Abstract

Virus-like particles can be formed by self-assembly of capsid protein (CP) with RNA molecules of increasing length. If the protein “insisted” on a single radius of curvature, the capsids would be identical in size, independent of RNA length. However, there would be a limit to length of the RNA, and one would not expect RNA much shorter than native viral RNA to be packaged unless multiple copies were packaged. On the other hand, if the protein did not favor predetermined capsid size, one would expect the capsid diameter to increase with increase in RNA length. Here we examine the self-assembly of CP from cowpea chlorotic mottle virus with RNA molecules ranging in length from 140 to 12,000 nucleotides (nt). Each of these RNAs is completely packaged if and only if the protein/RNA mass ratio is sufficiently high; this critical value is the same for all of the RNAs and corresponds to equal RNA and N-terminal-protein charges in the assembly mix. For RNAs much shorter in length than the 3,000 nt of the viral RNA, two or more molecules are assembled into 24- and 26-nm-diameter capsids, whereas for much longer RNAs (>4,500 nt), a single RNA molecule is shared/packaged by two or more capsids with diameters as large as 30 nm. For intermediate lengths, a single RNA is assembled into 26-nm-diameter capsids, the size associated with T=3 wild-type virus. The significance of these assembly results is discussed in relation to likely factors that maintain T=3 symmetry in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

Many mature infectious viruses with positive-sense RNA genomes are known to consist of a single copy of the genome inside a one-molecule-thick shell of protein (the capsid protein [CP]). In many instances, this nucleocapsid structure is believed to arise spontaneously from self-assembly of the protein around its associated nucleic acid, a process that has been mimicked in vitro by direct mixing of the two purified components (i.e., CP and RNA) in an optimized physiological buffer. A particularly well-studied example is that of cowpea chlorotic mottle virus (CCMV), first synthesized in the laboratory in 1967 (8). The native virus has a multipartite genome encoding four genes contained in three single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) molecules: RNA1, 3,171 nucleotides (nt); RNA2, 2,774 nt; and RNA3, 2,173 nt (2, 18). The first two genomic RNAs are packaged alone, and the third genomic RNA is copackaged with a subgenomic RNA4 of 824 nt, so that each CCMV virion contains about 3,000 nt. Just 2 years later, it was demonstrated that CCMV CP was also capable of packaging heterologous ssRNA, as well as synthetic anionic polymers (9). A more extensive study of CCMV CP assembly around four heterologous viral RNAs ranging in length from 4,000 to 6,400 nt and around short homopolynucleotides [poly(A), poly(C), and poly(U))] was carried out by Adolph and Butler (1).

Similarly, the CP of a closely related virus, brome mosaic virus (BMV), has been shown to package gold nanoparticles of various sizes that have been functionalized with anionic moieties (43) and a negatively charged near-infrared chromophore (26). Also, we have investigated the packaging by CCMV CP of poly(styrene sulfonate) (PSS) polymers with molecular masses ranging from 38 kDa to 3.4 MDa (12, 23). We chose to examine PSS because its physical properties are well established: it has a persistence length and charge density comparable to that of ssRNA, it has solution properties (e.g., radius of gyration) that are well understood, and it is readily available in a large range of molecular masses. Carrying out assemblies of virus-like particles (VLPs) for mixes of CCMV CP with PSS of various molecular masses, we determined the effects of polymer length on the formation of VLPs of different sizes (23) and explained the observed behavior in terms of a competition between the polymer-polymer and polymer-capsid interactions and the preferred curvature of the CP, as discussed by Zandi and van der Schoot (49). In particular, we found that a large range of PSS lengths (and hence charges) could be accommodated by the same size protein capsid, up to a certain threshold length at which larger capsids begin to form as the dominant assembly product (12, 23).

In the findings reported here we extend this study of VLP self-assembly to include a broader range of polyanion lengths and capsid sizes. Also, while we continue to use the same (CCMV) CP, we now feature—instead of PSS—ssRNA molecules with molecular masses varying over a larger range, from about 45 kDa (140 nt) to 4 MDa (12,000 nt).

There are several reasons for working with ssRNA instead of PSS. First, ssRNA is the genome of CCMV and of a majority of viruses pathogenic to plants, animals, and humans. Second, from a physical point of view, RNA is not a linear polymer like PSS. Self-complementary base-pairing interactions in ssRNA lead to a branched structure containing double-stranded and single-stranded regions that are organized with respect to each other into complex tertiary structures. As a consequence, the radius of gyration and shape of the RNA increase and change with molecular mass in ways that are difficult to predict (48), and it must be expected to interact very differently with CP (10) than does a linear homopolymer such as PSS.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

Restriction enzymes were obtained from New England Biolabs. SP6 RNA polymerase was obtained from Ambion and T7 RNA polymerase was a gift from Feng Guo (Department of Biological Chemistry, University of California, Los Angeles). Enzymes were used as recommended by the manufacturer. The plasmids were grown, purified, and analyzed by standard methods (39). Plasmids pT7B1 and pT7B3Sn contain full-length cDNA clones corresponding to BMV RNA 1 (B1) (3,234 nt) and BMV RNA 3 (B3) (2,117 nt), respectively (17), and plasmids p30B, pEYFP-Rep, and pTE12 encode the full length of TMV RNA (6,395 nt) (15), a Sindbis-derived replicon RNA containing enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (8,600 nt) and full-length Sindbis virus RNA (11,700 nt), respectively (30). The plasmids were grown, purified, and analyzed by standard methods. All of the other chemicals used were DNase-, RNase-, and protease-free.

Combining B1 and B3 RNAs by directional subcloning.

Directional subcloning of pT7B1 requires the plasmid to have overhangs; these were created by linearization with BamHI and EcoRI. The insert that encodes B3 was engineered from pT7B3Sn by PCR using the forward primer d(TTGCGCGGATCCAACTAATTCTCGTTCG) (the BamHI site is underlined) and the reverse primer d(TGGCCGGAATTCAACACTGTACGGTAC) (the EcoRI site is underlined). These primers give 8 and 28 fewer nucleotides at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively, than genomic BMV RNA 3. The resulting PCR product was double digested with EcoRI and BamHI and subcloned into pT7B1 previously digested with BamHI/EcoRI to give the new cloning cDNA, pRDCT7B1B3. The authenticity of ligated product, RNA B1+B3, was confirmed by restriction analysis followed by sequencing.

PCR amplification of DNA templates to transcribe short RNAs.

DNA templates with lengths shorter than BMV RNA 1 were prepared by PCR of pT7B1 plasmid; all truncations were carried out from the 3′ end. We used the universal 5′ primer d(TAATACGACTCACTATAGGTAGACCACGGAACGAGGTTC) (the T7 promoter is underlined) and, as reverse primers, d(GCAATCAACTTCAGCAAATCG), d(CACATCCTCTCCTCATGTC), d(GTCTTCAAACCATACACAGTG), d(CTTGCTCAAATTCTTCAACG), and d(GGATACAACCAGTTACCGTTG) to obtain the corresponding DNA templates for transcribing RNAs with lengths of 141, 499, 999, 1,498 and 1,960 nt, respectively.

RNA transcription.

Plasmids pT7B3Sn and pT7B1 were linearized with BamHI, plasmids p30B and pTE12 were linearized with XhoI, and plasmid pEYFP-Rep was linearized with SacI. pRDCT7B1B3 was linearized with BglII and EcoRI to produce RNA transcripts of 4,452 and 5,319 nt, respectively. All of the templates were purified by standard procedures (39). All DNA templates and plasmids encoding for RNAs between 140 and 6,395 nt were transcribed with T7 RNA polymerase; plasmids pEYFP and pTE12 were transcribed with SP6 RNA polymerase.

CCMV CP purification.

CCMV was purified from infected California cowpea plant (Vigna ungiculata cv. Black Eye) (7), and capsid protein was isolated largely as described previously (3). Nucleocapsids were disrupted by 24-h dialysis against disassembly buffer (0.5 M CaCl2, 50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]) at 4°C and then by ultracentrifugation at 100,000 rpm for 100 min (4 × 105 × g) at 4°C in a Beckman TLA110 rotor. The RNA was pelleted, and the CP was extracted from the supernatant in different fractions. Each fraction was immediately dialyzed against protein buffer (1 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris [pH 7.2], 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF). The protein concentration and its purity, with respect to RNA contamination, were measured by UV-Vis spectrophotometry; only protein solutions with 280/260 ratios greater than 1.5 were used for assembly. SDS-PAGE and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry were used to ascertain that the purified protein was not cleaved.

In vitro assembly: preliminary titrations and gel retardation assays.

Assembly reactions of CCMV CP with RNAs of different lengths were performed in RNA assembly buffer (RAB; 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2]). CCMV CP was titrated at different mass ratios into a constant RNA concentration (30 ng/μl). After overnight assembly at 4°C, a 10-μl aliquot of each ratio was mixed with 2 μl of 100% glycerol (RNase-, DNase-, and protease-free) and loaded into a 1% agarose gel (EMD) in either virus buffer (0.1 M sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA [pH 4.8]) or electrophoresis buffer (0.1 M sodium acetate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 6). The samples were electrophoresed for 1.25 h at 70 V (electrophoresis buffer) or 4 h at 50 V (virus buffer) in a horizontal gel apparatus (Fisher) at 4°C. The samples were then stained in a solution of 5 μg of ethidium bromide/ml and visualized with an Alphaimager system.

In vitro assembly of VLPs.

Dissociated CCMV CP subunits and desired RNA (30 ng/μl) transcripts were mixed in a ratio of 6:1 (wt/wt) and then dialyzed for 24 h at 4°C against RAB. The samples were then dialyzed against virus suspension buffer (50 mM sodium acetate, 8 mM magnesium acetate [pH 4.5]) for at least 4 h. For assemblies with RNAs longer than BMV RNA1, 100 to 300 μl of the assembly reactions were subjected to sucrose gradient (10 to 40% [wt/wt]) centrifugation in virus buffer using an ultracentrifuge SW 50.1 rotor at 33,000 rpm (1.3 × 105 × g) for 2 h. The fraction corresponding to the VLPs was recovered and dialyzed overnight against virus buffer or virus suspension buffer to remove the sucrose. VLPs from all RNA assemblies were purified and concentrated by washing with virus suspension buffer using a 100-kDa Amicon centrifuge filter (0.5 ml) at 3,000 × g for 5 min; this last step was repeated four times. All of the procedures were carried out at 4°C. Finally, the samples were characterized by UV-Vis spectroscopy with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Fisher).

TEM analysis of VLPs.

For negative staining, purified VLPs were applied to glow-discharged copper grids (400-mesh) that previously had been coated with Parlodion and carbon. A 6-μl aliquot of VLPs was spread onto the grid for 1 min, blotted with Whatman filter paper, and then stained with 6 μl of 1% uranyl acetate for 1 min. Excess stain was removed by blotting with filter paper. The samples were stored overnight in a desiccator and analyzed with a JEM 1200-EX transmission electron microscope equipped with a wide-angle (top mount) BioScan 600-W 1×1K pixel digital camera operated at 80 keV. The reported average diameter of the VLPs is that of the geometric mean of two orthogonal measurements of the capsids obtained with ImageJ (U.S. National Institutes of Health) software from recorded images.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

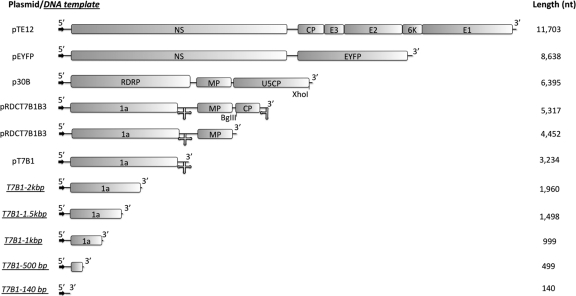

The structures of the cDNA templates for the RNAs whose self-assembly with CCMV CP is studied here are shown schematically in Fig. 1. The shorter molecules consist of BMV RNA1 (3,200 nt) and RNAs (140, 500, 1,000, 1,500, and 2,000 nt) obtained from it by successively longer truncations at the 3′ end. The longer RNAs include the 5,300-nt ligation product of BMV RNA 1 with the 2,117-nt BMV RNA 3, a 4,500-nt fragment lacking the 3′ end of this composite, the genome of tobacco mosaic virus (6,400 nt), and two RNAs derived from the RNA genome of mammalian Sindbis virus—an 8,600-nt RNA made from replacement of its structural protein genes with the enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP) gene and the 11,703-nt genome of Sindbis virus itself. Although packaging signals have been identified for the assembly of BMV CP protein around BMV RNA (38), no such sequences have been identified for CCMV (3). In any case, by using CCMV CP to package RNAs derived from BMV, we minimized the possible effects of any specific CCMV packaging signals, allowing us to focus on the generic effects of size and charge.

Fig 1.

Schematic representation of the plasmids and DNA templates used for RNA syntheses. The arrows denote the transcription promoter, and the cloverleaf at the 3′ end represents the highly conserved tRNA-like structure (3′TLS) in the corresponding RNA transcripts. The boxes represent the open reading frames of the RNAs; 1a is a viral replicase; MP and CP are the movement protein and capsid protein, respectively; E1, E2, E3, and 6K are structural proteins; and NS represents all nonstructural viral proteins for Sindbis virus. EYFP is the sequence that encodes for the enhanced yellow fluorescent protein, RDRP denotes the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase genes, and U5CP is the CP gene of strain U5 of tobacco mild green mosaic virus. The representations of the plasmid templates are scaled to their relative lengths.

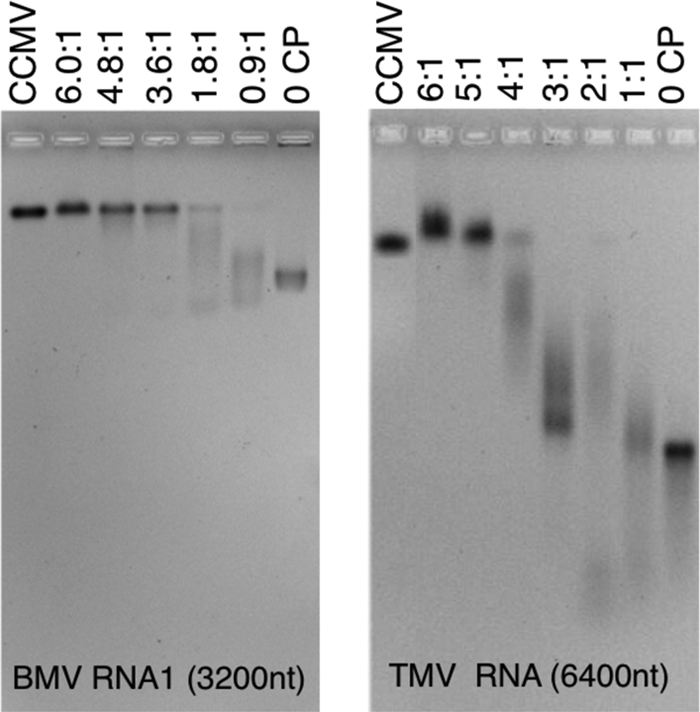

The packaging experiments were preceded by studies to identify the optimal molar ratio of CP to RNA for packaging. This is the ratio at which there is just sufficient protein to package all of the RNA into RNase-resistant VLPs. It was identified by carrying out, in parallel, assembly reactions in RAB using a variety of protein/RNA (wt/wt) ratios. Each fixed-ratio protein/RNA solution was allowed to equilibrate for 24 h and then dialyzed against virus suspension buffer before being analyzed by agarose gel retardation assays. The results in each case, as illustrated in Fig. 2 by the assemblies with BMV RNA1 (3,200 nt) and TMV RNA (6,400 nt), were similar. As protein is added to the RNA (i.e., moving from right to left in the gels), the bands, which indicate small protein-RNA aggregates for low CP/RNA (wt/wt) ratios, first migrate faster and then increasingly more slowly as the ratio increases, finally appearing at the same position as wild-type (wt) CCMV. Note that it has been shown in the case of CCMV that the electrophoretic mobility depends only on the charge on the exterior of the capsid and not on its contents, with empty capsids migrating at precisely the same position as virions containing RNA (25). Hence, a band that migrates at the same position as wt CCMV indicates that there is an intact capsid. (Note, however, that in the case of the 6,400-nt RNA the band migrates more slowly than that of CCMV; the reason for this is discussed below.)

Fig 2.

CP-RNA assembly titrations: gel retardation assays. Shown are 1% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide. At the left is a titration of 3,217-nt BMV RNA1 with various amounts of CCMV CP ranging from 0 (right-most lane, RNA) to the “magic” ratio, 6:1 (lane second from left). CP/RNA ratios are wt/wt ratios of CP to RNA. This gel was run in electrophoresis buffer. On the right is a similar gel retardation assay carried out with 6,395-nt TMV RNA and run in virus buffer. In both gels, the leftmost lane shows the position of wt CCMV. Note, in each gel, the appearance of a smear of intensity accompanying every assembly carried out below the magic ratio.

The results of the assembly studies show RNAs of very different lengths can be completely packaged as long as the protein/RNA weight ratio is sufficiently high. It is remarkable, however, that we observe in every case that the optimal assembly weight ratio of protein to RNA is 6:1, independent of the length of the RNA. A comparable ratio was found in the in vitro packaging of CCMV RNA1 by CCMV CP; in particular, Johnson et al. (24) reported capsid-protein titration gels similar to those shown in Fig. 2, suggesting that at least 130 protein dimers per RNA (a weight ratio of 5:1) are required for the complete packaging of RNA1. This is also consistent with early work by Adolph and Butler (1), who reported a significant fraction of free RNA in their reassembly studies of CCMV involving a mass ratio of 5:1 for CP/RNA.

Simple analysis (see below) shows that the “magic ratio” value of 6:1 is associated with a condition of charge equality between the RNA and the N-terminal arginine-rich motif of the CP. Analytical ultracentrifugation results (unpublished data) confirm the gel titration results, establishing the magic ratio as the CP/RNA threshold for assuring complete packaging of the RNA, independent of RNA length. We emphasize that this 6:1 mass ratio does not depend on any assumptions or models; we are simply observing that this threshold composition in the assembly mix is required for there to be no free RNA remaining.

Again without any assumptions or models, we can say more, on a microscopic level, about the meaning of this special mass ratio. We can write the total mass of protein in the solution as MCP = nCPMMCP, where nCP is the total number of moles of CP and MMCP is the CP molecular mass (∼20,000 Da). Similarly, for the total mass of RNA, we write MRNA = nRNALRNAMMnt, where nRNA is the total number of moles of RNA, LRNA is the RNA length in nucleotides, and MMnt is the average molecular mass of a nucleotide (∼330 Da). It follows that the special ratio of the number of CP subunits (nCP) to the number of nucleotides (nnt = nRNALRNA) is given by nCP/nnt = (MMnt/MMCP) (MCP/MRNA) = (330/20,000) (6/1) = 1/10. This implies that we need one CP subunit for every 10 RNA nucleotides in order for there to be no free RNA present in the assembly mix. It does not imply that at this point we have no free protein, nor anything about the amount of cationic charge from protein that is interacting with RNA or otherwise involved in the assembly process.

Nevertheless, from the fact that at the magic ratio one CP subunit is present for each 10 nt of RNA we infer (since each CP N terminus has 10 cationic residues) that 10 N-terminal cationic residues are present for each 10 nt. Although there are other cationic residues in the CPs that could be involved in RNA binding, several different kinds of experiment (45, 14) imply strong interaction of the 10 N-terminal basic residues of the CPs with RNA, with binding energies on the order of 10 kBT (with kB the Boltzmann constant). This is also consistent with charge matching of oppositely charged colloidal particles, e.g., the nonspecific binding of proteins to DNA (16), being the main driving force for their association/binding in aqueous solution. More explicitly, due to the entropy gain associated with mobile counter-ion release (31), the free energy of polycation/nucleic acid association is roughly kBT per charge. For the +10 CP N termini, this suggests binding energies on the order of 10 kBT, implying a saturation of binding, from which we conclude that super-stoichiometric numbers of proteins are bound, specifically, 1 per 10 nt, e.g., 300 per wt length of RNA rather than the 180 that eventually form the ordered shell of a T=3 capsid.

The need for an amount of protein in excess of the stoichiometric quantity has also been demonstrated in several self-assembly studies involving CCMV CP and heterologous RNAs. For example, Adolph and Butler (1) found unencapsidated RNA following reaction of CCMV and RNAs from turnip crinkle virus (4,051 nt), bushy stunt virus (4,776 nt), turnip yellow mosaic virus (6,318 nt), and tobacco mosaic virus (6,400 nt) at CP/RNA weight ratios of 4:1, exceeding in all cases the stoichiometric ratios expected for T=3 capsids. Even if the longer RNAs assembled into T=4 capsids, the stoichiometric ratios would still be well below the 4:1 used.

The 6:1 weight ratio for complete packaging of RNA was also found by Kobayashi and Ehara (27) in their in vitro encapsidation studies of the closely related plant virus, cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), whose CP N termini also carry a charge of +10. Porterfield et al. (35) have used gel assays to examine the in vitro assembly of hepatitis B virus (HBV) core protein (molecular weight, 21,000) around CCMV RNA 1 and HBV pregenomic RNA, both 3,200 nt long, and around Xenopus elongation factor RNA, 1,900 nt in length. The HBV protein has 17 arginines at its N terminus. Taking this into account, we expect the optimal weight ratio in these experiments to be 3.6. The observed ratios are indeed ∼4.

VLP products as a function of RNA length.

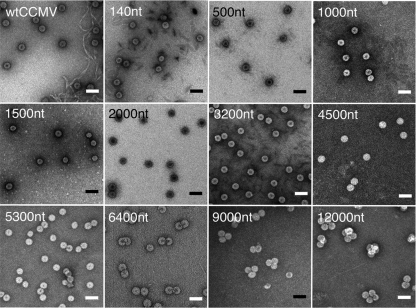

Figure 3 shows a panel of typical negative-stain electron micrographs of the assembly mixes corresponding to 6:1 CP/RNA mass ratio, for all 11 of the increasing lengths of RNA studied. The upper left-hand picture is wt CCMV. The numbers of capsids sharing a single RNA molecule (in the case of the large nucleotide lengths), the sizes of VLPs formed in each instance (Fig. 4A), and the numbers of RNAs packaged per VLP (in the case of the shorter RNA lengths) are discussed below.

Fig 3.

VLP products as a function of RNA length. Negative-stain transmission electron microscopy images of the assembly products of various lengths of ssRNA mixed with CCMV CP at the magic ratio (6:1 [wt/wt]) in RNA assembly buffer. The length of the RNA in each assembly is labeled in the upper left corner of each image. The upper leftmost image shows wt CCMV capsids. Grids were stained with uranyl acetate. Scale bars, 50 nm.

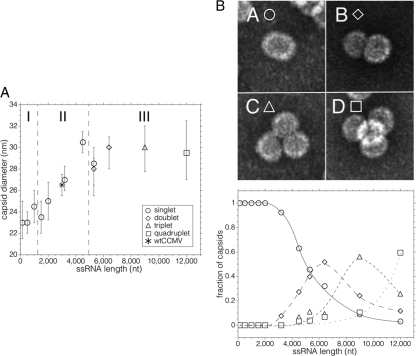

Fig 4.

(A) Average capsid diameter as a function of RNA length. A plot of the average capsid diameter as a function of the length of ssRNA packaged, with each assembly carried out at the magic ratio in RNA assembly buffer (RAB), is shown. Each average contains contributions only from the capsids associated with the predominant multiplet (i.e., singlet, doublet, triplet, or quadruplet) for the corresponding RNA length (except in the case of 5,300 nt, where equal amounts of singlets and doublets were observed). The plot is divided along the abscissa into three regions: (I) the region between 140 and ∼1,000 nt, where we find predominantly singlet capsids that contain multiple ssRNA molecules; (II) the region between ∼1,500 and ∼4,000 nt, where each singlet capsid contains only one RNA molecule (the point denoted by an asterisk corresponds to the wt CCMV virion); and (III) the region above ∼4,000 nt corresponding to the appearance of multiplet capsids sharing an RNA molecule. The error bars represent the full width at half-maximum for each distribution. (B) Fraction of multiplets as a function of RNA length. The negative-stain TEM images at the top of the panel show typical structures observed for singlets (A), doublets (B), triplets (C), and quadruplets (D). The frequency of multiplet capsids (bottom panel)—defined as the fraction of capsids present in the transmission electron microscopy as doublets (♢), triplets (△), and quadruplets (□)—increases with ssRNA length after 3,200 nt. Singlets (○) predominate for smaller lengths. Hand-drawn best-fit lines have been added to aid the eye in following the appearance and disappearance of the different multiplet populations as RNA length increases.

When Verduin and Bancroft (47) examined the assembly of CCMV CP around TMV RNA, they found some difficulty in assigning a T number to the VLPs that formed. The TEM data agreed with T=4, but sedimentation analyses were more consistent with T=7. We have already noted that the gels for the assembly of CCMV CP around TMV RNA seem to show a product at the magic ratio that migrates more slowly than wt CCMV, suggesting too that the capsid may be larger than T=3. A careful examination of the electron micrographs for the TMV VLPs makes clear the reason for this ambiguity. The majority of the capsids are paired—see, for example, the 6,400-nt frame in Fig. 3 and the upper right-hand image (“image B”) in Fig. 4B. Such doublets, which are most evident when the density of capsids in the image is not so high that the particles are all closely packed, could also be seen clearly in the early studies of TMV RNA packaging by CCMV CP (22) but were not mentioned. The doublets also account for the appearance of two sedimentation bands in Adolph and Butler's packaging studies of TMV RNA by CCMV CP (1).

Formation of multiplets.

As shown in Fig. 4B, the multiplets first appear as a small fraction of doublets for 3,200 nt RNA. The fraction of doublets observed in the micrographs increases markedly at 4,500 nt, and at the same time a few triplets can be seen. The number of singlet capsids decreases markedly with increasing RNA length and, successively, the fractions of doublets and triplets rise and go through maxima (cf. Fig. 4B, bottom). Assemblies with the 11,700-nt Sindbis virus RNA lead primarily to quadruplets and higher-order multiplets. (Note that each of the average diameters plotted in Fig. 4A contains contributions only from the capsids associated with the predominant multiplet, i.e., singlet, doublet, triplet, or quadruplet, for the corresponding RNA length.)

Doublet and triplet capsids have been observed in in vivo studies of both animal and plant viruses. Field emission scanning electron microscope images of a recombinant adenovirus show mixtures of singlet, doublet, triplet, and some higher multiplet capsids (33). After isolation, the virus was stored at −80°C and incubated at 37°C after thawing. The fraction of doublets and triplets remained relatively constant at ca. 18% over a period of 4 h, but the number of singlets decreased from 80 to 60% due to the appearance of higher-order multiplets. Unlike the doublets and triplets, the higher-order multiplets in the present study appeared to be aggregates of virus and proteinaceous material. The doublet structures have the superficial appearance of geminiviruses (50), which often form triplets and quadruplets (11). In the case of the African cassava mosaic geminiviruses containing defective interfering ssDNA, the number of multiplets increases with DNA length (21).

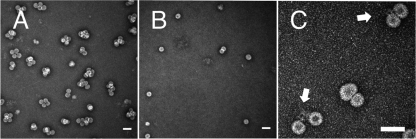

The multiplet VLPs that we observed in CCMV VLPs are unlikely to have structures akin to those of geminiviruses, in which capsids share missing pentamer faces. This is evident when the multiplets are treated with RNase, which has the effect of separating them into single shells (Fig. 5A and B) in the case of quadruplets forming from Sindbis virus RNA. Clearly, then, these multiplet capsids do not form a continuous shell; they are more likely two or more capsids that share a single molecule of RNA that is threaded through nanometer-sized holes in the capsids. Indeed, in some electron microscopy images (Fig. 5C) a bit of RNA can be seen poking out between some of them.

Fig 5.

Exposure of RNA in Multiplets. (A) Typical transmission electron microscopy image of 12,000-nt RNA assembled with CCMV CP. (B) Same assembly mixture after exposure to RNase A in virus buffer for 1 h. Note the reduction in the number of multiplets, as well as an overall reduction in the total number of capsids present. (C) Shared RNA between capsids in a multiplet. The arrows point to RNA seen linking two capsids. Scale bars, 50 nm.

Mechanism for the formation of multiplets.

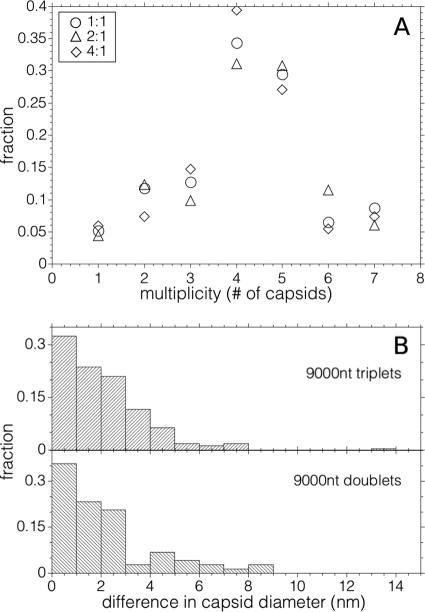

The regular appearance of increasingly higher-order multiplets with increasing RNA length is evidence that the multiplets do not simply arise from physical aggregation of assembled capsids. Moreover, the multiplets often have highly regular structures, e.g., tetrahedral for the quadruplets (Fig. 4B, micrograph D), which do not appear in large randomly organized aggregates. Also, analyses of electron micrographs of multiplets, upon successive dilutions by factors of 2 and 4 of an assembly mix involving CP and Sindbis virus RNA, show that the fraction of particles of each multiplicity is independent of dilution, indicating further that the multiplets are not simply physical aggregates (Fig. 6A).

Fig 6.

Properties of multiplets. (A) Absence of effect of 2- and 4-fold dilutions on the frequency of multiplets. The different symbols show the effect of sample dilution on fractions of multiplets of each type. The sample represented by the circles has been diluted by factors of 2 (△) and factor of 4 (◊). There is no systematic effect on the populations of multiplets with dilution. (B) Size differences between capsids within doublets and triplets formed from the assembly of 9,000-nt RNA and CCMV capsid protein.

Recent coarse-grained simulations of capsid self-assembly around a linear polymer indicate (19) that the above situation corresponds to the excess protein being bound to the polymer, saturating its adsorption sites. Indeed, the fact that all of the N-terminal charge on the CP is compensated for by the RNA charge is consistent with saturation of binding, i.e., the absence of free protein at the magic ratio. This situation in turn corresponds to capsid protein-polymer interactions being dominant, compared to protein-protein interactions. More explicitly, Elrad and Hagan (19) report computational results for this case in which the first step in nucleocapsid assembly involves the disordered binding of excess protein, followed by desorption of protein with reorganization of the remaining protein as a closed, icosahedral, capsid, including the polymer.

This scenario is consistent with measurements of the differences in diameter between partners in a multiplet (Fig. 6B). Although in the majority of the cases the capsid diameters are identical within the experimental uncertainty of ±1 nm, there is a significant fraction in which the size differences are larger, suggesting that the capsids share different fractions of the RNA. The decrease in the fraction of singlets and the successive rise and fall of the fractions of doublets and triplets and the rise of the fraction of quadruplets is qualitatively consistent with a model in which protein adsorption onto RNA is saturated, with fluctuations leading to unbinding of excess protein and simultaneous formation of two or more capsids once the RNA is close to twice the wild-type length or longer.

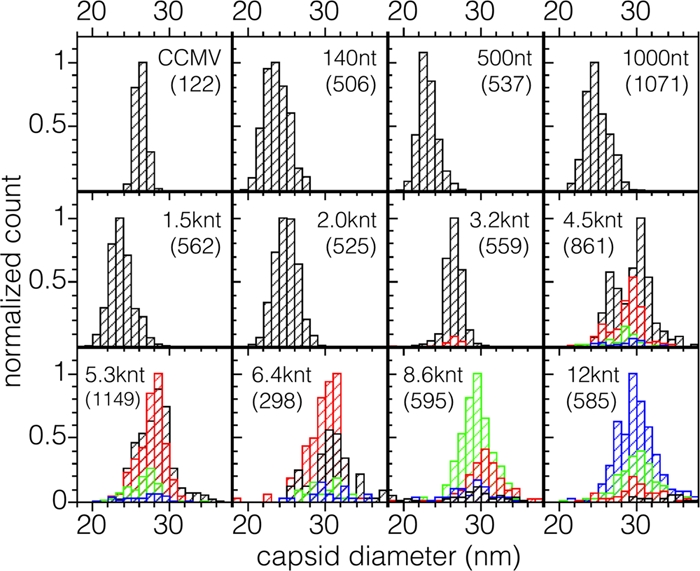

Distributions of diameters determined from electron micrographs are shown by the histograms in Fig. 7 for the 11 RNAs studied. Also included in the figure for comparison is a measurement for wt CCMV, for which the average number of packaged nucleotides is 3,000. Note that it is difficult to determine the intrinsic sizes of the VLPs in solution from the electron micrographs because, as is well known, there is shrinkage of capsids associated with the drying that occurs when the sample is deposited and stained on the grid. For example, as seen in the figure, wt CCMV, known from cryo-electron microscopy to be 28 nm in diameter in solution (20), was found by transmission electron microscopy to be 26 nm in diameter.

Fig 7.

Distribution of capsid diameters appearing in singlets and multiplets for each length of RNA packaged. Contributions from singlets, doublets, triplets, and quadruplets are shown in black, red, green, and blue, respectively. The distribution at the upper left is for wt CCMV. In each distribution the counts have been normalized to that of the most abundant size. The total numbers of particles measured are given in parentheses.

The observed capsid diameters appear to fall into three populations with diameters of 24, 26, and 30 nm. To assign these sizes unequivocally to T numbers (13) requires structure determinations. Nevertheless, it is possible to make tentative assignments on the basis of size alone and the knowledge that the RNAs packaged in single capsids are resistant to nuclease, indicating that they are contained in closed structures. Clearly, the capsids with diameters clustered around 26 nm are similar to those of wt CCMV and therefore can be assumed to have T=3 triangulation numbers. Those ∼24 nm in diameter fall into a size range that has been identified with a pseudo-Caspar-Klug “T=2” structure composed of pentamers of dimers in assemblies of BMV (28). None of the VLPs formed have diameters smaller than 20 nm, a value consistent with a T=1 triangulation number, as has been observed in assemblies of BMV (44) and of VLPs formed from CCMV protein lacking the N terminus (40).

Although there have been reports of CCMV capsids with T>3, this has not been demonstrated by structural determinations. As previously noted, we believe that the assignment, based on estimates of the sedimentation coefficient, of a triangulation number of seven to capsids formed in the assembly of CCMV protein around TMV RNA (47) was faulty because of the presence of doublets. Sun et al. (43) in their study of BMV protein assembly around functionalized gold nanoparticles observed a population of particles with diameters distinctly larger than those that have been identified as T=3. However, the distribution of sizes was very heterogeneous, and fewer than half of the gold particles had complete capsids; no attempt was made to assign a T number to them. The larger-diameter capsids that we observed, however, are homogeneous in their distribution, well-formed and closed, as evidenced by the protection they afford against RNase to the packaged RNA. If one assumes that the average area occupied by a capsid protein does not change with T number, it follows that the capsid diameter should be proportional to T1/2 (23). Thus, if the measured diameter of a T=3 capsid is 26 nm, the diameter of a T=4 capsid would be expected to be 26 nm (4/3)1/2 = 30 nm, in accordance with the size in the distributions that we have observed. Assignment of T=4 to this population therefore seems reasonable. (Note that the predicted diameter of a T=7 particle is ∼40 nm, a size inconsistent with the observed diameters.)

The appearance of multiplets rather than increasingly larger diameter capsids is attributable to the preference of CCMV CPs to form T=3 shells, which is a consequence of the protein's preference for a particular curvature. It is possible to form capsids with diameters that differ from those with the preferred curvature, but only at a cost of free energy. We have previously shown (36) how this energy cost sets a limit on the number of shells that can be formed in the multishell particles that arise in the self-assembly of CCMV CP in the absence of RNA (29). Thus, as can be seen from Fig. 3 and the accompanying size distributions shown in Fig. 7, RNAs longer than the 3,000 nt that is packaged in the wt virus can be accommodated in a T=4 capsid (and RNAs smaller than the wt in a T=2 capsid). However, still larger molecules, if they were packaged in a single particle, requiring T=7 capsids, demand too high a curvature-energy cost. The packaging of the RNA in two or more capsids of smaller diameter avoids this energy expenditure. (We attribute the appearance of a very small fraction of singlet capsids in the packaging of longer RNAs to a small amount of RNA degradation.)

For RNAs shorter than BMV RNA 1 (3,200 nt) the scenario is different. VLPs containing 2,000, 1,500, 1,000, and 140 nt RNAs are a mixture of T=2 and T=3 capsids, whereas the 500-nt RNA is predominantly packaged into T=2. The electron microscopic data for almost all of these samples (Fig. 7) show a broad VLP size distribution with a mean diameter that is intermediate between what we would expect for T=2 and T=3 capsids, indicating that both populations are significantly represented. Although it is difficult to fit these size distributions into two populations, it is clear that not all VLPs assembled from shorter RNAs have the same T=2 and T=3 populations. Only the 500-nt RNA produced a symmetric and relatively narrow distribution, with an average diameter of 23 nm, as expected for T=2 capsids (Fig. 7). From the gel retardation assays, we know that at the magic ratio all of the RNA is packaged, suggesting that for RNAs between 140 and 1,500 nt the capsids contain more than one molecule. To examine this possibility, we measured the UV-Vis absorbance of the purified VLPs.

Proteins and nucleic acids exhibit a strong UV absorption at 280 and 260 nm, respectively, so the ratio of the absorbance at 260 nm over that at 280 nm in a pure VLP solution tells us the relative amounts of RNA and CP within a capsid. Since CCMV and BMV have the same capsid size and average number of nucleotides per capsid, they have the same 260/280 absorbance ratio. By comparing this ratio to that of the VLPs and by knowing the relative capsid size populations, we obtain an initial estimate of the number of small RNAs packaged in a capsid. The 260/280 ratios for VLPs containing 3,200-, 2,000-, 1,000-, and 500-nt RNAs are indistinguishable from that of CCMV, from which we conclude that there is only one 3,200- and 2,000-nt RNA molecule per T=3 and T=2 capsid, respectively. (The number of CPs is proportional to the T number.) We can also conclude that, on average, there are two 1,000-nt RNA molecules per T=2 capsid. Similarly, since the capsids containing 500-nt RNA are T=2, there are on average four 500-nt RNA molecules per capsid. The only sample that had a ratio lower than CCMV was the one containing 1,500-nt RNA (1.5 versus 1.7 for CCMV), strongly suggesting, since T=2 is preferred over T=3 for this length, that there is a single molecule in T=2.

It is interesting that no T=1 VLPs are observed, even for the shortest RNAs (140 nt). In early work, Pfeiffer et al. (34) reported the formation of T=1 VLPs involving BMV CP, but no information is provided on the lengths of the ssRNAs. Also, in our studies of the packaging of short (38 kDa), fluorescence (rhodamine)-labeled, PSS molecules by CCMV CP, we found T=1 VLPs to be the predominant product (12). However, rough estimates of the size (radius of gyration[Rg]) of the 38-kDa PSS and of the 140-nt RNA suggest that the RNAs are smaller. It may be that a rigid-ring, rhodamine label, several nanometers in length, introduces a very different scenario for interaction of the anionic polymer with the capsid interior and hence for the preferred curvature of the VLP. Also, the branching of the RNA due to its significant secondary structure results in a different distribution of charge than for PSS. For these reasons, we expect that the preferred diameter of VLP will depend not only on the size and charge of the polymer but also on its structural nature and resulting interaction with protein.

Conclusions.

In summary, we have shown that RNA of any length—varying from 140 to 12,000 nt—can be packaged completely by CCMV CP as long as the protein/RNA mass ratio is as large as 6:1. For sufficiently short lengths (<2,000 nt), the RNA is packaged into T=2 and T=3 capsids with one to four molecules of RNA in the capsid. For sufficiently large RNAs (>4,500 nt), single molecules of RNA are packaged by two or more T=3 or T=4 capsids. Finally, for intermediate lengths, single RNAs are packaged, as with wt length, into T=3 capsids. These scenarios arise from the capsid curvature preferred by the CP and from the relative magnitudes of the CP-RNA and CP-CP interactions.

In vitro self-assembly of single capsids of CCMV having RNAs of ∼3,000 nt is reminiscent of the in vivo scenario. More explicitly, CCMV virions purified from infected leaf tissue display a remarkable homogeneity in size and physical appearance: RNA1 (3,171 nt) and RNA2 (2,774 nt) are each packaged independently into T=3 capsids, whereas RNA3 (2,173 nt) and RNA 4 (824 nt) are copackaged into a third virion. It has been shown that in vivo assembly of nucleocapsids in positive-strand RNA viruses pathogenic to humans (32), animals (4, 46), and plants (3) is functionally coupled to replication-dependent transcription and translation, i.e., the assembly is mediated by capsid protein that is translated from replication-derived mRNA (5). Consequently, macromolecular interactions, such as the interaction between CP and viral replicase (RNA1 and RNA2 gene products), resulting from commonly shared subcellular localization sites (6), might play an important role, ensuring that only one kind of stable virion population with T=3 symmetry is assembled and maintained.

Although the existence of the operationally defined magic ratio is an experimental fact, we can speculate on its implications for understanding the mechanism of viral assembly. We note that the relation of the ratio to a charge balance involving only the N-terminus basic residues seems to be at odds with the structural studies by Speir et al. (42). These authors found that 13 residues other than those on the protein tail interact with the RNA, 7 of them basic, and that the RNA “forms three distinct bulges directly under the shell near the quasi-3-fold axes, where it interacts with Lys87 residues.” It is not evident, however, that these contacts exist before a capsid is assembled. Indeed, the quasi-3-fold axes lie between two hexamers and a pentamer and, at the stage in assembly that we identified in which there is an excess of protein associated with the RNA with respect to the number of proteins necessary to form a capsid, it is unlikely that distinct capsid pentamers exist. Moreover, the structure of the protein dimers in solution has never been determined: images showing the protein conformations are simply those abstracted from the assembled capsids.

Although the simulations of assembly by Elrad and Hagan (19) are for a simplified model in which capsomer subunits adsorb onto a linear polymer represented as a freely jointed chain of spherical monomers, they can provide a basis for beginning to understand the mechanism underlying the magic ratio. These findings demonstrate that the RNA plays a significant role in assembly, so that the mechanism for the assembly of empty capsids, which has been examined in detail by Zlotnick et al. (51), is not likely to be relevant to assembly around RNA. Two limiting scenarios have been distinguished in Elrad and Hagan's work: (i) nucleation of a capsid “embryo” involving a small number of proteins, followed by growth and (ii) an “en masse” adsorption of protein subunits onto the polymer that approaches or exceeds the stoichiometric numbers required for the assembly, followed by a cooperative rearrangement to form a capsid. The controlling factors are the protein subunit-subunit interaction energy and the protein-RNA binding energy. The en masse mode of assembly is favored when the subunit interaction energy is much weaker than the driving force for subunit adsorption onto the polymer.

A nucleation and growth mechanism has been shown to apply to the in vitro assembly of turnip crinkle virus (41). In this case, both a specific nucleation center (37) and a nucleating event (the binding of a small protein complex) have been identified. Here, a magic ratio would clearly not be expected to be observed. In contrast, in the case of the assembly of the CCMV capsid protein around RNAs that we have studied, neither a specific site nor a local nucleating event can be identified. More likely, the entire RNA molecule is saturated with bound capsid protein that is present in a 70% excess over that eventually involved in the formation of capsids. Closed capsids then arise by fluctuations that lead to capsid formation and the shedding of excess protein. If the RNA is significantly shorter than 3,000 nt—the length of wt molecules packaged separately (RNA1 and RNA2)—two or more of them are packaged in capsids whose sizes are consistent with T=2 and T=3 structures, i.e., with 24- and 26-nm diameters. For RNAs with lengths around 3,000 nt, a single molecule is packaged in a 26-nm capsid. Moreover, for RNA lengths >4,500 nt, two or more capsids are involved in the packaging of a single molecule.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Feng Guo for providing the T7 polymerase and Robijn Bruinsma, Paul van der Schoot, and Roya Zandi for helpful discussions.

This study was supported by NSF grant CHE 0714411 (to C.M.K. and W.M.G.) and NIH grant 1R21AI82301 (to A.L.N.R.). R.D.C.-N. and M.C.-G. received partial support from CONACyT and UC-Mexus.

ADDENDUM IN PROOF

The existence of multiplets has also recently been reported in the case of self-assembly of CCMV CP around a conjugated polyelectrolyte (M. Brasch and J. J. M. Cornelisse, Chem. Commun. 48:1446–1448, 2012).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 28 December 2011

REFERENCES

- 1. Adolph KW, Butler PJG. 1977. Studies on the assembly of a spherical plant virus. III. Reassembly of infectious virions under mild conditions. J. Mol. Biol. 109:345–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allison RF, Janda M, Ahlquist P. 1988. Infectious in vitro transcripts from cowpea chlorotic mottle virus cDNA clones and exchange of individual RNA components with brome mosaic virus. 1988 J. Virol. 62:3581–3588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Annamalai P, Rao ALN. 2005. Dispensability of 3′ tRNA-like sequence for packaging cowpea chlorotic mottle virus genomic RNAs. Virology 332:650–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Annamalai P, Rao ALN. 2006. Packaging of brome mosaic virus subgenomic RNA is functionally coupled to replication-dependent transcription and translation of coat protein. J. Virol. 80:10096–10108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Annamalai P, Rofail F, DeMason DA, Rao ALN. 2008. Replication-coupled packaging mechanism in positive-strand RNA viruses: synchronized coexpression of functional multigenome RNA components of an animal and a plant virus in Nicotiana benthamiana cells by agroinfiltration. J. Virol. 82:1484–1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bamunusinghe D, Seo J-K, Rao ALN. 2011. Subcellular localization and rearrangement of endoplasmic reticulum by brome mosaic virus capsid protein. J. Virol. 85:2953–2963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bancroft JB. 1970. The self-assembly of spherical plant viruses. Adv. Virus Res. 16:99–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bancroft JB, Hiebert E. 1967. Formation of an infectious nucleoprotein from protein and nucleic acid isolated from a small spherical virus. Virology 32:354–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bancroft JB, Hiebert E, Bracker CE. 1969. The effects of various polyanions on shell formation of some spherical viruses. Virology 39:924–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Basnak G, et al. 2010. Viral genomic single-stranded RNA directs the pathway towards a T=3 capsid. J. Mol. Biol. 395:924–936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Briddon RW, Markham PG. 1995. Family Geminiviridae, p 158–165 In Murphy FA, et al. (ed), Virus taxonomy: archives in virology. Springer-Verlag, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cadena-Nava RD, et al. 2011. Exploiting fluorescent polymers to probe the self-assembly of virus-like particles. J. Phys. Chem. B 115:2386–2391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Caspar DLD, Klug A. 1962. Physical principles in the construction of regular viruses. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 27:1–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Choi YG, Rao ALN. 2000. Molecular studies on bromovirus capsid protein. VII. Selective packaging of BMV RNA4 by specific N-terminal arginine residues. Virology 275:207–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Choi YG, Rao ALN. 2000. Packaging of tobacco mosaic virus subgenomic RNAs by brome mosaic virus coat protein exhibits RNA controlled polymorphism. Virology 275:249–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. deHaseth PL, Lohman TM, Record MT., Jr 1977. Nonspecific interactions of lac repressor with DNA: an association reaction driven by counter-ion release. Biochemistry 16:4783–4790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dreher TW, Rao ALN, Hall TC. 1989. Replication in vivo of mutant brome mosaic virus RNAs defective in aminoacylation. J. Mol. Biol. 206:425–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dzianott A, Bujarski J. 1991. The nucleotide sequence and genome organization of the RNA-1 segment in two bromoviruses: broad bean mottle virus and cowpea chlorotic mottle virus. Virology 185:553–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Elrad OM, Hagan MF. 2010. Encapsulation of a polymer by an icosahedral virus. Phys. Biol. 7:045003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fox JM, et al. 1998. Comparison of the native CCMV virion with in vitro assembled virions by cryoelectron microscopy and image reconstruction. Virology 244:212–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frischmuth T, Ringel M, Kocher C. 2001. The size of encapsidated single-stranded DNA determines the multiplicity of African cassava mosaic virus particles. J. Gen. Virol. 82:673–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hiebert E, Bancroft JB, Bracker CF. 1968. The assembly in vitro of some small spherical viruses, and other nucleoproteins. Virology 34:492–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hu Y, Zandi R, Anavitarte A, Knobler CM, Gelbart WM. 2008. Packaging of a polymer by a viral capsid: the interplay between polymer length and capsid size. Biophys. J. 94:1428–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Johnson JM, Willits DA, Young MJ, Zlotnick A. 2004. Interaction with capsid protein alters RNA structure and the pathway for in vitro assembly of cowpea chlorotic mottle virus. J. Mol. Biol. 335:455–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Johnson MW, Wagner GW, Bancroft JB. 1973. A titrimetric and electrophoretic study of cowpea chlorotic mottle virus and its protein. J. Gen. Virol. 19:263–273 [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jung B, Rao ALN, Anvari B. 2011. Optical nano-constructs composed of genome-depleted Brome mosaic virus doped with a near infrared chromophore for potential biomedical applications. ACS Nano. 5:1243–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kobayashi A, Ehara Y. 1995. In vitro encapsidation of cucumber mosaic virus RNA species. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Jpn. 61:99–102 [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kroll MA, et al. 1999. RNA-controlled polymorphism in the in vivo assembly of a 180-subunit and 120-subunit virions from a single capsid protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:13650–13655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lavelle L, et al. 2009. Phase diagram of self-assembled viral capsid protein polymorphs. J. Phys. Chem. B 113:3813–3820 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lustig S, et al. 1988. Molecular basis of Sindbis virus neurovirulence in mice. J. Virol. 62:2329–2336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mascotti DP, Lohman TM. 1990. Thermodynamic extent of counter-ion release upon binding oligo-lysines to single-stranded nucleic acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87:3142–3146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nugent CI, Johnson KL, Sarnow P, Kirkegaard K. 1997. Functional coupling between replication and packaging of poliovirus replicon RNA. J. Virol. 73:427–435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Obenauer-Kutner LJ, et al. 2002. The use of field emission scanning electron microscopy to assess recombinant adenovirus stability. Hum. Gene Ther. 13:1687–1696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pfeifer P, Herzog M, Hirth L. 1976. Stabilization of brome mosaic virus. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 276:99–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Porterfield JZ, et al. 2010. Full-length hepatitis B virus core protein packages viral and heterologous RNA with similarly high levels of cooperativity. J. Virol. 84:7174–7184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Prinsen P, van der Schoot P, Gelbart WM, Knobler CM. 2010. Shell structures of virus capsid proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 114:5522–5533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Qu F, Morris TJ. 1997. Encapsidation of turnip crinkle virus is defined by a specific packaging signal size RNA. J. Virol. 71:1428–1435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rao ALN. 2006. Genome packaging by spherical plant RNA viruses. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 44:61–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sikkema FD, et al. 2007. Monodisperse polymer-virus hybrid nanoparticles. Org. Biomol. Chem. 5:54–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sorger PK, Stockley PG, Harrison SC. 1986. Structure and assembly of turnip crinkle virus. II. Mechanism of reassembly in vitro. J. Mol. Biol. 191:639–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Speir JA, Munshi S, Wang G, Baker TS, Johnson JE. 1995. Structures of the native and swollen forms of cowpea chlorotic mottle virus determined by X-ray crystallography and cryo-electron microscopy. Structure 3:63–78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sun J, et al. 2007. Core-controlled polymorphism in virus-like particles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:1354–1359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tang J, et al. 2006. The role of subunit hinges and molecular “switches” in the control of viral capsid polymorphism. J. Struct. Biol. 154:59–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. van der Graaf M, Scheek RM, van der Linden CC, Hemminga MA. 1992. Conformation of a pentacosapeptide representing the RNA-binding N terminus of cowpea chlorotic mottle virus coat protein in the presence of oligophosphates: a two-dimensional proton nuclear magnetic resonance and distance geometry study. Biochem. 3:9177–9182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Venter PA, Krishna NK, Schneemann A. 2005. Capsid protein synthesis from replicating RNA directs specific packaging of the genome of a multipartite, positive-strand RNA virus. J. Virol. 79:6239–6248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Verduin BJM, Bancroft JB. 1969. The infectivity of tobacco mosaic virus RNA in coat proteins from spherical viruses. Virology 37:501–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yoffe AM, et al. 2008. Predicting the sizes of large RNA molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:16153–16158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zandi R, van der Schoot P. 2009. Size regulation of ssRNA viruses. Biophys. J. 96:9–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhang W, et al. 2001. Structure of the maize streak virus geminate particle. Virology 279:471–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zlotnick A, Aldrich R, Johnson JM, Ceres P, Young MJ. 2000. Mechanism of capsid assembly for an icosahedral plant virus. Virology 277:450–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]