Abstract

Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa) is an obligate biotroph oomycete pathogen of the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana and contains a large set of effector proteins that are translocated to the host to exert virulence functions or trigger immune responses. These effectors are characterized by conserved amino-terminal translocation sequences and highly divergent carboxyl-terminal functional domains. The availability of the Hpa genome sequence allowed the computational prediction of effectors and the development of effector delivery systems enabled validation of the predicted effectors in Arabidopsis. In this study, we identified a novel effector ATR39-1 by computational methods, which was found to trigger a resistance response in the Arabidopsis ecotype Weiningen (Wei-0). The allelic variant of this effector, ATR39-2, is not recognized, and two amino acid residues were identified and shown to be critical for this loss of recognition. The resistance protein responsible for recognition of the ATR39-1 effector in Arabidopsis is RPP39 and was identified by map-based cloning. RPP39 is a member of the CC-NBS-LRR family of resistance proteins and requires the signaling gene NDR1 for full activity. Recognition of ATR39-1 in Wei-0 does not inhibit growth of Hpa strains expressing the effector, suggesting complex mechanisms of pathogen evasion of recognition, and is similar to what has been shown in several other cases of plant-oomycete interactions. Identification of this resistance gene/effector pair adds to our knowledge of plant resistance mechanisms and provides the basis for further functional analyses.

Author Summary

Oomycete plant pathogens are among the most devastating agricultural pests and employ arsenals of effector proteins to manipulate their plant hosts. Some of these effectors, however, are recognized in the plant and trigger an immune response. Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa) causes downy mildew on the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana and this interaction has been developed as a model system for oomycete pathogenesis. Here, we employ computational predictions to identify a novel effector ATR39-1, which is highly conserved among different Hpa isolates. A two amino acid-insertion in the alternative allele ATR39-2 correlated with evasion of recognition. We identified the corresponding resistance gene RPP39 and found that the signaling gene NDR1 is required to establish full resistance. Recognition of ATR39-1 by RPP39 in the plant did not inhibit growth of the oomycete, suggesting that complex mechanisms exist to prevent effector recognition. Knowledge of such novel resistance interactions provides the backbone of our understanding of plant resistance mechanisms and will aid in the further dissection of plant immunity.

Introduction

Oomycetes comprise a number of agriculturally important plant pathogens, including Phytophthora infestans (potato and tomato late blight), P. ramorum (sudden oak death) and P. sojae (soybean root rot). Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa, downy mildew, formerly known as Peronospora parasitica) is a naturally occurring oomycete pathogen of the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. The Hpa/Arabidopsis pathosystem allows the scientific community to take advantage of the genetic tools developed for Arabidopsis in the dissection of plant responses to oomycetes [1]. During their parasitic life stages, oomycetes deliver an arsenal of effector proteins to their plant host, which are hypothesized to target basal defense mechanisms and/or manipulate host metabolism to extract nutrients for the pathogen [2]. The first oomycete effector proteins were, however, identified based on their avirulence functions, i.e. their presence triggered an immune response in the host resulting in resistance to the pathogen. This so-called effector triggered immunity (ETI) is characterized by the specific recognition of pathogen avirulence effectors by plant resistance receptors, either directly or indirectly [3]. ETI is often accompanied by localized cell death at the site of infection, the hypersensitive response (HR), which limits the spread of biotrophic pathogens inside the plant host [4]. The Hpa effectors Arabidopsis thaliana recognized 1 (ATR1), ATR13 and ATR5 as well as Avr1b from P. sojae were identified using classic genetic crosses between virulent and avirulent pathogen strains [5]–[8], and have been shown to be under strong positive selection. P. infestans effector Avr3a, on the other hand, was isolated using association genetics [9]. Interestingly, despite having no sequence homology, Avr3a and ATR1 reside in conserved syntenic regions within the genome [9] and their three-dimensional structures reveal a similar fold between Avr3a and a sub-domain of ATR1 [10]–[13].

All currently described oomycete effectors were found to have a modular domain structure, containing amino-terminal domains involved in effector translocation and carboxyl-terminal effector domains. The translocation domains typically include a secretion signal sequence followed by the amino acid motif Arg-x-Leu-Arg (RxLR), in which x could be any amino acid. The RxLR motif was shown to be important in translocation of effectors to the host cytoplasm and it is also functionally interchangeable with the translocation motif of Plasmodium falciparum effectors [14], [15]. The absence of a canonical RxLR motif in the recently cloned effector ATR5 suggests that other sequences may also be involved in translocation of effectors [8]. The carboxyl-terminal effector domains are highly divergent and typically do not have strong sequence similarity to other proteins.

The genomes of several Phytophthora species as well as of Hpa strain Emoy2 have recently been sequenced and this has fueled bioinformatics efforts to elucidate the complete arsenal of effectors [16]–[18]. Effector predictions were based on the presence of the amino-terminal translocation domains. While bacterial pathogens such as Pseudomonas syringae contain around 30 to 40 effector genes [19], the oomycete genomes were found to contain expanded effector repertoires, ranging from around 350 in P. sojae and P. ramorum to more than 700 in P. infestans [20]. Initial effector predictions from the Hpa genome yielded 149 RxLR effector genes [21], however, the published genome sequence for Hpa strain Emoy2 contains only 134 annotated RxLR effectors [17]. Currently, major efforts are being undertaken in dissecting the effector complement of several oomycetes in order to identify novel avirulence determinants as well as to define effector virulence functions. Several recent large-scale effector screens in different oomycetes focused on the localization of effectors in the plant cell during infection and on their roles in facilitating oomycete infections [22], [23]. These transgenic approaches identified effectors that localize to the oomycete haustorial feeding structures and may be important in mediating intercellular communication. Another study employed mining of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) to identify genes highly expressed during Hpa infection, and investigated their potential functions during compatible interactions [24]. An in planta expression screen of P. infestans effectors was successful in identifying the cognate avirulent effectors ipiO/AVRblb1 and AVRblb2, recognized by the R proteins Rpi-blb1 and Rpi-blb2, respectively [25], [26].

Resistance to different strains of Hpa was mapped to a number of RPP (Resistance to Peronospora parasitica) loci in several Arabidopsis ecotypes [27], [28]. Six of these R genes were subsequently cloned, but the corresponding recognized effectors have only been identified for three of them, RPP1, RPP13 and recently RPP5, which recognize ATR1, ATR13 and ATR5 respectively [5], [7], [8]. Similar to the R genes that function against other microbial pathogens, RPP genes belong to the large Nucleotide Binding Site-Leucine Rich Repeat (NBS-LRR) gene family in Arabidopsis, which comprises a total of around 150 members, but only a few with an assigned function [29]. Characterized R genes confer resistance to various classes of pathogens including oomycetes, bacteria, fungi and viruses. Additionally, NBS-LRR genes have been implicated in non-self recognition in inter-accession hybrids [30].

Research on RPP1/ATR1 and RPP13/ATR13 has greatly advanced our understanding of effector recognition and resistance signaling. Recognized ATR1 alleles have been shown to associate in planta with the LRR-domain of RPP1 before triggering an immune response [31]. Intracellular recognition of ATR13 by the CC-NBS-LRR protein RPP13 was shown to signal independently of the known signaling genes EDS1 and NDR1, indicating the presence of additional signaling pathways activated upon effector recognition [32].

In order to gain a better understanding of the interactions between Hpa and its host A. thaliana, we set out to screen 83 Arabidopsis ecotypes for novel recognition specificities with a subset of predicted Hpa effectors. Here, we describe a successful approach to mine the Hpa genome for functional effector proteins based on domain structure similarity to known oomycete RxLR effectors. We identified a novel avirulent RxLR effector, ATR39, which is recognized by the Arabidopsis ecotype Weiningen. Comparison of ATR39 alleles identified two amino acids that are critical for recognition. We cloned the corresponding R gene, RPP39, and showed that it is a member of a small cluster of CC-NBS-LRR genes and requires NDR1 for downstream signaling of plant defense responses. Our ability to combine computational predictions with molecular and genetic techniques will facilitate the rapid identification of novel R genes as well as inform our understanding of the evolution of pathogenesis and resistance.

Results

HMM prediction of effectors from the Hpa genome sequence

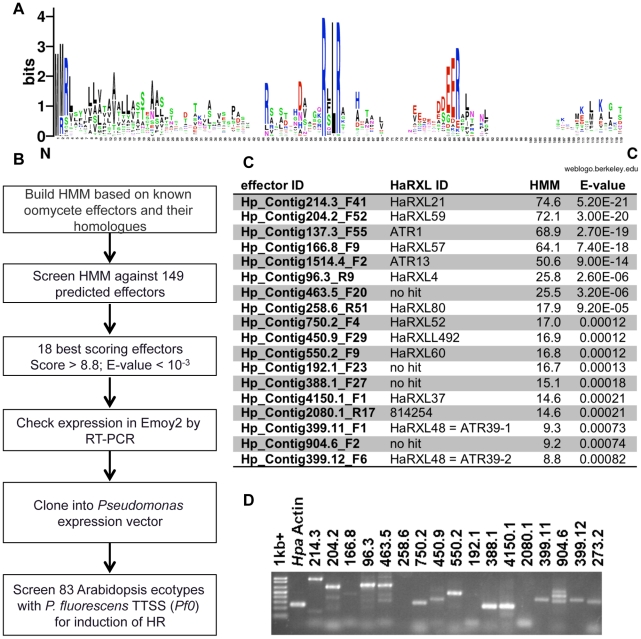

Based on characterized effectors from Phytophthora sp. and Hpa, intracellular oomycete effector proteins are predicted to contain several conserved domains: an N-terminal secretion signal peptide (SP), a central RxLR motif, and a C-terminal variable effector domain. Previously, Win et al. mined the Hpa genome (version 7.0) for predicted open reading frames of >70 amino acids, which contained the N-terminal SP and the RxLR motif between amino acids 30 and 60, and found 149 effectors fulfilling these criteria [21]. In order to refine this search we generated a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) from the N-terminal conserved domains (SP and RxLR) of previously identified effectors and their homologues (this set includes 43 proteins, [21], Figure 1A). HMMs are widely used to predict homologies with statistical significance, most prominently in the protein domain database Pfam [33]. This method allowed us to screen the 149 initially predicted effectors with the HMM model and prioritize them for experimental validation, as outlined in Figure 1B. We decided to focus downstream characterization on the 18 highest-scoring predicted effectors, with E-value scores <0.001 (Figure 1C). Amino acid and nucleotide sequences for these effectors are available in fasta format online as File S1 and S2, respectively. Interestingly, some of the predicted effectors scored even higher than two known effectors, ATR1 (Hp_Contig137.3_F55) and ATR13 (Hp_Contig1514.4_F2). We tested whether the predicted effectors were expressed during Hpa infection by RT-PCR and confirmed expression for 15 of them at seven days post-inoculation (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. Identification of functional avirulence effector candidates from Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis (Hpa) using a Hidden Markov Model (HMM)–based search.

A) Consensus sequence of 43 oomycete effectors used in building the HMM. The consensus was generated using the Weblogo program. Larger letters signify higher conservation. B) Screening scheme for identification of effectors. The steps in the pipeline are as follows: 1) Building HMM model based on N-terminal secretion signal and RXLR domains of known effectors; 2) Screening the HMM against 149 predicted effectors to form a prioritized list; 3) Focusing on 18 best scoring effectors with HMM score >8.5 and E-value <0.001; 4) Determining expression of predicted effectors in Hpa Emoy2 7 days post-infection (dpi); 5) Cloning expressed effectors in Pseudomonas vector pPsSP [35] or pEDV3 [36] and determining expression in P. fluorescens; 6) Screening 83 Arabidopsis ecotypes with effectors for induction of resistance response, visible as HR. C) Summary of highest scoring effector candidates identified by HMM search. Effector IDs correspond to position on contigs in Hpa genome version 7.0. HaRXL IDs are the annotated IDs in the published Hpa genome version 8.3. “No hit” indicates genes not annotated in the final genome. HMM scores and E-values are indicated. D) Expression of effectors in Hpa Emoy2 infected tissue 7 dpi as determined by RT-PCR.

Generating a system to screen for novel recognition specificities

Because of Hpa's obligate biotroph lifestyle, studies on Hpa have relied on surrogate systems, delivering oomycete effectors biolistically [34] or using bacterial or viral vectors [35], [36].

We PCR amplified the highest scoring expressed effectors from the Emoy2 isolate of Hpa, past the predicted signal peptide cleavage site, and cloned them into two Pseudomonas expression vectors. First, the effectors were shuttled into a Gateway-compatible Pseudomonas vector as C-terminal fusions with the AvrRpm1 type three secretion system (TTSS) signal peptide (pPsSP, [35]). However, we observed that ATR1 was not functional in this system, but was functional as a C-terminal fusion with the AvrRps4 TTSS signal peptide in the alternative pEDV3 system [36]. We thus decided to also subclone the predicted effectors into pEDV3 and test them in both expression systems. We conjugated these expression plasmids into Pseudomonas fluorescens (Pf0), a non-pathogenic Pseudomonas strain that lacks an endogenous TTSS and effectors and was engineered to express the Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (Pst) DC3000 hrp cluster and TTSS [37]. Using this strain allowed us to deliver individual effectors to the plant host, circumventing considerable background we often observed when inoculating a variety of ecotypes with Pst DC3000 (data not shown). We did not observe a reaction to Pf0 carrying an empty vector control in most ecotypes, even after 48 hours post-inoculation (hpi). Effector recognition on the other hand resulted in a visible hypersensitive response within 24 hpi (Figure 2A). We then screened 83 Arabidopsis ecotypes from the Nordborg collection (1, [38]) with Pf0 expressing each of the predicted effectors.

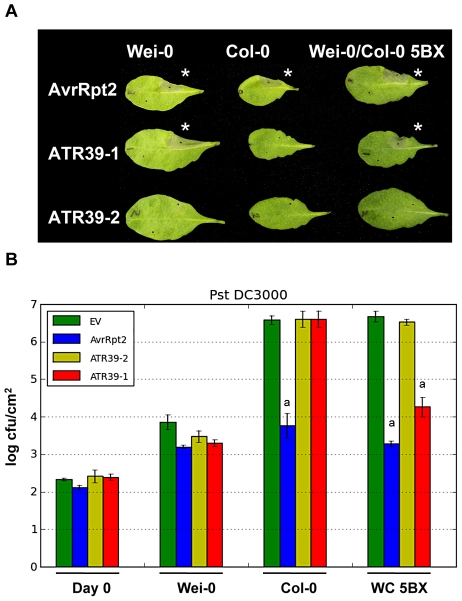

Figure 2. Hpa effector ATR39-1 is recognized by A. thaliana ecotype Wei-0.

A) ATR39-1, but not ATR39-2, triggers a hypersensitive response (HR) in the Arabidopsis ecotype Weiningen (Wei-0) when delivered by Pf0. The top half of the leaf was inoculated with the indicated effector, the bottom half with a negative GFP control. Wei-0 also contains a functional allele of RPS2 and AvrRpt2 was included as a positive control for HR. The picture was taken 24 hours post infection. Stars highlight induction of HR. B) ATR39-1 recognition inhibits growth of virulent Pst DC3000 in a Col-0 line where the RPP39 locus was introgressed (WC 5BX), while Wei-0 displays natural resistance towards Pst DC3000. Plants were inoculated with Pst DC3000 expressing the indicated effectors (105 cfu/mL) and bacterial titers determined 0 and 4 days post-infection. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Significant differences as determined by Student's t-test are indicated by small letters (P<0.0003). Experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results.

Hpa effector ATR39-1 is recognized by Arabidopsis ecotype Weiningen

One of the predicted effectors, Hp_Contig399.11_F1, triggered a visible HR in the ecotype Weiningen (Wei-0), when delivered by Pf0 (Figure 2A). Hp_Contig399.11_F1 has an HMM score of 9.3 and ranks number 16 of the predicted effectors (Figure 1C). None of the other 82 available ecotypes from the Nordborg collection displayed an HR upon delivery of Hp_Contig399.11_F1. According to nomenclature previously applied to Hpa effectors, we renamed this effector ATR39-1 (for A. thaliana recognized 39-1, accession number JQ045572).

In order to assess whether ATR39-1 conferred avirulence to pathogenic bacteria, we conducted bacterial growth assays but found that Wei-0 showed natural resistance towards several pathogenic Pseudomonas strains, including Pst DC3000 (Figure 2B) and P. syringae pv. maculicola (Psm) ES4326 (Figure S1). We therefore generated an introgression line in which the Wei-0 recognition locus was introduced into the Col-0 background by repeated backcrossing. Using this line (WC-5BX), we showed that ATR39-1 is indeed recognized by the Wei-0 locus and that this recognition results in decreased growth of Pst DC3000 (Figure 2B).

Unlike ATR1, ATR39-1 does not contain the acidic DEER (Asp-Glu-Glu-Arg) motif following the RxLR translocation motif. We also tested whether the effector-truncation past the RxLR motif triggers the hypersensitive response and found that the effector domain (ATR39-1 Δ48) is also able to trigger an HR when delivered by Pf0 (Figure S2).

ATR39 has two polymorphic alleles that are highly conserved among Hpa isolates

Using the same primers we amplified two alleles of ATR39 from Hpa strain Emoy2, but only one of them, ATR39-1, is recognized by Wei-0 (Figure 2). Both alleles are predicted in our HMM search with scores of 9.3 and 8.8 for ATR39-1 and ATR39-2, respectively. The two alleles differ by 10 nucleotides, resulting in 9 amino acid substitutions, and a 2 amino acid insertion in ATR39-2 relative to ATR39-1 (Figure 3A). In the published Hpa Emoy2 genome assembly ATR39-1 is not annotated, however, its allelic variant ATR39-2 is annotated as HaRxL48 [17].

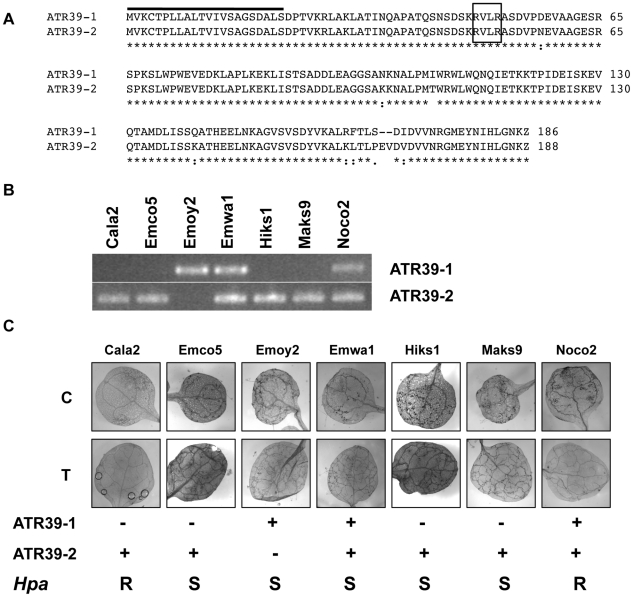

Figure 3. ATR39 alleles are expressed in different Hpa isolates, but expression of ATR39-1 does not correlate with avirulence on Wei-0.

A) Amino acid sequence alignment of ATR39-1 and ATR39-2 using ClustalW. B) RT-PCR with allele-specific primers from plants infected with the indicated Hpa isolates, harvested at 7 dpi. Sequencing of the amplified ATR39 fragments revealed the absence of additional polymorphisms in Hpa strains. C) Trypan blue staining of Wei-0 leaves inoculated with the indicated Hpa strains. Presence or absence of ATR39 alleles is indicated below, as well as qualitative scoring of Hpa growth on Wei-0. C, cotyledons; T, true leaves; S, susceptible; R, resistant.

We have generated Illumina paired-end sequencing data for the Emwa1 isolate of Hpa and could identify both alleles in the assembly (data not shown). In this assembly we do not see signatures of duplication events, suggesting that Hpa Emwa1 and possibly also Emoy2 and Noco2 are heterozygous at this locus.

Using allele-specific primers we amplified ATR39 alleles from seven isolates of Hpa and found that ATR39-1 is only present and expressed in Emoy2, Emwa1 and Noco2 isolates (Figure 3B). ATR39-2, on the other hand, is more prevalent in this set of Hpa isolates. Surprisingly, we could not amplify ATR39-2 from the Emoy2 isolate currently grown in our lab. Since we initially amplified the effectors from a DNA sample obtained from a different source than the Hpa Emoy2 strain, and there is evidence for heterozygosity in the various lab strains, it is possible that our current lab strain is now homozygous for ATR39-1. In order to determine whether this strain is Emoy2, we amplified and sequenced the ATR1 effector and verified that our lab strain is indeed Emoy2 (data not shown).

We sequenced the ATR39 amplification products and found no nucleotide polymorphisms among ATR39-1 or ATR39-2 alleles from the different Hpa isolates. This conservation is in stark contrast with other characterized Hpa effectors ATR1, ATR5 and ATR13, which are highly divergent [5], [8], [39]. These findings indicate that the two ATR39 alleles may have an important function in Hpa and may be maintained under strong balancing selection. Sequence comparisons and pattern searches yielded no obvious homologs or putative function for ATR39. Taken together, we have identified a novel effector from Hpa with unknown function that is able to trigger a resistance response in Arabidopsis.

Recognition of ATR39-1 is suppressed during Hpa infection

The Wei-0 ecotype was previously shown to be susceptible to multiple Hpa isolates [40]. We confirmed that despite being able to recognize ATR39-1 present in Emoy2, Emwa1 and Noco2, Wei-0 still supports growth of these isolates (Figure 3C). This lack of resistance is not due to the lack of ATR39-1 transcript since we detected ATR39-1 expression in infected tissue using RT-PCR (Figure 3B and Figure S3). A similar suppressed recognition phenotype was observed for one of the ATR1 alleles. The ATR1Emco5 allele is recognized in several Arabidopsis ecotypes, which remain susceptible to infection by Hpa Emco5 [5], [41].

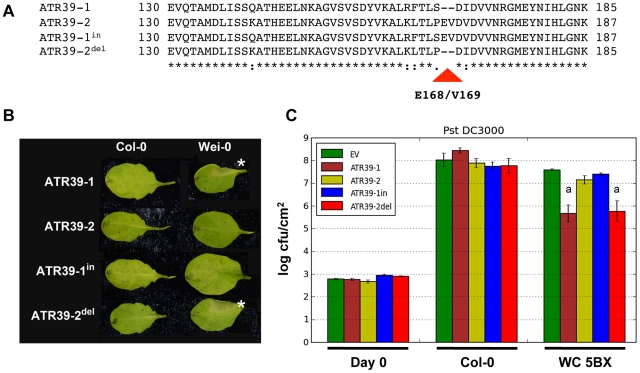

Recognition of ATR39 is abolished by E168/V169 in ATR39-2

ATR39-1 and ATR39-2 differ by 9 non-synonimous substitutions, and a two amino acid insertion in ATR39-2. In order to define the region in ATR39 responsible for differential recognition of the two alleles, we generated ATR39-1in by inserting E168/V169 into ATR39-1 using site-directed mutagenesis. Similarly, we generated ATR39-2del, in which E168/V169 were deleted (Figure 4A). ATR39-2del, but not ATR39-1in triggered an HR in Arabidopsis Wei-0 suggesting that the presence of amino acids E168/V169 blocks recognition of ATR39 (Figure 4B). Additionally, we performed Pst DC3000 growth assays and found that ATR39-2del restricted bacterial growth, whereas Pst DC3000 expressing ATR39-1in grew to similar levels as the non-recognized allele ATR39-2 or empty vector control (Figure 4C). These findings suggest that amino acids E168/V169 in ATR39-2 are critical in evading recognition by the cognate R protein.

Figure 4. Amino acids E168/V169 abolish recognition of ATR39.

A) Alignment of the C-terminal regions of ATR39 alleles and their corresponding insertion/deletion constructs. E168/V169 are indicated by a triangle. B) Only alleles lacking E168/V169 trigger an HR when delivered by Pf0. The lower half of each leaf was inoculated with an empty vector control. Pictures were taken 24 hpi. Stars highlight positive HR. C) Pst DC3000 growth assay with indicated ATR39 insertion/deletion alleles. Significant differences as determined by Student's t-test are indicated by small letters (P<0.005). Experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results.

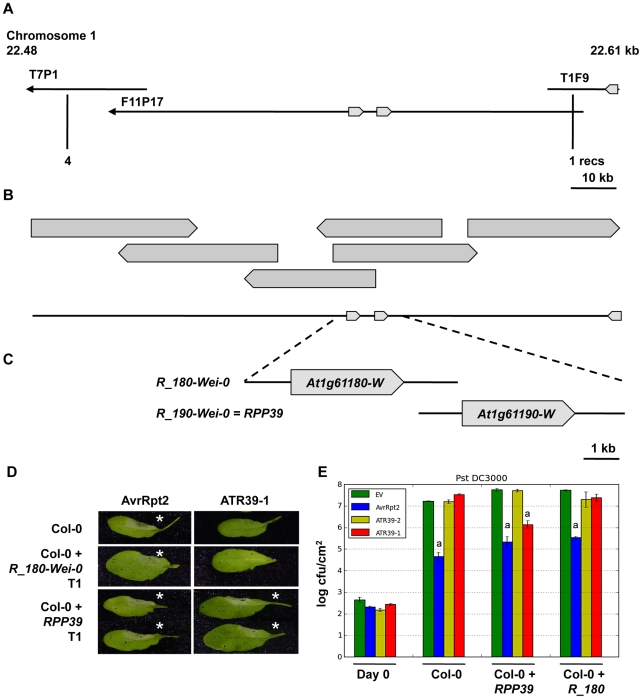

RPP39 is a member of a CC-NBS-LRR gene cluster

Resistance to Hpa strains is mediated by a number of RPP (Resistance to Peronospora parasitica) loci. In order to identify the RPP39 gene responsible for recognition of ATR39-1 we generated a cross between Wei-0 and Col-0 and found that recognition segregated as a single dominant locus in the F2 progeny. Using 886 F2 plants, we delineated the RPP39 locus to a 150 kilobase region on the bottom of chromosome 1. In Col-0 this region contains two homologous CC-NB-LRR genes with 91% identity arranged in a tandem repeat (At1g61180 and At1g61190). Because there is no sequence information available for Wei-0, we generated a fosmid library and identified six overlapping clones that span this region (Figure 5B). We sequenced the fosmids using Illumina next generation sequencing and found several rearrangements and a transposon insertion relative to the Col-0 sequence (Figure S4). Wei-0 also contains two CC-NBS-LRR genes at this locus, which were the most promising candidates for RPP39.

Figure 5. Map-based cloning of RPP39.

A) Map location of RPP39 on Col-0 BAC clones of Chromosome 1. Predicted NBS-LRR R genes are indicated as block arrows. Positions of the last flanking markers and numbers of recombinants are indicated below. B) Wei-0 fosmid contig spanning the 133 kb locus containing RPP39. C) Genomic clones of the R genes at the RPP39 locus used in functional analysis in transgenic Col-0 Arabidopsis. D) HR induced by ATR39-1 and AvrRpt2 in transgenic Arabidopsis Col-0 T1 transformed with the R gene candidates in C. The lower half of each leaf was inoculated with an empty vector control. Pictures were taken 24 hpi. Stars highlight positive HR. E) Pst DC3000 growth assay on select T2 transgenics containing R gene candidates. Significant differences as determined by Student's t-test are indicated by small letters (P<0.0003). Experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results.

We amplified genomic regions containing the two candidate R genes, R_180-Wei-0 (accession number JQ045574) and R_190-Wei-0 (accession number JQ045573) and transformed them into Arabidopsis Col-0 for complementation. Only transgenic plants containing the gene corresponding to the At1g61190 locus (R_190-Wei-0) developed an HR in response to ATR39-1 delivery, indicating that this gene is RPP39 (Figure 5D). Growth assays with Pst DC3000 expressing ATR39-1 performed on plants in the T2 generation confirmed these results as we observed reduction in bacterial growth only in plants containing the R_190-Wei-0/RPP39 transgene (Figure 5E).

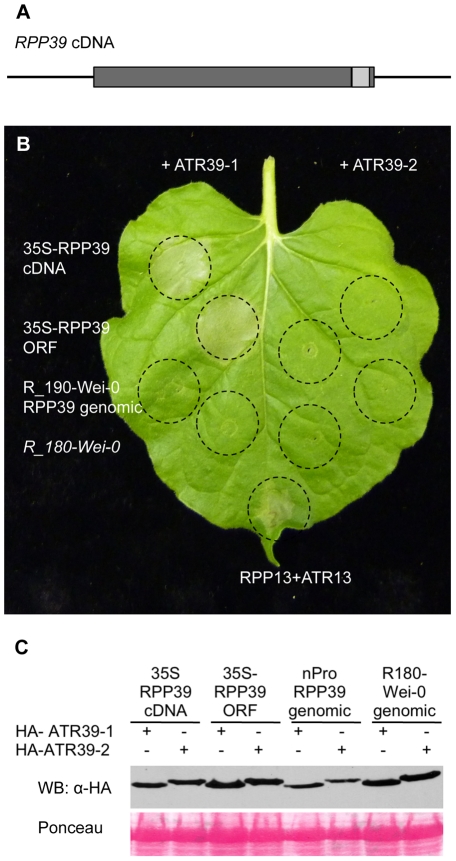

The predicted RPP39 coding region contains an intron close to the C-terminus, connecting a large N-terminal exon with a short C-terminal exon encoding the last 15 amino acids (Figure 6A). We amplified RPP39 from Wei-0 cDNA and confirmed the presence of this intron. In Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression experiments in Nicotiana benthamiana we showed that the RPP39 cDNA driven by the CaMV35S promoter is able to trigger ATR39-1 dependent HR (Figure 6B). Interestingly, expression of the genomic RPP39 clone in N. benthamiana was not sufficient to trigger HR, yet it was functional in transgenic Arabidopsis. Because a 35S driven clone of the genomic sequence of RPP39 is able to trigger HR (Figure 6B), we believe that the lack of responsiveness of the genomic RPP39 clone is probably due to low expression off the native promoter in the transient assay.

Figure 6. RPP39 cDNA triggers ATR39-1–dependent HR in transient expression assays in Nicotiana benthamiana.

A) Gene structure of RPP39. Promoter and terminator regions are indicated as black lines, exons are shown as dark grey boxes and the intron as a light grey box. B) Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression assay in N. benthamiana. The indicated RPP39 clones and R_180-Wei-0 were inoculated together with HA-ATR39-1 (left) and HA-ATR39-2 (right) at OD600 nm = 0.5 each. Inoculated areas are delineated by dashed lines. The picture was taken 72 hpi. RPP13 co-inoculated with ATR13Emco5 was included as positive control. C) Protein immunoblot of HA-ATR39 showing similar levels of protein expression. Samples were collected 24 hpi and probed with α-HA antibody. Ponceau staining is included to show equal loading of the samples.

RPP39 is very similar to its Col-0 paralogs, At1g61190 (NM_104800.1) and At1g61180 (NM_104799.3), with 86% identity at the nucleotide level and 81% to 87% at the amino acid level (Figure S5). The homologs are most divergent in the C-terminal LRR domain (Figure S6). The most closely related R proteins outside the RPP39 cluster are RPS5 (NP_172686.1), RFL1 (AAL65608.1) and RPS2 (AAA21874.1) with 50%, 49% and 27% identity to RPP39 at the amino acid level, respectively (Figure S5). Taken together, we identified a functional resistance gene as a member of small R gene cluster.

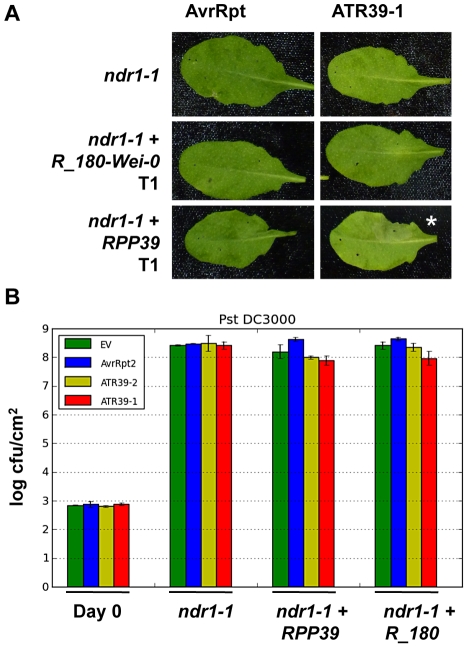

RPP39 requires NDR1 for full resistance

Non-specific disease resistance 1 (NDR1) is a common signaling gene required for CC-NBS-LRR mediated resistance functions [42]. Since RPP39 is similar to the resistance genes RPS2 and RPS5, both of which require NDR1, we investigated the involvement of NDR1 in RPP39 mediated resistance. We generated stable transgenic plants containing RPP39 or its non-functional paralog R180_Wei-0 in the ndr1 mutant background. RPP39 transgenic plants displayed no difference in their ability to trigger ATR39-1-dependent HR as compared to transgenics in Col-0 wild type background (Figure 7A). However, in Pst DC3000 growth assays we did not see a similar growth reduction in the ndr1 transgenics (Figure 7B). These results indicate that the ability of RPP39 to trigger HR is separable from complete disease resistance, and is reminiscent of RPM1, which displays similar NDR1 dependency [43].

Figure 7. NDR1 is required for full resistance but dispensable for HR mediated by RPP39.

A) Pf0 inoculation of T1 transgenic Arabidopsis ndr1 mutant plants transformed with the indicated R genes. The lower half of each leaf was inoculated with an empty vector control. Pictures were taken 24 hpi. Stars highlight positive HR. B) Pst DC3000 growth assay on select T2 transgenic ndr1 plants transformed with the indicated R gene candidates. Statistical analysis using Student's t-test identified no significant differences. Experiments were repeated at least twice with similar results.

Discussion

We have used a combination of computational prediction methods and phenotypic screening to identify a novel recognized effector from Hpa. Being an obligate biotroph, Hpa is currently not amenable to in depth genetic analysis, and cloning of the previously identified RxLR effectors ATR1 and ATR13 was a lengthy and cumbersome process [5], [7]. In our approach, we mined the Hpa genome for putative effector sequences and ranked them in a comparison with a Hidden Markov Model (HMM) generated based on the N-terminal conserved translocation domains of previously identified oomycete effectors. When we generated the HMM, all characterized effectors contained an RxLR and in our initial ranking we screened the HMM only against predicted RxLR effectors. Recently, Bailey et al. cloned and characterized ATR5 from Hpa strain Emoy2, the first recognized effector without a canonical RxLR sequence, suggesting that this motif can be modified [8]. In accordance with this, when screening the HMM against all annotated proteins in the final Hpa genome release [17], we also identified several non-RxLR variants within the top-scoring effector candidates, including ATR5 (data not shown). These findings suggest that our screen is by no means exhaustive and that more recognized effectors await characterization. When screening the HMM against the published annotation of the Hpa protein database, we also noticed that a few of our predicted effectors did not appear in the results because their annotated genes do not include the N-terminal translocation domains due to a difference in annotation of the translational start site.

Our choice of using the non-pathogenic P. fluorescens that does not normally trigger a response in Arabidopsis as a surrogate expression and delivery system allowed us to rapidly screen a large number of Arabidopsis ecotypes for novel recognition specificities. Interestingly, despite the fact that Hpa strains are predicted to contain between 10 and 20 avirulent effectors, according to association studies in the 1990s [44], in our set we only identified one novel effector that was able to trigger resistance in an Arabidopsis ecotype. Under our assay conditions and using our expression vectors we did not detect consistent phenotypes (either virulence or avirulence) for most of the tested effectors from the Emoy2 isolate of Hpa. Notably, in this study we compared the two delivery systems pEDV3 and pPsSP, which fuse the TTSS signal peptides from the bacterial effectors AvrRps4 and AvrRpm1, respectively, upstream of the Hpa effector [35], [36]. Intriguingly, ATR39-1 was functional when expressed as AvrRpm1 fusion in the pPsSP vector, but not as AvrRps4 fusion in the pEDV3 vector. ATR1, on the other hand, did not trigger responses when delivered as AvrRpm1 fusion protein in the pPsSP system and is only functional in the pEDV3 system. These results suggest that the choice of expression system can greatly influence the observed phenotypes and should be taken into account. Therefore, we cannot dismiss the possibility that several of the predicted effectors might be functional in different assay conditions or recognized by different Arabidopsis ecotypes not tested in this study. In a set of Arabidopsis ecotypes from the United Kingdom, where all currently available Hpa strains originate from, several ATR13 alleles were tested and were found to be recognized by RPP13 alleles in different ecotypes [45]. The fact that we did not observe prevalence of effector recognition in our subset of Arabidopsis ecotypes suggests that the co-evolution between pathogen and host may play an important role in this obligate biotroph interaction. We also screened various alleles of ATR1 and ATR13 on the Nordborg collection of Arabidopsis ecotypes [38] and found six ecotypes capable of recognizing ATR1Emoy2, including Ws-0 and Nd-1, but none that recognized ATR13Emoy2 [41]. Compared with the prevalence of recognition specificities for bacterial effectors such as AvrRpt2 or AvrPphB, which are recognized by RPS2 and RPS5 in more than half of the tested ecotypes [38], these results indicate a more dynamic effector repertoire in Hpa.

We identified two amino acids, E168 and V169, which abrogate recognition of ATR39-2. Deletion of these amino acids in ATR39-2 resulted in a gain-of-recognition phenotype while insertion of E168/V169 in ATR39-1 lead to loss-of-recognition by RPP39. It is possible that this insertion/deletion polymorphism alters the three dimensional structure of ATR39, thus disrupting the interaction with potential target proteins. Another possibility would be that the polymorphism alters putative enzymatic properties of ATR39. However, since the primary amino acid sequence of ATR39 is not homologous to any known protein, we can only speculate about the consequences of the insertion on the function of this protein. Experiments to determine the structure and to identify interacting proteins of ATR39 alleles will help elucidate the function of this novel effector.

The Arabidopsis ecotype Wei-0 exhibits an interesting resistance pattern: it is resistant against several tested bacterial pathogens but highly susceptible towards Hpa isolates ([40], this study). Intriguingly, despite being able to recognize ATR39-1 when delivered by a surrogate system, Wei-0 is not able to restrict growth of Hpa expressing ATR39-1. This finding is reminiscent of ATR1Emco5, which is recognized in the Arabidopsis ecotype Ws-0 by RPP1-WsB, but this recognition does not abrogate growth of Hpa in a natural infection. Additional Arabidopsis ecotypes recognizing ATR1Emco5 were recently identified, and these were also shown to support growth of Hpa isolate Emco5, indicating similar mechanisms in virulence may act in these interactions [41]. These data suggest that Hpa may contain a pathogenicity factor, perhaps another secreted effector, which prevents recognition of ATR1 in Emco5 or ATR39-1 in Emwa1 and Emoy2. Support for this hypothesis comes from a study on different alleles of the P. infestans effector ipiO/Avrblb1, where expression of one allele, ipiO4, was found to suppress resistance mediated by the ipiO1/Rblb1 interaction [46]. Alternative explanations for the lack of recognition in these instances could be inhibition of effector translocation to the host, mistimed expression of either effector or R gene or incomplete resistance mediated by the R gene that is not strong enough to contain the pathogen. Experiments aimed at investigating this interesting phenotype should yield important insight into Hpa virulence.

RPP39 is a member of a small cluster of CC-NBS-LRR genes, which is rapidly evolving through duplication and inversion events. A dominant mutation in the LRR domain of an RPP39 homolog in Ws-0, uni-1D (named after the Japanese word for sea urchin because of its morphological phenotype) was found to display several defects in growth and hormone signaling which are often seen with gain of function R proteins such as SNC1 [47], [48]. Interestingly, the uni-1D phenotype was not dependent on NDR1 [47]. We found that RPP39 requires NDR1 to fully suppress P. syringae growth, but activates hypersensitive cell death independently of NDR1. In future, it will be interesting to more completely dissect the RPP39 signaling pathway.

Taken together, our results show the feasibility of employing computational predictions in the identification of functional pathogen effectors. In combination with classical genetic methods it was possible to determine function for one member of the large family of predicted R proteins in Arabidopsis. Preliminary data on several polymorphic effectors from our HMM priority list indicate that Hpa isolates other than Emoy2 contain functional/recognized effector alleles, which will be further pursued and may lead to the identification of additional R genes, the analysis of which will further advance our understanding of R protein signaling.

Materials and Methods

HMM prediction of effectors from Hpa Emoy2

A set of confirmed oomycete effectors and their close homologs used for the bioinformatic analyses included 43 sequences from Phytophthora species and Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis and has been previously published [21]. The Signal Peptide and RxLR portion of these sequences (positions 1 to 90) were aligned using the muscle algorithm [49]. The HMM building, calibration, and searches were performed using the HMMER software package with hmmbuild, hmmcalibrate, and hmmsearch algorithms, respectively (http://hmmer.org/). The HMM search included only one iteration.

Cloning of effectors

The predicted effectors were PCR amplified without signal peptide from Hpa strain Emoy2 DNA (obtained from Jonathan Jones) using primers listed in Table S2 and cloned into the pENTR/D-Topo vector (Invitrogen). The insert sequences were verified and the effectors recombined with LR clonase (Invitrogen) into the binary Pseudomonas expression vector pPsSP [35]. The pEDV3 clones of effectors were generated using restriction digests with SalI/BamHI or compatible restriction enzymes. Site-directed mutants ATR39-1in and ATR39-2del were generated in pENTR using the QuikChange Lightning kit (Agilent) and primers listed in Table S2, and recombined with binary vectors as above. For transient expression in Nicotiana benthamiana, ATR39 alleles were recombined into pEarleygate201 containing a 35S promoter and N-terminal HA-tag [50]. The fasta files containing the amino acid and nucleotide sequences of the predicted effectors are available online as Text S1 and Text S2.

Plant growth conditions

A. thaliana plants were grown on soil in controlled growth chambers at short days (8 hrs light/16 hrs dark cycle) and 24°C. Transgenic Arabidopsis were surface sterilized and selected on MS medium with the appropriate antibiotics. For Hpa growth assays the plants were transferred to a growth chamber with 18°C and 100% humidity.

Pathogen assays

Hpa isolates were obtained from E. Holub (Maks9), X. Dong (Emwa1), J. McDowell (Emoy2, Emco5), X. Li (Cala2) and J. Jones (Noco2) and maintained on susceptible Arabidopsis plants as previously described [27]. For disease assays, conidiospores were harvested by vortexing in water, adjusted to 5*104 spores/mL and sprayed on 2-week-old Arabidopsis seedlings. The infected plants were kept in growth chambers at 18°C and 100% humidity for 7 days before being stained with lactophenol-trypan blue [40] to assess Hpa growth or resistance.

Pseudomonas fluorescens strains were grown on Pseudomonas agar with glycerol (PAG) supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics. For HR assays, Pf0 strains were grown on PAG plates for 2 days and resuspended in 10 mM MgCl2 to OD600 nm = 1 (corresponding to 109 cfu/mL). Bacteria were inoculated into halves of pierced Arabidopsis leaves using a blunt syringe. Visible HR symptoms were scored 24 hours post-inoculation. Pseudomonas growth assays were performed as described previously [51].

Mapping and sequencing of the RPP39 locus

Markers and probes used in map-based cloning of RPP39 are summarized in Table S3. A fosmid library of Wei-0 was generated following the instructions in the copy control fosmid kit (Epicentre) and screened with Digoxigenin-labeled probes using the DIG DNA labeling and detection kit (Roche). To sequence the RPP39 region, 350 bp-sized fragments of overlapping fosmids were sequenced in a 60 bp paired-end sequencing run on an Illumina G2. Reads were cleaned for vector sequences and bacterial contamination using MAQ (http://maq.sourceforge.net/) and assembled using CLC genomics workbench (http://www.clcbio.com/). Gaps and misassembled regions were filled in using Sanger sequencing data.

Cloning and expression of RPP39

Genomic fragments of about 6 kb length, containing RPP39 (R190_Wei-0) or R180_Wei-0 were amplified using primers specified in Table S2 and introduced into pENTR/D-Topo (Invitrogen). Sequences were confirmed and the fragments recombined into pEarleygate301 [50] for expression in Agrobacterium. The RPP39 cDNA clone was amplified from Wei-0 cDNA and recombined into pEarleygate100 containing a 35 S promoter [50]. The binary vectors were mobilized into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 with tri-parental mating and used to transform Arabidopsis plants following the floral dip protocol [52]. Presence of the transgene in Arabidopsis was confirmed by PCR. Transient expression experiments in N. benthamiana were performed as previously described [35]. Protein expression was determined by Western blotting as described [31].

RNA extraction and RT–PCR

RNA was extracted from Arabidopsis seedlings infected with Hpa using the RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed using Superscript III (Invitrogen) and oligo-dT primers. RT-PCR was performed with gene specific primers (Table S2) and 25 amplification cycles.

Supporting Information

Growth assay with Pseudomonas syringae pv. maculicola ES4326. Bacterial titer was determined at 0 and 4 days post-infection. Significant differences as determined by Student's t-test are indicated by small letters (P<0.0001).

(TIF)

The effector domain of ATR39-1 is sufficient to trigger HR in Wei-0. A) Domain structure of ATR39. Numbers indicate amino acid residues. B) Pf0 inoculations of indicated ecotypes with ATR39-1 constructs. The lower halves of the leaves are inoculated with empty vector controls. Pictures were taken 24 hpi.

(TIF)

ATR39-1 expression timecourse during Hpa Emoy2 infection. RT-PCR was performed on RNA extracted from infected tissue at the indicated timepoints. Hpa Actin was included as control for Hpa growth.

(TIF)

Dot matrix view of a pairwise alignment between the RPP39 region in Wei-0 and Col-0 showing similarity between the two sequences. The genomic regions were aligned with Blast (blast2seq). Regions with gene duplications are visible at 20 k (corresponding to a gene family) and 70–80 k (corresponding to the R gene locus containing RPP39). Two gaps in the alignment (indicated by arrows) correspond to a transposable element in Wei-0 (at 64 k) and a translocation from Chromosome 3 (at 120 k).

(TIF)

Pairwise comparison of RPP39 with its homologs in Col-0 and Wei-0 and the more distantly related RPS5, RFL1 and RPS2. Depicted are % identities between the nucleotide (upper diagonal) and amino acid (lower diagonal) sequences of RPP39, its homologs R180_Wei-0, At1g61180_Col-0 and At1g61190_Col-0 as well as the R proteins RPS5, RFL1 and RPS2. The comparison is based on ClustalW alignments generated with CLC genomics workbench.

(TIF)

Amino acid alignment of RPP39 and its homologs from Wei-0 (R180-Wei-0) and Col-0 (At1g61180 and At1g61190). The alignment was performed using ClustalW and shaded in CLC genomics workbench.

(TIF)

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes used in this study.

(DOC)

Primers used in this study.

(DOC)

Markers and probes used to map RPP39.

(DOC)

Fasta formatted amino acid sequences of 18 top-scoring predicted effectors from Hpa strain Emoy2. The predicted signal peptide (by SignalP3.0) and RxLR motif are highlighted in blue and red, respectively.

(DOC)

Fasta formatted nucleotide sequences of the top scoring effectors. Signal peptide sequences (not included in the cloned effectors) are highlighted in blue.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank Xinnian Dong, Xin Li, Jonathan Jones, Eric Holub, and John McDowell for sharing Hpa strains and DNA. We are grateful for helpful discussions to the members of the Staskawicz lab.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

This work was funded by NSF 2010 grant 0726229. SG was supported by a Schrödinger post-doctoral fellowship of the Austrian Science Foundation (FWF). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Nishimura MT, Dangl JL. Arabidopsis and the plant immune system. Plant J. 2010;61:1053–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04131.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schornack S, Huitema E, Cano LM, Bozkurt TO, Oliva R, et al. Ten things to know about oomycete effectors. Mol Plant Pathol. 2009;10:795–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chisholm ST, Coaker G, Day B, Staskawicz BJ. Host-microbe interactions: shaping the evolution of the plant immune response. Cell. 2006;124:803–814. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammond-Kosack KE, Jones JD. Resistance gene-dependent plant defense responses. Plant Cell. 1996;8:1773–1791. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.10.1773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rehmany AP, Gordon A, Rose LE, Allen RL, Armstrong MR, et al. Differential recognition of highly divergent downy mildew avirulence gene alleles by RPP1 resistance genes from two Arabidopsis lines. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1839–1850. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.031807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shan W, Cao M, Leung D, Tyler BM. The Avr1b locus of Phytophthora sojae encodes an elicitor and a regulator required for avirulence on soybean plants carrying resistance gene Rps1b. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2004;17:394–403. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2004.17.4.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen RL, Bittner-Eddy PD, Grenville-Briggs LJ, Meitz JC, Rehmany AP, et al. Host-parasite coevolutionary conflict between Arabidopsis and downy mildew. Science. 2004;306:1957–1960. doi: 10.1126/science.1104022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey K, Cevik V, Holton N, Byrne-Richardson J, Sohn KH, et al. Molecular cloning of ATR5(Emoy2) from Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis, an avirulence determinant that triggers RPP5-mediated defense in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2011;24:827–838. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-12-10-0278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong MR, Whisson SC, Pritchard L, Bos JI, Venter E, et al. An ancestral oomycete locus contains late blight avirulence gene Avr3a, encoding a protein that is recognized in the host cytoplasm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:7766–7771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500113102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chou S, Krasileva KV, Holton JM, Steinbrenner AD, Alber T, et al. Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis ATR1 effector is a repeat protein with distributed recognition surfaces. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 108:13323–13328. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109791108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boutemy LS, King SR, Win J, Hughes RK, Clarke TA, et al. Structures of Phytophthora RXLR effector proteins: a conserved but adaptable fold underpins functional diversity. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:35834–35842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.262303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yaeno T, Li H, Chaparro-Garcia A, Schornack S, Koshiba S, et al. Phosphatidylinositol monophosphate-binding interface in the oomycete RXLR effector AVR3a is required for its stability in host cells to modulate plant immunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:14682–14687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106002108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Win J, Krasileva KV, Kamoun S, Shirasu K, Staskawicz BJ, et al. Sequence divergent RXLR effectors share a structural fold conserved across plant pathogenic oomycete species. PLoS Pathog. 2011 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002400. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhattacharjee S, Hiller NL, Liolios K, Win J, Kanneganti TD, et al. The malarial host-targeting signal is conserved in the Irish potato famine pathogen. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e50. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grouffaud S, van West P, Avrova AO, Birch PR, Whisson SC. Plasmodium falciparum and Hyaloperonospora parasitica effector translocation motifs are functional in Phytophthora infestans. Microbiology. 2008;154:3743–3751. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/021964-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haas BJ, Kamoun S, Zody MC, Jiang RH, Handsaker RE, et al. Genome sequence and analysis of the Irish potato famine pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Nature. 2009;461:393–398. doi: 10.1038/nature08358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baxter L, Tripathy S, Ishaque N, Boot N, Cabral A, et al. Signatures of adaptation to obligate biotrophy in the Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis genome. Science. 2010;330:1549–1551. doi: 10.1126/science.1195203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tyler BM, Tripathy S, Zhang X, Dehal P, Jiang RH, et al. Phytophthora genome sequences uncover evolutionary origins and mechanisms of pathogenesis. Science. 2006;313:1261–1266. doi: 10.1126/science.1128796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cunnac S, Lindeberg M, Collmer A. Pseudomonas syringae type III secretion system effectors: repertoires in search of functions. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009;12:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang RH, Tripathy S, Govers F, Tyler BM. RXLR effector reservoir in two Phytophthora species is dominated by a single rapidly evolving superfamily with more than 700 members. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4874–4879. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709303105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Win J, Morgan W, Bos J, Krasileva KV, Cano LM, et al. Adaptive evolution has targeted the C-terminal domain of the RXLR effectors of plant pathogenic oomycetes. Plant Cell. 2007;19:2349–2369. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.051037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schornack S, van Damme M, Bozkurt TO, Cano LM, Smoker M, et al. Ancient class of translocated oomycete effectors targets the host nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:17421–17426. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008491107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Caillaud MC, Piquerez SJ, Fabro G, Steinbrenner J, Ishaque N, et al. Subcellular localization of the Hpa RxLR effector repertoire identifies the extrahaustorial membrane-localized HaRxL17 that confers enhanced plant susceptibility. Plant J. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04787.x. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cabral A, Stassen JH, Seidl MF, Bautor J, Parker JE, et al. Identification of Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis transcript sequences expressed during infection reveals isolate-specific effectors. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vleeshouwers VG, Rietman H, Krenek P, Champouret N, Young C, et al. Effector genomics accelerates discovery and functional profiling of potato disease resistance and Phytophthora infestans avirulence genes. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oh SK, Young C, Lee M, Oliva R, Bozkurt TO, et al. In planta expression screens of Phytophthora infestans RXLR effectors reveal diverse phenotypes, including activation of the Solanum bulbocastanum disease resistance protein Rpi-blb2. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2928–2947. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.068247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holub EB, Brose E, Tor M, Clay C, Crute IR, et al. Phenotypic and genotypic variation in the interaction between Arabidopsis thaliana and Albugo candida. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1995;8:916–928. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-8-0916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slusarenko AJ, Schlaich NL. Downy mildew of Arabidopsis thaliana caused by Hyaloperonospora parasitica (formerly Peronospora parasitica). Mol Plant Pathol. 2003;4:159–170. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2003.00166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meyers BC, Kozik A, Griego A, Kuang H, Michelmore RW. Genome-wide analysis of NBS-LRR-encoding genes in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2003;15:809–834. doi: 10.1105/tpc.009308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bomblies K, Lempe J, Epple P, Warthmann N, Lanz C, et al. Autoimmune response as a mechanism for a Dobzhansky-Muller-type incompatibility syndrome in plants. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krasileva KV, Dahlbeck D, Staskawicz BJ. Activation of an Arabidopsis resistance protein is specified by the in planta association of its leucine-rich repeat domain with the cognate oomycete effector. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2444–2458. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.075358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bittner-Eddy PD, Beynon JL. The Arabidopsis downy mildew resistance gene, RPP13-Nd, functions independently of NDR1 and EDS1 and does not require the accumulation of salicylic acid. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2001;14:416–421. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.2001.14.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finn RD, Tate J, Mistry J, Coggill PC, Sammut SJ, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D281–288. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kale SD, Tyler BM. Assaying effector function in planta using double-barreled particle bombardment. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;712:153–172. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-998-7_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rentel MC, Leonelli L, Dahlbeck D, Zhao B, Staskawicz BJ. Recognition of the Hyaloperonospora parasitica effector ATR13 triggers resistance against oomycete, bacterial, and viral pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:1091–1096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711215105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sohn KH, Lei R, Nemri A, Jones JD. The downy mildew effector proteins ATR1 and ATR13 promote disease susceptibility in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2007;19:4077–4090. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.054262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas WJ, Thireault CA, Kimbrel JA, Chang JH. Recombineering and stable integration of the Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae 61 hrp/hrc cluster into the genome of the soil bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1. Plant J. 2009;60:919–928. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.03998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aranzana MJ, Kim S, Zhao K, Bakker E, Horton M, et al. Genome-wide association mapping in Arabidopsis identifies previously known flowering time and pathogen resistance genes. PLoS Genet. 2005;1:e60. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0010060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Allen RL, Meitz JC, Baumber RE, Hall SA, Lee SC, et al. Natural variation reveals key amino acids in a downy mildew effector that alters recognition specificity by an Arabidopsis resistance gene. Mol Plant Pathol. 2008;9:511–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2008.00481.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koch E, Slusarenko A. Arabidopsis is susceptible to infection by a downy mildew fungus. Plant Cell. 1990;2:437–445. doi: 10.1105/tpc.2.5.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Krasileva K, Zheng C, Leonelli L, Goritschnig S, Dahlbeck D, et al. Global analysis of Arabidopsis/downy mildew interactions reveals prevalence of incomplete resistance and rapid evolution of pathogen recognition. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aarts N, Metz M, Holub E, Staskawicz BJ, Daniels MJ, et al. Different requirements for EDS1 and NDR1 by disease resistance genes define at least two R gene-mediated signaling pathways in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10306–10311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.10306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shapiro AD, Zhang C. The role of NDR1 in avirulence gene-directed signaling and control of programmed cell death in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001;127:1089–1101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coates ME, Beynon JL. Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis as a pathogen model. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2010;48:329–345. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-094422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hall SA, Allen RL, Baumber RE, Baxter LA, Fisher K, et al. Maintenance of genetic variation in plants and pathogens involves complex networks of gene-for-gene interactions. Mol Plant Pathol. 2009;10:449–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2009.00544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Halterman DA, Chen Y, Sopee J, Berduo-Sandoval J, Sanchez-Perez A. Competition between Phytophthora infestans effectors leads to increased aggressiveness on plants containing broad-spectrum late blight resistance. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Igari K, Endo S, Hibara K, Aida M, Sakakibara H, et al. Constitutive activation of a CC-NB-LRR protein alters morphogenesis through the cytokinin pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2008;55:14–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Y, Goritschnig S, Dong X, Li X. A gain-of-function mutation in a plant disease resistance gene leads to constitutive activation of downstream signal transduction pathways in suppressor of npr1-1, constitutive 1. Plant Cell. 2003;15:2636–2646. doi: 10.1105/tpc.015842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Earley KW, Haag JR, Pontes O, Opper K, Juehne T, et al. Gateway-compatible vectors for plant functional genomics and proteomics. Plant J. 2006;45:616–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Day B, Dahlbeck D, Staskawicz BJ. NDR1 interaction with RIN4 mediates the differential activation of multiple disease resistance pathways in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18:2782–2791. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.044693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Growth assay with Pseudomonas syringae pv. maculicola ES4326. Bacterial titer was determined at 0 and 4 days post-infection. Significant differences as determined by Student's t-test are indicated by small letters (P<0.0001).

(TIF)

The effector domain of ATR39-1 is sufficient to trigger HR in Wei-0. A) Domain structure of ATR39. Numbers indicate amino acid residues. B) Pf0 inoculations of indicated ecotypes with ATR39-1 constructs. The lower halves of the leaves are inoculated with empty vector controls. Pictures were taken 24 hpi.

(TIF)

ATR39-1 expression timecourse during Hpa Emoy2 infection. RT-PCR was performed on RNA extracted from infected tissue at the indicated timepoints. Hpa Actin was included as control for Hpa growth.

(TIF)

Dot matrix view of a pairwise alignment between the RPP39 region in Wei-0 and Col-0 showing similarity between the two sequences. The genomic regions were aligned with Blast (blast2seq). Regions with gene duplications are visible at 20 k (corresponding to a gene family) and 70–80 k (corresponding to the R gene locus containing RPP39). Two gaps in the alignment (indicated by arrows) correspond to a transposable element in Wei-0 (at 64 k) and a translocation from Chromosome 3 (at 120 k).

(TIF)

Pairwise comparison of RPP39 with its homologs in Col-0 and Wei-0 and the more distantly related RPS5, RFL1 and RPS2. Depicted are % identities between the nucleotide (upper diagonal) and amino acid (lower diagonal) sequences of RPP39, its homologs R180_Wei-0, At1g61180_Col-0 and At1g61190_Col-0 as well as the R proteins RPS5, RFL1 and RPS2. The comparison is based on ClustalW alignments generated with CLC genomics workbench.

(TIF)

Amino acid alignment of RPP39 and its homologs from Wei-0 (R180-Wei-0) and Col-0 (At1g61180 and At1g61190). The alignment was performed using ClustalW and shaded in CLC genomics workbench.

(TIF)

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes used in this study.

(DOC)

Primers used in this study.

(DOC)

Markers and probes used to map RPP39.

(DOC)

Fasta formatted amino acid sequences of 18 top-scoring predicted effectors from Hpa strain Emoy2. The predicted signal peptide (by SignalP3.0) and RxLR motif are highlighted in blue and red, respectively.

(DOC)

Fasta formatted nucleotide sequences of the top scoring effectors. Signal peptide sequences (not included in the cloned effectors) are highlighted in blue.

(DOC)