Abstract

Transcription factors play diverse roles during embryonic development, combinatorially controlling multiple cellular states in a spatially and temporally defined manner. Resolving the dynamic transcriptional profiles that underlie these patterning processes is essential for understanding embryogenesis at the molecular level. Here we show how temporal, tissue-specific changes in embryonic transcription factor function can be discerned by integrating caged morpholino oligonucleotides (cMOs) with photoactivatable fluorophores, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), and microarray technologies. As a proof of principle, we have dynamically profiled No tail-a (Ntla)-dependent genes at different stages of axial mesoderm development in zebrafish, discovering discrete sets of transcripts that are coincident with either notochord cell fate commitment or differentiation. Our studies reveal new regulators of notochord development and the sequential activation of distinct transcriptomes within a cell lineage by a single transcriptional factor, demonstrating how optically controlled chemical tools can dissect developmental processes with spatiotemporal precision.

During embryonic development, cell fate and function are regulated by an ensemble of transcription factors. Each factor typically has pleiotropic roles, acting in multiple tissues and developmental stages, and deciphering its downstream effectors for specific embryological processes can be difficult to achieve with conventional genetic methods. Synthetic reagents can help bridge this technological gap, as they can modulate gene function with spatiotemporal dynamics that rival endogenous patterning mechanisms1. Toward this goal, we recently developed cMO antisense oligonucleotides that can be photoactivated in optically transparent embryos within seconds and with cellular resolution2,3. These reagents consist of a standard 25-base RNA-targeting MO, a complementary inhibitor, and a light-sensitive linker that tethers the two oligomers (Fig. 1a). In their caged state, the synthetic oligonucleotides adopt a hairpin structure that abrogates RNA binding, while linker cleavage by ultraviolet (UV) or two-photon infrared light liberates the targeting MO and allows it to inhibit RNA splicing or translation. A broad range of developmental transcripts can be targeted by cMOs, and we have employed these tools to conditionally regulate several zebrafish genes, including no tail-a (ntla), floating head (flh), endothelial specific-related protein (etsrp/etv2), and heart of glass (heg) 2,3. Other MO caging methods have been described 4–6, providing alternative methods for photo-control of in vivo gene function.

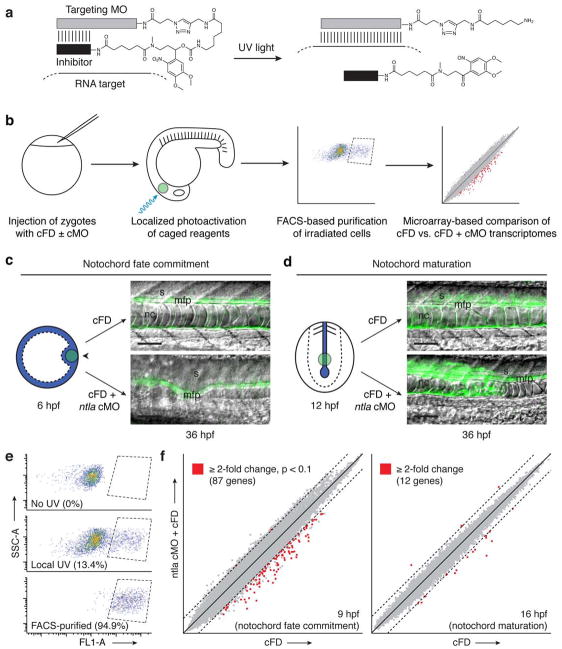

Figure 1. Notochord development is promoted by distinct Ntla transcriptomes.

a, Schematic representation of a hairpin cMO and its uncaging by UV light. b, Strategy for dynamic transcriptional profiling by integrating cMOs, photoactivatable fluorophores, FACS, and oligonucleotide microarrays. c, Depiction of a zebrafish embryo injected with either cFD or a ntla cMO/cFO mixture and then UV-irradiated within the shield domain (black arrowhead) at 6 hpf (animal pole view). Ntla-expressing cells are blue, and the irradiated region is depicted by the green circle. Trunk regions of the resulting embryos at 36 hpf are shown as overlays of differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence micrographs; notochord (nc), medial floor plate (mfp) cells, and somites (s) are labeled. Micrograph orientations: lateral view and anterior left. Scale bars: 100 μm. d, Analogous depiction of an embryo similarly injected and then UV-irradiated within the posterior chordamesoderm at 12 hpf (posterior dorsal view). e, Representative log-scale FACS plots of cells obtained from 9-hpf embryos that were previously injected with cFD and either cultured in the dark or UV-irradiated as depicted in c. Fluorescence intensity (FL1-A; Ex: 488 nm, Em: 530 nm) and Side Scatter Area (SSC-A) measurements are shown; the percentage of total cells within the sorting gate (dashed lines) for each condition is indicated in parentheses. f, Microarray-based comparison of transcripts expressed within the axial mesoderm of cFD- and ntla cMO/cFD-injected embryos during gastrulation (9 hpf) or somitogenesis (16 hpf), developmental stages coincident with notochord fate commitment and maturation, respectively. Dashed lines indicate two-fold thresholds.

We observed previously that ntla cMO photoactivation at different embryonic stages induced distinct mesodermal phenotypes2, suggesting that ntla, a zebrafish ortholog of the T-box transcription factor Brachyury7–9, has temporally separable roles in mesoderm development. Global loss of Ntla during gastrulation resulted in notochord and posterior mesoderm ablation, ectopic medial floor plate cells, and somite patterning defects2, recapitulating the developmental defects found in ntla mutants8–11. Photoactivation of the ntla cMO during somitogenesis, however, produced embryos with notochord cells that failed to vacuolate properly2. These observations indicate that ntla is required for both notochord cell fate determination and notochord differentiation, suggesting that Ntla either regulates a collection of genes with stage-specific functions or sequentially activates distinct transcriptional programs during axial mesoderm patterning. Since the notochord arises from ntla-expressing cells that originate in the embryonic shield and subsequently populate the chordamesoderm12, dynamically profiling the Ntla-dependent transcriptome in the axial mesoderm could divulge the molecular mechanisms that control notochord development and provide general insights into the extent to which transcription factor function can change within a single cell lineage.

Conventional methods for interrogating embryonic gene function have typically utilized genetic approaches with limited spatiotemporal resolution. In the case of Ntla, previous genome-wide surveys of its transcriptional targets have been based on whole-embryo comparisons of wildtype zebrafish with ntla mutants or constitutive morphants (embryos injected with non-conditional MOs)13,14. To minimize secondary effects of Ntla loss of function, these analyses focused on early stages of ntla expression, during which the majority of ntla-expressing cells are not yet axially restricted7. These previous investigations also replied upon whole-embryo analyses, leading to the dilution of Ntla-dependent transcripts by contributions from the entire embryo and reducing detection sensitivity. Perhaps as a result, most of the Ntla-dependent genes identified in these studies are not selectively transcribed in the axial mesoderm and therefore are unlikely to specifically contribute to notochord formation or function. A recent chromatin immunoprecipitation-microarray (ChIP-chip) study of zebrafish gastrula similarly yielded candidate Ntla targets that are primarily expressed outside of the axial mesoderm15. This latter investigation, however, identified possible Ntla-binding sites upstream of the flh locus, consistent with the inability of flh mutants to form the notochord16.

To overcome these technical limitations and better understand how Ntla regulates notochord development, we devised a general strategy for dynamically profiling embryonic transcriptomes using cMOs. In this approach, zebrafish zygotes are co-injected with a transcription factor-targeting cMO and a photoactivatable fluorophore such as caged fluorescein-conjugated dextran (cFD). Irradiating specific tissues at later developmental stages would simultaneously block further expression of the targeted transcription factor and uncage fluorescein in these cells, allowing them to be isolated by FACS and then transcriptionally profiled with oligonucleotide microarrays (Fig. 1b). Through this methodology, we hoped to dynamically profile the Ntla-dependent transcriptome during axial mesoderm development, thereby revealing the mechanisms by which an individual transcription factor can regulate multiple developmental processes. Our studies identify several new Ntla-dependent genes that are transcribed within the axial mesoderm, some of which are essential for notochord development. Moreover, we observe that Ntla sequentially induces distinct, non-overlapping transcriptomes as these mesodermal progenitors become committed to notochord fates and subsequently differentiate, revealing a remarkable degree of plasticity in transcription factor function.

RESULTS

Ntla promotes notochord fate commitment and maturation

To realize this cMO-based strategy, we first sought to demonstrate that we could induce distinct mesodermal phenotypes in a cell-autonomous manner by photoactivating the ntla cMO within the embryonic shield during gastrulation or the chordamesoderm during somitogenesis. We injected zebrafish zygotes with a ntla cMO/cFD mixture and UV irradiated a 100 μm-diameter region of the shield at 6 hours post fertilization (hpf) (Fig. 1c). By 36 hpf, the irradiated, green-fluorescent cells contributed to the medial floor plate rather than the notochord, consistent with earlier proposals that Ntla acts as a transcriptional switch between these two cell fates10,11. In contrast, when we photoactivated the ntla cMO within a similarly sized region of the posterior chordamesoderm at 12 hpf, the targeted cells acquired a notochord fate but failed to organize and vacuolate properly (Fig. 1d). Thus, ntla is required cell autonomously within mesodermal progenitors to promote varied aspects of notochord development.

Spatiotemporal resolution of Ntla transcriptomes

We next used these caged reagents to investigate the molecular mechanisms that mediate these patterning processes. We injected zebrafish embryos with the ntla cMO/cFD mixture and locally irradiated them as before, fixed them at different time points, and then assessed Ntla and uncaged fluorescein levels by whole-mount immunostaining (Supplementary Results, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Through these studies we determined that ntla cMO photoactivation within axial mesoderm progenitors at 6 or 12 hpf resulted in Ntla protein depletion within 2 or 3 hours, respectively, establishing suitable time points for assessing Ntla-dependent transcripts for each developmental stage. Another set of embryos was therefore injected with the ntla cMO/cFD mixture and either irradiated within the shield at 6 hpf and dissociated into single cells at 9 hpf or irradiated within the posterior chordamesoderm at 12 hpf and dissociated at 16 hpf. For each experimental condition we obtained approximately 8,000 FACS-purified cells from 25 irradiated embryos (Fig. 1e), from which we could isolate sufficient amounts of mRNA for microarray-based profiling. Embryos injected with cFD alone and subjected to identical irradiation, dissociation, and FACS conditions were used to provide comparison controls.

By analyzing these transcripts with zebrafish oligonucleotide microarrays, we discovered 87 genes that were downregulated by at least two-fold at 9 hpf upon ntla cMO activation at 6 hpf (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Table 1) and a completely non-overlapping set of 12 genes that were similarly affected at 16 hpf after ntla silencing at 12 hpf (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Table 2). Our results included 17 Ntla-dependent genes reported in the previous genome-wide surveys13–15 (Supplementary Table 3), but in contrast to these studies, 66% of the 64 candidate genes with known expression patterns (either previously reported or established in this study) are transcribed in the axial mesoderm (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). Nearly all of the remaining genes are either transcribed in the posterior mesoderm (12%), another ntla-expressing region in the zebrafish embryo, or in the adaxial/paraxial mesoderm (20%), the latter likely reflecting the transient activity of ntla in adaxial muscle progenitor cells during gastrulation17.

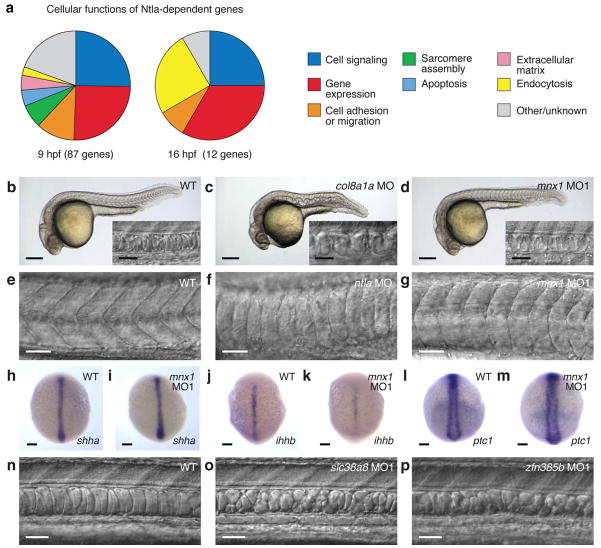

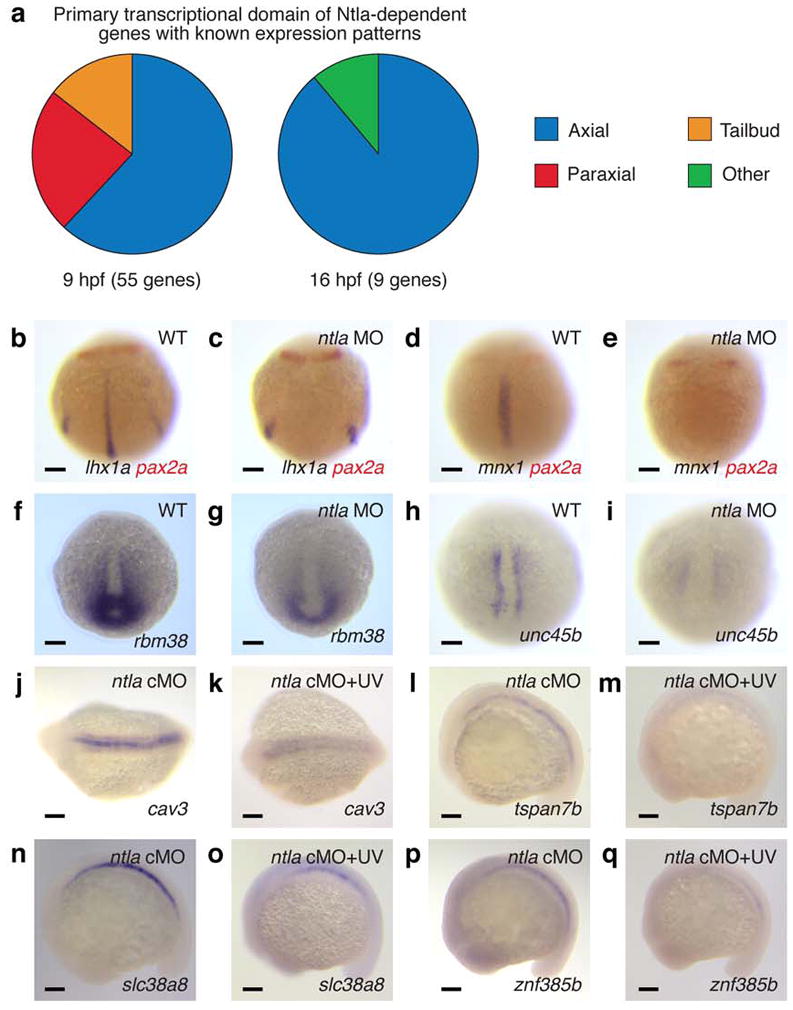

Figure 2. Embryonic expression of Ntla-dependent genes.

a, Tissue localization of Ntla-dependent genes that have known expression patterns and are transcribed during gastrulation (9 hpf) or somitogenesis (16 hpf). b-i, Confirmation of selected microarray hits by in situ hybridization. 10-hpf wildtype and ntla MO-injected embryos stained for candidate Ntla targets expressed during gastrulation are shown, with co-labeling of pax2a transcripts to determine embryo orientation if necessary. j-q, Analogous studies of candidate Ntla targets expressed during somitogenesis. 16-hpf ntla cMO-injected embryos that were either cultured in the dark or globally UV irradiated at 12 hpf are shown. Embryo orientations: b-e and h-i, dorsal view and anterior up; f-g, dorsal posterior view and dorsal up; j-k, dorsal view and anterior left; l-q, lateral view and anterior left. Scale bars: 100 μm.

To confirm that the genes identified in our microarray studies are transcribed in a Ntla-dependent manner, we evaluated the expression patterns of selected transcripts by whole-mount in situ hybridization. Putative Ntla-regulated genes associated with gastrulation were examined in 10-hpf wildtype embryos and conventional ntla morphants (Fig. 2, b-i, and Supplementary Fig. 3), while candidate genes expressed during somitogenesis were assessed using 16-hpf embryos that were previously injected with the ntla cMO and then either cultured in the dark or globally UV-irradiated at 12 hpf (Fig. 2, j-q, and Supplementary Fig. 4). In total, we analyzed 33 of the 99 genes from our candidate lists, and 32 transcripts proved to be expressed in a Ntla-dependent manner. Several genes such as LIM homeobox 1a (lhx1a) and caveolin 3 (cav3) are transcribed in multiple mesodermal tissues but only require Ntla for their expression within axial domains (Fig. 2, b-c and j-k, Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4, and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). We also note that ntla itself and frizzled-related protein (frzb) were transcriptionally upregulated upon ntla cMO photoactivation at 12 hpf (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 5). Since Ntla/Brachyury is not known to have any repressor activity18 and previous studies have suggested that Ntla promotes its own transcription in axial tissues9, we believe that the former effect is due to MO-induced mRNA stabilization, as has been observed in other studies19,20. Genetic interactions between ntla and frzb have not been reported previously, but our microarray data confirms earlier reports that Ntla/Brachyury functions primarily as a transcriptional activator21. Ntla is therefore likely to regulate frzb expression indirectly, although we cannot rule out the possibility of direct repressor activity in this case. Taken together, these results demonstrate that our cMO-based strategy can resolve changes in transcription factor function with spatiotemporal precision and accuracy.

Functional analyses of Ntla-dependent genes

Consistent with ntla acting as a master regulator of notochord development, these downstream effectors are functionally diverse and include developmental signaling proteins, transcription factors, regulators of cell adhesion and migration, and extracellular matrix components (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Tables 6 and 7). Loss-of-function studies have been reported for 13 of the 34 Ntla-dependent genes transcribed in the axial mesoderm during gastrulation (Supplementary Table 8), and we used conventional MOs to silence 6 additional genes of diverse function: hippocalcin-like 4 (hpcal4), inositol polyphosphate phosphatase 5b (inpp5b), snail2 (snai2), lhx1a, transforming acidic coiled coil 2 (tacc2), and motor neuron and pancreas homeobox 1 (mnx1). Surprisingly, only loss of two genes, collagen type VIII alpha 1a (col8a1a) and mnx1, resulted in notochord defects by 1 day post fertilization (dpf) (Supplementary Table 8). As has been previously observed22,23, loss of col8a1a function caused the notochord to undulate, consistent with a role for the extracellular matrix in maintaining notochord integrity (Fig. 3, b-c). Notochord cells in mnx1 morphants appeared to form normally (Fig. 3, b and d), yet the somites were mispatterned in a manner that shared some similarities with ntla morphants (Fig. 3, e-g, and Supplementary Fig. 5). The other 17 mutants or morphants either failed to complete gastrulation or had notochords with wildtype-like morphology (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 8), the latter possibly reflecting functional redundancies among Ntla-regulated genes at this developmental stage. Indeed, the clear loss-of-function phenotypes associated with mnx1 may reflect the ability of transcription factors to broadly impact signaling processes.

Figure 3. Embryonic function of Ntla-dependent genes.

a, Cellular functions of Ntla-dependent genes that are transcribed during gastrulation (9 hpf) or somitogenesis (16 hpf). b-d, Brightfield and DIC (inset) micrographs depicting notochord phenotypes observed in wildtype embryos or those injected with MOs targeting col8a1a or mnx1 at 1 dpf. e-g, Somite patterning in wildtype embryos or those injected with MOs targeting ntla or mnx1 at 1 dpf. h-m, Expression levels of shha, ihhb, and ptc1 in wildtype embryos and mnx1 morphants at 10 hpf. n-p, Comparison of notochord structures in wildtype embryos and those injected with MOs targeting slc38a8 or znf385b. 1.5-dpf embryos are shown. Embryo orientations: b-g and n-p, lateral view and anterior left; h-m, dorsal view and anterior up. Scale bars: b-d, whole-embryo micrograph, 200 μm; b-d, inset, e-g, and n-p, 50 μm; h-m, 100 μm.

Intrigued by the somite defects in mnx1 morphants, we further investigated how this axially expressed transcription factor might promote adaxial and paraxial mesoderm development. Since Hedgehog (Hh) signaling is a primary mechanism by which the notochord regulates somite patterning24, we examined the effects of mnx1 knockdown on the axial expression of Hh ligands [sonic hedgehog-a (shha) and indian hedgehog-b (ihhb)] and the adaxial expression of the Hh target gene ptc1 (Fig. 3, h-m). Although ihhb expression was somewhat reduced in mnx1 morphants in comparison to wildtype embryos, none of the other transcripts were significantly affected. The somite defects in ntla and mnx1 morphants are also morphologically distinct from those caused by the Hh signaling inhibitor cyclopamine25 (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 7). These observations suggest that in addition to Hh ligands, the axial mesoderm produces a non-cell-autonomous signal that is required for muscle morphogenesis and expressed in an mnx1-dependent manner.

Silencing of Ntla-regulated transcripts associated with notochord maturation was much more likely to produce developmental defects, perhaps reflecting the limited number of these genes. Conventional MOs targeting cav3, polymerase 1 and transcript release factor b (ptrfb), solute carrier family 38 member a8 (slc38a8), or zinc finger protein 385b (znf385b) each induced notochords with vacuolization and patterning defects (Fig. 3, n-p, Supplementary Fig. 8, and Supplementary Table 9). These results are consistent with the previously reported roles of ptrfb, cav3, and the cav3 homolog caveolin 1 (cav1) in caveolar endocytosis and notochord development26–28. It has also been proposed that the transport of neutral amino acids by slc38 family members controls intracellular osmolyte balance and therefore cell volume29. Collectively, our findings support a model in which Ntla plays a primary role in notochord maturation by promoting the expression of genes that regulate vacuole formation and size.

Temporal dissection of Ntla function

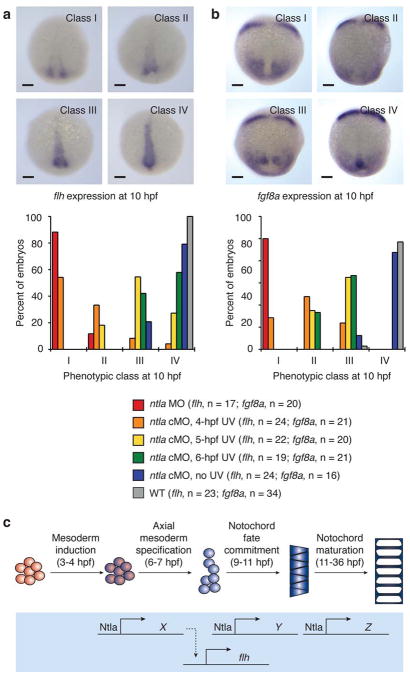

Given the established role of flh in notochord development16, it is noteworthy that the homeobox transcription factor was not identified as a Ntla-dependent gene in our cMO-based microarray analyses of 9-hpf embryos. While the initial phase of flh expression is Ntla-independent, flh transcription within the axial mesoderm is prematurely lost in ntla mutants during gastrulation and somitogenesis16. Whether Ntla directly or indirectly regulates flh expression at these later developmental stages remains unclear, as previous studies have been unable to discern how ntla/flh interactions change over time. One possibility is that Ntla indirectly promotes axial flh expression by establishing a cellular state that is competent for sustained flh transcription. Consistent with this idea, the remaining flh-expressing cells in ntla mutants are laterally displaced16, and time-lapse imaging studies have confirmed that loss of ntla function disrupts the convergence of cells at the midline30. Phenotypic comparisons of ntla, flh, and ntla/flh mutants also indicate that ntla has an early function required for the formation of flh-responsive notochord precursors, with these cells becoming re-specified into flh-insensitive medial floor plate precursors in ntla mutants10. These observations suggest that Ntla-dependent convergence and/or cell specification is required to generate a population of notochord progenitor cells that maintain flh expression and respond to this homeobox gene, mechanisms that do not require direct Ntla/flh interactions. On the other hand, the identification of Ntla-binding sites upstream of flh by ChIP-chip analysis has raised the possibility that Ntla directly regulates flh expression during and after gastrulation15.

To test these models and confirm our microarray results, we used the ntla cMO to globally inactivate ntla expression at 6 hpf and visualized flh transcription at 10, 12, and 20 hpf by whole-mount in situ hybridization (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 9). Consistent with our microarray data, ntla silencing at 6 hpf did not ablate flh expression within the chordamesoderm or tailbud at later time points. We subsequently examined the temporal relationship between Ntla function and flh expression by photoactivating the ntla cMO at earlier time points, using wildtype embryos, conventional ntla morphants, and ntla cMO-injected, non-irradiated embryos as comparison controls (Fig. 4a). Embryos injected with the ntla cMO and UV irradiated at 4 hpf, the stage at which ntla is first transcribed7, were phenotypically similar to conventional ntla morphants and lacked axial flh expression at 10 hpf; photoactivation of the ntla cMO at 5 hpf caused a partial loss of flh transcripts in bud-stage embryos. These results indicate that contemporaneous Ntla expression is not required for flh transcription, and since Ntla protein is largely depleted in the axial mesoderm within two hours of ntla cMO photoactivation (Supplementary Fig. 1), a direct role for Ntla in flh expression appears unlikely. In addition, we found that the flh-expressing cells remaining in conventional or conditional ntla morphants were laterally displaced, with the degree of convergence correlating with the extent of mesodermal flh expression. These findings suggest that Ntla acts early to promote convergence during gastrulation and that these cellular movements are an integral step toward establishing notochord progenitors with sustained axial flh expression.

Figure 4. Temporal dynamics of Ntla-dependent mesoderm development.

a, Expression of flh at 10 hpf in wildtype embryos, conventional ntla morphants, and embryos injected with the ntla cMO and irradiated globally at either 4, 5, or 6 hpf. Micrographs depicting four phenotypic classes of flh expression and the phenotypic distributions associated with each experimental condition are shown. b, Expression of fgf8a at 10 hpf in wildtype embryos, conventional ntla morphants, and embryos treated in analogous manner. Micrographs depicting four phenotypic classes of fgf8a expression and the phenotypic distributions associated with each experimental condition are shown. c, A model for Ntla-dependent patterning of the axial mesoderm. Approximate times for patterning events within the trunk mesoderm, as suggested by ntla cMO phenotypes, are indicated in parentheses. Embryo orientations: dorsal view and anterior up. Scale bars: 100 μm.

To examine this model further, we studied the temporal relationship between Ntla function and the expression of fgf8a, another gene that is axially transcribed in a Ntla-dependent manner31 but was not scored as a hit in our microarray analyses. We injected embryos with the ntla cMO, UV irradiated them at 4, 5, and 6 hpf, and visualized fgf8a expression in 10-hpf embryos by in situ hybridization (Fig. 4b). As before, wildtype embryos, those injected with a conventional ntla MO, and those injected with the ntla cMO but not irradiated were examined in parallel as a comparison controls. Similar to our results with flh, converging fgf8a-expressing cells were laterally displaced upon loss of Ntla function, failing to reach the midline in any of the irradiated ntla cMO-injected embryos. In conventional ntla morphants and ntla cMO-injected embryos irradiated at 4 hpf, the converging cells also exhibited significantly reduced fgf8a transcript levels, while expression of this growth factor was largely restored when the ntla cMO was activated at later time points. Collectively these results provide additional evidence that Ntla promotes the axial coalescence and/or specification of mesodermal progenitors, with cells destined to express fgf8a within the tailbud perhaps arriving from more lateral origins than those fated to express flh in the axial and posterior mesoderm. In both cases, Ntla-regulated cell movement and cell identity are sufficient to explain the observed Ntla-dependent gene expression, and our ability to temporally uncouple Ntla expression from flh and fgf8a transcription argues against a more direct mechanism of action.

DISCUSSION

Although Ntla/Brachyury has been known as a master regulator of notochord development for decades8,9,32,33, the mechanisms by which this T-box transcription factor regulates axial mesoderm patterning have remained elusive. By integrating ntla cMOs, photoactivatable fluorophores, FACS, and microarray analyses, we have specifically probed the Ntla-dependent transcriptome in axial tissues and at distinct developmental stages, revealing several genes associated with notochord fate commitment and maturation. In comparison to previous genome-wide surveys for Ntla-dependent genes13,14, this approach has yielded approximately eight times as many targets, the majority of which are expressed within the presumptive notochord. A number of these genes are transcribed in a Ntla-independent manner in non-axial tissues and therefore would be difficult to discover through conventional, whole-embryo analyses.

In addition to providing a more comprehensive view of the Ntla-dependent transcriptome during axial mesoderm development, our studies have identified novel regulators of notochord patterning and function. Our findings reveal that the transcription factor mnx1 is required for a non-cell autonomous, axially produced signal that regulates somitogenesis. Since adaxial Hh pathway activity is not reduced in mnx1 morphants and the muscle defects in these embryos are distinct from those observed in zebrafish treated with the Hh signaling antagonist cyclopamine, this signal likely constitutes a novel, Hh pathway-independent process. Our studies also demonstrate the Ntla-induced expression of several factors that are required for notochord vacuolization, including the solute carrier family member slc38a8, the zinc finger transcription factor znf385b, and the caveolar proteins cav3 and ptrfb. This critical facet of Ntla-dependent notochord development has eluded previous investigations, which were limited to early aspects of Ntla function.

Using our cMO-based methodology, we observe that the Ntla-dependent transcriptomes associated with notochord fate commitment and maturation are non-overlapping, revealing a surprising degree of transcription factor plasticity during the differentiation of a single cell lineage. Our time-course experiments further demonstrate that Ntla expression is not required contemporaneously for the transcription of flh or fgf8a. Rather, Ntla appears to act prior to and during the onset of epiboly to promote the axial convergence and/or specification of notochord progenitors, which are then competent for sustained flh transcription. Analogous Ntla-dependent processes also likely contribute to the formation of axial cells within the developing tailbud that express flh and fgf8a throughout somitogenesis. The rapid depletion of Ntla protein upon ntla cMO photoactivation suggests that that these genes are not direct Ntla targets, and our findings are more consistent with earlier observations that the initiation of flh expression proceeds normally in ntla mutants16 and that flh-expressing cells are laterally displaced in zebrafish gastrula lacking ntla function16,34 (see also Fig. 4a). While we cannot rule out the possibility that both flh and fgf8a have high-affinity Ntla-binding sites in their cis-regulatory elements, allowing them to respond to significantly lower Ntla concentrations than other Ntla-dependent genes, this scenario seems unlikely since ChIP-chip analyses have identified potential Ntla-binding sites upstream of flh but not fgf8a15.

Overall, the results obtained with our cMO-based approach are consistent with a model in which ntla sequentially promotes multiple cellular states during notochord development (Fig. 4c). Close to the onset of gastrulation, Ntla induces the convergence of mesodermal cells and the specification of axial populations that are competent for flh and/or fgf8a expression at later stages. The T-box transcription factor is subsequently required for the commitment of these chordamesodermal progenitors to a notochord cell fate during gastrulation and finally for the maturation of notochord cells into the fully vacuolated tissue. Each step within this cell differentiation program is associated with a unique ensemble of Ntla-regulated genes, and in principle this model could be further refined to include a continuum of Ntla-dependent transcriptomes throughout notochord development.

We anticipate that this cMO-based approach can be used to investigate other signaling molecules in optically transparent organisms, revealing spatiotemporal differences in gene function. While our studies targeted 100 μm-diameter regions within zebrafish embryos, more restricted cell populations could be examined using higher magnification objectives, micromirror devices, and/or laser light sources. More generally, our findings illustrate how synthetic chemical probes can be combined with other technologies to open new windows into the dynamic mechanisms that regulate organismal biology. In the case of embryonic development, dramatic morphological changes can occur within minutes or hours and with single-cell resolution, yet genetic perturbations typically lack the conditionality required to ascertain gene function with comparable spatiotemporal precision. In comparison, synthetic reagents can transcend Nature’s molecular architecture, and the judicious application of chemical approaches to developmental model systems may illuminate patterning mechanisms that have resisted discovery by conventional genetic methods.

METHODS

Procedures for cFD synthesis, anti-Ntla antibody generation, microscopy, and cyclopamine treatments are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Zebrafish aquaculture and husbandry

Wildtype AB zebrafish embryos were obtained by natural matings and cultured at 28.5 °C according to standard procedures35. All zebrafish experiments were approved by the Stanford University Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care.

Morpholinos and embryo injections

MOs were obtained from Gene-Tools, LLC, and the ntla cMO was synthesized as previously described3. MO and ntla cMO solutions containing 0.1% (w/v) phenol red, 100 mM KCl, and 0.05% (w/v) cFD were prepared and microinjected into zebrafish zygotes (1–3 nL/embryo) according to standard procedures36. MO and cMO sequences, doses, and functional validation methods are summarized in Supplementary Table 10. Phenotype statistics for each micrograph are provided in Supplementary Table 11.

ntla cMO photoactivation

Activation of the ntla cMO with 360-nm light was performed as previously described2,3. For local irradiation, a grid was superimposed onto the imaged embryo using Metamorph software and the UV beam was targeted to the center of the shield in 6-hpf embryos or the chordamesoderm 125 μm anterior to the center of Kupffer’s vesicle in 12-hpf embryos.

Whole-mount immunostaining

Embryos were immunostained with affinity-purified rabbit anti-Ntla polyclonal antibody (1:100 dilution) and mouse monoclonal anti-fluorescein antibody (1:200 dilution; Roche, 1426320) according to published procedures2.

FACS-based purification of irradiated cells

Embryos at the appropriate developmental stage were dechorinated, transferred to calcium-free Ringer’s solution (100 μL for 25–30 embryos; 116 mM NaCl, 2.6 mM KCl, 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.0), dissociated with a 200-μL pipette tip, and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. The suspension was transferred to a 1.2-mL solution of 1X PBS containing trypsin (0.25%, Gibco, 15090-046) and 1 mM EDTA, incubated for 15 min at 28.5 °C with further pipetting every 5 min. For 16-hpf embryos, the trypsin solution was supplemented with collagenase P (30 μg, Roche). Enzymatic processing was quenched with stop solution (200 μL;1X PBS containing 30% (v/v) calf serum and 6 mM CaCl2), and cells were collected by centrifugation (400 x g, 5 min, 4 °C). After aspirating the supernatant, cells were resuspended in a chilled solution of DMEM containing 1% (v/v) calf serum, 0.8 mM CaCl2, 50 U/mL penicillin, and 0.05 mg/ml streptomycin (700 μL), centrifuged, and reconstituted again in this medium. The cell suspension was filtered through a 40-μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences) into FACS sample tubes.

Irradiated, green fluorescent cells were isolated using a BD FACSAria sorter with a 100-μm nozzle. The signal threshold was set to 2,000 to prevent contamination by embryonic debris. Viable, single cells were identified with forward and side scatter gates, and FL1-Area (Ex: 488 nm; Em: 530 nm) intensities were used to sort fluorescent cells directly into 1 mL of chilled TRIzol (Invitrogen) in siliconized microcentrifuge tubes. Approximately 8,000 cells were collected from each group of 25–30 locally irradiated embryos.

cDNA preparation and microarray analyses

Each 1-mL TRIzol solution of sorted cells was treated with linear acrylamide (5 μL of a 5 mg/mL solution; Ambion), washed with chloroform (200 μL), and precipitated with isopropanol (500 μL) at −20 °C. The resulting RNA pellet was resuspended in water (2.8 μL) and then reverse-transcribed and amplified with a WTA2 TransPlex Complete Whole Transcriptome Amplification kit (Sigma) using the following miniaturized procedure. The RNA solution was mixed with library synthesis buffer (0.5 μL) and incubated to anneal primers. Pre-made library synthesis mix (0.5 μL library synthesis buffer, 0.5 μL library synthesis enzyme, and 0.78 μL water) was then added for reverse transcription. Amplification master mix (70 μL; 8 μL amplification mix, 1.6 μL dNTP, 0.8 μL amplification enzyme, and 63.5 μL water) was added to the reaction, and after 22 PCR cycles the amplified cDNA was isolated using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) in 30 μL EB solution. Average cDNA length was 400 bp, as determined by capillary electrophoresis (Agilent Bioanalyzer DNA 1000 kit).

Microarray analysis was performed using the Roche-Nimblegen platform (071105_Zv7_EXP) containing 385K 60-mer probes for 37,152 zebrafish transcripts. Five biological replicates were used for each experimental condition. Hybridization and data acquisition were performed by Roche-Nimblegen custom services, and the data was analyzed using ArrayStar 2 software (DNAStar) (GEO series GSE31882). When comparing fluorescent cells isolated from cFD- or ntla cMO/cFD-injected gastrula (9 hpf), genes that exhibited at least a 2-fold change in expression level with a p-value of <0.05 were classified as Ntla-dependent (87 total; GEO subseries GSE31880). For fluorescent cells isolated from 16-hpf embryos, genes associated with at least a 2-fold change in expression levels were classified as Ntla-dependent (12 total; GEO subseries GSE31881), and the Ntla-regulated expression of 9 of these genes was confirmed by in situ hybridization (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 5). All 12 genes identified in the 16-hpf dataset exhibited less than 2-fold change in expression in the 9-hpf dataset.

Detection of MO-induced RNA missplicing

RNA was isolated from at least 15 wildtype or MO-injected embryos at 10 or 16 hpf using standard TRIzol extraction methods, and trace co-purified DNA was removed with a DNA-free kit (Ambion). DNA amplicons was then generated using the SuperScript III one-step RT-PCR system (Invitrogen) with the primers listed in Supplementary Table 12, purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen), and resolved by agarose gel electrophoresis.

One- and two-color in situ hybridizations

Probe templates were generated using the SuperScript III RT-PCR system, 10- or 16-hpf zebrafish embryo RNA, and primers (Supplementary Table 13) containing a T7 sequence on the 5’ end of the reverse primer (5’-GCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGA-3’). Amplified templates were isolated with a QIAquick PCR purification kit and gel-purified if necessary. ntla and flh cDNAs for probe generation were provided by M. Halpern, pax2a cDNA was provided by W. Talbot, and fgf8a (clone cb110) and tbx6 (clone cb123) probes were obtained from the Zebrafish International Resource Center. Digoxigenin- and fluorescein-labeled RNA probes were in vitro transcribed using an mMessage mMachine T7 kit (Ambion) and purified with Centrisep size-exclusion spin columns (Princeton Separations). One- and two-color in-situ hybridizations were performed as previously described37,38.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Amacher and A. Garnett for helpful discussions; M. Halpern for providing ntla and flh cDNA; W. Talbot for pax2a cDNA; J. Mich and X. Ouyang for sharing in situ hybridization probes; and C. Crumpton for technical assistance with FACS. This work was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (R01 GM072600, R01 GM087292, and DP1 OD003792) and the March of Dimes Foundation (1-FY-08-433).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.K.C. and I.A.S., conceived the study; J.K.C., directed its execution; I.A.S. and C.L.W.P., designed, conducted, and interpreted the experiments; J.K.C. and I.A.S., wrote the manuscript with contributions from C.L.W.P.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Supplementary information is available online at http://www.nature.com/naturechemicalbiology/. Correspondence and materials requests should be addressed to J.K.C. (jameschen@stanford.edu).

References

- 1.Ouyang X, Chen JK. Synthetic strategies for studying embryonic development. Chem Biol. 2010;17:590–606. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shestopalov IA, Sinha S, Chen JK. Light-controlled gene silencing in zebrafish embryos. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;3:650–1. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouyang X, et al. Versatile synthesis and rational design of caged morpholinos. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:13255–69. doi: 10.1021/ja809933h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang X, Maegawa S, Weinberg ES, Dmochowski IJ. Regulating gene expression in zebrafish embryos using light-activated, negatively charged peptide nucleic acids. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11000–1. doi: 10.1021/ja073723s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomasini AJ, Schuler AD, Zebala JA, Mayer AN. PhotoMorphs: a novel light-activated reagent for controlling gene expression in zebrafish. Genesis. 2009;47:736–43. doi: 10.1002/dvg.20554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deiters A, et al. Photocaged morpholino oligomers for the light-regulation of gene function in zebrafish and Xenopus embryos. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:15644–50. doi: 10.1021/ja1053863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulte-Merker S, Ho RK, Herrmann BG, Nusslein-Volhard C. The protein product of the zebrafish homologue of the mouse T gene is expressed in nuclei of the germ ring and the notochord of the early embryo. Development. 1992;116:1021–32. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.4.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halpern ME, Ho RK, Walker C, Kimmel CB. Induction of muscle pioneers and floor plate is distinguished by the zebrafish no tail mutation. Cell. 1993;75:99–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulte-Merker S, van Eeden FJ, Halpern ME, Kimmel CB, Nusslein-Volhard C. no tail (ntl) is the zebrafish homologue of the mouse T (Brachyury) gene. Development. 1994;120:1009–15. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halpern ME, et al. Genetic interactions in zebrafish midline development. Dev Biol. 1997;187:154–70. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amacher SL, Draper BW, Summers BR, Kimmel CB. The zebrafish T-box genes no tail and spadetail are required for development of trunk and tail mesoderm and medial floor plate. Development. 2002;129:3311–23. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.14.3311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melby AE, Warga RM, Kimmel CB. Specification of cell fates at the dorsal margin of the zebrafish gastrula. Development. 1996;122:2225–37. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.7.2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garnett AT, et al. Identification of direct T-box target genes in the developing zebrafish mesoderm. Development. 2009;136:749–60. doi: 10.1242/dev.024703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goering LM, et al. An interacting network of T-box genes directs gene expression and fate in the zebrafish mesoderm. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9410–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1633548100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morley RH, et al. A gene regulatory network directed by zebrafish No tail accounts for its roles in mesoderm formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3829–34. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808382106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talbot WS, et al. A homeobox gene essential for zebrafish notochord development. Nature. 1995;378:150–7. doi: 10.1038/378150a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ochi H, Hans S, Westerfield M. Smarcd3 regulates the timing of zebrafish myogenesis onset. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:3529–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708594200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Showell C, Binder O, Conlon FL. T-box genes in early embryogenesis. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:201–18. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moulton JD, Yan YL. Using Morpholinos to control gene expression. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. 2008;Chapter 26(Unit 26.8) doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2608s83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gajewski M, et al. Anterior and posterior waves of cyclic her1 gene expression are differentially regulated in the presomitic mesoderm of zebrafish. Development. 2003;130:4269–78. doi: 10.1242/dev.00627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Conlon FL, Sedgwick SG, Weston KM, Smith JC. Inhibition of Xbra transcription activation causes defects in mesodermal patterning and reveals autoregulation of Xbra in dorsal mesoderm. Development. 1996;122:2427–35. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.8.2427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gansner JM, Gitlin JD. Essential role for the alpha 1 chain of type VIII collagen in zebrafish notochord formation. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:3715–26. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stemple DL, et al. Mutations affecting development of the notochord in zebrafish. Development. 1996;123:117–28. doi: 10.1242/dev.123.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Currie PD, Ingham PW. Induction of a specific muscle cell type by a hedgehog-like protein in zebrafish. Nature. 1996;382:452–5. doi: 10.1038/382452a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen JK, Taipale J, Cooper MK, Beachy PA. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling by direct binding of cyclopamine to Smoothened. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2743–8. doi: 10.1101/gad.1025302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill MM, et al. PTRF-Cavin, a conserved cytoplasmic protein required for caveola formation and function. Cell. 2008;132:113–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nixon SJ, et al. Caveolin-1 is required for lateral line neuromast and notochord development. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:2151–61. doi: 10.1242/jcs.003830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nixon SJ, et al. Zebrafish as a model for caveolin-associated muscle disease; caveolin-3 is required for myofibril organization and muscle cell patterning. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:1727–43. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franchi-Gazzola R, et al. The role of the neutral amino acid transporter SNAT2 in cell volume regulation. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2006;187:273–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2006.01552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glickman NS, Kimmel CB, Jones MA, Adams RJ. Shaping the zebrafish notochord. Development. 2003;130:873–87. doi: 10.1242/dev.00314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Draper BW, Stock DW, Kimmel CB. Zebrafish fgf24 functions with fgf8 to promote posterior mesodermal development. Development. 2003;130:4639–54. doi: 10.1242/dev.00671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chesley P. Development of the short-tailed mutant in the house mouse. J Exp Zool. 1935;70:429–459. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilkinson DG, Bhatt S, Herrmann BG. Expression pattern of the mouse T gene and its role in mesoderm formation. Nature. 1990;343:657–9. doi: 10.1038/343657a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melby AE, Kimelman D, Kimmel CB. Spatial regulation of floating head expression in the developing notochord. Dev Dyn. 1997;209:156–65. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199706)209:2<156::AID-AJA2>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nusslein-Volhard C, Dahm R. Zebrafish : a practical approach. xviii. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2002. p. 303. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bill BR, Petzold AM, Clark KJ, Schimmenti LA, Ekker SC. A primer for morpholino use in zebrafish. Zebrafish. 2009;6:69–77. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2008.0555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jowett T. Double in situ hybridization techniques in zebrafish. Methods. 2001;23:345–58. doi: 10.1006/meth.2000.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thisse C, Thisse B. High-resolution in situ hybridization to whole-mount zebrafish embryos. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:59–69. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.