Abstract

The exocrine salivary glands of mammals secrete K+ by an unknown pathway that has been associated with efflux. However, the present studies found that K+ secretion in the mouse submandibular gland did not require , demonstrating that neither cotransport nor K+/H+ exchange mechanisms were involved. Because did not appear to participate in this process, we tested whether a K channel is required. Indeed, K+ secretion was inhibited >75% in mice with a null mutation in the maxi-K, Ca2+-activated K channel (KCa1.1) but was unchanged in mice lacking the intermediate-conductance IKCa1 channel (KCa3.1). Moreover, paxilline, a specific maxi-K channel blocker, dramatically reduced the K+ concentration in submandibular saliva. The K+ concentration of saliva is well known to be flow rate dependent, the K+ concentration increasing as the flow decreases. The flow rate dependence of K+ secretion was nearly eliminated in KCa1.1 null mice, suggesting an important role for KCa1.1 channels in this process as well. Importantly, a maxi-K-like current had not been previously detected in duct cells, the theoretical site of K+ secretion, but we found that KCa1.1 channels localized to the apical membranes of both striated and excretory duct cells, but not granular duct cells, using immunohistochemistry. Consistent with this latter observation, maxi-K currents were not detected in granular duct cells. Taken together, these results demonstrate that the secretion of K+ requires and is likely mediated by KCa1.1 potassium channels localized to the apical membranes of striated and excretory duct cells in the mouse submandibular exocrine gland.

Keywords: salivary gland, potassium secretion, calcium-activated K channels, duct cells

Maxi-K channels are associated with a diverse array of cellular functions including, for example, smooth muscle contractility (22, 37), cell volume control (32, 42), neuronal action potentials (26, 27, 39), hearing loss in cochlear hair cells (31, 34), and K+ secretion by the renal tubules and the crypt cells of the distal colon (29, 38). We have previously demonstrated that the KCa1.1 gene (also known as Kcnma1) encodes the maxi-K channel in the acinar cells of parotid and submandibular exocrine glands (32, 33). These large-conductance K channels are gated both by voltage and by Ca2+ (25, 32). KCa1.1 acts in concert with the intermediate-conductance, Ca2+-activated K channel (KCa3.1) to regulate fluid secretion. The salivary glands of mice lacking both KCa1.1 and KCa3.1 K channels secrete ~70% less fluid (32, 33). KCa1.1 channels have also been linked to K+ secretion in the crypt cells of the mouse distal colon (38). This latter study found that Ca2+-dependent K+ secretion in this epithelium relies on KCa1.1 but not KCa3.1 expression.

Exocrine glands, such as the salivary, lacrimal, and sweat glands, secrete fluid enriched in K+, often more than an order of magnitude higher than the K+ concentration found in plasma (1, 3, 5, 36). Salivary gland secretions maintain homeostasis of the upper gastrointestinal and oral cavity by generating a barrier to microbial, chemical, and mechanical insults (21, 40, 43). This primary function of saliva depends on numerous secretory proteins as well as the ion composition. The K+ concentration of saliva modulates the activity and growth of the oral microbial flora, which include many species considered to be pathogenic (7, 17, 45–47).

The primary fluid secreted by salivary gland acinar cells has an osmolality of ~300–310 mosmol/kgH2O and a plasma-like monovalent ion composition that is high in Na+ and low in K+ (18, 19, 50). As the primary fluid transits through the ductal network, K+ is secreted, and at the same time most of the Na+ produced by acinar cells is reabsorbed. Both K+ secretion and Na+ reabsorption are flow rate dependent, such that as the flow rate decreases, the concentration of Na+ ([Na+]) decreases and the K+ concentration ([K+]) increases, although the magnitude of such changes are gland type and species specific (5, 24). The inverse relationship between Na+ uptake and K+ secretion suggests a functional link between these two processes, although the ion transport mechanisms involved are not defined in salivary glands. The final secreted fluid is typically hypotonic (<200 mosmol/kgH2O) because the ductal epithelium is essentially water impermeant, and NaCl reabsorption exceeds K+ secretion (18, 19, 50).

The molecular identity of the K+ secretion pathway(s) is (are) unknown in salivary glands. It has been postulated that K+/H+ exchange and/or cotransport mechanisms may be involved in K+ secretion, although a major role for a K channel has not been excluded in this process (5). Consistent with this latter K+ secretion model, we recently observed that the [K+] of the parotid gland saliva secreted in vivo is reduced in KCa1.1-deficient mice, suggesting that the maxi-K channel is required for K+ secretion (32). However, this study did not address the molecular mechanisms involved, nor did it rule out the possibility that disruption of the KCa1.1 gene may have changed the expression of other K+ secretion pathways. It is important to note that a maxi-K-like current has not been previously detected in duct cells (9), the theoretical site of K+ secretion (5, 21). Thus, the function of the maxi-K channel in the K+ secretion process remains to be defined.

In vivo saliva production does not always provide results that accurately reveal the role of the different components of the saliva secretion mechanism (33). Consequently, the present studies used an ex vivo, perfused submandibular gland preparation that eliminates circulating factors and neural inputs that complicate the interpretation of in vivo experiments and allows for strict control of the perfusate (e.g., agonist concentration, introduction of inhibitors, ion composition, and osmolality). Taking advantage of the robust K+ secretion mechanism in the mouse submandibular gland, we found that the final K+ concentration was independent of , whereas K+ secretion was dramatically reduced by the maxi-K channel blocker paxilline. Furthermore, disruption of the KCa1.1 K channel gene, but not KCa3.1, also dramatically inhibited K+ secretion. KCa1.1 expression was for the most part limited to the apical membranes of striated and excretory duct cells. Collectively, our findings show that the KCa1.1 channel mediates K+ efflux across the apical membranes of the ducts in the mouse submandibular gland.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

General methods

Gene targeting and genotyping protocols for KCa1.1 and KCa3.1 knockout mice were as previously described (2, 22). Mice were housed in microisolator cages with ad libitum access to laboratory chow and water during 12:12-h light-dark cycles. Sex-and age-matched adult mice between 2 and 5 mo old were used. All experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Resources Committee of the University of Rochester. Reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise indicated.

Ex vivo, perfused submandibular glands

As previously described (33), the main artery to the submandibular salivary gland of anesthetized mice (intraperitoneal injection of 400 mg chloral hydrate/kg) was cannulated (31 gauge, Harvard Apparatus) and perfused at a rate of 0.8 ml/min (IPC High precision tubing pump; Ismatec, Glattbrugg, Switzerland). The submandibular gland was then removed, and the distal end of the salivary duct was inserted into a calibrated glass capillary tube (Sigma-Aldrich). The perfusion solution contained (in mM) 120 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 4.3 KCl, 1.0 MgCl2, 1.0 CaCl2, 5 glucose, and 10 HEPES, at pH 7.4 with NaOH. -containing solutions were thoroughly gassed with 5% CO2-95% O2 before the pH was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. -free solutions were made by equimolar substitution of 25 mM NaHCO3 by NaCl, with the addition of the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor acetazolamide (0.1 mM). -free solutions were gassed with 100% O2. Secretion was stimulated at room temperature (RT; 20–22°C) by the addition of 0.5 μM carbachol to the perfusion solution. The ex vivo salivary flow rate was expressed at 1 min intervals as μl/min.

In vivo collection of submandibular gland saliva

Mice were anesthetized as described above. Salivary gland-specific saliva was collected by isolating the ducts from each submandibular gland and inserting their distal ends into a calibrated glass capillary tube as described (10). Body temperature was maintained at 37°C with a regulated blanket (Harvard Apparatus, Holliston, MA), and the trachea was incised to ensure a patent airway. Secretion was stimulated by intraperitoneal injection of pilocarpine-HCl (10 mg/kg body wt). In vivo stimulated saliva was collected for 30 min.

Flow rate, osmolality, and ion concentration measurements

Saliva was stored at −86°C until analysis. At the end of the saliva collection period, the submandibular glands were blotted dry and weighed. Sodium and potassium concentrations were measured by atomic absorption (Perkin-Elmer 3030 spectrophotometer). Chloride activity was measured with an Orion Research Expandable Ion Analyzer 940. Sample osmolality was obtained with a vapor pressure osmometer (model 5500; Wescor, Logan, UT).

Immunohistochemistry

Mice were anesthetized as described above before arterial perfusion (Sage Thermo Orion Syringe Pump model M361) via the left ventricle, initially with RT PBS, followed by PBS containing 2% picric acid and 2% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. The glands were incubated overnight in the same fixative solution at 4°C and for another night at RT, rinsed in PBS, and then stored in 70% ethanol at 4°C before being embedded in paraffin. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked with 10% H2O2 for 10 min before overnight incubation at RT with anti-BKCa antibody (Alomone Labs, Jerusalem, Israel) diluted 1:100 in PBS and 0.5% BSA. This antibody was generated against amino acids 1098–1196 of the intracellular COOH terminus of mouse KCa1.1 (accession no. A48206). The Vectastain ABC Kit and Peroxidase Substrate Kit DAB were used to visualize expression per the manufacturer’s directions (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA).

Electrophysiology

Measurements of K+ currents in mouse submandibular acinar and granular duct cells were made at RT with the patch-clamp technique in the whole cell configuration (33). Acinar cells were isolated as previously described (33). Granular duct cells were isolated as follows: glands were dissected from exsanguinated mice under CO2 anesthesia, minced in Ca2+-free Earle’s minimal essential medium (SMEM; Biofluids, Rockville, MD) containing 0.012% trypsin, 0.05 mM EDTA, 2 mM glutamine, and 1% BSA, and agitated for 15 min at 37°C. After brief centrifugation, the pellet was resuspended in a fresh aliquot of the same solution and incubated for an additional 15 min. Digestion was stopped with 2 mg/ml of soybean trypsin inhibitor, and the tissue was further dispersed by two sequential treatments of 10 min each with LiberaseRI (0.15 U/ml; Roche) in SMEM-Ca2+-free medium also containing 2 mM glutamine and 1% BSA. The dispersed cells were centrifuged and washed with basal medium Eagle (BME; GIBCO BRL). The final pellet was resuspended in BME with 2 mM glutamine and cells plated onto poly-L-lysine-coated glass coverslips for electrophysiological recordings.

Electrophysiological data were acquired using Axopatch 200B amplifier and Digidata 1320A digitizer (Axon Instruments, Foster City, CA). Whole cell recordings were performed with the low-pass filter set at 1 kHz and a sampling rate of 50 kHz. The K+ currents were elicited by 40-ms step pulses from −110 to +70 mV in 20-mV intervals applied every 0.5 s from the holding potential of −70 mV. The data were acquired and analyzed using Axon pClamp software (version 9.2). Pipettes from Corning 8161 patch glass (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT) were pulled to give a resistance of 2–3 MΩ in the solutions described below. The external solution contained (in mM) 150 Na-glutamate, 5 K-glutamate, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.2. The pipette solution contained (in mM) 135 K-glutamate, 5 EGTA, 3 CaCl2, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.2. The level of free Ca2+ in the external and pipette solutions was calculated to be ~0.4 mM and ~250 nM, respectively (WEBMAXC; http://www.stanford.edu/~cpatton/webmaxcS.htm). The use of glutamate instead of Cl− effectively eliminated Cl channel currents. The measured relevant junction potential in these recordings was <4 mV, sufficiently small that no correction was made. The osmolality of solutions was measured and adjusted to isotonic with sucrose.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired Student’s t-test with equal variance. Results were expressed as means ± SE. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

K+ secretion is independent of in the mouse submandibular gland

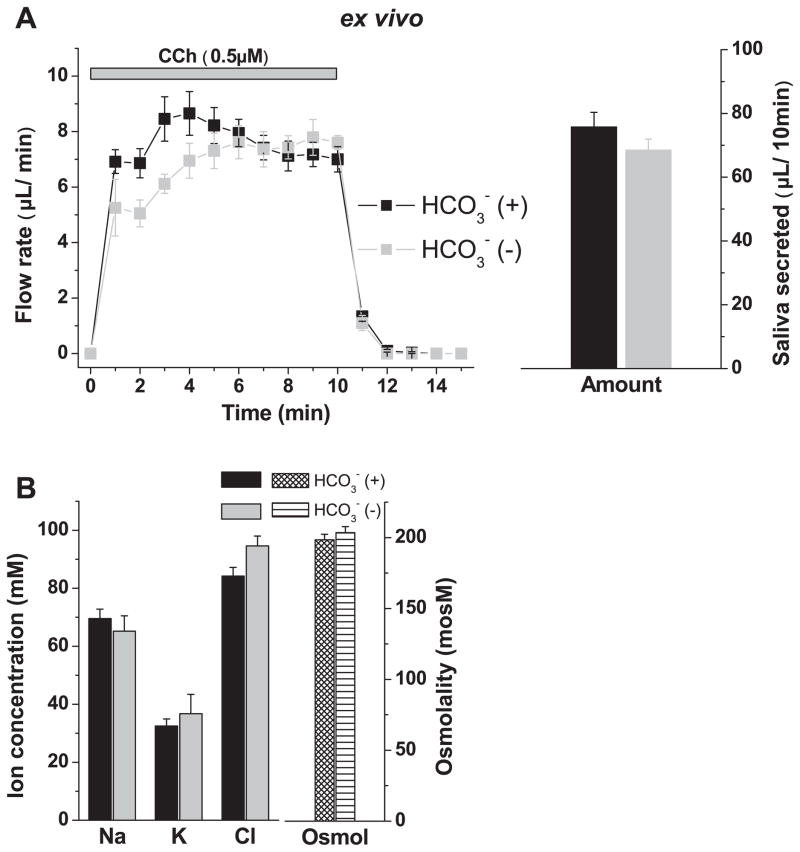

The secretion of K+ has been previously linked to secretion in salivary glands (for an overview, see Ref. 5). To investigate whether K+ efflux is dependent in the mouse submandibular, we used a recently developed ex vivo, perfused gland preparation (33). Vascular perfusion permits control of the agonist and/or inhibitor concentration and ion composition (e.g., [ ]), and eliminates circulatory factors and central neural inputs that often complicate the interpretation of in vivo experiments (33). depletion was achieved by removal of and addition of the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor acetazolamide in the perfusate. This maneuver did not significantly change the total volume of the fluid secreted during 10 min of stimulation with the muscarinic receptor agonist carbachol (Fig. 1A, right), although secretion was modestly reduced during the initial 3–4 min (Fig. 1A, left). Notably, Fig. 1B shows that depletion had no significant effect on the secretion of K+. Consequently, K+ efflux did not appear to be coupled to , nor did depletion have a significant effect on the [Na+], [Cl−] or osmolality of mouse submandibular saliva (Fig. 1B). The above experiments were performed at RT. Additional ex vivo experiments at 37°C with comparable flow rates found no significant difference in the ion composition (not shown, n ≥ 8).

Fig. 1.

Effects of depletion on fluid secretion and ion composition in ex vivo submandibular glands of wild-type KCa1.1 mice. Isolated, perfused submandibular glands (see MATERIALS AND METHODS) were used to determine the effects of depletion on the ion composition of saliva. Carbachol (CCh, 0.5 μM) was used to stimulate secretion. Flow rate was expressed as μl/min. -free solutions contained 100 μM of the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor acetazolamide. A: saliva flow rate (left) and total amount saliva secreted by 10-min stimulation (right). Glands were perfused with (black symbols, n = 10) and without (gray symbols, n = 4) external . B: ion composition and osmolality of the saliva shown in A. No significant difference in the ion concentration or osmolality was found between -containing and -free samples. Values represent means ± SE. KCa1.1, calcium-activated K channel isoform 1.1.

Inhibition of K+ secretion by paxilline and in KCa1.1-null mice

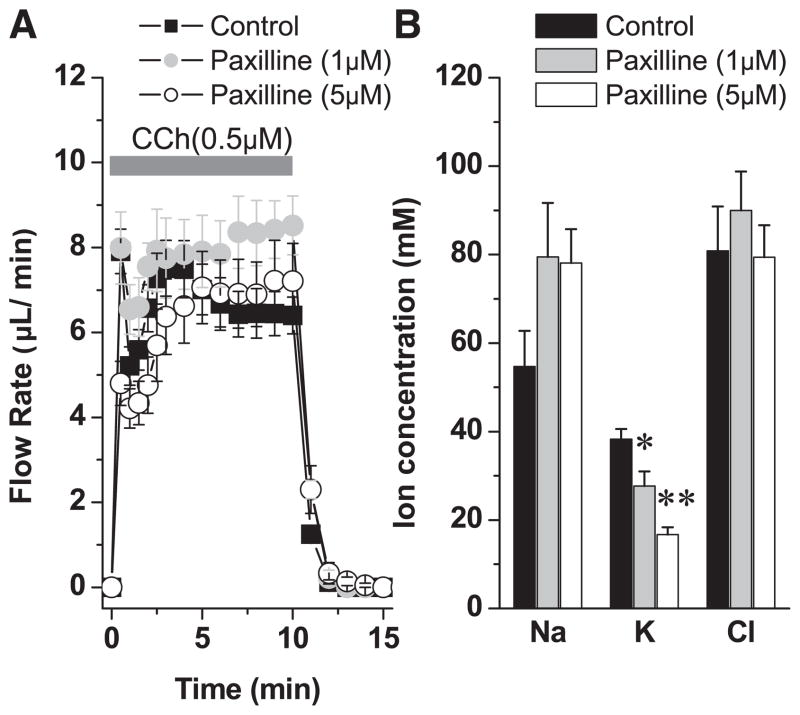

We hypothesized that because K+ efflux was not dependent on , K+ secretion may be regulated by a K channel. The properties of Ca2+-activated maxi-K (KCa1.1) and IKCa1 (KCa3.1) K channels have been characterized in salivary glands (2, 25, 32, 33). Moreover, it was previously shown in the parotid gland that K+ concentration is reduced from around 22 mM to 9.3 mM in mice lacking expression of the KCa1.1 K channel (32), suggesting that this channel may be involved in K+ secretion. However, this study did not directly address the mechanism involved, nor did it rule out the possibility that disruption of KCa1.1 may have altered the expression of another K+ secretion pathway. Here we take advantage of the ex vivo submandibular preparation and the more robust K+ secretion mechanism in the mouse submandibular gland to study the role of these K channels in K+ secretion in more detail. Paxilline, a specific maxi-K channel blocker, had no effect on the volume of fluid produced during carbachol stimulation (Fig. 2A). In contrast, paxilline produced a dose-dependent inhibition of K+ secretion (Fig. 2B; 27.6 ± 8.6% and 56.3 ± 4.3% at 1 μM and 5 μM paxilline, P < 0.05 and P < 0.0001, respectively; n ≥ 4). Na+ absorption also tended to be reduced in the presence of paxilline, but this difference did not reach statistical significance.

Fig. 2.

The effect of paxilline on ex vivo saliva flow rate and ion composition. A: ex vivo submandibular glands were perfused with paxilline (1 or 5 μM) for 30 min before stimulation with carbachol (0.5 μM) in the continued presence of paxilline. B: the ion composition was analyzed. The numbers of glands were control = 10, 1 μM paxilline = 4, and 5 μM paxilline = 6 from equal numbers of male and female wild-type mice; values represent means ± SE; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001. Wild-type mice used in this experiment were BlackSwiss-129 SvJ hybrid mice.

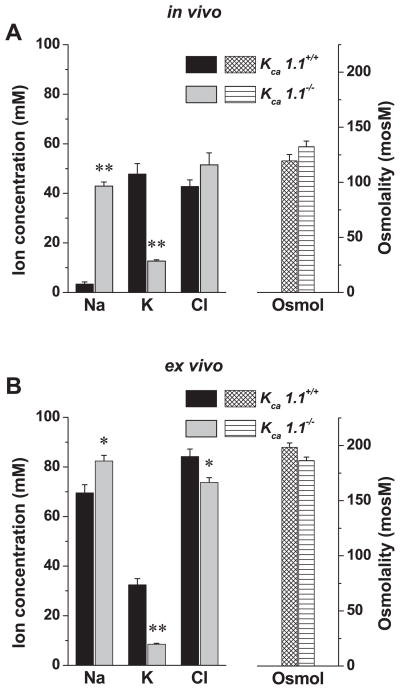

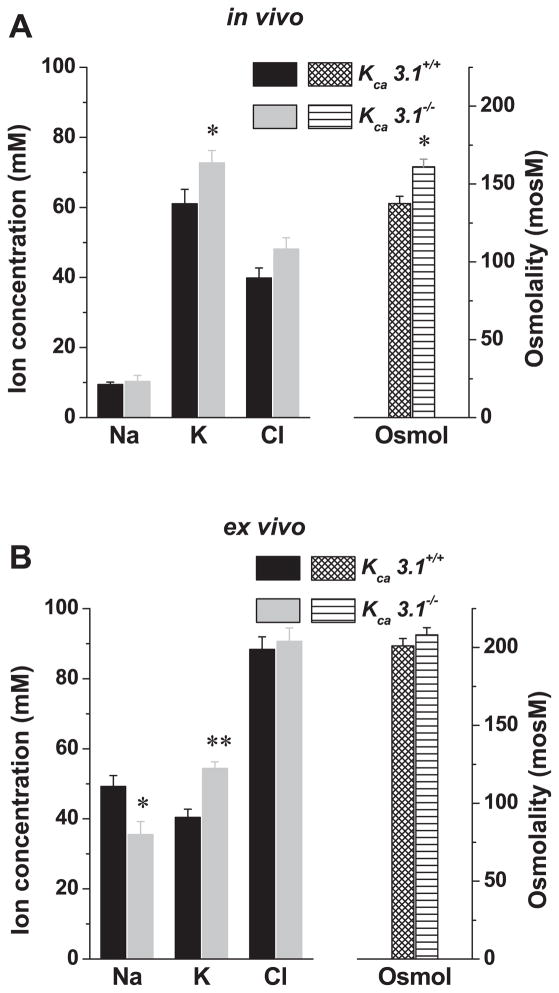

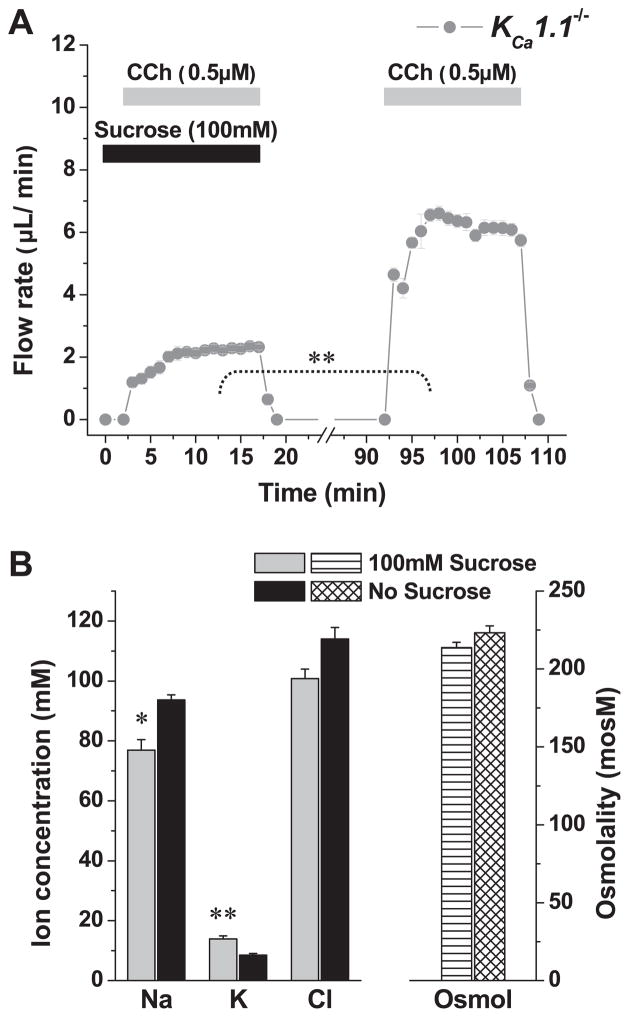

We next tested KCa1.1-deficient mice to rule out potential nonspecific side effects of paxilline on K+ secretion. Figure 3 shows that the submandibular glands of mice lacking KCa1.1 secreted ~75% less K+ and reabsorbed significantly less Na+ compared with their wild-type littermates, both in vivo (K+ decreased ~35 mM; Na+ increased ~40 mM) and ex vivo (K+ decreased ~24 mM; Na+ increased ~13 mM). In contrast, glands from KCa3.1-deficient mice secreted slightly more K+ in vivo and ex vivo (Fig. 4, A and B, respectively). Together, pharmacological and genetic inhibition of maxi-K channels demonstrates that the K+ output of the submandibular gland primarily involves KCa1.1 channels. It should be noted that under these experimental conditions, the ex vivo gland secretes considerably more saliva than the in vivo model system [75.8 ± 4.5 μl/10 min (n = 10) vs. 34.1 ± 4.1 μl/10 min (n = 14), respectively; P < 0.0001]. The more robust Na+ absorption and K+ secretion observed in vivo may be the result of this slower flow rate (see the following section).

Fig. 3.

In vivo and ex vivo ion composition of submandibular saliva secreted by KCa1.1+/+ and KCa1.1−/− mice. A: in vivo salivation was induced by the muscarinic agonist pilocarpine (10 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection), and the ion composition (left) and osmolality (right) of saliva collected over 30 min were analyzed (KCa1.1+/+, n = 12; KCa1.1−/−, n = 12). B: ex vivo salivation was induced by the muscarinic agonist carbachol (0.5 μM), and the ion composition (left) and osmolality (right) of saliva collected over 10 min were analyzed (KCa1.1+/+, n = 10; KCa1.1−/−, n = 5). Values represent means ± SE; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001.

Fig. 4.

In vivo and ex vivo ion composition of submandibular saliva secreted by KCa3.1+/+ and KCa3.1−/− mice. A: in vivo salivation was induced by the muscarinic agonist pilocarpine (10 mg/kg, intraperitoneal injection), and the ion composition (left) and osmolality (right) of saliva collected over 30 min were analyzed (KCa3.1+/+, n = 20; KCa3.1−/−, n = 22). B: ex vivo salivation was induced by the muscarinic agonist carbachol (0.5 μM), and the ion composition (left) and osmolality (right) of saliva collected over 10 min were analyzed (KCa3.1+/+, n = 20; KCa3.1−/−, n = 20). Values represent means ± SE; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001.

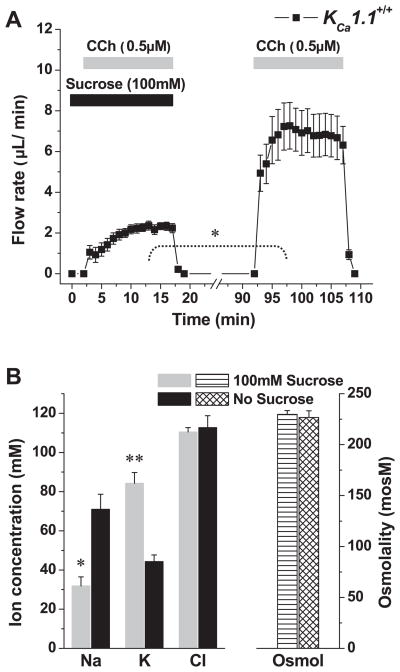

Relationship between K+ secretion, Na+ absorption, and flow rate

It is well known that the K+ and Na+ concentrations of saliva in some glands are flow rate dependent, such that as the flow rate decreases, the [K+] increases and the [Na+] decreases (5, 24). To investigate the relationship of [K+] and of [Na+] to flow rate in the mouse submandibular gland, we used the ex vivo, perfused gland preparation. The secretion rate, as previously described in rat submandibular glands (23), decreases when the osmolality of the perfusate is increased by the addition of sucrose. Figure 5A shows that, in the mouse submandibular, fluid secretion decreased 71.5 ± 3.8% when the perfusate was made ~30% hypertonic by the addition of 100 mM sucrose. This decreased flow was associated with nearly a twofold increase in the K+ concentration of the saliva (K+ increased ~40 mM). Conversely, there was nearly an identical decrease in the [Na+] (Na+ decreased ~39 mM) with no change in the Cl− concentration or osmolality of the saliva (Fig. 5B). These results confirm that the K+ concentration is inversely, whereas the Na+ concentration is directly, related to the salivary flow rate in the mouse submandibular gland.

Fig. 5.

Effects of hyperosmotic challenge on saliva flow and ion composition in the ex vivo submandibular glands of wild-type KCa1.1 mice. A: glands were stimulated with the muscarinic agonist carbachol (0.5 μM) in the presence or absence of 100 mM sucrose as indicated (n = 5). B: ion concentrations and osmolality of the saliva collected in the experiments shown in A. Values represent means ± SE; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001.

As shown in Figs. 2 and 3, saliva generated by glands exposed to paxilline or collected from KCa1.1-null mice contained significantly less K+ and more Na+. Therefore, we next determined whether the dramatic flow rate-dependent increase in K+ concentration (see Fig. 5) required expression of the KCa1.1 channel. Figure 6A shows that the perfusion of a hypertonic solution reduced the flow rate in KCa1.1-null mice to a similar magnitude as in wild-type mice (compare to Fig. 5A). Furthermore, Fig. 6B shows that, in KCa1.1 knockout animals, the flow rate-dependent secretion of K+ was nearly eliminated (90% decrease; K+ increased only ~4 mM vs. nearly 40 mM in KCa1.1+/+ mice). Moreover, the decrease in Na+ concentration was significantly reduced (Fig. 6B; Na+ decreased ~15 mM vs. ~39 mM in KCa1.1+/+ mice).

Fig. 6.

Effects of hyperosmotic challenge on saliva flow and ion composition in the ex vivo submandibular glands of wild-type KCa1.1−/− mice. A: glands were stimulated with the muscarinic agonist carbachol (0.5 μM) in the presence or absence of 100 mM sucrose as indicated (n = 6). B: ion concentrations and osmolality of the saliva collected in the experiments shown in A. Values represent means ± SE; *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001. Note that ~90% of the hypertonic-induced K+ secretion was inhibited in KCa1.1−/− mice (compare with Fig. 5).

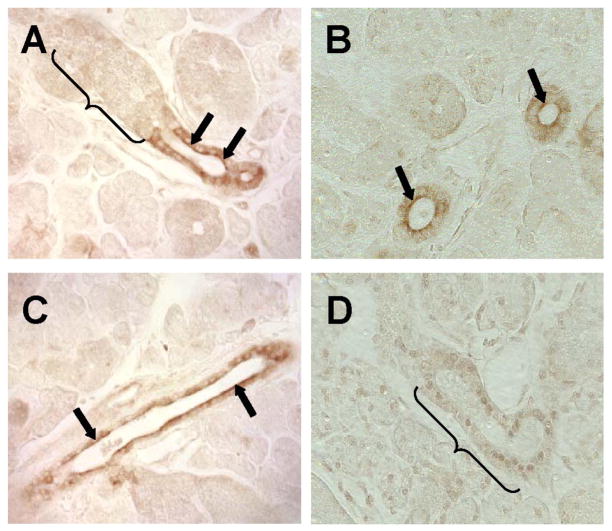

KCa1.1 channels are localized to the apical membrane of duct cells

The dramatic inhibition of K+ secretion by paxilline and as observed in mice lacking KCa1.1 suggested that the maxi-K channel may be the primary K+ efflux pathway in submandibular glands (see Figs. 2, 3, and 6). Such a mechanism requires that the KCa1.1 channel be localized to the apical membrane of acinar and/or duct cells. Alternatively, KCa1.1 channels located in the basolateral membrane could control the membrane potential, and thereby, indirectly regulate an apical K+ efflux pathway. Although several different K+ currents have been described in the duct cells of the mouse submandibular gland (9), none of these currents had maxi-K-like properties, in contrast with the K+ currents found in submandibular acinar cells (32). Therefore, to explore these different possibilities, immunohistochemistry was used to determine the distribution of KCa1.1 channels in the mouse submandibular gland. Figure 7A shows that KCa1.1 channels are highly expressed and primarily localized to the apical membrane of striated duct cells (arrows). In contrast, no KCa1.1 staining was present in granular ducts (bracket). Note that the granular duct identified by the bracket transitioned into a striated duct in this section. Figure 7B clearly shows apical staining of striated ducts (arrows), whereas, Fig. 7C shows that KCa1.1 channels are also highly expressed in the apical membrane of excretory ducts (arrows). No apparent staining was detected in the plasma membrane of striated ducts in sections prepared from the submandibular glands of KCa1.1-deficient mice (bracket, Fig. 7D), verifying the specificity of the antibody.

Fig. 7.

Localization of the KCa1.1 channel in mouse submandibular glands. Immunohistochemical staining of the KCa1.1 channel was observed in the apical region of striated (arrows in A and B) and excretory (arrows in C) ducts, but not in granular duct cells in wild-type KCa1.1 mice (bracket in A). D: no staining was detectable in the striated duct cells of KCa1.1−/− mice (bracket).

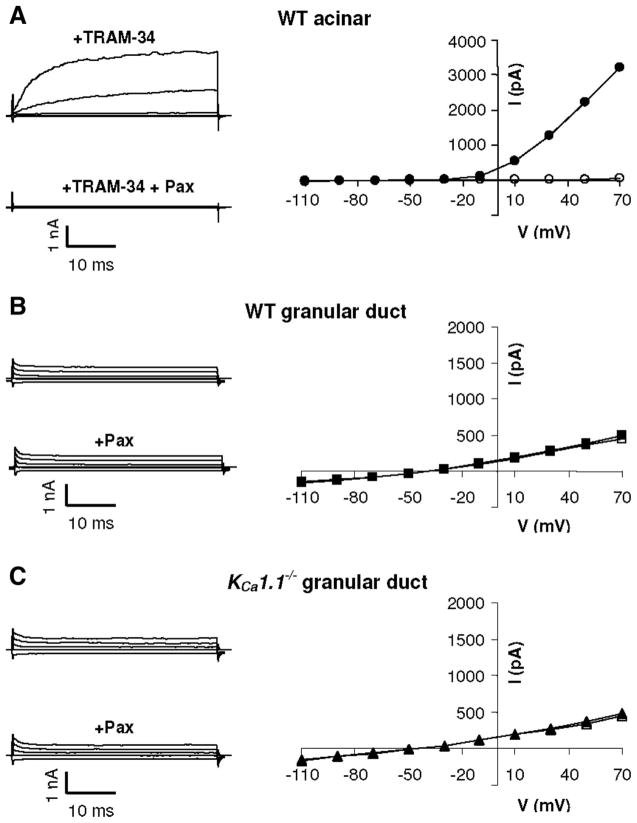

Maxi-K currents are not expressed in granular duct cells

Tissue sections shown in Fig. 7 revealed that KCa1.1 channels are present in the apical regions of both striated and excretory duct cells, but we failed to detect KCa1.1 channels in either acinar or granular duct cells. However, it has been previously shown that the acinar cells in the mouse submandibular gland possess maxi-K-like currents encoded by KCa1.1 (33). This indicates that immunohistochemistry was not sensitive enough to detect the expression of this channel in acinar cells, and it raises the possibility that granular duct cells may express KCa1.1 channels as well. Thus, to determine whether or not granular duct cells also express low levels of KCa1.1 channels, single cells were isolated from KCa1.1 wild-type and null mice and whole cell K+ currents examined. Cells were dialyzed with a fixed Ca2+ concentration of 250 nM to activate Ca2+-gated K channels as previously described (33), and the current sensitivity was determined for paxilline, a specific inhibitor of KCa1.1 channels. Figure 8A shows typical time- and voltage-dependent currents in acinar cells in the presence of 1 μM TRAM-34, a KCa3.1-specific inhibitor (solid circles). The currents were recorded by application of 20-mV steps from −110 to +70 mV from a holding potential of −60 mV. As expected, the maxi-K currents were almost completely inhibited by 1 μM paxilline (open circles). In eight experiments, >90% of the current was inhibited by paxilline (163 ± 21 and 14 ± 5 pA/pF at +70 mV before and after paxilline superfusion, respectively). These paxilline-sensitive K+ currents were identical to those from KCa1.1 channels previously described in salivary gland acinar cells (25, 32, 33).

Fig. 8.

Cationic current in mouse submandibular gland cells. Single acinar (A) or granular duct (B and C) cells were isolated from submandibular glands of either wild-type (WT; A and B) or KCa1.1-null (C) mice. Cationic currents were measured in the presence of 250 nM intracellular Ca2+ (solid symbols) and then treated with 1 μM of the maxi-K specific inhibitor paxilline (Pax; open symbols). The acinar cell currents in A were recorded in the presence of the KCa3.1-specific inhibitor TRAM-34 (1 μM). The solid and open symbols in B and C mostly overlie each other. V, voltage; I, current.

In contrast with the large K+ currents in acinar cells, there was an absence of time- and voltage-dependent maxi-K-like currents in the granular duct cells (Fig. 8B). Most of the cells (9 of 12 cells) presented relatively small time-independent currents, with little or no rectification (solid squares). Moreover, the currents were completely insensitive to paxilline (open squares). The reversal potential of the current was −46 ± 4 mV, indicating that there may be some contribution of a Na+ or nonselective cation conductance. Additionally, we found no further upregulation of the current by very high intracellular Ca2+ induced by superfusion of the granular duct cells with the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin (5 μM; n = 3; data not shown). A small fraction of the granular duct cells (3 out of 12 cells) had only very small, strongly inward-rectifying paxilline-insensitive current (>1 pA/pF at +70 mV and 2.7 ± 0.3 pA/pF at −110 mV) with a reversal potential of −77 ± 6 mV (data not shown).

To confirm that the rather small, paxilline-insensitive currents in granular duct cells were not associated with KCa1.1 channels, currents were also recorded in cells obtained from KCa1.1-null mice. As we have shown previously, parotid and submandibular acinar cells from these animals completely lack maxi-K currents, confirming the molecular identity of this channel in acinar cells (32, 33). Figure 8C shows that the typical currents in KCa1.1-null granular duct cells (solid triangles; 3 of 4 cells) had properties similar to the currents in wild-type cells (Fig. 8B). The currents in KCa1.1-null cells were also insensitive to paxilline (open triangles). The amplitude of the currents determined at +70 mV were similar in the wild-type and KCa1.1 null cells (27 ± 5 pA/pF, n = 9 vs. 21 ± 5 pA/pF, n = 3, respectively). In one of the four KCa1.1-null cells, we observed a small inward-rectifying current (data not shown). Consistent with the KCa1.1 immunolocalization results shown in Fig. 7, our electrophysiological data indicate the absence of maxi-K currents in the granular duct cells of mouse submandibular glands. Unfortunately, it is not possible to isolate and positively identify individual cells from striated or excretory ducts to confirm that KCa1.1 expression in the apical membranes of these cells directly correlates with the maxi-K activity that was inhibited by paxilline in the ex vivo preparation (see Fig. 2).

DISCUSSION

The molecular mechanism by which the mammalian exocrine salivary gland secretes K+ is not known. In the present study, we investigated the K+ secretion pathway in the mouse submandibular gland using a combination of an ex vivo, perfused gland preparation, immunohistochemistry, knockout mice, and the patch-clamp technique. The ex vivo K+ concentration of saliva was comparable to that seen in vivo. K+ secretion has been previously linked to secretion; however, we found in the present study that K+ secretion was insensitive to depletion. This result argues against the presence of cotransport (28), as well as the secretion of K+ and mediated through K+/H+ and Na+/H+ exchangers (12). Our results are consistent with those of previous studies that indicate little, if any, K+/H+ exchange in the ducts of rat (49, 51) or mouse (4) submandibular glands. Additionally, Zhao et al. (51) identified a pathway in rat submandibular gland ducts that mediates coupled K+ and fluxes with Na+ uptake, the so called Na+-coupled K+/H+ exchange mechanism. However, our results and those of Chaturapanich et al. (4) indicate that this latter transport mechanism appears not to be expressed in the ducts of mouse submandibular glands. In contrast with mouse and rat submandibular glands, rat parotid ducts express K+/H+ exchange, but it is not clear whether this activity reflected a K+/H+ exchange mechanism or separate K+ and H+ channels (28). If a K+/H+ exchange mechanism is active in mouse submandibular duct cells, depletion would be expected to cause the intracellular pH to acidify and thus limit K+ secretion. Consequently, the continued secretion of K+ under depleted conditions demonstrated that mouse submandibular duct cells express negligible cotransport, K+/H+ or Na+-coupled K+/H+ exchange.

It has also been speculated that apical K+ transport in submandibular ducts may be mediated by a conductive pathway (28, 51), although there had been no direct evidence for such a mechanism in the apical membrane of these cells. Three different cation currents have been described in the basolateral membrane of mouse submandibular duct cells, including one nonselective cation channel and two K channels (9). The molecular identities of these latter two inward-rectifying and voltage-insensitive K channels are unknown, but these may be responsible for the inward-rectifying K+ currents we detected using the patch-clamp technique in the whole cell configuration in 25% of the granular duct cells (4 out of 16). ROMK (renal outer medullary K channel or inward rectifier Kir 1.1)-like activity has also been reported in the human salivary gland cell line HSG (15), but we are unaware of evidence for similar currents in native cells. Moreover, the biophysical properties of the cation conductances previously reported in duct cells (9) resemble neither ROMK nor the K channels activated by Ca2+ in salivary gland acinar cells (2, 15, 25).

To further explore the role of K channels in the regulation of K+ secretion, the specific maxi-K inhibitor paxilline and mice with null mutations in either the maxi-K, Ca2+-activated K channel (KCa1.1−/−) or the IKCa1, Ca2+-activated K channel (KCa3.1−/−) genes were used. These manipulations had little if any effect on the saliva secretion volume (Fig. 2 and Ref. 33). In contrast, paxilline (Fig. 2) and disruption of KCa1.1 significantly inhibited K+ secretion, but not the KCa3.1 null mutation (Figs. 3 and 4, respectively). Together, these pharmacological and genetic studies show that the KCa1.1 channel is the major pathway involved in K+ efflux in the mouse submandibular gland. Furthermore, Fig. 6 illustrates that the hypertonic-induced enhanced secretion of K+ was nearly eliminated in KCa1.1-null mice. The total amount of K+ secreted (K+ concentration times the flow rate per gland) under isotonic conditions (higher flow rate) by the wild-type gland was 43.1 ± 6.1 μmol K+ during 15 min of stimulation, significantly more than under hypertonic conditions (lower flow rate; 23.1 ± 1.7 μmol K+). This result is consistent with the increased flow inducing an increase in K+ secretion via upregulation of maxi-K, as observed in the kidney (48). Although KCa1.1−/− mice secreted much less K+ than their wild-type littermates, it should be noted that glands from the KCa1.1−/− mice also secreted significantly more K+ during higher flow rate than during lower flow rate conditions (7.6 ± 0.5 vs. 4.2 ± 0.3 μmol of K+, respectively). Therefore, we cannot rule out other mechanisms being involved in the flow-induced increase in K+ secretion, nor the possibility that the hypertonic sucrose-containing solution affects K+ secretion independent of its effect to reduce flow.

The K+ conductances previously reported in salivary gland duct cells (9) do not resemble the currents generated by maxi-K channels in acinar cells (2, 15, 25), raising several important questions about the function of these channels in salivary glands. Does maxi-K mediate K+ secretion directly or does it indirectly regulate an apical K+ efflux pathway? Is maxi-K targeted to the apical or basolateral membrane, and in which cell type is it expressed, acinar or duct cells? Significantly, we found that the KCa1.1 channel is primarily localized to the apical membrane of striated and excretory duct cells, but not granular duct cells. Unfortunately, individual striated and excretory duct cells cannot be positively identified; thus, we do not know whether the KCa1.1 protein observed by immunohistochemistry translates into maxi-K currents in these cells. It is noteworthy that, although submandibular acinar cells express maxi-K currents (Fig. 8 and Ref. 33), we did not detect KCa1.1 staining. Because KCa1.1 channels are few in number (20) and are likely to be distributed throughout the entire basolateral membrane, we speculate that the antibody localization method was not sensitive enough to detect KCa1.1 expression in acinar cells. Our immunolocalization studies also failed to identify KCa1.1 staining in granular duct cells; this result was supported by the lack of Ca2+-activated K+ currents in this cell type.

In summary, we demonstrate that the KCa1.1 channel, and not a -dependent pathway, mediates K+ efflux in the mouse submandibular exocrine gland. The submandibular gland is a particularly good model system for investigating the K+ secretion mechanism in exocrine glands because of the high K+ concentrations achieved by this organ (>80 mM at low flow rates, see Fig. 5). Cook and colleagues (5, 6) hypothesized that fluid secretion can be driven by K channels in the apical membrane of acinar cells. In fact, there is direct evidence for an apical maxi-K-like current in the acinar cells of frog skin (41) and for apical Ca2+-activated K+ currents in rat lacrimal acinar cells (44). However, simultaneous imaging of the intracellular [Ca2+] while recording Ca2+-activated K+ currents [a comparable experimental paradigm to that used by Tan et al. (44)] suggested that Ca2+-activated K channels are localized to the basolateral membrane in mouse submandibular acinar cells (11). In agreement with this latter observation, micropuncture studies of mammalian salivary glands found that the K+ concentration of the primary fluid generated by acinar cells is similar to that in the venous outflow of stimulated glands, suggesting that acinar cells have little if any K+ conductance in their apical membrane. Both the primary saliva fluid and the venous outflow typically contain around 6 – 8 mM K+ (30, 50). Because the K+ and Na+ concentrations of both the acinar secretions and the venous plasma outflow from salivary gland (which reflects the interstitial ion concentration) are plasma-like, this suggests that K+ and Na+ likely enter the primary saliva across the “leaky” tight junctions of the acinus. Thus, most of the K+ found in the final saliva is secreted (whereas most of the Na+ is reabsorbed) as the saliva passes through the relatively water-impermeant ductal network (18).

Consistent with this K+ secretion model, we found that KCa1.1 channels were highly expressed and localized to the apical membranes of striated and excretory ducts, cells thought to be involved in K+ secretion. Notably, the K+ concentration of in vivo stimulated saliva (12.7 ± 0.5 mM K+) from mice lacking the KCa1.1 channel or in ex vivo saliva collected in the presence of 5 μM paxilline (16.8 ± 1.6 mM K+) was only modestly higher than the concentration in the primary secretions from acinar cells. Together, these results suggest that KCa1.1 channels in salivary gland duct cells are involved in K+ secretion. Further analysis will be necessary to determine whether the KCa1.1 channel is the K+ efflux pathway and/or whether it regulates K+ secretion indirectly by setting the membrane potential. However, based on the apical localization of KCa1.1 channels in duct cells and the activation properties of maxi-K channels, it appears that this channel is likely to be the major K+ efflux mechanism in the submandibular exocrine gland. It should be noted that there are multiple splice variants of the KCa1.1α-subunit and at least four regulatory β-subunits that associate with KCa1.1α. The activation kinetics of the KCa1.1 channel is dependent on which splice variant of the KCa1.1α pore-forming subunit is expressed (13, 14, 16, 35). What is more, regulatory β-subunits modulate the voltage- and Ca2+-dependent gating of the KCa1.1α-subunit (13, 14, 16, 35). Regardless of these additional regulatory properties of KCa1.1 channels, assuming an intracellular K+ concentration of ~145 mM, it is possible to concentrate the ductal K+ concentration to 80 mM or more if the membrane potential depolarizes. This suggests that the epithelial Na channel ENaC present in this cell type (8) may play an important role in depolarizing the membrane potential sufficiently to permit K+ secretion. In agreement with this hypothesis, much of the K+ secretion in the submandibular gland of the mouse appears to be linked to Na+ absorption.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jennifer Scantlin and Mark Wagner for excellent technical assistance in the ex vivo gland studies and Laurie Koek and Marcelo Catalán for performing the immunolocalization experiments and maintaining the mouse colonies.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants DE-016960 (to T. Begenisich) and DE-08921 and DE-09296 (to J. E. Melvin). A. Takahashi was a visiting scientist funded in part by The Society of Japanese Pharmacopoeia.

References

- 1.Alexander JH, van Lennep EW, Young JA. Water and electrolyte secretion by the exorbital lacrimal gland of the rat studied by micropuncture and catheterization techniques. Pflügers Arch. 1972;337:299–309. doi: 10.1007/BF00586647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Begenisich T, Nakamoto T, Ovitt CE, Nehrke K, Brugnara C, Alper SL, Melvin JE. Physiological roles of the intermediate conductance, Ca2+-activated potassium channel Kcnn4. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47681–47687. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409627200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botelho SY, Martinez EV. Electrolytes in lacrimal gland fluid and in tears at various flow rates in the rabbit. Am J Physiol. 1973;225:606–609. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.225.3.606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chaturapanich G, Ishibashi H, Dinudom A, Young JA, Cook DI. H+ transporters in the main excretory duct of the mouse mandibular salivary gland. J Physiol. 1997;503:583–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1997.583bg.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cook DI, Van Lennep EW, Roberts ML, Young JA. Secretion by the major salivary glands. In: Johnson LR, editor. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. 3. New York: Raven Press; 1994. pp. 1061–1117. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cook DI, Young JA. Effect of K+ channels in the apical plasma membrane on epithelial secretion based on secondary active Cl− transport. J Membr Biol. 1989;110:139–146. doi: 10.1007/BF01869469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cowman RA, Fitzgerald RJ. Potassium requirement of oral streptococci. J Dent Res. 1976;55:709. doi: 10.1177/00220345760550043601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dinudom A, Harvey KF, Komwatana P, Young JA, Kumar S, Cook DI. Nedd4 mediates control of an epithelial Na+ channel in salivary duct cells by cytosolic Na+ Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7169–7173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.7169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dinudom A, Young JA, Cook DI. Ion channels in the basolateral membrane of intralobular duct cells of mouse mandibular glands. Pflügers Arch. 1994;428:202–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00724498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Evans RL, Park K, Turner RJ, Watson GE, Nguyen HV, Dennett MR, Hand AR, Flagella M, Shull GE, Melvin JE. Severe impairment of salivation in Na+/K+/2Cl− cotransporter (NKCC1)-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26720–26726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003753200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harmer AR, Smith PM, Gallacher DV. Local and global calcium signals and fluid and electrolyte secretion in mouse submandibular acinar cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G118–G124. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00096.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knauf H, Lubcke R, Kreutz W, Sachs G. Interrelationships of ion transport in rat submaxillary duct epithelium. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol. 1982;242:F132–F139. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1982.242.2.F132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Knaus HG, Eberhart A, Glossmann H, Munujos P, Kaczorowski GJ, Garcia ML. Pharmacology and structure of high conductance calcium-activated potassium channels. Cell Signal. 1994;6:861–870. doi: 10.1016/0898-6568(94)90019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ledoux J, Werner ME, Brayden JE, Nelson MT. Calcium-activated potassium channels and the regulation of vascular tone. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006;21:69–78. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00040.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Singh BB, Ambudkar IS. ATP-dependent activation of KCa and ROMK-type KATP channels in human submandibular gland ductal cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25121–25129. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.35.25121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu R, Alioua A, Kumar Y, Eghbali M, Stefani E, Toro L. MaxiK channel partners: physiological impact. J Physiol. 2006;570:65–72. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.098913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luoma H, Tuompo H. The relationship between sugar metabolism and potassium translocation by caries-inducing streptococci and the inhibitory role of fluoride. Arch Oral Biol. 1975;20:749–755. doi: 10.1016/0003-9969(75)90047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mangos JA, McSherry NR, Nousia-Arvanitakis S, Irwin K. Secretion and transductal fluxes of ions in exocrine glands of the mouse. Am J Physiol. 1973;225:18–24. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.225.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinez JR, Holzgreve H, Frick A. Micropuncture study of submaxillary glands of adult rats. Pflügers Arch Gesamte Physiol Menschen Tiere. 1966;290:124–133. doi: 10.1007/BF00363690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maruyama Y, Nishiyama A, Izumi T, Hoshimiya N, Petersen OH. Ensemble noise and current relaxation analysis of K+ current in single isolated salivary acinar cells from rat. Pflügers Arch. 1986;406:69–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00582956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melvin JE, Yule D, Shuttleworth T, Begenisich T. Regulation of fluid and electrolyte secretion in salivary gland acinar cells. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:445–469. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.041703.084745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meredith AL, Thorneloe KS, Werner ME, Nelson MT, Aldrich RW. Overactive bladder and incontinence in the absence of the BK large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:36746–36752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405621200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakahari T, Steward MC, Yoshida H, Imai Y. Osmotic flow transients during acetylcholine stimulation in the perfused rat submandibular gland. Exp Physiol. 1997;82:55–70. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1997.sp004015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nauntofte B. Regulation of electrolyte and fluid secretion in salivary acinar cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 1992;263:G823–G837. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.6.G823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nehrke K, Quinn CC, Begenisich T. Molecular identification of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in parotid acinar cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C535–C546. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00044.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nelson AB, Krispel CM, Sekirnjak C, du Lac S. Long-lasting increases in intrinsic excitability triggered by inhibition. Neuron. 2003;40:609–620. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00641-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pattillo JM, Yazejian B, DiGregorio DA, Vergara JL, Grinnell AD, Meriney SD. Contribution of presynaptic calcium-activated potassium currents to transmitter release regulation in cultured Xenopus nerve-muscle synapses. Neuroscience. 2001;102:229–240. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00453-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paulais M, Cragoe EJ, Jr, Turner RJ. Ion transport mechanisms in rat parotid intralobular striated ducts. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1994;266:C1594–C1602. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.6.C1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pluznick JL, Sansom SC. BK channels in the kidney: role in K+ secretion and localization of molecular components. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;291:F517–F529. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00118.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poulsen JH, Bledsoe SW. Salivary gland K+ transport: in vivo studies with K+-specific microelectrodes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 1978;234:E79–E83. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.234.1.E79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pyott SJ, Meredith AL, Fodor AA, Vazquez AE, Yamoah EN, Aldrich RW. Cochlear function in mice lacking the BK channel alpha, beta1, or beta4 subunits. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:3312–3324. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608726200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Romanenko V, Nakamoto T, Srivastava A, Melvin JE, Begenisich T. Molecular identification and physiological roles of parotid acinar cell maxi-K channels. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27964–27972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Romanenko VG, Nakamoto T, Srivastava A, Begenisich T, Melvin JE. Regulation of membrane potential and fluid secretion by Ca2+-activated K channels in mouse submandibular glands. J Physiol. 2007;581:801–817. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.127498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruttiger L, Sausbier M, Zimmermann U, Winter H, Braig C, Engel J, Knirsch M, Arntz C, Langer P, Hirt B, Muller M, Kopschall I, Pfister M, Munkner S, Rohbock K, Pfaff I, Rusch A, Ruth P, Knipper M. Deletion of the Ca2+-activated potassium (BK) alpha-subunit but not the BKbeta1-subunit leads to progressive hearing loss. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:12922–12927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402660101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salkoff L, Butler A, Ferreira G, Santi C, Wei A. High-conductance potassium channels of the SLO family. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:921–931. doi: 10.1038/nrn1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sato F, Sato K. Secretion of a potassium-rich fluid by the secretory coil of the rat paw eccrine sweat gland. J Physiol. 1978;274:37–50. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sausbier M, Arntz C, Bucurenciu I, Zhao H, Zhou XB, Sausbier U, Feil S, Kamm S, Essin K, Sailer CA, Abdullah U, Krippeit-Drews P, Feil R, Hofmann F, Knaus HG, Kenyon C, Shipston MJ, Storm JF, Neuhuber W, Korth M, Schubert R, Gollasch M, Ruth P. Elevated blood pressure linked to primary hyperaldosteronism and impaired vasodilation in BK channel-deficient mice. Circulation. 2005;112:60–68. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000156448.74296.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sausbier M, Matos JE, Sausbier U, Beranek G, Arntz C, Neuhuber W, Ruth P, Leipziger J. Distal colonic K+ secretion occurs via BK channels. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:1275–1282. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005101111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sausbier U, Sausbier M, Sailer CA, Arntz C, Knaus HG, Neuhuber W, Ruth P. Ca2+-activated K+ channels of the BK-type in the mouse brain. Histochem Cell Biol. 2006;125:725–741. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0124-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ship JA, Hu K. Radiotherapy-induced salivary dysfunction. Semin Oncol. 2004;31:29–36. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sorensen JB, Nielsen MS, Gudme CN, Larsen EH, Nielsen R. Maxi K+ channels co-localised with CFTR in the apical membrane of an exocrine gland acinus: possible involvement in secretion. Pflügers Arch. 2001;442:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s004240000493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stoner LC, Morley GE. Effect of basolateral or apical hyposmolarity on apical maxi K channels of everted rat collecting tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol. 1995;268:F569–F580. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1995.268.4.F569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tabak LA. In defense of the oral cavity: the protective role of the salivary secretions. Pediatr Dent. 2006;28:110–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tan YP, Marty A, Trautmann A. High density of Ca2+-dependent K+ and Cl− channels on the luminal membrane of lacrimal acinar cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11229–11233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Viejo-Diaz M, Andres MT, Fierro JF. Modulation of in vitro fungicidal activity of human lactoferrin against Candida albicans by extracellular cation concentration and target cell metabolic activity. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1242–1248. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1242-1248.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang YB, Germaine GR. Effects of pH, potassium, magnesium, and bacterial growth phase on lysozyme inhibition of glucose fermentation by Streptococcus mutans 10449. J Dent Res. 1993;72:907–911. doi: 10.1177/00220345930720051201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Willcox MD, Irwin AM, Jacques NA, Knox KW. Enumeration of oral streptococci on media containing different concentrations of sodium and potassium ions. J Dent Res. 1991;70:1375–1379. doi: 10.1177/00220345910700101201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woda CB, Bragin A, Kleyman TR, Satlin LM. Flow-dependent K+ secretion in the cortical collecting duct is mediated by a maxi-K channel. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2001;280:F786–F793. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.5.F786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu X, Zhao H, Diaz J, Muallem S. Regulation of [Na+]i in resting and stimulated submandibular salivary ducts. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19606–19612. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Young JA, Schogel E. Micropuncture investigation of sodium and potassium excretion in rat submaxillary saliva. Pflügers Arch Gesamte Physiol Menschen Tiere. 1966;291:85–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00362654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao H, Xu X, Diaz J, Muallem S. Na+, K+, and transport in submandibular salivary ducts. Membrane localization of transporters. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19599–19605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]