Abstract

Objectives

Adiponectin (APN) system malfunction is causatively related to increased cardiovascular morbidity/mortality in diabetic patients. The aim of the current study was to investigate molecular mechanisms responsible for APN transmembrane signaling and cardioprotection.

Methods and Results

Compared to wild type (WT), Cav-3 knockout (Cav-3KO) mice exhibited modestly increased myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (increased infarct size, apoptosis, and poorer cardiac function recovery, P<0.05). Although the expression level of key APN signaling molecules were normal in Cav-3KO, the cardioprotective effects of APN observed in WT were either markedly reduced or completely lost in Cav-3KO. Molecular and cellular experiments revealed that AdipoR1 co-localizes with Cav-3, forming AdipoR1/Cav-3 complex via specific Cav-3 scaffolding domain binding motifs. AdipoR1/Cav-3 interaction is required for APN-initiated AMPK-dependent and AMPK-independent intracellular cardioprotective signalings. More importantly, APPL1 and adenylate cyclase (AC), two immediately downstream molecules respectively required for AMPK-dependent and AMPK-independent signaling, form a protein complex with AdipoR1 in a Cav-3 dependent fashion. Finally, pharmacological activation of both AMPK plus PKA significantly reduced myocardial infarct size and improved cardiac function in Cav-3KO animals.

Conclusion

Taken together, these results demonstrated for the first time that Cav-3 plays an essential role in APN transmembrane signaling and APN anti-ischemic/cardioprotective actions.

Keywords: Diabetes, Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion, Adipocytokine, Signaling Mechanism

Ischemic heart disease is the leading cause of death in patients with diabetes. Hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia not only cause vascular injury resulting in myocardial ischemia, but also directly adversely impact ischemic cardiomyocytes, causing larger infarct size, and more severe heart failure after myocardial ischemia1. Defining the molecular basis linking diabetes and ischemic heart disease may help in identifying novel therapeutic targets that will not only reduce myocardial infarction (MI) risk, but also decrease cardiovascular mortality in diabetic patients.

Adiponectin (APN) is an adipocytokine secreted from adipose tissue. Clinical and experimental studies have demonstrated the potency of APN as an endogenous cardiovascular protective molecule. Reduced APN levels in type-2 diabetic patients not only contribute to increased vascular injury and MI morbidity, but also play a causative role in increased cardiomyocyte death, and greater mortality in diabetic individuals post MI2–5. However, knowledge of the molecular mechanisms responsible for APN-induced cardiomyocyte protection against MI injury remains elusive. More importantly, although several putative APN receptors have been proposed, transmembrane signaling mechanisms responsible for APN’s cardiomyocyte-protective effect remain undefined.

Caveolae are small, flask-like invaginations of the plasma membrane that create signaling microdomains, thereby providing spatial and temporal organization of cellular signaling events. Caveolins, the structural proteins found in caveolae, serve as scaffolds and regulators of signaling proteins6. Many signaling molecules compartmentalize within caveolae and interact with the scaffolding domain of caveolins. Numerous studies have demonstrated caveolin scaffolding domain (CSD) binding inhibits the function of multiple caveolar proteins involved in cell growth and proliferation7. Thus, caveolin has been generally recognized as a signal inhibitor and a potent growth suppressor. However, recent studies have suggested that insulin signaling may be an exception, which requires the presence of caveolin for transmembrane signaling8. Numerous studies have demonstrated that APN shares many biological functions with insulin, including glucose uptake, lipid oxidation and cardiovascular protection9, 10. However, the role of caveolin in APN transmembrane signaling, i.e., functioning as either an inhibitor or activator, has never been previously investigated.

Therefore, the aims of the present study were to 1) determine the role of Cav-3 (the predominant form of caveolin expressed in cardiomyocytes) in the cardioprotective actions of APN, and 2) investigate the molecular mechanisms responsible for Cav-3 regulation of APN transmembrane signaling.

Materials and Methods

All experiments were performed on adult (8–10 weeks) male Cav-3 knockout mice (Cav-3KO) or male wild type littermate controls (WT). Generation and characterization of Cav-3KO mice have been previously described11. The experiments were performed in adherence with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines on the use of Laboratory Animals, and were approved by the Thomas Jefferson University Committee on Animal Care.

Mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane, and myocardial ischemia (MI) was produced by temporarily exteriorizing the heart via a left thoracic incision and placing a 6-0 silk suture slipknot around the left anterior descending coronary artery5. Twenty minutes after MI, animals were randomized to receive either vehicle or globular domain of adiponectin (gAPN, 2 μg/g, IP)5. After 30 minutes of MI, the slipknot was released, and the myocardium was reperfused for 3 hours or 24 hours (cardiac function and infarct size only). All assays were performed utilizing tissue from ischemic/reperfused area or area-at-risk (AAR) identified with Evens blue negative staining.

Cardiac function was determined by echocardiography (VisualSonics VeVo 770) and left ventricular (LV) catheterization (Millar 1.2-Fr micromanometer) methods 24 hours after reperfusion prior to chest reopening5. Myocardial apoptosis was determined by caspase-3 activity and expressed as nmol pNA/h/mg protein5. Total NOx content (SIEVER 280i chemiluminescence NO Analyzer), superoxide production (lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence), and nitrotyrosine content (ELISA) in cardiac tissue were determined as we previously published12–14. Sucrose density membrane fractionation, immunoblotting, co-immunoprecipitation, adult mouse cardiomyocyte culture and confocal microscopic analysis were all performed using standard methods from our laboratory5 or other investigators. Detail methods for all above described assays as well as the methods for plasmid production and cell transfection are provided as online supplementation.

All values in the text and figures are presented as means±SEM of n independent experiments. All data (except Western blot density) were subjected to two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferoni correction for post-hoc test. Western blot densities were analyzed with the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test. Probabilities of 0.05 or less were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Knockout of Cav-3 modestly increased MI/R injury but virtually abolished the cardioprotection of APN

In order to definitively determine the role of Cav-3 in APN-mediated cardioprotection, the effect of APN upon myocardial infarct size was determined in Cav-3KO mice and their WT littermates. As summarized in Figure 1A, administration of APN 10 minutes before reperfusion significantly decreased infarct size in WT mice (P<0.01). Compared to WT mice, Cav-3KO mice exhibited moderately increased infarct size (P<0.05). Most importantly, administration of APN to Cav-3KO mice only slightly reduced infarct size. A highly significant difference in infarct size between APN-treated WT mice and APN-treated Cav-3KO mice was observed (P<0.01). The loss of APN-mediated protection in Cav-3KO mice cannot be attributed to reduced APN concentration in these animals (P<0.05)11, as treatment with a tripled dose of APN (i.e., 6 μg/g body weight) remained ineffective in reducing infarct size. Moreover, the loss of APN cardioprotection in Cav-3KO mice cannot be explained by a modestly larger infarct size observed in Cav-3KO mice, because we have recently demonstrated that APN is highly effective in protecting heart from MI/R injury in APN knockout mice, an animal model in which infarct size is even larger than that seen in Cav-3KO mice5. Finally, to determine whether Cav-3 is also required for cardioprotective action of full length APN, HEK cell-produced full length APN (>80% in HMW format as certified by the manufacturer, BioVendor, Candler, NC) was administered at 10 μg/g (a dose that exerts comparable cardioprotection in WT animal as 2 μg/g globular APN). As summarized in Online Figure 1, the cardioprotective effect of full length APN observed in WT mice was virtually abolished in Cav-3KO animals. These results demonstrated that Cav-3 is an essential molecule in APN-mediated cardioprotection.

Figure 1.

Knockout of Cav-3 abolished APN’s infarct size sparing effect (A), markedly blunted APN’s anti-apoptotic effect (B), and abolished APN’s cardiac functional improvement effect as determined by LVEF (C,D) and ±dP/dtmax (E,F). N=12–15/group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. respective vehicle group; &P<0.05, &&P<0.01 vs. WT mice with the same treatment. in ischemic/reperfused heart. N=12–15/group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. respective vehicle group; &P<0.05, &&P<0.01 vs. WT mice with the same treatment.

Apoptosis plays a critical role in MI/R injury. To determine whether Cav-3 is also required in APN-mediated anti-apoptotic signaling, the effect of APN upon MI/R-induced caspase-3 activation was determined. Compared to WT mice, MI/R-induced caspase-3 activation was significantly increased in Cav-3KO mice. More importantly, the anti-apoptotic effect of APN observed in WT mice was markedly, although not completely, blocked in Cav-3KO mice (Figure 1B). The difference in caspase-3 activity between APN-treated WT and APN-treated Cav-3KO mice was markedly significant (P<0.01).

Echocardiography and left ventricular catheterization were utilized 24 hours after reperfusion to ascertain whether the beneficial effects of APN upon cardiac function were Cav-3 dependent. As illustrated in Figure 1C and summarized in Figure 1D, MI/R caused greater left ventricular (LV) dysfunction in Cav-3KO mice than WT (P<0.05). Although APN treatment significantly improved LV function in WT mice, the same treatment failed to improve LV function to significant extent in Cav-3KO mice (Figure 1C/D). As seen with echocardiography, Cav-3KO mice manifested significantly poorer cardiac function by LV catheterization, as evidenced by higher left ventricular end diastolic pressure and lower ±dP/dtmax (Figure 1E/F). Treatment of WT mice with APN significantly reduced LVEDP (P<0.01) and improved ±dP/dtmax (P<0.01). However, the beneficial effects of APN upon cardiac function were either markedly reduced or completely lost in Cav-3KO mice. There was a highly significant difference in ±dP/dtmax between APN-treated WT mice and APN-treated Cav-3KO mice (Figure 1E/F).

APN signaling machinery is intact in Cav-3KO mice

The above results clearly demonstrate that Cav-3 is required for APN-mediated cardioprotective signaling. To determine the mechanisms responsible for the loss of APN-mediated cardioprotection in Cav-3KO mice, we first assessed the state of molecules requisite for physiologic APN biological signaling. No difference in cardiac expression of AdipoR1, AdipoR2, APPL1 (an adaptor protein containing a phosphotyrosine binding domain, a pleckstrin homology domain, and a leucine zipper motif), or AMP activated protein kinase (AMPK) was observed between WT and Cav-3KO mice (online Figure 1). These results demonstrate that the loss of APN-mediated cardioprotection in Cav-3KO mice cannot be attributed to the deficiency of key membrane or intracellular APN signaling molecules.

Co-localization and interaction of AdipoR1 and Cav-3 in adult cardiomyocytes

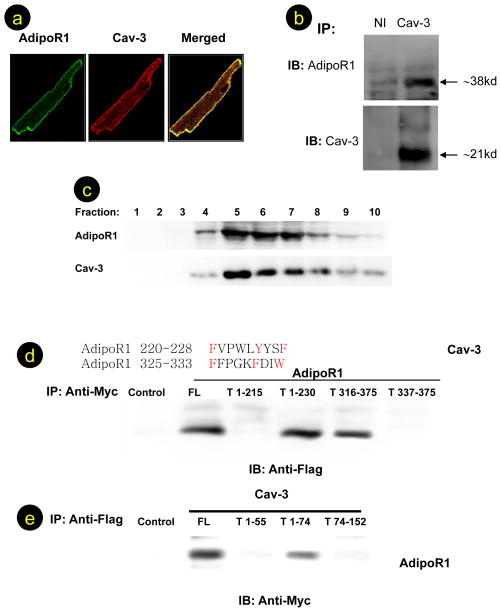

Previous studies have demonstrated that caveolin interacts with many membrane receptors. Recent studies have demonstrated that APN receptors are seven-transmembrane domain proteins, but with structural and topologic distinction from G-protein coupled receptors15. Having demonstrated that APN’s cardioprotection is abolished in Cav-3KO mice, we decided to test a novel hypothesis that interaction between AdipoR1, the predominant form of APN receptor in muscular cells, and Cav-3, the predominant form of caveolin in muscular cells, might be requisite for proper APN transmembrane signaling and cardioprotection. As illustrated in Figure 2A, AdipoR1 (green fluorescence) and Cav-3 (red fluorescence) were both confined to the plasma membrane. Image overlay demonstrates co-localization of AdipoR1and Cav-3 (yellow staining). The staining was specific for AdipoR1 and Cav-3, because substitution of nonimmune IgG for AdipoR1 antibody yielded only red plasma membrane staining, and substitution of Cav-3 antibody with nonimmune IgG resulted in only AdipoR1 green staining (data not shown). To determine whether there is an interaction between Cav-3 and AdipoR1, cardiac lysates were immunoprecipitated with an antibody directed against Cav-3 or a nonimmune IgG, and AdipoR1/Cav-3 proteins in the precipitates were detected by Western blot analysis. As illustrated in Figure 2B, neither AdipoR1 nor Cav-3 protein was detected when samples were immunoprecipitated with a nonimmune IgG (left lanes). However, AdipoR1 was detected in lysates immunoprecipitated with antibody against Cav-3 (right lanes). Similarly, when cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an antibody against AdipoR1, Cav-3 proteins were detected by Western blot analysis (data not shown). To confirm localization of AdiopR1 to caveolae and AdipoR1/Cav-3 complex formation in caveolae, a caveolae-rich detergent-resistant membrane fraction was prepared from adult heart tissues, and AdipoR1/Cav-3 distribution and interaction were detected by Western blotting and co-immunoprecipitation. As shown in Figure 2C, AdipoR1, and Cav-3 proteins were associated with the detergent-resistant membrane fraction. Moreover, AdipoR1/Cav-3 complex formation was clearly detected in the detergent-resistant membrane fraction (Online Figure 2, fractions 5–6), but not in detergent-soluble fractions (Online Figure 2, fractions 9–10).

Figure 2.

AdipoR1 co-localizes (A) and interacts with Cav-3 (B). AdipoR1 is distributed in caveolae-rich fraction in detergent-resistant (caveolae-rich) fraction (fraction 5–6), but not in detergent-soluble fractions (C). AdipoR1/Cav-3 interaction was detected in cells co-transfected with full length Cav-3 plus full length AdipoR1 (FL), truncated AdipoR11–230, or truncated AdipoR1316–375, but not in cell lysates expressing truncated AdipoR11–215 or truncated AdipoR1337–375 (D). AdipoR1/Cav-3 interaction was detected in cells co-transfected with full length AdipoR1 plus full length Cav-3 (FL) or truncated Cav-31–74, but not in cell lysates expressing truncated Cav-31–55 or truncated Cav-374–151 (E). For confocal microscopic examination, >100 cells were inspected per experiment, and cells with typical morphology are presented. For Western and co-immunoprecipitation, at least 6 samples from different tissue/cell culture dishes were examined and typical blots are presented.

AdipoR1 binds to Cav-3 scaffolding domain via specific Cav-3 interaction motif

Having demonstrated that AdipoR1 colocalizes and interacts with Cav-3, we further identified the specific domains responsible for AdipoR1/Cav-3 interaction. Previous experiments have demonstrated that membrane proteins interact with caveolin scaffolding domain via a specific caveolin-binding motif (ϕXϕXXXXϕ or ϕXXXXϕXXϕ, ϕ being an aromatic residue). Sequence analysis revealed two potential caveolin-binding motifs in AdipoR1 (220FVPWLYYSF228 and 325FFPGKFDIW333). To determine whether AdipoR1 binds Cav-3 via these specific motifs, vectors expressing myc-tag full length AdipoR1 (F) or truncated AdipoR1 (T, Online Figure 3) were co-transfected with flag-tag full length Cav-3 into 293T cells. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-myc antibody and immunoblotted with anti-flag antibody. As shown in Figure 2D, Cav-3 protein was detected in cell lysates expressing full length AdiopR1 (FL), truncated AdipoR11–230, or truncated AdipoR1316–375, but not in cell lysates expressing truncated AdipoR11–215 or truncated AdipoR1337–375. These results demonstrate that AdipoR1 interacts with Cav-3 via the specific Cav-3 binding motif.

Figure 3.

Knockout of Cav-3 abolished APN’s AMPK (A) and ACC (B) activation, and reduced its anti-nitrative effect (C). N=12–15/group. **P<0.01 vs. respective vehicle group; &P<0.05, &&P<0.01 vs. WT mice with the same treatment.

To further determine whether the Cav-3 scaffolding domain (residues 55–74) is required for AdipoR1 binding, vectors expressing full length Cav-3 (FL) or truncated (T, Online Figure 3) Cav-3 were co-transfected with myc-tag full length AdipoR1 into 293T cells. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-flag antibody, and immunoblotted with anti-myc antibody. As shown in Figure 2E, AdipoR1 protein was detected in cell lysates expressing full length Cav-3 or truncated Cav-31–74, but not in cell lysates expressing truncated Cav-31–55 or truncated Cav-374–151. These results demonstrate that AdipoR1 specifically binds to the Cav-3 scaffolding domain.

Cav-3 is required for both AMPK-dependent and AMPK-independent APN cardioprotection

We and others have previously demonstrated that APN protects cardiomyocytes from ischemia/reperfusion injury via AMPK-dependent metabolic regulation as well as AMPK-independent anti-oxidation/anti-nitration16. To further determine whether AdipoR1/Cav-3 interaction is required for AMPK-dependent and/or AMPK-independent intracellular cardioprotective signaling, the effect of APN upon AMPK phosphorylation and nitrotyrosine content (an index for APN’s AMPK-independent anti-oxidative/anti-nitrative properties17) were determined. As shown in Figures 3A and 3B, AMPK and ACC (acetyl-CoA carboxylase) phosphorylation was significantly increased after MI/R, and APN administration further augmented AMPK and ACC phosphorylation in WT mice. Basal levels of AMPK phosphorylation and MI/R-induced AMPK phosphorylation were both slightly reduced (not statistically significant) in Cav-3KO mice. Most importantly, administration of APN failed to induce AMPK and ACC phosphorylation in these mice (Figure 3A), indicating that Cav-3 is required for APN-induced AMPK activation.

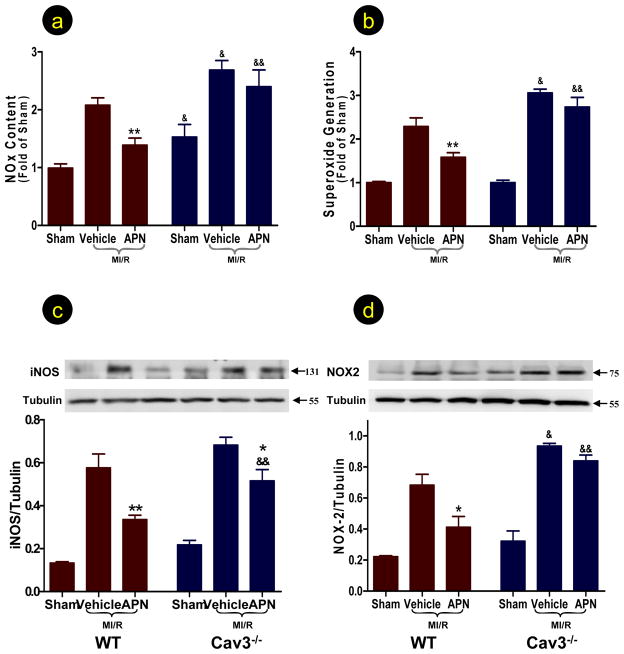

Treatment of WT mice with APN significantly reduced nitrotyrosine content in the ischemic/reperfused heart (Figure 3C). Basal nitrotyrosine content was unaltered, but ischemia/reperfusion-induced nitrotyrosine formation was significantly increased in Cav-3KO mice. Treatment of Cav-3KO mice with APN failed to reduce nitrotyrosine content in the ischemic/reperfused heart. To further determine the arm of peroxynitrite overproduction (i.e., overproduction of NO and/or superoxide) specifically inhibited by APN in a Cav-3 dependent fashion, NO/superoxide production and iNOS/NOX-2 (the prototypical and predominant form of NADPH oxidase in adult cardiomyocytes18) expression were determined. In WT mice, APN significantly reduced ischemia/reperfusion-induced NO/superoxide production (Figures 4A,B) and inhibited iNOS/NOX-2 expression (Figures 4C,D). Knockout of Cav-3 further aggravated ischemia/reperfusion-induced NO/superoxide production (Figure 4A,B), and elevated NOX-2 expression (Figure 4D). Ischemia/reperfusion induced iNOS expression was slightly increased in the Cav-3KO heart (Figure 4C). In Cav-3KO mice, the inhibitory effect of APN upon NO/superoxide production and NOX-2 overexpression was completely abolished, and the inhibitory effect of APN on iNOS expression was significantly blunted (Figure 4). Finally, congruent with previous reports, while basal eNOS expression was unchanged, eNOS phosphorylation was increased in Cav-3KO heart (Online Figure 4). However, APN-induced eNOS phosphorylation was abolished in Cav-3KO heart.

Figure 4.

Knockout of Cav-3 abolished APN’s anti-nitrative (determined by total NO production, A) and anti-oxidative (determined by superoxide production, B; and NOX expression, D) and markedly blunted APN’s anti-iNOS effect (C) in ischemic/reperfused heart determined 3 hours after reperfusion. N=12–15/group. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. respective vehicle group; &P<0.05, &&P<0.01 vs. WT mice with the same treatment.

AdipoR1 interacts with APPL1 and AC in largely Cav3-dependent fashion

Recent studies suggest that APPL1 and adenylate cyclase (AC) are respectively the most upstream signaling molecules in APN-induced AMPK activation and APN’s anti-oxidative signaling16. Having demonstrated that Cav-3 is required for both AMPK activation and anti-oxidative signaling of APN, we investigated the relationship between AdipoR1, Cav-3, APPL1, and AC to explore the potential mechanism responsible for Cav-3-depedent APN transmembrane signaling. Firstly, cardiac lysates were immunoprecipitated with an antibody against Cav-3, and immunoblotted with an antibody against APPL1 or AC. As illustrated in Figure 5A, Cav-3 interacts with these two proteins to form a protein complex. Secondly, cardiac lysates were immunoprecipitated with an antibody against AdipoR1 and immunoblotted with an antibody against APPL1 or AC. Interestingly, both AdipoR1/APPL1 and AdipoR1/AC complex formation were also detected (Figure 5B, Lane 1). Finally, and most importantly, AdipoR1/APPL1 and AdipoR1/AC interactions were markedly reduced in Cav-3KO cardiac tissue (Figure 5B, Lane 2, demonstrating >80% reduction in 5 repeated experiments).

Figure 5.

Cav-3 interacts with APPL1 (left) and AC (right) to form protein complex (A). AdipoR1/APPL1 and AdipoR1/AC complex formation were detected in tissue samples from WT (B, Lane 1). These interactions were markedly reduced in Cav-3KO cardiac tissue (Lane 2: >80% reduction in 5 repeated experiments). Administration of AICAR (an AMPK activator) plus db-cAMP (a cAMP mimic) significantly reduced infarct size (C) and improved cardiac function (D) in Cav-3KO mice.

Co-treatment with an AMPK activator and cAMP mimic significantly reduced MI/R injury in Cav-3KO mice

The aforementioned results strongly suggest that, via interaction with both AdipoR1 and its immediately downstream signaling molecules, Cav-3 plays an essential role in APN signaling complex formation. To obtain further evidence supporting this novel hypothesis, additional experiments were performed. WT littermates or Cav-3KO mice were subjected to MI/R as described above and treated with either vehicle or AICAR (an AMPK activator, 300 μg/g, IP) plus db-cAMP (a cAMP mimic, 25 μg/g, IP). Dosages of AICAR and db-cAMP were selected from previous publications, and confirmed in a pilot experiment demonstrating that treatment with these two compounds in Cav-3KO mice resulted in AMPK and PKA activation comparable to that seen in WT mice treated with APN (data not shown). As summarized in Figure 5C,D, although MI/R injury caused more severe injury in Cav-3KO than WT, AICAR/db-cAMP co-treatment remained highly effective in reducing infarct size and improving cardiac function in Cav-3KO mice. This result provided additional evidence that the loss of cardioprotection of APN in Cav3-KO mice is not the result of more severe MI/R injury in these animals.

T-Cadherin localizes in caveolae-rich membrane fraction of cardiomyocytes but does not interact with AdipoR1 or Cav-3

A recent study demonstrated that T-cadherin is critical for binding and protective functions of HMW adiponectin in cardiac myocytes19. To determine whether T-cadherin expression is changed in Cav-3KO mice and whether T-cadherin may interact with AdipoR1/Cav-3 complex, an additional experiment was performed. Interestingly, T-cadherin is distributed in detergent-insoluble, caveolae-rich membrane fraction (Figure 6A, top panel). However, T-cadherin expression was not changed in Cav-3KO heart (Figure 6A, second panel, left half). No interaction between T-cadherin and AdipoR1 or Cav-3 was detected (Figure 6A, second panel, right half).

Figure 6.

Comparison of T-cadherin expression in WT and Cav-3KO heart, and determination of T-cadherin distribution and its interaction with AdipoR1 or Cav-3 (A). Schematic illustration revealing the role of Cav-3 in APN signalsome formation and APN cardioprotective signaling (B). Solid lines: established signaling pathways; dashed lines: pathways requiring additional investigation; blue question mark: other intracellular APN signaling molecules that may also be “tethered” by Cav-3.

Discussion

APN regulates cellular function via binding and activation of adiponectin receptors (AdipoR), including AdipoR1 and AdipoR215. In addition to these two receptors, cell surface calreticulin (CRT)/CD91 co-receptor has been shown to be the molecule responsible for COX-2 activation by APN in endothelial cells20. Moreover, T-cadherin has been proposed to be a receptor for hexameric and high molecular weight forms of APN21. However, T-cadherin lacks an intracellular domain, and is mostly likely important in tethering high molecular weight APN isoforms upon the cell surface, thus allowing their interaction with other receptors19. The intracellular signaling of APN has been extensively investigated in recent years. At least three pathways, including the AMPK/acetyl-CoA carboxylase signaling axis22, AMPK/eNOS axis23, 24, and adenylate cyclase/cAMP/protein kinase-A signaling axis16, 17 have been reported. However, how the APN signal is transduced from its receptor(s) to intracellular effectors remains largely unknown. APPL1 is the only intracellular signaling molecule identified thus far with ability to shuttle signaling from AdipoR1 to intracellular effectors10, 25. However, questions remain incompletely answered. Although the phosphotyrosine binding (PTB) domain within APPL1 is absolutely required for APPL1/AdipoR1 interaction, no phosphorylated tyrosine residue is identified upon AdipoR1 either before or after APN receptor binding. Additionally, only one-way translocation of APPL1 (i.e., from membrane to cytosol but not reversely) has been observed after APN/receptor binding, suggesting that those APPL1 proteins already present in close proximity to AdipoR1 are the molecules responsible for APN signaling propagation from membrane to intracellular effectors.

The most important finding of the present study is that Cav-3 interacts with AdipoR1, as well as APPL1 (the most important molecule in APN’s AMPK-dependent signaling) and AC (the most important molecule in APN’s AMPK-independent signaling), forming a signaling complex (signalsome) within caveolae. By interacting with AdipoR1 and key intracellular APN signaling molecules, Cav-3 corrals such downstream molecules in close proximity with AdipoR1, thus enabling proper transmembrane signaling and cardioprotection (Figure 6B). Functionally, this AdipoR1/Cav-3 interaction is similar to that of the insulin receptor (IR)/caveolin interaction11, 26–28. However, difference exists. In Cav-1 knockout adipocytes, IR mRNA levels are not changed, but IR protein content is markedly decreased, suggesting that Cav-1 stabilizes IR and inhibits its degradation29. However, our present experiments yielded no significant change in AdipoR1/2 expression in Cav-3 KO cardiomyocytes at either the mRNA or protein level, suggesting the existence of more complex mechanisms responsible for Cav-3 regulation of AdipoR1 signaling.

Although both Cav-1KO and Cav-3KO mice manifest reduced insulin response, only Cav-3KO mice exhibit typical type-2 diabetic changes, including increased adiposity, decreased glucose uptake, reduced skeletal muscle glucose metabolic flux, and increased plasma leptin levels11. Importantly, older Cav-3 null mice develop pathologic cardiac phenotypes, including cardiac hypertrophy and heightened ERK1/2 activation. However, Cav-3KO mice at age 2 months (as in the current study) do not exhibit any myopathic changes11. Additionally, several recent studies have demonstrated that Cav-3 is positively involved in post-MI cardioprotection30–32. Moreover, although increased MI/R injury has been reported in both Cav-1KO and Cav-3KO mice in vivo, our most recent preliminary data obtained in cultured cardiomyocytes demonstrate that APN’s transmembrane signaling is impaired in Cav-3, but not Cav-1, knockdown cardiomyocytes. In contrast, Cav-1 knockdown in endothelial cells significantly blocks APN transmembrane signaling. Together, these results suggest that lack of Cav-1, an endothelial cell caveolin subtype, may increase MI/R injury indirectly by impairing blood flow restoration after reperfusion. In contrast, lack of Cav-3, a muscle-cell specific caveolin subtype, impairs APN transmembrane signaling in cardiomyocytes, directly augmenting MI/R injury.

It should be indicated that Cav-3KO markedly, but not completely, abolished all biological functions of APN, including a small portion of anti-apoptotic effect (Figure 1B) and AMPK activating effect (Figure 3C). A previous study has demonstrated that AdipoR1 interacts with APPL1 and activates AMPK25. As shown in Figure 5B, AdipoR1/APPL1 interaction is markedly reduced but not completely lost in Cav-3KO cardiomyocytes. The remaining (approximately 20%) direct AdipoR1/APPL1 could be responsible for the small portion of AMPK activation by APN in Cav-3KO mice. In addition, although AdipoR1 is the predominant adiponectin receptor expressed in cardiomyocytes, low levels of AdipoR2 are expressed in cardiomyocytes. Sequence analysis revealed that AdipoR2 contains one potential caveolin-binding motif that is located in its transmembrane domain. No significant AdipoR2/Cav-3 interaction was detected in our pilot experiment. A small portion of biological function of APN remaining in Cav-3KO mice could also be partially attributed to AdipoR2 activation and signaling. As systemic APN malfunction has been identified as a major risk factor for increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in type-2 diabetics, detailed elucidation of the signaling cascade mediated by the AdipoR1/Cav-3 interaction will not only gain comprehension of the APN signaling pathway and its regulation, but also provide valuable information on the design of new pharmacological interventions for clinically important diseases such as obesity and type-2 diabetes.

While this manuscript was in the final stages of preparation, an excellent study was published reporting that APN activates ceramidase in receptor-dependent fashion, initiating the pleiotropic actions of APN33. Our most recent experimental results demonstrate that although ceramidase is not a component of the Cav-3 centered APN signalsome during resting conditions, Cav-3 plays an essential role in APN-induced ceramidase recruitment and activation. Experiments identifying the role of Cav-3 in APN-initiated ceramidase recruitment/activation, and the involved detailed molecular mechanisms, are currently in progress.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding:

This research was supported by the following grants: NSFC 30900592, 81170199, ADA 1-11-JF56 (YJW), NIH HL-63828, HL-096686, and American Diabetes Association 7-11-BS-93 (XLM).

Footnotes

Disclosure:

None

References

- 1.Norhammar A, Lindback J, Ryden L, Wallentin L, Stenestrand U. Improved but still high short-and long-term mortality rates after myocardial infarction in patients with diabetes mellitus: a time-trend report from the Swedish Register of Information and Knowledge about Swedish Heart Intensive Care Admission. Heart. 2007;93:1577–1583. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2006.097956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Basu R, Pajvani UB, Rizza RA, Scherer PE. Selective Downregulation of the High Molecular Weight form (HMW) of Adiponectin in Hyperinsulinemia and in Type 2 Diabetes: Differential Regulation from Non-diabetic Subjects. Diabetes. 2007;56:2174–2177. doi: 10.2337/db07-0185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ouchi N, Shibata R, Walsh K. Cardioprotection by adiponectin. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006;16:141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shibata R, Sato K, Pimentel DR, Takemura Y, Kihara S, Ohashi K, Funahashi T, Ouchi N, Walsh K. Adiponectin protects against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through AMPK- and COX-2-dependent mechanisms. Nat Med. 2005;11:1096–1103. doi: 10.1038/nm1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tao L, Gao E, Jiao X, Yuan Y, Li S, Christopher TA, Lopez BL, Koch W, Chan L, Goldstein BJ, Ma XL. Adiponectin cardioprotection after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion involves the reduction of oxidative/nitrative stress. Circulation. 2007;115:1408–1416. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.666941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chidlow JH, Jr, Sessa WC. Caveolae, caveolins, and cavins: complex control of cellular signalling and inflammation. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;86:219–225. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwencke C, Braun-Dullaeus RC, Wunderlich C, Strasser RH. Caveolae and caveolin in transmembrane signaling: Implications for human disease. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;70:42–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishikawa Y, Otsu K, Oshikawa J. Caveolin; different roles for insulin signal? Cell Signal. 2005;17:1175–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg AH, Combs TP, Scherer PE. ACRP30/adiponectin: an adipokine regulating glucose and lipid metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:84–89. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00524-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hosch SE, Olefsky JM, Kim JJ. APPLied mechanics: Uncovering how adiponectin modulates insulin action. Cell Metabolism. 2006;4:5–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Capozza F, Combs TP, Cohen AW, Cho YR, Park SY, Schubert W, Williams TM, Brasaemle DL, Jelicks LA, Scherer PE, Kim JK, Lisanti MP. Caveolin-3 knockout mice show increased adiposity and whole body insulin resistance, with ligand-induced insulin receptor instability in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:C1317–C1331. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00489.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao F, Gao E, Yue TL, Ohlstein EH, Lopez BL, Christopher TA, Ma XL. Nitric oxide mediates the antiapoptotic effect of insulin in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion: the roles of PI3-kinase, Akt, and endothelial nitric oxide synthase phosphorylation. Circulation. 2002;105:1497–1502. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000012529.00367.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lund DD, Faraci FM, Miller FJ, Jr, Heistad DD. Gene transfer of endothelial nitric oxide synthase improves relaxation of carotid arteries from diabetic rabbits. Circulation. 2000;101:1027–1033. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.9.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ma XL, Gao F, Nelson AH, Lopez BL, Christopher TA, Yue TL, Barone FC. Oxidative inactivation of nitric oxide and endothelial dysfunction in stroke-prone spontaneous hypertensive rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:879–885. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kadowaki T, Yamauchi T, Kubota N, Hara K, Ueki K, Tobe K. Adiponectin and adiponectin receptors in insulin resistance, diabetes, and the metabolic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1784–1792. doi: 10.1172/JCI29126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldstein BJ, Scalia RG, Ma XL. Protective vascular and myocardial effects of adiponectin. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2009;6:27–35. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang Y, Gao E, Tao L, Lau WB, Yuan Y, Goldstein BJ, Lopez BL, Christopher TA, Tian R, Koch W, Ma XL. AMP-activated protein kinase deficiency enhances myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury but has minimal effect on the antioxidant/antinitrative protection of adiponectin. Circulation. 2009;119:835–844. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.815043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bedard K, Krause KH. The NOX Family of ROS-Generating NADPH Oxidases: Physiology and Pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:245–313. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Denzel MS, Scimia MC, Zumstein PM, Walsh K, Ruiz-Lozano P, Ranscht B. T-cadherin is critical for adiponectin-mediated cardioprotection in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4342–4352. doi: 10.1172/JCI43464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ohashi K, Ouchi N, Sato K, Higuchi A, Ishikawa TO, Herschman HR, Kihara S, Walsh K. Adiponectin promotes revascularization of ischemic muscle through a cyclooxygenase 2-dependent mechanism. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3487–3499. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00126-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hug C, Wang J, Ahmad NS, Bogan JS, Tsao TS, Lodish HF. T-cadherin is a receptor for hexameric and high-molecular-weight forms of Acrp30/adiponectin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10308–10313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403382101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Minokoshi Y, Ito Y, Waki H, Uchida S, Yamashita S, Noda M, Kita S, Ueki K, Eto K, Akanuma Y, Froguel P, Foufelle F, Ferre P, Carling D, Kimura S, Nagai R, Kahn BB, Kadowaki T. Adiponectin stimulates glucose utilization and fatty-acid oxidation by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Nat Med. 2002;8:1288–1295. doi: 10.1038/nm788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shibata R, Ouchi N, Kihara S, Sato K, Funahashi T, Walsh K. Adiponectin Stimulates Angiogenesis in Response to Tissue Ischemia through Stimulation of AMP-activated Protein Kinase Signaling. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:28670–28674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402558200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen H, Montagnani M, Funahashi T, Shimomura I, Quon MJ. Adiponectin stimulates production of nitric oxide in vascular endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45021–45026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao X, Kikani CK, Riojas RA, Langlais P, Wang L, Ramos FJ, Fang Q, Christ-Roberts CY, Hong JY, Kim RY, Liu F, Dong LQ. APPL1 binds to adiponectin receptors and mediates adiponectin signalling and function. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:518–523. doi: 10.1038/ncb1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez-Munoz E, Lopez-Iglesias C, Calvo M, Palacin M, Zorzano A, Camps M. Caveolin-1 loss-of-function accelerates GLUT4 and insulin receptor degradation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3493–3502. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oshikawa J, Otsu K, Toya Y, Tsunematsu T, Hankins R, Kawabe J, Minamisawa S, Umemura S, Hagiwara Y, Ishikawa Y. Insulin resistance in skeletal muscles of caveolin-3-null mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12670–12675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402053101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Otsu K, Toya Y, Oshikawa J, Kurotani R, Yazawa T, Sato M, Yokoyama U, Umemura S, Minamisawa S, Okumura S, Ishikawa Y. Caveolin gene transfer improves glucose metabolism in diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C450–C456. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00077.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen AW, Combs TP, Scherer PE, Lisanti MP. Role of caveolin and caveolae in insulin signaling and diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2003;285:E1151–E1160. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00324.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsutsumi YM, Horikawa YT, Jennings MM, Kidd MW, Niesman IR, Yokoyama U, Head BP, Hagiwara Y, Ishikawa Y, Miyanohara A, Patel PM, Insel PA, Patel HH, Roth DM. Cardiac-Specific Overexpression of Caveolin-3 Induces Endogenous Cardiac Protection by Mimicking Ischemic Preconditioning. Circulation. 2008;118:1979–1988. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.788331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horikawa YT, Panneerselvam M, Kawaraguchi Y, Tsutsumi YM, Ali SS, Balijepalli RC, Murray F, Head BP, Niesman IR, Rieg T, Vallon V, Insel PA, Patel HH, Roth DM. Cardiac-specific overexpression of caveolin-3 attenuates cardiac hypertrophy and increases natriuretic peptide expression and signaling. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:2273–2283. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsutsumi YM, Kawaraguchi Y, Horikawa YT, Niesman IR, Kidd MW, Chin-Lee B, Head BP, Patel PM, Roth DM, Patel HH. Role of Caveolin-3 and Glucose Transporter-4 in Isoflurane-induced Delayed Cardiac Protection. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:1136–1145. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d3d624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holland WL, Miller RA, Wang ZV, Sun K, Barth BM, Bui HH, Davis KE, Bikman BT, Halberg N, Rutkowski JM, Wade MR, Tenorio VM, Kuo MS, Brozinick JT, Zhang BB, Birnbaum MJ, Summers SA, Scherer PE. Receptor-mediated activation of ceramidase activity initiates the pleiotropic actions of adiponectin. Nat Med. 2011;17:55–63. doi: 10.1038/nm.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]