Abstract

Gene expression profiling was performed on 97 cases of infant ALL from Children's Oncology Group Trial P9407. Statistical modeling of an outcome predictor revealed 3 genes highly predictive of event-free survival (EFS), beyond age and MLL status: FLT3, IRX2, and TACC2. Low FLT3 expression was found in a group of infants with excellent outcome (n = 11; 5-year EFS of 100%), whereas differential expression of IRX2 and TACC2 partitioned the remaining infants into 2 groups with significantly different survivals (5-year EFS of 16% vs 64%; P < .001). When infants with MLL-AFF1 were analyzed separately, a 7-gene classifier was developed that split them into 2 distinct groups with significantly different outcomes (5-year EFS of 20% vs 65%; P < .001). In this classifier, elevated expression of NEGR1 was associated with better EFS, whereas IRX2, EPS8, and TPD52 expression were correlated with worse outcome. This classifier also predicted EFS in an independent infant ALL cohort from the Interfant-99 trial. When evaluating expression profiles as a continuous variable relative to patient age, we further identified striking differences in profiles in infants less than or equal to 90 days of age and those more than 90 days of age. These age-related patterns suggest different mechanisms of leukemogenesis and may underlie the differential outcomes historically seen in these age groups.

Introduction

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) arising in infants less than 1 year of age is an aggressive disease, with more than 50% of cases relapsing within 5 years of diagnosis.1,2 Established prognostic factors include patient age and the presence of genomic rearrangements of the Mixed Lineage Leukemia (MLL) gene on chromosome 11q23, with children less than or equal to 90 days of age at diagnosis and those with MLL rearrangements experiencing a particularly poor outcome.1,2 MLL rearrangements occur in nearly 80% of infants with ALL, resulting predominantly in translocations of MLL with a variety of partner genes, including AFF1(AF4), MLLT1(ENL), and MLLT3(AF9).3,4

The mechanism of leukemogenesis in infants, in both MLL-rearranged (MLL-R) and MLL-germline (MLL-G) cases, is a subject of intensive investigation and may differ from leukemogenesis in older children.4–10 Studies of identical twins and retrospective analyses of neonatal blood spots have demonstrated that in many children, leukemia-initiating events may be acquired prenatally.5 Although several of the frequently recurring translocations (ETV6-RUNX1 and RUNX1-MTG8) associated with leukemia in older children have been demonstrated to arise in utero, they seem to be insufficient for leukemogenesis; leukemogenesis requires the acquisition of additional cooperating genetic lesions. This multistep process may account for the longer latency period before development of clinically overt leukemia. In contrast, in infants, latency is very short and MLL-R alone or in concert with only a few cooperating lesions may be sufficient for leukemogenesis. In support of this working hypothesis, whole genome studies of copy number variations or comparative genomic hybridization arrays in MLL-R infant ALL cases have demonstrated a very limited number of DNA copy-number alterations,4–6 in contrast to ALL arising in older children.11

MLL belongs to the Trithorax group of proteins that regulate gene expression through chromatin association and modification. MLL binds to thousands of loci in the genome that are important for the regulation of hematopoiesis, cell signaling, and transcription.7 Important downstream targets of MLL include genes within the Homeobox A (HOXA) cluster and MEIS1. These and other genes involved in transcriptional activation are partially regulated through histone H3K4 methylation by the Su(var)3-9, Enhancer of zeste, and Trithorax (SET) domain of wild-type MLL. In contrast, leukemogenic MLL fusion proteins lack a SET domain but retain the ability to bind and methylate H3K4, causing persistent activation of target genes that contribute to a distinctive pattern of gene expression characteristic of MLL-R leukemias.8 Thus, perturbed epigenetic regulation is likely to play a critical role in MLL-mediated leukemogenesis, and further insight into this mechanism may provide new insights for therapeutic intervention.8–10,12,13

The etiology and pathogenesis of infant ALL are complex and multifactorial, with critical in utero exposures, potential genetic susceptibility, MLL and other acquired genetic abnormalities, epigenetic dysregulation, and modifying influences all affecting the development and phenotype of the leukemia.14 Because patterns of gene expression may be reflective of these combined factors, we performed gene expression profiling in a cohort of 97 infant ALL cases accrued to Children's Oncology Group (COG) Trial P9407, the largest infant cohort examined to date. We wanted to determine whether we could identify genes that might improve risk classification and outcome prediction in infant ALL, beyond the well-established factors of MLL status and patient age. We further wanted to determine whether these profiles might provide new insight into this disease, reflect cooperating genetic lesions or pathways, and serve as potential diagnostic and therapeutic targets.

Methods

Patient selection and characteristics

In total, 212 infants < 365 days of age with ALL were enrolled onto COG P9407 study (NCT00002756; ClinicalTrials.gov) in 3 consecutive cohorts. A subset of 70 infants was enrolled between 1996 and 2000 on cohorts 1 and 2, and another 142 infants were enrolled between 2001 and 2006 on cohort 3.15 Infants in cohorts 1 and 2 were observed to have unacceptably high induction death rates, leading to modification of the treatment regimen for cohort 3. Pretreatment leukemia specimens were available from 97 of 212 of the cases accrued to this trial, predominantly from cohort 3.15 The preclinical and outcome characteristics of this cohort of 97 cases did not differ appreciably from the total 212 cases accrued (data not shown). Treatment protocols were approved by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and participating institutions through their institutional review boards. MLL rearrangements and MLL partner genes were characterized using cytogenetic and molecular methods.16 Informed consent for participation in these research studies was obtained from patients or authorized representatives. An independent validation cohort consisting of 57 cases of infant ALL with a variety of MLL translocations that had available U133_Plus_2 CEL files and outcome data was provided by Stam et al.8 The criteria for selection of validation cases were the same as for COG P9407 samples.

Gene expression profiling

RNA was isolated from pre-treatment leukemic cell suspensions obtained from peripheral blood or bone marrow using TRIzol (Invitrogen). All samples had more than 70% leukemic blasts, with a median of 90% blasts. cDNA labeling, hybridization to U133_Plus_2 arrays (Affymetrix), and scanning were performed as described previously (details in supplemental Methods, available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).17 The default RMA and MAS5 algorithms of Expression Console (Version 1.1; Affymetrix) were used to generate and normalize signal intensities. Array experimental quality parameters for inclusion into the study included scale factor, less than 40; GAPDH M33197 3′ intensity, more than 15 000; and GAPDH M33197 3′/5′ ratio, less than 3. Microarray gene expression data were available from an initial 54 504 probe sets after filtering to remove probe sets associated with sex-related genes, globins, and controls, as described previously.18 To minimize the impact of set effects in comparative analyses with the validation cohort, the 97 P9407 CEL files were combined with 73 infant cases from the validation cohort study8 (including cases for which clinical data were not available) and 21 MLL-R cases from a previously reported pediatric study17 before performing robust multichip average (RMA). The final RMA-normalized dataset contained 191 cases from 3 separate studies. The P9407 gene expression data may be accessed via the National Cancer Institute caArray site (https://array.nci.nih.gov/caarray/project/EXP-520).

Statistical analyses

Event-free survival (EFS) was calculated from the date of trial enrollment to either the date of first event (induction failure, relapse, second malignancy, or death) or last follow-up. Outcome analysis was performed only on cases where a death did not occur within 7 days of trial enrollment. This eliminated 2 cases from P9407 and 4 from the validation cohort. All cases were retained for studies correlating gene expression profiles with age as a continuous variable, because outcome associations were not required for these analyses.

Three gene filtering methods based on the coefficient of variation (CV), the standard deviation (SD), and cancer outlier profile analysis (COPA)19 were used to preselect probe sets. The union of the probes selected by these 3 methods was used for the further analyses. The significance analysis of microarray (SAM)20 was then used to identify the probe sets that were significantly associated with EFS and those that were significantly associated with age. Cox regression and log-rank tests further determined the significance of a variable (clinical covariate, gene expression value, predicted risk score, or risk group by a model) in predicting EFS, with and without adjusting for the effects of other variables. This provided a means to assess the predictive power of various genes or probe sets relative to established prognostic factors such as age and MLL status. Supervised principal component analysis (SPCA)21 and regression tree analysis22 were used to build outcome prediction models and to predict a score that positively correlated with event risk (higher scores correlated with increased risk of an event). Binary risk classification for event prediction was determined by a threshold τ (defined as α% of the predicted score), with values below the threshold predicting low risk and values above the threshold predicting high risk, where α% is the 2-year EFS probability of the original data. All analyses were performed using statistical software R (http://www.R-project.org; Version 2.14.0, with basic, samr, superpc, rpart, and survival packages) and Stata (Version 11; StataCorp). Pathway analyses and methods are described in supplemental Methods.

Hierarchical clustering and heat maps

Gene expression data (54 504 probe sets) from the 48 cases with MLL-AFF1 rearrangements in the infant ALL cohort from COG P9407 were sorted based on SD and the top 100 probe sets were selected for clustering. Hierarchical clustering was performed in MATLAB (The MathWorks) using Euclidean distance and average linkage. For the heat map of age-associated probe sets (treating patient age as a continuous variable), probe sets were ordered by their modified correlation coefficients as calculated with SAM. Expression intensity colors were displayed for each probe set relative to the average of the mean value of cases less than or equal to 90 days old and the mean value of cases more than 90 days old. Cases included all 97 P9407 infants in addition to 21 ALL samples from a cohort of older pediatric ALL cases with molecularly confirmed MLL-AFF1 translocations.17

Results

Clinical features

The clinical and biologic features of the cohort of 97 infant ALL cases studied from COG Trial P940715 are provided in Table 1. The overall outcome of the infants in this cohort was very poor, with a 5-year EFS of 41% ± 5% (Table 1). Three variables including patient age, white blood cell count (WBC) at disease presentation, and MLL status were significantly correlated with EFS (Table 1), whereas sex, race and ethnicity, and central nervous system status were not (data not shown). When WBC count was evaluated as a categorical variable (with a cutoff of 50 × 103/μL), patients with high WBC fared worse than those with low WBC.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and their outcome association (EFS)

| Entire cohort |

MLL-AFF1 patients |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value* | HR (SE)† | 5-y EFS (SE)‡ | P§ | Value* | HR (SE)† | 5-y EFS (SE)‡ | P§ | |

| Overall | ||||||||

| Total | 97 (100) | 0.41 (.05) | 48 (100) | 0.36 (.07) | ||||

| Age | .009 | .002 | ||||||

| ≤ 90 days | 24 (25) | 2.13 (.62) | .19 (.09) | 12 (25) | 3.25 (1.30) | 0 (NA) | ||

| > 90 days | 73 (75) | 1 | .48 (.06) | 36 (75) | 1 | .47 (.08) | ||

| Sex | .745 | .099 | ||||||

| Male | 54 (56) | 1.09 (.30) | .40 (.07) | 26 (54) | 1.82 (.68) | .28 (.09) | ||

| Female | 43 (44) | 1 | .42 (.08) | 22 (46) | 1 | .45 (.11) | ||

| WBC | .006 | .228 | ||||||

| ≥ 50 × 103/μL | 83 (86) | 5.70 (4.11) | .35 (.05) | 43 (91) | 3.20 (3.26) | .33 (.07) | ||

| < 50 × 103/μL | 13 (14) | 1 | .84 (.10) | 4 (9) | 1 | .75 (.22) | ||

| MLL status | .008 | |||||||

| Rearranged | 80 (82) | 3.23 (1.52) | .35 (.05) | 48 (100) | .36 (.07) | |||

| Germline | 17 (18) | 1 | .69 (.12) | 0 (0) | ||||

NA indicates not applicable.

Values are number and percentage of infants in parentheses.

HR is relative to the reference category (with HR = 1). SE indicates the standard error for each HR.

Five-year EFS survival probability and SE.

P value of log-rank test.

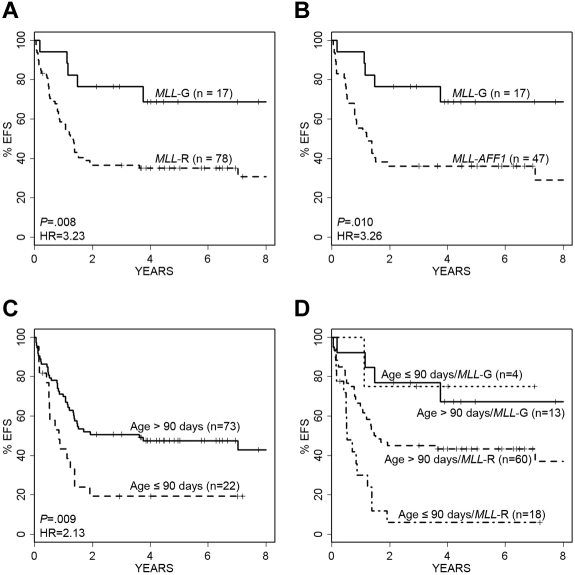

Infants with MLL rearrangements, and specifically MLL-AFF1, had significantly poorer outcomes than patients lacking MLL rearrangements (MLL-G; Figure 1A-B; Table 1). Applying an age threshold of 90 days, the youngest 22 patients had significantly worse EFS than older infants (Figure 1C). Because patient age and MLL status were both observed to be significant factors in predicting EFS, we explored their combined impact. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve in Figure 1D displays the behavior of each age–MLL category. Not surprisingly, the 18 patients who were in the highest risk category for both variables (MLL-R and ≤ 90 days) had the poorest overall outcome (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Impact of age and MLL status on EFS. Kaplan-Meier survival curves show the impact of infant age and MLL status on EFS. (A) Patients with MLL-R have significantly shorter EFS than those without rearrangements (MLL-G; P = .008, log-rank test; HR = 3.23). (B) MLL-AFF1 cases have a nearly identical outcome pattern to overall MLL-R (P = .010; HR = 3.26). (C) Younger infants (≤ 90 days old) compared with older infants (> 90 days old) have significantly worse EFS (P = .009, log-rank test; HR = 2.13). (D) Infants with MLL-G have the best EFS, whereas infants less than or equal to 90 days of age with MLL-R have the worst EFS. Note that 2 patients died within 7 days of diagnosis, and they were excluded from these analyses.

Gene expression profiling and modeling outcome genes in the full cohort

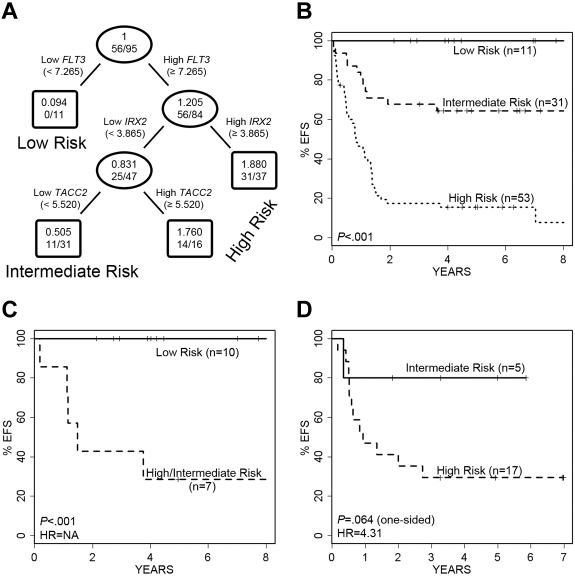

To identify genes from the expression profiles that were significantly correlated with EFS and to model an outcome predictor in the full cohort of 97 infant ALL cases, we performed SAM analysis on the 430 potentially informative probe sets first determined by high CV, SD, and COPA. The results of this analysis are provided in Table 2. Applying a false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff of 1%, only 5 probe sets (derived from 4 genes) were retained in the analysis: TACC2, IRX2, IL1R2, and FLT3 (Table 2). Each of these genes retained prognostic significance for outcome prediction beyond or independent of patient age, and all but FLT3 were significant for outcome prediction after adjusting for MLL status (Table 2). For all 4 genes, elevated expression was correlated with a poorer outcome. Interestingly, in pathways analysis (see supplemental Methods), 3 (TACC2, IL1R2, and FLT3) of these 4 genes are linked together with MEIS1, the Rab effector MYRIP, and the EGFR pathway gene EPS8, in a primary pathway centering on the GRB2 adapter signaling protein. A regression tree analysis of EFS was then developed and resulted in a final model in which only 3 of the 4 genes were retained (FLT3, TACC2, and IRX2), because IL1R2 did not retain independent prognostic significance in the context of the other 3 genes. This model for EFS is shown in Figure 2A. At each decision branch, the highest expressing cases fall into the high-risk category. Low FLT3 expression was found in a group of infants with excellent outcome (n = 11; 5-year EFS of 100%) termed the “low-risk group,” whereas differential expression of IRX2 and TACC2 partitioned the remaining infants into 2 groups (termed “intermediate risk” or “high risk”; Figure 2A-B). The net result of this predictive modeling defined and distinguished 3 outcome groups in infant ALL with significantly different EFS, including 11 low-, 31 intermediate-, and 53 high-risk cases (Figure 2B). The intermediate- versus high-risk groups had 5-year EFS of 16% versus 64% (P < .001), respectively (29% vs 71% for overall survival [OS]; supplemental Figure 2A). Similar findings were seen among the 23 infants less than or equal to 90 days old: 15 were high risk (12 died; 80%), 4 were intermediate risk (3 died; 75%), and 3 were low risk (none died).

Table 2.

Gene expression probe sets associated with outcome (EFS) in the entire infant ALL cohort

| Rank | Probe set | Gene symbol | Elevated in* | SAM analysis |

Cox regression analysis |

P (adjusted for MLL)† | P (adjusted for age)‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | FDR (%) | HR | P§ | ||||||

| 1 | 211382_s_at | TACC2 | High risk | 2.50 | < 1 | 1.51 | .001 | .007 | .001 |

| 2 | 228462_at | IRX2 | High risk | 2.23 | < 1 | 1.45 | .001 | .006 | .002 |

| 3 | 202289_s_at | TACC2 | High risk | 2.15 | < 1 | 1.42 | .003 | .028 | .007 |

| 4 | 205403_at | IL1R2 | High risk | 1.99 | < 1 | 1.48 | .001 | .018 | .016 |

| 5 | 206674_at | FLT3 | High risk | 1.94 | < 1 | 1.54 | .009 | .248 | .002 |

| 6 | 202609_at | EPS8 | High risk | 1.78 | 9.77 | 1.38 | .004 | .030 | .009 |

| 7 | 220448_at | KCNK12 | High risk | 1.77 | 9.77 | 1.39 | .019 | .428 | .015 |

| 8 | 204150_at | STAB1 | High risk | 1.77 | 9.77 | 1.42 | .003 | .019 | .012 |

| 9 | 214156_at | MYRIP | High risk | 1.76 | 9.77 | 1.49 | .001 | .008 | .008 |

| 10 | 204069_at | MEIS1 | High risk | 1.72 | 9.77 | 1.37 | .027 | .650 | .016 |

Bold denotes probe sets that are used for building the regression tree model.

Indicates risk group with which elevated expression is correlated.

P value indicating significance of the association between the expression of each gene and treatment outcome adjusting for the MLL status.

P value indicating significance of the association between the expression of each gene and treatment outcome adjusting for age effect.

P value of Wald test for the HR indicating significance of the association between the expression of each individual gene and treatment outcome.

Figure 2.

Performance of the 3-gene regression tree model of EFS in ALL cases. A 3-gene model was developed for prediction of EFS in the entire study cohort. (A) FLT3 expression separates infants into low- versus intermediate- and high-risk disease. Infants with high FLT3 expression are further divided into intermediate- and high-risk disease categories based on IRX2 and TACC2 expression. The ovals and boxes contain the relative risk followed by number of events/number of cases. (B) Kaplan-Meier survival curves show significant differences in EFS among the infants in the low-, intermediate-, and high-risk categories. (C) The model significantly separates MLL-G infants into 2 groups with significantly different EFS. NA indicates HR is not applicable because of absence of failures in 1 group. (D) Validation cohort of 22 MLL-AFF1 cases also is separated into 2 groups with different EFS. No infants with MLL-AFF1 and low FLT3 expression (low risk) were present.

The majority of “low-risk” cases (10/11) defined by our predictive model using FLT3 expression were MLL-G, with the remaining case an MLL-AFF1. To rule out the possibility that low FLT3 expression was simply identifying all of the MLL-G cases, we analyzed all 17 MLL-G cases in this cohort to see how they performed in our predictive model (Figure 2C). Although 10 of the MLL-G cases were assigned to our “low-risk” group, the remaining 7 were divided among “intermediate-risk” and “high-risk” groups, with highly significant different outcomes (P < .001). These analyses reveal that low FLT3 expression is not simply a reflection of MLL-G status, and conversely, that some patients with MLL-G have high FLT3 expression and a poorer outcome, as predicted by our refined model (P = .009 for OS; supplemental Figure 2B).

As a final step in the assessment of the predictive model, we analyzed the performance of this predictor on 22 MLL-AFF1 cases from an independent validation cohort of infants with ALL accrued to the Interfant-99 infant ALL study (Figure 2D and supplemental Figure 2C). These cases were chosen because they represented the largest subset in that cohort and shared similar overall survivals to the infants in COG P9407. No low FLT3-expressing cases were present among these patients, so only intermediate- and high-risk cases were examined. The model partitioned the 22 cases into 5 intermediate-risk and 17 high-risk infants. Although the outcome differences are large (hazard ratio [HR] = 4.31), the small sample size resulted in P values for EFS and OS that did not reach levels of statistical significance (P = .064 and P = .119, respectively). However, when relapse-free survival was modeled instead of EFS, the single event in the intermediate-risk group disappeared and the performance reached statistical significance (P = .018).

Gene expression profiling and modeling outcome genes in MLL-AFF1 cases

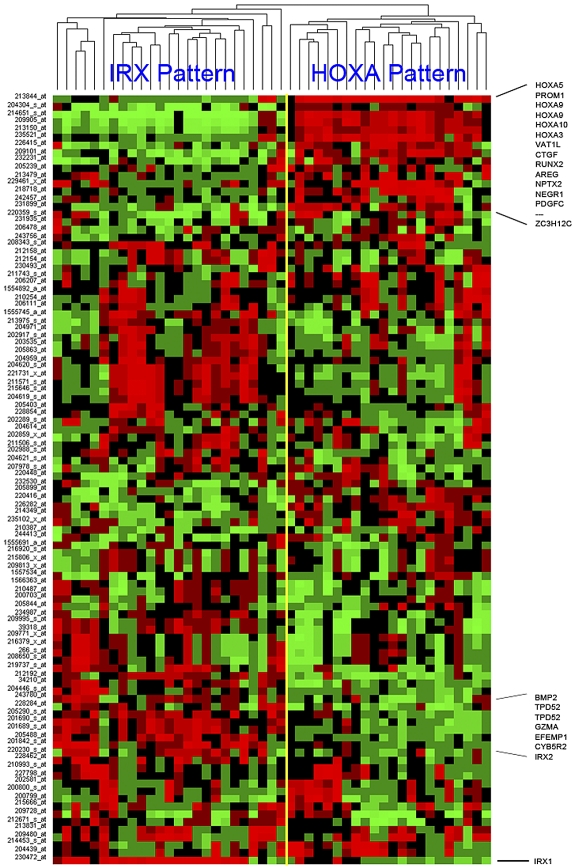

MLL-AFF1 (MLL-AF4) cases represent the single largest subset of patients within the COG P9407 infant ALL cohort, making up 48 of the 97 (49%) cases. Despite sharing an initiating translocation (MLL-AFF1), unsupervised hierarchical clustering (using the top 100 genes ranked according to SD) of the 48 MLL-AFF1 cases showed a surprising degree of heterogeneity with 2 predominant cluster groups (Figure 3). Similar to what has been reported recently by others,8,23 we observed a clear separation of the MLL-AFF1 cases into 2 distinctive clusters dominated by the expression of homeobox genes: HOXA3, HOXA5, HOXA9, and HOXA10 (referred to as the HOXA pattern) or by IRX1 and IRX2 (referred to as the IRX pattern). Several other genes were differentially expressed within these 2 distinct clusters, but the expression of either elevated HOXA or IRX genes was the dominant feature (Figure 3). Many of the genes that defined these distinct unsupervised clusters had associations with EFS, and it was interesting to note that many of these cluster-associated probe sets (including IRX1, IRX2, NEGR1, TPD52, andVAT1L) were identified as genes predictive of outcome in supervised learning, because we built the model for outcome prediction for the MLL-AFF1 cases detailed in the following 2 paragraphs.

Figure 3.

Hierarchical clustering of MLL-AFF1 cases using top 100 SD probe sets. The top 100 probe sets, ranked by SD, were used to cluster the 48 MLL-AFF1 cases. The yellow bar indicates the branch point defining the 2 major cluster patterns. These patterns are named after the family of homeobox genes most commonly and highly expressed by its members (IRX or HOXA). Samples are shown in columns and probe sets are in rows. Captions across the right indicate the positions of some of the more conserved genes across a cluster. Increasing (red) or decreasing (green) gene expression is shown relative to the median (black) for each gene.

We next used supervised analysis to build a model for outcome prediction (EFS) in the infants with MLL-AFF1. As with the entire cohort, a SAM analysis was performed on the 214 potentially informative genes initially identified by CV, SD, and COPA. Applying an FDR cutoff of 15%, 29 probe sets (representing 22 genes) were retained. Unlike the model built on the entire cohort, elevated expression of 2 of these probe sets correlated with a lower risk or a good outcome (Table 3 ranks 1 and 2), and expression of 27 probe sets correlated with a higher risk or poorer outcome (Table 3 ranks 3-27). Among these 22 genes, 5 (EPS8, IL1R2, IRX2, MYRIP, and TACC2) were identified previously when we built the predictive model for outcome in the entire infant ALL cohort.

Table 3.

Gene expression probe sets associated with outcome (EFS) in patients with MLL-AFF1

| Rank | Probe set | Gene symbol | Elevated in* | SAM analysis |

Cox regression |

P (adjusted for age)‡ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | FDR (%) | HR | P† | |||||

| 1 | 229461_x_at | NEGR1 | Low risk | −2.35 | 12.25 | 0.54 | .005 | .015 |

| 2 | 226415_at | VAT1L | Low risk | −2.19 | 12.25 | 0.59 | .007 | .014 |

| 1 | 228462_at | IRX2 | High risk | 2.08 | 10.93 | 1.53 | .010 | .010 |

| 2 | 230472_at | IRX1 | High risk | 1.99 | 10.93 | 1.51 | .023 | .060 |

| 3 | 202609_at | EPS8 | High risk | 1.99 | 10.93 | 1.52 | .006 | .036 |

| 4 | 201688_s_at | TPD52 | High risk | 1.97 | 10.93 | 1.63 | .008 | .012 |

| 5 | 214156_at | MYRIP | High risk | 1.92 | 10.93 | 1.64 | .005 | .055 |

| 6 | 209480_at | HLA-DQB1 | High risk | 1.89 | 10.93 | 1.49 | .023 | .006 |

| 7 | 205403_at | IL1R2 | High risk | 1.84 | 10.93 | 1.54 | .015 | .153 |

| 8 | 212192_at | KCTD12 | High risk | 1.83 | 10.93 | 1.56 | .021 | .059 |

| 9 | 201743_at | CD14 | High risk | 1.73 | 10.93 | 1.50 | .017 | .121 |

| 10 | 1555745_a_at | LYZ | High risk | 1.73 | 10.93 | 1.53 | .031 | .059 |

| 11 | 203535_at | S100A9 | High risk | 1.70 | 10.93 | 1.51 | .030 | .091 |

| 12 | 238900_at | HLA-DRB1… | High risk | 1.70 | 10.93 | 1.48 | .018 | .031 |

| 13 | 201689_s_at | TPD52 | High risk | 1.67 | 10.93 | 1.49 | .029 | .027 |

| 14 | 204959_at | MNDA | High risk | 1.65 | 10.93 | 1.51 | .032 | .202 |

| 15 | 211372_s_at | IL1R2 | High risk | 1.64 | 10.93 | 1.65 | .008 | .156 |

| 16 | 218454_at | PLBD1 | High risk | 1.61 | 10.93 | 1.55 | .015 | .159 |

| 17 | 211571_s_at | VCAN | High risk | 1.59 | 10.93 | 1.44 | .046 | .192 |

| 18 | 202289_s_at | TACC2 | High risk | 1.56 | 10.93 | 1.45 | .039 | .055 |

| 19 | 228434_at | BTNL9 | High risk | 1.56 | 10.93 | 1.58 | .021 | .064 |

| 20 | 202917_s_at | S100A8 | High risk | 1.55 | 10.93 | 1.48 | .054 | .098 |

| 21 | 204620_s_at | VCAN | High risk | 1.54 | 10.93 | 1.43 | .058 | .210 |

| 22 | 205863_at | S100A12 | High risk | 1.52 | 10.93 | 1.43 | .043 | .145 |

| 23 | 201690_s_at | TPD52 | High risk | 1.50 | 10.93 | 1.49 | .047 | .039 |

| 24 | 204619_s_at | VCAN | High risk | 1.48 | 10.93 | 1.40 | .058 | .194 |

| 25 | 215646_s_at | VCAN | High risk | 1.45 | 10.93 | 1.39 | .070 | .217 |

| 26 | 221731_x_at | VCAN | High risk | 1.45 | 10.93 | 1.41 | .076 | .238 |

| 27 | 204971_at | CSTA | High risk | 1.40 | 12.25 | 1.44 | .071 | .260 |

Bold denotes probe sets that are used for building the 7-gene (9-probe set) SPCA model.

Indicates risk group with which elevated expression is correlated.

P value of Wald test for the HR indicating significance of the association between the expression of each individual gene and treatment outcome.

P value indicating significance of the association between the expression of each gene and treatment outcome adjusting for age effect.

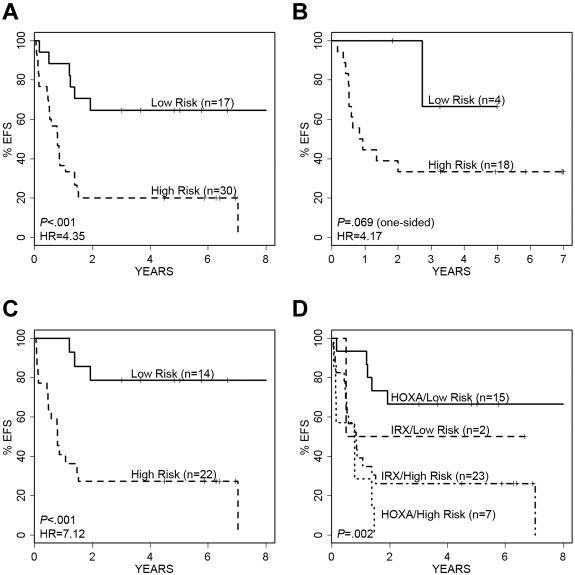

Using these 29 probe sets, we built an SPCA model which significantly separated 47 MLL-AFF1 cases into a low- and a high-risk group; this model was also predictive of outcome when tested against the independent validation cohort of 22 MLL-AFF1 cases from the Interfant-99 study (see details in supplemental Methods). Because of the known impact of patient age on outcome in infant ALL, we rebuilt the SPCA model with only those probe sets that retained significance after adjusting for age (the 9 probe sets derived from 7 genes as noted in bold; Table 3): NEGR1, VAT1L, IRX2, EPS8, TPD52, HLA-DQB1, and HLA-DRB1. This 7-gene predictor separated the 47 MLL-AFF1 cases from our study into 17 “low-risk” (5-year EFS of 65% ± 12%) and 30 “high-risk” cases (5-year EFS of 20% ± 7%; Figure 4A); HR = 4.35, log-rank P < .001. The results for OS were comparable (HR = 5.61; P < .001; supplemental Figure 4A). Figure 4B illustrates the performance of the model on the 22 MLL-AFF1 cases in the independent validation cohort, showing a clear separation of cases by EFS (HR = 4.17; P = .069) and OS (HR = 3.16; P = .124). The small number of cases in the independent valida-tion cohort and their limited risk distribution decreased the statistical power.

Figure 4.

Performance of the 7-gene (9-probe set) SPCA model of EFS in MLL-AFF1 cases. Kaplan-Meier survival curves showing prediction of EFS and relapse-free survival in our cohort and the independent validation cohort. (A) The 7-gene model separates the 47 MLL-AFF1 cases into low- and high-risk groups with significantly different EFS. (B) Validation cohort of 22 MLL-AFF1 cases are similarly separated into 2 groups with significantly different EFS based on our model. (C) The 7 gene model also significantly separates the 36 older (> 90 days) MLL-AFF1 infants into low- and high-risk groups. (D) Model overlaps significantly with the P9407 MLL-AFF1 unsupervised clusters; however, it also adds significant predictive risk information, particularly in the HOXA pattern cases.

We further examined the power of this predictive model relative to patient age in the MLL-AFF1 cases (using a 90-day cutoff). As shown in Figure 4C, the 7-gene classifier effectively stratified the 36 infants more than 90 days of age into low versus high risk for EFS (HR = 7.12; P < .001) and for OS (HR = 11.2; P < .001; supplemental Figure 4C). All 11 infants less than or equal to 90 days of age died, including 8 identified by the model as high risk and 3 as low risk.

Although similar genes were identified through unsupervised clustering of MLL-AFF1 cases (Figure 3), the 7-gene predictive model built through supervised methods was more precise for outcome prediction and effectively stratified risk in both the IRX-clustered and HOXA-clustered cases (Figures 3 and 4D; supplemental Figure 4D). The 17 “low-risk” cases include 15 HOXA cluster and 2 IRX cluster cases, with 5 and 1 event, respectively. Within the 30 “high-risk” cases were 7 HOXA and 23 IRX cases, with 7 and 18 events, respectively. Even though the HOXA cluster phenotype (Figure 3) was generally associated with better outcome, the supervised EFS model distinguished 7 “high-risk” cases, all of whom had events (contrasted with the 33% rate among the 15 HOXA cluster-type “low-risk” cases).

Gene expression profiles associated with patient age

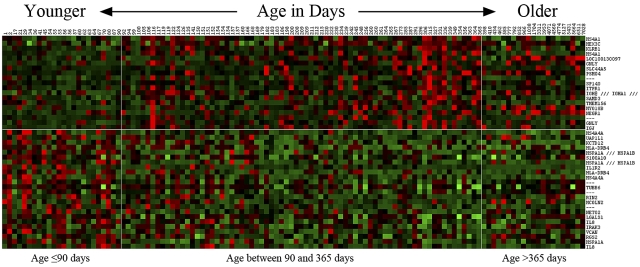

Given the historical significance of patient age in infant leukemia and the striking association of outcome with patient age in our infant cohort, we sought to determine whether there was a significant correlation of gene expression and patient age in our cohort of MLL-AFF1 infant ALL cases. By treating leukemia cell gene expression as a continuous variable related to patient age in these infants, we found a dramatic change in gene expression patterns at ∼ 90 days of age, with a striking difference in gene expression patterns in infants less than or equal to 90 days versus those greater than 90 days in age. Figure 5 shows the top 43 probe sets (24 with increased expression associated with lower age and 19 with increased expression associated with higher age). In addition, when we included 21 older children with ALL containing MLL-AFF1 translocations from our COG P9906 studies17 in this analysis, they clustered with the older infants from COG P9407. This showed that infants more than 90 days of age have a gene expression signature more similar to older children than to infants less than 90 days of age.

Figure 5.

Heat map of probe sets associated with patient age. The top 43 probe sets associated with age (as a continuous variable) at the significance level FDR = 15% were used to generate a heat map. Patients are ordered from left to right by ascending age. In addition to the 97 infant ALL patients, 21 pediatric MLL cases are included. Vertical white lines indicate the positions of age landmarks, and the horizontal line separates between the probe sets whose expressions are positively (top) and negatively (bottom) correlated with age. Age of patients is indicated across the top.

Several genes associated with antibody production and B-cell maturation (eg, IGJ, IGH, and MS4A1) were expressed at higher levels in the leukemic cells from infants more than 90 days old, raising the possibility that MLL-AFF1 leukemias in older children might be arising in a more committed B-cell progenitor than in younger infants. These older infants also had elevated expression of genes linked with natural killer cells and antigen stimulation (KLRB1 and GNLY). In contrast, the younger patients had elevated expression of interleukin-related genes (IL1R2, IL8, and IRAK3), heat-shock proteins (HSPA1A) and HLA genes (HLA-DRB4) that are linked through IL13 and IL1A to define a pattern associated with inflammatory responses, cellular movement, and immune cell trafficking (supplemental Figure 6B).

Discussion

Our study of 97 infants with ALL (80/97 with MLL-R), accrued to COG Infant ALL Trial P9407, represents the largest cohort of infants reported to date to undergo gene expression profiling. The 5-year EFS among these infants was very poor (41%), with superior survivals seen among infants with MLL-G, age more than 90 days, and low WBC counts at disease presentation. Expression profiling initially identified a number of genes that were significantly associated with EFS in the infant cohort (EPS8, TACC2, FLT3, MEIS1, and IL1R2), including genes known to play a role in MLL-mediated leukemogenesis (MEIS1), tumor progression (STAB1), and therapeutic resistance in T-cell malignancies (KCNK12).24,25 Pathways analyses further demonstrated complex interaction patterns among these genes, all converging on the adaptor protein GRB2 that plays a critical role in tyrosine kinase and Ras cell-signaling pathways (detailed analysis in supplemental Figure 5).

Our final model predictive of outcome in the entire infant ALL cohort included 3 key genes (FLT3, TACC2, and IRX2) that refined risk classification and outcome prediction beyond age and MLL status. Differential FLT3 expression was uniquely powerful, because low FLT3 expression identified a group of infants with a very favorable outcome. This group of infants, with a superior 5-year EFS of 100% (including 9 MLL-G and 1 MLL-AFF1 case) had not been identified previously using any other classification algorithm. Conversely, the remaining infants who were MLL-G (7/17) but had high FLT3 expression had an outcome similar to those infants with MLL-R (5-year EFS of 29% ± 17% vs 34% ± 5, respectively). High FLT3 expression is common in infants and children with MLL-R or high hyperdiploidy (> 50 chromosomes) ALL, even in the absence of activating FLT3 mutations.26 High expression of wild-type FLT3 may act similarly to FLT3 mutants or internal tandem duplications by activating Ras-Raf-MAPK–signaling pathways.27 Because leukemogenesis is a multistep process, high FLT3 activity may be a second “hit,” in concert with MLL, to induce leukemogenesis in MLL-R infants.

In the development of the outcome predictor for the full cohort, our regression tree analysis further identified TACC2 and IRX2 as 2 important genes that significantly impacted infants with high FLT3 expression. Infants with high expression of either TACC2 or IRX2 had a significantly worse 5-year EFS of 15% compared with 64% in infants with low expression of both genes. How the expression of these genes might be altered by underlying MLL rearrangements or other epigenetic changes in infant ALL is of interest. MLL functions as an epigenetic regulator during normal development by incorporating into a COMPAS-like complex that facilitates H3K4 methylation that is required for the transcriptional activation of developmental regulatory genes, including homeobox genes and target genes of the WNT signaling pathway.7 When MLL is translocated, domains involved in methylation such as SET are lost and MLL fusion proteins recruit alternative histone methyltransferases, resulting in inappropriate histone modification and dysregulation of gene expression.3 In addition to the potential activation of FLT3, this mechanism may underlie the activation of TACC2, a component of the chromatin modification machinery whose expression is regulated through binding of SMYD2 to the TACC2 promoter.28 The SET domain on SMYD2 acts as a methyltransferase and specifically methylates H3K4, similar to MLL. Methylation of H3K4 is generally associated with activation of gene expression, and in addition to TACC2 activation, SMYD2 up-regulates proteins in the SWI-SNF chromatin remodeling complex and methylates p53.29 This complex interaction between TACC2 and the SWI-SNF complex suggests that perturbed chromatin remodeling may promote malignant transformation. The SWI-SNF complex also has been implicated in other cancers through a variety of mechanisms.30

The iroquois (IRO/IRX) genes encode transcriptional regulators that belong to the tree amino acid loop extension class of homeobox genes.31 IRX2 controls developmental processes via the WNT pathway, whereas WNT signaling itself regulates homeobox genes and other targets of hematopoietic differentiation. IRX2 is located in a chromosomal region, 5p15.33, linked to several cancer types.32 The related family member IRX1 also located at 5p15.33, seems to function as a tumor suppressor in solid tumors.33,34 An additional gene localized to 5p15.33 that may be affected by abnormal IRX2 expression is TERT that maintains genomic integrity by regulating telomerase activity to allow restoration of telomere length.35 Maintaining TERT expression and preventing senescence may be a mechanism whereby fusion proteins, such as MLL-AFF1, mediated by HOXA genes, support self-renewal in leukemic cells.36

Unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the MLL-AFF1 infants in our cohort yielded 2 cluster groups with distinct gene expression signatures dominated by homeobox genes (HOXA or IRX). The cluster with high HOXA expression is characteristic of MLL-R ALL, whereas low HOXA (and high IRX) expression is unique among infants with MLL-AFF1 and has been shown previously to be associated with a higher rate of relapse.8,23 When we used supervised learning to model an outcome predictor in these MLL-AFF1 cases, a 29-probe set (22 gene) expression classifier better predicted EFS than the unsupervised hierarchical clustering. This predictive model was further reduced to 7 genes (NEGR1, VAT1L, IRX2, EPS8, TPD52, HLA-DQB1, and HLA-DRB1) after removal of genes associated with patient age. Some of the highly expressed, and age-independent genes, that best predicted for poor EFS in MLL-AFF1 infants also predicted for poor EFS in the entire study cohort (IRX2 and EPS8). EPS8 is an oncoprotein that participates in v-Src–induced cellular transformation, with over-expression enhancing cell proliferation, migration, and tumorigenicity.37,38 Tumor protein D52 (TPD52) plays a role in Ca2+-dependent membrane trafficking in proliferating cancer cells and is also a B-cell differentiation marker overexpressed in subsets of pediatric acute leukemia.39,40 Genes associated with a poorer outcome in this predictor also included human leukocyte antigen class II genes (HLA-DQB1 and multiple HLA-DRB) involved in modulating immune responses.41 In the MLL-AFF1 infant ALL cases, NEGR1 was the most significant gene predictor of EFS; high expression was associated with a superior EFS. NEGR1 is a member of the IgLON family of cell adhesion molecules and maps to chromosome 1p31.1. Some members of this family (OPCML, HNT, LSMAP) are proposed to be tumor suppressors.42

When the gene expression profiles derived from the infant ALL cases were treated as a continuous variable related to patient age (without knowledge of MLL status, outcome, or other clinical features), a striking change was observed around 90 days of age. This biologic observation is highly interesting, as infants less than or equal to 90 days versus those more than 90 days of age have historically been observed to have significantly different treatment outcomes. Our studies are the first to show a striking transition in leukemia cell expression signatures at this time point. These age-related patterns suggest different mechanisms of leukemogenesis and may underlie the differential outcomes historically seen in these age groups.

The expression profiles in infants more than 90 days of age are more similar to older children with ALL than to infants less than or equal to 90 days old.43 MLL-AFF1 leukemias in older infants and children may arise hypothetically from a more committed B-cell progenitor than in younger infants, given the elevated expression of genes linked with natural killer cells and antigen stimulation (KLRB1 and GNLY) and their associations with cellular assembly and organizational pathways (supplemental Figure 6A). In contrast, younger infants had elevated expression of interleukin-related genes (IL1R2, IL8, and IRAK3), heat-shock proteins (HSPA1A and HSPA1B), and HLA genes (HLA-DRB4 and HLA-DQ) associated with the regulation of inflammatory responses. Whether this profile is reflective of the transformed cell of origin, a different marrow microenvironment, or different immune status in younger infants remains to be determined. These youngest infants may be more susceptible to the development of acute leukemia in utero, because specific HLA-DRB and HLA-DRQ haplotypes have been associated with different forms of leukemia and may be linked to polymorphisms in heat-shock protein genes (HSPA1A and HSPA1B) located in the HLA class III region.41,44 Polymorphisms of HSPA1A, HSPA1B, and other inflammatory or immunomodulatory genes, such as IL-8 or VCAN, also have been reported to influence susceptibility to cancer.45,46

In conclusion, we have developed gene expression classifiers that improve outcome prediction in infant ALL, beyond the well-established prognostic factors of patient age and MLL gene rearrangement status. Assessment of the expression levels of this relatively small number of genes that improve outcome prediction in the full cohort (FLT3, TACC2, and IRX2) or in the subset of MLL-AFF1 cases (NEGR1, VAT1L, IRX2, EPS8, TPD52, HLA-DQB1, and HLA-DRB1) can easily be transitioned to a clinically useful diagnostic assay. Importantly, we can define those infants who today have excellent responses to current therapies versus those who require the development of new approaches for cure, and we can distinguish outcomes within the most predominant subset of infant ALL cases with MLL-AFF1 translocations. We also have found that higher expression of FLT3 identifies a group of MLL-G cases that has a poorer outcome than expected. Future inclusion of these infants in clinical trials testing FLT3 inhibitors, such as the COG Trial AALL0631 (NCT00557193) that randomizes infants with MLL-R to receive chemotherapy with or without the FLT3 inhibitor lestaurtinib may improve their outcomes. The genes and pathways that we have identified not only serve as potential diagnostic targets but also as potential therapeutic targets. As proposed by Stumpel et al, gene expression patterns that predict for poorer EFS in infant ALL, reflective of the aberrant epigenetic regulation in this disease, such as those defined in this study, suggest a role for demethylating agents in the treatment of infant ALL.9 Our assessment of the role of these genes in pathways analysis also has identified key nodes that might be considered for targeted therapy, such as GRB2, that are centrally regulated by the high expression of multiple genes associated with a poorer outcome in infant ALL.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Strategic Partnerships to Evaluate Cancer Gene Signatures Program (U01 CA114762, C.L.W.), Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Specialized Center of Research (7372-07, C.A.F.), Leukemia & Lymphoma Society Specialized Center of Research (7388-06, C.L.W.), National Cancer Institute (Children's Oncology Group, chair's award U10 CA098543), U10 CA98413 (Children's Oncology Group Statistical Center), human specimen banking in National Cancer Institute-supported cancer trials (U24 CA114766), National Institutes of Health (R01 CA080175, C.A.F.), and National Cancer Institute (P30 CA118100; University of New Mexico Cancer Center Shared Resources). S.P.H. is the Ergen Family Chair in Pediatric Cancer.

Footnotes

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: H.K. performed statistical modeling and analyses and prepared the manuscript; C.S.W. performed data analysis and reviewed and prepared the manuscript; R.C.H. performed microarray studies, statistical modeling, and analyses and prepared the manuscript; I.-M.C. performed leukemia sample processing and microarray studies; M.H.M. conducted data management and data analyses; S.R.A. conducted pathway analyses, data analysis, and review; E.J.B. performed statistical modeling and analyses; M.D. conducted COG clinical and statistical analyses, data review, and analysis; A.J.C. and N.A.H. performed cytogenetic analysis; B.W.R. conducted MLL partner gene classification; R.W.S. designed the validation dataset; M.G.V. collected and processed patient information for the validation dataset; R.P. designed the validation dataset; J.M.H., C.A.F., G.H.R., B.C., N.W., W.L.C., Z.E.D., and S.P.H. designed the COG studies, performed data analysis, and reviewed the manuscript; and C.L.W. oversaw all aspects of this project; performed study design, data analysis, and review; and prepared the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: C.A.F. owns the following patent: Methods and Kits for Analysis of Chromosomal Rearrangements Associated with Leukemia–US Patent #6,368,791 (issued April 9, 2002); the panhandle PCR method that is the subject of the patent and derivative methods were used to classify MLL rearrangements in this study. The remaining authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Cheryl L. Willman, UNM Cancer Center, 1201 Camino de Salud NE, Rm 4630 MSC07-4024, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM 87131-0001; e-mail: cwillman@salud.unm.edu.

References

- 1.Pieters R, Schrappe M, De Lorenzo P, et al. A treatment protocol for infants younger than 1 year with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (Interfant-99): an observational study and a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9583):240–250. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61126-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hilden JM, Dinndorf PA, Meerbaum SO, et al. Analysis of prognostic factors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in infants: report on CCG 1953 from the Children's Oncology Group. Blood. 2006;108(2):441–451. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krivtsov AV, Armstrong SA. MLL translocations, histone modifications and leukaemia stem-cell development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7(11):823–833. doi: 10.1038/nrc2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bardini M, Spinelli R, Bungaro S, et al. DNA copy-number abnormalities do not occur in infant ALL with t(4;11)/MLL-AF4. Leukemia. 2010;24(1):169–176. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gale KB, Ford AM, Repp R, et al. Backtracking leukemia to birth: Identification of clonotypic gene fusion sequences in neonatal blood spots. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(25):13950–13954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bardini M, Galbiati M, Lettieri A, et al. Implementation of array based whole-genome high-resolution technologies confirms the absence of secondary copy-number alterations in MLL-AF4-positive infant ALL patients. Leukemia. 2011;25(1):175–178. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohan M, Lin C, Guest E, Shilatifard A. Licensed to elongate: a molecular mechanism for MLL-based leukaemogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(10):721–728. doi: 10.1038/nrc2915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stam RW, Schneider P, Hagelstein JA, et al. Gene expression profiling-based dissection of MLL translocated and MLL germline acute lymphoblastic leukemia in infants. Blood. 2010;115(14):2835–2844. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-233049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stumpel DJ, Schneider P, van Roon EH, et al. Specific promoter methylation identifies different subgroups of MLL-rearranged infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia, influences clinical outcome, and provides therapeutic options. Blood. 2009;114(27):5490–5498. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-227660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krivtsov AV, Feng Z, Lemieux ME, et al. H3K79 methylation profiles define murine and human MLL-AF4 leukemias. Cancer Cell. 2008;14(5):355–368. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mullighan CG, Goorha S, Radtke I, et al. Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature. 2007;446(7137):758–764. doi: 10.1038/nature05690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schafer E, Irizarry R, Negi S, et al. Promoter hypermethylation in MLL-r infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia: biology and therapeutic targeting. Blood. 2010;115(23):4798–4809. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-09-243634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stumpel DJ, Schotte D, Lange-Turenhout EA, et al. Hypermethylation of specific microRNA genes in MLL-rearranged infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia: major matters at a micro scale. Leukemia. 2011;25:429–439. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greaves M. Infection, immune responses and the aetiology of childhood leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(3):193–203. doi: 10.1038/nrc1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dreyer ZE, Dinndorf P, Joanne HM, et al. Unexpected toxicity with intensified induction in infant acute lymphoid leukemia. ASH Ann Meet Abstr. 2007;110(11):852. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robinson BW, Felix CA. Panhandle PCR approaches to cloning MLL genomic breakpoint junctions and fusion transcript sequences. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;538:85–114. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-418-6_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang H, Chen IM, Wilson CS, et al. Gene expression classifiers for relapse-free survival and minimal residual disease improve risk classification and outcome prediction in pediatric B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2010;115(7):1394–1405. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-218560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harvey RC, Mullighan CG, Wang X, et al. Identification of novel cluster groups in pediatric high-risk B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia with gene expression profiling: correlation with genome-wide DNA copy number alterations, clinical characteristics, and outcome. Blood. 2010;116(23):4874–4884. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-239681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.MacDonald JW, Ghosh D. COPA–cancer outlier profile analysis. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(23):2950–2951. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(9):5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bair E, Hastie T, Paul D, Tibshirani R. Prediction by supervised principal components. J Am Stat Assoc. 2006;101(473):119–137. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breiman L. Classification and Regression Trees. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth International Group; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trentin L, Giordan M, Dingermann T, Basso G, Te Kronnie G, Marschalek R. Two independent gene signatures in pediatric t(4;11) acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients. Eur J Haematol. 2009;83(5):406–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2009.01305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomes AQ, Correia DV, Grosso AR, et al. Identification of a panel of ten cell surface protein antigens associated with immunotargeting of leukemias and lymphomas by peripheral blood gammadelta T cells. Haematologica. 2010;95(8):1397–1404. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.020602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kzhyshkowska J. Multifunctional receptor stabilin-1 in homeostasis and disease. ScientificWorld J. 2010;10:2039–2053. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2010.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stam RW, Schneider P, de Lorenzo P, Valsecchi MG, den Boer ML, Pieters R. Prognostic significance of high-level FLT3 expression in MLL-rearranged infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2007;110(7):2774–2775. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ono R, Kumagai H, Nakajima H, et al. Mixed-lineage-leukemia (MLL) fusion protein collaborates with Ras to induce acute leukemia through aberrant Hox expression and Raf activation. Leukemia. 2009;23(12):2197–2209. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abu-Farha M, Lambert JP, Al-Madhoun AS, Elisma F, Skerjanc IS, Figeys D. The tale of two domains: proteomics and genomics analysis of SMYD2, a new histone methyltransferase. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7(3):560–572. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700271-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dou Z, Ding X, Zereshki A, et al. TTK kinase is essential for the centrosomal localization of TACC2. FEBS Lett. 2004;572(1-3):51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberts CW, Orkin SH. The SWI/SNF complex–chromatin and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4(2):133–142. doi: 10.1038/nrc1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bürglin TR. Analysis of TALE superclass homeobox genes (MEIS, PBC, KNOX, Iroquois, TGIF) reveals a novel domain conserved between plants and animals. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(21):4173–4180. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.21.4173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baird DM. Variation at the TERT locus and predisposition for cancer. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2010;12:e16. doi: 10.1017/S146239941000147X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo X, Liu W, Pan Y, et al. Homeobox gene IRX1 is a tumor suppressor gene in gastric carcinoma. Oncogene. 2010;29(27):3908–3920. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamalakaran S, Varadan V, Giercksky Russnes HE, et al. DNA methylation patterns in luminal breast cancers differ from non-luminal subtypes and can identify relapse risk independent of other clinical variables. Mol Oncol. 2011;5(1):77–92. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gessner A, Thomas M, Castro PG, et al. Leukemic fusion genes MLL/AF4 and AML1/MTG8 support leukemic self-renewal by controlling expression of the telomerase subunit TERT. Leukemia. 2010;24(10):1751–1759. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greaves MF, Maia AT, Wiemels JL, Ford AM. Leukemia in twins: lessons in natural history. Blood. 2003;102(7):2321–2333. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bashir M, Kirmani D, Bhat HF, et al. P66shc and its downstream Eps8 and Rac1 proteins are upregulated in esophageal cancers. Cell Commun Signal. 2010;8:13. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen H, Wu X, Pan ZK, Huang S. Integrity of SOS1/EPS8/ABI1 tri-complex determines ovarian cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 2010;70(23):9979–9990. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barbaric D, Byth K, Dalla-Pozza L, Byrne JA. Expression of tumor protein D52-like genes in childhood leukemia at diagnosis: clinical and sample considerations. Leuk Res. 2006;30(11):1355–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shehata M, Weidenhofer J, Thamotharampillai K, Hardy JR, Byrne JA. Tumor protein D52 over-expression and gene amplification in cancers from a mosaic of microarrays. Crit Rev Oncog. 2008;14(1):33–55. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v14.i1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hosking FJ, Leslie S, Dilthey A, et al. MHC variation and risk of childhood B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2011;117(5):1633–1640. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-301598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ntougkos E, Rush R, Scott D, et al. The IgLON family in epithelial ovarian cancer: expression profiles and clinicopathologic correlates. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(16):5764–5768. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jansen MW, Corral L, van der Velden VH, et al. Immunobiological diversity in infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia is related to the occurrence and type of MLL gene rearrangement. Leukemia. 2007;21(4):633–641. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ucisik-Akkaya E, Davis CF, Gorodezky C, Alaez C, Dorak MT. HLA complex-linked heat shock protein genes and childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia susceptibility. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2010;15(5):475–485. doi: 10.1007/s12192-009-0161-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shahzad MM, Arevalo JM, Armaiz-Pena GN, et al. Stress effects on FosB- and interleukin-8 (IL8)-driven ovarian cancer growth and metastasis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(46):35462–35470. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.109579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Snoussi K, Mahfoudh W, Bouaouina N, et al. Combined effects of IL-8 and CXCR2 gene polymorphisms on breast cancer susceptibility and aggressiveness. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:283. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.