Abstract

Cervical cancer (CC) occurs more frequently in women who are immunosuppressed, suggesting that both local and systemic immune abnormalities may be involved in the evolution of the disease. Costimulatory CD28 and inhibitory CTLA-4 molecules expressed in T cells play a key role in the balanced immune responses. There has been demonstrated a relation between CD28, CTLA-4, and IFN genes in susceptibility to CC, suggesting their importance in CC development. Therefore, we assessed the pattern of CD28 and CTLA-4 expression in T cells from PB of CC patients with advanced CC (stages III and IV according to FIGO) compared to controls. We also examined the ability of PBMCs to secrete IFN-gamma. We found lower frequencies of freshly isolated and ex vivo stimulated CD4 + CD28+ and CD8 + CD28+ T cells in CC patients than in controls. Loss of CD28 expression was more pronounced in the CD8+ T subset. Markedly increased proportions of CTLA-4+ T cells in CC patients before and after culture compared to controls were also observed. In addition, patients’ T cells exhibited abnormal kinetics of surface CTLA-4 expression, with the peak at 24 h of stimulation, which was in contrast to corresponding normal T cells, revealing maximum CTLA-4 expression at 72 h of stimulation. Of note, markedly higher IFN-gamma concentrations were shown in supernatants of stimulated PBMCs from CC patients. Conclusions: Our report shows the dysregulated CD28 and CTLA-4 expression in PB T cells of CC patients, which may lead to impaired function of these lymphocytes and systemic immunosuppression related to disease progression.

Keywords: CD28, CTLA-4, T cell, Cervical cancer, Progression, Systemic immunosuppression

Introduction

Cervical cancer is one of the most common female malignancies in Polish women, accounting for 6.4% of female cancers. It is considered to be an important immunogenic tumor as the major risk factor for cervical cancer is infection with specific high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV). Although the incidence of genital HPV infections is very high, most of them recede without intervention. In most infected persons the HPV antigens and neoplastic cells permit the immune system to eradicate the infection [1]. In fact, about 10% to 20% of HPV infected individuals develop persistent infection and are at high risk for progression to high-grade cervical intraepithelial disease characterized by progressive ability to resist anti-viral immune defenses. Only in a limited number of patients does high-risk HPV infection cause multistep carcinogenesis in normal cervical cells. These relatively few cancer cases might reflect a population with ineffectively induced anti-tumor immunity, predisposing to cancer progression [1]. Indeed, HPV-induced carcinogenesis and rapid progression of the disease was shown to be associated with exposure to immunosuppressive agents or HIV infection [2]. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and cervical cancer occur more frequently in women who are immunosuppressed, suggesting that both local and systemic immune mechanisms may be involved in the evolution of these diseases [3, 4]. In contrast, the majority of HPV-positive cervical dysplastic lesions have been reported to resolve spontaneously in immune competent hosts [5].

The increased frequency of lymphocytes in cervical carcinomas implies a key role of a cellular anti-tumor response [6]. In fact, T-cell-mediated activity plays an important role in both anti-tumor and anti-viral immunity. In particular, the optimal T lymphocyte response is mediated by the balance between CD28 and CTLA-4 molecules. CD28 is constitutively expressed in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets, and functions as the main costimulator of T cells. Its structural homologue CTLA-4 is transiently induced upon activation, and is responsible for termination of an ongoing immune response. Any dysregulation of expression of CD28 and CTLA-4 molecules might result in impaired T cell functions.

The interaction of immunological genes for CD28, CTLA-4, and IFN-gamma in susceptibility to cervical cancer has been recently demonstrated [7]. In particular, the two-locus combination of IFNG + 874(AA) genotype with CD28 + 17(TT) or CTLA-4-319(CC) affecting protein expression was recently found to be associated with cervical cancer susceptibility [7, 8]. Those findings strongly suggest a relation between CD28, CTLA-4, and IFN-gamma, and their importance in cervical carcinoma development [7, 9]. Therefore, we assessed the pattern of expression of both CD28 and CTLA-4 molecules in freshly isolated and ex vivo stimulated peripheral blood (PB) T cells from patients with advanced cervical cancer. We also examined the ability of PBMCs to secrete IFN-gamma under non-stimulation and stimulation conditions. All results were compared to those obtained from healthy individuals.

Our study shows for the first time that patients with advanced stages of cervical cancer could be immunosuppressed due to a dysregulated pattern of costimulatory CD28 and inhibitory CTLA-4 molecules expression in PB T cells.

Materials and Methods

Patients

The study was performed on a group of 22 women with clinically definite CC in stages as follows: III (17 patients) and IV (5 patients). Stage of the disease was classified according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO). Median age of patients was 54 (range 38–74). Patients were treated at the Department of Oncology and Gynecological Oncology in Wroclaw Medical University. All cases of cervical cancer were histologically defined as cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC).

Blood samples were taken from patients before therapy. Standard treatment of cervical cancer stage III-IVA was radiation combined with concurrent chemotherapy. In particular, all patients were treated by external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) according to conformal planning. The target volume covered the tumor with a sufficient margin of vagina and regional lymph nodes. The dose of EBRT was approximately 50.4 Gy in conventional fractionation of 1.8 Gy daily. Conformal boosts of an additional 10–15 Gy were applied (limited volumes of gross unresected adenopathy). We used conformal treatment with 18 MeV photon beams generated from a Varian linear accelerator. For the majority of patients receiving EBRT, concurrent cisplatin-based chemotherapy, every-7-days regimen, 40 mg/m2 was also administered.

Most patients also received brachytherapy performed using intracavitary applicators depending on the patient and tumor anatomy. The treatment was initiated toward the latter part of external beam radiotherapy, after sufficient regression of the tumor. We used HDR microSelectron (Nucletron). The dose of brachytherapy was usually 30 Gy/3 fr. Cervical cancer patients in stage IV B received palliative radiotherapy, chemotherapy or symptom treatment.

The control group consisted of 17 healthy age-matched women with the median age 48 (range 28–70). Informed consent was obtained from each individual. The study was approved by the local ethics committee.

Cell Isolation and Culture Conditions

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were separated by buoyant density-gradient centrifugation on Lymphoflot (Biotest, Germany) from freshly drawn peripheral venous blood and washed 3 times in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (without Ca2+ and Mg2+). Cells were suspended at 1 × 106 PBMCs/ml in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, Paisley, UK) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Flow Laboratories, UK), 2 mmol/l L-glutamine and 50 μg/ml gentamicin (Gibco), and cultured with 5 ng/ml of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) (Ortho, Neckargemund, Germany) and 500 U/ml of rIL-2 (Eurocetus, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). In our model, rIL-2 served as a second signal to induce an optimal immune response. Control cultures without stimulants were included in each experiment. The cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 for 24, 48, and 72 h. Culture supernatants were stored at −80°C until the time of testing.

CD28 and CTLA-4 Staining and Flow Cytometric Analysis

CD28 and CTLA-4 expression was studied on the freshly isolated and cultured CD3 + CD4+ and CD3 + CD8+ cells by a triple immunostaining method. Briefly, for detection of CD28 and membrane CTLA-4 molecules, the cells were washed twice in PBS, divided into tubes at a concentration of 5 × 105 cells per tube, stained with anti-CD3/PerCP, anti-CD4/FITC or anti-CD8/FITC, and anti-CD28/RPE or anti-CTLA-4 (CD152)/RPE monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs) (Becton Dickinson), and incubated for 30 min at 4°C in the dark. Excess unbound antibodies were removed by two washes with PBS. Following these washes, the cells were resuspended in PBS and analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson). For intracellular detection of CTLA-4, the cells were first incubated for 30 min at 4°C in the dark with pure anti-CTLA-4 MoAb to block surface CTLA-4 molecules, then fixed and permeabilized according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, and then stained as described above. Negative controls were always done by omitting the MoAb and by incubating the cells with mouse Ig of the same isotype as the MoAbs conjugated with PerCP, FITC or RPE. At least 10,000 events per sample were analyzed. All PBMCs were included in the forward scatter/side scatter (FwSc/SSc) gate. Of the acquired 10,000 events, at least 1,500-2,000 were analyzed in the final CD28- or CTLA-4-staining histograms. The results were expressed as the proportion of CD28-positive CD3 + CD4+ or CD3 + CD8+ cells and CTLA-4-positive CD3+ lymphocytes. The CellQuest program was used for statistical analysis of the acquired data.

Assessment of IFN-γ Concentration

For IFN-gamma measurement, we cultured PBMCs for 72 h in medium alone or with the addition of anti-CD3 + rIL-2 in concentrations described above. Supernatant samples collected from studied groups were frozen (−70°C) until analyzed. IFN-γ concentration in non-stimulating and stimulating culture supernatants was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using R&D Systems reagent kit (UK) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Each sample was run in duplicate. The values were expressed as picograms per milliliter relative to a set of standards supplied with the kit.

Statistical Analysis

Before further analysis, data were checked for normal distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test. As the data showed non-parametric distribution, Mann–Whitney U test for comparison of the unpaired data was used. The summary statistics are given as the mean ± SD. The level of statistical significance was set as p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Expression of Costimulatory CD28 Molecule on Freshly Drawn and anti-CD3 + rIL-2-Stimulated CD4+ and CD8+ T Lymphocytes from Cervical Cancer Patients and Healthy Controls

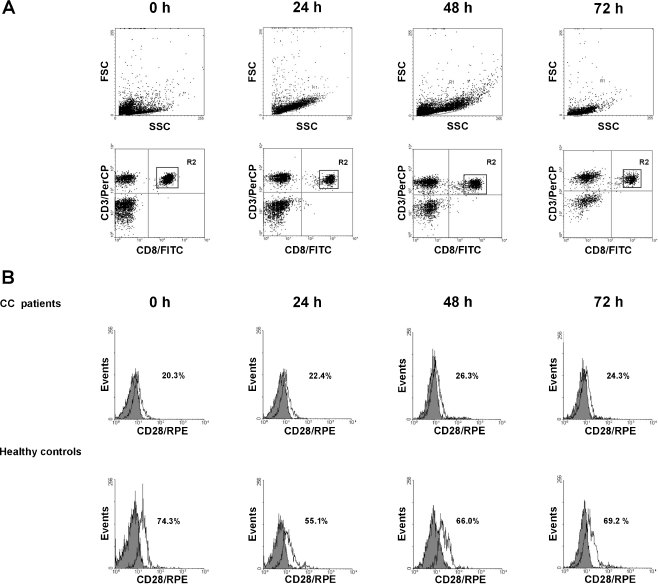

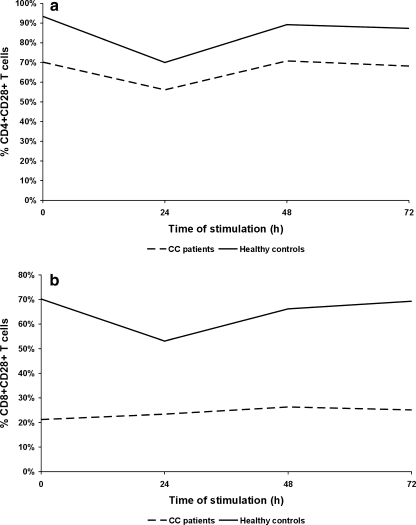

To examine the magnitude of functional T helper (Th) and T cytotoxic (Tc) lymphocytes in PB of patients and controls, we estimated the expression of CD28 molecule within both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations in the studied groups. The results are shown in Table 1 and Figs. 1 and 2. We found that the mean proportion of PB CD4 + CD28+ T cells was significantly lower in cervical cancer (CC) patients than in controls. The decrease in CD28-positive cells within the CD8+ T cell subset was even more pronounced. Similarly to healthy individuals, after 24 h of ex vivo stimulation, we observed in patients a marked decrease in the mean frequency of CD4 + CD28+ T cells, which returned to pre-stimulation values after 48 h, and remained unchanged after 72 h of culture (Fig. 2a). The only difference between CC patients and controls was markedly diminished proportions of CD4 + CD28+ T cells in CC women at each time point tested. In contrast, the frequencies of CD8 + CD28+ T cells in the patient group did not change during ex vivo stimulation, and maintained stable values, which were significantly lower at different time points of culture compared to controls (Figs. 1 and 2b).

Table 1.

Mean percentages and standard error of peripheral blood lymphocytes expressing CD28 and CTLA-4 in CC patients and healthy controls

| freshly drawn cells% | 24 h stimulated% | 48 h stimulated% | 72 h stimulated% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CC patients (n = 22) | ||||

| CD3 + CD4 + CD28+ | 70.2 ± 19.1**,a | 56.1 ± 15.2*,a,b | 70.8 ± 14.6*,b | 68.2 ± 15.2* |

| CD3 + CD8 + CD28+ | 21.2 ± 13.3†† | 23.4 ± 9.8† | 26.3 ± 9.1† | 25.1 ± 12.9†† |

| CD3 + sCTLA-4+ | 15.2 ± 3.2‡‡,a | 25.1 ± 4.1‡‡,a | 24.0 ± 3.9‡‡,c | 17.6 ± 2.7‡,c |

| CD3 + cCTLA-4+ | 11.2 ± 1.9#,a | 32.3 ± 6.4##,a,b | 44.1 ± 5.1##,b | 47.2 ± 4.7## |

| Healthy controls (n = 17) | ||||

| CD3 + CD4 + CD28+ | 93.4 ± 8.2**,a | 70.0 ± 7.9*,a,b | 89.2 ± 6.8*,b | 87.3 ± 8.1* |

| CD3 + CD8 + CD28+ | 70.2 ± 6.9††,a | 53.1 ± 4.5†,a,b | 66.2 ± 6.1†,b | 69.3 ± 5.4†† |

| CD3 + sCTLA-4+ | 1.9 ± 0.5‡‡,a | 3.5 ± 0.9‡‡,a,b | 4.8 ± 1.1‡‡,b,c | 7.9 ± 1.9‡,c |

| CD3 + cCTLA-4+ | 1.4 ± 0.2#,a | 2.9 ± 0.8##,a | 3.5 ± 1.1##,c | 6.2 ± 1.5##,c |

*Comparison between CC patients and healthy controls. One symbol indicates p < 0.05; two symbols p < 0.04.

†Comparison between CC patients and healthy controls. One symbol indicates p < 0.01; two symbols p < 0.001.

‡Comparison between CC patients and healthy controls. One symbol indicates p < 0.01; two symbols p < 0.00001.

#Comparison between CC patients and healthy controls. One symbol indicates p < 0.0001; two symbols p < 0.00001.

aComparison between freshly drawn cells and 24 h stimulated cells; p < 0.04.

bComparison between 24 h stimulated cells and 48 h stimulated cells; p < 0.05.

cComparison between 48 h stimulated cells and 72 h stimulated cells; p < 0.02.

sCTLA-4 – surface CTLA-4; cCTLA-4 – cytoplasmic CTLA-4

Fig. 1.

CD28 expression in peripheral blood CD8+ T cells from patients with CC and from healthy controls before and after 24 h, 48 h and 72 h stimulation with anti-CD3 MoAb + rIL-2. The dot plots and histograms show representative data, illustrating the analysis method for identification of CD3+/CD8+ cells expressing CD28 following three-color staining. (a) The dot plots show the forward scatter/side scatter (FSC/SSC) distribution and the gate (region R1) was used to select lymphocytes for analysis. The R1 gated events were then analyzed for CD3/PerCP and CD8/FITC staining and double-positive cells (CD3 + CD8+) were gated (region R2). The dot plots show representative data from one patient with CC. (b) The final histograms. The double-gated populations were then analyzed for CD28/RPE. The gray histograms represent the isotype controls. The numbers located on the histograms represent the percentage of CD3 + CD8+ cells expressing CD28 molecule

Fig. 2.

The mean percentage of peripheral blood CD4 + CD28+ T cells (a) and CD8 + CD28+ T cells (b) before and after ex vivo 24, 48 and 72 h of anti-CD3 + rIL-2 stimulation in CC patients and healthy controls

The analysis of the pattern of CD28 expression on CD4+ and CD8+ PB T cells indicates that patients with advanced CC may exhibit a profound defect of the CD28-mediated costimulatory pathway. Thus, abnormal CD28 expression on effector T cells may contribute to inadequate activation and dysfunction of PB lymphocytes in CC.

Expression of Inhibitory CTLA-4 (CD152) Molecule on Freshly Drawn and anti-CD3 + rIL-2-Stimulated T Lymphocytes from Cervical Cancer Patients and Healthy Controls

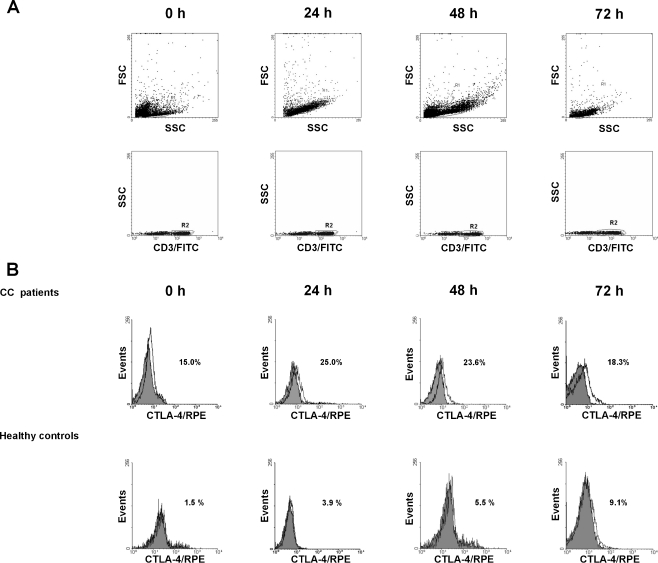

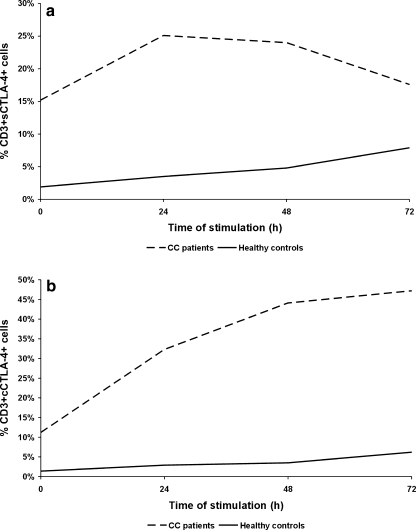

Since homeostasis in the immune responses results from a balanced interplay between CD28 and CTLA-4, we analyzed whether the observed dysregulated CD28 expression might have an impact on the pattern of CTLA-4 expression in PB T cells from CC patients. The results are shown in Table 1 and Figs. 3 and 4. In patients, we found markedly heightened mean proportions of both CD4+ and CD8+ PB T cells with surface expression of CTLA-4 molecule compared to controls. Furthermore, there were no statistically significant differences between the magnitude of CD4 + CTLA-4+ and CD8 + CTLA-4+ T cells in all patients at each time point tested (data not shown), suggesting similar kinetics and levels of CTLA-4 expression in all T lymphocytes without distinction between both subpopulations. Thus, we decided to continue the analysis of its expression on CD3 + −gated lymphocytes, in addition, with regard to CTLA-4 cellular distribution. Ex vivo stimulation led to a further increase in the frequency of T cells co-expressing CTLA-4 with the maximum value after 24 h of culture. On subsequent days of the stimulating culture, we observed a gradual decline in the proportions of CTLA-4+ T cells. However, the levels of their expression remained significantly higher than those observed in controls at each time point tested (Figs. 3 and 4a). In healthy individuals, the mean frequencies of CTLA-4+ T cells (Table 1, Figs. 3 and 4a) gradually increased under stimulation conditions, and reached a maximum level after 72 h, which was in sharp contrast to CC patients.

Fig. 3.

Surface CTLA-4 expression in peripheral blood CD3+ cells from patients with CC and from healthy controls before and after 24 h, 48 h and 72 h stimulation with anti-CD3 MoAb + rIL-2. The dot plots and histograms show representative data, illustrating the analysis method for identification of CD3+ cells expressing CTLA-4 molecule following double-color staining. (a) The dot plots show the forward scatter/side scatter (FSC/SSC) distribution and the gate (region R1) was used to select lymphocytes for analysis. The R1 gated events were then analyzed for CD3/FITC staining and CD3-positive cells were gated (region R2). The dot plots show representative data from one patient with CC. (b) The final histograms. The double-gated populations were then analyzed for CTLA-4 expression. The gray histograms represent the isotype controls. The numbers located on the histograms represent the percentage of CD3+ cells expressing surface CTLA-4

Fig. 4.

The mean percentage of peripheral blood T cells expressing surface CTLA-4 (CD3 + sCTLA-4+ cells) (a) and cytoplasmic CTLA-4 (CD3 + cCTLA-4+ cells) (b) before and after ex vivo 24, 48 and 72 h of anti-CD3 + rIL-2 stimulation in CC patients and healthy controls

From these results it seems that in advanced CC, impaired CD28 expression is accompanied by an abnormal pattern of inhibitory CTLA-4 molecule expression, which may contribute to earlier and stronger induction of the CTLA-4-mediated down-regulatory pathway in PB T cell responses upon antigen stimulation.

Expression of Inhibitory CTLA-4 (CD152) Molecule in Cytoplasmic Compartment of Freshly Drawn and anti-CD3 + rIL-2-Stimulated T Lymphocytes from Cervical Cancer Patients and Healthy Controls

To find out whether the dysregulated surface CTLA-4 expression in CC patients might result from enhanced recycling of the CTLA-4 molecule to the cell membrane, we performed intracellular staining for cytoplasmic CTLA-4 in both freshly drawn and ex vivo stimulated T cells. The results are shown in Table 1 and Fig. 4b. Likewise, we observed markedly up-regulated proportions of PB T lymphocytes with intracellular CTLA-4 content in CC patients compared to controls. In the culture with stimulants, we found significantly heightened CTLA-4 expression at each time point tested as it was shown in the case of surface CTLA-4 (Fig. 4b). Of note, the kinetics of cytoplasmic CTLA-4 expression in CC patients were seen to be different from those of surface expression, with highest levels of the former at 72 h.

These results allow us to exclude disturbed intracellular trafficking of CTLA-4 as a cause of up-regulated surface CTLA-4 expression in CC patients.

Measurement of IFN-Gamma Concentrations in Supernatants from the Culture of PBMCs in Medium Alone and with Addition of anti-CD3 + rIL-2

As IFN-gamma was suggested to be associated with CD28 and CTLA-4 molecules in development of CC, we estimated IFN-gamma levels in supernatants from the culture of PBMCs in both studied groups. Although we observed increased capacity for spontaneous production of IFN-gamma in the culture in medium alone in CC patients compared to healthy individuals (179.1 ± 144.6 pg/ml vs. 151.7 ± 213.2 pg/ml), the differences between studied groups were not statistically significant. In contrast, significantly increased IFN-gamma concentrations secreted by stimulated cells from patients with advanced CC compared to controls were found (1906.5 ± 1548.2 pg/ml vs. 616.4 ± 363.0 pg/ml; p = 0.04).

Discussion

Our study shows that advanced cervical cancer patients have a variety of defects reflecting impaired T cell immunoregulatory circuits. Herein, we report for the first time significant dysregulation in the percentages of PB T cells expressing suppressor CTLA-4 and costimulatory CD28 molecules before and after ex vivo stimulation. Abnormal expression of both CTLA-4 and CD28 in peripheral nonmalignant T lymphocytes has been demonstrated in some malignancies [10–13]. The literature lacks reports on the pattern of expression of these molecules in advanced cervical cancer patients. We found a marked increase in the frequency of CTLA-4+ T cells freshly isolated from PB of patients as compared with healthy individuals. We also observed markedly diminished proportions of CD28-positive cells within both T cell subpopulations, more pronounced in the CD8+ subset.

Since CTLA-4 expression is transiently induced upon stimulation, it is considered to be an activation marker. Thus, its higher expression reflects systemic activation status in the periphery during progression of cervical cancer. Our additional finding of markedly decreased proportions of PB CD4+ and CD8+ T cells with CD28 expression in patients strengthens the suggestion that these lymphocytes are in a partial state of in vivo activation. This statement results from the observation that the CD28 molecule is lost by T cells after repeated stimulation in long-term culture [14]. Elevated concentrations of chemical indicators of systemic immune activation, such as neopterin, have also been reported in patients with gynecological carcinomas, including cervical cancer, but not in women with benign neoplasms or precancerous disorders [15].

Increased surface expression of CTLA-4 in T cells does not seem to result from cellular trafficking, since it is accompanied by a CTLA-4 increase in the cytoplasmic compartment, suggesting rather the up-regulated CTLA-4 gene activity during in vivo continuous stimulation with cancer- and/or viral-associated antigens. We also hypothesize that heightened levels of CTLA-4 in T cells may result, at least in part, from genetic disturbances. The relation of its increased expression with higher frequency of the T allele at position −319 in the CTLA-4 promoter region has been previously demonstrated [16]. A recent study by our group showed significantly higher frequencies of both the T allele and the CT + TT genotype in Polish cervical cancer women compared with healthy controls [17]. We also demonstrated that this genotype increased the risk of disease approximately twofold [17]. The same observation was found by Su et al. [18] in Taiwanese women suffering from cervical cancer, especially in those who were HPV-positive.

Since the loss of CD28 expression was found to be accelerated by type I IFN released during viral infections [19], we cannot exclude the influence of HPV infection on the decreased expression of CD28, at least in the group of cervical cancer patients studied. It has also been suggested that one of the mechanisms leading to diminished CD28 expression may be secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines by tumors. The impact of TNF-alpha on the repression of the transcriptional activity of the CD28 gene promoter has been previously demonstrated [20]. The connection of impaired CD28 expression on PB T cells with TNF-alpha concentration seems to be possible in the light of findings that serum levels of this cytokine produced by neoplastic cells were markedly increased in cervical cancer patients and correlated with the stage of the disease [21–24].

We also observed in patients dysregulated kinetics of both CD28 and surface CTLA-4 expression after ex vivo stimulation. In contrast to healthy individuals, who exhibit maximum surface CTLA-4 expression at 72 h of stimulation, in patients with cervical carcinoma the peak of its expression was observed at 24 h, with a gradual decline to pre-stimulation values at 96 h. Heightened proportions of surface CTLA-4 positive T cells in cervical cancer might be of biological relevance consistent with the notion that only surface CTLA-4-mediated signals are capable of inhibiting the ongoing T cell responses. In the case of CD28, under normal stimulation conditions, its expression rapidly down-regulated within the first 24 h, and returned to baseline levels at 48 h of culture [12, 25]. In the CD8+ T cell population from cervical cancer patients, CD28 expression remained at a stable decreased level at each time point tested. However, the kinetic pattern of CD28 expression within CD4+ T cells was similar to that observed in controls, except for significantly lower mean frequency of CD4 + CD28+ T cells in the stimulation period. Based on the fact of reciprocal regulation of CD28 and CTLA-4 expression on both mRNA and protein levels during the first 24 h of stimulation [25], it can be suggested that the loss of CD28 expression may deliver a much stronger stimulus for CTLA-4 gene induction resulting in heightened levels of protein expression on T cells in advanced cervical carcinoma.

Dysregulated expression of costimulatory CD28 and inhibitory CTLA-4 molecules within PB T cells strongly suggests their possible impact on the biology of the effector T cell responses in cervical cancer leading to abnormalities in systemic cellular immunity during disease progression. The demonstration of a direct correlation between immunological competence of the host and clinical outcome for patients harboring cervical cancer has been previously reported [26]. It has been demonstrated that up-regulated CTLA-4 expression on circulating effector cytotoxic CD8+ T cells reflects the state of T cell exhaustion due to persistent antigenic stimulation [27, 28]. Furthermore, blockade of CTLA-4 can reverse CD8+ T cell dysfunction in a CD28-dependent manner. This functional effect is mediated by CD8 + CD28+ T cells, and independently from CD4 + FoxP3 + CTLA-4+ regulatory T cells (Treg) [28]. Thus, detection of CD28 expression within the CD8+ T cell subset provides a marker for reversible functional exhaustion of these cells. Our observation that the loss of CD28 expression is more pronounced in the CD8+ T cell population strongly suggests affected cytotoxic effector function in progressive cervical cancer, influencing the defense against virus-induced tumors [29] and clinical response to chemotherapy [30].

The generation of a specific cytotoxic T cell response is known to depend on sufficient help from activated CD4+ T cells. It has been shown that failure of the anti-tumor response can result from inadequate activation of tumor-specific CD4+ T helper cells [31]. In the light of those findings, the effective anti-tumor and anti-viral action of cytotoxic CD8 + CD28+ T cells in cervical cancer patients enrolled in our study might be complicated by dysregulated expression of both CD28 and CTLA-4 within the CD4+ T helper cell population, which may lead to its dysfunction [32, 33].

Recent evidence indicates, however, that both CD28 and CTLA-4 are also important in the homeostasis and function of the suppressive T cell populations, termed regulatory and/or suppressor T cells [34–36], as continuous antigen stimulation leads to generation of highly suppressive adaptive CD4 + FoxP3+ as well as CD8 + FoxP3+ regulatory T cells (Treg) [37]. Increased levels of CTLA-4 molecules may promote generation and function of adaptive CD4 + FoxP3+ T cells in addition to their other inhibitory effects [38]. However, their role in the induction of CD8 + FoxP3+ T cells is still controversial. CTLA-4 was found to be constitutively expressed on the cell surface as well as in the cytoplasmic compartment of Treg cells [39]. Up-regulated CTLA-4 expression within both T cell subsets found in our study seems to strengthen immunosuppressive action of Treg cells in advanced cervical cancer. This suggestion is in accordance with the observation on the increased frequency and suppressive activity of Treg cells in PB from women with cervical cancer [40].

Recent studies revealed that CD8+ T cells exhibit a cytotoxic activity in conjunction with positive expression of CD28, but show a suppressive action in the presence of negative labeling [41]. Our report shows that advanced cervical cancer patients exhibit a significantly increased population of PB immunosuppressive T cells with the phenotype CD8 + CD28-, and this observation is in accordance with studies performed in other cancer patients [36]. These suppressor T cells originate and function in the presence of IL-10 [42], found at high concentrations in sera from patients with advanced stages of cervical cancer [43, 44]. CD8 + CD28- T cells suppress proliferation of the effector T cells and the functional activity of cytotoxic T lymphocytes, thus diminishing the defense against tumors [41, 45].

In our study we also demonstrated increased levels of stimulated IFN-gamma in supernatants from patients with advanced cervical cancer and it was, in fact, an unexpected notion. This phenomenon is difficult to explain in the light of contradictory results. IFN-gamma-producing Th1 cells were shown to promote the development of cell-mediated immunity against viral infection as well as HPV-associated neoplasms [46]. Therefore, the ability of reactive cells to secrete intratumorally the immunostimulatory and anti-viral cytokine IFN-gamma has been reported to be an independent factor for disease-free survival in cervical cancer [47]. Preferential recruitment and accumulation of Th1 cytokine-secreting cells to the invasive cervical cancer lesions in early stage cervical cancer patients suggested that these cells could play an important role in local anticancer immunity [48]. Several papers have indicated a beneficial effect of a high Th1/Th2 ratio in the case of various other cancers as well [49–53]. The up-regulated ability of stimulated PBMCs to secrete IFN-gamma found in patients from our study may likely suggest that the population of PB T cells in cervical cancer patients is in activated form due to exposure to viral and/or tumor antigens. However, a few papers have demonstrated a role of Th1 shift in the tumor promotion and immunosuppression [54–57]. It has been reported that increased production of IFN-gamma in tumor-associated inflammatory cells may contribute to tumor growth and disease progression [56]. In lung cancer, the presence of tumor cells or tumor-derived factors in peripheral blood following tumor burden favors the differentiation of PB T cells towards tumor-specific Th1- and Tc1-producing IFN-gamma cells, and seems to be a negative prognostic factor [57]. In this context, we cannot exclude that increased IFN-gamma production seen in studied patients with advanced disease could also reflect the tendency to neoplastic dissemination. Further experiments are required to settle the above contradiction.

In summary, our report provides the first evidence that patients with advanced cervical cancer exhibit dysregulated expression of molecules playing a key role in the balanced cellular immune responses. These abnormalities likely have a considerable impact on the development of systemic immunosuppression involved in cervical cancer progression.

Acknowledgments

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Abbreviations

- PB

Peripheral blood

- CC

Cervical cancer

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4

- IFN

Interferon

- FIGO

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

- PBMC

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- HPV

Human papillomavirus

- CIN

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- CSCC

Cervical squamous cell carcinoma

- EBRT

External beam radiotherapy

- PBS

Phosphate-buffered saline

- IL-2

Interleukin-2

- ELISA

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- Th

Helper T cell

- Tc

Cytotoxic T cell

References

- 1.Cheng WF, Lee CN, Su YN, Chang MC, et al. Induction of human papillomavirus type 16-specific immunologic responses in a normal and an human papillomavirus-infected populations. Immunology. 2005;115:136–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rellihan MA, Dooley DP, Burke TW, et al. Rapidly progressing cervical cancer in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Gynecol Oncol. 1990;36:435–438. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90159-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed SM, Al-Doujaily H, Reid WMN, et al. The cellular response associated with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in HIV + and HIV- subjects. Scand J Immunol. 2002;56:204–211. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2002.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santegoets LA, van Setyrs M, Heijmans-Antonissen C, et al. Reduced local immunity in HIV-related VIN: expression of chemokines and involvement of immunocompetent cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:616–622. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nasiell K, Roger V, Nasiell M. Behaviour of mild cervical dysplasia during long term follow-up. Obstet Gynecol. 1986;67:665–669. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198605000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilders C, Houbiers J, van Ravenswaay CH, et al. Association between HLA-expression and infiltration of immune cells in cervical carcinoma. Lab Invest. 1993;69:651–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivanson EL, Juko-Pecirep I, Gyllensten UB. Interaction of immunological genes on chromosome 2q33 and IFNG in susceptibility to cervical cancer. Gynec Oncol. 2010;116:544–548. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2009.10.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pravica V, Perrey C, Stevens A, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the first intron of the human IFN-gamma gene: absolute correlation with a polymorphic CA microsatellite marker of high IFN-gamma production. Hum Immunol. 2000;61:863–866. doi: 10.1016/S0198-8859(00)00167-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzman VB, Yambartsev A, Goncalves-Primo A, et al. New approach reveals CD28 and IFNG gene interaction in the susceptibility to cervical cancer. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1838–1844. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim CW, Choi SH, Chung EJ, Lee MJ, et al. Alteration of signal transducing molecules and phenotypical characteristics in peripheral blood lymphocytes from gastric carcinoma patients. Pathobiology. 1999;67:123–128. doi: 10.1159/000028061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melichar B, Nash MA, Lenzi R, et al. Expression of costimulatory molecules CD80 and CD86 and their receptors CD28, CTLA-4 on malignant ascites CD3+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) from patients with ovarian and other types of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Clin Exp Immunol 119:19–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Frydecka I, Kosmaczewska A, Bocko D, et al. Alterations of the expression of T-cell related costimulatory CD28 and down regulatory CD152 (CTLA-4) molecules n patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2042–2048. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Motta M, Rassenti L, Shelvin BJ, et al. Increased expression of CD152 (CTLA-4) by normal T lymphocytes in untreated patients with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:1788–1793. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Labalette M, Leteurtre E, Thumerelle C, et al. Peripheral human CD8 + CD28+ T lymphocytes give rise to CD28- progeny, but IL-4 prevents loss of CD28 expression. Int Immunol. 1999;11:1327–1335. doi: 10.1093/intimm/11.8.1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melichar B, Solichova D, Freedman RS. Neopterin as an indicator of immune activation and prognosis in patients with gynecological malignancies. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2006;16:240–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2006.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ligers A, Teleshova N, Masterman T, et al. CTLA-4 gene expression is influenced by promoter and exon 1 polymorphisms. Genes Immun. 2001;2:145–152. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6363752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pawlak E, Karabon L, Wlodarska-Polinska I, et al. Influence of CTLA-4/CD28/ICOS gene polymorphisms on the susceptibility to cervical squamous cell carcinoma and stage of differentiation in the Polish population. Hum Immunol. 2010;71:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Su TH, Chang TY, Lee YJ, Chen CK, et al. CTLA-4 gene and susceptibility to human papillomavirus-16-associated cervical cell carcinoma in Taiwanese women. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1237–1240. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bortwick NJ, Lowdell M, Salmon M, Akbar AN. Loss of CD28 expression on CD8+ T cells is induced by IL-2 receptor gamma chain signaling cytokines and type I IFN, and increases susceptibility to activation-inducted apoptosis. Int Immunol. 2000;12:1005–1013. doi: 10.1093/intimm/12.7.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bryl E, Vallejo AN, Weyand CM, Goronzy JJ. Down-regulation of CD28 expression by TNF-alpha. J Immunol. 2001;167:3231–3238. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.6.3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chopra V, Dinh TV, Hanningan EV. Circulating serum levels of cytokines and angiogenic factors in patients with cervical cancer. Cancer Invest. 1998;16:152–159. doi: 10.3109/07357909809050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaiotti D, Chung J, Iglesias M, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha promotes human papillomavirus (HPV) E6/E7 RNA expression and cyclin-dependent kinase activity in HPV-immortalized keratinocytes by a ras-dependent pathway. Mol Carcinog. 2000;27:97–109. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2744(200002)27:2<97::AID-MC5>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Azar KK, Tani M, Yasuda H, et al. Increased secretion patterns of interleukin-10 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in cervical squamous intraepithelial lesions. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:1376–1384. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zijlmans HJ, Fleuren GJ, Baelde HJ, et al. Role of tumor-derived proinflammatory cytokines GM-CSF, TNF-alpha, and IL-12 in the migration and differentiation of antigen-presenting cells in cervical carcinoma. Cancer. 2007;109:556–565. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linsley P, Bradshaw J, Urnes M, et al. CD28 engagement by B7/BB1 induces transient down-regulation of CD28 synthesis and prolonged unresponsiveness to CD28 signalling. J Immunol. 1993;150:3161–3169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins GD, Davy M, Roder D, et al. Increased age and mortality associated with cervical carcinomas negative for human papillomavirus RNA. Lancet. 1991;338:910–913. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91773-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ha SJ, West EE, Araki K, et al. Manipulating both the inhibitory and stimulatory immune system towards the success of therapeutic vaccination against chronic viral infections. Immunol Rev. 2008;223:317–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamoto N, Cho H, Shaked A, et al. Synergistic reversal of intrahepatic HCV-specific CD8 T cell exhaustion by combined PD-1/CTLA-4 blockade. PLoS Pathogens. 2009;5:e1000313. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brittenden J, Heys SD, Ross J, Eremin O. Natural killer cells and cancer. Cancer. 1996;77:1226–1243. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960401)77:7<1226::AID-CNCR2>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cosiski-Marana HR, Santana da Silva J, Moreira de Andrade J. NK cell activity in the presence of IL-12 is a prognostic assay to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:318–323. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kern DE, Klarnet JP, Jensen MCV, Greenberg PD. Requirement for recognition of class II and processed tumor antigen for optimal generation of syngeneic tumor-specific class I-restricted CTL. J Immunol. 1986;136:4303–4310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kosmaczewska A, Frydecka I, Bocko D, et al. Correlation of blood lymphocyte CTLA-4 (CD152) induction in Hodgkin’s disease with proliferative activity, interleukin 2 and interferon gamma production. Br J Haematol. 2002;118:202–209. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carreno BM, Bennett F, Chau TA, et al. CTLA-4 (CD152) can inhibit T cell activation by two different mechanisms depending on its level of cell surface expression. J Immunol. 2000;165:1352–1356. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scotto L, Naiyer AJ, Galluzzo S, et al. Overlap between molecular markers expressed by naturally occurring CD4 + CD25+ regulatory T cells and CD8 + CD28- T suppressor cells. Hum Immunol. 2004;65:1297–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sansom DM, Walker LS. The role of CD28 and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) in regulatory T-cell biology. Immunol Rev. 2006;212:131–148. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karagoz B, Bilgi O, Gumus M, et al. CD8 + CD28- cells and CD4 + CD25+ regulatory T cells in the peripheral blood of advanced stage lung cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2010;27:29–33. doi: 10.1007/s12032-008-9165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mahic M, Henjum K, Yaqub S, et al. Generation of highly suppressive adaptive CD8(+)CD25(+)FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells by continuous antigen stimulation. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:640–646. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng SG, Wang JH, Stohl W, et al. TGF-beta requires CTLA-4 early after T cell activation to induce FoxP3 and generate adaptive CD4 + CD25+ regulatory cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:3321–3329. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi T, Tagami T, Yamazaki S, et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25 + CD4+ regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Exp Med. 2000;192:303–309. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Visser J, Nijman HW, Hoogenboom B-N, et al. Frequencies and role of regulatory T cells in patients with (pre)malignant cervical neoplasia. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;150:199–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.June CH, Ledbetter JA, Linsley PS, Thompson CB. Role of CD28 receptor in T-cell activation. Immunol Today. 1990;11:211–216. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(90)90085-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Filaci G, Fravega M, Negrini S, et al. Nonantigen specific CD8+ T suppressor lymphocytes originate from CD8 + CD28- T cells and inhibit both T-cell proliferation and CTL function. Hum Immunol. 2004;65:142–156. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chopra V, Dinh TV, Hannigan EV. Circulating serum levels of cytokines and angiogenic factors in patients with cervical cancer. Cancer Invest. 1998;16:152–159. doi: 10.3109/07357909809050029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diaz-Benitez CE, Navarro-Fuentes KR, Flores-Sosa JA, et al. CD3zeta expression and T cell proliferation are inhibited by TGF-beta1 and IL-10 in cervical cancer patients. J Clin Immunol. 2009;29:32–544. doi: 10.1007/s10875-009-9279-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahic M, Yaqub S, Bryn T, et al. Differentiation of naïve CD4+ T cells into CD4 + CD25 + FOXP3+ regulatory T cells by continuous antigen stimulation. J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1111–1117. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0507329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clerici M, Merola M, Ferrario E, et al. Cytokine production patterns in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: association with human papillomavirus infection. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:245–250. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.3.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tartour E, Gey A, Sastre-Garau E, et al. Prognostic value of intratumoral interferon gamma messenger RNA expression in invasive cervical carcinomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:287–294. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.4.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santin AD, Ravaggi A, Bellone S, et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes contain higher numbers of type 1 cytokine expressors and DR + T cells compared with lymphocytes from tumor draining lymph nodes and peripheral blood in patients with cancer of the uterine cervix. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81:424–432. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kusuda T, Shigemasa K, Arihiro K, et al. Relative expression levels of Th1 and Th2 cytokine mRNA are independent prognostic factors in patients with ovarian cancer. Oncol Rep. 2005;13:1153–1158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ubukata H, Motohashi G, Tabuchi T, et al. Evaluations of interferon-gamma/interleukin-4 ratio and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio as prognostic indicators in gastric cancer patients. J Surg Oncol. 2010;102:742–747. doi: 10.1002/jso.21725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Teschendorff AE, Gomez S, Arenas A, et al. Improved prognostic classification of breast cancer defined by antagonistic activation patterns of immune response pathway modules. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:604. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tosolini M, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, et al. Clinical impact of different classes of infiltrating T cytotoxic and helper cells (Th1, Th2, Treg, and Th17) in patients with colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1263–1271. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.De Monte L, Reni M, Tassi E, et al. Intratumor T helper type 2 cell infiltrate correlates with cancer-associated fibroblast thymic stromal lymphopoietin production and reduced survival in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Med. 2011;208:469–478. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eylar EH, Lefranc C, Baez I, et al. Enhanced interferon-gamma by CD8 + CD28- lymphocytes from HIV + patients. J Clin Immunol. 2001;21:135–144. doi: 10.1023/A:1011055805869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang YM, Alexander SI. CD8 regulatory T cells: what’s old is now new? Immunol Cell Biol. 2009;87:192–193. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ito N, Suzuki Y, Taniguchi Y, et al. Prognostic significance of T helper 1 and 2 and T cytotoxic 1 and 2 cells in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:2027–2032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]