Abstract

Crop domestication has been inferred genetically from neutral markers and increasingly from specific domestication-associated loci. However, some crops are utilized for multiple purposes that may or may not be reflected in a single domestication-associated locus. One such example is cultivated flax (Linum usitatissimum L.), the earliest oil and fiber crop, for which domestication history remains poorly understood. Oil composition of cultivated flax and pale flax (L. bienne Mill.) indicates that the sad2 locus is a candidate domestication locus associated with increased unsaturated fatty acid production in cultivated flax. A phylogenetic analysis of the sad2 locus in 43 pale and 70 cultivated flax accessions established a complex domestication history for flax that has not been observed previously. The analysis supports an early, independent domestication of a primitive flax lineage, in which the loss of seed dispersal through capsular indehiscence was not established, but increased oil content was likely occurred. A subsequent flax domestication process occurred that probably involved multiple domestications and includes lineages that contain oil, fiber, and winter varieties. In agreement with previous studies, oil rather than fiber varieties occupy basal phylogenetic positions. The data support multiple paths of flax domestication for oil-associated traits before selection of the other domestication-associated traits of seed dispersal loss and fiber production. The sad2 locus is less revealing about the origin of winter tolerance. In this case, a single domestication-associated locus is informative about the history of domesticated forms with the associated trait while partially informative on forms less associated with the trait.

Keywords: Crop domestication, flax, network analysis, sad2 gene, sequence variation

Introduction

Genetic studies of crop domestication have increased in the last two decades, largely thanks to the development of many informative molecular techniques (Zeder et al. 2006; Burke et al. 2007; Purugganan and Fuller 2009). Considerable research has been performed to investigate domestication events using selectively neutral and genome-wide molecular markers (Heun et al. 1997; Badr et al. 2000; Matsuoka et al. 2002; Morrell and Clegg 2007; Fu 2011). However, there has been an increasing trend to reconstruct the evolutionary history of domestication through the loci that have been subject to selection (Sang 2009; Gross and Olsen 2010; Blackman et al. 2011), as the genetic bases have been uncovered for many domestication-associated traits, including plant structural changes (Wang et al. 1999; Doebley et al. 2006; Li et al. 2006) and food quantity and quality (Sweeney et al. 2007; Shomura et al. 2008; Kovach et al. 2009). In the case of plants, the domestication process is increasingly considered to have been a protracted process (Allaby et al. 2008), and the assemblage of domestication-associated traits a staggered process (Fuller 2007). Under this scenario, there is an increased likelihood that each trait may have a quite disparate evolutionary history (Allaby 2010). Crops that have multiple purposes are interesting in this respect because genes governing traits relating to specific groups of the crop may carry variable domestication signatures. Thus, a locus-specific inference of different trait groups should reveal not only the group-specific domestication history but also the correlated domestication processes.

Flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) is a good example of a multiple purpose crop being utilized for oil and fiber. It was one of the eight “founder crops” of agriculture, was a principal source of oil and fiber from prehistoric times until the early 20th century, and still remains a crop of considerable economic importance (Zohary and Hopf 2000; Muir and Westcott 2003). The archaeological record shows that flax was domesticated for oil and/or fiber use more than 8000 years ago in the Near East (Helbaek 1959; van Zeist and Bakker–Heeres 1975) and suggests its wild progenitor as pale flax (L. bienne Mill. or previously L. usitatissimum L. subsp. angustifolium (Huds.) Thell.; Hammer 1986). The earliest reliable evidence of pale flax for human usage comes from Tell Abu Hureyra 11,200–10,500 years before present (yBP) (Hillman 1975), although recent claims have been made for much earlier usage that are disputed (Kvavadze et al. 2009; Bergfjord et al. 2010).

Morphological, cytological, and molecular characterizations confirm that pale flax is the wild progenitor of cultivated flax (Tammes 1928; Gill 1966, 1987; Diederichsen and Hammer 1995; Fu et al. 2002; Fu and Allaby 2010). Pale flax is a winter annual or perennial plant with narrow leaves and dehiscent capsules, and usually displays large variation in the vegetative plant parts and variable growth habit (Diederichsen and Hammer 1995; Uysal et al. 2011). Recent studies that expanded the available pale flax germplasm (Uysal et al. 2010, 2011) are informative about flax domestication syndromes (Hammer 1984). Generally, cultivated flax has variable seed dormancy, grows fast with large variation in the generative plant parts, and has early flowering, almost indehiscent capsules, and large seeds. In addition to oil and fiber varieties, flax accessions with winter hardiness and capsular dehiscence are also available for research (Diederichsen and Fu 2006).

Domestication-associated genes offer an approach to reconstructing the specific domestication history of a crop with an associated trait with phylogenetic and phylogeographic resolution. Such approaches have provided insights into the independent origins of various traits in rice (e.g., Shomura et al. 2008; Kovach et al. 2009) and in sunflower (Blackman et al. 2011). However, flax presents several problems for this type of approach. First, no domestication-associated genes have yet been identified in flax. Second, the variety of uses of flax implies that different subsets of cultivated flax have different trait combinations, and consequently it is not clear to what extent a single domestication gene may be used to infer the domestication history of the crop as a whole.

The sad2 locus is a potential domestication target in flax because of its role in fatty acid metabolism. The sad2 gene is responsible for converting stearoyl-ACP to oleoyl-ACP by introducing a double bond at C9 and thus can increase the unsaturated fatty acid content of the plant (Ohlrogge and Jaworski 1997; Jain et al. 1999). This gene has been well characterized due to commercial interest for the manipulation of unsaturated fatty acids in major crop plants (Shanklin and Sommerville 1991; Knutzon et al. 1992; Singh et al. 1994). Preliminary molecular evidence based on the sad2 locus in a relatively small sample of flax suggested that the initial purpose of flax domestication was for its oil use (Allaby et al. 2005). This study was limited because it considered very few pale flax accessions and only oil, fiber, and landrace varieties of cultivated flax. More recently, expressed sequence tag-derived simple sequence repeat (EST-SSR) markers (Cloutier et al. 2009; Fu and Peterson 2010) were applied to the expanded pale flax germplasm (Fu 2011). This study established that the primitive dehiscent type of cultivated flax assumed a basal position in genome-wide marker phenograms, suggesting that these varieties were important in the early stages of domestication. However, the overall resolution was not high.

The aim of this study was to assess whether the sad2 locus increases oil production in cultivated flax and whether a reconstruction of the domestication history of this trait based on the gene is widely informative for cultivated flax using a broad sample of accessions representing the recently expanded pale flax germplasm set and the four cultivated flax groups.

Materials and Methods

All flax accessions studied here were obtained from the flax collection at the Plant Genetic Resources of Canada (PGRC; Table 1). They include 43 pale flax accessions and 70 cultivated flax accessions. The pale flax accessions were selected largely from recently acquired pale flax accessions from Turkey and Greece, in addition to those representing the old pale flax collection in PGRC. This expanded set of pale flax accessions represent only part of its natural distribution spanning the western Europe and the Mediterranean, north Africa, western and southern Asia, and the Caucasus regions (Diederichsen and Hammer 1995). The cultivated flax accessions were selected to represent five major groups of cultivated flax (landrace, fiber, oil, winter, and dehiscent). The landrace group represents a collection of local oil and/or fiber varieties from different countries. The winter flax accessions sampled cultivated flax developed with winter hardiness from 12 countries. The dehiscent flax accessions represent the primitive form of cultivated flax with dehiscent capsules and have been long accumulated from flax cultivation in the cultivated flax gene pool (Hegi 1925). For this study, the dehiscent flax accessions were empirically verified for capsular dehiscence and the selected pale flax accessions were assessed for their taxonomic identity in the greenhouse. Also, the accession selection process took into account the country of origin to widen genetic diversity for this study.

Table 1.

List of 113 accessions of wild and cultivated flax sequenced, with their species/type and origin country

| CN1 | Species/type2 | Description3 | Origin4 | Label5 | CN | Species/type | Description | Origin | Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 107293 | Lb | UN(1) | Bm1 | 98475 | Lu-f | Flachskopf | DEU | Uf7 | |

| 107257 | Lb | UN(2) | Bm2 | 101392 | Lu-f | Tajga | FRA | Uf8 | |

| 19021 | Lb | FRA | Bm3 | 101111 | Lu-f | Viking | FRA | Uf9 | |

| 107258 | Lb | UN(2) | Bm4 | 101086 | Lu-f | Ariadna | HUN | Uf10 | |

| 19022 | Lb | DEU | Bm5 | 98946 | Lu-f | Talmune fiber | NLD | Uf11 | |

| 19023 | Lb | USA | Bm6 | 101120 | Lu-f | Liana | POL | Uf12 | |

| 113601 | Lb | Samsun | TUR | Bt1 | 97325 | Lu-f | Kotowiecki | POL | Uf13 |

| 113602 | Lb | Samsun | TUR | Bt2 | 101405 | Lu-f | Mures | ROM | Uf14 |

| 113603 | Lb | Samsun | TUR | Bt3 | 18991 | Lu-f | Nike | RUS | Uf15 |

| 113604 | Lb | Samsun | TUR | Bt4 | 97871 | Lu-f | Atlas | SWE | Uf16 |

| 113605 | Lb | Samsun | TUR | Bt5 | 101397 | Lu-f | Pskovski 2976 | UKR | Uf17 |

| 113606 | Lb | Samsun | TUR | Bt6 | 101021 | Lu-n | Mestnyi | AFG | Un1 |

| 113607 | Lb | Samsun | TUR | Bt7 | 19009 | Lu-n | Mestnyi | CHN | Un2 |

| 113608 | Lb | Samsun | TUR | Bt8 | 100896 | Lu-n | Giza | EGY | Un3 |

| 113610 | Lb | Denizli | TUR | Bt9 | 100895 | Lu-n | Karbin | ETH | Un4 |

| 113616 | Lb | İzmir | TUR | Bt10 | 100890 | Lu-n | Svapo | FRA | Un5 |

| 113617 | Lb | İzmir | TUR | Bt11 | 19010 | Lu-n | Mestnyi | IRN | Un6 |

| 113618 | Lb | Muğla | TUR | Bt12 | 100909 | Lu-n | Palestina | ISR | Un7 |

| 113619 | Lb | Muğla | TUR | Bt13 | 100911 | Lu-n | Cremone | ITA | Un8 |

| 113620 | Lb | Muğla | TUR | Bt14 | 101070 | Lu-n | landrace | RUS | Un9 |

| 113621 | Lb | Muğla | TUR | Bt15 | 101614 | Lu-o | Signal | BLR | Uo1 |

| 113622 | Lb | Antalya | TUR | Bt16 | 19003 | Lu-o | AC McDuff | CAN | Uo2 |

| 113623 | Lb | Antalya | TUR | Bt17 | 18974 | Lu-o | CDC Bethune | CAN | Uo3 |

| 113626 | Lb | Samsun | TUR | Bt18 | 100832 | Lu-o | Barbarigo | CZE | Uo4 |

| 113627 | Lb | Sinop | TUR | Bt19 | 101174 | Lu-o | Rastatter | DEU | Uo5 |

| 113628 | Lb | Karabük | TUR | Bt20 | 97436 | Lu-o | Giza | EGY | Uo6 |

| 113629 | Lb | Kastamonu | TUR | Bt21 | 101171 | Lu-o | Hermes | FRA | Uo7 |

| 113630 | Lb | Kastamonu | TUR | Bt22 | 18989 | Lu-o | Atalante | FRA | Uo8 |

| 113632 | Lb | Zonguldak | TUR | Bt23 | 101265 | Lu-o | Amason | GBR | Uo9 |

| 113633 | Lb | Zonguldak | TUR | Bt24 | 98263 | Lu-o | Chaurra Olajlen | HUN | Uo10 |

| 113634 | Lb | Bolu | TUR | Bt25 | 98256 | Lu-o | Arreveti | IND | Uo11 |

| 113635 | Lb | Bolu | TUR | Bt26 | 97888 | Lu-o | Tomagoan | IRN | Uo12 |

| 113636 | Lb | Bilecik | TUR | Bt27 | 101237 | Lu-o | Artemida | LTU | Uo13 |

| 113637 | Lb | Bursa | TUR | Bt28 | 101268 | Lu-o | Raisa | NLD | Uo14 |

| 113638 | Lb | Çanakkale | TUR | Bt29 | 101245 | Lu-o | Bryta | POL | Uo15 |

| 113639 | Lb | Çanakkale | TUR | Bt30 | 100917 | Lu-o | Raluga | ROM | Uo16 |

| 113640 | Lb | Istanbul | TUR | Bt31 | 101233 | Lu-o | Rolin | ROM | Uo17 |

| 113641 | Lb | Çanakkale | TUR | Bt32 | 101292 | Lu-o | Zarjanka | RUS | Uo18 |

| 113642 | Lb | Trabzon | TUR | Bt33 | 98965 | Lu-o | New River | USA | Uo19 |

| T19719 | Lb | Island of Evia | GRC | Bg1 | 33399 | Lu-o | Bison | USA | Uo20 |

| T19718 | Lb | Island of Evia | GRC | Bg2 | 98178 | Lu-w | 1285-S | AFG | Uw1 |

| T19717 | Lb | Island of Koss | GRC | Bg3 | 97756 | Lu-w | Italia Roma | ARG | Uw2 |

| T19716 | Lb | Rhodes airport | GRC | Bg4 | 96915 | Lu-w | Uruguay 36/49 | AUS | Uw3 |

| 97606 | Lu-d | ESP | Ud1 | 97015 | Lu-w | Uruguay 36/49 | AUS | Uw4 | |

| 100852 | Lu-d | Grandal | PRT | Ud2 | 97009 | Lu-w | Beladi Y 6903 | EGY | Uw5 |

| 100910 | Lu-d | Grandal | PRT | Ud3 | 97004 | Lu-w | ETH | Uw6 | |

| 97769 | Lu-d | Abertico | PRT | Ud4 | 97205 | Lu-w | Redwing 92 | GRC | Uw7 |

| 97473 | Lu-d | RUS | Ud5 | 98283 | Lu-w | La Previzion | HUN | Uw8 | |

| 98833 | Lu-d | RUS | Ud6 | 98509 | Lu-w | ISR | Uw9 | ||

| 97605 | Lu-d | RUS | Ud7 | 97102 | Lu-w | PAK | Uw10 | ||

| 100837 | Lu-d | TUR | Ud8 | 96846 | Lu-w | RUS | Uw11 | ||

| 101160 | Lu-f | Wiko | AZE | Uf1 | 96960 | Lu-w | SYR | Uw12 | |

| 98986 | Lu-f | Crista | BEL | Uf2 | 96848 | Lu-w | TUR | Uw13 | |

| 98935 | Lu-f | Motley fiber | BLR | Uf3 | 96902 | Lu-w | TUR | Uw14 | |

| 101017 | Lu-f | Baladi | CHN | Uf4 | 100828 | Lu-w | TUR | Uw15 | |

| 98479 | Lu-f | Zakar | CZE | Uf5 | 100829 | Lu-w | TUR | Uw16 | |

| 101388 | Lu-f | Saskai | CZE | Uf6 |

CN = Canadian National accession number at Plant Gene Resources of Canada (PGRC), Saskatoon, Canada. T = temporary number for accessions that were acquired, but not yet added to the PGRC germplasm collection.

Lb = Linum bienne; Lu = Linum usitatissimum. Five letters (n, f, o, w, d) after Lu represents five groups of cultivated flax (landrace, fiber, oil, winter, dehiscence), respectively.

Description of an accession includes the record, if available, for varietal or local name, location, and feature.

Origin of country, following ISO 3166–1 alpha-3 country code. UN = unknown origin, but the seed source is shown with a number in parentheses: 1 = All-Russian Flax Research Institute, VNIIL, Torzhok, Russia, and 2 = Jardin Botanique de la Ville et de l’Universite de Caen, France.

Accession label includes the first letter for species (B = L. bienne; U = L. usitatissimum), the second letter (if any) for the country of L. bienne accessions (t = Turkey, g = Greece, and m = multiple countries) and for the group of cultivated flax (n = landrace, f = fiber, o = oil, w = winter, d = dehiscence), and the number distinguishing among accessions.

Oil profile

The oil profile data used in this study were collected from two separate characterization efforts. The first one was completed before 2006 on 2934 accessions of cultivated flax (Diederichsen and Raney 2006) and the second one was performed in 2010 on 141 samples of pale flax by Drs. A. Diederichsen and R. Zhou. The pale flax samples largely consisted of the pale flax germplasm recently collected from Turkey and Greece. Both characterizations employed the same experimental procedures as described in Diederichsen and Raney (2006). Briefly, the seed oil content was measured using continuous wave nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy based on a sample of 10 g of flax seed at 3–4% water content. The fatty acid composition of the seed oil was analyzed by gas chromatography.

DNA extraction

Plants were grown from seed for 2–3 weeks for cultivated flax and up to 2 months for pale flax in a greenhouse at the Saskatoon Research Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada. Young leaves were individually collected, freeze-dried [in a Labconco Freeze Dry System (Kansas City, MO, USA) for 1–3 days], and stored at –20°C. A freeze-dried leaf sample of one individual plant from each accession was selected, and its genomic DNA was extracted with the DNEasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). Extracted DNA was quantified with a Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 8000 spectrometer (Fisher Scientific Canada, Toronto, Ontario, Canada).

PCR and sequencing

The protocols and procedures to amplify and to sequence the sad2 locus were given in Allaby et al. (2005). Briefly, two sets of PCR primer pairs were applied to amplify the whole region of the sad2 locus. PCR was performed on either a DYAD or PTC-200 thermocycler (Bio Rad, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) and the PCR products were separated on 2% agarose (Sigma, Oakville, Ontario, Canada). Amplicons were excised from agarose gel, purified using a QiaQuick Gel purification kit (Qiagen), and resuspended in 16-µl Qiagen elution buffer. Sequencing was done using an Applied Biosystems capillary DNA sequencer (DNA Technologies Unit, Plant Biotechnology Institute, National Research Council of Canada, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada).

Sequence analysis

All sequencing products were assembled with Vector NTI Suite's ContigExpress v9.0.0 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and aligned using MUSCLE v3.6 (Edgar 2004). All aligned sequences were deposited into GenBank under accessions JN653341-JN653453. Population genetic analyses of aligned DNA sequences were performed using DnaSP program (Librado and Rozas 2009). Several measures of sequence variation were obtained, and they are the number of segregating sites, haplotype number, nucleotide diversity (π; Tajima 1983), the signal of selection (i.e., deviation from neutrality; Tajima 1989; Fu and Li 1993), and the frequency of recombination (i.e., the minimum number of recombination events; Hudson and Kaplan 1985). The comparative diversity analyses were also done for various groups of flax germplasm. Haplotype analyses with and without gaps and indels were performed using DnaSP program. The positions of SNPs and indels for each haplotype were generated.

An analysis of molecular variance (AMOVA) was also performed using Arlequin v3.01 (Excoffier et al. 2005) to quantify nucleotide variation between species and among various groups of Linum accessions. Three models of genetic structuring were considered: pale versus cultivated flax, two originating groups of pale flax, and five groups of cultivated flax. The significance of variance components and intergroup genetic distances for each model was tested with 10,010 random permutations.

A network analysis was applied to display phylogenetic relationships among taxa because this approach allows for extant ancestral states in which taxa occupy internal node positions, and reticulate relationships caused by character conflict, such as those resulting from recombination events. Briefly, networks provide a graphical approach to describing character conflict, instances where characters support different trees, as reticulations. The resulting graphs may then be interpreted as either containing all the most parsimonious trees, or as a visualization of recombination events. The phylogenetic network of the studied accessions was constructed as described previously (Allaby and Brown 2001; Allaby et al. 2005). A deletion of 46 nucleotides occurred at position 562 of the alignment, which was used as a character in building the network. The phylogenetic topology of the network was confirmed through maximum likelihood (fastDNAml; Olsen et al. 1994), neighbor-joining analyses (NEIGHBOR; Felsenstein 1989), and NeighborNet (SplitsTree; Huson and Bryant 2006).

The date estimates for nodes from the network were corroborated using the Bayesian MCMC approach implemented in BEAST v1.4 (Drummond and Rambaut 2007). Maximum clade credibility (MCC) phylogenies were generated using the node II/III split calibrated under a uniform prior with a range of 11,000–9500 yBP, under a GTR model with gamma distribution for site heterogeneity and a relaxed uncorrelated lognormal clock. Three tree prior models were investigated: (1) with tree prior as constant size; (2) with tree prior as expansion growth; and (3) with tree prior as exponential growth. The rest of the options were applied with default values. The Bayesian MCMC approach should be more informative for dating a lineage involving recombination events, as it directly calculates ultrametric phylogenies based only on sequence data and model parameters and incorporates both the branch length errors and the topological uncertainties (Rutschmann 2006).

Results and Discussion

Oil profile

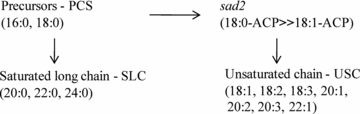

A considerably higher ratio of 18:1 oleoyl-ACP to precursor saturated fatty acids was obtained for the assayed groups of cultivated flax than the pale flax samples (Table 2). The ratio of total unsaturated to saturated precursor fatty acids, although not statistically significant, was generally higher in the cultivated, than pale, flax samples. These two sets of oil data can be interpreted as either an increase in total unsaturated fatty acids, or a decrease in the saturated acid precursors, or both. Figure 1 illustrates the salient features of fatty acid metabolism considered here. While an increase in the unsaturated fatty acid products would naturally be expected to lead to a decrease in unsaturated precursors, a second sink for the latter occurs through the production of long-chain saturated acids. However, the ratio of long-chain saturated fatty acids to the precursors is generally less in the cultivated, than pale, flax samples (Table 2), indicating that this path did not explain the decrease in precursor saturated fatty acids and indeed less long chain saturated fatty acids were produced in cultivated flax. Thus, there was an increase in the product of the sad2 locus, 18:1 oleoyl-ACP. Such increase could be either due to a higher productivity of the sad2 locus or a decrease in productivity downstream in the metabolic pathway at loci such as fad2, fad3, or fae1, so causing an accumulation of oleoyl-ACP. However, if the latter were to entirely explain the high levels of oleoyl-ACP, one would not expect the increase in the overall unsaturated to saturated fatty acid ratio observed. The downstream products in the metabolic pathway after the production of oleoyl-ACP are present in quantities approximately 20-fold higher than oleoyl-ACP. Thus, it is not surprising that the shift in ratio to saturated precursors is less pronounced for unsaturated acids as a whole than for just oleoyl-ACP. The oil composition data support that an increased productivity of the sad2 locus in cultivated flax was associated with the increased unsaturated fatty acid content. Based on this oil profile, we can reason that the sad2 locus is a candidate domestication-associated locus.

Table 2.

Ratios of related fatty acid components for Linum groups

| Group | n | 18:1/PCS1 | USC/PCS1 | SLC/PCS × 1001 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pale flax | 141 | 0.349(0.057) | 9.055(0.855) | 4.917(0.729) |

| Cultivated flax | 2768 | 0.447(0.052) | 9.431(1.844) | 4.075(0.437) |

| Dehiscent flax | 6 | 0.453(0.025) | 9.992(0.855) | 4.762(0.526) |

| Fiber flax | 331 | 0.455(0.057) | 10.643(1.686) | 4.044(0.400) |

| Oil flax | 2264 | 0.442(0.049) | 9.373(1.794) | 4.064(0.440) |

PCS = precursor saturated fatty acids (16:0, 18:0), USC = unsaturated fatty acids (18:1, 18:2, 18:3, 20:1, 20:2, 20:3, 22:1), SLC = saturated long-chain fatty acids (20:0, 22:0, 24:0). The values in parentheses are standard errors of the ratio estimates. See Figure 1 for the simplified fatty acid pathway for related components.

Figure 1.

A simplified fatty acid pathway showing the sources and sinks for the function of sad2 gene.

Nucleotide polymorphism

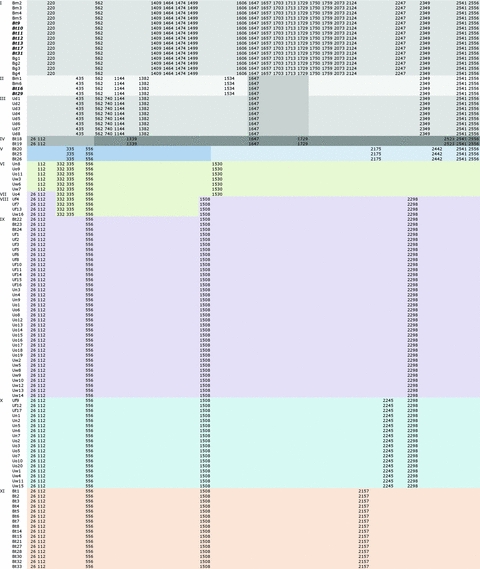

The aligned nucleotide sequences of sad2 amplified from 113 accessions are 2560 bp in length, covering three exons, two introns, and the upstream and downstream flanking regions (Table 3). A total of 38 polymorphic sites were found with 17 segregating sites in intron 2 (45%), 12 sites in exon 3 (32%), six sites in intron 1 (16%), and one for each of other two exons and flanking region. All of them are parsimony informative. Only one indel of length 46 bp in the intron 1 at the positions from 562 to 607 was detected in all eight accessions of dehiscent flax and 19 pale flax accessions of diverse country origins including five accessions from Turkey. Interestingly, such an indel was not found in the other 24 pale flax accessions collected from Turkey and the remaining 62 accessions of cultivated flax. These findings support the existence of two distinctive backgrounds in pale flax germplasm collected from Turkey (Uysal et al. 2011). A large set of pale flax accessions was more closely related to cultivated flax (Fig. 2). An overall average pairwise nucleotide diversity of 0.00371 was obtained across all 113 samples. Deviation from neutrality was not significant with Tajima's D of 0.8856 (at P > 0.10), but significant by Fu and Li's D* and F* test statistics (D* = 2.0778 at P < 0.02 and F* = 1.9155 at P < 0.05, respectively; Fu and Li 1993). There were 13 synonymous mutations observed in all three exons, but only one nonsynonymous change at exon 3 (at position 2245) from serine to proline in the sad2 protein was detected in cultivated flax. Such a nonsynonymous change was also observed in the Genbank accession AJ006958.

Table 3.

Nucleotide polymorphism at the sad2 locus for 10 groups of wild and cultivated flax samples

| Group/parameter1 | Flanking (187)2 | Exon1 (123) | Intron1 (609) | Exon2 (505) | Intron2 (722) | Exon3 (563) | Total (2709) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lb-all (43) | |||||||

| S | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 16 | 11 | 34 |

| H | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| π/bp | 0.00701 | 0.00416 | 0.00228 | 0.00034 | 0.00918 | 0.00729 | 0.00515 |

| D | 1.6980 | 1.6980 | 0.9087 | –0.3533 | 2.4867 3 | 1.5727 | 2.2276 3 |

| Lb-Turkey (33) | |||||||

| S | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 16 | 11 | 34 |

| H | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| π/bp | 0.00654 | 0.00388 | 0.00194 | 0.00023 | 0.0072 | 0.00676 | 0.00435 |

| D | 1.4168 | 1.4168 | 0.2676 | –0.7915 | 1.0383 | 1.0290 | 1.0918 |

| Lb-Others (10) | |||||||

| S | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 13 | 3 | 19 |

| H | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| π/bp | 0 | 0 | 0.00126 | 0.0007 | 0.00644 | 0.00201 | 0.00269 |

| D | nd | nd | 0.0189 | 0.015 | 0.0266 | 0.0211 | 0.0274 |

| Lu-all (70) | |||||||

| S | 1 | 1 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 17 |

| H | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 |

| π/bp | 0.00649 | 0.00167 | 0.00205 | 0.00041 | 0.0013 | 0.00253 | 0.00167 |

| D | 0.6984 | –0.0128 | 0.2534 | –0.0128 | 0.2674 | 0.6723 | 0.5392 |

| Lu-d (8) | |||||||

| S | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| H | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| π/bp | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| D | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| Lu-o (20) | |||||||

| S | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| H | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| π/bp | 0.0026 | 0 | 0.00088 | 0 | 0.00075 | 0.00134 | 0.00077 |

| D | –0.5916 | nd | –0.1119 | nd | –0.1119 | 0.6105 | 0.0010 |

| Lu-f (17) | |||||||

| S | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| H | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| π/bp | 0 | 0 | 0.00101 | 0 | 0 | 0.00058 | 0.00036 |

| D | nd | nd | 0.1100 | nd | nd | 0.0851 | 0.1248 |

| Lu-w (16) | |||||||

| S | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| H | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| π/bp | 0.0065 | 0 | 0.00131 | 0 | 0.00091 | 0.00136 | 0.00099 |

| D | 0.1557 | nd | 0.8377 | nd | 0.2007 | 0.5192 | 0.6522 |

| Lu-n (9) | |||||||

| S | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| H | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| π/bp | 0.00304 | 0 | 0.00073 | 0 | 0.00062 | 0.00146 | 0.00074 |

| D | –1.0882 | nd | –1.3624 | nd | –1.3624 | 0.1959 | –1.1893 |

Lb = Linum bienne; Lu = Linum usitatissimum; Lb-all for all wild flax samples; Lb-Turkey for wild flax samples from Turkey; Lb-others for wild flax samples from other countries; Lu-all for all cultivated flax samples; and five other groups of cultivated flax (landrace, fiber, oil, winter, dehiscent) labeled with five letters (n, f, o, w, d) after Lu, respectively. Four polymorphism parameters are S for the number of segregating sites; H for the haplotype number; π/bp for nucleotide diversity; and D for selection test by Tajima's D.

The length of the region(s) is given in parentheses. nd means not defined.

For the level of test significance at P < 0.05 for selection.

Figure 2.

Composition of 39 polymorphic sites for each sample of 11 groups reflecting 11 haplotypes. The group is labeled in the first column, the sample in the second column (see Table 1), and the composition in the columns 3–41. The pale flax samples from western Turkey are highlighted with italic and bold. The numbers in the composition columns are the positions of substitutions. Different background colors were used to make the haplotype identification easier.

Further examination of nucleotide polymorphism between two species and among various groups of flax accessions revealed several more patterns of genetic diversity at the locus (Table 3). First, as expected, there was more genetic variation in pale flax than cultivated flax. The pale flax had 34 polymorphic sites with a nucleotide diversity of 0.00515, while the cultivated flax had 17 polymorphic sites with a nucleotide diversity of 0.00167. There were 14 polymorphic sites shared by two species, 20 unique to pale flax, and only four unique to cultivated flax (Fig. 2). Second, a significant deviation from neutrality was found only in intron 2 with Tajima's D of 2.4867, resulting in an overall significant selection observed in 43 pale flax accessions. However, such neutrality deviation disappeared when pale flax accessions were separated based on country origin between Turkey and other countries. Clearly, the pale flax accessions from Turkey had more variation than those from other countries with nucleotide diversity values of 0.00435 and 0.00274, respectively. Third, among various groups of cultivated flax, winter flax had the largest nucleotide diversity at the locus (0.00099) with four haplotypes, followed by the oil flax (0.00077) with four haplotypes, landrace flax (0.00074) with three haplotypes, and fiber flax (0.00036) with three haplotypes. All eight dehiscent flax samples had the same haplotype and one monomorphic site (at position 740) unique to its own (Table 3; Fig. 2). Quantifying nucleotide differences by AMOVA revealed 32.9% nucleotide variation present between two flax species, 44.5% between pale flax samples from Turkey and those from other countries, and 65% among five groups of cultivated flax. The largest nucleotide difference in cultivated flax was due to the unique haplotype in dehiscent flax samples, and removing dehiscent flax samples generated nonsignificant nucleotide differences among other four groups of cultivated flax.

In summary, the observed nucleotide polymorphism at the locus indicates that cultivated flax has been subjected to a reduced genetic diversity either through a population bottleneck or selection undetected in this study, probably during the domestication process. The genetic diversity is not bilaterally partitioned between pale and cultivated flax, suggesting that the cultivated flax gene pool represents multiple samples of the pale flax gene pool during the domestication process. However, evidence for selection at the sad2 locus was not strong as revealed with Tajima's D or Fu and Li's D* and F* test statistics.

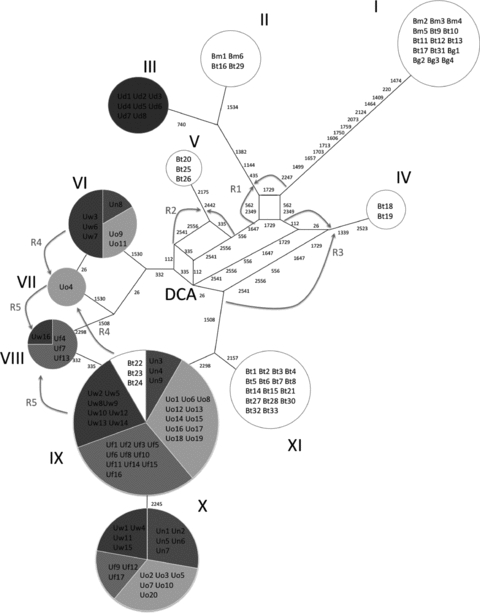

Phylogenetic network

A network was constructed from 113 samples in this study (Fig. 3). Eleven nodes labeled from I to XI were detected and represented 11 haplotypes across all the samples. The pale flax had five private nodes (I, II, IV, V, XI) and one node (IX) shared with cultivated flax. The largest pale flax node (I), including all four accessions from Greece and some accessions from Turkey and other countries, was distant from cultivated flax, while the others were closely associated with some groups of cultivated flax. The node II of four pale flax samples was closely associated with the node III of eight dehiscent flax samples. The other four nodes (IV, V, X, XI) of 24 pale flax samples collected largely from northern Turkey formed some degree of reticulation with cultivated flax. For cultivated flax, the oil flax occupied four nodes (VI, VII, IX, and X), fiber flax three nodes (VIII, IX, X), and winter flax four nodes (VI, VIII, IX, X). Also, the oil flax appeared to have one private node (VII), while the fiber flax had none. The largest node IX had 36 samples representing the pale flax from Turkey and four groups of cultivated flax (landrace, oil, fiber, and winter). The node X was generated by a nonsynonymous substitution (at the position 2245) and consisted of four groups of cultivated flax (landrace, oil, fiber, and winter). Moreover, the oil and winter flax samples shared one more substitution (at the position 332) with the pale flax samples and seem to be more directly linked to the pale flax from Turkey than the fiber flax. The most likely domestication common ancestor (DCA) detected with the shortest branch length (i.e., with the fewest homoplasies) was consistent with those from the previous analysis with an outgroup (Allaby et al. 2005). It is interesting to note that the dehiscent flax samples from four different countries shared the same distinct genotype, while the locus-specific divergence among other four groups of cultivated flax was not clear-cut.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic network of pale flax and cultivated flax at the sad2 locus. Eleven nodes reflecting 11 haplotypes detected across 113 samples were labeled from I to XI. Labels within a node relate to accessions (see Table 1). The size of node circles relates to sample frequency. The numbers by branches indicate the positions of substitutions detected for that branch. Character conflicts are described as reticulations within the network. The position of the most likely domestication common ancestor (DCA) to all alleles in cultivated flax is indicated by DCA. Five recombination events were detected and numerically labeled.

The network has one large area of reticulation. The recombination analysis (Hudson and Kaplan 1985) performed with DnaSP program revealed at least three recombination events between the sites (26, 332), (335, 1508), and (1729, 2349), respectively. Five recombination events were detected following the methodology of Fu and Allaby (2010) and labeled in Figure 3. The probability of a mutation being homoplasious in the alignment is 1/3P (Forster et al. 1996) where P = 1/2560 in this study. The network contains 39 substitutions, and the probability of any one mutation being homoplasious in the network is 0.005 [ = (1/3) × (1/2560) × 39], leading to an expectation of 0.19 homoplasies in total. However, a total of seven homoplasies were observed (1.14 × 10–9) in the network. For each recombination event, two ancestral nodes are possible, corresponding opposite corners of the associated reticulation. All reticulations were found to be significant at the 5% level, and R3–R5 were significant at the 1% level (Table 4). Our analysis revealed two more recombination events than those detected following Hudson and Kaplan (1985). Therefore, the reticulations in the network largely represent recombination events rather than homoplasies.

Table 4.

Statistical support for recombination events at the sad2 locus

| Event | N (position)1 | H(position)2 | N/H | P(H/N)3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | 4 (1382, 1144, 435, 1729) | 1 (1729) | 0.25 | 0.02 |

| R2 | 3 (2541, 2556, 335) | 1 (335) | 0.33 | 0.015 |

| R3 | 4 (112, 26, 1339, 2523) | 2 (112, 26) | 0.50 | 0.00015 |

| R4 | 1 (26) | 1 (26) | 1.00 | 0.0051 |

| R5 | 2 (332, 335) | 2 (332, 335) | 1.00 | 0.000025 |

Number of substitutions in branch; substitution position is given in parentheses.

Number of homoplasies in branch; substitution position is given in parentheses.

Probability of observing H or more homoplasies for the given branch length calculated from the binomial distribution.

Dating flax haplotypes

Pale flax samples were closely associated with groups III and IX, offering some inference of divergence time for these lineages. It seems likely that a group of pale flaxes close to node VI either still exists but has not been sampled or has gone extinct, given the proximity in the network of pale flaxes to the other cultivated groups. The node leading to group III for the dehiscent type of cultivated flax appears to be the deepest in the network for which there are closely related pale flaxes. This suggests that this group is probably the oldest of the cultivated flax groups, which is in agreement with previous EST-SSR data (Fu 2011). Therefore, the node leading to group III makes the most reasonable calibration point using a domestication period of 10,000 yBP (Hillman 1975), which yields a reasonable rate of 3.9 × 10–8 subs/site/year (Wolfe et al. 1989). Given this rate of change, the DCA becomes 33,000 years old and the cultivated lineage founded in group IX began roughly 3300 years ago. This rate estimate contrasts with previous estimates (Allaby et al. 2005) in which the DCA node on a much simpler network was used as the basis of a 10,000 years calibration leading to a rate estimate of 1.71 × 10–7 subs/site/year, which is about 10-fold higher than would be expected for a plant synonymous substitution rate.

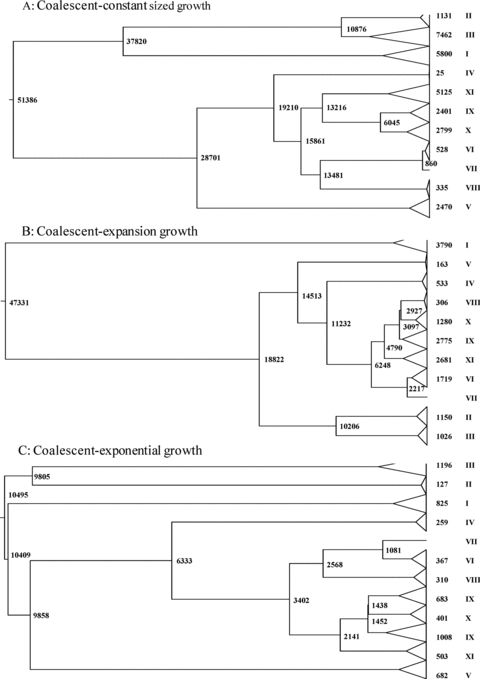

These dates were further investigated with BEAST v1.4, using as a calibration point the II/III group split to a time ranging from 11,000to 9500 yBP. Three MCC trees obtained using BEAST v1.4 are shown in Figure 4. Interestingly, the three models correctly identified each member of 11 haplotypes with one exception and generated similar topologies that are compatible with the network shown in Figure 3. The exception occurred under the exponential expansion model where groups IX and X become an unresolved polytomy, which is a minor deviation in topology due to the effects of recent expansion. The topology of the constant sized population matched the topology of the network most closely, while the expansion growth model placed group VIII as a sister taxon to group X, and the exponential growth model failed to resolve groups IX and X. The ages of the nodes are shown on the trees expressed as yBP. The age estimates obtained overlap with the estimates from the network in the case of the constant population size and expansion models. The exponential model, however, poorly fitted the data with the formation of the dehiscent and associated pale flax clade being close to the root of the entire tree despite only two substitutions along these branches. Under the constant population size model, the origin of the IX lineage is around 6045 yBP, and the DCA node is dated to around 15,861 yBP with a wide margin of error extending to around 47,000 yBP. The expansion model, which is perhaps more likely to reflect the true underlying population process for cultivated flax at least, yielded younger dates, with the IX lineage being around 3097 yBP, which is close to the network estimate. In this case, the DCA node is very young at around 6247 yBP, also with a wide error extending to 26,000 yBP. In reality, it is likely that the true underlying population process that gave rise to this phylogeny would have been a combination of long-term constant population size for the pale flax populations, followed by an expanding cultivated population. The existence of group XI suggests that the DCA node would have been represented more likely by pale flax rather than cultivated flax. Consequently, the DCA node probably relates to a time before an expansion process associated with cultivation would have taken place, leading to the optimum date under the expansion model of 6247 years probably being inappropriate.

Figure 4.

Maximum clade credibility (MCC) phylogenies obtained using BEAST v1.4 (Drummond and Rambaut 2007) with three tree prior models. (A) With tree prior as constant size, (B) with tree prior as expansion growth, and (C) with tree prior as exponential growth. The MCC trees are collapsed for each haplotype (see Fig. 2) that is labeled on the far right column. The ages of the internal nodes, expressed as yBP, are shown on the tree and the ages of the tip nodes on the second right column.

Flax domestication history at the sad2 locus

The level of unsaturated fatty acids in flax seeds increased during domestication involving an apparent increased productivity of the sad2 locus, indicating that the sad2 locus may be considered a candidate domestication locus. However, the mechanism of increased productivity has not yet been discovered. It is highly possible that the sad2 locus may not be the only candidate locus, as other cis- and trans-acting loci may have been involved with the fatty acid metabolism. Thus, the true contribution of the sad2 sequence variation to the difference observed in fatty acid composition between the cultivated and pale flax samples remains unknown. Either way, the phylogenetic reconstruction of the sad2 locus reflects a specific history associated with increased unsaturated oil production in cultivated flax.

The network analysis involving a large set of pale flax and four groups of cultivated flax revealed a complex domestication history of flax that has not been previously observed. The pale flax displayed two different groupings in agreement with other studies (Uysal et al. 2011). One group represents two lineages (I and II) including pale flax samples collected from different countries including western Turkey and Greece and has an indel shared with the dehiscent type of cultivated flax (III). Comparison with the sad1 sequence, which does not have the deleted character state, indicates that this indel is a deletion in the branches leading to groups I to III rather than an insertion in groups IV and above. The second group (XI) represents only the pale flax samples from northern Turkey along the Black Sea coast and has a genetic background shared more closely with the indehiscent groups of cultivated flax (VI, VII, VIII, IX, and X). These genetic associations expand on the previous observation of the basal position of the dehiscent flax group (Fu 2011). These data indicate that the dehiscent cultivated flax lineage should be regarded as an independent domestication. The molecular dating used in this study confirms the early nature of this domestication, before the subsequent domestication process that led to the indehiscent cultivated flax groups. Interestingly, the oil profile data (Table 2) indicate that the increase in unsaturated fats had occurred in the dehiscent cultivated flax lineage, but loss of seed dispersal through capsular indehiscence had not. This suggests that selection for oil composition came before loss of seed dispersal, and that the dehiscent cultivated flax lineage represents an alternative or incomplete domestication trajectory as compared to the other cultivated flax groups. This order of trait fixation is similar to the case of cereals in which loss of seed dispersal was a trait that was fixed late in the domestication process (Tanno and Willcox 2006; Fuller 2007).

The indehiscent cultivated flax groups appear to represent a domestication process that may have involved more than one domestication. The close proximity of group IX to the pale flax group XI suggests that this is a separate domestication to that associated with group VI. An alternative explanation could be that the indehiscent cultivated flax was domesticated from a genetically diverse population (Charlesworth 2010) that has maintained two distinct lineages. However, the distinct geographical clustering of the pale flax suggests that the pale flax populations tend not to be so diverse, making this is a less likely explanation based on current evidence.

Oil flax varieties occur in both the indehiscent cultivated flax lineages, but fiber varieties appear to be restricted to the IX–X lineage. Note that group VIII, which includes fiber varieties, was formed through a recombination event between groups IX and VII, so these fiber accessions should be considered as part of the IX–X lineage. This phylogenetic restriction suggests that flax was used for oil before fiber, which agreed to previous studies (Allaby et al. 2005; Fu and Allaby 2010). If the sad2 locus was directly responsible for the increase in unsaturated oil composition, then the phylogenetic pattern in Figure 3 suggests that parallel changes happened in the dehiscent cultivated flax and indehiscent cultivated flax groups. The data support multiple independent pathways of domestication of flax for oil composition. Therefore, it is likely that fiber varieties evolved from a lineage of flax domesticated for oil. In support of this scenario, the oil profile data indicate that fiber flax also showed increased unsaturated fatty acid content despite its usage, suggesting that this is a vestigial feature of fiber flax. The dating analysis further supports this scenario, with an origin of the fiber lineages occurring around 3000 years ago.

Domestication-associated locus-specific analysis

The analysis of the sad2 locus revealed a complex history of cultivated flax that is informative about the origins of oil, fiber, and dehiscent varieties despite the apparent restriction that the locus is specifically associated with the oil production. The results expand on, rather than conflict with, earlier studies (Allaby et al. 2005; Fu 2011). It may be relevant that the trait of oil composition is clearly primary, and so underlies all the flax varieties which all have the trait despite not necessarily being exploited for it. However, it is less clear what is revealed about winter tolerance. The winter tolerant varieties were not topologically restricted in the network as in the case of fiber varieties. It therefore seems likely that winter tolerance preceded fiber production in these lineages, but we have no resolution between oil production and winter tolerance in the indehiscent cultivated flax samples. The oil profile data demonstrate that oil production has been enhanced in all varieties making it much more likely that this domestication-associated trait occurred before winter tolerance. It was not until flax spread from the Near East into the Danube valley some time after the initial domestication that winter tolerance was required (Helbaek 1959; Diederichsen and Hammer 1995). In this case, it is likely that increased phylogenetic resolution could be obtained through the study of a locus specifically associated with winter tolerance.

We suggest that there are some general principles for domestication-locus specific studies, which should be considered in future studies. First, the domestication processes influenced flax traits, and loci governing different traits may have different patterns of genetic diversity, depending on different selection processes and the underlying genetics of the target traits (Fu 2011). Thus, it is important to analyze as many domestication loci as possible to infer the processes in which domestication traits were acquired by cultivated plants. This is, particularly true for the candidate domestication loci without direct function evidence. The sad2 locus is a candidate domestication locus, but not necessarily the most informative one. Inferences based on other related candidate loci such as the fad loci (Banik et al. 2011) may help to expand the historical view presented here. Second, a direct inference of causative domestication loci should always be encouraged for high resolution. However, most loci governing domestication traits are not cloned and sequenced in crops such as flax and so may not be accessible to such inference (Fu and Peterson 2010), which thus limits the power of the locus-specific analysis (Konishi et al. 2008; Blackman et al. 2011). Third, the pattern of genetic diversity in an influenced locus depends in part on the degree of human-mediated selection that has acted on various target traits, and any single locus may capture a variable domestication signal. In this case, the sad2 locus may carry more information on oil selection than the other domestication traits of fiber production, winter habit, and dehiscence, so a bias toward oil selection could exist.

Conclusion

The domestication-associated locus-specific analysis in this study has revealed a complex picture of flax domestication involving multiple paths of domestication, initially for oil. An independent alternative or incomplete domestication trajectory occurred in the dehiscent flax group in which the loss of seed dispersal did not occur. It may be the case that the human-mediated selection pressures were different for these plants than for the indehiscent cultivated flax. Furthermore, a recent origin of fiber varieties is apparent, probably in the order of 3000 yBP. Consequently, it is apparent that despite being a locus that is associated with oil rather than fiber or dehiscence, sad2 has been informative to a degree for more than just oil varieties. However, it is clear that there is a limit to the resolution achievable in that little could be resolved about winter tolerance other than it occurred prior to fiber varieties, and the locus-specific approach would be enhanced by considering more loci relevant to the other traits also, and within the wider context of genome-wide information.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank G. W. Peterson for his technical assistance for the research, K. Richards for his field collection of four pale flax accessions in Greece, O. Kurt for his stimulating discussion on the pale flax distribution in Turkey, R. Zhou for his assistance in oil profiling, and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on the early version of the manuscript.

References

- Allaby RG. Integrating the processes in the evolutionary systems of domestication. J. Exp. Bot. 2010;61:935–944. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allaby RG, Brown TB. Network analysis provides insights into the evolution of 5S rDNA arrays in Triticum and Aegilops. Genetics. 2001;157:1331–1341. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.3.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allaby RG, Peterson GW, Merriwether A, Fu YB. Evidence of the domestication history of flax (Linum usitatissimum) from genetic diversity of the sad2 locus. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2005;112:58–65. doi: 10.1007/s00122-005-0103-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allaby RG, Fuller DQ, Brown TA. The genetic expectations of a protracted model for the origins of domesticated crops. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:3982–13986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803780105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badr A, Müller K, Schäer-Pregl R, El Rabey H, Effgen S, Ibraim HH, Possi C, Rohde W, Salamini F. On the origin and domestication history of barley (Hordeum vulgare. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2000;17:499–510. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banik M, Duguid S, Cloutier S. Transcript profiling and gene characterization of three fatty acid desaturase genes in high, moderate, and low linolenic acid genotypes of flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) and their role in linolenic acid accumulation. Genome. 2011;54:471–483. doi: 10.1139/g11-013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergfjord C, Karg S, Rast-Eicher A, Nosch M-L, Mannering U, Allaby RG, Murphy BM, Holst B. Comment on “30,000-year-old wild flax fibers”. Science. 2010;328:1634. doi: 10.1126/science.1186345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackman BK, Scascitelli M, Kane NC, Luton HH, Rasmussen DA, Bye RA, Lentz DL, Rieseberg LH. Sunflower domestication alleles support single domestication center in eastern North America. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104853108. (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104853108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JM, Burger JC, Chapman MA. Crop evolution: from genetics to genomics. Curr. Opin. Genet. Develop. 2007;17:525–532. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth D. Don't forget the ancestral polymorphisms. Heredity. 2010;105:509–510. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2010.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier S, Niu X, Datla R, Duguid S. Development and analysis of EST-SSRs for flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) Theor. Appl. Genet. 2009;119:53–63. doi: 10.1007/s00122-009-1016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diederichsen A, Fu YB. Phenotypic and molecular (RAPD) differentiation of four infraspecific groups of cultivated flax (Linum usitatissimum L. subsp. usitatissimum. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2006;53:77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Diederichsen A, Hammer K. Variation of cultivated flax (Linum usitatissimum L. subsp. usitatissimum) and its wild progenitor pale flax (subsp. angustifolium (Huds.) Thell.) Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 1995;42:262–272. [Google Scholar]

- Diederichsen A, Raney JP. Seed colour, seed weight and seed oil content in Linum usitatissimum accessions held by Plant Gene Resources of Canada. Plant Breed. 2006;125:372–377. [Google Scholar]

- Doebley JF, Gaut BS, Smith BD. The molecular genetics of crop domestication. Cell. 2006;127:1309–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond AJ, Rambaut A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007;7:214. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Excoffier L, Laval G, Schneider S. Arlequin ver. 3.01: an integrated software package for population genetics data analysis. Evol. Bioinform. Online. 2005;1:47–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. PHYLIP—phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- Forster P, Harding R, Torroni A, Bandelt H. Origin and evolution of native American mtDNA variation: a reappraisal. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1996;59:935–945. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu YB. Genetic evidence for early flax domestication with capsular dehiscence. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2011;58:1119–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Fu YB, Allaby RG. Phylogenetic network of Linum species as revealed by non-coding chloroplast DNA sequences. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2010;57:667–677. [Google Scholar]

- Fu YB, Peterson GW. Characterization of expressed sequence tag derived simple sequence repeat markers for 17 Linum species. Botany. 2010;88:537–543. [Google Scholar]

- Fu YB, Peterson G, Diederichsen A, Richards KW. RAPD analysis of genetic relationships of seven flax species in the genus Linum L. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2002;49:253–259. [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y-X, Li WH. Statistical tests of neutrality of mutations. Genetics. 1993;133:693–709. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.3.693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller D. Contrasting patterns in crop domestication and domestication rates: recent archaeobotanical insights from the old world. Ann. Bot. 2007;100:903–924. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill KS. Riverside, CA: University of California; 1966. Evolutionary relationships among Linum species. Ph.D. thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Gill KS. Linseed. New Delhi, India: Indian Council of Agricultural Research; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Gross BL, Olsen KM. Genetic perspectives on crop domestication. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:529–537. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer K. Das Domestikationssyndrom. Kulturpflanze. 1984;32:11–34. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer K. Linaceae. In: Schultze-Motel J, editor. Rudolf Mansfelds Verzeichnis landwirtschaftlicher und gärtnerischer Kulturpflanzen. Berlin, Bd. 2: Akademie-Verlag; 1986. pp. 710–713. [Google Scholar]

- Hegi G. Illustrierte Flora von Mitteleuropa. [Illustrated flora of Central Europe] Vol. 5. München: Lehmanns Verlag; 1925. pp. 3–38. Part 1. [Google Scholar]

- Helbaek H. Domestication of food plants in the Old World. Science. 1959;130:365–372. doi: 10.1126/science.130.3372.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heun M, Schäfer-Pregl R, Klawan D, Castagna R, Accerbi M, Borghi B, Salamini F. Site of einkorn wheat domestication identified by DNA fingerprinting. Science. 1997;278:1312–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Hillman G. The plant remains from Tell Abu Hureyra: a preliminary report. Proc. Prehist. Soc. 1975;41:70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson RR, Kaplan NL. Statistical properties of the number of recombination events in the history of a sample of DNA sequences. Genetics. 1985;111:147–164. doi: 10.1093/genetics/111.1.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson DH, Bryant D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:254–267. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain RK, Thompson G, Taylor DC, MacKenzie SL, McHughen A, Rowland GG, Tenaschuk D, Coffey M. Isolation and characterisation of two promoters from linseed for genetic engineering. Crop Sci. 1999;39:1696–1701. [Google Scholar]

- Kvavadze E, Bar-Yosef O, Belfer-Cohen A, Boaretto E, Jakeli N, Matskevich Z, Meshveliani T. 30,000-year-old wild flax fibers. Science. 2009;325:1359. doi: 10.1126/science.1175404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knutzon DS, Thompson GA, Radke SE, Johnson WB, Knauf VC, Kridl AC. Modification of Brassica oil by antisense expression of a stearoyl-acyl carrier protein desaturase gene. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:2624–2628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.7.2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi S, Ebana K, Izawa T. Inference of the japonica rice domestication process from the distribution of six functional nucleotide polymorphisms of domestication-related genes in various landraces and modern cultivars. Plant Cell Phyisol. 2008;49:1283–1293. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovach MJ, Calingacion MN, Fitzgerald MA, McCouch SR. The origin and evolution of fragrance in rice (Oryza sativa L.) Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:14444–14449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904077106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li CB, Zhou AL, Sang T. Rice domestication by reducing shattering. Science. 2006;311:1936–1939. doi: 10.1126/science.1123604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–1452. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka Y, Vigouroux Y, Goodman MM, Jesus Sanchez G, Buckler E, Doebley J. A single domestication for maize shown by multilocus microsatellite genotyping. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2002;99:6080–6084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052125199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell PL, Clegg MT. Genetic evidence for a second domestication of barley (Hordeum vulgare) east of the Fertile Crescent. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:3289–3294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611377104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muir A, Westcott N. Flax, the genus Linum. London: Taylor and Francis; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ohlrogge JB, Jaworski JG. Regulation of fatty acid synthesis. Ann. Rev. Plant Physiol. Mol. Biol. 1997;48:109–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.48.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen GJ, Matsuda H, Hagstrom R, Overbeek R. fastDNAml: a tool for construction of phylogenetic trees of DNA sequences using maximum likelihood. Comp. Appl. Biosci. 1994;10:41–48. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purugganan MD, Fuller DQ. The nature of selection during plant domestication. Nature. 2009;457:843–848. doi: 10.1038/nature07895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutschmann F. Molecular dating of phylogenetic trees: a brief review of current methods that estimate divergence times. Diversity Distrib. 2006;12:35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Sang T. Genes and mutations underlying domestication transitions in grasses. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:63–70. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.128827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanklin J, Sommerville C. Stearoyl-acyl-carrier-protein desaturase from higher plants is structurally unrelated to the animal and fungal homologs. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88:2510–2514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomura A, Izawa Ebana K, Ebitani T, Kanegae H, Konishi S, Yano M. Deletion in a gene associated with grain size increased yields during rice domestication. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:1023–1028. doi: 10.1038/ng.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, McKinney S, Green A. Sequence of a cDNA from Linum usitatissimum encoding the stearoyl-acyl carrier protein desaturase. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:1075. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.3.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MT, Thomson MJ, Cho YG, Park YJ, Williamson SH, Bustamante CD, McCouch SR. Global dissemination of a single mutation conferring white pericarp in rice. PLOS Genet. 2007;3:11418–11424. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. Evolutionary relationship of DNA sequences in finite populations. Genetics. 1983;105:437–460. doi: 10.1093/genetics/105.2.437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. Statistical method for testing the neutral mutation hypothesis by DNA polymorphism. Genetics. 1989;123:585–595. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.3.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanno KI, Willcox G. How fast was wild wheat domesticated? Science. 2006;311:1886. doi: 10.1126/science.1124635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammes T. The genetics of the genus Linum. Bibliographica Genetica. 1928;4:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal H, Fu YB, Kurt O, Peterson GW, Diederichsen A, Kusters P. Genetic diversity of cultivated flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) and its wild progenitor pale flax (Linum bienne Mill.) as revealed by ISSR markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2010;57:1109–1119. [Google Scholar]

- Uysal H, Kurt O, Fu YB, Diederichsen A, Kusters P. Variation in phenotypic characters of pale flax (Linum bienne Mill.) from Turkey. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2011 (doi: 10.1007/s10722-011-9663-z) [Google Scholar]

- van Zeist W, Bakker-Heeres JAH. Evidence for linseed cultivation before 6000 BC. J. Archaeolog. Sci. 1975;2:215–219. [Google Scholar]

- Wang RL, Stec A, Hey J, Lukens L, Doebley JF. The limits of selection during maize domestication. Nature. 1999;398:236–239. doi: 10.1038/18435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe KH, Sharp PM, Li WH. Rates of synonymous substitution in plant nuclear genes. J. Mol. Evol. 1989;29:208–211. [Google Scholar]

- Zeder MA, Bradley DG, Emshwiller E, Smith BD. Documenting domestication: new genetic and archaeological paradigms. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: Univ. California Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zohary D, Hopf M. Domestication of plants in the Old World. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 2000. pp. 125–132. [Google Scholar]