Abstract

The regulation of gene expression represents one of the most fundamental of biologic processes that controls cellular proliferation, differentiation, and function. Recent technological advances in genome-wide annotation together with bioinformatic/computational analyses have contributed significantly to our understanding of transcriptional regulation at the epigenomic and regulomic levels. This perspective outlines the techniques that are being utilized and summarizes a few of the outcomes.

Keywords: CHIP-CHIP ANALYSIS, CHIP-SEQ ANALYSIS, RNA-SEQ ANALYSIS, TRANSCRIPTION, EPIGENOME, HISTONE MODIFICATION, DISTAL REGULATION, COREGULATORS, RNA POLYMERASE, BACTERIAL ARTIFICIAL CHROMOSOMES (BAC), TRANSGENIC MICE

Introduction

Why study mechanisms of transcriptional regulation

The study of transcription involves delineating components, underlying processes, and regulatory mechanisms that converge to produce selective RNA subsets of the genome that are responsible for unique cellular phenotypes and/or functions. Why should these processes be explored in detail? At least three reasons come to mind. First, from a basic perspective, an appreciation of transcriptional mechanisms is central to our understanding of virtually all complex biologic processes, including those involving growth, differentiation, and adult homeostasis. How a single archival genome can be used selectively as a blueprint to encode over 200 different human cell types with widely divergent phenotypes and functions needs to be fully understood. Second, aberrant gene regulation underscores a wide variety of diseases; it is certain that basic and clinical research over the next few years will show that altered transcriptional control lies at the heart of a large number of complex polygenic diseases. Finally, it seems likely that as we gain greater insight into the regulatory pathways and mechanisms that underlie the expression of genes, opportunities will present themselves to apply these insights toward the development of more specific and selective therapeutics. Increased mechanistic understanding frequently reveals novel approaches to treating or curing many of the diseases that are likely to affect us during our lifetime.

Transcription

Summarizing the biochemical/molecular biologic era of transcription research

While transcription is regulated at multiple steps during RNA synthesis, it is formation of the initiation complex in eukaryotic cells that is perhaps most relevant to controlling the expression of genes and gene networks. In this regard, most basic researchers are familiar with the many techniques that have been used to explore the diverse and complex molecular mechanisms that govern these processes. Once interesting transcriptional targets are validated, studies often move toward examination of the promoters for those genes, identification of the molecular players, and elucidation of the mechanisms that underlie basal as well as regulated expression. Often these studies use chimeric promoter-reporter plasmids that can reveal the relative activity of promoters following transfection into host cells. These analyses, termed promoter bashing by those less intrigued with molecular mechanisms, seek to identify the regulatory regions that control the expression of genes and to ascertain the identity and nature of the interactions of the regulatory proteins involved. While a number of additional biochemical, cellular, and in vivo analyses are also used routinely, this overall approach has allowed investigators to conclude that gene expression depends on combinations of both basal transcriptional regulators and factors that are activated through autocrine, paracrine, and/or environmental signaling. These factors find their way to selected sites on target genes, where they recruit subsets of additional coregulatory complexes that mediate the downstream changes that are essential to altering rates of transcription. This summary outlines in the most simplistic of terms findings that have emerged during the last several decades of what we might call the biochemical and molecular biologic era’s of transcriptional research.

Limitations to traditional approaches to transcription

Given our overall progress in understanding gene expression, it may surprise some to learn that many of the techniques that have fundamentally molded our general understanding of transcription manifest striking limitations and suffer from significant bias. Perhaps the most important of these is our reliance on reporter plasmids, which, by virtue of their properties, generally have restricted mechanistic analyses to short regions (<3 kb) located proximal to target gene promoters. Only infrequently have investigators explored intronic or more distal regions, despite mounting evidence over the last several decades, much of it derived clinically, that control elements can be located significant distances from the genes they regulate.(1) An even more significant limitation has been our failure to appreciate the true impact of the chromatin state and the epigenome on gene regulation,(2) which, of course, remains undefined in plasmids introduced transiently into host cells. This could be one reason why activation of reporter plasmids often requires supplementation of key transcription and/or coregulatory factors that mediate downstream activity. Finally, reporter plasmids are also prone to additional regulatory artifacts as well, given the exceptionally high concentrations of reactive components that result following introduction into target cells. This limitation is equally significant for all biochemical protein-DNA and protein-protein interaction assays as well. In recent years, these and other limitations have eroded investigator confidence in many of the conclusions that have been drawn and have prompted a vigorous search for broader and more biologically relevant approaches to transcriptional research.

The transition to new and unbiased techniques: The genomic era

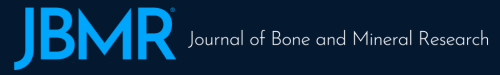

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis is likely the most transformative technique to have emerged as a result of the preceding, a methodology now familiar to most investigators.(3) As summarized in Fig. 1, ChIP analysis entails the preservation of natural protein-DNA interactions formed in intact cells using either mild isolation procedures or macromolecular cross-linking reagents such as formaldehyde followed by chromatin fragmentation using sonication. Selective immunoprecipitation then is conducted using an antibody to the protein or protein modification of interest. Finally, reversal of the formaldehyde-induced cross-links, coupled with DNA isolation, then permits quantitative measurement of the precipitated DNA fragments using the technique of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or quantitative PCR (qPCR). The abundance of a particular DNA fragment is correlated directly with the concentration of the immunoprecipitated factor or modification originally associated with DNA at that site. In this manner, the level of DNA modifications, histone modifications, transcription factors, coregulatory modules, RNA processing enzymes, and other related associations can be assessed following virtually any cellular treatment or perturbation.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the methodologies associated with ChIP, ChIP-chip, and ChIP-seq analyses at single gene as well as genome-wide levels. Conceptual examples of data analysis are provided for each technique.

As useful as this technique has been, however, it was the ability to evaluate this precipitated DNA in a fully unbiased manner across defined chromosomal regions and eventually across the entire genome using oligonucleotide or DNA fragment–spotted tiled microarrays (ChIP-chip analysis), as outlined in Fig. 1, that increased significantly the biologic impact that ChIP analysis has had on transcription research.(4,5) Interestingly, the utility of this particular genome-wide approach was exceptionally short-lived because the technique of massively parallel sequencing (eg, deep sequencing or next-generation sequencing) has rapidly become the method of choice for unbiased ChIP-derived DNA evaluation (Fig. 1).(6–8) Of course, both these techniques rely on the availability of accurately sequenced rodent and human genomes. It is safe to say that chromatin immunoprecipitation linked to deep sequencing methods (ChIP-seq analysis) and the subsequent bioinformatic analyses of these data sets(9) are fundamentally altering transcription research. Both single genes and entire genomes now can be queried easily for features that range from detection of extensive epigenetic modifications to the basal or induced appearance of a full assortment of regulatory transcription factors. The only absolute requirement for the technique is the availability of a fully characterized antibody. These methods, together with additional genome-wide analyses such as DNase I or micrococcal nuclease predigestion, coupled with deep sequencing(10,11) and with the emerging technique of quantitating gene expression via deep sequencing (RNA-seq analysis),(12) are lending new vigor to the field of transcription research, permitting full annotation of important genomes at both the epigenomic and regulomic levels. A summary of the applications and utility of these techniques can be found in Table 1. These efforts suggest that we have entered the genomic era of transcription research.

Table 1.

Properties and Capabilities of Techniques Described in This Perspective

| qPCR-ChIPa | ChIP-chipa | ChIP-seqa | RNA-seqb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scale | Single gene | Single gene, multiple gene, genome-wide | Genome-wide | Genome-wide |

| Technical skill | Moderate | High | High | High |

| Cost | Low | High | Very high | Very high |

| Bioinformatics/computing | Low | High | Very high | Very high |

| Equipment | Real-time PCR | Microarray and scanner hybridizer unit | Sequencing capabilities (Illumina, Solid, etc.) | Sequencing capabilities (Illumina, Solid, etc.) |

Applications:

DNA modifications, histones, histone modification, transcription factors, coregulators, RNA polymerase, other.

Transcription analysis, splicing, allele-specific expression.

New Insights

Defining the epigenomic layer of the genome

The epigenome

The epigenome represents a layer of potentially inheritable covalent modifications to the genome that is selectively imposed either directly on DNA sequences or indirectly on specific protein components of the genome, namely, a subset of the histones that together with 147 bp of DNA comprise the nucleosome.(13) These modifications are dynamic and represent both landmarks for key structural/informational features of the genome and indicators of relative DNA accessibility.(14,15) From a regulatory perspective, covalently marked structures include control elements (enhancers), promoters, transcription units, boundary elements, and numerous other components of the genome. Many, if not most, of these features can be identified via ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq analyses, which is why our understanding of the overarching principles of epigenomic regulation has progressed so rapidly during the past few years. Not surprisingly, the bulk of these epigenomic landmarks that highlight the presence of structural protein complexes or unique nucleosomal arrangements also can be detected through localized nuclease hypersensitivity. This concept is amply demonstrated at the genome-wide level, for example, using DNAse I digestion of isolated nuclei coupled with deep sequencing methods (digital DNAse I hypersensitivity analysis), as indicated earlier.(10) Interestingly, the results of these assays raise significant questions as to how certain structural/functional features of the genome are created in the first place. It is now clear that as a result of these genome-wide approaches, an increased understanding of the various aspects of the epigenome is now front and center in our efforts to decode the genome and to determine how genes are regulated during development, lineage progression, and cell differentiation.

Structural and functional epigenetic marks

As assessed by ChIP-seq analyses, what epigenetic marks specifically highlight structural features of genes? While a number of covalent modifications are imposed on DNA and/or histones, perhaps the most prevalent and best studied are those of methylation and acetylation. Methyl groups can be attached directly to cytosine to form 5-methyl cytosine.(16) This modification, imposed directly on DNA by a family of DNA methyl-transferases (DNMTs), occurs largely in CpG islands both at promoters and within genes, is reversible, can be inherited, and generally is known to represent a modification that confers repression. Methylation also occurs on the tails of histones. Subsets of these marks are associated with actively transcribed genes, repressed genes, or silenced regions of the chromosome; other modifications point to the presence of regulatory regions.(14) H3K4 monomethyl marks (H3K4me1), for example, denote enhancers; H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3) highlights promoters. Similarly, transcription units themselves can be defined by H3K36 trimethylation (H3K36me3), and other marks define exon-intron boundaries. Thus, although exceptions do occur, individual methylation marks can predict an underlying structural/functional feature that is informative with respect to the genes with which they are associated.

Histone acetylation is also a predominant feature of the epigenome.(17) Elevated levels of acetylation on histone H4K5, -K8, -K12, or -K16 and at sites on histone H3 that are imposed by histone acetyltransferases (HATs) generally are associated with decondensed or open chromatin states that control the accessibility of the underlying sequence to DNA-binding factors, remodeling complexes, or other associated regulatory complexes. These marks also provide a relative measurement of the transient changes that occur within a locus following activation or repression.(18) Finally, chromatin structure also can be modified by enzymes that use ATP to alter nucleosome position, organization, and/or composition, thereby increasing at very specific sites the accessibility of the underlying sequence or structure to regulatory complexes.(18,19)

Epigenome reversibility

Both histone acetylation and methylation are reversible. This occurs through the actions of histone deacetylatases (HDACs), lysine demethylases, and peptide arginine deiminases.(13) The functional consequences of these modifications are highly dynamic and flexible. Clearly, the process of imposing, reading, and erasing these instructional marks is fundamental to our understanding of the epigenome, as well as to its complex role in controlling gene regulation. Epigenetics is especially important in understanding the processes of cell fate determination and terminal differentiation. These processes are suspected to be dictated by lineage-determining factors that establish and epigenetically mark cell-specific repertoires of sites that permit the regulated expression of genes that are directly responsible for differentiated phenotypes.(20–22)

Defining aspects of the regulatory genome

The role of enhancers

Cellular phenotypes are determined through the absolute and relative expression of unique subsets of genes (the transcriptome) that comprise the genome. As mentioned earlier, the coordinated expression of these genes is orchestrated through a comprehensive collection of cis-acting regulatory elements that function as enablers either individually or synergistically. Consequently, it is the timely establishment of these sets of control elements that is ultimately responsible, at least in part, for cellular phenotype. Among this comprehensive genome-wide set of regulatory elements are more restrictive, overlapping subsets of elements (ie, enhancers, repressors, and silencers) that function to mediate the actions of individual sets of signaling-responsive transcription factors. Defining these specific subsets using ChIP-chip or ChIP-seq analysis has been termed cistrome analysis and entails the identification and quantitation of genome-wide groups of cis-active elements to which specific transcription factors bind in a specific cell type under a specific set of conditions (a cistrome).(23,24) The bulk of these cistrome analyses is focused on factors that are induced to bind to DNA. Follow-up studies using additional techniques then are able to assess the consequences of these binding events. Obviously, while genome-scale studies provide overarching insight into the activities of a particular factor and also can reveal exquisite detail into their activities at distinct gene loci, they are also able to identify new gene targets as well.

Cistromes and their functional properties

What has been learned about the sites of action of specific transcription factors across the genome using ChIP-chip or ChIP-seq analyses? Further, how do these insights conform to those developed using more traditional approaches summarized earlier in this Perspective? Although cistromes cannot be quantitated precisely, ChIP-seq-derived estimates of cistromes for DNA sequence–specific transcription factors range from several thousand to over 40,000 sites of interaction on the genome depending on the factor, the peak-finding tool used, the statistical cutoff level, and the cell type examined. The estrogen-induced estrogen receptor (ER) cistrome, for example, is estimated to comprise approximately 5000 sites in MCF-7 cells.(25) The vitamin D receptor (VDR) cistrome is approximately 8000 sites in bone cells(26) and approximately 2776 sites in an Epstein-Barr virus–transformed B cell line.(27) The RXR cistrome, on the other hand, is more extensive and strongly overlaps that of VDR cistrome(26) and the peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor γ (PPARγ) cistrome(28) depending on the activating cognate ligand. The cistromes for many other transcription factors also have been identified. Interestingly, and perhaps most significant, it is now clear that genes are largely regulated by multiple enhancers rather than single-promoter proximal elements. Perhaps more important, enhancers are also more frequently located within introns and at distal sites both upstream and downstream of the transcriptional start site rather than near the promoters they regulate. Indeed, these control regions can be tens if not hundreds of kilobases from their target promoters.

This principle is highlighted through numerous examples but perhaps most prominently by our recent discovery that the human CYP24A1 and the mouse Cyp24a1 genes, prototypic vitamin D targets, are regulated not only by two promoter-proximal vitamin D response elements (VDREs) discovered more than a decade earlier(29) but also by a cluster of intergenic enhancers located many kilobases downstream of these genes’ transcription units.(30) The RANKL,(31–34) VDR,(35,36) LRP5,(37) BMP2,(38) and SOST(39) genes, to name a few, are all similarly regulated by distal enhancers. Not surprisingly, de novo motif finding searches across these ChIP-defined peaks almost always reveal the presence of consensus-like sequences that represent the exact binding sites for the specific transcription factors being assessed. Thus the most common sequence element that occurs at sites to which activated ER binds consists of a typical estrogen response element,(25) whereas the most common sequence identified for VDR/RXR-binding sites is a typical VDRE.(26) Thus, while traditional approaches have allowed for the precise mapping and identification of DNA-binding-site sequences with which a factor interacts, they have failed to reveal what is now clear from ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq experiments that most genes are regulated through multiple enhancers that are located significant distances from the genes to which they are linked. These regulatory regions are also modular as well, able to bind multiple transcription factors selectively.

Coregulator patterns

A primary function of sequence-specific transcription factors is to recruit coregulatory machines that are essential to modulation of gene output. These coregulatory complexes often contain enzymes capable of histone acetylation and/or methylation or of nucleosome remodeling, as discussed earlier, thereby highlighting the link between transcription factor activity and epigenomic modulation. ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq studies now confirm that the binding of primary transcription factors is associated with the recruitment of molecular machinery in the form of coregulators such as the p160 HAT family, CBP/p300, NCoR, SMRT, histone deacetylases, mediator complex, and numerous others.(40) Unlike the conclusions drawn using plasmids, however, it is now apparent that the distinction between coactivators and corepressor is much less well defined. Indeed, SMRT, for example, is now known to be a strong coactivator of many estrogen-regulated genes.(41) It is also evident that coregulators of both classes (activators and repressors) can be present simultaneously in a single complex.(30) Finally, and perhaps most interesting, while a DNA-binding protein may interact at multiple sites near a gene, the recruitment of coregulators at these series of sites is not uniform.(30) Thus enhancers manifest unique activities and are likely to play different functional roles in the regulation of their target genes.

Epigenomic consequences of coregulator recruitment

Relative to the preceding, ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq analyses also have confirmed that the recruitment of coregulators has functional epigenomic consequences. Dynamic analysis of the level of histone H3 and H4 acetylation, while elevated within active genes, for example, is strongly induced by various cell stimulators. Strikingly, hormone-induced histone H3 and H4 acetylation patterns are broad, suggesting that the consequence of HAT activity radiates outward across a gene locus.(9) This upregulation of histone acetylation supports the idea that transcription factor binding to DNA and the recruitment of coregulators provoke a functional chromatin state that likely facilitates the expression of an associated gene(s). Since both basal and inducible levels of histone acetylation are indicative of gene activity, the search for these features together with additional epigenomic marks can highlight regions within a locus that are likely to play central regulatory roles.(42) We used this approach to identify enhancers that control the expression of Rankl, a gene whose regulation is highly complex.(34)

New roles for RNA polymerase II

ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq analyses also have revealed that transcription factor binding to enhancers facilitates the recruitment of RNA polymerase II (RNA pol II) not only to transcriptional start sites but also to enhancers and to other sites as well.(26,28,43) Additional components of the basal transcriptional machinery are also recruited to these sites. Why do these factors, which are essential to the transcription of genes, localize to enhancers? The data suggest several possibilities. First, one potential function of enhancers may be to increase the density of the RNA pol II enzyme available for transcription at a gene’s functional start site.(44) Second, the presence of basal transcriptional machinery at enhancers may provide an explanation for the discovery that much of the genome and particularly regions containing enhancers actively synthesize RNA.(45) The bulk of these non-protein-coding products is relatively small and entirely nuclear in nature. While some of these noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) are now easily recognizable (eg, miRNAs, siRNAs, and piRNAs) and their functions known, considerably longer RNAs (lncRNAs) also have been characterized.(46) Interestingly, many of these RNA products serve unique regulatory functions, controlling the abundance and activity of both nearby and more distal genes.(47) Indeed, evidence is accumulating that these RNA molecules may function in a regulatory fashion both in cis and in trans.(48,49) Thus the function of some enhancers may be intimately linked to an ability to transcribe regulatory RNAs. While ChIP analysis hinted at these possibilities early on, it was the application of ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq analyses that demonstrated the broad and ubiquitous nature of these RNA species across the genome.

Linking the Discovery of Enhancers to the Genes They Regulate

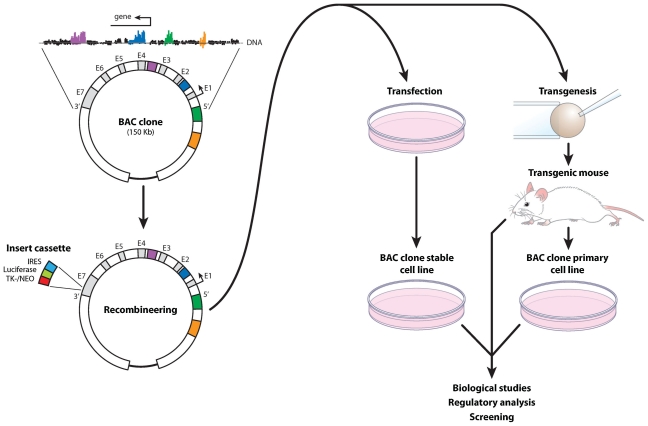

As is clear from the preceding discussion, while regulatory regions can be defined by ChIP-chip and ChIP-seq analyses and their activities probed in considerable detail, their distal locations make it extremely difficult to identify these enhancers’ target genes. Efforts to accomplish this difficult task are limited at present and relatively incomplete, particularly when the regulatory regions are located intergenically 100 kb or more from their suspected targets. Thousands of such distal regulatory regions exist within an individual genome, especially for genes that function in complex regulatory capacities, such as transcription factors, peptide hormones, growth factors, and cytokines. Three approaches have been taken to link regulatory regions with their cognate target genes. First, the expression and/or induction of a gene or genes located within an extended region containing the enhancer can provide the first clue. Confirmation may require deleting the enhancer in the context of a mouse model wherein loss or reduction of the regulation of the putative target gene can be assessed. This approach was used to test the relevance of an enhancer located 76 kb upstream and suspected of regulating the Rankl gene in response to parathyroid hormone and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3.(33,50) Second, one might determine whether an identified enhancer is or can localize to a nearby transcriptional start site using one or more versions of chromosome conformation capture analysis (termed 3C, 4C, or 5C).(51,52) In this technique, DNA enhancer segments located in 3D space near a cognate promoter are cross-linked more readily to this region of the gene (via protein-protein contacts) than those which are not located proximal to the same promoter. These cross-linked segments are also ligated together more efficiently than those which are not cross-linked. Thus cross-linked segments of DNA exhibit increased abundance when quantitated by PCR analysis using primers that cross segment boundaries. In addition, the association of a distal enhancer with a promoter is often regulated, providing added evidence linking an enhancer to its target gene. These analyses are difficult and labor-intensive, however, and strictly correlative in nature. Finally, we and others have used large bacterial artificial chromosomes (BAC clones) to assess the impact of an enhancer on a target gene when the putative target is within 200 to 300 kb of the regulatory region(30,33,38,53) (Fig. 2). In this case, recombineering techniques are used to introduce a reporter/internal ribosome entry site (IRES)/selectable marker cassette into the final 3′ noncoding exon of the gene of interest. The BAC clone then is stably introduced into cells in culture and evaluated for basal and inducible activities. The advantage here is that while in some respects analogous to the small plasmid technique, the DNA segment duplicates the entire endogenous gene locus and becomes fully integrated within the cellular genome. In some situations, BACs also can be integrated routinely into the same chromosomal site within the genome. Once a wild-type gene locus has been examined, additional BAC clones harboring mutations in the enhancer(s) of interest then can be generated and tested. Importantly, large DNA clones of this type also can be introduced as transgenes into mice, thereby permitting an assessment of the relevance of an identified enhancer in an in vivo setting(38) (Fig. 2). As is clear from this summary, none of these approaches is direct and straightforward, and all require considerable experimental effort. Nevertheless, establishing these types of enhancer/gene linkages now represents the major limiting step in the global analysis of mechanisms associated with transcription.

Fig. 2.

Schematic methodologies associated with BAC clone analysis in cells and transgenic mice. A BAC clone containing the gene of interest (top left) is subjected to recombineering techniques (lower left) to insert an IRES-luciferase reporter cassette containing a TK-neomycin gene–selectable marker into the noncoding portion of the gene’s final exon. The recombineered BAC clone then is used for stable transfection into host cells or inserted into the mouse genome as a transgene.

Disease Relevance

As discussed earlier, the idea that distal regulatory elements are linked to many disease states is well established. Indeed, multiple examples have been reported.(54) Relative to bone biology, perhaps the most striking is that of the SOST gene, which encodes sclerostin.(39) This protein functions through a direct interaction with the LRP5 and LRP6 coreceptors, thus antagonizing the anabolic Wnt signaling pathway essential to bone formation. Accordingly, the absence of expression of this gene leads to enhanced Wnt signaling and results in the progressive bone overgrowth disorders sclerosteosis and Van Buchem disease. Early genetic studies revealed that while the coding region of the SOST transcription unit was intact, a 52-kb deletion that eliminated SOST expression was present downstream of the SOST gene. Of particular relevance to this discussion, further studies defined a small, evolutionarily conserved 255-bp enhancer located within the confines of this deletion that was essential for SOST expression. Indeed, this enhancer contains a response element for the myocyte enhancer factor (MEF) family of transcription factors that was shown subsequently to be activated by MEF2A, -C, and -D.(39) This example highlights both the relevance of distal enhancers to the expression of specific bone genes and the consequences of genetic deletion of an enhancer on disease. It also provides a key example of an emerging opportunity for the development of a novel, potentially useful therapeutic. Two other examples are of interest. First, recent studies suggest the presence of both an active enhancer and a single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) within this enhancer that are located approximately 335 kb upstream of the c-MYC gene in a region associated with increase c-MYC expression and increased risk of prostate, colon, and breast cancer.(55–57) Interestingly, the SNP localizes to an active T-cell factor/β-catenin-binding site that is known to represent a primary driving force for cancer cell proliferation. Second, a single SNP has been found recently located downstream of the SORT1 gene in an enhancer that governs the latter’s expression.(58) This SNP alters C/EBP binding and thus the expression of SORT1. SORT1 modulates hepatic very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) secretion, and its expression therefore is essential to plasma low-density lipoprotein–cholesterol (LDL-C) and VLDL homeostasis. As a result, altered SORT1 expression may lead to an increased risk of myocardial infarction in humans. These represent only a few of the many examples where genetic changes point to the presence of distal regulatory elements that contribute to the expression of important genes whose altered activity may lead to increase risk of disease.

Summary

In this Perspective, new and widely applicable approaches such as ChIP-chip, ChIP-seq, and RNA-seq to the study of mechanisms associated with gene expression have been described. As opposed to the more traditional techniques that focus on genes one at a time, these methodologies are capable of addressing issues at single gene loci and, perhaps more important, on a genome-wide scale as well. These techniques are also capable of revealing new insight into the epigenome. Equally important, all these techniques are amenable to studies conducted both in vivo and in vitro. Thus detailed mechanistic studies are no longer restricted to cells grown in culture. Given these new approaches and the increased complexity that is now clearly apparent for most genes, the question arises as to whether the more traditional biochemical and molecular biologic approaches to the study of transcriptional regulation will remain relevant. While still useful in specific situations, it could be argued that their now fully recognized limitations will make them much less attractive as front-line techniques for the study of gene expression. Regardless of their usage, the characterization of transcriptional regulation likely will be approached more frequently in the future using the genome-scale methodologies, as exemplified by ChIP-chip, ChIP-seq, and RNA-seq analyses.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the contributions of Pike Laboratory members in the preparation of this article and Laura Vanderploeg in preparation of the figures. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants to the author.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The author states the he has no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Kleinjan DA, van Heyningen V. Long-range control of gene expression: emerging mechanisms and disruption in disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:8–32. doi: 10.1086/426833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hawkins R, Hon G, Ren B. Next-generation genomics: an integrative approach. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:476–486. doi: 10.1038/nrg2795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wells J, Farnham PJ. Characterizing transcription factor binding sites using formaldehyde crosslinking and immunoprecipitation. Methods. 2002;26:48–56. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos J, Dutta A, et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Squazzo S, O’Geen H, Komashko V, et al. Suz12 binds to silenced regions of the genome in a cell-type-specific manner. Genome Res. 2006;16:890–900. doi: 10.1101/gr.5306606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson D, Mortazavi A, Myers R, Wold B. Genome-wide mapping of in vivo protein-DNA interactions. Science. 2007;316:1497–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.1141319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valouev A, Johnson D, Sundquist A, et al. Genome-wide analysis of transcription factor binding sites based on ChIP-Seq data. Nat Methods. 2008;5:829–834. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer C, et al. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS) Genome Biol. 2008;9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pepke S, Wold B, Mortazavi A. Computation for ChIP-seq and RNA-seq studies. Nat Methods. 2009;6( 11 Suppl):S22–32. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hesselberth J, Chen X, Zhang Z, et al. Global mapping of protein-DNA interactions in vivo by digital genomic footprinting. Nat Methods. 2009;6:283–289. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sabo P, Kuehn M, Thurman R, et al. Genome-scale mapping of DNase I sensitivity in vivo using tiling DNA microarrays. Nat Methods. 2006;3:511–518. doi: 10.1038/nmeth890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Z, Gerstein M, Snyder M. RNA-Seq: a revolutionary tool for transcriptomics. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:57–63. doi: 10.1038/nrg2484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibney E, Nolan C. Epigenetics and gene expression. Heredity. 2010;105:4–13. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2010.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hon G, Hawkins R, Ren B. Predictive chromatin signatures in the mammalian genome. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:R195–201. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ernst J, Kellis M. Discovery and characterization of chromatin states for systematic annotation of the human genome. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:817–825. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fazzari M, Greally J. Introduction to epigenomics and epigenome-wide analysis. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;620:243–265. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-580-4_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacDonald V, Howe L. Histone acetylation: where to go and how to get there. Epigenetics. 2009;4:139–143. doi: 10.4161/epi.4.3.8484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramsey S, Knijnenburg T, Kennedy K, et al. Genome-wide histone acetylation data improve prediction of mammalian transcription factor binding sites. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2071–2075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.John S, Sabo P, Johnson T, et al. Interaction of the glucocorticoid receptor with the chromatin landscape. Mol Cell. 2008;29:611–624. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tronche F, Yaniv M. HNF1, a homeoprotein member of the hepatic transcription regulatory network. Bioessays. 1992;14:579–587. doi: 10.1002/bies.950140902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinz S, Benner C, Spann N, et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin Y, Jhunjhunwala S, Benner C, et al. A global network of transcription factors, involving E2A, EBF1 and Foxo1, that orchestrates B cell fate. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:635–643. doi: 10.1038/ni.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lupien M, Eeckhoute J, Meyer C, et al. FoxA1 translates epigenetic signatures into enhancer-driven lineage-specific transcription. Cell. 2008;132:958–970. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lupien M, Brown M. Cistromics of hormone-dependent cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:381–389. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carroll J, Meyer C, Song J, et al. Genome-wide analysis of estrogen receptor binding sites. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1289–1297. doi: 10.1038/ng1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer M, Goetsch P, Pike J. Genome-wide analysis of the VDR/RXR cistrome in osteoblast cells provides new mechanistic insight into the actions of the vitamin D hormone. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2010;121:136–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramagopalan S, Heger A, Berlanga A, et al. A ChIP-seq defined genome-wide map of vitamin D receptor binding: Associations with disease and evolution. Genome Res. 2010;20:1352–1360. doi: 10.1.1101/gr.107920.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nielsen R, Pedersen TA, Hagenbeek D, et al. Genome-wide profiling of PPARgamma:RXR and RNA polymerase II occupancy reveals temporal activation of distinct metabolic pathways and changes in RXR dimer composition during adipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2008;22:2953–2967. doi: 10.1101/gad.501108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zierold C, Darwish HM, DeLuca HF. Two vitamin D response elements function in the rat 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D 24-hydroxylase promoter. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1675–1678. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.4.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer M, Goetsch P, Pike J. A downstream intergenic cluster of regulatory enhancers contributes to the induction of CYP24A1 Expression by 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:15599–15610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim S, Yamazaki M, Zella LA, Shevde NK, Pike JW. Activation of receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand gene expression by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 is mediated through multiple long-range enhancers. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6469–6486. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00353-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim S, Yamazaki M, Shevde NK, Pike JW. Transcriptional control of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand by the protein kinase A activator forskolin and the transmembrane glycoprotein 130-activating cytokine, oncostatin M, is exerted through multiple distal enhancers. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:197–214. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fu Q, Manolagas SC, O’Brien CA. Parathyroid hormone controls receptor activator of NF-kappaB ligand gene expression via a distant transcriptional enhancer. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6453–6468. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00356-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bishop K, Meyer M, Pike J. A novel distal enhancer mediates cytokine induction of mouse RANKl gene expression. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:2095–2110. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zella LA, Kim S, Shevde NK, Pike JW. Enhancers located within two introns of the vitamin D receptor gene mediate transcriptional autoregulation by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1231–1247. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zella L, Meyer M, Nerenz R, Lee S, Martowicz M, Pike J. Multifunctional enhancers regulate mouse and human vitamin D receptor gene transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:128–147. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fretz J, Zella L, Kim S, Shevde N, Pike J. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 regulates the expression of low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 via deoxyribonucleic acid sequence elements located downstream of the start site of transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:2215–2230. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chandler RL, Chandler KJ, McFarland KA, Mortlock DP. Bmp2 transcription in osteoblast progenitors is regulated by a distant 3′ enhancer located 156.3 kilobases from the promoter. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:2934–2951. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01609-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leupin O, Kramer I, Collette N, et al. Control of the SOST bone enhancer by PTH using MEF2 transcription factors. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:1957–1967. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.070804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Malley B, Qin J, Lanz R. Cracking the coregulator codes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peterson T, Karmakar S, Pace M, Gao T, Smith C. The silencing mediator of retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptor (SMRT) corepressor is required for full estrogen receptor alpha transcriptional activity. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:5933–5948. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00237-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Heintzman ND, Stuart RK, Hon G, et al. Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nat Genet. 2007;39:311–318. doi: 10.1038/ng1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim T, Hemberg M, Gray J, et al. Widespread transcription at neuronal activity-regulated enhancers. Nature. 2010;465:182–187. doi: 10.1038/nature09033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szutorisz H, Dillon N, Tora L. The role of enhancers as centres for general transcription factor recruitment. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:593–599. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jacquier A. The complex eukaryotic transcriptome: unexpected pervasive transcription and novel small RNAs. Nat Rev Genet. 2009;10:833–844. doi: 10.1038/nrg2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guttman M, Amit I, Garber M, et al. Chromatin signature reveals over a thousand highly conserved large non-coding RNAs in mammals. Nature. 2009;458:223–227. doi: 10.1038/nature07672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang X, Song X, Glass C, Rosenfeld M. The long arm of long noncoding RNAs: roles as sensors regulating gene transcriptional programs. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003756.. pii:a003756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang X, Arai S, Song X, et al. Induced ncRNAs allosterically modify RNA-binding proteins in cis to inhibit transcription. Nature. 2008;454:126–130. doi: 10.1038/nature06992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsai M, Manor O, Wan Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA as modular scaffold of histone modification complexes. Science. 2010;329:689–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1192002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Galli C, Zella LA, Fretz JA, et al. Targeted deletion of a distant transcriptional enhancer of the receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand gene reduces bone remodeling and increases bone mass. Endocrinology. 2008;149:146–153. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dekker J, Rippe K, Dekker M, Kleckner N. Capturing chromosome conformation. Science. 2002;295:1306–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.1067799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Simonis M, Kooren J, de Laat W. An evaluation of 3C-based methods to capture DNA interactions. Nat Methods. 2007;4:895–901. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zella L, Meyer M, Nerenz R, Lee S, Martowicz M, Pike J. Multifunctional enhancers regulate mouse and human vitamin d receptor gene transcription. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24:128–147. doi: 10.1210/me.2009-0140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Noonan J, McCallion A. Genomics of long-range regulatory elements. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2010;11:1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-082509-141651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tuupanen S, Turunen M, Lehtonen R, et al. The common colorectal cancer predisposition SNP rs6983267 at chromosome 8q24 confers potential to enhanced Wnt signaling. Nat Genet. 2009;41:885–890. doi: 10.1038/ng.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ahmadiyeh N, Pomerantz M, Grisanzio C, et al. 8q24 prostate, breast, and colon cancer risk loci show tissue-specific long-range interaction with MYC. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:9742–9746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910668107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pomerantz M, Ahmadiyeh N, Jia L, et al. The 8q24 cancer risk variant rs6983267 shows long-range interaction with MYC in colorectal cancer. Nat Genet. 2009;41:882–884. doi: 10.1038/ng.403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Musunuru K, Strong A, Frank-Kamenetsky M, et al. From noncoding variant to phenotype via SORT1 at the 1p13 cholesterol locus. Nature. 2010;466:714–719. doi: 10.1038/nature09266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]