Abstract

Background and Purpose

Ischemic stroke patients treated at Joint Commission Primary Stroke Center (JC-PSC) certified hospitals have better outcomes. Data reflecting the impact of JC-PSC status on outcomes after hemorrhagic stroke are limited. We determined whether 30-day mortality and readmission rates after hemorrhagic stroke differed for patients treated at JC-PSC certified versus non-certified hospitals.

Methods

The study included all fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries ≥65 years old with a primary discharge diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) or intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) in 2006. Covariate-adjusted logistic and Cox proportional hazards regression assessed the effect of care at a JC-PSC certified hospital on 30-day mortality and readmission.

Results

There were 2,305 SAH and 8,708 ICH discharges from JC-PSC certified hospitals and 3,892 SAH and 22,564 ICH discharges from non-certified hospitals. Unadjusted in-hospital mortality (SAH: 27.5% vs. 33.2%, p<0.0001; ICH: 27.9% vs. 29.6%, p=0.003) and 30-day mortality (SAH: 35.1% vs. 44.0%, p<0.0001; ICH: 39.8% vs. 42.4%, p<0.0001) were lower in JC-PSC hospitals, but 30-day readmission rates were similar (SAH: 17.0% vs. 17.0%, p=0.97; ICH: 16.0% vs. 15.5%; p=0.29). Risk-adjusted 30-day mortality was 34% lower (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.58–0.76) after SAH and 14% lower (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.80–0.92) after ICH for patients discharged from JC-PSC certified hospitals. There was no difference in 30-day risk-adjusted readmission rates for SAH or ICH based on JC-PSC status.

Conclusions

Patients treated at JC-PSC certified hospitals had lower risk-adjusted mortality rates for both SAH and ICH but similar 30-day readmission rates as compared with non-certified hospitals.

Keywords: hemorrhagic stroke, certified stroke center, outcomes

Introduction

The Joint Commission (JC) began certifying Primary Stroke Centers (PSCs) in November 2003 based on the recommendations from the Brain Attack Coalition and the American Stroke Association (ASA),1–4 and hospital certification to optimize cardiovascular disease and stroke quality of care and outcomes was the focus of an American Heart Association (AHA) Presidential Advisory statement.5 Studies assessing the impact of certification have generally focused on process of care measures for ischemic stroke patients.6–9 Only a few studies have evaluated the association between certification status and post-discharge outcomes, but they have been limited to patients hospitalized with ischemic stroke.10–13 Patients with hemorrhagic stroke (i.e., subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) and parenchymal intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH)) may also benefit from care at a JC-PSC certified hospital, but they have not been included in these studies. Differences in outcomes between JC-PSC certified and non-certified hospitals may reflect variation in hospital-based quality of care. Based on evidence derived from ischemic stroke populations, we hypothesized that hemorrhagic stroke patients treated at JC-PSC certified hospitals would have better short-term outcomes than patients treated at non-certified hospitals. To test this hypothesis, we compared the unadjusted and risk-adjusted 30-day mortality and readmission rates between elderly hemorrhagic stroke patients treated at JC-PSC certified hospitals and patients treated at non-certified hospitals.

Methods

Study sample

The study population included all fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare beneficiaries 65 years of age or older hospitalized with a primary discharge diagnosis of SAH (ICD-9-CM 430) or ICH (ICD-9-CM 431) identified based on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) from January 1, 2006 through December 31, 2006. Data were obtained from the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MEDPAR) files that included demographic information, primary and secondary discharge diagnosis codes, and procedure codes for each hospitalization for all FFS Medicare patients. Patients who were younger than 65 years of age were not included in the analysis because they do not represent typical Medicare patients. Patients who were discharged from non-acute care facilities, discharged within one day of admission, or who left the hospital against medical advice were excluded. We included patients with 12 months of continuous Medicare FFS enrollment before and one month after the hospitalization to obtain complete medical history, mortality, and readmission information. Patients transferred from one acute care hospital to another were required to have had a principal discharge diagnosis of a hemorrhagic stroke at both hospitals. We then linked hospitalizations into an episode of care and attributed the outcome to the initial admitting hospital. Hospitals were classified as to whether or not they had received JC-PSC certification. We obtained a list of all hospitals that had received JC-PSC certification from the start of the certification program in November 2003 through May 30, 2007 from the Joint Commission website in May 2007.1 Hospital provider numbers were used to identify hospitals with JC-PSC certification (N=315) for these analyses.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes included 30-day all-cause mortality, from the date of the index hemorrhagic stroke admission, and 30-day all-cause hospital readmission, defined as hospital readmission within 30 days of the index hospital discharge. Mortality data were determined using the Medicare Enrollment Database. The accuracy of ascertainment of vital status using these data resources is high for this age group.14 Patients who were transferred from the admitting hospital to another acute care hospital, and those who died during the index hospitalization, were excluded from the readmission analyses.

Covariates

Patient comorbidities were identified using the primary and 9 secondary codes from claims submitted in the 12 months prior to the index stroke hospitalization to avoid misclassifying pre-existing conditions as complications. A total of 29 independent candidate variables, including 2 demographic variables (age and sex), 8 cardiovascular and stroke history variables, and 19 other variables that identify additional comorbid conditions, were included from inpatient administrative claims data. Because there are more than 15,000 ICD-9-CM codes, we used the Hierarchical Condition Categories (HCC) to group clinically coherent categories.15 The HCC system was developed by physician and statistical consultants under a contract to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The HCC candidate variables for these analyses were derived from the secondary diagnosis and procedure codes from the index hospitalization and from hospitalizations over the previous 12 months (see online appendix). The majority of these variables were also included in the validated CMS acute myocardial infarction and heart failure 30-day all-cause hospital-specific mortality and readmission measures.16–19

Statistical analysis

Bivariate analyses were conducted to compare patient characteristics by JC-PSC certification status using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-squared statistics for categorical variables. Hierarchical random effects logistic models were used to assess the difference in odds of mortality between patients admitted to JC-PSC certified and non-certified hospitals while adjusting for patient clustering within hospitals. Random effects Cox proportional hazards models with censoring for deaths were used to compare readmission rates by JC-PSC certification status while adjusting for patient clustering within hospitals. Models were also adjusted for patient characteristics and medical history. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Hierarchical random effects logistic models and random effects Cox proportional hazards models were fitted using the "PROC Glimmix" and "PROC Nlmixed" procedures, respectively.

Results

A total of 6,197 SAH and 31,272 ICH stroke discharges were identified in 2006. Thirty-seven percent of SAH discharges (N=2,305) and 28% of ICH discharges (N=8,708) were from JC-PSC certified hospitals (Table 1). SAH and ICH patients treated at JC-PSC certified hospitals were younger; a higher percentage of women than men were discharged with ICH from JC-PSC certified hospitals (p<0.0001 for all comparisons).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics for Hemorrhagic Stroke Discharges from JC-PSC Certified and Non-Certified Hospitals

| SAH (ICD-9-CM 430) |

ICH (ICD-9-CM 431) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | JC-PSC Certified Hospitals |

Non- Certified Hospitals |

p-value | JC-PSC Certified Hospitals |

Non- Certified Hospitals |

p-value |

| Hospital discharges, total number | 2,305 | 3,892 | 8,708 | 22,564 | ||

| Age (yrs), mean ± SD | 75.6±7.4 | 77.3±8.0 | <.0001 | 78.5±7.5 | 79.5±7.7 | <0.0001 |

| Female, % | 67.4 | 66.9 | 0.7043 | 53.4 | 57.1 | <0.0001 |

| Comorbid conditions, % | ||||||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 10.8 | 9.4 | 0.0728 | 5.5 | 5.4 | 0.6329 |

| Hypertension | 54.4 | 56.7 | 0.0846 | 65.7 | 64.9 | 0.1906 |

| Diabetes | 14.2 | 16.2 | 0.0347 | 20.6 | 21.3 | 0.1977 |

| Renal failure | 9.0 | 9.6 | 0.445 | 10.7 | 10.9 | 0.7443 |

| COPD | 13.4 | 12.5 | 0.3244 | 12.1 | 12.6 | 0.2493 |

| Congestive heart failure | 11.9 | 13.1 | 0.1638 | 13.5 | 14.5 | 0.0207 |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 3.9 | 3.5 | 0.4236 | 1.9 | 1.6 | 0.0823 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 11.1 | 8.0 | <.0001 | 7.3 | 6.1 | <0.0001 |

| Cardiopulmonary-respiratory failure | 34.2 | 25.1 | <.0001 | 19.3 | 15.0 | <0.0001 |

| Pneumonia | 17.7 | 14.3 | 0.0004 | 12.5 | 11.8 | 0.1319 |

| Dementia | 35.2 | 27.5 | <.0001 | 21.5 | 22.3 | 0.1525 |

| In-hospital death, % | 27.5 | 33.2 | <.0001 | 27.9 | 29.6 | 0.0033 |

| Discharge to skilled nursing facility/intermediate care facility, % | 17.3 | 15.4 | 0.05 | 22.1 | 22.5 | 0.4207 |

| Length of stay (days), mean ± SD | 14.9±12.9 | 12.0±11.5 | <.0001 | 8.1±7.5 | 7.8±7.7 | 0.0447 |

Abbreviations: SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; ICD-9-CM, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; JC, Joint Commission; PSC, Primary Stroke Center; SD, standard deviation; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

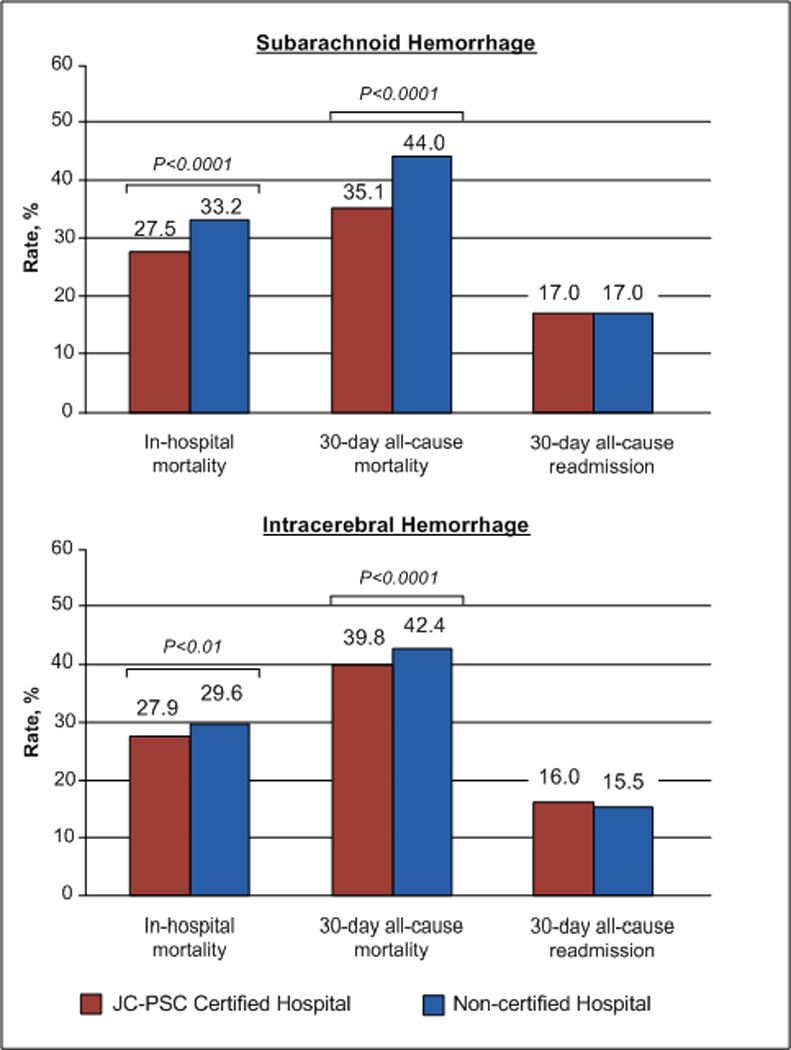

Unadjusted in-hospital mortality was lower in JC-PSC certified hospitals as compared with non-certified hospitals both for SAH (27.5% vs. 33.2%, p<0.0001) and ICH (27.9% vs. 29.6%, p=0.003; Figure 1). The unadjusted 30-day mortality outcomes were also lower for patients treated at JC-PSC certified hospitals than those treated at non-certified hospitals (SAH: 35.1% vs. 44.0%, p<0.0001; ICH: 39.8% vs. 42.4%, p<0.0001), but the unadjusted risk of 30-day hospital readmission was similar for patients treated at centers with and without certification (SAH: 17.0% vs. 17.0%, p=0.97; ICH: 16.0% vs. 15.5%, p=0.29).

Figure 1.

Unadjusted Outcomes by Joint Commission Primary Stroke Center Certification Status

Abbreviations: JC, Joint Commission; PSC, Primary Stroke Center

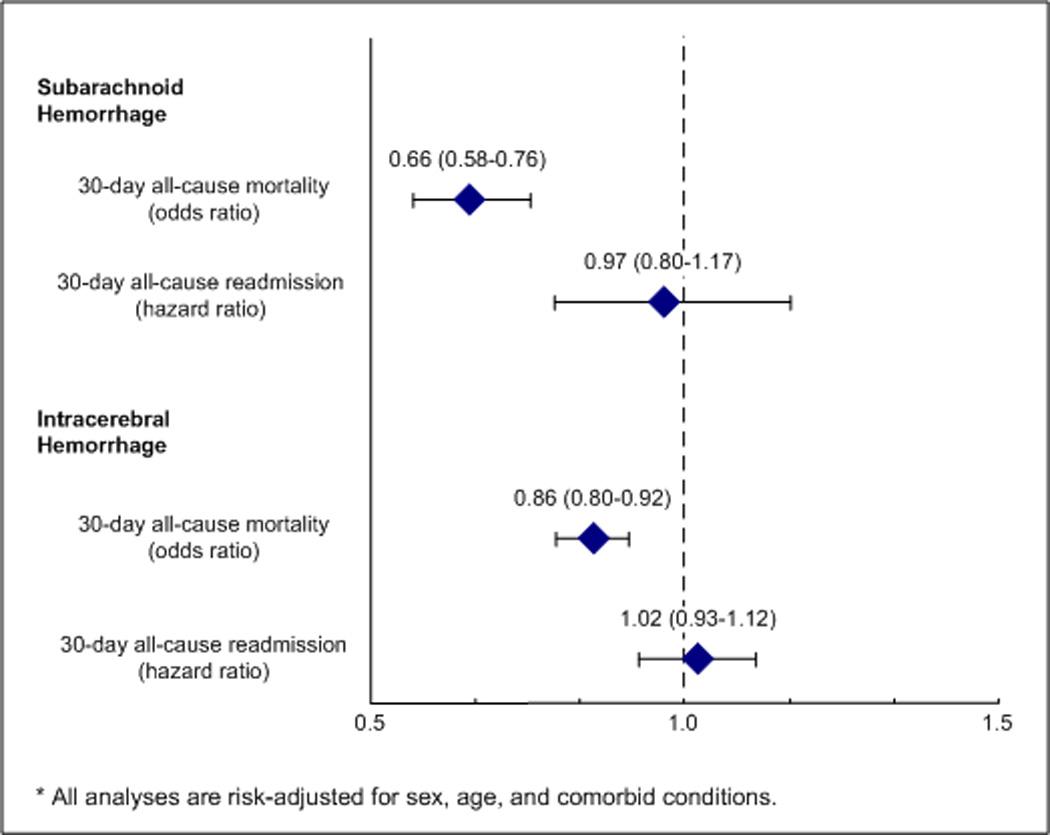

In risk-adjusted analyses (Figure 2), the relative risk of death within 30 days of hospital admission was 34% lower after SAH (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.58–0.76) and 14% lower after ICH (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.80–0.92) for patients discharged from JC-PSC certified hospitals compared with those discharged from non-certified hospitals. There was no difference in 30-day risk-adjusted readmission rates for SAH (hazard ratio [HR] 0.97, 95% CI 0.80–1.17) or ICH (HR 1.02, 95% CI 0.93–1.12) based on JC-PSC certification status.

Figure 2.

Risk-Adjusted 30-Day All-Cause Mortality and Hospital Readmission: JC-PSC vs. Non-Certified Hospitals

Discussion

In this study of elderly FFS Medicare beneficiaries, more than one-third of SAH and one-quarter of ICH patients were discharged from JC-PSC certified hospitals. Patients treated at JC-PSC certified hospitals had lower risk-adjusted 30-day mortality than patients treated at non-certified hospitals, but there was no difference in 30-day readmission rates between JC-PSC certified and non-certified hospitals.

Hospital certification is recognized as an important strategy for optimizing cardiovascular disease and stroke quality of care to help meet the goal of the AHA/ASA to improve the cardiovascular health of all Americans by 20% by the year 2020.5, 20 Certification programs such as the JC-PSC program, which is based on the recommendations of the Brain Attack Coalition and AHA/ASA, have the potential to set evidence-based standards and identify hospitals delivering appropriate, high-quality care to their stroke patients. Few studies have examined the association between stroke center certification and patient outcomes, and these have focused on ischemic stroke patients. A Finnish study reported that ischemic stroke patients treated in stroke centers had lower 1-year case-fatality and reduced institutional care compared with patients treated at general hospitals.12 A study in New York reported a modestly lower 30-day all-cause mortality for ischemic stroke patients treated at designated stroke centers as compared with patients treated at other hospitals.10 Neither study adjusted for hospital performance prior to certification.

Although JC-PSC certification primarily focuses on the care of ischemic stroke patients, many of the ischemic stroke care measures are also applicable to patients with hemorrhagic stroke, and Joint Commission surveyors review the records of patients with hemorrhagic stroke as part of their on-site visits. The effect seen in the current analyses for hemorrhagic patients may reflect this overlap and review, or indicate that JC-PSC certification is a marker of hospitals that are dedicated to giving high quality stroke care irrespective of stroke subtype.

The current analyses provide evidence that elderly hemorrhagic stroke patients cared for at JC-PSCs have lower 30-day mortality as compared to patients at non-certified hospitals, but it is unclear whether the certification itself led to these better outcomes or if the certification program identified hospitals that had already been following best practices. For example, a study of Medicare beneficiaries with ischemic stroke found hospitals that received certification within the first few years of the program had better patient outcomes well before the certification program began.11 A second study found substantial overlap of hospital-level outcomes after ischemic stroke for JC-PSC certified and non-certified hospitals.13 The former study found that JC-PSC certified hospitals were larger, more likely to be teaching hospitals, and were generally located in more populous areas than non-certified hospitals.11 Similarly, a study from Finland also reported that stroke centers were larger and treated more patients each year than general hospitals.12 Participation in quality improvement efforts and registries that focus on health care practices improve adherence with recommended therapies.21–24 Studies evaluating the impact of the AHA Get With the Guidelines-Stroke found that the duration of participation in the program was associated with better adherence to stroke performance measures for both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke patients.23–26 Participating hospitals with larger bed capacity, higher annual stroke volume, and teaching status had greater improvements. Because JC-PSC certified and non-certified hospitals systematically differ, and the former are more likely to participate in other stroke-related quality improvement programs, it may be challenging to establish a causal relationship between JC-PSC certification and improvement in patient outcomes.27

The present study has a number of limitations. The index hemorrhagic stroke cases and complications were ascertained using ICD-9-CM codes and were restricted to hospitalized events. Positive predictive values for selected primary discharge codes for SAH and ICH, however, are high,28, 29 and there is no reason to expect differences in data coding across institutions by JC-PSC certification status. Medicare inpatient data does not contain information on medication utilization or decisions to provide palliative care or to withdraw care; therefore, we were unable to determine whether potential differences in the receipt or termination of recommended therapies in hospitals influenced patient outcomes. Additional factors affecting hemorrhagic stroke outcomes, including stroke severity, are not reflected in administrative records.30 Future studies should include an assessment of stroke severity to adjust for potential differences in patient populations. Although studies show that the benefits of organized stroke care do not differ by age group or stroke severity,31 there may be variations in referral patterns to facilities, potentially leading to more severe patients being diverted to a JC-PSC. Because our analyses are limited to FFS Medicare beneficiaries 65 years or older, the results may not be applicable to those without FFS Medicare coverage or to stroke patients younger than age 65 years treated at these hospitals. Our results, however, do reflect the experiences of all elderly FFS SAH and ICH stroke patients hospitalized within the United States. Finally, our study focused on short-term mortality and readmission outcomes and could not consider other important dimensions of patient outcomes such as functional status or quality of life.

Elderly patients with SAH and ICH treated at JC-PSC certified hospitals had better short-term mortality outcomes than patients treated at non-certified hospitals, but there was no difference in 30-day hospital readmission rates. It is uncertain whether the certification itself led to improved outcomes or whether other factors, such as self-selection to become a JC-PSC, may play a role. Future studies examining the relationship of JC-PSC certification on outcomes should adjust for differences in patient outcomes that may have existed prior to certification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reviewed and approved the use of its data for this work; this approval is based on data use only and does not represent a Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services endorsement of or comment on the manuscript content. The project described was supported by Grant Number R01NS043322 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest Disclosures

None

References

- 1.List of Joint Commission Certified Primary Stroke Centers. [Accessed May 30 2007];The Joint Commission: Primary Stroke Centers. http://www.jointcommission.org/CertificationPrograms/PrimaryStrokeCenters/guide_table_contents.htm.

- 2.Alberts MJ, Hademenos G, Latchaw RE, Jagoda A, Marler JR, Mayberg MR, et al. Recommendations for the establishment of primary stroke centers. Brain Attack Coalition. JAMA. 2000;283:3102–3109. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.23.3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams R, Acker J, Alberts M, Andrews L, Atkinson R, Fenelon K, et al. Recommendations for improving the quality of care through stroke centers and systems: An examination of stroke center identification options: Multidisciplinary consensus recommendations from the Advisory Working Group on Stroke Center Identification Options of the American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2002;33:e1–e7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwamm LH, Pancioli A, Acker JE, 3rd, Goldstein LB, Zorowitz RD, Shephard TJ, et al. Recommendations for the establishment of stroke systems of care: recommendations from the American Stroke Association's Task Force on the Development of Stroke Systems. Stroke. 2005;36:690–703. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000158165.42884.4F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fonarow GC, Gregory T, Driskill M, Stewart MD, Beam C, Butler J, et al. Hospital certification for optimizing cardiovascular disease and stroke quality of care and outcomes. Circulation. 2010;122:2459–2469. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182011a81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gropen TI, Gagliano PJ, Blake CA, Sacco RL, Kwiatkowski T, Richmond NJ, et al. Quality improvement in acute stroke: the New York State Stroke Center Designation Project. Neurology. 2006;67:88–93. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223622.13641.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douglas VC, Tong DC, Gillum LA, Zhao S, Brass LM, Dostal J, et al. Do the Brain Attack Coalition's criteria for stroke centers improve care for ischemic stroke? Neurology. 2005;64:422–427. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000150903.38639.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lattimore SU, Chalela J, Davis L, DeGraba T, Ezzeddine M, Haymore J, et al. Impact of establishing a primary stroke center at a community hospital on the use of thrombolytic therapy: the NINDS Suburban Hospital Stroke Center experience. Stroke. 2003;34:e55–e57. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000073789.12120.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stradling D, Yu W, Langdorf ML, Tsai F, Kostanian V, Hasso AN, et al. Stroke care delivery before vs after JCAHO stroke center certification. Neurology. 2007;68:469–470. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252930.82140.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xian Y, Holloway RG, Chan PS, Noyes K, Shah MN, Ting HH, et al. Association between stroke center hospitalization for acute ischemic stroke and mortality. JAMA. 2011;305:373–380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lichtman JH, Allen NB, Wang Y, Watanabe E, Jones SB, Goldstein LB. Stroke patient outcomes in US hospitals before the start of the Joint Commission Primary Stroke Center certification program. Stroke. 2009;40:3574–3579. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.561472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meretoja A, Roine RO, Kaste M, Linna M, Roine S, Juntunen M, et al. Effectiveness of primary and comprehensive stroke centers: PERFECT stroke: a nationwide observational study from Finland. Stroke. 2010;41:1102–1107. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.577718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lichtman JH, Jones SB, Wang Y, Watanabe E, Leifheit-Limson E, Goldstein LB. 30-Day Outcomes among Medicare Beneficiaries Discharged from Hospitals with and without Joint Commission-Certified Primary Stroke Centers. Neurology. 2011 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821e54f3. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schisterman EF, Whitcomb BW. Use of the Social Security Administration Death Master File for ascertainment of mortality status. Popul Health Metr. 2004;2:2. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-2-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pope GC, Kautter J, Ellis RP, Ash AS, Ayanian JZ, Lezzoni LI, et al. Risk adjustment of Medicare capitation payments using the CMS-HCC model. Health Care Financ Rev. 2004;25:119–141. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keenan PS, Normand S-LT, Lin Z, Drye EE, Bhat KR, Ross JS, et al. An administrative claims measure suitable for profiling hospital performance on the basis of 30-day all-cause readmission rates among patients with heart failure. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2008;1:29–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.802686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krumholz HM, Merrill AR, Schone EM, Schreiner GC, Chen J, Bradley EH, et al. Patterns of hospital performance in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure 30-day mortality and readmission. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2009;2:407–413. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.883256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Mattera JA, Wang Y, Han LF, Ingber MJ, et al. An administrative claims model suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day mortality rates among patients with an acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2006;113:1683–1692. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.611186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krumholz HM, Wang Y, Mattera JA, Wang Y, Han LF, Ingber MJ, et al. An administrative claims model suitable for profiling hospital performance based on 30-day mortality rates among patients with heart failure. Circulation. 2006;113:1693–1701. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.611194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lloyd-Jones DM, Hong Y, Labarthe D, Mozaffarian D, Appel LJ, Van Horn L, et al. Defining and setting national goals for cardiovascular health promotion and disease reduction: the American Heart Association's strategic Impact Goal through 2020 and beyond. Circulation. 2010;121:586–613. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The impact of standardized stroke orders on adherence to best practices. Neurology. 2005;65:360–365. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000171706.68756.b7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hills NK, Johnston SC. Duration of hospital participation in a nationwide stroke registry is associated with improved quality of care. BMC Neurol. 2006;6:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-6-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaBresh KA, Reeves MJ, Frankel MR, Albright D, Schwamm LH. Hospital treatment of patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack using the "Get With The Guidelines" program. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:411–417. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwamm LH, Fonarow GC, Reeves MJ, Pan W, Frankel MR, Smith EE, et al. Get With the Guidelines-Stroke is associated with sustained improvement in care for patients hospitalized with acute stroke or transient ischemic attack. Circulation. 2009;119:107–115. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.783688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith EE, Hassan KA, Fang J, Selchen D, Kapral MK, Saposnik G. Do all ischemic stroke subtypes benefit from organized inpatient stroke care? Neurology. 2010;75:456–462. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181ebdd8d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith EE, Liang L, Hernandez A, Reeves MJ, Cannon CP, Fonarow GC, et al. Influence of stroke subtype on quality of care in the Get With The Guidelines-Stroke Program. Neurology. 2009;73:709–716. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b59a6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alberts MJ. Stroke centers: proof of concept and the concept of proof. Stroke. 2010;41:1100–1101. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.582148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tirschwell DL, Longstreth WT., Jr. Validating administrative data in stroke research. Stroke. 2002;33:2465–2470. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000032240.28636.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kokotailo RA, Hill MD. Coding of stroke and stroke risk factors using international classification of diseases, revisions 9 and 10. Stroke. 2005;36:1776–1781. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000174293.17959.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bederson JB, Connolly ES, Jr., Batjer HH, Dacey RG, Dion JE, Diringer MN, et al. Guidelines for the management of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: A statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the Stroke Council, American Heart Association. Stroke. 2009;40:994–1025. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.191395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saposnik G, Kapral MK, Coutts SB, Fang J, Demchuk AM, Hill MD. Do all age groups benefit from organized inpatient stroke care? Stroke. 2009;40:3321–3327. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.554907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.