Abstract

Background and Aims

ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase) is a key enzyme of starch biosynthesis. In the green plant lineage, it is composed of two large (LSU) and two small (SSU) sub-units encoded by paralogous genes, as a consequence of several rounds of duplication. First, our aim was to detect specific patterns of molecular evolution following duplication events and the divergence between monocotyledons and dicotyledons. Secondly, we investigated coevolution between amino acids both within and between sub-units.

Methods

A phylogeny of each AGPase sub-unit was built using all gymnosperm and angiosperm sequences available in databases. Accelerated evolution along specific branches was tested using the ratio of the non-synonymous to the synonymous substitution rate. Coevolution between amino acids was investigated taking into account compensatory changes between co-substitutions.

Key Results

We showed that SSU paralogues evolved under high functional constraints during angiosperm radiation, with a significant level of coevolution between amino acids that participate in SSU major functions. In contrast, in the LSU paralogues, we identified residues under positive selection (1) following the first LSU duplication that gave rise to two paralogues mainly expressed in angiosperm source and sink tissues, respectively; and (2) following the emergence of grass-specific paralogues expressed in the endosperm. Finally, we found coevolution between residues that belong to the interaction domains of both sub-units.

Conclusions

Our results support the view that coevolution among amino acid residues, especially those lying in the interaction domain of each sub-unit, played an important role in AGPase evolution. First, within SSU, coevolution allowed compensating mutations in a highly constrained context. Secondly, the LSU paralogues probably acquired tissue-specific expression and regulatory properties via the coevolution between sub-unit interacting domains. Finally, the pattern we observed during LSU evolution is consistent with repeated sub-functionalization under ‘Escape from Adaptive Conflict’, a model rarely illustrated in the literature.

Keywords: Angiosperms, monocotyledons, dicotyledons, paralogue genes, molecular evolution, coevolution, neofunctionalization, subfunctionalization, starch synthesis, AGPase

INTRODUCTION

Gene duplication has been recognized as a major source for organism evolution. Indeed, the emergence of multiple copies of a gene offers raw material for the selection of new structural or regulatory functions allowing genetic innovation (reviewed by Flagel and Wendel, 2009). Because most duplicated genes are initially redundant in function, the most common fate of gene duplicates is the loss of function of one paralogue through its silencing by the accumulation of deleterious mutations ultimately leading to its non-functionalization (Walsh, 1995; Otto, 2007). In order to explain the maintenance of paralogues and the pervasiveness of gene families, several models have been proposed that assume either sub-functionalization or neofunctionalization (reviewed by Conant and Wolfe, 2008). Sub-functionalization occurs when two paralogues are necessary to maintain the initial function. Under the Duplication/Degeneration/Complementation (DDC) model (Force et al., 1999), differential accumulation of deleterious mutations in both duplicates results in the partition of the initial function (Hahn, 2009). Alternatively, under the Escape from Adaptive Conflict (EAC) model (Hughes, 1994; Des Marais and Rausher, 2008), a novel function arises in the initial copy before the duplication, thereby generating an adaptive conflict between two sub-functions that can not be optimized simultaneously. Duplication resolves this conflict by allowing adaptive changes in both duplicates to optimize the ancestral and the novel function. Finally, the neofunctionalization model (Ohno, 1970; Force et al., 1999) posits that one paralogue evolves a new function through the accumulation of beneficial mutations, while the other copy maintains the ancestral function through purifying selection. Note that the evolution of gene function under sub- or neofunctionalization may concern either the coding sequence or the regulatory region, or both (Duarte et al., 2006).

Distinguishing among these models, and thus determining the mechanisms responsible for the maintenance of duplicates, is a very difficult task (Hahn, 2009). Evidence for acceleration in the rate of non-synonymous substitutions following duplications has been reported in a few studies (Kondrashov et al., 2002; Nembaware et al., 2002) suggesting either a relaxation of selective constraints or the action of positive selection. Positive selection accompanying neofunctionalization has been reported at the Mam1 genes involved in plant defence against herbivory in Arabidopsis thaliana (Benderoth et al., 2006), and in duplicates encoding transcriptional repressors in Drosophila (Beisswanger and Stephan, 2008). Des Marais and Rausher (2008) have presented one of the first examples of the application of the EAC model in the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway of Convolvulaceae. Finally, Aguileta et al. (2006) have demonstrated that both differential patterns of purifying selection and positive selection acting on coding regions have contributed to the evolution of the β-globin gene family in various vertebrate species.

While it is clear that the molecular evolution of the regulatory or coding region of a gene can have a strong impact on its function, less attention has been devoted to investigating coevolution, perhaps because this task is even more challenging. At the molecular level, coevolution may be viewed as the reciprocal evolutionary change in interacting genes or residues within a gene (Atchley et al., 2000; Lovell and Robertson, 2010). Because of the complex and functionally critical three-dimensional structure of proteins and protein complexes, the evolution at one site or gene is often constrained by the evolution at interacting residues. Within a protein, coevolution is thus expected to target residues that are proximate or involved in the same structural domain. Such cases have been observed (Altschuh et al., 1987; Atchley et al., 2000; Gloor et al., 2005; Halabi et al., 2009), although coevolution can also concern more distant residues (Clarke, 1995; Gloor et al., 2005; Fares and McNally, 2006). Finally, coevolution has been evidenced in residues encoded by different genes either involved in between protein interaction domains or co-recruited to achieve a function (Travers and Fares, 2007; Chao et al., 2008; Madaoui and Guerois, 2008).

Correlation of phylogenetic distance between trees of interacting genes has often been used as a measure of coevolution (Pazos et al., 1997; Goh et al., 2000; Goh and Cohen, 2002; Rodionov et al., 2011). Although this method has proved powerful to pinpoint coevolving sites or genes, it remains difficult to discriminate between the confounded effects of the common phylogenetic history and true functional coevolution (Maddison, 1997; Lovell and Robertson, 2010). Additional evidence for coevolution can be found from the compensating nature of co-substitutions that allows the maintenance of a common function. Although the phenotypic effects of substitutions are generally unknown, compensation in terms of amino acid physico-chemical properties – such as volume, charge or polarity – is expected to help in maintaining the global protein structure and/or activity. Dutheil and Galtier (2007) proposed a method that (1) corrects for phylogenetic history by looking for co-substitution along tree branches; and (2) takes the compensating effects of co-substitutions into account. Their method may be of particular interest to detect functional coevolution in situations where fitness cannot be assessed but the three-dimensional protein structure and protein functional domains are known.

Genes encoding ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase) in angiosperms form a multigenic family that offers a relevant model to study the evolution of paralogues. AGPase catalyses a rate-limiting reaction in the synthesis of storage polysaccharides, namely glycogen in prokaryotes and starch in plants. This enzyme is composed of four sub-units either identical, leading to a homotetramer α4 as observed in prokaryotes, or different, forming a heterotetramer α2β2 as observed in unicellular green algae, the moss Physcomitrella patens and angiosperms (Ballicora et al., 2003). The heterotetramer is composed of two small sub-units (SSUs) and two large sub-units (LSUs). Because of the monophyletic origin of Archaeplastida from a single endosymbiosis, and the absence of AGPase in Rhodophyta, the small and large sub-units are thought to derive from a gene duplication occurring after the separation of Chloroplastida from Rhodophyceae (Preiss et al., 1991; Deschamps et al., 2008). While Ballicora et al. (1995, 1998) first argued for a catalytic and a regulatory specialization of the SSU and the LSU, respectively, suggesting sub-functionalization, subsequent studies have provided evidence of a fuzzy functional distinction between sub-units (Cross et al., 2004; Georgelis et al., 2007; Ventriglia et al., 2008). Following the initial duplication that led to the emergence of the heterotetramer protein, additional duplications occurred in angiosperms (Hannah et al., 2001). Some of them led to paralogue specialization in the tissue where they were expressed, e.g. expression in sink or source tissues following the first duplication of the LSU (Hannah et al., 2001; Georgelis et al., 2007), or at the sub-cellular level, e.g. gene expression restricted to the plastid in plants except in grass endosperm where it is mainly cytosolic (Denyer et al., 1996; Beckles et al., 2001; Comparot-Moss and Denyer, 2009). The specificity of paralogue expression was probably accompanied by an enhanced variability in AGPase allosteric response between species as well as within species among duplicates expressed in photosynthetic and non-photosynthetic tissues (Sikka et al., 2001; Hendriks et al., 2003; Tetlow et al., 2003). Physiological studies of AGPase based on mutagenesis experiments led to the identification of specific functions for protein residues and/or domains as well as the characterization of activators and inhibitors that participate in the regulation of enzymatic activity (Hill et al., 1991; Greene et al., 1996; Frueauf et al., 2003; Yep et al., 2006). In addition, interactions between sub-units are critical for AGPase allosteric regulation (Kim et al., 2007; Baris et al., 2009; Georgelis et al., 2009).

Given the essential function of polysaccharide storage in the development and survival of organisms, AGPase probably evolved under strong purifying selective pressures. On the other hand, because some duplications have been accompanied by a change of cellular compartment (e.g. from plastidial to cytosolic) or a partitioning of expression and a subsequent modification of regulation properties, contrasting evolutionary patterns are expected among paralogues. Consistent with this expectation, Georgelis et al. (2008) have reported an overall accelerated rate of evolution following recent duplications and identified a number of sites under positive selection in each sub-unit. In addition, the temporal succession of duplications differs among sub-units, leading to an unbalanced number of SSU and LSU partners, one SSU often interacting with multiple LSUs (Georgelis et al., 2008, 2009). As a consequence, SSUs evolved at a lower rate than LSUs and were subjected to a higher level of selective constraint reflecting the interaction of one SSU with multiple LSUs to form functional enzyme complexes expressed in different organs (Georgelis et al., 2007). Finally, the unique cytosolic localization and very high efficiency in grass endosperm of AGPase suggest that AGPase genes expressed in this organ may have undergone particularly strong selective pressure.

In the present study, we took advantage of the increasing number of LSU and SSU sequences available in databases to assemble a data set that contains about twice as many sequences as previous studies (170 sequences from 54 spermatophyta, mainly angiosperm, species), including relevant taxonomic groups that were absent from previous studies such as gymnosperms or non-grasses monocots. We therefore provide new insights into the processes at work in the evolution of the AGPase multigenic family. Because we expect a prominent role of sub-unit interaction, we employed an innovative approach to assess whether both the selective constraints undergone by paralogues and the complex heterotetrameric structure of AGPase have entailed potential coevolution between amino acid residues during the course of angiosperm evolution. In order to achieve these goals, we (1) searched for evidence of differential selective constraints or accelerated evolution at branches and/or residues following gene duplication events or divergence between monocots and dicots; (2) mapped the positions of the sites that we found to evolve under positive selective pressure to known physiological domains involved either in the enzyme allosteric regulation or in the interaction between both sub-units; and (3) tested for evidence of coevolution within and between sub-units by tracking correlated substitution patterns (co-substitutions) among residues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sequence retrieval and alignment

We retrieved full-length DNA coding sequences of the small (SSU) and large (LSU) AGPase sub-units of angiosperms by BLAST searches against the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/blast/Blast.cgi) or Phytozome using either protein (TBLASTN program) or nucleotide (BLASTN program) AGPase coding sequences from Zea mays and A. thaliana as queries. Oryza sativa sequences were retrieved from The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) database version 5 (http://www.tigr.org/tdb/e2k1/osa1/). Populus trichocarpa sequences were retrieved from the Joint Genome Institute v1·0 (http://genome.jgi-psf.org). We retrieved 59 and 105 angiosperm, and three and three gymnosperm DNA coding sequences of the AGPase SSU and LSU, respectively. Sequences of the outgroups Ostreococcus lucimarinus, O. tauri (Chlorophyta, green algae) and P. patens (Bryophyta, moss) – one SSU and one LSU paralogue for each species – were retrieved from the Joint Genome Institute database, and one sequence of Anabaena (Cyanobacteria) – GenBank accession no. Z11539 – was retrieved from NCBI using the A. thaliana sequence At5g19220 in a tblastn request. For each sub-unit, protein sequences were aligned using Clustal W implemented in BIOEDIT (Thompson et al., 1994) and the alignment was further edited manually. Note that the Z. mays LSU paralogue sequence expressed in the embryo (NCBI accession no. Z38111, W22 lineage) presented several gaps at the C-terminal region leading to high divergence in the translated sequence. We therefore re-sequenced the 3′ part of the coding region in the W22 maize inbred line, using genomic DNA obtained from a pool of five plants and the following primers: forward primer CATTCTTCACTTCCCCTGC and reverse primer CTTGCAGGCCATGCGTAAG (SIGMA©-Genosys). This new sequence (GenBank accession no. FJ439131) was far less divergent than the NCBI sequence, suggesting the erroneous nature of the latter. We subsequently used FJ439131 as the LSU maize embryo reference sequence in our analyses. In a region of 270 and 255 nucleotides located at the 5′ end of the SSU and LSU, respectively, most sequences greatly diverged from each other and a large number of gaps was required for alignment. This region was thus removed since poor quality alignment may both decrease the quality of the phylogenetic reconstruction and generate false positives in the detection of nucleotides under positive selection. The alignments used in our analyses are provided in Supplementary Data Text Files S1 and S2. Accession numbers of all sequences, their organ of expression and the method employed in expression assay (when available) are indicated in Supplementary Data Tables S1 and S2.

Phylogenetic analyses

From nucleotide alignments (1266 and 1512 nucleotide positions including gaps for SSU and LSU sequences, respectively), we first built a global phylogeny using Anabaena as outgroup, and then two phylogenies for each sub-unit (SSU or LSU) separately. For the latter phylogenies, we used P. patens as outgroup since it exhibited the lowest divergence from spermatophyta genes, allowing a better phylogenetic resolution. We compared trees obtained using different methods of reconstruction: Neighbor–Joining using PAUP (Swofford, 2003), Maximum Likelihood (ML) using PhyML v3 (Guindon et al., 2010) and the Bayesian method using MrBayes software (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003). For Neighbor–Joining trees, we used the Kimura two parameters distance model (Kimura, 1980). We used the General Time-Reversible model of sequence evolution (Yang, 1994) in ML, accommodating among-site heterogeneity of the mutation rate with gamma distributed substitution rates and a proportion of invariant sites I (GTR + Γ + I), as determined by MODELTEST (Posada and Crandall, 1998). We calculated bootstrap values for the ML reconstruction (Felsenstein, 1995) from 500 replicates for the phylogeny of the SSU paralogues. Because of the large number of sequences included in the phylogeny of the LSU paralogues, node robustness was estimated through an approximate likelihood ratio test that relies on the non-parametric Shimodaira–Hasegawa-like procedure (Guindon et al., 2010). For Bayesian reconstructions, we used a GTR + Γ + I with four chains and two independent runs for 106 generations, with sampling every 100 generations and 25 % burn in. Convergence was accepted when the average standard deviation of split frequencies was <1 %. In the SSU phylogeny, the basal clade encompassing three sequences (Perilla frutescens, A. thaliana and Arabidopsis lyrata) was poorly supported. We thus ignored it in our analyses and considered the divergence between monocots and dicots as the most ancestral node of interest in the SSU phylogeny (χ1, Fig. 1A).

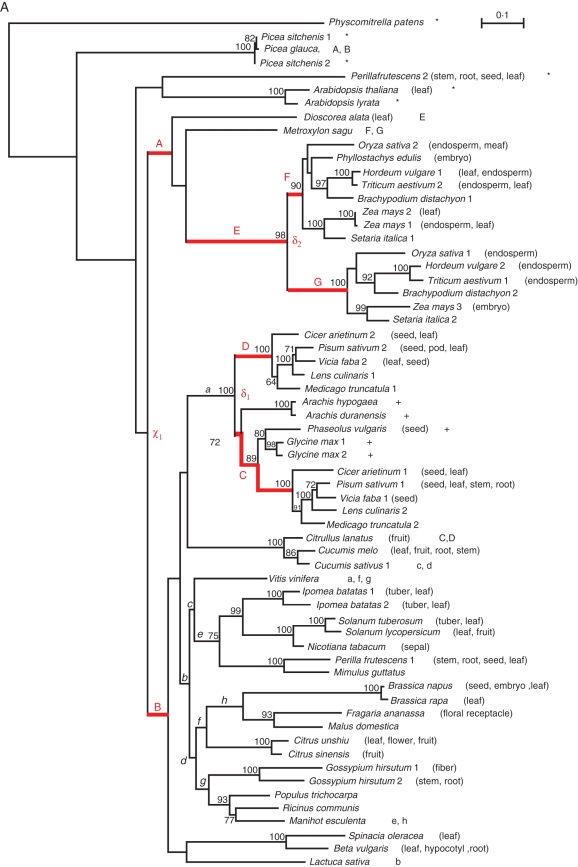

Fig. 1.

Maximum likelihood trees of angiosperm (A) small sub-unit (SSU) and (B) large sub-unit (LSU) sequences. Physcomitrella patens was used as the outgroup. Bootstrap values >60 % are indicated at each node. Branch lengths are proportional to the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (dS estimated using PAML). Sequences are identified by species names followed by a number when several paralogue sequences were available for the same species. The tissue where expression occurred is indicated in parentheses when available (see Supplementary Data Tables S1 and S2). Branches tested for accelerated evolution are indicated by red upper case (target branches from A to G and from A to R in SSU and LSU, respectively) and lower case (control branches from a to h, and from a to i in SSU and LSU, respectively) letters. Target and control branch letters are also reported next to the name of the outgroup sequence used for each test. δn, node corresponding to a duplication event, with n = 1 to 2 or 5 for SSU or LSU, respectively. χn, nodes corresponding to the divergence between monocots and dicots, with n = 1 and n = 1–3 for SSU and LSU, respectively. *, sequences removed when testing accelerated evolution in branches A and B for SSU and branches C and D for LSU. +, sequences removed when testing accelerated evolution in branches Q and R for LSU.

Detecting selection in protein-coding DNA sequences

Our aim was to detect heterogeneity in purifying selection among branches, a pattern expected under the DDC sub-functionalization, as well as evidence of accelerated evolution at particular codons along specific branches of the phylogeny, a pattern predicted if neofunctionalization or sub-functionalization via EAC has prevailed. In the global phylogeny (SSU + LSU), with the unique Anabaena AGPase gene as outgroup, the branch leading to the LSU clade exhibited substitution saturation (dS = 4·012, as estimated using the Branch model in PAML). Models relying on the infinite site assumption could therefore not be used (Ma et al., 2008) to test for departure from neutral evolution following the very first AGPase duplication, i.e. the one leading to the emergence of the two sub-units SSU and LSU. Instead, we investigated selection patterns independently within SSU and LSU after either duplication (δ) or divergence between monocots and dicots (χ). Thereby, for the SSU paralogues (Fig. 1A), we investigated selection patterns (1) after the divergence between monocots and dicots (branches A and B); (2) in branch E that specifically leads to grasses after the divergence from Metroxylon sagu; and (3) following duplication events in dicots (branches C and D from node δ1) and monocots (branches F and G from node δ2). Branch C covers a period of time equivalent to that covered by branch D, i.e. from node δ1 to the divergence of Cicer arietinum. In the same way for the LSU (Fig. 1B), we investigated selection patterns on branches following three duplication events (1) from node δ1, branches A and B as well as angiosperm-specific branches C and D; (2) branches E and F from node δ2; and (3) branches H and I from node δ3. Additionally selection was investigated following the divergence between monocots and dicots in branches J, K and L (branch L being specific for grasses) from node χ1, branch G from node χ2 and branches Q and R from node χ3. Since the position of monocots Dioscorea alata and Oncidium goldiana is poorly supported (77 %), they were removed from the analysis of branches Q and R. Depending on the targeted branch, we considered either the whole data set (63 SSU or 109 LSU gene sequences, including P. patens as outgroup), or only part of it in order to reduce computational time. When a reduced topology was used, an outgroup was taken from one of the closest clades (usually the sister clade) in order to maximize the precision in the inference of the ancestral state (Fig. 1). We verified the validity of our approach by changing the outgroup sequences in several analyses. We repeatedly found the same outcomes in terms of branches and sites under selection. In total, we targeted seven branches in SSU (denoted A–G in Fig. 1A) and 18 branches in LSU (denoted A–R in Fig. 1B).

For each analysis, we first determined the most parsimonious codon frequency model that fits the data using the Codonfreq option implemented in the codeml package under a unique ω model, PAML v4·1 (Yang, 2007). To do so, we compared nested models (Fequal < F1 × 4 < F3 × 4 < F61) using likelihood ratio tests (LRTs), and retained the F1 × 4 model for all analyses. Then, using the codeml package, we estimated the evolutionary rate ratio in each branch as ω, the ratio of the non-synonymous (dN) over the synonymous (dS) substitution rate. Under the Standard Neutral model of evolution, ω is equal to 1. An ω value significantly greater than 1 is indicative of positive selection, i.e. an increase in the rate of fixation of non-synonymous mutations, while an ω value significantly lower than 1 indicates purifying selection, i.e. an increase in the purge of non-synonymous mutations. We refer to branches for which we tested positive selection as the ‘foreground’ and all others as the ‘background’ branches.

To detect changes in selective pressure on particular branches we used the Branch model implemented in PAML (Yang, 1998; Yang and Nielsen, 1998) that allows ω to differ in one targeted branch in the phylogeny. We tested this model against a null hypothesis in which a single ω value was estimated in all branches (model M0), using a hierarchical LRT (hLRT). This model is expected to highlight major selective events that concern numerous amino acids. In order to detect changes in selection acting on a fraction of amino acids in a branch of interest, we used the Branch-Site model that allows ω to vary both among sites and among branches (Yang and Nielsen, 2002). The Branch-Site model A (MA) (Zhang et al., 2005) encompasses four classes of sites. In classes 0 and 1, sites respectively evolve under purifying selection (0 < ω0 < 1) or neutrality (ω1 = 1) in all branches or in the background branches only, and under positive selection in the foreground branches (ω2 > 1; classes 2a and 2b, respectively). The null Branch-Site model A (MA0) differs from MA for sites in classes 2a and 2b that are considered to evolve under neutrality in foreground branches (ω2 = 1). Therefore, comparing model MA with MA0 allows the detection of positive selection, through a 1 d.f. hLRT. Although we mainly focused on the latter test, an additional model was also used, M1a, that only considers the two first classes of sites (0 and 1) as either constraint (0 < ω0 < 1) or neutral (ω1 = 1) with identical ω in all branches. M1a may either be used as a null hypothesis to test the significance of MA0 through a 1 d.f. hLRT, thereby revealing relaxed constraints only; or, alternatively, M1a may be used as a null hypothesis to test the significance of MA through a 2 d.f. hLRT, thereby confounding both positive selection and relaxed constraints. When the only significant test compares MA and M1a, positive selection and relaxation of constraint cannot be distinguished. Finally, because several branches were tested for each sub-unit (seven and 18 for SSU and LSU, respectively), we calculated the false discovery rate (FDR) associated with each test (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995).

When positive selection was observed, whether it was in conjunction with relaxed constraints or not, we used the Bayes Empirical Bayes procedure (Yang et al., 2005) implemented for the Branch-Site model in the codeml package to estimate the posterior probability (PP) that a site has evolved under positive selection or relaxed constraints. Sites detected as evolving under positive selection are reported in Fig. 2 and named after the sub-unit (either SSU or LSU), the letter corresponding to the amino acid in the reference sequence (maize endosperm sub-unit) and the position in the reference protein. For instance, site LSU-D368 corresponds to an aspartic acid residue at position 368 in the reference sequence of the large sub-unit.

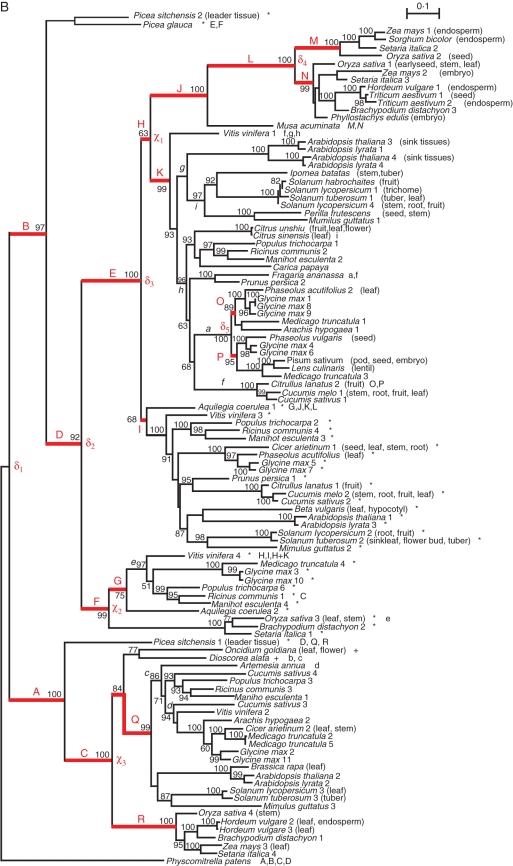

Fig. 2.

Position of residues exhibiting either accelerated evolution or coevolution. Positions are given along reference protein sequences of (A) the small (SSU) and (B) the large (LSU) sub-unit (accession nos AF330035 and S48563, respectively). Shaded boxes indicate motifs previously identified as being involved in protein activity, regulation or subunit interaction as follows. (A) 140–149, ATP-binding motif; 166–176, catalytic motif; 216–227, glucose-1-phosphate (G1P)-binding motif; 322–376, between-subunit interaction (BSI) motif; 458–the end, regulation motif. (B) 179–187, ATP-binding motif; 210–219, catalytic motif; 259–268, G1P-binding motif; 364–417, putative BSI motif, i.e. the region homologous to the SSU BSI domain; 499–the end, regulation motif. Letters above the sequence indicate the branch(es) in which sites were found to be under selection. We reported only sites with posterior probability (PP) (using the Bayes Empirical Bayes procedure) >0·90. Bold, sites with PP >0·95. Coevolving sites are denoted by a triangle for within-subunit and by an inverted triangle for between-subunit coevolution.

Testing coevolution among sites

Coevolution within and between SSU and LSU was detected as non-independent evolution among sites after correcting for the phylogeny using CoMap software v1·4·0 (Dutheil and Galtier, 2007). To investigate coevolution within each sub-unit, we used the two data sets of 62 and 108 spermatophyte protein sequences for SSU and LSU, respectively (no outgroup sequence is required) and their associated phylogenies as described above. To detect coevolution between sub-units, we concatenated the sequences of both sub-units for a given species and tissue of expression, leading to a 26 sequence alignment. Because the sub-unit phylogenies are different, with different numbers of duplication events occurring at different moments, we performed this analysis using the SSU or the LSU phylogeny alternately. We considered as significant only the groups of sites that were detected in both analyses. Two measures of coevolution were used (Dutheil and Galtier, 2007): (1) the correlation coefficient among substitution vectors of two sites, computed as the ‘expected’ number of substitutions that arose along branches of the tree; and (2) the compensation index which accounts for the possible compensating nature of the substitutions in terms of charge, volume, polarity or Grantham's distance (Grantham, 1974). We interpreted significance only for groups of sites with <5 % FDR as suggested by Dutheil and Galtier (2007). Because the Grantham's measure reflects an absolute distance between amino acids, we considered coevolution among sites as significant for this criterion only when volume, polarity and side chain composition all vary in opposite directions along the same branch(es).

RESULTS

We investigated the evolutionary history of AGPase SSUs and LSUs using phylogenetic reconstruction, with special emphasis on the history of the duplications and on the organs in which paralogous genes are expressed. All phylogenetic methods led to very similar topologies (data not shown), and we present results from the ML method only (Fig. 1A, B). Both phylogenies exhibited highly supported internal nodes. As the maximum values of dS were 0·79 and 0·91 for SSU and LSU, respectively, we considered the phylogenetic trees as non-saturated and relevant to perform the subsequent analyses.

Based on the SSU and LSU phylogenies, we defined as duplication the emergence of two clades that contain sequences from one or several common taxons. Although we may not have a complete picture of the successive duplications that led to the establishment of the AGPase multigenic family because available angiosperm sequences are biased towards grasses and core eudicots, both trees (Fig. 1A, B) exhibit evidence of several independent duplication events.

In the SSU phylogenetic tree, we identified two main duplications, δ1 among dicots and δ2 among monocots, and the corresponding branches (C, D, F and G) were tested for accelerated evolution. Additionally, several species-specific duplications arose in maize; Ipomea batatas, Gossypium hirsutum and Glycine max involved very few sequences each and were followed by terminal branches that were not tested (Fig. 1A).

At least 15 duplication events occurred along the LSU history, three of which occurred before the monocot–dicot divergence (δ1–δ3 in Fig. 1B). The first duplication event (node δ1) led to two sister clades, one clade containing 28 sequences mainly expressed in leaves (from branch A), and the other clade (from branch B) composed of 80 sequences mainly expressed in sink tissues (general sink tissues, or, more specifically, seed, endosperm, embryo, fruit or tuber). We showed that the difference in expression tissues exhibited a significant phylogenetic signal by randomly simulating 50 000 trees considering all paralogues and their associated character state (source, sink or both) using the Yule model implemented in Mesquite (Maddison and Maddison, 2003). Transitions and reversions were considered of identical weight. Forty steps were necessary to explain the character distribution over the topology presented in Fig. 1B, which appeared significantly lower than expected in random trees (P = 3·2 × 10−3).

AGPase paralogues of several Picea species were recently sequenced. Their inclusion in our phylogeny enabled us to discriminate between selective events occurring before or after the divergence between gymnosperms and angiosperms by separately testing branches A and C for paralogues expressed in source tissues, or B and D for paralogues mainly expressed in sink tissues.

The second LSU duplication δ2, at the edge of branch D, gave rise to a small clade of 11 sequences and a larger sister clade that underwent a third duplication (δ3). Note that the group derived from branch H was poorly supported (bootstrap value = 63 %, Fig. 1B), and therefore the age of duplication δ3 relative to the divergence between mocots and dicots remained questionable.

Finally, owing to the recent AGPase sequencing in Musa acuminata, we were able to determine that the last main duplication event (δ4) was not general to all monocots but most probably specific to grasses. This enabled us to address the question of accelerated evolution in the branch leading to grass genes mainly expressed in seed, endosperm or embryo (branch L, Fig. 1B). Similarly we tested branches emerging from a dicot-specific duplication (δ5, Fig. 1B).

We identified 11 other species- or genus-specific duplications across the LSU phylogeny. For the reason mentioned above, these duplications were not analysed.

Selection on the small sub-unit (SSU)

We used the SSU phylogeny to test for heterogeneity in purifying selection or accelerated evolution among paralogues, concentrating on nodes that correspond to monocot–dicot divergence (χ1) or gene duplication events (δ1 and δ2, Fig. 1A). For the sake of comparison we tested eight control branches, i.e. branches that were not targeted above and led to at least a four-sequence clade (see control branches a–h in Fig. 1A) using the Branch-Site model, and found no evidence of changes in evolutionary rate. In contrast, using the same model, evidence of relaxation of constraints was found in some target branches. First, when considering the paralogues derived from the legume-specific duplication (δ1, Fig. 1A), the Branch-Site model MA0 performed significantly better than model M1a in branch C, suggesting relaxation of constraints along this branch, although the FDR was 9·8 % (Table 1). Secondly, following the duplication that arose in grasses (node δ2, Fig. 1A), models MA and MA0 in branch G exhibited identical likelihood and both performed significantly better than model M1a (Table 1). This suggests that relaxation of constraints occurred along the branch that leads to paralogues expressed specifically in the endosperm, an organ known to have a specific starch metabolism with a cytosolic AGPase.

Table 1.

P-values (FDR in %) obtained from the likelihood ratio tests performed under the Branch-Site model on the small AGPase sub-unit (SSU) coding sequences

| Node* | Seq.† | Codons‡ | Branch§ | MA vs. M1a | MA vs. MA0 | MA0 vs. M1a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ1 | 57 | 343 | A | NS | NS | NS |

| – | – | – | B | NS | NS | NS |

| δ1 | 16 | 417 | C | NS | NS | 2·8 × 10−2 (9·8) |

| – | – | – | D | NS | NS | NS |

| – | – | 359 | E | NS | NS | NS |

| δ2 | 15 | 420 | F | NS | NS | NS |

| – | – | – | G | 2·2 × 10−2 (15·0) | NS | 5·8 × 10−3 (4·1) |

Each test is presented as the alternative hypothesis model vs. the null hypothesis model.

* Node upstream of the tested branch as reported in the phylogeny (Fig. 1A).

† Number of sequences used including the outgroup.

‡ Number of codons analysed.

§ Forward branch considered in the test as reported in the phylogeny (Fig. 1A).

NS, non-significant at a 5 % threshold.

Selection on the large sub-unit (LSU)

We found no evidence of selection along nine control branches (branches a–i, Fig 1B) while some target branches revealed either relaxation of constraints or positive selection under the Branch-Site model, as reported hereafter. The Branch model, in contrast, did not reveal accelerated evolution in any target branch (data not shown).

While we did not find evidence of variation in the rate of evolution immediately following the first duplication (δ1, Fig. 1B) in branches A and B, model MA fitted the data better than MA0 for branches C and D (Table 2), suggesting that positive selection accompanied the evolution of these paralogues in angiosperms. Along the angiosperm-specific branch C, positively selected sites had an ω = 109·61. The amino acid LSU-E228 exhibited PP to be under positive selection >95 %, and the amino acid LSU-R405, which belongs to the between-sub-unit interaction (BSI), exhibited PP > 90 % (Fig. 2B). Along the angiosperm-specific branch D, all three tests were significant, suggesting both relaxation of selection and accelerated evolution. Sites targeted by positive selection exhibited ω = 9·3 (model MA). Three sites had high PP: LSU-Q261 and LSU-F263 (PP > 95 %) that belong to the glucose-1-phosphate (G1P)-binding motif and LSU-D368 (PP > 90 %) that belongs to the BSI motif (Fig. 2B). At LSU-Q261, the serine residue in almost all paralogues expressed in leaves (except alanine for O. sativa 4) was smaller in volume compared with the ancestral state (tyrosine, glutamic and aspartic acid for P. patens, O. tauri and Anabaena sp., respectively), while it remained large (glutamine or histidine) among paralogues expressed in sink tissues, except in P. frutescens (leucine) and O. sativa 3 (aspartic acid). In addition, the ancestral state of the residue at this position was acidic, whereas residues were mainly polar neutral or basic for all derived states. At residue LSU-D368, the ancestral state was a small, polar and uncharged amino acid (serine) and remained exclusively neutral and small in paralogues derived from branch C (serine). In contrast, most paralogues derived from branch D exhibited a large and mainly acidic residue (either glutamic or aspartic acid).

Table 2.

P-values (FDR in %) obtained from the likelihood ratio tests performed under the Branch-Site model on the large AGPase sub-unit (LSU) coding sequences

| Node* | Seq.† | codoNS‡ | Branch§ | MA vs. M1a | MA vs. MA0 | MA0 vs. M1a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ1 | 109 | 315 | A | NS | NS | NS |

| – | – | – | B | NS | NS | NS |

| δ1 | 29 | 433 | C | 1·6 × 10−2 (4·8) | 3·2 × 10−2 (8·1) | NS |

| – | 80 | 317 | D | 5·1 × 10−3 (2·3) | 2·1 × 10−2 (7·7) | 2·1 × 10−2 (13·0) |

| δ2 | 79 | 317 | E | 1·5 × 10−2 (5·3) | 7·4 × 10−3 (4·4) | NS |

| – | – | – | F | 3·2 × 10−3 (1·9) | 8·2 × 10−3 (3·7) | 3·4 × 10−2 (15·0) |

| χ 2 | 12 | 341 | G | NS | NS | NS |

| δ3 | 68 | 318 | H | NS | NS | NS |

| – | – | 318 | I | NS | NS | NS |

| χ1 | 49 | 405 | J | NS | NS | NS |

| – | – | – | K | NS | NS | NS |

| – | – | – | L | 1·2 × 10−9 (2·2 × 10−6) | 3·1 × 10−3 (5·7) | 1·3 × 10−8 (2·3 × 10−5) |

| δ4 | 13 | 418 | M | NS | NS | NS |

| – | – | – | N | 2·2 × 10−2 (5·5) | 2·1 × 10−2 (6·4) | NS |

| δ5 | 13 | 434 | O | NS | NS | NS |

| – | – | – | P | NS | NS | NS |

| χ3 | 26 | 433 | Q | NS | NS | NS |

| – | – | – | R | 1·3 × 10−4 (0·1) | 5·1 × 10−3 (4·6) | 1·5 × 10−3 (1·3) |

Each test is presented as the alternative hypothesis model vs. the null hypothesis model.

* Node upstream of the tested branch as reported in the phylogeny (Fig. 1A).

† Number of sequences used including the outgroup.

‡ Number of codons analysed.

§ Forward branch considered in the test as reported in the phylogeny (Fig. 1A).

NS, non-significant at a 5 % threshold.

Following a second duplication δ2 (Fig. 1B), the Branch-Site model MA revealed that 1 % of sites were positively selected in branch E (ω = 51·19), while under constraints (ω = 0·093) or neutral in other branches. Sites under selection (Fig. 2B) included LSU-T142 (PP > 0·95). Along branch F, 2·7 % of sites were detected as positively selected (ω = 11·46), while under constraints (ω = 0·092) or neutral in other branches. The Branch-Site model revealed positive selection (PP > 0·95) at sites LSU-D270, LSU-R328 and LSU-K373, the latter belonging to the BSI domain.

The LSU paralogue mainly expressed in sink tissues experienced a drastic change in evolutionary rate in monocots after the divergence of M. acuminata (branch L, Table 2). In this branch leading to grasses, all three Branch-Site model comparisons were highly significant, suggesting that both accelerated evolution and relaxation of constraints had occurred. A total of 9·1 % sites were found under positive selection along branch L (ω = 4·024), while evolutionary constrained (ω = 0·097) or neutral in other branches. Three sites appeared to be positively selected: LSU-K445 (PP > 95 %), LSU-C424 and LSU-G155 (PP > 90 %). Following the last duplication event specific to grasses (node δ4, Fig. 1B), accelerated evolution was detected in branch N (Table 2), and the individual site LSU-T361 exhibited signs of positive selection (PP > 0·90; Fig. 2).

Finally, among the paralogues mainly expressed in source tissues (derived from branch A, Fig. 1B), contrasted patterns were observed between branches that follow node χ3. While no evidence of selection was found for branch Q that led to dicots, both accelerated evolution and relaxed constraints were detected in branch R that led to monocots. We report that 1·4 % of sites were positively selected on branch R (ω = 8·919), while under constraints (ω = 0·050) or neutral in other branches. Four sites were found to have undergone positive selection, three of them with PP > 0·95 (LSU-E175, LSU-H200 and LSU-N408), the other with PP > 0·90 (LSU-K394). LSU-K394 and LSU-N408 belong to the BSI domain (Fig. 2B).

Coevolution within sub-units

To test for coevolution between amino acids within each sub-unit, we investigated whether amino acid substitution patterns were correlated among paralogues, taking the physico-chemical properties of the amino acids into account. We weighted substitutions using either the amino acid volume, polarity or charge, or the Grantham distance between residues which combines volume, polarity and atomic side chain composition (Grantham, 1974). We tested for coevolution using both the correlation and compensation methods, and found mainly groups of two coevolving residues (Tables 3, 4). Some groups of 3–9 coevolving residues were also detected (Supplementary Data Table S3), but their biological interpretation remained difficult.

Table 3.

Coevolving residues within the small (SSU) and the large (LSU) AGPase sub-units

| Sub-unit | Method | Residues | P-values |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSU | Compensation – Grantham | G360–V461 | 2·8 × 10−4 |

| Correlation – Simple | T203–A204 | 4·1 × 10−3 | |

| Compensation – Grantham | E213–T236 | 8·7 × 10−4 | |

| Compensation – Grantham | N187–N429 | 1·2 × 10−3 | |

| Compensation – Charge | R331–N440 | 3·2 × 10−3 | |

| Compensation – Polarity | R201–V461 | 3·7 × 10−3 | |

| Compensation – Volume | F141–G225 | 4·1 × 10−3 | |

| Compensation – Charge | Y120–R244 | 4·1 × 10−2 | |

| LSU | Compensation – Charge | K265–L358 | 1·7 × 10−3 |

| Correlation – Simple | V413–K445 | 4·7 × 10−3 | |

| Compensation – Grantham | S141–L403 | 5·1 × 10−3 | |

| Compensation – Grantham | F134–S412 | 6·8 × 10−3 | |

| Compensation – Volume | F134–S412 | 8·0 × 10−3 |

Method indicates the correlation or compensation method implemented in CoMap – residue properties used to calculate correlation or compensation statistics.

Sites belonging to functionally known domains are highlighted in bold.

Table 4.

Coevolving residues between the small (SSU) and large (LSU) AGPase sub-units

| Residues |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| SSU | LSU | P-values | Compensation method |

| Y151 | I467 | 4·5 × 10−3 | Polarity |

| H299 | D400 | 4·6 × 10−3 | Charge |

| G118 | L383 | 4·8 × 10−3 | Grantham |

| H299 | D400 | 5·7 × 10−3 | Polarity |

| H299 | D400 | 9·4 × 10−3 | Grantham |

Sites belonging to the predicted between-sub-unit interaction domain of the LSU are indicated in bold.

P-values correspond to the most significant test, i.e. using the SSU phylogeny.

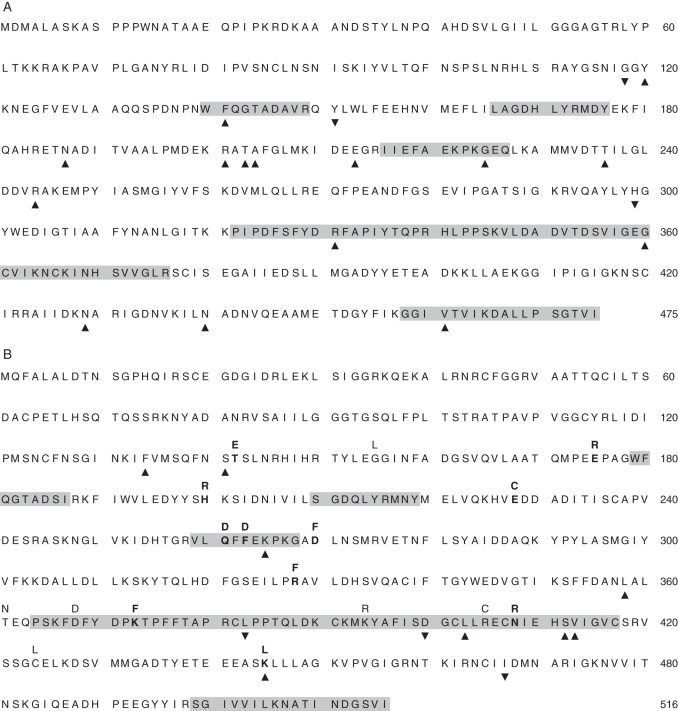

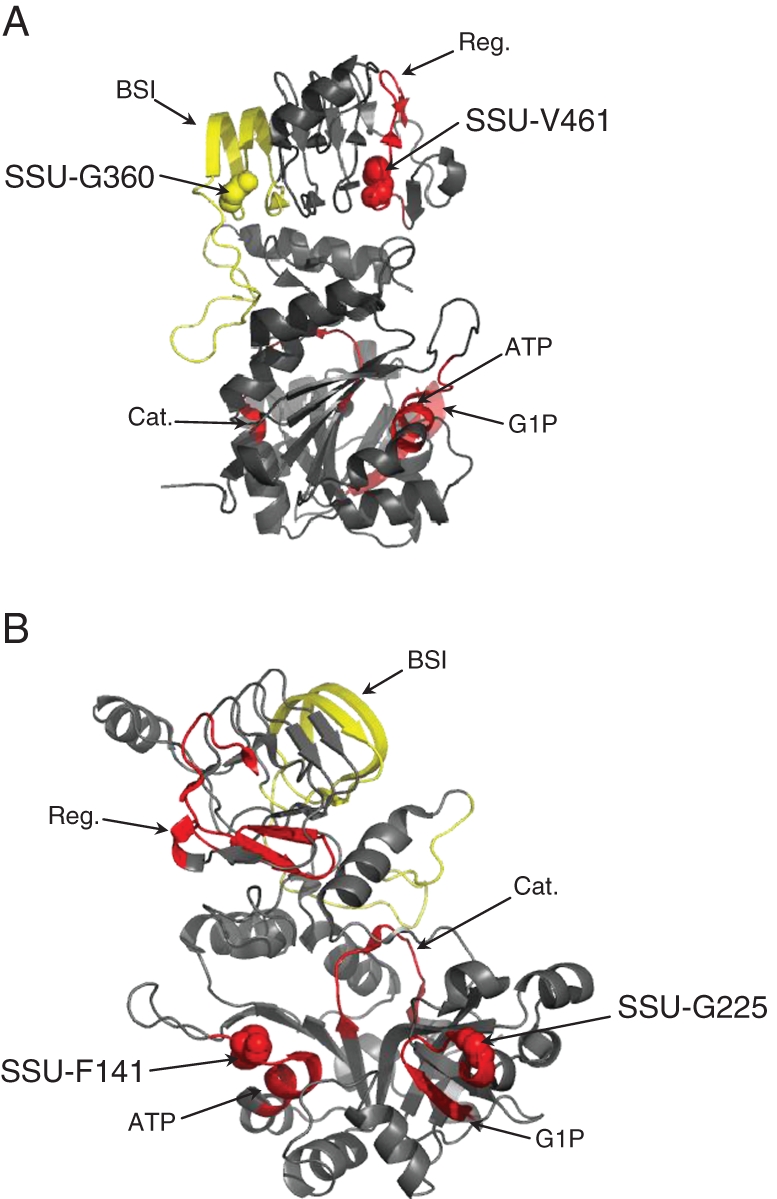

Among SSU genes, we detected a single two-site group of coevolving sites with the correlation method, and seven groups using the compensation method (Table 3). Four out of the seven groups exhibiting compensation included sites belonging to functionally known regions. The most significant group (P = 2·8 × 10−4; Table 3) was composed of site SSU-G360 that belongs to the SSU BSI motif and site SSU-V461 that belongs to the C-terminal regulatory region (Fig. 2A). These sites showed compensation for the Grantham index. The Citrus unshiu paralogue presented a phenylalanine residue at position 360, which corresponds to a massive decrease in polarity index (from 9·0 to 5·2), increase in volume (from 3 to 132) and decrease in side chain composition index (from 0·74 to 0·00) as compared with the glycine residue present in all other paralogues. This change appeared to be compensated by a transition from valine to aspartic acid at position 461 (polarity index from 5·9 to 13·0; volume from 84 to 54 and side chain composition from 0·00 to 1·38). These two sites were mapped in the 3-D crystallized structure of the SSU derived from Jin et al. (2005) (Fig. 3A). A second relevant coevolving group contained sites SSU-F141 (in the ATP-binding region) and SSU-G225 (in the G1P-binding region), both exhibiting volume compensation (Table 3; Fig. 3B). In I. batatas, reduction of volume at the amino acid at position SSU-F141 from 132 (phenylalanine) to 32 (serine) was compensated by an increase in volume at position SSU-G225 from 3 (glycine) to 124 (arginine).

Fig. 3.

Pairs of coevolving residues in the AGPase small sub-unit. Position of the coevolving residues SSU-G360 and SSU-V461 (A), and SSU-F141 and SSU-G225 (B), are given on the small sub-unit 3-D structure diagram from Jin et al. (2005). Coloured segments indicate functionally known domains. Cat, catalytic motif; Reg, regulatory motif; G1P, glucose-1-phosphate interaction motif; ATP, ATP-binding motif; BSI, between-sub-unit interaction motif.

Along the LSU amino acid sequence, one group was detected with the correlation approach and three groups were detected with the compensation approach. The most significant group (Table 3) was composed of site LSU-K265, which belongs to the G1P-binding motif, and site LSU-L358. At position LSU-K265, the sequence of Triticum aestivum expressed in the embryo underwent a decrease of charge, from a lysine (positive) to a glutamine (neutral), while it underwent an increase of charge at site LSU-L358, from a methionine/leucine neutral amino acid to a positively charged arginine. The two other groups included one site belonging to the BSI motif. The group composed of LSU-S141 and LSU-403 exhibited compensation according to the Grantham index mainly due to a decrease in volume. The paralogue of O. sativa expressed in the endosperm exhibited an increased volume at position LSU-S141 from a leucine (volume = 111) to a serine (volume = 32), simultaneously with a decreased volume at position LSU-L403 from a serine to a phenylalanine (volume = 132) or a leucine. The second group of interest was composed of LSU-F134 and LSU-S412. At position LSU-F134, the Cucumis melo 2 sequence presented a decrease in volume, i.e. a serine (volume = 32) instead of a phenylalanine (volume = 132) or a tyrosine (volume = 136), compensated by an increase in volume at position LSU-S412. All paralogues exhibited a serine (volume = 32) or threonine (volume = 61) at LSU-S412 while C. melo exhibited a leucine (volume = 111).

Between-sub-unit coevolution

Using the compensation methods, we detected three groups of coevolving residues, all significant using either the SSU or LSU phylogeny (Table 4). The most significant group contained two sites (SSU-Y151 and LSU-I467) exhibiting compensation by polarity. At residue SSU-Y151, all sequences presented a tyrosine (polarity 6·2) while the Fragaria ananassa paralogue presented a cysteine (polarity 5·5). This change was compensated through a substitution at residue LSU-I467, all sequences exhibiting an isoleucine (polarity 5·2) except the F. ananassa paralogue that exhibited a valine (polarity 5·9). Sites SSU-H299 and LSU-D400 coevolved with compensation for polarity, volume and Grantham index (Table 4). Site LSU-D400 belonged to the putative BSI motif and changed from aspartic acid to histidine in the Z. mays paralogue expressed in the endosperm, leading to a decrease in polarity and side chain composition index, and an increase in volume. This substitution was compensated by a substitution from histidine to aspartic acid in the same species at position SSU-H299. Finally, we detected coevolution between sites SSU-G118 and LSU-L383 with compensation according to the Grantham index, the latter position belonging to the BSI motif. At residue SSU-G118, all sequences presented a glycine (small, polarity 9·0) while the C. melo paralogue presented a tryptophan (large, polarity 5·4). This change was compensated through a substitution at residue LSU-L383, all sequences presenting a leucine (large, polarity 4·9) except the C. melo paralogue that exhibited a cysteine (medium, polarity 5·5).

DISCUSSION

AGPase encodes an essential function for carbohydrate storage in prokaryotes and plants. In prokaryotes a single gene encodes the AGPase (Ballicora et al., 2003), while green algae and land plants have at least two genes encoding this enzyme. Differences in the number of paralogues among angiosperms result from successive rounds of duplications, the first of which gave rise to partially separated functions in a small and a large sub-unit (Ballicora et al., 1995; Cross et al., 2004; Ventriglia et al., 2008). Subsequent rounds of duplications specific to each sub-unit were accompanied by the evolution of tissue-specific expression in some paralogues as well as a shift in sub-cellular compartment from an ancestral plastidial expression of AGPase in photosynthetic tissues toward a predominantly cytosolic expression in grass endosperm. Such changes indicate that sub-functionalization and neofunctionalization have probably contributed to the maintenance of duplicates in the AGPase multigenic family.

In order to gain new insights into the AGPase evolutionary history and to discriminate between different models of evolution, i.e. sub-functionalization under DDC or EAC and neofunctionaliation, we first compiled the largest data set of spermatophyta sequences and expression data for the two AGPase sub-units. Secondly, we tested for evidence of differential patterns of purifying selection as well as for evidence of selection driven by the fixation of beneficial mutations (positive selection) at particular branches and/or sites following major evolutionary events (duplication or divergence between monocots and dicots). In addition, we investigated the patterns of coevolution between amino acid residues within and among sub-units.

Phylogenies depict contrasting evolutionary histories between the two sub-units

The global phylogeny indicated saturation in the branch leading to the large sub-unit, preventing us from testing for accelerated evolution following the very first duplication leading to the two partly specialized sub-units SSU and LSU. We therefore built two independent phylogenies for the small and large sub-unit paralogues (Fig. 1A, B). All the well-supported duplications of the SSU occurred after the monocot–dicot divergence. In contrast, two or three duplications of the LSU pre-dated the divergence between monocots and dicots (node δ1–δ3, Fig. 1B), indicating that the ancestor of both monocots and dicots probably contained a single SSU paralogue and 3–4 LSU paralogues.

Overall, the SSU paralogues appeared more constrained than those of the LSU: (1) duplications were less numerous; (2) the average percentage of invariant residues was 64·1 % among SSU sequences and 21·6 % among LSU sequences, with shorter branches in the SSU phylogeny; and (3) the average evolutionary constraint was higher in SSU (ω = 0·029) than in LSU (0·091). Our results are therefore in good agreement with those of Georgelis et al. (2007, 2008) who reported a 2·7-fold higher ω among LSUs as compared with SSUs. These authors further suggested that SSUs experienced higher constraints because they are less tissue specific and generally form functional enzyme complexes with multiple LSUs (Georgelis et al., 2007).

The first LSU duplication led to the emergence of two clades with differential expression in angiosperms, one clade being composed of paralogues mainly expressed in leaves (from branch A, Fig. 1B) and the other of paralogues mainly expressed in sink tissues (from branch B, Fig. 1B). Within the ‘sink tissue’ clade, two successive duplications (nodes δ2 and δ3, Fig. 1B) exhibit strong evidence of non-functionalizations. Indeed, sequence from the A. thaliana fully sequenced genome was absent from the dicot clade emerging from branch G, and sequences of monocots – including the rice fully sequenced genome – were absent from the clade derived from branch I (Fig. 1B). Such loss of function has been shown to be the most common fate of duplicated genes (Lynch and Force, 2000). However, the evolutionary history of AGPase paralogues among angiosperms indicates that many duplication events in contrast led to the persistence and diversification of both paralogues, raising the question of the selective pressures they underwent.

Evolution of the SSU AGPase paralogues

Our results indicate that the SSU paralogues experienced very few changes in the rate of evolution accompanying the angiosperm radiation. Neither the duplication events nor the monocot–dicot divergence were followed by accelerated evolution. At most, relaxation of constraint was found along a few branches, in particular along branch G following δ2, a duplication that led to the emergence of two paralogues within grasses (Fig. 1A). Such relaxation of constraints suggests that the SSU duplication δ2 may have been followed by sub-functionalization through DDC. Overall, the SSU gene subfamily appears highly constrained and not prone to changes in evolutionary rates. As suggested by Georgelis et al. (2007, 2008), this may be due to the fact that, at the base of angiosperms, only one SSU protein was present and interacted with several LSUs.

In conjunction with a high level of constraint in the small sub-unit amino acid sequences, we found several pieces of evidence of coevolution between sites. Hence, using CoMap (Dutheil and Galtier, 2007) we were able to highlight co-substitutions that involve compensation for amino acid properties such as volume, charge or polarity, strongly indicating that they are driven by selection at the functional level. Interestingly, most of the involved amino acids belong to functionally known regions or motifs of particular conformation. Residues SSU-G360 and SSU-V461, for example, are located at each end of the same β-sheet complex structure (Fig. 3A), suggesting an important allosteric constraint in the protein conformation that may be affected by the amino acid substitution at one of these residues and compensated by substitution at the second one. Likewise, sites SSU-F141 and SSU-G225 (Fig. 3B) exhibited clear coevolution through compensation according to the volume. Those two sites are involved in the AGPase substrate-binding domain: site SSU-F141 is located in the ATP-binding motif and site SSU-G225 in the G1P-binding region. Given the importance of substrate affinity for allosterically regulated enzymes, our results indicate that selective pressures on both binding motifs led to concerted evolution.

Coevolution seems to occur mainly between residues that are either spatially or functionally related, suggesting that coevolution manifests structural or functional constraints of proteins (Yeang and Haussler, 2007). Indeed, in proteins subjected to high functional constraints such as SSU, we expect most non-synonymous mutations to be slightly deleterious, and then either selected against or compensated through coevolution, i.e. through compensatory mutations involving amino acid properties such as volume, charge or polarity that enable the recovery of the affected function (Mateu and Fersht, 1999; Mintseris and Weng, 2005). For instance, Mintseris and Weng (2005) have shown that residues involved in obligate interactions have a lower rate of substitution and a higher degree of coevolution than residues involved in transient interactions. In this context, the high rate of coevolution coupled with a lack of changes in evolutionary rate along branches probably results from a high level of selective constraints in SSU.

Evolution of the LSU paralogues

The most ancient LSU duplication (node δ1, Fig. 1B) led to two groups of paralogues with tissue specificity of expression, source (including leaves, stem or tuber) vs. sink (including roots, flowers, seeds or albumen). For each paralogue, no departure from neutral evolution was detected before the divergence between gymnosperms and angiosperms. However, after this divergence, accelerated evolution was found in the branch that leads to angiosperms for both paralogues (i.e. branches C and D, Fig. 1B). Their distinct expression pattern strongly suggests that sub-functionalization under the EAC model occurred after this duplication.

Site LSU-D368, which is located in the BSI domain (Fig. 2B), was found to have evolved under positive selection along branch D. Because this amino acid substitution implies physical and chemical changes in the BSI domain, it could have contributed to the modification of the BSI, thereby affecting AGPase regulation (Kamibayashi et al., 1991; Kim et al., 2007). Indeed, allosteric AGPase regulation has been shown to depend greatly upon the interaction between sub-units in potato (Kim et al., 2007) and Escherichia coli (Hwang et al., 2005, 2007). More importantly, Georgelis et al. (2009) have reported that the D to S mutation at the maize endosperm LSU-D368 position strongly affects kinetic and allosteric AGPase properties and glycogen production when expressed in E. coli, thus confirming the phenotypic role of amino acid variation at this position. Another site (LSU-Q261, Fig. 2B) was found to be under positive selection in branch D, again implying changes in physical and chemical properties. This residue belongs to the G1P-binding motif that determines the enzyme affinity for its substrate (Sivak and Preiss, 1998). Changes in substrate affinity by directed mutagenesis in the small sub-unit have been reported by Fu et al. (1998), but the specific role of the large sub-unit in G1P affinity remains unclear (Fu et al., 1998; Ballicora et al., 2004). Overall, we propose that changes in the organ of expression may have driven selection on AGPase for different effector sensitivities. Consistently, several authors have demonstrated that paralogues expressed in sink tissues showed less sensitivity to 3-phosphoglycerate and Pi than paralogues expressed in leaves (Plaxton and Preiss, 1987; Hylton and Smith, 1992; Weber et al., 1995).

Following the second LSU duplication (δ2, branch E and F), both paralogues exhibited accelerated evolution, again supporting sub-functionalization through EAC. Site LSU-K373, located within the BSI domain, was found to evolve under positive selection in branch F, indicating that the interaction domain is likely to be involved in the specialization of this paralogue.

Among LSU paralogues derived from branch E, we detected positive selection after monocot and dicot divergence in two consecutive branches: the one that led to the emergence of the grass paralogues (branch L, Fig. 1B) as well as the one that followed an additional duplication specific to grasses (branch N, Fig. 1B). Such accelerated evolution of the LSU paralogue that is specific to the Poaceae lineage suggests that this gene underwent neofunctionalization during the establishment of the specific starch synthesis pathway in grass kernels. None of the residues targeted by selection was located in functionally known domains.

Some of the residues detected in the present study (LSU-D368, LSU-Q261 and LSU-K445) were also detected by Georgelis et al. (2008). These authors used an unreasonably low PP threshold (0·5) in the detection of amino acids under selection. In contrast, we considered only PP > 0·9 or 0·95, as recommended by Yang et al. (2005). This obviously led Georgelis et al. (2008) to highlight many more amino acid positions than we did, among which only a sub-set may be biologically relevant. Note that the three residues commonly identified between the two studies could be used preferentially for functional validation using directed mutagenesis.

Coevolution between AGPase sub-units

Similarities between phylogenetic trees of interacting proteins is generally interpreted as evidence for coevolution, the rationale being that coevolution creates long-term correlation of evolutionary rates between two interacting genes (Pazos et al., 1997; Goh et al., 2000). While both AGPase sub-units strongly interact to achieve the enzyme function, they did not follow parallel evolutionary histories. In our attempt to test coevolution between sub-units by detecting non-independent evolution among sites correcting for the phylogeny (using CoMap; Dutheil and Galtier, 2007), we therefore took either the SSU or the LSU phylogeny as a reference, and presented only the results consistent across both analyses. This approach probably lacks power to detect coevolution along internal branches, since most of them are not conserved between phylogenies. Because the SSU duplications were on average more recent than that of the LSU, we expect the common history of pairs of paralogues currently expressed in a common organ/tissue of a given species to be better reflected by the phylogeny of the SSU. Consistent with this idea, all groups of residues detected using the SSU phylogeny were also detected with the LSU phylogeny, suggesting that the SSU phylogeny provides a more conservative test.

Coevolution between SSU and LSU residues highlights the important role of the BSI domain. Indeed, we report three cases of coevolution involving compensatory changes between sites of the small and the large sub-units, two of which involve LSU residues (LSU-L383 and LSU-D400) located within the putative BSI domain and an SSU residue spatially close to the interaction domain (SSU-H299). The BSI domain is a 55 amino acid domain involved in the interaction between sub-units. It has been well described in the SSU (Cross et al., 2005) and can be predicted in the LSU through homology and construction of the AGPase heterotetrameric structure (Tuncel et al., 2008). Overall, our results suggest that interacting domains between AGPase small and large sub-units, which are fundamental for the enzyme stability, activity and response to effectors (Cross et al., 2005; Hwang et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2007), have been largely targeted by selection and that compensatory mutations have occurred in these domains during the course of evolution.

Conclusions

In addition to some instances of non-functionalization, our results indicate that sub-functionalization via EAC and neofunctionalization have occurred during the evolution of the AGPase large sub-unit, accompanying its specialization of expression (source vs. sink tissues) and the emergence of the endosperm grass-specific paralogues. Moreover, interaction with both G1P and the small sub-unit has probably contributed to LSU specialization for tissue-specific expression by conferring specific regulatory properties. Because it remains challenging to detect differential selective pressures among branches or clades, evidence for sub-functionalization under the DDC model is more difficult to illustrate. Consistently, we found few cases of heterogeneity in selective pressures on different groups of paralogues, δδ in the LSU perhaps offering the most convincing example.

We confirmed that, in contrast to the evolutionary pattern of LSU, SSU evolved under strong constraints. In addition, our results show that coevolution played an important role in the evolution of SSU, probably allowing conservation of its function through compensatory mutations of interacting residues. Interestingly, coevolving sites lie more frequently than expected in functional domains. Indeed, in LSU half of them fall in functional domains (Table 3) that represent only 9 % of the residues (Fig. 2A), and in SSU six out of 16 coevolving residues (Table 3) fall in functional domains that represent only 22 % of the residues (Fig. 2B). Finally, we found evidence of coevolution between sub-units for residues lying in the BSI domain. Overall, our results sustain the key role of these functional domains in the evolution of AGPase. Furthermore, they suggest that CoMap could be advantageously applied to pinpoint candidate sites or regions of high evolutionary and functional importance in proteins even when functional domains are poorly characterized.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Guillaume Achaz and Gabriella Aguileta for their advice on the use of PAML as well as for helpful discussions regarding the interpretation of PAML outputs, to Jean-Louis Prioul for interesting discussions about AGPase evolution, and to Hélène Citerne for English style and grammar improvement. We thank anonymous reviewers for thoughtful comments that helped us improve the manuscript. This work was supported by a grant from the Bureau des Ressources Génétiques (project no. 8 2005-2007) to D.M. and a grant from the Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-05-JCJC-0067-01) to M.I.T. J.C. was financed by a PhD fellowship from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. M.I.T. and D.M. contributed equally to the supervision of this work.

LITERATURE CITED

- Aguileta G, Bielawski JP, Yang Z. Evolutionary rate variation among vertebrate beta globin genes: implications for dating gene family duplication events. Gene. 2006;380:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschuh D, Lesk AM, Bloomer AC, Klug A. Correlation of co-ordinated amino acid substitutions with function in viruses related to tobacco mosaic virus. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1987;193:693–707. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90352-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atchley WR, Wollenberg KR, Fitch WM, Terhalle W, Dress AW. Correlations among amino acid sites in bHLH protein domains: an information theoretic analysis. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2000;17:164–178. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballicora MA, Laughlin MJ, Fu Y, Okita TW, Barry GF, Preiss J. Adenosine 5′-diphosphate-glucose pyrophosphorylase from potato tuber Significance of the N terminus of the small subunit for catalytic properties and heat stability. Plant Physiology. 1995;109:245–251. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.1.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballicora MA, Fu YB, Nesbitt NM, Preiss J. ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase from potato tubers Site-directed mutagenesis studies of the regulatory sites. Plant Physiology. 1998;118:265–274. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballicora MA, Iglesias AA, Preiss J. ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase, a regulatory enzyme for bacterial glycogen synthesis. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 2003;67:213–225. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.67.2.213-225.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballicora MA, Iglesias AA, Preiss J. ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase: a regulatory enzyme for plant starch synthesis. Photosynthesis Research. 2004;79:1–24. doi: 10.1023/B:PRES.0000011916.67519.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baris I, Tuncel A, Ozber N, Keskin O, Kavakli IH. Investigation of the interaction between the large and small subunits of potato ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. PLoS Computational Biology. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000546. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000546 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckles DM, Smith AM, ap Rees T. A cytosolic ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase is a feature of graminaceous endosperms, but not of other starch-storing organs. Plant Physiology. 2001;125:818–827. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.2.818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beisswanger S, Stephan W. Evidence that strong positive selection drives neofunctionalization in the tandemly duplicated polyhomeotic genes in Drosophila. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2008;105:5447–5452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710892105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benderoth M, Textor S, Windsor AJ, Mitchell-Olds T, Gershenzon J, Kroymann J. Positive selection driving diversification in plant secondary metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2006;103:9118–9123. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601738103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Chao JA, Patskovsky Y, Almo SC, Singer RH. Structural basis for the coevolution of a viral RNA–protein complex. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. 2008;15:103–105. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke ND. Covariation of residues in the homeodomain sequence family. Protein Science. 1995;4:2269–2278. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparot-Moss S, Denyer K. The evolution of the starch biosynthetic pathway in cereals and other grasses. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2009;60:2481–2492. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conant GC, Wolfe KH. Turning a hobby into a job: how duplicated genes find new functions. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2008;9:938–950. doi: 10.1038/nrg2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross JM, Clancy M, Shaw JR, et al. A polymorphic motif in the small subunit of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase modulates interactions between the small and large subunits. The Plant Journal. 41:501–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross JM, Clancy M, Shaw JR, et al. Both subunits of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase are regulatory. Plant Physiology. 2004;135:137–144. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.036699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denyer K, Dunlap F, Thorbjornsen T, Keeling P, Smith AM. The major form of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase in maize endosperm is extra-plastidial. Plant Physiology. 1996;112:779–785. doi: 10.1104/pp.112.2.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Marais DL, Rausher MD. Escape from adaptive conflict after duplication in an anthocyanin pathway gene. Nature. 2008;454:762–765. doi: 10.1038/nature07092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps P, Colleoni C, Nakamura Y, et al. Metabolic symbiosis and the birth of the plant kingdom. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2008;25:536–548. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte JM, Cui L, Wall PK, et al. Expression pattern shifts following duplication indicative of subfunctionalization and neofunctionalization in regulatory genes of Arabidopsis. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2006;23:469–478. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutheil J, Galtier N. Detecting groups of coevolving positions in a molecule: a clustering approach. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2007;7:242. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-242. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-7-242 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fares MA, McNally D. CAPS: coevolution analysis using protein sequences. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2821–2822. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP: phylogeny inference package. Seattle: University of Washington; 1995. Version 3·57c. [Google Scholar]

- Flagel L, Wendel J. Gene duplication and evolutionary novelty in plants. New Phytologist. 2009;183:557–564. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Force A, Lynch M, Pickett FB, Amores A, Yan YL, Postlethwait J. Preservation of duplicate genes by complementary, degenerative mutations. Genetics. 1999;151:1531–1545. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frueauf JB, Ballicora MA, Preiss J. ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase from potato tuber: site-directed mutagenesis of homologous aspartic acid residues in the small and large subunits. The Plant Journal. 2003;33:503–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Ballicora MA, Preiss J. Mutagenesis of the glucose-1-phosphate-binding site of potato tuber ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Plant Physiology. 1998;117:989–996. doi: 10.1104/pp.117.3.989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgelis N, Braun EL, Shaw JR, Hannah LC. The two AGPase subunits evolve at different rates in angiosperms, yet they are equally sensitive to activity-altering amino acid changes when expressed in bacteria. The Plant Cell. 2007;19:1458–1472. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.049676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgelis N, Braun EL, Hannah LC. Duplications and functional divergence of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase genes in plants. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2008;8:232. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-8-232 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgelis N, Shaw JR, Hannah LC. Phylogenetic analysis of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase subunits reveals a role of subunit interfaces in the allosteric properties of the enzyme. Plant Physiology. 2009;151:67–77. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.138933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloor GB, Martin LC, Wahl LM, Dunn SD. Mutual information in protein multiple sequence alignments reveals two classes of coevolving positions. Biochemistry. 2005;44:7156–7165. doi: 10.1021/bi050293e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh CS, Cohen FE. Co-evolutionary analysis reveals insights into protein–protein interactions. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2002;324:177–192. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh CS, Bogan AA, Joachimiak M, Walther D, Cohen FE. Co-evolution of proteins with their interaction partners. Journal of Molecular Biology. 2000;299:283–293. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grantham R. Amino acid difference formula to help explain protein evolution. Science. 1974;185:862–864. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4154.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene TW, Chantler SE, Kahn ML, Barry GF, Preiss J, Okita TW. Mutagenesis of the potato ADPglucose pyrophosphorylase and characterization of an allosteric mutant defective in 3-phosphoglycerate activation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 1996;93:1509–1513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3·0. Systematic Biology. 2010;59:307–321. doi: 10.1093/sysbio/syq010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn MW. Distinguishing among evolutionary models for the maintenance of gene duplicates. Journal of Heredity. 2009;100:605–617. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esp047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halabi N, Rivoire O, Leibler S, Ranganathan R. Protein sectors: evolutionary units of three-dimensional structure. Cell. 2009;138:774–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah LC, Shaw JR, Giroux MJ, et al. Maize genes encoding the small subunit of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Plant Physiology. 2001;127:173–183. doi: 10.1104/pp.127.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks JH, Kolbe A, Gibon Y, Stitt M, Geigenberger P. ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase is activated by posttranslational redox-modification in response to light and to sugars in leaves of Arabidopsis and other plant species. Plant Physiology. 2003;133:838–849. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.024513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MA, Kaufmann K, Otero J, Preiss J. Biosynthesis of bacterial glycogen. Mutagenesis of a catalytic site residue of ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase from Escherichia coli. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:12455–12460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes AL. The evolution of functionally novel proteins after gene duplication. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1994;256:119–124. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SK, Salamone PR, Okita TW. Allosteric regulation of the higher plant ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase is a product of synergy between the two subunits. FEBS Letters. 2005;579:983–990. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SK, Hamada S, Okita TW. Catalytic implications of the higher plant ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase large subunit. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:464–477. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hylton C, Smith AM. The rb mutation of peas causes structural and regulatory changes in ADP glucose pyrophosphorylase from developing embryos. Plant Physiology. 1992;99:1626–1634. doi: 10.1104/pp.99.4.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin X, Ballicora MA, Preiss J, Geiger JH. Crystal structure of potato tuber ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. EMBO Journal. 2005;24:694–704. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamibayashi C, Estes R, Slaughter C, Mumby MC. Subunit interactions control protein phosphatase 2A. Effects of limited proteolysis, N-ethylmaleimide, and heparin on the interaction of the B subunit. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1991;266:13251–13260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Hwang SK, Okita TW. Subunit interactions specify the allosteric regulatory properties of the potato tuber ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2007;362:301–306. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.07.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondrashov FA, Rogozin IB, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. Selection in the evolution of gene duplications. Genome Biology. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-2-research0008. research0008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/gb-2002-3-2-research0008 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]