Abstract

In this study, we investigated the significance of β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) in age-related impaired insulin secretion and glucose homeostasis. We characterized the metabolic phenotype of β2AR-null C57Bl/6N mice (β2AR−/−) by performing in vivo and ex vivo experiments. In vitro assays in cultured INS-1E β-cells were carried out in order to clarify the mechanism by which β2AR deficiency affects glucose metabolism. Adult β2AR−/− mice featured glucose intolerance, and pancreatic islets isolated from these animals displayed impaired glucose-induced insulin release, accompanied by reduced expression of peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor (PPAR)γ, pancreatic duodenal homeobox-1 (PDX-1), and GLUT2. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of human β2AR rescued these defects. Consistent effects were evoked in vitro both upon β2AR knockdown and pharmacologic treatment. Interestingly, with aging, wild-type (β2AR+/+) littermates developed impaired insulin secretion and glucose tolerance. Moreover, islets from 20-month-old β2AR+/+ mice exhibited reduced density of β2AR compared with those from younger animals, paralleled by decreased levels of PPARγ, PDX-1, and GLUT2. Overexpression of β2AR in aged mice rescued glucose intolerance and insulin release both in vivo and ex vivo, restoring PPARγ/PDX-1/GLUT2 levels. Our data indicate that reduced β2AR expression contributes to the age-related decline of glucose tolerance in mice.

Impairment of glucose metabolism with age represents a major determinant of type 2 diabetes epidemics within the elderly population. The molecular mechanisms underlying these changes have not been fully elucidated and are likely attributable to multiple causes (1,2). Aging per se is associated with a continuous decrease in basal insulin release (3). The size of this effect is sufficient to increase the likelihood of developing abnormalities in glucose tolerance and even overt diabetes (2,4). The consequence of aging on glucose tolerance occurs in different species, having been identified in rats (5,6) as well as in humans (4,7,8). However, why insulin secretion deteriorates with aging remains a moot point.

The noradrenergic system provides fine-tuning to the endocrine pancreas activity through the function of α- and β-adrenergic receptors (ARs) (9,10). The reciprocal regulation exerted by insulin and the adrenergic system has been well documented through a large number of studies (11–13). More recent evidence shows that mice with simultaneous deletion of the three known genes encoding the βARs (β1, β2, and β3) present a phenotype characterized by impaired glucose tolerance (14). Studies with β2AR agonists further suggest that the β2AR may play an important role in regulating insulin secretion (15). In addition, different human polymorphisms in the β2AR gene have been associated with higher fasting insulin levels (16). Nevertheless, the impact of the β2AR subtype on glucose tolerance and insulin secretion is still unclear.

Similar to glucose tolerance, βAR function and responsiveness deteriorate with aging (17–20), but the precise mechanisms involved are unknown. However, current evidence indicates that aging may downregulate βAR signaling, β2AR in particular, by decreasing the expression of molecular components of the adrenergic signaling machinery (21–24). We have therefore hypothesized that age-dependent alterations in βAR function impair glucose-regulated insulin release by the pancreatic β-cells and may contribute to deterioration of glucose tolerance. To test this hypothesis, we explored the consequences of β2AR knockout on insulin secretion in mice and investigated the significance of the age-related changes in β2AR function with regard to glucose tolerance.

RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

In vivo studies.

We studied male mice with a homozygous deletion of the β2AR gene (β2AR−/−) and backcrossed >12 generations onto C57Bl/6N background. Founders were provided by Brian Kobilka (Stanford University, Stanford, CA) (25). Wild-type littermates (β2AR+/+) were used as controls. The animals were housed in a temperature-controlled (22°C) room with a 12-h light/dark cycle in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH publication no. 85-23, revised 1996), and experiments were approved by the ethics committee of the Federico II University. Mice were killed by cervical dislocation. Pancreata were excised and collected rapidly after mice were killed. Samples were weighted, fixed by immersion in 4% paraformaldehyde for histology, homogenized for determination of total insulin content, or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C for subsequent analyses. For determination of insulin or glucagon content, pancreatic tissue was homogenized in acid ethanol and extracted at 4°C overnight. The acidic extracts were dried by vacuum, reconstituted, and subjected to insulin and glucagon measurements.

Glucose tolerance test and assessment of insulin secretion.

Glucose tolerance test (GTT) was performed as previously described (9,26). Briefly, mice were fasted overnight and then injected with glucose (2 g/kg i.p.). Blood glucose was measured by tail bleeding (Glucose Analyzer II; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) at indicated time points. The assessment of insulin secretion before and during glucose challenge was performed as previously described (9,27). Blood from the mandibular vein of overnight-fasted mice was collected at the indicated time for serum insulin assessment. The evaluation of glucagon secretion was performed by collecting blood from the mandibular vein of random-fed mice before and after injection of insulin (0.75 IU/kg i.p.). Serum insulin and plasma glucagon were assayed by radioimmunoassay (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Histological analysis.

Immunohistochemistry was carried out on paraffin sections using the H38 rabbit insulin antibody or the N-17 goat glucagon antibody (1:200 dilution; both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Goat anti-rabbit serum coupled with peroxidase (Immunotech, Marseille, France) was used as secondary antibody. After primary antibody exposure, slides were incubated with biotinylated anti-rabbit or anti-goat IgG and peroxidase-labeled streptavidin (Dako Corporation). All reactions were revealed with diaminobenzidine. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and mounted (28,29).

Ex vivo studies

Isolation of mouse pancreatic islets.

Islets of Langerhans were isolated by collagenase digestion (26,30). In brief, mice were killed as described above, the fur was soaked with ethanol, and the abdomen was opened to locate and excise the pancreas. Digestion was completed with collagenase P (Roche Applied Sciences, Penzberg, Germany) in a shaking water bath (37°C) for 5–8 min. The digested pancreas was treated with DNase I (New England BioLabs, Ipswich, MA). The islets were hand-picked under a stereomicroscope using a syringe with a 25-gauge needle and cultured at 37°C with 95% air and 5% CO2 in complete RPMI-1640 supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated FBS, 1 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, 50 μmol/L 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mmol/L glutamine, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 100 units/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin (all from Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) as previously described (31,32).

Evaluation of insulin secretion.

Isolated islets were preincubated at 37°C for 30 min in Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer (120 mmol/L NaCl, 4.7 mmol/L KCl, 1.2 mmol/L MgSO4, 1.2 mmol/L KH2PO4, 2.4 mmol/L CaCl2, and 20 mmol/L NaHCO3) supplemented with 10 mmol/L HEPES and 0.2% BSA and gassed with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2 containing 2 mmol/L glucose. Twenty size-matched islets collected in each tube were incubated for 1 h in a 37°C water bath with 500 μL Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer medium containing 2.8 mmol/L glucose, 16.7 mmol glucose, or 2.8 mmol/L glucose plus 33 mmol/L KCl. Islets were then pelleted by centrifugation (9,000g, 2 min, 4°C), and supernatants were collected for insulin secretion. Insulin concentrations were determined using radioimmunoassay (31).

Adenovirus-mediated reinstallation of β2AR in vivo and ex vivo.

Twenty-month-old β2AR+/+ mice were anesthetized by isoflurane (4%) inhalation and maintained by mask ventilation (isoflurane 1.8%) (28). After laparotomy, we identified and mobilized the distal pancreas and we performed two injections (50 μL each) of adenovirus (7 × 1010 plaque-forming units [pfu]/mouse) using a 30-gauge needle. Given the high homology between the human and mouse β2AR (33) and the validated use of the adenoviruses expressing the human β2AR (Adβ2AR) for in vivo gene transfer (34–36), we used the human Adβ2AR or, as control, an empty expression cassette derived from pcDNA3.2/V5/GW/D-TOPO (AdEmpty), kindly provided by Walter J. Koch, Jefferson University (Philadelphia, PA). Finally, abdominal incision was quickly closed in layers using 3–0 silk suture, and animals were observed and monitored until recovery. Isolated islets were infected (12 × 104 pfu/islet) with Adβ2AR or AdEmpty. After 3 h incubation with the adenoviruses, pancreatic islets were incubated with fresh medium and under normoxic conditions (95% air, 5% CO2) at 37°C for 24 h.

In vitro studies.

The INS-1E β-cells (provided by P. Maechler, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland), derived and selected from the parental rat insulinoma INS-1 β-cell line, were maintained in monolayer culture in RPMI-1640 medium as described above for the ex vivo experiments. For the insulin secretion assays, cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 105 cells/cm2 for at least 96 h before use (31). Transient transfection of the PPARγ cDNA and control empty plasmid was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) (37). We also tested the effects of the specific pharmacological β2AR antagonist ICI 118.551 (0.1 µmol/L) or agonist (1 µmol/L fenoterol) (both from Sigma-Aldrich) (36).

Short hairpin RNA design, generation, and transfection and radioligand-binding assay.

Stealth short hairpin (sh)RNA oligoribonucleotides against β2AR and scramble were designed (sequences and efficiency shown in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2, respectively) and then synthesized by Invitrogen. The shRNA hairpin configuration is cleaved by the cellular machinery into small interfering RNA, which is then bound to the RNA-induced silencing complex. This complex binds to and cleaves mRNAs that match the small interfering RNA that is bound to it. We transfected INS-1E β-cells with 100 nmol/L sh-β2AR RNA or sh-scramble RNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Assays were performed at least 3 days after shRNA transfection. Membrane fractions from pancreatic tissue, isolated islets, and INS-1E β-cells were used for radioligand-binding studies to assess the density of ARs as previously described and validated (35,36,38,39).

Real-time RT-PCR analysis.

Total cellular RNA was isolated from INS-1E β-cells, isolated islets, and pancreatic tissue samples with the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, as previously described (31,40). PCRs were analyzed using SYBR Green mix (Invitrogen). Reactions were performed in triplicate using Platinum SYBR Green qPCR Super-UDG by means of an iCycler IQ multicolor Real Time PCR Detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Cyclophilin was used as an internal standard. Primer sequences are reported in Supplementary Table 2.

Immunoblotting.

Immunoblot analysis was performed as previously described (31,37). Blots were probed with mouse monoclonal antibodies against adenylate cyclase type VI (AC-VI) (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), pancreatic and duodenal homeobox (PDX)-1, GLUT2, peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor (PPAR)γ, G-protein–coupled receptor (GRK)2, G protein αs (Gαs), clathrin heavy chain, and actin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Experiments were performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. Membrane extracts were obtained as previously described (29,38). Data are presented as arbitrary units using actin as internal control (clathrin heavy chain for membrane extracts) as indicated.

Measurement of cAMP production in vitro and ex vivo.

Intracellular content of cAMP was determined using a cAMP 125I-scintillation proximity assay (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, we used 20 size-matched islets (for the ex vivo assays) and 4,000 cells/well INS-1E (for the in vitro assays). Islets and β-cells were washed once and preincubated at 37°C in HEPES-buffered Krebs-Ringer solution containing 1 mmol/L glucose and 0.5 mmol/L isobutylmethylxanthine (a phosphodiesterase inhibitor) for 1 h and incubated for another 15 min in the same buffer with or without 100 μmol/L forskolin (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH), 3 mmol/L NaF (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA), or 1 μmol/L isoproterenol (Tocris Bioscience, Ellisville, MO). The reaction was stopped by addition of 50 mmol/L HCl and neutralized with NaOH. The cAMP levels were normalized to the protein concentration.

Statistical analysis.

All data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical differences were determined by one-way or two-way ANOVA as appropriate, and Bonferroni post hoc testing was performed when applicable. A P value <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (version 5.01; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA).

RESULTS

Metabolic phenotype of β2AR−/− mouse.

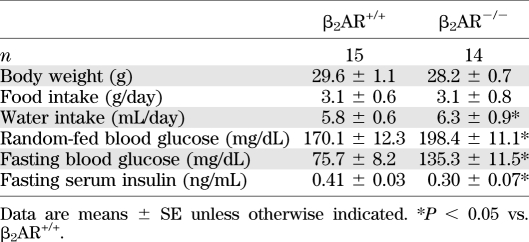

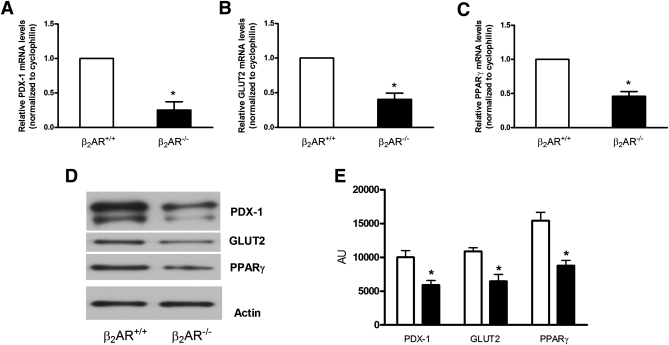

To investigate in vivo the relevance of the β2AR gene in the regulation of insulin secretion, we compared the metabolic phenotype of adult (6 months old) β2AR−/− and β2AR+/+ mice. Blood glucose was significantly higher in the null mice compared with that in their wild-type littermates both upon fasting and under random feeding conditions (Table 1). In addition, their fasting serum insulin levels were significantly reduced (Table 1). Upon glucose loading (GTT), the β2AR−/− mice displayed a marked reduction in glucose tolerance (Fig. 1A and B). In β2AR+/+ mice, we observed a threefold increase in insulin secretion 3 min after intraperitoneal glucose injection, presumably corresponding with the peak of first-phase insulin release. This was followed by a decrease at 10 min and then a gradual increase over 30 min that may indicate a second-phase response (27,41).

TABLE 1.

Metabolic characteristics of adult (6 months old) wild-type and knockout mice

FIG. 1.

Metabolic profile of β2AR−/− mice. Six-month-old β2AR−/− mice and their wild-type littermates (β2AR+/+) were fasted for 16 h and subjected to intraperitoneal glucose loading (2 g/kg body weight). Blood glucose (A and B) and serum insulin (C and D) were monitored for 120 min after glucose administration (n = 14–18 animals per group). β2AR−/− mice displayed glucose intolerance (A) and impaired insulin secretion (C). We calculated the AUC from glucose (B) and insulin excursion (D) curves. Peak insulin–to–peak glucose ratio (E) represents β-cell function, as better described in research design and methods. Bars represent means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. β2AR+/+, Bonferroni post hoc test. AUC, area under the curve.

In β2AR−/− mice, the early phase of insulin secretory response to glucose was reduced by more than twofold. The late response was also significantly impaired in the β2AR−/− compared with β2AR+/+ mice (Fig. 1C and D). The peak insulin–to–peak glucose ratio was also decreased (Fig. 1E), further indicating impaired insulin response to hyperglycemia in the null mice.

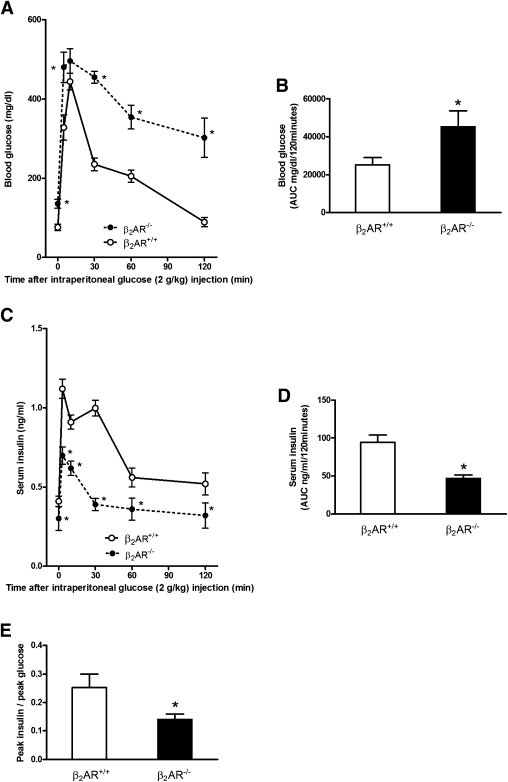

To investigate whether the alterations in glucose tolerance identified in the β2AR−/− mice were contributed by deranged glucagon release, we further measured blood glucose and plasma glucagon levels 30 min after insulin administration. Indeed, insulin administration determines a fall in blood glucose and a counterregulatory rise in plasma glucagon (2,30). However, β2AR−/− and β2AR+/+ mice exhibited comparable glucose and glucagon responses to insulin administration (Supplementary Fig. 1A and B). Pancreatic islet histology also did not show any significant difference in these mice (Fig. 2A), similar to total insulin and glucagon pancreatic content (Fig. 2B and C).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of β2AR+/+ and β2AR −/− pancreatic islets. Immunoistochemical analysis (A) of the islets was carried out on paraffin sections using insulin (left panel) or glucagon (right panel) antibodies. Microphotographs are representative of images obtained from pancreas sections of five 6-month-old β2AR+/+ (upper panel) or β2AR −/− (lower panel) mice. Insulin (B) and glucagon (C) content in isolated islets from β2AR+/+ (n = 10) or β2AR −/− (n = 13) mice. Insulin secretion in response to basal (2.8 mmol/L) or high (16.7 mmol/L) glucose concentration and to KCl (33 mmol/L) was measured in isolated islets from β2AR+/+ (□) and β2AR−/− (■) mice (D). Bars represent means ± SE of data from 10 mice per group. *P < 0.05 vs. β2AR+/+, Bonferroni post hoc test. (See also Supplementary Fig. 1.) (A high-quality digital representation of this figure is available in the online issue.)

We then posed the further question of whether the reduced glucose insulin secretion observed in the β2AR−/− mice in vivo may represent the direct consequence of the β2AR−/− lack in the β-cells or whether it is indirectly mediated by other regulatory factors. To answer this question, we analyzed glucose effect on islets isolated from the null mice. As shown in Fig. 2D, these islets responded poorly to increased glucose concentration in the culture medium compared with the islets from their wild-type littermates but were fully responsive to KCl depolarization.

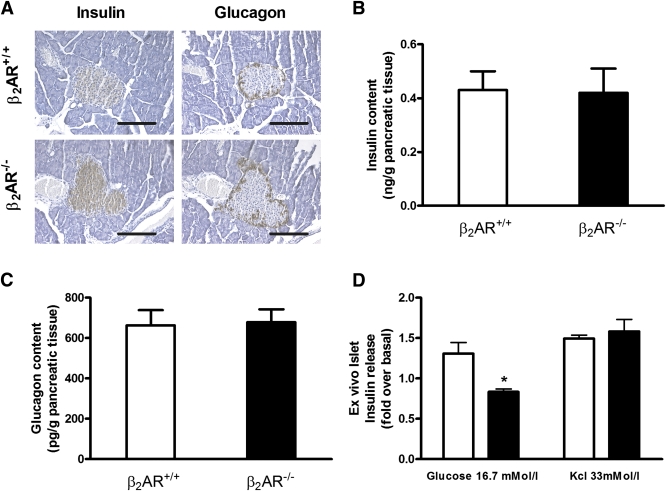

Islets and β-cell profiling after β2AR deletion.

To gain further insight into the mechanism leading to impaired insulin secretion in mice lacking β2AR, we profiled the expression of different genes relevant to β-cell regulation by real-time RT-PCR of islet mRNA. As shown in Fig. 3A and B, mRNA levels of both PDX-1 and GLUT2, two major genes involved in β-cell function, were decreased in islets from β2AR−/− mice by 75 and 60%, respectively. Also, mRNA levels of the PDX-1/GLUT2 upstream regulator PPARγ were decreased by 54% compared with islets from wild-type mice (Fig. 3C). Reliable results were obtained in immunoblotting experiments (Fig. 3D and E). PDX-1 and GLUT2 mRNAs were also reduced to a similar extent in total pancreatic tissue from the β2AR−/− mice (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Gene expression profile in isolated Langerhans islets from β2AR+/+ and β2AR−/− mice. The abundance of mRNAs for PDX-1 (A), GLUT2 (B), and PPARγ (C) was determined by real-time RT-PCR analysis of total RNA, using cyclophilin as internal standard. The mRNA levels in β2AR−/− mice are relative to those in control animals. Each bar represents means ± SE of four independent experiments in each of which reactions were performed in triplicate using the pooled total RNAs from five mice/genotype. Proteins from a Western blot representative of three independent experiments were quantified by densitometry (D and E). *P < 0.05 vs. β2AR+/+, Bonferroni post hoc test. AU, arbitrary units.

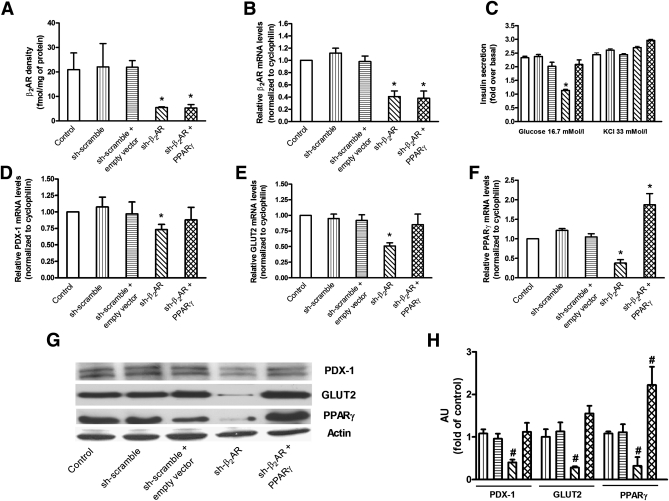

We then sought to demonstrate whether these abnormalities in gene expression were directly caused by β2AR silencing. To pursue this objective, we silenced with a specific shRNA (Supplementary Fig. 2) the β2AR gene in the glucose-responsive INS-1E β-cell line (INS-1Eshβ2AR) (Fig. 4A and B). As shown in Fig. 4C, this specific knockdown impaired glucose-induced insulin secretion by 58% in these cells. A similarly sized effect was achieved by treatment with the specific β2AR antagonist ICI, while the β2AR agonist fenoterol showed an opposite action (Supplementary Fig. 3A). Consistent with our ex vivo results, the INS-1Eshβ2AR displayed a reduction in PDX-1, GLUT2, and PPARγ mRNA (Fig. 4D–F) and protein levels (Fig. 4G and H). Interestingly, transient transfection of a PPARγ cDNA in INS-1Eshβ2AR β-cells increased glucose-induced insulin secretion compared with the wild-type INS1-E control β-cells (Fig. 4C). In addition, overexpression of PPARγ prevented the downregulation of both PDX-1 and GLUT2 occurring in the INS-1Eshβ2AR β-cells (Fig. 4D–H). Consistently, treatment of INS-1E β-cells with ICI decreased PDX-1 and GLUT2 mRNA and protein levels, while PPARγ overexpression completely prevented the effect of ICI (Supplementary Fig. 3B–D), suggesting that β2AR controls insulin secretion through a PPARγ/PDX-1–mediated mechanism.

FIG. 4.

β2AR levels, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, and gene expression profile in silenced INS-1E β-cells. Treatment with a specific β2AR-shRNA significantly decreased the density (by 73.7% [A]) and mRNA levels (by 59.1% [B]) of β2AR in INS-1E β-cells. β2AR-shRNA inhibited the insulin secretory response to 16.7 mmol/L glucose, which was rescued by the overexpression of PPARγ (C). KCl-induced insulin release (C) was not significantly different among the studied groups. β2AR-shRNA also determined a significant reduction in mRNA level of PDX-1 (D), GLUT2 (E), and PPARγ (F) that was prevented by the overexpression of PPARγ. Bars represent means ± SE from four to five independent experiments in each of which reactions were performed in triplicate ( , control, i.e. untreated INS-1E β-cells;

, control, i.e. untreated INS-1E β-cells;  , sh-scramble;

, sh-scramble;  , sh-scramble+empty vector;

, sh-scramble+empty vector;  , sh-β2AR;

, sh-β2AR;  , sh-β2AR+PPARγ; *P < 0.05 vs. control, Bonferroni post hoc test; basal is glucose 2.8 mmol/L. Equal amount of proteins from three independent experiments was analyzed by Western blotting and quantified by densitometry (G and H ). *P < 0.05 vs. sh-scramble. AU, arbitrary units. (See also Supplementary Figs. 2–4.)

, sh-β2AR+PPARγ; *P < 0.05 vs. control, Bonferroni post hoc test; basal is glucose 2.8 mmol/L. Equal amount of proteins from three independent experiments was analyzed by Western blotting and quantified by densitometry (G and H ). *P < 0.05 vs. sh-scramble. AU, arbitrary units. (See also Supplementary Figs. 2–4.)

To better define the β2AR downstream mechanism leading to PPARγ activation, we assessed the cAMP levels in these cells, observing an impaired production of cAMP in INS-1Eshβ2AR β-cells both in basal condition and after stimulation with the βAR agonist isoproterenol (Supplementary Fig. 4A). Accordingly, to rule out possible involvement of other components of β2AR signaling machinery, we assessed the protein level of AC-VI, GRK2, and Gαs, and we found no significant difference (Supplementary Fig. 4B and C). Parallel results were obtained in ex vivo experiments, performed to investigate the possible age-related alterations in the β2AR transduction pathway, comparing pancreatic islets isolated from adult (6 months old) and old (20 months old) β2AR+/+ mice (Supplementary Fig. 4D and E).

β2AR overexpression rescued the age-related impairment in insulin release.

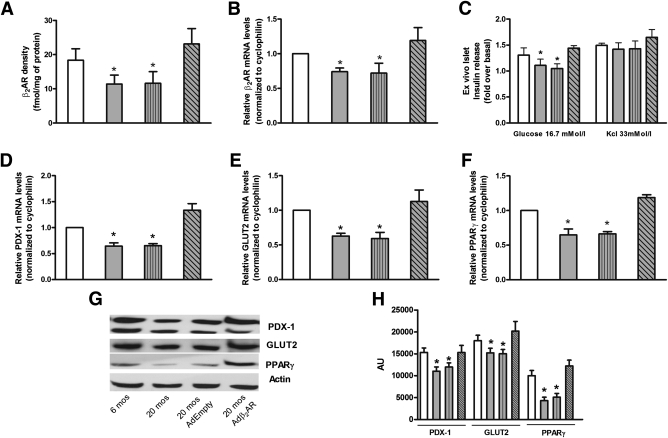

Based on radioligand binding and real-time RT-PCR analysis, the expression of both β2AR protein and mRNA was significantly decreased in islets from aged (20 months old) β2AR+/+ mice compared with those isolated from adult (6 months old) mice (Fig. 5A and B). PDX-1, GLUT2, and PPARγ expression (both in terms of mRNA and protein level) was also reduced, and insulin release in response to glucose, though not that evoked by KCl depolarization, was impaired in islets from the aged mice (Fig. 5C–H), suggesting that the reduced β2AR density constrains islet glucose response in these animals. To prove this hypothesis, we used an adenoviral construct driving overexpression of human β2AR in mouse islets. Interestingly, infection of islets isolated from wild-type old mice with this construct induced a twofold increase in β2AR expression (Fig. 5A and B) and returned glucose-induced insulin secretion to levels comparable with those of islets from 6-month-old mice (Fig. 5C) accompanied by restored expression of PDX-1, GLUT2, and PPARγ (Fig. 5D–H).

FIG. 5.

β2AR ex vivo infection rescued age-dependent impairment of β-cell function. Density (A) and mRNA levels (B) of β2AR were evaluated on cell membranes of islets isolated from β2AR+/+ mice. Insulin release (C) was determined upon exposure to the indicated concentration of glucose or KCl as described in research design and methods. mRNA levels of PDX-1 (D), GLUT2 (E), and PPARγ (F) were determined by real-time RT-PCR using the pooled total RNAs from five mice/group with cyclophilin as internal standard. Each bar represents means ± SE of five independent experiments in each of which reactions were performed in triplicate. Islets isolated from β2AR+/+ mice were solubilized and aliquots of the lysates were blotted with PDX-1, GLUT2, and PPARγ antibodies. Actin was used as loading control. The autoradiographs shown (G) are representative of three independent experiments, which are quantified in H.  , age 6 months (mos);

, age 6 months (mos);  , 20 months;

, 20 months;  , 20 months AdEmpty;

, 20 months AdEmpty;  , 20 months Adβ2AR. *P < 0.05 vs. β2AR+/+ 6 months, Bonferroni post hoc test.

, 20 months Adβ2AR. *P < 0.05 vs. β2AR+/+ 6 months, Bonferroni post hoc test.

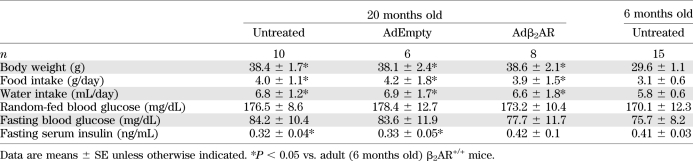

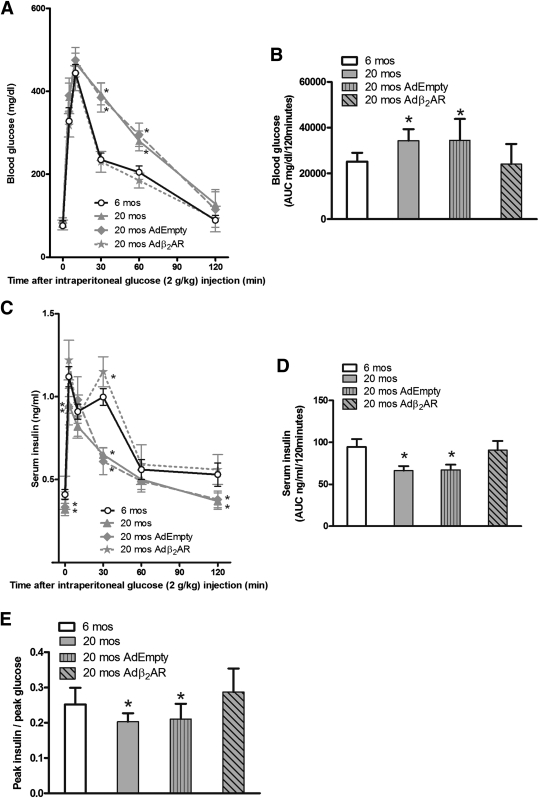

In the in vivo setup, 20-month-old β2AR+/+ mice exhibited a significant reduction in fasting serum insulin levels (Table 2) accompanied by impaired glucose tolerance and insulin response upon GTT (Fig. 6A–E). We have therefore designed a gene therapy protocol aimed to prove that these abnormalities can be corrected by restoring β2AR density. Accordingly, we infected the pancreas of aged mice by Adβ2AR injection. This injection effectively rescued β2AR expression in the pancreatic tissue, returning it to levels comparable with those of 6-month-old mice (Supplementary Fig. 5A and B), and restored the expression of PDX-1, GLUT2, and PPARγ (Supplementary Fig. 5C–E). Injections in the distal pancreas did not induce β2AR expression in other tissues, such as the liver (Supplementary Fig. 6A and B) or the skeletal muscle (Supplementary Fig. 6C and D).

TABLE 2.

Metabolic effects of β2AR overexpression in aged (20 months old) β2AR+/+ mice

FIG. 6.

Adenoviral vector-mediated β2AR gene transfer in the mouse pancreas rescued age-related reduction in glucose tolerance. Blood glucose levels (A) and serum insulin (C) after 120 min of glucose administration (n = 14–18 animals per group). We calculated the AUC from glucose (B) and insulin excursion (D) curves. Twenty-month-old β2AR+/+ mice showed glucose intolerance (A and B), impaired insulin secretion (C and D), and also an impairment in β-cell function, evaluated measuring the peak insulin–to–peak glucose ratio (E). All of these parameters were restored after Adβ2AR in vivo infection. *P < 0.05 vs. β2AR+/+ at 6 months (mos) of age, Bonferroni post hoc test. (See also Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6.)

These effects were paralleled by significant improvement in glucose tolerance and insulin secretion during GTT (Fig. 6A–E). Fasting insulin levels also increased, reaching values similar to those measured in 6-month-old mice (Table 2), further underlining the relevance of β2AR function in enabling adequate pancreatic β-cell response to hyperglycemia.

DISCUSSION

In the present work, we provide evidence that β2AR gene deletion in mice causes reduction of glucose-stimulated insulin release by pancreatic β-cells. This phenotype is reminiscent of that observed in mice with targeted β-cell disruption of the Gas gene (30). In these mice, however, the impairment of Gαs prevented response to multiple Gαs-related receptors, causing a severe phenotype, with gross abnormalities in pancreatic islets. Interestingly, in islets from β2AR−/− mice, PPARγ expression was reduced by 50%, leading to repression of the PPARγ downstream molecules PDX-1 and GLUT2, two key effectors of β-cell function (26,42,43). This downregulation resulted in a clear impairment in insulin release, though islet architecture and insulin content were not affected by the β2AR gene deletion.

Rosen et al. (44) showed that islets from mice with targeted elimination of PPARγ in β-cells were approximately twice as large as those from control mice. Thus, we can speculate that in our model the 50% reduction in PPARγ levels is sufficient to restrain β-cell function without altering islet mass.

The mechanistic significance of β2AR gene knockout was further sustained by in vitro studies in the INS-1E pancreatic β-cells, showing that the silencing of the β2AR as well as the pharmacological treatment with a specific β2AR antagonist impaired glucose response and downregulated PPARγ expression, reducing both PDX-1 and GLUT2 levels. No alteration of αARs was observed instead (data not shown). In addition, treatment with the β2AR agonist fenoterol activated PPARγ/PDX-1/GLUT2 signaling, indicating that, at least in part, β2AR controls insulin secretion through this pathway. Indeed, in this study we show that exogenous PPARγ expression in INS-1E β-cells silenced for β2AR led to recovery of PDX-1/GLUT2 levels and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. This finding is supported by recent evidence that directly relates β2AR to PPARγ (42,45–47), a key element in the process of insulin secretion that has also recently been investigated in aging (43,48). Our results are consistent with these observations, sustaining also the hypothesis that cAMP levels could act as a connecting link through which β2AR signaling leads to activation of PPARγ (49,50). Moreover, the cAMP assays, performed both in INS-1Eshβ2AR pancreatic β-cells and in islets isolated from aged mice, showed an impairment in basal conditions and after stimulation with isoproterenol, while the responses to NaF and forskolin were not affected. Also, Gαs and AC-VI protein levels were not significantly different among the explored settings. This combination of events is usually observed in models of β2AR gene deletion or impaired β2AR signaling (18,34).

Whether and to what extent β2AR gene knockout in liver and peripheral tissues affects glucose homeostasis in the β2AR−/− mice remain to be conclusively addressed. Indeed, variations at the β2AR locus have also been reported to associate with insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic patients (16). However, as shown in this work, the impaired glucose tolerance of β2AR−/− mice is likely contributed by the defective β-cell function, as indicated by the major effect of β2AR lack on glucose-evoked insulin secretion.

In humans, glucose tolerance declines with age, resulting in a high prevalence of type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in the elderly population (2,8). How, at the individual level, glucose tolerance declines remains unclear, but it is likely determined by multiple factors including diminished insulin secretion (3,7). In rat models and in humans, a progressive decline in β-cell activity with age has been documented (4,6). In the present work, we show that the same occurs in the C57Bl/6N mouse and is paralleled by the development of abnormal glucose tolerance. Similar to previous findings in several human tissues (18–21,24), our results show that these changes are accompanied by reduced β2AR levels in mouse pancreatic islets. The decreased β2AR density in islets from aged mice recapitulates the mechanisms leading to the insulin secretory defect occurring in β2AR-null mice, indicating that it may contribute to the age-related impairment in glucose tolerance. Indeed, both in vivo and ex vivo experiments of β2AR gene transfer revealed that recovery of normal β2AR levels rescued insulin release and glucose tolerance in aged mice. Thus, in the mouse model progressive decline of islet β2AR density appears to contribute to the reduction in glucose tolerance that accompanies aging. Whether the same also occurs in humans needs to be clarified and is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

In conclusion, we have shown that β2AR physiologically regulates pancreatic β-cell insulin secretion by modulating PPARγ/PDX-1/GLUT2 function. Reduced β2AR expression contributes to the age-dependent deterioration of glucose tolerance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The financial support of Telethon and Fondazione Veronesi is gratefully acknowledged.

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

G.S. conceived the project, performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. A.L. performed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. D.S. performed experiments and contributed to discussion. A.A. performed experiments. C.D.G. performed experiments. P.F. analyzed data and contributed to discussion. F.B. analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. B.T. designed research and supervised the project. C.M. analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. G.I. designed research, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. G.S. and G.I. are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The authors thank Brian Kobilka (Stanford University, Stanford, CA) for providing the founders of β2AR−/− mice, Pierre Maechler (University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland) for supplying INS-1E pancreatic β-cells, and Walter J. Koch (Center for Translational Medicine, and Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA) for providing the Adβ2AR. The valuable technical assistance of Alfonso Anastasio (“San Giovanni di Dio” Hospital, Frattaminore, Italy) is also acknowledged.

Footnotes

This article contains Supplementary Data online at http://diabetes.diabetesjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2337/db11-1027/-/DC1.

REFERENCES

- 1.Defronzo RA. Banting Lecture. From the triumvirate to the ominous octet: a new paradigm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 2009;58:773–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basu R, Breda E, Oberg AL, et al. Mechanisms of the age-associated deterioration in glucose tolerance: contribution of alterations in insulin secretion, action, and clearance. Diabetes 2003;52:1738–1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gumbiner B, Polonsky KS, Beltz WF, Wallace P, Brechtel G, Fink RI. Effects of aging on insulin secretion. Diabetes 1989;38:1549–1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma X, Becker D, Arena VC, Vicini P, Greenbaum C. The effect of age on insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion in first-degree relatives of type 1 diabetic patients: a population analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009;94:2446–2451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reaven E, Wright D, Mondon CE, Solomon R, Ho H, Reaven GM. Effect of age and diet on insulin secretion and insulin action in the rat. Diabetes 1983;32:175–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perfetti R, Rafizadeh CM, Liotta AS, Egan JM. Age-dependent reduction in insulin secretion and insulin mRNA in isolated islets from rats. Am J Physiol 1995;269:E983–E990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ihm SH, Matsumoto I, Sawada T, et al. Effect of donor age on function of isolated human islets. Diabetes 2006;55:1361–1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iozzo P, Beck-Nielsen H, Laakso M, Smith U, Yki-Järvinen H, Ferrannini E, European Group for the Study of Insulin Resistance Independent influence of age on basal insulin secretion in nondiabetic humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1999;84:863–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosengren AH, Jokubka R, Tojjar D, et al. Overexpression of alpha2A-adrenergic receptors contributes to type 2 diabetes. Science 2010;327:217–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doyle ME, Egan JM. Pharmacological agents that directly modulate insulin secretion. Pharmacol Rev 2003;55:105–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lembo G, Napoli R, Capaldo B, et al. Abnormal sympathetic overactivity evoked by insulin in the skeletal muscle of patients with essential hypertension. J Clin Invest 1992;90:24–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seals DR, Esler MD. Human ageing and the sympathoadrenal system. J Physiol 2000;528:407–417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lembo G, Capaldo B, Rendina V, et al. Acute noradrenergic activation induces insulin resistance in human skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol 1994;266:E242–E247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Asensio C, Jimenez M, Kühne F, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F, Muzzin P. The lack of beta-adrenoceptors results in enhanced insulin sensitivity in mice exhibiting increased adiposity and glucose intolerance. Diabetes 2005;54:3490–3495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haffner CA, Kendall MJ. Metabolic effects of beta 2-agonists. J Clin Pharm Ther 1992;17:155–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikarashi T, Hanyu O, Maruyama S, et al. Genotype Gly/Gly of the Arg16Gly polymorphism of the beta2-adrenergic receptor is associated with elevated fasting serum insulin concentrations, but not with acute insulin response to glucose, in type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2004;63:11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scarpace PJ, Mooradian AD, Morley JE. Age-associated decrease in beta-adrenergic receptors and adenylate cyclase activity in rat brown adipose tissue. J Gerontol 1988;43:B65–B70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xiao RP, Tomhave ED, Wang DJ, et al. Age-associated reductions in cardiac beta1- and beta2-adrenergic responses without changes in inhibitory G proteins or receptor kinases. J Clin Invest 1998;101:1273–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schocken DD, Roth GS. Reduced beta-adrenergic receptor concentrations in ageing man. Nature 1977;267:856–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feldman RD, Limbird LE, Nadeau J, Robertson D, Wood AJ. Alterations in leukocyte beta-receptor affinity with aging. A potential explanation for altered beta-adrenergic sensitivity in the elderly. N Engl J Med 1984;310:815–819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bao X, Mills PJ, Rana BK, et al. Interactive effects of common beta2-adrenoceptor haplotypes and age on susceptibility to hypertension and receptor function. Hypertension 2005;46:301–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kang KB, Rajanayagam MA, van der Zypp A, Majewski H. A role for cyclooxygenase in aging-related changes of beta-adrenoceptor-mediated relaxation in rat aortas. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2007;375:273–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ryall JG, Plant DR, Gregorevic P, Sillence MN, Lynch GS. Beta 2-agonist administration reverses muscle wasting and improves muscle function in aged rats. J Physiol 2004;555:175–188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White M, Roden R, Minobe W, et al. Age-related changes in beta-adrenergic neuroeffector systems in the human heart. Circulation 1994;90:1225–1238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chruscinski AJ, Rohrer DK, Schauble E, Desai KH, Bernstein D, Kobilka BK. Targeted disruption of the beta2 adrenergic receptor gene. J Biol Chem 1999;274:16694–16700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evans-Molina C, Robbins RD, Kono T, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma activation restores islet function in diabetic mice through reduction of endoplasmic reticulum stress and maintenance of euchromatin structure. Mol Cell Biol 2009;29:2053–2067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vigliotta G, Miele C, Santopietro S, et al. Overexpression of the ped/pea-15 gene causes diabetes by impairing glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in addition to insulin action. Mol Cell Biol 2004;24:5005–5015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santulli G, Basilicata MF, De Simone M, et al. Evaluation of the anti-angiogenic properties of the new selective αVβ3 integrin antagonist RGDechiHCit. J Transl Med 2011;9:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sorriento D, Santulli G, Fusco A, Anastasio A, Trimarco B, Iaccarino G. Intracardiac injection of AdGRK5-NT reduces left ventricular hypertrophy by inhibiting NF-kappaB-dependent hypertrophic gene expression. Hypertension 2010;56:696–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xie T, Chen M, Zhang QH, Ma Z, Weinstein LS. Beta cell-specific deficiency of the stimulatory G protein alpha-subunit Gsalpha leads to reduced beta cell mass and insulin-deficient diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104:19601–19606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lombardi A, Ulianich L, Treglia AS, et al. Increased hexosamine biosynthetic pathway flux dedifferentiates INS-1E cells and murine islets by an extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2-mediated signal transmission pathway. Diabetologia 2012;55:141–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fiory F, Lombardi A, Miele C, Giudicelli J, Béguinot F, Van Obberghen E. Methylglyoxal impairs insulin signalling and insulin action on glucose-induced insulin secretion in the pancreatic beta cell line INS-1E. Diabetologia 2011;54:2941–2952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGraw DW, Forbes SL, Mak JC, et al. Transgenic overexpression of beta(2)-adrenergic receptors in airway epithelial cells decreases bronchoconstriction. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2000;279:L379–L389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mutlu GM, Dumasius V, Burhop J, et al. Upregulation of alveolar epithelial active Na+ transport is dependent on beta2-adrenergic receptor signaling. Circ Res 2004;94:1091–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ciccarelli M, Sorriento D, Cipolletta E, et al. Impaired neoangiogenesis in β₂-adrenoceptor gene-deficient mice: restoration by intravascular human β₂-adrenoceptor gene transfer and role of NFκB and CREB transcription factors. Br J Pharmacol 2011;162:712–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iaccarino G, Ciccarelli M, Sorriento D, et al. Ischemic neoangiogenesis enhanced by beta2-adrenergic receptor overexpression: a novel role for the endothelial adrenergic system. Circ Res 2005;97:1182–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sorriento D, Ciccarelli M, Santulli G, et al. The G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 5 inhibits NFkappaB transcriptional activity by inducing nuclear accumulation of IkappaB alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008;105:17818–17823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perino A, Ghigo A, Ferrero E, et al. Integrating cardiac PIP3 and cAMP signaling through a PKA anchoring function of p110γ. Mol Cell 2011;42:84–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ciccarelli M, Santulli G, Campanile A, et al. Endothelial alpha1-adrenoceptors regulate neo-angiogenesis. Br J Pharmacol 2008;153:936–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Oriente F, Iovino S, Cassese A, et al. Overproduction of phosphoprotein enriched in diabetes (PED) induces mesangial expansion and upregulates protein kinase C-beta activity and TGF-beta1 expression. Diabetologia 2009;52:2642–2652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mauvais-Jarvis F, Virkamaki A, Michael MD, et al. A model to explore the interaction between muscle insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction in the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 2000;49:2126–2134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faisy C, Pinto FM, Blouquit-Laye S, et al. beta2-Agonist modulates epithelial gene expression involved in the T- and B-cell chemotaxis and induces airway sensitization in human isolated bronchi. Pharmacol Res 2010;61:121–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blalock EM, Phelps JT, Pancani T, et al. Effects of long-term pioglitazone treatment on peripheral and central markers of aging. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e10405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosen ED, Kulkarni RN, Sarraf P, et al. Targeted elimination of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in beta cells leads to abnormalities in islet mass without compromising glucose homeostasis. Mol Cell Biol 2003;23:7222–7229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Collins S, Yehuda-Shnaidman E, Wang H. Positive and negative control of Ucp1 gene transcription and the role of β-adrenergic signaling networks. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010;34(Suppl. 1):S28–S33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fogli S, Pellegrini S, Adinolfi B, et al. Rosiglitazone reverses salbutamol-induced β(2) -adrenoceptor tolerance in airway smooth muscle. Br J Pharmacol 2011;162:378–391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tadaishi M, Miura S, Kai Y, et al. Effect of exercise intensity and AICAR on isoform-specific expressions of murine skeletal muscle PGC-1α mRNA: a role of β₂-adrenergic receptor activation. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2011;300:E341–E349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sung B, Park S, Yu BP, Chung HY. Modulation of PPAR in aging, inflammation, and calorie restriction. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2004;59:997–1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guri AJ, Hontecillas R, Bassaganya-Riera J. Abscisic acid synergizes with rosiglitazone to improve glucose tolerance and down-modulate macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue: possible action of the cAMP/PKA/PPAR γ axis. Clin Nutr 2010;29:646–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim SP, Ha JM, Yun SJ, et al. Transcriptional activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma requires activation of both protein kinase A and Akt during adipocyte differentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010;399:55–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]