Abstract

In the United States, 40 – 50% of the men and women 50 years of age or older regularly use multivitamin/mineral (MVM) supplements, making the annual sales of these supplements over $11 billion. However, the question remains whether using MVM supplements is beneficial to health. This article reviews the results of randomized studies of MVM supplements and individual vitamins/mineral supplements in relation to overall mortality and incidence of chronic diseases, particularly cancer and ischemic heart disease. The results of large-scale randomized trials show that, for the majority of the population, there is no overall benefit from taking MVM supplements. Indeed, some studies have shown increased risk of cancers in relation to using certain vitamins.

Keywords: vitamins, minerals, cancer, coronary heart disease, mortality

INTRODUCTION

Multivitamin / mineral (MVM) supplements certainly sell well in the United States. According to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data, collected between 2003 and 2006, 40 – 50% of the men and women 50 years of age or older regularly consume MVM 0supplements.[1] In 2009, the total sale of nutritional supplements in the United States was approximately $27 billion,[2] and in 2010, despite the economic downturn, this number grew by 4.4% to over $28 billion.[3] Of this, over $11 billion was the sales of MVM or MVM-containing supplements.[2,3] However, do healthy individuals really need MVM supplements? Are they beneficial in reducing the risk of chronic diseases such as ischemic heart disease, cancer, and stroke? The answer is most likely NO. The results of large-scale randomized trials in the past two decades have shown that for the majority of the population, MVM supplements are not only ineffective, but they may be deleterious to health.

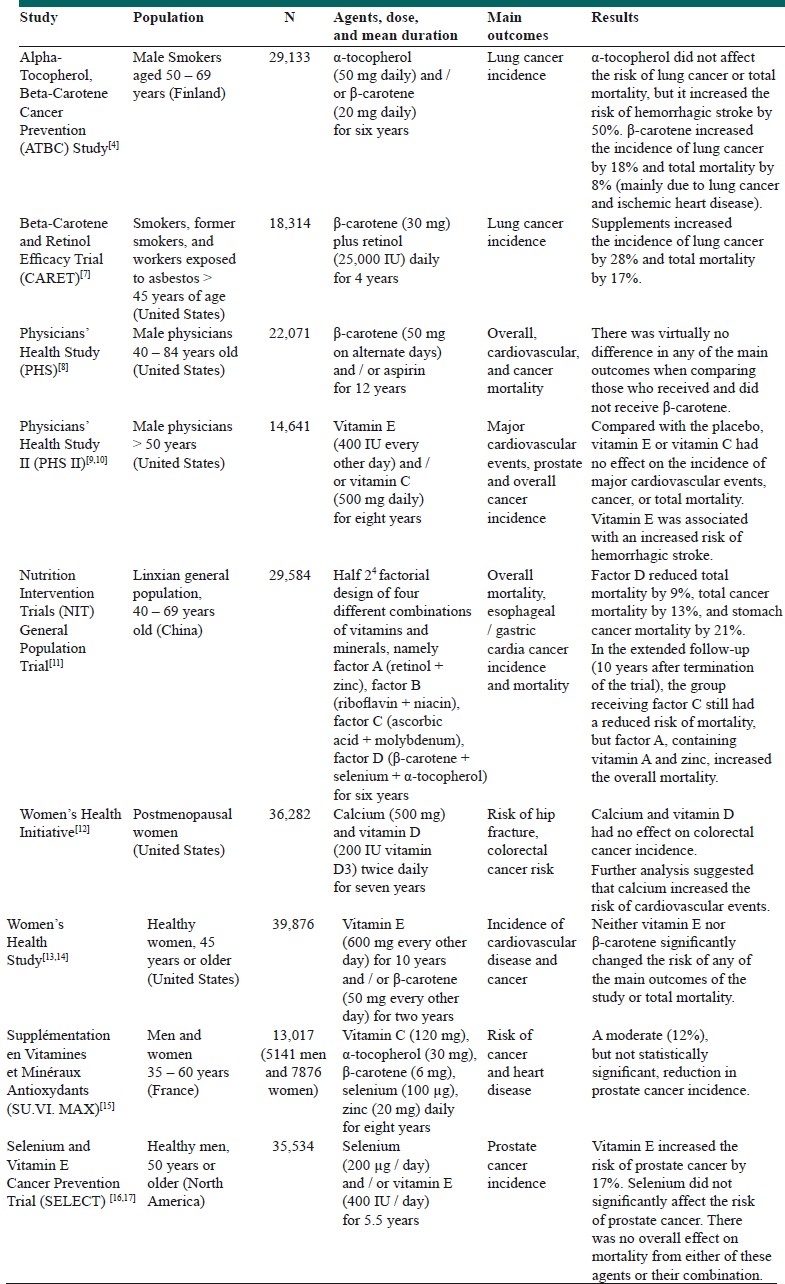

When the Alpha-Tocopherol Beta-Carotene Cancer Prevention (ATBC) study presented the first strong evidence for a harmful effect of vitamins in 1994,[4] health scientists were caught by surprise. The results of this large-scale 2 × 2 factorial design trial, which randomized over 29,000 middle-aged Finnish smoker men to receive α-tocopherol (a form of vitamin E), beta-carotene (a precursor of vitamin A), both, or neither, showed that β-carotene statistically significantly increased lung cancer incidence by 18% and total mortality by 8%, mainly due to increased deaths from lung cancer and ischemic cardiac disease.[4] α-tocopherol did not materially change the risk of lung cancer or total deaths. Despite the strong design of this trial and its large sample size, the results were met with skepticism. The results were deemed to be inconsistent with several of the previously published observational studies, based on which the trial had been designed to reduce the risk of lung cancer.[5,6] Several of the accompanying letters of correspondence, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, pointed to the potential shortcomings of this study, such as short duration of the study (i.e., a median follow-up of six years). Nevertheless, results of most of the subsequent trials, using other forms of vitamins and supplements, conducted in different populations and with different durations of use, have confirmed no benefit or even harm from the use of such vitamin supplements [Table 1].[4,7–17] The most recent notable one was the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT Trial), the extended results of which showed that vitamin E supplements could increase the risk of prostate cancer among healthy men.[17] One exception to these null or deleterious effects was the result of the General Population Nutrition Intervention Trial conducted in Linxian, China,[7,18] which tested four combinations of vitamins and supplements (namely, factors A, B, C, and D). Factor D (a combination of selenium, α-tocopherol, and β-carotene) reduced overall mortality by approximately 10%. However, this trial was conducted in an area where micronutrient intake was quite poor, and thus supplements might have had a beneficial role. Even in this nutrition-deficient population, results of the trial showed no benefit for two of the other MVM supplements (factors B and C; see Table 1), and extended follow-up showed adverse results for one of the supplements (factor A containing zinc and vitamin A).[18]

Table 1.

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, primary prevention trials designed to reduce risk of major chronic diseases

Thus far, several meta-analyses, authoritative reviews, and expert panel reports have been published on the use of MVMs in preventing chronic diseases in healthy individuals. Almost all have found no overall benefit. For example, a systematic review and meta-analysis, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), in 2007, concluded that, “Treatment with β-carotene, vitamin A, and vitamin E may increase mortality. The potential roles of vitamin C and selenium on mortality need further study”.[19] Another more recent meta-analysis concluded that, “Dietary supplementation with folic acid to lower homocysteine levels had no significant effects within five years on cardiovascular events or on overall cancer or mortality in the populations studied” .[20] A recent re-analysis of the Women's Health Initiative, which was published along with the meta-analysis of the available literature, concluded that calcium supplements with or without vitamin D increased the risk of the cardiovascular events, particularly myocardial infarction.[21] An expert panel meeting at the National Institutes of Health, in 2006, concluded that there was ‘insufficient evidence’ to recommend for or against the use of MVMs by the American public to prevent chronic diseases.[22] The World Cancer Research Fund and the American Institute for Cancer Research has recommended against the use of dietary supplements by the public, for cancer prevention.[23] These expert panel reports appeared prior to the publication of the recent results from the SELECT Trial or those from the Women's Health Initiative, which bolstered the ‘no benefit or even harm’ conclusion.

We would like to emphasize that these conclusions are for the general population, and for prevention of chronic diseases such as cancer and cardiovascular disease. In special cases, individuals may need vitamins or supplements. For example, periconceptional folate supplements substantially reduce the risk of neural tube defects.[24] Likewise, iron supplements during pregnancy can substantially reduce the risk of anemia and perinatal complications in mothers.[25] Physician-recommended treatment of disorders such as osteoporosis,[26] as well as other diseases, may require use of MVMs or individual vitamins or minerals, but these are not the subject of this article. In addition, these conclusions do not negate the potential health benefits of eating fresh fruits and vegetables.

One might ask then, given substantial evidence for lack of any health benefit from MVM use for the majority of the adult population, why are these products so widely marketed in the United States and elsewhere? Or why would over 40% of the older population of the United States regularly use them? The answer is perhaps multifactorial. First, the belief in the use of vitamins has deep roots. The immense beneficial effects of vitamins in preventing pellagra, rickets, and scurvy at a period when overt nutritional deficiencies were common, gave the halo of a magical effect to these drugs. Before the 1990s, some eminent scientists strongly advocated the use of vitamins and supplements. Most notably, Linus Pauling, a two-time Nobel Laureate and a towering figure in chemistry, believed that vitamin C could prevent cancer and increase the life expectancy of cancer patients.[27] Pauling and Cameron supplemented 100 terminal cancer patients with vitamin C and compared them with 1000 similar patients who did not receive such supplementation and concluded that the lives of those receiving vitamin C were prolonged by one year.[28] However, this study was not randomized, and two subsequent double-blind randomized trials sponsored by the National Cancer Institute and conducted in the Mayo Clinic, did not find any benefit from oral supplementation with vitamin C.[29,30] Despite such negative results, the effect of Pauling's and other scientists’ highly publicized comments still linger in the media and in people's minds.

Second, in the United States, unlike the case for drugs, human research is not required to prove that supplements are safe or effective.[31] Only if the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) finds that supplements are unsafe, can they stop the distribution of the products.[31] Third, there exists substantial inaccurate or misleading advertising in the media, which might be expected, given the annual $27 billion business. For example, a TV commercial has advertised the use of a certain brand of MVMs based on the results of a ‘Harvard Study,’ which had shown that lycopene use may reduce risk of prostate cancer. Although a Harvard Study’ has indeed shown an inverse association between dietary lycopene intake and prostate cancer risk,[32] the inference that one must use MVMs is incorrect for various reasons: (a) MVMs contain many vitamins and elements other than lycopene; (b) the results had come from an observational study and not a randomized trial, hence the results are subject to confounding factors; (c) prostate cancer is not the only meaningful health outcome, and the overall effect of MVMs on health needs to be considered. Fourth, many believe that MVMs, if not useful, will not harm. As the results of ATBC have shown, such a belief may be false. Fifth, many people want to take an active role in improving their health and increasing their longevity. Avoiding tasty, but unhealthy food, may be difficult, but taking a pill once a day is relatively easy. As others have discussed, prescription is more convenient than proscription.[5,33]

In summary, although in the long run MVMs may slightly increase the risk of cancer and cardiovascular diseases, in the short run they produce little harm or no harm, and thus negative consequences will not be discernible by individuals taking them. MVM sales benefit from misleading commercials, and people are pleased by the well-known placebo effects. Therefore, Americans who have been using MVMs since the early 1940s,[22] will most likely continue to use them in the foreseeable future, and the rest of the world will follow.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey RL, Gahche JJ, Lentino CV, Dwyer JT, Engel JS, Thomas PR, et al. Dietary supplement use in the United States, 2003-2006. J Nutr. 2011;141:261–6. doi: 10.3945/jn.110.133025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NBJ's Supplement Business Report 2010. United States: Penton Media; 2010. Nutrition Business Journal. [Google Scholar]

- 3.NBJ's Supplement Business Report 2011. United States: Penton Media; 2011. Nutrition Business Journal. [Google Scholar]

- 4.The ATBC Cancer Prevention Study Group. The effect of vitamin E and beta carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. The Alpha-Tocopherol, Beta Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1029–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404143301501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peto R, Doll R, Buckley JD, Sporn MB. Can dietary beta-carotene materially reduce human cancer rates? Nature. 1981;290:201–8. doi: 10.1038/290201a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The ATBC Cancer Prevention Study Group. The alpha-tocopherol, beta-carotene lung cancer prevention study: design, methods, participant characteristics, and compliance. Ann Epidemiol. 1994;4:1–10. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)90036-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Omenn GS, Goodman GE, Thornquist MD, Balmes J, Cullen MR, Glass A, et al. Effects of a combination of beta carotene and vitamin A on lung cancer and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1150–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605023341802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Manson JE, Stampfer M, Rosner B, Cook NR, et al. Lack of effect of long-term supplementation with beta carotene on the incidence of malignant neoplasms and cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1145–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605023341801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sesso HD, Buring JE, Christen WG, Kurth T, Belanger C, MacFadyen J, et al. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of cardiovascular disease in men: The Physicians’ Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;300:2123–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaziano JM, Glynn RJ, Christen WG, Kurth T, Belanger C, MacFadyen J, et al. Vitamins E and C in the prevention of prostate and total cancer in men: The Physicians’ Health Study II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301:52–62. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blot WJ, Li JY, Taylor PR, Guo W, Dawsey S, Wang GQ, et al. Nutrition intervention trials in Linxian, China: Supplementation with specific vitamin / mineral combinations, cancer incidence, and disease-specific mortality in the general population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1483–92. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.18.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wactawski-Wende J, Kotchen JM, Anderson GL, Assaf AR, Brunner RL, O’Sullivan MJ, et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:684–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee IM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, Gordon D, Ridker PM, Manson JE, et al. Vitamin E in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and cancer: The Women's Health Study: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294:56–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee IM, Cook NR, Manson JE, Buring JE, Hennekens CH. Beta-carotene supplementation and incidence of cancer and cardiovascular disease: The Women's Health Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:2102–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.24.2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer F, Galan P, Douville P, Bairati I, Kegle P, Bertrais S, et al. Antioxidant vitamin and mineral supplementation and prostate cancer prevention in the SU.VI.MAX trial. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:182–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, Lucia MS, Thompson IM, Ford LG, et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) JAMA. 2009;301:39–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klein EA, Thompson IM, Jr, Tangen CM, Crowley JJ, Lucia MS, Goodman PJ, et al. Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: The Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT) JAMA. 2011;306:1549–56. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Qiao YL, Dawsey SM, Kamangar F, Fan JH, Abnet CC, Sun XD, et al. Total and cancer mortality after supplementation with vitamins and minerals: Follow-up of the Linxian General Population Nutrition Intervention Trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:507–18. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bjelakovic G, Nikolova D, Gluud LL, Simonetti RG, Gluud C. Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007;297:842–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.8.842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clarke R, Halsey J, Lewington S, Lonn E, Armitage J, Manson JE, et al. Effects of lowering homocysteine levels with B vitamins on cardiovascular disease, cancer, and cause-specific mortality: Meta-analysis of 8 randomized trials involving 37 485 individuals. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1622–31. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bolland MJ, Grey A, Avenell A, Gamble GD, Reid IR. Calcium supplements with or without vitamin D and risk of cardiovascular events: Reanalysis of the Women's Health Initiative limited access dataset and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2011;342:d2040. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference Statement: multivitamin / mineral supplements and chronic disease prevention. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:257S–64S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.1.257S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: A global perspective. Washington DC: AICR; 2007. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Modell B, Lawn J. Folic acid to reduce neonatal mortality from neural tube disorders. Int J Epidemiol. 2010;39(Suppl 1):i110–21. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yakoob MY, Bhutta ZA. Effect of routine iron supplementation with or without folic acid on anemia during pregnancy. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(Suppl 3):S21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S3-S21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewiecki EM. Prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008;35:301–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cameron E, Pauling L. Ascorbic acid and the glycosaminoglycans.An orthomolecular approach to cancer and other diseases. Oncology. 1973;27:181–92. doi: 10.1159/000224733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cameron E, Pauling L. Supplemental ascorbate in the supportive treatment of cancer: Prolongation of survival times in terminal human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1976;73:3685–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.10.3685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Creagan ET, Moertel CG, O’Fallon JR, Schutt AJ, O’Connell MJ, Rubin J, et al. Failure of high-dose vitamin C (ascorbic acid) therapy to benefit patients with advanced cancer.A controlled trial. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:687–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197909273011303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moertel CG, Fleming TR, Creagan ET, Rubin J, O’Connell MJ, Ames MM. High-dose vitamin C versus placebo in the treatment of patients with advanced cancer who have had no prior chemotherapy. A randomized double-blind comparison. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:137–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.NIH Office of Dietary Supplments. [Last accessed on 2012]. Available from: http://www.ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/list-Vitamins Minerals/

- 32.Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Liu Y, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC. A prospective study of tomato products, lycopene, and prostate cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:391–8. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.5.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor PR, Greenwald P. Nutritional interventions in cancer prevention. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:333–45. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]