Abstract

Viral infection depends on a complex interplay between host and viral factors. Here, we link host susceptibility to viral infection to a network encompassing sulfur metabolism, tRNA modification, competitive binding, and programmed ribosomal frameshifting (PRF). We first demonstrate that the iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis pathway in Escherichia coli exerts a protective effect during lambda phage infection, while a tRNA thiolation pathway enhances viral infection. We show that tRNALys uridine 34 modification inhibits PRF to influence the ratio of lambda phage proteins gpG and gpGT. Computational modeling and experiments suggest that the role of the iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis pathway in infection is indirect, via competitive binding of the shared sulfur donor IscS. Based on the universality of many key components of this network, in both the host and the virus, we anticipate that these findings may have broad relevance to understanding other infections, including viral infection of humans.

Keywords: bacteriophage lambda, host-virus, iron-sulfur clusters, programmed ribosomal frameshifting, tRNA modification

Introduction

All viruses require host translational machinery in order to replicate. To make use of this machinery while avoiding detection, viruses have evolved a number of unconventional translational strategies (Gale et al, 2000), including internal ribosome entry sites (Jang et al, 1988), leaky scanning (Schwartz et al, 1990), ribosome shunting (Schmidt-Puchta et al, 1997), reinitiation (Hemmings-Mieszczak et al, 1997), and programmed ribosomal frameshifting (PRF) (Gesteland and Atkins, 1996). Many of these strategies are unique to viruses, and thus are potential antiviral targets (Harford, 1995).

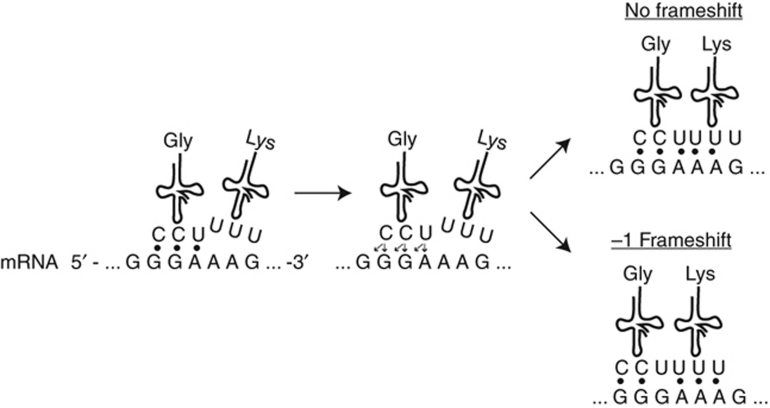

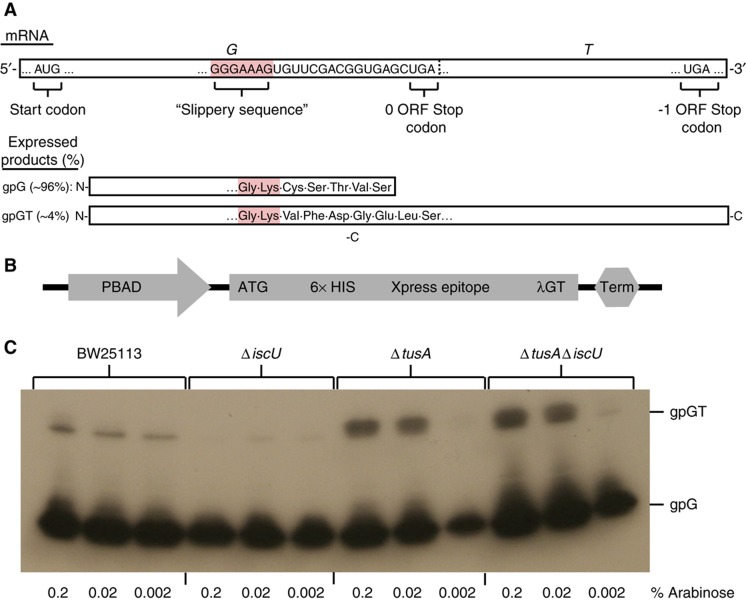

During PRF, the translational machinery slips backward or forward by one nucleotide while decoding a so-called ‘slippery sequence,’ a heptanucleotide sequence of the form XXXYYYZ in the mRNA transcript (Figure 1). Outside of PRF, frameshifting is a rare event, occurring fewer than 5 × 10−5 times per codon (Kurland, 1992). PRF can increase the occurrence of frameshifting by several orders of magnitude, depending on the slippery sequence itself as well as on the presence or absence of adjacent secondary structures that favor translational pausing and increase frameshift frequency (Gesteland and Atkins, 1996). In many instances of PRF, slippage causes the translational machinery to bypass a stop codon just downstream of the slippery sequence, resulting in the expression of an elongated protein (Gesteland and Atkins, 1996). Therefore, normal expression from these transcripts results in two products, a shorter product based on the initial translation frame plus a longer product, whose ratio depends on the frequency of slippage and is thought to have evolved to a value optimized for virus production (Shehu-Xhilaga et al, 2001; Dulude et al, 2006).

Figure 1.

Programmed ribosomal frameshifting. Schematic of a −1 programmed ribosomal frameshift. P-site tRNA slips in the −1 direction at the ‘slippery sequence.’

PRF is an evolutionarily conserved phenomenon observed in a range of viruses, from bacteriophage to notable human pathogens (Table I; Baranov et al, 2002). For example, in HIV, the Gag to Gag-Pol expression ratio is regulated by PRF and is necessary for the proper loading of reverse transcriptase into the new viral capsids; disturbing this ratio can inhibit viral replication (Shehu-Xhilaga et al, 2001; Dulude et al, 2006). The role of PRF in the SARS life cycle is less clear, but is necessary for expression of its RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Plant et al, 2010). In Escherichia coli bacteriophage lambda, PRF regulates the expression of proteins gpG and gpGT (Levin et al, 1993). As lambda phage genes G and T lie between its major tail gene (V) and its tape measure gene (H), they are thought to have a role in tail formation (Xu, 2001). However, proteins gpG and gpGT do not make up any of the final tail structure (Levin et al, 1993), and thus may act as chaperones or scaffolds for gpH, assisting in the assembly of the tail shaft around the tape measure protein (Xu, 2001).

Table 1. Viruses dependent on programmed ribosomal frameshifting.

| Virus | Slippery sequence | Region |

|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 | UUUUUUA | gag/gag-pol |

| SARS-CoV | UUUAAAC | ORF1a/1b |

| Lambda phage | GGGAAAG | G/GT |

Reading-frame maintenance is a common function of tRNA modifications (Urbonavicius et al, 2001). tRNAs contain upwards of 80 known modified nucleosides (Limbach et al, 1994), and many of these are strongly conserved across species (Sprinzl and Vassilenko, 2005). However, their loss is generally not lethal (Alexandrov et al, 2006; Phizicky and Hopper, 2010). In E. coli, four tRNA modifications require the addition of a thiol moiety and are made via two functionally distinct mechanisms (Nilsson et al, 2002). The first mechanism requires proteins that contain iron-sulfur (Fe-S) clusters and includes 2-thiocytidine formation at position 32 and methylthio formation of ms2i6A at position 37 (Jager et al, 2004; Pierrel et al, 2004). The second mechanism is independent of Fe-S clusters and includes 4-thiouridine at position 8 and 2-thiouridine at position 34 (Ikeuchi et al, 2006). For each of these modifications, sulfur is sequestered by E. coli's primary cysteine desulfurase, IscS. Sulfur is then used for one of these four tRNA modifications or for Fe-S cluster biosynthesis. In addition to their roles in tRNA modification, Fe-S clusters are critical cofactors involved in many cellular processes including respiration, central metabolism, environmental sensing, RNA modification, DNA repair, and DNA replication (Py and Barras, 2010).

We previously identified two pathways downstream of IscS in a screen to identify E. coli genes with a significant effect on lambda phage replication (Maynard et al, 2010). Specifically, lambda phage replication was inhibited following deletion of several members of the 2-thiouridine synthesis (TUS) pathway leading to 2-thiouridine modification of tRNALys/Glu/Gln, a pathway independent of Fe-S cluster biosynthesis. Conversely, we found that knocking out members of the Fe-S cluster biosynthesis (ISC) pathway enhanced lambda replication.

The current investigation was therefore motivated by this overarching question: how do the host's TUS and ISC pathways control viral replication? We were particularly intrigued by the possibility that these pathways interact. Furthermore, the substantial evolutionary conservation of both host genes and viral PRF mechanism strongly suggested that our observations would have relevance beyond E. coli and lambda phage. Our current observations shed light on a complex network that extends from host metabolism and tRNA modification to viral translational regulation and finally to virion production. We find that 2-thiouridine hypomodification of tRNALys/Glu/Gln causes increased translational frameshifting, changing the ratio of the critical lambda phage proteins gpG and gpGT. We also show that IscU is linked to gpG and gpGT expression by competitive inhibition of the TUS pathway. Knocking out core members of the ISC pathway increases lambda phage replication by relieving competition for sulfur, allowing the TUS pathway to increase the rates of 2-thiouridine formation, thus reducing frameshifting. Targeting tRNA modifications to alter frameshifting rates, to which viral structural proteins are likely to be uniquely sensitive, presents a novel antiviral strategy.

Results

Viral replication can be slowed by deletion of TUS and accelerated by deletion of ISC genes

In a previous genome-wide screen (Maynard et al, 2010), we found that plates growing TUS pathway deletion strains (ΔtusA, ΔtusE, and ΔmnmA) infected with lambda phage produced plaques of an unusually small diameter compared with wild-type (WT) E. coli. In contrast, several ISC pathway deletion strains (ΔiscU, ΔhscA, and ΔhscB) produced abnormally large diameter plaques compared with WT.

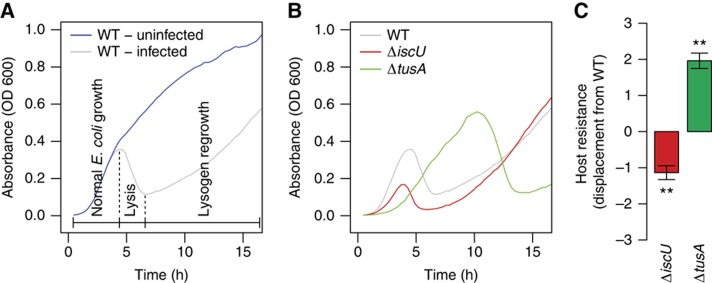

We investigated viral replication in these strains more thoroughly by culturing each strain in liquid media, in the presence and absence of virus. Without phage, WT E. coli grew in exponential phase for several hours, slowing and reaching stationary phase as available nutrients decreased (Figure 2A, blue line). In the presence of lambda phage, the culture exhibited three phases (gray line). First, the culture underwent exponential growth similar to the uninfected culture. After ∼6 h in the WT strain, viral lysis overtook the culture and the culture began to clear (lytic phase). Lambda phage is a temperate phage with both lytic and lysogenic life cycles (Landy and Ross, 1977); as a result, after a roughly 3-h lytic phase, lysogenized bacterial population growth took over the culture.

Figure 2.

Dynamics of lambda phage infection. (A) A typical trace of a WT E. coli culture infected with lambda phage. Several hours after infection, lysis begins to outpace E. coli growth and absorbance begins to decrease. Regrowth is due to the lambda lysogen population. (B) Infection dynamics of infected ΔiscU and ΔtusA cultures were compared. (C) The displacement from the WT growth curve. In (C), the bars indicate the 95% confidence interval (CI). For (A) and (B), absorbance was recorded over the course of 16 h for three biological replicates with four technical replicates for each biological replicate (**P<0.01, P-values were calculated using an independent two-sample t-test).

The time courses of lambda phage infection of the tusA and iscU knockout strains (the first members of the TUS and ISC pathways, respectively) differed significantly from that of WT. The ΔiscU culture entered the lytic phase very quickly (red curve, Figure 2B), while the infected ΔtusA strain grew in exponential phase substantially longer than the WT strain, leading to a higher turbidity before the lytic phase occurred (green curve). We therefore decided to classify strains that entered the lytic phase earlier as more susceptible to viral infection (red) and those that entered the lytic phase later as less susceptible (green). This susceptibility classification was consistent with our earlier plaque assay experiments (Maynard et al, 2010).

We then defined a metric to compare the resistance of different strains with infection with phage lambda. One useful way to summarize the information contained in a time course is to consider each experiment as a vector in n-dimensional space, where n is the number of time points taken. In earlier work, we found that it was useful to normalize these infection time course experiment vectors by the growth rate (Maynard et al, 2010). However, we have since found that bacterial growth and viral growth are tightly linked, and our attempts to numerically correct for or eliminate the effect of bacterial growth rate often distorted the raw data. Bacterial growth is therefore an important (but not sufficient) consideration in classifying our strains.

As a result, we determined our new metric simply by calculating the Euclidean distance between the knockout and WT strain time course vectors under infection conditions. Combining this distance with our susceptibility classification, we obtain a displacement vector that points in a negative direction for strains that are less resistant to virus and a positive direction for more resistant strains. The displacement vector, which we call the ‘host resistance’, enables us to compare the magnitude and direction of each strain relative with the WT strain and with each other. For example, the ΔiscU strain is significantly less resistant to viral infection than the WT strain, while the ΔtusA strain is more resistant (Figure 2C).

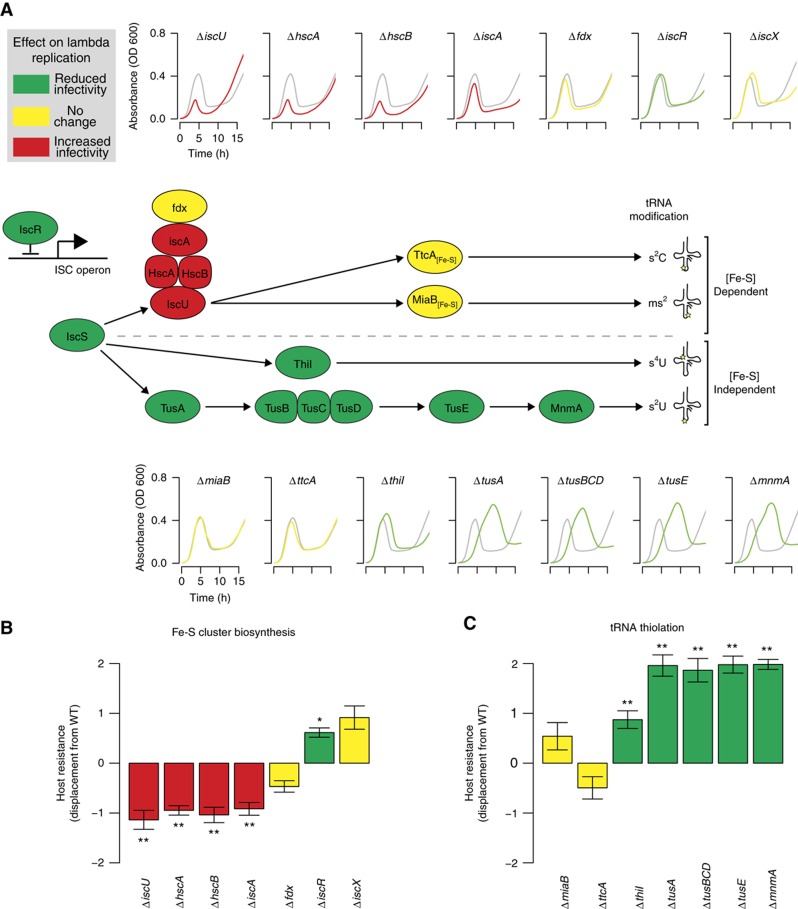

Deletion mutants in Fe-S biosynthesis and tRNA thiolation exhibit altered viral infection dynamics

As both the TUS and ISC pathways are linked to sulfur metabolism through IscS, we wondered about the interplay between these two pathways and what might be the mechanistic basis for their effect on lambda replication. We began our investigation by examining the impact of other known ISC and TUS pathway members on lambda phage replication (Figure 3A; see Supplementary Figure 1 for line plots of individual replicates). First, we investigated the effect on lambda phage replication of several genes associated with Fe-S cluster biosynthesis. We performed infection time courses of ΔiscU and other strains deficient in members of the iscRSUA-hscBA-fdx-iscX operon (hscA, hscB, iscA, iscR, fdx, and iscX). The slow growth of the iscS deletion strain made it impossible to assess infection dynamics and was not included in the analysis. The ΔiscU, ΔhscA, and ΔhscB strains all exhibited very similar infection dynamics, clearing the culture significantly before WT (Figure 3A, top row; Figure 3B). IscU is the primary scaffolding protein used for Fe-S cluster biosynthesis (Urbina et al, 2001), and HscA and HscB are accessory proteins that help transfer Fe-S clusters to apoproteins (Bonomi et al, 2008) The ΔiscA strain exhibited increased replication efficiency, but less than the hscA, hscB, and iscU gene deletions (Figure 3A and B). IscA assists in Fe-S cluster biosynthesis by shuttling iron to IscU (Yang et al, 2006).

Figure 3.

The effects of Fe-S cluster and tRNA thiolation deletions on lambda phage infection dynamics. (A) Cell-culture dynamics following infection overlay the uninfected control data (WT alone, gray). Small arrows in the cartoon indicate sulfur transfer and the large bent arrow indicates expression of the ISC operon. (B) Displacement from the WT strain for ISC operon members (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, bars indicate 95% CI, P-values were calculated using independent two-sample t-test). (C) Comparison of the displacement from the WT strain for tRNA thiolation pathway members. Source data is available for this figure in the Supplementary Information.

Deletion strains for the remaining three genes in the operon, iscR, fdx, and iscX, displayed little if any change in viral infection dynamics from WT (Figure 3A and B). The roles of Fdx and IscX in Fe-S cluster biosynthesis are not known (Takahashi and Nakamura, 1999), but IscR is the transcriptional repressor of the ISC operon and its active form includes an Fe-S cluster (Schwartz et al, 2001). Interestingly, lambda phage replication is slightly but significantly hindered in the iscR knockout strain (Figure 3A and B). Taken together, these observations suggest that ISC pathway members IscU, HscA, HscB, IscA, and possibly IscR have a more significant role in lambda phage infection than Fdx or IscX, and that their WT function helps to restrict phage growth.

We next determined how deletion of tRNA thiolation enzymes affected viral susceptibility of the host. We began with the Fe-S cluster-containing enzymes encoded by miaB and ttcA. MiaB is responsible for methylthio formation of ms2i6A at position 37 in tRNAPhe (Pierrel et al, 2004); a sulfur donor for MiaB has not been identified. TtcA catalyzes the 2-thiocytidine modification at position 32 of tRNAArg(ICG), tRNAArg(CCG), tRNAArg(mnm5UCU), and tRNASer(CGU) (Jager et al, 2004). ΔttcA strains displayed doubling times equivalent to WT E. coli (Figure 3A, bottom), and little is known about the functional consequences of modification. Strains lacking either of these genes showed no effect on lambda infection dynamics (Figure 3A, bottom; Figure 3C). In contrast, deletion strains for the two Fe-S cluster-independent tRNA thiolation enzymes ThiI and MnmA displayed a significant increase in viral resistance versus the WT strain (Figure 3A, bottom; Figure 3C). Sulfur is transferred to ThiI through direct binding of IscS (Kambampati and Lauhon, 2000), and ThiI then transfers the sulfur to s4U8 of tRNAPhe. Lambda replication in the ΔthiI strain was mildly but significantly inhibited (Figure 3A, bottom; Figure 3C).

The ΔmnmA strain exhibited the most dramatic effect on viral infection of all the strains associated with tRNA thiolation. MnmA catalyzes 2-thiouridination at position 34 of several tRNAs (Kambampati and Lauhon, 2003). Sulfur is supplied to MnmA through the TUS pathway, beginning with the direct binding of IscS by TusA (Ikeuchi et al, 2006). The ΔmnmA strain underwent infection dynamics (Figure 3A, bottom; Figure 3C) very similar to the upstream TUS pathway gene deletion strains we characterized in a previous study (Maynard et al, 2010), including ΔtusA, ΔtusBCD, and ΔtusE. All members of the TUS pathway had a strong, significant, and similar effect on lambda replication (Figure 3A and C), leading us to conclude that Fe-S cluster-independent tRNA thiolation in E. coli exerts a significant effect on lambda phage replication through the TUS pathway and, to a lesser degree, ThiI.

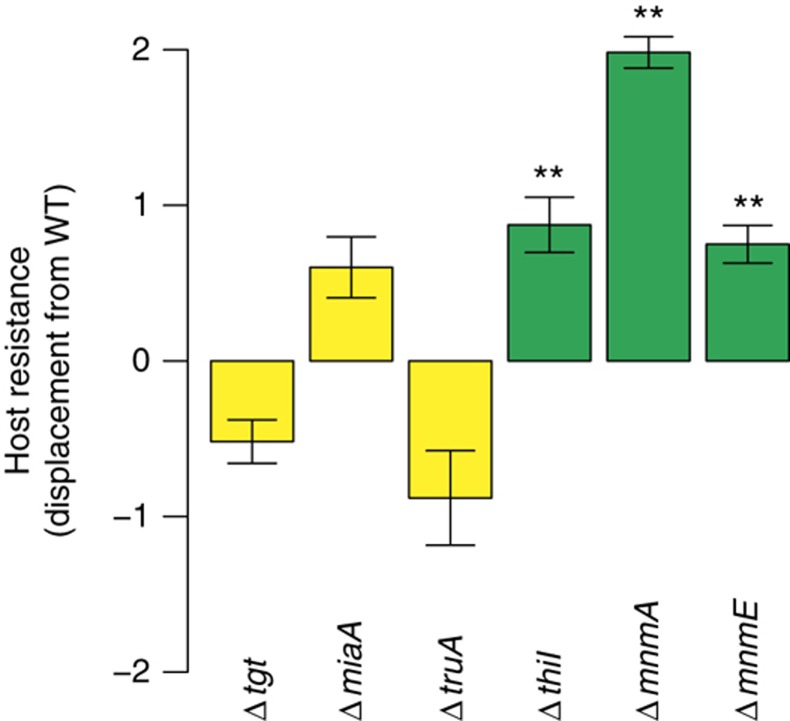

Changes in tRNA modification and frameshifting propensity inhibit viral replication

Based on the preceding data and a previous observation of increased frameshifting in ΔmnmA strains (Urbonavicius et al, 2001), we hypothesized that reduced lambda replication in the TUS knockouts was due to increased frameshifting during lambda protein synthesis as a result of the decreased tRNA modification. To test this hypothesis, we generated infection curves for several deletion mutants that have been shown to affect frameshifting by loss of tRNA modification, including tgt, truA, miaA, thiI, and mnmE (Urbonavicius et al, 2001). We infected deletion strains for these genes with lambda phage and determined their susceptibility to infection (Figure 4; see Supplementary Figure 2 for line plots of individual replicates). Δtgt, ΔmiaA, and ΔtruA exhibited no significant affect on lambda phage replication, suggesting that the tRNA modifications from these enzymes have no role in lambda phage replication. The remaining knockout strains displayed significant changes in lambda phage's ability to infect the host, including ΔthiI, ΔmnmA (Figures 3 and 4), and ΔmnmE (Figure 4). Intriguingly, MnmE performs a methylaminomethyl modification on carbon 5 of the same tRNA species and nucleoside targeted by MnmA (Elseviers et al, 1984), suggesting that the antiviral properties of the TUS pathway knockouts may be due to specific tRNA modifications instead of to general translational fidelity issues.

Figure 4.

Displacement vector comparisons for mutants in E. coli genes known to affect frameshifting. Comparison of the displacement from the WT for deletion mutants in genes known to affect frameshifting (**P<0.01, bars indicate 95% CI, P-values were calculated using independent two-sample t-test). Green, reduced infectivity; yellow, no effect on infectivity. Source data is available for this figure in the Supplementary Information.

Codon usage bias does not underlie differential infection dynamics

Host-preferred codon usage is common among many viruses and their hosts (Kunisawa et al, 1998; Lucks et al, 2008). We wondered whether the lambda genome used the codons whose tRNAs are modified by the mnmA, and mnmE gene products preferentially with respect to E. coli. The tRNA species modified by MnmA and MnmE decode the lysine, glutamic acid, and glutamine codons (Kambampati and Lauhon, 2003); we examined the codon usage for lysine, glutamic acid, and glutamine in lambda phage and in E. coli for synonymous codon usage bias. Lambda phage encodes lysine 748 times (65% AAA and 35% AAG), glutamic acid 900 times (57% GAA and 43% GAG), and glutamine 576 times (20% CAA and 80% CAG), with similar biases in E. coli (Table II). This similarity in codon usage does not support the hypothesis that lambda phage protein synthesis is any more impaired in strains harboring hypomodified 2-thiouridine tRNAs than its host.

Table 2. Codon usage in E. coli and lambda phage.

| Amino acid | Codon | E. coli: fraction (number) | Lambda phage: fraction (number) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysine | AAA | 0.76 (46 116) | 0.65 (486) |

| AAG | 0.24 (14 174) | 0.35 (262) | |

| Glutamic acid | GAA | 0.69 (54 431) | 0.57 (515) |

| GAG | 0.31 (24 629) | 0.43 (385) | |

| Glutamine | CAA | 0.35 (21 121) | 0.20 (117) |

| CAG | 0.65 (39 836) | 0.80 (459) |

Thiolation of tRNALys (UUU) and frameshifting via PRF are linked through a genetic network

Since we thought it unlikely that lambda phage replication was being significantly affected by general reading frame maintenance in the TUS pathway knockout mutants, we turned instead to specific tRNA modifications that could explain our observations of an increase in viral resistance. In particular, our attention was drawn to PRF as a specific instance of frameshifting that could be particularly sensitive to changes in frameshifting frequency.

In lambda phage, PRF occurs during translation of the lambda phage GT region, which encodes two possible protein products, either gpG or gpGT; expression of gpGT depends on ribosomal frameshifting at the slippery sequence GGGTTTG (Levin et al, 1993). This sequence encodes the dipeptide Gly-Lys in both the 0 open reading frame (ORF; GGT-TTG) and the −1 ORF (GGG-TTT). In the 0 ORF, which is maintained ∼96% of the time, gpG is expressed (Figure 5A); and in the remaining cases, the ribosomal machinery reaches the slippery sequence and slips back one base pair. As a result, the stop codon for gpG, immediately downstream of the slippery sequence, is bypassed and the larger gpGT product is produced. Interestingly, both the lysine codons TTG (0 ORF) and TTT (−1 ORF) are decoded by the same tRNALys (UUU), a target of MnmA and MnmE. We therefore wondered whether TUS pathway gene deletion strains would exhibit an altered rate of frameshifting and consequently a change in the ratio of gpG to gpGT.

Figure 5.

Lambda phage proteins gpG and frameshift product gpGT. (A) Schematic of lambda phage's frameshifting region in G and T. (B) Schematic of the arabinose-inducible region of the pBAD-λGT vector. (C) Immunoblotting of pBAD-λGT in BW25113, ΔiscU, ΔtusA, and ΔtusAΔiscU strains. We induced expression of the pBAD-λGT transcript with 0.2, 0.02, or 0.002% L-arabinose for 2 h and assessed the gpG and gpGT protein levels by immunoblotting against the Xpress Epitope tag. We found a decrease in gpGT levels in ΔiscU and an increase in ΔiscU and ΔtusAΔiscU.

To monitor gpG and gpGT expression in E. coli, we created a plasmid for the inducible synthesis of these proteins (pBAD-λGT; Figure 5B). We PCR amplified the GT region of the lambda genome and introduced this region behind an arabinose-inducible promoter, to control expression of the transcript, and the Xpress Epitope C-terminal tag, to facilitate detection by immunoblotting. We then transformed WT, ΔtusA, ΔiscU, and ΔtusAΔiscU strains with pBAD-λGT. Deletion of the iscU gene led to abrogation of frameshifitng, whereas frameshifting frequency increased in both the ΔtusA and the ΔtusAΔiscU strains relative to WT (Figure 5C). We also tested frameshifting frequency for additional strains (ΔmnmA, ΔthiI, ΔmiaB, ΔttcA, ΔhscA, ΔhscB, Δfdx, ΔiscA, and ΔiscR) and found frameshifting levels to be consistent with infection dynamics (see Supplementary Figure 3). We interpret these results to signify that the decreased thiolation of tRNALys (UUU) in the TUS pathway knockout strains leads to an increase in frameshifting at the slippery sequence.

Competitive binding of IscU and TusA for IscS binding integrates sulfur metabolism and infection dynamics

Surprisingly, the ΔiscU strain exhibited markedly reduced gpGT levels relative to the WT strain (Figure 5C), strongly indicating that both IscU and TusA act on lambda phage replication by altering the gpG:gpGT ratio. Furthermore, our observation that the miaB and ttcA deletion strains exhibited normal lambda phage replication (Figure 3) suggested that IscU does not act directly through thiolation of specific tRNA modifications. How, then, does IscU influence viral replication independent of direct tRNA modification?

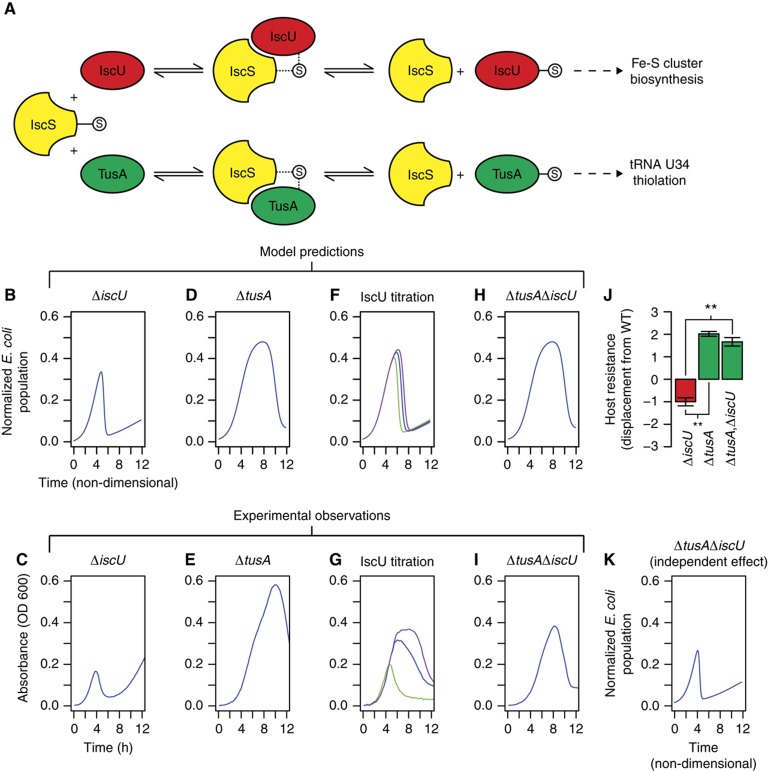

One possible answer is that IscU competes with TusA to bind IscS. Recent X-ray crystallography studies showed that IscU and TusA bind IscS at distinct but adjacent locations (Shi et al, 2010). Superposition of the IscU and TusA structures indicated a spatial overlap between the volume occupied by TusA and IscU when bound to IscS. Furthermore, three-way pull-down experiments demonstrated that IscS may bind either TusA or IscU individually, but not both at the same time (Shi et al, 2010). To further explore the possibility that thiolation of tRNALys (UUU) is affected by competition between TusA and IscU for sulfur transfer from IscS, we constructed a mathematical model of IscU and TusA binding to IscS (Figure 6A). Our model consisted of a set of equilibrium and mass conservation relationships. In this case, the model parameters had either been previously measured or were not difficult to estimate based on existing data (Urbina et al, 2001; Taniguchi et al, 2010). Our model predicts the relative amount of U34 thiolation from the TUS pathway for a specified amount of IscU.

Figure 6.

Competitive binding of IscU and TusA to IscS: theory and experiment. (A) A schematic of our competitive binding model. IscS may bind and transfer sulfur to either IscU or TusA, leading to production of Fe-S cluster biosynthesis or thiolated tRNA, respectively. (B–I) Comparison of model predictions (top row) and experimental observations (bottom row) of infection time courses. The genetic perturbations include the deletion mutant strains ΔiscU (B, C) and ΔtusA (D, E), titration of expression from iscU (F, G) and the double deletion mutant strain ΔtusAΔiscU (H, I). (J) The host resistance metric calculated for the ΔtusA, ΔiscU, and ΔtusAΔiscU deletion mutant strains (**P<0.01, bars indicate 95% CI, P-values were calculated using independent two-sample t-test). (K) The prediction of an alternate model—independent effect of IscU and TusA on viral biosynthesis—for an infection time course in the ΔtusAΔiscU background. Comparison of this plot with (H) and (I) indicates that the competitive binding model is better able to account for the experimental observations. Source data is available for this figure in the Supplementary Information.

We combined this protein binding model with our previous mathematical model of E. coli infection by lambda phage (Maynard et al, 2010). Our earlier model predicts the E. coli time course dynamics of lambda phage infection based on three parameters: the fraction of infections that are lytic instead of lysogenic, the rate of infection, and the burst size (how many functional progeny are released upon lysis). To integrate these two models, we related U34 thiolation (the output of the protein binding model) to the burst size (input for our infection model). We were thus able to explore the effect of changing the IscU or TusA concentration on the production of functional phage and the resulting infection time course. We first tested the integrated model's ability to predict the outcome of deleting iscU or tusA, and in both cases the model was able to capture the infection time course (Figure 6B–E; see Supplementary Figure 4 for line plots of individual replicates). We also considered titration of IscU experimentally as well as computationally by introducing an IPTG-inducible iscU gene construct into a ΔiscU strain and determining the infection time courses under various IPTG concentrations. The effect of IscU titration was predicted well by our competitive inhibition model (Figure 6F and G; see Supplementary Figure 4 for line plots of individual replicates).

Finally, we considered the case of a double deletion of tusA and iscU. The competitive inhibition model suggested that the double mutant would behave in a manner similar to a ΔtusA strain under infection conditions (Figure 6H). Again, this prediction agreed with the experimental time course (Figure 6I and J; see Supplementary Figure 4 for line plots of individual replicates), as well as our experimental observation that the ratio of gpGT to gpG in the double mutant was similar to that observed in the ΔtusA strain, but not in the ΔiscU strain (Figure 5C).

As a control, we compared the predictions of the competitive inhibition model with those of the alternative hypothesis that IscU and TusA influence viral infection independently. This hypothesis required some relatively simple modifications in the equations and parameters of our competitive binding model (Materials and methods). Our independent effect model was able to capture the results of tusA deletion, iscU deletion, and IscU titration as accurately as the competitive inhibition model (data not shown). However, the independent effect model was not able to predict the behavior of the double knockout strain (Figure 6K).

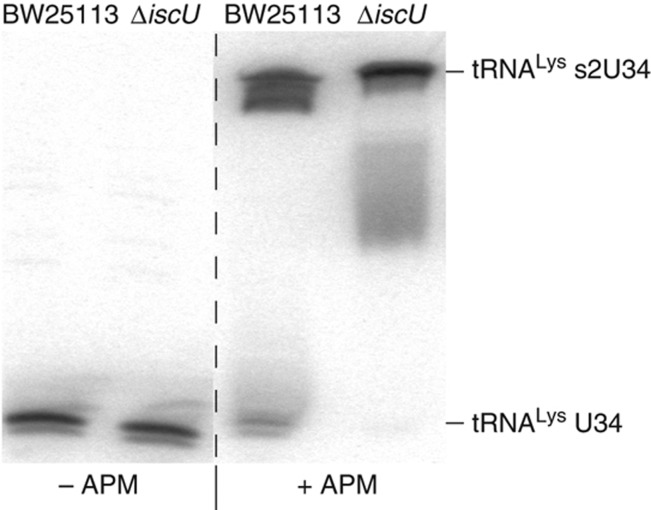

Our competitive inhibition model predicts that the removal of IscU, one of TusA's primary competitors for sulfur, will cause an increase in the fraction of 2-thiolation modified U34 tRNALys(UUU) relative to BW25113. To directly measure the fraction of thiolated tRNALys(UUU), we performed an [(N-Acryloylamino)phenyl] mercuric chloride (APM) northern blot (Figure 7), which specifically retards the migration of the thiolated tRNA fraction (Igloi, 1988). We found a small fraction of hypomodified tRNALys in BW25113, and as predicted by the competitive inhibition model, loss of IscU in the ΔiscU strain decreased this fraction even further. We therefore conclude that our competitive inhibition model, but not our independent effect model, is sufficient to explain the effect of TUS and ISC pathway knockouts on lambda phage replication.

Figure 7.

APM northern blot of tRNALys(UUU) in BW25113 and ΔiscU. tRNA northern blots for tRNALys(UUU) in urea denaturing gels with and without APM. tRNA extracts were probed to determine the thiolated fraction of U34 in BW25113 and ΔiscU. A relative shift in the APM+ gel reflects the fraction of 2-thiolated U34 tRNALys (tRNALys s2U34). A small but detectable level of hypomodified tRNALys (tRNALys U34) was seen in BW25113 but was essentially undetectable in ΔiscU.

Discussion

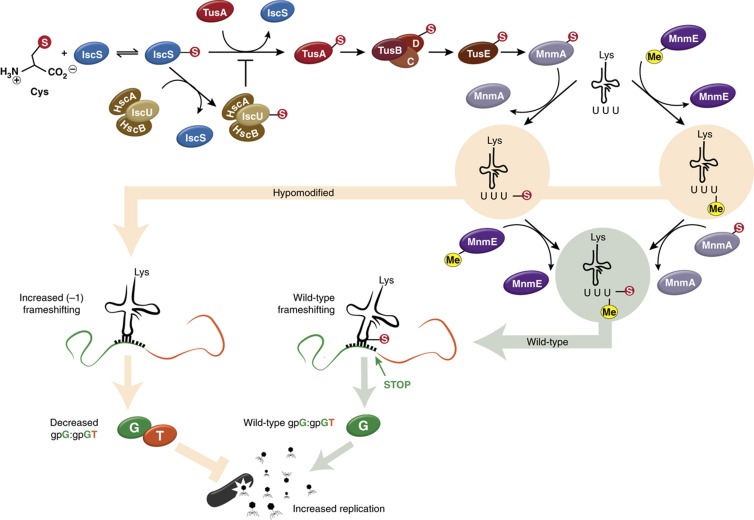

Taken together, our observations suggest the existence of a complex network that links sulfur metabolism, tRNA modification, competitive binding, and PRF-based regulation of viral protein expression with host susceptibility to viral infection (Figure 8). TusA obtains sulfur from the cysteine desulfurase IscS, and passes it along the TUS pathway for eventual modification of tRNALys(UUU) at U34. The fraction of tRNALys(UUU) that undergoes this modification influences the frequency of PRF in lambda phage due to its role in decoding part of the slippery sequence within its GT region. Although lambda phage requires both gpG and gpGT for normal replication, the gpG:gpGT ratio must be kept high. Deletion of any member of the TUS pathway prevents modification of tRNALys(UUU), and subsequently increases frameshifting, both decreasing the gpG:gpGT ratio and lambda phage production.

Figure 8.

A network linking host resistance to viral infection to sulfur metabolism, tRNA modification, PRF, and competitive protein binding. IscS obtains sulfur from L-cysteine and passes it to either TusA or IscU. From TusA, the TUS pathway leads to thiolation by MnmA of tRNALys (UUU) U34, which is also methylated by MnmE. During viral infection, the WT amount of modified tRNA leads to normal translation (and frameshifting) for the viral G and T genes, and consequently a favorable ratio of gpG:gpGT and virion production. Hypomodification of tRNALys (UUU), whether by deletion of mnmE or the TUS pathway genes, or by overexpression of IscU, leads to increased frameshifting during translation of G and T. This increase in frameshifting leads to more gpGT expression and subsequently, a lower gpG:gpGT ratio and decreased virion production.

In the presence of HscA, HscB, and (less critically) IscA, IscU binds IscS more strongly than TusA (Shi et al, 2010) and is therefore able to outcompete TusA for sulfur. When IscU, HscA, HscB, or IscA is removed from the system, TusA obtains more sulfur than normal, leading to hypermodification of tRNALys(UUU), a decrease in frameshifting, and increases in the gpG:gpGT ratio and lambda phage production. Previous investigations in B. subtilis reported that disrupting the function of IscU affects several levels of tRNA modifications, including an increase in 2-thiolation of U34 (Leipuviene et al, 2004); our observations suggest that in the case of tRNALys(UUU), this effect is a result of an increase of sulfur flux through the TUS pathway (Figures 5C, 6K, and 7). Removal of the transcriptional repressor IscR leads to an increase in protein production from the ISC operon (Schwartz et al, 2001), reducing the amount of sulfur available to TusA. This competition effect depends on an intact TUS pathway, which is why the ΔtusAΔiscU deletion mutant expresses a phenotype similar to the ΔtusA strain.

This model fits our observations well, but unresolved issues remain, most notably the role of ThiI in viral infection. ThiI would seem to be another possible competitor for sulfur from IscS (Figure 2A). However, the ΔthiI strain exhibited decreased lambda replication, albeit somewhat less strongly than the TUS pathway deletion strains. One clue to this mystery may reside with the CyaY protein, which is thought to be an iron donor for Fe-S cluster assembly, forming a ternary complex with IscU and IscS (Shi et al, 2010). The binding site for ThiI on IscS overlaps substantially with CyaY (Shi et al, 2010), and it is conceivable that in the absence of ThiI, CyaY is able to interact more efficiently with IscU, either stabilizing the IscS-IscU-CyaY complex or assisting sulfur transfer to IscU. In either case, deleting thiI may increase IscU's ability to compete with TusA for sulfur.

Our findings point to several novel antiviral strategies and targets. Although this work was performed using E. coli and phage lambda, many of the key elements of the network we describe are conserved in other systems, in both in host and the virus. Both Fe-S clusters and tRNA modifications are ubiquitous in cells (Limbach et al, 1994; Py and Barras, 2010) and PRF is a common viral translational strategy (Gesteland and Atkins, 1996). Indeed, frameshifting has already been identified as a potential target in HIV, but efforts to target the gag-pol mRNA secondary structure have been challenging (Hung et al, 1998). Our results point to upstream (e.g., tRNA modifying enzymes) and even indirect targets (e.g., Fe-S cluster biosynthesis pathways), which can just as potently alter infection and in some cases are tunable (Figure 6G). We therefore anticipate that our observations and inferences may have broad relevance to understanding other infections, including viral infection of humans.

Materials and methods

Strains

The E. coli strains used in this study were all taken or derived from the Keio Collection, a comprehensive library of single gene deletion strains (Baba et al, 2006). BW25113 is the parental strain used for the construction of the Keio Collection. Lambda phage was obtained from the ATCC (23724-B2). The ΔtusBCD strain was generated previously (Maynard et al, 2010), and the ΔtusAΔiscU double knockout strain was constructed according to the Datsenko-Wanner method (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000). Primer sequences are available upon request. The lambda GT reporter strain was constructed using a pBAD/His A plasmid (Invitrogen, Cat# V430-01). The lambda phage GT region was amplified via PCR (primers: 5′-cacattctcgagatgttcctgaaaaccgaatca-3′ and 5′-gtgtaaaagcttgccataccggactcctcct-3′). The amplified GT region and pBAD/His A plasmid were cut with XhoI and HindIII. BW25113, ΔtusA, ΔiscU, and ΔtusAΔiscU strains were transformed with the arabinose-inducible lambda phage GT reporter construct (Figure 5B). A chemically inducible ΔiscU strain was created by transforming ΔiscU with pCA24N-iscU isolated from the ASKA collection (Kitagawa et al, 2005).

Cell culture quantification

We monitored infection dynamics using an incubated plate reader (Perkin-Elmer Victor3, 2030-0030) under growth conditions described previously (Maynard et al, 2010). Exponentially growing cells were normalized to 0.1 OD 600 nm. Fifteen microliters of 0.1 OD E. coli and 15 μl of ∼104 plaque forming units (p.f.u.)/ml lambda stock were added to 170 μl of LB medium in 96-well plates, representing a multiplicity of infection of ∼2 × 10−4 p.f.u./bacteria. Each plate contained four technical replicates of infected and uninfected samples. The plate reader measured the absorbance of the culture approximately every 17 min for 16 h. Each plate contained a sample of BW25113 for between-plate normalization. Three independent biological replicates were performed for each strain.

Comparative metrics for time courses

Time courses were compared based on a useful displacement metric that includes a direction in addition to a distance. The distance was determined by calculating the Euclidean distance between the two time course vectors; the Euclidean distance between the recorded absorbances for each culture were calculated at each time point, and these distances were summed for all time points. For our purposes, the direction could only hold two values, +/−1. The positive value was associated with strains exhibiting increased resistance to viral infection, and the negative value was associated with increased susceptibility to viral infection. The direction was determined by the difference in the time it took a culture to reach its peak absorbance. For example, time courses with longer times to peak compared with BW25113 were considered to be displaced in a positive direction from BW25113. The displacement was then calculated as (direction) × (distance).

The Euclidean distance from BW25113 was measured for each biological replicate. Statistical significance was determined using a two-sample t-test comparing the Euclidian distances calculated for each biological replicate and its distance from BW25113 for each plate containing the strain being compared.

E. coli and lambda phage codon usage

Lambda phage ORFs were extracted from NCBI Reference Sequence NC_001416.1 (Enterobacteria phage lambda, complete genome) and codon usage was tallied.

Codon usage for WT E. coli (W3110) was determined from the Codon Usage Database (http://www.kazusa.or.jp/codon/).

Assaying lambda PRF

pBAD-λGT-transformed cells were cultured overnight at 37°C in LB and the appropriate antiobiotics. The cultures were diluted 1:50 into fresh LB the following morning and placed back in the shaker for 1 h. The culture was then split into 1 ml aliquots arabinose. Arabinose induction was performed for 2 h at 0.2, 0.02, and 0.002% arabinose, after which the samples were spun down in a table-top centrifuge at ∼20 000 g for 30 s. The media was aspirated and the pellets were frozen at −80°C. The samples were run on a 12% SDS–PAGE gel for 1.5 h at 80 V in Tris/glycine/SDS buffer. The protein was transferred onto a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane for 1 h at 100 V at room temperature. The membrane was washed for 30 s in TBST, then blocked with 5% milk blocking buffer for 1 h. The primary antibody (Anti-express antibody, Invitrogen) was diluted 1:5000 and incubated with the membrane blot overnight at 4°C. The membrane was washed five times for 10 min with TBST, followed by a 1-h incubation with a 1:5000 dilution of the secondary antibody (goat anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase). The membrane was washed five times for 5 min with TBST. Luminol reagent was used for chemiluminescence imaging (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc2048).

tRNA enrichment

BW25113 and ΔiscU were cultured overnight and diluted 1:100 to 20 ml in the morning. When the cultures reached ∼0.5 OD 600 nm, the samples were placed on ice. The cells were pelleted at 5000 r.p.m. for 5 min at 4°C and the supernatant was decanted. tRNA enrichment was performed using standard techniques. Briefly, the cell pellets were resuspended in 300 μl cold sodium acetate (0.3 M, pH 4.5, 10 mM EDTA) and transferred to eppendorf tubes. The samples were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. After thawing, 300 μl phenol:chloroform (pH 4.7) was added to the samples and vortexed four times for 30 s bursts with 1 min incubation on ice in between. The samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C in a table-top centrifuge at maximum speed. The top layer (aqueous phase) was transferred to a new tube and the acid phenol extraction procedure was repeated. After the aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube, the RNA was ethanol precipitated by adding three volumes of cold 100% ethanol and spinning at maximum speed for 25 min at 4°C. The RNA pellet was resuspended in 60 μl cold sodium acetate (0.3 M, pH 4.5) and precipitated again by adding 400 μl 100% ethanol and spinning at maximum speed for 25 min at 4°C. The supernatant was decanted and all traces of ethanol were removed. The RNA pellet was air dried on ice then resuspended in 100 μl cold sodium acetate (10 mM, pH 4.5).

APM northern blot

The APM northern blot was performed according to the protocol specified by Igloi (1988). Briefly, two 8 M Urea, 5% acrylamide gels were cast in 0.5 × TBE buffer. One gel contained 200 μl of 1 mg/ml APM (kindly supplied by Gabor Igloi) for 10 ml of gel. The gels were prerun for 30 min at 180 V in 0.5 × TBE. Approximately 2.5 μg of RNA (for each well) was then mixed with 2 × loading buffer and heated to 65°C for 3 min before being cooled on ice for 1 min. The gels were run for ∼45 min at 180 V. The RNA was transferred onto a nylon membrane using a semi-dry system for 1 h at 250 mA. The transfer buffer contained 0.5 × TBE supplemented with 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol. The RNA was then UV crosslinked to the nylon membrane. T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (PNK) was used to radiolabel 25 pmol of 32P ATP to 25 pmol of tRNALys(UUU) oligonucleotide probe for each blot. The oligonucleotide sequence used to probe tRNALys(UUU) was 5′-TGGGTCGTGCAGGATTCGAA-3′. Qiagen's Qiaquick Nucleotide Exchange Kit was used to remove free 32P ATP. The blots were incubated in 25 ml of prehybridization buffer (10 × Denhardt's, 6 × SSC, 0.1% SDS) at 42°C for 1 h. The labeled probe was heated to 95°C for 2–3 min before being added to the prehybridaztion buffer. The blots were hybridized at 42°C overnight. The next day, the blots were washed with high salt buffer (5 × SSC, 0.1% SDS) at 37°C for 20 min twice, followed by two washes with low salt buffer (1 × SSC, 0.1% SDS) at 42°C for 20 min. After the final wash, the blots were exposed to a phosphorscreen for 10 min.

Mathematical modeling

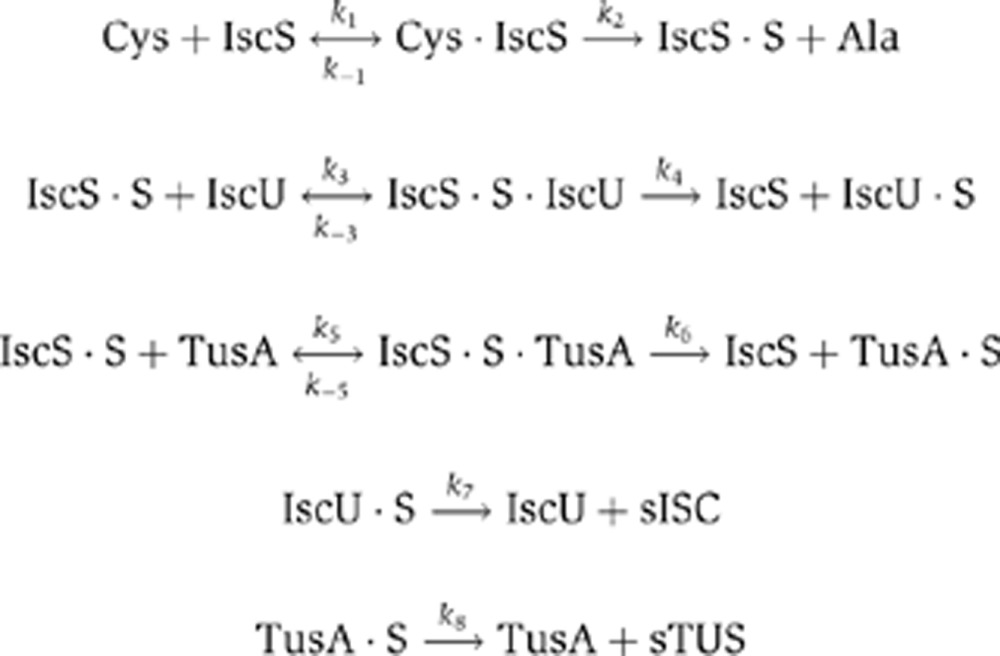

We constructed a competitive inhibition model based on the following assumed mechanisms: (1) the cysteine desulfurase IscS binds sulfur, converting cysteine to alanine in the process; (2) thiolated IscS presents sulfur to the apo forms of TusA and IscU; (3) TusA and IscU bind thiolated IscS with their respective affinities and obtain the sulfur; (4) TusA and IscU transfer the sulfur to their downstream pathways, represented as sTUS and sISC, respectively. The source code for our model can be downloaded from https://simtk.org/home/lambda-tus.

The reactions are as follows:

|

From these reactions we derived the following set of ordinary differential equations and mass conservation relationships:

|

Many of the parameter values were taken from the literature. Taniguchi et al (2010) reported values of ∼800 IscS proteins per cell and 450 IscU proteins per cell. Approximating the E. coli volume as 10−15 L, we obtained concentrations of 1.37 and 0.77 μM for IscS and IscU, respectively. Since TusA amounts were not reported, we estimated its concentration to be similar to but less than IscU 0.5 μM. An in-vitro study reported the Kd values of IscS and IscU to be 2 μM, and the kcat (k2 in the above equations) to be 8.5 per minute (Urbina et al, 2001). IscU displaced TusA in a three-way pull-down assay (Shi et al, 2010), from which we hypothesized that the Kd of TusA-IscU was 20% more than that of IscU-IscS. The cysteine concentration was chosen to be equal to the IscS concentration.

The forward rates of reaction were assigned as follows: k1=k3=k5=k7=k8=105, k4=k6=k−3. The reverse reaction rates were obtained by multiplying the corresponding forward rate by the appropriate dissociation constant. Gene deletion conditions were simulated by setting the pertinent concentration values to zero. IscU titrations were modeled by setting its concentration to 50, 100, and 150% of the WT amount.

Steady-state values of the sTUS parameter relative to WT were used to scale the amplification factor b in our previous non-dimensionalized predator-prey model (Maynard et al, 2010). We simulated infection dynamics with the following parameters:  , μ*=0.3, K*=0.4, ks=0.

, μ*=0.3, K*=0.4, ks=0.

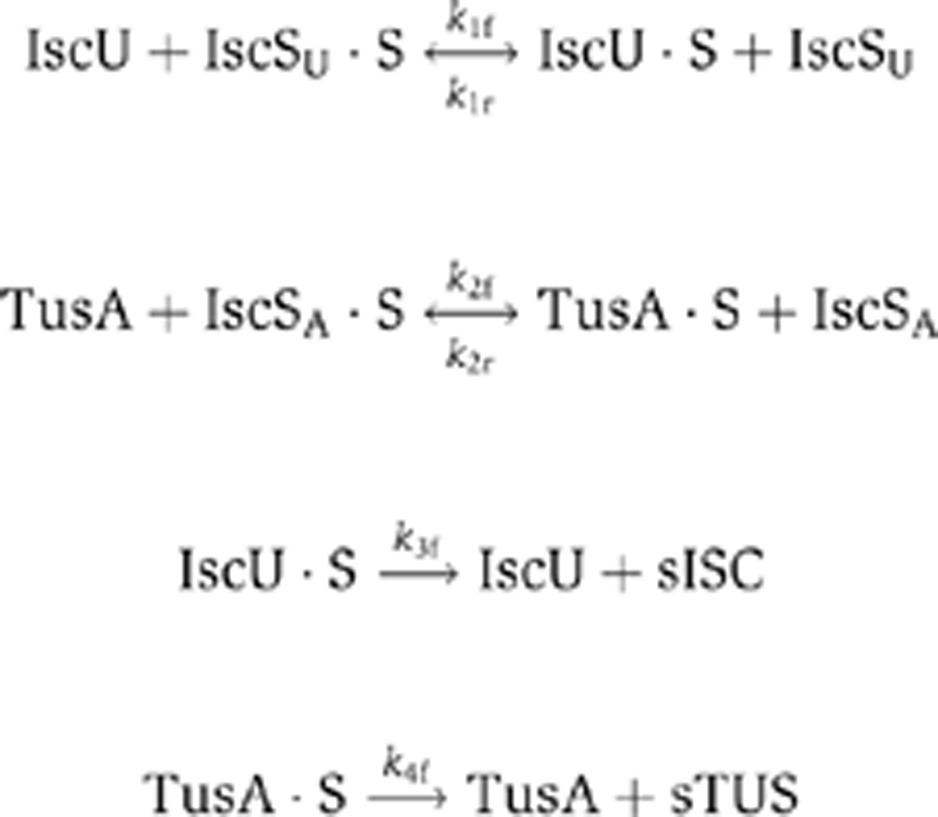

The independent effect model hypothesizes that there is no competition between IscU and TusA for sulfur. Thus, they each receive their own (equally sized) pool of thiolated IscS (iscSU·S belongs to IscU and iscSA·S belongs to TusA). The dissociation constants of both IscU and TusA with their respective pools of IscS were set to 2.7 μM. The concentrations of IscU and TusA were set to the same values as in the competitive model. The amount of thiolated IscS, however, was increased 100-fold to prevent it from being limiting. The reactions are as follows:

|

From these, we derived the following set of ordinary differential equations and constraints:

|

The kinetic parameters were specified as follows: k1f=k2f=k3f=k4f=105. Non-zero reverse rates were set to the product of the forward rate and the appropriate dissociation constant.

Steady-state values of the sTUS and sISC parameters relative to WT were used to scale the amplification factor b. Parameters for the predator-prey equation were  . We see that in both models, the WT burst rate is 20 and the tusA knockout burst rate is 10. Supplementary Table 1 describes the parameters used in the two models.

. We see that in both models, the WT burst rate is 20 and the tusA knockout burst rate is 10. Supplementary Table 1 describes the parameters used in the two models.

The standard ode23s solver in Matlab was used for solving the sulfur transfer equations. The ode45 solver was used to solve the predator-prey equations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge R Young as well as members of the Covert and Kirkegaard laboratories for helpful discussions; T Vora for editing the text; G Igloi for kindly supplying the APM; O’Reilly Science Art for assistance with the figures; and the funding this work through an NIH Director's Pioneer Award (1DP1OD006413) to MWC, a postdoctoral fellowship (1F32GM090545) to NDM, and a Benchmark Stanford Graduate Fellowship to DNM.

Author contributions: NDM, KK, and MWC conceived and designed the experiments. NDM and DNM performed the experiments. NDM, DNM, and MWC analyzed the data. NDM and DNM contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. NDM, DNM, KK, and MWC wrote the paper.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Alexandrov A, Chernyakov I, Gu W, Hiley SL, Hughes TR, Grayhack EJ, Phizicky EM (2006) Rapid tRNA decay can result from lack of nonessential modifications. Mol Cell 21: 87–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H (2006) Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Syst Biol 2, 2006 0008 ; DOI: 10.1038/msb4100050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranov PV, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF (2002) Recoding: translational bifurcations in gene expression. Gene 286: 187–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi F, Iametti S, Morleo A, Ta D, Vickery LE (2008) Studies on the mechanism of catalysis of iron-sulfur cluster transfer from IscU[2Fe2S] by HscA/HscB chaperones. Biochemistry 47: 12795–12801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datsenko KA, Wanner BL (2000) One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 6640–6645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulude D, Berchiche YA, Gendron K, Brakier-Gingras L, Heveker N (2006) Decreasing the frameshift efficiency translates into an equivalent reduction of the replication of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Virology 345: 127–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elseviers D, Petrullo LA, Gallagher PJ (1984) Novel E. coli mutants deficient in biosynthesis of 5-methylaminomethyl-2-thiouridine. Nucleic Acids Res 12: 3521–3534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale M Jr, Tan SL, Katze MG (2000) Translational control of viral gene expression in eukaryotes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 64: 239–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gesteland RF, Atkins JF (1996) Recoding: dynamic reprogramming of translation. Annu Rev Biochem 65: 741–768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harford JB (1995) Translation-targeted therapeutics for viral diseases. Gene Expr 4: 357–367 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmings-Mieszczak M, Steger G, Hohn T (1997) Alternative structures of the cauliflower mosaic virus 35 S RNA leader: implications for viral expression and replication. J Mol Biol 267: 1075–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung M, Patel P, Davis S, Green SR (1998) Importance of ribosomal frameshifting for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particle assembly and replication. J Virol 72: 4819–4824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igloi GL (1988) Interaction of tRNAs and of phosphorothioate-substituted nucleic acids with an organomercurial. Probing the chemical environment of thiolated residues by affinity electrophoresis. Biochemistry 27: 3842–3849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeuchi Y, Shigi N, Kato J, Nishimura A, Suzuki T (2006) Mechanistic insights into sulfur relay by multiple sulfur mediators involved in thiouridine biosynthesis at tRNA wobble positions. Mol Cell 21: 97–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager G, Leipuviene R, Pollard MG, Qian Q, Bjork GR (2004) The conserved Cys-X1-X2-Cys motif present in the TtcA protein is required for the thiolation of cytidine in position 32 of tRNA from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. J Bacteriol 186: 750–757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang SK, Krausslich HG, Nicklin MJ, Duke GM, Palmenberg AC, Wimmer E (1988) A segment of the 5′ nontranslated region of encephalomyocarditis virus RNA directs internal entry of ribosomes during in vitro translation. J Virol 62: 2636–2643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambampati R, Lauhon CT (2000) Evidence for the transfer of sulfane sulfur from IscS to ThiI during the in vitro biosynthesis of 4-thiouridine in Escherichia coli tRNA. J Biol Chem 275: 10727–10730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kambampati R, Lauhon CT (2003) MnmA and IscS are required for in vitro 2-thiouridine biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 42: 1109–1117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M, Ara T, Arifuzzaman M, Ioka-Nakamichi T, Inamoto E, Toyonaga H, Mori H (2005) Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (a complete set of E. coli K-12 ORF archive): unique resources for biological research. DNA Res 12: 291–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunisawa T, Kanaya S, Kutter E (1998) Comparison of synonymous codon distribution patterns of bacteriophage and host genomes. DNA Res 5: 319–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurland CG (1992) Translational accuracy and the fitness of bacteria. Annu Rev Genet 26: 29–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landy A, Ross W (1977) Viral integration and excision: structure of the lambda att sites. Science 197: 1147–1160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leipuviene R, Qian Q, Bjork GR (2004) Formation of thiolated nucleosides present in tRNA from Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium occurs in two principally distinct pathways. J Bacteriol 186: 758–766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ME, Hendrix RW, Casjens SR (1993) A programmed translational frameshift is required for the synthesis of a bacteriophage lambda tail assembly protein. J Mol Biol 234: 124–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limbach PA, Crain PF, McCloskey JA (1994) Summary: the modified nucleosides of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 22: 2183–2196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucks JB, Nelson DR, Kudla GR, Plotkin JB (2008) Genome landscapes and bacteriophage codon usage. PLoS Comput Biol 4: e1000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maynard ND, Birch EW, Sanghvi JC, Chen L, Gutschow MV, Covert MW (2010) A forward-genetic screen and dynamic analysis of lambda phage host-dependencies reveals an extensive interaction network and a new anti-viral strategy. PLoS Genet 6: e1001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson K, Lundgren HK, Hagervall TG, Bjork GR (2002) The cysteine desulfurase IscS is required for synthesis of all five thiolated nucleosides present in tRNA from Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium. J Bacteriol 184: 6830–6835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phizicky EM, Hopper AK (2010) tRNA biology charges to the front. Genes Dev 24: 1832–1860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierrel F, Douki T, Fontecave M, Atta M (2004) MiaB protein is a bifunctional radical-S-adenosylmethionine enzyme involved in thiolation and methylation of tRNA. J Biol Chem 279: 47555–47563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant EP, Rakauskaite R, Taylor DR, Dinman JD (2010) Achieving a golden mean: mechanisms by which coronaviruses ensure synthesis of the correct stoichiometric ratios of viral proteins. J Virol 84: 4330–4340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Py B, Barras F (2010) Building Fe-S proteins: bacterial strategies. Nat Rev Microbiol 8: 436–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Puchta W, Dominguez D, Lewetag D, Hohn T (1997) Plant ribosome shunting in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res 25: 2854–2860 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz CJ, Giel JL, Patschkowski T, Luther C, Ruzicka FJ, Beinert H, Kiley PJ (2001) IscR, an Fe-S cluster-containing transcription factor, represses expression of Escherichia coli genes encoding Fe-S cluster assembly proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 14895–14900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Felber BK, Fenyo EM, Pavlakis GN (1990) Env and Vpu proteins of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are produced from multiple bicistronic mRNAs. J Virol 64: 5448–5456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehu-Xhilaga M, Crowe SM, Mak J (2001) Maintenance of the Gag/Gag-Pol ratio is important for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA dimerization and viral infectivity. J Virol 75: 1834–1841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi R, Proteau A, Villarroya M, Moukadiri I, Zhang L, Trempe JF, Matte A, Armengod ME, Cygler M (2010) Structural basis for Fe-S cluster assembly and tRNA thiolation mediated by IscS protein-protein interactions. PLoS Biol 8: e1000354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprinzl M, Vassilenko KS (2005) Compilation of tRNA sequences and sequences of tRNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 33: D139–D140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y, Nakamura M (1999) Functional assignment of the ORF2-iscS-iscU-iscA-hscB-hscA-fdx-ORF3 gene cluster involved in the assembly of Fe-S clusters in Escherichia coli. J Biochem 126: 917–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi Y, Choi PJ, Li GW, Chen H, Babu M, Hearn J, Emili A, Xie XS (2010) Quantifying E. coli proteome and transcriptome with single-molecule sensitivity in single cells. Science 329: 533–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbina HD, Silberg JJ, Hoff KG, Vickery LE (2001) Transfer of sulfur from IscS to IscU during Fe/S cluster assembly. J Biol Chem 276: 44521–44526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbonavicius J, Qian Q, Durand JM, Hagervall TG, Bjork GR (2001) Improvement of reading frame maintenance is a common function for several tRNA modifications. EMBO J 20: 4863–4873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J (2001) A conserved frameshift strategy in dsDNA long tailed bacteriophages. PhD Thesis, University of Pittsburgh [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Bitoun JP, Ding H (2006) Interplay of IscA and IscU in biogenesis of iron-sulfur clusters. J Biol Chem 281: 27956–27963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.