Abstract

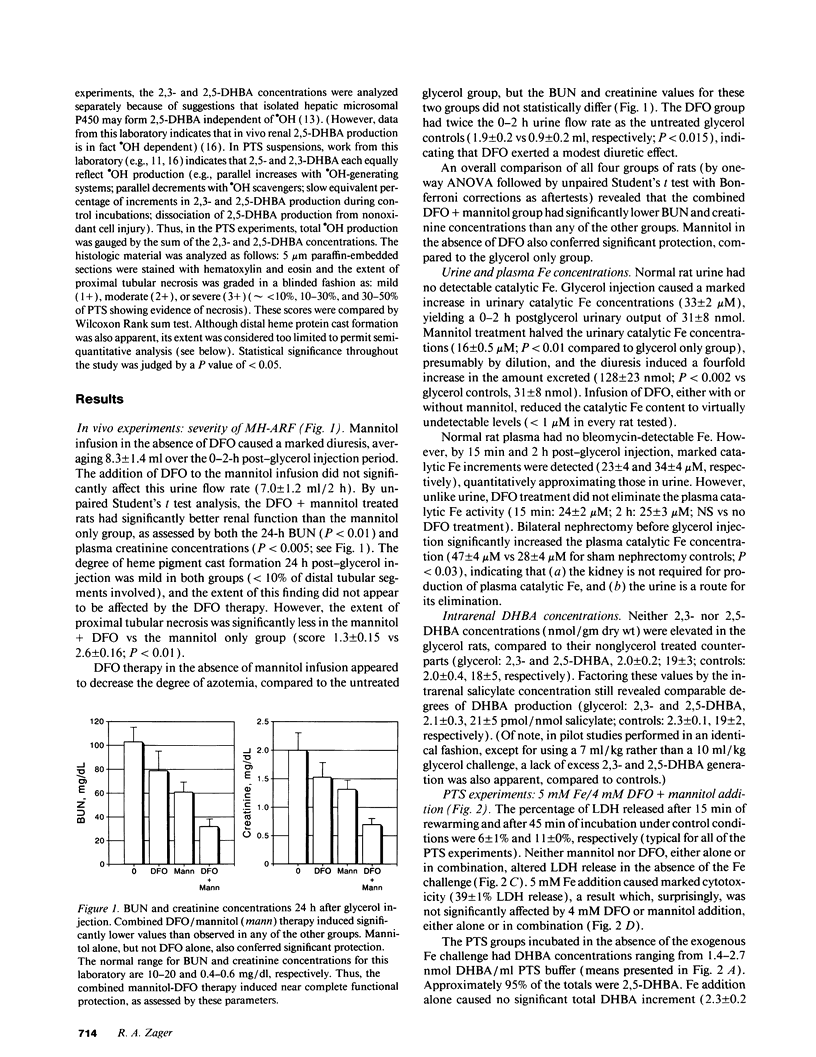

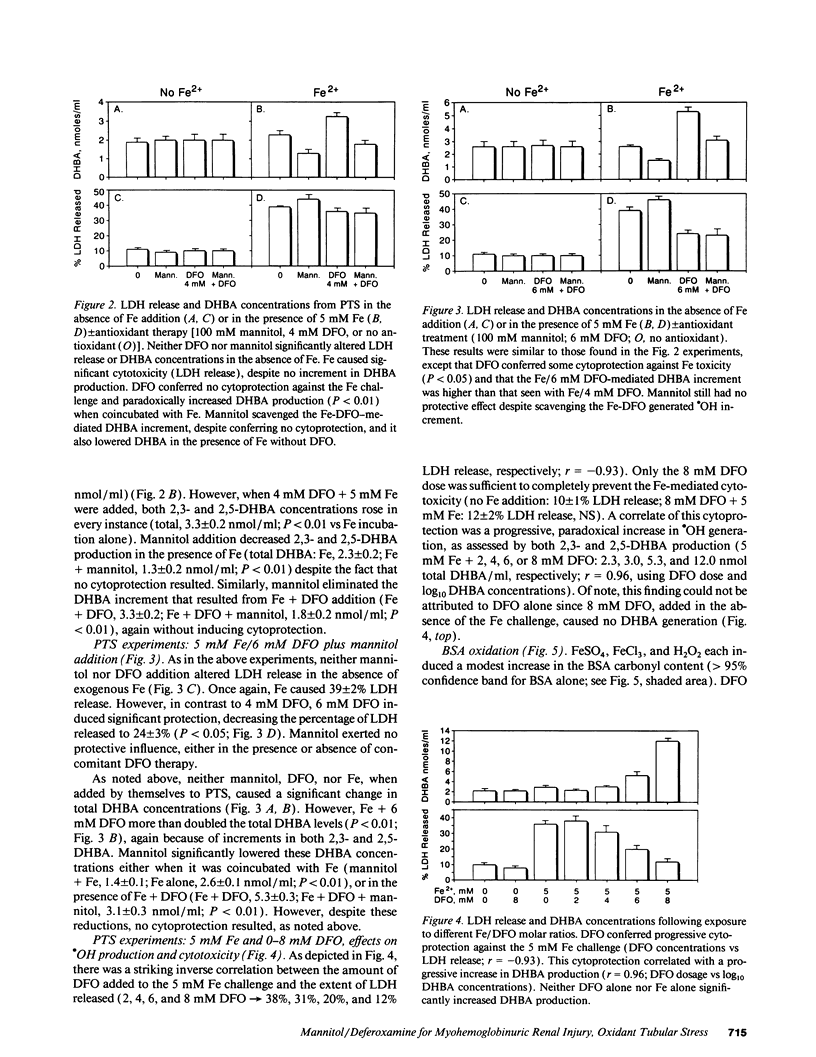

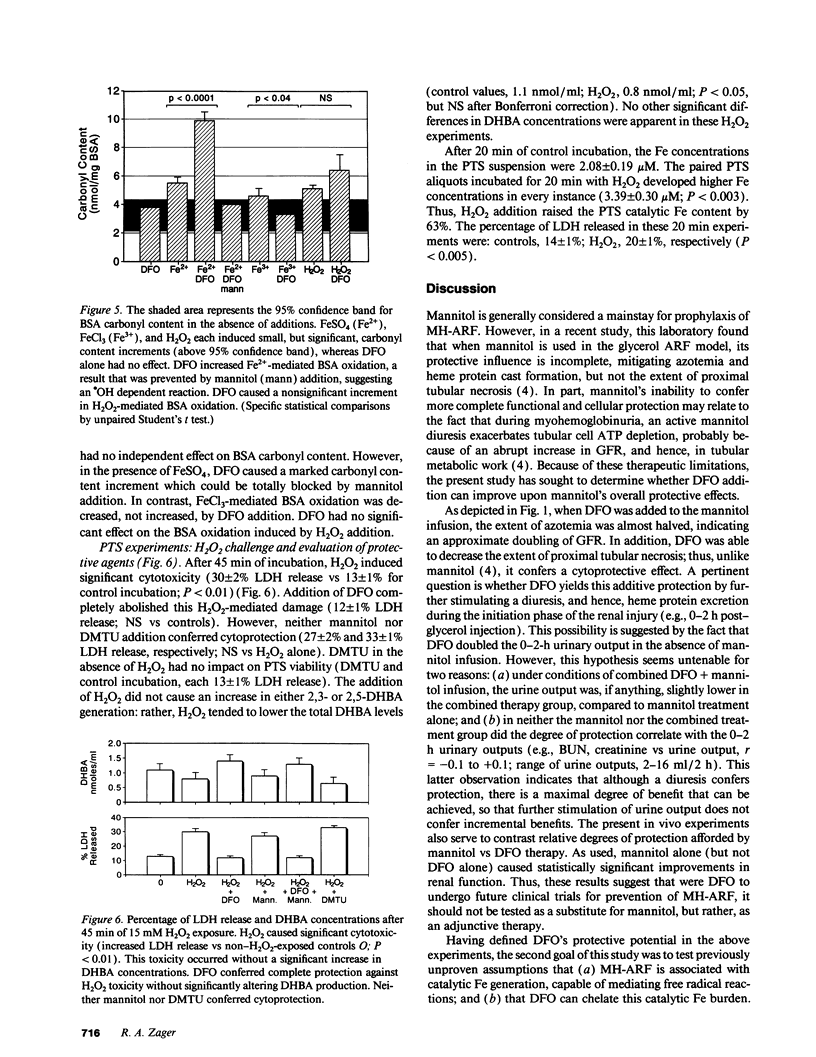

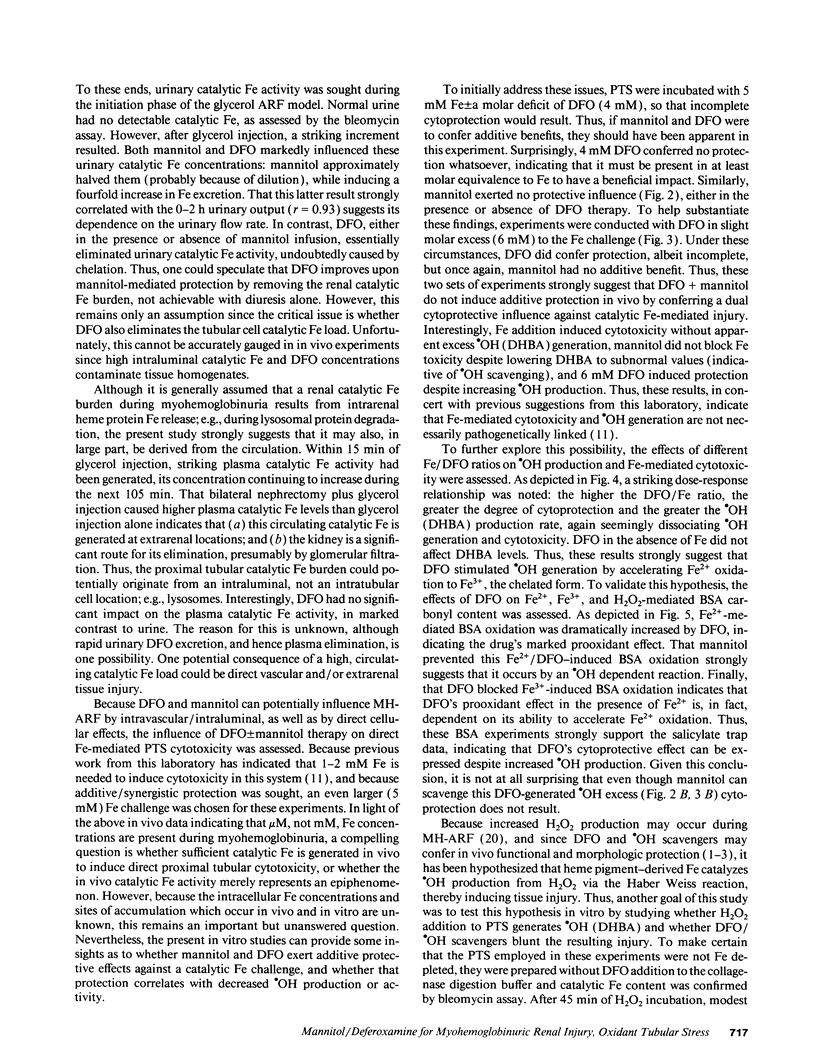

Mannitol (M) and deferoxamine (DFO) can each protect against myohemoglobinuric acute renal failure (MH-ARF). This study assessed M-DFO interactions during MH-ARF to help discern mechanisms of renal injury, and to define whether M + DFO exerts additive or synergistic antioxidant/cytoprotective effects. Rats subjected to the glycerol model of MH-ARF were treated with (a) M; (b) DFO; (c) M + DFO; or (d) no protective agents. Relative degrees of protection (24-h plasma urea/creatinine concentrations) were M + DFO greater than M greater than DFO greater than or equal to no therapy. To assess whether catalytic Fe is generated during MH-ARF, the bleomycin assay was applied to plasma/urine samples obtained 0-2 h post-glycerol injection. Although striking plasma and urinary increments were noted, excess renal hydroxyl radical (.OH) production was not apparent (gauged by the salicylate trap method). M increased catalytic Fe excretion (four times), whereas DFO eliminated its urinary (but not plasma) activity. To determine direct M/DFO effects on proximal tubular cell oxidant injury, isolated rat proximal tubular segments (PTS) were incubated with toxic dosages of FeSO4 or H2O2. Despite inducing cell injury (lactic dehydrogenase release), Fe caused no .OH production. DFO conferred dose-dependent cytoprotection, correlating with increased, not decreased, .OH generation. Although M scavenged this .OH excess, it had no additive or independent, protective effect. H2O2 cytotoxicity correlated with increased catalytic Fe (but not .OH) generation. The fact that DFO (but not .OH scavengers [M and dimethylthiourea]) blocked H2O2 toxicity implied Fe-dependent, .OH-independent cell killing. In conclusion, (a) striking catalytic Fe generation occurs during MH-ARF, but augmented intrarenal .OH production may not develop; (b) DFO can block Fe toxicity despite a prooxidant effect; (c) H2O2 PTS toxicity is Fe, but possibly not .OH, dependent; and (d) M does not mitigate oxidant PTS injury, either in the presence or absence of DFO, suggesting that its additive benefit with DFO in vivo occurs via a diuretic, not antioxidant effect.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andreoli S. P., McAteer J. A. Reactive oxygen molecule-mediated injury in endothelial and renal tubular epithelial cells in vitro. Kidney Int. 1990 Nov;38(5):785–794. doi: 10.1038/ki.1990.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Better O. S., Stein J. H. Early management of shock and prophylaxis of acute renal failure in traumatic rhabdomyolysis. N Engl J Med. 1990 Mar 22;322(12):825–829. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199003223221207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao W., Carney J. M., Duchon A., Floyd R. A., Chevion M. Oxygen free radical involvement in ischemia and reperfusion injury to brain. Neurosci Lett. 1988 May 26;88(2):233–238. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90132-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eneas J. F., Schoenfeld P. Y., Humphreys M. H. The effect of infusion of mannitol-sodium bicarbonate on the clinical course of myoglobinuria. Arch Intern Med. 1979 Jul;139(7):801–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floyd R. A., Watson J. J., Wong P. K. Sensitive assay of hydroxyl free radical formation utilizing high pressure liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection of phenol and salicylate hydroxylation products. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 1984 Dec;10(3-4):221–235. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(84)90042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grootveld M., Halliwell B. Aromatic hydroxylation as a potential measure of hydroxyl-radical formation in vivo. Identification of hydroxylated derivatives of salicylate in human body fluids. Biochem J. 1986 Jul 15;237(2):499–504. doi: 10.1042/bj2370499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidet B., Shah S. V. Enhanced in vivo H2O2 generation by rat kidney in glycerol-induced renal failure. Am J Physiol. 1989 Sep;257(3 Pt 2):F440–F445. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.257.3.F440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge J. M., Hou Y. Y. Iron complexes and their reactivity in the bleomycin assay for radical-promoting loosely-bound iron. Free Radic Res Commun. 1986;2(3):143–151. doi: 10.3109/10715768609088066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutteridge J. M. Iron promoters of the Fenton reaction and lipid peroxidation can be released from haemoglobin by peroxides. FEBS Lett. 1986 Jun 9;201(2):291–295. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)80626-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell B., Gutteridge J. M. Role of free radicals and catalytic metal ions in human disease: an overview. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:1–85. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86093-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingelman-Sundberg M., Kaur H., Terelius Y., Persson J. O., Halliwell B. Hydroxylation of salicylate by microsomal fractions and cytochrome P-450. Lack of production of 2,3-dihydroxybenzoate unless hydroxyl radical formation is permitted. Biochem J. 1991 Jun 15;276(Pt 3):753–757. doi: 10.1042/bj2760753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff S. J., Waltersdorph A. M., Michel B. R., Rosen H. Oxygen-based free radical generation by ferrous ions and deferoxamine. J Biol Chem. 1989 Nov 25;264(33):19765–19771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine R. L., Garland D., Oliver C. N., Amici A., Climent I., Lenz A. G., Ahn B. W., Shaltiel S., Stadtman E. R. Determination of carbonyl content in oxidatively modified proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1990;186:464–478. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)86141-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsos S. E., Kim D., Lucchesi B. R., Fantone J. C. Modulation of myoglobin-H2O2-mediated peroxidation reactions by sulfhydryl compounds. Lab Invest. 1988 Dec;59(6):824–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARRY W. L., SCHAEFER J. A., MUELLER C. B. Experimental studies of acute renal failure. I. The protective effect of mannitol. J Urol. 1963 Jan;89:1–6. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)64488-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paller M. S. Hemoglobin- and myoglobin-induced acute renal failure in rats: role of iron in nephrotoxicity. Am J Physiol. 1988 Sep;255(3 Pt 2):F539–F544. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.255.3.F539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D., Taitelman U., Michaelson M., Bar-Joseph G., Bursztein S., Better O. S. Prevention of acute renal failure in traumatic rhabdomyolysis. Arch Intern Med. 1984 Feb;144(2):277–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush J. D., Koppenol W. H. Oxidizing intermediates in the reaction of ferrous EDTA with hydrogen peroxide. Reactions with organic molecules and ferrocytochrome c. J Biol Chem. 1986 May 25;261(15):6730–6733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah S. V., Walker P. D. Evidence suggesting a role for hydroxyl radical in glycerol-induced acute renal failure. Am J Physiol. 1988 Sep;255(3 Pt 2):F438–F443. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1988.255.3.F438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtman E. R. Metal ion-catalyzed oxidation of proteins: biochemical mechanism and biological consequences. Free Radic Biol Med. 1990;9(4):315–325. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(90)90006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starke P. E., Farber J. L. Ferric iron and superoxide ions are required for the killing of cultured hepatocytes by hydrogen peroxide. Evidence for the participation of hydroxyl radicals formed by an iron-catalyzed Haber-Weiss reaction. J Biol Chem. 1985 Aug 25;260(18):10099–10104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svingen B. A., O'Neal F. O., Aust S. D. The role of superoxide and singlet oxygen in lipid peroxidation. Photochem Photobiol. 1978 Oct-Nov;28(4-5):803–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1978.tb07022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker P. D., Shah S. V. Hydrogen peroxide cytotoxicity in LLC-PK1 cells: a role for iron. Kidney Int. 1991 Nov;40(5):891–898. doi: 10.1038/ki.1991.290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson D. R., Thiel G., Arce M. L., Oken D. E. Glycerol induced hemoglobinuric acute renal failure in the rat. 3. Micropuncture study of the effects of mannitol and isotonic saline on individual nephron function. Nephron. 1967;4(6):337–355. doi: 10.1159/000179594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zager R. A., Foerder C. A. Effects of inorganic iron and myoglobin on in vitro proximal tubular lipid peroxidation and cytotoxicity. J Clin Invest. 1992 Mar;89(3):989–995. doi: 10.1172/JCI115682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zager R. A., Foerder C., Bredl C. The influence of mannitol on myoglobinuric acute renal failure: functional, biochemical, and morphological assessments. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1991 Oct;2(4):848–855. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V24848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zager R. A., Gamelin L. M. Pathogenetic mechanisms in experimental hemoglobinuric acute renal failure. Am J Physiol. 1989 Mar;256(3 Pt 2):F446–F455. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1989.256.3.F446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zager R. A., Gmur D. J., Bredl C. R., Eng M. J. Temperature effects on ischemic and hypoxic renal proximal tubular injury. Lab Invest. 1991 Jun;64(6):766–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zager R. A., Gmur D. J., Schimpf B. A., Bredl C. R., Foerder C. A. Evidence against increased hydroxyl radical production during oxygen deprivation-reoxygenation proximal tubular injury. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1992 May;2(11):1627–1633. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V2111627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zager R. A. Studies of mechanisms and protective maneuvers in myoglobinuric acute renal injury. Lab Invest. 1989 May;60(5):619–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]