Abstract

Bax is kept inactive in the cytosol by refolding its C-terminal transmembrane domain into the hydrophobic binding pocket. Although energetic calculations predicted this conformation to be stable, numerous Bax binding proteins were reported and suggested to further stabilize inactive Bax. Unfortunately, most of them have not been validated in a physiological context on the endogenous level. Here we use gel filtration analysis of the cytosol of primary and established cells to show that endogenous, inactive Bax runs 20–30 kDa higher than recombinant Bax, suggesting Bax dimerization or the binding of a small protein. Dimerization was excluded by a lack of interaction of differentially tagged Bax proteins and by comparing the sizes of dimerized recombinant Bax with cytosolic Bax on blue native gels. Surprisingly, when analyzing cytosolic Bax complexes by high sensitivity mass spectrometry after anti-Bax immunoprecipitation or consecutive purification by gel filtration and blue native gel electrophoresis, we detected only one protein, called p23 hsp90 co-chaperone, which consistently and specifically co-purified with Bax. However, this protein could not be validated as a crucial inhibitory Bax binding partner as its over- or underexpression did not show any apoptosis defects. By contrast, cytosolic Bax exhibits a slight molecular mass shift on SDS-PAGE as compared with recombinant Bax, which suggests a posttranslational modification and/or a structural difference between the two proteins. We propose that in most healthy cells, cytosolic endogenous Bax is a monomeric protein that does not necessarily need a binding partner to keep its pro-apoptotic activity in check.

Keywords: Apoptosis, Cell Death, Mitochondria, Proteomics, shRNA, Bax, Bcl-2 family

Introduction

It has become widely accepted that the pro-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family, Bax and Bak, are crucial for the permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane (MOMP),4 a prerequisite of the release of apoptogenic factors such as cytochrome c from the intermembrane space and a point-of-no-return for caspase-dependent and -independent apoptotic processes (1). Whereas Bak is an integral MOM protein inhibited by pro-survival Bcl-2 proteins (2, 3) and/or voltage-dependent anion channel-2 (4, 5), Bax is soluble and resides inactive in the cytosol or loosely attached to mitochondria (6, 7). In response to various apoptotic stimuli, both Bax and Bak undergo conformational changes (8–10), oligomerize (11, 12), and form proteinaceous (13, 14) or lipidic pores (15, 16) through yet unknown mechanisms (1). These conformational changes occur in the MOM and require a tight cooperation between Bax or Bak, BH3-only proteins, and the lipid bilayer. The current model postulates that some BH3-only proteins such as Bid, Bim, and Puma rapidly translocate to the MOM after their synthesis and/or posttranslational modification (17–19) and then serve as activators of Bax and Bak (20–25). As Bak is already an inserted protein, the role of Bid, Bim, and Puma is probably to disengage Bak from its inhibitors (2, 20), allowing its conformational change and oligomerization. However, Bax needs to first translocate from the cytosol to mitochondria and then to insert into the MOM before activation can take place (26, 27). It is thought that Bid, Bim, and Puma may act as MOM receptors of Bax for this process (21–25). Moreover, components of the TOM complex and endophilin B1/Bif-1 appear to fine-tune Bax insertion and oligomerization (28–30). Recently, Montessuit et al. (16) reported that the fission protein Drp1 further assists Bax oligomerization on the MOM through a GTPase-independent mechanism, probably involving a hemifusion-like membrane remodeling process.

The three-dimensional structure of inactive, soluble Bax revealed that its hydrophobic C-terminal transmembrane and mitochondrial targeting sequence is tugged into a hydrophobic binding pocket (31). This pocket is also present in the pro-survival members of the Bcl-2 family and binds the BH3-domain of BH3-only proteins and perhaps other yet unknown proteins crucial for their function (32, 33). It was, therefore, proposed that Bax is kept in check in the cytosol, because the binding of the C-terminal domain to the hydrophobic pocket prevents both mitochondrial targeting and BH3 peptide binding (31–34). In response to apoptotic stimuli, BH3-only proteins and/or other activating factors would bind to the hydrophobic pocket or an allosteric site of Bax and disengage its C-terminal domain for MOM targeting and conformational change/activation. However, it has remained unclear if additional proteins or posttranslational modifications are needed to stabilize Bax in its inactive cytosolic form and if these regulatory mechanisms would be reverted in apoptotic cells. An astonishingly high number of proteins, such as Ku70 (35), 14-3-3 isoforms (36–38), humanin (39), Bif-1 (40, 41), Pin-1 (42), and the pro-survival Bcl-2 members Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, and Mcl-1 (2) have been independently found to interact with cytosolic Bax and to prevent Bax translocation to mitochondria when overexpressed.

Despite reported evidence for such inhibitory Bax binding partners in the healthy cytosol, direct proof for their necessity has not been demonstrated, at least not in all cells. This might be due to the fact that most Bax binding partners were found under artificial conditions, such as in yeast two-hybrid, interaction cloning or overexpression systems, and thus their endogenous interaction under physiological concentrations has rarely been tested.

In this study we searched for endogenous Bax binding partners in the cytosol of healthy mouse monocytes. For that purpose we used two different purification techniques, co-immunoprecipitations (IP) and a combination of gel filtration, blue native, and SDS-PAGE followed by mass spectrometry analysis of the entire molecular mass range (20–40 kDa) of possible Bax binding partners. We did not find any reported Bax binding partner (also not Bcl-2, Bcl-xL, or Mcl-1) but isolated by both methods a protein, called p23 hsp90 co-chaperone.5 However, this protein did not have any impact on the inactive state of Bax or its localization in the cytosol but may be needed for other, yet unknown cellular functions of cytosolic Bax.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies

Acrylamide and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) were from Bio-Rad. Gel filtration molecular weight markers MW-GF-1000 KIT, β-mercaptoethanol, dithiothreitol (DTT), iodacetamide, Tricine, Bis/Tris, aminocaproic acid, n-octylglucoside, Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250, Etoposide, silver nitrate, and acetonitrile were purchased from Sigma. Triton X-100 was from BDH. CHAPS, protease inhibitor mixture (539131), and λ-phosphatase were obtained from Calbiochem, and interleukin-3 (IL-3) was from PeproTech. The bismaleimidohexane homobifunctional sulfhydryl-reactive cross-linker was purchased from Pierce. Rabbit polyclonal anti-Bax NT and anti-Bak NT were from Millipore, and the mouse monoclonal, conformation-specific Bax antibody 6A7 was from BD Pharmingen. Rabbit polyclonal N-Bax (amino acids 2–14 of mouse Bax) and C-Bax (amino acids 184–192 of mouse Bax) antibodies were produced and purified by Eurogentec. Mouse monoclonal anti-actin and anti-tubulin were from MP Biochemicals, and mouse monoclonal anti-ATPase was from Molecular Probes. Rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-ERK (clone D13.14.4E), rabbit polyclonal anti-Pin-1, and anti-Bcl-x (#2762) were from Cell Signaling. Mouse monoclonal anti-Bcl-x (clone H12) was from Zymed Laboratories Inc.. Mouse monoclonal anti-p23 (JJ3) was from Abcam, rabbit polyclonal anti-p23 from Cayman, and mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG M2, anti-FLAG M2-agarose red beads, and 3×FLAG peptide were from Sigma. Rabbit polyclonal anti-14-3-3-θ and anti-Mcl-1 (S-19) were purchased from Santa Cruz, and mouse monoclonal anti-V5, and anti-myc antibodies were from Invitrogen. Rabbit polyclonal anti-Bif-1/SH3GLB was a kind gift of Marjo Simonen, Novartis, Basle. Ni2+-NTA agarose was obtained from Qiagen. Recombinant human Bax was prepared as described previously (31). Recombinant human His-Bax was kindly provided by Jean-Claude Martinou, Geneva, Switzerland, and recombinant human hexahistidine-tagged p23 was from Cayman.

Cell Culture and Apoptosis Induction

Primary mouse hepatocytes, SW480hBax (overexpressing human Bax), FDM, FDC-P1, and MEF cells were prepared and cultured as previously described (43, 44). Bax/Bak DKO MEFs stably co-expressing FLAG-Bax and myc-Bax were generated as described (34). MEFs deficient for p23 were generated and kindly provided by D. Picard (45). Apoptosis was induced in FDM and FDC-P1 cells by IL-3 withdrawal for 8–24 h and in MEFs by exposure to either 1200 J/m2 UV or treatment with 100 μm etoposide. To quantify apoptosis, cells were spun, washed in PBS, and incubated with 3 μg/ml His-GFP-annexin-V or His-CHERRY-annexin-V and 5 μg/ml propidium iodide in annexin V binding buffer (10 mm Hepes/NaOH, pH 7.4, 140 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm CaCl2) at room temperature for 15 min. 2 × 104 cells were subjected to FACS analysis using a FACSCalibur equipment from BD Biosciences. The data were analyzed with the Cell-Quest program supplied by the manufacturer.

Transfections and Infections

To overexpress the p23 protein, a p23-V5 construct was generated by cloning the 483-bp-long human p23 cDNA (provided by D. Picard) into the pcDNA3.1/V5-His-TOPO vector, yielding p23-V5. FLAG-hBcl-2, FLAG-hBax, FLAG-hBcl-xL, and His-hBak cDNAs (provided by Jean-Claude Martinou, Geneva, Switzerland) were subcloned into the pcDNA3.1 GatewayTM vector (Invitrogen). The plasmids were (co-)transfected into MEF, HEK293T, or FDM cells using SuperFect according to the manufactory protocol (Promega). As a control the pcDNA3.1 GatewayTM empty vector was used. 24–48 h posttransfection a total extract was prepared and used for Western blotting or immunoprecipitations. To underexpress p23 protein, a lentivirus carrying the p23 shRNA (Sigma) was produced. For that purpose a mixture of the shRNA and virus particle was transfected into HEK 293T cells by SuperFect according the manufactory protocol (Qiagen). After 24 h, viral supernatant was harvested and added to MEF or FDM cells for 24 h before antibiotic selection with puromycin to obtain a stable mixed population of p23 knockdown cells. Successful down-regulation was monitored by anti-p23 immunoblotting.

Preparation of Total Extract and Subcellular Fractions

Cells were lysed in IBc buffer (10 mm Tris, pH 7.5, 1 mm EGTA, 200 mm sucrose, plus protease inhibitor mixture) or PBS using a 23-gauche syringe until 50% of the cells were disrupted (46). A postnuclear extract was then centrifuged at 100,000 × g to prepare membrane and cytosolic fractions. The membrane pellet was resuspended in IBc + 1% CHAPS. In some experiments cells were directly lysed in IBc + 1% CHAPS, and insoluble parts were removed by centrifugation (total extract).

Size Exclusion Chromatography

1 mg of total, cytosolic or membrane extracts was applied to a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 column (AEKTA, Amersham Biosciences) equilibrated in the equivalent lysis buffer (IBc). Fractions of 500 μl were collected, and 30 μl of each fraction was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Immunoprecipitations

Cytosolic or membrane fractions were subjected to IP followed by immunoblotting against known protein partners. Briefly, 100–300 μg of precleared lysate (100 μl) was incubated with either anti-Bax or other antibodies on ice for 2 h. 30 μl of a 50% (w/v) protein A-Sepharose slurry was added, and the sample was rotated end-over-end at 4 °C for 1 h. After a brief centrifugation, the beads were washed 3× in lysis buffer and resuspended in SDS-PAGE sample buffer, as described elsewhere (47). Anti-FLAG IPs were performed by incubating 0.6 mg of a total cell extract with anti-FLAG M2-agarose beads for 2 h. The pulldown was washed, eluted with 3×FLAG peptide, and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. His-Bak was pulled down on Ni2+-NTA-agarose beads and eluted with 10–20 mm imidazole. The proteins were either silver-stained as described (48) (for mass spectrometry analysis) or subjected to Western blot analysis.

Western Blotting

30 μg of protein was immunodetected with anti-NT-Bax (1:5000), anti-NT-Bak (1:5000), anti-14-3-3-θ (1:1000), anti-Mcl-1 (1:1000), anti-pERK (1:2000), anti-actin (1:40000), anti-tubulin (1:10000), anti-ATPase (1:10000), anti-Bcl-x (1:1000), anti-Pin-1 (1:1000), anti-p23 (1:1000), anti-Bif-1 (1:50), anti-V5 (1:5000), anti-FLAG M2 (1:5000), or anti-myc (1:2000) primary antibodies followed by peroxidase-coupled, goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories). Immunodetection was performed by ECL (Pierce).

Anderson Gel PAGE

Anderson gels were prepared as previously described (49). They were modified SDS-PAGE, adapted in their acrylamide/bisacrylamide concentrations to obtain an optimal separation of proteins with a small difference in sizes (1–2 kDa).

Blue Native (BN)-PAGE and Immunoblotting

BN electrophoresis was performed according to Wittig et al. (50) and Brookes et al. (51). Briefly, FDM cells were separated into cytosol and CHAPS-solubilized membrane fractions as described. 10% (w/v) of Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 in aminocaproic acid (0.5 m) was added to each fraction, and the fraction was kept on ice for no longer than 30 min before electrophoresis. The proteins (40 μg/lane) were resolved on a 10–16% gradient gel at 80 V, 4 °C overnight. The anode buffer comprised 50 mm Bis/Tris, pH 7.0, and the cathode buffer of 50 mm Tricine, 15 mm Bis/Tris, pH 7.0, and 0.002% Coomassie Blue G-250. The gel was equilibrated in transfer buffer for 30 min, and the proteins were electroblotted to PVDF membrane (Millipore). BN-PAGE was calibrated with the following marker proteins: β-amylase (200 kDa), albumin (66 kDa), ferroxin (40 kDa), and carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa), which were visualized by Coomassie staining. For the second-dimensional SDS-PAGE, a lane from BN-PAGE was cut and incubated in modified SDS sample buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, 190 mm glycine, 1% SDS) followed by migration on a 12.5% SDS-PAGE. Second-dimension gels were electroblotted to a PVDF (Millipore) membrane. For both the one-dimensional BN-PAGE and the two-dimensional BN/SDS-PAGE, immunodetection was performed by SuperSignal chemiluminescence (Pierce).

Protein Preparation for Mass Spectrometric Analysis

For mass spectrometry analysis, a tryptic in-gel digest of the protein samples was performed using a modified protocol published by Shevchenko et al. (52). Sequence grade trypsin (Promega) was used. The samples were diluted to 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate and reduced with 10 mm DTT at 56 °C for 1 h, then carboxyamidomethylated with 55 mm iodoacetamide in the dark for 30 min and digested at 37 °C overnight. The resulting peptides were dried using a SpeedVac and stored at −20 °C until ready to analyze.

MS/MS Measurement and Data Analysis

The Nanoflow-HPLC-MS/MS measurements of the digested protein samples were done using a ion trap-based Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (LTQ-FT) mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany) or an Orbitrap XL (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany) linked to an Ultimate3000 HPLC system (Dionex, Idstein). The HPLC column tips with 75-μm inner diameter were packed with Reprosil-Pur 120 ODS-3 (Dr. Maisch). A gradient of A (0.5% acetic acid (ACS reagent, Sigma) in water) and B (0.5% acetic acid in 80% acetonitrile (HPLC gradient grade, SDS, Peypin, France)) with increasing organic portion was used.

For protein identification a MASCOT-Software (Matrixscience, London, UK) was combined with the NCBI_nr data bank (NCBI). The search parameters were: taxonomy, Metazoa; enzyme, trypsin; m/z, monoisotopisch; mass accuracy for MS ≤ 15 ppm, for MS/MS ≤ 0.8 Da; up to one “missed cleavage”; variable modifications: carbamidomethyl (-Cys), propionamide (-Cys), oxidation (-Met), Gln → pyro-Glu (N-term Gln), Glu → pyro-Glu (N-term Glu)). A protein was considered significant if at least two peptides with the following criterion were found; for a p < 0.05 score value of the peptide indicated identity. In selected cases of Bax-containing gel bands the MASCOT search was extended to cholesteryl- (C-term), farnesyl- (Cys), geranyl- (Cys), myristoyl- (Cys, Lys, N-term), palmitoyl- (Cys, Lys, Ser, Thr, N-term), acetyl- (Lys, N-term), and (di)methyl (Lys, N-term). In the case of acetylations and methylations up to two missed cleavages were allowed.

RESULTS

Cytosolic- and Mitochondria-associated Endogenous Bax Elutes at Higher Molecular Mass after Gel Filtration Chromatography Than Recombinant Bax and Forms Cross-linked Complex of ∼43 kDa

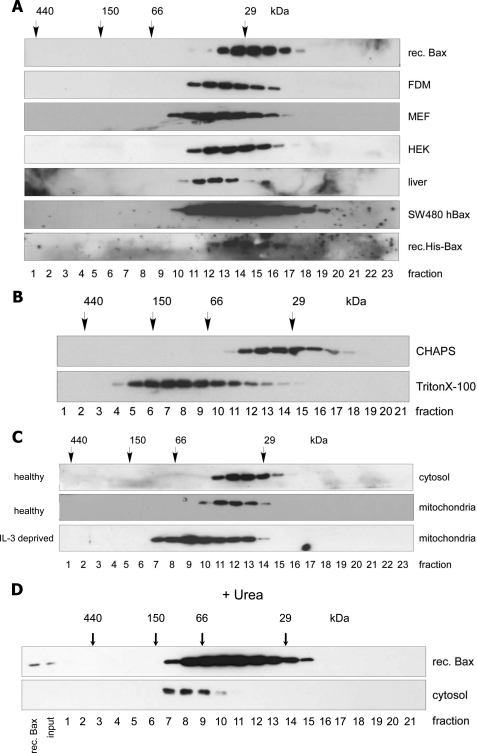

Bax is present as an inactive 21-kDa protein in the cytosol of healthy cells. Indeed, when bacterially expressed (recombinant), untagged or His-tagged human Bax was run on a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 gel filtration column, it eluted in fractions corresponding to molecular masses of 20–30 kDa (Fig. 1A). Surprisingly, this was not the case for endogenous Bax in the cytosol of a variety of human (HEK, SW480hBax) and mouse cell lines (FDM, MEF), including freshly isolated murine liver cells. Here, the elution profile of Bax shifted to molecular masses up to 50 kDa (Fig. 1A). This also occurred in other buffers (such as PBS, data not shown) and was not due to a detergent effect, as our cytosolic extracts did not contain any detergent, and the addition of CHAPS to the cytosolic extract did not change the elution profile of soluble, endogenous Bax (Fig. 1B). The latter result also indicates that CHAPS did not majorly bind to and change the conformation of Bax as otherwise the Bax protein would have migrated differently through the sizing column. By contrast, as previously reported (6, 7), in the presence of a non-ionic detergent such as Triton X-100 or Nonidet P-40, cytosolic Bax changed its conformation and formed high molecular weight complexes of sizes up to 300 kDa (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

On gel filtration chromatography endogenous Bax elutes in bigger complexes than its monomeric state. Shown is anti-Bax Western blot analysis of a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 gel filtration chromatography of recombinant (rec.) Bax or His-Bax or endogenous Bax from the cytosols of FDM, MEF, and HEK cells from the liver tissue as well as from SW480 colon carcinoma cells overexpressing human Bax (A), CHAPS- or Triton X-100-extracted total lysates of FDM cells (B), cytosolic- and CHAPS-extracted mitochondrial fractions of healthy or IL-3-deprived (16 h) FDM cells (C), or recombinant Bax and cytosol from FDM cells treated with 8 m urea buffer (D). 250 μl of 800 ng of recombinant Bax or 1 mg of subcellular fractions were loaded onto the column, and 500-μl fractions were collected. Protein standard markers (29, 66, 150, and 440 kDa) were run in parallel.

In some established cell lines, Bax is not only present in the cytosol but is also loosely attached to mitochondria (53). We, therefore, ran CHAPS-extracted mitochondrial Bax on the same Superdex 200 column and found that its elution profile was similar to that of cytosolic Bax (Fig. 1C). This was different from mitochondrial Bax in IL-3-deprived, apoptotic cells, which formed high molecular mass oligomers (Fig. 1C).

Thus, our data show that in healthy cells endogenous cytosolic and mitochondrial Bax have a similar structure and/or form protein complexes of similar sizes irrespective of the presence of an ionic detergent such as CHAPS. However, upon gel filtration analysis, both species elute at molecular masses of 20–30 kDa higher than recombinant Bax, indicating that they are either present as dimers, have a small protein(s) bound, or adopt in the cellular context a structure that deviates from that of recombinant Bax. Consistent with this notion, cytosolic and recombinant Bax were present in the same fractions when previously denatured in urea, although for both, elution was retarded due to protein unfolding (Fig. 1D). In this case cytosolic Bax would release a potential binding partner and co-migrate with recombinant Bax, but in fractions of higher molecular mass because the Bax protein is unfolded. Moreover, supporting the idea of a binding partner, both cytosolic and mitochondrial Bax formed a specific 43-kDa complex on SDS-PAGE when cross-linked with the bifunctional cross-linker bismaleimidohexane. In response to an apoptotic stimulus (-IL-3) this complex was retained in the cytosol, but in addition, Bax was found in cross-linked oligomers on the mitochondrial membrane as expected from previous work (supplemental Fig. S1).

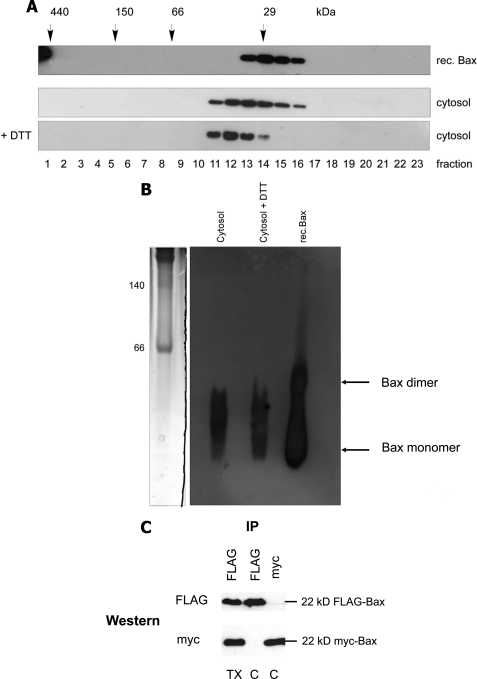

Bax Does Not Form Dimers in Vitro or Inside Healthy Cells

Because the bismaleimidohexane-cross-linked product and the protein complexes eluted from gel filtration had molecular masses reminiscent to Bax dimers, we tested if inactive cytosolic Bax would form dimers. We first considered the possibility that such a dimer was disulfide-linked. However, when the cytosolic lysate of FDM cells was prepared and run on gel filtration in the presence of high amounts of DTT, which reduces S-S bonds, the elution profile of Bax was the same as in the absence of DTT (Fig. 2A). To test if the Bax complexes seen after gel filtration could nevertheless correspond to non-disulfide-linked, dimeric structures, we compared their sizes to those of recombinant Bax on a blue native gel. For that purpose we applied a recombinant Bax sample that was freeze/thawed several times and, therefore, contained Bax in both monomeric and dimeric forms. As shown in Fig. 2B, the sizes of the Bax complexes from the cytosol of FDM cells were clearly smaller than dimeric recombinant Bax, indicating that Bax does not seem to form a dimer in the cytosol of healthy cells. To examine if cytosolic Bax would nevertheless form dimers inside cells, we co-expressed FLAG-Bax and myc-Bax in Bax/Bak DKO MEFs. An anti-FLAG immunoprecipitation of such a cytosol did, however, not reveal any co-immunoprecipitated myc-Bax and vice versa, suggesting that the two differently tagged Bax species do not dimerize in cells (Fig. 2C).

FIGURE 2.

Bax does not form disulfide-linked or other dimers in vitro or inside cells. Shown are anti-Bax Western blot analysis of gel filtration chromatography of recombinant Bax and endogenous Bax in the absence or presence of 50 mm DTT (A) and first dimension of a BN-PAGE comparing the migration of 30 ng of recombinant (rec.) Bax after freeze/thawing to endogenous native Bax complexes from 100 μg FDM cytosol in the absence or presence of 50 mm DTT (B). Coomassie-stained molecular mass markers are shown on the left (140 and 60 kDa). Note that freeze/thawing of recombinant Bax partially generates spontaneous Bax dimers that are different in size from endogenous Bax complexes. In addition, DTT does not change the elution/migration profile of endogenous Bax on gel filtration or BN-PAGE. C, shown is and anti-FLAG or anti-myc Western blot analysis of anti-FLAG or anti-myc immunoprecipitates from the cytosol (C) of Bax/Bak DKO MEFs stably co-expressing FLAG- and myc-tagged human Bax. Note that although each anti-tag IP is very efficient, it does not contain the other tagged Bax species, indicating that FLAG- and myc-Bax do not dimerize. However, as expected, dimerization is observed in the presence of Triton (TX).

Endogenous Cytosolic Bax Runs Differently on Gel Filtration Columns Than Previously Published Bax Binding Partners

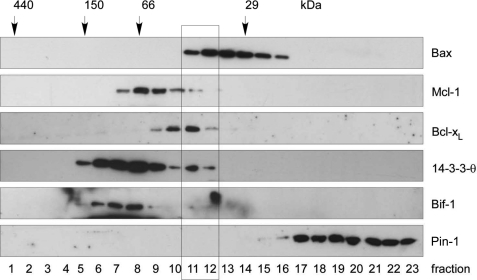

We next investigated if known published Bax binding partners eluted in the same protein complexes after gel filtration chromatography as endogenous cytosolic Bax. Ku70 could be excluded, because its molecular mass of 70 kDa was higher than the highest possible Bax complexes (50 kDa). Moreover, the publication in which Ku70 was claimed to be a cytosolic Bax inhibitor and protector against Bax-mediated cell death (35) has meanwhile been retracted so that this protein can no longer be considered as Bax binding partner (54). On the other hand, the gene for the published Bax binding partner humanin has remained enigmatic (39). The cDNA isolated is 99% identical to mitochondrial 16 S ribosomal RNA (MT-RNR2), which when translated results in a premature stop codon and a slightly shorter peptide lacking the last 3 C-terminal residues (55). We then tested Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, 14-3-3-θ, Bif-1, and Pin-1 for co-migration with Bax in the cytosol of three different cell lines, FDMs (Fig. 3), MEFs (supplemental Fig. S2A), and primary hepatocytes (supplemental Fig. S2B). These proteins had previously been shown to specifically interact with Bax in the cytosol (2, 36–42) and exhibited molecular masses between 20 and 40 kDa that could account for the shift in the molecular mass of Bax to ∼50 kDa upon gel filtration analysis. However, although Bcl-xL and Mcl-1 partially co-eluted with Bax in the upper 1–2 fractions, no consistent migration overlap was seen for 14-3-3-θ, Bif-1, and Pin-1 (Fig. 3 and supplemental Fig. S2, A and B).

FIGURE 3.

Reported potential Bax binding partners elute differently from gel filtration chromatography than cytosolic Bax complexes from FDM cells. Anti-Bax, anti-Mcl-1, anti-Bcl-xL, anti-14-3-3-θ, anti-Bif-1 and anti-Pin-1 Western blot analysis of gel filtration chromatography of the cytosol of FDM cells is shown. 250 μl of 1 mg cytosol in IBC-buffer was loaded onto the column and separated into 500-μl fractions. Note that whereas the elution profile of Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, and 14-3-3-θ partially overlaps with that of Bax, no such overlap is seen with Bif-1 and Pin-1 (rectangle).

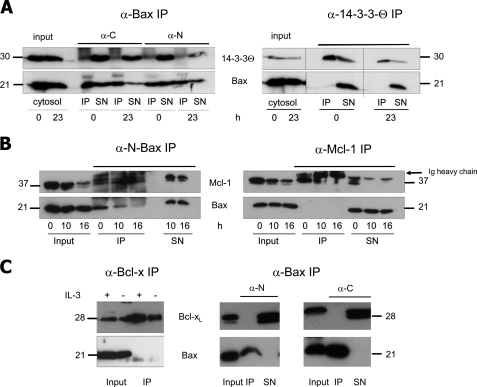

Endogenous Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, or 14-3-3-θ Do Not Co-IP with Cytosolic, Inactive Bax

To verify a potential direct interaction between Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, or 14-3-3-θ with Bax in the two overlapping gel filtration fractions, we performed Bax co-immunoprecipitations with two novel anti-Bax antibodies. So far, Bax antibodies have been mainly generated against the N terminus, in particular toward a conformation-specific epitope, which is only recognized in active Bax (6, 7). We generated polyclonal antibodies against the first 14 amino acids of the N terminus (anti-N-Bax, amino acids 1–14) and the last 9 amino acids of the C terminus (anti-C-Bax, amino acids 184–192) (see supplemental Fig. S3A) assuming that they would also react with inactive Bax. In addition, such antibodies should be optimal tools to pull down Bax binding partners bound to the N terminus (detected via anti-C-Bax) as well as to the C terminus (detected via anti-N-Bax) or elsewhere within the molecule. We first tested the antibodies in IPs of cytosolic and mitochondrial extracts from healthy and IL-3-deprived FDM cells (supplemental Fig. S3B). As a control, we used the commercially available anti-NT-Bax antibody (amino acids 1–21, conformation specific, supplemental Fig. S3A) that mainly, but not exclusively, recognized active Bax. As expected, anti-NT predominantly pulled down active Bax from a mitochondrial CHAPS extract of FDMs deprived of IL-3 for 16 h, although some Bax was also present in the IPs from cytosolic and mitochondrial extracts of healthy cells. By contrast, both anti-N- and anti-C-Bax effectively immunoprecipitated inactive and active Bax from both the cytosol and mitochondrial extracts of healthy and apoptotic cells (supplemental Fig. S3B), indicating that these two antibodies can be used to pull down the inactive, cytosolic form of Bax.

This finding set the stage to test if Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, or 14-3-3-θ were present in the anti-N- or anti-C Bax IPs of cytosolic extracts from healthy and IL-3-deprived FDMs (16, 23 h). As shown in Fig. 4, A–C, this was not the case for any of these proteins irrespective of the anti-Bax antibodies used. We also performed the inverse IPs, i.e. anti-14-3-3-θ, anti-Bcl-x, and anti-Mcl-1 IPs of these extracts, looking for the presence of Bax. Although all these proteins were effectively pulled down, we did not find any Bax associated with them (Fig. 4, A–C). Thus, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1, or 14-3-3-θ could not be verified as specific Bax binding partners of inactive, cytosolic Bax. The same was true for Bif-1, Pin-1, and other isoforms of 14-3-3 (ζ, ϵ, σ) (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Endogenous Bax does not co-IP with 14-3-3, Mcl-1, or Bcl-xL. 100 μg of cytosolic proteins of healthy and IL-3-deprived FDM (A) or FDC-P1 (B and C) cells were immunoprecipitated (IP) with 5 μl of the indicated antibody (Bax, N-Bax, 14-3-3, Mcl-1, Bcl-x). The IPs and resulting supernatants after IP (SN) were loaded on a 15% SDS gel and immunoblotted with anti-Bax (NT) or the indicated antibody. A, anti-N-Bax, anti-C-Bax, or anti-14-3-3 IPs are followed by anti-14-3-3 (upper row) or anti-Bax (lower row) Western blots. B, anti-N-Bax or anti-Mcl-1 IPs are followed by anti-Mcl-1 (upper row) or anti-Bax (lower row) Western blots. C, anti-Bcl-x or anti-N-Bax or anti-C-Bax IPs are followed by Bcl-x (upper row) or anti-Bax (lower row) Western blots. h, hours; Input, cytosol before IP; α-C, antibody against the C terminus of Bax (amino acids 184–192, supplemental Fig. S3); α-N, antibody against the N terminus of Bax (amino acids 2–14, supplemental Fig. S3). In B, the Ig heavy chains run just above Mcl-1. The molecular masses of the respective proteins are indicated.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis of Cytosolic Bax IPs and Bax Protein Complexes Separated by Blue Native Gel Electrophoresis Reveals Only One Specific Bax Binding Partner, p23 hsp90 Co-chaperone

Many proteins reported to interact with inactive Bax could not be tested in our co-IP or gel filtration assays because reliable antibodies were unavailable. We, therefore, decided to purify physiologically relevant protein complexes of endogenous Bax from the cytosol of healthy cells and identify their components by mass spectrometry. For that purpose, two isolation techniques were applied: (i) purification of Bax complexes by gel filtration followed by blue native and SDS gel electrophoresis (GF-BN/SDS-PAGE) and (ii) immunoprecipitation of Bax complexes by affinity-purified anti-N- and anti-C-Bax antibodies. To ensure that the identified Bax binding partners were specific, we included crucial negative controls. Thus, the GF-BN/SDS-PAGE analysis was also performed with cytosolic extracts from Bax−/− cells, as in these cells Bax binding partners should be free or bound to other proteins than Bax. On the other hand, the specificity of anti-Bax IPs was verified with Sepharose beads only, pre-immune IgG, and extracts from Bax−/− cells. Any protein that appeared in these controls by mass spectrometry was discarded as specific Bax binding partner.

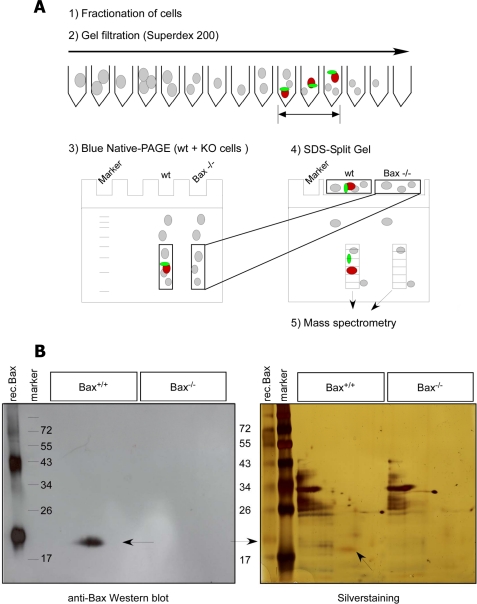

Fig. 5A shows the experimental set up of the combined GF-BN/SDS-PAGE approach. Briefly, Bax-positive fractions (20–50 kDa) of a cytosolic extract of FDM cells applied to Superdex 200 were pooled, concentrated, and applied to a BN-PAGE along with the same fractions from a cytosol of Bax−/− FDMs. Bax protein complexes were localized on BN-PAGE by anti-Bax Western blotting and indeed corresponded to sizes between 20–50 kDa (Fig. 2B), indicating that they had not been disrupted during the purification procedure. The lanes containing the complexes of both Bax+/+ and Bax−/− cytosolic extracts were cut and overlaid on a SDS-split gel to make sure that their components co-migrated (Fig. 5A). The split gel was stained with silver and immunoblotted to nitrocellulose to localize Bax. As shown in Fig. 5B, the protein concentrations of the Bax+/+ and Bax−/− samples were the same, and the proteins were separated on SDS-PAGE in a comparable way. Therefore, differences in mass spectrometry identification between the two samples could not be due to unequal gel loading or running. As proteins bound to Bax should resolve on SDS-PAGE just above the Bax band and need to have molecular masses of 15–35 kDa, the Bax+/+ and Bax−/− lanes were sliced into small gel pieces between 15 and 35 kDa (see standard marker). Each gel piece was then separately digested by trypsin and subjected to LC-MS/MS mass spectrometry.

FIGURE 5.

Gel filtration/blue native/SDS-PAGE approach. A, shown is a scheme of the GF-BN/SDS-PAGE approach for mass spectrometry analysis. To ensure specificity of our purification approach, we ran WT and Bax KO samples in parallel. First, we separated cytosolic Bax complexes by Superdex 200 gel filtration chromatography (1, and 2). The anti-Bax-positive (and corresponding Bax−/−) fractions were collected, concentrated, and loaded on a first-dimensional BN polyacrylamide electrophoresis gel (3). After electrophoresis, gel pieces of both WT and Bax−/− samples corresponding to protein complexes up to 35 kDa were cut, separately overlaid on the same two-dimensional SDS gel (split gel), and run side by side by SDS-PAGE (4) followed by either anti-Bax Western blotting to localize the Bax protein spot (red) or silver staining. By this method putative Bax binding partners (green) run in the same lane as Bax (red) and can be identified by mass spectrometry after cutting this lane between 15 and 35 kDa into similarly sized rectangular pieces and digesting them with trypsin (5). B, anti-Bax Western blot (left) and silver staining (right) of the two-dimensional SDS gel containing Bax+/+ and Bax−/− samples side by side are shown. As a reference, recombinant (rec.) Bax and molecular weight markers were run in the first two lanes of the gel. Arrows indicate the Bax protein.

Supplemental Table 1 shows the specific proteins identified by mass spectrometry in the cytosol of Bax+/+ FDM and liver cells (two independent purifications for each cell line). Most importantly, three peptides of Bax were consistently detected in all WT fractions (supplemental Table 1 and Fig. S4B), indicating that the GF-BN/SDS-PAGE procedure was effective to purify Bax-containing protein complexes and that the gel slices for the identification of their components were correctly chosen. Apart from Bax, the mass spectrometry revealed as potential binding partners hemoglobin, Sjogren's syndrome nuclear autoantigen 1, coiled-coil domain containing protein 43, the RNA-binding protein LUC7-like 2, and p23, a hsp90 co-chaperone (supplemental Tables 1 and 2). However, none of the so-far reported Bax binding partners was found in our mass spectrometry analysis. Before embarking on the validation of the five potential Bax binding partners, we wanted to see if they could also be identified in our anti-Bax immunoprecipitation approach.

We, therefore, performed anti-Bax immunoprecipitations of cytosolic extracts of WT and Bax−/− FDM cells using affinity-purified anti-N and anti-C Bax antibodies. In parallel, the same extracts were incubated with a nonspecific antibody (preimmune serum or Ig) or Sepharose beads only. A silver staining of an SDS-PAGE containing IPs from non-purified and purified anti-C-Bax antibodies revealed that the usage of purified antibodies was necessary to minimize the background of cross-reactive, nonspecific proteins that would ultimately appear in the mass spectrometry analysis (supplemental Fig. S4A). As with the GF-BN/SDS-PAGE technique, the anti-N- and anti-C-Bax IPs of the WT and Bax−/− cytosols and the respective negative controls (IgG, beads) were run on the same gel. The gel was silver-stained, and each lane was equally sliced in the molecular mass area of 15–35 kDa for trypsinization and mass spectrometry analysis. Again four peptides of Bax were significantly and specifically identified by LC-MS/MS (supplemental Table 3 and Fig. S4B), although the Bax protein could not be seen by silver staining (supplemental Fig. S4A). This indicates that the mass spectrometry was sensitive enough to detect reported and novel Bax binding partners provided that they are cleaved by trypsin and interacted with Bax in a 1:1 stoichiometry (what would be expected if they acted as Bax inhibitors). However, none of the putative Bax binding partners identified by the GF-BN/SDS-PAGE technique could be found in anti-Bax IPs, nor did we detect any of the reported Bax binding partners, including Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, 14-3-3 proteins, and others. By contrast, a protein, called cytosolic 3′,5′-nucleotidase was occasionally but inconsistently seen in the anti-Bax IPs but not the beads or IgG controls (supplemental Table 3). Moreover, strikingly, we again specifically identified in both the anti-N and anti-C Bax IPs the p23 hsp90 co-chaperone, already found by the GF-BN/SDS-PAGE method. Supplemental Table 2 summarizes all the p23 peptides that were detected by mass spectrometry in both the GF-BN/SDS-PAGE and IP approaches. Although we also found the p23 protein associated with beads and irrelevant IgG in the last of a total of five IPs (supplemental Table 2, IP-wI7), we proceeded toward its validation as a potential functional Bax binding partner because it was the only specific candidate of all our screens that could account for such a function. Importantly, p23 only co-immunoprecipitated with Bax and not with the related Bcl-2 family proteins Bak, Bcl-xL or Bcl-2 (supplemental Fig. S5, A–D).

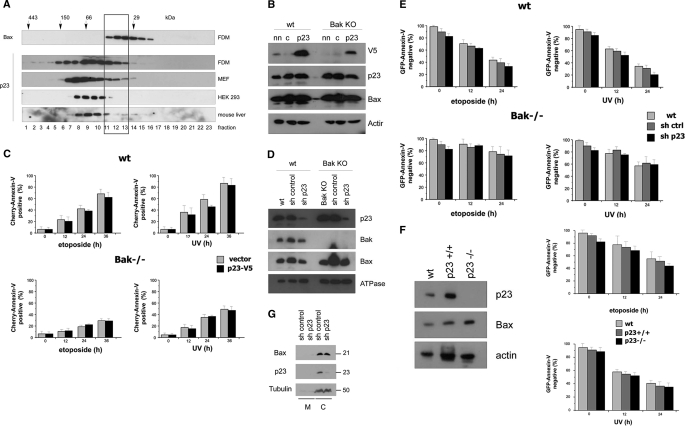

p23 hsp90 Co-chaperone Does Not Have Any Effect on Subcellular Localization and Pro-apoptotic Activity of Bax

We first verified the elution profile of endogenous p23 after Sepharose gel filtration. Although this protein majorly formed high molecular mass complexes of >50 kDa, it indeed partially overlapped with that of Bax in cytosolic extracts of FDM and MEF cells, especially in the fractions corresponding to molecular masses between 30 and 50 kDa (Fig. 6A). This was, however, less the case in cytosolic extracts of HEK 293T and primary mouse hepatocytes, indicating that p23 may not be a general Bax binding partner in all cells (Fig. 6A and supplemental Fig. S2B). We then overexpressed a V5-tagged version of p23 in WT and Bak−/− MEFs. We conceived that if p23 was a specific inhibitor of cytosolic Bax, it would be expected to prevent Bax translocation and cell death, especially in Bak−/− where Bax was the only possible trigger of MOMP. Although we achieved an efficient overexpression of p23-V5 (Fig. 6B), it did not change the apoptosis sensitivity of MEFs toward etoposide or UV (Fig. 6C). Bak−/− MEFs were already well protected against cell death induced by these agents, but p23 overexpression could not further accentuate this protection (Fig. 6C). Conversely, we underexpressed p23 by lentiviral shRNA transduction. This led to a down-regulation of p23 expression by 80–90% in both WT and Bak−/− MEFs (Fig. 6D), but it did not enhance etoposide or UV-induced apoptosis as would be expected from the removal of a major Bax inhibitor (Fig. 6E). Finally, we compared WT and p23−/− MEFs for their apoptosis sensitivity and found that they died similarly in response to etoposide or UV (Fig. 6F). Importantly, the absence of p23 did not change the subcellular distribution of Bax (Fig. 6G), indicating that p23 was not a major sequestering protein for cytosolic Bax. In conclusion, although p23 might be a binding partner of endogenous Bax, its under- or overexpression does not affect the subcellular distribution and pro-apoptotic function of Bax. Thus, based on our proteomics and validation studies, we did not find a binding partner of Bax that is required to maintain its inactive state in the cytosol.

FIGURE 6.

p23 hsp90 co-chaperone partially co-migrates with Bax on gel filtration but does not affect Bax localization and Bax-mediated apoptosis when over- or underexpressed. A, shown is an anti-p23 Western blot analysis of 500-μl fractions of Superdex 200 HR 10/30 gel filtration AEKTA chromatography of 1 mg of cytosol from FDM, MEF, and HEK 293 cells as well as mouse liver. On the top an anti-Bax Western blot of the same fractions of the FDM cytosol is shown. Protein standard markers (29, 66, 150, and 440 kDa) were run in parallel. Note that in FDM and MEF, but not HEK 293 or mouse liver, the elution profile of p23 overlaps in three fractions with that of Bax (rectangle). B, WT and Bak KO MEF were transfected with a p23-V5 (p23) plasmid or an empty vector (c) together with a green fluorescent protein plasmid (GFP) as a control for transfection efficiency. After 24 h, a total cell lysate prepared in IBc + 1% CHAPS was subjected to anti-V5 (detecting overexpressed p23-V5), anti-p23 (detecting both endogenous p23 and overexpressed p23-V5), and anti-Bax Western blot analysis. Anti-actin was used as a loading control. nn, non-transfected control. C, CHERRY-annexin-V FACS analysis of vector control and p23-V5 overexpressing WT and Bak−/− MEFs were treated at 24 h posttransfection with 100 μm etoposide or 1200 J/m2 UV for 0–36 h. Note that p23-V5 overexpression neither inhibited apoptosis in WT MEF, nor further blocked apoptosis in Bak−/− MEF. D, WT and Bak KO MEFs were infected with a lentivirus containing either p23 shRNA or control shRNA and selected for stable shRNA expression with puromycin. A total cell lysate prepared in IBc + 1% CHAPS was subjected to anti-p23, anti-Bak, and anti-Bax Western blot analysis. Anti-ATPase was used as a loading control. Note that the expression of p23 is greatly diminished in the p23 shRNA knockdown cells. E, GFP-annexin-V FACS analysis of untransfected (WT), control shRNA (sh ctrl), and p23 shRNA-transfected WT and Bak−/− MEFs treated with 100 μm etoposide or 1200 J/m2 UV for 0–36 h. Note that p23-V5 underexpression neither accelerated apoptosis in WT nor in Bak−/− MEF. F, anti-p23, anti-Bax, and anti-actin (loading control) Western blot analysis of total extracts of p23+/+ and p23−/− MEFs (left panel) is shown. GFP-annexin-V FACS analysis of the same cells treated with 100 μm etoposide or 1200 J/m2 UV for 0–36 h is shown. WT, another p23+/+ WT control. Note that p23−/− cells die in a similar fashion as p23+/+ cells. The data in C, E, and F are the means of three independent experiments ± S.E., p < 0.02. G, anti-Bax and anti-p23 Western blot analysis of membrane (M) and cytosolic (C) extracts of MEFs infected with control (scrambled) RNA or p23 shRNA as described under D) is shown. Note that the subcellular distribution of Bax and p23 is the same under both conditions. Tubulin serves as cytosol-specific loading marker. The molecular masses of the respective proteins are indicated.

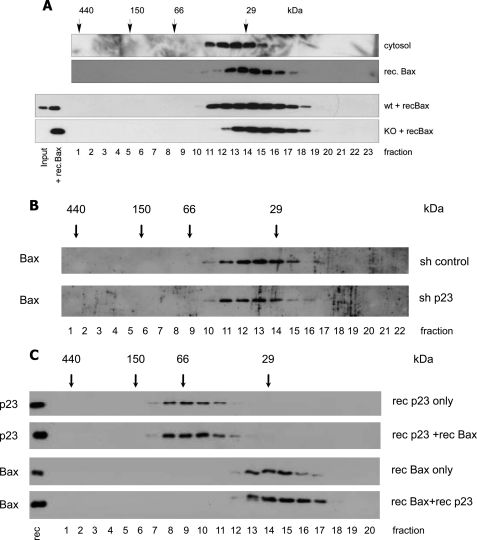

To provide further evidence for this concept, we added recombinant Bax into a cytosolic extract of Bax−/− cells and performed a gel filtration analysis as described above. Our rationale was that if there was a major Bax binding partner in the cytosol, this protein should be free in the Bax−/− cytosol and capture incoming recombinant Bax so that the protein complex would shift to the same elution profile after gel filtration as endogenous Bax in WT cells. However, as shown in Fig. 7A, the migration profile of recombinant Bax was exactly the same irrespective of whether it was run as a pure protein or within a cytosolic extract of Bax−/− cells. Conversely, when we analyzed a cytosol from p23 knockdown cells on gel filtration chromatography, endogenous Bax did not downshift to the fractions of recombinant Bax (Fig. 7B), suggesting that the majority of cytosolic Bax was not bound to p23 or that p23 was substituted by another Bax binding partner when it was down-regulated. Finally recombinant p23 was unable to change the migration pattern of recombinant Bax when the two proteins were co-analyzed on gel filtration (Fig. 7C). This may, however, be due to structural differences or differences in posttranslational modifications of the recombinant as compared with the endogenous Bax and/or p23 proteins. Taken together, our data demonstrate that Bax does not require an obligate binding partner (such as p23) for retention and/or inhibition of its pro-apoptotic activity in the cytosol.

FIGURE 7.

No change in the elution profiles of cytosolic Bax in p23 knockdown cells or of recombinant Bax in the presence of recombinant p23 or when added to a Bax KO cytosol. Recombinant (rec.) Bax added to WT or Bax KO cytosol does not upshift the elution profile to that of endogenous Bax. A, shown is an anti-Bax Western blot analysis of a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 gel filtration AEKTA chromatography of 1 mg of FDM cytosol, 800 ng of recombinant Bax, or 200 ng of recombinant Bax added to 1 mg WT or Bax KO cytosol 30 min before applying to the column. B, analysis was as in A but of the cytosol of MEFs infected with control (scrambled) RNA or p23 shRNA as described in legend to Fig. 6D. C, anti-p23 or anti-Bax Western blot analysis of fractions from a gel filtration chromatography of 1 μg of recombinant His-tagged human p23, 1 μg of recombinant human Bax, or a combination of both. Note that the presence of recombinant p23 does not change the elution pattern of recombinant Bax and vice versa. Protein standard markers (29, 66, 150, and 440 kDa) were run in parallel. The amounts of endogenous (input) and added recombinant Bax or p23 are shown in the first two lanes.

As Compared with Recombinant Bax, Cytosolic Endogenous Bax May Be Structurally Altered Due to Unknown Posttranslational Modification

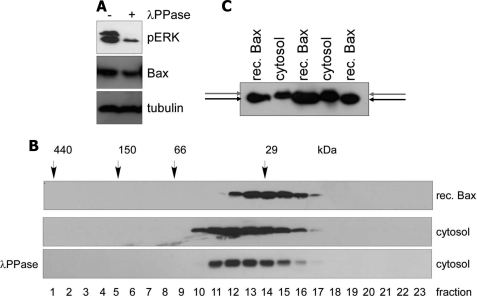

Why then does cytosolic endogenous Bax show other migration behavior on gel filtration than recombinant Bax if it is not due to a binding partner? We considered the possibility that endogenous Bax was structurally different from its recombinant form, for example, due to a posttranslational modification. So far only the NMR structure of bacterially expressed, recombinant Bax has been resolved (31), and we do not know the real three-dimensional structure of inactive endogenous Bax in the cytosol of mammalian cells. We first tested phosphorylation as a candidate modification of cytosolic Bax. After treating a cytosolic FDM extract with λ-phosphatase, a control substrate ERK was entirely dephosphorylated (Fig. 8A). If we assumed that the same happened with cytosolic endogenous Bax, the phosphatase treatment should shift the gel filtration profile to that of recombinant Bax because bacterially expressed Bax cannot be phosphorylated. However, we did not observe any major change in the elution profile of cytosolic Bax before or after phosphatase treatment (Fig. 8B). We then monitored the tryptic peptides of endogenous Bax obtained from both the IP and the GF-BN-SDS-PAGE approaches for the presence of acetylations, O-glycosylations, methylations, and a series of lipidations (palmitoyl, farnesyl, geranyl, myristoyl, cholesteryl moieties) by mass spectrometry analysis. We did not find any solid evidence for these modifications either (data not shown), although we cannot exclude them as completely due to technical limitations. Last, we compared the sizes of cytosolic and recombinant Bax on Anderson SDS-PAGE. This method allows a better separation of proteins exhibiting minor changes in molecular weights due to posttranslational modifications. Indeed, we found that cytosolic Bax migrated slightly slower through Anderson SDS-PAGE than full-length, untagged recombinant Bax (Fig. 8C), which either points to a posttranslational modification or a structural constraint that cannot be relieved by SDS. Importantly, previous treatments with phosphatases or O-glycosidases did not change the migration behavior of cytosolic as compared with recombinant Bax, indicating that endogenous Bax is unlikely to be phosphorylated or O-glycosylated in its inactive state (data not shown). Moreover, the structural change appears to be different from the classical N-terminal change in a conformation associated with Bax activation, as endogenous cytosolic Bax was not immunoprecipitated with the conformation specific Bax antibody 6A7 (supplemental Fig. S6). In summary, our data suggest that Bax does not seem to require a binding partner for its inactive state in the cytosol, but it is most likely structurally altered due to an unidentified posttranslational modification.

FIGURE 8.

Mobility of cytosolic Bax on Anderson SDS-PAGE is slightly retarded as compared with recombinant Bax, but the upshift of Bax on gel filtration is not due to a phosphorylation-dependent structural change. A, the cytosol of MEFs (prepared without phosphatase inhibitors) was treated or not with 4000 units of λ-phosphatase (λ-PPase) at 30 °C for 30 min followed by anti-phospho ERK (pERK, control for efficient dephosphorylation), anti-Bax, and anti-tubulin (loading control) Western blotting. The dephosphorylation of ERK worked efficiently as the upper phosphoprotein band was completely, and the lower markedly diminished. Thus, a putative dephosphorylation of Bax is expected to be as efficient. rec., recombinant. B, the samples in A were applied to Superdex 200 gel filtration chromatography, and the elution profiles of Bax were compared between recombinant Bax and the cytosols treated or not with λ-phosphatase. Note that λ-phosphatase treatment had no major influence on the migration behavior of endogenous Bax. C, an anti-Bax Western blot of 5 ng of recombinant Bax and 30 μg of cytosolic Bax of FDM cells loaded on an Anderson SDS gel shows the slight molecular weight difference between full-length, untagged, recombinant Bax (lower arrow) and endogenous Bax (upper arrow).

DISCUSSION

In this study we used two different proteomics approaches to identify possible binding partners of endogenous, cytosolic, inactive Bax. Given the many potential Bax binding partners so far published, we were surprised that none of these proteins was found either by co-immuoprecipitating Bax using two different anti-Bax antibodies (anti-N, anti-C) or by purifying potential Bax protein complexes by gel filtration and blue native gel electrophoresis followed by separating the components on SDS-PAGE. Both methods have their caveats. IPs are non-quantitative, and therefore, low abundant complexes may not be pulled down. In addition, depending on the stringency conditions (high salt), complexes may fall apart or proteins can non-specifically stick to beads, antibodies, or Bax itself (low salt). To avoid loss of potential Bax binding partners during the experiments, we performed our IPs under low salt conditions but included proper negative controls such as beads-only, irrelevant IgG, and IPs from Bax−/− extracts. Despite these careful controls, none of the reported Bax-binding proteins was found. On the other hand, a purification by gel filtration/blue native gels should include all possible protein complexes in a quantitative way, with the disadvantage of carrying the entire cellular set of cytosolic complexes through the procedure. We, therefore, had to run a Bax−/− sample in parallel to avoid the identification of false positives running at the same location on the SDS-PAGE. This method has already been successfully used to identify binding partners of the BH3-only protein BAD on the mitochondrial membrane (56). Thereby, the authors even had to apply detergent to solubilize the protein complex complexes. This was not the case in our experiments, as our purifications only involved soluble proteins. We can, therefore, exclude that the lack of identification of Bax binding partners was due to a detergent effect.

For some of the reported Bax binding partners we performed reciprocal co-IPs and co-migrations on gel filtration and blue native (data not shown) analysis. Because our anti-Bax antibodies were raised against both extremities of the protein, we should have been able to detect proteins, which bind to either the N or the C terminus of Bax. To our surprise, we did not find interactions between cytosolic Bax and 14-3-3 isoforms, Bif-1, Mcl-1, Bcl-xL, or Pin-1. However, if they had been real Bax binding partners, we would have expected to identify them by our sensitive mass spectrometry. Moreover, if these proteins were all required to keep Bax in check, they would need to form a protein complex much higher than 50 kDa. The interaction of 14-3-3 with Bax depends on phosphoserines or phosphothreonines (57). But we did not obtain any evidence that cytosolic, inactive Bax is phosphorylated as far as we can say from phosphatase treatments (Fig. 8A), shifts in complexes by gel filtration (Fig. 8B), and second-dimension gel (data not shown) analysis. Apart from 14-3-3-θ (36) we also tested other 14-3-3 isoforms (14-3-3ζ and 14-3-3σ) (38) for possible Bax interactions but did not find any. Bif-1 has been either described as a Bax inhibitor (41) or sensitizer of Bax activation (40), but we did not see any elution overlap of this protein with Bax upon gel filtration. A bit unexpected was the lack of interaction between Bax and soluble forms of Bcl-2-like survival factors. Whereas Bcl-2 is an entirely membrane-bound protein (58), parts of Bcl-xL or Mcl-1 can reside in the cytoplasm (6, 59, 60). However, an interaction between these proteins and Bax in a soluble form has been a matter of debate (1). Although active, conformationally altered Bax is likely to interact with Bcl-2-like survival factors on the mitochondrial membrane because its BH3-domain is accessible to bind to the hydrophobic pocket, it is not yet clear how a cytosolic Bax, whose BH3 domain and binding pocket are both inaccessible can interact with Bcl-xL or Mcl-1. Before a co-crystallization of these proteins is performed, we will not know what such an interaction looks like. We suggest that whenever interactions between Bax and Bcl-2/xL or Mcl-1 are detected by co-IPs or FRET in healthy cells, they reflect partially active Bax, which has to bind to endogenous Bcl-2 survival factors to prevent fortuitous MOMP and apoptosis. Thus, we do not think that the major inhibitor of soluble Bax in healthy cells is Bcl-2 or any other anti-apoptotic members of this family. This accounts for both the cytosolic as well as the loosely mitochondria-associated Bax, which is often seen in cultured, highly passaged cells in vitro (53). Rather, Bax is kept inactive by folding back its C-terminal targeting and mitochondrial insertion sequence in its hydrophobic binding pocket (31).

The question arises of how Bax gets activated and recruited to the mitochondrial membrane in response to apoptotic stimuli. Initially it was believed that the major activation step occurs in the cytoplasm, such that activated BH3-only proteins or other cellular factors would bind to the hydrophobic pocket of Bax, dislodging its C-terminal MOM targeting sequence (1, 61). This does not seem to be the case for the following reasons. (i) After apoptotic stimulation, most if not all BH3-only proteins rapidly translocate to mitochondria or, if already present there, get activated on the MOM (17–19). There is no evidence that they act in the cytosol, as removing their C-terminal targeting sequences greatly diminishes their pro-apoptotic potential (17–19). (ii) A recent study by Lovell et al. (17) showed that Bax activation occurs on the MOM by an ordered series of events involving tBid membrane insertion followed by its interaction with Bax causing Bax membrane insertion, oligomerization, and MOMP. Therefore, although it is still unclear if BH3-only proteins directly interact with Bax (21–25) or bind to the hydrophobic pocket of Bcl-2 to release Bax activators (20), it has become evident that their purpose is not to activate Bax in the cytosol but to make the MOM susceptible for insertion and activation of Bax (17–19). One could then consider a model in which these changes on the MOM shift the equilibrium of soluble and membrane-associated Bax toward the latter, facilitating its activation on the MOM.

Our starting point for possible Bax binding partners was the finding that Bax eluted in gel filtration fractions, which corresponded to molecular masses higher than its monomeric state (40–50 kDa instead of 22 kDa). Cross-linking by bismaleimidohexane also revealed a Bax band of ∼43 kDa in both the healthy cytosol and on mitochondria. We could exclude that the molecular mass shift was due to Bax homodimerization based on DTT experiments and comparing the size of endogenous Bax complexes with that of dimerized recombinant Bax on blue native gels. Moreover, differently tagged Bax proteins did not co-IP from a cytosolic extract. The only protein that we consistently identified as a Bax interaction partner by both co-IP and gel filtration/blue native techniques was p23 hsp90 co-chaperone (46). This protein is widely expressed in all mouse tissues although to a lesser extent in muscle and intestine (62). We validated that p23 partially co-migrated with Bax immunoreactivity in the range of 40–50 kDa and co-immunoprecipitated with Bax, at least in some cell types (Fig. 6A, supplemental Figs. S2B and S5D). Moreover, the interaction of p23 with Bax was specific, as it did not co-immunoprecipitate with overexpressed FLAG-Bcl-2, FLAG-Bcl-xL, or His-Bak (supplemental Fig. S5, A–D) and was not found in the interactome of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, which we recently identified in our laboratory (data not shown). However, although part of the p23 protein bound to Bax, it was not required for Bax inactivation in the cytosol as its over- or underexpression did not change the subcellular distribution of Bax or the sensitivity of cells to various apoptotic stimuli (Fig. 6, C–G). This could be due to other cytosolic Bax binding partners that substitute for p23 (Fig. 7B), although we have not found such a protein in our mass spectrometry analysis.

What might p23 then be used for? Because p23 is a co-chaperone, it may sustain the folding of Bax or protect the C-terminal hydrophobic region of Bax without affecting its activity. In this case, it would interact with Bax only transiently and in a non-stoichiometric fashion so that most of the p23 protein would be bound to other partners (as seen by gel filtration in Fig. 6A). This would explain why recombinant Bax mixed with a Bax−/− cytosol did not run in complexes as high as endogenous Bax (Fig. 7A) because p23 may be bound to other proteins and not be available for Bax binding. Alternatively, p23 might be a binding partner for another function of Bax. There is increasing evidence that Bcl-2 family members can perform so-called “night” actions, such as regulating mitochondrial fission/fusion, cytoskeletal rearrangements, metabolism, nuclear transport, or the cell cycle, which are different from the usual “day” actions of apoptosis regulation (63–65).

Could the molecular mass shift of Bax on gel filtration analysis be explained by another mechanism than binding to specific low molecular weight proteins? One possibility may be posttranslational modifications. We did not obtain any evidence by phosphatase treatment and mass spectrometry analysis that cytosolic Bax was either phosphorylated, methylated, acetylated, O-glycosylated, or lipidated. Some lipid modifications such as the covalent addition of diacylglycerol, ceramides, or cardiolipin to Bax could not be analyzed because of the unknown length of fatty acids in these molecules. However, we detected a slight molecular weight shift on Anderson gels that is indicative of some sort of posttranslational modification. This modification cannot account for a higher elution profile of Bax on gel filtration, but it may trigger a conformational change of Bax so that it migrated differently. Interestingly, previous publications revealed possible Bax phosphorylations at either Ser-184 (8, 66) or Thr-167 (42). In the former case it was shown that phosphorylation of Ser-184, which occurs in the C-terminal targeting domain, might be responsible for unleashing the C terminus and, therefore, targeting Bax to the MOM. In inactive Bax, Ser-184 would be dephosphorylated, which is consistent with our data. On the other hand, Thr-167 was phosphorylated by ERK kinase to allow the binding of the prolyl cis-trans isomerase Pin-1 as a stabilizer of Bax structure around Pro-168 (an amino acid just before the C terminus that may undergo cis-trans isomerization) in healthy primary eosinophils (34, 42). Although this might be an important mechanism to keep Bax in check in these primary cells, we did not obtain any evidence for Thr-167 phosphorylation or Pin-1 binding to Bax in co-IPs or co-migrations on gel filtration of the cytosols of monocytes, MEFs, or even primary hepatocytes. This indicates that the Pin-1/Bax interaction may not be a general mechanism to keep Bax in its inactive state. Instead, we propose that in most cases Bax does not require a binding partner to keep it in check in the cytosol of a healthy cell. It may, however, be regulated by an as yet unidentified posttranslational modification that changes the Bax structure so that it runs anomalously on gel filtration (inconsistent with the molecular mass of its monomeric state). So far only the NMR structure of the bacterially expressed Bax protein has been unveiled (31). This might be different from the crystal structure of endogenous eukaryotic Bax. Although challenging, it will be very useful to purify Bax from a eukaryotic overexpression system to determine its exact native structure in mammalian cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Didier Picard for the p23 cDNA and p23−/− MEFs, Andrew Gilmore for testing p23 in an anoikis model system, Jean-Claude Martinou for recombinant His-Bax and the His-Bak cDNA, Geoff Thompson and Ahmad Wardak for technical assistance with recombinant human Bax preparation, Paul Ekert for the FDM cells, and Marjo Simonen for the anti-Bif-1 antibody.

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BO-1933) (to S. V. and C. B.) as well as by the Spemann Graduate School of Biology and Medicine (SGBM, GSC-4; to S. V. and N. R.) and the Cluster BIOSS (EXC-294; to S.V.) funded by the Excellence Initiative of the German Federal and State Governments.

This article contains supplemental Experimental Procedures, Figs. S1–S6, and Tables S1–S3.

The approved symbol from the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (HGNC) of p23 hsp90 co-chaperone is PTGES3.

- MOMP

- mitochondrial outer membrane (MOM) permeability

- BH

- Bcl-2 homology

- IP

- immunoprecipitations

- MEF

- mouse embryo fibroblasts

- BN

- blue native

- GF

- gel filtration

- FDM

- murine factor-dependent monocytes

- FDC-P1

- murine non-tumorigenic factor-dependent diploid myeloid progenitor cells

- NT

- N-terminal.

REFERENCES

- 1. Youle R. J., Strasser A. (2008) The BCL-2 protein family. Opposing activities that mediate cell death. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 47–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Willis S. N., Chen L., Dewson G., Wei A., Naik E., Fletcher J. I., Adams J. M., Huang D. C. (2005) Pro-apoptotic Bak is sequestered by Mcl-1 and Bcl-xL, but not Bcl-2, until displaced by BH3-only proteins. Genes Dev. 19, 1294–1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jeong S. Y., Gaume B., Lee Y. J., Hsu Y. T., Ryu S. W., Yoon S. H., Youle R. J. (2004) Bcl-x(L) sequesters its C-terminal membrane anchor in soluble, cytosolic homodimers. EMBO J. 23, 2146–2155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cheng E. H., Sheiko T. V., Fisher J. K., Craigen W. J., Korsmeyer S. J. (2003) VDAC2 inhibits BAK activation and mitochondrial apoptosis. Science 301, 513–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Setoguchi K., Otera H., Mihara K. (2006) Cytosolic factor- and TOM-independent import of C-tail-anchored mitochondrial outer membrane proteins. EMBO J. 25, 5635–5647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hsu Y. T., Wolter K. G., Youle R. J. (1997) Cytosol-to-membrane redistribution of Bax and Bcl-X(L) during apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 3668–3672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hsu Y. T., Youle R. J. (1998) Bax in murine thymus is a soluble monomeric protein that displays differential detergent-induced conformations. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 10777–10783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nechushtan A., Smith C. L., Hsu Y. T., Youle R. J. (1999) Conformation of the Bax C terminus regulates subcellular location and cell death. EMBO J. 18, 2330–2341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Desagher S., Osen-Sand A., Nichols A., Eskes R., Montessuit S., Lauper S., Maundrell K., Antonsson B., Martinou J. C. (1999) Bid-induced conformational change of Bax is responsible for mitochondrial cytochrome c release during apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 144, 891–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Griffiths G. J., Dubrez L., Morgan C. P., Jones N. A., Whitehouse J., Corfe B. M., Dive C., Hickman J. A. (1999) Cell damage-induced conformational changes of the pro-apoptotic protein Bak in vivo precede the onset of apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 144, 903–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Antonsson B., Montessuit S., Lauper S., Eskes R., Martinou J. C. (2000) Bax oligomerization is required for channel-forming activity in liposomes and to trigger cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Biochem. J. 345, 271–278 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mikhailov V., Mikhailova M., Degenhardt K., Venkatachalam M. A., White E., Saikumar P. (2003) Association of Bax and Bak homo-oligomers in mitochondria. Bax requirement for Bak reorganization and cytochrome c release. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 5367–5376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jürgensmeier J. M., Xie Z., Deveraux Q., Ellerby L., Bredesen D., Reed J. C. (1998) Bax directly induces release of cytochrome c from isolated mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 4997–5002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kuwana T., Mackey M. R., Perkins G., Ellisman M. H., Latterich M., Schneiter R., Green D. R., Newmeyer D. D. (2002) Bid, Bax, and lipids cooperate to form supramolecular openings in the outer mitochondrial membrane. Cell 111, 331–342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Basañez G., Nechushtan A., Drozhinin O., Chanturiya A., Choe E., Tutt S., Wood K. A., Hsu Y., Zimmerberg J., Youle R. J. (1999) Bax, but not Bcl-xL, decreases the lifetime of planar phospholipid bilayer membranes at subnanomolar concentrations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 5492–5497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Montessuit S., Somasekharan S. P., Terrones O., Lucken-Ardjomande S., Herzig S., Schwarzenbacher R., Manstein D. J., Bossy-Wetzel E., Basañez G., Meda P., Martinou J. C. (2010) Membrane remodeling induced by the dynamin-related protein Drp1 stimulates Bax oligomerization. Cell 142, 889–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lovell J. F., Billen L. P., Bindner S., Shamas-Din A., Fradin C., Leber B., Andrews D. W. (2008) Membrane binding by tBid initiates an ordered series of events culminating in membrane permeabilization by Bax. Cell 135, 1074–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Weber A., Paschen S. A., Heger K., Wilfling F., Frankenberg T., Bauerschmitt H., Seiffert B. M., Kirschnek S., Wagner H., Häcker G. (2007) BimS-induced apoptosis requires mitochondrial localization but not interaction with anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins. J. Cell Biol. 177, 625–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Paschen S. A., Weber A., Häcker G. (2007) Mitochondrial protein import. A matter of death? Cell Cycle 6, 2434–2439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Willis S. N., Fletcher J. I., Kaufmann T., van Delft M. F., Chen L., Czabotar P. E., Ierino H., Lee E. F., Fairlie W. D., Bouillet P., Strasser A., Kluck R. M., Adams J. M., Huang D. C. (2007) Apoptosis initiated when BH3 ligands engage multiple Bcl-2 homologs, not Bax or Bak. Science 315, 856–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kuwana T., Bouchier-Hayes L., Chipuk J. E., Bonzon C., Sullivan B. A., Green D. R., Newmeyer D. D. (2005) BH3 domains of BH3-only proteins differentially regulate Bax-mediated mitochondrial membrane permeabilization both directly and indirectly. Mol. Cell 17, 525–535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim H., Rafiuddin-Shah M., Tu H. C., Jeffers J. R., Zambetti G. P., Hsieh J. J., Cheng E. H. (2006) Hierarchical regulation of mitochondrion-dependent apoptosis by BCL-2 subfamilies. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1348–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Certo M., Del Gaizo Moore V., Nishino M., Wei G., Korsmeyer S., Armstrong S. A., Letai A. (2006) Mitochondria primed by death signals determine cellular addiction to antiapoptotic BCL-2 family members. Cancer Cell 9, 351–365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gavathiotis E., Suzuki M., Davis M. L., Pitter K., Bird G. H., Katz S. G., Tu H. C., Kim H., Cheng E. H., Tjandra N., Walensky L. D. (2008) BAX activation is initiated at a novel interaction site. Nature 455, 1076–1081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gallenne T., Gautier F., Oliver L., Hervouet E., Noël B., Hickman J. A., Geneste O., Cartron P. F., Vallette F. M., Manon S., Juin P. (2009) Bax activation by the BH3-only protein Puma promotes cell dependence on antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family members. J. Cell Biol. 185, 279–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Goping I. S., Gross A., Lavoie J. N., Nguyen M., Jemmerson R., Roth K., Korsmeyer S. J., Shore G. C. (1998) Regulated targeting of BAX to mitochondria. J. Cell Biol. 143, 207–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wolter K. G., Hsu Y. T., Smith C. L., Nechushtan A., Xi X. G., Youle R. J. (1997) Movement of Bax from the cytosol to mitochondria during apoptosis. J. Cell Biol. 139, 1281–1292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bellot G., Cartron P. F., Er E., Oliver L., Juin P., Armstrong L. C., Bornstein P., Mihara K., Manon S., Vallette F. M. (2007) TOM22, a core component of the mitochondria outer membrane protein translocation pore, is a mitochondrial receptor for the pro-apoptotic protein Bax. Cell Death Differ. 14, 785–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ott M., Norberg E., Walter K. M., Schreiner P., Kemper C., Rapaport D., Zhivotovsky B., Orrenius S. (2007) The mitochondrial TOM complex is required for tBid/Bax-induced cytochrome c release. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 27633–27639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Etxebarria A., Terrones O., Yamaguchi H., Landajuela A., Landeta O., Antonsson B., Wang H. G., Basañez G. (2009) Endophilin B1/Bif-1 stimulates BAX activation independently from its capacity to produce large scale membrane morphological rearrangements. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 4200–4212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Suzuki M., Youle R. J., Tjandra N. (2000) Structure of Bax. Coregulation of dimer formation and intracellular localization. (2000) Cell 103, 645–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sattler M., Liang H., Nettesheim D., Meadows R. P., Harlan J. E., Eberstadt M., Yoon H. S., Shuker S. B., Chang B. S., Minn A. J., Thompson C. B., Fesik S. W. (1997) Structure of Bcl-xL-Bak peptide complex. Recognition between regulators of apoptosis. Science 275, 983–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liu X., Dai S., Zhu Y., Marrack P., Kappler J. W. (2003) The structure of a Bcl-xL/Bim fragment complex. Implications for Bim function. Immunity. 19, 341–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schinzel A., Kaufmann T., Schuler M., Martinalbo J., Grubb D., Borner C. (2004) Conformational control of Bax localization and apoptotic activity by Pro-168. J. Cell Biol. 164, 1021–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sawada M., Sun W., Hayes P., Leskov K., Boothman D. A., Matsuyama S. (2003) Ku70 suppresses the apoptotic translocation of Bax to mitochondria. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 320–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nomura M., Shimizu S., Sugiyama T., Narita M., Ito T., Matsuda H., Tsujimoto Y. (2003) 14-3-3 Interacts directly with and negatively regulates pro-apoptotic Bax. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 2058–2065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tsuruta F., Sunayama J., Mori Y., Hattori S., Shimizu S., Tsujimoto Y., Yoshioka K., Masuyama N., Gotoh Y. (2004) JNK promotes Bax translocation to mitochondria through phosphorylation of 14-3-3 proteins. EMBO J. 23, 1889–1899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Samuel T., Weber H. O., Rauch P., Verdoodt B., Eppel J. T., McShea A., Hermeking H., Funk J. O. (2001) The G2/M regulator 14-3-3δ prevents apoptosis through sequestration of Bax. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 45201–45206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Guo B., Zhai D., Cabezas E., Welsh K., Nouraini S., Satterthwait A. C., Reed J. C. (2003) Humanin peptide suppresses apoptosis by interfering with Bax activation. Nature 423, 456–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cuddeback S. M., Yamaguchi H., Komatsu K., Miyashita T., Yamada M., Wu C., Singh S., Wang H. G. (2001) Molecular cloning and characterization of Bif-1. A novel Src homology 3 domain-containing protein that associates with Bax. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 20559–20565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pierrat B., Simonen M., Cueto M., Mestan J., Ferrigno P., Heim J. (2001) SH3GLB, a new endophilin-related protein family featuring an SH3 domain. Genomics 71, 222–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shen Z. J., Esnault S., Schinzel A., Borner C., Malter J. S. (2009) The peptidyl-prolyl isomerase Pin1 facilitates cytokine-induced survival of eosinophils by suppressing Bax activation. Nat. Immunol. 10, 257–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Oberle C., Huai J., Reinheckel T., Tacke M., Rassner M., Ekert P. G., Buellesbach J., Borner C. (2010) Lysosomal membrane permeabilization and cathepsin release is a Bax/Bak-dependent, amplifying event of apoptosis in fibroblasts and monocytes. Cell Death Differ. 17, 1167–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Walter D., Schmich K., Vogel S., Pick R., Kaufmann T., Hochmuth F. C., Haber A., Neubert K., McNelly S., von Weizsäcker F., Merfort I., Maurer U., Strasser A., Borner C. (2008) Switch from type II to I Fas/CD95 death signaling on in vitro culturing of primary hepatocytes. Hepatology 48, 1942–1953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Grad I., McKee T. A., Ludwig S. M., Hoyle G. W., Ruiz P., Wurst W., Floss T., Miller C. A., 3rd, Picard D. (2006) The Hsp90 cochaperone p23 is essential for perinatal survival. Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 8976–8983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Frezza C., Cipolat S., Scorrano L. (2007) Organelle isolation. Functional mitochondria from mouse liver, muscle, and cultured fibroblasts. Nat. Protoc. 2, 287–295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ekert P. G., Jabbour A. M., Manoharan A., Heraud J. E., Yu J., Pakusch M., Michalak E. M., Kelly P. N., Callus B., Kiefer T., Verhagen A., Silke J., Strasser A., Borner C., Vaux D. L. (2006) Cell death provoked by loss of interleukin-3 signaling is independent of Bad, Bim, and PI 3-kinase but depends in part on Puma. Blood 108, 1461–1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Blum H., Beier H., Gross H. J. (1987) Improved silver staining of plant proteins, RNA and DNA in polyacrylamide gels. Electrophoresis 8, 93–99 [Google Scholar]

- 49. Anderson C. W., Baum P. R., Gesteland R. F. (1973) Processing of adenovirus 2-induced proteins. J. Virol. 12, 241–252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wittig I., Braun H. P., Schägger H. (2006) Blue native PAGE. Nat. Protoc. 1, 418–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Brookes P. S., Pinner A., Ramachandran A., Coward L., Barnes S., Kim H., Darley-Usmar V. M. (2002) High throughput two-dimensional blue-native electrophoresis. A tool for functional proteomics of mitochondria and signaling complexes. Proteomics 2, 969–977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shevchenko A., Wilm M., Vorm O., Mann M. (1996) Mass spectrometric sequencing of proteins silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. Anal. Chem. 68, 850–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Antonsson B. (2001) Bax and other pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family “killer proteins” and their victim the mitochondrion. Cell Tissue Res. 306, 347–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Sawada M., Sun W., Hayes P., Leskov K., Boothman D. A., Matsuyama S. (2007) Retractions. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tajima H., Niikura T., Hashimoto Y., Ito Y., Kita Y., Terashita K., Yamazaki K., Koto A., Aiso S., Nishimoto I. (2002) Evidence for in vivo production of Humanin peptide, a neuroprotective factor against Alzheimer disease-related insults. Neurosci. Lett. 324, 227–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Danial N. N., Gramm C. F., Scorrano L., Zhang C. Y., Krauss S., Ranger A. M., Datta S. R., Greenberg M. E., Licklider L. J., Lowell B. B., Gygi S. P., Korsmeyer S. J. (2003) BAD and glucokinase reside in a mitochondrial complex that integrates glycolysis and apoptosis. Nature 424, 952–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Darling D. L., Yingling J., Wynshaw-Boris A. (2005) Role of 14-3-3 proteins in eukaryotic signaling and development. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 68, 281–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Kaufmann T., Schlipf S., Sanz J., Neubert K., Stein R., Borner C. (2003) Characterization of the signal that directs Bcl-x(L), but not Bcl-2, to the mitochondrial outer membrane. J. Cell Biol. 160, 53–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Nijhawan D., Fang M., Traer E., Zhong Q., Gao W., Du F., Wang X. (2003) Elimination of Mcl-1 is required for the initiation of apoptosis following ultraviolet irradiation. Genes Dev. 17, 1475–1486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hausmann G., O'Reilly L. A., van Driel R., Beaumont J. G., Strasser A., Adams J. M., Huang D. C. (2000) Pro-apoptotic apoptosis protease-activating factor 1 (Apaf-1) has a cytoplasmic localization distinct from Bcl-2 or Bcl-x(L). J. Cell Biol. 149, 623–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Borner C. (2003) The Bcl-2 protein family. Sensors and checkpoints for life-or-death decisions. Mol. Immunol. 39, 615–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lee J., Kim H. J., Moon J. A., Sung Y. H., Baek I. J., Roh J. I., Ha N. Y., Kim S. Y., Bahk Y. Y., Lee J. E., Yoo T. H., Lee H. W. (2011) Transgenic overexpression of p23 induces spontaneous hydronephrosis in mice. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 92, 251–259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cheng W. C., Berman S. B., Ivanovska I., Jonas E. A., Lee S. J., Chen Y., Kaczmarek L. K., Pineda F., Hardwick J. M. (2006) Mitochondrial factors with dual roles in death and survival. Oncogene 25, 4697–4705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Karbowski M., Norris K. L., Cleland M. M., Jeong S. Y., Youle R. J. (2006) Role of Bax and Bak in mitochondrial morphogenesis. Nature 443, 658–662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lindenboim L., Blacher E., Borner C., Stein R. (2010) Regulation of stress-induced nuclear protein redistribution. A new function of Bax and Bak uncoupled from Bcl-x(L). Cell Death Differ. 17, 346–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]