Abstract

Peptide self-assembly has been shown to be a useful tool for the preparation of bioactive nanostructures, and recent work has demonstrated their potential as therapies for regenerative medicine. In principle, one route to make these nanostructures more biomimetic would be to incorporate in their molecular design the capacity for biological sensing. We report here on the use of a reversible enzymatic trigger to control the assembly and disassembly of peptide amphiphile (PA) nanostructures. The PA used in these studies contained a consensus substrate sequence specific to protein kinase A (PKA), a biological enzyme important for intracellular signaling that has also been shown to be an extracellular cancer biomarker. Upon treatment with PKA, this PA molecule becomes phosphorylated causing the high aspect-ratio filamentous PA nanostructures to disassemble. Treatment with an enzyme to cleave the phosphate group results in reformation of the filamentous nanostructures. We also show that disassembly in the presence of PKA allows the enzyme-triggered release of an encapsulated cancer drug. In addition, these drug-loaded nanostructures were found to induce preferential cytotoxicity in a cancer cell line that is known to secrete high levels of PKA. This ability to control nanostructure through an enzymatic switch could allow for the preparation of highly sophisticated and biomimetic materials that incorporate a biological sensing capability to enable therapeutic specificity.

Introduction

Over the past decade, several different bioactive materials have been developed based on self-assembling peptides.1 Precise control over amino acid sequence makes it possible to prepare peptide-based materials in which the basic nanoscale building blocks are fibers,2–4 ribbons and tapes,5 tubes,6 and helices,7 among others. Our group has developed a broad class of molecules known as peptide amphiphiles (PA) that can self-assemble into highly bioactive nanoscale filaments.8 These PAs incorporate a tunable peptide segment covalently attached to a fatty acid alkyl tail. The self-assembly of these molecules into nanoscale filaments is driven by hydrophobic collapse of this alkyl moiety as well as hydrogen bond formation within the peptide region into β-sheet structures.9, 10 The terminal peptide region often contains a bioactive epitope, which upon hydrophobic collapse and self-assembly becomes presented on the surface of the resulting filamentous nanostructures.11–13 PAs have been specifically designed as bioactive therapies for a number of regenerative medicine targets, including spinal cord injury, cartilage repair, bone regeneration, angiogenesis and cardiovascular disease.14–21 These PAs have also been functionalized with terminal cell-lysing peptides with the objective of developing cancer therapies.22 The nanostructures formed by PAs have a high degree of internal order23, 24 as well as extensive hydration in the peptide shell25 and molecular design provides control over the interfacial curvature and enables high aspect-ratio nanostructures with cylindrical or flat surfaces.26 However, most examples of PA nanostructures to date do not allow for dynamic control over these properties. One example to the contrary is the recent design of light-responsive PA molecules as a means for external control over PA nanostructure. In this work, cleavage by light of a 2-nitrobenzyl moiety resulted in a transition from quadruple helical bundles to cylindrical nanofibers in one molecule and a transition from spheres to nanofibers in another, though these transitions were not reversible.27, 28 The transition from sphere to nanofiber in the second example was concomitant with an increased capacity for cell signaling by cylindrical nanostructures compared to spherical assemblies. 28

An important biomimetic dimension for peptide-based materials would be the crafting of structures with capacity to respond to biological stimuli in order to sense changes in local environments and then deliver signals or therapeutic agents in a controlled fashion. Previous efforts to develop materials with a sensing capacity have explored the use of external stimuli such as pH, ionic strength, temperature, light, oxidation/reduction state, or the presence of small molecules, proteins or enzymes.29 In the context of biology, enzymatic switches could be especially relevant to achieve control over the self-assembly of peptide-based materials. Other amphiphilic self-assembling peptide-based materials have been developed that exploit the use of enzymes to control self-assembly, either through the creation or rupture of a covalent bond.30,31 Unlike the structure of PAs developed by the Stupp group containing a hydrophobic alkyl tail and β-sheet forming peptide domain, many of the self-assembling peptides with demonstrated enzymatic control are small molecule gelators composed of a hydrophobic aromatic moiety, such as fluorenyl, pyrenyl, or naphthyl groups covalently attached to a short oligopeptide.32 The choice of aromatic moiety enables hydrophobic as well as π-π interactions to drive the supramolecular assembly of these small molecule gelators.33 These systems are often designed with a phosphorylated serine or tyrosine residue in order to facilitate solubility of the precursor molecule and a phosphatase enzyme is then used to cleave this phosphate group, rendering the molecule less soluble and promoting hydrogelation.34–39 Molecules have also been prepared that attach solubilizing groups via an ester linkage and use esterases to induce hydrogelation via ester hydrolysis.40, 41 Others have demonstrated creative use of β-lactamase to remove a β-lactam conjugated to a peptide-based gelator.42 Similarly, proteases can be used to specifically cleave a solubilizing peptide or polymer domain.43 Most of these enzyme-mediated peptide assembly strategies are based on the cleavage of a bond to render the resulting gelator less soluble. Some interesting work has also been done with thermolysin, which through reverse hydrolysis creates a peptide bond in order to produce a more hydrophobic gelator and induce nanofiber self-assembly.44 This strategy utilizing thermolysin is also reversible which allows for thermodynamic control over the resulting self-assembled nanofiber, selecting for the most stable and defect-free assemblies.45 We report here on the first effort to create peptide amphiphile nanofibers with an enzyme-responsive nanostructure that could offer specific biological sensing capabilities.

Results and Discussion

We report here the design of a peptide amphiphile (PA 1) with its sequence (KRRASVAGK[C12]-NH2) containing the specific consensus substrate (RRXSO, X=any residue, O=hydrophobic) for protein kinase A (PKA),46 a ubiquitous kinase in intracellular signaling and metabolism that has also been demonstrated to be an extracellular cancer biomarker.47–50 This consensus substrate becomes phosphorylated at the serine position by PKA. When nanofibers of PA 1 are treated with PKA (Figure 1A), the serine residue indeed becomes phosphorylated resulting in the formation of PA 2. This reaction occurs quantitatively (Figure 1B and Figure S1) and has a reaction half-life on the order of minutes (Figure S2). Using a generic alkaline phosphatase (AP), the phosphate group on the serine can be removed recovering the original molecule, PA 1R. The reverse reactions also occurred quantitatively (Figure 1B). One interesting finding is that the serine in the PA, even though it is located in the middle of the peptide domain, is still accessible to enzymes, confirming the highly hydrated nature of PA nanostructures.25 The consensus sequence that was incorporated into PA 1 is specific to phosphorylation by PKA. A different kinase, protein kinase B (PKB), did not phosphorylate this serine residue of PA 1 (Figure S3). Additionally, when the location of the serine residue within this consensus sequence was shifted by one residue (PA 3, KRRSAVAGK[C12]-NH2) it was no longer phosphorylated by PKA (Figure S4). This type of phosphorylation/dephosphorylation switch is reminiscent of protein signaling in nature, where the phosphorylation of serine and tyrosine residues enables the transduction of biological signals.

Figure 1.

(A) Chemical structures and reaction scheme for the conversion of peptide amphiphile 1 (PA 1) into its phosphorylated form (PA 2) by protein kinase A and then its conversion back to the de-phosphorylated form (PA 1R) by alkaline phosphatase. (B) Analytical liquid chromatography trace showing the complete conversion of PA 1 to PA 2, as well as the conversion back to PA 1R.

We next wanted to detremine what effect, if any, this phosphorylation would have on PA nanostructure. Characterization of PA 1 using cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) revealed high aspect-ratio filamentous nanofibers prior to treatment with PKA (Figure 2A). These are typical of the supramolecular filaments observed for self-assembly of many other peptide amphiphiles. Upon treatment with PKA to phosphorylate the serine, these high aspect-ratio nanostructures disappear in cryo-TEM, with visible nanostructures absent throughout the film (Figure 2B). Subsequent treatment with AP to cleave the phosphate from the serine residue restored the nanofiber morphology (Figure 2C) and by cryo-TEM these filaments are indistinguishable from those seen for PA 1 prior to any enzyme treatment. Control experiments performed by adding PKB to a solution of PA 1 did not result in the disappearance of the cylindrical nanofibers (Figure S3). This is expected given the lack of phosphorylation in these samples. PA 3, with the serine residue shifted one position, self-assembled similarly into high aspect-ratio nanofibers but treatment of this PA with PKA, which did not phosphorylate the serine, also did not result in loss of its nanofiber morphology (Figure S4). The observations using cryo-TEM were corroborated by small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) curves (Figure 3). SAXS for solutions of PA 1 and PA 1R confirmed the presence of nanostructures, as their scattering profiles had a higher intensity compared to a solvent background. SAXS also confirmed that the morphology of the nanostructures formed by PA 1 and 1R are similar, evident by their nearly identical scattering profiles. On the other hand, PA 2 scattered similarly to the solvent, indicating the absence of any nanostructure in the solution. Background-subtracted SAXS data for PA 1 fit to a cylinder form factor gave a fiber radius of 2.54 nm and length on the order of microns (Figure S5). These dimensions are consistent with those expected for a cylindrical assembly of PA 1 based on the length of the extended molecule and a high degree of hydration in the peptide shell. Both SAXS and cryo-TEM allow us to sample a solution in situ, and when combined provide a complete profile of the presence and geometry of any nanostructures in the bulk solution. In this case, the combination of results from SAXS and cryo-TEM allows us to conclude that treatment of PA 1 with PKA results in a disaggregation of the PA, possibly into individual soluble PA molecules as depicted in the cartoon (Figure 4). Specifically, the lack of any scattering in PA 2 supports a complete absence of nanostructures, including spherical micelle-like aggregates that may be difficult to observe using cryo-TEM alone.

Figure 2.

Cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (Cryo-TEM) showing the filamentous nanostructure of (A) PA 1 which is phosphorylated to produce (B) PA 2 and results in a disappearance of the nanostructure. (C) Treatment with alkaline phosphatase to de-phosphorylate the molecule restores the filamentous nanostructure. Scale bars are 200 nm (A and C) and 500 nm (B).

Figure 3.

Small angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) showing the raw scattering profiles of PAs 1, 2, and 1R along with a solvent background.

Figure 4.

Cartoon depicting the disassembly of PA 1 upon treatment with protein kinase A and its reassembly following treatment with alkaline phosphatase.

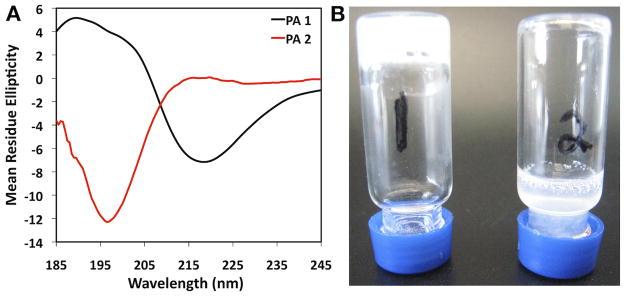

The formation of intermolecular β-sheet hydrogen bonds within their peptide domain has been demonstrated to be critical to the self-assembly of PA nanofibers.9, 10, 51 Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of PA 1 (Figure 5A) revealed the characteristic signature of β-sheet secondary structure, with a minimum at 218 nm. Following phosphorylation of the serine to form PA 2, theβ-sheet signature is lost, resulting in a random coil signature with a minimum at 196 nm. This loss of β-sheet could explain the disaggregation of the PA following phosphorylation. These findings are similar to observations after enzymatic phosphorylation of serine residues in recombinant engineered silk proteins, which have a high degree of β-sheet that contributes to their robust mechanical properties. In these silk proteins, phosphrylation of serine residues within β-sheet-rich domains prompted a transition in protein secondary structure from β-sheet to a random coil.52 Our CD data suggest that the addition of a phosphate group to the serine disrupts intermolecular β-sheet formation, resulting in disassembly of the supramolecular nanofibers. This is most probably due to effects of the presence of phosphate on PA molecular packing. At higher concentrations than those used for all other experiments and with the addition of phosphate counterions, PA 1 is able to form a self-supporting nanofiber gel. When this nanofiber gel was treated with PKA, this gel structure broke down and was no longer self-supporting (Figure 5B). The conversion to the phosphorylated form of the molecule (PA 2) when the PA was in the gelled state is not complete (Figure S6). Nevertheless, the level of phosphorylation observed was enough to compromise the mechanical integrity of the hydrogel. This is similar to work using a gel-forming naphthalene pentapeptide with a generic kinase/phosphatase switch on a terminal tyrosine residue in order to alter the assembly and gel formation of this small molecule.35 While similar in concept, the enzyme specificity of the system reported here could facilitate more precise biomimetic systems.

Figure 5.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy (A) for PA 1 (black) and PA 2 (red). Vial inversion of a hydrogel (B) formed from PA 1 without exposure to PKA (1) and with exposure to PKA (2).

The type of PA reported here forms nanostructures that respond to a specific enzymatic stimuli, as the PA contains a consensus substrate sequence rather than relying on generic enzymes, and is therefore a model system to detect a biological marker, in this case PKA. This type of enzyme specificity could facilitate precise sensing of particular biomarkers. PKA, the kinase used in our study, is ubiquitous within cells but is also known to be an extracellular biomarker for cancer.47–50 Therefore, the change in PA supramolecular morphology in the presence of PKA could in principle be used to prepare PA-based therapies that disassemble in the extracellular space of cancer cells or tumors to deliver a drug or other bioactive payload. Similar concepts reported previously include hydrophobic encapsulation of drugs within amphiphilic dendrimers with enzyme-cleavable domains53, encapsulation within nanocontainers with enzymatically sensitive caps54, and even covalently attaching drugs to other units using enzyme-sensitive linkages to prepare self-assembling pro-drugs.55, 56 The PA could have advantages over such approaches because of the specificity afforded by the incorporation of specific consensus substrate sequences in the peptide domain and because presentation of this domain on the fiber surface could double as a targeting epitope for nanostructure delivery. The PA could also prove advantageous given the longer circulation times of high aspect-ratio nanostructures,57 which may also be able to leverage the passive targeting benefits observed for nanocarriers in drug delivery including the enhanced permeation and retention (EPR) effect.58

Given the relevance of PKA secretion as a cancer biomarker,47–50 we evaluated in vitro a model for a potential therapy with these enzyme-responsive PA nanofibers. We demonstrated previously the possibility of encapsulating small hydrophobic molecules, such as pyrene, into the core of PA nanofibers.59 Thus, this PKA-responsive PA system could have potential as an enzyme-sensitive drug encapsulation tool. We selected the cancer drug doxorubicin (DOX), which is clinically used to treat cancer both as a free drug and encapsulated within liposomes.60,61 To test our concept of enzyme-responsive drug release, DOX was encapsulated within the PA nanostructures, which were then placed in a special dialysis chamber. The dialysate was monitored over time for DOX release from solutions of PA 1 in the presence and absence of PKA (Figure 6A). As shown, in the presence of PKA, the drug released much faster from solutions of PA 1 at a rate indistinguishable from a solution of the free drug. However, in the absence of PKA, the drug release is slowed significantly from PA 1. While some DOX does release in the absence of the enzyme, this is likely due to the solubility of DOX in the buffer along with the constant exchange of dialysate driving equilibrium toward the released species. When this is compared to the release of DOX from PA 3, which was not PKA-responsive, in the presence of PKA the release rate is similar to that for PA 1 in the absence of PKA. This data suggests enzyme-triggered DOX release from solutions of PA 1 in the presence of PKA. This enzyme-triggered release could be achieved with enzyme concentrations on the order of 0.1 nM; such nanomolar or subnanomolar sensitivity would be crucial for biomedical application. Though the exact concentration and activity of extracellular protein kinase A in tumors varies among patients, its ability to be quantifiably assayed in the total serum of human cancer patients49 suggests that the local concentration at the tumor is quite high and could provide a means to specifically target drug release from PA nanostructures at these regions of higher enzyme concentrations.

Figure 6.

(A) Release of DOX, measured by dialysate concentration, from solutions of free drug as well as DOX mixed with PA 1 and with PAs 1 and 3 in the presence of PKA. (B) Live(Green)/Dead(Red) cell viability imaging of three different cell types (MDA-MB-231, HUVECs, 3T3) after DOX or either PA 1 or PA 3 mixed with DOX was added to the conditioned media of a confluent cell monolayer.

One cancer cell that has been found to secrete large quantities of PKA into its media when in culture is the MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cell line.47 In order to evaluate the potential biosensing capabilities of our PKA-responsive PA nanostructures, we examined whether DOX-loaded PA nanostructures could induce preferential toxicity on these cancer cells (Figure 6B). As control cells that do not secrete appreciable PKA, an immortal but non-cancer cell line (3T3 mouse fibroblasts) and human primary cell known to be highly sensitive to culture conditions (human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs)) were used to evaluate the specificity of toxicity. After culturing cells for 24 hours to allow them to condition their media, DOX-loaded PAs 1 and 3 were added to confluent monolayers of the cells. PA 3, which is not responsive to PKA and does not result in a disaggregation of nanostructures, was used as a control. Following treatment of PA 1 with DOX, the MDA-MB-231 immortalized breast cancer cells were found to be completely dead. Meanwhile, a majority of these same cells were found to be viable when treated with an identical dose of PA 3 with DOX. It should be noted that PKA was not supplemented in these experiments, thus any PKA present in the conditioned media was produced and secreted by the cells. Treatment of HUVECs with PAs 1 and 3 containing DOX resulted in comparable viability for either treatment. However, even in these fragile primary HUVECs, viable cells remained following both treatments. The toxicity observed in these cells may be attributable to DOX that has leaked from PA nanostructures even without exposure to PKA, as was demonstrated to occur in the drug release studies. 3T3 fibroblasts, an immortalized but non-cancer cell line, showed little toxicity after treatment with either PA 1 or PA 3 with incorporated DOX. Therefore, of the cells evaluated, only the cancer cells known to secrete PKA into their media, the MDA-MB-231, were found to have differential toxicity when treated with DOX in a PKA-sensitive PA (PA 1) compared to DOX in a PA that was not PKA-responsive (PA 3).

Conclusions

We have reported here on enzyme-responsive nanostructures using the diverse class of peptide amphiphile molecules developed in our laboratory. Contrary to strategies previously reported for enzyme-responsive nanostructures, our model PA reported here contains a consensus substrate sequence for an enzyme that is known to be a specific cancer biomarker. The disaggregation observed as a result of enzymatic phosphorylation could thus be integrated to specifically target the release of drugs in the presence of cancer cells. Our results here indicate promise for such applications. The diversity of peptide sequences afforded by PA design could be harnessed to create a class of enzyme-responsive self-assembled PA nanofilaments such as we have demonstrated in this model system. These materials could go beyond enzymatic phosphorylation/dephosphorylation switches to also incorporate specific cleavage sites for enzymes and proteases. This could enable the preparation of biodegradable dynamic assemblies with a wide range of biological stimuli-sensing capabilities.

Materials and Methods

Peptide Synthesis and Purification

Peptide amphiphiles (PA) were synthesized by standard solid phase peptide synthetic methods using 9-fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc)-protected amino acids, MBHA Rink amide resin, and HBTU (2-(1H-benzotriazol-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate) from NovaBiochem. All solvents were ACS grade and were purchased from Mallinckrodt. Manual solid-phase peptide synthesis was performed at the 0.5 mmol scale under agitation from a wrist action shaker. Prior to each amino acid coupling, a solution of 2% DBU and 2% 4-methyl piperidine in DMF was used for Fmoc removal. The amino acid to be coupled was pre-activated with HBTU and DIEA (4:3.96:6) in DMF and added to the synthesis vessel containing the resin. The first amino acid added was a lysine residue with a 4-methyltrityl (Mtt) protecting group on the ε-amine. Following addition of this residue and prior to subsequent Fmoc removal, the Mtt protecting group was selectively removed by agitation in 4% TFA and 4% TIS in DCM. A lauric acid (C12) tail was then similarly pre-activated with HBTU and DIEA (4:3.96:6) in a 50/50 mixture of DMF/DCM and added to the resin. The remaining amino acids were subsequently added following the standard Fmoc protocol. After the final amino acid was added, the N-terminal Fmoc was removed. The PA was then cleaved from resin and side-chain protecting groups were removed through agitation in a mixture of TFA, water, and TIS (95:2.5:2.5). The cleaved product was isolated by precipitation in ethyl ether and dried on a fritted filter. The resulting product was dissolved in water containing 0.1% TFA and purified by reversed-phase HPLC using the Phenomenex Jupiter (10μm, 90A dC12 stationary phase) column and a linear gradient in water from 2% to 100% methanol, both containing 0.1% TFA. Methanol was removed by rotary evaporation and the remaining solution was lyophilized and stored as a lyophilized powder in sealed vials until use. The purity and accurate mass for each PA was verified using LC-MS on an electrospray ionization quadripole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Agilent).

Enzymatic Reactions and Verification

For the LC-MS, cryogenic-TEM, SAXS, and CD experiments the PA was dissolved at 1 mM in a reaction buffer of 50 mM Tris-HCl and 10 mM MgCl2 (pH=7.5). This was also supplemented with 1 mM ATP. cAMP-dependent Protein Kinase (PKA) catalytic subunit (New England Biolabs) was added to the mixture (10,000 U/mg PA). The reaction was incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes. Following this time, calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP, New England Biolabs) was added (60 U/mg PA) and the reaction was incubated for an additional 30 minutes at 37°C. For control experiments involving PA 3 with PKA or PA 1 with PKB, conditions were otherwise kept identical except for these two substitutions. Samples were collected at each stage for experiments. Reversed phase LC-MS was performed to confirm the success of each reaction using an Agilent electrospray ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer. The samples were run on a Phenomenex Jupiter (4μm, 90A dC12 stationary phase) column with a gradient from 0.1% formic acid in water to 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile that was inline with a diode array detector set to 220 nm and also with the ESI.

Rate Determination

The reaction was set up the same as that described previously with PKA and was incubated at 37°C. At specific timepoints throughout, a sample of the reaction was collected and immediately placed in a bath of boiling water for 10 minutes to heat-inactivate the enzyme. Samples were subsequently stored on ice until performing read-outs for ATP concentration with the use of a luminescence-based ATP concentration determination assay (Invitrogen). Controls for samples performed in the absence of PKA showed no decrease in ATP concentration over time.

Cryogenic TEM

Cryogenic TEM was performed on a JEOL 1230 microscope with an accelerating voltage of 100kV. A Vitrobot Mark IV equipped with controlled humidity and temperature was used for plunge-freezing samples. A small volume (5 μl) of sample was deposited on a lacey copper TEM grid (Electron Microscopy Sciences) and held in place with tweezers mounted to the Vitrobot. The specimen was blotted in 90–95% humidity and plunged into a liquid ethane reservoir cooled by liquid nitrogen. The vitrified samples were transferred into liquid nitrogen and inserted into a Gatan 626 cryo-holder through a cryo-transfer stage. Samples were imaged using a Hamamatsu ORCA CCD camera.

Small Angle X-Ray Scattering

SAXS measurements were performed using beam line 5ID-D, in the DuPont-Northwestern-Dow Collaborative Access team (DND-CAT) Synchrotron Research Center at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory. An energy of 15keV, corresponding to a wavelength l=0.83A−1, was selected using a double-crystal monochromator. The data were collected using a CCD detector (MAR) positioned 245 cm behind the sample. The scattering intensity was recorded in the interval 0.008< q < 0.25 A−1. The wave vector was defined as q = (4 π/λ) sin(θ/2), where θ is the scattering angle. The exposure times were between 2–8s depending on the sample. Solution samples were placed in 1.5mm quartz capillaries. The 2-D SAXS images were azimuthally averaged to produce one-dimensional profiles of intensity, I vs q, using the two-dimensional data reduction program FIT2D. The scattering of sample capillary with and without solvent were also collected and subtracted from the corresponding data. No attempt was made to convert the data to an absolute scale. Data analysis was based on fitting the scattering curve to an appropriate model by a least-squares method (see supplement).

Circular Dichroism

Circular dichroism was performed on a Jasco J-815 CD spectrophotometer complete with Peltier sample holder using a 1 mm cuvette. Samples were analyzed over a wavelength range of 260–180 nm with a step size of 0.5 nm and 3 total accumulations for each scan performed at 25°C. Background subtraction was performed on raw data (mdegs) which was then converted into units of mean residue ellipticity (θ × 10−3 (deg cm2 dmol−1 res−1).

Gel Studies

Gels were created by mixing equal volumes (150 μl) of a 20 mM solution of PA 1 with a solution prepared in phosphate buffered saline containing an additional 25 mM Na2HPO, 20 mM ATP and 20 mM MgCl2. This gel was prepared in a glass 1.5 ml HPLC autosampler vial. After one hour, 50 μl of PBS was added to one PA 1 gel, while 50 μl PKA (125,000U) was added to the other. Vials were sealed and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Vials were then inverted on a benchtop for 1 hour and images were captured. LC-MS was used to verify the extent of reaction for the gel treated with PKA (Figure S6).

Drug Release

PA 1 or 3 was dissolved at a concentration of 10 mM in hexafluoroisopropanol and doxorubicin was added at 5% w/w to the PA. Controls were prepared with only the drug in HFIP without of PA. The solutions were mixed and then sat for 30 minutes. They were frozen in liquid nitrogen and lyophilized on a high vacuum manifold while submerged in an ice bath. The samples were left on vacuum over night. They were then resuspended at 10 mM in water prior to experiments. Reaction conditions were the same as those previously stated and solutions of PA with DOX were diluted to 1 mM and PKA (20,000 U, 0.1 nM PKA) was added where appropriate. This resulted in a final drug concentration of 92 μM or 50 μg per chamber. The solutions (1 ml) were then placed on one side of a specialty-built dialysis chamber, with a 3500 MWCO membrane placed between this side and 1 ml of dyalysate (Tris reaction buffer with MgCl2 and ATP). The full volume of dialysate was collected at each timepoint and replaced with fresh solution. At the end of the experiment, all samples were placed into a 96-well microplate and concentration was determined based on fluorescence (Ex/Em= 470/585) using a microplate reader. Release is expressed as a cumulative percentage of the total amount added.

Cell Culture

MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells were cultured in high glucose DMEM containing 10% FBS, mouse 3T3 fibroblasts were cultured in low glucose DMEM containing 10% FBS, and human umbilical vein endothelial cells were cultured in standard endothelial growth media (Genlantis). Cells were plated in 96 well plates and grown for 24 hours until reaching confluency. To 100 μl of this 24-hour conditioned media was added 5 μl of a 10 mM PA solution containing 5% w/w doxorubicin for a final DOX concentration of 46 μM (2.5 μg/well). Following four hours, the media was removed and replaced with phosphate buffered saline. A live/dead assay (Invitrogen) was performed indicating live cells by green fluorescence of a Calcein AM dye and dead cells by red fluorescence of an ethidium homodimer DNA intercalating dye.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) award Nos. 2R01EB003806-06A2, 5RO1DE015920-05, and the Northwestern Center for Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence U54CA151880. MJW was funded by Northwestern NIH Regnerative Medicine Training Program, award No. 5T90-DA022881. We are grateful for the use of instrumentation in Keck Biophysics facility (CD), Biological Imaging Facility (cryo-TEM), and the Peptide Synthesis Core at the Institute for BioNanotechnology in Medicine (IBNAM) for synthesis, purification, and LC-MS. SAXS experiments were performed using the Advanced Photon Source DND-CAT beamline at Argonne National Laboratory. Use of the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. The authors are grateful to Dr. A. Cheetham, Dr. L. Palmer, Dr. Y. Velichko, Dr. J. Matson and R.H. Zha for fruitful conversation and technical assistance.

References

- 1.Webber MJ, Kessler JA, Stupp SI. J Intern Med. 2010;267:71–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gelain F, Horii A, Zhang S. Macromol Biosci. 2007;7:544–551. doi: 10.1002/mabi.200700033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Science. 2001;294:1684–1688. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:5133–5138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072699999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aggeli A, Nyrkova IA, Bell M, Harding R, Carrick L, McLeish TC, Semenov AN, Boden N. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:11857–11862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191250198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartgerink JD, Granja JR, Milligan RA, Ghadiri MR. J Am Chem Soc. 1996;118:43–50. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pashuck ET, Stupp SI. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8819–8821. doi: 10.1021/ja100613w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui H, Webber MJ, Stupp SI. Biopolymers. 2010;94:1–18. doi: 10.1002/bip.21328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pashuck ET, Cui H, Stupp SI. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6041–6046. doi: 10.1021/ja908560n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Velichko YS, Stupp SI, de la Cruz MO. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:2326–2334. doi: 10.1021/jp074420n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva GA, Czeisler C, Niece KL, Beniash E, Harrington DA, Kessler JA, Stupp SI. Science. 2004;303:1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1093783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Storrie H, Guler MO, Abu-Amara SN, Volberg T, Rao M, Geiger B, Stupp SI. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4608–4618. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guler MO, Hsu L, Soukasene S, Harrington DA, Hulvat JF, Stupp SI. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:1855–1863. doi: 10.1021/bm060161g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mata A, Geng YB, Henrikson KJ, Aparicio C, Stock SR, Satcher RL, Stupp SI. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6004–6012. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajangam K, Behanna HA, Hui MJ, Han X, Hulvat JF, Lomasney JW, Stupp SI. Nano Lett. 2006;6:2086–2090. doi: 10.1021/nl0613555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah RN, Shah NA, Del Rosario Lim MM, Hsieh C, Nuber G, Stupp SI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:3293–3298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906501107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tysseling-Mattiace VM, Sahni V, Niece KL, Birch D, Czeisler C, Fehlings MG, Stupp SI, Kessler JA. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3814–3823. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0143-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ghanaati S, Webber MJ, Unger RE, Orth C, Hulvat JF, Kiehna SE, Barbeck M, Rasic A, Stupp SI, Kirkpatrick CJ. Biomaterials. 2009;30:6202–6212. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webber MJ, Han X, Murthy SN, Rajangam K, Stupp SI, Lomasney JW. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2010;4:600–610. doi: 10.1002/term.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Webber MJ, Tongers J, Renault MA, Roncalli JG, Losordo DW, Stupp SI. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chow LW, Bitton R, Webber MJ, Carvajal D, Shull KR, Sharma AK, Stupp SI. Biomaterials. 2011;32:1574–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Standley SM, Toft DJ, Cheng H, Soukasene S, Chen J, Raja SM, Band V, Band H, Cryns VL, Stupp SI. Cancer Res. 2010;70:3020–3026. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang HZ, Guler MO, Stupp SI. Soft Matter. 2007;3:454–462. doi: 10.1039/b614426h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hsu L, Cvetanovich GL, Stupp SI. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2008;130:3892–3899. doi: 10.1021/ja076553s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tovar JD, Claussen RC, Stupp SI. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2005;127:7337–7345. doi: 10.1021/ja043764d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cui H, Muraoka T, Cheetham AG, Stupp SI. Nano Letters. 2009;9:945–951. doi: 10.1021/nl802813f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muraoka T, Cui H, Stupp SI. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2946–2947. doi: 10.1021/ja711213s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muraoka T, Koh CY, Cui H, Stupp SI. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2009;48:5946–5949. doi: 10.1002/anie.200901524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mart RJ, Osborne RD, Stevens MM, Ulijn RV. Soft Matter. 2006;2:822–835. doi: 10.1039/b607706d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao Y, Yang Z, Kuang Y, Ma ML, Li J, Zhao F, Xu B. Biopolymers. 2010;94:19–31. doi: 10.1002/bip.21321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams RJ, Mart RJ, Ulijn RV. Biopolymers. 2010;94:107–117. doi: 10.1002/bip.21346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang Z, Gu H, Zhang Y, Wang L, Xu B. Chem Commun (Camb) 2004:208–209. doi: 10.1039/b310574a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma M, Kuang Y, Gao Y, Zhang Y, Gao P, Xu B. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:2719–2728. doi: 10.1021/ja9088764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang ZM, Gu HW, Fu DG, Gao P, Lam JK, Xu B. Adv Mater. 2004;16:1440. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang Z, Liang G, Wang L, Xu B. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:3038–3043. doi: 10.1021/ja057412y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang ZM, Liang GL, Ma ML, Gao Y, Xu B. Small. 2007;3:558–562. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang Z, Liang G, Guo Z, Guo Z, Xu B. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2007;46:8216–8219. doi: 10.1002/anie.200701697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang ZM, Liang GL, Xu B. Soft Matter. 2007;3:515–520. doi: 10.1039/b700138j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao J, Wang HM, Wang L, Wang JY, Kong DL, Yang ZM. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2009;131:11286. doi: 10.1021/ja9042142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang ZM, Xu KM, Guo ZF, Guo ZH, Xu B. Adv Mater. 2007;19:3152. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Das AK, Collins R, Ulijn RV. Small. 2008;4:279–287. doi: 10.1002/smll.200700889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang ZM, Ho PL, Liang GL, Chow KH, Wang QG, Cao Y, Guo ZH, Xu B. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2007;129:266–267. doi: 10.1021/ja0675604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koga T, Kitamura K, Higashi N. Chem Commun. 2006:4897–4899. doi: 10.1039/b611679e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toledano S, Williams RJ, Jayawarna V, Ulijn RV. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2006;128:1070–1071. doi: 10.1021/ja056549l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams RJ, Smith AM, Collins R, Hodson N, Das AK, Ulijn RV. Nature Nanotechnology. 2009;4:19–24. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2008.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pearson RB, Kemp BE. Methods Enzymol. 1991;200:62–81. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)00127-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cho YS, Park YG, Lee YN, Kim MK, Bates S, Tan L, Cho-Chung YS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:835–840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nesterova M, Johnson N, Cheadle C, Cho-Chung YS. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1762:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nesterova MV, Johnson N, Cheadle C, Bates SE, Mani S, Stratakis CA, Khan IU, Gupta RK, Cho-Chung YS. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8971–8974. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang H, Li M, Lin W, Wang W, Zhang Z, Rayburn ER, Lu J, Chen D, Yue X, Shen F, Jiang F, He J, Wei W, Zeng X, Zhang R. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:789–795. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cui H, Muraoka T, Cheetham AG, Stupp SI. Nano Lett. 2009;9:945–951. doi: 10.1021/nl802813f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winkler S, Wilson D, Kaplan DL. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12739–12746. doi: 10.1021/bi001335w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Azagarsamy MA, Sokkalingam P, Thayumanavan S. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:14184–14185. doi: 10.1021/ja906162u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel K, Angelos S, Dichtel WR, Coskun A, Yang YW, Zink JI, Stoddart JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:2382–2383. doi: 10.1021/ja0772086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pedersen PJ, Adolph SK, Subramanian AK, Arouri A, Andresen TL, Mouritsen OG, Madsen R, Madsen MW, Peters GH, Clausen MH. J Med Chem. 2010;53:3782–3792. doi: 10.1021/jm100190c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vemula PK, Cruikshank GA, Karp JM, John G. Biomaterials. 2009;30:383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Geng Y, Dalhaimer P, Cai S, Tsai R, Tewari M, Minko T, Discher DE. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:249–255. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peer D, Karp JM, Hong S, Farokhzad OC, Margalit R, Langer R. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:751–760. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2007.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guler MO, Claussen RC, Stupp SI. Journal of Materials Chemistry. 2005;15:4507–4512. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leonard RCF, Williams S, Tulpule A, Levine AM, Oliveros S. Breast. 2009;18:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Perez AT, Domenech GH, Frankel C, Vogel CL. Cancer Investigation. 2002;20:22–29. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120014883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.