Abstract

Background

Studies using death certificates have indicated an excess of sudden cardiac deaths among users of antipsychotic drugs compared to the general population, but may have underestimated the presence of other known causes of sudden and unexpected death.

Objectives

To assess the cause and risk factors for sudden death discovered by contemporaneous investigation of all deaths occurring over a 26-year period (1984–2009) in adults receiving care in one large psychiatric hospital in New York.

Methods

Circumstances of death, psychiatric diagnoses, psychotropic drugs and past medical history were extracted from the root cause analyses of sudden unexpected deaths. After the exclusion of suicides, homicides and drug overdoses, explained and unexplained cases were compared regarding clinical variables and the utilization of antipsychotics.

Results

One hundred cases of sudden death were identified among of 119, 500 patient-years. The death remained unexplained in 52 cases. The incidence of unexplained sudden death increased from 7/100,000 (95% CI 3.7–19.4/100,000) in 1984–1998 to 125/100,000 (95% CI 88.9–175.1/100,000) patient-years in 2005–2009. Explained and unexplained cases were similar regarding psychiatric diagnoses and use of all psychotropic classes, including first- and second-generation antipsychotics. Dyslipidemia (p=0.012), diabetes (p=0.055) and co-morbid dyslipidemia and diabetes (p=0.008) were more common in the unexplained group

Conclusions

In a consecutive cohort of psychiatric patients, the unexplained sudden deaths were not associated with higher utilization of first- or second-generation antipsychotics. The role of diabetes and dyslipidemia as risk factors for sudden death in psychiatric patients requires careful longitudinal studies.

Keywords: sudden death, antipsychotic drugs, root cause analysis

In January 2009, the New England Journal of Medicine published data from a retrospective cohort study, demonstrating an increased risk of sudden cardiac death in patients 30–74 years of age treated with antipsychotic drugs (1). The study compared the incidence of sudden cardiac death in a large cohort of users of typical antipsychotics, users of atypical antipsychotics and propensity score-matched nonusers of antipsychotics, all Medicaid enrollees in Tennessee. According to death certificates, during the 1,042,159 person-years of cohort follow up, there were 1,870 (1.79 per thousand person-years) sudden deaths that occurred in the absence of a known, non-cardiac condition as the proximate cause of death. After adjustments for demographic variables and the presence of comorbid somatic conditions, the incidence-rate ratios of sudden cardiac death were 1.99 for users of typical antipsychotics and 2.26 for individuals treated with atypical antipsychotics (1). The study confirmed and expanded previous work by the same group using the death certificates matched to the Tennessee Medicaid database, in which current users of moderate dose antipsychotics (>100 mg thioridazine equivalents) were shown to have a sudden cardiac death ratio of 2.39 compared to nonusers. Among cohort members with detectable cardiovascular disease the rate ratio was 3.53 (2). In a methodologically similar assessment of three state-wide Medicaid programs, patients treated with antipsychotics had a 1.7 to 3.2 incidence-rate ratios of cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmias compared with nonusers, depending on the antipsychotic used (3).

The authors of these epidemiological studies suggested that the excess of sudden cardiac death in patients treated with antipsychotics is due to the effect that these drugs have on myocardial repolarization, evident in their well-established potential for inducing the prolongation of the rate-corrrected QT interval (QTc) on electrocardiogram (4). A prolonged QT is a risk factor for torsade de pointes (TdP), a ventricular arrhythmia that may degenerate into ventricular fibrillation and lead to sudden death (4.5). However, TdP has not been identified in the epidemiological surveys on sudden death in users of antipsychotic drugs.

The findings indicating that typical and atypical antipsychotic use is associated with a similar excess of sudden cardiac deaths (1) have been disputed by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Council on Research in a “Guidance on the Use of Antipsychotic Drugs and Cardiac Sudden Death” (6). The APA Council felt that the use of death certificates may have led to an overestimation of the sudden cardiac death incidence, an underestimation of the cardiovascular morbidity of users of antipsychotic drugs, and to inadequate control for important confounding variables.

Sudden and otherwise unexplained deaths are commonly due to ventricular fibrillation arising as a consequence of coronary artery disease (7). Nonetheless, the determination of the cause of sudden and unexpected death is seldom easy or straightforward. The individual who develops chest pain and who is found to have ischemic changes on the electrocardiogram just before dying en route to the emergency room of the nearest hospital can be safely assumed to have had an acute coronary event. In many other cases, particularly in patients dying alone or in unclear circumstances, the death may remain unexplained even after careful postmortem assessments. This reality, which is more likely to occur in patients with severe mental disorders, is indeed poorly captured in the death certificate (8, 9). A root cause analysis performed by a multidisciplinary team with access to all relevant information is clearly superior for the investigation of unexpected deaths. In fact, compared with a physician-based procedure that used clinical records, autopsy reports and an informant (next-of-kin) interview, the death certificates had a sensitivity of only 24% and a specificity of 85% for the correct classification of cardiovascular and noncardiovascular deaths (9).

In this study, we reviewed the root cause analyses of 100 consecutive cases of sudden death that occurred among the patients receiving care in a single behavioral health institution in New York City and compared the groups with explained and unexplained deaths. We hypothesized that unexplained sudden deaths reflect a high prevalence of major risk factors for coronary artery disease, rather than a greater utilization of antipsychotic drugs.

Methods

Setting and Patient Population

The study was based on information contained in the Special Review Committee reports sent from 1984 to 2009 to the Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry, Zucker Hillside Hospital, a behavioral health component of the North Shore –Long Island Jewish Health System. The hospital is located in the borough of Queens in New York City and comprises a 230-bed acute inpatient facility, outpatient clinics, and day and partial hospital program. The inpatient facility has had an average of 3000 adult admissions/year throughout the period studied, with an average length of stay of approximately 30 days. There have been 3,500 patient “slots” in the adult outpatient programs from 1984 through 1993 and 4,800 registrants from 1994–2009. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board, North Shore – Long Island Jewish Health System, Manhasset, New York.

Data Collection

Beginning in 1977, a Special Review Committee has been investigating all deaths occurring in the inpatient and outpatient programs, including the 30 day period following discharge from these programs. The Committee is chaired by a physician and has as members 3 other physicians and 2 nurses managing the quality improvement activities of the department. All providers are obligated to report the death of any of their patients as soon as possible. The task of the committee is to establish the cause of death by reviewing all available medical records; interviewing the health care providers and family members; obtaining information, when appropriate, from the Emergency Medical Services and the Medical Examiner Office of the City of New York; and arranging for independent expert assessments. A structured report is generated within 120 days of each death. The report contains demographic information, psychiatric diagnoses, past medical history, medication regimen at the time of death, and a description of the terminal event and a statement with regard to the cause of death.

When the events were witnessed, the patients selected for this study had died suddenly and unexpectedly within one hour of symptom onset. If not witnessed, the subjects had been observed alive within 24 hours of their death (10).

The structured root cause analysis of cases of sudden death occurring in patients treated with psychotropic drugs included a careful review of the available electrocardiograms, to establish compliance with hospital policy mandating electrocardiograms for all patients prior to treatment with psychotropic drugs known to prolong the QT interval.

Selection of Cases

Included in this study were all cases of sudden and unexpected deaths in individuals 19–74 years of age which occurred from 1984 through 2009. Excluded were deaths due to trauma, suicide, homicide or intentional or accidental drug overdoses. The contribution of non-prescribed substance use as the cause of death was excluded on the basis of post-mortem toxicological assessments. The cases were entered in the study cohort in reverse chronological order, starting with patients who died in 2009. The 100-case mark was reached in 1984. The total cohort follow-up was estimated to be 119,500 patient years, representing the total number of registrants in outpatient programs and one sixth of inpatient admissions (i.e., accounting for the average length of stay plus 30 days of mandatory follow-up). This estimate assumes that all outpatient “slots” were filled without any interruption. Therefore, the incidence ratios calculated using these estimate are conservative.

Statistical Analyses

Each death was classified as “explained” or “unexplained” based on the conclusion stated in the root cause analysis. We compared the ‘explained” and “unexplained” groups with regard to demographic characteristics, psychiatric diagnoses, psychotropic medications, and past medical history. The significance of the differences in proportions was assessed with the chi-square or Fischer Exact tests, according to the lowest number of cases in the 2 x 2 contingency tables. Logistic regression analyses were also performed with all variables. Since the year of death could be a systematic confounder, we repeated the logistic regression analyses after including the year of death into the model.

Results

Causes of Death

The cause of death was identified in 48 of the 100 cases (Table 1 and Figure 1). The most common explanations of sudden and unexpected death were acute coronary syndromes (15% of the cohort), followed by upper airway obstruction (due to choking on food in 3 cases and to obstructive sleep apnea in 2 patients), pulmonary emboli (4%), and thrombotic strokes (3%). Among the unusual causes were 2 cases of myocarditis (one related to treatment with clozapine); one case of diabetic ketoacidosis in a patient receiving risperidone; a case of septic shock as the presenting symptom of perforated appendicitis; and a case of commotio cordis in a 22-year old patient who was punched with moderate force in the chest. The cause of death remained unknown in 52% of the cohort.

Table 1.

Causes of Sudden Death

| Cause of Sudden Death | Total (N=100) |

|---|---|

| Cardiovascular Diseases | 22 |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 15 |

| Heart failure | 2 |

| Aortic dissection | 2 |

| Myocarditis | 2 |

| Commotio cordis | 1 |

| Gas-Exchange Failure | 17 |

| Upper Airway Obstruction | 5 |

| Pulmonary embolus | 4 |

| Bronchial asthma | 2 |

| Pneumonia | 2 |

| Respiratory failure NOSa | 4 |

| Intracranial Event | 5 |

| Thrombotic stroke | 3 |

| Brain hemorrhage | 2 |

| Diabetic Ketoacidosis | 1 |

| Septic Shock | 1 |

| Seizure | 1 |

| Gastrointestinal Bleeding | 1 |

| Unknown | 52 |

=not otherwise specified

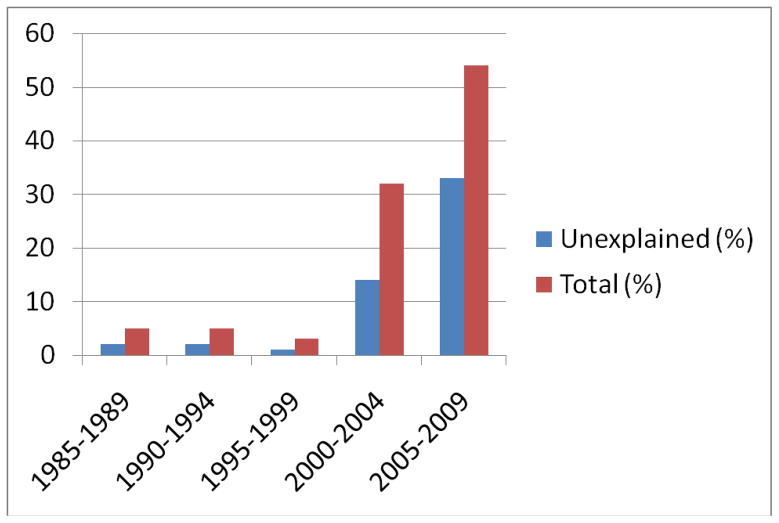

Figure 1.

Chronological Distribution of Sudden Deaths (% of 100-Case Cohort/5-year interval)

Psychiatric Characteristics

The “explained” and “unexplained” groups were similar with respect to age, sex, primary psychiatric diagnoses and all medication classes, including first- and second-generation antipsychotics (Table 2). Prescriptions for quetiapine (p=0.002) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI) (p=0.012), were more prevalent in the group with “unexplained” sudden death. The most commonly used SNRI in this group was venlafaxine (9 of 10 cases).

Table 2.

Demographic and Psychiatric Characteristics

| Characteristic | Total (N=100) | Explained (N=48) | Unexplained (N=52) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years ± SD) | 49.4 ± 12.1 | 49.0 ± 12.7 | 49.7 ± 13.0 | NS |

| Sex | ||||

| Male (%) | 62 (62.0) | 31 (64.6) | 31 (59.6) | NS |

| Female (%) | 38 (38.0) | 17 (35.4) | 21 (40.4) | NS |

| Primary Psychiatric Diagnosesa | ||||

| Psychotic Disorders (%) | 33 (34.0) | 17( 37.8) | 16 (30.8) | NS |

| Schizophrenia (%) | 27 (27.8) | 14 (31.1) | 13 (25.0) | NS |

| Psychosis NOSb (%) | 6 (6.2) | 3 (6.3) | 3 (5.8) | NS |

| Mood Disorders (%) | 46 (47.4) | 21 (36.6) | 25 (48.1) | NS |

| Bipolar Disorder (%) | 18 (18.6) | 10 (22.2) | 8 (15.4) | NS |

| Major Depression (%) | 19 (19.6) | 5 (11,1) | 14 (26.9) | NS |

| Depression NOSb (%) | 9 (9.3) | 6 (13.3) | 3 (5.8) | NS |

| Anxiety Disorders (%) | 5 (5.2) | 3 (6.3) | 2 (3.8) | NS |

| Substance Use Disorders (%) | 9 (9.3) | 2 (4.4) | 7 (13.5) | NS |

| Other (%) | 4 (4.1) | 2 (4.4) | 2 (3.8) | NS |

| Psychotropic Treatment | ||||

| First Generation Antipsychotics (%) | 9 (9.0) | 5 (10.4) | 4 (7.7) | NS |

| Second Generation Antipsychotics (%) | 40 (41.0) | 17 (35.4) | 23 (44.2) | NS |

| Clozapine (%) | 9 (9.0) | 4 (8.3) | 5 (9.6) | NS |

| Olanzapine (%) | 8 (8.0) | 6 (12.5) | 2 (3.8) | NS |

| Quetiapine (%) | 11 (11.0) | 0 (0.0) | 11 (21.2) | 0.002 |

| Risperidone (%) | 9 (9.0) | 5 (10.4) | 4 (7.7) | NS |

| Aripiprazole (%) | 2 (2.0) | 2 (4.2) | 0 (0.0) | NS |

| Ziprasidone (%) | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) | NS |

| Antidepressants (%) | 33 (33.0) | 13 (27.1) | 20 (38.5) | NS |

| SSRIc (%) | 19 (19.0) | 8 (16.7) | 11 (21.2) | NS |

| SNRId (%) | 11 (11.0) | 1 (3.1) | 10 (19.2) | 0.012 |

| Tricyclics | 5 (5.0) | 2 (4.2) | 3 (5.8) | NS |

| Mirtazapine (%) | 5 (5.0)) | 1 (3.1) | 4 (7.7) | NS |

| Mood Stabilizers (%) | 16 (16.0) | 7 (14.6) | 9 (17.3) | NS |

| Lithium (%) | 6 (6.0) | 4 (8.3) | 2 (3.8) | NS |

| Valproate (%) | 6 (6.0) | 3 (6.3) | 3 (5.8) | NS |

| Gabapentine (%) | 4 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (7.7) | NS |

| Lamotrigine (%) | 3 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (5.8) | NS |

| Benzodiazepines (%) | 9 (9.0) | 3 (6.3) | 6 (11.6) | NS |

| Methadone (%) | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.8) | NS |

| Psychostimulants (%) | 3 (3.0) | 1 (3.1) | 2 (3.8) | NS |

=Diagnostic data missing for 3 patients from the Explained group;

=Not otherwise specified;

=selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors;

=serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors

Past Medical History

Compared with the group of explained sudden death cases, significantly more subjects from the unexplained sudden death group had a history of dyslipidemia (36.5% vs 14.6%, p=0.012) (Table 3). The comorbid associations of dyslipidemia with diabetes (19.2% vs 2.1%, P=0.006) was also significantly more common in the unexplained sudden death group. In addition, diabetes was more than twice as common in the group with explained sudden death (30.8% vs 14.6%, P=0.054).

Table 3.

Past Medical History

| Characteristic (%) | Total (N=100) | Explained (N=48) | Unexplained (N=52) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular Diseases | ||||

| Coronary Artery Disease | 13 (13.0) | 5 (10.4) | 8 (15.4) | NS |

| Arterial Hypertension | 35 (35.0) | 15 (31.3) | 20 (38.5) | NS |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 4 (4.0) | 3 (6.3) | 1 (1.9) | NS |

| Other Cardiovascular Diseases | 5 (5.0) | 1 (2.1) | 4 (7.7) | NS |

| Metabolic Disorders | ||||

| Dyslipidemia | 26 (26.0) | 7 (14.6) | 19 (36.5) | 0.012 |

| Diabetes | 23 (23.0) | 7 (14.6) | 16 (30.8) | 0.054 |

| Diabetes and Dyslipidemia | 11 (11.0) | 1(2.1) | 10 19.2) | 0.006 |

| Hypertension and Dyslipidemia | 17 (17.0) | 5 (10.4) | 12 (23.1) | NS |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.8) | NS |

| Bronchial Asthma or COPDb | 7 (7.0) | 3 (6.3) | 4 (7.7) | NS |

| Obstructive Sleep Apnea | 2 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.8) | NS |

=Coronary artery disease, diabetes, ischemic cerebrovascular events, peripheral arterial insufficiency;

=Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Chronological Distribution of Sudden and Unexpected Deaths

The 5-year interval 2005–2009 had 54 cases of sudden death, of which 33 (61.1%) were unexplained (mean age: 50.9±11.8 years) (Figure 2). In the preceding 5-year interval (1999–2004), there were 32 sudden deaths, of which 14 (43.8%) were unexplained (mean age: 50.7±13.4 years). In contrast, there were only 13 deaths cases of sudden death, of which 5 (38.5%) were unexplained (mean age: 41.2 ±19.3 years) in the entire preceding 15-year period from 1984 through 1998 (Figure 2). The incidence of unexplained sudden death was 125/100,000 (95% CI 88.9–175.1/100,000) patient-years in 2005–2009, 53/100,000 (95% CI 31.7–88.5/100,000) patient-years in 1999–2004 and 7/100,000 (95% CI 3.7–19.4/100,000) patient-years in 1984–1998.

Logistic regression

In the logistic regression analysis, only the co-morbid presence of dyslipidemia and diabetes (OR:11.19, 95% confidence interval 1.37–91.14, p=0.024) remained independently associated with unexplained cause of sudden death.

Discussion

Sudden death may occur as the outcome of many life events or pathological processes, including post-traumatic injury of vital organs, accidental or intentional poisoning, and upper airway obstruction with foreign bodies or laryngeal spasm or edema. Most non-traumatic and otherwise unexplained sudden deaths are due to ventricular fibrillation. These arrhythmogenic sudden cardiac deaths are produced by structural or functional abnormalities of the heart (Table 4). Ample autopsy data indicate that active coronary lesions are observed in up to 80% of sudden cardiac death victims (7). Other structural cardiac disorders that may end in sudden cardiac death are distinctly less common. Dilated cardiomyopathies, a chronic heart muscle disease characterized by left ventricular dilatation and impairment of systolic function accounts at most for 7% of sudden cardiac deaths (7, 11). Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (an inherited disorder of genes encoding sarcomeric proteins) and the right ventricular cardiomyopathy (due to fibro-fatty replacement of the right ventricular myocardium) explain 4% of arrhythmogenic sudden deaths in the general population (7, 12). In a small minority of adults, the arrhythmogenic sudden cardiac deaths may occur in persons whose hearts have no detectable lesions on routine autopsies. The root cause of these deaths can be traced to abnormal myocardial repolarization (congenital or acquired QT prolongation and Brugada syndrome), atrioventricular preexcitation (Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome), abnormal response to stress (catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia) or to idiopathic ventricular tachycardia (7).

Table 4.

Causes of Arrhythmogenic Sudden Cardiac Death

| Structural Abnormalities |

| Coronary artery disease |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy |

| Right ventricular cardiomyopathy |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy |

| Aortic stenosis |

| Mitral valve prolapse |

| Myocarditis |

| Anomalous origin of coronary arteries |

| Myocardial bridging |

| Functional Abnormalities |

| Long QT syndrome |

| Brugada syndrome |

| Pre-excitation syndromes |

| Catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia |

| Atrio-ventricular conduction abnormalities |

Our study used structured root cause analysis of death and indicated that the incidence of sudden and unexpected deaths among psychiatric patients has increased greatly in the first decade of the 21st century. Slightly less than half of these cases (48%) had a defined cause of death, with acute coronary syndromes being by far the most common. The unexplained cases demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of dyslipidemia and its co-morbid associations with diabetes. This correlation must be confirmed by large longitudinal studies, but the signal registered by our study should strengthen efforts to understand the relationship between these metabolic abnormalities and genetic predispositions specific to persons suffering from severe menal illnesses in the global context of rapidly increased prevalence of obesity and diabetes. Dyslipidemia is the primary risk factor for coronary events, i.e., myocardial infarction and sudden death (13). Diabetes is associated with increased risk of sudden death, a complication related mostly to its role in determining the severity of coronary atherosclerosis (macrovascular effect). Microvascular complications of diabetes, such as microalbuminuria and retinopathy, are also strong independent correlates of sudden death (14). The presence of patchy areas of myocardial fibrosis in patients with evidence of microvascular complications of diabetes may explain their ncreased risk for lethal ventricular arrhythmias (14). In the Atherosclerosis Risk in Community (ARIC) study, the proportional hazard ratio of the association of baseline diabetes with sudden death over an average follow-up period of 12.4 years was 3.77, independent of blood pressure, lipids, inflammation, hemostasis and renal function (15). Finally, the comorbid associations between dyslipidemia, diabetes and arterial hypertension likely reflect the presence of metabolic syndrome, a plurifactorial risk factor that is known to double the 10-year probability of coronary events in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics (16).

In univariate analyses, our study identified a higher use of quetiapine and venlafaxine in the group of patient with unexplained sudden death. We could not find published clinical reports of sudden deaths in patients receiving quetiapine in approved dosages. In post-marketing surveillance, cardiovascular disorders have been identified as the most common cause of death (31.2% of all deaths) in patients treated with quetiapine (17), but there is no indication that quetiapine is more dangerous than other second-generation antipsychotics, as shown in the study comparing users and nonusers of antipsychotic drugs, where the incidence-rate ratio of sudden cardiac death was 1.88 for quetiapine, 2.04 for olanzapine, 2.91 for risperidone and 3.67 for clozapine (1). With regard to venlafaxine, the adjusted odds ratio of sudden cardiac death or near death associated with this antidepressant was 0.66 relative to fluoxetine and 0.89 compared to citalopram use (18). As most cases of unexplained sudden death occurred in the past 10 years, it is possible that the frequent use of venlafaxine and quetiapine in this group reflects the increased utilization of these drugs among patients with severe psychiatric disorders ( 18, 19).

Similar to other studies of sudden death in psychiatric patients (1–3), the interpretation of our findings is limited by lack of data with regard to changes in body mass index and QT intervals prior to sudden death, and the quality of medical care received by these psychiatric patients. Other limitations include a relatively small sample size and the fact that although all deaths had been referred to the Office of the Medical Examiner, a complete autopsy was performed in only 18 of the 100 cases.

The findings provide preliminary evidence that unexplained sudden deaths of psychiatric patients are likely due to coronary events. We found no evidence to support the antipsychotic-induced QT prolongation, leading to TdP and ventricular fibrillation, as a cause of death. Although larger studies are clearly required to confirm and expand our findings, we feel confident that our results suggests that psychiatric providers must intensify the identification and adequate treatment of dyslipidemia, diabetes and arterial hypertension for all of their patients. From this standpoint, a number of recent studies that have shown disconcertingly low adherence rates to generally accepted cardiometabolic monitoring guidelines of patients treated with antipsychotics (20–23). We think that the field is in urgent need to develop education programs and campaigns that increase the monitoring to the desired and required levels. In addition, system and individual provider level interventions are needed to improve the medical care in mentally ill patients with identified medical problems (24–27). Importantly, our study results suggests that adequate monitoring and management of cardiometabolic risk factors will likely not only reduce morbidity and mortality directly related to cardiovascular disorders, but will also decrease sudden cardiac death risk.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Supported in parts by The Zucker Hillside Hospital National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Advanced Center for Intervention and Services Research for the Study of Schizophrenia MH 074543-01 (Dr. Kane).

Footnotes

Disclosures: Dr. Manu has served on the speaker/advisory boards of Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb and Forest. Dr. Kane has been a consultant to Astra-Zeneca, Janssen, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dainippon Sumitomo, Otsuka, Vanda, Proteus, Takeda, Targacept, Intracellular Therapeutics, Rules Based Medicine and has received honoraria for lectures from Otsuka, Eli Lilly, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Janssen. Dr. Correll has been a consultant and/or advisor to or has received honoraria from: Actelion, AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boeringer-Ingelheim, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, Ortho-McNeill/Janssen/J&J, GSK, Hoffmann-La Roche, Medicure, Otsuka, Pfizer, Schering-Plough, Supernus, Takeda and Vanda.

References

- 1.Ray WA, Chung CP, Murray KT, et al. Atypical antipsychotic drugs and the risk of sudden cardiac death. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:225–235. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray WA, Meredith S, Thapa PB, et al. Antipsychotics and the risk of sudden cardiac death. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:1161–1167. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.12.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hennessy S, Bilker WB, Knauss JS, et al. Cardiac arrest and ventricular arrhythmia in patients taking antipsychotic drugs: cohort study using administrative data. BMJ. 2002;325:1070–1075. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7372.1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haddad PM, Anderson IM. Antipsychotic-related QTc prolongation, torsade de pointes and sudden death. Drugs. 2002;62:1649–1671. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200262110-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kannankeril PJ, Roden DM. Drug-induced long QT and torsade de pointes: recent advances. Curr Opin Cardiology. 2007;22:39–43. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32801129eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lieberman JA, Merrill D, Parameswaran S for the APA Council on Research. [accessed April 4, 2010];APA guidance on the use of antipsychotic drugs and cardiac sudden death. http://www.omh.state.ny.us/omhweb/advisories/adult_antipsychotic_use_attachment.html.

- 7.Priori SG, Aliot E, Blomastrom-Lundqvist L, et al. Task Force on sudden cardiac death of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1374–1450. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Every NR, Parsons L, Hlatsky MA, et al. use and accuracy of state death certificates for classification of sudden cardiac deaths in high-risk populations. Am heart J. 1997;134:1129–1132. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(97)70035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iribarren C, Crow RS, Hannan PJ, et al. validation of death certificate diagnosis of out-of-hosppital sudden cardiac death. Am J Cardiology. 1998;82:50–53. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00240-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chugh SS, Reinier K, Teodorescu C, et al. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death: Clinical and research implications. Prog cardiovasc Dis. 2008;51:213–228. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Lenarda A, Secoli G, Perkan A, et al. Changing mortality in dilated cardiomyopathy. The Heart Muscle Disease Study Group. Br Heart J. 1994;72:S46–S512. doi: 10.1136/hrt.72.6_suppl.s46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen WK, Edwards WD, Hammill SC, et al. Sudden unexpected nontraumatic deathin 54 young adults: a 30-year population-based study. Am J Cardiol. 1995;76:148–152. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grundy SM. United States Cholesterol Guidelines 2001: expanded scope of intensive low-density lipoprotein-lowering therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:23J–27J. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01931-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siscovick DS, Sotoodehnia N, Rea TD, et al. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and the risk of sudden cardiac arrest in the community. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2010;11:53–59. doi: 10.1007/s11154-010-9133-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kucharska-Newton AM, Couper DJ, Pankow JS, et al. Diabetes and risk of sudden cardiac death, the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Acta Diabetol. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00592-009-0157-9. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Correll CU, Frederickson AM, Kane JM, Manu P. Metabolic syndrome and risk of coronary heart disease in 367 patients treated with second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2006;60:575–583. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Twaites BR, Wilton LV, Shakir SAW. The safety of quetiapine: results of a post-marketing surveillance study on 1728 patients in England. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21:392–399. doi: 10.1177/0269881107073257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martinez C, Assimes TI, Mines D, et al. Use of venlafaxine compared with other antidepressants and the risk of sudden cardiac death or near death: a nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c249. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Komassa K, Rummel-Kluge C, Schmid F, et al. Quetiapine versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD006625. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006625.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnes TR, Paton C, Cavanagh M-R, et al. An UK audit of screening for the metabolic side effects of antipsychotics in community patients. Schizophrenia Bull. 2007;33:1397–403. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrato EH, Newcomer JW, Kamat S, et al. Metabolic screening after the American Diabetes Association’s consensus statement on antipsychotic drugs and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(6):1037–42. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haupt DW, Rosenblatt LC, Kim E, et al. Prevalence and predictors of lipid and glucose monitoring in commercially insured patients treated with second-generation antipsychotic agents. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(3):345–53. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrato EH, Druss B, Hartung DM, et al. Metabolic testing rates in 3 state Medicaid programs after FDA warnings and ADA/APA recommendations for second-generation antipsychotic drugs. Arch GenPsychiatry. 2010 Jan;67(1):17–24. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, et al. Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(6):565–572. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.6.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frye RL. Optimal care of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 2003;115(suppl 8A):93S–98S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nasrallah HA, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Low rates of treatment for hypertension, dyslipidemia and diabetes in schizophrenia: data from the CATIE schizophrenia trial sample at baseline. Schizophr Res. 2006;86(1–3):15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Correll CU, Kane JM, Manu P. Identification of high-risk coronary heart disease patients receiving atypical antipsychotics: Single low-density lipoprotein cholesterol threshold or complex national standard? Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:578–583. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]