Abstract

We analyzed the association between achievement of early complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) and event-free survival (EFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase treated with imatinib 400 mg (n = 73), or imatinib 800 mg daily (n = 208), or second- generation tyrosine kinase inhibitors (n = 154). The overall CCyR rates were 87%, 91%, and 96%, respectively (P = .06); and major molecular response (MMR) rates were 77%, 87%, and 89%, respectively (P = .05). Their 3-year EFS rates were 85%, 92%, and 97% (P = .01), and OS rates were 93%, 97%, and 100% (P = .18), respectively. By landmark analysis, patients with 3-, 6-, and 12-month CCyR had significantly better outcome: 3-year EFS rates of 98%, 97%, and 98% and OS rates of 99%, 99%, and 99%, respectively, compared with 83%, 72%, and 67% and 95%, 90%, and 94%, in patients who did not achieve a CCyR. Among patients achieving CCyR at 12 months, the depth of molecular response was not associated with differences in OS or EFS. In conclusion, second tyrosine kinase inhibitors induced higher rates of CCyR and MMR than imatinib. The achievement of early CCyR remains a major determinant of chronic myeloid leukemia outcome regardless of whether MMR is achieved or not.

MedscapeEDUCATION Continuing Medical Education online.

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essential Areas and policies of the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education through the joint sponsorship of Medscape, LLC and the American Society of Hematology. Medscape, LLC is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Medscape, LLC designates this Journal-based CME activity for a maximum of 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)™. Physicians should claim only the credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

All other clinicians completing this activity will be issued a certificate of participation. To participate in this journal CME activity: (1) review the learning objectives and author disclosures; (2) study the education content; (3) take the post-test with a 70% minimum passing score and complete the evaluation at http://www.medscape.org/journal/blood; and (4) view/print certificate. For CME questions, see page 4759.

Disclosures

Elias Jabbour received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Novartis Pharmaceuticals; Hagop Kantarjian received research grants from Novartis Pharmaceuticals and Bristol-Myers Squibb; Farhad Ravandi received research funding and honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb and honoraria from Novartis Pharmaceuticals; and Jorge Cortes received research grants from Novartis Pharmaceuticals and Bristol-Myers Squibb. The remaining authors, the Associate Editor Jacob M. Rowe; and the CME questions author Laurie Barclay, freelance writer and reviewer, Medscape LLC, declare no competing financial interests.

Learning objectives

Upon completion of this activity, participants will be able to:

Compare complete cytogenic response (CCyR) rates and major molecular response (MMR) rates in patients with newly diagnosed CML-CP treated with imatinib 400 mg, imatinib 800 mg daily, or second-generation TKI.

Compare 3-year event-free survival rates, overall survival rates, and transformational-free survival rates in patients with newly diagnosed CML-CP treated with imatinib 400 mg, imatinib 800 mg daily, or second-generation TKI.

Compare CCyR and MMR as predictors of outcome in patients with newly diagnosed CML-CP.

Release date: October 27, 2011; Expiration date: October 27, 2012

Introduction

The successful introduction of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), which suppress the molecular processes driving chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), has revolutionized the management and outlook in CML.1 Imatinib mesylate therapy induced high rates of complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) and major molecular response (MMRs) and improved survival in CML.2–6 A recent 8-year follow-up of newly diagnosed patients with chronic phase CML (CML-CP) treated with imatinib in the phase 3 International Randomized Study of Interferon and STI571 (IRIS) trial reported a CCyR rate of 83% and an estimated overall survival (OS) of 93% when only CML-related deaths were considered.2 However, 17% of imatinib-treated patients do not achieve a CCyR, and ∼ 15% of patients who achieve CCyR lose their response. An additional 4%-8% of patients are intolerant of imatinib.4

Second-generation TKIs, such as dasatinib, nilotinib, and bosutinib, are more potent BCR-ABL inhibitors with demonstrated efficacy in patients resistant to or intolerant of imatinib.7–9 Dasatinib and nilotinib were first approved for patients resistant to or intolerant of prior imatinib therapy, are active against most BCR-ABL mutations with the exception of T315I, and have well-established safety profiles.10,11 Single-arm phase 2 studies12–14 first suggested, and phase 3 randomized trials later confirmed, that dasatinib and nilotinib were superior to imatinib, inducing faster and higher rates of CCyR and molecular responses. Therefore, both drugs were granted Food and Drug Administration approval as initial therapy for patients with newly diagnosed CML-CP.15,16

The achievement of an early CCyR remains the major surrogate endpoint for long-term outcome in the treatment of patients with CML treated with imatinib as it is associated with improved survival.17–19 The aims of this study were to assess the correlation between the achievement of an early CCyR and event-free survival (EFS as defined by the IRIS trial) and OS in sequential phase 2 trials run at our institution in patients with newly diagnosed CML-CP treated with imatinib and the second-generation TKI.

Methods

A total of 435 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed CML-CP were treated with imatinib 400 mg daily (n = 73), imatinib 800 mg daily (n = 208), and second-generation TKIs (n = 154; dasatinib n = 76, nilotinib n = 78) in sequential phase 2 trials. Entry criteria were similar for all trials. CML-CP was as previously defined.20 Patients were treated on University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board–approved protocols. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Response criteria were as previously described.2 Cytogenetic responses were categorized as complete (0% Philadelphia-chromosome positive [Ph+] metaphases), partial (1%-35% Ph+), or minor (36%-95% Ph+). A major cytogenetic response included CCyR plus partial cytogenetic response (ie, < 35% Ph+). Conventional cytogenetic analysis was done in bone marrow cells using the G-banding technique. At least 20 metaphases were analyzed, and marrow specimens were examined on direct or short-term (24-hour) cultures. Fifteen percent of the patients had marrow cells analyzed by fluorescent in situ hybridization only, using LSI BCR/ABL dual color extra-signal probe according to the manufacturer's instructions (Vysis). MMR was defined as a BCR-ABL/BL transcript ratio of ≤ 0.1% (international scale). A complete molecular response was defined as undetectable transcripts with an assay with a sensitivity of at least 4.5-log.5

EFS was measured from the start of treatment to the date of any of the following events (defined by the IRIS trial) while on therapy: death from any cause, loss of complete hematologic response, loss of major cytogenetic response, or progression to accelerated or blast phases. Patients who were resistant, lost their responses, or transformed did remain in the denominator (considered an event) throughout the entire follow-up. Patients were off before the evaluation time because of: (1) insurance/financial issues, (2) noncompliance, (3) death of non-CML diseases or off for other disease, (4) lost to follow-up, (5) allogeneic stem cell transplantation, (6) pregnancy, or (7) intolerance. Transformation-free survival was measured from the start of treatment to the date progression to accelerated or blast phases, last follow-up, or death from any cause. Survival probabilities were estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. Differences among variables were evaluated by the χ2 test and Mann-Whitney U test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify potential factors associated with the achievement of a 12-month CCyR and survival. Factors retaining significance in the multivariate model were interpreted as being independently predictive of 12-month CCyR. Multivariate analysis of response used the logistic regression model and survival used the Cox proportional hazard model.21–23

Results

Patients

A total of 435 consecutive patients with newly diagnosed CML-CP treated with imatinib 400 mg daily (n = 73), imatinib 800 mg daily (n = 208), and second-generation TKIs (n = 154) were analyzed. Their characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The majority had low Sokal score disease and > 90% Ph+ clone. The presence of clonal evolution with no other criteria of accelerated phase was noted in 3%, 3%, and 7% of patients receiving standard-dose imatinib, high-dose imatinib, or second-generation TKI, respectively.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Parameter | IM 400 mg | IM 800 mg | Second TKI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients treated | 73 | 208 | 154 | |

| Median age, y (range) | 48 (15-78) | 48 (17-84) | 47 (18-85) | .48 |

| Prior cytoreduction, % | 51 (73) | 95 (46) | 60 (39) | .0001 |

| Splenomegaly, % | 16 (22) | 59 (28) | 41 (27) | .56 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL, < 12.0, no. (%) | 27 (37) | 82 (39) | 71 (46) | .32 |

| WBCs, × 109/L, ≥ 10, no. (%) | 55 (75) | 178 (86) | 112 (73) | .01 |

| Platelets, × 109/L, > 450, no. (%) | 22 (30) | 68 (33) | 43 (28) | .62 |

| Peripheral blast, %, any, no. (%) | 18 (25) | 76 (36) | 43 (28) | .09 |

| Peripheral basophils, %, ≥ 5, no. (%) | 15 (21) | 60 (29) | 39 (25) | .43 |

| Marrow blast, %, ≥ 5, no. (%) | 3 (4) | 18 (9) | 9 (6) | .40 |

| Marrow basophils, %, ≥ 5, no. (%) | 7 (10) | 32 (15) | 13 (8) | .11 |

| Sokal risk, no. (%) | ||||

| Low | 50 (68) | 132 (63) | 118 (77) | .02 |

| Intermediate | 22 (30) | 57 (27) | 27 (18) | |

| High | 1 (2) | 19 (9) | 9 (6) | |

| Ph+ > 90%, % | 67/72 (93) | 195 (94) | 133 (86) | .04 |

| Clonal evolution, % | 2 (3) | 7 (3) | 11/151 (7) | .15 |

IM indicates imatinib; and WBCs, white blood cells.

Response to TKI

The median time from diagnosis to TKI therapy was 1 month (range, 0-12.4 months). The median follow-up was 110 months (range, 2-116 months) for patients receiving standard-dose imatinib, 79 months (range, 3-107 months) for those receiving high-dose imatinib, and 28 months (range, 3-59 months) for those receiving second-generation TKI. The cumulative CCyR rates were 87%, 91%, and 96%, respectively. Responses at 3, 6, and 12 months by therapy are shown in Table 2. At 3 months, the CCyR rates were 39%, 63%, and 81% (P < .001) for patients receiving standard-dose imatinib, high-dose imatinib, or second-generation TKIs, respectively, and evaluable for cytogenetic response. At 6 months, these rates were 53%, 85%, and 95% (P < .001), respectively. At 12 months, they were 66%, 90%, and 98% (P < .001), respectively.

Table 2.

CCyR at 3, 6, and 12 months by therapy

| 3 months |

6 months |

12 months |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluable | CCyR | % | P | Evaluable | CCyR | % | P | Evaluable | CCyR | % | P | |

| IM 400 mg | 70 | 27 | 39 | 70 | 37 | 53 | 68 | 45 | 66 | |||

| IM 800 mg | 199 | 125 | 63 | < .001 | 194 | 164 | 85 | < .001 | 187 | 169 | 90 | < .001 |

| Second TKI | 141 | 114 | 81 | 131 | 125 | 95 | 118 | 116 | 98 | |||

Evaluable indicates patients who received therapy and were evaluable for cytogenetic response at each time point; and IM, imatinib.

Overall outcomes

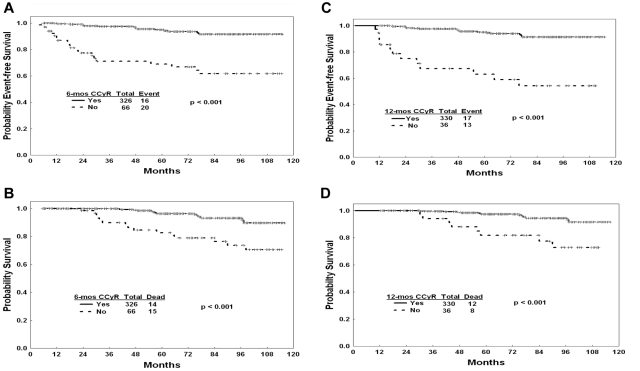

To evaluate whether the achievement of early responses confers a prognostic advantage, we compared the outcome of patients in CCyR at 3, 6, and 12 months from the start of therapy with those who were not in CCyR. As shown in Table 3, patients in CCyR at any time point had a better 3-year EFS and OS. For example, patients with and without CCyR at 6 months had a 3-year EFS probability of 97% and 72%, (Figure 1A) and OS of 99% and 90% (Figure 1B). Similarly, according to CCyR or not at 12 months, the 3-year EFS was 98% and 67%, (Figure 1C) and OS was 99% and 94% (Figure 1D). The achievement of an early CCyR was associated with survival improvement regardless of type of therapy.

Table 3.

Outcome

| 3-month CCyR |

6-month CCyR |

12-month CCyR |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | P | Yes | No | P | Yes | No | P | |

| Total group | |||||||||

| 3-year EFS | 98 | 83 | < .001 | 97 | 72 | < .001 | 98 | 67 | < .001 |

| 3-year OS | 99 | 95 | .06 | 99 | 90 | < .001 | 99 | 94 | < .001 |

| IM 400 mg | |||||||||

| 3-year EFS | 92 | 81 | .12 | 97 | 74 | .001 | 98 | 72 | < .001 |

| 3-year OS | 100 | 88 | .046 | 100 | 87 | .09 | 100 | 88 | .046 |

| IM 800 mg | |||||||||

| 3-year EFS | 97 | 84 | .005 | 97 | 68 | < .001 | 98 | 58 | < .001 |

| 3-year OS | 98 | 97 | .93 | 99 | 92 | .001 | 99 | 100 | .03 |

| Second TKI | |||||||||

| 3-year EFS | 100 | 80 | < .001 | 99 | 67 | < .001 | 99 | NA | NA |

| 3-year OS | 100 | 100 | NA | 100 | 100 | NA | 100 | NA | NA |

| P (EFS/OS) | .07/.3 | .56/.81 | .9/.6 | ||||||

IM indicates imatinib; and NA, not applicable

Figure 1.

Outcome by CCyR at 6 and 12 months. (A) EFS by CCyR at 6 months. (B) OS by CCyR at 6 months. (C) EFS by CCyR at 12 months. (D) OS by CCyR at 12 months.

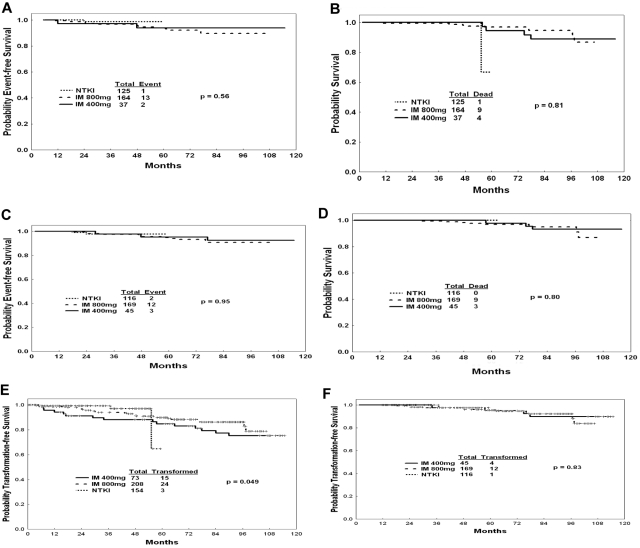

An important question is whether second-generation TKIs may offer a survival advantage over imatinib irrespective of cytogenetic response. The median time to a CCyR was 6 months with standard-dose imatinib versus 3 months with high-dose imatinib and 3 months with second-generation TKIs. Within each time point, patients with CCyR had similar survival probabilities regardless of the treatment used (Table 3; Figure 2A-D), suggesting that, in newly diagnosed CML, second-generation TKI may improve survival through improving the CCyR rate (ie, a better control of CML disease). Similarly, transformation-free survival was identical regardless of the treatment used, whether assessed on intent-to-treat analysis (Figure 2E) or among patients who achieved a 12-month CCyR (Figure 2F).

Figure 2.

Outcomes by CCyR and therapy. (A) EFS by therapy among patients with CCyR at 6 months. (B) OS by therapy among patients with CCyR at 6 months. (C) EFS by therapy among patients with CCyR at 12 months. (D) OS by therapy among patients with CCyR at 12 months. (E) Transformation-free survival by therapy (intent-to-treat analysis). (F) Transformation-free survival by therapy among patients with CCyR at 12 months.

Outcome by response at 12 months of therapy according to molecular response

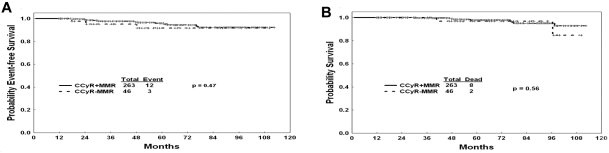

Because the achievement of MMR on imatinib therapy has been reported to be associated with improved probability of durable cytogenetic remission and EFS,24 we analyzed the long-term outcome of patients treated with TKI with a 12-month CCyR whether they have achieved an MMR or not. The achievement of MMR at 12 months of therapy did not confer any benefit in EFS or OS among patients with a CCyR. EFS of patients in CCyR at 12 months was not different whether or not they achieved an MMR (P = .47, Figure 3A). Similarly, OS was not different (P = .56, Figure 3B). In a second step, we did repeat the analysis at 3 and 6 months; similarly to 12 months, the achievement of an MMR at 3 and 6 months did not confer any benefit on EFS or OS among patients with a CCyR (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Outcomes by CCyR and NMR. (A) EFS by molecular response among patients with CCyR at 12 months. (B) OS by molecular response among patients with CCyR at 12 months.

Thereafter, we assessed, in univariate and multivariate analyses, factors associated with the achievement of a 12-month CCyR. In both analyses, therapy with second-generation TKI and high-dose imatinib remained the only predictive factors of a 12-month CCyR, with therapy with second-generation TKI being the most favorable factor (odds ratio = 15.5; P < .001) followed by high-dose imatinib as second most favorable factor (odds ratio = 4.5; P < .01).

Discussion

It has been clearly established that response is the most important prognostic factor for long-term outcome in CML.17–19 The depth and time of response obtained by patients with CML during TKI therapy are critical from a prognostic standpoint.17–19 Patients who achieved a CCyR at 12, 18, or 24 months in the IRIS study had improved progression-free survival compared with those who obtained only a partial cytogenetic response at each of those time points.3 Moreover, patients who do not achieve optimal response at 12 months of imatinib therapy had a higher risk of progression and poorer outcome compared with patients who achieved a 12-month CCyR, thus making the 12-month CCyR, the most relevant endpoint.17–19

Our study of homogeneous patients with early CML-CP treated with TKI has confirmed that second-generation TKI used in the frontline setting is highly efficacious and induced higher rates of CCyR early. In addition, our study has confirmed that an early achievement of CCyR remains a major surrogate endpoint that correlates with outcome, regardless of the therapy used.

In this study, second-generation TKIs induced a high rate of CCyR, with most responses occurring early. For example, by 6 months of therapy, > 95% of patients had already achieved a CCyR. These results compare favorably with the experience at our institution in similar patients treated with standard- or high-dose imatinib and are comparable with those achieved with nilotinib and dastinib in randomized phase 3 trials that have been recently published.15,16

It is unclear what the long-term implications of these earlier responses may be. A subanalysis of the IRIS study suggested that the time of achievement of CCyR does not impact the probability of EFS.25 For this particular subanalysis, only patients who achieved a CCyR were considered. Because achieving CCyR is known to favorably affect long-term outcome, such analysis is affected by a selection bias of patients who are already known to have a favorable outcome. However, it is important to consider that a patient who has not achieved CCyR at any given time may either improve and eventually achieve CCyR or may not improve and eventually experience progression. A recent report has suggested that, as more time evolves without achieving CCyR, the probability of eventually achieving CCyR decreases and the risk of progression increases.17

Our study has shown that the survival benefit in newly diagnosed CML treated with different TKIs is through improving cytogenetic responses. This is in line with previous studies comparing imatinib with IFN-α in early CML-CP18 and different from the results of imatinib mesylate versus other therapies in late CML-CP after IFN-α failure,26 which showed better survival with imatinib within each cytogenetic response category. In our analysis, therapy with second-generation TKI was found to be, in a multivariate analysis, the most favorable factor for the achievement of a 12-month CCyR (odds ratio = 15.5). A validation of these observations in independent cohorts is needed, particularly that only a small minority (5%) of our patients were in the Sokal high-risk category, compared with one-fourth of the patients enrolled in the randomized trials.

As in previous studies, the 12-month cytogenetic response to TKI therapy was predictive of prognosis.17–19 Patients who had achieved less than a CCyR had a worse prognosis (Figure 1C-D). However, among patients achieving a CCyR, the depth of molecular response at 12 months was so far not associated with significant differences in OS or EFS (Figure 3A-B). This is in line with our historical experience with imatinib in patients with newly diagnosed CML.18 Similarly, Marin et al have previously reported that the achievement of a MMR at 12 or 18 months of therapy with imatinib did not confer a benefit in 5-year progression-free survival or OS.19 This is in contrast to the recently updated IRIS results showing a significant difference in transformation-free survival by the degree of molecular response at 12 months with no impact on EFS or OS.24 This may be the result of differences in quantitative polymerase chain reaction methodologies, size of the study groups, and nature of the analysis (intention to treat vs selection of patients with favorable outcomes). Furthermore, our findings are in line with the German experience;27 Hehlmann et al have recently reported that the achievement of an MMR at 12 months, defined by a ratio of 0.1 or less on the international scale, confers a better progression-free survival and OS at 3 years compared with patients with a ratio of > 1% or no MMR, but they showed no difference compared with patients with a ratio between 0.1% and 1%, which closely correlates with CCyR.27

In conclusion, second-generation TKIs induce higher rates of CCyR that could translate into better outcome. The achievement of a 12-month CCyR remains the major surrogate of outcome improvement regardless of the TKI and regardless of the achievement of an MMR.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute (grant P01CA049639).

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: E.J. and J.C. designed the concept, analyzed the data, and wrote and approved the manuscript; H.K. designed the concept and wrote and approved the manuscript; S.O., S.F., A.Q.-C., G.G.-M., and F.R. provided materials and approved the manuscript; and J.S. and M.B.R. analyzed data and approved the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: E.J. received honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Novartis Pharmaceuticals; H.K. received research grants from Novartis Pharmaceuticals and Bristol-Myers Squibb; F.R. received research funding and honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb and honoraria from Novartis Pharmaceuticals; and J.C. received research grants from Novartis Pharmaceuticals and Bristol-Myers Squibb. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Elias Jabbour, Department of Leukemia, University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Blvd, Box 428, Houston, TX 77030; e-mail: ejabbour@mdanderson.org.

References

- 1.Jabbour E, Cortes JE, Giles FJ, O'Brien S, Kantarjian HM. Current and emerging treatment options in chronic myeloid leukemia. Cancer. 2007;109(11):2171–2181. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kantarjian H, Sawyers C, Hochhaus A, et al. Hematologic and cytogenetic responses to imatinib mesylate in chronic myelogenous leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(9):645–652. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Brien SG, Guilhot F, Larson RA, et al. Imatinib compared with interferon and low-dose cytarabine for newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(11):994–1004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deininger M, O'Brien SG, Guilhot F, et al. International randomized study of interferon vs. STI571 (IRIS) 8-year follow up: sustained survival and low risk for progression or events in patients with newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia in chronic phase (CML-CP) treated with imatinib [abstract]. Blood. 2009;114 Abstract 1126. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortes J, Talpaz M, O'Brien S, et al. Molecular responses in patients with chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase treated with imatinib mesylate. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(9):3425–3432. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kantarjian HM, Talpaz M, O'Brien S, et al. Survival benefit with imatinib mesylate versus interferon-α-based regimens in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2006;108(6):1835–1840. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talpaz M, Shah NP, Kantarjian H, et al. Dasatinib in imatinib-resistant Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemias. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2531–2541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kantarjian H, Giles F, Wunderle L, et al. Nilotinib in imatinib-resistant CML and Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(24):2542–2551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cortes J, Bruemmendorf T, Kantarjian H, et al. Efficacy and safety of bosutinib (SKI-606) among patients with chronic phase Ph+ chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML). Blood. 2007;110:733. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shah NP, Kantarjian HM, Kim DW, et al. Intermittent target inhibition with dasatinib 100 mg once daily preserves efficacy and improves tolerability in imatinib-resistant and -intolerant chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(19):3204–3212. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kantarjian HM, Giles F, Gattermann N, et al. Nilotinib (formerly AMN107), a highly selective BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is effective in patients with Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase following imatinib resistance and intolerance. Blood. 2007;110(10):3540–3546. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-080689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cortes JE, Jones D, O'Brien S, et al. Results of dasatinib therapy in patients with early chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):398–404. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cortes JE, Jones D, O'Brien S, et al. Nilotinib as front-line treatment for patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in early chronic phase. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):392–397. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rosti G, Palandri F, Castagnetti F, et al. Nilotinib for the frontline treatment of Ph(+) chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2009;114(24):4933–4938. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-232595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saglio G, Kim DW, Issaragrisil S, et al. Nilotinib versus imatinib for newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2251–2259. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kantarjian H, Shah NP, Hochhaus A, et al. Dasatinib versus imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(24):2260–2270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Quintas-Cardama A, Kantarjian H, Jones D, et al. Delayed achievement of cytogenetic and molecular response is associated with increased risk of progression among patients with chronic myeloid leukemia in early chronic phase receiving high-dose or standard-dose imatinib therapy. Blood. 2009;113(25):6315–6321. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-166694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kantarjian H, Talpaz M, O'Brien S, et al. Survival benefit with imatinib mesylate versus interferon-alpha-based regimens in newly diagnosed chronic-phase chronic myelogenous leukemia. Blood. 2006;108(6):1835–1840. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-004325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marin D, Milojkovic D, Olavarria E, et al. European LeukemiaNet criteria for failure or suboptimal response reliably identify patients with CML in early chronic phase treated with imatinib whose eventual outcome is poor. Blood. 2008;112(12):4437–4444. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kantarjian H, Talpaz M, O'Brien S, et al. Imatinib mesylate for Philadelphia chromosome-positive, chronic-phase myeloid leukemia after failure of interferon-alpha. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(7):2177–2187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan EL, Maier P. Non-parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1965;53:457–481. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cox DR. Regression models and life tables. J R Stat Soc. 1972;34:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes TP, Hochhaus A, Branford S, et al. Long-term prognostic significance of early molecular response to imatinib in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia: an analysis from the International Randomized Study of Interferon and STI571 (IRIS). Blood. 2010;116(19):3758–3765. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-273979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guilhot F, Larson R, O'Brien S. Time to complete cytogenetic response (CCyR) does not affect long-term outcomes for patients on imatinib therapy [abstract]. Blood. 2007;110:27. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kantarjian H, O'Brien S, Cortes J, et al. Survival advantage with imatinib mesylate therapy in chronic-phase chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML-CP) after IFN-alpha failure and in late CML-CP, comparison with historical controls. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:68–75. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hehlmann R, Lauseker M, Jung-Munkwitz S, et al. Tolerability-adapted imatinib 800 mg/d versus 400 mg/d plus interferon-alpha in newly diagnosed chronic myeloid leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(12):1634–1642. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.0598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]