Abstract

Proteasomes are large multicatalytic proteinase complexes located in the cytosol and the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. The ubiquitin-proteasome system is responsible for the degradation of most intracellular proteins and therefore plays an essential regulatory role in critical cellular processes including cell cycle progression, proliferation, differentiation, angiogenesis and apoptosis. Besides involving in normal cellular functions and homeostasis, the alteration of proteasomal activity contributes to the pathological states of several clinical disorders including inflammation, neurodegeneration and cancer. It has been reported that human cancer cells possess elevated level of proteasome activity and are more sensitive to proteasome inhibitors than normal cells, indicating that the inhibition of the ubiquitin-proteasome system could be used as a novel approach for cancer therapy. In this review we summarize several specific aspects of research for the proteasome complex, including the structure and catalytic activities of the proteasome, properties and mechanisms of action of various proteasome inhibitors, and finally the clinical development of proteasome inhibitors as novel anticancer agents.

Keywords: Ubiqitin-proteasome pathway, proteasome inhibitors, anti-cancer drugs, chemotherapy

1. INTRODUCTION

The balance between protein synthesis and degradation is one of important homeostatic factors in eukaryotic cells. Protein degradation is essential for the cells to remove excessive proteins (such as enzymes and transcription factors that are no longer needed) or exogenous proteins transported into the cells. There are two major protein degradation systems in the cells, lysosome and proteasome complexes. The proteasome system controls degradation of intracellular proteins, while the lysosomal pathway degrades extracellular proteins imported into the cell by endocytosis or pinocytosis, [1, 2].

The ubiquitin-proteasome system controls the turn-over of regulatory proteins involved in critical cellular processes including cell cycle progression, cell development and differentiation, apoptosis, angiogenesis and cell signaling pathways [2–4]. The proteasome also contributes to the pathological state of many human diseases including cancers, AIDS, autoimmune diseases and aging, in which some regulatory proteins are either stabilized due to decreased degradation or lost due to accelerated degradation [5]. It has been suggested that the proteasomal activity is essential for tumor cell proliferation and development of tumor drug resistance [6, 7]. Therefore, the proteasome-mediated degradation pathway has been considered to be an important target for cancer therapy and prevention. We and others have reported that inhibition of the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity is associated with induction of apoptosis in tumor cells [8, 9]. The proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib (Velcade, PS-341) has been used in clinical trials and its antitumor activity has been reported in a variety of tumor models [10, 11]. In this review we will summarize the recent research trends on proteasome and mainly focus on the recent progress of the proteasome as one of the anticancer targets. We will review several specific aspects of research for the proteasome complex, including its structure and catalytic activities, properties and mechanisms of action of various proteasome inhibitors, and the clinical development of proteasome inhibitors as the anticancer agents along with their advantages and remaining problems.

2. THE UBIQUITIN-PROTEASOME SYSTEM

2.1. Discovery of the Proteasome Complexes

Before the discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, protein degradation in cells was thought to depend mainly on lysosomes which were discovered by Christian de Duve in 1949. However this conception was challenged by the report in which basal protein breakdown in the cells were not blocked by lysosomal inhibitors including leupeptin, anti-pain, and chymostatin [12]. The presence of a second intracellular degradation mechanism in cells was suggested in 1977 by Alfred Goldberg [13]. In this study, by using rabbit reticulocytes that lack lysosomes, the authors found that abnormal globins were degraded with a half-life of 15 min in an ATP-dependent fashion, while normal hemoglobin underwent little or no breakdown within these cells [13]. Also in 1977 a small protein with 76 amino acids called ubiquitin was identified by Goldknopf and Busch but the function was not elucidated at that time [14]. During the same period Avran Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover and Irwin Rose were also working on this problem, which eventually led to the discovery of the 26S proteasome, a proteolytic complex, which was responsible for ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation [15–17]. Avran Hershko, Aaron Ciechanover and Irwin Rose shared the 2004 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work in discovering the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

2.2. The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System, a Principal Mechanism for Cellular Protein Catabolism

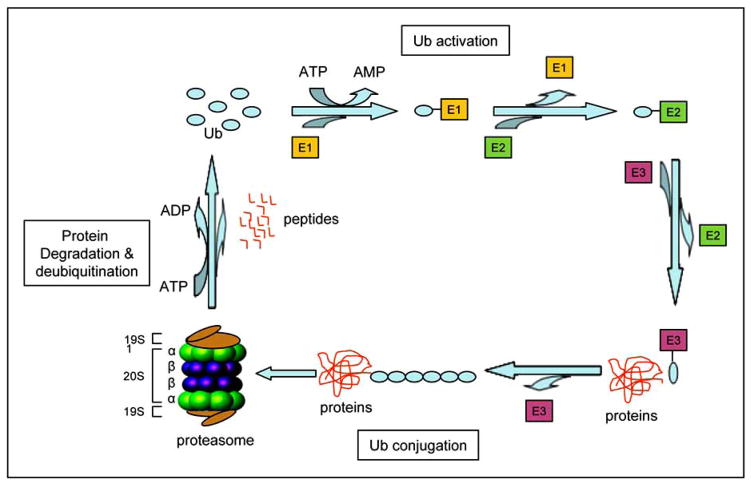

The proteasome is a multicatalytic complex and is referred to as the 26S proteasome according to its sedimentation coefficient. The 26S proteasome is composed of a 20S catalytic core and two 19S regulatory caps on both ends of the 20S core. The 20S proteasome contains of four stacked rings that form a barrel-shaped molecule with a central cavity. These stacked rings include two non-catalytic outer rings called α-rings and two catalytic inner rings called β-rings Fig. (1). At least three primary proteolytic activities are confined to the β-subunits including chymotrypsin-like (cleavage after hydrophobic amino acids, mediated by the β5 subunit), caspase-like (cleavage after acidic residues, mediated by the β1 subunit), and trypsin-like (cleavage after basic residues, mediated by the β2 subunit) activities [18]. The 19S proteasome is involved in binding and unfolding of ubiquitinated proteins, and opening the alpha subunit gate of the 20S proteasome to allow for entry into the catalytic core [18–20].

Fig. (1).

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. The ubiquitination of target proteins is mediated by Ub-activating (E1), Ub-conjugating (E2), and Ub-ligating (E3) enzymes. Substrate proteins tagged with a multiple-ubiquitin chain are degraded by a large 2000-kD protease complex called the 26S proteasome which is composed of a 20S catalytic core and two 19S caps.

The protein degradation through the ubiquitin proteasome system starts from attaching a chain of multiple ubiquitin molecules to the proteasome target proteins. Ubiquitin is a highly conserved small protein with 76-amino acids. Ubiquitin serves as a tag for degradation of targeted proteins through covalent binding. Three different enzymes, Ub-activating (E1), Ub-conjugating (E2), and Ub-ligating (E3), are involved in the process of protein ubiquitination [21] (Fig. (1)). The E1 enzyme activates ubiquitin in an ATP-requiring manner by forming a thiol ester bond at its C terminus. Activated ubiquitin is transferred from E1 to one of several distinct ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes E2. Through an additional thiol-ester bond, the ubiquitin is then transferred to the lysine residues of a target protein with the help of E3 [22] (Fig. (1)). There is only one common E1 enzyme but a couple dozens of E2 enzymes, and several hundreds of target-specific E3 enzymes in cells [23, 24]. The specificity of E3 enzymes in cells provides selectivity of proteasome target proteins for degradation [21, 25].

3. STRUCTURES AND BIOLOGICAL FUNCTIONS OF THE PROTEASOME COMPLEXES

3.1. Crystal Structure of the Proteasome Complexes and their Proteolytic Activities

Although the stacked-ring structure of the proteasome was revealed by Kopp et al. in 1986 through investigating the proteasome in rat skeletal muscle by an electron microscope [26], its exact structure in three-dimensions (3-D) was still unknown. The first 3-D structure of the proteasome from the archaebacterium Thermoplasma acidophilum was elucidated by x-ray crystallographic analysis in 1995 [27]. The findings showed that the 673-kilodalton (kDa) protease complex consists of 28 subunits (14 alpha subunits with 25.8 kDa each, and 14 beta subunits with 22.3 kDa each), forming a barrel-shaped structure of four stacked rings at an α7β7β7α7 arrangement [27] (Fig. (2)). Within the 20S proteasome there is a narrow channel which controls access of proteins to the inner compartments of the 20S proteasome. The measurements of the channel indicate that the entrance of the channel is only 13 Å, the bottleneck of the channel is 22 Å and the central cavity is 53 Å in diameters and 38 Å in lengths [27] (Fig. (2)). Therefore the channel is very narrow and only unfold proteins are allowed to access for degradation [23, 28]. The threonine residue (Thr1) at the amino terminal in all the three β-subunits is considered to be the catalytically active site [23].

Fig. (2).

20S proteasome. A, The cartoon shows a side view of 20S proteasome which possesses two outer α rings and two inner β rings. Each ring consists of seven α or seven β subunits. The catalytic activities of the β rings in 20S are found within the β1, β2, and β5 subunits. B, A cutaway stereoview of 20S proteasome shows the active sites (yellow) within the β rings. Adopted from Rechsteiner et al. Trends Cell Biol, 15:27–33, 2005, with permission from the Elsevier Ltd.

Electron microscopic images showed that two 19S caps, which have a molecular mass of 700 kDa, flexibly attach on the both ends of 20S proteasome core. The 19S complex serves to recognize ubiquitinated proteins, unfold and send these proteins into 20S core for degradation [29, 30].

3.2. The Role of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome Pathway in Cell Cycle Control and Tumorigenesis

One of the critical mechanisms for the cell cycle control is the activation of cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs). The activities of CDKs are controlled by the ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis of key regulators including cyclins and CDK inhibitors since all cyclins (D, E, A, B) and CDK inhibitors (p27, p21) are proteasome targets [31]. Actually both types of molecules, cyclins and CDKs have no catalytic activity and CDKs are activated only in the presence of and bound by a partner cyclin. Activated cyclin-CDK complexes are able to phosphorylate their target proteins, resulting in the cell cycle progress. CDK proteins are constitutively expressed in cells and cyclins are synthesized at specific stages of the cell cycle and degrades by the ubiquitin-proteasome system [31]. The half lives of cyclins and CDK inhibitors are pretty short and the levels of these proteins are periodic during cell division cycles. Therefore cell cycles are mainly controlled by the post-translational regulation which includes two types of protein modification: phosphorylation and ubiquitination. The specific ubiquitination of many cell cycle regulators are involved by two E3 ubiquitin ligases which are the Skp1/Cullin/F-box protein (SCF) complex and the Anaphase-promoting complex (APC) [32–34].

The SCF complexes are the largest family of E3 ligases consisting of Skp1, Cullins (Cul1), Cdc53, F-box proteins (FBP), the RING domain protein RBX1 (RING box protein-1) and ROC1 (regulator of cullins-1) protein [35, 36]. FBPs bind Skp1 and, in turn, link to Cul1, Roc1 and an E2 enzyme. FBPS are also responsible for recognizing and recruiting the substrates into this E3 complex [37]. The next step for the E3 complex is to transfer ubiquitin proteins from E2 to the substrates. Within the SCF complex, S phase kinase-associated protein 2 (Skp2) is another substrate specific factor. The SCF E3 enzyme complex containing Skp2 is responsible for ubiquitination of CDK inhibitors p27, p21 [38] and other tumor suppressors retinoblastoma (Rb) and p53 [39–41]. Regarding the ubiquitination of p27, p27 protein is firstly phosphorylated by cyclin-CDK complexes at the threonine 187 (T187). The F-box protein and Skp2 can specifically recognize phosphorylated p27 and link ubiquitin proteins onto the p27 proteins for degradation by the protea-some [42]. The degradation of p27 results in release of active cyclin E-cdk2 complexes which phosphorylate Rb proteins, leading to the release of the transcription factor E2F that starts transcription of genes required for G1/S phase transition [43, 44] (Fig. (3)). Degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27 is prerequisite for cells to entry a cell division cycle. As a subunit in the E3 complex, Skp2 is a critical factor for regulating G1/S phase transition.

Fig. (3).

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is implicated in cell cycle regulation. Spk2 is an oncoprotein and a specific ubiquitin E3 ligase for p27. Spk2 is able to facilitate ubiquitination and degradation of the cell cycle inhibitor p27, resulting in cell cycle progression from G1 to S phase. All p27, cyclin E, Rb and E2F proteins are proteasome targets.

APC is another class of E3 enzyme complexes regulating multiple cellular functions including cell cycle progression, cellular differentiation and signal transductions [45–47]. It has been reported that that APC targets and rapidly degrades Skp2 and that this degradation stabilizes the cell cycle inhibitor protein p27 and therefore prevents cells from abnormal entry into S phase [48, 49] (Fig. (3)).

The accumulating evidence shows that the proteasome activity is elevated in many kinds of cancers [50–53]. An elevated proteasome activity contributes to tumorigenesis, particularly by providing cancer cells with antiapoptotic protection, uncontrolled cell division and metastasis by means of getting rid of cell cycle inhibitor such as p27 and p21, pro-apoptosis proteins such as Bax, and tumor suppressors including p53 and Rb proteins [52, 54–58]. Recent studies have revealed that tumor cells are much more sensitive to proteasome inhibitors than normal cells, indicating that tumor cells particularly depend on high proteasome activity [59–61]. As mentioned above, within the ubiquitin-proteasome system Skp2 is a subunit of the SCF ubiquitin ligase complex targeting p27 for ubiquitination. Over-expression of Skp2 has been implicated in cell transformation and tumorigenesis. Elevated Skp2 activity and low level of p27 are frequently detected in human tumors and also correlated with poor prognosis [49, 62]. During tumorigenesis increasing amounts of p27 proteins are ubiquitinated by Skp2, due to its increased activity, and degraded by the proteasome, resulting in uncontrolled cellular division, ultimately leading to transformation and tumor development.

4. PROTEASOME INHIBITORS AND ANTICANCER THERAPY

4.1. Proteasome Inhibitors

The proteasome inhibitors are broadly divided into two groups of synthetic and natural proteasome inhibitors. Most synthetic inhibitors are peptide-based compounds including peptide benzamides, peptide α-ketoamides, peptide aldehydes, peptide α-ketoaldehydes, peptide vinyl sulfones, and peptide boronic acids. Natural proteasome inhibitors include peptide epoxyketones, peptide macrocycles and γ-lactam thiol ester [63].

MG132 (Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-al) is synthetic peptide aldehydes proteasome inhibitor with potent, reversible and cell-permeable characteristics [64]. This compound represents the first peptide aldehyde proteasome inhibitor that can penetrate living cells and selectively and reversibly inhibit intracellular proteolysis by 26 proteasome. Bortezomib (Velcade, formerly known as PS-341) is another synthetic dipeptide boronic acid proteasome inhibitor developed by Millenium Pharmaceuticals. Bortezomib is the first proteasome inhibitor to enter clinical trials and to receive regular approval from the US Food and Drug Administration as a front line therapy in multiple myeloma and for relapsed/refractory mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) [65]. In animal studies, Bortezomib suppresses tumor growth and angiogenesis in solid tumors, including breast cancer, prostate cancer, lung cancer, neuroblastoma and mesothelioma [66–69]. The clinical trials using Bortezomib alone or in combination with various anti-cancer agents in phase I, II and III on non-Hodgkin lymphoma, acute myeloid leukemia, and multiple myeloma patients showed favorable responses, in terms of response rate, time to progression, and survival [70–72].

Lactacystin is a natural proteasome inhibitor isolated from Streptomyces bacteria [73]. Lactacystin was discovered in 1991 according to its ability to induce neurite outgrowth in Neuro 2a cells (a mouse neuroblastoma cell line) [74]. Fenteany et al. discovered that lactacystin could target the 20S proteasome and inhibit all three distinct activities of the 20S proteasome at different rates by an irreversible modification of the terminal threonine of β-subunits [75]. The active component of lactacystin is the clasto-lactacystin β-lactone which is a rearrangement product of lactacystin in aqueous condition [76]. Gliotoxin is another natural proteasome inhibitor produced by several fungi including asper-gillus, trichoderma and penicillium [77]. Gliotoxin was found as a potent inhibitor of NF-κB [78]. Later studies revealed that gliotoxin was a non-competitive inhibitor selectively against chymotrypsin-like activity of the 20S proteasome in vitro. In cultured cells, gliotoxin inhibited NF-κB induction through inhibition of proteasome-mediated degradation of IκB-α [79].

4.2. Proteasome Inhibition Induces Apoptosis in Tumor Cells

Apoptosis is the process of programmed cell death and plays an important role in the development of an organism and in tissue homeostasis. Deregulation of apoptosis is involved in many human pathological conditions including cancer [80]. Cellular apoptosis occurs via intra- or extra-cellular signaling pathways called intrinsic or extrinsic apoptotic pathways. The intrinsic apoptotic pathway is initiated by the mitochondria [81] and the extrinsic apoptotic pathway is trigged by several transmembrane death receptors including Fas receptor, tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR), death receptor 4 (DR4) and death receptor 5 (DR5) [82–84].

The ubiquitin-proteasome system plays an important role in regulating apoptosis pathways on multiple levels [85, 86]. (i) Many proapoptotic proteins, such as p53, FOXO1, and Bax are direct targets of the proteasome [52, 87, 88]. The proteasome-dependent degradation of these proapoptotic proteins is constantly active to protect normal cells from apoptosis. (ii) The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway can also rapidly degrade anti-apoptotic proteins, such as MCL-1 [89], which is a member of the Bcl-2 family. The proteasome inhibition is capable to block the degradation of MCL-1, demonstrating a role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in regulating cellular apoptosis [90]. Failure to degrade MCL-1 results in resistance to apoptosis and subsequent tumor progression. (iii) The proteasome pathway also regulates cellular apoptosis through the degradation of IkB, an inhibitor of the NF-κB pathway, which is an important antiapoptotic player [91].

The central event of intrinsic apoptosis is the mitochondria. When cells detect apoptotic stimuli, release of cytochrome c into the cytosol occurs and in turn cytochrome c activates the caspase cascade resulting in cellular apoptosis. The release of cytochrome c from mitochondria is regulated by Bax, which is a member of the Bcl-2 family of proteins. Under normal conditions, Bax is localized in the cytosol as a monomer. During apoptosis, Bax translocates to mitochondria and undergoes conformational changes to form a functional dimer [92]. This Bax dimer penetrates the mitochondria membrane inducing the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and cytochrome c is released into the cytosol initiating activation of caspases [93]. Bax translocation onto the mitochondria and cytochrome c release to the cytosol are two critical upstream molecular events of intrinsic cellular apoptosis. Therefore cancer cells with elevated proteasome activity can constantly degrade Bax proteins and maintain cancer cell survival. Conversely, proteasome inhibitors, such as lactacystin, MG132 or Bortezomib, suppress proteasome activity in tumor cells, accumulate proapoptotic protein Bax, and result in apoptotic cell death [52].

The extrinsic apoptosis is initiated by external stimuli through death receptors. Death receptors include Fas (APO-1/CD95), TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1), TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor 1 (TRAIL-R1), TRAIL-R2 and their related ligands [94, 95]. Death receptors contain a cytoplasmic tail called the death domain, which is crucial for transmission of the death signal from the cell surface to intracellular signaling pathways. Although TNF-α is a potent mediator of apoptosis, activation of the transcription factor NF-κB can block the cell death in response to TNF-α and other signals and ultimately prevent apoptosis [43]. NF-κB pathway is an important antiapoptotic molecule that plays an key role in tumorigenesis via transactivation of genes involved in cell proliferation, apoptosis, tumor cell invasion and metastasis [96]. NF-κB is normally sequestered in the cytoplasm through association with its endogenous inhibitor IκB-α [91]. SCF ubiquitin E3 ligase links poly-ubiquitins on IκB-α proteins for proteasome degradation [97], results in translocation of NF-κB into the nucleus and mediates transcription of anti-apoptotic genes. However, accumulation of the IκB-α protein via proteasome inhibition prevents the activation of anti-apoptotic NF-κB resulting in tumor cell apoptosis [98].

4.3. Proteasome Inhibition Suppresses Tumor Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis, defined as the formation of new blood vessels, is an important and necessary function in both normal physical condition, such as embryonic development and wound repair [99, 100], and pathological conditions, such as inflammation and cancers [101]. Tumor growth, survival, and metastasis require angiogenesis. The progression of angiogenesis is regulated by proangiogenic factors and angiogenesis inhibitors [102]. Proangiogenic factors include vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs), fibroblast growth factors (FGF-1, -2), transforming growth factors (TGF-α, - β), granulocyte macrophage-colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), interleukin-1 (IL-1), IL-8, etc [102–104]. The VEGF family consists of placenta growth factor (PIGF), VEGF-A, VEGF-B, VEGF-C, VEGF-D, and VEGF-E [105, 106]. VEGF-A is upregulated under hypoxic conditions, through the binding of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) to the hypoxia-regulated element in the VEGF-A promoter [107]. Hypoxic conditions are often found in the center of growing tumors. Hypoxia leads to increased expression of VEGF-A mRNA and protein, which in turn stimulates angiogenic growth of vessels into the tumor tissue and facilitating tumor growth [108, 109].

Proteasome inhibitors can down-regulate key angiogenic factors including VEGF. It has been shown that VEGF mRNA expression depends upon cellular levels of p53 [110]. Induction of p53 is able to decrease expression of VEGF and proteasome inhibition can block VEGF expression through p53 accumulation [110]. Recent studies show that p53 promotes Mdm2-mediated ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of the HIF-1α which is a transcription factor that regulates angiogenesis in response to oxygen deprivation. Inactivation of p53 in tumor cells enhances HIF-1α levels and increases HIF-1-dependent transcriptional activation of the VEGF gene in response to hypoxia [111]. VEGF is also regulated by the NF-κB pathway [112]. As described above, the endogenous inhibitor of NF-κB (IκBα) is regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway [113] and it is well established that the NF-κB pathway is of significant importance to many biological processes in cancers including angiogenesis [112, 114]. Inhibition of the proteasome activity results in accumulation of IκBα which inhibits NF-κB and in turn down regulates the angiogenic factor VEGF and other pathways related to cancer [115].

Studies have investigated the capacity for Bortezomib, the first proved proteasome inhibitor for cancer therapy by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), to induce growth arrest of tumors, prevent metastasis, and block VEGF expression and angiogenesis [10, 116]. In animal studies Bortezomib showed more than 50% suppression in blood vessel development in tumor xenografts, with survival time more than doubled (34 days) for treated mice compared with the untreated mice (14 days) [117]. Bortezomib was also shown to inhibit the growth of human pancreatic tumor xenografts through inhibition of angiogenesis in nude mice [118], and down-regulation of NF-κB-dependent proangiogenic cytokine expression in xenografts with squamous cell carcinoma [119] and human myeloma [117].

4.4. Proteasome Inhibitors as an Anticancer Agent: Advantages and Remaining Problems

As a milestone, Bortezomib is the first proteasome inhibitor to enter clinical trials for the treatment of relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma [11, 120]. Bortezomib was also tested in the clinic against other hematological malignancy such as non-Hodgkin lymphoma [121] and solid tumors [122], both as a single agent and in combination with conventional anticancer drugs [70]. Proteasome inhibitors have presented their following advantages in cancer therapy.

The proteasome is a novel biochemical target and proteasome inhibitors such as Bortezomib represent a unique class of antitumor agents.

Bortezomib is very efficacious in treatment of multiple myeloma patients. Multiple myeloma is a hematologic malignancy characterized by the accumulation of clonal plasma cells at multiple sites in the bone marrow. The majority of the patients respond to initial chemotherapy but most of them eventually become refractory and relapse due to the proliferation of resistant tumor cells [123]. Clinical trials were shown that the response rate to Bortezomib was surprisingly 35% in the enrolled multiple myeloma (MM) patients, who in majority had been treated with 3 or more of the conventional drugs against myeloma and were refractory to their previous therapies [124].

High selectivity of proteasome inhibitors. The preferential apoptotic effect of proteasome inhibition with Bortezomib treatment has been well established in myeloma cell lines. Multiple myeloma cell lines are more sensitive to treatment with Bortezomib compared with the bone marrow cells or peripheral blood mononuclear cells from healthy individuals. Hideshima et al. demonstrated that myeloma cell lines or patient-derived myeloma cells were at least 170-fold more sensitive to Bortezomib than bone marrow stromal cells [6]. Other studies showed that proteasome inhibitor lactacystin induced apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells and oral squamous cell carcinoma cells at doses that had no apoptotic effect on normal human lymphocytes and oral epithelial cells [125, 126].

Inhibition of multiple tumor targets by proteasome inhibitors. Bortezomib appears not only to have activity against MM cells, but also inhibits blood vessel development and suppresses interactions of MM cells with bone marrow stem cells in the bone marrow microenvironment, which may contribute to MM cell drug resistance [124].

Reversibility of proteasome inhibition. Maximum inhibition of 20S activity has been observed 1 hour after the administration and, importantly, proteasome inhibition was completely reversible with a return to baseline by 72 hours [127].

Chemosensitization of other anticancer drugs by proteasome inhibition. Bortezomib has enhanced the sensitivity of cancer cells to traditional tumoricidal agents, and appeared to overcome drug resistance [6, 7].

Related problems of proteasome inhibitors as anticancer drugs, especially for Bortezomib are listed below. (i) Side effects. Although Bortezomib has achieved significant clinical benefit for MM in the clinical trials, its effectiveness and administration have been limited by toxic side effects. The most frequently site effects (incidence >30%) associated with the use of Bortezomib reported for the clinical trials include asthenic conditions (such as fatigue, generalized weakness), gastrointestinal events (nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, poor appetite, etc.), hematological toxicity (low platelet and erythrocytes counts), peripheral neuropathy characterized by decreased sensation, paresthesia (numbness and tingling of the hands and feet), and high rate of shingles [128, 129]. The less common side effects (occurring in about 10–29%) of patients receiving Bortezomib include headache, insomnia, joint pains, arthralgia, myalgias, edema of the face, hands, feet or legs, and also include low white blood cell count (it can increase risk for infection, shortness of breath, dizziness, rash, etc) [130].

(ii) Interactions of Bortezomib with several natural compounds. Some natural compounds can interfere, rather than synergize the anticancer effect of Bortezomib. Most recently, it has been reported that the proteasome-inhibitory and anti-cancer activity of Bortezomib and other boronic acid-based proteasome inhibitors can be blocked by green tea polyphenols [131, 132]. This is because of the interaction of the boric acid structure of Bortezomib and EGCG’s catechol structure to form a borate ester. It is not the problem of green tea intake. Rather, it is the inherent problem of Bortezomib for having a reactive boric acid structure. Similarly, it has been found that dietary flavonoids and ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) also inhibit the anticancer effects of the proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib via similar drug-drug interaction mechanism [133, 134].

(iii) Bortezomib does not present satisfied efficacy on treatment of solid tumors. Yang et al [135] summarized and concluded their clinical trials on metastatic breast cancer patients that in total 12 enrolled patients, no objective responses were observed. One patient had stable disease, but 11 other patients experienced disease progression. The median survival time was only 4.3 months. The results of this trial suggested that Bortezomib was well tolerated but showed limited clinical activity against metastatic breast cancer when used as a single agent [135]. Results from a phase II study of Bortezomib in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors showed that of 16 patients not one achieved a partial or a complete remission and single-agent Bortezomib did not induce any objective responses [136]. Kondagunta et al. [137] reported according to a phase II clinical trial using Bortezomib in 37 patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma that a partial response was observed in 4 patients (11%) and stable disease in 14 patients (38%). They concluded that the small proportion of patients who achieved a partial response does not support routine use in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma [137].

The observations from laboratory studies and clinical trials may suggest that for chemotherapy of solid tumors it is possible to further increase the anticancer potency of Bortezomib by combining it with some novel types of other conventional anticancer agents [120]. Clinical trials have indicated that combination of Bortezomib with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin [138], melphalan [139], dexamethasone [140], cyclophosphamide [141], dexamethasone [142], thalidomide [143], or arsenic trioxide [144] was significantly more effective than Bortezomib alone. However, conclusions from another phase II study of Bortezomib alone or combination with Docetaxel in total of 155 patients with advanced non–small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) showed that Bortezomib has modest single-agent activity in patients with relapsed or refractory advanced NSCLC, and with minor enhancement in combination with docetaxel [145].

4.5. Natural Compounds with Proteasome-Inhibitory Activity: Use in Cancer Prevention and Treatment

The cancer-preventive effects of green tea is widely supported by results from epidemiological, cell culture, animal and clinical studies. The major polyphenols of green tea include (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate [(-)-EGCG], (-)-epigallocatechin [(-)-EGC], (-)-epicatechin-3-gallate [(-)-ECG], and (-)-epicatechin [(-)-EC]. Among these tea polyphenols, (-)-EGCG has been extensively studied and implicated as a cancer preventative agent. The studies from our lab have shown that green tea polyphenols, and specifically those with ester bonds, (-)-EGCG, (-)-ECG, (-)-GCG, (-)-CG, have potent proteasome-inhibitory properties selective for the chymotrypsin-like activity [146]. This inhibition was accompanied by apoptosis induction and was limited to cancer cells [146–148].

We have studied the mechanism of proteasome inhibition by tea polyphenols and hypothesized that the ester-carbon on the polyphenol could be subject to nucleophilic attack by the hydroxyl group of the N-terminal threonine of the β5 subunit [147]. We verified the hypothesis via the approach of computational modeling [147]. These studies compared the binding energies and IC50 values of a variety of (-)-EGCG analogs including those where an amide bond substituted the ester bond [147, 149]. The results showed that the ester carbon of (-)-EGCG would line up with the hydroxyl of the N-terminal threonine placing the carbonyl carbon within 3 – 4 Å at an optimal distance for nucleophilic attack [147]. Furthermore the actual IC50 values of the EGCG analogs were predicted by the binding energies of the compounds. These results provide strong support for (-)-EGCG as a direct inhibitor of the proteasome [147].

(-)-EGCG is the polyphenol that possesses the most potent biological effect in green tea. However it is unstable in neutral or alkaline conditions (i.e. physiologic pH). The hydroxyl groups of (-)-EGCG are subject to be modified through biotransformation reactions, including methylation, glucuronidation, and sulfation, resulting in reduced biological activities in vivo [150, 151]. In an effort to discover more stable polyphenol proteasome inhibitors, we synthesized several (-)-EGCG analogs with -OH groups eliminated from the B- and/or D-rings. In addition, we also synthesized their putative prodrugs with -OH groups protected by acetate, named Pro-EGCG, of which the acetate on each –OH group can be removed by cellular cytosolic esterases [152]. We found that compared to EGCG, protected analogs exhibited greater potency to inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in human leukemic, prostate and breast cancer cells [153]. We further compared Pro-EGCG with natural EGCG for their anti-tumor activity in vivo. The results showed that treatment with Pro-EGCG for 31 days in human breast MDA-MB-231 xenografts in nude mice resulted in an inhibition of tumor growth by 56%. As a comparison, the treatment with (-)-EGCG resulted in 23% inhibition of the tumor growth [154].

Curcumin (diferuloylmethane) is a major component of the spice turmeric. It has been reported that Curcumin possesses inhibitory effect on inflammation [155] and carcino-genesis via suppression of NF-kB pathway [156]. We found that curcumin could potently inhibit the chymotrypsin-like activity of a purified 20S proteasome (IC50=1.85 μM). Curcumin also inhibited proteasome activity in human colon cancer HCT-116 and SW480 cell lines, and leaded to accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and other proteasome target proteins, and subsequent induction of apoptosis [157]. Furthermore, treatment of HCT-116 colon tumor–bearing ICR SCID mice with curcumin resulted in decreased tumor growth, associated with proteasome inhibition, proliferation suppression and apoptosis induction in tumor tissues [157].

Genistein is one of the predominant soy isoflavones and numerous studies have evaluated its anticancer activities. To examine whether genistein acts as a proteasome inhibitor, we have utilized computational docking studies using genistein as the ligand and the proteasome as the molecular target to show that genistein interacts with the proteasomal β5 subunit in a manner that suggests proteasome inhibition [158]. Our in vitro result demonstrated that genistein inhibits the chymotrypsin-like activity of purified 20S proteasome in a concentration-dependent manner and the IC50 value was found to be 26 μM [158]. Genistein could also inhibit proteasome activity in prostate cancer LNCaP and breast cancer MCF-7 cells and induce apoptosis in these solid tumor cells [158]. These findings suggest that the proteasome is one of the targets of genistein in human tumor cells and that inhibition of the proteasome activity by genistein might contribute to its cancer-preventive properties. Therefore, targeting tumor proteasome pathway by natural compounds could provide a unique strategy for cancer prevention and treatment.

Salinosporamide A (NPI-0052) is a novel proteasome inhibitor discovered from Salinispora tropica, a Gram-positive actinomycete of marine bacterium [159]. NPI-0052 is a bicyclic β-lactone-γ-lactam and irreversible nonpeptide proteasome inhibitor [160]. NPI-0052 inhibits proteasome activity by covalently modifying the active site threonine residues of the proteasomal β subunits [161]. Bortezomib has been used as an effective anticancer therapy for the treatment of relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma, but it has been shown that its limitation is associated with toxicity and development of drug resistance. NPI-0052 can overcome the resistance and induce apoptosis in MM cells resistant to Bortezomib therapies [162]. Chauhan et al. treated mice with a single dose of NPI-0052 (0.15 mg/kg i.v.) or Bortezomib (1 mg/kg i.v.), and found that NPI-0052 completely inhibited chymotrypsin-like activity by 90 min and was recovered by 168 hr, whereas Bortezomib-inhibited chymotrypsin-like activity was markedly restored at 24 hr [162]. The results demonstrated that compared with Bortezomib, NPI-0052 was more potent and the inhibitory effect sustained longer. NPI-0052 has being developed by Nereus Pharmaceuticals and is being tested in Phase I clinical trials for the patients resistant to Bortezomib. The results from a phase I clinical trial showed that NPI-0052 had no significant toxicity and did not induce peripheral neuropathy or myelosuppression [163].

CONCLUSIONS

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is involved in many critical cellular processes and the proteasome has been regarded as a novel target for cancer therapy. As a single agent for multiple myeloma treatment, the antitumor activity of the proteasome inhibitor Bortezomib is well investigated in phase I, II and III clinical trials. The chemosensitizing properties of Bortezomib have also been demonstrated in different types of solid tumors. However, there are some problems associated with the clinical trials using Bortezomib, such as side effects caused by its cellular toxicity and clinical limitation as a single agent for solid tumors, which have attracted an increasingly attention for discovery of none or much less toxic proteasome inhibitors from natural resources. Also, in order to improve the safety and increase efficacy of proteasome-inhibitor drugs with more specific inhibiting targets or pathways, the design of potential E2 or E3 inhibitors, such as Skp2 inhibitors which can target earlier steps of the ubiquitin-proteasome system are a desirable direction in the future.

Acknowledgments

The research was partially supported by grants from National Cancer Institute (1R01CA120009, 3R01CA120009-04S1, and 1R21CA139386-01 to Q.P. Dou).

References

- 1.Goldberg AL. Functions of the proteasome: the lysis at the end of the tunnel. Science. 1995;268:522–523. doi: 10.1126/science.7725095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hochstrasser M. Ubiquitin, proteasomes, and the regulation of intracellular protein degradation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995;7:215–223. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway. Cell. 1994;79:13–21. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90396-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orlowski RZ, Dees EC. The role of the ubiquitination-proteasome pathway in breast cancer: applying drugs that affect the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway to the therapy of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5:1–7. doi: 10.1186/bcr460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway: on protein death and cell life. EMBO J. 1998;17:7151–7160. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hideshima T, Richardson P, Chauhan D, Palombella VJ, Elliott PJ, Adams J, Anderson KC. The proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibits growth, induces apoptosis, and overcomes drug resistance in human multiple myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3071–3076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landis-Piwowar KR, Milacic V, Chen D, Yang H, Zhao Y, Chan TH, Yan B, Dou QP. The proteasome as a potential target for novel anticancer drugs and chemosensitizers. Drug Resist Update. 2006;9:263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.An B, Goldfarb RH, Siman R, Dou QP. Novel dipeptidyl proteasome inhibitors overcome Bcl-2 protective function and selectively accumulate the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 and induce apoptosis in transformed, but not normal, human fibroblasts. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:1062–1075. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopes UG, Erhardt P, Yao R, Cooper GM. p53-dependent induction of apoptosis by proteasome inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:12893–12896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.12893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adams J. Development of the proteasome inhibitor PS-341. Oncologist. 2002;7:9–16. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.7-1-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kane RC, Farrell AT, Sridhara R, Pazdur R. United States Food and Drug Administration approval summary: bortezomib for the treatment of progressive multiple myeloma after one prior therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2955–2960. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neff NT, DeMartino GN, Goldberg AL. The effect of protease inhibitors and decreased temperature on the degradation of different classes of proteins in cultured hepatocytes. J Cell Physiol. 1979;101:439–457. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041010311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Etlinger JD, Goldberg AL. A soluble ATP-dependent proteolytic system responsible for the degradation of abnormal proteins in reticulocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:54–58. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldknopf IL, Busch H. Isopeptide linkage between nonhistone and histone 2A polypeptides of chromosomal conjugate-protein A24. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:864–868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.3.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ciehanover A, Hod Y, Hershko A. A heat-stable polypeptide component of an ATP-dependent proteolytic system from reticulocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978;81:1100–1105. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91249-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hershko A, Ciechanover A, Heller H, Haas AL, Rose IA. Proposed role of ATP in protein breakdown: conjugation of protein with multiple chains of the polypeptide of ATP-dependent proteolysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1980;77:1783–1786. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.4.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hershko A, Ciechanover A, Rose IA. Resolution of the ATP-dependent proteolytic system from reticulocytes: a component that interacts with ATP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:3107–3110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.7.3107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groll M, Bajorek M, Kohler A, Moroder L, Rubin DM, Huber R, Glickman MH, Finley D. A gated channel into the proteasome core particle. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:1062–1067. doi: 10.1038/80992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohler A, Bajorek M, Groll M, Moroder L, Rubin DM, Huber R, Glickman MH, Finley D. The substrate translocation channel of the proteasome. Biochimie. 2001;83:325–332. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(01)01242-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohler A, Cascio P, Leggett DS, Woo KM, Goldberg AL, Finley D. The axial channel of the proteasome core particle is gated by the Rpt2 ATPase and controls both substrate entry and product release. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1143–1152. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00274-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scheffner M, Nuber U, Huibregtse JM. Protein ubiquitination involving an E1-E2-E3 enzyme ubiquitin thioester cascade. Nature. 1995;373:81–83. doi: 10.1038/373081a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hochstrasser M. Ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;30:405–439. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.30.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groll M, Ditzel L, Lowe J, Stock D, Bochtler M, Bartunik HD, Huber R. Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4 A resolution. Nature. 1997;386:463–471. doi: 10.1038/386463a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendil KB, Khan S, Tanaka K. Simultaneous binding of PA28 and PA700 activators to 20 S proteasomes. Biochem J. 1998;332(Pt 3):749–754. doi: 10.1042/bj3320749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nalepa G, Rolfe M, Harper JW. Drug discovery in the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2006;5:596–613. doi: 10.1038/nrd2056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kopp F, Steiner R, Dahlmann B, Kuehn L, Reinauer H. Size and shape of the multicatalytic proteinase from rat skeletal muscle. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;872:253–260. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(86)90278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowe J, Stock D, Jap B, Zwickl P, Baumeister W, Huber R. Crystal structure of the 20S proteasome from the archaeon T. acidophilum at 3.4 A resolution. Science. 1995;268:533–539. doi: 10.1126/science.7725097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pickart CM, Cohen RE. Proteasomes and their kin: proteases in the machine age. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:177–187. doi: 10.1038/nrm1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nandi D, Tahiliani P, Kumar A, Chandu D. The ubiquitin-proteasome system. J Biosci. 2006;31:137–155. doi: 10.1007/BF02705243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters JM, Cejka Z, Harris JR, Kleinschmidt JA, Baumeister W. Structural features of the 26 S proteasome complex. J Mol Biol. 1993;234:932–937. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams J. The proteasome: a suitable antineoplastic target. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:349–360. doi: 10.1038/nrc1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Castro A, Bernis C, Vigneron S, Labbe JC, Lorca T. The anaphase-promoting complex: a key factor in the regulation of cell cycle. Oncogene. 2005;24:314–325. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Escusa S, Laporte D, Massoni A, Boucherie H, Dautant A, Daignan-Fornier B. Skp1-Cullin-F-box-dependent degradation of Aah1p requires its interaction with the F-box protein Saf1p. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20097–20103. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702425200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakayama KI, Nakayama K. Ubiquitin ligases: cell-cycle control and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:369–381. doi: 10.1038/nrc1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bai C, Sen P, Hofmann K, Ma L, Goebl M, Harper JW, Elledge SJ. SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F-box. Cell. 1996;86:263–274. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80098-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skowyra D, Craig KL, Tyers M, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. F-box proteins are receptors that recruit phosphorylated substrates to the SCF ubiquitin-ligase complex. Cell. 1997;91:209–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80403-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zheng N, Schulman BA, Song L, Miller JJ, Jeffrey PD, Wang P, Chu C, Koepp DM, Elledge SJ, Pagano M, Conaway RC, Conaway JW, Harper JW, Pavletich NP. Structure of the Cul1-Rbx1-Skp1-F boxSkp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Nature. 2002;416:703–709. doi: 10.1038/416703a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Carrano AC, Eytan E, Hershko A, Pagano M. SKP2 is required for ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:193–199. doi: 10.1038/12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maki CG, Huibregtse JM, Howley PM. In vivo ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation of p53(1) Cancer Res. 1996;56:2649–2654. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sdek P, Ying H, Chang DL, Qiu W, Zheng H, Touitou R, Allday MJ, Xiao ZX. MDM2 promotes proteasome-dependent ubiquitin-independent degradation of retinoblastoma protein. Mol Cell. 2005;20:699–708. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ying H, Xiao ZX. Targeting retinoblastoma protein for degradation by proteasomes. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:506–508. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.5.2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei W, Ayad NG, Wan Y, Zhang GJ, Kirschner MW, Kaelin WG., Jr Degradation of the SCF component Skp2 in cell-cycle phase G1 by the anaphase-promoting complex. Nature. 2004;428:194–198. doi: 10.1038/nature02381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chellappan SP, Hiebert S, Mudryj M, Horowitz JM, Nevins JR. The E2F transcription factor is a cellular target for the RB protein. Cell. 1991;65:1053–1061. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90557-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Harbour JW, Luo RX, Dei Santi A, Postigo AA, Dean DC. Cdk phosphorylation triggers sequential intramolecular interactions that progressively block Rb functions as cells move through G1. Cell. 1999;98:859–869. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ayad NG, Rankin S, Murakami M, Jebanathirajah J, Gygi S, Kirschner MW. Tome-1, a trigger of mitotic entry, is degraded during G1 via the APC. Cell. 2003;113:101–113. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wan Y, Liu X, Kirschner MW. The anaphase-promoting complex mediates TGF-beta signaling by targeting SnoN for destruction. Mol Cell. 2001;8:1027–1039. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00382-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu G, Glickstein S, Liu W, Fujita T, Li W, Yang Q, Duvoisin R, Wan Y. The anaphase-promoting complex coordinates initiation of lens differentiation. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1018–1029. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bashir T, Dorrello NV, Amador V, Guardavaccaro D, Pagano M. Control of the SCF(Skp2-Cks1) ubiquitin ligase by the APC/C(Cdh1) ubiquitin ligase. Nature. 2004;428:190–193. doi: 10.1038/nature02330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu W, Wu G, Li W, Lobur D, Wan Y. Cdh1-anaphase-promoting complex targets Skp2 for destruction in transforming growth factor beta-induced growth inhibition. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2967–2979. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01830-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen L, Madura K. Increased proteasome activity, ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes, and eEF1A translation factor detected in breast cancer tissue. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5599–5606. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kumatori A, Tanaka K, Inamura N, Sone S, Ogura T, Matsumoto T, Tachikawa T, Shin S, Ichihara A. Abnormally high expression of proteasomes in human leukemic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7071–7075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li B, Dou QP. Bax degradation by the ubiquitin/proteasome-dependent pathway: involvement in tumor survival and progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3850–3855. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070047997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ren S, Smith MJ, Louro ID, McKie-Bell P, Bani MR, Wagner M, Zochodne B, Redden DT, Grizzle WE, Wang N, Smith DI, Herbst RA, Bardenheuer W, Opalka B, Schutte J, Trent JM, Ben-David Y, Ruppert JM. The p44S10 locus, encoding a subunit of the proteasome regulatory particle, is amplified during progression of cutaneous malignant melanoma. Oncogene. 2000;19:1419–1427. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goldberg AL. Protein degradation and protection against misfolded or damaged proteins. Nature. 2003;426:895–899. doi: 10.1038/nature02263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karin M, Cao Y, Greten FR, Li ZW. NF-kappaB in cancer: from innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:301–310. doi: 10.1038/nrc780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schubert U, Anton LC, Gibbs J, Norbury CC, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. Rapid degradation of a large fraction of newly synthesized proteins by proteasomes. Nature. 2000;404:770–774. doi: 10.1038/35008096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang CY, Cusack JC, Jr, Liu R, Baldwin AS., Jr Control of inducible chemoresistance: enhanced anti-tumor therapy through increased apoptosis by inhibition of NF-kappaB. Nat Med. 1999;5:412–417. doi: 10.1038/7410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang HG, Wang J, Yang X, Hsu HC, Mountz JD. Regulation of apoptosis proteins in cancer cells by ubiquitin. Oncogene. 2004;23:2009–2015. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Adams J. The development of proteasome inhibitors as anticancer drugs. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:417–421. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen D, Cui QC, Yang H, Dou QP. Disulfiram, a clinically used anti-alcoholism drug and copper-binding agent, induces apoptotic cell death in breast cancer cultures and xenografts via inhibition of the proteasome activity. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10425–10433. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen D, Daniel KG, Chen MS, Kuhn DJ, Landis-Piwowar KR, Dou QP. Dietary flavonoids as proteasome inhibitors and apoptosis inducers in human leukemia cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005;69:1421–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Traub F, Mengel M, Luck HJ, Kreipe HH, von Wasielewski R. Prognostic impact of Skp2 and p27 in human breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99:185–191. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Myung J, Kim KB, Crews CM. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and proteasome inhibitors. Med Res Rev. 2001;21:245–273. doi: 10.1002/med.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rock KL, Gramm C, Rothstein L, Clark K, Stein R, Dick L, Hwang D, Goldberg AL. Inhibitors of the proteasome block the degradation of most cell proteins and the generation of peptides presented on MHC class I molecules. Cell. 1994;78:761–771. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90462-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dou QP, Goldfarb RH. Bortezomib (millennium pharmaceuticals) IDrugs. 2002;5:828–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Michaelis M, Fichtner I, Behrens D, Haider W, Rothweiler F, Mack A, Cinatl J, Doerr HW, Cinatl J., Jr Anti-cancer effects of bortezomib against chemoresistant neuroblastoma cell lines in vitro and in vivo. Int J Oncol. 2006;28:439–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sartore-Bianchi A, Gasparri F, Galvani A, Nici L, Darnowski JW, Barbone D, Fennell DA, Gaudino G, Porta C, Mutti L. Bortezomib inhibits nuclear factor-kappaB dependent survival and has potent in vivo activity in mesothelioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5942–5951. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Teicher BA, Ara G, Herbst R, Palombella VJ, Adams J. The proteasome inhibitor PS-341 in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2638–2645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Williams S, Pettaway C, Song R, Papandreou C, Logothetis C, McConkey DJ. Differential effects of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib on apoptosis and angiogenesis in human prostate tumor xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:835–843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jagannath S, Durie BG, Wolf J, Camacho E, Irwin D, Lutzky J, McKinley M, Gabayan E, Mazumder A, Schenkein D, Crowley J. Bortezomib therapy alone and in combination with dexamethasone for previously untreated symptomatic multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:776–783. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orlowski RZ, Voorhees PM, Garcia RA, Hall MD, Kudrik FJ, Allred T, Johri AR, Jones PE, Ivanova A, Van Deventer HW, Gabriel DA, Shea TC, Mitchell BS, Adams J, Esseltine DL, Trehu EG, Green M, Lehman MJ, Natoli S, Collins JM, Lindley CM, Dees EC. Phase 1 trial of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with advanced hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2005;105:3058–3065. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Richardson PG, Barlogie B, Berenson J, Singhal S, Jagannath S, Irwin D, Rajkumar SV, Srkalovic G, Alsina M, Alexanian R, Siegel D, Orlowski RZ, Kuter D, Limen-tani SA, Lee S, Hideshima T, Esseltine DL, Kauffman M, Adams J, Schenkein DP, Anderson KC. A phase 2 study of bortezomib in relapsed, refractory myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2609–2617. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Orlowski M, Wilk S. Catalytic activities of the 20 S proteasome, a multicatalytic proteinase complex. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;383:1–16. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Omura S, Fujimoto T, Otoguro K, Matsuzaki K, Moriguchi R, Tanaka H, Sasaki Y. Lactacystin, a novel microbial metabolite, induces neuritogenesis of neuroblastoma cells. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 1991;44:113–116. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.44.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Fenteany G, Standaert RF, Lane WS, Choi S, Corey EJ, Schreiber SL. Inhibition of proteasome activities and subunit-specific amino-terminal threonine modification by lactacystin. Science. 1995;268:726–731. doi: 10.1126/science.7732382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Dick LR, Cruikshank AA, Grenier L, Melandri FD, Nunes SL, Stein RL. Mechanistic studies on the inactivation of the proteasome by lactacystin: a central role for clasto-lactacystin beta-lactone. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7273–7276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kupfahl C, Ruppert T, Dietz A, Geginat G, Hof H. Candida species fail to produce the immunosuppressive secondary metabolite gliotoxin in vitro. FEMS Yeast Res. 2007;7:986–992. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2007.00256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pahl HL, Krauss B, Schulze-Osthoff K, Decker T, Traenckner EB, Vogt M, Myers C, Parks T, Warring P, Muhlbacher A, Czernilofsky AP, Baeuerle PA. The immunosuppressive fungal metabolite gliotoxin specifically inhibits transcription factor NF-kappaB. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1829–1840. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kroll M, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Bachelerie F, Thomas D, Friguet B, Conconi M. The secondary fungal metabolite gliotoxin targets proteolytic activities of the proteasome. Chem Biol. 1999;6:689–698. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reed JC. Mechanisms of apoptosis avoidance in cancer. Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11:68–75. doi: 10.1097/00001622-199901000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wang X. The expanding role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2922–2933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Budd RC. Death receptors couple to both cell proliferation and apoptosis. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:437–441. doi: 10.1172/JCI15077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chaudhary PM, Eby M, Jasmin A, Bookwalter A, Murray J, Hood L. Death receptor 5, a new member of the TNFR family, and DR4 induce FADD-dependent apoptosis and activate the NF-kappaB pathway. Immunity. 1997;7:821–830. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nagata S. Fas ligand-induced apoptosis. Annu Rev Genet. 1999;33:29–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.33.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Friedman J, Xue D. To live or die by the sword: the regulation of apoptosis by the proteasome. Dev Cell. 2004;6:460–461. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00104-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Orlowski RZ. The role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:303–313. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fang S, Jensen JP, Ludwig RL, Vousden KH, Weissman AM. Mdm2 is a RING finger-dependent ubiquitin protein ligase for itself and p53. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8945–8951. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Huang H, Regan KM, Wang F, Wang D, Smith DI, van Deursen JM, Tindall DJ. Skp2 inhibits FOXO1 in tumor suppression through ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1649–1654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406789102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yang T, Buchan HL, Townsend KJ, Craig RW. MCL-1, a member of the BLC-2 family, is induced rapidly in response to signals for cell differentiation or death, but not to signals for cell proliferation. J Cell Physiol. 1996;166:523–536. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199603)166:3<523::AID-JCP7>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhong Q, Gao W, Du F, Wang X. Mule/ARF-BP1, a BH3-only E3 ubiquitin ligase, catalyzes the polyubiquitination of Mcl-1 and regulates apoptosis. Cell. 2005;121:1085–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Perkins ND. Integrating cell-signalling pathways with NF-kappaB and IKK function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:49–62. doi: 10.1038/nrm2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hsu YT, Wolter KG, Youle RJ. Cytosol-to-membrane redistribution of Bax and Bcl-X(L) during apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3668–3672. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dewson G, Snowden RT, Almond JB, Dyer MJ, Cohen GM. Conformational change and mitochondrial translocation of Bax accompany proteasome inhibitor-induced apoptosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemic cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:2643–2654. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.LeBlanc H, Lawrence D, Varfolomeev E, Totpal K, Morlan J, Schow P, Fong S, Schwall R, Sinicropi D, Ashkenazi A. Tumor-cell resistance to death receptor--induced apoptosis through mutational inactivation of the proapoptotic Bcl-2 homolog Bax. Nat Med. 2002;8:274–281. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Walczak H, Krammer PH. The CD95 (APO-1/Fas) and the TRAIL (APO-2L) apoptosis systems. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256:58–66. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Orlowski RZ, Baldwin AS., Jr NF-kappaB as a therapeutic target in cancer. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8:385–389. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4914(02)02375-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Winston JT, Strack P, Beer-Romero P, Chu CY, Elledge SJ, Harper JW. The SCFbeta-TRCP-ubiquitin ligase complex associates specifically with phosphorylated destruction motifs in IkappaBalpha and beta-catenin and stimulates IkappaBalpha ubiquitination in vitro. Genes Dev. 1999;13:270–283. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.3.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Biswas DK, Iglehart JD. Linkage between EGFR family receptors and nuclear factor kappaB (NF-kappaB) signaling in breast cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:645–652. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Coffin JD, Poole TJ. Embryonic vascular development: immunohistochemical identification of the origin and subsequent morphogenesis of the major vessel primordia in quail embryos. Development. 1988;102:735–748. doi: 10.1242/dev.102.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mitchell K, Szekeres C, Milano V, Svenson KB, Nilsen-Hamilton M, Kreidberg JA, DiPersio CM. Alpha3beta1 integrin in epidermis promotes wound angiogenesis and keratinocyte-to-endothelial-cell crosstalk through the induction of MRP3. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:1778–1787. doi: 10.1242/jcs.040956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Folkman J. Angiogenesis in cancer, vascular, rheumatoid and other disease. Nat Med. 1995;1:27–31. doi: 10.1038/nm0195-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Crowther M, Brown NJ, Bishop ET, Lewis CE. Microenvironmental influence on macrophage regulation of angiogenesis in wounds and malignant tumors. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:478–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Maisonpierre PC, Suri C, Jones PF, Bartunkova S, Wiegand SJ, Radziejewski C, Compton D, McClain J, Aldrich TH, Papadopoulos N, Daly TJ, Davis S, Sato TN, Yancopoulos GD. Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science. 1997;277:55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Yoshida S, Ono M, Shono T, Izumi H, Ishibashi T, Suzuki H, Kuwano M. Involvement of interleukin-8, vascular endothelial growth factor, and basic fibroblast growth factor in tumor necrosis factor alpha-dependent angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4015–4023. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.4015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ferrara N, Davis-Smyth T. The biology of vascular endothelial growth factor. Endocr Rev. 1997;18:4–25. doi: 10.1210/edrv.18.1.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Veikkola T, Karkkainen M, Claesson-Welsh L, Alitalo K. Regulation of angiogenesis via vascular endothelial growth factor receptors. Cancer Res. 2000;60:203–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Carmeliet P, Ng YS, Nuyens D, Theilmeier G, Brusselmans K, Cornelissen I, Ehler E, Kakkar VV, Stalmans I, Mattot V, Perriard JC, Dewerchin M, Flameng W, Nagy A, Lupu F, Moons L, Collen D, D’Amore PA, Shima DT. Impaired myocardial angiogenesis and ischemic cardiomyopathy in mice lacking the vascular endothelial growth factor isoforms VEGF164 and VEGF188. Nat Med. 1999;5:495–502. doi: 10.1038/8379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Plate KH, Breier G, Weich HA, Risau W. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a potential tumour angiogenesis factor in human gliomas in vivo. Nature. 1992;359:845–848. doi: 10.1038/359845a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shweiki D, Itin A, Soffer D, Keshet E. Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature. 1992;359:843–845. doi: 10.1038/359843a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pollmann C, Huang X, Mall J, Bech-Otschir D, Naumann M, Dubiel W. The constitutive photomorphogenesis 9 signalosome directs vascular endothelial growth factor production in tumor cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8416–8421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ravi R, Mookerjee B, Bhujwalla ZM, Sutter CH, Artemov D, Zeng Q, Dillehay LE, Madan A, Semenza GL, Bedi A. Regulation of tumor angiogenesis by p53-induced degradation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha. Genes Dev. 2000;14:34–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Shibata A, Nagaya T, Imai T, Funahashi H, Nakao A, Seo H. Inhibition of NF-kappaB activity decreases the VEGF mRNA expression in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2002;73:237–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1015872531675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Strayhorn WD, Wadzinski BE. A novel in vitro assay for deubiquitination of I kappa B alpha. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;400:76–84. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2002.2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Meteoglu I, Erdogdu IH, Meydan N, Erkus M, Barutca S. NF-KappaB expression correlates with apoptosis and angiogenesis in clear cell renal cell carcinoma tissues. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2008;27:53. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-27-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Huang S, Robinson JB, Deguzman A, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Blockade of nuclear factor-kappaB signaling inhibits angiogenesis and tumorigenicity of human ovarian cancer cells by suppressing expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and interleukin 8. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5334–5339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Adams J. Preclinical and clinical evaluation of proteasome inhibitor PS-341 for the treatment of cancer. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2002;6:493–500. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(02)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.LeBlanc R, Catley LP, Hideshima T, Lentzsch S, Mitsiades CS, Mitsiades N, Neuberg D, Goloubeva O, Pien CS, Adams J, Gupta D, Richardson PG, Munshi NC, Anderson KC. Proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibits human myeloma cell growth in vivo and prolongs survival in a murine model. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4996–5000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nawrocki ST, Bruns CJ, Harbison MT, Bold RJ, Gotsch BS, Abbruzzese JL, Elliott P, Adams J, McConkey DJ. Effects of the proteasome inhibitor PS-341 on apoptosis and angiogenesis in orthotopic human pancreatic tumor xenografts. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:1243–1253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sunwoo JB, Chen Z, Dong G, Yeh N, Crowl Bancroft C, Sausville E, Adams J, Elliott P, Van Waes C. Novel proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibits activation of nuclear factor-kappa B, cell survival, tumor growth, and angiogenesis in squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1419–1428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Huanjie Y, Zonder JA, Ping DQ. Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 2009;18:957–971. doi: 10.1517/13543780903002074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Orlowski RZ. The ubiquitin proteasome pathway from bench to bedside. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Prog. 2005:220–225. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2005.1.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Papandreou CN, Daliani DD, Nix D, Yang H, Madden T, Wang X, Pien CS, Millikan RE, Tu SM, Pagliaro L, Kim J, Adams J, Elliott P, Esseltine D, Petrusich A, Dieringer P, Perez C, Logothetis CJ. Phase I trial of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in patients with advanced solid tumors with observations in androgen-independent prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2108–2121. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.02.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Anderson KC, Kyle RA, Dalton WS, Landowski T, Shain K, Jove R, Hazlehurst L, Berenson J. Multiple Myeloma: New Insights and Therapeutic Approaches. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2000:147–165. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2000.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Richardson PG, Hideshima T, Anderson KC. Bortezomib (PS-341): a novel, first-in-class proteasome inhibitor for the treatment of multiple myeloma and other cancers. Cancer Control. 2003;10:361–369. doi: 10.1177/107327480301000502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Delic J, Masdehors P, Omura S, Cosset JM, Dumont J, Binet JL, Magdelenat H. The proteasome inhibitor lactacystin induces apoptosis and sensitizes chemo- and radioresistant human chronic lymphocytic leukaemia lymphocytes to TNF-alpha-initiated apoptosis. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:1103–1107. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Masdehors P, Omura S, Merle-Beral H, Mentz F, Cosset JM, Dumont J, Magdelenat H, Delic J. Increased sensitivity of CLL-derived lymphocytes to apoptotic death activation by the proteasome-specific inhibitor lactacystin. Br J Haematol. 1999;105:752–757. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Nix DPC, Newman R, et al. Clinical development of a proteasome inhibitor, PS-341, for the treatment of cancer. Proc Annu Meet Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2001;20:339. [Google Scholar]

- 128.Oakervee HE, Popat R, Curry N, Smith P, Morris C, Drake M, Agrawal S, Stec J, Schenkein D, Esseltine DL, Cavenagh JD. PAD combination therapy (PS-341/bortezomib, doxorubicin and dexamethasone) for previously untreated patients with multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:755–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster MW, Irwin D, Stadtmauer EA, Facon T, Harousseau JL, Ben-Yehuda D, Lonial S, Goldschmidt H, Reece D, San-Miguel JF, Blade J, Boccadoro M, Cavenagh J, Dalton WS, Boral AL, Esseltine DL, Porter JB, Schenkein D, Anderson KC. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2487–2498. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Curran MP, McKeage K. Bortezomib: a review of its use in patients with multiple myeloma. Drugs. 2009;69:859–888. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200969070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Golden EB, Lam PY, Kardosh A, Gaffney KJ, Cadenas E, Louie SG, Petasis NA, Chen TC, Schonthal AH. Green tea polyphenols block the anticancer effects of bortezomib and other boronic acid-based proteasome inhibitors. Blood. 2009;113:5927–5937. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-171389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kim TY, Park J, Oh B, Min HJ, Jeong TS, Lee JH, Suh C, Cheong JW, Kim HJ, Yoon SS, Park SB, Lee DS. Natural polyphenols antagonize the antimyeloma activity of proteasome inhibitor bortezomib by direct chemical interaction. Br J Haematol. 2009;146:270–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Liu FT, Agrawal SG, Movasaghi Z, Wyatt PB, Rehman IU, Gribben JG, Newland AC, Jia L. Dietary flavonoids inhibit the anticancer effects of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Blood. 2008;112:3835–3846. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-150227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Perrone G, Hideshima T, Ikeda H, Okawa Y, Calabrese E, Gorgun G, Santo L, Cirstea D, Raje N, Chauhan D, Baccarani M, Cavo M, Anderson KC. Ascorbic acid inhibits antitumor activity of bortezomib in vivo. Leukemia. 2009;23:1679–1686. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Yang CH, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Reuben JM, Booser DJ, Pusztai L, Krishnamurthy S, Esseltine D, Stec J, Broglio KR, Islam R, Hortobagyi GN, Cristofanilli M. Bortezomib (VELCADE) in metastatic breast cancer: pharmacodynamics, biological effects, and prediction of clinical benefits. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:813–817. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdj131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Shah MH, Young D, Kindler HL, Webb I, Kleiber B, Wright J, Grever M. Phase II study of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (PS-341) in patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6111–6118. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kondagunta GV, Drucker B, Schwartz L, Bacik J, Marion S, Russo P, Mazumdar M, Motzer RJ. Phase II trial of bortezomib for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3720–3725. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Orlowski RZ, Nagler A, Sonneveld P, Blade J, Hajek R, Spencer A, San Miguel J, Robak T, Dmoszynska A, Horvath N, Spicka I, Sutherland HJ, Suvorov AN, Zhu-ang SH, Parekh T, Xiu L, Yuan Z, Rackoff W, Harousseau JL. Randomized phase III study of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin plus bortezomib compared with bortezomib alone in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma: combination therapy improves time to progression. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3892–3901. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.5460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Berenson JR, Yang HH, Sadler K, Jarutirasarn SG, Vescio RA, Mapes R, Purner M, Lee SP, Wilson J, Morrison B, Adams J, Schenkein D, Swift R. Phase I/II trial assessing bortezomib and melphalan combination therapy for the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:937–944. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Popat R, Oakervee H, Williams C, Cook M, Craddock C, Basu S, Singer C, Harding S, Foot N, Hallam S, Odeh L, Joel S, Cavenagh J. Bortezomib, low-dose intravenous melphalan, and dexamethasone for patients with relapsed multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2009;144:887–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Reece DE, Rodriguez GP, Chen C, Trudel S, Kukreti V, Mikhael J, Pantoja M, Xu W, Stewart AK. Phase I-II trial of bortezomib plus oral cyclophosphamide and prednisone in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4777–4783. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.2372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Kropff M, Bisping G, Schuck E, Liebisch P, Lang N, Hentrich M, Dechow T, Kroger N, Salwender H, Metzner B, Sezer O, Engelhardt M, Wolf HH, Einsele H, Volpert S, Heinecke A, Berdel WE, Kienast J. Bortezomib in combination with intermediate-dose dexamethasone and continuous low-dose oral cyclophosphamide for relapsed multiple myeloma. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:330–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Terpos E, Kastritis E, Roussou M, Heath D, Christoulas D, Anagnostopoulos N, Eleftherakis-Papaiakovou E, Tsionos K, Croucher P, Dimopoulos MA. The combination of bortezomib, melphalan, dexamethasone and intermittent thalidomide is an effective regimen for relapsed/refractory myeloma and is associated with improvement of abnormal bone metabolism and angiogenesis. Leukemia. 2008;22:2247–2256. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Berenson JR, Matous J, Swift RA, Mapes R, Morrison B, Yeh HS. A phase I/II study of arsenic trioxide/bortezomib/ascorbic acid combination therapy for the treatment of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1762–1768. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Fanucchi MP, Fossella FV, Belt R, Natale R, Fidias P, Carbone DP, Govindan R, Raez LE, Robert F, Ribeiro M, Akerley W, Kelly K, Limentani SA, Crawford J, Reimers HJ, Axelrod R, Kashala O, Sheng S, Schiller JH. Randomized phase II study of bortezomib alone and bortezomib in combination with docetaxel in previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5025–5033. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Nam S, Smith DM, Dou QP. Ester bond-containing tea polyphenols potently inhibit proteasome activity in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13322–13330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004209200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Smith DM, Daniel KG, Wang Z, Guida WC, Chan TH, Dou QP. Docking studies and model development of tea polyphenol proteasome inhibitors: applications to rational drug design. Proteins. 2004;54:58–70. doi: 10.1002/prot.10504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Smith DM, Wang Z, Kazi A, Li LH, Chan TH, Dou QP. Synthetic analogs of green tea polyphenols as proteasome inhibitors. Mol Med. 2002;8:382–392. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kuroda Y, Hara Y. Antimutagenic and anticarcinogenic activity of tea polyphenols. Mutat Res. 1999;436:69–97. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(98)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]