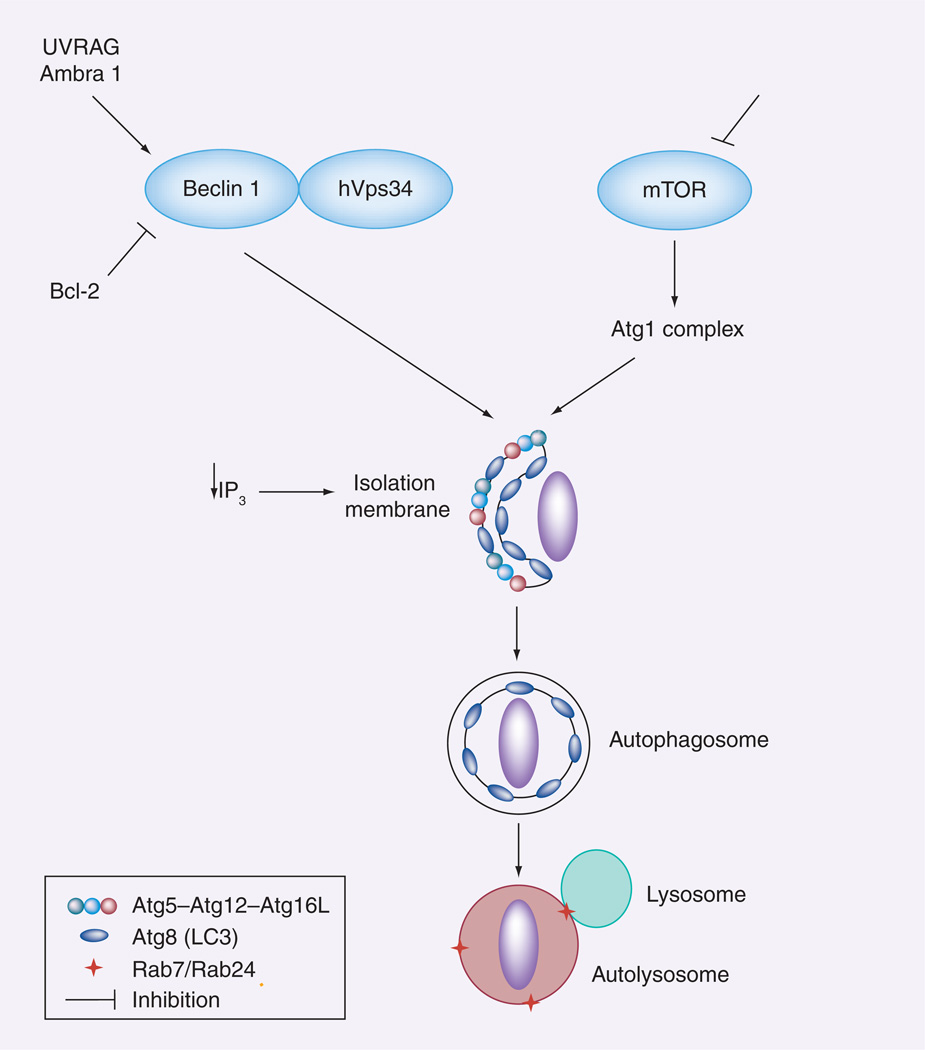

The serine/threonine kinase mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a key regulator of autophagy (Figure 1) [20]. Inhibition of mTOR stimulates autophagy, while enhanced mTOR activity impairs autophagy. Inhibition of mTOR with resulting enhancement of autophagy is typically accomplished experimentally by treating cells with rapamycin [20]. Downstream of mTOR lies a group of autophagy-related proteins (Atgs) [21–25]. Most Atgs are highly conserved from yeast to humans. In yeast, the Atg1 kinase lies downstream of the target of rapamycin and regulates the formation of autophagosomes [26,27]. The role on autophagy of mammalian homologs of Atg1 [28] is not well understood.

Figure 1. Regulation of autophagy.

Autophagy is enhanced by inhibition of mTOR activity. Elongation of the isolation membrane or phagophore is dependent on the Atg12 and LC3 (Atg8) cascades. As a result, this structure expands and wraps a portion of cytoplasm or an organelle forming the autophagosome. The Beclin 1/hVps34 complex is also key for autophagosome biogenesis. Formation of this complex is impaired by Bcl-2 and stimulated by UVRAG as well as by Ambra 1. The autophagosome fuses with the lysosome resulting in degradation of its contents. Autophagy can also be stimulated by a decrease in IP3 levels.

Ambra: Activating molecule in Beclin 1-regulated autophagy; Atg: Autophagy-related protein; IP3: Inositol triphosphate; mTOR: Mammalian target of rapamycin; UVRAG: Ultraviolet radiation resistance-associated gene.

Atg6 is another central regulator of autophagy. Studies performed in yeasts revealed that Atg6 is essential for the formation of the isolation membrane by promoting recruitment of other Atgs to this structure [27]. The mammalian homolog of Atg6 is usually referred to as Beclin 1 (Figure 1) [29]. Beclin 1 forms a complex with other proteins, notably class III phosphoinositol 3 kinase (PI3K; also known as hVps34) [30]. Beclin 1 promotes autophagy [9,31,32], a process that requires interaction between Beclin 1 and hVps34 [33,34]. The ability of Beclin 1 to associate with hVps34 is regulated by other components of the multiprotein complex. Ultraviolet radiation resistance-associated gene and activating molecule in Beclin 1-regulated autophagy (Ambra 1) bind to Beclin 1 and increase the interaction of Beclin 1 to hVps34, thus stimulating autophagy [35,36]. By contrast, binding of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 to Beclin 1 impairs the interaction between Beclin 1 and hVps34, resulting in inhibition of autophagy [37].

The elongation of the isolation membrane is dependent on recruitment of other Atg proteins. These proteins act as two ubiquitin-like conjugation systems: the Atg12 and LC3 (Atg8) cascades (Figure 1) [21–25]. Atg12 is covalently conjugated to Atg5. The Atg12–Atg5 conjugate associates with Atg16L forming an approximately 800-kDa protein complex [38]. Atg16L targets Atg12–Atg5 to the isolation membrane [38,39]. This process then promotes the conjugation of LC3 to the lipid phosphatidylethanolamide (PE) [22,39,40]. This process transforms the cytosolic LC3 (LC3 I) into autophagosome membrane-bound PE-conjugated LC3 (LC3 II). The pattern of expression of LC3 (punctate as opposed to diffuse) and the level of expression of LC3 II are classical markers of autophagy [41]. The autophagosome is formed by complete wrapping of intracellular contents by the isolation membrane. This is followed by interaction of the autophagosome with late endosomes/lysosomes, a process governed by the GTPases Rab7 and Rab24 [42–44]. Finally, activated hydrolytic enzymes present in the autolysosome degrade the cargo.

While mTOR and Beclin 1 are important regulators of autophagy, there is evidence that this process can occur independently of these molecules [19]. An example of mTOR-independent autophagy was uncovered by studies with inositol derivatives [45,46]. Free inositol and myo-inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) are endogenous inhibitors of autophagy (Figure 1) [45,46]. Lithium inhibits inositol monophosphatase causing reduction in free inositol and IP3 levels, and as a result promotes autophagy independently of mTOR [45]. In addition, ‘noncanonical’ Beclin 1-independent autophagy occurs in breast cancer cells treated with resveratrol [47], and reactive oxygen species can stimulate autophagy in a manner that is partially independent of Beclin 1 [48].

Many intracellular cascades have been reported to affect autophagy. A cascade that is relevant to the response to infectious organism consists of the interferon-inducible, dsRNA-dependent protein kinase R (PKR) and its downstream molecule the α-subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2α (eIF2α). These molecules are important components of the innate response against viruses [49]. They impair viral protein synthesis and viral replication. PKR and eIF2α have also been reported to promote starvation- and viral-induced autophagy [50].

Autophagy & antimicrobial activity

One of the areas of great interest is to decipher the role of autophagy as a mechanism of resistance against pathogens. Studies using various bacteria provided clear evidence that autophagy can act as a mechanism of pathogen clearance. Mycobacterium tuberculosis prevents phagolysosomal fusion as a strategy to persist within macrophages [51]. Stimulation of autophagy by starvation or by rapamycin resulted in co-localization of the autophagy protein LC3 with mycobacterial phagosomes, phagolysosomal fusion and killing of M. tuberculosis [52]. Streptococcus pyogenes that invades the cytosol of epithelial cells is targeted by autophagosome-like compartments leading to lysosomal degradation of the bacteria [53]. Studies in Atg5−/− cells revealed that the autophagic pathway causes transient bacterial clearance [53]. Similar to S. pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus can be subject to autophagic elimination [54]. Interestingly, strains of methicillin-resistant S. aureus escape autophagosomes [54]. Shigella flexneri normally avoids autophagy within epithelial cells [55]. The bacterial protein VirG normally binds to Atg5 and induces autophagy [55]. However, autophagy is prevented in wild-type bacteria because they secrete the virulent factor IcsB that prevents recognition of VirG by Atg5 [55]. Thus, S. flexneri that does not express IcsB becomes susceptible to killing via autophagy [55].

Autophagy has been reported to mediate the killing of other bacteria. Infection with Listeria monocytogenes induces autophagy [56–58]. Nonmotile actA mutant L. monocytogenes treated with chloramphenicol is targeted to autophagosomes in the cytosol of infected cells [56]. Studies using Atg5−/− mouse embryonal fibroblasts (MEF) revealed that autophagy limits bacterial growth only in the early stages of infection but not after the bacteria begin to multiply in the cytosol [57,58]. Autophagy is modulated by bacterial products. The expression of lysteriolysin O (LLO) is required for induction of autophagy in infected cells probably because LLO would allow bacterial escape from the vacuole into the cytosol leading to initial induction of autophagy [57,58]. Subsequently, the expression of bacterial phospholipases C and ActA would promote bacterial growth by inhibiting autophagy [57,58]. Autophagy can also limit the growth of Salmonella typhimurium [59]. S. typhimurium that escape the Salmonella-containing vacuole and reside in the cytosol are targeted by autophagosomes [59]. Similar to the studies with L. monocytogenes, work using Atg5−/− cells revealed that autophagy limited bacterial growth [59]. Autophagy also regulates the intracellular survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei [60]. A fraction of the bacteria colocalized with the autophagosome marker LC3 [60]. BopA, a bacterial type III secreted protein, inhibits autophagy [60]. However, pharmacologic stimulation of autophagy resulted in decreased bacterial survival [60]. Autophagy may be beneficial not only by leading to bacterial degradation but also by protecting cells against the effects of bacterial toxins. Indeed, autophagy protects cells against the effects of Vibrio cholerae cytolysin [61]. In contrast to the previous studies, autophagy may promote growth of certain bacteria. In the case of Legionella pneumophila, it has been proposed that the rapid induction of autophagy may lead to control of the pathogen [62].

Pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) can modulate autophagy and may promote pathogen clearance. The Toll-like receptor (TLR)-4 ligand lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induces autophagy, a process that requires the TLR-4 adaptor Toll-interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor-inducing IFN-β (TRIF) but not MyD88 [63]. This effect appears to be of functional relevance since LPS-induced autophagy enhanced co-localization of M. tuberculosis with autophagosomes [63]. However, in contrast to this study, another group failed to detect stimulation of autophagy in primary macrophages treated with LPS [39]. TLR signaling can link autophagy and phagocytosis [64]. TLR-2 and TLR-4 signaling at the time of phagocytosis induce recruitment of LC3 to the phagosomes although no conventional autophagosomes are detected [64]. This is associated with a more rapid and profound acidification of the phagosomes [64]. Similar to the previous study, it appears that TLR can enhance killing of a pathogen by stimulating autophagy molecules since the degradation of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is inhibited by knockdown of the autophagy gene Atg7 [64]. Subsequent studies revealed that TLR-3 and TLR-7 induce autophagy [65]. Moreover, stimulation of autophagy via TLR-7 promotes elimination of M. tuberculosis variant bovis bacille Calmette–Guérin (BCG) in a MyD88-dependent manner [65]. As discussed below, PRRs can induce autophagy and mediate in vivo resistance against L. monocytogenes in Drosophila [66]. A recent study identified a molecular link between TLR and autophagy. TLR signaling increases the interaction between MyD88 and TRIF (adaptor proteins downstream of TLR) and Beclin 1 [67]. MyD88 and TRIF diminish the binding of Beclin 1 to Bcl-2, an inhibitor of autophagy [67].

Autophagy can be involved in innate responses to bacteria that are not directly antimicrobial. Autophagosomes can co-localize with intracytoplasmic Francisella tularensis, although autophagy was not reported to mediate antimicrobial activity [68]. Of potential relevance to the immune response against F. tularensis, MHC class II has been detected in autophagosomes that contain the bacteria [69]. Macrophages, especially those that lack caspase-1, exhibit autophagosome formation associated with S. flexneri [70]. While autophagy did not mediate antibacterial activity, autophagy appeared to protect macrophages from Shigella-induced cell death [70].

Some of the initial evidence for a role of autophagy in the innate immunity to pathogens came from studies with viruses. Neuronal overexpression of Beclin 1 protected mice against lethal Sindbis virus encephalitis [29]. PKR- and eIF2α-dependent autophagy mediates degradation of herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) [71]. This virus produces ICP34.5, a neurovirulence factor that inhibits autophagy by reversal of PKR-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation and by antagonizing Beclin 1 [50,72]. Studies with HSV-1 are important because they also provided strong evidence for the in vivo role of autophagy in host protection. HSV-1 mutants that encode ICP34.5 proteins that are unable to bind to Beclin 1 become neuroattenuated in mice [72]. Neurovirulence of these mutants is restored in PKR-deficient mice [72]. Recent studies in Drosophila provided further support to the notion that autophagy can mediate in vivo protection against L. monocytogenes and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) [66,73]. Recognition of diaminopimelic acid-type peptidoglycan by the PRR peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRP)-LE is crucial for the induction of autophagy during L. monocytogenes infection [66]. Expression of mutant PGRP-LE or knockdown of PGRP-LE or Atg5 caused increased lethality in infected flies [66]. VSV infection induced autophagy in Drosophila cells and flies [73]. Autophagy appeared to be triggered by recognition of VSV glycoprotein G [73]. Importantly, autophagy mediated host protection since autophagy deficient flies were more susceptible to VSV [73].

Production of type I interferons by plasmacytoid dendritic cells is another aspect of innate immunity against virus that can be controlled by the autophagy protein Atg5. In the case of Sendai virus and VSV, Atg5 is required for delivery of ssRNA to TLR-7 present in the endosomal compartment [74]. This results in a strong type I interferon innate response to the viruses [74]. By contrast, another study reported that autophagy proteins can negatively regulate type I interferon production [75]. After infection with VSV, the Atg12–Atg5 conjugate inhibits type I interferon production by associating to retinoic acid-inducible gene I (RIG-I) and IFN-β promoter stimulator 1 (IPS-1) through the caspase recruitment domains [75]. Such inhibition of type I interferon production would promote viral replication.

An important question was whether autophagy not only functions as an innate mechanism for resistance against pathogens but whether it can be activated by adaptive immunity. Studies with M. tuberculosis indicated that this might be the case. IFN-γ is a known stimulator of autophagy and this cytokine causes fusion of phagosomes that contain M. tuberculosis with late endosomes/lysosomes [52,76]. Autophagy and killing of BCG are dependent on the immunity-related GTPase IGM1 [76]. The effects of IFN-γ on autophagy are inhibited by the Th2 cytokines IL-4 and IL-13 [77]. Based on these findings, it has been proposed that IFN-γ induces antimycobacterial activity through autophagy [52]. Studies using Toxoplasma gondii provided further proof that autophagy can be activated by adaptive immunity to induce pathogen killing. T. gondii is an obligate intracellular protozoan that survives within host cells by residing in a parasitophorous vacuole that avoids fusion with lysosomes. CD40, a member of the TNF receptor superfamily that is expressed on antigen presenting cells including macrophages [78], reroutes the parasitophorous vacuole to the lysosomal compartment via autophagy causing killing of the parasite [79,80]. CD40 stimulation of macrophages results in co-localization of LC3 around the parasitophorous vacuole [79]. This is followed by fusion with late endosomes/lysosomes [79]. Multiple genetic and pharmacologic approaches that impaired autophagy and lysosomal degradation demonstrated that autophagy is responsible for killing of T. gondii [79]. Autophagic killing of T. gondii required synergy between TRAF6, an adaptor protein downstream of CD40 and TNF-α [80], and was independent of the IRG proteins Irgm1, Irgm3 and Irgd [81]. It is likely that autophagy mediates at least in part the in vivo protective effect of CD40 against T. gondii in humans and mice [81–83].

IFN-γ-treated macrophages exhibit autophagosome formation around T. gondii [84], However, formation of autophagosomes in IFN-γ-treated macrophages is probably not the cause of death of the parasite but rather a response to the presence of altered structures (disrupted parasitophorous membranes and denuded tachyzoites) within the host cell. Indeed, genetic and pharmacological inhibition of autophagy and lysosomal degradation did not affect anti-T. gondii activity induced by IFN-γ but ablated that caused by CD40 [79]. A recent study reported the importance of immune-activated autophagy in control of Chlamydia trachomatis [85]. MEF treated with IFN-γ exhibit enhanced interaction between C. trachomatis inclusions and LC3 and late endosomes/lysosomes. The IRG protein Irga6 is necessary for fusion with autophagosomes and rerouting to the lysosomes [85].

Presentation of microbial antigens to CD4+ T cells is another aspect of adaptive immunity that appears to be enhanced by autophagy. MHC class II-positive cells, including dendritic, B and epithelial cells exhibit constitutive autophagosome formation [86]. The autophagosomes continuously fuse with multivesicular MHC class II-loading compartments [86]. It appears that the role of autophagy in antigen presentation may antigen specific. Autophagy was found not to be involved in antigen recognition by Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) nuclear antigen 2 (EBNA2)- and EBNA3C-restricted CD4+ T-cell clones [87]. By contrast, EBNA1 has been reported to be presented to MHC class II molecules in EBV-transformed B-cell lines after autophagy [88]. These results may be of relevance since CD4+ T cells that recognize EBNA inhibit the growth of EBV-transformed lymphoblastoid cell lines. Autophagy may promote host protection by improving recognition of microbial antigens. Indeed, in a model of immunization with M. tuberculosis-infected dendritic cells, pretreatment of these cells with rapamycin, an inducer of autophagy, improved in vivo protection after challenge with M. tuberculosis [89]. Recent studies uncovered a role for autophagy in presentation of microbial antigens to CD8+ T cells [90,91]. In macrophages infected with HSV-1, presentation of viral antigen glycoprotein B involves initially the classical MHC class I pathway [90]. This is followed by autophagy that facilitates processing of glycoprotein B and activation of CD8+ T cells [90]. Autophagy and antigen presentation are enhanced by IL-1β [90]. Immunization of mice with influenza-infected fibroblasts undergoing autophagy prior to cell death results in enhanced priming of hemagglutinin-specific CD8+ T cells [91]. This enhanced priming is probably mediated by prolonged MHC I cross-presentation and production of type I interferons by dendritic cells that phagocytose dying fibroblasts [91]. All these studies support that stimulation of autophagy may improve immunization strategies against various pathogens.

Increasing evidence indicates that autophagy proteins regulate cellular responses other than autophagy. While autophagy does not mediate the anti-T. gondii activity triggered by IFN-γ, Atg5 is involved in autophagy-independent killing of the parasite in IFN-γ-activated phagocytic cells [92]. Atg5 is required for recruitment of the IRG protein IIGP1 to the parasitophorous vacuole, the damage to this structure and clearance of the parasite [92].

Future attempts to stimulate autophagy as a therapeutic approach against infections should consider the possibility that this approach may not be universally beneficial. For example, it has been suggested that RNA viruses such as poliovirus and mouse hepatitis virus use autophagosome membranes as a scaffolding to promote viral genome replication [93,94]. Of note, a recent study in primary macrophages did not find a role for autophagy in the replication of mouse hepatitis virus [95]. Autophagy also enhances replication of Coxsackievirus B3 [96]. In addition, as stated before, the Atg12–Atg5 conjugate appears to promote in vitro replication of VSV in MEF by impairing type I interferon production [75].

Manipulation of autophagy

The role of autophagy in the pathogenesis of many disorders and in the elimination of certain pathogens has sparked interest in manipulation of autophagy for therapeutic purposes [97,98]. Before addressing the pathogens that may be amenable to therapeutic manipulation of autophagy and the caveats with the design of such approaches, we will summarize some of the work that examined the effects of stimulation of autophagy. Many important studies that explored therapeutic manipulation of autophagy were not conducted in models of infection but rather in models of neuro-degeneration. We include those studies since the conserved nature of many of the features of autophagy suggests that results from these studies may be applicable to future attempts to manipulate autophagy to enhance protection against pathogens.

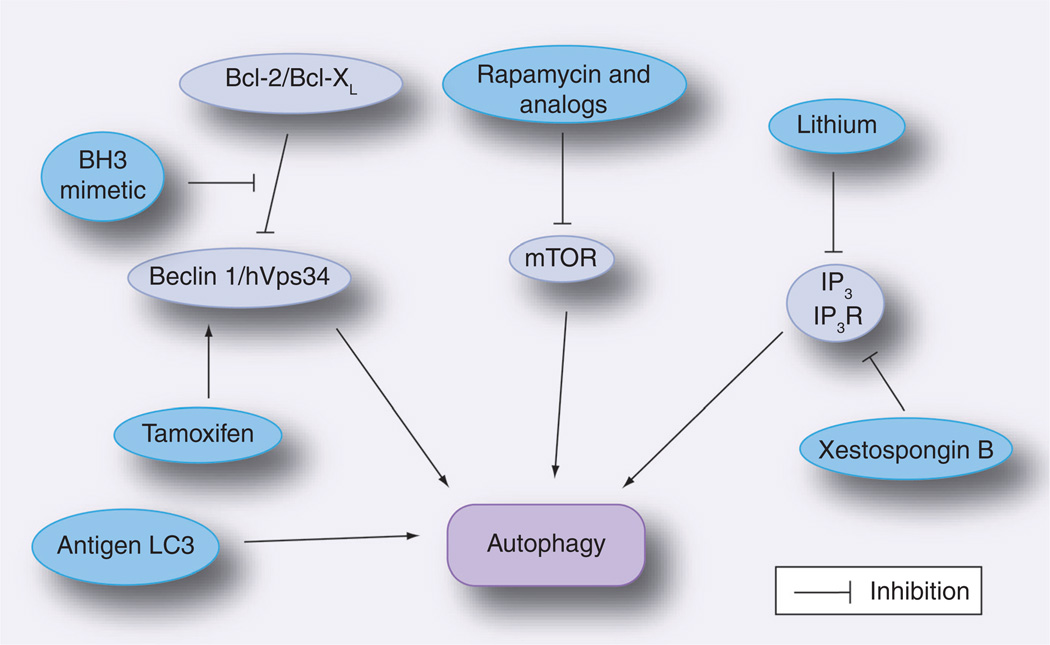

Studies in models of neurodegenerative diseases support the concept of targeting mTOR activity to enhance autophagy for therapeutic benefit. Accumulation of aggregated proteins is an important feature of neurodegenerative disorders. Enhanced degradation of these proteins has been proposed as a potential therapeutic approach for these diseases. Rapamycin inhibits mTOR and thus stimulates autophagy (Figure 2). Rapamycin was reported to enhance the clearance of aggregate-prone proteins within cells and to diminish toxicity [99,100]. Accumulation of α-synuclein in neurons is the hallmark of Parkinson’s disease. Cells treated with rapamycin exhibit increased clearance of α-synuclein [101]. Rapamycin also exhibited protective effects in vivo. Expression of aggregate-prone mutant proteins resulted in toxicity (abnormal eyes) and decreased survival in Drosophila [100,102]. In vivo administration of rapamycin diminished toxicity, improved survival and promoted clearance of these aggregate-prone proteins [100,102]. The protective effects of rapamycin were probably mediated through autophagy since this drug failed to induce protection in Drosophila deficient in the autophagy protein Atg1 [100]. Moreover, the rapamycin analog CCI-779 decreased aggregate formation and improved performance on behavioral tasks in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease [102].

Figure 2. Approaches to stimulate autophagy.

Strategies utilized to enhance autophagy include: inhibition of mTOR with rapamycin or analogs of rapamycin, inhibition of IP3 levels or of the IP3R, upregulation of Beclin 1 and inhibition of Beclin 1–Bcl-2/Bcl-XL interaction. An antigen fused to LC3 is targeted to autophagosomes and results in enhanced MHC class II presentation.

mTOR: Mammalian target of rapamycin; IP3: Inositol triphosphate; IP3R: Inositol triphosphate receptor.

In vitro studies using M. tuberculosis, T. gondii and B. pseudomallei also suggest that pharmacologic stimulation of autophagy may improve control of pathogens [52,60,79]. Treatment of macrophages with rapamycin induced co-localization of the autophagosome marker LC3 around T. gondii-containing parasitophorous vacuoles [79] and enhanced acidification of mycobacterial phagosomes [52]. This was accompanied by antimicrobial activity [52,79]. The effect of rapamycin was unlikely to be mediated by direct antimicrobial activity (rapamycin is a macrolide) since knockdown of Beclin 1 remarkably impaired the anti-T. gondii activity induced by rapamycin [79]. Rapamycin also resulted in decreased survival of B. pseudomallei [60]. While these studies provide impetus for exploration of autophagy stimulation to enhance pathogen eradication, it should be kept in mind that the immunosuppressive activity of rapamycin raises concern regarding the efficacy of approaches based solely on administration of this drug. Another study reported that small molecule enhancers of rapamycin identified by screening in yeast cause killing of BCG within macrophages [103].

The identification of mTOR-independent autophagy uncovered other potential therapeutic targets for stimulation of autophagy. Lithium diminishes IP3 levels and thus stimulates autophagy (Figure 2) [45]. Lithium has been reported to promote clearance of mutant Huntingtin and α-synuclein [45]. However, the pro-autophagy activity of lithium can be partially antagonized by an additional effect of this drug on autophagy signaling. Lithium also inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3β, resulting in mTOR activation (activated mTOR impairs autophagy) [104]. These results may be of therapeutic relevance because the combination of lithium plus rapamycin exhibited greater protection against neurodegeneration in a fly model of Huntington’s disease than each drug individually [104]. Pharmacologic inhibition of the IP3 receptor using xestospongin B has also been reported to stimulate autophagy (Figure 2) [46]. A recent study identified Ca2+ channel antagonists, minoxidil and clonidine as mTOR-independent stimulators of autophagy [105]. These drugs showed beneficial effects in models of Huntington’s disease in Drosophila and zebrafish [105].

Beclin 1 may to be another therapeutic target for modulation of autophagy. The level of Beclin 1 appears to be an important factor that controls autophagy. In this regard, overexpression of Beclin 1 protects mice against lethal Sindbis virus encephalitis [29] while, for example, Beclin 1 deficiency promotes neurodegeneration in mice [12]. Of relevance, tamoxifen appears to stimulate autophagy at least in part by enhancing the expression of Beclin 1 (Figure 2) [106]. The activity of Beclin 1 can also be targeted pharmacologically. Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL bind to the BH3 domain of Beclin 1 and inhibit autophagy [107]. The pharmacological BH3 mimetic ABT737 stimulates autophagy because this drug competitively inhibits the interaction between Beclin 1 and Bcl-2/Bcl-XL, preventing these molecules from inhibiting autophagy (Figure 2) [107].

As mentioned before, TLR can induce autophagy [63,65]. Manipulation of TLR signaling has been proposed as a potential approach to promote pathogen control. Indeed, TLR-4 and TLR-7 enhanced co-localization of M. tuberculosis with autophagosomes and pathogen elimination [63,65].

Autophagy has not only been linked to antigen presentation but it appears that directing immunogens to the autophagic pathway may improve the ability of vaccines to induce helper T-cell stimulation. In this regard, fusion of the influenza matrix protein 1 to LC3 targets this antigen to autophagosomes and causes a four- to 20-fold increase in MHC class II presentation to CD4+ T cells (Figure 2) [86].

The evidence that pathogens utilize autophagy to promote their growth indicates that stimulation of autophagy is unlikely to be beneficial against all infections. For example, rapamycin enhances growth of pathogens that include poliovirus, Coxsackievirus B3 and Coxiella burnetti [94,96,108]. Approaches to stimulate autophagy may be of therapeutic value against infections caused by pathogens that are susceptible to autophagic killing. Studies that explore how different arms of the immune response activate autophagy may identify molecular targets that selectively induce autophagic elimination of these pathogens. Stimulation of autophagy may also be beneficial against pathogens that avoid autophagy. This may be accomplished by preventing virulence factors from blocking autophagy. By contrast, treatment against pathogens that utilize autophagy to promote their growth may be accomplished by inhibition of autophagy through blocking the effects of the factors that subvert autophagy.

In summary, experimental evidence suggest that stimulation of autophagy may facilitate pathogen eradication and immune recognition. However, it is important to consider caveats to such an approach. First, the drugs used so far to stimulate autophagy are likely not specific and can alter other cellular functions. Second, some molecules in autophagy signaling (such as mTOR) can control other cellular responses in addition to autophagy. Third, generalized inhibition of autophagy can affect cellular homeostasis. For example, autophagy modulates T-cell homeostasis [109–111]. Autophagy mediates T-cell death after growth factor withdrawal [110]. Moreover, Th2 CD4+ cells exhibit higher levels of autophagy than Th1 CD4+ cells after growth factor withdrawal [110]. Thus, stimulation of autophagy may result in a preferential loss of Th2 CD4+ cells and impaired humoral immunity. Fourth, certain eukaryotic pathogens may themselves express autophagy and utilize this process as a virulence mechanism [112]. These caveats could be addressed by targeting key regulators of autophagy identified in studies of immune-based activation of autophagy and pathogen-induced evasion or subversion of this process. In addition, new and more specific small molecules that modulate autophagy could be identified using screening in yeast as recently reported [103,113]. Future studies aimed at further characterization of the regulation of autophagy and identification of selective modulators of this process may prove fruitful in our quest to improve treatment and prevention of various infections.

Expert commentary

Autophagy was initially described as a homeostatic mechanism stimulated within cells in response to starvation in order to provide cells with substrates for macromolecule synthesis and ATP production. Autophagy is now recognized to play an adaptive role in many other conditions including infections. There is considerable interest in developing approaches to treat infections based on manipulation of autophagy cascades and/or pathways that regulate this process. The increasing evidence on the role of autophagy in antigen presentation suggests that modulation of autophagy may represent a novel approach to improve the immunogenicity of vaccines.

Five-year view

The design of approaches that specifically modulate autophagy for therapeutic purposes against infections will probably require achieving a better understanding of the regulation of autophagy. In particular, there is a need to dissect the pathways by which the immune response triggers autophagy and identify the counter measures used by some organisms to prevent autophagy or subvert this process to promote their growth. Given the highly conserved nature of autophagic pathways from yeast to mammals, the identification of new agents that selectively modulate autophagy can be facilitated by the use of screens in yeasts. The major effort currently devoted by many scientists to the study of autophagy raises the possibility that important advances in the design of measures to treat and prevent infections may become a reality in the near future.

Key issues

Autophagy is a homeostatic intracellular mechanism that can regulate various aspects of the interaction between the host and pathogens.

Autophagy can be stimulated by different components of the immune system to trigger degradation of different pathogens. Certain microorganisms actively block autophagy to survive within host cells while other pathogens utilize the autophagy machinery to promote their growth.

Autophagy can enhance antigen presentation and thus stimulate adaptive immunity. Autophagy can also influence T-cell homeostasis and differentiation.

The complex role of autophagy during host–pathogen interactions indicates that manipulation of this cellular response will probably need to be tailored to the pathogen of interest.

In vitro studies have shown the validity of pharmacologic modulation of autophagy to promote pathogen eradication.

In vivo studies carried out primarily in models of neurodegeneration have demonstrated the therapeutic benefits of modulation of autophagy.

Pharmacologic agents currently available to modulate autophagy typically exhibit nonspecific effects.

The design of rational therapeutic approaches will probably require a better understanding on how the immune system triggers autophagy and how pathogens block or subvert this process.

Acknowledgments

Carlos Subauste is supported by NIH grants EY018341 and AI48406, the American Heart Association (Ohio Valley Affiliate), the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation International, the Dietrich Diabetes Research Institute, the Ohio Lions Eye Research Foundation and the Research to Prevent Blindness Foundation.

Footnotes

Financial & competing interests disclosure

The author has no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

• of interest

•• of considerable interest

- 1.Klionsky DJ, Emr SD. Autophagy as a regulated pathway of cellular degradation. Science. 2000;290:1717–1721. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. Autophagosome formation in mammalian cells. Cell. Struct. Funct. 2002;27:421–429. doi: 10.1247/csf.27.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshimori T. Autophagy: a regulated bulk degradation process inside cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2004;313:453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn WAJ. Autophagy and related mechanisms of lysosome-mediated protein degradation. Trends Cell Biol. 1994;110:1923–1933. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(94)90069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lum JJ, DeBerardinis RJ, Thompson CB. Autophagy in metazoans: cell survival in the land of plenty. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;l6:439–448. doi: 10.1038/nrm1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu L, Alva A, Su H, et al. Regulation of an ATG7–Beclin 1 program of autophagic cell death by caspase-8. Science. 2004;304:1500–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.1096645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maiuri MC, Zalckvar E, Kimchi A, Kroemer G. Self-eating and self-killing: crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:741–752. doi: 10.1038/nrm2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melendez A, Talloczy Z, Seaman M, Eskelinen EL, Hall DH, Levine B. Autophagy genes are essential for dauer development and life-span extension in C. elegans. Science. 2003;301:1387–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.1087782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liang XH, Jackson S, Seaman M, et al. Induction of autophagy and inhibition of tumorigenesis by Beclin 1. Nature. 1999;402:672–676. doi: 10.1038/45257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Komatsu M, Waguri S, Chiba T, et al. Loss of autophagy in the central nervous system causes neurodegeneration in mice. Nature. 2006;441:880–884. doi: 10.1038/nature04723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hara T, Nakamura K, Matsui M, et al. Suppression of basal autophagy in neural cells causes neurodegenerative disease in mice. Nature. 2006;441:885–889. doi: 10.1038/nature04724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pickford F, Masliah E, Britschgi M, et al. The autophagy-related protein Beclin 1 shows reduced expression in early Alzheimer disease and regulates amyloid β accumulation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:2190–2199. doi: 10.1172/JCI33585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shintani T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy in health and disease: a double-edged sword. Science. 2004;306:990–995. doi: 10.1126/science.1099993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kondo Y, Kanzawa T, Sawaya R, Kondo S. The role of autophagy in cancer development and response to therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:726–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuervo AM. Autophagy: in sickness and in health. Trends Cell Biol. 2006;14:70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levine B. Autophagy and cancer. Nature. 2007;446:745–747. doi: 10.1038/446745a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levine B, Deretic V. Unveiling the roles of autophagy in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007;7:767–777. doi: 10.1038/nri2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Meijer AJ, Codogno P. Signalling and autophagy regulation in health and disease. Mol. Aspects Med. 2006;27:411–425. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2006.08.002. Comprehensive review of signaling cascades that regulate autophagy.

- 19. Pattingre S, Espert L, Biard-Piechaczyk M, Codogno P. Regulation of macroautophagy by mTOR and Beclin 1 complexes. Biochemie. 2008;90:313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.08.014. Comprehensive review of signaling cascades that regulate autophagy.

- 20.Blommaart EF, Luiken JJ, Blommaart PJ, van Woerkom GM, Meijer AJ. Phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 is inhibitory for autophagy in isolated rat hepatocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:2320–2326. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.5.2320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mizushima N, Noda T, Yoshimori T, et al. A protein conjugation system essential for autophagy. Nature. 1998;395:395–398. doi: 10.1038/26506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ichimura Y, Kirisako T, Takao T, et al. A ubiquitin-like system mediates protein lipidation. Nature. 2000;408:488–492. doi: 10.1038/35044114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohsumi Y. Molecular dissection of autophagy: two ubiquitin-like systems. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2001;2:211–216. doi: 10.1038/35056522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klionsky DJ, Cregg JM, Dunn WA, Jr, et al. A unified nomenclature for yeast autophagy-related genes. Dev. Cell. 2003;5:539–545. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki K, Ohsumi Y. Molecular machinery of autophagosome formation in yeast. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:2156–2161. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsuura A, Tsukada M, Wada Y, Ohsumi Y. Apg1p, a novel protein kinase required for the autophagic process in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene. 1997;192:245–250. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(97)00084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki K, Kirisako T, Kamada Y, Mizushima N, Noda T, Ohsumi Y. The pre-autophagosomal structure organized by concerted functions of APG gene is essential for autophagosome formation. EMBO J. 2001;20:5971–5981. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.21.5971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reggiori F, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy in the eukaryotic cell. Eukaryotic Cell. 2002;1:11–21. doi: 10.1128/EC.01.1.11-21.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liang XH, Kleeman LK, Jiang HH, et al. Protection against fatal Sindbis virus encephalitis by Beclin, a novel Bcl-2-interacting protein. J. Virol. 1998;72:8586–8596. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.8586-8596.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kihara A, Kabeya Y, Ohsumi Y, Yoshimori T. Beclin–phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complex functions at the trans-Golgi network. EMBO Rep. 2001;21:330–335. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liang XH, Yu J, Brown KD, Levine B. Beclin 1 contains a leucine-rich nuclear export signal that is required for its autophagy and tumor suppressor function. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3443–3449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Qu X, Yu J, Bhagat G, et al. Promotion of tumorigenesis by heterozygous disruption of the Beclin 1 autophagy gene. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;112:1809–1820. doi: 10.1172/JCI20039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tassa A, Roux MP, Attaix D, Bechet DM. Class III phosphoinositide 3-kinase–Beclin1 complex mediates the amino acid-dependent regulation of autophagy in C2C12 myotubes. Biochem. J. 2003;376:577–586. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Furuya N, Yu J, Byfield M, Pattingre S, Levine B. The evolutionary conserved domain of Beclin 1 is required for Vps34 binding, autophagy and tumor suppressor function. Autophagy. 2005;1:46–52. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.1.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liang C, Feng P, Ku B, et al. Autophagic and tumor suppressor activity of a novel Beclin-1-binding protein UVRAG. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:688–699. doi: 10.1038/ncb1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fimia GM, Stoykova A, Romagnoli A, et al. Ambra 1 regulates autophagy and development of the nervous system. Nature. 2007;447:1121–1125. doi: 10.1038/nature05925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pattingre S, Tassa A, Qu X, et al. Bcl-2 antiapoptotic proteins inhibit Beclin 1-dependent autophagy. Cell. 2005;122:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mizushima N, Kuma A, Kobayashi Y, et al. Mouse Apg16L, a novel WD-repeat protein, targets to the autophagic isolation membrane with the Apg12–Apg5 conjugate. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:1679–1688. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saitoh T, Fujita N, Jang MH, et al. Loss of the autophagy protein Atg16L1 enhances endotoxin-induced IL-1β production. Nature. 2008;456:264–269. doi: 10.1038/nature07383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fujita N, Itoh T, Omori H, Fukuda M, Noda T, Yoshimori T. The Atg16L complex specifies the site of LC3 lipidation for membrane biogenesis in autophagy. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:2092–2100. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kabeya Y, Mizushima N, Ueno T, et al. LC3, a mammalian homologue of yeast Apg8p, is localized in autophagosome membranes after processing. EMBO J. 2000;19:5720–5728. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.21.5720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gutierrez MG, Munafo DB, Beron W, Colombo MC. Rab7 is required for the normal progression of the autophagic pathway in mammalian cells. J. Cell Sci. 2004;117:2687–2697. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jager S, Bucci C, Tanida I, et al. Role for Rab7 in maturation of late autophagic vacuoles. J. Cell Sci. 2004;177:4837–4848. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Munafo DB, Colombo MI. Induction of autophagy causes dramatic changes in the subcellular distribution of GFP–Rab24. Traffic. 2002;3:472–482. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sarkar S, Floto A, Berger Z, et al. Lithium induces autophagy by inhibiting inositol monophosphatase. J. Cell Biol. 2005;170:1101–1111. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200504035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Criollo A, Maiuri MC, Tasdemir E, et al. Regulation of autophagy by the inositol triphosphate receptor. Cell Death Differ. 2007;14:1029–1039. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4402099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scarlatti F, Maffei R, Beau I, Codogno P, Ghidoni R. Role of non-canonical Beclin 1-independent autophagy in cell death induced by resveratrol in human breast carcinoma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15:1318–1329. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2008.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Scherz-Shouval R, Shvets E, Fass E, Shorer H, Gil L, Elazar Z. Reactive oxygen species are essential for autophagy and specifically regulate the activity of Atg4. EMBO J. 2007;26:1749–1760. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garcia MA, Meurs EF, Esteban M. The dsRNA protein kinase PKR: virus and cell control. Biochemie. 2007;89:799–811. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Talloczy Z, Jiang W, Virgin HW, et al. Regulation of starvation- and virus-induced autophagy by the eIF2α signaling pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:190–195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012485299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vergne I, Chua J, Deretic V. Tuberculosis toxin blocking phagosome maturation inhibits a novel Ca2+/calmodulin–PI3K hVPS34 cascade. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:653–659. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gutierrez MG, Master SS, Singh SB, Taylor GA, Colombo MC, Deretic V. Autophagy is defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell. 2004;119:753–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakagawa I, Amano A, Mizushima N, et al. Autophagy defends cells against invading Group A Streptococcus. Science. 2004;306:1037–1040. doi: 10.1126/science.1103966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Amano A, Nakagawa I, Yoshimori T. Autophagy in innate immunity against intracellular bacteria. J. Biochem. 2006;140:161–166. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvj162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ogawa M, Yoshimori T, Suzuki T, Sagara H, Mizushima N, Sasakawa C. Escape of intracellular Shigella from autophagy. Science. 2004;307:727–731. doi: 10.1126/science.1106036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rich KA, Burkett C, Webster P. Cytoplasmic bacteria can be targets for autophagy. Cell. Microbiol. 2003;5:455–468. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Py BF, Lipinski MM, Yuan J. Autophagy limits Listeria monocytogenes intracellular growth in the early phase of primary infection. Autophagy. 2007;3:117–125. doi: 10.4161/auto.3618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Birmingham CL, Canadien V, Gouin E, et al. Listeria monocytgenes evades killing by autophagy during colonization of host T cells. Autophagy. 2007;3:442–452. doi: 10.4161/auto.4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Birmingham CL, Smith AC, Bakowski MA, Yoshimori T, Brumell JH. Autophagy controls Salmonella infection in response to damage to the Salmonella-containing vacuole. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:11374–11383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509157200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cullinane M, Gong L, Li X, et al. Stimulation of autophagy suppresses the intracellular survival of Burkholderia pseudomallei in mammalian cell lines. Autophagy. 2008;4:744–753. doi: 10.4161/auto.6246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gutierrez MG, Saka HA, Chinen I, et al. Protective role of autophagy against Vibrio cholerae cytolysin, a pore-forming toxin from V. cholerae. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:1829–1834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601437104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Amer AO, Swanson MS. Autophagy is an immediate macrophage response to Legionella pneumophila. Cell. Microbiol. 2005;7:765–778. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00509.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu Y, Jagannath C, Liu XD, Sharafkhaneh A, Kolodziejska KE, Eissa NT. Toll-like receptor 4 is a sensor for autophagy associated with innate immunity. Immunity. 2007;27:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sanjuan MA, Dillo CP, Tait SWG, et al. Toll-like receptor signalling in macrophages links the autophagy pathway to phagocytosis. Nature. 2007;450:1253–1257. doi: 10.1038/nature06421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Delgado MA, Elmaoued RA, Davis AS, Kyei G, Deretic V. Toll-like receptors control autophagy. EMBO J. 2008;27:1110–1121. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yano T, Mita S, Ohmori H, et al. Autophagic control of listeria through intracellular innate immune recognition in drosophila. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:908–916. doi: 10.1038/ni.1634. First evidence that autophagy confers in vivo protection against a pathogen in animals.

- 67.Shi C-S, Kehrl JH. MyD88 and Trif target Beclin 1 to trigger autophagy in macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:33175–33182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804478200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Checroun C, Wehrly TD, Fischer ER, Hayes SF, Celli J. Autophagy-mediated reentry of Francisella tularensis into the endocytic compartment after cytoplasmic replication. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:14578–14583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601838103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hrstka R, Krocova Z, Cerny J, Vojtesek B, Macela A, Stulik J. Francisella tularensis strain LVS resides in MHC II-positive autophagic vacuoles in macrophages. Folia Microbiologica. 2007;52:631–636. doi: 10.1007/BF02932193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Suzuki T, Franchi L, Toma C, et al. Differential regulation of caspase-1 activation, pyroptosis, and autophagy via Ipaf and ASC in Shigella-infected macrophages. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e111. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Talloczy Z, Virgin HW, Levine B. PKR-dependent autophagic degradation of herpes simplex virus type 1. Autophagy. 2005;2:24–29. doi: 10.4161/auto.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Orvedahl A, Alexander D, Talloczy Z, et al. HSV-1 ICP34.5 confers neurovirulence by targeting the Beclin 1 autophagy protein. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;1:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2006.12.001. Provides evidence of the in vivo relevance of pathogen evasion of autophagy.

- 73. Shelly S, Lukinova N, Bambina S, Berman A, Cherry S. Autophagy is an essential component of Drosophila immunity against vesicular stomatitis virus. Immunity. 2009;30:588–598. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.009. Reports that autophagy provides in vivo protection against a virus.

- 74.Lee HK, Lund JM, Ramanathan B, Mizushima N, Iwasaki A. Autophagy-dependent viral recognition by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Science. 2007;315:1398–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1136880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jounai N, Takeshita F, Kobiyama K, et al. The Atg5–Atg12 conjugate associates with innate antiviral immune responses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:14050–14055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704014104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singh SB, Davis AS, Taylor GA, Deretic V. Human IRGM induces autophagy to eliminate intracellular mycobacteria. Science. 2006;313:1438–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1129577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harris J, de Haro SA, Master SS, et al. Th2 cytokines inhibit autophagic control of intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculsosis. Immunity. 2007;27:505–517. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van Kooten C, Banchereau J. CD40–CD40 ligand. J. Leuk. Biol. 2000;67:2–17. doi: 10.1002/jlb.67.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Andrade RM, Wessendarp M, Gubbels MJ, Striepen B, Subauste CS. CD40 induces macrophage anti-Toxoplasma gondii activity by triggering autophagy-dependent fusion of pathogen-containing vacuoles and lysosomes. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:2366–2377. doi: 10.1172/JCI28796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Subauste CS, Andrade RM, Wessendarp M. CD40–TRAF6 and autophagy-dependent anti-microbial activity in macrophages. Autophagy. 2007;3:245–248. doi: 10.4161/auto.3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Subauste CS, Wessendarp M. CD40 restrains the in vivo growth of Toxoplasma gondii independently of γ interferon. Infect. Immun. 2006;74:1573–1579. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1573-1579.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Subauste CS, Wessendarp M, Sorensen RU, Leiva L. CD40–CD40 ligand interaction is central to cell-mediated immunity against Toxoplasma gondii: Patients with hyper IgM syndrome have a defective type-1 immune response which can be restored by soluble CD40L trimer. J. Immunol. 1999;162:6690–6700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Reichmann G, Walker W, Villegas EN, et al. The CD40/CD40 ligand interaction is required for resistance to toxoplasmic encephalitis. Infect. Immun. 2000;68:1312–1318. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1312-1318.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ling YM, Shaw MH, Ayala C, et al. Vacuolar and plasma membrane stripping and autophagic elimination of Toxoplasma gondii in primed effector macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:2063–2071. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Al-Zeer MA, Al-Younes HA, Braun PR, Zerrahn J, Meyer TF. IFN-γ-inducible Irga6 mediates host resistance against Chlamydia trachomatosis via autophagy. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4588. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Schmid D, Pypaert M, Munz C. Antigen-loading compartments for major histocompatibility complex class II molecules continuously receive input from autophagosomes. Immunity. 2007;26:79–92. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.10.018. Reports that linking of an antigen to the autophagy protein LC3 augments antigen presentation.

- 87.Taylor GS, Long HM, Haigh TA, Larsen M, Brooks J, Rickinson AB. A role for intercellular antigen transfer in the recognition of EBV-transformed B cell lines by EBV nuclear antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 2006;177:3746–3756. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.3746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Paludan C, Schmid D, Landthaler M, et al. Endogenous MHC class II processing of a viral nuclear antigen after autophagy. Science. 2005;307:593–596. doi: 10.1126/science.1104904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Jagannath C, Lindsey DR, Dhandayuthapani S, Xu Y, Hunter RIJ, Eissa NT. Autophagy enhances the efficacy of BCG vaccine by increasing peptide presentation in mouse dendritic cells. Nat. Med. 2009;15:267–276. doi: 10.1038/nm.1928. Reports that stimulation of autophagy enhances efficiency of vaccination.

- 90.English L, Chemali M, Duron J, et al. Autophagy enhances the presentation of endogenous viral antigens on MHC class I molecules during HSV-1 infection. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:480–487. doi: 10.1038/ni.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Uhl M, Kepp O, Jusforgues-Saklani H, Vicencio J-M, Kroemer G, Albert ML. Autophagy within the antigen donor cell facilitates efficient antigen cross-priming of virus-specific CD8+ T cells. Cell Death Differ. 2009 doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.8. (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhao Z, Fux B, Goodwin M, et al. Autophagosome-independent essential function for the autophagy protein Atg5 in cellular immunity to intracellular pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Prentice E, Jerome WG, Yoshimori T, Mizushima N, Denison MR. Coronavirus replication complex formation utilizes components of cellular autophagy. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:10136–10141. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306124200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jackson WT, Giddings THJ, Taylor MP, et al. Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zhao Z, Thackray LB, Miller BC, et al. Coronavirus replication does not require the autophagy gene Atg5. Autophagy. 2007;6:581–585. doi: 10.4161/auto.4782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wong J, Zhang J, Si X, et al. Autophagosome supports Coxsackievirus B3 replication in host cells. J. Virol. 2008;82:9143–9153. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00641-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rubinsztein DC, Gestwicki JE, Murphy LO, Klionsky DJ. Potential therapeutic applications of autophagy. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6:304–312. doi: 10.1038/nrd2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Martinez-Vicente M, Cuervo AM. Autophagy and neurodegeneration: when the cleaning crew goes on strike. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:352–361. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ravikumar B, Duden R, Rubinsztein DC. Aggregate-prone proteins with polyglutamine and polyalanine expansions are degraded by autophagy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:1107–1117. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.9.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Berger Z, Ravikumar B, Menzies FM, et al. Rapamycin alleviates toxicity of different aggregate-prone proteins. Human Mol. Gen. 2006;15:433–442. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi458. Shows that pharmacologic stimulation of autophagy is beneficial in an animal model of disease caused by accumulation of aggregate-prone proteins.

- 101.Webb JL, Ravikumar B, Atkins J, Skepper JN, Rubinsztein DC. α-synuclein is degraded by both autophagy and proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:25009–25013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300227200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Ravikumar B, Vacher C, Berger Z, et al. Inhibition of mTOR induces autophagy and reduces toxicity of polyglutamine expansions in fly and mouse models of Huntington disease. Nat. Genet. 2004;36:585–595. doi: 10.1038/ng1362. Reports that pharmacologic stimulation of autophagy improves performance on behavioral tasks in a mouse model of Huntington’s disease.

- 103.Floto RA, Sarkar S, Perlstein EO, Kampmann B, Schreiber SL, Rubinsztein DC. Small molecule enhancers of rapamycin-induced TOR inhibition promote autophagy, reduce toxicty in Huntington’s disease models and enhance killing of mycobacteria by macrophages. Autophagy. 2007;3:620–622. doi: 10.4161/auto.4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Sarkar S, Krishna G, Imarisio S, Saiki S, O’Kane CJ, Rubinsztein DC. A rational mechanism for combination treatment of Huntington’s disease using lithium and rapamycin. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2008;17:170–178. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm294. Reports that combination of two agents that modulate autophagy confers greater protection in a fly model of neurodegeneration.

- 105.Williams A, Sarkar S, Cuddon P, et al. Novel targets for Huntington’s disease in an mTOR independent autophagy pathway. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:295–305. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Scarlatti F, Bauvy C, Ventruti A, et al. Ceramide-mediated macroautophagy involves inhibition of protein kinase B and up-regulation of Beclin 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:18384–18391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313561200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Maiuri MC, Toumelin GL, Criollo A, et al. Functional and physical interaction between Bcl-Xl and BH3-like domain in Beclin 1. EMBO J. 2007;26:2527–2539. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gutierrez MG, Vasquez CL, Munafo DB, et al. Autophagy induction favours the generation and maturation of the Coxiella-replicative vacuoles. Cell. Microbiol. 2005;7:981–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pua HH, Dzhagalov I, Chuck M, Mizusshima N, He Y-W. A critical role for the autophagy gene Atg5 in T cell survival and proliferation. J. Exp. Med. 2007;204:25–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li C, Capan E, Zhao Y, et al. Autophagy is induced in CD4+ T cells and important for the growth factor-withdrawal cell death. J. Immunol. 177:5163–5168. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Feng CG, Zheng L, Jankovic D, et al. The immunity-related GTPase Irgm1 promotes the expansion of activated CD4+ T cell populations by preventing interferon-γ-induced cell death. Nat. Immunol. 2008;11:1279–1287. doi: 10.1038/ni.1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hu G, Hacham M, Waterman SR, et al. PI3K signaling of autophagy is required for starvation tolerance and virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:1186–1197. doi: 10.1172/JCI32053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sarkar S, Perlstein EO, Imarisio S, et al. Small molecules enhance autophagy and reduce toxicity in Huntington’s disease models. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:331–338. doi: 10.1038/nchembio883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]