Abstract

Drosophila melanogaster is a genetically malleable organism with a short life span, making it a tractable system in which to study mechanical effects of genetic perturbation and aging on tissues, e.g., impaired heart function. However, Drosophila heart-tube studies can be hampered by its bilayered structure: a ventral muscle layer covers the contractile cardiomyocytes. Here we propose an atomic force microscopy-based analysis that uses a linearized-Hertz method to measure individual mechanical components of soft composite materials. The technique was verified using bilayered polydimethylsiloxane. We further demonstrated its biological utility via its ability to resolve stiffness changes due to RNA interference to reduce myofibrillar content or due to aging in Drosophila myocardial layers. This protocol provides a platform to assess the mechanics of soft biological composite systems and, to our knowledge, for the first time, permits direct measurement of how genetic perturbations, aging, and disease can impact cardiac function in situ.

Introduction

Adult Drosophila melanogaster possess an open circulatory system with an abdominally located pulsatile heart tube (1). The simple linear heart contains bilateral rows of contractile cardiomyocytes that form the cardiac lumen, which is aligned with the Drosophila body axis (Fig. 1 a). The anterior conical chamber is the most pronounced muscular region of the heart tube (1,2) and is likely a primary determinant of circulatory flow. Covering the tube is a thin, longitudinal, and ventral muscle layer that extends from the conical chamber and runs nearly the entire length of the heart, creating a bilayered structure (Fig. 1 b) (1,2). The ventral muscle layer tightly associates with the tube (1), making it difficult to remove without compromising underlying cardiomyocyte integrity. Although genetic tools and various imaging techniques (3–5) make perturbing and observing cardiac structure and function possible, corresponding biophysical analyses to monitor how genetic perturbations and aging alter the mechanical environment of soft bilayers do not exist, to our knowledge. Because mechanics directly impacts both form and function across numerous animal models (6), the lack of a biophysical description of the Drosophila conical chamber severely limits our understanding of cardiovascular dynamics in such a genetically tractable system.

Figure 1.

Drosophila melanogaster heart structure and sample geometry. (a) Diagram of the fly, indicating the three major body segments (Abd, abdomen; Thrx, thorax; Hd, head) as well as the heart tube (Hrt) and outlined conical chamber (CC) section of the heart tube. Both ventral (top) and side views (bottom) are shown. (b) Cross-section of CC nanoindentation (top), which is drawn to scale with indicated anatomical dimensions. (Inset) Indenter geometry just as the probe contacts the ventral surface. Fluorescent image of a fly heart (bottom) confirming specimen geometry (CM, cardiomyocyte; VM, ventral muscle; Ind, indenter). Note that the contrast was enhanced for image clarity. (c) Bright-field image of AFM tip indenting the CC centerline with an overlay of a GFP-expressing heart tube.

Atomic force microscopy (AFM) has been the standard biophysical method used to obtain force-indentation curves, which, when fit with a mathematical model of a sphere indenting a material assumed to be homogeneous and thick as compared to indentation depth (7,8), can determine tissue elastic moduli, or stiffness (measured in Pascal, i.e., Pa). For biological materials, such assumptions are not generally valid because the material's composition can be very heterogeneous and are often composed of bonded layers such as the Drosophila heart tube or skin or blood vessels in mammals. When indentations are small, i.e., <10% global strain throughout the bulk material, it is possible to obtain elastic properties of the top layer of such materials as the strain field is not overly influenced by subsequent layers (9–11).

In cases where the top layer is too thin to dissipate the strain from indentation before being influenced by underlying layer(s), correction models need to be applied. Two prominent correction methods include those introduced by Dimitriadis et al. (12) and Clifford and Seah (13). The former method requires that juxtaposed layers have sufficient moduli mismatch such as with cells adhering to a glass coverslip (14,15). The latter method establishes an estimate for when the underlying layer's indentation influences measurement of the top layer based on a ratio of both moduli. These thin-coating analysis methods may not pose a problem for isolated cells such as cardiomyocytes in vitro, which show stiffness changes with maturation (16) and age (17), because isolation simplifies the complex mechanical environment that the cells inhabit in vivo. However, for more representative in situ measurements of intact cells where heterogeneous muscle layers potentially exist, this poses a substantial problem for current analysis methods.

Our goal was to establish a straightforward analysis method for thin biphasic materials, especially those that are biological, where layer properties need not vary dramatically, within a well-characterized model system. The linearized-Hertz method has been previously described for such occasions (18) where the elastic moduli of juxtaposed soft layers can be determined from a single force-indentation curve. Similar analyses have been applied to cell indentation where the cell is assumed to be a bilayer of soft cytosol and rigid cytoskeletal filaments (19,20). However, previous descriptions lack rigorous verification in synthetic polymer models and layered tissues and do not explicitly attribute depth-dependent findings to specific layers. Straightforward methodological explanation and convenient analysis software also appear lacking.

Here, we perform an analysis on model bilayered systems consisting of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) cast in layers and in situ indentation of the conical chamber of the Drosophila heart tube. We hypothesized that RNA interference (RNAi)-mediated myofibrillar disruption and aging would decrease and increase Drosophila cardiac fiber stiffness, respectively. Cardiomyocyte-specific RNAi targeted against myosin heavy chain (MHC), a major myofibrillar component, softened the cardiomyocyte layer of the fly heart without eliciting any significant stiffness change of the ventral layer. Age-induced stiffening in both layers was observed, which suggests wide applicability of our approach to models of cardiovascular aging. Together these data suggest that this analysis method enables direct in situ measurements of dysfunction in diverse, multilayered, biological specimens.

Materials and Methods

Drosophila husbandry and preparation

Flies were maintained at 25°C on standard cornmeal-agar medium. Control (yw) adult female flies were transferred to fresh food every 2–3 days and aged for one or five weeks. UAS-MHC RNAi flies (VDRC transformant ID 105355 KK) were crossed to Hand-Gal4 (II) driver flies (21). The progeny express hairpins targeted against the MHC transcripts, to reduce MHC expression, in a cardiomyocyte-restricted manner. The parental Drosophila RNAi line has an interfering-RNA coding region of a transgene located downstream of the yeast Upstream Activating Sequence. The gene cassette containing the RNAi hairpin remains inactive in the absence of the yeast GAL4 transactivating protein. When flies carrying the UAS-MHC RNAi construct are crossed with flies carrying the GAL4 transcriptional activator, the progeny inherit both genes and will express the RNAi in the same pattern as GAL4. Transgenic RNAi expressed via the UAS/Gal4 system allows manipulation of gene expression in a highly precise spatial fashion with heart-specific Hand drivers. The adult progeny expressing cardiomyocyte-restricted RNAi targeted against MHC were aged for one week (see Fig. 4). Myosin-GFP flies (from http://flytrap.med.yale.edu, flytrap name: YD0783) were used to illustrate heart tube structure (see Fig. 1 b).

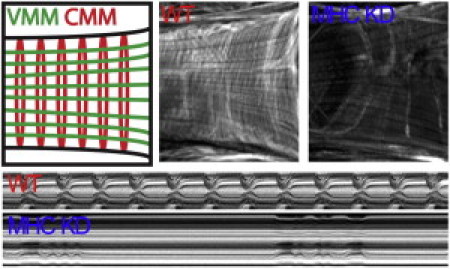

Figure 4.

Myosin heavy chain (MHC) knockdown in Drosophila heart tube. (Top, left to right) Schematic of myofibril orientation in ventral muscle (VMM) and cardiomyocytes (CMM). Fluorescent micrographs of control and MHC RNAi-expressing conical chambers stained with filamentous actin-binding Alexa584-phalloidin. RNAi hearts reveal a marked decrease in cardiomyocyte circumferential myofibrils but not longitudinal ventral muscle myofibrils. (Bottom) M-mode kymograph images of control and MHC RNAi-treated heart tubes. Note impaired movement of RNAi-expressing hearts.

Microsurgery and imaging of Drosophila cardiac tubes

Beating cardiac tubes for each genotype or age group were exposed via microsurgery (n ≥ 20) according to Vogler and Ocorr (22). All procedures were performed at room temperature (18–22°C), under oxygenated hemolymph as previously described (4,22,23). Flies were anesthetized before mounting (dorsal side down) on 25-mm-diameter coverslips and removing the head, ventral thorax, and abdominal cuticle (22). All ventral tissues except the heart were excised. Conical chambers were carefully cleaned of all extraneous debris, e.g., adipose and nervous tissue. Exposed hearts typically exhibited rhythmic contractions for up to 4 h, although immediately before nanoindentation, heart-tube contractions were inhibited by incubation in oxygenated hemolymph containing 10 mM ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA), resulting in heart-tube relaxation including a cessation of flow and pressure gradients and an opening of ostia, i.e., inlet valves on the sides of the heart. Motion-mode kymographs were generated from 30-s bright-field movies of beating hearts taken at rates of 100–200 frames/s using a electron-multiplying charge-coupled device digital camera (Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan) on a DM LFSA microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) with a 10× immersion lens. Motion-modes were created by a previously described MATLAB-based image analysis program (24) (The MathWorks, Natick, MA).

To fluorescently label Drosophila heart tubes, rhythmic contractions were arrested by hemolymph containing 10 mM EGTA. Hearts were fixed in phosphate buffer solution (PBS) containing 4% formaldehyde for 20 min, rinsed three times for 10 min with PBSTx (PBS containing 0.1% Triton-X-100), incubated with Alexa584-phalloidin in PBSTx (1:1000) for 20 min, and washed again three times with PBSTx for 10 min, all at 25°C with gentle agitation. The specimens were mounted on microscope slides with Vectashield (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) and viewed at 10× magnification using an Imager Z1 fluorescent microscope equipped with an Apotome sliding module (Carl Zeiss Optronics, Wetzlar, Germany).

Fabrication of PDMS bilayers

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) made from Sylgard 184 Silicone Elastomer Base (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) was fabricated with varying elastic modulus and thickness by changing the ratio of curing agent/elastomer (1:45 for stiffer and 1:60 for softer PDMS) (25) and the angular velocity (1000–12,000 RPM; see Fig. S1 in the Supporting Material) at which the uncured PDMS was spun, respectively. PDMS was placed on a spincoater (Laurell Technologies; North Wales, PA) and spun for 80 s at 1000 and 12,000 RPM to achieve film heights of 75.0 ± 8.0 μm and 8.5 ± 1.5 μm, respectively (see Fig. S1), as measured by a Dektak 3030 Surface Profiler (Veeco, Santa Barbara, CA). PDMS with a curing ratio of 1:45 and 1:50 was thermoset for 30 min at 60–70°C and PDMS with a curing ratio of 1:60 was thermoset for either 30 min at 60–70°C (1000 RPM) or 24 h at room temperature (12,000 RPM). A bilayer material was made from spinning a 12,000 RPM film (1:60 curing ratio) onto a precured 1000 RPM layer (of indicated curing ratio) and subsequently thermosetting the bilayer for 24 h at room temperature. During thermosetting, the second layer will bind to the primary layer resulting in a bonded, bilayer material. A quantity of 75-μm thick, 1:45 curing ratio PDMS was also respun at 12,000 RPM and thermoset for 24 h at room temperature to mimic the multiple spins required for bilayer fabrication.

Atomic force microscopy indentation and force-curve analysis

All nanoindentation was performed with an MFP-3D Bio Atomic Force Microscope (Asylum Research, Santa Barbara, CA) mounted on a Ti-U fluorescent inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY). We used 120 pN/nm silicon nitride or 7500 pN/nm silicon cantilevers with premounted borosilicate spheres (2 μm radius; Novascan Technologies; Ames, IA) to indent Drosophila heart tubes or PDMS, respectively. Probes were calibrated using a thermal noise method provided by the MFP-3D Bio software (Asylum Research).

For Drosophila heart indentation, yw adult female flies were immobilized on glass supports. Myogenic contractions of surgically exposed heart tubes were arrested and the AFM probe was aligned with the centerline of the conical chamber of the heart tube (Fig. 1 c). A 1-μm2 area was then probed in a 4 × 4 grid of indentations. Both Drosophila and PDMS were indented up to a 100-nm cantilever deflection using approach and retraction speeds of 1 μm/s unless otherwise indicated. Probe deflection and position were monitored during indentation to produce plots of force, F, versus indentation depth, δ. Sample F-δ curves are shown for single and bilayered PDMS (see Fig. S2 a, left). All measurements were performed in liquid using hemolymph (Drosophila) or deionized water containing 2% w/v bovine serum albumin (PDMS). Drosophila nanoindentation was performed only on freshly isolated specimens. No significant probe-sample adhesion was observed.

Force-indentation curves made from a spherical indenter pressing into a sufficiently thick material with uniform properties are commonly analyzed by a method from Hertz (7). In this model, the elastic modulus, E, is directly proportional to the load, F, distributed over the contact area and inversely proportional to indentation depth, δ,

| (1) |

where R is the radius of the sphere and ν is the Poisson ratio of the surface. Hertz analysis is highly dependent on accurately choosing the probe-material contact point, which is difficult for soft materials, and produces only a single elastic modulus (26). Equation 1 was transformed so that Eq. 2 is now linearly dependent on indentation depth changes and the slope is directly proportional to E2/3 (see Fig. 2 b) (18):

| (2) |

Sample F2/3-δ curves are shown for single and bilayered PDMS (see Fig. S2 a, right). From this transformation, elastic modulus can be directly calculated from the slope without the need to determine the contact point. Linearized-Hertz and conventional force-indentation curves (labeled as Hertz) were analyzed using custom-written software in MATLAB that automates linear regression and least-squares fitting analysis of the raw data to Eqs. 1 and 2, respectively. This software is available for download at http://ecm.ucsd.edu/AFM.html, as well as example force curves used in this analysis.

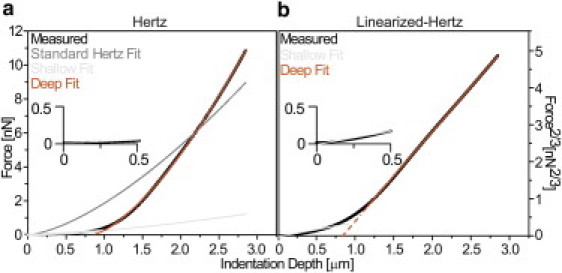

Figure 2.

Nanoindentation analysis of Drosophila myocardium. (a) Nontransformed force-indentation curve was obtained from a one-week-old control fly heart (black). It is shown for all data after the contact point, as determined by a contact-point-seeking algorithm (26). A single, least-squares fit of the Hertz model (Eq. 1; dark gray) did not fit the data well. Two Hertz model analyses, one using the initial contact point and fit range for shallow indentation in panel a (light gray) and another using the x intercept of the deep-fit and maximum indentation in panel a (orange), yield much improved fits relative to a single Hertz model analysis. (b) Linearized-Hertz form of the identical force-indentation curve is shown. Linear fits of shallow (light gray) and deep (orange) indentations are indicated for the range over which the fit was performed. (Dashed lines) The x intercept of the deep-fit. (Inset) Plots magnify the first 500 nm of indentation for each panel.

To outline the software's approach, the F2/3-δ curve is fit from maximum indentation depths backward toward the contact point in an iterative fashion until the coefficient of determination falls to <0.99 (see Fig. S2 b, left). This isolates the fit slope of the deep indentation, which can be converted to an elastic modulus using Eq. 2 (Fig. 2 b and see Fig. S2 b, center). The software then begins a second shallow-indentation fit of the F2/3-δ curve from progressive indentation depths back toward the contact point until the coefficient of determination falls to <0.95 (see Fig. S2 b, right), isolating the portion of the curve for which only the top layer is detected. Note that the contact point does not need to be explicitly calculated as this transformation approach focuses on fitting linear regions of the F2/3-δ curve (see Fig. S2 c). As shown in Fig. S3 c, the first linear region will always be the approach portion of the curve and at least one other linear region will be present and correspond to the material. The difference in slope between these lines will clearly delineate the regions of contact and noncontact.

In Hertzian analysis of F-δ curves from bilayers, we use two new boundary conditions: 1), the indentation limit of the Hertzian shallow fit will be the same as for the linearized-Hertz method, and 2), the F2/3-δ curve's deep fit x intercept (Fig. 2 b, dashed-orange line and see Fig. S2 c, left, dashed-red line) will be used as a virtual contact point to determine the starting point for a Hertzian deep fit. Using these modification produces two fits that mirror the linearized-Hertz method by providing two moduli using coefficients of determination of 0.9 (Fig. 2 a, black data versus light-gray and orange curve fits and see Fig. S2 c, right, black data versus green and red curve fits). Due to error susceptibility differences in curve shape, i.e., F versus F2/3, as well as errors in contact point determination, the modified Hertz fit could not always be computed for each curve fit with the linearized-Hertz method, hence the differences in the number of data points later seen in Figs. 5 and 6.

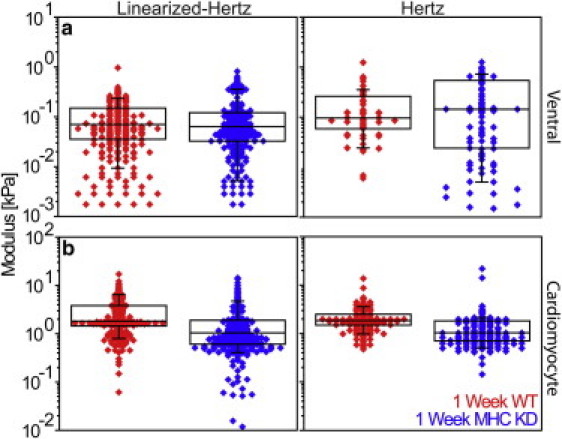

Figure 5.

Myosin heavy chain (MHC) knockdown alters cardiomyocyte stiffness. Linearized-Hertz and modified Hertz analyses for (a) ventral muscle, i.e., shallow fit of Fig. 3, and (b) cardiomyocytes, i.e., deep-fit from Fig. 2. In ventral muscle, there is no observed difference between one-week control and MHC knockdown hearts, regardless of analysis method (p = 0.28 and 0.34, respectively). Cardiomyocytes softened more than twofold, confirming cardiac-specific RNAi expression (p = 4.6 × 10−17 and 1.8 × 10−15 for linearized-Hertz and Hertz method analyses).

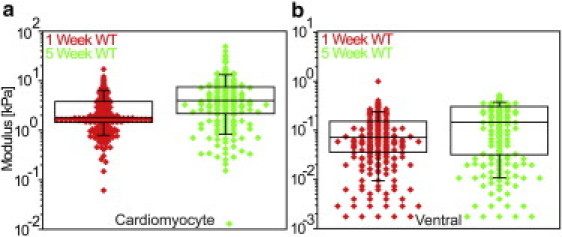

Figure 6.

Aging increases myocardial stiffness in Drosophila. Despite population variation, there is a significant, twofold increase in both (a) cardiomyocyte and (b) ventral muscle stiffness between one- and five-week-old control heart tubes as assessed by the linearized-Hertz method (p = 2.2 × 10−12 and 6.0 × 10−7, respectively).

Sample size and statistical analysis

Indentation analysis was performed approximately at the centerline of the conical chamber for all flies, with typically16 F-δ curves per fly. Measurements were performed on 22, 20, and 21 flies per group yielding 301, 244, and 301 total analyzable curves for one-week-old yw, five-week-old yw, and one-week-old MHC RNAi-expressing heart tubes, respectively. Due to variations between PDMS samples, single samples were indented on at least three different locations on the sample with 192, 128, 74, and 64 curves analyzed for indentations of bilayered, 75-μm thick/1:45 curing ratio, 75-μm thick/1:60 curing ratio, and 8.5-μm thick/1:60 curing ratio PDMS, respectively. PDMS loading rate experiments were analyzed from indentations for at least three different locations on the sample with 64 curves each. All PDMS samples within each plot were made simultaneously from the same solutions. All box-and-whisker plots show, and have statistics computed for, all data pooled together whether from multiple samples or single samples as indicated above. Statistical significance was determined by a Wilcoxon rank-sum test of the stiffness distributions, where statistical significance was assigned when p was at least <0.05.

Results

Indentation analysis

The F-δ behavior of Drosophila myocardium was found not to match Hertz model behavior for indentation of a single material, i.e., Eq. 1 (Fig. 2 a; black versus gray curves). This suggests the heterogeneous muscle layers of the Drosophila heart likely exhibit distinct biophysical properties. A power-law transformation was performed to linearize Eq. 1 (F-δ data) into Eq. 2 (F2/3-δ), referred to as the linearized-Hertz equation because Hertzian material behavior is not represented by a straight line on the plot. Using an algorithm to detect these linear regimes with fitting tolerances at least exceeding R2 > 0.95 in the transformed curve, the plot of force to the 2/3 power versus indentation (F2/3-δ) was found to become linear in two distinct regions with different moduli (Fig. 2 b). We hypothesized that this was due to the distinct bilayered structure of the Drosophila heart where, up to indentations <10% of heart thickness, mechanics are dominated by one material or another depending on indentation depth. The ventral layer is only ∼1–2 μm thick (Fig. 1 b), so linear fits of shallow indentations represent small strains (Fig. 2 b; inset) and produce moduli that agree with previous Hertzian analysis (9,11). When the ventral layer is completely compressed at deep indentations, cardiomyocyte layer properties should appear and represent the second linear portion of the plot as previously predicted by computational finite element analysis (11). The transition region between the two layers is likely dependent on moduli and thickness differences of the layers, as predicted both from indentation and modeling (9–12). However, the model set forth here is focused on linear regions of the transform and not the transition, as the former indicates bulk material stiffness of the single tissue layer bearing the brunt of that strain at that point of indentation (see the schematic in Fig. S4).

To verify this interpretation and analysis, PDMS was fabricated as a synthetic model system with either one or two layers. Each layer contained PDMS of a different polymer curing ratio to modulate stiffness and differed in thickness (see Fig. S1). Samples were indented by AFM, and to confirm linearity, force and force to the 2/3 power were plotted versus cantilever z position (F-z position and F2/3-z position, respectively; see Fig. S3, a and b) to include the approach region before indentation. For linear regions in the F2/3-z-position plot, its derivative, dF2/3/dz, should result in a straight, flat line. As seen in Fig. S3 c, F2/3-z-position plots of bilayered PDMS exhibit three linear regions. These correspond to moduli describing tip approach (which is zero), the top layer, and the second layer (indicated by dashed lines) with the latter two linear regions separated by a nonlinear transition (as illustrated for Drosophila in Fig. S4).

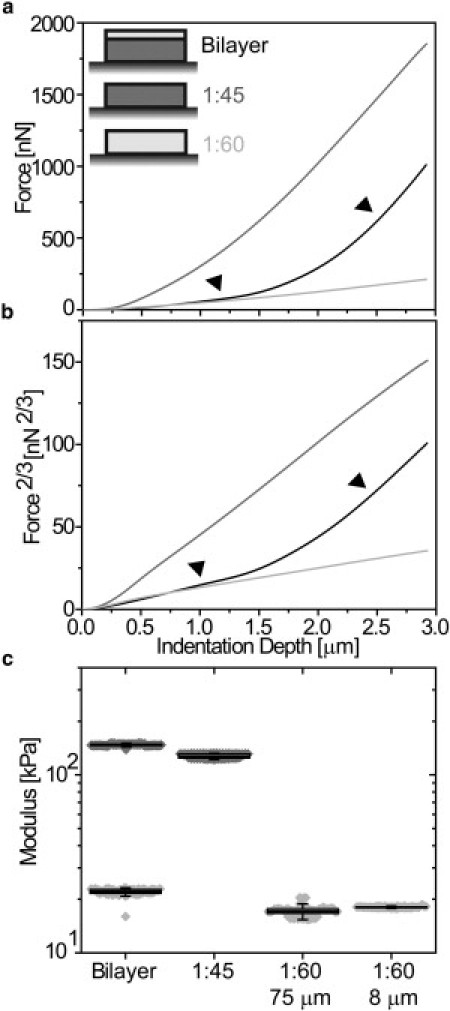

This analysis does not rely on directly determining the contact point between the material and the AFM tip. As with Drosophila, transformation of PDMS force-indentation curves (Fig. 3 a) again shows linear behavior that permits the determination of an elastic modulus over that linear indentation depth range (Fig. 3 b). Single-layer PDMS exhibited a near 10-fold difference in elastic modulus as a function of polymer curing ratio, independent of PDMS thickness (Fig. 3 c). For bilayer PDMS, the slope of the force-indentation curve and its transform is quite shallow at first as the indentation depth of the transition between top and bottom layers was found to depend on thickness and moduli differences. Increasing thickness of the top layer allowed for increased compression before the effects of the bottom layer were observed (see Fig. S5, a and b, blue versus green). On the other hand, increasing bottom layer modulus allowed for less compression before onset of the modulus transition (see Fig. S5, a and b, green versus red).

Figure 3.

Indentation of single and bilayer polymer materials. (a) Force-indentation curves of single-layer polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) gels with a curing ratio of 1:60 (light shaded) and 1:45 (dark shaded) versus a bilayer PDMS gel (solid). (Arrows) Regions of similar behavior with single layer gels. (b) Force curve data plotted in a linearized-Hertz form using Eq. 2, i.e., F2/3-δ. (Arrows) Regions of similar slope (and moduli) with single layer gels. (c) Box (25 and 75 percentile) and whisker (10 and 90 percentile) plots with overlapping data points of PDMS bilayers and monolayers with curing ratios and thickness indicated.

This result is consistent with thin-film AFM models where thicker and less mismatched layers require less correction due to lower strains (9,11,12,27). Most importantly, the elastic modulus of the top layer is nearly identical to the single layer modulus of the same curing ratio, irrespective of its thickness (Fig. 3 c). After a transition region where both layers are likely compressed resulting in nonlinear behavior, transformation using Eq. 2 again linearizes data and permits the determination of a second modulus (Fig. 3 c), which is not possible for thin-film AFM models (9,11,12,27). For bilayered PDMS, when the bottom layer was compared to single layered PDMS of the same curing ratio, layer elastic moduli were nearly identical. It should be noted that PDMS is a loading rate-sensitive material (28), and when indented at different loading rates, both single and bilayered materials had proportionately increased moduli as a function of PDMS curing ratio (see Fig. S5 c). For this reason, Drosophila measurements were made at the same loading rate.

Cardiac-specific MHC knockdown results in cardiomyocyte-specific softening

Myofibrillar disassembly likely leads to changes in myocardial stiffness. To verify that our analysis can determine independent mechanical changes in situ in a multilayered system such as the adult Drosophila heart tube, cardiac-specific (21) RNAi for myosin heavy chain (MHC) was used to genetically modify cardiomyocytes and not ventral muscle fibers. Cardiomyocyte-restricted MHC knockdown induced a marked reduction in myofibrillar density in 1-week-old flies relative to control (Fig. 4; top). Moreover, severely depressed wall motion and loss of rhythmic contractions confirmed extensive functional impairment of the heart tube (Fig. 4; bottom).

Both F-δ and F2/3-δ plots measured from EGTA-arrested hearts indicated that there was no difference in slope at shallow indentation depths, corresponding to a lack of change in passive mechanics of the thinner ventral muscle. Interestingly, there was an appreciable difference between RNAi-treated and control flies at deep indentation depths, corresponding to differences in the mechanical properties of the cardiomyocytes (see Fig. S6). Fits from the linearized-Hertz and the Hertz analysis method based on Eq. 1 confirmed that cardiac-specific RNAi did not significantly change median ventral muscle stiffness, i.e., <10% (Fig. 5 a), but did cause a significant twofold reduction in median cardiomyocyte stiffness (Fig. 5 b). Despite the RNAi treatment, it is important to note that the cardiomyocytes remained an order-of-magnitude stiffer than the ventral muscle, ensuring the accuracy of our detection technique.

Cardiac stiffness increases with age

In addition to robust genetic tools that make the organism a highly tractable system for investigating cardiac biology, Drosophila ages rapidly and therefore serves as an efficient model for studying senescent-dependent changes in myocardial properties. Hence we monitored heart-tube stiffness as a function of age. Contrary to the effect of cardiac-restricted genetic manipulation of MHC (see Fig. S6; compare red and blue curves), F-δ and F2/3-δ plots indicated an increase in slope for both shallow and deep indentation depths of EGTA-arrested hearts in five-week-old relative to one-week-old control flies (compare green and red curves, respectively). Using the linearized-Hertz method, five-week-old flies were found to exhibit a statistically significant, 2.5-fold increase in median cardiomyocyte stiffness versus one-week-old flies (Fig. 6 a). Ventral stiffness increased 50% though remained an order-of-magnitude softer than cardiomyocytes at five weeks of age (Fig. 6 b).

Discussion

Analysis advantages for soft bilayered materials

Analysis of force-indentation curves from soft materials is often complicated by difficulties in determining the contact point, the point at which the AFM probe contacts the material, e.g., the F-δ curve slope may only be slightly higher than the thermal noise associated with probe fluctuations. The softness of many biological materials and the possibility for multiple layers of different materials further complicate the analysis (26). For layered materials, previous corrections to the Hertz model are useful specifically where the stiffness of one substrate is orders-of-magnitude greater than the other (12).

To date, there have only been limited observations of the phenomenon we observed in Drosophila myocardium, where both layers are comprised of soft materials. For example, linearized-Hertz analysis of cell indentation has shown two separate depth-dependent moduli (19). Varying stiffness by ablating cytoarchitectural proteins has indicated that at least one of these depth-dependent moduli is related to the cytoskeleton (20). However, the most complete analysis of this phenomenon has involved finite element modeling of a biphasic material consisting of a soft monolayer and a stiffer inclusion. Force-indentation curves of monolayered and biphasic materials showed identical behavior at shallow indentation depths.

However, the forces felt at deeper indentation depths within the biphasic material were greater as compared to monolayer indentation (11). Though finite element methods have given critical insight into how bilayers behave during nanoindentation qualitatively, rigorous quantification of this phenomenon in biological specimens was not well described. By using a linearized-Hertz fit with sufficient indentation depth for both layered PDMS and the Drosophila heart tube, we further demonstrate the ability to determine stiffness of separate layers with similar mechanical properties but do so within well-characterized soft, bilayered materials in situ. Although this linearized-Hertz model sufficiently describes 2–3 μm indentations, other well-established nonlinearly elastic indentation models may be more appropriate for deeper indentation or more complex cytoarchitectures (29).

It is important to note three considerations for this analysis method as it relates to either model system: First, the conical chamber of Drosophila is slightly rounded with a lateral pitch change of <1° per μm (Fig. 1 b). By using a 2-μm radius sphere at the center-line of the tube, this curvature likely has negligible effects. Second, for all of the indentations performed, the linearized-Hertz fits converged to a solution for all curves given fitting tolerances. Even with adjustments made to the Hertz approach, e.g., fitting a deep indentation region with a virtual second contact point, less than half of the data could be fit by standard Hertzian analysis, accounting for differences in scatter plot density (Figs. 5 and 6). This indicates that linearization produces a much more robust determination of biophysical parameters for bilayers because AFM measures relative z position and force, which is the only measure needed for the linearized method. Third, the Hertz and linearized-Hertz models are mathematically identical, so they should yield similar results, although Hertz fitting requires three fitting parameters (z position and force at contact and the elastic modulus for which the fit is calculated) versus one parameter for linearized-Hertz. Because AFM software displays relative indenter z position and force, one must use algorithms to calculate the contact point, which is often done over a single range of z positions and applied to a single Hertz model (26). For a monolayer, model differences are negligible as only one contact point is needed. This is directly tested here for shallow indentations into the ventral muscle where both methods yield identical median moduli (Fig. 5 a).

To accurately measure bilayered materials with Hertzian analysis, a contact point for each layer must be obtained from separate analysis ranges. Otherwise, single contact point analysis will lead to a single, inaccurate modulus and poorly fit data (Fig. 2 a, gray versus black). Because imprecise contact-point-dependent analysis can introduce errors up to several-fold even for monolayers (30), this multicontact approach for bilayers is likely to be increasingly error-prone. Though methods that diminish the error introduced by a poorly calculated contact point have been established, these still require such a calculation (31). In comparison, the linearized-Hertz method relies only on the slope of the curve and thus is a truly contact-point-independent analysis method. Proper analysis only requires that the user indent the material to an appropriate depth and then fit data based on relative differences within the force-indentation curve.

In the case of bilayered materials, linearization of a sufficiently deep force-indentation curve reveals two straight lines both visually (Fig. 2 b, black) and through fitting (Fig. 2 b, orange and light gray). For materials consisting of three or more sufficiently thick layers, as compared to the indenter radius, linearized-Hertz analysis would reveal three lines in the same way. Thus the advantage of this analysis method is that the F2/3-δ plots of linearized-Hertzian analysis give straight lines that are easy to fit, making this fitting method more user-friendly and intuitive to novice biological AFM users.

Analyzing the origins of biological stiffness

Direct application of sufficient force to ventrally exposed, beating Drosophila myocardium results in the attenuation of rhythmic beating. A 50-μm indentation reportedly causes a total occlusion of the larval Drosophila heart tube (32). This level of myocyte deformation is known to open the stretch-sensitive, calcium-permeable transient receptor potential channel Painless, which would increase intracellular free calcium and potentially augment force production (32). It is critical to note that the AFM indentation performed here is more than an order-of-magnitude smaller than the indentation that induced cardiomyocyte arrest. For example, a 2-μm-radius sphere indenting the adult Drosophila heart tube would create no more than 0.151% strain when examined in cross section (see Fig. S7). Thus, nominal indentation of a relaxed heart with open ostial valves and a sufficiently thick wall (Fig. 1 b) would produce negligible global tube compression and not require a more complicated indentation model accounting for fluid compression within the tube.

Moreover, this small amount of strain is below the previously observed strain required for channel activation (33) and emphasizes that this AFM method seeks to minimize strain to measure an intrinsic, passive material property and not a mechanobiological response. If, however, our indentation caused Painless or additional stretch-sensitive channels to open in adult hearts, rapid myocyte stiffening should have been observed with the linearized F2/3-δ curve becoming nonlinear, which was not the case (see Fig. S2) and suggests active stiffening is not transpiring.

How genetics and aging affect Drosophila heart tube stiffness

Due to its short life-cycle and genetic tractability, Drosophila is an ideal model organism for investigating senescent-dependent changes in cardiac biology with relatively high temporal throughput. A recent Drosophila genome-wide screen found that expression of a significant number of adhesion-related genes was vital to heart performance (34). Age-related differences in expression of these genes would likely affect cardiac function. The analysis method described here would thus serve as a useful biophysical method to complement current microscopy analyses used to identify the passive mechanical role played by these proteins, e.g., myofibril disassembly and decreased fractional shortening—the difference in heart-tube diameter during systole relative to diastole (5,23).

This is especially true for age-related studies considering the significant age-related increase in myocardial stiffness observed by AFM (Fig. 6). Our method could also act as a screen and/or confirm the function of mammalian-conserved, mechanically sensitive proteins, such as has been implicated with the cell adhesion molecules fas and DE-cadherin and the extracellular matrix protein laminin A (35). These proteins are essential for tube formation and maintenance, respectively, and their ablation, which is known to cause breaks in the heart tube during embryonic development (35), may likely impair force transduction, decrease sarcomere assembly, and thus decrease myocyte stiffness. This connection is highly plausible given the link shown here between MHC knockdown, reduced myofibrillar content (Fig. 4), and cell softening (Fig. 5).

It is important to note that genetic changes can be localized to cardiomyocytes with the Hand-Gal4 (II) driver (21) so that comparisons of control and RNAi-treated Drosophila can occur in a cardiac-autonomous fashion in the absence of other defects. For example, Fig. 5 confirms the ability of our method to parse individual tissue properties between the muscle layers and likely does not reflect contributions from matrix between the muscle layers as it is exceedingly thin, i.e., tens of nanometers (1), compared to the muscle layers and the size of our indenter. Moreover, the lack of change in ventral muscle despite MHC knockdown in adjacent cardiomyocytes also suggests that there is little interdependence between the two muscle layers as observed classically in single cells (36).

One complication of using biological specimens is the significant animal-to-animal variation in stiffness; measurement variance within a given fly, for example, ranged from 5 to 40% as a function of age (1–5 weeks) and up to 20% with MHC knockdown. Although this variance is similar to that seen with other AFM cell and tissue analyses (9,16), the relatively high temporal throughput of the Drosophila model for age-or disease-related analyses combined with the automated analysis of our method makes the number of specimens analyzed limited only by the ability of the end-user to generate AFM-ready samples. We found that sufficient statistical power was achieved, i.e., significant differences in populations as determined by Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, when sample populations exceeded 20. With an average measurement time of 20 min per fly, a sufficiently large data set for a given fly genotype can be obtained in a matter of hours, making this technique suitable for the average end-user to perform relatively large high throughput screens.

We believe that this linearized-Hertz method of force-indentation analysis can provide biologists with a direct biophysical understanding of how specific perturbations alter tissue function, which cannot be done with preexisting genetic tools and imaging methods (3–5). Though we present analysis in the fly heart tube here, and to our knowledge the first demonstration of direct, passive mechanical in situ measurements of cellular bilayers, applications in other layered tubes and tissues that previously could not be analyzed biophysically, such as blood vessels and skin, respectively, can be easily adapted to this method, making it a useful tool to the biological community.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Rolf Bodmer, Nakissa Alayari, and Joan Choi (Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute) for support and for assistance with Drosophila microsurgery and Ludovic Vincent (University of California, San Diego) for assistance with microfabrication.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (1DP02OD006460 to A.J.E.), American Heart Association (10SDG4180089 to A.C.), and a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Training Grant on Integrative Bioengineering of Heart, Vessels and Blood (1T32HL105373-01).

Footnotes

Anthony Cammarato's present address is Department of Medicine, Division of Cardiology, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons-Attribution Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/), which permits unrestricted noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Contributor Information

Anthony Cammarato, Email: acammara@sanfordburnham.org.

Adam J. Engler, Email: aengler@ucsd.edu.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Miller A. The internal anatomy and histology of the imago of Drosophila melanogaster. In: Demerec M., editor. Biology of Drosophila. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; Cold Spring Harbor, NY: 1950. pp. 420–534. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wasserthal L.T. Drosophila flies combine periodic heartbeat reversal with a circulation in the anterior body mediated by a newly discovered anterior pair of ostial valves and ‘venous’ channels. J. Exp. Biol. 2007;210:3707–3719. doi: 10.1242/jeb.007864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolf M.J., Amrein H., Rockman H.A. Drosophila as a model for the identification of genes causing adult human heart disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:1394–1399. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507359103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ocorr K., Reeves N.L., Bodmer R. KCNQ potassium channel mutations cause cardiac arrhythmias in Drosophila that mimic the effects of aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:3943–3948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609278104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taghli-Lamallem O., Bodmer R., Cammarato A. Genetics and pathogenic mechanisms of cardiomyopathies in the Drosophila model. Drug Discov. Today Dis. Models. 2008;5:125–134. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engler A.J., Humbert P.O., Weaver V.M. Multiscale modeling of form and function. Science. 2009;324:208–212. doi: 10.1126/science.1170107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hertz H. On the fixed contact of elastic bodies [Über die berührung fester elastischer körper] J. Reine Angew. Mathematik. 1882;92:156–171. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radmacher M. Measuring the elastic properties of living cells by the atomic force microscope. Methods Cell Biol. 2002;68:67–90. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(02)68005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engler A.J., Richert L., Discher D.E. Surface probe measurements of the elasticity of sectioned tissue, thin gels and polyelectrolyte multilayer films: correlations between substrate stiffness and cell adhesion. Surf. Sci. 2004;570:142–154. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reinhart-King C.A., Dembo M., Hammer D.A. Endothelial cell traction forces on RGD-derivatized polyacrylamide substrata. Langmuir. 2003;19:1573–1579. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roduit C., Sekatski S., Kasas S. Stiffness tomography by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 2009;97:674–677. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dimitriadis E.K., Horkay F., Chadwick R.S. Determination of elastic moduli of thin layers of soft material using the atomic force microscope. Biophys. J. 2002;82:2798–2810. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75620-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clifford C.A., Seah M.P. Nanoindentation measurement of Young's modulus for compliant layers on stiffer substrates including the effect of Poisson's ratios. Nanotechnology. 2009;20:145708. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/20/14/145708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahaffy R.E., Park S., Shih C.K. Quantitative analysis of the viscoelastic properties of thin regions of fibroblasts using atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 2004;86:1777–1793. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74245-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rotsch C., Jacobson K., Radmacher M. Dimensional and mechanical dynamics of active and stable edges in motile fibroblasts investigated by using atomic force microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:921–926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.3.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collinsworth A.M., Zhang S., Truskey G.A. Apparent elastic modulus and hysteresis of skeletal muscle cells throughout differentiation. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C1219–C1227. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00502.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lieber S.C., Aubry N., Vatner S.F. Aging increases stiffness of cardiac myocytes measured by atomic force microscopy nanoindentation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2004;287:H645–H651. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00564.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo S., Akhremitchev B.B. Packing density and structural heterogeneity of insulin amyloid fibrils measured by AFM nanoindentation. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:1630–1636. doi: 10.1021/bm0600724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carl P., Schillers H. Elasticity measurement of living cells with an atomic force microscope: data acquisition and processing. Pflugers Arch. 2008;457:551–559. doi: 10.1007/s00424-008-0524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim Y., Kim M., Kim J. Characterization of cellular elastic modulus using structure based double layer model. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2011;49:453–462. doi: 10.1007/s11517-010-0730-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han Z., Yi P., Olson E.N. Hand, an evolutionarily conserved bHLH transcription factor required for Drosophila cardiogenesis and hematopoiesis. Development. 2006;133:1175–1182. doi: 10.1242/dev.02285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vogler G., Ocorr K. Visualizing the beating heart in Drosophila. J. Vis. Exp. 2009;31:1425. doi: 10.3791/1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cammarato A., Dambacher C.M., Bernstein S.I. Myosin transducer mutations differentially affect motor function, myofibril structure, and the performance of skeletal and cardiac muscles. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2008;19:553–562. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-09-0890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fink M., Callol-Massot C., Ocorr K. A new method for detection and quantification of heartbeat parameters in Drosophila, zebrafish, and embryonic mouse hearts. Biotechniques. 2009;46:101–113. doi: 10.2144/000113078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goffin J.M., Pittet P., Hinz B. Focal adhesion size controls tension-dependent recruitment of α-smooth muscle actin to stress fibers. J. Cell Biol. 2006;172:259–268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200506179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engler A.J., Rehfeldt F., Discher D.E. Microtissue elasticity: measurements by atomic force microscopy and its influence on cell differentiation. Methods Cell Biol. 2007;83:521–545. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(07)83022-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clifford C.A., Seah M.P. Modeling of nanomechanical nanoindentation measurements using an AFM or nanoindenter for compliant layers on stiffer substrates. Nanotechnology. 2006;17:5283–5292. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun Y., Walker G.C. Viscoelastic response of poly(dimethylsiloxane) in the adhesive interaction with AFM tips. Langmuir. 2005;21:8694–8702. doi: 10.1021/la050448j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin D.C., Shreiber D.I., Horkay F. Spherical indentation of soft matter beyond the Hertzian regime: numerical and experimental validation of hyperelastic models. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2009;8:345–358. doi: 10.1007/s10237-008-0139-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azeloglu E.U., Costa K.D. Atomic force microscopy in mechanobiology: measuring microelastic heterogeneity of living cells. In: Braga P.C.R., Ricci D., editors. Atomic Force Microscopy in Biomedical Research Methods and Protocols. Springer; New York: 2011. pp. 303–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.A-Hassan E., Heinz W.F., Hoh J.H. Relative microelastic mapping of living cells by atomic force microscopy. Biophys. J. 1998;74:1564–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77868-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sénatore S., Rami Reddy V., Lalevée N. Response to mechanical stress is mediated by the TRPA channel painless in the Drosophila heart. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:9. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Charras G.T., Horton M.A. Single cell mechanotransduction and its modulation analyzed by atomic force microscope indentation. Biophys. J. 2002;82:2970–2981. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75638-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neely G.G., Kuba K., Penninger J.M. A global in vivo Drosophila RNAi screen identifies NOT3 as a conserved regulator of heart function. Cell. 2010;141:142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haag T.A., Haag N.P., Hartenstein V. The role of cell adhesion molecules in Drosophila heart morphogenesis: faint sausage, shotgun/DE-cadherin, and laminin A are required for discrete stages in heart development. Dev. Biol. 1999;208:56–69. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vogel V., Sheetz M. Local force and geometry sensing regulate cell functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006;7:265–275. doi: 10.1038/nrm1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.