Background: We have recently described that Gαq acts as an adaptor protein that facilitates PKCζ-mediated activation of ERK5.

Results: Our results show that PKCζ is essential for Gq-dependent ERK5 activation in cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts.

Conclusion: This novel signaling axis plays a key role in cardiac hypertrophy programs.

Significance: The Gαq/PKCζ/ERK5 pathway would be active in such pathological settings, providing new therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Angiotensin II, Cardiac Hypertrophy, Heterotrimeric G Proteins, MAP Kinases (MAPKs), Protein Kinase C (PKC), ERK5, Gq, PKCzeta

Abstract

Gq-coupled G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) mediate the actions of a variety of messengers that are key regulators of cardiovascular function. Enhanced Gαq-mediated signaling plays an important role in cardiac hypertrophy and in the transition to heart failure. We have recently described that Gαq acts as an adaptor protein that facilitates PKCζ-mediated activation of ERK5 in epithelial cells. Because the ERK5 cascade is known to be involved in cardiac hypertrophy, we have investigated the potential relevance of this pathway in cardiovascular Gq-dependent signaling using both cultured cardiac cell types and chronic administration of angiotensin II in mice. We find that PKCζ is required for the activation of the ERK5 pathway by Gq-coupled GPCR in neonatal and adult murine cardiomyocyte cultures and in cardiac fibroblasts. Stimulation of ERK5 by angiotensin II is blocked upon pharmacological inhibition or siRNA-mediated silencing of PKCζ in primary cultures of cardiac cells and in neonatal cardiomyocytes isolated from PKCζ-deficient mice. Moreover, upon chronic challenge with angiotensin II, these mice fail to promote the changes in the ERK5 pathway, in gene expression patterns, and in hypertrophic markers observed in wild-type animals. Taken together, our results show that PKCζ is essential for Gq-dependent ERK5 activation in cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts and indicate a key cardiac physiological role for the Gαq/PKCζ/ERK5 signaling axis.

Introduction

G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR)4 signaling through Gq proteins and MAPK cascades is known to play an important role in cardiovascular function and disease (1–4). Enhanced angiotensin II, endothelin-1, and catecholamine (α1-adrenergic receptors) signaling correlate with pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiac overexpression of a constitutively active α1B-adrenergic receptors or of wild-type angiotensin AT1 receptor is sufficient to trigger this process (5, 6), as does chronic administration of angiotensin II to wild-type mice (7, 8). On the contrary, agents that block angiotensin synthesis prevent the development of pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy in animal models and in humans (9, 10). The direct involvement of Gαq-mediated signaling is further stressed by reports showing that cardiac-specific overexpression of Gαq in transgenic mice triggers cardiac in a similar manner to pressure overload and enhances expression of fetal genes, whereas the overexpression of a dominant-negative Gαq peptide in the heart renders mice resistant to pressure overload-triggered hypertrophy (4, 11, 12 and references therein).

Gαq stimulation can initiate a number of downstream signaling pathways. By coupling to its classic effector phospholipase Cβ, activated Gq proteins promote diacylglycerol and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate production, leading to the activation of conventional and novel protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms and to the mobilization of internal Ca2+, respectively (11, 12). This in turn leads to the activation of additional intracellular pathways relevant to hypertrophy such as the calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) or the calmodulin kinase II cascades (11–13).

However, Gαq can also activate other signaling pathways independently of phospholipase Cβ stimulation. Gαq triggers the RhoA cascade, also required for a Gq-induced hypertrophic response through a direct interaction with p63RhoGEF (14–17). More recently, we have reported a novel role for Gαq as a scaffold protein capable of recruiting both PKCζ and the kinase MEK5 into an active complex, leading to the activation of the ERK5 pathway in epithelial cells (18). ERK5 is a member of the MAPK family that is activated by the upstream MEK5 kinase in response to different growth factors and cellular stressors (19). Activation of Gαq is a potent inducer of MAPK signaling in cardiac myocytes. The complex role of ERK1/2, JNK, and p38 MAPK cascades in promoting compensated cardiac hypertrophy and/or transition to heart failure has been investigated extensively (1, 12). Additionally, an important cardiac role for ERK5 has been identified recently (20). Although genetic deletion of ERK5 or MEK5 has indicated a role for this pathway in angiogenesis, endothelial cell physiology, and cardiovascular development (21, 22), recent data also point to a role of ERK5 in cardiac hypertrophy and cardiomyocyte survival (23–25). Notably, the transcription factors MEF2A/2C, well known downstream targets of ERK5, promote cardiac hypertrophy in transgenic mice (26), whereas targeted deletion of this kinase attenuates the hypertrophic response mediated by MEF2 activation in vivo (25).

However, despite the important role of both Gq and ERK5 in cardiovascular function, the occurrence of a functional relationship between these pathways in cardiac cells had not been shown previously. In this report, we identify the atypical PKCζ as a key link underlying Gαq-coupled GPCR-mediated stimulation of the ERK5 cascade in cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts and show that this new signaling axis is relevant for angiotensin-induced hypertrophic pathways in vivo.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

The affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody Gαq/11 (C19) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). The rabbit polyclonal antibody that recognizes ERK5 and the monoclonal antibody against PKCζ (C24E6) were from Cell Signaling Technologies (Billerica, MA). The anti-phospho-ERK5 (phospho-Thr/phospho-Tyr218/220) polyclonal antibody was purchased from Invitrogen). Angiotensin II was obtained from Sigma, and the myristoylated PKCζ pseudosubstrate peptide (Myr-SIYRRGARRWRKL) from BIOSOURCE (Camarillo, CA). Pertussis toxin was purchased from Biomol Research Laboratories (Plymouth Meeting, PA). All other reagents were of the highest commercially available grades.

Cell Culture and Treatments

Primary cultures of neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts were prepared from C57BL/6J mice or PKCζ-deficient mice or wild-type animals (SV129J background) by dissociation of neonatal (1–2 days) hearts. After plating to remove fibroblasts for 2 h, cardiomyocytes were plated in M12 multiwell precoated with 0.02% gelatin (300,000 cells per well) and cultured in DMEM plus 10% serum for 48 h. Cardiomyocytes were cultured for 2 days before use, whereas cardiac fibroblasts were expanded and passed twice before the assay to remove contamination by endothelial cells. Both cell types were cultured in DMEM (D5648, Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% FBS.

In all cases, the desired cell type was stimulated with angiotensin II (100 nm) in serum-free medium, during the indicated time periods. The cells were serum-starved for 5–6 h before ligand addition to minimize basal kinase activity. Treatment with the PKCζ pseudosubstrate inhibitor (10 μm) was initiated 30 min before agonist stimulation. For the inactivation of Gi proteins, cells were pretreated with pertussis toxin (100 ng/ml) for 16 h. Isolation of cardiac myocytes was performed as described previously (27). Adult male C57BL6 mice or Wistar rats were heparinized (4 units/g) and anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg). The hearts were removed and mounted on a Langerdorff perfusion apparatus. The ascending aorta was cannulated, and a retrograde perfusion was set up. The hearts were perfused successively with the following oxygenated solutions at 36 °C: 1) standard nominally Ca2+-free Tyrode solution (3 min) and 2) standard nominally Ca2+-free Tyrode solution (15 min) containing type II collagenase. The hearts were removed from the Langerdorff apparatus, and after removal of atria, the ventricles were cut off and gently shaken for 3 min in a standard Tyrode solution containing 0.1 mm CaCl2 to disperse the isolated cells. The resulting cell suspensions were filtered through a 250-μm nylon mesh and centrifuged for 4 min at 20 × g. Finally, the cell pellets were stored in Tyrode solution (1 mm CaCl2) and stimulated with angiotensin II (100 nm) shortly after extraction.

PKCζ Knockdown

Primary neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes were reverse-transfected using siRNA-specific oligonucleotides for PKCζ (mouse PRKCZ, NM_008860, On-target PLUS SMARTpool L-040823-00-0005, sequences GAUCGACCAGUCCGAAUUU, CAAGGCCUCACACACGUCUUA, CAUCAAGUCUCAUGCCUUC, and GGGCAUGCCUUGUCCUGGA) were purchased from Dharmacon (Roche Applied Science, Palo Alto, CA). Scrambled oligonucleotides were purchased from Ambion to serve as a negative control. siRNAs were transfected using DharmaFECT 1 reagent (Dharmacon) to reach a final concentration of 50 nm. A PKCζ-specific antibody (Cell Signaling) was utilized to assess effective knockdown of the kinase by Western blot.

Determination of MAPK Stimulation

The activation state of ERK5 was measured by Western blot analysis of cell lysates by using specific anti-phospho-ERK5 (1:500) or anti-ERK5 (1:500) antibodies. In the latter case, the stimulation of ERK5 can be detected by the presence of a band with slower electrophoretic mobility that represents the active, phosphorylated form of the protein (28). Both approaches have been used by us (18) and by other laboratories (29–31) as a reliable method for determining ERK5 activation. To obtain cell lysates, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS buffer plus 1 mm sodium orthovanadate and subsequently solubilized in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 1% (w/v) Nonidet P-40, 0.25% (w/v) sodium deoxycholate, 1 mm EGTA, 1 mm NaF, supplemented with 1 mm sodium orthovanadate plus a mixture of protease inhibitors). Lysates were resolved by 6–10% SDS-PAGE and subjected to immunoblot analysis as described previously (32). Bands were quantified by laser scanner densitometry, and the amount of phospho-ERK5 protein was normalized to the amount of the total loaded protein (ERK5 or GAPDH/actin/α-tubulin), as assessed by the specific antibodies. Statistical analysis was performed using the two-tailed Student's t test, as indicated.

Chronic Angiotensin Treatment in Vivo

The generation of PKCζ knock-out mice (SV129J background) has been described previously (33). Littermate wild-type and PKCζ−/− male mice (32 weeks of age) were subjected to continuous infusion of angiotensin II (or PBS as a control) for 14 days, a well established model for the induction of cardiac hypertrophy (8, 34). Angiotensin II dissolved in PBS was continuously and subcutaneously infused at a rate of 432 μg/kg/day using Alzet osmotic minipumps (model 2002, Alza Corp., Mountain View, CA) implanted dorsally under isofluorane anesthesia as reported (34). Heart rate and electrocardiogram (ECG) components were measured using a non-invasive recording electrocardiogram method in conscious mice (ECGenieTM ECG Screening System (Mouse Specifics, Inc., Boston, MA)) at 14 days after pump implantation as reported (35). Before sacrifice, blood plasma samples were obtained to assess circulating levels of pro-ANP (1–98), which reflects chronic levels of ANP secretion (36, 37), by using an established immunoassay (proANP EIA, Alpco Diagnostics, Windham, NH). Finally, hearts from wild-type or knock-out mice were excised and cleaned of blood, the weight of the whole heart was measured and the ratio to body weight or tibia length was calculated. Mice were maintained under pathogen-free conditions, and all of the experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines of the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and Other Scientific Purposes (Directive 86/609/EEC) and with the authorization of the Bioethical Committee of the University Autónoma of Madrid (CEI-21-440).

Immunohistochemistry and Histological Analysis

For histological analysis, hearts from wild-type or PKCζ knock-out mice were fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections of 5 μm were processed for immunohistochemistry. To compare the expression of Ets-1 and activated MEF2C and MEK5 in wild-type versus knock-out mice, a high temperature antigen unmasking technique (10-min microwaving of slides in Tris-EDTA, pH 8.0, for 90 s) was carried out. Antigen retrieval was performed after deparaffinization to enhance staining. Sections were then incubated with 5% horse serum for 30 min, and then washed three times with sterile PBS (pH 7.5) prior to incubation with the appropriate primary antibodies at 1:50/1:100 dilutions. Biotin-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories and used at 1:4000 dilution. For all antibodies, signal was amplified using avidin peroxidase (ABC Elite Kit Vector) and visualized using diaminobenzidine as a substrate (DAB kit, Vector Laboratories). Finally, sections were stained with hematoxylin. Image analysis was performed with ImageJ 1.46a software (Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). Four images were acquired from randomly selected locations in each slide. Random RGB images were converted to 8-bit images for the quantification of the DAB signal to obtain the integrated density parameters (38, 39).

Quantitative Real-time PCR

Total RNA from hearts of PBS- or angiotensin-treated animals was extracted with using RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer's recommendations. The integrity of the RNA populations was tested in the Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) showing 28 S/18 S ratios above 1.7. Gene expression levels for Nppa, Col1α2, and Mapk7 were determined using quantitative real-time PCR. Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse-transcribed into cDNA by the Gene Ampkit (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). qRT-PCR reactions were performed in triplicates in a 10-μl final volume with the cDNA amount equivalent to 5 ng of total RNA, 250 nm of each primer, and 5 μl of Power Sybr Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, PN 4367659) using a CFX 384 Real-time system, C1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad). A melting curve was included at the end of the program to verify the specificity of the PCR product. PCR primer sequences were selected using Universal Probe Library (Roche Applied Science) (see supplemental Table S1). The expression values were normalized using the average of the housekeeping genes 18 S ribosomal RNA, hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase, and GAPDH.

Gene Expression Microarray Analysis

Total RNA was purified from mice hearts using RNeasy fibrous tissue mini kit, following the manufacturer's instructions (Qiagen). RNA was hybridized to Mouse Expression MOE 430 2.0 Affymetrix GeneChips, containing more than 45,000 probe sets covering the mouse transcriptome. CEL files obtained after biochip scanning were used to normalize gene expression values using RMA (40, 41). Log2 transformed values were mean centered (mean = 0; S.D. = 1). To compare different mouse models of heart hypertrophy, the series matrix files corresponding to the experiments GSE7781 (42), GSE5500 (43), GSE12337 (44), and GSE8771 were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) website and performed in the same Affymetrix GeneChip (version MOE430 2.0). After removing irrelevant experiments, log2 transformed values were also mean centered (mean = 0; S.D. = 1) independently. This transformation allowed the comparison of expression values from different data sets in a unique multi-experiment data set. Differential expression analysis between control and hypertrophic samples was done using a t test, and probe sets were selected if they displayed >1.8 fold change with p < 0.008. Using these thresholds, a total number of 1,536 probe sets were found to be differentially expressed, being 823 underexpressed in hypertrophy and 713 overexpressed. Hierarchical clustering of the samples performed from the selected probe sets was done using Pearson distance and average linkage. To assure a proper grouping, samples and genes were resampled 100× using bootstrapping. Gene expression microarray data generated has been submitted to the GEO database with the accession number GSE29145 and accomplishes MIAME guidelines.

Functional Analysis

We performed enrichment analysis of functions of the differentially expressed genes using the Gene Ontology (GO) database and the web tool database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) (45, 46). Briefly, probe set lists of either group I or group II genes in the differential expression analysis of hypertrophy performed were uploaded in DAVID, which computes enrichment in GO “biological processes.” The enriched functions or “terms” were ordered by statistical relevance, displaying only those functions with <0.05 FDR value of corrected p value. Protein interaction networks were obtained using the Pathway Studio software (Ariadne Genomics).

RESULTS

Angiotensin Gq-coupled Receptor Activates ERK5 in Cardiomyocytes and Cardiac Fibroblasts in PKCζ-dependent Manner

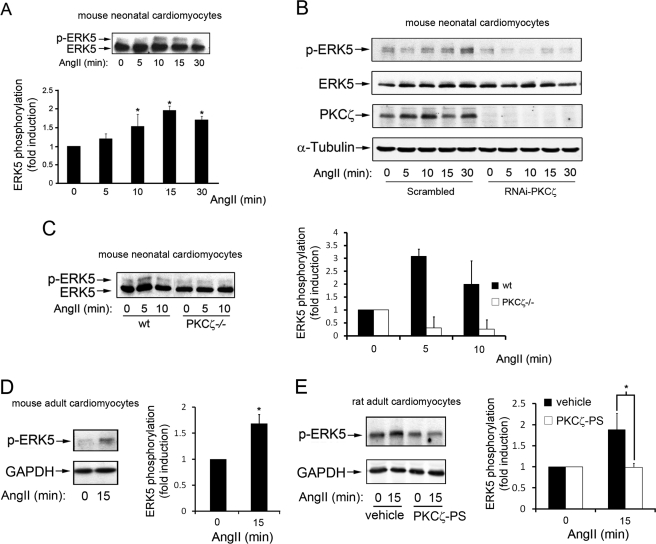

We have shown recently that activation of the m1-muscarinic Gq-coupled receptor in epithelial cells promoted the stimulation of the ERK5 pathway by biochemical routes not involving the classical Gαq effector phospholipase Cβ or cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases or EGF receptor transactivation (18). Because both Gq-coupled GPCR and ERK5 play an important role in the cardiovascular system function and dysfunction (see Introduction), we sought to determine whether a key messenger acting through Gq-coupled GPCR such as angiotensin II also triggered the ERK5 cascade in different cardiac cell types. Primary cultures of neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes were incubated with angiotensin II for different periods of time and endogenous ERK5 activation was assessed by immunoblot analysis using an ERK5 antibody that detects ERK5 stimulation by the appearance of a band of slower electrophoretic mobility, corresponding to the phosphorylated, stimulated kinase (Fig. 1A). A clear, time-dependent increase in endogenous ERK5 activation was detected in response to this agonist.

FIGURE 1.

Stimulation of Gq-coupled GPCR by angiotensin II promotes ERK5 activation in cardiomyocytes in a PKCζ-dependent way. A, neonatal mouse primary cardiomyocytes cell cultures were incubated with 100 nm angiotensin II (AngII) for the indicated times, and endogenous ERK5 activation determined with an ERK5 antibody that recognizes both the phosphorylated (upper band) and unphosphorylated (lower band) forms of ERK5 as detailed under “Experimental Procedures.” Data (mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments) were expressed as fold activation compared with the absence of agonist. *, p < 0.05, two-tailed t test when compared with basal conditions. B and C, angiotensin II-induced ERK5 activation is abrogated upon PKCζ down-regulation in neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes. B, primary cardiomyocytes were treated with scrambled or PKCζ-targeting siRNA oligonucleotides as detailed under “Experimental Procedures” and then challenged with 100 nm angiotensin for the indicated times. ERK5 activation was determined in cell lysates with a phospho-ERK5-specific antibody. Along with PKCζ expression, total ERK5 and α-tubulin levels were also determined as loading controls. C, primary cultures of neonatal mouse cardiomyocytes were obtained from WT or PKCζ-deficient (PKCζ−/−) mice as described under “Experimental Procedures” and challenged with 100 nm angiotensin for different time periods. ERK5 activation was monitored and quantified by laser densitometry and data (mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments, with activation in the absence of angiotensin taken as control condition) expressed as percentage of the phosphorylated kinase (p-ERK5) versus total ERK5. D and E, angiotensin triggers ERK5 stimulation in adult cardiomyocytes. Primary cultures of adult mouse (D) or rat (E) cardiomyocytes were isolated as detailed under “Experimental Procedures” and challenged with 100 nm angiotensin for 15 min. E, adult rat cardiomyocytes were preincubated with vehicle or a specific PKCζ pseudosubstrate (PS) inhibitor (10 μm). ERK5 activation was detected as described in B, and data were normalized using GAPDH as loading control and expressed as fold induction over basal conditions. Data are mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05, two-tailed t test when compared with basal (D) or control (E) conditions. Representative blots are shown in all panels.

Our previous results in epithelial cells indicated that a functional association between Gαq and PKCζ was essential for stimulation of the ERK5 pathway by Gαq-coupled GPCR agonists (18). To establish whether this novel pathway was also operating in cardiomyocytes, primary neonatal cell cultures were treated either with scrambled or PKCζ-targeting siRNA oligonucleotides. Interestingly, whereas a clear ERK5 activation (assessed using a specific phopho-ERK5 antibody) was noted in cardiomyocytes treated with scrambled siRNA (Fig. 1B), angiotensin-mediated endogenous ERK5 stimulation was not detected upon siRNA-induced PKCζ down-regulation. We also investigated ERK5 stimulation by angiotensin in cardiomyocytes isolated from PKCζ-deficient mice or wild-type littermates (SV129J background) (33). As in cardiomyocytes obtained from the C57BL/6J strain, angiotensin promoted a clear ERK5 activation in cells from wild-type, with an earlier peak of activation, whereas this response was absent in PKCζ−/− cardiomyocytes (Fig. 1C). Furthermore, we found that angiotensin-dependent ERK5 stimulation could also be observed in cardiomyocytes isolated from adult mouse (Fig. 1D) or rat (Fig. 1E) and that this process was blocked in the presence of a specific PKCζ inhibitor (the cell-permeable myristoylated PKCζ pseudosubstrate peptide (47, 48)) (Fig. 1E). Collectively, these data indicated that PKCζ is strictly required for Gq-mediated ERK5 stimulation in cardiomyocytes.

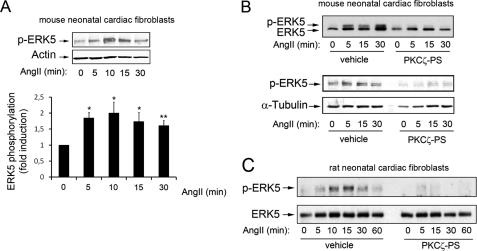

Interestingly, angiotensin II-mediated stimulation of endogenous ERK5 was also observed in cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 2A), with slight differences in the time course of activation. As we observed in epithelial cells for other Gq-coupled GPCRs (18), ERK5 activation by angiotensin II in cardiac fibroblasts was not affected in the presence of pertussis toxin (supplemental Fig. 1), thus indicating that this process does not involve paracrine transmodulation of Gi-coupled-GPCR. Moreover, in line with the data in cardiomyocytes, the pretreatment of primary neonatal mouse (Fig. 2B) or rat (Fig. 2C) cardiac fibroblasts, prior to agonist challenge, with the specific PKCζ pseudosubstrate inhibitor markedly decreased endogenous ERK5 phosphorylation in response to angiotensin II, thus suggesting that PKCζ is also required for Gq-mediated ERK5 activation in cardiac fibroblasts.

FIGURE 2.

PKCζ is required for angiotensin II-mediated stimulation of the ERK5 pathway in cardiac fibroblasts. A, neonatal mouse cardiac fibroblasts were challenged with angiotensin (AngII), and ERK5 stimulation was determined as described in Fig. 1B. Data (mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments) were normalized using actin as a loading control and expressed as fold induction compared with the absence of agonist. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01. B and C, mouse (B) or rat (C) cardiac fibroblasts were preincubated with vehicle or with a myristoylated PKCζ pseudosubstrate (PS) inhibitor (10 μm) as described under “Experimental Procedures” challenged with 100 nm angiotensin for the indicated times, and ERK5 activation was determined as described in A. Blots are representative of two to three experiments.

Role of Gαq/PKCζ Pathway in Angiotensin-mediated Heart Signaling and Gene Expression Patterns in Vivo

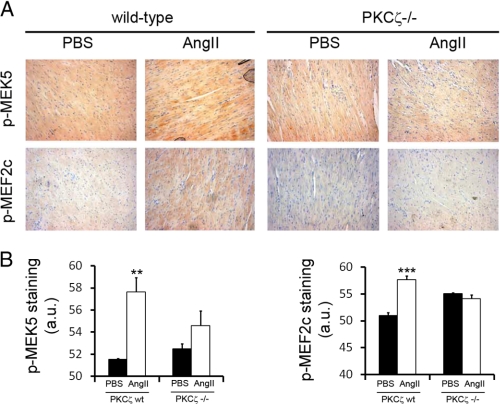

To assess the potential relevance of the Gαq/PKCζ pathway in cardiac cells in vivo, we subjected homozygous null mice (PKCζ−/−) and matched control littermates (wild-type) to chronic angiotensin II (or control vehicle) infusion for 14 days using osmotic mini-pumps. This is a classical, well established procedure to assess angiotensin effects in cardiac functions and to promote cardiac hypertrophy in mice models (34, 8). Immunohistological analysis of the hearts at the end of the chronic infusion period using phosphospecific antibodies showed that MEK5 (the upstream activator of ERK5) and MEF2C (a well established downstream target of ERK5) display a higher phosphorylation state upon angiotensin treatment in wild-type animals that is absent in PKCζ-deficient mice (Fig. 3). These data further indicate that PKCζ is an important mediator of ERK5 activation by Gαq-coupled GPCR in murine heart in vivo and support that the Gq/PKCζ/ERK5 pathway plays a relevant role in the response triggered by angiotensin.

FIGURE 3.

Activation of MEK5 and MEF-2C upon chronic angiotensin administration is inhibited in PKCζ-deficient mice. PKCζ-deficient mice (PKCζ−/−) and matched WT control littermates were subjected to chronic angiotensin II (AngII) infusion (or PBS, as a control vehicle) for 14 days using osmotic minipumps as detailed under “Experimental Procedures.” The activation status of MEK5 and MEF2C was assessed by immunohistochemistry using phosphospecific antibodies. Brown shading indicates positive DAB staining. Signal intensity was quantified as detailed under “Experimental Procedures,” and data plotted below represent the average of three independent experiments. **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001, two-tailed t test when compared with control with angiotensin II-treated wild-type mice. a.u., arbitrary units.

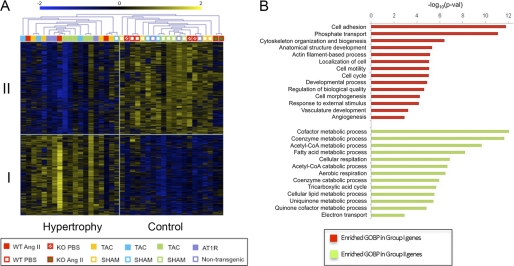

Enhanced signaling by Gαq-coupled GPCR often underlies the development of pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Therefore, we conducted a global microarray gene expression pattern analysis using total RNA isolated from wild-type or PKCζ-deficient mice treated with PBS or with chronic angiotensin II infusion and compared these data with the results published for different mouse models of heart hypertrophy (transverse aortic constriction or AT1 receptor transgenic mice), using the same Affymetrix GeneChip version. A test analysis was performed to find differences in gene expression patterns between experimentally assessed hypertrophic hearts and controls (see “Experimental Procedures”). A total number of 1,536 probe sets that did accomplish statistically significant criteria for differential expression were identified and listed as either overexpressed in hypertrophy (group I) or underexpressed (group II) compared with control animals (supplemental Tables S2 and S3). This information was used to group genes and samples using unsupervised hierarchical clustering (Fig. 4A). Our gene profiling analysis demonstrated that the expression patterns of animals developing hypertrophy as a consequence of transverse aortic constriction, angiotensin AT1 receptor overexpression, or angiotensin II infusion, were clearly separated from control treatments. Importantly, whereas our wild-type angiotensin II-treated mice consistently segregated with the “hypertrophic” expression profile group, the angiotensin II-treated PKCζ-deficient mice were included among the control group animals, together with PBS-treated animals. These results indicate that, upon angiotensin II treatment, PKCζ-deficient mice do not display a gene expression pattern characteristic of hypertrophic hearts.

FIGURE 4.

Differential gene expression patterns between control conditions and cardiac hypertrophy induced by different methods in mouse models. A, global gene expression patterns in WT or PKCζ-deficient (KO) mice chronically infused with angiotensin (AngII) or vehicle (PBS), were compared, as described under “Experimental Procedures,” to those reported in three different transverse aortic constriction (TAC) experiments with their corresponding controls (SHAM), and in one group of mice overexpressing the angiotensin AT1 receptor versus nontransgenic controls. Groups of genes either overexpressed (group I) or underexpressed (group II) in hypertrophic versus control conditions were identified. Samples were grouped using hierarchical clustering analysis. Expression values are shown in color coding as log2, mean centered per gene (mean = 0; S.D. = 1). B, enrichment analysis of functions overrepresented in differentially expressed genes. Shown are Gene Ontology biological processes (GOBP) terms that are significantly enriched in group I genes (red bars) and group II genes (green bars), as assessed by using the DAVID web tool. Significance is shown as −log10 of the p value.

Consistently, among group I genes, we found several whose products are considered hypertrophic markers, as ANP (Nppa) and brain nautriuretic peptide (Nppb), as well as type I α2 procollagen (Col1α2) and procollagen type IV α (col4α), that are overexpressed in cardiac fibrosis (49–51). These genes were not overexpressed in samples from angiotensin II-treated PKCζ-deficient mice or PBS-treated animals (supplemental Tables S2 and S3). Additionally, the biological functions of the differentially expressed genes were studied using DAVID software. Genes overexpressed in hypertrophy (group I) included functions related to cell cycle and cellular division, cellular adhesion, cytoskeleton organization, phosphate transport, and development (Fig. 4B), some of which can be related to cellular changes required for the induction of the hypertrophic phenotype. The underexpressed genes (group II) represented functions involved in metabolism, oxidative phosphorylation, cell respiration, and electron transport, which have been described to be down-regulated in hypertrophic hearts (50, 52).

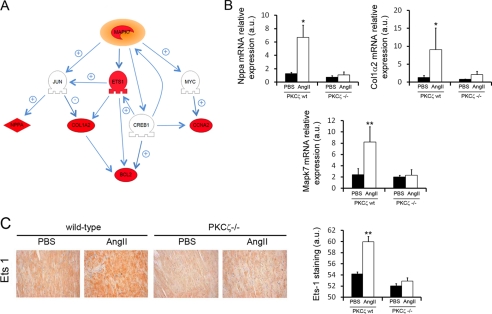

Microarray data were further analyzed using Pathway Studio (Ariadne Genomics) to identify and characterize possible targets whose alteration in gene expression could be related to the activation of the ERK5 signaling pathway. This analysis revealed that expression of ERK5 (Mapk7) itself and of its direct target ETS-1 (Ets-1) (53) was up-regulated in angiotensin-treated wild-type mice compared with angiotensin II-treated PKCζ-deficient mice or control mice (Fig. 5A). The same was true for gene products downstream the ETS-1 transcription factor (Col1a2, Bcl2). Consistently, immunohistological analyses of heart sections confirmed a marked increase in ETS-1 protein expression in angiotensin II-treated wild-type mice compared with angiotensin II-treated PKCζ−/− mice or PBS-treated animals (Fig. 5C). In this regard, it is interesting to point out that some genes regulated by other known downstream targets of ERK5 were also up-regulated. These are Ccna2 (directly controlled by c-Myc), Nppa, and Col1α2 (directly controlled by c-Jun) and Bcl2 (directly controlled by cAMP-responsive element-binding protein) (Fig. 5A, see also supplemental Tables S2 and S3). A quantitative RT-PCR analysis in cardiac tissue confirmed an increase in the mRNA expression of several of these relevant genes in angiotensin II-treated wild-type mice compared with angiotensin II-treated PKCζ−/− littermates or PBS-treated animals, such as the hypertrophic biomarker atrial natriuretic peptide (Nppa), collagen type I α2 (Col1α2) and mitogen-activated protein kinase 7 (Mapk7/Erk5) (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Alterations in gene expression related to the activation of the ERK5 signaling pathway differ in wild-type and PKCζ-deficient mice. A, microarray data were analyzed using Pathway Studio to identify changes in the expression of genes functionally related to ERK5. Several genes that are part of the ERK5 signaling network were found up-regulated (red) in angiotensin II (AngII)-treated mice compared with PBS-treated mice or angiotensin II-treated PKCζ-deficient animals. Genes whose expression does not change are shown in gray. The interaction map shows reported positive (+) and negative (−) relationships between related proteins. Mapk7 (ERK5), jun (c-jun), Ets1 (ETS1), myc (c-Myc), Nppa (ANP, atrial natriuretic factor), Nppb (BNP, brain type natriuretic peptide), Col1α2 (collagen type I, α2), Ccna2 (cyclin A2), Creb1 (CREB, cAMP-responsive element binding protein 1), Bcl2 (BCL2). B, quantitative RT-PCR analysis in heart tissue showing enhanced mRNA expression of Nppa, Col1α2 and Mapk7 in angiotensin II-treated wild-type mice compared with angiotensin II-treated PKCζ−/− mice and vehicle-treated animals. Data are mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01, two-tailed t test when compared with untreated animals. C, immunohistochemical analysis with a specific antibody shows the overexpression of ETS1 in heart sections from angiotensin II-treated wild-type but not in control and PKCζ-deficient animals. Staining intensity was quantified and plotted as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Data are mean ± S.E. of three independent experiments. **, p < 0.01, two-tailed t test when compared with untreated animals. a.u., arbitrary units.

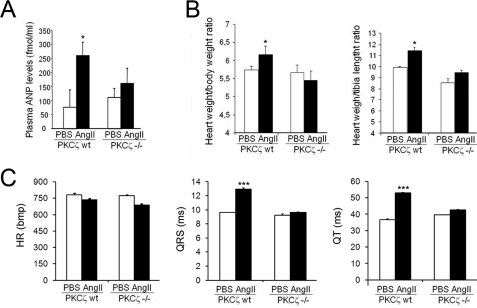

Overall, these data indicated the absence of an altered gene expression pattern related to cardiac hypertrophy in PKCζ-deficient mice upon angiotensin II treatment in contrast to that observed in wild-type mice, suggesting an important role for the Gαq/PKCζ axis in cardiac physiology. Consistent with these data, an initial analysis indicated that several markers that correlate with cardiac hypertrophy were altered upon angiotensin treatment in wild-type, but not in PKCζ-deficient mice. Plasmatic ANP levels were markedly enhanced upon angiotensin infusion in wild-type, but not in PKCζ−/− mice (Fig. 6A), in agreement with heart mRNA expression levels (Fig. 5B). Similarly, angiotensin II treatment significantly increased both heart weight/body weight or heart weight/tibial length ratios in wild-type mice compared to vehicle-infused animals. This change was not observed in PKCζ-deficient mice (Fig. 6B). In addition, an ECG analysis performed at the end of the chronic infusion period indicated that angiotensin II promoted a clear increase in the duration of the QRS and QT components in wild-type animals (what has been reported to correlate with left ventricular hypertrophy (54–56)) compared with vehicle-treated mice. However, no noticeable ECG changes were induced by angiotensin-II in PKCζ-deficient animals (Fig. 6C). Taken together, these data suggest that the absence of PKCζ impairs the induction of cardiac hypertrophy by the Gαq-coupled GPCR agonist angiotensin II.

FIGURE 6.

Analysis of hypertrophic markers in wild-type and PKCζ-deficient mice upon chronic angiotensin infusion. PKCζ-deficient mice (PKCζ−/−) and matched WT control littermates were subjected to chronic angiotensin II (AngII) infusion (or phosphate-buffered saline, PBS, as a control vehicle) for 14 days using osmotic minipumps as in previous figures. A, circulating plasmatic levels of the hypertrophic marker atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) were determined, as detailed under “Experimental Procedures”. Heart to body weight (B, left panel) or to tibial length ratios (B, right panel) were also calculated. C, in vivo electrocardiographic analysis indicates a significant increase in the duration of QRS and QT components (what has been shown to correlate with cardiac hypertrophy) in angiotensin versus PBS-treated wild-type animals that is not associated to a heart rate increase. PBS-treated PKCζ-deficient mice display parameters similar to PBS-treated WT mice, but angiotensin fails to promote an increase in QRS and QT components duration in this PKCζ knock-out model, as in wild-type animals. HR, heart rate; bpm, beats per min. Data in bar diagrams are expressed as mean ± S.E. of four animals in each group. *, p < 0.05; ***, p < 0.001 (two-tailed Student t test) compared with PBS-treated animals.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we show that PKCζ is required for the stimulation of the ERK5 pathway by the Gq-coupled GPCR angiotensin II receptor in cardiomyocytes and cardiac fibroblasts. Moreover, we suggest an important pathophysiological role for this Gαq/PKCζ/ERK5 axis in the triggering of signaling and gene expression pathways related to cardiac hypertrophy in response to angiotensin in vivo.

We observe that angiotensin II can promote ERK5 activation in both neonatal and adult murine cardiomyocytes and in neonatal cardiac fibroblasts, although the extent and kinetics of ERK5 stimulation can vary with the cell type or the mice strain. In agreement with our previous findings for other Gq-coupled GPCR in epithelial cells (18), this process does not appear to involve cross-talk with Gi-coupled signaling, as has been described for angiotensin II-mediated ERK1/2 activation in cardiac fibroblasts (57). On the other hand, pharmacological inhibition or siRNA-mediated silencing of PKCζ completely abrogated angiotensin-induced ERK5 activation in cardiomyocytes or cardiac fibroblasts, consistent with the lack of activation of this cascade in cardiomyocytes isolated from PKCζ-deficient mice. Overall, these data suggest that PKCζ is required for angiotensin-induced ERK5 stimulation in these cell types, most likely by mechanisms involving the scaffold role of Gαq and the formation of Gαq/PKCζ/MEK5 complexes as we have demonstrated previously (18).

Recent reports have indicated that angiotensin II is able to induce hypertrophy through activation of ERK5 in aortic smooth muscle cells (58, 59) and in rat neonatal cardiomyocytes (60), suggesting the functional involvement of PKC/PKD or PKCϵ, respectively. Although these differences might be explained by the different cell types used, the possibility exists that several PKC isoforms might be required for full activation of the ERK5 pathway by AT1 receptors.

The finding that PKCζ-deficient mice do not undergo the changes induced in wild-type animals upon chronic challenge with angiotensin II in the MEK5/ERK5/MEF2C pathway, in heart global gene expression and in hypertrophic markers suggest an important pathophysiological role for the Gαq/PKCζ axis. Although PKCζ was known to be present in cardiac cells and to translocate in response to Gq-coupled GPCR agonists (61), no cardiac-related phenotype had been reported in PKCζ-deficient mice in the absence of agonist challenge (33). It is worth noting that PKCζ deficiency does not alter the levels of the other PKC isotypes in different tissues (33), thus making unlikely that changes in such PKC isoforms (11) may underlie the observed effects on Gαq signaling. The heart hypertrophy parameters determined herein do not allow establishing whether they are the consequence of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, increased fibroblast proliferation/fibrosis, enhanced proliferation of other cardiac cell populations, or a combination of some of these processes. Because we report for the first time that ERK5 can also be activated by angiotensin II in neonatal cardiac fibroblasts, and given the emerging role of cardiac fibroblasts in cardiovascular function and dysfunction (62, 63), the contribution of different heart cell types to the observed hypertrophic phenotype clearly merits future investigation.

The induction of cardiac hypertrophy and eventually cardiac failure by agents acting through Gq-coupled GPCR appears to be a complex process involving changes in highly interconnected signaling pathways (including calcium homeostasis, PKC, MAPK, and PI3K/AKT cascades) triggered upon receptor stimulation (1, 11, 12, 64). The primary downstream actions of Gq-coupled GPCR have been tied to the activation of its canonical effector phospholipase Cβ, leading to the stimulation of conventional and novel PKC isoforms, calcium mobilization, and to the regulation of the calcineurin/NFAT cascade. In particular, the splicing variant phospholipase Cβ1 seems to be involved in the hypertrophic responses initiated by Gq-coupled α1-adrenergic receptors in cardiomyocytes (65). However, other reports have shown a lack of correlation between phospholipase Cβ activation and the cardiac hypertrophy phenotype induced in transgenic mouse lines expressing activated Gαq, suggesting a role for additional pathways in this process (66). In line with this notion, our data suggest that the functional link between Gαq and PKCζ is also necessary for the development of Gαq-induced cardiac hypertrophy programs.

Our data are consistent with the idea that the absence of PKCζ impairs the ability of Gq-coupled angiotensin receptors to promote cardiac hypertrophy programs by disrupting Gαq signaling to ERK5. The immunohistochemical data in hearts of PKCζ-deficient mice following chronic angiotensin II infusion, demonstrate a decrease in the phosphorylation/activation status of its upstream kinase MEK5, as well as of its well known downstream target, MEF2C, compared with wild-type littermates. Moreover, global gene expression analysis indicate that ERK5 (MapK7) itself and several direct (Ets-1) and indirect (NppA, Col1α2, Ccna2, Bcl2) ERK5 targets are up-regulated in angiotensin-treated wild-type animals but not in PKCζ-deficient mice. These results are in agreement with previous reports showing that angiotensin II infusion promotes ERK5 activation in mice myocardium (8), that overexpression of either upstream activators (MEK5) or downstream targets (MEF2A and C) of ERK5 induce cardiac hypertrophy in mice (23, 26), and that the activity of ERK5 is increased during left ventricular hypertrophy (24, 61), whereas targeted deletion of ERK5 attenuates the hypertrophic response in the heart (25). It is also worth noting that high levels of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl2 have been found in early stages of hypertrophy (67) and that arterial wall thickness, perivascular fibrosis, and cardiac hypertrophy induced by angiotensin II treatment are significantly reduced in Ets-1-deficient mice (68).

Although our data support the idea that the Gαq/PKCζ/ERK5 axis plays a relevant role in the development of cardiac hypertrophy signaling and gene expression programs triggered by angiotensin II, the possibility that PKCζ deficiency may alter additional Gαq signaling pathways downstream of PKCζ cannot be ruled out. PKCζ has been shown to increase atrial natriuretic factor in ventricular cardiomyocytes (69) and more recently to be involved in cardiac sarcomeric protein phosphorylation (70), which can be relevant during mechanical heart stress (71). Interestingly, PKCζ participates directly in the activation of MAPK and NFkB in several cell types (reviewed in Refs. 72 and 73), pathways widely known to be involved in cardiac hypertrophy (1, 12). The potential triggering of PKCζ downstream signaling pathways other than the ERK5 cascade upon Gq-coupled GPCR activation is being investigated actively in our laboratory.

In summary, we unveil that the novel Gαq/PKCζ signaling axis plays a key role in the development of cardiac hypertrophy programs in response to angiotensin. Because Gαq and PKCζ protein levels have been reported to increase in cardiomyocytes after volume overload-induced hypertrophy (74), it is tempting to suggest that such pathway would be particularly active in such pathological settings, providing new targets for therapeutic intervention.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr. Michel Herranz (Salamanca, Spain) for help with the ECG experiments.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovacion (SAF2008-00552), Fundación Ramón Areces, The Cardiovascular Network (RECAVA) of Instituto de Salud Carlos III (RD06-0014/0037), Comunidad de Madrid (S-SAL-0159-2006 to F. M.), and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI080461 to C. R.).

This article contains supplemental Tables S1–S3 and Fig. 1.

- GPCR

- G protein-coupled receptor

- ANP

- atrial natriuretic peptide.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dorn G. W., 2nd, Force T. (2005) Protein kinase cascades in the regulation of cardiac hypertrophy. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 527–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Harris D. M., Eckhart A. D., Koch W. J. (2006) Galphaq and its Aktions. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 40, 589–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang Y. (2007) Mitogen-activated protein kinases in heart development and diseases. Circulation 116, 1413–1423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rohini A., Agrawal N., Koyani C. N., Singh R. (2010) Molecular targets and regulators of cardiac hypertrophy. Pharmacol Res. 61, 269–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hein L., Stevens M. E., Barsh G. S., Pratt R. E., Kobilka B. K., Dzau V. J. (1997) Overexpression of angiotensin AT1 receptor transgene in the mouse myocardium produces a lethal phenotype associated with myocyte hyperplasia and heart block. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 6391–6396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Paradis P., Dali-Youcef N., Paradis F. W., Thibault G., Nemer M. (2000) Overexpression of angiotensin II type I receptor in cardiomyocytes induces cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 931–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bueno O. F., Wilkins B. J., Tymitz K. M., Glascock B. J., Kimball T. F., Lorenz J. N., Molkentin J. D. (2002) Impaired cardiac hypertrophic response in calcineurin Aβ-deficient mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 4586–4591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ikeda Y., Aihara K., Sato T., Akaike M., Yoshizumi M., Suzaki Y., Izawa Y., Fujimura M., Hashizume S., Kato M., Yagi S., Tamaki T., Kawano H., Matsumoto T., Azuma H., Kato S. (2005) Androgen receptor gene knockout male mice exhibit impaired cardiac growth and exacerbation of angiotensin II-induced cardiac fibrosis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 29661–29666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhu Y. C., Zhu Y. Z., Gohlke P., Stauss H. M., Unger T. (1997) Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonism on cardiac parameters in left ventricular hypertrophy. Am. J. Cardiol. 80, 110A–117A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hunyady L., Catt K. J. (2006) Pleiotropic AT1 receptor signaling pathways mediating physiological and pathogenic actions of angiotensin II. Mol. Endocrinol. 20, 953–970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liggett S. B. (2006) Cardiac 7-transmembrane-spanning domain receptor portfolios: Diversify, diversify, diversify. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 875–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heineke J., Molkentin J. D. (2006) Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signaling pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 589–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mishra S., Ling H., Grimm M., Zhang T., Bers D. M., Brown J. H. (2010) Cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure development through Gq and CaM kinase II signaling. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 56, 598–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chikumi H., Vázquez-Prado J., Servitja J. M., Miyazaki H., Gutkind J. S. (2002) Potent activation of RhoA by Gαq and Gq-coupled receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 27130–27134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lutz S., Freichel-Blomquist A., Yang Y., Rümenapp U., Jakobs K. H., Schmidt M., Wieland T. (2005) The guanine nucleotide exchange factor p63RhoGEF, a specific link between Gq/11-coupled receptor signaling and RhoA. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 11134–11139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lutz S., Shankaranarayanan A., Coco C., Ridilla M., Nance M. R., Vettel C., Baltus D., Evelyn C. R., Neubig R. R., Wieland T., Tesmer J. J. (2007) Structure of Gαq-p63RhoGEF-RhoA complex reveals a pathway for the activation of RhoA by GPCRs. Science 318, 1923–1927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rojas R. J., Yohe M. E., Gershburg S., Kawano T., Kozasa T., Sondek J. (2007) Gαq directly activates p63RhoGEF and Trio via a conserved extension of the Dbl homology-associated pleckstrin homology domain. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 29201–29210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. García-Hoz C., Sánchez-Fernández G., Díaz-Meco M. T., Moscat J., Mayor F., Ribas C. (2010) Gα(q) acts as an adaptor protein in protein kinase C ζ (PKCζ)-mediated ERK5 activation by G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR). J. Biol. Chem. 285, 13480–13489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Obara Y., Nakahata N. (2010) The signaling pathway leading to extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 (ERK5) activation via G-proteins and ERK5-dependent neurotrophic effects. Mol. Pharmacol. 77, 10–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang X., Tournier C. (2006) Regulation of cellular functions by the ERK5 signaling pathway. Cell Signal. 18, 753–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nishimoto S., Nishida E. (2006) MAPK signaling: ERK5 versus ERK1/2. EMBO Rep. 7, 782–786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Roberts O. L., Holmes K., Müller J., Cross D. A., Cross M. J. (2009) ERK5 and the regulation of endothelial cell function. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 37, 1254–1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nicol R. L., Frey N., Pearson G., Cobb M., Richardson J., Olson E. N. (2001) Activated MEK5 induces serial assembly of sarcomeres and eccentric cardiac hypertrophy. EMBO J. 20, 2757–2767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kacimi R., Gerdes A. M. (2003) Alterations in G protein and MAP kinase signaling pathways during cardiac remodeling in hypertension and heart failure. Hypertension 41, 968–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kimura T. E., Jin J., Zi M., Prehar S., Liu W., Oceandy D., Abe J., Neyses L., Weston A. H., Cartwright E. J., Wang X. (2010) Targeted deletion of the extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase 5 attenuates hypertrophic response and promotes pressure overload-induced apoptosis in the heart. Circ. Res. 106, 961–970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xu J., Gong N. L., Bodi I., Aronow B. J., Backx P. H., Molkentin J. D. (2006) Myocyte enhancer factors 2A and 2C induce dilated cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 9152–9162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fernández-Velasco M., Goren N., Benito G., Blanco-Rivero J., Boscá L., Delgado C. (2003) Regional distribution of hyperpolarization-activated current (If) and hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated channel mRNA expression in ventricular cells from control and hypertrophied rat hearts. J. Physiol. 553, 395–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xu B. E., Stippec S., Lenertz L., Lee B. H., Zhang W., Lee Y. K., Cobb M. H. (2004) WNK1 activates ERK5 by an MEKK2/3-dependent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 7826–7831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nakamura K., Johnson G. L. (2010) Activity assays for extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5. Methods Mol. Biol. 661, 91–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Díaz-Rodríguez E., Pandiella A. (2010) Multisite phosphorylation of Erk5 in mitosis. J. Cell Sci. 123, 3146–3156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ohnesorge N., Viemann D., Schmidt N., Czymai T., Spiering D., Schmolke M., Ludwig S., Roth J., Goebeler M., Schmidt M. (2010) Erk5 activation elicits a vasoprotective endothelial phenotype via induction of Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4). J. Biol. Chem. 285, 26199–26210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Elorza A., Sarnago S., Mayor F., Jr. (2000) Agonist-dependent modulation of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 by mitogen-activated protein kinases. Mol. Pharmacol. 57, 778–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Leitges M., Sanz L., Martin P., Duran A., Braun U., García J. F., Camacho F., Diaz-Meco M. T., Rennert P. D., Moscat J. (2001) Targeted disruption of the zetaPKC gene results in the impairment of the NF-κB pathway. Mol. Cell 8, 771–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Braz J. C., Bueno O. F., Liang Q., Wilkins B. J., Dai Y. S., Parsons S., Braunwart J., Glascock B. J., Klevitsky R., Kimball T. F., Hewett T. E., Molkentin J. D. (2003) Targeted inhibition of p38 MAPK promotes hypertrophic cardiomyopathy through up-regulation of calcineurin-NFAT signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 111, 1475–1486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chu V., Otero J. M., Lopez O., Morgan J. P., Amende I., Hampton T. G. (2001) Method for non-invasively recording electrocardiograms in conscious mice. BMC Physiol. 1, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Missbichler A., Hawa G., Schmal N., Woloszczuk W. (2001) Sandwich ELISA for proANP 1–98 facilitates investigation of left ventricular dysfunction. Eur. J. Med. Res. 6, 105–111 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Molhoek S. G., Bax J. J., van Erven L., Bootsma M., Steendijk P., Lentjes E., Boersma E., van der Laarse A., van der Wall E. E., Schalij M. J. (2004) Atrial and brain natriuretic peptides as markers of response to resynchronization therapy. Heart 90, 97–98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang Q., Symes A. J., Kane C. A., Freeman A., Nariculam J., Munson P., Thrasivoulou C., Masters J. R., Ahmed A. (2010) A novel role for Wnt/Ca2+ signaling in actin cytoskeleton remodeling and cell motility in prostate cancer. PloS one 5, e10456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brey E. M., Lalani Z., Johnston C., Wong M., McIntire L. V., Duke P. J., Patrick C. W., Jr. (2003) Automated selection of DAB-labeled tissue for immunohistochemical quantification. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 51, 575–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bolstad B. M., Irizarry R. A., Astrand M., Speed T. P. (2003) A comparison of normalization methods for high density oligonucleotide array data based on variance and bias. Bioinformatics 19, 185–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Irizarry R. A., Hobbs B., Collin F., Beazer-Barclay Y. D., Antonellis K. J., Scherf U., Speed T. P. (2003) Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4, 249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kuba K., Zhang L., Imai Y., Arab S., Chen M., Maekawa Y., Leschnik M., Leibbrandt A., Markovic M., Makovic M., Schwaighofer J., Beetz N., Musialek R., Neely G. G., Komnenovic V., Kolm U., Metzler B., Ricci R., Hara H., Meixner A., Nghiem M., Chen X., Dawood F., Wong K. M., Sarao R., Cukerman E., Kimura A., Hein L., Thalhammer J., Liu P. P., Penninger J. M. (2007) Impaired heart contractility in Apelin gene-deficient mice associated with aging and pressure overload. Circ. Res. 101, e32–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bisping E., Ikeda S., Kong S. W., Tarnavski O., Bodyak N., McMullen J. R., Rajagopal S., Son J. K., Ma Q., Springer Z., Kang P. M., Izumo S., Pu W. T. (2006) Gata4 is required for maintenance of postnatal cardiac function and protection from pressure overload-induced heart failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 14471–14476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Smeets P. J., de Vogel-van den Bosch H. M., Willemsen P. H., Stassen A. P., Ayoubi T., van der Vusse G. J., van Bilsen M. (2008) Transcriptomic analysis of PPARα-dependent alterations during cardiac hypertrophy. Physiol. Genomics 36, 15–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hosack D. A., Dennis G., Jr., Sherman B. T., Lane H. C., Lempicki R. A. (2003) Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with EASE. Genome Biol. 4, R70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dennis G., Jr., Sherman B. T., Hosack D. A., Yang J., Gao W., Lane H. C., Lempicki R. A. (2003) DAVID: Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery. Genome Biol. 4, P3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Parmentier J. H., Smelcer P., Pavicevic Z., Basic E., Idrizovic A., Estes A., Malik K. U. (2003) PKCζ mediates norepinephrine-induced phospholipase D activation and cell proliferation in VSMC. Hypertension 41, 794–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Godeny M. D., Sayeski P. P. (2006) ANG II-induced cell proliferation is dually mediated by c-Src/Yes/Fyn-regulated ERK1/2 activation in the cytoplasm and PKCζ-controlled ERK1/2 activity within the nucleus. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 291, C1297–1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Liao Y., Asakura M., Takashima S., Ogai A., Asano Y., Shintani Y., Minamino T., Asanuma H., Sanada S., Kim J., Kitamura S., Tomoike H., Hori M., Kitakaze M. (2004) Celiprolol, a vasodilatory β-blocker, inhibits pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and prevents the transition to heart failure via nitric oxide-dependent mechanisms in mice. Circulation 110, 692–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mirotsou M., Dzau V. J., Pratt R. E., Weinberg E. O. (2006) Physiological genomics of cardiac disease: Quantitative relationships between gene expression and left ventricular hypertrophy. Physiol. Genomics 27, 86–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Fielitz J., Kim M. S., Shelton J. M., Qi X., Hill J. A., Richardson J. A., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E. N. (2008) Requirement of protein kinase D1 for pathological cardiac remodeling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3059–3063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Larkin J. E., Frank B. C., Gaspard R. M., Duka I., Gavras H., Quackenbush J. (2004) Cardiac transcriptional response to acute and chronic angiotensin II treatments. Physiol. Genomics 18, 152–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hayashi M., Lee J. D. (2004) Role of the BMK1/ERK5 signaling pathway: Lessons from knock-out mice. J. Mol. Med. 82, 800–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dhingra R., Ho Nam B., Benjamin E. J., Wang T. J., Larson M. G., D'Agostino R. B., Sr., Levy D., Vasan R. S. (2005) Cross-sectional relations of electrocardiographic QRS duration to left ventricular dimensions: The Framingham Heart Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 45, 685–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Salles G., Leocádio S., Bloch K., Nogueira A. R., Muxfeldt E. (2005) Combined QT interval and voltage criteria improve left ventricular hypertrophy detection in resistant hypertension. Hypertension 46, 1207–1212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Domenighetti A. A., Boixel C., Cefai D., Abriel H., Pedrazzini T. (2007) Chronic angiotensin II stimulation in the heart produces an acquired long QT syndrome associated with IK1 potassium current down-regulation. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 42, 63–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yamazaki T., Yazaki Y. (1999) Role of tissue angiotensin II in myocardial remodeling induced by mechanical stress. J. Hum. Hypertens. 13, S43–47; discussion S49–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Geng J., Zhao Z., Kang W., Wang W., Liu G., Sun Y., Zhang Y., Ge Z. (2009) Hypertrophic response to angiotensin II is mediated by protein kinase D-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 pathway in human aortic smooth muscle cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 388, 517–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhao Z., Geng J., Ge Z., Wang W., Zhang Y., Kang W. (2009) Activation of ERK5 in angiotensin II-induced hypertrophy of human aortic smooth muscle cells. Mol. Cell Biochem. 322, 171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhao Z., Wang W., Geng J., Wang L., Su G., Zhang Y., Ge Z., Kang W. (2010) Protein kinase C epsilon-dependent extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation involved in cardiomyocyte hypertrophy with angiotensin II stimulation. J. Cell. Biochem. 109, 653–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Takeishi Y., Huang Q., Abe J., Glassman M., Che W., Lee J. D., Kawakatsu H., Lawrence E. G., Hoit B. D., Berk B. C., Walsh R. A. (2001) Src and multiple MAP kinase activation in cardiac hypertrophy and congestive heart failure under chronic pressure overload: Comparison with acute mechanical stretch. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 33, 1637–1648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Takeda N., Manabe I., Uchino Y., Eguchi K., Matsumoto S., Nishimura S., Shindo T., Sano M., Otsu K., Snider P., Conway S. J., Nagai R. (2010) Cardiac fibroblasts are essential for the adaptive response of the murine heart to pressure overload. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 254–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kakkar R., Lee R. T. (2010) Intramyocardial fibroblast myocyte communication. Circ. Res. 106, 47–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Harris D. M., Cohn H. I., Pesant S., Eckhart A. D. (2008) Clin. Sci. 115, 79–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Filtz T. M., Grubb D. R., McLeod-Dryden T. J., Luo J., Woodcock E. A. (2009) Gq-initiated cardiomyocyte hypertrophy is mediated by phospholipase Cβ1b. FASEB J. 23, 3564–3570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Mende U., Semsarian C., Martins D. C., Kagen A., Duffy C., Schoen F. J., Neer E. J. (2001) Dilated cardiomyopathy in two transgenic mouse lines expressing activated G protein α(q): Lack of correlation between phospholipase C activation and the phenotype. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 33, 1477–1491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ecarnot-Laubriet A., Assem M., Poirson-Bichat F., Moisant M., Bernard C., Lecour S., Solary E., Rochette L., Teyssier J. R. (2002) Stage-dependent activation of cell cycle and apoptosis mechanisms in the right ventricle by pressure overload. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1586, 233–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zhan Y., Brown C., Maynard E., Anshelevich A., Ni W., Ho I. C., Oettgen P. (2005) Ets-1 is a critical regulator of Ang II-mediated vascular inflammation and remodeling. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 2508–2516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Decock J. B., Gillespie-Brown J., Parker P. J., Sugden P. H., Fuller S. J. (1994) Classical, novel, and atypical isoforms of PKC stimulate ANF- and TRE/AP-1-regulated-promoter activity in ventricular cardiomyocytes. FEBS Lett. 356, 275–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Wu S. C., Solaro R. J. (2007) Protein kinase C ζ. A novel regulator of both phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of cardiac sarcomeric proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 30691–30698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Borges L., Bigarella C. L., Baratti M. O., Crosara-Alberto D. P., Joazeiro P. P., Franchini K. G., Costa F. F., Saad S. T. (2008) ARHGAP21 associates with FAK and PKCζ and is redistributed after cardiac pressure overload. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 374, 641–646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Moscat J., Rennert P., Diaz-Meco M. T. (2006) PKCζ at the crossroad of NF-κB and Jak1/Stat6 signaling pathways. Cell. Death Differ. 13, 702–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Moscat J., Diaz-Meco M. T. (2011) Fine-tuning NF-κB: New openings for PKC-ζ. Nat. Immunol. 12, 12–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sentex E., Wang X., Liu X., Lukas A., Dhalla N. S. (2006) Expression of protein kinase C isoforms in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure due to volume overload. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 84, 227–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.