Abstract

The phosphoinositide-3 kinase/Akt pathway is a vital survival axis in lung epithelia. We previously reported that inhibition of phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN), a major suppressor of this pathway, results in enhanced wound repair following injury. However, the precise cellular and biomechanical mechanisms responsible for increased wound repair during PTEN inhibition are not yet well established. Using primary human lung epithelia and a related lung epithelial cell line, we first determined whether changes in migration or proliferation account for wound closure. Strikingly, we observed that cell migration accounts for the majority of wound recovery following PTEN inhibition in conjunction with activation of the Akt and ERK signaling pathways. We then used fluorescence and atomic force microscopy to investigate how PTEN inhibition alters the cytoskeletal and mechanical properties of the epithelial cell. PTEN inhibition did not significantly alter cytoskeletal structure but did result in large spatial variations in cell stiffness and in particular a decrease in cell stiffness near the wound edge. Biomechanical changes, as well as migration rates, were mediated by both the Akt and ERK pathways. Our results indicate that PTEN inhibition rapidly alters biochemical signaling events that in turn provoke alterations in biomechanical properties that enhance cell migration. Specifically, the reduced stiffness of PTEN-inhibited cells promotes larger deformations, resulting in a more migratory phenotype. We therefore conclude that increased wound closure consequent to PTEN inhibition occurs through enhancement of cell migration that is due to specific changes in the biomechanical properties of the cell.

Keywords: phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10, acute lung injury, lung repair, epithelium, wound remodeling, cell mechanics, Akt, ERK

phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN), a dual phosphatase that dephosphorylates both lipid and protein substrates (66), was first discovered in epithelial cells and identified as TGF-β-regulated and epithelial cell-enriched phosphatase (34). The primary function of PTEN is to dephosphorylate phosphoinositide lipids that are a product of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and by doing so functionally antagonize signaling pathways that rely on PI3K activity (34, 38). Activation of PI3K and its downstream target, v-akt murine thymoma viral oncogene homolog 1 (Akt1), subsequently triggers pathways that influence cell survival, proliferation, and migration. Previously, our group and others reported that activation of the PI3K/Akt axis protects lung epithelia from programmed cell death (4, 36, 47, 48). On the basis of these initial observations, we hypothesized and subsequently reported that transient suppression of PTEN phosphatase activity enhances wound repair (29, 30).

In humans PTEN deficiency, by either polymorphic mutation or gene deletion, enhances cell proliferation and is a cause of cancer (59). Although permanent loss of PTEN function is associated with poor outcomes, our previous findings demonstrate that temporary, controlled PTEN suppression in the lung epithelium is beneficial in lung epithelial repair following injury. Importantly, we have observed that PI3K/Akt signaling in primary human lung epithelia occurs subsequent to PTEN inhibition and without further addition of agonists. Consistent with these observations, others have reported similar effects in cardiomyocytes during ischemia-reperfusion (39), corneal and skin epithelia (76), and gastric mucosal cells (65). Although activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway plays a role in facilitating epithelial repair consequent to PTEN inhibition, PTEN is pleiotropic by virtue of multiple downstream pathways directly affected by its phosphatase activity, and the importance of these other pathways remains unclear. Furthermore, it is not clear how activation of PI3K signaling influences the biomechanical mechanisms of wound repair. We therefore wanted to expand on our previous investigations and determine whether PTEN inhibition enhances cell proliferation, cell migration, or both following mechanical injury and determine how PTEN inhibition influences cellular biomechanics.

In the setting of acute lung injury, it is well established that the dynamic mechanical environment in the lung influences epithelial injury and repair (10, 16, 64, 67, 68). In addition to stretch-induced injury, the large surface-tension forces generated during the reopening of edematous and atelectatic airways/alveoli cause necrosis, disruption of the epithelium, and activation of inflammatory pathways (5, 18, 23, 75). Whereas most investigations have attempted to minimize cell injury by altering the magnitude of external mechanical forces (i.e., surfactant therapy to minimize surface-tension forces) (5), we have pursued an alternative approach where changes in the intrinsic biomechanical properties of the epithelial cell are used to minimize the injury caused by external forces (74) and to mitigate mechanically induced inflammation in lung epithelia (23). Recently, Waters and colleagues (69) reported that changes in the mechanical properties of the cell might also facilitate wound repair and that external mechanical forces inhibit PI3K and cell migration (15). In this context, the influence of PTEN-associated signaling on cellular mechanics and cell migration was not evaluated. In this investigation we determined whether PTEN inhibition and the subsequent activation of downstream signaling pathways alter the mechanical properties of lung epithelia in a manner that improves cell migration and wound repair. Herein we demonstrate that inhibition of PTEN induces significant changes in cell mechanical properties that, in conjunction with the associated changes in biochemical signaling, account for enhanced wound repair. Together with our previously reported findings, we contend that inhibition of PTEN lipid-phosphatase activity in lung epithelial cells enhances repair following injury by activating biochemical signal events, which alter the intrinsic biomechanical properties of the cell, thereby enhancing cell migration without significant influence on cell proliferation. Whereas the irreversible loss of PTEN phosphatase function is associated with malignancy, we propose that controlled, temporary suppression of PTEN is beneficial in the context of lung epithelial repair and that further investigation of PTEN as a molecular target for the prevention or treatment of lung injury is warranted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

The PTEN inhibitor bisperoxovanadium derivative [bpV (phen)] was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA). Inhibitors of Akt (LY240092) and ERK (UO126) were purchased from CalBiochem (La Jolla, CA).

Cell Cultures

Primary human upper airway epithelial cells (hUAECs) and the human transformed lung epithelial cell line (BEAS2B) were used in this study. hUAECs were isolated following enzymatic dissociation from the trachea, bronchi, and bronchioles of adult donor lungs, seeded onto collagen-coated, semipermeable membranes (0.6 cm2; Millicell; Millipore, Bedford, MA) and grown at an air-liquid interface as previously described (24). Results in this investigation were derived from two different donors obtained during the course of this investigation. In all experiments, primary cultures were evaluated at a minimum of 2 wk after initial seeding. hUAECs were maintained in a 1:1 mixture of DMEM and Ham's F12 media (DMEM/F12), supplemented with 2% Ultroser G (BioSepra; Villeneuve, La Garenne, France) and antibiotics unless otherwise stated. Human lungs were collected with approval from The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board. For the scrape wound model, primary cells were seeded onto 24-well plates in regular medium as described above and allowed to attach and form a monolayer before applying the scrape wound. BEAS2B cells (ATCC) were cultured in small airway growth medium with 2% FBS. All cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% carbon dioxide. Serum was routinely withdrawn from the cultures the day before each experiment to minimize growth factor-related signal activation and background noise.

Mechanical Wound Model for Differentiated hUAECs

Initially 1 × 106 hUAECs cells/well were seeded onto 24-well plates and allowed to establish monolayers and then replaced with serum-free medium the day before each experiment. Differentiated hUAECs were then cultured at an air-liquid interface in a Transwell insert. A mechanical, concentric scrape wound was reproducibly achieved using a syringe tip. The Transwell surface was washed with PBS three times to remove all cell debris immediately after the wound was generated. Fresh medium, with or without the PTEN inhibitor, was replaced immediately following creation of the scrape wound and removal of floating cells and debris. Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) was evaluated to determine monolayer integrity out to 6 days after establishing the wound. A nonlinear regression curve fit was utilized using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software to determine TEER recovery. Evaluation of the TEER plateau followed by one phase association under exponential function was utilized for kinetic analysis. Metric analysis of TEER recovery is expressed as T50, time to 50% recovery as well as slopeT20–80%, representing the linear rate of wound closure compared between different treatment groups.

Western Analysis

Cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA) was directly added to BEAS2B cell cultures after removing medium and washing with cold PBS at designated time points. Whole cell lysates were collected and centrifuged at 14,000 revolution/min for 10 min at 4°C. Supernatant was measured for protein concentration (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and then mixed with loading buffer (Bio-Rad). Samples were boiled at 100°C for 5 min, separated on 12% PAGE gel (Bio-Rad), and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Bioscience, Buckinghamshire, UK). Membranes were blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat milk (Bio-Rad) in TBS/0.1% Tween 20 for 1 h at room temperature followed by incubation with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After being washed, membranes were incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature and developed (ECL kit, Amersham Bioscience). The antibodies utilized in this study were anti-β-actin (1:5,000; MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH); anti-ERK, anti-p-ERK, anti-focal adhesion kinase (FAK) (1:1,000; Cell Signaling); anti-p-FAK (1:1,000; Cell Signaling); anti-p27 (1:1,000; Cell Signaling); goat anti-mouse IgG-horseradish peroxidase (1:3,000; Cell Signaling); and goat anti-rabbit IgG-horseradish peroxidase (1:3,000; Zymed, San Francisco, CA).

Analysis of Cell Proliferation

Wound closure measurements.

Cellular incorporation of 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) was used to measure cell proliferation (Click-iT EdU Imaging Kit; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). EdU is a nucleoside analog of thymidine, and it is incorporated into DNA during active DNA synthesis (56). Detection is based on a copper-catalyzed covalent reaction between an azide-labeled Alexa Fluor 555 and an alkyne from the EdU thymine analog. The small size of the Alexa fluorophor confers higher sensitivity at the same time requiring milder labeling conditions compared with the standard bromodeoxyuridine assay. BEAS2B cells were used for these experiments and plated in a standard six-well cell culture plate. Upon confluence, cells were serum starved overnight, followed by treatment with 1 μM bpV (phen) for 30 min; control, untreated samples were similarly prepared. A reproducible mechanical scrape wound was made in fully confluent monolayers with a 600-μm width pipette tip. Fresh medium containing 2 μM EdU nucleosides, with or without bpV (phen), was added following the removal of floating cells and debris. The original location and area of the scrape wound was immediately registered using bright-field microscopy, after which the cells were placed back into the incubator. After 24 h the cell samples were fixed in 4% formaline buffered in PBS and processed for EdU detection per the Click-iT EdU Imaging Kit instructions. Briefly, the cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 detergent and incubated with the EdU detection buffer containing Alexa Fluor 555. At the same time the cells were also nuclear stained with 4 μM bisbenzimide (Calbiochem). Following fixation and staining, the samples were imaged in PBS using an automated Olympus IX81 microscope with epifluorescence capabilities (B&B Microscopes, Pittsburgh, PA). For each sample, up to 20 random fields of view were captured using a ×10 objective. For each field of view, two images were acquired: one in the red channel (excitation 545/25; emission 605/70 nm) to detect the amount of EdU/Alexa 555 incorporation and the other in the blue channel (excitation 350/50; emission 460/50 nm) to detect the total number of cells/nuclei present. Cell proliferation was evaluated by determining the percentage of proliferating cells [the ratio between the number of nuclei in the red channel (proliferating cells), and the number of nuclei in the blue channel (total number of cells)]. Image analysis was done in ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD). The outline of the wound region was drawn for each image using the zero time bright-field image, and all the subsequent analysis was applied to the wound region. The background was subtracted from each image, and all images were thresholded to the same intensity interval. We then used the Particle Analyzer module to derive the number of cell nuclei both in the red and in the blue channel.

Subconfluent monolayer measurements: DNA synthesis.

BEAS2B cells were used for these experiments and plated in 35-mm cell culture dishes. Cell were grown until ∼50% confluence, after which they were serum starved overnight, followed by treatment with 1 or 2 μM bpV (phen) for 30 min; control, untreated samples were prepared as well. After the bpV (phen) treatment, medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 2 μM EdU nucleosides, with or without bpV (phen), and the cells were placed back into incubator for an additional 24 h. Cells were then processed for EdU staining as described in the previous paragraph. Image acquisition and analysis was similar with that for the wound closure measurements above, except that in this case the analysis was performed on the entire field of view (no restriction to the wound region was necessary).

Analysis of Cell Migration

A simplified Boyden chamber was used to evaluate the migration of BEAS2B cells over short to medium time intervals (2–24 h). Briefly migration chambers with an 8-μm pore size were used (Millipore). The inserts were first hydrated with PBS on both the apical and basolateral surface, and the PBS was removed immediately before plating cells. Then 0.25 × 106 cells were suspended in 200 μl DMEM with or without drug treatment and then plated onto the apical surface of the inserts with 400 μl DMEM added to the basolateral chamber. Cultures were then incubated at 37°C for up to 24 h to allow for cell migration. At designated time points, the medium on both sides was removed, and the inserts were partially submerged in 400 μl 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and incubated for 5 min to dissociate migrating cells that were attached to the basolateral surface. Inserts were then removed and discarded. The trypsin solution containing the migrating cells was placed in a 96-well plate, and, after a 30-min wait to allow cells to settle on the bottom of the wells, the cells were registered and counted with an automated bright-field microscope (Olympus IX81, B&B Microscopes).

Characterization of Cell Mechanics

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) was utilized to characterize the mechanical properties of BEAS2B cells during wound closure and during treatment with bpV (phen) and/or the Akt and ERK inhibitors (LY240092 or UO126) as well as during treatment with latrunculin A. AFM is a well-established live cell-scanning microscopy technique that uses a sharp tip at the end of a flexible cantilever to locally indent the sample (7). By using a well-defined shape of the AFM tip and a suitable contact elastic model, one can determine spatial variations in the apparent Young's modulus or stiffness of the sample (69). Measurements were obtained with a Bioscope II AFM (Veeco, Santa Barbara, CA) mounted on the stage of an Axiovert 200 inverted optical microscope (Zeiss, Jena, Germany). Data acquisition was done using the NanoScope version 7.30 software (Veeco). Silicon nitride triangular cantilevers (Veeco) with a nominal spring constant k = 0.01 N/m and cantilever length of 200 μm were used to indent the cells. The AFM tip was moved in the vertical direction (z) toward the cell surface, and the tip deflection (d) was recorded as a function of z. Hooke's law (F = k·d) was used to generate a force curve at that particular location (Fig. 1B). Following data acquisition, the force curves were then analyzed with a modified Hertzian model to obtain the Young's modulus at each location of the cell (69). For this calculation, data were imported into IgorPro 6.01 (WaveMetrics, Portland, OR) and analyzed using custom written software. The force applied on the cantilever was corrected for the zero-force offset that was derived from the zero contact part of the F-z curve recorded at each location. The cell indentation depth (δ) was calculated as

| (1) |

zc represents the contact point, where the AFM tip starts indenting the cell surface. Force and indentation of a four-sided pyramidal indenter can be related using a modified Hertz model (6)

| (2) |

where E and ν are the Young's modulus and the Poisson's ratio of the cell, respectively. With F = k·d, Eq. 1 and 2 become:

| (3) |

Assuming a ν = 0.5 (i.e., incompressible material), E and zc were estimated by least-squares fitting of Eq. 3 with the experimentally measured deflection (d) as function of z. To avoid substrate effects and nonlinear responses, we restricted our analysis to the lower region of the force curve (5–50-nm deflection corresponding to 0.05–0.50 nN indentation forces) (55, 69).

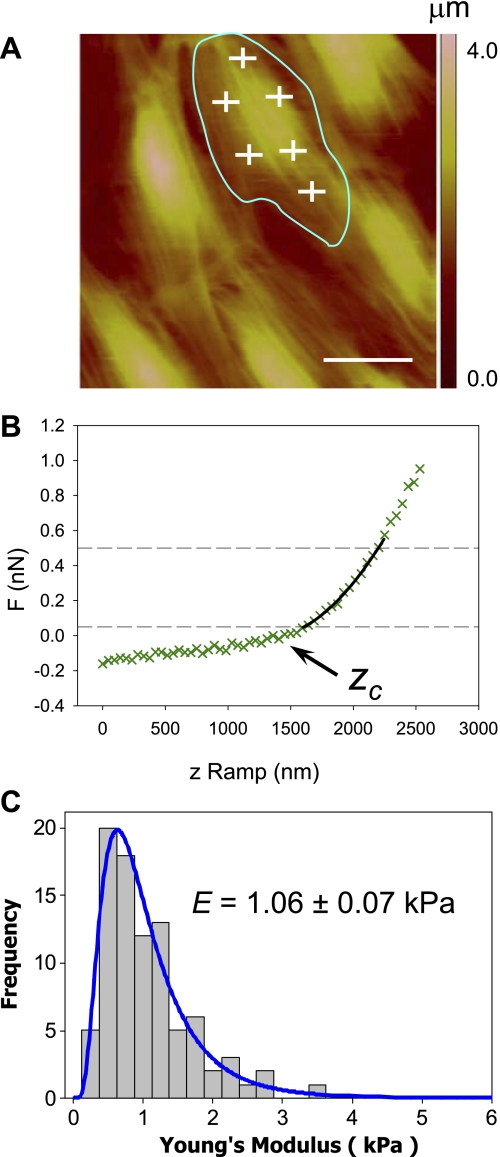

Fig. 1.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) analysis of cell mechanics. BEAS2B cells were cultured in 60-mm plastic dishes and imaged live. A: 100 × 100 μm region was scanned with the AFM, and the corresponding height image was recorded; the approximate cell outline was identified on the height image (blue), and force-displacement curves were recorded at evenly distributed locations across the cell surface (white crosses). B: typical AFM force-displacement curve (green) recorded on lung epithelial BEAS2B cells; the contact point (Zc) represents the vertical position where the AFM tip starts indenting the cell surface. The force-displacement curve was fitted with a Hertz model (black line) in the region of analysis, depicted by the horizontal dashed lines, allowing extraction of the Young's modulus; actual data is shown as green crosses. C: 5 separate scan regions were recorded at random locations on each sample (culture dish), and up to 20 separate force curves were acquired over each cell (∼100 force curves per scan region); all the data from a cell sample were pooled together and found to be characterized by a log-normal distribution; log-normal statistics were therefore used to compare the different samples/treatment conditions. The scale bar is 25 μm.

In this study, AFM was used to measure spatial variations in E during wound closure and to measure population average values of E in confluent monolayers for control-untreated cells and cells treated with different inhibitors. In both cases a ∼100 × 100 μm area was first scanned with the AFM, and a height or deflection image of the area was acquired (see Fig. 1A). Next, the Point and Shoot module from the NanoScope software was used to obtain force curves at desired locations with nanometer precision based on the AFM image (Fig. 1A). For population average measurements on confluent monolayers, 20 force curves were acquired at equally spaced locations across each cell surface; one scan area encompassed approximately five to six cells, and up to six different scan areas were measured for each sample (∼30 cells). The AFM height image allowed for identification of the different cells contours (Fig. 1A); however, some overlaps invariably occurred, so all the force curves from a cell sample were pooled into a single group (∼600 force curves). For wound closure measurements a scrape wound model as described in the previous sections was used. Scan regions were registered both near the wound edge as well as distal to the wound region (>4 mm). Force curves were acquired in a matrix pattern (Fig. 7A), and average E values were calculated as a function of the distance from the wound edge; the average E values distal from the wound edge were computed as well. As shown in Fig. 1C, Young's modulus values under each treatment condition followed a log-normal distribution, and a one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to confirm log-normal distributions (P > 0.1 for all cases). As a result, “log-transformed” statistics were used to document statistical differences between control and various treatments. All statistical analysis was done using Minitab 15.0 (Minitab, State College, PA).

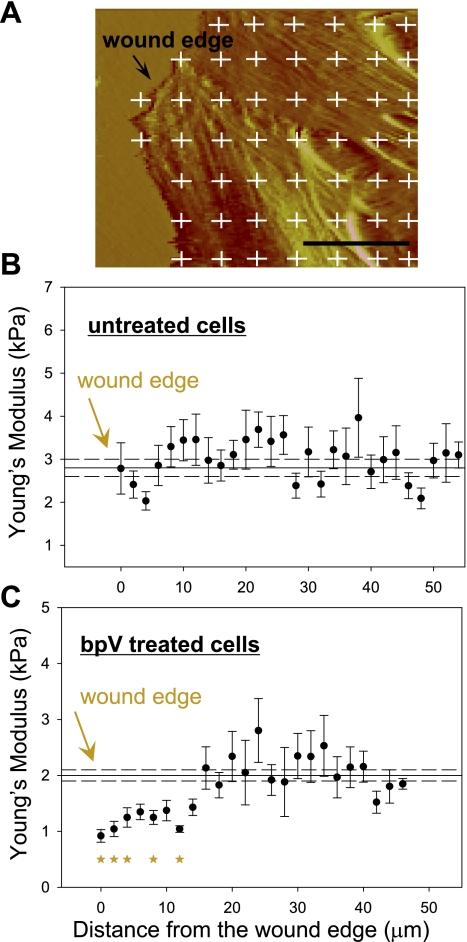

Fig. 7.

BpV (phen) treatment changes the stiffness distribution in actively migrating cells. BEAS2B cells were cultured in 60-mm culture dishes until reaching confluence. The cells were pretreated with bpV (phen) at 1 μM concentration for 30 min, after which a scratch wound was applied to the confluent monolayer; the sample was analyzed by AFM 4 h later. A: 100 × 100 μm region near the wound edge was scanned with the AFM, and the deflection image was used to specify the force curve acquisition grid (white crosses); up to 5 regions along the wound edge were scanned for each sample, and 3 regions were scanned distal from the wound edge (∼4 mm). B and C: Young's modulus values (average value ± SE) are plotted as a function of the distance from the wound edge (solid circles) for both treated and untreated cells. The average Young's modulus distal from the wound edge was plotted as reference along with the wound edge measurements (average value ± SE), solid and dashed lines, respectively; n = 30, *P < 0.05. The scale bar is 25 μm.

Characterization of Actin Cytoskeleton by Fluorescence Microscopy

Confluent monolayer.

BEAS2B cells were seeded on 35-mm cell culture dishes and upon reaching confluence were treated with 1 μm bpV (phen) for 3 h as described above. This treatment interval was chosen to correlate with the AFM stiffness measurements on confluent monolayers. Following bpV (phen) treatment the cells were washed three times with PBS and fixed in 4% formalin for 10 min. Cells were then permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 and stained for F-actin using Alexa 488 phalloidin (Invitrogen); the cells were also nuclear-stained with 4 μM bisbenzimide (CalBiochem). Similar samples were prepared for control-nontreated cells as well as for positive control cells that were treated with 0.2 μM latrunculin A. Following fixation and staining, the samples were imaged in PBS using an Olympus IX81 microscope with epifluorescence capabilities (B&B Microscopes). Alexa 488 phalloidin was imaged using a green filter (excitation 470/40; emission 525/50 nm), and the nuclear stain was imaged using a blue filter (excitation 350/50; emission 460/50 nm). For each sample up to eight random fields of view were captured using a ×10 objective. Image analysis was done in ImageJ, the background was subtracted from each image, and the average pixel intensity was calculated for the green (actin) channel. The respective blue (nuclear) channel image was used to determine the number of cells (nuclei) in each field of view. For each image the average actin signal intensity was normalized to the number of cells to obtain the normalized actin intensity.

Wound edge measurements.

BEAS2B cells were seeded on six-well cell culture plates, and, upon reaching confluence, the cells were serum starved overnight, followed by treatment with 1 μM bpV (phen) for 30 min; control, untreated samples were prepared as well. A reproducible mechanical scrape wound was made in fully confluent monolayers with a 1,200-μm width pipette tip. Fresh medium with or without bpV (phen) was added following the removal of floating cells and debris. The original location and area of the scrape wound was immediately registered using bright-field microscopy, after which the cells were placed back into the incubator. The samples were fixed at the following time points: 0, 4 and 24 h; the 4-h time point was used to correlate with the AFM measurements at the wound edge that were performed at the same time after wounding. Samples were imaged using a protocol similar to the one outlined above for the confluent monolayer. However, a ×4 objective was used to allow for registration of the entire wound region. To analyze actin intensity, small regions of interest (ROI) were selected near the wound edge, which corresponded to a similar ROI analyzed during the AFM experiments (Fig. 8A). Due to the narrow dimension of the ROIs, the number of nuclei per ROI did not correlate well with the number of cells fully encompassed by the ROI, so the direct/unnormalized average pixel intensity in the green (actin) channel was used to evaluate the actin density.

Fig. 8.

BpV (phen) treatment does not alter the actin cytoskeleton of the cell at the wound edge. Lung bronchial (BEAS2B) epithelial cells were cultured in 35-mm culture plates until reaching confluence. The cells were pretreated with bpV (phen) at a 1 μM concentration for 30 min, and a scratch wound was applied to the confluent monolayer using a pipette tip; samples were fixed and stained with Alexa 488-conjugated phalloidin at designated time intervals. A: fluorescent images of control-untreated samples (a–c) and bpV (phen)-treated samples (d–f). Multiple regions of interest were selected at the wound edge (region between the dotted red lines, inset a), and image analysis was used to quantify the actin fluorescent signal intensity (arbitrary units). B: no significant difference in fluorescent intensity was detected between the control and the bpV (phen)-treated samples at the time points investigated; a significant decrease in F-actin density was recorded at the 24-h time point for both the control and the treated sample. Scale bar is 50 μm; mean values are shown ± SE; n = 10.

Statistical Analysis

For experiments involving only two study groups the Student's two sample t-test was used to compare the treatment groups with relevant controls. ANOVA followed by post hoc tests for multiple comparisons were used to evaluate dose response and time course studies as well as other experiments involving more than two study groups. For data sets that did not follow a normal distribution the Mann-Whitney test was used for experiments involving only two study groups (Fig. 6D), and the Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA was used for experiments involving more than two study groups (Fig. 4B and D; Fig. 9B). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

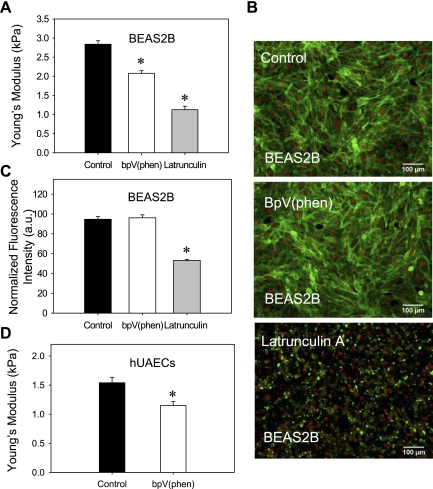

Fig. 6.

BpV (phen) treatment decreases the stiffness of lung epithelial cells. A: lung bronchial (BEAS2B) epithelial cells were cultured in 60-mm culture dishes and measured live with the AFM after treatment with 1 μM bpV (phen) for 30 min or 0.2 μM latrunculin A for 30 min. Both bpV (phen) and latrunculin A treatments were found to induce a significant decrease in Young's modulus values (cellular stiffness) compared with the control-untreated samples. B: similar cell samples were fixed and stained with Alexa 488-conjugated phalloidin (actin); nuclear staining is depicted in red. C: actin fluorescent intensity was quantified using image analysis and normalized to the number of cells (nuclei) in the field of view; bpV (phen) does not significantly alter the actin cytoskeleton; as expected latrunculin A induces a clear dissolution of the actin cytoskeleton. D: hUAECs were cultured in 60-mm culture dishes and measured live with the AFM after treatment with 1 μM bpV (phen) for 30 min. Treatment with bpV (phen) was found to induce a significant decrease in Young's modulus values (cellular stiffness) compared with the control-untreated samples. Scale bars are 50 μm; mean values are shown ± SE; n = 500 (A) and n = 8 (C), *P < 0.05; a.u., arbitrary units.

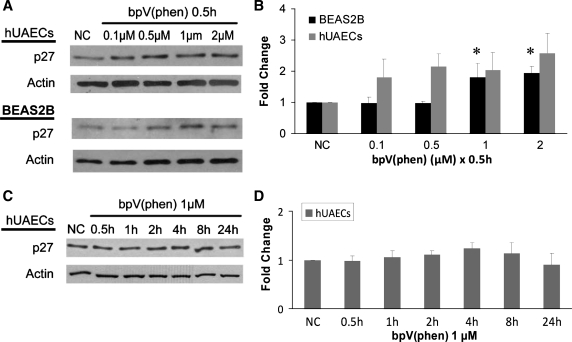

Fig. 4.

PTEN inhibition alters p27 expression. A: BEAS2B and hUAEC cultures were treated with increasing concentrations of bpV (phen) (0 to 2 μM) for 0.5 h, and Western blot analysis was conducted. B: densitometric analysis of A blots shows an increase in p27 expression with increased bpV (phen) concentration (data are means ± SE; n = 3; *P < 0.05). C: hUAEC cultures were treated with 1 μM bpV (phen) for up to 24 h, and Western blot analysis was conducted. D: densitometric analysis of C blots shows a small variation in p27 expression across various time intervals; however, the variation was not found to be statistically significant (data are means ± SE; n = 3; P > 0.05 for all lanes).

Fig. 9.

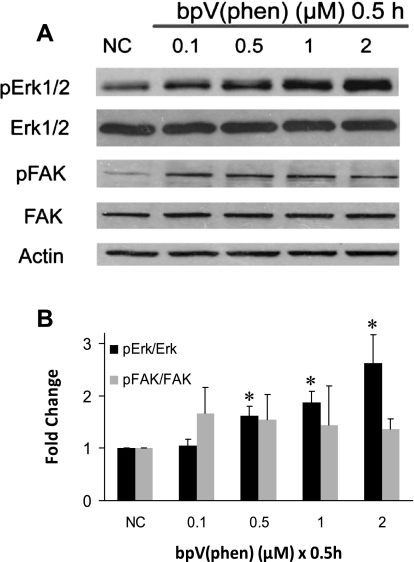

PTEN inhibition increases ERK but not focal adhesion kinase (FAK) activation. A: BEAS2B cultures were treated with increasing concentrations of bpV (phen) (0 to 2 μM) for 30 min, and Western analysis was conducted on total cell lysates. B: densitometric analysis of A blots shows that bpV (phen) treatment resulted in increased phosphorylation of ERK but not FAK within 30 min. Data are means ± SE; n = 3; *P < 0.05 for statistical significance.

RESULTS

Enhanced Wound Closure Following PTEN Inhibition in hUAECs

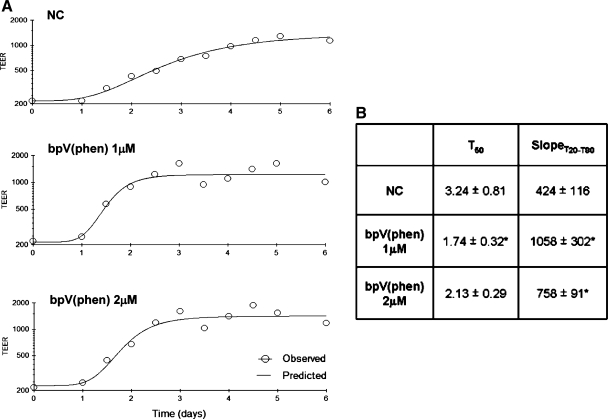

A mechanical scrape wound was first established on fully differentiated cultures of hUAECs grown at an air-to-liquid interface and then exposed to bpV (phen) at doses previously reported to specifically inhibit PTEN (30). PTEN inhibition induced a faster recovery of monolayer integrity, as measured by increasing TEER (Fig. 2A). As shown, reestablishment of high monolayer TEER (recovery) occurred in a shorter period of time with bpV (phen) (1 and 2 μM) compared with the nontreated control group (Fig. 2B). Kinetic analysis revealed a quicker recovery rate as measured by both a shorter T50 and sharper slopeT20–80 at both doses over the 6-day monitoring interval, indicating that PTEN inhibition facilitated faster restoration of lung epithelial monolayer integrity following injury.

Fig. 2.

Phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) inhibition accelerates lung epithelial would closure. A: serial measures of transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) were obtained and demonstrate monolayer recovery out to 6 days after a mechanical wound was generated in Primary human upper airway epithelial cells (hUAECs) grown on Transwells without any treatment (top) or with 1 or 2 μM of the PTEN inhibitor bisperoxovanadium derivative [bpV (phen)] (middle and bottom). B: metric analysis of TEER recovery is expressed by T50, the time to 50% recovery, as well as slopeT20–80, the linear section of the curve between T20 and T80 (mean values from 3 separate experiments are shown ± SD; *P ≤ 0.05 compared with the nontreated control, NC, group).

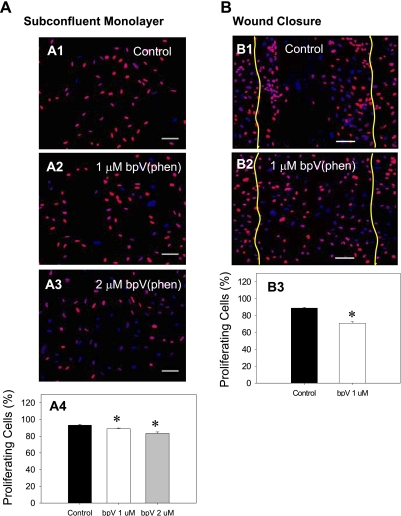

PTEN Inhibition Does Not Induce Cell Proliferation

To study the possible role of cell proliferation in wound closure enhancement, we utilized two different approaches. First, we directly assayed DNA synthesis by measuring incorporation of the thymine analog EdU. Detection of the incorporated EdU was done using fluorescent microscopy that allowed us to characterize the percent proliferation in actively migrating cells with spatial resolution. When BEAS2B cells were cultured as a subconfluent monolayer and then exposed to either 1 μM or 2 μM bpV (phen), both conditions induced a small decrease in the percentage of proliferating cells compared with the control, untreated cells (88.86 ± 0.8, 83.32 ± 1.7, and 93.2 ± 1.1%, respectively; P < 0.05) (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

PTEN inhibition does not increase cell proliferation. DNA synthesis was followed by fluorescent microscopy detection of 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation (red); the cell nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst (blue). Image analysis was used to quantify the percentage of proliferating cells (stained positive for EdU). A: subconfluent BEAS2B cultures were treated with increasing concentrations of bpV (phen) (nontreated control, 1 and 2 μM), and the samples were fixed and processed for detection of EdU incorporation after 24 h. Analysis of A1-A3 reveals a dose-dependent decrease in the number of proliferating cells during bpV (phen) treatment A4. B: a scratch wound was applied to confluent BEAS2B monolayers, and 24 h later the samples were fixed and processed for detection of the incorporated EdU; the initial wound area was recorded using bright-field microscopy immediately after wounding (yellow lines). Analysis of B1–B2 images reveals that bpV (phen) treatment induces a small decrease in the percentage of proliferating cells in the wound region (B3). Scale bars are 100 μm; data are means ± SE; n > 10; *P < 0.05.

We investigated BEAS2B cell proliferation in a scratch wound model, specifically evaluating cell proliferation in the wound region (the region of active cell migration). For these studies, we used a 1 μM bpV (phen) concentration to correlate with the treatment conditions used for most other migration/biomechanics measurements presented herein. As shown in Fig. 3B, bpV (phen) treatment was found to induce a significant decrease in the percentage of proliferating cells compared with the control, untreated cells (70.9 ± 1.8 vs. 88.8 ± 0.9%; P < 0.05).

As we previously reported (30), both Akt and GSK3 phosphorylation are elevated following bpV (phen) treatment, so we evaluated the downstream cell-cycle counterregulator p27. p27 binds to CDK, causing cell-cycle arrest at G1-S phase (22). Presumably, if cell cycle progression is triggered in an Akt/GSK3/p27-dependent manner, we would observe a decrease in p27 protein levels following PTEN inhibition. As shown in Fig. 4B, bpV (phen) exposure for 0.5 h resulted in an increase in p27 protein levels indicative of decreased proliferative activity. A similar trend was observed for both BEAS2B and primary lung epithelia although the increase in p27 levels was statistically significant only in BEAS2B cultures [at 1 and 2 μM bpV (phen) dose]. A time course study of hUAEC cells exposed to 1 μM bpV (phen) for up to 24 h exhibited a similar trend toward an increase in p27 levels although the increase was not statistically significant. These findings are consistent with previous results involving EdU incorporation and together confirm that, under the conditions studied, wound closure enhancement following PTEN inhibition is not a consequence of increased cell proliferation.

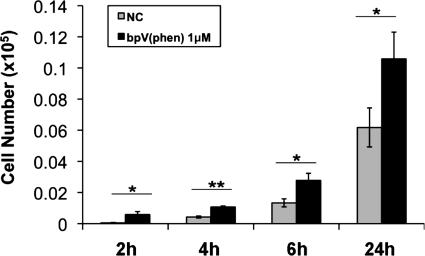

PTEN Inhibition Induces Cell Migration

Knowing that cell proliferation was not altered following PTEN inhibition and that wound closure is significantly accelerated, we next conducted studies to determine whether cell migration plays a prominent role in the early stages of wound recovery. Using epithelial migration chambers, we observed that BEAS2B cell migration is significantly increased following exposure to bpV (phen) 1 μM as early as 2 h following PTEN inhibition and that this effect is sustained out to at least 24 h of treatment (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

PTEN inhibition increases lung epithelial cell migration. BEAS2B cultures were treated with or without bpV (phen) (1 μM) following adherence to the apical surface of a standard epithelial cell migration chamber. Cells that migrated through the insert into the basolateral chamber were enumerated at 2, 4, 6, and 24 h. PTEN inhibition via bpV (phen) resulted in a significant increase in cell migration compared with nontreated control cultures (NC). Data are means ± SD; n = 3; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001.

PTEN Inhibition Alters Cellular Mechanics

To investigate the potential effects of PTEN inhibition on the mechanical properties of the cell, we used AFM to measure the population average values of the Young's modulus (E) in untreated and bpV (phen)-treated lung epithelial cells. As shown in Fig. 6A, PTEN inhibition in BEAS2B cells via bpV (phen) treatment induced a statistically significant (P = 0.001) decrease in E (i.e., a decrease in cellular stiffness). The average E values ± SE were 2.84 ± 0.08 kPa for the untreated cells and 2.08 ± 0.07 kPa for the bpV (phen)-treated cells. As a positive control we also measured E in cells treated with latrunculin A, a reagent known to induce actin depolymerization and a significant decrease in E (74). Indeed, treatment with latrunculin A resulted in significantly lower Young's modulus values with an average E of 1.12 ± 0.09 kPa. Concomitant fluorescent imaging of the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 6B) showed similar staining distribution for both the control and the bpV (phen)-treated samples. Quantification of F-actin density (Fig. 6C) revealed no significant difference in the normalized average pixel intensity between the control and the bpV (phen)-treated samples (94.69 ± 2.65 and 96.09 ± 3.08 au, respectively, with a P value of 0.74). As expected treatment with latrunculin A resulted in dissolution of the actin cytoskeleton (Fig. 6B) with a significant decrease in F-actin density compared with the control, untreated sample (94.69 ± 2.65 and 53.18 ± 1.08 au, respectively, with a P value <0.01). These results indicate that changes in cell mechanics following bpV (phen) treatment are not due to significant alteration of the actin cytoskeleton.

To verify that the observed effect of PTEN inhibition on cellular mechanics is conserved in primary cells, we performed similar experiments using hUAEC cultures. AFM measurements of cellular stiffness in primary cell monolayers revealed that 1 μM bpV (phen) treatment induces a significant decrease in the Young's modulus [1.54 ± 0.09 kPa for the untreated cells and 1.15 ± 0.06 kPa for the bpV (phen)-treated cells with a p value < 0.01] (Fig. 6D).

AFM was also used to investigate the effect of PTEN inhibition on the mechanical properties of migrating cells during wound closure. For these studies, we introduced a mechanical scratch wound in confluent monolayers of BEAS2B cells and then measured the Young's modulus as a function of the distance from the wound edge (Fig. 7A). As shown in Fig. 7, B and C, bpV (phen) treatment preferentially decreased cellular stiffness at the wound edge. The reduced stiffness near the wound edge in bpV (phen)-treated cells (Fig. 7C) was statistically different from the average stiffness of bpV (phen)-treated cells distal to the wound edge (P < 0.05). Overall, bpV (phen) treatment resulted in a ∼55% reduction in cell stiffness at the wound edge compared with a 25% reduction in stiffness in cells distal to the wound edge. Note that the solid and dashed lines in Fig. 7, B and C, represent average Young's modulus ± SE for cells distal to the wound edge. In contrast, the Young's modulus values at the wound edge for control nontreated cultures were similar and not statistically different (P = 0.2) than the average stiffness of cells distal to the wound edge (Fig. 7B).

To verify that alteration of cell stiffness distribution induced by bpV (phen) treatment was not due to dissolution of the actin cytoskeleton, we performed fluorescent measurements of the F-actin density at the wound edge. As shown in Fig. 8, A and B, there was no significant difference in the average pixel intensity between the control and the bpV (phen)-treated samples at the time points investigated (0, 4, and 24 h, P value > 0.25). We did observe a significant decrease in F-actin density at the 24-h time point for both the control and the bpV (phen)-treated sample, which we attribute to a large amount of cell spreading at that time point compared with the earlier time points when the cells were more compacted.

PTEN Inhibition Activates ERK Phosphorylation

To determine the signal transduction pathways responsible for enhanced wound closure and cell migration during PTEN inhibition, we examined candidate signaling molecules, which are known to be regulated by PTEN, including mitogen-activated protein kinase ERK1/2, and FAK. As shown in Fig. 9, the extent of FAK phosphorylation, presumably via dephosphorylation, which is transmitted by the protein phosphatase activity of PTEN, was not significantly altered during treatment with bpV (phen) between 0.1 to 2 μM following a 0.5-h exposure in BEAS2B cells. However, it is possible that PTEN inhibition might affect FAK in migrating cells and not confluent cells as measured here. ERK, which is known to influence cell migration and mobility (33), was activated as shown by increased phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner by bpV (phen) over a dosage range of 0.1 to 2.0 μM for 0.5 h (Fig. 9). On the basis of these and previous findings (30), we contend that wound closure enhancement following PTEN inhibition involves activation of the Akt and the ERK pathways.

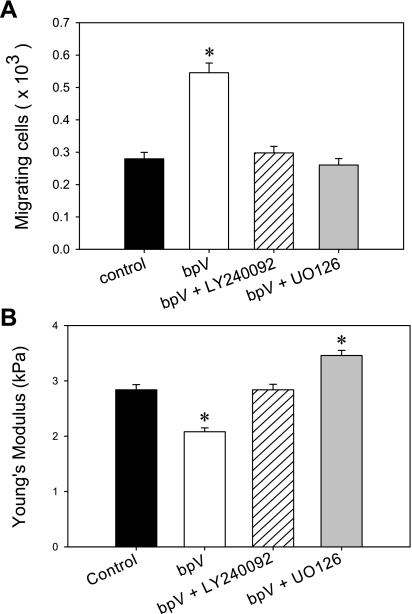

PTEN Effects on Cell Migration are Mediated by Akt and ERK Signaling

To investigate the impact of Akt and ERK signaling during PTEN inhibition on lung epithelial cell migration, we measured the migration of BEAS2B cells using migration chambers. First, as expected, inhibition of PTEN signaling with bpV (phen) at a dose of 1 μM resulted in a statistically significant increase (P < 0.05) in the number of migrating cells at the 4-h time point (Fig. 10A). Next, we examined the combined effect of PTEN inhibition and Akt or ERK inhibition, utilizing LY240092 or UO126, specific inhibitors of the Akt and ERK signaling pathways, respectively. As shown, treatment with either LY240092 or UO126 concurrently with bpV (phen) led to a significant reduction in the number of migrating cells similar to that of the untreated control group. These results demonstrate that PTEN-dependent effects on cell migration via bpV (phen)-mediated inhibition require activation of the downstream signaling intermediates Akt and ERK.

Fig. 10.

PTEN effect on cell migration and mechanics is mediated by Akt and ERK signaling. A: lung bronchial (BEAS2B) epithelial cell migration was evaluated in a simplified Boyden chamber assay. The cells were seeded on the apical side of a polytetrafluoroethylene Transwell insert (8-μm pore size) and allowed to migrate for 4 h at 37°C. The cells that migrated onto the basolateral surface were dissociated with trypsin and counted. BpV (phen) treatment alone (1 μM) induced a significant increase in the number of migrating cells with respect to the control sample. Addition of either LY240092 (Akt inhibitor) or UO126 (ERK inhibitor) at 10 μM, concurrently with 1 μM bpV (phen), reduced the number of migrating cells back to the untreated, control levels. Mean values are shown ± SE; n = 20, *P < 0.05. B: BEAS2B cells were cultured in 60-mm culture dishes, and cell stiffness/Young's modulus was evaluated with AFM. 1 μM bpV (phen) treatment resulted in a decrease in the Young's modulus (i.e., decrease in cellular stiffness) with respect to the control samples, whereas the addition of LY 24009 concurrently with 1 μM bpV (phen) resulted in no change in cellular stiffness. Addition of UO126 concurrently with 1 μM bpV (phen) resulted in higher values for the Young's modulus. Mean values are shown ± SE; n = 500, *P < 0.05.

PTEN Effects on Cell Mechanics are Mediated by Akt and ERK Signaling

We then used AFM measurements of cell stiffness to investigate whether the downstream signaling targets, Akt and ERK, influence the effect of PTEN inhibition on cell mechanics. As before, treatment with bpV (phen) alone resulted in a statistically significant decrease in Young's modulus, E (Fig. 10B). This decrease in E was not observed when cells were treated with a combination of bpV (phen) and the Akt inhibitor LY240092 concurrently (Fig. 10B). The average Young's modulus measured under nontreated control conditions (2.84 ± 0.08 kPa) was not statistically different than the value measured during simultaneous PTEN and Akt inhibition (2.83 ± 0.04 kPa) (P = 0.8). Interestingly, concurrent treatment with both bpV (phen) and the ERK inhibitor UO126 resulted in a statistically significant increase in E (3.46 ± 0.09 kPa; P = 0.003) compared with the control sample. These results indicate that the decrease in cell stiffness observed during PTEN inhibition depends on activation of both the Akt and ERK signaling pathways. Furthermore, we observed an inverse correlation between cell migration and cell stiffness and therefore conclude that decreased cellular stiffness is likely an important component of enhanced migration during PTEN inhibition.

DISCUSSION

Injury to the lung epithelium can be caused by multiple factors including infection, inflammation, inhalation, or aspiration of noxious substances, as well as physical trauma (mechanical ventilation). Initial wound closure and repair by the lung epithelium occurs primarily by mechanisms that involve cell spreading and migration, whereby cells adjacent to the wound migrate and spread to cover denuded surfaces (13). The mechanisms of epithelial wound healing involve complex interactions between initiating factors, extracellular matrix components, signaling pathways, and structural components. It is understood that the dynamic remodeling that occurs during cell spreading and migration relies on the establishment of directional polarity of the migrating cells and extension of filopodial and lamellipodial protrusions in the direction of migration (25, 28, 31, 53). In addition, a variety of signaling intermediates including RhoA, Rac1, and PI3K has been reported to be involved in these processes (14). Recent studies indicate that changes in the of the cell facilitate the migratory phenotype required for migration and rapid wound closure (63, 69). However, elucidation of the many steps involved in efficient injury repair remains to be fully understood.

In this study we demonstrate that inhibition of PTEN, a dual phosphatase that functionally antagonizes PI3K signaling pathways, results in enhanced wound closure in both primary human epithelial cells and a related cell line. Recently, Desai et al. (15) reported that inhibition of PI3K or expression of a dominant-negative form of PI3K induced a decrease in the rate of wound closure in airway epithelial cells and that overexpression of a constitutively active form of PI3K had the opposite effect. Similar to these studies, we previously demonstrated that following overexpression of a dominant-negative form of PI3K or inhibition of PTEN utilizing an siRNA strategy the rate of wound closure is significantly decreased in lung epithelia (30). Knowing that PTEN functionally antagonizes the PI3K signaling pathway, these data are all consistent with our hypothesis that PTEN inhibition facilitates epithelial wound repair. Consistent with our findings reported herein, Desai et al. (15) have also shown that changes in PI3K-mediated signaling did not involve FAK. Perhaps most revealing, we demonstrate that enhanced wound closure following transient suppression of PTEN is attributable to enhanced cell migration and not cell proliferation. Because cellular biomechanical parameters such as cell stiffness, traction force, and cell-cell interactions influence the extent of cell migration (49, 63, 69), we hypothesized that enhanced cell migration induced by PTEN inhibition is due to alteration in the biomechanical properties of the cell. We used AFM measurements of cell stiffness to test this hypothesis and demonstrate that the Young's modulus of the cell (a measure of stiffness) was significantly lowered following PTEN inhibition with bpV (phen). Surprisingly, this effect was observed in both quiescent and migrating cells. Increased cellular stiffness is associated with reduced lamellipodia ruffling (45), increased focal adhesions area (54), and increased cell contractility (19, 43), all of which lead to a decrease in migration speed (2, 19, 35, 61). Consistent with past investigations, our findings demonstrate that the increase in cell motility following PTEN inhibition occurs subsequent to a significant decrease in cellular stiffness, resulting in a more facile phenotype.

The actin cytoskeleton provides the basic infrastructure for the maintenance of cell migration and is the major driver of the mechanical behavior of the cell. At the same time the cytoskeleton provides a controlled environment for tension development, strengthening of substrate contacts with the contractile apparatus, and force transmission to the extracellular matrix that connects to neighboring cells. Although the local density of the F-actin network is known to be closely linked with the cell mechanical properties (3, 26, 40, 62), we did not observe any significant change in cytoskeletal structure following PTEN inhibition. However, an equally important parameter governing cell stiffness is the cytoskeletal prestress developed by the contractile apparatus of the cell (43, 70, 71). It is therefore plausible that the reduced cellular stiffness observed in our study is related to change in cellular prestress. Therefore, future studies should evaluate changes in additional biomechanical factors, i.e., traction forces, following PTEN inhibition.

The biochemical mechanism by which PTEN modulates epithelial cell motility involves activation of Akt and ERK signaling pathways. Akt is a serine/threonine kinase involved in promotion of cell survival, proliferation, and metabolic responses (1, 32) and is downstream of the PI3K signaling pathway (9). Akt activation is a multistep process involving coordinated actions of several catalytic and noncatalytic molecules. Akt is a predominantly cytosolic enzyme in resting cells; however, generation of PI3K lipid products recruits Akt to the plasma membrane through its NH2-terminal PH domain (60), resulting in a conformational change that induces phosphorylation at two residues, Thr308 and Ser473, of the membrane-bound protein. It has been demonstrated that Akt not only interacts with its substrate proteins but can also form complexes with proteins that behave as regulators rather than substrates of Akt (8). Cenni et al. (11) have shown that Akt can interact with actin directly, both in vitro and in vivo, and that Akt phosphorylation is necessary for Akt and actin interactions. In a previous study (30) we have shown that PTEN inhibition increases Akt phosphorylation, and here we are showing that this event is accompanied by a concomitant increase in cell motility and decrease in cell stiffness (Fig. 10). Related to our findings, it has been shown that Rac/Cdc42 can regulate Akt activity (21, 77) and that Akt participates in the regulation of cell motility downstream of Rac and Cdc42 (27). Rac1 and Cdc42 together with RhoA form a family of small GTP-binding Rho-GTPases that are known to be involved in wound healing (41). RhoA mediates actomyosin contractile mechanisms and remodeling of stress fibers (51). Rac1 is involved in lamellipodial protrusions (52), whereas Cdc42 is important in filopodial extensions (42). Whether or not related factors other than Akt participate in PTEN-mediated effects on cell mobility in our model will require further study. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that activation of Akt signaling alters the intrinsic biomechanical properties of the cell in a manner that facilitates wound healing. On the basis of this novel observation, further investigations directed at modifying cellular biomechanics via manipulation of Akt-related factors are warranted.

Extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2) are part of a family of MAPKs that also regulate cell migration (46). Our results reveal for the first time that ERK signaling plays a role in the biomechanical changes that facilitate enhanced wound repair in the lung epithelium following PTEN inhibition. Recent reports indicate that ERK interacts with cytoskeletal structures, suggesting that localized MAPK signaling modulates Rho signaling (37, 57). At the same time considerable evidence indicates that the integration of Rho family GTPase and ERK signaling is important in the control of cell morphogenesis (20, 58). Fincham et. al. (17) have shown that ERK activity is required for FAK-mediated focal adhesion disassembly to promote cell migration. Furthermore, FAK can suppress the activities of Rho (50) and its effector ROCK (12), and it also requires ERK (44) to modulate actin and focal adhesion dynamics. Our results indicate that both Akt and ERK signaling are required for alteration in cellular mechanics subsequent to PTEN inhibition. However, under the conditions studied, PTEN inhibition did not result in an increase in FAK phosphorylation, indicating that despite ERK involvement, increased cell migration is not accounted for by changes in FAK phosphorylation status. Interestingly, the combined effect of Akt and PTEN inhibition via LY240092 and bpV (phen), respectively, reduced measures of cellular stiffness back to the baseline levels. In contrast, inhibition of ERK phosphorylation in parallel with PTEN inhibition [UO126 plus bpV (phen)] resulted in a significant increase in cellular stiffness (Fig. 10B), while there was no change in migration between the two treatment conditions. Taken together, these findings suggest a more complex interplay between the Akt and ERK pathways through their common link with the Rho GTPases signaling pathways that may exist, which requires further study.

In addition to altering population-averaged cell stiffness, treatment with bpV (phen) also significantly altered the spatial distribution of stiffness in actively migrating cells during wound closure (Fig. 7). The more motile, PTEN-inhibited cells exhibited a significant decrease in stiffness near the wound edge, an effect that was not observed in the control untreated cells. In a previous report Wagh and colleagues (69) also observed a decrease in cell stiffness near the wound edge in actively migrating lung epithelia. Recently Park et al. (43) reported that cell stiffness is linearly proportional with cytoskeletal prestress. As the region of active migration undergoes increased actin remodeling and focal adhesion turnover, it would also experience a decrease in contractility that would be consistent with our observed decrease in cell stiffness at the wound edge. However, direct measurements of cytoskeletal prestress and focal adhesion turnover in actively migrating cells are needed to test this hypothesis.

In this study, we have demonstrated that suppression of PTEN activity results in increased migration and decreased cell stiffness in both isolated cells (migration chamber studies) and in cell monolayers (wound-healing studies). For isolated cells, decreased stiffness would lead to increased deformation and migration assuming equivalent force generation. However, the biomechanical mechanisms governing collective cell migration are significantly more complex and may depend on cell-cell stress transmission, spatial distribution in traction stresses, and changes in biomechanical properties. In a recent study, Trepat et. al. (63) reported that, during collective cell migration, traction forces generated by cells many rows behind the leading edge lead to increased tensile stress within the cell sheet far from the leading edge. Thus the motion of an advancing epithelial cell sheet results from a global “tug-of-war” (63) that integrates local force generation into a global state of tensile stress. In this scenario the stiffness distribution across the cell monolayer could significantly impact the integration of local force generation into the global stress state. Therefore, future studies could use computational modeling to investigate how distributed traction forces in a cell monolayer with inhomogeneous cell material properties influence the global stress state and migration rates.

In this investigation, provocative new evidence is provided that demonstrates beneficial effects on lung epithelial cell repair following inhibition of PTEN, a phosphatase that regulates PI3K signaling. Perhaps most striking is that the impact of pharmacological inhibition of PTEN results in concomitant changes in cell signaling that were inextricably linked to changes in cellular biomechanics that positively influenced cell migration. Whereas it is easy to envision how these findings may lead to strategies aimed at improving lung repair following injury, it is not clear from these epithelial cell-specific studies whether these findings are more generalizable to the lung and other cell types involved in pathogenesis. Indeed, work by others involving lung fibroblasts has revealed that similar strategies involving PTEN inhibition may result in adverse effects that worsen the extent of injury and fibrosis (72, 73). Taken together, this indicates that the role of PTEN in lung injury and repair must be taken in context with cell specificity and the nature of the injury itself. With this in mind, further studies should be conducted to evaluate both the biological and therapeutic potential of PTEN in the setting of lung function and disease.

GRANTS

This work was supported by R01 HL086981-01 (D. L. Knoell) and NSF grant 0852417 (S. N. Ghadiali).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Lifeline of Ohio Tissue Procurement Agency.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alessi DR, James SR, Downes CP, Holmes AB, Gaffney PR, Reese CB, Cohen P. Characterization of a 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase which phosphorylates and activates protein kinase Balpha. Curr Biol 7: 261–269, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ambrosi D, Duperray A, Peschetola V, Verdier C. Traction patterns of tumor cells. J Math Biol 58: 163–181, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Azeloglu EU, Bhattacharya J, Costa KD. Atomic force microscope elastography reveals phenotypic differences in alveolar cell stiffness. J Appl Physiol 105: 652–661, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bao S, Wang Y, Sweeney P, Chaudhuri A, Doseff AI, Marsh CB, Knoell DL. Keratinocyte growth factor induces Akt kinase activity and inhibits Fas-mediated apoptosis in A549 lung epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L36–L42, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bilek AM, Dee KC, Gaver DP., 3rd Mechanisms of surface-tension-induced epithelial cell damage in a model of pulmonary airway reopening. J Appl Physiol 94: 770–783, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bilodeau G. Regular pyramid punch problem. J Appl Biomech 259: 6,1992 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Binnig G, Quate CF, Gerber C. Atomic force microscope. Phys Rev Lett 56: 930–933, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brazil DP, Park J, Hemmings BA. PKB binding proteins. Getting in on the Akt. Cell 111: 293–303, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science 296: 1655–1657, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cavanaugh KJ, Jr, Margulies SS. Measurement of stretch-induced loss of alveolar epithelial barrier integrity with a novel in vitro method. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 283: C1801–C1808, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cenni V, Sirri A, Riccio M, Lattanzi G, Santi S, de Pol A, Maraldi NM, Marmiroli S. Targeting of the Akt/PKB kinase to the actin skeleton. Cell Mol Life Sci 60: 2710–2720, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen BH, Tzen JT, Bresnick AR, Chen HC. Roles of Rho-associated kinase and myosin light chain kinase in morphological and migratory defects of focal adhesion kinase-null cells. J Biol Chem 277: 33857–33863, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Crosby LM, Waters CM. Epithelial repair mechanisms in the lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 298: L715–L731, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Desai LP, Aryal AM, Ceacareanu B, Hassid A, Waters CM. RhoA and Rac1 are both required for efficient wound closure of airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 287: L1134–L1144, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Desai LP, White SR, Waters CM. Cyclic mechanical stretch decreases cell migration by inhibiting phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-and focal adhesion kinase-mediated JNK1 activation. J Biol Chem 285: 4511–4519, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Desai LP, White SR, Waters CM. Mechanical stretch decreases FAK phosphorylation and reduces cell migration through loss of JIP3-induced JNK phosphorylation in airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L520–L529, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fincham VJ, James M, Frame MC, Winder SJ. Active ERK/MAP kinase is targeted to newly forming cell-matrix adhesions by integrin engagement and v-Src. EMBO J 19: 2911–2923, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ghadiali SN, Gaver DP. Biomechanics of liquid-epithelium interactions in pulmonary airways. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 163: 232–243, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ghosh K, Pan Z, Guan E, Ge S, Liu Y, Nakamura T, Ren XD, Rafailovich M, Clark RA. Cell adaptation to a physiologically relevant ECM mimic with different viscoelastic properties. Biomaterials 28: 671–679, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Glading A, Bodnar RJ, Reynolds IJ, Shiraha H, Satish L, Potter DA, Blair HC, Wells A. Epidermal growth factor activates m-calpain (calpain II), at least in part, by extracellular signal-regulated kinase-mediated phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol 24: 2499–2512, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Higuchi M, Masuyama N, Fukui Y, Suzuki A, Gotoh Y. Akt mediates Rac/Cdc42-regulated cell motility in growth factor-stimulated cells and in invasive PTEN knockout cells. Curr Biol 11: 1958–1962, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hlobilkova A, Guldberg P, Thullberg M, Zeuthen J, Lukas J, Bartek J. Cell cycle arrest by the PTEN tumor suppressor is target cell specific and may require protein phosphatase activity. Exp Cell Res 256: 571–577, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Huang Y, Haas C, Ghadiali SN. Influence of Transmural Pressure and Cytoskeletal Structure on NF-kappa B Activation in Respiratory Epithelial Cells. Cell Mol Bioeng 3: 415–427, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Karp PH, Moninger TO, Weber SP, Nesselhauf TS, Launspach JL, Zabner J, Welsh MJ. An in vitro model of differentiated human airway epithelia. Methods for establishing primary cultures. Methods Mol Biol 188: 115–137, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kaverina I, Krylyshkina O, Small JV. Regulation of substrate adhesion dynamics during cell motility. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 34: 746–761, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kidoaki S, Matsuda T, Yoshikawa K. Relationship between apical membrane elasticity and stress fiber organization in fibroblasts analyzed by fluorescence and atomic force microscopy. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 5: 263–272, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kim D, Kim S, Koh H, Yoon SO, Chung AS, Cho KS, Chung J. Akt/PKB promotes cancer cell invasion via increased motility and metalloproteinase production. FASEB J 15: 1953–1962, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kole TP, Tseng Y, Jiang I, Katz JL, Wirtz D. Intracellular mechanics of migrating fibroblasts. Mol Biol Cell 16: 328–338, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lai JP, Bao S, Davis IC, Knoell DL. Inhibition of the phosphatase PTEN protects mice against oleic acid-induced acute lung injury. Br J Pharmacol 156: 189–200, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lai JP, Dalton JT, Knoell DL. Phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome ten (PTEN) as a molecular target in lung epithelial wound repair. Br J Pharmacol 152: 1172–1184, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lauffenburger DA, Horwitz AF. Cell migration: a physically integrated molecular process. Cell 84: 359–369, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lawlor MA, Alessi DR. PKB/Akt: a key mediator of cell proliferation, survival and insulin responses? J Cell Sci 114: 2903–2910, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leslie NR, Yang X, Downes CP, Weijer CJ. The regulation of cell migration by PTEN. Biochem Soc Trans 33: 1507–1508, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, Podsypanina K, Bose S, Wang SI, Puc J, Miliaresis C, Rodgers L, McCombie R, Bigner SH, Giovanella BC, Ittmann M, Tycko B, Hibshoosh H, Wigler MH, Parsons R. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science 275: 1943–1947, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lo CM, Wang HB, Dembo M, Wang YL. Cell movement is guided by the rigidity of the substrate. Biophys J 79: 144–152, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lu Y, Parkyn L, Otterbein LE, Kureishi Y, Walsh K, Ray A, Ray P. Activated Akt protects the lung from oxidant-induced injury and delays death of mice. J Exp Med 193: 545–549, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. MacCormick M, Moderscheim T, van der Salm LW, Moore A, Pryor SC, McCaffrey G, Grimes ML. Distinct signaling particles containing ERK/MEK and B-Raf in PC12 cells. Biochem J 387: 155–164, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maehama T, Dixon JE. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem 273: 13375–13378, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mocanu MM, Yellon DM. PTEN, the Achilles' heel of myocardial ischaemia/reperfusion injury? Br J Pharmacol 150: 833–838, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nagayama M, Haga H, Takahashi M, Saitoh T, Kawabata K. Contribution of cellular contractility to spatial and temporal variations in cellular stiffness. Exp Cell Res 300: 396–405, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nobes CD, Hall A. Rho GTPases control polarity, protrusion, and adhesion during cell movement. J Cell Biol 144: 1235–1244, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nobes CD, Hall A. Rho, rac and cdc42 GTPases: regulators of actin structures, cell adhesion and motility. Biochem Soc Trans 23: 456–459, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Park CY, Tambe D, Alencar AM, Trepat X, Zhou EH, Millet E, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Mapping the cytoskeletal prestress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 298: C1245–C1252, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pawlak G, Helfman DM. MEK mediates v-Src-induced disruption of the actin cytoskeleton via inactivation of the Rho-ROCK-LIM kinase pathway. J Biol Chem 277: 26927–26933, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pelham RJ, Jr, Wang Y. Cell locomotion and focal adhesions are regulated by substrate flexibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 13661–13665, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pullikuth AK, Catling AD. Scaffold mediated regulation of MAPK signaling and cytoskeletal dynamics: a perspective. Cell Signal 19: 1621–1632, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ray P. Protection of epithelial cells by keratinocyte growth factor signaling. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2: 221–225, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ray P, Devaux Y, Stolz DB, Yarlagadda M, Watkins SC, Lu Y, Chen L, Yang XF, Ray A. Inducible expression of keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) in mice inhibits lung epithelial cell death induced by hyperoxia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 6098–6103, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Reinhart-King CA, Dembo M, Hammer DA. Cell-cell mechanical communication through compliant substrates. Biophys J 95: 6044–6051, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ren XD, Kiosses WB, Sieg DJ, Otey CA, Schlaepfer DD, Schwartz MA. Focal adhesion kinase suppresses Rho activity to promote focal adhesion turnover. J Cell Sci 113: 3673–3678, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ridley AJ, Hall A. The small GTP-binding protein rho regulates the assembly of focal adhesions and actin stress fibers in response to growth factors. Cell 70: 389–399, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ridley AJ, Paterson HF, Johnston CL, Diekmann D, Hall A. The small GTP-binding protein rac regulates growth factor-induced membrane ruffling. Cell 70: 401–410, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, Firtel RA, Ginsberg MH, Borisy G, Parsons JT, Horwitz AR. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science 302: 1704–1709, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Riveline D, Zamir E, Balaban NQ, Schwarz US, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Kam Z, Geiger B, Bershadsky AD. Focal contacts as mechanosensors: externally applied local mechanical force induces growth of focal contacts by an mDia1-dependent and ROCK-independent mechanism. J Cell Biol 153: 1175–1186, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rotsch C, Jacobson K, Radmacher M. Dimensional and mechanical dynamics of active and stable edges in motile fibroblasts investigated by using atomic force microscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 921–926, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Salic A, Mitchison TJ. A chemical method for fast and sensitive detection of DNA synthesis in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 2415–2420, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Spence HJ, Dhillon AS, James M, Winder SJ. Dystroglycan, a scaffold for the ERK-MAP kinase cascade. EMBO Rep 5: 484–489, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stahle M, Veit C, Bachfischer U, Schierling K, Skripczynski B, Hall A, Gierschik P, Giehl K. Mechanisms in LPA-induced tumor cell migration: critical role of phosphorylated ERK. J Cell Sci 116: 3835–3846, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Stambolic V, Suzuki A, de la Pompa JL, Brothers GM, Mirtsos C, Sasaki T, Ruland J, Penninger JM, Siderovski DP, Mak TW. Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell 95: 29–39, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Stokoe D, Stephens LR, Copeland T, Gaffney PR, Reese CB, Painter GF, Holmes AB, McCormick F, Hawkins PT. Dual role of phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate in the activation of protein kinase B. Science 277: 567–570, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Stroka KM, Aranda-Espinoza H. A biophysical view of the interplay between mechanical forces and signaling pathways during transendothelial cell migration. FEBS J 277: 1145–1158, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Su J, Brau RR, Jiang X, Whitesides GM, Lange MJ, So PT. Geometric confinement influences cellular mechanical properties II—intracellular variances in polarized cells. Mol Cell Biomech 4: 105–118, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Trepat X, Wasserman MR, Angelini TE, Millet E, Weitz DA, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ. Physical forces during collective cell migration. Nature Physics 5: 426–430, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 64. Tschumperlin DJ, Oswari J, Margulies AS. Deformation-induced injury of alveolar epithelial cells. Effect of frequency, duration, and amplitude. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162: 357–362, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tsugawa K, Jones MK, Akahoshi T, Moon WS, Maehara Y, Hashizume M, Sarfeh IJ, Tarnawski AS. Abnormal PTEN expression in portal hypertensive gastric mucosa: a key to impaired PI 3-kinase/Akt activation and delayed injury healing? FASEB J 17: 2316–2318, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Vazquez F, Sellers WR. The PTEN tumor suppressor protein: an antagonist of phosphoinositide 3-kinase signaling. Biochim Biophys Acta 1470: M21–35, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Vlahakis NE, Schroeder MA, Limper AH, Hubmayr RD. Stretch induces cytokine release by alveolar epithelial cells in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 277: L167–L173, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Vlahakis NE, Schroeder MA, Pagano RE, Hubmayr RD. Role of deformation-induced lipid trafficking in the prevention of plasma membrane stress failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166: 1282–1289, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wagh AA, Roan E, Chapman KE, Desai LP, Rendon DA, Eckstein EC, Waters CM. Localized elasticity measured in epithelial cells migrating at a wound edge using atomic force microscopy. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 295: L54–L60, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wang N, Naruse K, Stamenovic D, Fredberg JJ, Mijailovich SM, Tolic-Norrelykke IM, Polte T, Mannix R, Ingber DE. Mechanical behavior in living cells consistent with the tensegrity model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 7765–7770, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wang N, Tolic-Norrelykke IM, Chen J, Mijailovich SM, Butler JP, Fredberg JJ, Stamenovic Cell prestress D. I. Stiffness and prestress are closely associated in adherent contractile cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 282: C606–C616, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. White ES, Atrasz RG, Hu B, Phan SH, Stambolic V, Mak TW, Hogaboam CM, Flaherty KR, Martinez FJ, Kontos CD, Toews GB. Negative regulation of myofibroblast differentiation by PTEN (Phosphatase and Tensin Homolog Deleted on chromosome 10). Am J Respir Crit Care Med 173: 112–121, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. White ES, Thannickal VJ, Carskadon SL, Dickie EG, Livant DL, Markwart S, Toews GB, Arenberg DA. Integrin alpha4beta1 regulates migration across basement membranes by lung fibroblasts: a role for phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 168: 436–442, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Yalcin HC, Hallow KM, Wang J, Wei MT, Ou-Yang HD, Ghadiali SN. Influence of cytoskeletal structure and mechanics on epithelial cell injury during cyclic airway reopening. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L881–L891, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Yalcin HC, Perry SF, Ghadiali SN. Influence of airway diameter and cell confluence on epithelial cell injury in an in-vitro model of airway reopening. J Appl Physiol 103: 1796–1807, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zhao M, Song B, Pu J, Wada T, Reid B, Tai G, Wang F, Guo A, Walczysko P, Gu Y, Sasaki T, Suzuki A, Forrester JV, Bourne h, Devreotes PN, McCaig CD, Penninger JM. Electrical signals control wound healing through phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase-gamma and PTEN. Nature 442: 457–460, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Zugasti O, Rul W, Roux P, Peyssonnaux C, Eychene A, Franke TF, Fort P, Hibner U. Raf-MEK-Erk cascade in anoikis is controlled by Rac1 and Cdc42 via Akt. Mol Cell Biol 21: 6706–6717, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]