Abstract

The earliest thymic progenitors (ETPs) were recently shown to give rise to both lymphoid and myeloid cells. While the majority of ETPs are derived from IL-7Rα-positive cells and give rise exclusively to T cells, the origin of the myeloid cells remains undefined. Herein, we show both in vitro and in vivo that IL-13Rα1+ ETPs yield myeloid cells with no potential for maturation into T cells while IL-13Rα1− ETPs lack myeloid potential. Moreover, transfer of lineage-negative IL-13Rα1+ bone marrow stem cells into IL-13Rα1-deficient mice reconstituted thymic IL-13Rα1+ myeloid ETPs. Myeloid cells or macrophages in the thymus are regarded as phagocytic cells whose function is to clear apoptotic debris generated during T cell development. However, the myeloid cells derived from IL-13Rα1+ ETPs were found to perform antigen presenting functions. Thus, IL-13Rα1 defines a new class of myeloid restricted ETPs yielding Ag presenting cells that could contribute to development of T cells and the control of immunity and autoimmunity.

INTRODUCTION

The CD4–CD8 thymic double negative (DN)3 cells which express CD44, but not CD25, represent the first of 3 DN stages (DN1 through 3) of thymic T cell development (1, 2). The population of cells that express cKit in addition to CD44 at the DN1 stage represent the earliest thymic progenitors (ETPs) (3–5) and usually gives rise to T lymphocytes (6–8). However, recently it has been shown that the cKit+CD44+CD25− ETP population can generate myeloid cells (9, 10). This concept provides the ETP with the attribute of a multipotent cell (6) and suits the idea of thymic self-replenishment with guard cells to clear apoptotic debris generated during T cell development (11). Alternatively, the ETP population may be more inclusive and comprise diverse lineage-specific progenitors for lymphoid and myeloid cells. The latter postulate implies that lineage commitment occurs prior to migration of the progenitors to the thymus. While IL-7Rα has recently been shown to be expressed by T cell specific progenitors (12), the lack of myeloid progenitor-specific markers that could trace maturation and/or trafficking of these stem cells represents a limitation in the progress towards understanding tissue-specific stem cell growth and lineage development. IL-13 receptor alpha 1 (IL-13Rα1) is expressed on myeloid but not lymphoid cells (13–15) and is involved in the control of activation and cytokine production by myeloid macrophages (16, 17). We took advantage of this differential expression and function of IL-13Rα1 among lymphoid and myeloid cells, generated IL-13Rα1-deficient (IL-13Rα1−/−) and IL-13Rα1-green fluorescence protein (IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP) knock in mice, produced an anti-IL-13Rα1 antibody and used these tools to trace the progenitors of the thymic myeloid cells. Furthermore, we were able to analyze the differential potential of the progenitors both in vitro and in vivo. The results identified a novel class of myeloid specific progenitors within the ETP population characterized by specific expression of IL-13Rα1 and growth response to IL-13 cytokine. Indeed, the IL-13Rα1 expressing ETPs display a granulocyte-macrophage progenitor (GMP) phenotype previously described in the bone marrow (18, 19). These IL-13Rα1+ thymic GMPs are committed to the myeloid lineage as they lack T cell potential while readily maturing into lineage-specific (Lin+) myeloid cells both in vitro and in vivo. In contrast, thymic GMPs from receptor deficient mice have an altered phenotype and their maturation to the myeloid lineage is defective. The mature CD11b+ myeloid cells derived from IL-13Rα1+ ETPs are able to process and present antigen to T cells, a function that could be important for T cell development and the control of both immunity and autoimmunity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP and IL-13Rα1−/− mice

IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP 129Sv/Pas mice were generated in collaboration with GenOway, Lyon, France. The linearized targeting construct containing the IRES-GFP reporter cassette followed by a validated loxP-neomycin-loxP cassette was inserted into the Il13ra1 3′UTR with conservation of the endogenous Il13ra1 polyA site by electroporation into 129Sv ES cells. 3′ homologous recombination was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis. Chimeras were generated by blastocyst injection into pseudo-pregnant C57BL/6J females. Resulting males with a high degree of chimerism (80%) were subsequently bred to C57BL/6J Cre deleter females for excision of the neomycin selection cassette. Cre-excision was confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis. The resulting females were then crossed onto the C57BL/6 background by speed congenics for this study. Mice were genotyped using the following PCR primers: forward primer sequence 5′-3 ′ is ACAGGTTTCAAGACTAAGACTTTGGGGGTATC. The reverse primer sequence is CATTGAAGGCAAGAAAGAAATCACTTCTCC. IL-13Rα1-NeoRΔex7–9 (IL-13Rα1−/−) Balb/c mice were generated in collaboration with RADIL, Columbia, Missouri. Briefly, the IL-13Rα1 locus was disrupted at exons 7, 8, and 9 by homologous recombination of the targeting construct containing a neomycin cassette into Balb/c ES cells and confirmed by PCR and Southern blot analysis. Chimeras were generated by blastocyst injection into pseudo-pregnant C57BL/6 females and bred to the Balb/c background to establish the strain. These mice were then crossed onto the C57BL/6 background by speed congenics for this study. Mice were genotyped with the following PCR primers: 5 ′-3 ′: common forward primer, CGAAGATTCAGCTCCCAGCATTACAG; wild-type reverse primer, GCAAGAACACCAGGGAGTTGGAAA; knockout reverse primer, AGATCAGCAGCCTCTGTTCCACATACAC.

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, Maine. B6.SJL (CD45.1) and OT-II mice (I-Ab) were a gift from Dr. Deyu Fang, Northwestern University, Chicago, Illinois. All animal experiments were done according to protocols approved by the University of Missouri animal care and use committee.

Western blot analysis

Fractions from IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP, IL-13Rα1−/−, and IL-13Rα1+/+ thymi were subjected to SDS-PAGE NuPage (Novex, San Diego, CA) 4–12% in MOPS-SDS running buffer under reducing conditions. The Western blot assay was performed using anti-IL-13Rα1 monoclonal antibody (IG3) and β actin (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) primary antibodies, biotinylated rat anti-mouse IgG as a secondary antibody, and avidin peroxidase as the enzymatic reagent for detection. The reaction was revealed by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden).

Antigen

Chicken ovalbumin (OVA protein) was purchased from SIGMA. The proteolipid protein was purified from rat brain as described (20).

Anti-IL-13Rα1 monoclonal antibody

Anti-IL-13Rα1 mAb was generated by immunization of IL-13Rα1−/− Balb/c mice with rmIL-13Rα1 protein. Hybridomas were generated by fusion of SP2/0 myeloma cells with splenocytes.

Flow cytometry

Most antibodies were purchased from BD Biosciences or Ebiosciences. Antibodies used were CD4 (RM4–5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD3 (eBio500A2), CD25 (PC61), F4/80 (BM8), FcγRII/III (93), cKit (CD117) (2B8), CD45.2 (104), Sca1 (D7), CD11b (M1/70), CD11c (HL3), CD44 (IM7), CD45 (30-F11), IL-7Rα (SB/199), FoxP3 (FJK-16s), biotinylated goat anti-mouse Ig, biotinylated anti-IL-13Rα1 (mIgG1) and purified anti-mouse I-Ab. FcγRs were blocked using mouse IgG (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). All mice were perfused with 40 ml PBS through the left ventricle to deplete contaminating peripheral blood cells prior to organ harvesting. Dead cells were excluded using 7-amino-actinomycin D (7AAD)(EMD Biosciences). Cells were sorted on a Beckman Coulter MoFlo (Brea, CA) and only those with a purity of 95% or higher were used. Cells were read using a Beckman Coulter CyAn (Brea, CA) and data were analyzed using FlowJo version 8.8.6 (Tree Star).

OP9 and OP9-DL1 cell culture

OP9 and OP9-DL1 cultures were used essentially as described (21). To deplete Lin+ cells, a cocktail of the following biotin-conjugated or magnetic bead conjugated antibodies was used: CD8a (Ly-2), CD4 (L3T4), CD45R (B220), CD19, anti-MHC II, CD49d (DX5), CD11b (Mac-1), CD11c and Ter-119 (Miltenyi Biotech). IL-7 was used at a final concentration of 1 ng ml−1, Flt3 ligand at 5 ng ml−1, and IL-3 and IL-13 at 10 ng ml−1. Myeloid progeny were evident at day 3 of culture under these conditions. Stromal cells were plated 2 days before initiation of cultures at a concentration of 20,000 cells ml−1 in 24 well plates and the progenitors were added at 2–3 × 103 cells per well.

Bone marrow chimeras

Bone marrow was harvested from the femur and tibia of IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP or IL-13Rα1−/− mice, washed, filtered to remove bone fragments, depleted of mature cells (Lin+), resuspended in PBS and injected (10 × 106 donor cells per recipient) intravenously through the tail vein into lethally irradiated (900Rads) IL-13Rα1−/− recipient mice as described (22). Thymi were harvested from the chimeras seven days post transfer and assessed for stem cell seeding by flow cytometry. All recipient mice were kept under antibiotic prophylaxis using Baytril (Bayer) for the duration of the experiment.

Cell Sorting

ETP sorting

Thymi were harvested from mice after perfusion with PBS. Lin+ cells were depleted and the resulting Lin− cells were stained with anti-CD44, anti-CD25, and anti-cKit antibodies for 30 minutes on ice. The CD44+CD25− cells were gated and analyzed for cKit and those positive for CD44 and cKit but not CD25 were sorted for IL-13Rα1 expression on the basis of GFP. GFP− ETPs were used as control. For isolation of ETPs from IL-13Rα1−/− mice the CD44+CD25− cells were gated and sorted on the basis of cKit expression. Cell purity was routinely checked and only sorts with a purity of 95% or greater were used in this study.

DN1 sorting

Thymi were harvested and Lin+ cells depleted. The resulting Lin− cells were stained with anti-CD44 and anti-CD25 antibodies. The CD44+ cells were gated and analyzed for CD25 expression and those negative for CD25 were sorted for IL-13Rα1 expression on the basis of GFP. GFP− DN1 cells were used as control. For isolation of DN1 cells from IL-13Rα1−/− mice the CD44+CD25− cells were sorted on the basis of CD44 expression. Cell purity was routinely checked and only sorts with a purity of 95% or greater were used in this study.

Sorting of Il-13Rα1+Lin− Bone marrow cells

Bone marrow was harvested from IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP mice and depleted of Lin+ cells. The resulting Lin− cells were stained with anti-cKit and anti-Sca1 antibodies. Cells identified as cKit+Sca1− were sorted for IL-13Rα1 expression on the basis of GFP. Only cells with ≥ 95% purity are used.

RT-PCR

IL-13Rα1+cKit+Lin− cells were sorted from the bone marrow of IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP mice. Control CD8+ T cells were sorted from the intraepithelial layer of the small intestine. RNA was isolated using Trizol extraction and ethanol precipitation. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription kit from Qiagen (Valencia, CA) and StepOne Instrument cycler (Applied Biosystems). The forward primers were as follows: 5′-ACCATGATGCCCACAGAACTCA-3′ for CCR9 and 5′-TACAATGAGCTGCGTGTGGC for β actin. The reverse primers were 5′-TGGCTTGCAAACTGCCTGACAT-3′ for CCR9 and 5′-AGCCTGGATGGCTACGTACA-3′ for β actin.

Proliferation assay

Myeloid cells were generated by culturing CD44+cKit+CD25−GFP+ precursors on OP9 cells in the presence of Flt3L and rIL-7 as described above. After 3 days, mature cells were harvested and re-plated at a concentration of 10,000 cells ml−1 in HT-2 media. Control CD11b populations were harvested from the thymus and spleen of wild-type mice using CD11b magnetic beads (Miltenyi). CD4+ T cells were harvested from the spleens of OT-II mice using CD4 magnetic beads (Miltenyi) and plated with myeloid cells at a concentration of 2 × 105 cells ml−1. OVA protein or control PLP was added for a final concentration of 20 μg ml−1. The culture was maintained for 48h. Subsequently, 1μCi [3H]thymidine was added per well and the culture was continued for an additional 14.5h. The cells were harvested on a Trilux 1450 Microbeta Wallac Harvester and incorporated [3H] thymidine was counted using the Microbeta 270.004 software (EG&G Wallac, Gaithersburg, MD).

Intrathymic injections

Sorted thymic CD44+CD25−GFP+ cells were injected into isoflurane anesthetized 6–8 week old B6.SJL (CD45.1) mice in a total volume of 10μl PBS. The injections were made directly through the skin between the 3rd and 4th rib into the thoracic cavity using a 0.3 ml 31-gauge 8-mm insulin syringe as previously described (23).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using either an unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t test or one-way ANOVA as indicated. All statistical analyses were done using Prism software v4.0c (Graphpad).

RESULTS

IL-13Rα1 is expressed by a minute population of thymic small cells

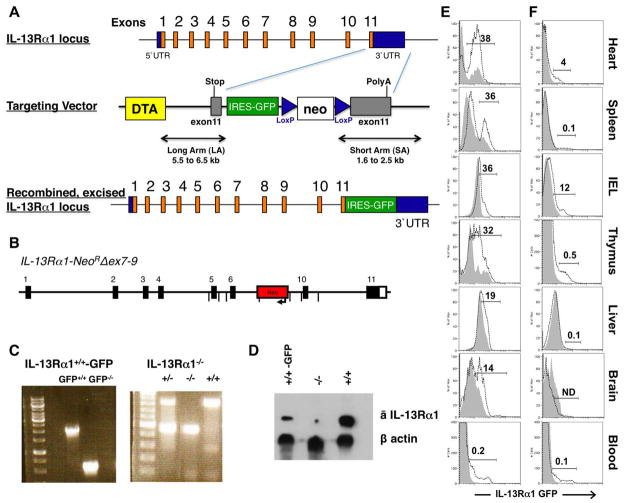

IL-13Rα1-deficient mice were generated by deletion of exons 7, 8, and 9 of the IL-13Rα1 locus and IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP mice were generated using the IRES bicistronic expression system (Figures 1A, 1B and 1C). An anti-IL-13Rα1 antibody was also generated by immunization of IL-13Rα1-deficient mice with IL-13Rα1 protein. This antibody, which is specific for IL-13Rα1, was used to assess receptor expression in both strains and indicate that IL-13Rα1 expression is defective in the receptor knock out mice but parallels GFP expression in the knock-in reporter mice (Figure 1D). Both strains did not show any major health problems or obvious discrepancies in the number of peripheral mature cells of hematopoietic origin. Given that the receptor is usually expressed by a variety of cell types that are granular and large in size including macrophages, dendritic cells, and mast cells (13, 24), we examined GFP expression in different organs on the basis of cell size and granularity (Figure 1E and F) to evaluate receptor expression on large versus small cells which would include stem cells and developing progenitors. Not surprisingly, IL-13Rα1 was expressed by bulk large, granular cells from the heart (38%), spleen (36%), intra-epithelial layer of the small intestine (IEL, 36%), thymus (32%), liver (19%), brain (14%), and a small percentage (0.2%) of peripheral blood (Figure 1E). Receptor expression was also observed on the small cells of the heart (4%), IEL (12%) and thymus (0.5%) (Figure 1F). Although the percentage of small cells expressing IL-13Rα1 was higher in the IEL and heart, the thymic cells had the highest GFP intensity on a per cell basis. These preliminary findings were unexpected as the majority of small cells within the thymus are developing T cells and IL-13Rα1 is not expressed by naive T cells (13–15).

Figure 1. Generation of IL-13Rα1-IRES-GFP and IL-13Rα1−/− mouse strains.

IL-13Rα1-IRES-GFP (IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP) and IL-13Rα1-deficient (IL-13Rα1−/−) mice were generated as described in materials and methods. (A) The top panel shows a schematic representation of the IL-13Rα1 locus. The targeting vector incorporates the diphtheria toxin A negative selection marker (DTA), the IRES-GFP cassette and the positive selection neomycin (neo) cassette flanked by loxP sites. The bottom construct depicts the IL-13Rα1 locus with the IRES-GFP gene incorporated at the end of exon 11. (B) the IL-13Rα1-NeoRΔex7–9 representation shows replacement of the transmembrane exons 7, 8, and 9 by the neomycin gene. (C) shows PCR analysis of the IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP (GFP+/+) and IL-13Rα1+/+ (GFP−/−) with a 2,029 and 578 bp band, respectively (left panel). The median panel shows PCR bands for heterozygous IL-13Rα1+/− mice (828 and 466 bp), homozygous IL-13Rα1−/− (466bp) and wild type IL-13Rα1+/+ (828 bp). D, shows expression of IL-13Rα1 in thymic cells from IL-13Rα1−/− (−/−), IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP (+/+-GFP) and IL-13Rα1+/+ wild-type C57BL/6 mice (+/+) as determined by western blot using an anti-IL-13Rα1 antibody. (E and F) cells were harvested from the heart, spleen, intra-epithelial layer of the small intestine (IEL), thymus, liver, brain, and peripheral blood of IL-13Rα1+/+ (solid line) and IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP (dotted line) mice and analyzed for expression of IL-13Rα1 by GFP. Dead cells were excluded by 7AAD. Large and granular (E) and small (F) cells were gated based upon forward and side-scatter parameters. GFP expression is depicted by histogram. The data is representative of 3 independent experiments with an N=2 per experiment. The numbers represent the percent GFP-positive cells (GFP+) among the total population based on the GFP− population. ND, not detected.

IL-13Rα1 is expressed exclusively at the DN1 stage of T cell development

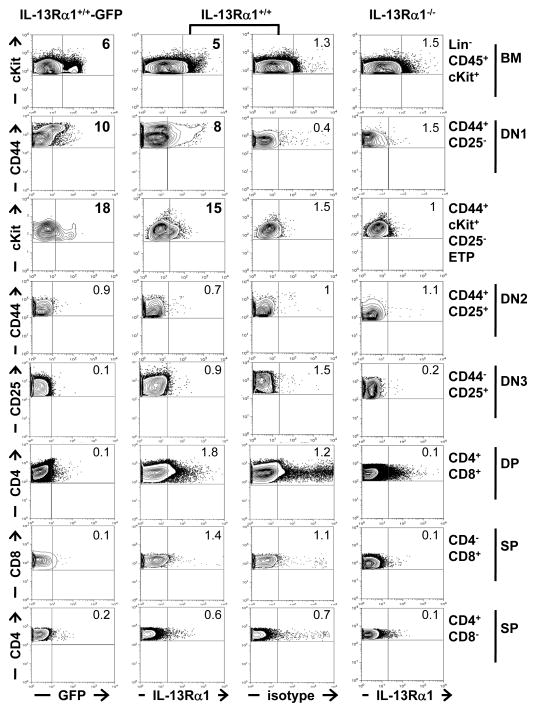

Given that the small cells expressing IL-13Rα1 in the thymus represent a minute population and that mature T cells do not express the receptor (13–15), we reasoned that they would be developing thymocytes or perhaps stem cell progenitors of bone marrow origin. To test this premise, we analyzed expression of the receptor on bone marrow cells and cells of the different stages of thymic development including the double-negative (DN), double-positive (DP) and single positive (SP) cells (2, 3, 8). Remarkably, a small population within the lineage-negative CD45-cKit-positive (Lin−CD45+cKit+) stem cell and progenitor niche harvested from the bone marrow displayed significant expression of IL-13Rα1 as detected by GFP (6%), a result that is supported by the positive staining with anti-IL-13Rα1 antibody (5%) (Figure 2, 1st row). BM cells from IL-13Rα1−/− deficient mice had background level of IL-13Rα1 expression similar to the isotype control used with IL-13Rα1+/+ BM cells (1.5% versus 1.3%). Furthermore, among the 3 DN stages, IL-13Rα1 protein was found exclusively on cells of the DN1 stage which is marked by CD44 but not CD25 (CD44+CD25−) expression (Figure 2, 2nd row). Indeed, IL-13Rα1 expression was observed on 10% of the CD44+CD25− DN1 cells as detected by GFP expression (Figure 2, 1st column). The staining with anti-IL-13Rα1 antibody supports the GFP data as IL-13Rα1 expression was observed on 8% of the CD44+CD25− population (2nd column) as compared to 0.4% for the isotype control (3rd column) or 1.5% for IL-13Rα1−/− DN1 cells (4th column). Since Lin−CD45+cKit+ BM stem cells express IL-13Rα1 and might seed the thymus with IL-13Rα1+ cells, we sought to determine whether the ETPs (cKit+CD44+CD25−) of the DN1 stage, which are presumed to be the earliest settling cells in the thymus (7, 8), also express IL-13Rα1. Interestingly, IL-13Rα1 was observed on 18% of the ETPs as determined by GFP expression and 15% by anti-IL-13Rα1 staining which is significantly higher than the 1.5% observed with the isotype control or 1% with IL-13Rα1−/− ETPs (Figure 2, 3rd row). Despite the fact that the DN1 cells are subject to different stage of sequential development, the cells of the DN2 and DN3 stages, as well as those of double and single positive stages, do not significantly express IL-13Rα1 (Figure 2). In fact, when the mean percentage of cells expressing IL-13Rα1 was compared to the controls, the values were statistically significant only for the BM, DN1 and ETP cells (Table 1) indicating that the receptor is expressed only at the initial DN1 stage. Moreover, the absolute number per thymus of IL-13Rα1+ DN1 cells was 835 ± 169 and among those only 417 ± 85 were IL-13Rα1+ ETPs expressing both cKit and CD44 while in the BM there was 2006 ± 157 IL-13Rα1+ Lin−CD45+ cells (Figure S1)4. These results indicate that IL-13Rα1 is expressed on lineage negative cells in the BM (Lin−CD45+cKit+) and the thymic DN1 cells.

Figure 2. IL-13Rα1 is expressed on bone marrow and thymic progenitors.

Thymic and bone marrow cells (depleted of Lin+ cells) from IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP, IL-13Rα1+/+ and IL-13Rα1−/− mice were stained with antibodies to CD4, CD8, CD25, CD44, cKit, and CD45 and analyzed for IL-13Rα1 expression by GFP (column 1) or staining with anti-IL-13Rα1 monoclonal antibody (column 2 and 4). Column 3 shows staining with isotype control for anti-IL-13Rα1 antibody. IL-13Rα1 expression was analyzed on the gated bone marrow (row 1) and thymic (rows 2–8) cells as indicated on the right of each row. The numbers indicate percent expression of IL-13Rα1 for each group. The data is representative of 7 individual mice. See also Figure S1.

Table I.

BM and thymic stem cells express significant levels of IL-13Ra1*

| % expression of IL-13Ra1

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| BM cells (Lin−CD45+)

|

DN1 cells (CD44+ CD25−)

|

ETP cells (CD44+cKit+CD25−)

|

|

| GFP+ | 6.8 ± 1.5% (p= 0.006)§ | 9.4 ± 3.9% (p= 0.004) | 20.8 ± 2.5% (p< 0.0001) |

| ā IL-13Ra1 mAb | 4.8 ± 0.4% | 10.1 ± 2.2% | 15.2 ± 0.3% |

| isotype | 1.2 ± 0.01% | 0.57 ± 0.5% | 1 ± 0.7% |

| IL-13Ra1−/− | 1.3 ± 0.4% (p= 0.002) | 1.2 ± 0.5% (p= 0.0002) | 0.8 ± 0.2% (p= 0.0001) |

The experiments in Figure 2 was repeated 7 times and the numbers presented in this table represent the mean ± SD of IL-13Ra1 expression as measured by GFP (GFP+) or stainining with anti-IL-13Rα1 antibody.

indicates statistical significance relative to GFP−cells from the same mouse using one way ANOVA. Anti-IL-13Ra1 staining was compared to both the isotype control and the staining of the same population from IL-13Ra1−/− mice with anti-IL-13Rα1 antibody.

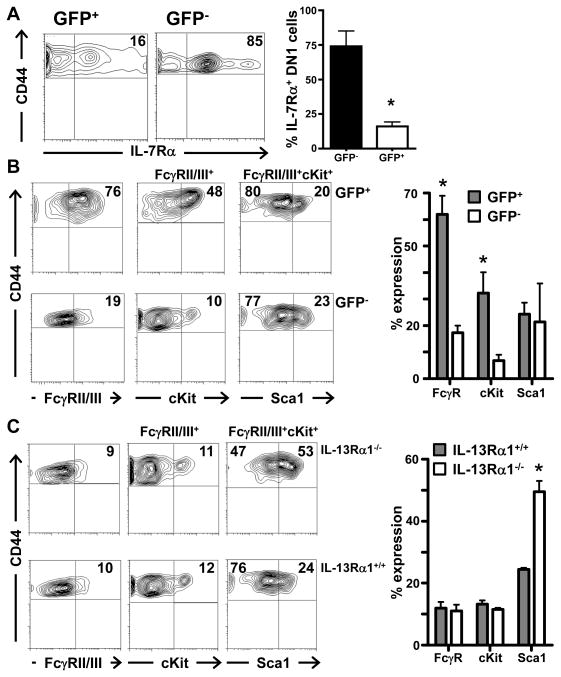

IL-13Rα1+ thymic DN1 cells display a myeloid progenitor phenotype

Given that IL-13Rα1 is usually expressed on myeloid but not lymphoid cells (13–15) and that both thymic and BM IL-13Rα1+ cells are lineage negative, it is logical to envision that the fraction of DN1 cells expressing IL-13Rα1 serves as progenitors for thymic-derived myeloid cells. Initially, we tested IL-13Rα1+ (GFP+) DN1 cells for the lack of IL-7Rα expression. The results indicated that GFP+ DN1 cells express significantly lower levels of IL-7Rα as compared to GFP− cells from the same IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP mice (Figure 3A). In fact, when the results of separate experiments were compiled, we found that 74 ±11% of the GFP− cells had significant IL-7Rα expression as compared to the percentage of GFP+ cells expressing IL-7Rα (16 ± 3.2%, p=0.0007). This suggests that the GFP−IL-7Rα+ cells may represent DN1e cells (25) while the GFP+ DN1 cells, whose IL-7Rα expression was at background levels, reflects more of an ETP phenotype (12). Subsequently, the GFP+ cells were sequentially analyzed for expression of markers associated with myeloid progenitors. The granulocyte macrophage progenitor (GMP), which gives rise to granulocytes and macrophages, represents one of the major myeloid progenitor populations that have so far only been described in the bone marrow (18, 19). GMPs usually express FcγRII/III and cKit (FcγRII/IIIhi/cKit+) but low Sca1 (18, 19). The results presented in Figure 3B indicated that GFP+ DN1 cells display a phenotype similar to BM-derived GMPs as FcγRII/III/cKit were high relative to GFP− cells while Sca1 was at the same low level on both cell types. In fact the compiled results of separate experiments show that 62 ± 12.1% of the cells expressed FcγRII/III, 32 ± 13.6% had cKit and only 24 ± 7.5% displayed Sca1 expression. In contrast, the GFP− DN1 counterparts had significantly lower FcγRII/III (17.3 ± 3.8%, p=0.016), cKit (6.7 ± 3.14%, p=0.021) and similar Sca1 (21 ± 14.4%, p=0.83) expression (Figure 3B). In order to determine the role IL-13Rα1 might play in the development of thymic GMPs, we analyzed expression of FcγRII/III, cKit and Sca1 on bulk (not GFP selected) thymic DN1 cells from IL-13Rα1-deficient (IL-13Rα1−/−) mice. Interestingly, the DN1 stage included a population of cells that was FcγRII/IIIhi and cKit+, equivalent to bulk DN1 cells from IL-13Rα1+/+ mice (Figure 3C). However, the FcγRII/IIIhicKit+ cells in IL-13Rα1+/+ mice had lower Sca1 expression (24%) relative to those from IL-13Rα1−/− mice (53%). Note that these percentages which were obtained with bulk DN1 cells (not GFP-sorted) are comparable to those observed in Figure 2 with the same population (Figure 2, row 2). The compiled results of separate experiments show that 11.9 ± 2.7% of the cells from IL-13Rα1−/− mice were FcγRII/IIIhi and 13.2 ± 1.7% had cKit which are similar to IL-13Rα1+/+ mice (11 ± 2.8% FcγRII/IIIhi and 11.5 ± 0.70% cKit+) while the FcγRII/IIIhicKit+ cells in IL-13Rα1+/+ mice had lower Sca1 expression (24.5 ± 0.71%) relative to those from IL-13Rα1−/− mice (49.5 ± 4.95%, p=0.0194) (Figure 3C). Since Sca1 is considered a marker of multipotency (26) and is downregulated by cells upon lineage commitment, the results are interpreted to mean that IL-13Rα1 is required for commitment to the GMP lineage. Overall, these results which were obtained with bulk, non-clonally expanded ex vivo cells indicate that the IL-13Rα1+ DN1 cells display a myeloid progenitor phenotype and require IL-13Rα1 to commit to such a phenotype.

Figure 3. IL-13Rα1+ DN1 cells manifest a GMP phenotype.

Thymocytes from IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP mice were stained with anti-CD44 and anti-CD25 antibodies. (A) the cells were also stained with anti-IL-7Rα antibody and receptor expression was analyzed on GFP+CD44+CD25− and GFP−CD44+CD25− cells. The contour plots show the results of a representative IL-7Rα expression experiment while the right panel shows the mean percent ± SD of IL-7Rα expression compiled from 6 separate experiments. *indicates statistical significance by Student’s t test. (B) the cells were also stained with anti-FcγRII/III, anti-cKit, and anti-Sca1 antibodies and the GFP+CD44+CD25− (GFP+) and GFP−CD44+CD25− (GFP−) cells were analyzed for expression of FcγRII/III (left panel), and the FcγRII/III+ cells were assessed for cKit (median panel) and those positive for FcγRII/III/cKit were analyzed for Sca1 expression (right panel). (C) thymocytes from IL-13Rα1+/+ and IL-13Rα1−/− mice were stained with anti-CD44, anti-CD25, anti-FcγRII/III, anti-cKit, and anti-Sca1 antibodies. CD44+CD25− cells were sequentially analyzed for expression of FcγRII/III (left panel), cKit (middle panel), and Sca1 (right panel) as in (B). The numbers indicate percent expression for each marker. In (B and C) the plots are representative experiments. The graphs to the right of B and C show the mean percent ± SD expression for each marker compiled from separate experiments. *indicates statistical significance by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test. P values are indicated in the text.

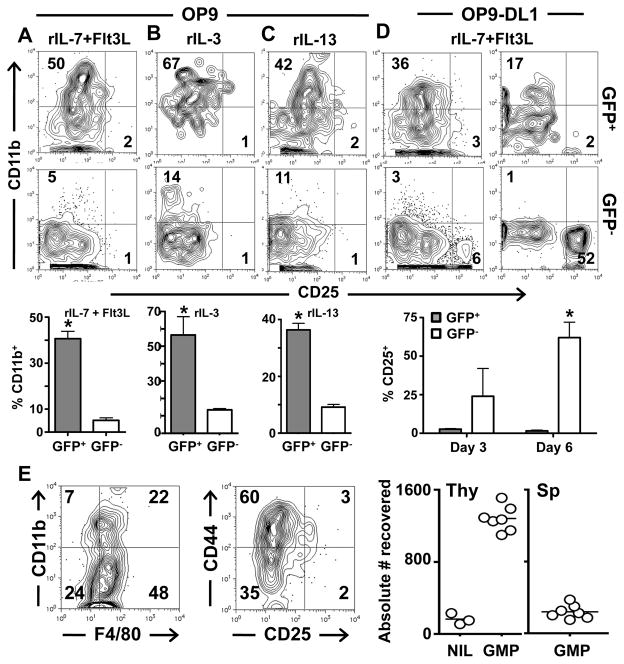

IL-13Rα1+ ETPs are committed to the myeloid lineage

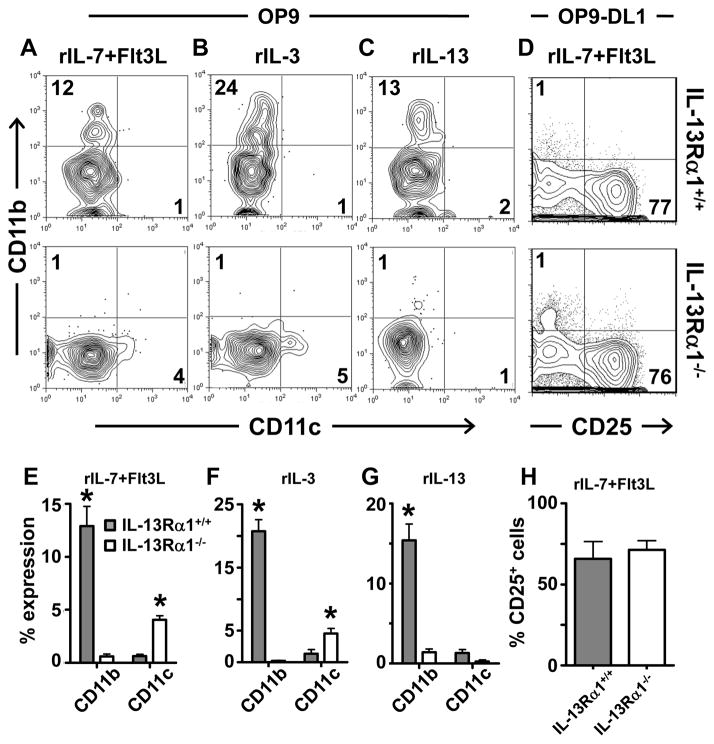

ETPs, which are considered the most immature thymic cells (8), can commit to the myeloid lineage (9, 10). Though the IL-13Rα1+ DN1 cells had low IL-7Rα, this does not preclude them from giving rise to lymphoid cells because lymphoid progenitors transiently down-regulate IL-7Rα upon arrival in the thymus (12). However, since these IL-13Rα1+ cells are at the DN1 stage, have low Sca1 expression and display a myeloid progenitor phenotype (Figure 3), it is logical to envision that these represent a population that commits to the myeloid rather than lymphoid lineage. To test this premise, we used the OP9 stromal cell in vitro culture system (21, 27, 28) and assayed the IL-13Rα1+ ETPs for maturation into the myeloid lineage. Accordingly, GFP− and GFP+ ETPs were sorted from the thymus of IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP mice, cultured on OP9 cells in the presence of hematopoietic cytokines and assessed for maturation into CD11b expressing myeloid cells. The results show that in the presence of rIL-7 and Flt3L, a milieu that has recently been shown to support differentiation into myeloid cells (9), the GFP+, but not the GFP− ETPs matured into myeloid cells and upregulated the lineage-specific CD11b (Mac1) marker (Figure 4A). A compilation of results shows a similar trend as 40 ± 3.2% of the GFP+, but only 5 ± 1.1% (p<0.0001) of the GFP− ETPs matured into CD11b+ myeloid cells. In response to rIL-3, a well-defined myeloid differentiation and survival cytokine (29, 30), the GFP+ ETPs readily matured into CD11b+ cells while the GFP− ETPs had much less CD11b expression (Figure 4B). In fact, 57 ± 10.5% of the GFP+ ETPs were CD11b+ as compared to 14 ± 0.74% (p=0.012) of the GFP− ETPs (Figure 4B). Importantly, but not surprisingly, the GFP+ ETPs (IL-13Rα1+), but not the GFP− ETPs (IL-13Rα1−) responded remarkably well to rIL-13 and matured into myeloid CD11b+ cells (Figure 4C). The compiled results of separate experiments show that 36 ± 2.3% of the GFP+ ETPs (IL-13Rα1+) upregulated CD11b as compared to only 9 ± 0.9% (p=0.0004) of the GFP− ETPs.

Figure 4. IL-13Rα1+ early thymic progenitors mature into myeloid but not lymphoid cells.

GFP−CD44+CD25−cKit+ (GFP−) and GFP+CD44+CD25−cKit+ (GFP+) ETPs were cultured on OP9 stroma for 3 days with (A) rIL-7 and Flt3L, (B) rIL-3, or (C) rIL-13. (D) the cells were cultured on OP9-DL1 stroma for 3 (left panel) or 6 (right panel) days with rIL-7 and Flt3L. The cultures were stained for CD45, 7AAD, CD11b and CD25 markers. The numbers represent the percent expression of CD25 and CD11b on CD45+7AAD− cells. The contour plots are representative of 6 independent experiments. The graphs show the mean percent ± SD expression for each marker. * indicates statistical significance by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test. P values are indicated in the text. (E) GFP+CD44+CD25−cKit+ cells from CD45.2+ IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP mice were injected intrathymically into CD45.1 IL-13Rα1+/+ mice (10,000 cells per mouse) and the CD45.2+GFP+ thymic cells were analyzed for expression of CD11b and F4/80 (left contour plot) and CD44 and CD25 (right contour plot). CD45.2+GFP+ cells were quantified in the thymus (Thy) and spleen (Sp) of mice recipient of GMPs or NIL (suspension media with no GMPs) (right panels). The numbers indicate percent expression of the indicated marker on CD45.2+GFP+ cells. The data are representative of 5 independent experiments with the graph representing individual recipient mice.

While these findings support prior reports indicating that ETPs can mature into myeloid cells (9, 10) they do not refute the potential of the IL-13Rα1+ ETPs to mature into lymphoid cells. It is well established that culture of ETPs on OP9-DL1 stromal cells in the presence of rIL-7 and Flt3L drives maturation into T cells (9, 21, 27, 28). These culture conditions, however, were unable to drive maturation of GFP+ ETPs into CD25+ cells upon short (3 days) or long (6 days) culture periods despite the fact that the GFP− counterparts began to up-regulate CD25 on day 3 and progressed optimally to the DN2 stage of thymic maturation by day 6 (Figure 4D). In fact, compiled results of separate experiments at day 3 of culture showed CD25 expression by only 2.7 ± 0.5% of GFP+ cells and by day 6 that value remained low at 1.5 ± 0.7%. In fact, later time points were unable to be analyzed as the viability of the GFP+ cells was lost. However, while the expression of CD25 by GFP− cells was highly variable (24 ± 18%) at day 3, by day 6, CD25 expression was at a significant level (62 ± 14%) supporting maturation to the DN2 stage.

In vivo, sorted GFP+ ETPs (cKit+CD44+CD25−) obtained from CD45.2+ mice were able to mature into myeloid but not lymphoid cells upon intrathymic injection into CD45.1+ mice by six days post transfer as 48% expressed the F4/80 macrophage lineage marker and 22% had both CD11b and F4/80 markers (Figure 4E, left panel). The cells, however, could not up-regulate the CD25 lymphoid marker (Figure 4E, median panel) supporting the lack of upregulation of CD25 shown in vitro (Figure 4D) and did not upregulate CD3 at any of the time points examined (not shown). Interestingly, the matured thymic myeloid cells remained in the thymus and did not circulate into the spleen (Figure 4E, right panel) perhaps to perform antigen presenting function for selection of developing thymocytes. The fact that IL-13Rα1+ ETPs commit only to myeloid cells in the polyclonal in vitro culture assays supports the in vivo data demonstrating that these ETPs have myeloid but no T cell potential. Overall, IL-13Rα1+ ETPs commit to myeloid but not lymphoid cells both in vitro and in vivo.

ETPs from IL-13Rα1−/− mice give rise to lymphoid but not myeloid cells

The DN1 population in IL-13Rα1-deficient mice had cells that expressed markers associated with the myeloid progenitor phenotype but did not down-regulate Sca1 indicating a lack of commitment to the myeloid lineage (Figure 3C). GFP− ETPs from IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP mice, which have the potential to express IL-13Rα1, also could not mature into myeloid cells even in the presence of favorable growth factors (Figure 4). This observation raises the question as to whether or not IL-13Rα1-expressing progenitors are the sole source of ETP-derived thymic myeloid cells. To examine this postulate, bulk ETPs (not GFP sorted) from IL-13Rα1+/+ and IL-13Rα1−/− mice were examined in vitro under polyclonal circumstances, the most telling condition for restriction to the generation of myeloid CD11b+ cells. Interestingly, while 12% of the ETPs from IL-13Rα1+/+ thymi were able to mature into CD11b+ cells in the presence of rIL-7 and Flt3L, only a marginal number (1%) of the ETPs from IL-13Rα1−/− thymi expressed CD11b (Figure 5A). Neither rIL-3 or rIL-13 were able to promote myeloid development in the IL-13Rα1−/− mice and CD11b expression remained at 1% while 24% and 13% of the cells from IL-13Rα1+/+ ETP cultures expressed CD11b, respectively (Figure 5B and C). Interestingly, maturation into CD11c-expressing dendritic cells did not occur with any culture condition in the IL-13Rα1+/+ mice as CD11c expression ranged between 1 to 2% most likely indicating that IL-13Rα1 does not support the differentiation of ETPs into CD11c-expressing conventional dendritic cells (Figure 5A–C top row). The IL-13Rα1-deficient ETPs yielded very few CD11c-expressing cells with rIL-7+Flt3L (4%) and rIL-3 (5%) but not rIL-13 (1%) (Figure 5A–C, bottom row). Although ETPs have been shown to mature into DCs (19), it is not clear whether IL-13Rα1-deficiency facilitates ETP maturation into CD11c+ cells. The compiled results of separate experiments showed a similar trend in the presence of rIL-7 and Flt3L, as 12± 3% of cells upregulated CD11b from cultured ETPs from IL-13Rα1+/+ mice while the culture of ETPs from IL-13Rα1−/− thymi had significantly lower (0.6 ± 0.4%, p= 0.002) CD11b expression (Figure 5E). In addition, rIL-3 and rIL-13 yielded CD11b expression on 21 ± 3.1% and 15 ± 3.6% in IL-13Rα1+/+ ETP culture which is significantly higher than the 0.2 ± 0.1% (p= 0.003) and 1.4 ± 0.6% (p=0.0136) observed with IL-13Rα1−/− ETP cultures respectively (Figure 5F and G). The compiled results also confirmed the data for CD11c expression.

Figure 5. IL-13Rα1−/− early thymic progenitors do not mature into CD11b+ cells.

ETPs(CD44+CD25−cKit+) were sorted from the thymus of IL-13Rα1−/− and IL-13Rα1+/+ mice and cultured on OP9 (A–C) or OP9-DL1 (D) cells for 3 days in the presence of rIL-7+Flt3L (A, D), rIL-3 (B), or rIL-13 (C). Subsequently, cells were stained for CD45, 7AAD, CD11b, CD25, and CD11c. Contour plots are representative of 3 independent experiments. The numbers indicate percent expression within the CD45+7AAD− population. (E, F, G, and H) show the mean percent ± SD expression for the markers analyzed in (A, B, C, and D), respectively. * indicates statistical significance by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test. P values are indicated in the text.

Finally, the bulk ETPs from IL-13Rα1−/− mice, which could not yield myeloid cells, gave rise to lymphoid cells in an equivalent manner as compared to bulk ETPs from IL-13Rα1+/+ mice which contain both GFP+ and GFP− cells (76% versus 77%) (Figure 5D). This is supported by the compiled results (compare 71 ± 9.9% to 66 ± 18.3%) suggesting that IL-13Rα1 does not play a significant role in thymic lymphoid differentiation and a lack of bipotency of this population. Taken together, these results indicate that ETPs require IL-13Rα1 for maturation into myeloid but not lymphoid cells.

IL-13Rα1+ thymic myeloid progenitors originate from the bone marrow

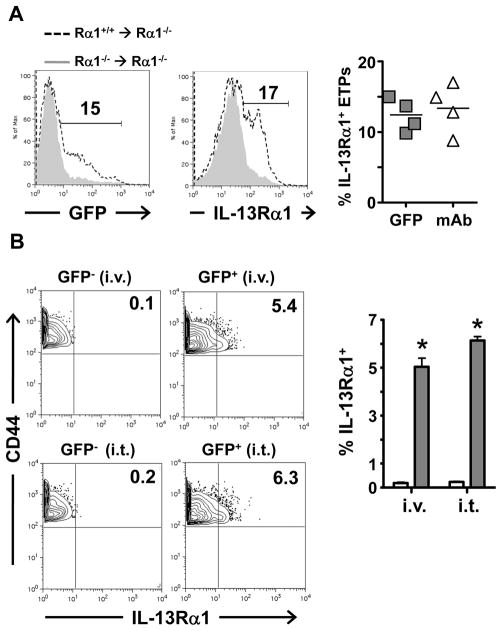

The thymic progenitors expressing IL-13Rα1 may arise as a result of differentiation of multipotent ETPs (9, 10, 31). However, given that a small fraction of Lin− BM cells were found to express the IL-13Rα1 chain (Figure 2) and that GFP− cells from IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP mice were unable to up-regulate the receptor in the presence of rIL-13 and differentiate into myeloid cells (Figure 4), it is likely that IL-13Rα1+ ETPs develop as a consequence of migration of Lin− IL-13Rα1+ bone marrow cells into the thymus. To test this postulate, bone marrow chimeras were prepared by transfer of Lin− IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP BM cells into lethally irradiated IL-13Rα1−/− mice and the hosts were assessed for the presence of IL-13Rα1+ ETPs in the thymus. The results show that lethally irradiated IL-13Rα1−/− mice recipient of Lin− BM cells from IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP mice (Rα1+/+ rarr; Rα1−/−), had 15 and 17% of ETPs expressing IL-13Rα1 as measured by GFP reporter (Figure 6A, left histogram) and staining with anti-IL-13Rα1 antibody (Figure 6A, right histogram), respectively. This is significant relative to the control chimeras recipient of Lin− BM cells from IL-13Rα1−/− mice (Rα1−/− → Rα1−/−). In fact, compilation of independent experiments supports the results as IL-13Rα1 expression was observed on 12.4 ± 2.3% and 13.4 ± 3.5% of ETPs from (Rα1+/+ → Rα1−/−) BM chimeras as measured by GFP expression and anti-IL-13Rα1 staining respectively (Figure 6A, right panel).

Figure 6. IL-13Rα1+ progenitors arrive in the thymus pre-committed.

(A) Bone marrow chimeras were generated by i.v. transfer of 10 × 106 Lin− bone marrow cells from IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP (Rα1+/+) or IL-13Rα1−/− (Rα1−/−) mice into lethally irradiated IL-13Rα1−/−mice and 7 days later the Rα1+/+→Rα1−/− and Rα1−/−→Rα1−/− chimeras were analyzed for IL-13Rα1 expression on the thymic ETP (CD44+CD25−cKit+) population by GFP (left histogram) and anti-IL-13Rα1 antibody (right histogram). The numbers represent percent expression among the CD44+CD25−cKit+ cells. The right scatter plot shows percent IL-13Rα1+CD44+CD25−cKit+ cells for individual experiments. (B) CD44+CD25−cKit+GFP− (GFP−) and CD44+CD25−cKit+GFP+ (GFP+) ETP cells were sorted from the thymus of IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP CD45.2 mice. Cells (15,000 per mouse) were injected i.v. or i.t. into CD45.1 mice and six days later the cells were collected and analyzed for expression of IL-13Rα1 by GFP. The contour plots show results of a representative experiment. The numbers represent percent expression among the CD44+CD25−cKit+CD45.2+ population. The bar graph show the mean percent ± SD expression for IL-13Rα1 expression compiled from 4 experiments. *indicates statistical significance by two-tailed, unpaired Student’s t test. P values are indicated in the text. See also Figure S2 and Figure S3.

The chemokine receptor CCR9 has been implicated in the trafficking of bone marrow stem cells to the thymus (32, 33). However, CCR9-independent mechanisms have also been proposed as CCR9 knockout BM stem cells are still able to traffic to the thymus (6, 33, 34). Given that the IL-13Rα1+Lin− bone marrow cells are able to traffic to the thymus, we sought to determine whether they express CCR9. Accordingly, IL-13Rα1+cKit+Lin− bone marrow cells were sorted and assessed for expression of CCR9 by RT-PCR. Interestingly, IL-13Rα1+ bone marrow cells did not express high levels of CCR9 as compared to the positive control of CD8+ T cells from the intra-epithelial layer of the small intestine (RQ of 0.58 ± 0.4 vs. 2.8 ± 0.5, respectively) (Figure S2). Overall, this suggests that IL-13Rα1+ cells migrate to the thymus perhaps by CCR9-independent mechanisms.

It has recently been suggested that thymic myeloid cells arise from bipotent macrophage-T cell progenitors (10, 35). Given that IL-13Rα1+ bone marrow cells had minimal CCR9 expression there is a possibility that the thymic IL-13Rα1+ ETPs arise from bipotent thymic IL-13Rα1− progenitors that are able to upregulate the receptor. To address this premise in vivo, CD45.2+ GFP− ETPs from IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP mice (which have the potential to up-regulate IL-13Rα1) were transferred either i.v. or intrathymically (i.t.) into CD45.1+ mice and tested for up-regulation of IL-13Rα1. The results show that the transferred GFP− cells did not upregulate IL-13Rα1 (Figure 6B). In fact, compiled data from separate experiments showed only 0.2 ± 0.05% GFP+ cells for i.v. and 0.2 ± 0.04% for i.t. transfer. When the transfer was performed with CD45.2+ GFP+ ETPs, significant levels of IL-13Rα1+ (GFP+) cells were detected within the ETP population whether the transfer was made i.v. (5 ± 0.5%, p = 0.0004) or i.t. (6 ± 0.2%, (p=0.0001). These results indicate that IL-13Rα1+ ETPs likely originate from Lin− IL-13Rα1+ BM cells rather than IL-13Rα1− thymic progenitors.

Furthermore, when Lin−IL-13Rα1+cKit+Sca1− (GFP+) bone marrow cells were cultured in vitro on OP9 cells, the GFP+ cells readily mature into myeloid CD11b+ but not lymphoid CD19+ B cells (43% compared to 1%, respectively) (Figure S3). In addition, when cultured on OP9-DL1 cells, which support T cell development, the GFP+ cells were unable to generate lymphoid cells as they did not upregulate CD25 (<1%) (Figure S3). Therefore, these data suggests that while IL-13Rα1+ BM cells give rise to myeloid cells, they lack both T and B lymphoid potential. Overall, IL-13Rα1+ early thymic progenitors, which mature into myeloid cells, likely derive from the BM.

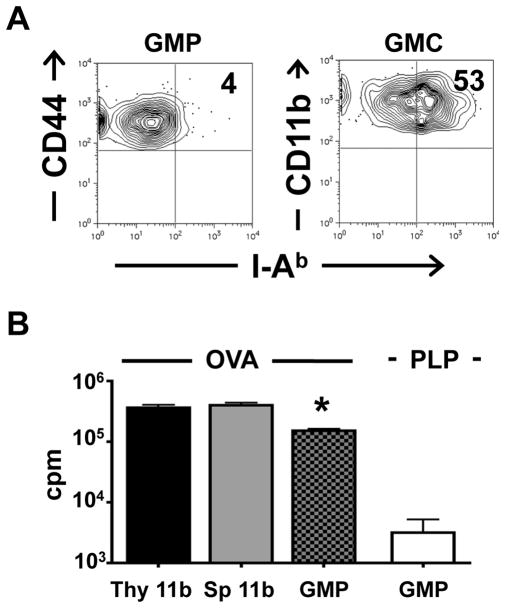

IL-13Rα1+ ETP-derived myeloid cells can function as antigen presenting cells

Antigen presenting cells that sustain thymic lymphocyte selection arise from both thymic and peripheral progenitors (36, 37). Given that the GFP+ ETPs readily mature into myeloid but not lymphoid cells that are retained in the thymus, it is logical to envision that they contribute presenting function in thymic T cell selection. Indeed, the IL-13Rα1+ ETPs (GMP) had minimal I-Ab class II molecules on their surface (4%) (Figure 7A). However, mature IL-13Rα1+ myeloid cells (CD11b+) derived from GFP+ ETPs (GMC) up-regulate I-Ab MHC class II molecules in a significant manner as 53% of the cells were MHC II-positive (Figure 7A). Furthermore, when GFP+ ETPs from IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP mice were matured on OP9 cells into myeloid cells and tested for presentation of ovalbumin (OVA) antigen, they were able to induce proliferation of OVA-specific TCR transgenic OT-II T cells (Figure 7B). In fact, the stimulation of the T cells by the GFP+ myeloid cells (GMP) was comparable to proliferation observed with mature CD11b+ thymic (Thy 11b) and spleen (SP 11b) cells. Also, the stimulation is specific as proliferation of OT-II T cells was significantly lower (152,100 ± 11,150 vs. 3,173 ± 2,024, p<0.0001) when the antigen was proteolipid protein (PLP). Thus, ETP-derived thymic myeloid cells are able to perform antigen presenting function.

Figure 7. IL-13Rα1+ ETP-derived thymic myeloid cells function as presenting cells.

(A) I-Ab expression was analyzed on GFP+CD44+CD25−cKit+ (GMP) as well as mature GFP+-CD11b myeloid cells (GMC). Data is representative of 4 independent experiments. (B) differentiated GFP+ cells (GMP) were cultured (1×104 cells/well) with OT-II T cells (2×105 cells/well) and 20μg/ml OVA or control PLP protein for 48h. CD11b+-sorted thymic (Thy 11b) and splenic (Sp 11b) myeloid cells were used as controls. 1μCi [3H]thymidine was added to each well for the last 14.5h of culture. Each bar represents the mean ± SD of triplicate wells. The data is representative of 3 independent experiments. *indicates statistical significance using one-way ANOVA (p<0.0001) when compared to GMP stimulated with the negative control PLP.

DISCUSSION

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are multipotent, self-renewing bone marrow cells that give rise to red and white blood cells (38). HSC differentiation begins with a loss of self-renewal (39) and progresses through a binary split model in which common lymphoid progenitors (CLP) are restricted to lymphoid lineages and common myeloid progenitors (CMP) are restricted to myeloid-erythroid lineages (40–42). Subsequent studies in fetal hematopoiesis identified progenitors that have potential for both T cell and myeloid lineages and proposed a myeloid-based model that further details the differentiation pathway before commitment to a specific lineage (10, 43). Currently it is believed that the relinquishing of pluripotency by stem cells and commitment to a specific lineage depends on inductive signals available at different sites and stages of differentiation (6, 44–46). For instance, chemokines such as CCR7 and CCR9 guide stem cell migration to the thymus (32, 33) and Notch receptor/ligand interactions facilitate commitment to the T cell lineage (46–48). Consequently, the earliest thymic progenitors may be heterogeneous (48–51) but are mostly restricted to the T cell lineage. Indeed, there have been reports showing generation in the thymus of B, NK and dendritic cells in addition to T cells (31, 49–51). More recently, it has been shown through clonal assays that myeloid cells such as granulocytes and macrophages can arise from ETPs (9, 10) suggesting that the myeloid-based model is operative in the thymus and ETPs remain bipotent (35, 49). Given that T cells originate from ETPs that previously expressed IL-7Rα (12) and the IL-13Rα1+ ETPs identified here are restricted to the myeloid-lineage with no T cell potential both in vivo and in vitro under polyclonal culture assays, the bipotency model may apply to rare ETPs. Distinct origin offers an alternative that can accommodate the generation of both myeloid and T cells from ETPs and the restriction of IL-7Rα reporter positive and IL-13Rα1+ ETPs to T cells and myeloid cells, respectively. A number of points support the separate origin postulate including the fact that IL-13Rα1− counterparts lack myeloid potential both in vivo and in vitro even under polyclonal culture conditions. While a small percentage of CD11b expression was observed when the GFP−ETPs were cultured in vitro with rIL-3 under polyclonal conditions, the in vivo experiments could not yield significant results to support the in vitro data. Contamination with GFP+ cells under non-physiological rIL-3 may have resulted in the small CD11b expression. Importantly, a small fraction of bone marrow stem cells that express IL-13Rα1 were able to migrate to the thymus, express an ETP phenotype while preserving IL-13Rα1 and mature into myeloid cells. Their IL-13Rα1− counterparts, however, were unable to give rise to myeloid cells. These findings indicate that the IL-13Rα1+ cells originate from the bone marrow and, like the IL-7Rα reporter positive cells (12), were committed to their lineage prior to migration to the thymus leading to heterogeneity in the ETP population (25). Again, these findings do not contradict the myeloid and T cell potential of ETPs (9, 10) as the culture systems could contain IL-13Rα1+ cells or rare bipotent cells. Given that in our polyclonal system, IL-13Rα1+ ETPs were myeloid specific both in vitro and in vivo, heterogeneity within the ETP population as a consequence of separate origin is a plausible explanation. Moreover, since the Lin−IL-13Rα1+cKit+Sca1− bone marrow cells lack B and T lymphoid potential in vitro, it is likely that the newly defined thymic myeloid progenitors are marked by expression of IL-13Rα1 and originate from the bone marrow rather than from thymic progenitors that up-regulate IL-13Rα1 in the thymus. In addition, while the cells can be driven to maturation with growth factors such as IL-3 or IL-7 and Flt3L, they were also able to differentiate in the presence of IL-13. This bodes well with the observations reporting that IL-13 is produced in the thymus by eosinophils of both neonatal and adult mice (52) and points to a role the cytokine might play in maintaining the GMP phenotype or serving as a differentiation factor for these progenitors. In light of the findings that in IL-13Rα1−/− mice the GMPs remained uncommitted with a phenotype similar to the Lin−cKit+Sca1+ bone marrow stem cells, it is possible that IL-13 contributes both survival and differentiation functions to the IL-13Rα1+ ETP cells. Finally, while the IL-13Rα1+ ETPs did not express MHC class II molecules, the myeloid cells derived from these cells did, remained in the thymus as mature cells, and were able to present antigen to T cells. This function likely plays a significant role in T cell development and the GFP+ ETPs may restore CD4 T cell selection in MHC II-deficient mice. The biological significance of the presence of macrophages in the thymus was considered to be clearance of the large number of apoptotic, negatively selected T cells (11). This study demonstrates an additional role for thymic macrophages as antigen presenting cells that are likely involved in the development of T cells. Also, these ETP-derived macrophages perhaps perform additional or complementary functions relative to circulating peripherally derived macrophages.

Overall, the study indicates that ETPs are heterogeneous and identifies IL-13Rα1-positive BM cells as the source of ETPs that give rise to macrophages able to perform antigen presenting function and perhaps contribute to T cells development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

J.C. Zuniga-Pflucker, A. Bhandoola and Jeremiah Bell for the gift of OP9 and OP9-DL1 cells.

Funding. This work was supported by grants RO1 NS057194, RO1AI048541, and R21HD060089 (to H.Z.) from the National Institutes of Health. D.M.T. and J.A.C. were supported by Life Sciences Fellowships from the University of Missouri, Columbia. C. M. H. was supported by a training grant GM008396 from NIGMS.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BM, bone marrow; CLP, common lymphoid progenitor; CMP, common myeloid progenitor; DC, dendritic cell; DN, double negative; DP, double positive; ETP, early thymic progenitor; FLT3L, fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand; GMP, granulocyte-macrophage progenitor; HSCs, Hematopoietic stem cells; Lin, lineage; PLP, proteolipid protein; SP, single positive

The online version of this article contains supplemental material.

Author contributions are as follows. CLH performed the experiments and data analysis; FBG generated the IL-13Rα1+/+-GFP mouse, assisted in cell sorting and discussion; JAC assisted in the experiments and data discussion; JCH generated the IL-13Rα1−/− mouse; MD and JCH generated the anti-IL-13Rα1 monoclonal antibody; XW, CMH, SZ, LMR, DMT, and AMV aided in manuscript discussion. HZ wrote the manuscript and directed the project.

References

- 1.Godfrey DI, Kennedy J, Suda T, Zlotnik A. A developmental pathway involving four phenotypically and functionally distinct subsets of CD3-CD4-CD8- triple-negative adult mouse thymocytes defined by CD44 and CD25 expression. J Immunol. 1993;150:4244–4252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Boehmer H. Positive selection of lymphocytes. Cell. 1994;76:219–228. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90330-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benz C, V, Martins C, Radtke F, Bleul CC. The stream of precursors that colonizes the thymus proceeds selectively through the early T lineage precursor stage of T cell development. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1187–1199. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsuzaki Y, Gyotoku J, Ogawa M, Nishikawa S, Katsura Y, Gachelin G, Nakauchi H. Characterization of c-kit positive intrathymic stem cells that are restricted to lymphoid differentiation. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1283–1292. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.4.1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Godfrey DI, Zlotnik A, Suda T. Phenotypic and functional characterization of c-kit expression during intrathymic T cell development. J Immunol. 1992;149:2281–2285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhandoola A, von Boehmer H, Petrie HT, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. Commitment and developmental potential of extrathymic and intrathymic T cell precursors: plenty to choose from. Immunity. 2007;26:678–689. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allman D, Sambandam A, Kim S, Miller JP, Pagan A, Well D, Meraz A, Bhandoola A. Thymopoiesis independent of common lymphoid progenitors. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:168–174. doi: 10.1038/ni878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shortman K, Wu L. Early T lymphocyte progenitors. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:29–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bell JJ, Bhandoola A. The earliest thymic progenitors for T cells possess myeloid lineage potential. Nature. 2008;452:764–767. doi: 10.1038/nature06840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wada H, Masuda K, Satoh R, Kakugawa K, Ikawa T, Katsura Y, Kawamoto H. Adult T-cell progenitors retain myeloid potential. Nature. 2008;452:768–772. doi: 10.1038/nature06839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esashi E, Sekiguchi T, Ito H, Koyasu S, Miyajima A. Cutting Edge: A possible role for CD4+ thymic macrophages as professional scavengers of apoptotic thymocytes. J Immunol. 2003;171:2773–2777. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.6.2773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlenner SM, Madan V, Busch K, Tietz A, Laufle C, Costa C, Blum C, Fehling HJ, Rodewald HR. Fate mapping reveals separate origins of T cells and myeloid lineages in the thymus. Immunity. 2010;32:426–436. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graber P, Gretener D, Herren S, Aubry JP, Elson G, Poudrier J, Lecoanet-Henchoz S, Alouani S, Losberger C, Bonnefoy JY, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Gauchat JF. The distribution of IL-13 receptor alpha1 expression on B cells, T cells and monocytes and its regulation by IL-13 and IL-4. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:4286–4298. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199812)28:12<4286::AID-IMMU4286>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee HH, Hoeman CM, Hardaway JC, Guloglu FB, Ellis JS, Jain R, Divekar R, Tartar DM, Haymaker CL, Zaghouani H. Delayed maturation of an IL-12-producing dendritic cell subset explains the early Th2 bias in neonatal immunity. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2269–2280. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li L, Lee HH, Bell JJ, Gregg RK, Ellis JS, Gessner A, Zaghouani H. IL-4 utilizes an alternative receptor to drive apoptosis of Th1 cells and skews neonatal immunity toward Th2. Immunity. 2004;20:429–440. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(04)00072-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muller U, Stenzel W, Kohler G, Werner C, Polte T, Hansen G, Schutze N, Straubinger RK, Blessing M, McKenzie AN, Brombacher F, Alber G. IL-13 induces disease-promoting type 2 cytokines, alternatively activated macrophages and allergic inflammation during pulmonary infection of mice with Cryptococcus neoformans. J Immunol. 2007;179:5367–5377. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeda K, Kamanaka M, Tanaka T, Kishimoto T, Akira S. Impaired IL-13-mediated functions of macrophages in STAT6-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1996;157:3220–3222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iwasaki H, Akashi K. Myeloid lineage commitment from the hematopoietic stem cell. Immunity. 2007;26:726–740. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu L, Liu YJ. Development of dendritic-cell lineages. Immunity. 2007;26:741–750. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Legge KL, Min B, Potter NT, Zaghouani H. Presentation of a T cell receptor antagonist peptide by immunoglobulins ablates activation of T cells by a synthetic peptide or proteins requiring endocytic processing. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1043–1053. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.6.1043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schmitt TM, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. Induction of T cell development from hematopoietic progenitor cells by delta-like-1 in vitro. Immunity. 2002;17:749–756. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Osawa M, Hanada K, Hamada H, Nakauchi H. Long-term lymphohematopoietic reconstitution by a single CD34-low/negative hematopoietic stem cell. Science. 1996;273:242–245. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vicente R, Adjali O, Jacquet C, Zimmermann VS, Taylor N. Intrathymic transplantation of bone marrow-derived progenitors provides long-term thymopoiesis. Blood. 2010;115:1913–1920. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-229724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaur D, Hollins F, Woodman L, Yang W, Monk P, May R, Bradding P, Brightling CE. Mast cells express IL-13R alpha 1: IL-13 promotes human lung mast cell proliferation and Fc epsilon RI expression. Allergy. 2006;61:1047–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2006.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porritt HE, Rumfelt LL, Tabrizifard S, Schmitt TM, Zuniga-Pflucker JC, Petrie HT. Heterogeneity among DN1 prothymocytes reveals multiple progenitors with different capacities to generate T cell and non-T cell lineages. Immunity. 2004;20:735–745. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krueger A, von Boehmer H. Identification of a T lineage-committed progenitor in adult blood. Immunity. 2007;26:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Pooter R, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. T-cell potential and development in vitro: the OP9-DL1 approach. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmitt TM, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. T-cell development, doing it in a dish. Immunol Rev. 2006;209:95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00353.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Askew DS, Ihle JN, Cleveland JL. Activation of apoptosis associated with enforced myc expression in myeloid progenitor cells is dominant to the suppression of apoptosis by interleukin-3 or erythropoietin. Blood. 1993;82:2079–2087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keller JR, Ihle JN. Unique pathway of IL-3-driven hemopoietic differentiation. J Immunol. 1989;143:4025–4033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benz C, Bleul CC. A multipotent precursor in the thymus maps to the branching point of the T versus B lineage decision. J Exp Med. 2005;202:21–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uehara S, Grinberg A, Farber JM, Love PE. A role for CCR9 in T lymphocyte development and migration. J Immunol. 2002;168:2811–2819. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.6.2811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zlotoff DA, Sambandam A, Logan TD, Bell JJ, Schwarz BA, Bhandoola A. CCR7 and CCR9 together recruit hematopoietic progenitors to the adult thymus. Blood. 2010;115:1897–1905. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-237784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schwarz BA, Sambandam A, Maillard I, Harman BC, Love PE, Bhandoola A. Selective thymus settling regulated by cytokine and chemokine receptors. J Immunol. 2007;178:2008–2017. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chi AW, Bell JJ, Zlotoff DA, Bhandoola A. Untangling the T branch of the hematopoiesis tree. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li J, Park J, Foss D, Goldschneider I. Thymus-homing peripheral dendritic cells constitute two of the three major subsets of dendritic cells in the steady-state thymus. J Exp Med. 2009;206:607–622. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Porritt HE, Gordon K, Petrie HT. Kinetics of steady-state differentiation and mapping of intrathymic-signaling environments by stem cell transplantation in nonirradiated mice. J Exp Med. 2003;198:957–962. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spangrude GJ, Heimfeld S, Weissman IL. Purification and characterization of mouse hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 1988;241:58–62. doi: 10.1126/science.2898810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Adolfsson J, Borge OJ, Bryder D, Theilgaard-Monch K, Astrand-Grundstrom I, Sitnicka E, Sasaki Y, Jacobsen SE. Upregulation of Flt3 expression within the bone marrow Lin(−)Sca1(+)c-kit(+) stem cell compartment is accompanied by loss of self-renewal capacity. Immunity. 2001;15:659–669. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00220-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kondo M, Scherer DC, King AG, Manz MG, Weissman IL. Lymphocyte development from hematopoietic stem cells. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:520–526. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00227-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akashi K, Traver D, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature. 2000;404:193–197. doi: 10.1038/35004599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kondo M, I, Weissman L, Akashi K. Identification of clonogenic common lymphoid progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Cell. 1997;91:661–672. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80453-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu M, Kawamoto H, Katsube Y, Ikawa T, Katsura Y. The common myelolymphoid progenitor: a key intermediate stage in hemopoiesis generating T and B cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:3519–3525. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Enver T, Heyworth CM, Dexter TM. Do stem cells play dice? Blood. 1998;92:348–351. discussion 352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Metcalf D. Lineage commitment and maturation in hematopoietic cells: the case for extrinsic regulation. Blood. 1998;92:345–347. discussion 352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rothenberg EV. Negotiation of the T lineage fate decision by transcription-factor interplay and microenvironmental signals. Immunity. 2007;26:690–702. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuan JS, Kousis PC, Suliman S, Visan I, Guidos CJ. Functions of notch signaling in the immune system: consensus and controversies. Annu Rev Immunol. 2010;28:343–365. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sambandam A, Maillard I, Zediak VP, Xu L, Gerstein RM, Aster JC, Pear WS, Bhandoola A. Notch signaling controls the generation and differentiation of early T lineage progenitors. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:663–670. doi: 10.1038/ni1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kawamoto H. A close developmental relationship between the lymphoid and myeloid lineages. Trends Immunol. 2006;27:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heinzel K, Benz C, Martins VC, Haidl ID, Bleul CC. Bone marrow-derived hemopoietic precursors commit to the T cell lineage only after arrival in the thymic microenvironment. J Immunol. 2007;178:858–868. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmitt TM, Ciofani M, Petrie HT, Zuniga-Pflucker JC. Maintenance of T cell specification and differentiation requires recurrent notch receptor-ligand interactions. J Exp Med. 2004;200:469–479. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Throsby M, Herbelin A, Pleau JM, Dardenne M. CD11c+ eosinophils in the murine thymus: developmental regulation and recruitment upon MHC class I-restricted thymocyte deletion. J Immunol. 2000;165:1965–1975. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.