Abstract

Platelet-derived growth factors (PDGF) bind to two closely related receptor tyrosine kinases, PDGF receptor α and β, which are encoded by the PDGFRA and PDGFRB genes. Aberrant activation of PDGF receptors occurs in myeloid malignancies associated with hypereosinophilia, due to chromosomal alterations that produce fusion genes, such as ETV6-PDGFRB or FIP1L1-PDGFRA. Most patients are males and respond to low dose imatinib, which is particularly effective against PDGF receptor kinase activity. Recently, activating point mutations in PDGFRA were also described in hypereosinophilia. In addition, autocrine loops have been identified in large granular lymphocyte leukemia and HTLV-transformed lymphocytes, suggesting new possible indications for tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy. Although PDGF was initially purified from platelets more than 30 years ago, its physiological role in the hematopoietic system remains unclear. Hematopoietic defects in PDGF-deficient mice have been reported but appear to be secondary to cardiovascular and placental abnormalities. Nevertheless, PDGF acts directly on several hematopoietic cell types in vitro, such as megakaryocytes, platelets, activated macrophages and, possibly, certain lymphocyte subsets and eosinophils. The relevance of these observations for normal human hematopoiesis remains to be established.

Keywords: Receptor tyrosine kinase, hypereosinophilia, signal transduction, imatinib, myeloproliferative disorders, myeloid neoplasms, chronic eosinophilic leukemia, hypereosinophilic syndrome

Introduction

Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) was purified from platelet extracts and characterized as a mitogen for fibroblasts and cells of mesenchymal origin in the late seventies. In humans, several dimeric isoforms are produced from four different genes, namely PDGF-A, -B and, more recently, -C and -D. Like fibroblast growth factors, PDGF was shown to stimulate wound healing, leading the first therapeutic application, becaplermin (Regranex ®), a gel containing recombinant PDGF-B, which accelerates ulcer repair. However, knock-out mice studies revealed that the most essential functions of the different PDGF isoforms are associated with the embryo development. Indeed, disruption of any single PDGF ligand or receptor gene is lethal, except PDGFD, whose importance for mouse development has not been reported yet. Mice deficient in PDGF receptors suffer from severe defects in lungs, kidneys, vessels, placenta, brain and skeleton (for a review, see [1]).

The PDGF receptors belong to the receptor-tyrosine kinase family, more precisely to the type III group, which also includes c-KIT, FLT3 and the macrophage-colony-stimulating factor receptor [2]. Two highly homologous receptor genes have been cloned: PDGFRA and PDGFRB, which encode the PDGF receptors α and β, respectively. PDGFRα binds to all ligands but PDGF-D, while PDGFRβ binds to PDGF-B and -D only. The first genetic alteration of these receptors was reported in hematopoietic malignancies in 1994 by Todd Golub and Gary Gilliland in patients with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia, as a result of a t (5;12) translocation, leading to the fusion of TEL (now renamed ETV6) with PDGFRB [3]. Many other mutations have been described, mostly in myeloproliferative disorders and solid tumors, such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors and gliomas (for a review, see [4]). The discovery that imatinib, a molecule approved for the treatment of BCR-ABL-positive chronic myelogenous leukemia, also blocks PDGF receptors at an even lower concentration was a major breakthrough. Indeed, patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms harboring a PDGF receptor fusion respond well to low dose imatinib, even though rare resistant mutations have been described [5,6]. While the role of PDGF receptors in myeloid neoplasms is well established, their physiological roles in hematopoiesis are still unclear.

PDGF receptor structure and signaling

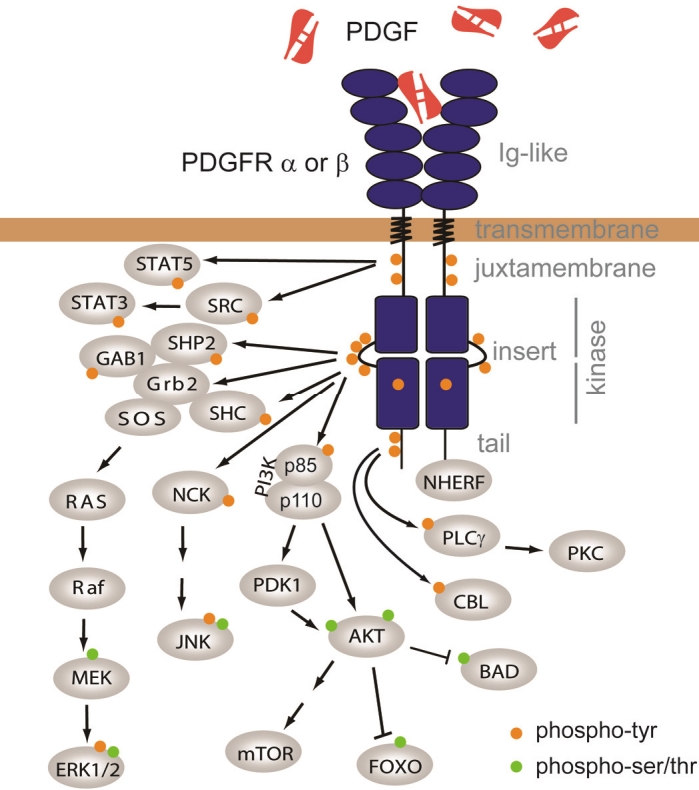

The two PDGF receptors share a common domain organization consisting of five extracellular immunoglobulin-like domains, a single-spanning transmembrane domain and an intracellular split kinase domain, which is divided in two lobes connected by a flexible polypeptide linker, the kinase insert (Figure 1). In the absence of ligand, three regions keep the kinase domain in an inactive conformation: the intracellular juxtamembrane domain, the activation loop of the kinase domain and the C-terminal tail [7,8]. The activation loop in particular bars the way to the active site.

Figure 1.

PDGF receptors and signaling. PDGFR domains are named in gray on the right. Arrows depict protein interaction and/or phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of tyrosines is represented by a orange disk, while phosphorylated serines and threonines are represented in green. See text for details.

As PDGF is a dimeric ligand, it forms a complex with two PDGF receptor molecules. More precisely, PDGF interacts with the first three Ig-like domains. PDGF binding thus induces receptor dimerization, which is facilitated by the fourth Ig-like domain. Recent data suggest that the receptor also undergoes conformational changes upon ligand binding [9]. This process brings two kinase domains close to each other and stabilizes the active conformation, leading to the transphosphorylation of critical regulatory tyrosine residues in the activation loop of the catalytic core and in the juxtamembrane domain [7,10]. The fully active phosphorylated kinase domains then phosphorylate multiple tyrosine residues of the receptor cytoplasmic part, which act as docking sites for Src homology 2 (SH2) domains of a variety of signal transduction proteins, including signal transducers and activators of transcription (STAT), phospholipase Cγ (PLCγ), phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), SRC family kinases and the SHP2 phosphatase (Figure 1). Adaptor molecules containing SH2 domains, such as Grb2, Shc, Crk and Nck, are also recruited to the receptor complex and control the activation of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinases (Figure 1) [11-14]. These pathways lead to the regulation of a number of transcription factors that regulate cell growth and survival, such as c-MYC, AP1, FOXO or SREBP [15-18].

PDGF receptors also interact with the PDZ domain of NHERF (also named EBP50), an adaptor protein that recruits PTEN to the receptor complex [19,20]. PTEN counteracts the effects of PI3K by dephosphorylating phosphoinositides.

PDGF receptors are quickly degraded after activation by a mechanism that involves ligand-induced endocytosis and degradation in lysosomes. This process requires the ubiquitination of the receptor by c-CBL, an E3 ubiquitin ligase [21,22]. CBL may be recruited either directly or via an adaptor protein to the PDGFRβ complex [22-24]. Interestingly, mutations that disrupt the catalytic activity of CBL were found in various malignancies including myeloid neoplasms.

PDGF function in platelets and hematopoiesis

As mentioned above, PDGF receptors are crucial for the proper development of several organs in the embryo, including kidneys, lungs and the cardiovascular system [1,25]. The role of PDGF ligands and their receptors in hematopoiesis is much less clear. PDGF receptors are expressed in bone marrow but not in blood leukocytes. Knock-out mice for PDGF-B or PDGFRβ show anemia and thrombocytopenia, but these seem to be secondary to other organ defects, because normal hematopoiesis in wild-type irradiated mice can be reconstituted by grafting PDGF-Bor PDGFRβ-deficient hematopoietic cells [26]. This does not exclude a role for other PDGF ligands or PDGFRα. However, data from patients treated for a long period of time with tyrosine kinase inhibitors that block PDGFR activity, such as imatinib, also argue against an essential role of these receptors in normal adult hematopoiesis. Nevertheless, a number of reports suggest that PDGF receptors may modulate hematopoietic cell functions and that PDGF ligands produced by hematopoietic cells contribute to several physiological and pathological processes outside the hematopoietic compartment.

PDGF is produced by a variety of cell types including endothelial cells, fibroblasts, vascular smooth muscle cells, osteoblasts, glia and neurons [27]. In the hematopoietic system, PDGF (mostly heterodimeric PDGF-AB) is synthesized by megakaryocytes and stored in the alpha granules of platelets [27], from which it is released after cell activation. The release of PDGF by these cells and the activity of this growth factor on connective tissue cells suggested an implication in wound healing. Exogenous PDGF-B was shown to stimulate wound repair and a gel containing recombinant PDGF-B has been commercialized for the treatment of diabetic ulcers (Regranex®). PDGF also contributes to angiogenesis by stimulating the recruitment of pericytes to new vessels [28,29]. However, PDGF-B is not essential for the formation of granulation tissue during the wound healing process in mice [30]. In humans, the long term administration of imatinib has no reported impact on healing. PDGF is likely to stimulate wound repair in a redundant manner with other growth factors.

Megakaryocytes, megakaryocyte cell lines and platelets not only make PDGF ligands but also express PDGF receptors [27,31,32]. Secretion of PDGF by platelets, which express PDGFRα, triggers a negative feedback loop, which decreases platelet aggregation in an autocrine manner [33]. In addition, PDGF was shown to enhance the expansion of megakaryocyte progenitors from human CD34+ cells, which could help restoring platelet levels after aggregation [34]. In this respect, administration of PDGF-B enhances platelet recovery after irradiation-induced thrombocythemia in mice [32]. Proliferation of other CD34+ progenitors was also modestly induced by the addition of PDGF [35-37]. A transient PDGFRβ expression was reported in these cells by PCR [35]. However, we have failed confirm any mRNA or protein expression of PDGF receptors in CD34+ progenitor cell cultures (Montano-Almendras et al, unpublished observations). It was suggested that PDGF may act in an indirect manner through adherent mesenchymal cells or macrophages contaminating the culture [37,38]. Accordingly, it was demonstrated that the stimulation of erythropoiesis by PDGF in vitro requires the presence of stromal cells [39]. Alternatively, PDGF stimulates marrow macrophages to release interleukin- 1, which could explain some reported effects of PDGF on hematopoietic progenitors [37].

PDGF in myelofibrosis

The role of PDGF in fibrosis of several organs, such as lung, kidneys and liver is well established [1], raising the interesting possibility that PDGF may also be involved in myelofibrosis. Indeed, PDGF-B expression is increased in the bone marrow of patients with myelofibrosis [31]. PDGFRα mRNA expression was also found increased in the same samples, particularly in megakaryocytes [31]. These cells may be the source of PDGF and other growth factors that could drive fibrosis in bone marrow. However, clinical trials with imatinib in myelofibrosis did not generate convincing results and researchers are focusing on other therapeutic targets [40,41].

PDGF function in macrophages and immune cells

Macrophages can also produce PDGF [27,42]. This process has been particularly studied in the context of atherosclerosis, in which secreted PDGF-A and -B stimulate migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells in vessel walls. Accordingly, PDGF receptor inhibition delays the atherosclerosis in Apo-E deficient mice [43]. Like wound healing, it is likely that atherosclerosis involves several growth factors which act in a partially redundant manner. Macrophages may also constitute an important source of PDGF in tumor stroma, leading to a paracrine stimulation of tumor cells, stromal fibroblasts and pericytes [44]. Macrophages not only produce PDGF ligands but also express PDGFRβ and proliferate in response to PDGF-BB stimulation [45]. PDGF receptors are not expressed on peripheral blood monocytes but PDGFRβ is induced upon differentiation into macrophages in vitro.

In addition to macrophages and platelets, PDGF -BB can be secreted by HTLV-transfromed lymphocytes (see below) and by regulatory T lymphocytes (or “Tregs”), contributing to silica-induced lung fibrosis [46].

A few reports suggest that PDGF may affect lymphocyte functions. PDGF was reported to inhibit the in vitro lytic activity of human NK cells, which express PDGF receptors [47]. By contrast, PDGF does not interfere with cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity. An effect of PDGF on mouse T lymphocyte function has also been reported [48], but PDGF receptor expression was not confirmed on these cells. The relevance of these observations is not clear.

Finally PDGFRβ expression was found in 4 out of 8 patients with mild to moderate eosinophilia, while PDGFRα expression was less frequent [49]. Whether PDGF plays a role in eosinophil physiology has not been determined. This issue is of particular interest since mutated PDGF receptors are responsible for a fraction of clonal hypereosinophilia cases (see below).

PDGF in leukemia

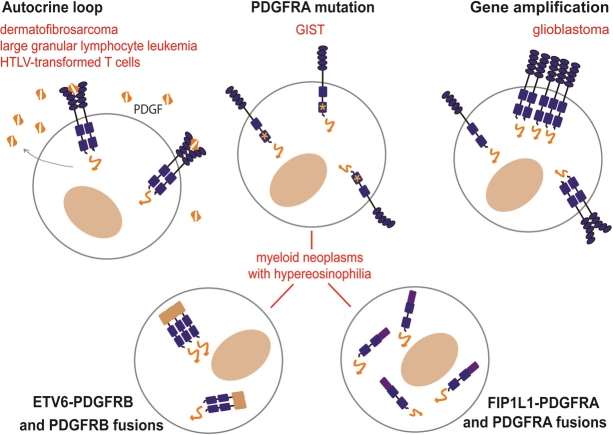

The concomitant expression of PDGF ligands and receptors in the same cell can contribute to cancer progression by creating an autocrine loop (Figure 2). This was first demonstrated by showing that the sequence of the v-SIS simian sarcoma virus oncogene is almost identical to PDGF-B [50]. In dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, a translocation that places the PDGF-B-encoding sequence in front of the collagen gene promoter leads to massive PDGF-B production and constitutive growth stimulation via the endogenous PDGFRβ receptor [51]. This skin tumor is now treated by imatinib as a complement to surgery.

Figure 2.

Activation of PDGF receptors in hematological malignancies and cancer.

HTLV-transformed T cells express PDGFRβ and produce significant amounts of PDGF, which can also be found in the plasma of HTLV-infected individuals [52-54]. This was ascribed to the transactivation of the PDGF-B gene by the HTLV protein Tax [55]. However, this autocrine loop may be redundant with many other growth factors secreted by HTLV-infected cells. In one cell line, integration of the HTLV-1 provirus within the PDGFRB gene generated a fusion transcript encoding a PDGFRβ variant, which lacks the extracellular and transmembrane domains and is able to transform fibroblasts [56].

A similar autocrine loop may be responsible for large granular lymphocyte leukemia, in which aberrant expression of PDGF-B and PDGFRβ was described recently [53]. Patients with this relatively indolent leukemia have high circulating levels of PDGF-B. In this case, the genetic alterations leading to over-expression has not been identified. Constitutive PDGF receptor signaling in large granular lymphocyte leukemia cells, which are derived from T or NK lymphocytes, promotes cell survival by activating the PI3K-AKT pathway [53].

PDGF receptor fusion in myeloid neoplasms

Various rare chromosomal rearrangements of PDGFRA and PDGFRB have been associated with myeloproliferative neoplasms, chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), atypical chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) and chronic eosinophilic leukemia (CEL) [2,57]. These patients share a number of key features: most of them are males, show hypereosinophilia, which can provoke severe tissue damage, and often evolve towards acute leukemia. Long-term remission can be induced by low dose imatinib therapy [5,58,59]. Resistance to the drug is infrequent but has been reported as a result of mutations, such as the T674I in FIP1L1-PDGFRA [6,58,60]. Patients with eosinophilia in the absence of PDGF receptor alteration do not usually respond to imatinib therapy [61]. Patients with PDGFR rearrangements are now grouped in a single clinical entity of the WHO classification: myeloid neoplasms associated with eosinophilia and PDGFRA or PDGFRB rearrangement [61]. In addition, a few atypical patients have been described, including one case of thrombocythemia associated with a KANK1-PDGFRB fusion [62].

The cause of PDGFR locus alteration has not been studied specifically, but non-homologous DNA end repair after chromosome injury is likely to contribute to the process. In addition, genes frequently involved in fusions tend to cluster within chromosome fragile sites [63,64]. These relatively large regions scattered in the human genome include PDGFRA and FIP1L1 [64]. Breakpoints in PDGFRB, like in most other fusion genes, usually occur in very large introns, suggesting that the exact DNA breakpoints are randomly distributed within the fragile sites [65]. By contrast, PDGFRA breakpoints are always located in exon 12, which encodes the juxtamembrane domain, the disruption of which activates the fusion protein.

In the fusion oncogene, the partner gene always replaces the 5’ end of PDGFRA or PDGFRB. As a consequence, the expression of the oncogenic fusion product is controlled by the gene promoter of the partner gene. Thus PDGFR fusion proteins can be over-expressed in cells that do not normally express wild-type PDGF receptors. This is an important consequence of the gene fusion process, in addition to creating a constitutively activated oncogene. As a result, high PDGFRA and PDGFRA expression in blood cells can be monitored as a clue of gene rearrangement [66].

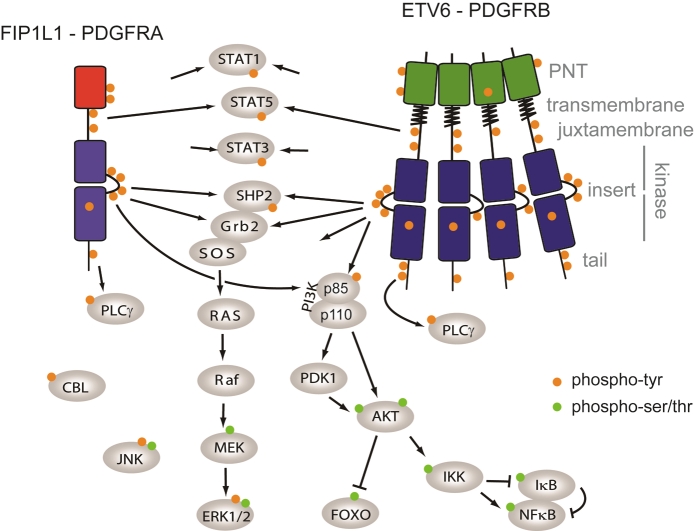

The tyrosine kinase activity of the fusion product can be switched on by two different mechanisms (Figure 2 and 3). The first involves the oligomerization of the hybrid protein and is usually found in PDGFRB fusions. The other relies on the deletion of the juxtamembrane inhibitory domain, and is found in all PDGFRA fusions as well as in a minor subset of PDGFRB translocation products.

Figure 3.

Structure of PDGF receptor fusions and signaling. PDGFR domains are indicated in gray on the right. Arrows depict protein interaction and/or phosphorylation. Phosphorylation of tyrosines is represented by orange disks, while phosphorylated serines and threonines are represented in green. See text for details.

PDGFR fusion products that have been studied are located in the cytosol. This may explain that although they are constitutively activated, they escape the normal ubiquitination and degradation route to the lysosome, enhancing their transformation potential [67].

PDGFRB translocation products

The archetype PDGFRB translocation product is ETV6-PDGFRB (also named TEL-PDGFRβ, Figure 3) [3,67-70]. This hybrid oncogene consists of the in-frame fusion of the N-terminal part of the transcription repressor ETV6 (formerly named TEL), including its pointed domain, with the kinase domain of PDGFRβ [69]. The pointed domain is required for constitutive activation of the kinase domain and induces the oligomerization of the protein, which is thought to mimic the ligand-induced activation of wild-type receptors. In addition, PDGFRβ hybrids retain the transmembrane domain, which is required for cell transformation, even though ETV6-PDGFRB is not a membrane but a cytosolic protein [70]. Removal of the transmembrane segment affects the conformation of the protein. The PDGFRB extracellular immunoglobulin-like domains are lost in the fusion and replaced by the fusion partner gene, but in rare cases, the fifth Ig domain is retained in the fusion product. However, it can be deleted without affecting transformation efficiency [62].

Expression of this oncogene in hematopoietic cells, such as Ba/F3 cells, stimulates growth in the absence of cytokine [69]. In these cells, several signaling pathways contribute to proliferation, including PI3K, STAT5 and NF-κB [71-73]. Interestingly, the acute expression of ETV6- PDGFRB can also induce apoptosis of Ba/F3 cells in the presence of interleukin-3. JNK activation may be responsible for this paradoxical effect [74,75].

When it is introduced in mouse bone marrow cells, ETV6-PDGFRB induces a fatal myeloproliferative disorder. Noticeably, eosinophilia is not observed in this model, by contrast to the human disease [76]. The development of a myeloproliferative neoplasm depends on the presence of multiple tyrosine phosphorylation sites in the PDGFRB part of the fusion [76], and is delayed in mice deficient in STAT5 [68]. In vitro, ETV6-PDGFRB does not favor the differentiation of mouse hematopoietic stem cells into eosinophils [77]. By contrast, we observed that CD34+ human progenitor cells transduced with ETV6- PDGFRB proliferate in the absence of cytokine and differentiated towards the eosinophil lineage, as illustrated by the cell characteristic morphology, expression of the IL-5 receptor and eosinophil peroxidase, in a process that is NF- κB-dependent (Montano-Almendras et al, submitted). NF-κB activation can be blocked by a PI3K inhibitor, suggesting that the PI3K-AKT pathway may be involved, as previously described downstream wild-type PDGF receptors. ETV6-PDGFRB also activates STAT1, STAT3 and STAT5 in these cells. STAT1 activation by ETV6- PDGFRB was also reported in other cell types, but its role remains elusive [78]. In vivo, ETV6- PDGFRB induces leukemia with a shorter latency from bone marrow cells deficient in STAT1, suggesting a tumor suppressor role for STAT1 [68].

More than twenty different PDGFRB fusion products have been described [2,57]. Unlike ETV6- PDGFRB, none of them harbor a PNT domain. The most frequent oligomerization domains in PDGFRB fusion are coiled coils, which are found in 18 out of 23 fusion products [57]. Although coiled coil-induced oligomerization is well documented in general, their role in PDGFR fusion has not been extensively studied, except in two cases. In KANK1-PDGFRB, trimerization is mediated either by coiled coils of another unique domain in a redundant manner [79]. The coiled-coils of HIP-PDGFRB are dispensable for homodimerization, which required another sequence that shares homology with talin [80].

Ligand binding to the PDGF receptors not only induces dimerization, but also a conformational change, particularly of the fourth Ig-like domain [9]. These changes could help disrupting the juxtamembrane inhibitory domain and orienting the kinase domains properly [81]. In line with these observations, we showed that dimerization of ETV6-PDGFRB and KANK1-PDGFRB is not enough to induce cell transformation. Indeed, sequences located between the oligomerization domain of the partner and the PDGFRB kinase domain are critical to determine the optimal conformation of both fusion proteins [79,81].

Several other signaling molecules are activated by PDGFRB fusions. For instance, HIP1-PDGFRB binds to the SH2-containing Inositol 5- Phosphatase-1 (SHIP1), which antagonizes PI3K. It was speculated that the interaction of HIP1-PDGFRB with SHIP1 might sequester the latter from its substrates, enhancing phosphatidylinositol- dependent signaling [82].

FIP1L1-PDGFRA and other PDGFRA fusions

The fusion of FIP1L1 with PDGFRA results from a cryptic internal deletion of 800 kb on chromosome 4 [58]. It is found in about 10% of patients with idiopathic hypereosinophilia [58,83]. A few cases of systemic mastocytosis and acute myeloid leukemia with eosinophilia were also desccribed [84,85]. Beside eosinophils, the fusion is present in most bone marrow precursors of granulocytes, monocytes and erythrocytes, but not in lymphocytes, megakaryocytes and multipotent CD34+ cells, although the authors could not exclude an expression of the fusion in a small subset of these cells due to the limited sensitivity of the technique used in the study [86]. This observation suggests that FIP1L1-PDGFRA gives a proliferative advantage to granulocyte/monocyte progenitors, as well as erythroid progenitors (to a lesser extent), but not to multipotent, lymphoid or megakaryocytic progenitors.

All identified PDGFRA breakpoints are located within exon 12, which encodes the juxtamembrane domain. The disruption of this inhibitory domain is sufficient to activate the PDGFRα kinase domain [87,88]. The domain is truncated in all known PDGFRA fusions and in a subset of PDGFRB fusions. FIP1L1 does not harbor any consensus oligomerization domain and is not required for Ba/F3 cell transformation [88]. However, it may play a role in human progenitor cell proliferation [89]. It was shown that two tyrosine residues of the FIP1L1 part are phosphorylated in FIP1L1-PDGFRA and may act as binding sites for signaling proteins [90].

The tight association of FIP1L1-PDGFRA with hypereosinophilia is not understood. The fusion induces a myeloproliferative neoplasm in mice but no eosinophilia, except in IL-5 transgenic mice, in which enforced FIP1L1-PDGFRA expression enhances IL-5 driven hypereosinophilia. The role of IL-5 is further illustrated by the observation that an IL-5 gene polymorphism is associated with the severity of the human disease [91]. In vitro, expression of FIP1L1- PDGFRA in mouse or human progenitors favors eosinophil differentiation [77,89]. Signaling studies revealed that STAT5 is essential for the proliferation of human CD34+ cells expressing FIP1L1-PDGFRA [89]. Other signaling mediators activated by this oncoprotein include STAT1, STAT3, PI3K and MAP kinases (Figure 3) [17,89].

Experimental evidence as well as the patient response to imatinib clearly show that the FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion is the cause of this particular myeloproliferative neoplasm. No additional gene alteration has been identified so far in these patients. Nevertheless, the deletion of one allele of the genes located between FIP1L1 and PDGFRA may contribute to the disease. This has however not been studied.

PDGF receptor point mutations in hematopoietic malignancies

Activating mutations of PDGFRA have been found in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors [92]. Mutations were also reported in three cases of acute lymphoblastic and myeloid leukemia [93-95]. However, the two AML mutations do not seem to constitutively activate the receptor (our unpublished data). Recently, Elling and colleagues found activating PDGFRA mutations and receptor overexpression in a small subset of patients with hypereosinophilia (Figure 3). Whether these patients can benefit from imatinib therapy is not yet known. Interestingly, several passenger mutations and polymorphisms were also identified in the course of this study. This emphasizes the need for careful molecular characterization of potential PDGF receptor cancer mutations.

Conclusions

Myeloid neoplasms associated with PDGF receptor fusion and hypereosinophilia is now a well established clinical entity and patients can be successfully treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Recent results suggest that imatinib therapy could also be tested hypereosinophilia with PDGFRA point mutations and to large granular lymphocyte leukemia. The mechanisms whereby PDGF receptor-derived oncogenes transform hematopoietic cells have also been studied in details. Nevertheless, the reasons why PDGF alterations favor eosinophil development are still elusive. Although PDGF does not seem to play an essential role in normal hematopoiesis, which makes it an ideal target for therapy, a number of reports suggest that it may regulate megakaryocytes, platelets, macrophages, lymphocytes and eosinophils. Despite decades of research, the relevance of these observations for hematopoiesis and immunity remains largely unclear.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Salus Sanguinis foundation and Action de Recherches Concertées (Communauté Francaise de Belgique).

References

- 1.Andrae J, Gallini R, Betsholtz C. Role of platelet-derived growth factors in physiology and medicine. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1276–1312. doi: 10.1101/gad.1653708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toffalini F, Demoulin JB. New insights into the mechanisms of hematopoietic cell transformation by activated receptor tyrosine kinases. Blood. 2010;116:2429–2437. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-279752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golub TR, Barker GF, Lovett M, Gilliland DG. Fusion of PDGF receptor beta to a novel ets-like gene, tel, in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia with t (5;12) chromosomal translocation. Cell. 1994;77:307–316. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90322-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostman A, Heldin CH. PDGF receptors as targets in tumor treatment. Adv Cancer Res. 2007;97:247–274. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)97011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.David M, Cross NC, Burgstaller S, Chase A, Curtis C, Dang R, Gardembas M, Goldman JM, Grand F, Hughes G, Huguet F, Lavender L, McArthur GA, Mahon FX, Massimini G, Melo J, Rousselot P, Russell-Jones RJ, Seymour JF, Smith G, Stark A, Waghorn K, Nikolova Z, Apperley JF. Durable responses to imatinib in patients with PDGFRB fusion gene-positive and BCR-ABL-negative chronic myeloproliferative disorders. Blood. 2007;109:61–64. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-024828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lierman E, Michaux L, Beullens E, Pierre P, Marynen P, Cools J, Vandenberghe P. FIP1L1-PDGFRalpha D842V, a novel panresistant mutant, emerging after treatment of FIP1L1-PDGFRα T674I eosinophilic leukemia with single agent sorafenib. Leukemia. 2009;23:845–851. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Griffith J, Black J, Faerman C, Swenson L, Wynn M, Lu F, Lippke J, Saxena K. The structural basis for autoinhibition of FLT3 by the juxtamembrane domain. Mol Cell. 2004;13:169–178. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00505-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chiara F, Bishayee S, Heldin CH, Demoulin JB. Autoinhibition of the platelet-derived growth factor beta-receptor tyrosine kinase by its C-terminal tail. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:19732–19738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang Y, Yuzawa S, Schlessinger J. Contacts between membrane proximal regions of the PDGF receptor ectodomain are required for receptor activation but not for receptor dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7681–7686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802896105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuzawa S, Opatowsky Y, Zhang Z, Mandiyan V, Lax I, Schlessinger J. Structural basis for activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase KIT by stem cell factor. Cell. 2007;130:323–334. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heldin CH, Ostman A, Ronnstrand L. Signal transduction via platelet-derived growth factor receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1378:F79–113. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(98)00015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lennartsson J, Ronnstrand L. The stem cell factor receptor/c-Kit as a drug target in cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2006;6:65–75. doi: 10.2174/156800906775471725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parcells BW, Ikeda AK, Simms-Waldrip T, Moore TB, Sakamoto KM. FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 in normal hematopoiesis and acute myeloid leukemia. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1174–1184. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masson K, Ronnstrand L. Oncogenic signaling from the hematopoietic growth factor receptors c-Kit and Flt3. Cell Signal. 2009;21:1717–1726. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demoulin JB, Ericsson J, Kallin A, Rorsman C, Ronnstrand L, Heldin CH. Platelet-derived growth factor stimulates membrane lipid synthesis through activation of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and sterol regulatory element-binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35392–35402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Essaghir A, Dif N, Marbehant CY, Coffer PJ, Demoulin JB. The Transcription of FOXO Genes Is Stimulated by FOXO3 and Repressed by Growth Factors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10334–10342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808848200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Essaghir A, Toffalini F, Knoops L, Kallin A, van Helden J, Demoulin JB. Transcription factor regulation can be accurately predicted from the presence of target gene signatures in microarray gene expression data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e120. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fambrough D, McClure K, Kazlauskas A, Lander ES. Diverse signaling pathways activated by growth factor receptors induce broadly overlapping, rather than independent, sets of genes. Cell. 1999;97:727–741. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80785-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Demoulin JB, Seo JK, Ekman S, Grapengiesser E, Hellman U, Ronnstrand L, Heldin CH. Ligand-induced recruitment of Na+/H+- exchanger regulatory factor to the PDGF (platelet-derived growth factor) receptor regulates actin cytoskeleton reorganization by PDGF. Biochem J. 2003;376:505–510. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi Y, Morales FC, Kreimann EL, Georgescu MM. PTEN tumor suppressor associates with NHERF proteins to attenuate PDGF receptor signaling. Embo J. 2006;25:910–920. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joazeiro CA, Wing SS, Huang H, Leverson JD, Hunter T, Liu YC. The tyrosine kinase negative regulator c-Cbl as a RING-type, E2- dependent ubiquitin-protein ligase. Science. 1999;286:309–312. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lennartsson J, Wardega P, Engstrom U, Hellman U, Heldin CH. Alix facilitates the interaction between c-Cbl and platelet-derived growth factor beta-receptor and thereby modulates receptor down-regulation. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:39152–39158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608489200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reddi AL, Ying G, Duan L, Chen G, Dimri M, Douillard P, Druker BJ, Naramura M, Band V, Band H. Binding of Cbl to a phospholipase Cgamma1-docking site on platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta provides a dual mechanism of negative regulation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29336–29347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701797200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yokouchi M, Wakioka T, Sakamoto H, Yasukawa H, Ohtsuka S, Sasaki A, Ohtsubo M, Valius M, Inoue A, Komiya S, Yoshimura A. APS, an adaptor protein containing PH and SH2 domains, is associated with the PDGF receptor and c-Cbl and inhibits PDGF-induced mitogenesis. Oncogene. 1999;18:759–767. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Turner N, Grose R. Fibroblast growth factor signalling: from development to cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:116–129. doi: 10.1038/nrc2780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaminski WE, Lindahl P, Lin NL, Broudy VC, Crosby JR, Hellstrom M, Swolin B, Bowen-Pope DF, Martin PJ, Ross R, Betsholtz C, Raines EW. Basis of hematopoietic defects in platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-B and PDGF β- receptor null mice. Blood. 2001;97:1990–1998. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.7.1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Heldin CH, Westermark B. Mechanism of action and in vivo role of platelet-derived growth factor. Physiol Rev. 1999;79:1283–1316. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1999.79.4.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Demoulin JB. No PDGF receptor signal in pericytes without endosialin? Cancer Biol Ther. 2010;9:916–918. doi: 10.4161/cbt.9.11.12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hellberg C, Ostman A, Heldin CH. PDGF and vessel maturation. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2010;180:103–114. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-78281-0_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buetow BS, Crosby JR, Kaminski WE, Ramachandran RK, Lindahl P, Martin P, Betsholtz C, Seifert RA, Raines EW, Bowen- Pope DF. Platelet-derived growth factor B-chain of hematopoietic origin is not necessary for granulation tissue formation and its absence enhances vascularization. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1869–1876. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63033-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bock O, Loch G, Busche G, von Wasielewski R, Schlue J, Kreipe H. Aberrant expression of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and PDGF receptor-α is associated with advanced bone marrow fibrosis in idiopathic myelofibrosis. Haematologica. 2005;90:133–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ye JY, Chan GC, Qiao L, Lian Q, Meng FY, Luo XQ, Khachigian LM, Ma M, Deng R, Chen JL, Chong BH, Yang M. Platelet-derived growth factor enhances platelet recovery in a murine model of radiation-induced thrombocytopenia and reduces apoptosis in megakaryocytes via its receptors and the PI3-k/Akt pathway. Haematologica. 2010;95:1745–1753. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.020958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vassbotn FS, Havnen OK, Heldin CH, Holmsen H. Negative feedback regulation of human platelets via autocrine activation of the platelet-derived growth factor α-receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:13874–13879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Su RJ, Li K, Yang M, Zhang XB, Tsang KS, Fok TF, Li CK, Yuen PM. Platelet-derived growth factor enhances ex vivo expansion of megakaryocytic progenitors from human cord blood. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;27:1075–1080. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Su RJ, Zhang XB, Li K, Yang M, Li CK, Fok TF, James AE, Pong H, Yuen PM. Platelet-derived growth factor promotes ex vivo expansion of CD34+ cells from human cord blood and enhances long-term culture-initiating cells, non-obese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient repopulating cells and formation of adherent cells. Br J Haematol. 2002;117:735–746. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michalevicz R, Katz F, Stroobant P, Janossy G, Tindle RW, Hoffbrand AV. Platelet-derived growth factor stimulates growth of highly enriched multipotent haemopoietic progenitors. Br J Haematol. 1986;63:591–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1986.tb07537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan XQ, Brady G, Iscove NN. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) activates primitive hematopoietic precursors (pre-CFCmulti) by up-regulating IL-1 in PDGF receptor-expressing macrophages. J Immunol. 1993;150:2440–2448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cashman JD, Eaves AC, Raines EW, Ross R, Eaves CJ. Mechanisms that regulate the cell cycle status of very primitive hematopoietic cells in long-term human marrow cultures. I. Stimulatory role of a variety of mesenchymal cell activators and inhibitory role of TGF-β. Blood. 1990;75:96–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Delwiche F, Raines E, Powell J, Ross R, Adamson J. Platelet-derived growth factor enhances in vitro erythropoiesis via stimulation of mesenchymal cells. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:137–142. doi: 10.1172/JCI111936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hasselbalch HC, Bjerrum OW, Jensen BA, Clausen NT, Hansen PB, Birgens H, Therkildsen MH, Ralfkiaer E. Imatinib mesylate in idiopathic and postpolycythemic myelofibrosis. Am J Hematol. 2003;74:238–242. doi: 10.1002/ajh.10431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mesa RA. New drugs for the treatment of myelofibrosis. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2010;5:15–21. doi: 10.1007/s11899-009-0037-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martinet Y, Bitterman PB, Mornex JF, Grotendorst GR, Martin GR, Crystal RG. Activated human monocytes express the c-sis protooncogene and release a mediator showing PDGF-like activity. Nature. 1986;319:158–160. doi: 10.1038/319158a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kozaki K, Kaminski WE, Tang J, Hollenbach S, Lindahl P, Sullivan C, Yu JC, Abe K, Martin PJ, Ross R, Betsholtz C, Giese NA, Raines EW. Blockade of platelet-derived growth factor or its receptors transiently delays but does not prevent fibrous cap formation in ApoE null mice. Am J Pathol. 2002;161:1395–1407. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64415-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vignaud JM, Marie B, Klein N, Plenat F, Pech M, Borrelly J, Martinet N, Duprez A, Martinet Y. The role of platelet-derived growth factor production by tumor-associated macrophages in tumor stroma formation in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:5455–5463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Inaba T, Shimano H, Gotoda T, Harada K, Shimada M, Ohsuga J, Watanabe Y, Kawamura M, Yazaki Y, Yamada N. Expression of platelet-derived growth factor β receptor on human monocyte-derived macrophages and effects of platelet-derived growth factor BB dimer on the cellular function. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:24353–24360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lo Re S, Lecocq M, Uwambayinema F, Yakoub Y, Delos M, Demoulin JB, Lucas S, Sparwasser T, Renauld JC, Lison D, Huaux F. PDGF-Producing CD4+ Foxp3+ Regulatory T Lymphocytes Promote Lung Fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:1270–1281. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0516OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gersuk GM, Chang WC, Pattengale PK. Inhibition of human natural killer cell activity by platelet-derived growth factor. II. Membrane binding studies, effects of recombinant IFN-α and IL-2, and lack of effect on T cell and antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 1988;141:4031–4038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daynes RA, Dowell T, Araneo BA. Platelet-derived growth factor is a potent biologic response modifier of T cells. J Exp Med. 1991;174:1323–1333. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.6.1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adachi T, Hanaka S, Yano T, Yamamura K, Yoshihara H, Nagase H, Chihara J, Ohta K. The role of platelet-derived growth factor receptor in eotaxin signaling of eosinophils. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2006;140:28–34. doi: 10.1159/000092708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Waterfield MD, Scrace GT, Whittle N, Stroobant P, Johnsson A, Wasteson A, Westermark B, Heldin CH, Huang JS, Deuel TF. Platelet-derived growth factor is structurally related to the putative transforming protein p28sis of simian sarcoma virus. Nature. 1983;304:35–39. doi: 10.1038/304035a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shimizu A, O'Brien KP, Sjoblom T, Pietras K, Buchdunger E, Collins VP, Heldin CH, Dumanski JP, Ostman A. The dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans-associated collagen type Iα 1/platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) B-chain fusion gene generates a transforming protein that is processed to functional PDGF- BB. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3719–3723. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pantazis P, Sariban E, Bohan CA, Antoniades HN, Kalyanaraman VS. Synthesis of PDGF by cultured human T cells transformed with HTLV-I and II. Oncogene. 1987;1:285–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang J, Liu X, Nyland SB, Zhang R, Ryland LK, Broeg K, Baab KT, Jarbadan NR, Irby R, Loughran TP Jr. Platelet-derived growth factor mediates survival of leukemic large granular lymphocytes via an autocrine regulatory pathway. Blood. 2010;115:51–60. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-223719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goustin AS, Galanopoulos T, Kalyanaraman VS, Pantazis P. Coexpression of the genes for platelet-derived growth factor and its receptor in human T-cell lines infected with HTLV-I. Growth Factors. 1990;2:189–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trejo SR, Fahl WE, Ratner L. The tax protein of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 mediates the transactivation of the c-sis/ platelet-derived growth factor-B promoter through interactions with the zinc finger transcription factors Sp1 and NGFI-A/Egr-1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27411–27421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chi KD, McPhee RA, Wagner AS, Dietz JJ, Pantazis P, Goustin AS. Integration of proviral DNA into the PDGF β-receptor gene in HTLV-I-infected T-cells results in a novel tyrosine kinase product with transforming activity. Oncogene. 1997;15:1051–1057. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Medves S, Demoulin JB. Tyrosine kinase gene fusions in cancer: translating mechanisms into targeted therapies. J Cell Mol Med. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01415.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01415.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cools J, DeAngelo DJ, Gotlib J, Stover EH, Legare RD, Cortes J, Kutok J, Clark J, Galinsky I, Griffin JD, Cross NC, Tefferi A, Malone J, Alam R, Schrier SL, Schmid J, Rose M, Vandenberghe P, Verhoef G, Boogaerts M, Wlodarska I, Kantarjian H, Marynen P, Coutre SE, Stone R, Gilliland DG. A tyrosine kinase created by fusion of the PDGFRA and FIP1L1 genes as a therapeutic target of imatinib in idiopathic hypereosinophilic syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1201–1214. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Metzgeroth G, Walz C, Erben P, Popp H, Schmitt-Graeff A, Haferlach C, Fabarius A, Schnittger S, Grimwade D, Cross NC, Hehlmann R, Hochhaus A, Reiter A. Safety and efficacy of imatinib in chronic eosinophilic leukaemia and hypereosinophilic syndrome: a phase-II study. Br J Haematol. 2008;143:707–715. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.von Bubnoff N, Gorantla SP, Engh RA, Oliveira TM, Thone S, Aberg E, Peschel C, Duyster J. The low frequency of clinical resistance to PDGFR inhibitors in myeloid neoplasms with abnormalities of PDGFRA might be related to the limited repertoire of possible PDGFRA kinase domain mutations in vitro. Oncogene. 2011;30:933–943. doi: 10.1038/onc.2010.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tefferi A, Vardiman JW. Classification and diagnosis of myeloproliferative neoplasms: the 2008 World Health Organization criteria and point-of-care diagnostic algorithms. Leukemia. 2008;22:14–22. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Medves S, Duhoux FP, Ferrant A, Toffalini F, Ameye G, Libouton JM, Poirel HA, Demoulin JB. KANK1, a candidate tumor suppressor gene, is fused to PDGFRB in an imatinib-responsive myeloid neoplasm with severe thrombocythemia. Leukemia. 2010;24:1052–1055. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gandhi M, Dillon LW, Pramanik S, Nikiforov YE, Wang YH. DNA breaks at fragile sites generate oncogenic RET/PTC rearrangements in human thyroid cells. Oncogene. 2010;29:2272–2280. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burrow AA, Williams LE, Pierce LC, Wang YH. Over half of breakpoints in gene pairs involved in cancer-specific recurrent translocations are mapped to human chromosomal fragile sites. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:59. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Novo FJ, Vizmanos JL. Chromosome translocations in cancer: computational evidence for the random generation of double-strand breaks. Trends Genet. 2006;22:193–196. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Erben P, Gosenca D, Muller MC, Reinhard J, Score J, Del Valle F, Walz C, Mix J, Metzgeroth G, Ernst T, Haferlach C, Cross NC, Hochhaus A, Reiter A. Screening for diverse PDGFRA or PDGFRB fusion genes is facilitated by generic quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction analysis. Haematologica. 2010;95:738–744. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.016345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Toffalini F, Kallin A, Vandenberghe P, Pierre P, Michaux L, Cools J, Demoulin JB. The fusion proteins TEL-PDGFRβ and FIP1L1- PDGFRα escape ubiquitination and degradation. Haematologica. 2009;94:1085–1093. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2008.001149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cain JA, Xiang Z, O'Neal J, Kreisel F, Colson A, Luo H, Hennighausen L, Tomasson MH. Myeloproliferative disease induced by TEL-PDGFRB displays dynamic range sensitivity to Stat5 gene dosage. Blood. 2007;109:3906–3914. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-036335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Carroll M, Tomasson MH, Barker GF, Golub TR, Gilliland DG. The TEL/platelet-derived growth factor β receptor (PDGFβ R) fusion in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia is a transforming protein that self-associates and activates PDGFβ R kinase-dependent signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14845–14850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Toffalini F, Hellberg C, Demoulin JB. Critical role of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor (PDGFR) β transmembrane domain in the TEL-PDGFRβ cytosolic oncoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:12268–12278. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.076638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dierov J, Xu Q, Dierova R, Carroll M. TEL/ platelet-derived growth factor receptor β activates phosphatidylinositol 3 (PI3) kinase and requires PI3 kinase to regulate the cell cycle. Blood. 2002;99:1758–1765. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sternberg DW, Tomasson MH, Carroll M, Curley DP, Barker G, Caprio M, Wilbanks A, Kazlauskas A, Gilliland DG. The TEL/ PDGFβ R fusion in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia signals through STAT5-dependent and STAT5-independent pathways. Blood. 2001;98:3390–3397. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.12.3390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Besancon F, Atfi A, Gespach C, Cayre YE, Bourgeade MF. Evidence for a role of NF-κB in the survival of hematopoietic cells mediated by interleukin 3 and the oncogenic TEL/ platelet-derived growth factor receptor β fusion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:8081–8086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.8081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Atfi A, Prunier C, Mazars A, Defachelles AS, Cayre Y, Gespach C, Bourgeade MF. The oncogenic TEL/PDGFR β fusion protein induces cell death through JNK/SAPK pathway. Oncogene. 1999;18:3878–3885. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wheadon H, Welham MJ. The coupling of TEL/ PDGFβ R to distinct functional responses is modulated by the presence of cytokine: involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinases. Blood. 2003;102:1480–1489. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tomasson MH, Sternberg DW, Williams IR, Carroll M, Cain D, Aster JC, Ilaria RL Jr, Van Etten RA, Gilliland DG. Fatal myeloproliferation, induced in mice by TEL/PDGFβ R expression, depends on PDGFβ R tyrosines 579/581. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:423–432. doi: 10.1172/JCI8902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fukushima K, Matsumura I, Ezoe S, Tokunaga M, Yasumi M, Satoh Y, Shibayama H, Tanaka H, Iwama A, Kanakura Y. FIP1L1- PDGFRalpha imposes eosinophil lineage commitment on hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:7719–7732. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807489200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dobbin E, Graham C, Freeburn RW, Unwin RD, Griffiths JR, Pierce A, Whetton AD, Wheadon H. Proteomic analysis reveals a novel mechanism induced by the leukemic oncogene Tel/PDGFRβ in stem cells: activation of the interferon response pathways. Stem Cell Res. 2010;5:226–243. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Medves S, Noel LA, Montano-Almendras CP, Albu RI, Schoemans H, Constantinescu SN, Demoulin JB. Multiple oligomerization domains of KANK1-PDGFRB are required for JAK2-independent hematopoietic cell proliferation and signaling via STAT5 and ERK. Haematologica. 2011;96:1406–1414. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.040147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ross TS, Gilliland DG. Transforming properties of the Huntingtin interacting protein 1/ platelet- derived growth factor β receptor fusion protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22328–22336. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bell CA, Tynan JA, Hart KC, Meyer AN, Robertson SC, Donoghue DJ. Rotational coupling of the transmembrane and kinase domains of the Neu receptor tyrosine kinase. Mol Biol Cell. 2000;11:3589–3599. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.10.3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saint-Dic D, Chang SC, Taylor GS, Provot MM, Ross TS. Regulation of the Src homology 2-containing inositol 5-phosphatase SHIP1 in HIP1/PDGFβ R-transformed cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:21192–21198. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008336200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gotlib J, Cools J. Five years since the discovery of FIP1L1-PDGFRA: what we have learned about the fusion and other molecularly defined eosinophilias. Leukemia. 2008;22:1999–2010. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pardanani A, Ketterling RP, Brockman SR, Flynn HC, Paternoster SF, Shearer BM, Reeder TL, Li CY, Cross NC, Cools J, Gilliland DG, Dewald GW, Tefferi A. CHIC2 deletion, a surrogate for FIP1L1-PDGFRA fusion, occurs in systemic mastocytosis associated with eosinophilia and predicts response to imatinib mesylate therapy. Blood. 2003;102:3093–3096. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Metzgeroth G, Walz C, Score J, Siebert R, Schnittger S, Haferlach C, Popp H, Haferlach T, Erben P, Mix J, Muller MC, Beneke H, Muller L, Del Valle F, Aulitzky WE, Wittkowsky G, Schmitz N, Schulte C, Muller-Hermelink K, Hodges E, Whittaker SJ, Diecker F, Dohner H, Schuld P, Hehlmann R, Hochhaus A, Cross NC, Reiter A. Recurrent finding of the FIP1L1- PDGFRA fusion gene in eosinophilia-associated acute myeloid leukemia and lymphoblastic T-cell lymphoma. Leukemia. 2007;21:1183–1188. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Crescenzi B, Chase A, Starza RL, Beacci D, Rosti V, Galli A, Specchia G, Martelli MF, Vandenberghe P, Cools J, Jones AV, Cross NC, Marynen P, Mecucci C. FIP1L1-PDGFRA in chronic eosinophilic leukemia and BCR-ABL1 in chronic myeloid leukemia affect different leukemic cells. Leukemia. 2007;21:397–402. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Irusta PM, Luo Y, Bakht O, Lai CC, Smith SO, DiMaio D. Definition of an inhibitory juxtamembrane WW-like domain in the platelet-derived growth factor β receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38627–38634. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204890200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Stover EH, Chen J, Folens C, Lee BH, Mentens N, Marynen P, Williams IR, Gilliland DG, Cools J. Activation of FIP1L1-PDGFRα requires disruption of the juxtamembrane domain of PDGFRα and is FIP1L1-independent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8078–8083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601192103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Buitenhuis M, Verhagen LP, Cools J, Coffer PJ. Molecular mechanisms underlying FIP1L1- PDGFRA-mediated myeloproliferation. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3759–3766. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Goss VL, Lee KA, Moritz A, Nardone J, Spek EJ, MacNeill J, Rush J, Comb MJ, Polakiewicz RD. A common phosphotyrosine signature for the Bcr-Abl kinase. Blood. 2006;107:4888–4897. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Burgstaller S, Kreil S, Waghorn K, Metzgeroth G, Preudhomme C, Zoi K, White H, Cilloni D, Zoi C, Brito-Babapulle F, Walz C, Reiter A, Cross NC. The severity of FIP1L1-PDGFRA-positive chronic eosinophilic leukaemia is associated with polymorphic variation at the IL5RA locus. Leukemia. 2007;21:2428–2432. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Corless CL, Schroeder A, Griffith D, Town A, McGreevey L, Harrell P, Shiraga S, Bainbridge T, Morich J, Heinrich MC. PDGFRA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors: frequency, spectrum and in vitro sensitivity to imatinib. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005;23:5357–5364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hiwatari M, Ono R, Taki T, Hishiya A, Ishii E, Kitamura T, Hayashi Y, Nosaka T. Novel gain-of-function mutation in the extracellular domain of the PDGFRA gene in infant acute lymphoblastic leukemia with t(4;11)(q21;q23) Leukemia. 2008;22:2279–2280. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hiwatari M, Taki T, Tsuchida M, Hanada R, Hongo T, Sako M, Hayashi Y. Novel missense mutations in the tyrosine kinase domain of the platelet-derived growth factor receptor α(PDGFRA) gene in childhood acute myeloid leukemia with t(8;21)(q22;q22) or inv (16)(p13q22) Leukemia. 2005;19:476–477. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Monma F, Nishii K, Lorenzo Ft, Usui E, Ueda Y, Watanabe Y, Kawakami K, Oka K, Mitani H, Sekine T, Tamaki S, Mizutani M, Yagasaki F, Doki N, Miyawaki S, Katayama N, Shiku H. Molecular analysis of PDGFRα/β genes in core binding factor leukemia with eosinophilia. Eur J Haematol. 2006;76:18–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2005.00543.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]