Abstract

A potential application of embryonic and inducible pluripotent stem cells for the therapy of degenerative diseases involves pure somatic cells, free of tumorigenic undifferentiated embryonic and inducible pluripotent stem cells. In complex collections of chemicals with pharmacological potential we expect to find molecules able to induce specific pluripotent stem cell death, which could be used in some cell therapy settings to eliminate undifferentiated cells. Therefore, we have screened a chemical library of 1120 small chemicals to identify compounds that induce specifically apoptotic cell death in undifferentiated mouse embryonic stem cells (ESCs). Interestingly, three compounds currently used as clinically approved drugs, nortriptyline, benzethonium chloride and methylbenzethonium chloride, induced differential effects in cell viability in ESCs versus mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs). Nortriptyline induced apoptotic cell death in MEFs but not in ESCs, whereas benzethonium and methylbenzethonium chloride showed the opposite effect. Nortriptyline, a tricyclic antidepressant, has also been described as a potent inhibitor of mitochondrial permeability transition, one of two major mechanisms involved in mitochondrial membrane permeabilization during apoptosis. Benzethonium chloride and methylbenzethonium chloride are quaternary ammonium salts used as antimicrobial agents with broad spectrum and have also been described as anticancer agents. A similar effect of benzethonium chloride was observed in human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) when compared to both primary human skin fibroblasts and an established human fibroblast cell line. Human fibroblasts and hiPSCs were similarly resistant to nortriptyline, although with a different behavior. Our results indicate differential sensitivity of ESCs, hiPSCs and fibroblasts to certain chemical compounds, which might have important applications in the stem cell-based therapy by eliminating undifferentiated pluripotent stem cells from stem cell-derived somatic cells to prevent tumor formation after transplantation for therapy of degenerative diseases.

Keywords: Embryonic stem cells, Induced pluripotent stem cells, Fibroblasts, Chemical screening, Small molecules, Apoptosis, Teratoma, Nortriptyline, Benzethonium

Introduction

Stem cell research has gained much attention in recent years, due to the therapeutic applications emerging from stem cells. A major field of stem cell research is related to their targeted differentiation in order to obtain specific somatic cell types that could be used to replace damaged tissues [1]. Cell replacement therapy has produced promising results in preliminary tests using different disease models, and might be used to cure several disorders in the near future, such as neurodegenerative diseases [2, 3], myocardial infarction-derived tissue damage [4, 5] or even diabetes [6]. Specific stem cell differentiation can be achieved by different methods [7, 8]. A field of research that has achieved importance lately is chemical genetics [9], which consists on the use of chemical compounds to alter protein activity, allowing the functional characterization of the biological targets of chemicals. Two major approaches within this field are forward chemical genetics, in which desired phenotypic changes are analyzed upon treatment of cells or whole organisms with chemicals, and reverse chemical genetics, in which chemicals that modify the activity of a given protein are first identified in vitro and later used in cells or organisms to determine their phenotypic effect [10].

In stem cell research, chemical compounds are being used to direct differentiation of stem cells to specific somatic cell types [11]. On one side, this type of experiments can be used to obtain specific cell types for different applications, such as cell replacement therapy; on the other side, they constitute a powerful tool to identify the genes and signaling pathways involved in specific differentiation programs.

A major problem that has arisen during targeted differentiation of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) is the differentiation to unwanted cell types or even the uncontrolled proliferation of undifferentiated or partially differentiated cells, giving rise to teratocarcinomas [12, 13]. The identification of novel chemicals that induce specific stem cell differentiation is therefore of utmost importance. Conversely, identification of compounds that display specific toxicity towards stem cell versus differentiated cells or vice versa is also very interesting. Such compounds could be used for the elimination of undifferentiated stem cells when specific somatic cells are desired. On the other hand, the identification of compounds with specific toxicity against differentiated cells but not to stem cells could be used for the isolation of stem cells from different tissues.

The objective of the work we present here has been to identify chemicals, from complex collections of small molecules with pharmacological potential, able to induce specific cell death in pluripotent stem cells versus differentiated cells, or vice versa. With this aim in mind, we have screened a chemical library of 1120 chemicals to identify chemicals that specifically induce death of undifferentiated ESCs. Among those, of special interest were chemicals that induced cell death by apoptosis in order to investigate whether apoptotic pathways are differentially regulated in ESCs versus non-ESCs (MEFs or Bax/Bak double knockout MEFs). Moreover, apoptosis-inducing compounds with cell-type specificity could be used to silently eliminate unwanted cell types in targeted differentiation approaches either in vitro or in vivo. During our screening we identified nortriptyline as a chemical that, at certain doses, induced apoptotic cell death in MEFs but not in ESCs or in Bax/Bak double knockout MEFs, indicating an interesting similarity between ESCs and Bax/Bak double knockout MEFs with respect to apoptosis resistance. Much more important, we also identified two related compounds, benzethonium chloride and methylbenzethonium chloride with the opposite effect, they induced apoptosis at certain concentrations in ESCs but not in MEFs. Benzethonium chloride was also tested in human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) and two different types of human fibroblasts, displaying also selective toxicity against hiPSCs cells at certain concentrations.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

Mouse CGR8 embryonic stem cells (ESCs), adapted to grow in the absence of feeder cells, have been previously described [14]. They were cultured at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, in Glasgow Minimum Essential Medium (GMEM, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS, Invitrogen), 100 units/ml leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF, Chemicon), 50 μM β-mercaptoethanol (Invitrogen) and 100 U/ml of penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen) in 0.2% gelatin (Sigma) coated flasks.

hiPSC line IMR90-C4 (WiCell, Madison, WI, USA) was grown under serum free, feeder free conditions using mTeSR media (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver BC, Canada) supplemented with 100 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) onto BD Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Palo Alto, CA, USA) coated dishes. When the cells reached around 70% confluency, single cells were obtained by trypsinisation and later 10,000 cells were plated per well of a 96-well plate in the presence of 10 μM Y-27632 (ROCK inhibitor) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) to prevent single cells from undergoing anoikis. The cells were washed 24 h post plating and grown for another 24 h in the absence of Y-27632 to get rid of any intracellular residual Y-27632. 48 h post plating, the cells were either untreated or treated in triplicates with chemical compounds, for 48 h.

SV40-transformed mouse embryonic fibroblasts (referred to as MEFs throughout the text) were kindly shared by Dr. Julián Pardo (Department of Biochemistry and Molecular and Cellular Biology, University of Zaragoza, and Fundación Aragón I+D (ARAID)). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml of penicillin/streptomycin and 2 mM glutamine (Invitrogen).

Wild type, untransformed, MEFs (referred to as wtMEFs in the text) were kindly provided by Dr. Manuel Serrano (CNIO, Madrid), and SV-40 transformed Bax-/Bak- double knockout MEFs (referred to as DKO-MEFs) were kindly provided by Dr. Cristina Muñoz-Pinedo (IDIBELL, L’Hospitalet, Barcelona) and have been previously described [15] and were cultured as SV40-transformed MEFs.

Primary adult human skin fibroblasts (MXDJ) and HFF-1 fibroblast cell line (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) were cultured in DMEM media supplemented with 10% FCS and 2 mM L-glutamine (all from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Chemical Library

The compound library used for this study was the Prestwick Chemical Library (Prestwick Chemical, Illkirch, France), which contains 1120 small molecules, all of them being marketed drugs. The active compounds of this library were selected for their high chemical and pharmacological diversity as well as for their known bioavailability and safety in humans.

Initial Screening

To carry out the screening, murine ESCs grown in 25 cm2 flasks coated with gelatin were trypsinized, washed with wash medium (GMEM with 5% FBS), and plated on gelatin-coated 96-well plates at a density of 10,000 cells per well in culture medium. After overnight incubation, medium was replaced by fresh medium. Since the concentration of stock compounds in the chemical library was 5 mM (in dimethylsulfoxide, DMSO), intermediate plates were prepared containing three or four compounds per well diluted 1/10 in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) pH 7.4 (Invitrogen). 2 μl of this intermediate solution were added to 100 μl of medium to achieve a final concentration of 10 μM per compound, and a final DMSO concentration of 0.6 or 0.8% in wells containing three or four compounds, respectively. The same final concentration of DMSO without compounds was used as negative control. Camptothecin, which inhibits the DNA enzyme topoisomerase I, was used as positive control of cell death at a concentration of 10 μM. The blank was prepared with culture medium without cells.

ESCs were incubated with chemical compounds or controls for 48 h. Then, a colorimetric assay was used to measure cell viability.

XTT Colorimetric Assay

The Cell Proliferation Kit II (XTT) (Roche) was used to measure cell viability. The assay is based on the cleavage by metabolic active cells of the yellow tetrazolium salt XTT (2,3-bis[Methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl]-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide) to form an orange formazan dye. Cells were incubated for 4 h. with kit reagents as recommended by the manufacturer and then absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a Synergy HT multi-mode micro plate reader (BioTek), using a reference wavelength of 650 nm. For human iPS cells and fibroblasts, readings were taken at 480 and 655 nm using a Bio-Rad 3550 microplate reader. Sets of compounds reducing cell viability were selected for further screening.

Secondary Screening

The secondary screening was performed as described for the primary screening, but using one compound per well, at a final concentration of 10 μM and 0.2% DMSO.

In this step, we also treated SV40-transformed mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) with the same compounds, in order to identify those with differential effects on both cell types. MEFs were seeded at 2500 cells/well, since they grow faster than ESCs.

Vital Staining

ESCs and MEFs were cultured and treated with compounds as for the XTT assay. Culture media and floating cells were transferred to a microtube, attached cells were trypsinized and transferred to the same tube. An aliquot of this cell suspension was diluted (1:1) with a solution of the vital dye trypan blue (0.4% in PBS) and live (unstained) and dead (blue) cells were counted using a Neubauer chamber. Three biological independent replicates were analyzed with DMSO (negative control), camptothecin (CPT) and compounds 26D, 199A and 223A and two replicates with compounds 23B, 45B, 92B and 219C. In each individual replicate cells were placed on the two sides of the Neubauer chamber and cells in four quadrants on each side were counted. For most cells, this was done twice (i.e, 16 quadrants counted). Number of cells per quadrant varied between averages of 20 (for compounds and controls that kill cells) and 50 (for compounds and controls which did not kill cells).

Dose/Response Studies

Dose/response studies of selected compounds were carried out using dilutions ranging from 0.1 to 100 μM, under the same conditions described above, except for hiPSCs and fibroblasts, with which concentrations ranging from 2.5 to 40 μM were used.

Caspase Inhibition Assays

Cells were cultured under the conditions described above and treated with 100 μM z-VAD-fmk (pan-caspase inhibitor) in DMSO or DMSO alone (negative control) 30 min before adding the compounds, and then incubated for 48 h. In order to determine the moment of highest inhibition of cell death by caspase inactivation, this assay was also performed at different times of incubation with the compounds: 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h.

Caspase 3 and 7 Activity

Caspase 3 and 7 activity was measured by a colorimetric assay that is based on the hydrolysis of acetyl-Asp-Glu-Val-Asp p-nitroanilide (Ac-DEVD-pNA, Sigma) by caspases 3 and 7, resulting in the release of the p-nitroaniline (pNA). p-Nitroaniline is detected measuring absorbance at 405 nm (εmM=10.5).

ESCs and MEFs were seeded at 40000 and 5000 cells per well, respectively, on a 96-well plate. DMSO vehicle alone, 10 μM camptothecin or 10 μM compound were added to the cells and incubated for 12 h. Cells were then lysed with 100 μl lysis buffer (1 % Triton X100, 100 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA) and 1/2 serial dilutions were made with reaction buffer (100 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 20 % glycerol, 20 mM DTT, 0.5 mM EDTA). 100 μl of reaction buffer containing Ac-DEVD-pNA at 400 μM was added to each well (final concentration of Ac-DEVD-pNA, 200 μM). Absorbance at 405 nm was measured after incubating the plate at 37°C for 0 min, 30 min, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h and overnight.

Morphologic Assessment of Apoptosis

ESCs and MEFs were seeded in 24-well plates at a concentration of 150000 and 25000 cells per well, respectively. After overnight incubation, medium was replaced with fresh medium and camptothecin, compounds 26D and 223A at a concentration of 10 μM were added. The same amount of DMSO included with the compounds was used as negative control. After 24 h of incubation with the compounds, cells were incubated with 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) for 15 min at room temperature. Cells were visualized and photographed (400X magnification) directly on the culture plates without further processing, using an inverted fluorescence microscope with the appropriate filter. Two biological independent experiments were carried out in duplicates, counting three fields in each sample. Nuclei were scored as apoptotic when their chromatin was clearly condensed and/or fragmented with respect to the round nuclei of healthy cells (cells suspected to be undergoing mitosis were scored as healthy). A minimum of 28 cells (MEFs treated with nortriptyline) and a maximum of 250 cells (CGR8 treated with DMSO or with nortriptyline) were scored in each field.

Statistical Analyses

Each experiment, unless indicated otherwise, was performed in three biological independent replicates with appropriate technical replicates for each sample for the final read out. Values were normalized to the control in each experiment. The mean values of technical replicates were used to calculate the mean, standard deviation and statistical t-test values among biological independent replicates using the GraphPad Prism 4 software (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA, USA).

Results

Initial Screening

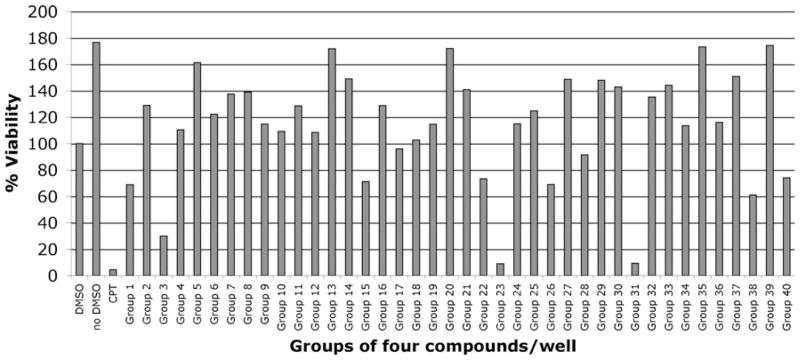

In order to identify chemical compounds that altered the viability of ESCs, we treated cells in 96-well plates with compounds in groups of three or four at a final concentration of 10 μM. Positive controls contained 10 μM camptothecin and negative controls, DMSO in PBS. Cells were incubated with compounds for 48 h and analyzed using the XTT assay. Figure 1 shows the results obtained with 40 groups of four compounds. 37 groups of four compounds and 12 groups of three compounds decreased cell viability, whereas 12 groups of four compounds and 12 groups or three compounds increased cell viability, according to the XTT assay. We proceeded with further analysis of compounds that decreased cell viability.

Fig. 1.

Primary screening. Results of XTT assays carried out with 40 groups of four compounds on ESCs, at a final concentration of 10 μM for 48 h. Camptothecin (CPT) at 10 μM was used as positive control. DMSO alone was used as negative control (100% viability)

Secondary Screening

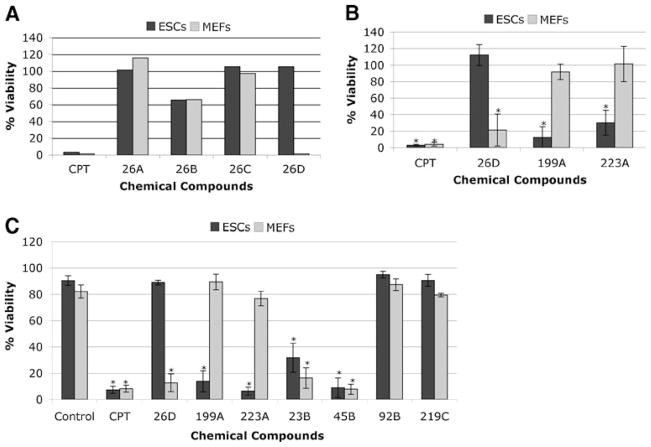

The four or three compounds present in wells with decreased cell viability were analyzed individually using the XTT assay under the conditions described above. At this step, since we were interested on compounds with specific effects on stem cells, we included MEFs to select compounds with different effects on both types of cells. Figure 2a shows the results of one of these deconvolution assays, corresponding to group 26, which contained four compounds, referred to as 26A to 26D. In this particular case, compound 26B was responsible for the decreased cell viability observed with this group (excluding possible additive or synergistic effects of different compounds), with similar effects in ESCs and MEFs. Interestingly, compound D from group 26 had a strong negative effect on the viability of MEFs without affecting ESCs. We also found compounds with the opposite effect, as shown in Fig. 2b, where the effect of compound 26D is shown together with the effects of compounds 199A and 223A, which decreased ESCs viability without significantly altering the viability of MEFs.

Fig. 2.

Secondary screening. a Example of a screening of individual compounds from one group (group 26, compounds A, B, C and D) using ESCs (black bars) and MEFs (grey bars). Each compound was used at a final concentration of 10 μM and cells incubated for 48 h. Camptothecin (CPT) was used as positive control and DMSO as negative control (100% viability). b Differential effect of three compounds on ESCs (black bars) and MEFs (grey bars). Assays were carried out as in A. The mean±SD (standard deviation) of three independent experiments (n=3), each of them carried out with triplicates, are shown. c Cell viability determined by trypan blue staining. ESCs (black bars) and MEFs (grey bars) were treated individually with seven different compounds at 10 μM for 48 h, trypsinized, mixed with a trypan blue solution and counted using a Neubauer chamber. Viability is shown as the percentage of unstained cells with respect to total cells. Values represent the mean±SD of three (control, CPT, 26D, 199A and 223A) or two (23B, 45B, 92B and 219C) independent experiments, each carried out with duplicates. *, significant difference for p<0.05 with respect to the DMSO control

In order to confirm that the effect monitored with the XTT assay was due to cell death and not due to cell cycle arrest, we used trypan blue staining to differentiate dead (blue) from live (unstained) cells. As demonstrated in Fig. 2c, the effects on cell viability observed with compounds 26D, 199A and 223A were due to cell death.

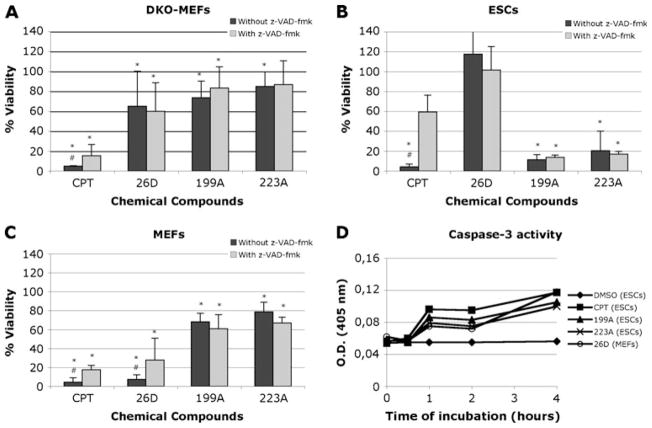

Analysis of the Mode of Cell Death

Since we were especially interested in compounds that cause death by apoptosis, we carried out further analyses with the XTT assay using Bax/Bak double knockout MEFs (DKO-MEFs) and z-VAD-fmk, a caspase inhibitor. DKO-MEFs were quite resistant to incubation with compounds 26D, 199A and 223A, suggesting that they were inducing death by apoptosis (Fig. 3a). Markedly, compound 26D induced death in MEFs but not in ESCs, and DKO-MEFs were quite resistant to compound 26D.

Fig. 3.

Role of caspases in cell death. Double knockout (DKO) MEFS (a), ESCs (b) and wild type MEFs (c) were treated with compounds 26A, 199A or 223A in the absence (black bars) or presence (grey bars) of 100 μM z-VAD-fmk. The results of XTT assays are presented as the mean±SD of three independent experiments, each carried out with triplicates. d Determination of caspase 3 and 7 activity. ESCs and MEFs were incubated for 12 h with each compound, with camptothecin or with DMSO. Ac-DEVD-pNA was then added to the cultures and incubated for 0 min, 30 min, 2 h and 4 h, measuring absorbance at 405 nm as described in materials and methods. *, significant difference for p<0.05 with respect to the DMSO control. #, significant difference for p<0.05 with respect to the sample in presence of z-VAD-fmk

We also incubated all three cell lines with the compounds in the presence or absence of z-VAD-fmk, (Fig. 3a, b, c). Z-VAD-fmk did not affect viability of ESCs treated with compounds 199A and 223A (Fig. 3b), and as expected had no effect on those treated with compound 26D. This suggests that caspase-dependent apoptosis is not involved in death caused by compounds 199A and 223A. Z-VAD-fmk did not alter the effect of compounds 199A and 223A on MEFs, but partially prevented cell death induced by compound 26D (Fig. 3c). Although cell viability was not completely recovered by inhibiting caspases, a similar partial recovery was observed with cells treated with camptothecin, a known apoptosis inducer through DNA damage, suggesting that compound 26D is causing caspase-dependent apoptosis in MEFs.

As an additional apoptosis assay, we determined caspase 3 and 7 activity in MEFs treated with compound 26D and in ESCs treated with compounds 199A and 223A, using camptothecin as a positive control. The results indicated that caspase 3 and 7 were activated upon treatment of ESCs with compounds 199A and 223A and MEFs upon treatment with compound 26D (Fig. 3d). Although these results are consistent with the caspase inhibition data obtained with MEFs and compound 26D, they are somehow contradictory with the results obtained from ESCs treated with compounds 199A and 223A.

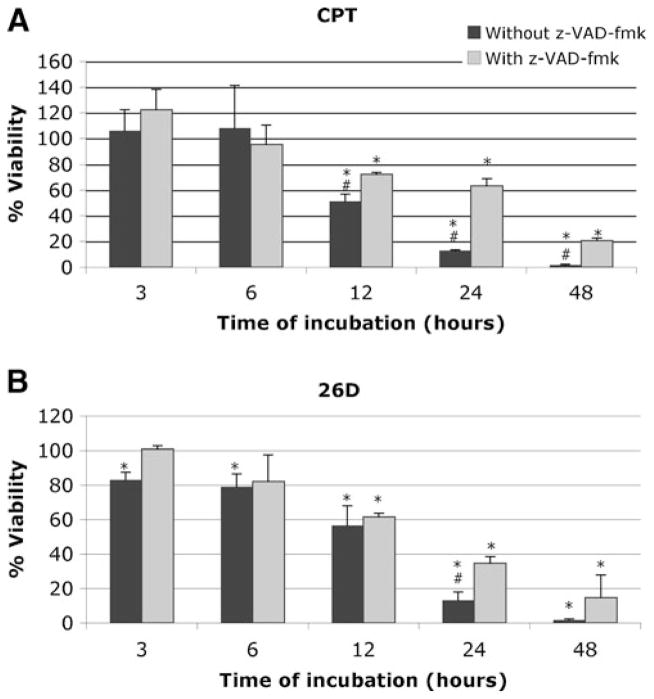

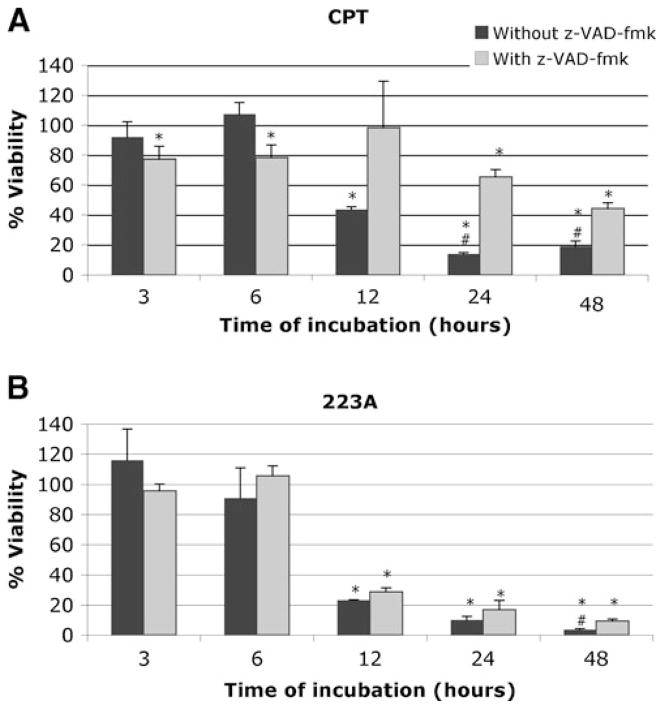

The partial improvement in MEFs viability treated with compound 26D and z-VAD-fmk suggests that caspase-independent mechanisms are additionally responsible for cell death. Since caspase-independent mechanisms, such as those mediated by release of apoptosis-inducing factor (AIF) from mitochondria, usually proceed at a slower pace than caspase-dependent ones, we carried out a time course of cell death induction by compound 26D. As compounds 199A and 223A are very similar (see below) and their effects on cell viability were almost identical, we also carried out a time course analysis of the effect of compound 223A in ESCs viability. Cells were treated with the compounds at 10 μM with or without z-VAD-fmk and assayed at 3, 6, 12, 24 and 48 h.

The viability of MEFs treated with compound 26D for different periods of time followed a pattern similar to those treated with camptothecin (Fig. 4), with the strongest effect of z-VAD-fmk observed after 24 h. Taken together these results indicate that compound 26D is inducing apoptotic cell death in MEFs.

Fig. 4.

Time course experiment with MEFs incubated with camptothecin (CPT) (a) and compound 26D (b) at 10 μM for 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h. In the absence (black bars) or presence (grey bars) of 100 μM z-VAD-fmk. The results of XTT viability assays are expressed as the mean±SD of three independent experiments (n=3), each carried out with triplicates. *, significant difference for p<0.05 with respect to the DMSO control. #, significant difference for p<0.05 with respect to the sample in presence of z-VAD-fmk

The time course of treatment with compound 223A indicated that cell death induced by this compound was not significantly altered when z-VAD-fmk was added to the culture (except at 48 h), with a pattern clearly different from that obtained with camptothecin (Fig. 5). Taken together, these results indicate that although caspases, at least caspase 3 and 7, are activated, caspase-independent cell death is mainly taking place since overall cell death is not prevented by caspase inhibition.

Fig. 5.

Time course experiment with ESCs incubated with camptothecin (CPT) (a) and compound 223A (b) at 10 μM for 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h. In the absence (black bars) or presence (grey bars) of 100 μM z-VAD-fmk. The results of XTT viability assays are expressed as the mean±SD of three independent experiments (n=3), each carried out with triplicates. *, significant difference for p<0.05 with respect to the DMSO control. #, significant difference for p<0.05 with respect to the sample in presence of z-VAD-fmk

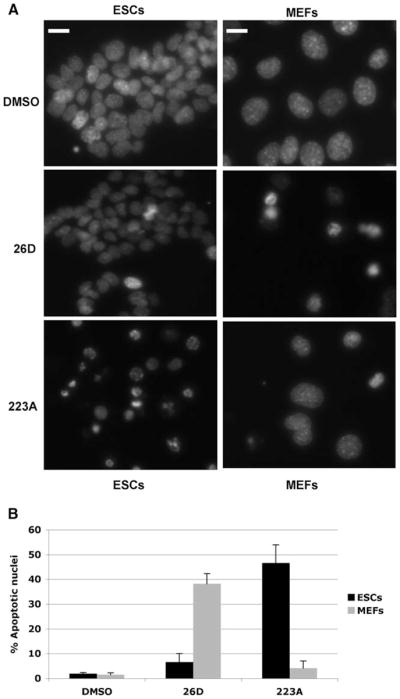

As an additional method to confirm that apoptotic cell death was taking place, cells treated with compounds 26D and 223A for 24 h were incubated with Hoechst 33342 in order to analyze the morphology of nuclei (compound 199A was not included since 199A and 223A are analogues). Apoptotic nuclei were clearly present when ESCs were incubated with compound 223A but not with compound 26D. The opposite was observed in MEFs (Fig. 6). This confirmed that these compounds induce apoptotic cell death in a cell type-specific manner.

Fig. 6.

Apoptotic nuclei in different cells treated with different compounds. ESCs and MEFs treated with compounds 26D, 223A or DMSO were stained with Hoechst 33342 and analyzed with an inverted fluorescence microscope. a Micrographs of representative fields of each preparation are shown at a magnification of 400X. Note that ESCs are smaller than MEFs. Bars are 20 μm. b Graphical representation of numbers of cells with apoptotic nuclei upon different treatments. Values are expressed as the mean±SD of two biological independent experiments, each carried out with duplicates, scoring three microscope fields per sample

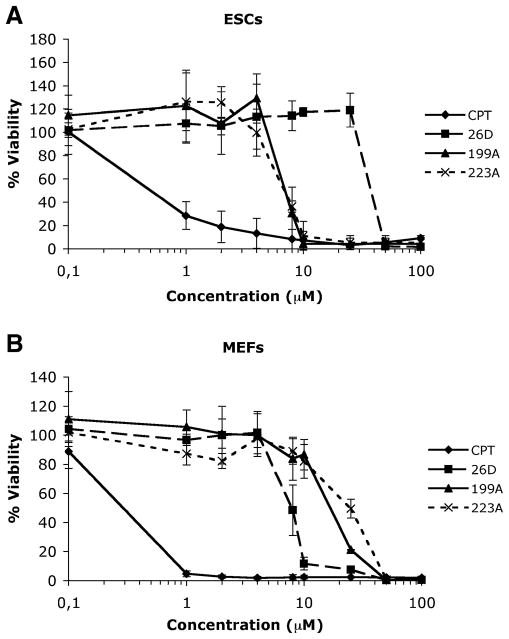

Dose/Response Assays

We analyzed the effect of compounds 26D, 199A and 223A at concentrations varying between 0.1 and 100 μM in order to determine the dose that decreased cell viability by 50% (LD50) using the XTT assay. The three compounds were analyzed using ESCs and MEFs. The LD50 value for compounds 199A and 223A in ESCs was approximately 7 μM (Fig. 7a) and 20 μM for 199A and 25 μM for 223A in MEFs (Fig. 7b). The LD50 value for compound 26D in MEFs was approximately 8 μM (Fig. 7b), and 40 μM in ESCs (Fig. 7a). These results indicate that, under these conditions, these compounds could be used to selectively kill ESCs or MEFs. We could therefore define a “selectivity index” as the ratio between the LD50 for the desired cell type and the LD50 for the undesired cell type. For selection of MEFs, the selectivity index for compounds 199A and 223A would be 2.86 and 3.57, respectively. For selection of ESCs with compound 26D, this selectivity index would be 5.

Fig. 7.

Dose-response analyses of the effect of compounds 26D, 199A and 223A on MEFs and ESCs. Compounds were used at 0.1, 1, 2, 4, 8, 25, 50 and 100 μM, on ESCs (a) or MEFs (b). Camptothecin (CPT) was used as positive control at the same concentrations. Values are expressed as the mean±SD of three independent experiments, each carried out with duplicates

Identity of Compounds 26D, 199A and 223A

Up to the point of nuclei analysis, we had worked without knowing the identity of the compounds present in our assays. Inspection of the annotations in the chemical library indicated that compound 26D was nortriptyline hydrochloride, a heterocyclic drug used to treat several disorders, like depression, nocturnal enuresis, migraines, neuralgia and also to help quit smoking. Interestingly, nortriptyline has also been described as an inhibitor of permeability transition. Compounds 199A and 223A are methylbenzethonium chloride and benzethonium chloride, respectively, analogue quaternary ammonium salts used as antimicrobial agents with broad spectrum. Benzethonium chloride has also been described as an anticancer agent. Both compounds have a similar molecular structure and similar toxic activities, and interestingly were identified due to their same effect on ESCs versus MEFs from two different groups of compounds.

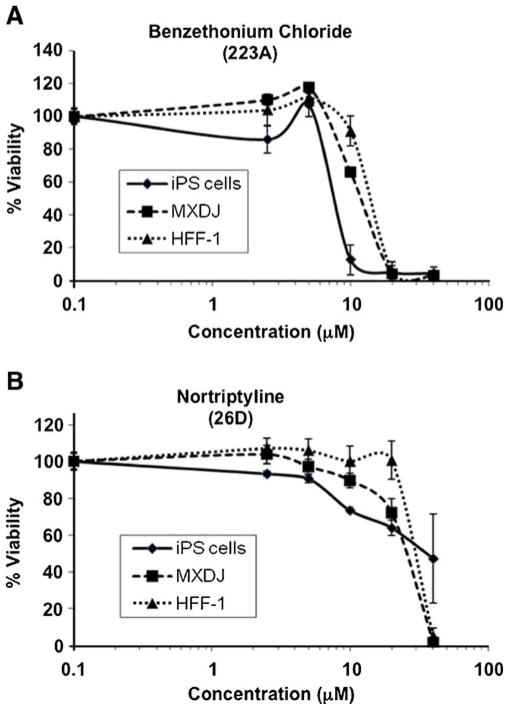

Effect of Selected Compounds on hiPSCs and Human Fibroblasts

After observing the interesting differential effects of these compounds on mouse pluripotent embryonic stem cells and fibroblasts, we decided to address whether similar effects would be observed on human cells. We therefore carried out further assays on a human induced pluripotent stem cell line, IMR90-C4, and human fibroblasts of two different origins: MXDJ, from a skin biopsy of one of the authors, and the ATCC cell line HFF-1. Since we had observed similar effects of benzethonium chloride and methylbenzethonium chloride, we used only the former in these assays. Cells were treated with benzethonium or nortriptyline under the same conditions used with mouse cells, but with concentrations ranging between 2.5 and 40 μM. The results, shown in Fig. 8, clearly indicate a higher sensitivity of hiPSCs to benzethonium than human fibroblasts, with an approximate LD50 of 7.5 μM for iPS cells and around 13 μM for both types of fibroblasts. The “selectivity index” in this case would be 1.7. On the other side, hiPSCs were more affected than fibroblasts by nortriptyline at low concentrations but tolerated higher concentrations better, although the LD50 was similar in both cases (around 28 μM for fibroblasts and 35 μM for iPS cells).

Fig. 8.

Effect of benzethonium chloride (a) and nortriptyline (b) on hiPSCs and fibroblasts. hiPSCs line IMR90-C4, human fibroblasts HFF-1 and primary skin fibroblasts MXDJ were treated with benzethonium chloride or nortriptyline at concentrations of 2.5, 5, 10, 20 and 40 μM for 48 h and assayed with XTT. Values are expressed as the mean±SD of three independent experiments carried out in triplicates, normalized to control (vehicle DMSO)

These results confirm the special sensitivity of two different types of stem cells from two different organisms to benzethonium chloride as compared to fibroblasts of different origins. Furthermore, they also indicate a special sensitivity of MEFs to nortriptyline and different responses of hiPSCs and human fibroblasts to this compound.

Discussion

We have used a forward chemical genetics approach to identify compounds with differential effects on viability of mouse ESCs, hiPSCs and fibroblasts. We screened a chemical library using the XTT colorimetric assay, which determines cell viability by detecting mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity. The murine ESC line CGR8 was selected because it grows in the absence of feeder cells, therefore allowing the use of the mentioned assay without interference from feeder cells. To emphasize the relevance of our findings for the human application model we also used hiPSCs. To accelerate the first screening we mixed compounds in groups of three or four. Although we identified several compounds that increased cell viability according to the XTT assay, in this report we focus on those that decreased it to identify possible candidates that specifically induce death of undifferentiated ESCs.

We then used a secondary screening to analyze individually those compounds from groups that caused a significant reduction in cell viability. In this secondary screening we also used MEFs in order to identify compounds with differential effects on ESCs and MEFs. Among the compounds that killed both ESCs and MEFs there are known apoptosis inducers such as camptothecin or etoposide; anthracycline antibiotics such as doxorubicin, daunorubicin or mitoxantrone; protein synthesis inhibitors such as puromycin or cycloheximide; alkaloids such as tomatine, emetine, ellipticine or lycorine; or disinfectants such as chlorhexidine, among others. Some of these compounds are used in cancer chemotherapy.

Since only ESCs were used in the first screening, we expected to identify only compounds that would kill these cells but not MEFs. However, when we analyzed individually the four compounds present in group 26, we realized that although viability reduction was caused by compound 26B, which had the same effect on both cell types, compound 26D was clearly reducing viability of MEFs but not that of ESCs. Further assays to determine the mode of cell death were carried out without knowing the identity of compound 26D. This compound is nortriptyline, a heterocyclic drug mainly used as antidepressant. The first report found in Medline about nortriptyline dates back to 1962, where its activity as an antidepressant is described [16], although heterocycles have been used clinically since the 1950’s [17]. Nortriptyline was later reported to inhibit mitochondrial monoamine oxidase (MAO) in vitro but not in vivo [18]. Interestingly, nortriptyline was identified as a potent inhibitor of mitochondrial permeability transition (mPT) [17]. Nortriptyline delays disease onset in models of neurodegeneration, particularly in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and Huntington’s disease (HD), by inhibiting release of cytochrome c from mitochondria [19]. The same group later reported that nortriptyline protects mitochondria and reduces cerebral ischemia/hypoxia injury in primary cerebrocortical neurons, inhibiting cell death by prevention of mitochondrial potential loss, release of proapoptotic factors from mitochondria and activation of caspases [20].

The results reported above are in apparent contradiction with our results reported here for MEFs. Since MEFs used in our counter-screening are transformed with SV40, we also treated wild type MEFs with these compounds and obtained similar results to those obtained with transformed MEFs (data not shown). Furthermore, as human fibroblasts of two different origins were more resistant to nortriptyline than MEFs, this indicates that MEFs are especially sensitive to this compound. Our data indicated that continuous treatment with nortriptyline caused death in MEFs by caspase-dependent and—independent mechanisms, since cell death could only be partially inhibited by inhibition of caspases. Resistance of double Bax/Bak knockout MEFs is also indicative of induction of apoptotic death in MEFs by nortriptyline, which was confirmed by detecting apoptotic nuclei. Therefore, either nortriptyline is not causing inhibition of mPT in MEFs or continuous inhibition of mPT is deleterious for these cells. Since mPT transient openings occur in intact cells [21], it is possible that continuous blockade of this pore would have negative effects for these cells. There is a great deal of controversy surrounding the composition of the permeability transition pore complex (PTPC) [22]. mPT can take place without the proteins initially reported as components of the PTPC, therefore a more dynamic view of this complex is currently considered [23], meaning that different proteins could participate in mPT in different physiological situations or under different stimuli. MEFs and nortriptyline could be used to shed light on this controversial subject.

We also identified compounds that killed ESCs but not MEFs at certain doses. Benzethonium chloride and methylbenzethonium chloride killed ESCs with an LD50 of 7 μM, whereas their LD50 values for MEFs were 25 μM and 20 μM, respectively. These compounds belong to a family of quaternary ammonium salts with surfactant activity used as disinfectants with broad antimicrobial spectra, and they can damage biological membranes. Benzethonium chloride has been described to induce enteric neurotoxicity [24]. Methylbenzethonium chloride has been used as an antileishmanial agent, and reported to induce mitochondrial swelling in treated parasites [25]. Benzethonium chloride has been recently described as a novel anticancer agent after being identified in a small-molecule screen using the same chemical library we have used, together with another library [26]. Yip and coworkers used a hypopharyngeal squamous cancer cell line (FaDu) and untransformed mouse embryonic fibroblasts (NIH3T3) in their primary screening. They used a nasopharyngeal cancer cell line (C666-1) and primary normal human fibroblasts (GM05757) in a secondary screening, determining cell viability with an MTS test (tetrazolium-based like the XTT assay we have used). These authors concluded that the LD50 for benzethonium chloride was lower (3.8 and 5.3 μM) in cancer cells than in normal cells (42.2 and 17 μM), therefore showing a clear therapeutic index. They reported that benzethonium chloride induced apoptotic cell death, causing loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and activating caspases.

Methylbenzethonium chloride was also identified in their screen. Benzethonium chloride has also been more recently reported to induce apoptosis in primary human gingival fibroblasts in vitro [27]. Our data indicate that MEFs are more resistant to benzethonium chloride and methylbenzethonium chloride than ESCs. Furthermore, assays with hiPSCs and human fibroblasts of two different origins confirmed the data obtained with mouse cells, indicating that hiPSCs are also more sensitive to benzethonium chloride than human fibroblasts.

From our results we may conclude that ESCs and hiPSCs resemble cancer cells in their lower resistance to cell death induced by benzethonium chloride. Stem cells are known to resemble cancer cells in several aspects like their unlimited proliferation capability, the fact that stem cells transplanted into mice can develop into tumors [28] and also stem cells have been derived from teratocarcinomas [29, 30]. Tsai and McKay [31] described the identification of the first known gene involved in the regulation of proliferation in both ESCs and at least some types of cancer cells, naming it nucleostemin since its product is active in the nucleus of stem cells. Nucleostemin was later reported to be necessary not only for cell proliferation but also for evasion of apoptosis in bladder cancer cells [32]. Our results indicate that chemical compounds can also be used to study apoptotic regulation common to stem cells and cancer cells.

In summary, we have identified a compound, benzethonium chloride, which is toxic for mouse embryonic stem cells as well as human induced pluripotent stem cells at concentrations at which fibroblasts from mice and human are resistant. The similar effect on two different types of pluripotent cells from different organisms suggests that there might be an underlying mechanism of toxicity that is specific for pluripotent cells, which could be shared, at least in part, with some tumor cells. Therefore, benzethonium chloride could be used as a tool to study differences in the machinery for cell death initiation and execution between pluripotent and differentiated cells. The difference in the response to nortriptyline between hiPSCs and human fibroblasts could also be exploited for the preparation of iPS cells from differentiated cells. Finally, these findings open new roads for developing new strategies for a safe stem cell based cellular therapy of degenerative diseases. Tumorigenicity assays in mice inoculated with pluripotent stem cells are under way in order to find out the pharmacological relevance of the effects observed in cultured cells as well as the usefullness of benzethonium chloride as a possible antiteratogenic agent for stem cell therapy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jesús Martínez de la Fuente, from the Instituto de Nanociencia de Aragón, for access to the inverted fluorescence microscope. This work was funded by grants from the Aragon Institute of Health Sciences to J. Sancho (PIPAMER07/02) and to J. A. Carrodeguas (PIPAMER08/17, PIPAMER09/13 and PIPAMER10/009); from the University of Zaragoza to J. A. Carrodeguas (UZ2010-BIO-03); from the Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia to J. A. Carrodeguas (BFU2006-07026); from the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación to J. Sancho (PI078/08 and BFU2010-16297) and to J. A. Carrodeguas (BFU2009-11800). The contribution by C. Antzelevitch and MX. Doss was supported by grant HL47678 (CA) from NHLBI, and grants from NYSTEM (CA), AHA National Scientist Development grant (MXD) and New York State and Florida Masons. C. Conesa is a postdoctoral fellow funded by the Programa Aragonés de Medicina Regenerativa (PAMER) and by the Institute of Biocomputation and Physics of Complex Systems.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Celia Conesa, Aragon Health Sciences Institute (I+CS), Avda. Gómez Laguna, 25, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain. Institute for Biocomputation and Physics of Complex Systems, University of Zaragoza, C/Mariano Esquillor s/n, 50018 Zaragoza, Spain.

Michael Xavier Doss, Stem Cell Center, Masonic Medical Research Laboratory, Utica, NY 13501, USA.

Charles Antzelevitch, Stem Cell Center, Masonic Medical Research Laboratory, Utica, NY 13501, USA.

Agapios Sachinidis, Center of Physiology and Pathophysiology, Institute of Neurophysiology, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany.

Javier Sancho, Institute for Biocomputation and Physics of Complex Systems, University of Zaragoza, C/Mariano Esquillor s/n, 50018 Zaragoza, Spain. Department of Biochemistry and Molecular and Cellular Biology, School of Sciences, University of Zaragoza, Pedro Cerbuna 12, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain.

José Alberto Carrodeguas, Email: carrode@unizar.es, Aragon Health Sciences Institute (I+CS), Avda. Gómez Laguna, 25, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain. Institute for Biocomputation and Physics of Complex Systems, University of Zaragoza, C/Mariano Esquillor s/n, 50018 Zaragoza, Spain. Department of Biochemistry and Molecular and Cellular Biology, School of Sciences, University of Zaragoza, Pedro Cerbuna 12, 50009 Zaragoza, Spain.

References

- 1.Keller G. Embryonic stem cell differentiation: emergence of a new era in biology and medicine. Genes and Development. 2005;19:1129–1155. doi: 10.1101/gad.1303605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brustle O, Jones KN, Learish RD, et al. Embryonic stem cell-derived glial precursors: a source of myelinating transplants. Science. 1999;285:754–756. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McDonald JW, Liu XZ, Qu Y, et al. Transplanted embryonic stem cells survive, differentiate and promote recovery in injured rat spinal cord. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:1410–1412. doi: 10.1038/70986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klug MG, Soonpaa MH, Koh GY, Field LJ. Genetically selected cardiomyocytes from differentiating embryonic stem cells form stable intracardiac grafts. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1996;98:216–224. doi: 10.1172/JCI118769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Min JY, Yang Y, Converso KL, et al. Transplantation of embryonic stem cells improves cardiac function in postinfarcted rats. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2002;92:288–296. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2002.92.1.288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soria B, Roche E, Berna G, Leon-Quinto T, Reig JA, Martin F. Insulin-secreting cells derived from embryonic stem cells normalize glycemia in streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Diabetes. 2000;49:157–162. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen RA. Studies of in vitro differentiation with embryonic stem cells. Reproduction, Fertility and Development. 1994;6:543–552. doi: 10.1071/rd9940543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Odorico JS, Kaufman DS, Thomson JA. Multilineage differentiation from human embryonic stem cell lines. Stem Cells. 2001;19:193–204. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-3-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stockwell BR. Chemical genetics: ligand-based discovery of gene function. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2000;1:116–125. doi: 10.1038/35038557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thorpe DS. Forward and reverse chemical genetics using SPOS-based combinatorial chemistry. Combinatorial Chemistry and High Throughput Screening. 2003;6:623–647. doi: 10.2174/138620703771981205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sachinidis A, Sotiriadou I, Seelig B, Berkessel A, Hescheler J. A chemical genetics approach for specific differentiation of stem cells to somatic cells: a new promising therapeutical approach. Combinatorial Chemistry and High Throughput Screening. 2008;11:70–82. doi: 10.2174/138620708783398322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, et al. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gissel C, Voolstra C, Doss MX, et al. An optimized embryonic stem cell model for consistent gene expression and developmental studies: a fundamental study. Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2005;94:719–727. doi: 10.1160/TH05-05-0338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, et al. Proapoptotic BAX and BAK: a requisite gateway to mitochondrial dysfunction and death. Science. 2001;292:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett IF. The constellation of depression: its treatment with nortriptyline. I. Criteria for true antidepressant activity. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1962;134:561–565. doi: 10.1097/00005053-196206000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stavrovskaya IG, Narayanan MV, Zhang W, et al. Clinically approved heterocyclics act on a mitochondrial target and reduce stroke-induced pathology. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2004;200:211–222. doi: 10.1084/jem.20032053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egashira T, Takayama F, Yamanaka Y. Effects of long-term treatment with dicyclic, tricyclic, tetracyclic, and noncyclic antidepressant drugs on monoamine oxidase activity in mouse brain. General Pharmacology. 1996;27:773–778. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(95)02126-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, Guan Y, Wang X, et al. Nortriptyline delays disease onset in models of chronic neurodegeneration. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2007;26:633–641. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05663.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang WH, Wang H, Wang X, et al. Nortriptyline protects mitochondria and reduces cerebral ischemia/hypoxia injury. Stroke. 2008;39:455–462. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.496810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petronilli V, Miotto G, Canton M, et al. Transient and long-lasting openings of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore can be monitored directly in intact cells by changes in mitochondrial calcein fluorescence. Biophysical Journal. 1999;76:725–734. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77239-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grimm S, Brdiczka D. The permeability transition pore in cell death. Apoptosis. 2007;12:841–855. doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0747-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Verrier F, Deniaud A, Lebras M, et al. Dynamic evolution of the adenine nucleotide translocase interactome during chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Oncogene. 2004;23:8049–8064. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fox DA, Epstein ML, Bass P. Surfactants selectively ablate enteric neurons of the rat jejunum. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1983;227:538–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El-On J, Messer G. Leishmania major: antileishmanial activity of methylbenzethonium chloride. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 1986;35:1110–1116. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1986.35.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yip KW, Mao X, Au PY, et al. Benzethonium chloride: a novel anticancer agent identified by using a cell-based small-molecule screen. Clinical Cancer Research. 2006;12:5557–5569. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nomura Y, Bhawal UK, Nishikiori R, Sawajiri M, Maeda T, Okazaki M. Effects of high-dose major components in oral disinfectants on the cell cycle and apoptosis in primary human gingival fibroblasts in vitro. Dental Materials Journal. 2010;29:75–83. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2009-031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Conway AE, Lindgren A, Galic Z, et al. A self-renewal program controls the expansion of genetically unstable cancer stem cells in pluripotent stem cell-derived tumors. Stem Cells. 2009;27:18–28. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andrews PW, Damjanov I, Simon D, Dignazio M. A pluripotent human stem-cell clone isolated from the TERA-2 teratocarcinoma line lacks antigens SSEA-3 and SSEA-4 in vitro, but expresses these antigens when grown as a xenograft tumor. Differentiation. 1985;29:127–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1985.tb00305.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanaoka K, Hayasaka M, Noguchi T, Kato Y. The stem cells of a primordial germ cell-derived teratocarcinoma have the ability to form viable mouse chimeras. Differentiation. 1991;48:83–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1991.tb00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsai RY, McKay RD. A nucleolar mechanism controlling cell proliferation in stem cells and cancer cells. Genes and Development. 2002;16:2991–3003. doi: 10.1101/gad.55671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nikpour P, Mowla SJ, Jafarnejad SM, Fischer U, Schulz WA. Differential effects of Nucleostemin suppression on cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in the bladder cancer cell lines 5637 and SW1710. Cell Proliferation. 2009;42:762–769. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2009.00635.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]