Abstract

In ecosystems, a variety of biological, chemical and physical stressors may act in combination to induce illness in populations of living organisms. While recent surveys reported that parasite-insecticide interactions can synergistically and negatively affect honeybee survival, the importance of sequence in exposure to stressors has hardly received any attention. In this work, Western honeybees (Apis mellifera) were sequentially or simultaneously infected by the microsporidian parasite Nosema ceranae and chronically exposed to a sublethal dose of the insecticide fipronil, respectively chosen as biological and chemical stressors. Interestingly, every combination tested led to a synergistic effect on honeybee survival, with the most significant impacts when stressors were applied at the emergence of honeybees. Our study presents significant outcomes on beekeeping management but also points out the potential risks incurred by any living organism frequently exposed to both pathogens and insecticides in their habitat.

In the environment, living organisms are exposed to a variety of biotic and abiotic stressors that may drastically reduce their longevity and fitness1,2. These stressors may be anthropogenic (e.g. pollutants) as well as natural (e.g. pathogens). Recently, multiple stressors approaches have received an increasing interest in ecotoxicology, the interaction between those agents being potentially synergistic. Synergistic interaction is defined as a combination of stressors that results in a greater effect than expected from cumulative independent exposures3. Synergistic interactions of some chemicals combined to natural stressors have been studied on aquatic organisms like daphnia4,5,6,7,8 and used to control pest in various ecosystems9,10,11,12,13,14,15.

Insecticides are designed to induce high mortality in populations of target organisms (i.e. pests) and may be combined to biological control agents for a better effectiveness. For instance, synergistic interactions between the insecticide imidacloprid and two entomopathogenic nematodes (Steinernema glaseri or Heterorhabditis bacteriophora) have been observed against white grubs (Cyclocephala hirta, Cyclocephala borealis and Popillia japonica)16. However, insecticides can have collateral effects on non-target species by disturbing their physiology and exacerbating the negative effects of pathogens3. For instance, the foraging activity of wild and domesticated bees, key species for pollination in ecosystems, may expose them simultaneously to both parasites and insecticides, resulting in harmful effects on their health and lifespan17,18,19,20,21.

As a major pollinator, the Western honeybee Apis mellifera (Hymenoptera: Apidae) has a substantial economical and ecological value22. Therefore, colony losses recorded for the last decade represent a concerning issue for both crop and apiary fields. The origin of this phenomenon is likely to be multicausal, with a strong emphasis on parasites and insecticides23,24,25,26. The microsporidian parasite, Nosema ceranae (Dissociodihaplophasida: Nosematidae), is a unicellular eukaryote and invasive intracellular parasite infecting A. mellifera midgut, inducing a disease named nosemosis27. It is a worldwide emerging parasite that presents a high prevalence in honeybee colonies28,29. The insecticide fipronil (5-amino-1-(2,6-dichloro-α,α,α-trifluoro-p-tolyl)-4-trifluoromethylsulfinylpyrazole-3-carbonitrile) is a chemical stressor of A. mellifera19 which is extensively used against arthropod pests on crops worldwide, and especially in USA30. This is a neurotoxic compound of the phenylpyrazoles family whose action on neuronal signaling can potentially results in mortality31. In this work, N. ceranae and a sublethal dose of the insecticide fipronil were chosen as natural and chemical stressors respectively to assess synergistic interactions that can occur in honeybees.

While recent surveys reported that parasite-insecticide interactions can negatively affect honeybee survival32,33, the importance of sequence in exposure to stressors has hardly received any attention. Yet, in their natural habitat, organisms may be exposed to a chemical first and then to a natural stressor, or the opposite, or to different stressors simultaneously, and those various scenarios may differently affect the organism. A recent survey demonstrated that sublethal doses of fipronil, but also of another insecticide, thiacloprid, highly increase the mortality of honeybees previously infected by N. ceranae, suggesting that N. ceranae infection may render honeybees more susceptible to insecticides33. Contrariwise, the reported opportunism of microsporidian parasites34,35,36 suggests that honeybee could become less resistant to parasite infection following sublethal exposure to insecticides. Moreover, as honeybees can easily be simultaneously exposed to fipronil and N. ceranae inside the hive, one could wonder about the consequences of such combined effect on honeybee survival. In the present work, different N. ceranae-fipronil combinations were compared in order to analyze the impact of exposure sequence on laboratory-reared honeybee survival. Honeybees were thus submitted to all combinations of parasite exposure (presence or absence) and sublethal insecticide chronic exposure (presence or absence). Interestingly, all combinations led to a synergistic effect on honeybee mortality.

Results

In order to detect potential synergistic effects between a pathogen and an environmental chemical stressor on honeybee mortality, we analyzed four different N. ceranae-fipronil combinations: (i) honeybees infected by N. ceranae (125,000 spores/bee) then chronically exposed to fipronil for 7 days; (ii) honeybees previously intoxicated then infected; (iii) honeybees simultaneously infected and intoxicated at their emergence from nymphal cell or (iv) simultaneously infected and intoxicated at the age of 7 days. Honeybee chronic exposure to fipronil was done at a concentration (1 µg/L of sucrose syrup) that can be potentially encountered inside the hive19,20.

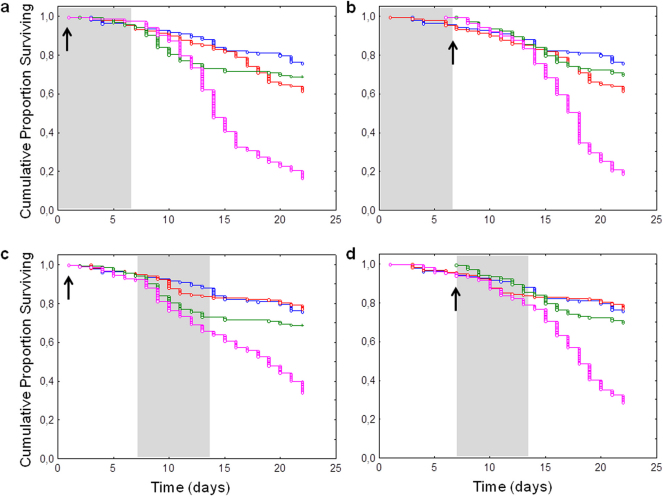

Survival analysis indicated that each N. ceranae-fipronil combination led to a significant decrease (p≤0.05) in honeybee survival compared to control or single treatments (Figure 1, see Supplementary Table S1 online). As expected, control honeybees presented the lowest mortality rate (24%) at the end of the experiment, 22 days after emergence. Moreover, while mortalities of honeybees exposed to N. ceranae or fipronil alone reached a maximum of 39 and 31% respectively, the one of honeybees co-exposed to both factors reached a maximum of 84%. In each case, the N. ceranae-fipronil combination induced a synergistic effect compared to the sum of the effects observed in honeybees exposed to each stressor alone (Table 1). Using the proportional hazard model (Cox regression), we determined whether the different treatments or the combination sequence had a significant impact on honeybees survival probability during the entire experiment (Table 2). Statistical analysis indicated that N. ceranae factor had a highly significant impact on honeybees survival, but only when applied at the emergence (Wald’s statistics (Ws) = 42.1, degree of freedom (df) = 5, p = 0.000). Fipronil factor also had a highly significant impact on honeybees survival probability when applied at their emergence (Ws = 24.1, df = 5, p = 0.000) and a less significant impact when applied on 7-day-old bees (Ws = 4.5, df = 5, p = 0.034). Moreover, the factor corresponding to the sequence of treatments also had a highly significant impact on survival (Ws = 11.4, df = 5, p = 0.001). The cumulated mortalities recorded at the end of the experiment (22 days after emergence) were also compared between groups exposed to different N. ceranae-fipronil combinations (Table 3). Compared to honeybees infected 7 days after their emergence, statistical analysis showed that honeybees infected at the emergence exhibited a significantly higher mortality rate, whenever the fipronil was applied simultaneously or 7 days later.

Figure 1. Effect of N. ceranae-fipronil combinations on honeybee survival.

Data give the cumulative proportion of surviving honeybees exposed to no treatment ( ), to N. ceranae (

), to N. ceranae ( ) or fipronil (

) or fipronil ( ) alone, or to a N. ceranae-fipronil combination (

) alone, or to a N. ceranae-fipronil combination ( ). Different sequential combinations of N. ceranae infection (arrows) and 7-day-long chronic exposure to fipronil (grey boxes) were performed: (a) both treatments were applied on emerging honeybees, (b) bees were chronically exposed to fipronil on week 1 then infected by N.

ceranae, (c) bees were infected at their emergence then chronically exposed to fipronil on week 2, (d) both treatments were applied on 7-day-old bees. Data from three replicates of 50 honeybees were analyzed with the Kaplan-Meier method.

). Different sequential combinations of N. ceranae infection (arrows) and 7-day-long chronic exposure to fipronil (grey boxes) were performed: (a) both treatments were applied on emerging honeybees, (b) bees were chronically exposed to fipronil on week 1 then infected by N.

ceranae, (c) bees were infected at their emergence then chronically exposed to fipronil on week 2, (d) both treatments were applied on 7-day-old bees. Data from three replicates of 50 honeybees were analyzed with the Kaplan-Meier method.

Table 1. Synergistic interactions between N. ceranae (Nc) and fipronil (F).

| Exposure | Mortality (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| day 0 | day 7 | Observed | Expected* | χ2** | Effect |

| Nc + F | - | 83.7 | 57.7 | 11.7 | Synergistic |

| Nc | F | 81.4 | 57.2 | 10.2 | Synergistic |

| F | Nc | 66.5 | 47.3 | 7.8 | Synergistic |

| - | Nc + F | 71.9 | 46.8 | 13.5 | Synergistic |

*Expected mortality (ME) on day 22 has been calculated as MNc + MF (1-MNc/100), with MNc and MF being the observed percent mortalities caused by N. ceranae and fipronil alone respectively.

**The calculated χ2 is much higher than the theoretical χ2 (i.e. χ2 = 6.635, df = 1, p = 0.01).

Table 2. Treatments involvement in honeybee survival probability.

| Variable | Wald’s statistic | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence of treatments | 11.4 | 0.001 |

| N. ceranae infection on day 0 | 42.1 | 0.000 |

| N. ceranae infection on day 7 | 0.2 | 0.630 |

| Fipronil exposure from day 0 to 7 | 24.1 | 0.000 |

| Fipronil exposure from day 7 to 14 | 4.5 | 0.034 |

The given Wald’s statistic and p-value are results of the Cox’s Proportional Hazard Model (n = 1539). Significant differences (p≤0.05) are underlined. The higher the Wald's statistic, the higher the variable participates in affecting the survival.

Table 3. Host response to parasite (Nc) – insecticide (F) combinations.

| Exposure | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| day 0 | day 7 | Cumulative mortality (%)* | Cumulative sucrose consumption (mg/day/bee ± sd)** | Spore numeration (106spores/bee ± sd)** |

| Nc+F | - | 83.66 a | 665.8 ± 42.0 a | 151.2 ± 63.6 a |

| Nc | F | 81.41 a | 632.3 ± 60.4 a | 168.5 ± 61.9 a |

| F | Nc | 66.48 b | 621.8 ± 68.5 a | 96.4 ± 44.2 b |

| - | Nc+F | 71.91 b | 604.7 ± 89.9 a | 86.2 ± 38.5 b |

*Cumulative mortality rates on day 22 were compared pairwise using a one-tailed χ2 test.

**Spore numerations and cumulative sucrose consumptions on day 22 were compared pairwise using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Significant differences (p≤0.05) are indicated by non-corresponding letters.

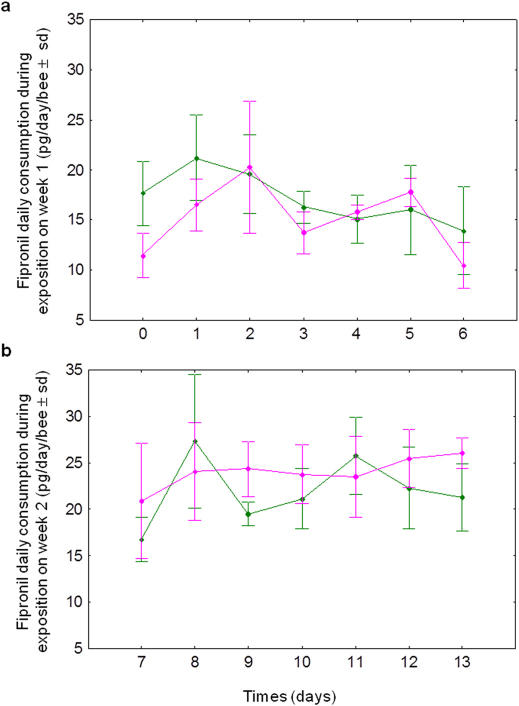

Fipronil daily consumptions have been monitored during both intoxication periods (week 1 or week 2 corresponding to days 0 to 7 or days 7 to 14 respectively). Honeybees absorbed a daily mean quantity of fipronil of 1/254th of the LD50 (16.4 ± 1.6 pg/day/bee) in the first case and of 1/179th of the LD50 (23.3 ± 2.5 pg/day/bee) in the second one (LD50 fipronil: 4.17 ng/bee37). As expected because of the low fipronil concentration administered (1 µg/L of sucrose syrup), statistical analysis indicated that mortality rates are not significantly different between fipronil-intoxicated and control honeybees (p = 0.092 and p = 0.334 for week 1 and week 2 respectively), confirming that honeybees received sublethal doses of insecticide. Moreover, for each intoxication period, infected honeybees did not significantly consume different cumulated quantities of fipronil (15.1 ± 4.3 and 24.0 ± 4.2 pg/day/bee for week 1 and week 2 respectively) compared to uninfected honeybees (17.1 ± 4.3 and 22.0 ± 5,0 pg/day/bee for the same periods) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effect of N. ceranae infection on honeybee fipronil consumption.

The mean of fipronil consumption (pg/day/honeybee ± standard deviation, sd) was monitored daily during weeks 1 (a) and 2 (b) for both infected ( ) and uninfected (

) and uninfected ( ) honeybees.

) honeybees.

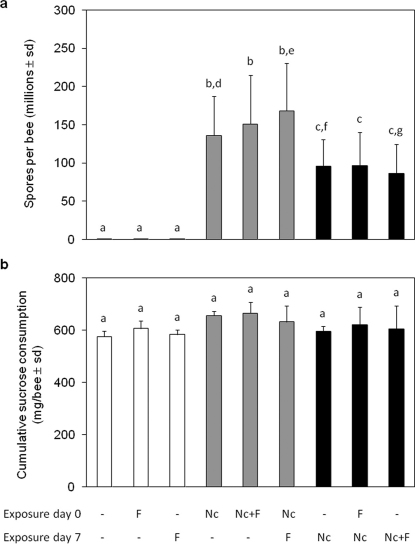

N. ceranae development success was monitored as the number of spores present in the abdomen of surviving honeybees at the end of experiment (day 22) (Figure 3). A mean of 3.0×103 ± 10.3×103 spores/bee was counted in the controls (i.e. uninfected groups), meaning that some control honeybees were likely slightly infected at the beginning of experiment. However, the level of N. ceranae infection was highly significantly different between experimentally and non-experimentally infected honeybees (Figure 3). As suspected, statistical analysis revealed that, at the end of the experiment, the spore content was higher in honeybees infected at the emergence than in honeybees infected on day 7 (145.2×106 ± 56.7×106 and 93.7×106 ± 38.6×106 spores/bee respectively). One can assume that this difference was only due to the infection duration. To identify a potential impact of the fipronil exposure on spore production, spore counts were compared between honeybees that were infected on a same day. Among groups infected at the emergence, honeybees only infected by N. ceranae presented a significantly lower spore count compared to honeybees intoxicated during week 2 (136.2×106 ± 51.1×106 and 168.5×106 ± 61.9×106 spores/bee respectively). Surprisingly, among groups infected 7 days after emergence, fipronil had a significant antagonistic effect on spore content when applied during the same week compared to honeybees only infected (86.2×106 ± 38.5×106 and 95.5×106 ± 35.3×106 spores/bee respectively). In each case, fipronil had no significant effect on spore count when applied during week 1.

Figure 3. N. ceranae development success and honeybee cumulative sucrose consumption on day 22.

Mean number of (a) spores per honeybee abdomen (in millions ± standard deviation, sd, n = 585) and (b) total sucrose consumption (mg/bee ± sd from 3 replicates of 50 initial individuals) in surviving honeybees on day 22, in response to various N. ceranae (Nc) and fipronil (F) treatments. White bars represent data of non-experimentally infected honeybees, grey bars that of honeybees infected by N. ceranae at the emergence and black bars that of honeybees infected by N. ceranae at the age of 7 days. Significant differences (p≤0.05) using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test between each experimental group are indicated by non-corresponding letters.

Discussion

Environmental pollution frequently results in the exposure to chemicals of organisms that can as well be subjected to other stressors such as pathogens. This multiple stressors exposure is likely to be detrimental for organism health and lifespan2,3 and makes the assessment of the potential effects associated with such combinations hardly difficult. We chose the Western honeybee, A. mellifera, as a model for studying interactions between pollutants and pathogens because it is frequently exposed to both factors inside hives worldwide. The microsporidian parasite N. ceranae and the phenylpyrazole insecticide fipronil were applied to honeybees following different sequences. A synergistic interaction between the neonicotinoid imidacloprid and Nosema infection has been previously observed when both agents were applied simultaneously to young worker honeybees32. In a more recent study, we have also shown a significant increase in mortality when young worker honeybees were firstly infected by N. ceranae then chronically exposed to fipronil or thiacloprid (neonicotinoid)33. To date, no work has been conducted on the impact of N. ceranae infection on previously intoxicated honeybees. In this sequence, two scenarios could have been expected. First, a higher mortality of co-exposed honeybees was possible as a sublethal dose of insecticide could render individuals more susceptible to pathogens, especially to opportunistic parasites such as microsporidia. Secondly, sublethal exposure to one stressor might induce subsequent stress resistance. The later would imply that honeybees exposed to a very low dose of fipronil may develop a stress resistance resulting in a lower impact of N. ceranae infection on honeybee survival. Surprisingly, our results revealed that, whatever the sequence tested, co-exposure led to a synergistic interaction between N. ceranae and fipronil on overall honeybee mortality (Table 1). These synergistic effects resulted in approximately 66 to 84 % mortality after 22 days in co-exposed groups, compared with 23 to 39 % for N. ceranae or fipronil alone.

Reviewing interactions occurring between chemical and natural stressors, Holmstrup et al. (2010) pointed out the lack of study assessing the importance of sequence in exposure to stressors3. Synergistic interactions between chemicals and pathogens have been relatively well documented in the framework of integrated pest management. In order to improve the malaria vector Anopheles gambiae control, mosquito larvae were exposed to different fungus-insecticide combinations: the permethrin, a pyrethroid insecticide, was combined to Beauveria bassiana or Metarhizium anisopliae12. This study indicated that all fungus-insecticide combinations led to synergistic effects on mosquito survival. This systematical synergistic effect between insecticides and pathogens detected in two different insects (i.e. honeybees and mosquitoes) is surprising and the mechanisms involved are still unknown. This higher mortality induced by parasite-insecticide interactions can be of great interest in integrated pest management, allowing a reduction of the chemical doses spread in the environment and a more efficient control of insecticide-resistant vectors. Nevertheless, such synergistic interactions can have detrimental side effects on beneficial arthropods such as honeybees and also render more complicated the risk assessment of insecticides introduced in the environment.

Statistical analyses (Cox regression model and pairwise comparisons of mortality rates) indicated that N. ceranae infection is the main factor influencing the honeybee mortality, but only when applied at the emergence of worker honeybees (Table 2). This result could be a consequence of the longer infection duration compared to honeybees infected on day 7 (22 vs. 15 days of infection respectively at the end of the experiment). However, we cannot exclude that the physiology of new emerging honeybees also resulted in a more harmful impact of N. ceranae infection. For instance, younger honeybees are likely to be less immunocompetent than their older congeners38,39. The fipronil factor had a significant but lower impact on overall honeybee survival compared to N. ceranae. This highlights the risk encountered inside hives where honeybees can easily be exposed to similar and even higher concentrations of fipronil or worse19,20, to both agents in a colony.

Several hypotheses could be proposed to explain the systematical occurrence of a synergistic effect between N. ceranae and fipronil. First, it has been shown that N. ceranae infection induces an energetic stress in honeybees that results in a higher food intake by infected individuals40,41. As proposed by Alaux et al.32, such a boost in food intake implies an increase in insecticide oral exposure, potentiating the effect of the later on honeybee mortality. However in this work, N. ceranae-infected and uninfected honeybees consumed a similar quantity of sucrose (Fig. 3). This result indicates that the increased food intake is unlikely to occur systematically during a N. ceranae infection and should not be considered as a specific symptom of nosemosis. Thereby, the highest mortality observed for honeybees treated with N. ceranae-fipronil combinations was not due to an increase in insecticide uptake.

In parasite-insecticide interactions, the parasite development and transmission success can be modified in intoxicated organisms42,43. It is known that insect detoxification system can act on a parasite development, disrupting or enhancing it44. On one hand, the deployment of insecticide detoxification may lead to physiological modifications that render the host toxic to parasites. For example, the development of the filaria Wuchereria bancrofti larvae is affected in insecticide-resistant Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes, probably due to an increase in esterase activity resulting in a change in the redox potential of the tissues hosting the parasite45. On the other hand, it can be hypothesized that the production of large amounts of detoxifying enzymes could deplete the resource pool through resource-based trade-offs, limiting the host’s immune abilities, therefore favouring the parasite development44. It has been previously stated that thiacloprid may increase N. ceranae spore production, while fipronil and, to a lesser extent, imidacloprid would decrease it32,33. In our experimental conditions, fipronil exposure seemed to have no precise impact on the parasite development. Indeed, fipronil exposure only had a significant but slight impact on N. ceranae development success when applied for 7 days starting from the 7th day after emergence (Fig. 3). Interestingly, fipronil slightly increased or decreased spore production depending on the day of infection. However, our results concern a unique time point in the experiment and a specific parasite development stage (mature spores). We cannot exclude a specific impact on the overall spore production kinetics or on earlier development stages since it has been suggested that microsporidia are dependent on host-derived ATP46,47,48 and that fipronil may precisely alter the cellular energetic metabolism49,50. Nevertheless, insecticides’ impact on N. ceranae development success in the honeybee seems more complex than thought before and clearly needs further investigations.

In conclusion, our findings showed that honeybees co-exposed to the natural stressor N. ceranae and to an environmental concentration of the insecticide fipronil will undergo a significantly higher mortality compared to the sum of the effects induced by each agent acting alone. Few studies have been done on such interactions in the honeybee and the resulting data illustrate the difficulty to find out the synergy related mechanisms. The economical and ecological value of honeybees renders our results worrying as the scenario of colonies housing both N. ceranae spores and insecticide residues is realistic. Those results also point out the potential risks incurred by any living organism frequently exposed to both pesticides and pathogens in their environment, no matter the sequence of exposure to those agents. Such multiple stressors interactions, endangering honeybees and potentially other communities, deserve additional attention. Finally, understanding the complexity of cumulative risks is a prerequisite for the implementation of more efficient guidelines in the frame of future chemicals regulation.

Methods

Honeybee artificial rearing

All experiments were performed on June 2011 with Apis mellifera emerging honeybees taken from different colonies of the same apiary at the Laboratoire Microorganismes: Génome et Environnement (UMR 6023, Université Blaise Pascal, Clermont-Ferrand, France). Those colonies were found Nosema-free by PCR-based detection as previously described by Higes et al.51. Frames of sealed brood were placed in an incubator in the dark at 33°C under humidified atmosphere. Emerging honeybees were collected and distributed in groups of 50 individuals into Pain-type cages52. In order to mimic the colony environment, a 5 mm piece of Beeboost® (Pherotech, Delta, BC, Canada) releasing 5 queen’s mandibular pheromones was placed in each cage. During all the experiment, honeybees were fed ad libitum with 50% (w/v) sugar syrup supplemented with 1% (w/v) Provita’Bee (VETOPHARM PRO). Every day, feeders were replaced, dead bees were counted and removed, and the sucrose consumption was quantified. Nine experimental groups were created as honeybees received no treatment (controls), one treatment (infected with N. ceranae or chronically exposed to fipronil) or both treatments in 4 different sequences. Treatments were administrated to emerging or 7-day-old honeybees. All experimental conditions were performed in triplicates (n = 150 bees per treatment).

Nosema ceranae infection

N. ceranae spores were obtained according to Vidau et al.33. The spore concentration was determined by counting using a haemocytometer chamber. N. ceranae species was confirmed by PCR51. Honeybees were infected the day of their emergence or 7 days later by individual feeding with 125,000 spores of N. ceranae in 5 µL of 50% sucrose solution using a micropipette53. Seven-day-old honeybees were previously anaesthetized with CO2 before infection. Control honeybees were treated with a sucrose solution devoid of N. ceranae spores.

Exposure to fipronil

Stock solution of fipronil (1 g/L) was prepared in DMSO (v/v). Emerging or 7-day-old honeybees were exposed ad libitum to fipronil by adding the insecticide in the feeding syrup to a final concentration of 1 µg/L fipronil, 0.1% DMSO (v/v). The insecticide consumption was quantified by measuring the daily amount of fipronil-containing sugar syrup consumed per cage then reported per living honeybee. Control honeybees were fed ad libitum with 0.1% DMSO-containing sugar syrup.

Effects of N. ceranae-fipronil combinations on host mortality and sucrose consumption

Survival analysis was performed using the Cox regression (i.e. proportional hazard model)54 by using Statistica 7.0 (StatSoft inc., Tulsa, USA). This model analyzes the event times at the day of death, censors times at the termination of the study on day 22. Cox regression also assesses the standing of the variables through a covariance matrix. In this work, a model was elaborated to determine the respective weight of five variables: nature of the treatment (infection or intoxication), its respective time application (day 0 or 7), and the treatments sequence.

Synergistic interactions between treatments on honeybee mortality at the end of experiment (i.e. on day 22) were determined using a χ2 test15. The expected interaction mortality value, ME, for combined agents was calculated using the formula ME = MNc + MF(1-MNc/100), where MNc and MF are the observed percent mortalities caused by N. ceranae and fipronil alone, respectively. Results from the χ2 test were compared to the χ2 table value with 1 df, using the formula χ2 = (MO−ME)2/ME, where MO is the observed mortality for the N. ceranae-fipronil combinations. A non-additive effect between the two agents was suspected when the χ2 value exceeded the table value and if the difference MO−ME had a positive value, a significant interaction was then considered synergistic. Finally, for each treatment, daily sucrose consumptions were compared by using the nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, which is an alternative to the t-test for independent samples.

Development success of N. ceranae

To determine the development success of N. ceranae, a spore numeration was performed on living honeybees at the end of the experiment (i.e. on day 22). Briefly, every abdomen was collected and homogenized in PBS (250 µL). After thorough grinding, samples were washed twice by centrifugation at 8000 x g for 5 min and resuspended in PBS (500 µL). The average number of spores of each honeybee was estimated using a haemocytometer chamber. N. ceranae development success (i.e. number of spores produced) was analyzed for each treatment by using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

Author Contributions

JA, CV, FD and NB conceived the experiments and designed the study. JA, DGB and NB analyzed the data, and wrote the main manuscript. JA performed the experiments with the help of CV, RF, MR, MD, BV and NB. LPB helped in the manuscript redaction. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS, MIE: Maladies Infectieuses et Environnement). JA and RF were supported by grants from the Ministère de l’Education Nationale de l’Enseignement Supérieur et de la Recherche, MR from Région Auvergne, CV from the CNRS.

References

- Loos M., Ragas A. M. J., Plasmeijer R., Schipper A. M. & Hendriks A. J. Eco-SpaCE: an object-oriented, spatially explicit model to assess the risk of multiple environmental stressors on terrestrial vertebrate populations. Sci. Total Environ. 408, 3908–3917 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen M., Stoks R., Coors A., van Doorslaer W. & de Meester L. Collateral damage: rapid exposure-induced evolution of pesticide resistance leads to increased susceptibility to parasites. Evolution 65, 2681–2691 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmstrup M. et al. Interactions between effects of environmental chemicals and natural stressors: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 408, 3746–3762 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coors A., Decaestecker E., Jansen M. & De Meester L. Pesticide exposure strongly enhances parasite virulence in an invertebrate host model. Oikos 117, 1840–1846 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Gérard C., Carpentier A. & Paillisson J. M. Long-term dynamics and community structure of freshwater gastropods exposed to parasitism and other environmental stressors. Freshw. Biol. 53, 470–484 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Gismondi E., Rigaud T., Beisel J. N. & Cossu-Leguille C. Microsporidia parasites disrupt the responses to cadmium exposure in a gammarid. Environ. Pollut. 160, 17–23 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Relyea R. & Hoverman J. Assessing the ecology in ecotoxicology: a review and synthesis in freshwater systems. Ecol. Lett. 9, 1157–1171 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sures B. Environmental parasitology. Interactions between parasites and pollutants in the aquatic environment. Parasite 15, 434–438 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnew P., Berticat C., Bedhomme S., Sidobre C. & Michalakis Y. Parasitism increases and decreases the costs of insecticide resistance in mosquitoes. Evolution 58, 579–586 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh A., Samih M. A., Khezri M. & Riseh R. S. Compatibility of Beauveria bassiana (Bals.) Vuill. with several pesticides. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 9, 31–34 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Blanford S. et al. Lethal and pre-lethal effects of a fungal biopesticide contribute to substantial and rapid control of malaria vectors. PLoS ONE 6, e23591 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farenhorst M. et al. Synergy in efficacy of fungal entomopathogens and permethrin against West African insecticide-resistant Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes. PLoS ONE 5, e12081 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farenhorst M. et al. Fungal infection counters insecticide resistance in African malaria mosquitoes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 17443–17447 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koppenhöfer A. M., Cowles R. S., Cowles E. A., Fuzy E. M. & Baumgartner L. Comparison of neonicotinoid insecticides as synergists for entomopathogenic nematodes. Biological Control 24, 90–97 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Rodriguez A. & Peck D. C. Synergies between biological and neonicotinoid insecticides for the curative control of the white grubs Amphimallon majale and Popillia japonica. Biological Control 51, 169–180 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Koppenhöfer A. M., Wilson M., Brown I., Kaya H. K. & Gaugler R. Biological control agents for white grubs (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) in anticipation of the establishment of the Japanese beetle in California. J. Econ. Entomol. 93, 71–80 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox-Foster D. L. et al. A metagenomic survey of microbes in honey bee colony collapse disorder. Science 318, 283–287 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martel A. C. et al. Acaricide residues in honey and wax after treatment of honey bee colonies with Apivar or Asuntol50. Apidologie 38, 534–544 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Mullin C. A. et al. High levels of miticides and agrochemicals in North American apiaries: implications for honey bee health. PLoS ONE 5, e9754 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pareja L. et al. Detection of Pesticides in Active and Depopulated Beehives in Uruguay. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 8, 3844–3858 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smodis Skerl M. I., Kmecl V. & Gregorc A. Exposure to pesticides at sublethal level and their distribution within a honey bee (Apis mellifera) colony. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 85, 125–128 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallai N., Salles J., Settele J. & Vaissiere B. Economic valuation of the vulnerability of world agriculture confronted with pollinator decline. Ecological Economics 68, 810–821 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd B. P. What’s killing American honey bees? PLoS Biol. 5, e168 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts S. G. et al. Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 345–353 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanEngelsdorp D. & Meixner M. D. A historical review of managed honey bee populations in Europe and the United States and the factors that may affect them. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 103 Suppl 1, S80–95 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vanEngelsdorp D. et al. Weighing risk factors associated with bee colony collapse disorder by classification and regression tree analysis. J. Econ. Entomol. 103, 1517–1523 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higes M., Martín-Hernández R. & Meana A. Nosema ceranae in Europe: an emergent type C nosemosis. Apidologie 41, 375–392 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Hedtke K., Jensen P. M., Jensen A. B. & Genersch E. Evidence for emerging parasites and pathogens influencing outbreaks of stress-related diseases like chalkbrood. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 108, 167–173 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klee J. et al. Widespread dispersal of the microsporidian Nosema ceranae, an emergent pathogen of the western honey bee, Apis mellifera. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 96, 1–10 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R. M., Ellis M. D., Mullin C. A. & Frazier M. Pesticides and honey bee toxicity – USA. Apidologie 41, 312–331 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Cole L. M., Nicholson R. A. & Casida J. E. Action of phenylpyrazole insecticides at the GABA-gated chloride channel. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 46, 47–54 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Alaux C. et al. Interactions between Nosema microspores and a neonicotinoid weaken honeybees (Apis mellifera). Environ. Microbiol. 12, 774–782 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidau C. et al. Exposure to sublethal doses of fipronil and thiacloprid highly increases mortality of honeybees previously infected by Nosema ceranae. PLoS ONE 6, e21550 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didier E. S. Microsporidiosis: an emerging and opportunistic infection in humans and animals. Acta Trop. 94, 61–76 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didier E. S. & Weiss L. M. Microsporidiosis: not just in AIDS patients. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 24, 490–495 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzen C. & Müller A. Microsporidiosis: human diseases and diagnosis. Microbes Infect. 3, 389–400 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kievits J. & Bruneau E. Neurotoxiques systémiques, un risque pour les abeilles? Abeilles & Cie 118, 12–17 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Laughton A. M., Boots M. & Siva-Jothy M. T. The ontogeny of immunity in the honey bee, Apis mellifera L. following an immune challenge. J. Insect Physiol. 57, 1023–1032 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson-Rich N., Dres S. T. & Starks P. T. The ontogeny of immunity: development of innate immune strength in the honey bee (Apis mellifera). J. Insect Physiol. 54, 1392–1399 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayack C. & Naug D. Parasitic infection leads to decline in hemolymph sugar levels in honeybee foragers. J. Insect Physiol. 56, 1572–1575 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayack C. & Naug D. Energetic stress in the honeybee Apis mellifera from Nosema ceranae infection. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 100, 185–188 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loge F. J., Arkoosh M. R., Ginn T. R., Johnson L. L. & Collier T. K. Impact of environmental stressors on the dynamics of disease transmission. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39, 7329–7336 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morley N. J. Interactive effects of infectious diseases and pollution in aquatic molluscs. Aquat. Toxicol. 96, 27–36 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivero A., Vézilier J., Weill M., Read A. F. & Gandon S. Insecticide control of vector-borne diseases: when is insecticide resistance a problem? PLoS Pathogens 6, e1001000 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarroll L. et al. Insecticides and mosquito-borne disease. Nature 407, 961–962 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeling P. J. & Corradi N. Shrink it or lose it: balancing loss of function with shrinking genomes in the microsporidia. Virulence 2, 67–70 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivarès C. P., Gouy M., Thomarat F. & Méténier G. Functional and evolutionary analysis of a eukaryotic parasitic genome. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 5, 499–505 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyretaillade E. et al. Extreme reduction and compaction of microsporidian genomes. Res. Microbiol. 162, 598–606 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidau C., Brunet J.-L., Badiou A. & Belzunces L. P. Phenylpyrazole insecticides induce cytotoxicity by altering mechanisms involved in cellular energy supply in the human epithelial cell model Caco-2. Toxicol. In Vitro 23, 589–597 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidau C. et al. Fipronil is a powerful uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation that triggers apoptosis in human neuronal cell line SHSY5Y. Neurotoxicology 32, 935–943 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higes M., Martín-Hernández R. & Meana A. Nosema ceranae, a new microsporidian parasite in honeybees in Europe. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 92, 93–95 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pain J. Nouveau modèle de cagettes expérimentales pour le maintien d’abeilles en captivité. Ann. Abeille 9, 71–76 (1966). [Google Scholar]

- Malone L. A. & Stefanovic D. Comparison of the responses of two races of honeybees to infection with Nosema apis Zander. Apidologie 30, 375–382 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Kalbfleisch J. D. & Prentice R. L. The Statistical Analysis Of Failure Time Data. (J. Wiley: 2002). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1