Abstract

The apical Na+/H+ exchanger (NHE) isoform NHE2 is involved in transepithelial Na+ absorption in the intestine. Our earlier studies have shown that mitogenic agent phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) induces the expression of NHE2 through activation of transcription factor early growth response-1 (Egr-1) and its interactions with the NHE2 promoter. However, the signaling pathways involved in transcriptional stimulation of NHE2 in response to PMA in the intestinal epithelial cells are not known. Chemical inhibitors and genetic approaches were used to investigate the signaling pathways responsible for the stimulation of NHE2 expression by PMA via Egr-1 induction. We show that, in response to PMA, PKCδ, a member of novel PKC isozymes, and MEK-ERK1/2 pathway of mitogen-activated protein kinases stimulate the NHE2 expression in C2BBe1 intestinal epithelial cells. PMA rapidly and transiently induced activation of PKCδ. Small inhibitory RNA-mediated knockdown of PKCδ blocked the stimulatory effect of PMA on the NHE2 promoter activity. In addition, blockade of PKCδ by rottlerin, a PKCδ-specific inhibitor, and ERK1/2 by U0126, a MEK-ERK inhibitor, abrogated PMA-induced Egr-1 expression. Immunofluorescence studies revealed that inhibition of ERK1/2 activation prevents translocation of PMA-induced Egr-1 into the nucleus. Consistent with these data, PMA-induced Egr-1 interaction with the NHE2 promoter region was prevented in nuclear extracts from U0126-pretreated cells. In conclusion, our data provide the first evidence that the stimulatory effect of PMA on NHE2 expression is mediated through the initial activation of PKCδ, subsequent PKCδ-dependent activation of MEK-ERK1/2 signaling pathway, and stimulation of Egr-1 expression. Furthermore, we show that transcription factor Egr-1 acts as an intermediate effector molecule that links the upstream signaling cues to the long-term stimulation of NHE2 expression by PMA in C2BBe1 cells.

Keywords: Na+/H+ exchanger, signal transduction pathway, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, early growth response-1

na+/h+ exchangers (nhe) are the predominant electroneutral Na+ absorptive mechanism in the mammalian ileum and colon. The NHEs are a family of nine integral membrane proteins; each protein is encoded by a distinct gene and is localized on a separate chromosome. These proteins catalyze the countertransport of one extracellular Na+ for one intracellular H+ across the plasma membrane and display different cell and subcellular distributions. NHEs are important contributors to a number of cellular functions including the maintenance of internal pH (pHi) homeostasis, cell volume regulation, and Na+ absorption. NHE family members are composed of a highly conserved NH2 terminus ion-transporting domain, which spans the membrane 10–12 times, and a highly divergent COOH terminus that is involved in regulation of NHE activity by various stimuli (27, 31, 52).

Of the nine NHE isoforms, NHE1, 2, 3, and 8 have been described in the human intestinal epithelial cells. NHE1 is ubiquitously expressed and serves a housekeeping function. In the intestinal epithelial cells, NHE1 is localized to the basolateral membrane, whereas NHE2, 3, and 8 are localized to the apical membrane, where they are involved in transepithelial Na+ absorption. NHE2 and NHE3 potentially serve the same function in the intestinal Na+ absorption with varying activities in different segments of the gastrointestinal tract, as NHE2 is predominantly expressed in the colon, whereas NHE3 is highly expressed in the ileum (12). NHE8 has been implicated in Na+ absorption in the early developmental stages (6, 47).

Binding of growth factors to their receptors or activation of G protein-coupled receptors by their respective ligands induce hydrolysis of membrane lipids, leading to increased production of 1,2 diaceylglycerol (DAG). DAG is an endogenous activator of protein kinase C (PKC). PKC family of serine/threonine kinases is comprised of 11 different isozymes. These isozymes are classified as conventional PKCs (cPKCs), novel (nPKCs), and atypical (aPKCs) based on their structural similarities and cofactor requirements (10, 41). Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), a diaceylglycerol structural analog, mimics DAG and modulates diverse cellular functions by direct binding to the DAG-binding site of the cPKCs and nPKCs (16, 42). As such, PMA bypasses the initial steps in signal transduction pathways utilized by mitogenic stimuli and can activate PKC isozymes directly. PMA-responsive region has been identified on the COOH terminus of NHE2 polypeptide, which mediates the short-term effects of PMA on the NHE2 transport activity (40, 51). NHE2 activity is upregulated by PMA in various cell systems (26, 40). These effects were demonstrated to occur via activation of the PKC pathway (26).

Previously we reported the presence of a cis-element in the NHE2 promoter that mediates the positive regulation of NHE2 transcription in response to PMA (36). By functional and mutational assays we mapped the PMA-responsive region to the promoter region between bp −415 to −227. PMA responsiveness was further localized to a PMA response element (PRE) at nucleotides −339 to −324, and these findings were corroborated by mutational analyses of PRE in transient transfection assays (36). The NHE2-PRE motif, which is composed of overlapping binding sites for specificity protein-1 (Sp1) and early growth response-1 (Egr-1), interacts with transcription factors Sp1 and Sp3 in the basal growth conditions and Egr-1 in response to PMA (36, 43).

In the present report, we have extended our studies to explore the signal transduction pathways responsible for the PMA effect on the transcriptional activity of NHE2. We demonstrate that PMA triggers activation of a signaling cascade, where phosphorylation of nPKCδ results in activation of extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase-1 and -2 (ERK1/2) and subsequent induction of Egr-1. Subsequently, Egr-1 directly targets NHE2 promoter and promotes NHE2 transcriptional upregulation by interaction with NHE2-PMA response element.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Materials.

Lipofectamine 2000 was purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Gö6976, Gö6850, Gö6983, Rottlerin, U0126, LY294002, and PMA were purchased from EMD Chemicals (Gibbstown, NJ). Phospho-PKCδ, PKCδ, and Egr-1 antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Phospho-ERK1/2 and ERK antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Actin and tubulin antibodies were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). The Gel Shift Assay Core System was purchased from Promega (Madison, WI).

Cell culture.

C2BBe1 cell line, a subclone of Caco-2 human colonic epithelial cells, was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Rockville, MD) and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 10 μg/ml transferrin as described previously (34). C2BBe1 cells undergo spontaneous differentiation as determined by the appearance of dome-shaped structures characteristic of microvilli and the presence of markers of intestinal epithelial cell differentiation (44). These cells have been used extensively to investigate the regulation of Na+ absorption by NHE isoforms at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels.

Transient transfection and reporter assays.

In transient transfection studies, 1.5 × 105 cells/well were seeded on 12-well culture plates and transfected the next day with NHE2 promoter-luciferase constructs, p-1051/+150 (Fig. 1A) or p-415/+150, using Lipofectamine-2000 reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Luciferase activities were measured 48 h posttransfection in 20 μg of total cell proteins using GLOMAX Luminometer (Promega) and expressed as percentage of the control. Protein concentrations were determined using Bradford Assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) as described by the manufacturer.

Fig. 1.

Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-induced Na+/H+ exchanger 2 (NHE2) promoter activity is triggered by activation of novel PKC. A: schematic illustration of the NHE2 5′-flanking region harbored in p-1051/+150, NHE2 promoter-reporter construct. The relevant cis-elements are shown. C2BBe1 cells were transiently transfected with p-1051/+150 and treated with or without PMA (100 nM, 16 h). To examine the effects of signaling pathways, before PMA treatment some samples were treated with pathway-specific inhibitors (5 μM each): Gö6976 (B), Gö6983 (C), and Gö6850 (D) for 1 h. Luciferase activities were determined 48 h posttransfection as described in materials and methods. Data are presented as means ± SE and are representative of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. Asterisks denote differences between PMA vs. inhibitor-plus PMA treatments and are statistically significant at P < 0.05. PRE, PMA response element. Egr-1, early growth response-1; Sp1, specificity protein-1.

For experiments involving the use of pharmacological inhibitors, cells were grown in serum-reduced media (0.5% FBS) for 20–24 h and then exposed to various concentrations of inhibitors (as indicated in the text) for 1 h before addition of PMA (100 nM). Subsequently, cells were maintained in the presence of the inhibitor and PMA for 16 h. Forty-eight hours posttransfections, cells were lysed, and luciferase activity was determined as described above. Control cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) at 0.1% final concentrations. All transfections were performed in triplicate and repeated at least three times.

siRNA transfection.

For small RNA interference studies, C2BBe1 cells were transfected with PKCδ-specific siRNA (20 nM) and control nontargeting siRNA (20 nM) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) using transfection reagents from Bio-Rad as recommended by the manufacturer. After 24 h cells were transfected again with p-415/+150, serum starved overnight, and then incubated with or without PMA (100 nM) for additional 16 h. Cells were collected 48 h after transfection with p-415/+150, and cell lysates were prepared and used for luciferase assays.

Protein extraction and immunoblottings.

For whole cell lysate preparations, C2BBe1 cells were grown to about 90% confluence and then serum deprived for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were treated with different inhibitors for 1 h followed by addition of PMA for various time intervals as indicated in the text. Cells were washed with 1× PBS, centrifuged at 3,000 g for 5 min, and lysed on ice for 30 min in RIPA buffer (Sigma Aldrich) supplemented with 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). The cell lysates were centrifuged at 13,000 g at 4 °C for 10 min to remove cell debris, and supernatants containing the total cell proteins were collected. The protein concentrations were measured using the Bradford assay. Protein extracts (25 μg of total cell proteins) were subjected to 8% or 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Immobilon-P; Millipore, Bedford, MA). Specific antigens were immunodetected using appropriate primary and secondary antibodies and visualized using Enhanced Chemiluminescence detection reagents (ECL Plus; GE Healthcare, London, UK).

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy.

C2BBe1 cells were grown on glass coverslips in 12-well culture dishes to ∼90% confluence. After serum starvation (16–24 h), cells were preincubated with or without ERK inhibitor U0126 (50 μM) for 30 min, incubated in the presence or absence of PMA for 2 h, and subsequently fixed with 1% (vol/vol) paraformaldehyde in PBS, pH 7.4, for 60 min at ambient temperature. After fixation, slides were washed one time each in 1× PBS, 50 mM ammonium chloride, and 1× PBS. Cells were incubated in blocking buffer (1× PBS/3% normal goat serum/0.05% saponin) for 30 min. Then cells were incubated with Egr-1 antibody (Santa Cruz) diluted to 1:100 for 1 h at room temperature, washed with 1× PBS/0.05% saponin three times, and incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Invitrogen) at 1:300 dilution, for 60 min at room temperature. The nuclei were stained with DAPI (300 nM) in 1× PBS for 2 min. One drop of mounting medium was applied to each coverslip and mounted on slides. Images were obtained on Carl Zeiss LSM 510 META laser scanning confocal microscope. A ×63 water immersion objective was used with the pinhole set at 1 Airy unit. The Alexa Fluor (green) and DAPI (blue) probes were excited at 488 nm with an Argon laser (30 mW) at 7.7% laser intensity or 405 nm Diode laser (25 mW) at 4.8% laser intensity, respectively, and detected through the appropriate emission filters. The sampling time was 1.6 μs per frame. During imaging, the laser intensity and the scanning speed were kept constant to avoid different levels of photobleaching. For XY sections, focal planes were adjusted to level of the nucleus, and single sections were taken at 0.5 μM thickness. For ZY sections, serial images of confocal optical sectioning with 0.5 μM steps were collected and computer reconstructed using Zeiss LSM Image Browser.

Gel mobility shift assay and nuclear extract preparation.

DNA-protein binding reactions were carried out as described previously (36). Briefly, 5 μg of the nuclear extracts was incubated with reaction buffer at 50,000 counts per min (cpm) of the probe at room temperature for 20 min. The samples were resolved on a 5% native polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× TBE buffer. Gels were dried and visualized using autoradiography. For competition assay, unlabeled oligonucleotides were used at 100-fold molar excess over the labeled probes. For supershift assays, after incubation with the labeled probe, 1 μl (2 μg/reaction) of the antibody of interest was added to the DNA-protein suspension and incubated for additional 30 min at room temperature before gel electrophoresis. Nuclear extract preparations were carried out using NucBuster Extraction Kit (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions. The double-stranded oligonucleotide probe corresponding to the NHE2 PRE at bp −339 to −324 was end-labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA) using T4-polynucleotide kinase (Promega) and purified with G-25 quick spin mini columns (Roche). To prepare nuclear extract from U0126-treated cells, serum-starved cells were exposed to U0126 (50 μM) for 1 h followed by treatment with PMA (100 nM) in the presence of the inhibitor for an additional 2 h. For Western blot analyses, 15–20 μg per lane of nuclear proteins were used.

Statistical analysis.

Data are presented as means ± SE. The difference between two groups was evaluated by Student's t-test. Data were deemed significant when P < 0.05.

RESULTS

PKCδ mediates the PMA-induced transcriptional activation of the NHE2 promoter.

The cPKC and nPKC isozymes are the most prominent cellular receptors for PMA (41). To determine whether these isozymes were involved in transcriptional activation of NHE2 promoter by PMA, we initially investigated the effects of three different chemical inhibitors with specificity to either cPKCs alone or to both cPKCs and nPKCs. C2BBe1 cells were transiently transfected with NHE2 promoter-reporter construct p-1051/+150 (Fig. 1A) and, after pretreatment with Gö6976, Gö6983, or Gö6850 (1 h, 5 μM each), further incubated with or without PMA (100 nM, 16 h). Gö6976 is a selective inhibitor for cPKCs and even in high concentration does not affect the nPKCs or aPKCs, whereas Gö6983 and Gö6850 not only prevent activation of the cPKCs and nPKC isozyme PKCδ, but also the former inhibits aPKCζ and the latter inhibits the nPKCϵ (7, 25, 38). As shown in Fig. 1B, inhibition of cPKCs by Gö6976 showed only minor inhibitory effect on the PMA-induced NHE2 promoter activity, whereas both Gö6983 and Gö6850 completely abrogated the stimulatory effect of PMA on the NHE2 transcriptional activity (Fig. 1, C and D). None of the inhibitors used alone affected the basal activity of the NHE2 promoter compared with the untreated control. These results suggested that, because PKCδ is commonly inhibited with both inhibitors, it might be responsible for mediating the stimulatory effect of PMA on the NHE2 expression.

siRNA targeted to PKCδ represses PMA-induced stimulation of NHE2 promoter activity.

To verify the involvement of PKCδ in mediating the stimulatory effect of PMA on the NHE2 transcriptional activity, we used PKCδ-specific siRNA to block the expression of PKCδ. As shown in Fig. 2, transfection of PKCδ siRNA blocked the PMA-induced activation of NHE2 promoter activity by ∼60%, whereas nontargeting control siRNA showed no effect. The lack of complete inhibition of promoter activity by PKCδ-specific siRNA may be indicative of incomplete inhibition of the PKCδ; however, we cannot rule out the possibility that other protein kinases or PKC isozymes may be involved.

Fig. 2.

siRNA-mediated PKCδ knockdown blocks PMA-induced NHE2 promoter activity. C2BBe1 cells were transiently transfected with PKCδ siRNA before transfection with p-415/+150. Cells were incubated in serum-reduced media for 16 h before PMA treatment. Cells were either treated with 100 nM PMA or vehicle. Cells were collected 48 h after transfection, and luciferase activities were determined in 10 μg of total cell proteins. The results are presented as average of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate (n = 3). Asterisk indicates differences between luciferase activities of the PMA-treated control siRNA transfected cells vs. similarly treated cells transfected with PKCδ siRNA, P < 0.05.

PMA induces the activation of PKCδ in C2BBe1 cells.

Activation of different PKC isozymes involves the phosphorylation of specific serine and threonine residues. To examine the effects of PMA on PKCδ activation, C2BBe1 cells were exposed to PMA (100 nM) for 5 min to 6 h and cell lysates tested for the activation of PKCδ by phosphorylation. An antiphospho-PKCδ antibody was used to detect the phosphorylation at Thr-507 in the activation loop of PKCδ. As shown in Fig. 3A, PKCδ phosphorylation in response to PMA was biphasic and displayed two peaks. The first phase of phosphorylation was rapid and transient; maximum activation was observed by 5 min of PMA treatment and declined by 10–15 min. The second peak of PKCδ phosphorylation occurred 6 h post-PMA treatment, and the phosphorylation declined to the basal levels by 16 h (data not shown). The biphasic activation correlated with Thr-507 phosphorylation that is located in the activation domain of PKCδ. The total PKCδ remained relatively unaltered during PMA stimulation. Taken together, these findings suggested an essential role for PKCδ in PMA-induced upregulation of NHE2 expression.

Fig. 3.

PMA stimulates PKCδ phosphorylation. C2BBe1 cells were serum deprived overnight and treated with PMA (100 nM) (A) for various time points or with Gö6850 (B) (1, 2.5, and 5 μM) for 1 h before addition of PMA for 5 min. Total cell lysates (TCL) were prepared, and 20 μg/lane were resolved on a 10% SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis performed as described in materials and methods using phospho-PKCδ (Thr-507) antibody. The blot in A was stripped and reprobed with anti-Pan-PKCδ as loading control. A similarly loaded gel was used as a loading control and probed with actin in B.

To assess the effect of Gö6850 on the phosphorylation of PKCδ by PMA, cells were pretreated with different doses of the inhibitor and incubated in the absence or presence of PMA for 5 min. Gö6850 at all concentrations used blocked the stimulatory effect of PMA on the phosphorylation of PKCδ (Fig. 3B).

The initial activation of PKCδ is responsible for PMA effect on transcriptional activation of NHE2.

It is well established that activation of PKC isozymes by physiological stimuli such as growth factors or nonphysiological agents such as PMA eventually leads to inactivation and downregulation of PKC (32, 45). We therefore, examined whether activation of PKC was responsible for the long-term effects of PMA on the NHE2 expression. C2BBe1 cells transiently transfected with NHE2 promoter-reporter construct were subjected to pulsed PMA treatments for 15 min, 2 h, 4 h, and 16 h. After each time point, PMA supplemented medium was completely removed, and the cells were washed twice; then cells were maintained in serum-reduced medium for the remaining duration of incubation up to 16 h. As shown in Fig. 4, an increase in NHE2 promoter activity was evident as early as 15 min of pulse PMA treatment. Furthermore, 2 h of PMA pulse was as efficient as 16 h of continuous treatment for transcriptional activation of NHE2. Biologically inert PMA, 4α-PMA, showed no stimulatory effect on NHE2 expression (data not shown). Therefore, these data suggest that the initial activation of PKCδ by PMA is sufficient to initiate a cascade of signaling events that might lead to long-term stimulation of NHE2 transcription and protein expression.

Fig. 4.

Early events after PMA exposure mediate transcriptional activation of the NHE2 promoter. C2BBe1 cells were transiently transfected with NHE2 promoter-reporter construct, p-415/+150. Cells were incubated in serum-reduced media for 16 h before PMA treatment for the indicated times. After each time point PMA was washed off, and cells were incubated in serum-reduced media (1% FBS) up to 16 h. Cells were harvested 48 h posttransfection, and luciferase activities were determined in 10 μg of total cell proteins. The results are presented as average of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate (n = 3). *P < 0.05.

Effects of ERK1/2 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathways on PMA-induced stimulation of NHE2 transcriptional activity.

To further delineate the other signaling cascades contributing to the PMA effect on NHE2, we analyzed the role of ERK1/2 MAPK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) pathways on the PMA-induced upregulation of NHE2 promoter activity. Cells were transiently transfected with p-1051/+150, preincubated with MEK-ERK inhibitor (U0126, 50 μM) or PI3-K inhibitor (LY294002, 50 μM) before exposure the PMA. U0126 inhibits phosphorylation of MEK and therefore prevents ERK1/2 activation. Reporter gene analysis revealed complete blockade of the stimulatory effect of PMA on the NHE2 promoter activity in the presence of U0126 (Fig. 5A). In contrast, LY294002 did not alter the stimulatory effect of PMA on NHE2 promoter activity (Fig. 5B). These results indicate that MEK-ERK, but not PI3K signaling cascade, is involved in mediating the stimulatory effects of PMA on NHE2 promoter activity.

Fig. 5.

Effects of ERK1/2 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3-K) pathway inhibitors on the NHE2 promoter activity. C2BBe1 cells were serum starved and treated with ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 (50 μM) (A) or LY294002 (50 μM) (B), a PI3-K inhibitor, for 1 h and subsequently stimulated with PMA (100 nM) for 16 h. Luciferase actives were determined as described in materials and methods. *Activity significantly different from PMA treatment (P < 0.05).

ERK is activated in response to PMA in C2BBe1 cells.

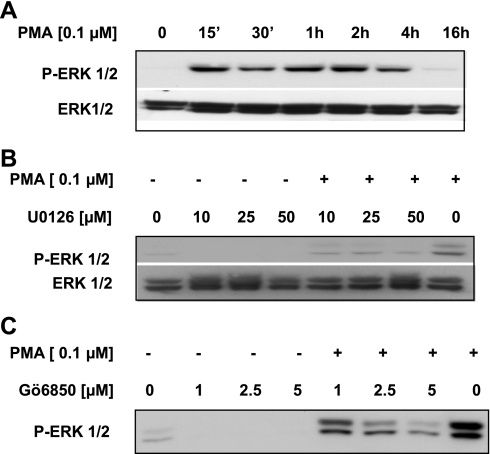

Next we examined the kinetics of ERK1/2 activation in response to PMA. Serum-starved C2BBe1 cells were treated with PMA (100 nM) and harvested at different time points. The status of ERK1/2 phosphorylation was determined by Western blot analysis using phospho-ERK1/2 antibody. As demonstrated in Fig. 6A, activation of ERK1/2 by phosphorylation occurred within 15 min of PMA treatment, persisted for at least 4 h and reduced substantially by 16 h of PMA treatment.

Fig. 6.

ERK1/2 activation in response to PMA in C2BBe1 cells. A: C2BBe1 cells were serum starved and treated with PMA for 15 min to 16 h. TCL were prepared and resolved in SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-phospho-ERK1/2 antibody. A similarly loaded gel was processed and probed with Pan-ERK1/2 antibody as loading control. B and C: after serum starvation and pretreatment (1 h) with different doses of U0126 or Gö6850, respectively, cells were incubated with or without PMA (100 nM) for 1 h. Western blot analyses were performed on TCL using anti-phospho-ERK antibody. The membrane in B was stripped and reprobed with Pan-ERK antibody as loading control.

To further define the early events leading to activation of ERK1/2 in response to PMA, we next examined whether PKC and MEK1/2 signaling pathways were necessary for ERK1/2 phosphorylation. C2BBe1 cells were preincubated with different concentrations of U0126 (10, 25, and 50 μM) or Gö6983 (1, 2.5, and 5 μM) for 1 h. Subsequently, PMA (100 nM) was added, and cells were maintained in the presence of the inhibitors and PMA for additional 1 h before whole cell lysate preparations. Western blot analyses revealed that both the inhibitors were capable of blocking ERK1/2 phosphorylation by PMA in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6, B and C). These data suggested that ERK1/2 might be downstream effectors of PMA signaling pathway.

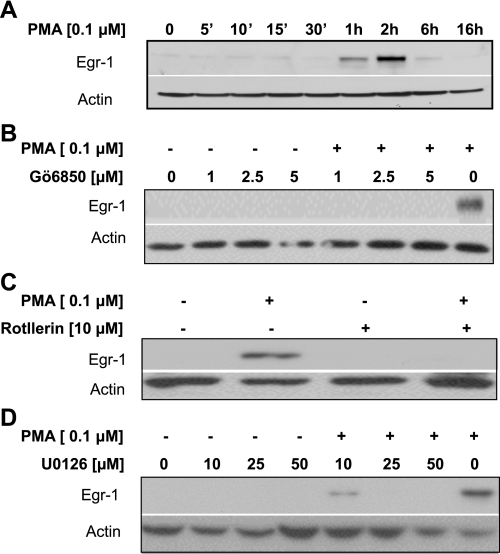

Inhibition of PKCδ and MEK-ERK activation prevent Egr-1 expression in C2BBe1 cells.

PMA stimulates the expression of NHE2 through overexpression of transcription factor Egr-1 and its interaction with the NHE2 promoter (36). In accordance with our previous data, PMA-induced Egr-1 protein expression was transient, peaked between 1–2 h and returned to the basal level by 6 h (Fig. 7A). To assess the correlation between PMA-induced signaling pathways and Egr-1 expression, we performed Western blot analysis. Serum-starved, inhibitor-treated cells were exposed to PMA for 2 h, and the effects of pathway-specific inhibitors on the Egr-1 abundance in the nuclear extracts were examined. Our data demonstrated that all three inhibitors, Gö6850 (5 μM) (Fig. 7B), rottlerin (10 μM) (Fig. 7C), and ERK inhibitor, U0126 (50 μM) (Fig. 7D), inhibited the Egr-1 expression in the PMA-treated C2BBe1 nuclear extracts.

Fig. 7.

Egr-1 expression in response to PMA and pathway-specific inhibitors. A: C2BBe1 cells were serum starved and treated with PMA for 5 min, 10 min, 15 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 6 h, and 16 h. Nuclear proteins were prepared subjected to Western blot analysis using antibody against Egr-1 transcription factor. The membrane was then stripped and reprobed with actin antibody for loading control. In other experiments serum-starved cells were pretreated with PKC inhibitor Gö6850 (1–5 μM) (B), PKCδ-specific inhibitor rottlerin (10 μM) (C), or ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 (10–50 μM) (D) for 1 h. Cells were then stimulated with or without PMA (100 nM) for 1 h. Western blot analyses were performed using anti-Egr-1 antibody as described in materials and methods. Actin was used as loading control.

Inhibition of ERK1/2 activation prevents nuclear accumulation and translocation of Egr-1 by PMA in C2BBe1 cells.

Having shown that ERK1/2 might be the downstream effector molecule for the PMA signaling pathway responsible for activation of NHE2, we examine the effect of ERK1/2 inhibition on the Egr-1 protein expression by immunofluorescence staining. As shown in Fig. 8, top, in untreated C2BBe1 cells Egr-1 was primarily localized in the cytoplasm. PMA treatment promoted nuclear translocation and accumulation of Egr-1 in the nucleus (Fig. 8, middle), and pretreatment with ERK inhibitor U0126 prevented PMA-induced nuclear translocation of Egr-1 (Fig. 8, bottom). Similar to the untreated cells, exposure to U0126 alone did not alter cytoplasmic localization of Egr-1 protein (data not shown). The nuclei were visualized using DAPI staining (blue). To confirm the PMA-induced Egr-1 localization to the nucleus, serial ZY sections (0.5 μM each) were obtained from the level of the nuclei. The reconstructions of the stack of confocal ZY sections are shown on the right of merged panels and confirm the localization of Egr-1 to the nuclei.

Fig. 8.

Effect of ERK1/2 inhibition on the PMA-induced Egr-1 nuclear expression. C2BBe1 cells were grown on glass coverslips to ∼90% confluence, then treated with or without PMA. To assess the effect of U0126, slides were pretreated with U0126 (50 μM, 1 h) before PMA treatments (100 nM, 2 h). The cells were fixed, stained, and visualized under fluorescence microscope as described in materials and methods. In each panel, a horizontal XY-optical section and the corresponding Z stacks (reconstructed serial vertical ZY optical sections of 0.5 μM each) are shown. Egr-1 was visualized with Alexa Fluor 488 (green), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). The positions of vertical cuts are indicated with dashed white lines. In untreated (UT) cells (top) Egr-1 is predominantly located in the cell cytoplasm, whereas confocal images of cells treated with PMA distinctly show that Egr-1 is localized to the nuclei (middle). In contrast, treatment with U0126 before PMA exposure exhibits inhibition of Egr-1 accumulation in the nuclei (bottom). ZY-sections confirm the presence of Egr-1 in the nuclei of PMA-treated cells.

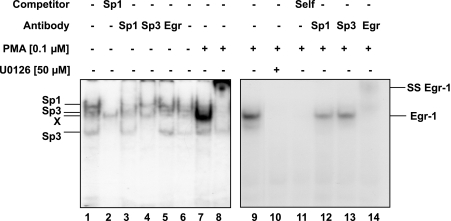

Inhibition of ERK1/2 activation prevents Egr-1 interaction with the NHE2 PMA response element.

To confirm the effects of ERK1/2 activation on the nuclear translocation and accumulation of Egr-1 and its interaction with the NHE2 promoter, we tested the effects of ERK1/2 inhibition on the DNA-binding activity of Egr-1. C2BBe1 cells were pretreated with or without U0126 (50 μM) for 1 h followed by 2 h stimulation with or without PMA (100 nM). Nuclear extracts from these cells were used in gel mobility shift assays in conjunction with [γ-32P]-labeled NHE2 probe that harbors NHE2-PMA response element (bp −339 to −324). In untreated serum-starved nuclear extracts transcription factors Sp1 and Sp3 interact with this probe (Fig. 9, lanes 1 and 6). Supershift assays with Sp1 and Sp3 antibodies eliminated Sp1/Sp3 interactions with the probe, confirming the presence of Sp1 and Sp3 in the DNA-protein complexes formed with nuclear extracts from untreated cells, whereas Egr-1 was absent in these extracts (Fig. 9, lanes 3–5). In contrast, in PMA-treated nuclear extracts Egr-1 was the predominant protein interacting with this probe, which resulted in displacement of Sp1 and Sp3 interactions (Fig. 9, lane 7 and 9). Further studies with U0126-pretreated and PMA-stimulated nuclear extracts demonstrated that the Egr-1-DNA complexes were eliminated by preexposure to U0126 (Fig. 9, lane 10). These data reveal the importance of ERK1/2 signaling for Egr-1 expression and interaction with the NHE2 promoter in response to PMA. Supershift assays with PMA-treated nuclear proteins confirmed the lack of Sp1 and Sp3 in the DNA-protein complex and showed that Egr-1 is the major protein occupying this nucleoprotein complex (Fig. 9, lanes 8 and 12–14). To examine the specificity of DNA-protein interactions, competition assays were performed in the presence of excess (100-fold) unlabeled Sp1 and NHE2-PRE (self) oligonucleotides (Fig. 9, lanes 2 and 11, respectively). Overall, these results demonstrated that PMA-induced ERK1/2 activation is responsible for upregulation of NHE2 transcription by PMA through induction of Egr-1 expression.

Fig. 9.

PMA-induced Egr-1 interacts with NHE2-PRE, and ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 prevents this interaction. 32P-end-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotide containing the NHE2 PRE at nucleotides −339 to −324 was incubated with nuclear proteins (5 μg) from untreated (lanes 1–7) or PMA-treated (100 nM, 2 h) (lanes 8–14) cells for 20 min at room temperature. The reactions were carried out in the absence (lanes 1 and 6) or presence of unlabeled Sp1 and NHE2-PRE (100-fold excess) oligonucleotides (lanes 2 and 11, respectively) or in the presence of specific antibodies (lanes 2–4, 8, and 12–14) as shown on top of the image. ss, supershifted band. DNA-protein complexes were resolved on 5% native gels, dried, and visualized by autoradiography.

DISCUSSION

We have previously shown that exposure of C2BBe1 intestinal epithelial cells to PMA induces the expression of transcription factor Egr-1, resulting in stimulation of the transcriptional activity of the human NHE2 gene. In this study, we investigated the upstream signaling pathways that control Egr-1 induction and stimulation of NHE2 expression in response to PMA. We demonstrated that activation of PKCδ and ERK1/2 signal transduction pathways are the key mechanisms in the PMA-mediated activation of transcription factor Egr-1, which leads to stimulation of NHE2 expression.

Our functional studies using selective PKC chemical inhibitors Gö6976, Gö6983, and Gö6850 implicated PKCδ in mediating the effects of PMA on NHE2 expression. The use of PKCδ-specific siRNA provided unequivocal evidence that activation of PKCδ isozyme is involved in mediating the stimulatory effect of PMA on NHE2 promoter activity. Furthermore, PMA washout studies revealed that early signaling events triggered by PMA exposure were responsible for PMA-induced stimulation of NHE2 transcriptional activity. We showed that a 2-h PMA pulse was as efficient as 16 h of continuous PMA exposure for activation of NHE2 transcriptional activity (Fig. 3). These findings agree with our previous reports, where PMA exposure led to a time-dependent increase (1–6 h) in the endogenous NHE2 mRNA levels (36). These data strongly suggest that the initial phase of PKCδ activation by PMA may be responsible for PMA effect on NHE2 expression.

PKCδ has been shown to play a positive role in mediating mitogenic responses through activation of the MAPK signaling pathway (23, 50). In C2BBe1 cells, PMA triggered a time-dependent activation of ERK1/2 and U0126, a MEK-ERK pathway inhibitor, and blocked the PMA-induced stimulation of NHE2 promoter activity, revealing the critical role of ERK1/2 for transcriptional activation of NHE2. In addition, inhibition of ERK1/2 phosphorylation via PKC and MEK-ERK inhibitors provided evidence that ERK1/2 function as the downstream effector molecules in the PMA-induced signaling hierarchy. These data also suggested that ERK1 and 2 are not direct substrates for PKC. Hence, our findings suggest that PKCδ → →MEK→ERK1/2 pathway and ERK/Egr-1 nexus are involved in the PMA-induced stimulation of NHE2 expression.

A wealth of information is available on the short-term regulation of NHEs, which mostly represents regulation by posttranslational modifications, protein-protein interactions, and membrane trafficking (52). In regards to regulation by signal transduction pathways, activation of PKCα by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli infection resulted in enhanced NHE2 transport activity in Caco-2 colonic cell line (20). Watts et al. 2006 (46), demonstrated that the ERK1/2 signaling pathway is responsible for the inhibition of NHE3 transport activity by short-term aldosterone treatment to medullary thick ascending limb kidney cell line (46), whereas a positive effect of acute aldosterone on NHE1 activity was triggered by activation of ERK1/2 in MDCK and mouse M-1 cells (14, 37). Other studies have shown that epidermal growth factor (EGF)-mediated and fibroblast growth factor-mediated stimulation of NHE3 occurs through activation of PI3-K pathway (11). Recently, the mechanisms mediating the long-term regulation of NHEs have begun to emerge. The human NHE8 promoter activity was shown to be downregulated by chronic EGF stimulation in Caco-2 cells and inhibition of ERK1/2 signaling pathway reversed the inhibitory effect of EGF, suggesting that ERK pathway may play a negative role in regulation of NHE8 by EGF (49). Long-term administration of EGF to rats or exposure of rat and human intestinal epithelial cells to EGF resulted in transcriptional activation of NHE2; however, the signaling mechanisms involved have not been investigated (5, 48). Previously, we demonstrated that PKA-dependent posttranslational modification of transcription factors Sp1 and Sp3 and their reduced DNA-binding activity may be responsible for the repression of NHE3 transcriptional activity by TNF-α and IFN-γ (4). Furthermore, our recent studies showed that PKCα activation by serotonin leads to repression of both transcriptional and functional activity of NHE3 in intestinal epithelial cells (3, 15). The role of PKCδ and ERK1/2 as positive regulators of NHE2 transcriptional activity shown here is quite novel.

Studies in various cell systems have demonstrated that activation of ERK signaling pathway by mitogenic stimuli is often associated with the induction of immediate early genes including Egr-1 (1, 28, 29, 35). Egr-1 plays a critical role in a number of important biological functions including regulation of cell proliferation, angiogenesis, apoptosis, wound healing, and inflammation (13, 30). Egr-1 is rapidly and transiently induced in response to multiple mitogenic signals (18, 39), okadaic acid (8), and inflammatory mediators (19). Our studies demonstrate that ERK activation by PMA is also responsible for NHE2 transactivation by Egr-1. In this regard, chronic metabolic acidosis was reported to increase the NHE1 activity (21). The acid-induced activation of NHE1 activity was associated with increased NHE1 mRNA expression via activation of PKC and possibly subsequent induction of transcription factor activator protein-1 (22). Lucioni et al. (33) demonstrated that chronic metabolic acidosis also enhances NHE2 transcription, protein abundance, and 22Na+-uptake in the ileal and colonic scrapings from rat intestine; however, details of the mechanisms of action have not been established. Reduced pH has been shown to elevate Egr-1 expression in T84 and HCT116 colonic epithelial cell lines (1). Similarly, our unpublished data show that in response to extracellular acidic pH Egr-1 mRNA and protein expression is upregulated in C2BBe1 cells. Therefore, we speculate that acid-induced Egr-1 expression in the intestinal epithelial cells may be responsible for the increased NHE2 expression and activity observed under conditions of cellular acidosis; this, however, remains to be experimentally investigated.

Our immunofluorescence studies revealed that inhibition of ERK activation blocks Egr-1 translocation to the nucleus (Fig. 8). Consistent with these data, in vitro DNA-binding assays displayed that the NHE2 promoter region at bp −339 to −324 binds to Egr-1 in PMA-treated nuclear extracts, whereas Egr-1 binding was absent in PMA-treated nuclear proteins that were preexposed to U0126. Thus it appears that ERK1 and 2 act to integrate the stimulatory effects of the upstream signaling molecules and relay the stimulatory cues to Egr-1, which in turn promotes the transcriptional upregulation of NHE2 in C2BBe1 cells. This signaling cascade conforms well to the results of other studies investigating the signaling cascades involved in Egr-1 activation in various cell systems (2, 9, 17, 24).

In summary, our studies provide the first compelling evidence that, during early events of cellular response to PMA, PKCδ activation may provide the initial signaling cues for the subsequent activation of downstream effector molecules involved in NHE2 stimulation. The Egr-1 induction by PMA (1–2 h) following the activation of PKCδ (5 min) and ERK1/2 (15 min to 4 h) strongly suggests that, after the removal of PMA, sequential activation of the signaling cascades leads to the transactivation of the NHE2 promoter. These observations support the possibility that the initial phase of PMA-induced PKCδ activation is responsible for ERK1/2 phosphorylation. ERK-mediated Egr-1 induction and its subsequent translocation to the nucleus ultimately promote transcriptional activation of the NHE2 by PMA. Our findings of the involvement of PKCδ and MEK-ERK signaling pathways in the upregulation of the NHE2 expression by the mitogenic agent PMA are entirely novel. These findings provide a direct link between activation of intracellular signaling pathways and stimuli-induced cellular readouts such as NHE2 transcriptional activation. The knowledge of participation of PKCδ and ERK1/2 signaling pathway in long-term regulation of NHE2 is important and provides new mechanistic insights into the regulation of this important NHE, which has been implicated in colonocyte Na+ absorption and pH homeostasis.

GRANTS

The studies were supported by the NIDDK grants, R01-DK 33349 (J. Malakooti), P01-DK 67887 (J. Malakooti, P. K. Dudeja), R01-DK 54016 and R01-DK 81858 (P. K. Dudeja).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Krishnamurthy Ramaswamy for critical review of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. Abdel-Latif MM, Windle HJ, Davies A, Volkov Y, Kelleher D. A new mechanism of gastric epithelial injury induced by acid exposure: the role of Egr-1 and ERK signaling pathways. J Cell Biochem 108: 249–260, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Aggeli IK, Beis I, Gaitanaki C. ERKs and JNKs mediate hydrogen peroxide-induced Egr-1 expression and nuclear accumulation in H9c2 cells. Physiol Res 59: 443–454, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Amin MR, Ghannad L, Othman A, Gill RK, Dudeja PK, Ramaswamy K, Malakooti J. Transcriptional regulation of the human Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 by serotonin in intestinal epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 382: 620–625, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amin MR, Malakooti J, Sandoval R, Dudeja PK, Ramaswamy K. IFN-γ and TNF-α regulate the human NHE3 gene expression by modulating the Sp family transcription factors in human intestinal epithelial cell line, C2BBe1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291: C887–C896, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Amin MR, Orenuga T, Tyagi S, Dudeja PK, Ramaswamy K, Malakooti J. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha represses the expression of NHE2 through NF-kappaB activation in intestinal epithelial cell model, C2BBe1. Inflamm Bowel Dis 17: 720–731, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bobulescu IA, Moe OW. Luminal Na(+)/H (+) exchange in the proximal tubule. Pflügers Arch 458: 5–21, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carpenter AC, Alexander JS. Endothelial PKC delta activation attenuates neutrophil transendothelial migration. Inflamm Res 57: 216–229, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chauhan D, Kharbanda SM, Uchiyama H, Sukhatme VP, Kufe DW, Anderson KC. Involvement of serum response element in okadaic acid-induced EGR-1 transcription in human T-cells. Cancer Res 54: 2234–2239, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. De Sousa LP, Brasil BS, Silva BM, Freitas MH, Nogueira SV, Ferreira PC, Kroon EG, Bonjardim CA. Plasminogen/plasmin regulates c-fos and Egr-1 expression via the MEK/ERK pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 329: 237–245, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dempsey EC, Newton AC, Mochly-Rosen D, Fields AP, Reyland ME, Insel PA, Messing RO. Protein kinase C isozymes and the regulation of diverse cell responses. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 279: L429–L438, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Donowitz M, Janecki A, Akhter S, Cavet ME, Sanchez F, Lamprecht G, Zizak M, Kwon WL, Khurana S, Yun CH, Tse CM. Short-term regulation of NHE3 by EGF and protein kinase C but not protein kinase A involves vesicle trafficking in epithelial cells and fibroblasts. Ann NY Acad Sci 915: 30–42, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donowitz M, Li X. Regulatory binding partners and complexes of NHE3. Physiol Rev 87: 825–872, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gashler A, Sukhatme VP. Early growth response protein 1 (Egr-1): prototype of a zinc-finger family of transcription factors. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 50: 191–224, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gekle M, Freudinger R, Mildenberger S, Schenk K, Marschitz I, Schramek H. Rapid activation of Na+/H+-exchange in MDCK cells by aldosterone involves MAP-kinase ERK1/2. Pflügers Arch 441: 781–786, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gill RK, Pant N, Saksena S, Singla A, Nazir TM, Vohwinkel L, Turner JR, Goldstein J, Alrefai WA, Dudeja PK. Function, expression, and characterization of the serotonin transporter in the native human intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294: G254–G262, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Griner EM, Kazanietz MG. Protein kinase C and other diacylglycerol effectors in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 7: 281–294, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Guha M, O'Connell MA, Pawlinski R, Hollis A, McGovern P, Yan SF, Stern D, Mackman N. Lipopolysaccharide activation of the MEK-ERK1/2 pathway in human monocytic cells mediates tissue factor and tumor necrosis factor alpha expression by inducing Elk-1 phosphorylation and Egr-1 expression. Blood 98: 1429–1439, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guillemot L, Levy A, Raymondjean M, Rothhut B. Angiotensin II-induced transcriptional activation of the cyclin D1 gene is mediated by Egr-1 in CHO-AT(1A) cells. J Biol Chem 276: 39394–39403, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gurgui M, Broere R, Kalff JC, van Echten-Deckert G. Dual action of sphingosine 1-phosphate in eliciting proinflammatory responses in primary cultured rat intestinal smooth muscle cells. Cell Signal 22: 1727–1733, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hodges K, Gill R, Ramaswamy K, Dudeja PK, Hecht G. Rapid activation of Na+/H+ exchange by EPEC is PKC mediated. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 291: G959–G968, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Horie S, Moe O, Tejedor A, Alpern RJ. Preincubation in acid medium increases Na/H antiporter activity in cultured renal proximal tubule cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 4742–4745, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Horie S, Moe O, Yamaji Y, Cano A, Miller RT, Alpern RJ. Role of protein kinase C and transcription factor AP-1 in the acid-induced increase in Na/H antiporter activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 5236–5240, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jackson DN, Foster DA. The enigmatic protein kinase Cδ: complex roles in cell proliferation and survival. FASEB J 18: 627–636, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jalagadugula G, Dhanasekaran DN, Rao AK. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) responsive sequence in Galphaq promoter during megakaryocytic differentiation. Regulation by EGR-1 and MAP kinase pathway. Thromb Haemost 100: 821–828, 2008 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jones E, Adcock IM, Ahmed BY, Punchard NA. Modulation of LPS stimulated NF-kappaB mediated Nitric Oxide production by PKCepsilon and JAK2 in RAW macrophages. J Inflamm 4: 23, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kandasamy RA, Yu FH, Harris R, Boucher A, Hanrahan JW, Orlowski J. Plasma membrane Na+/H+ exchanger isoforms (NHE-1, -2, and -3) are differentially responsive to second messenger agonists of the protein kinase A and C pathways. J Biol Chem 270: 29209–29216, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kato A, Romero MF. Regulation of electroneutral NaCl absorption by the small intestine. Annu Rev Physiol 73: 261–281, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kaufmann K, Bach K, Thiel G. The extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases Erk1/Erk2 stimulate expression and biological activity of the transcriptional regulator Egr-1. Biol Chem 382: 1077–1081, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Keeton AB, Bortoff KD, Bennett WL, Franklin JL, Venable DY, Messina JL. Insulin-regulated expression of Egr-1 and Krox20: dependence on ERK1/2 and interaction with p38 and PI3-kinase pathways. Endocrinology 144: 5402–5410, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Khachigian LM, Collins T. Early growth response factor 1: a pleiotropic mediator of inducible gene expression. J Mol Med 76: 613–616, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kiela PR, Xu H, Ghishan FK. Apical NA+/H+ exchangers in the mammalian gastrointestinal tract. J Physiol Pharmacol 57, Suppl 7: 51–79, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Leontieva OV, Black JD. Identification of two distinct pathways of protein kinase Calpha down-regulation in intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem 279: 5788–5801, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lucioni A, Womack C, Musch MW, Rocha FL, Bookstein C, Chang EB. Metabolic acidosis in rats increases intestinal NHE2 and NHE3 expression and function. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 283: G51–G56, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Malakooti J, Dahdal RY, Schmidt L, Layden TJ, Dudeja PK, Ramaswamy K. Molecular cloning, tissue distribution, and functional expression of the human Na+/H+ exchanger NHE2. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 277: G383–G390, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Malakooti J, Sandoval R, Amin MR, Clark J, Dudeja PK, Ramaswamy K. Transcriptional stimulation of the human NHE3 promoter activity by PMA: PKC independence and involvement of the transcription factor EGR-1. Biochem J 396: 327–336, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Malakooti J, Sandoval R, Memark VC, Dudeja PK, Ramaswamy K. Zinc finger transcription factor Egr-1 is involved in stimulation of NHE2 gene expression by phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 289: G653–G663, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Markos F, Healy V, Harvey BJ. Aldosterone rapidly activates Na+/H+ exchange in M-1 cortical collecting duct cells via a PKC-MAPK pathway. Nephron Physiol 99: 1–9, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Martiny-Baron G, Kazanietz MG, Mischak H, Blumberg PM, Kochs G, Hug H, Marme D, Schachtele C. Selective inhibition of protein kinase C isozymes by the indolocarbazole Go 6976. J Biol Chem 268: 9194–9197, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mayer SI, Willars GB, Nishida E, Thiel G. Elk-1, CREB, and MKP-1 regulate Egr-1 expression in gonadotropin-releasing hormone stimulated gonadotrophs. J Cell Biochem 105: 1267–1278, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nath SK, Kambadur R, Yun CH, Donowitz M, Tse CM. NHE2 contains subdomains in the COOH terminus for growth factor and protein kinase regulation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 276: C873–C882, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Newton AC. Protein kinase C: structural and spatial regulation by phosphorylation, cofactors, and macromolecular interactions. Chem Rev 101: 2353–2364, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Oliva JL, Griner EM, Kazanietz MG. PKC isozymes and diacylglycerol-regulated proteins as effectors of growth factor receptors. Growth Factors 23: 245–252, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Pearse I, Zhu YX, Murray EJ, Dudeja PK, Ramaswamy K, Malakooti J. Sp1 and Sp3 control constitutive expression of the human NHE2 promoter by interactions with the proximal promoter and the transcription initiation site. Biochem J 407: 101–111, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Peterson MD, Mooseker MS. Characterization of the enterocyte-like brush border cytoskeleton of the C2BBe clones of the human intestinal cell line, Caco-2. J Cell Sci 102: 581–600, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rodriguez-Pena A, Rozengurt E. Disappearance of Ca2+-sensitive, phospholipid-dependent protein kinase activity in phorbol ester-treated 3T3 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 120: 1053–1059, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Watts BA, 3rd, George T, Good DW. Aldosterone inhibits apical NHE3 and HCO3− absorption via a nongenomic ERK-dependent pathway in medullary thick ascending limb. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 291: F1005–F1013, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xu H, Chen R, Ghishan FK. Subcloning, localization, and expression of the rat intestinal sodium-hydrogen exchanger isoform 8. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 289: G36–G41, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Xu H, Collins JF, Bai L, Kiela PR, Lynch RM, Ghishan FK. Epidermal growth factor regulation of rat NHE2 gene expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 281: C504–C513, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Xu H, Zhang B, Li J, Chen H, Tooley J, Ghishan FK. Epidermal growth factor inhibits intestinal NHE8 expression via reducing its basal transcription. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 299: C51–C57, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yamaguchi K, Ogita K, Nakamura S, Nishizuka Y. The protein kinase C isoforms leading to MAP-kinase activation in CHO cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 210: 639–647, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yun CH, Tse CM, Nath SK, Levine SA, Brant SR, Donowitz M. Mammalian Na+/H+ exchanger gene family: structure and function studies. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 269: G1–G11, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zachos NCTM, Donowitz M. Molecular physiology of intestinal Na+/H+ exchange. Annu Rev 67: 411–443, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]