Abstract

Ycf1p function is regulated by casein kinase 2α, Cka1p, via phosphorylation of Ser251. Cka1p-mediated phosphorylation of Ycf1p is attenuated in response to high salt stress. Previous results from our lab suggest a role for Ycf1p in cellular resistance to salt stress. Here, we show that Ycf1p plays an important role in cellular resistance to salt stress by maintaining the cellular redox balance via glutathione recycling. Our results suggest that during acute salt stress increased Sod1p, Sod2p and Ctt1p activity is the main compensatory for the loss in Ycf1p function that results from reduced Ycf1p-dependent recycling of cellular GSH levels.

Keywords: Ycf1p, salt stress, super oxide dismutase, catalase, glutathione, glutathione peroxidase

1. Introduction

Transporters of the ATP-Binding Cassette (ABC) superfamily are expressed in all organisms from microbes to mammals, and function in the transport of a broad range of diverse chemical compounds across cellular membranes [1–2]. Recent interest has focused on the ABCC subfamily of ABC transporters, whose prototype member is the mammalian multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (MRP1) also called ABCC1. MRP1 has been shown to be important in the detoxification of a variety of cellular chemical insults [1–4]. The MRP1 homologue in yeast is yeast cadmium factor 1 (Ycf1p) [5–6]. Ycf1p was initially described as a protein involved in cellular resistance to cadmium [6]. Ycf1p sequesters glutathione conjugated cadmium into the vacuole in an ATP-dependent manner [5–6]. It has since been shown that Ycf1p can transport a broad range of cellular toxins into the vacuole as glutathione (GSH) conjugates (GS-X) [7]. Importantly, Ycf1p shares many of the same characteristics as MRP1 including the ability to transport free GSH and GSSG [8–9]. The shared ability of MRP1 and Ycf1p to transport free GSH has resulted in speculation that both MRP1 and Ycf1p play a role in cellular redox balance.

Ycf1p function is regulated by a number of Ycf1p-protein interactors [10–11]. Recently, our lab has shown that Ycf1p function is regulated by casein kinase 2α, Cka1p, via phosphorylation of Ser251 within the L0 domain of the Ycf1p N-terminal extension (NTE) [12]. Cka1p-mediated phosphorylation of Ycf1p is attenuated in response to high salt stress. Attenuation of Cka1p-mediated phosphorylation of Ycf1p results in increased Ycf1p function [12]. This result suggests a role for Ycf1p in cellular resistance to salt stress; however deletion of ycf1Δ does not render the cells more susceptible to salt stress and cell death. Salt stress has been shown to be associated with increased cellular oxidative stress due to altered ion homeostasis and increased glycerol synthesis [13–15]; therefore we have investigated the role of Ycf1p in cellular oxidative stress resistance with respect to GSH homeostasis and redox stress response. Here, show Ycf1p plays a role in cellular resistance to salt stress by helping maintain the cellular redox balance through glutathione recycling. Further, in the absence of Ycf1p, increased Sod1p, Sod2p and Ctt1p expression compensate for the decrease in cellular salt stress resistance which results from the loss of Ycf1p-dependent glutathione recycling. This result explains why deletion of Ycf1p does not increase cellular sensitivity to high concentrations of salt.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast Strains, Media and Growth Conditions

Yeast strains used in this study are CP59 (BY4741, Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ), CP60 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ ycf1::KanMX), CP242 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ SOD1:TAP), CP243 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ SOD2:TAP), CP244 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ CTT1:TAP), CP245 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ GPX1:TAP), CP246 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ GPX2:TAP), CP247 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ SOD1:TAP ycf1::KanMX), CP248 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ SOD2:TAP ycf1::KanMX), CP249 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ CTT1:TAP ycf1::KanMX), CP250 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ GPX1:TAP ycf1::KanMX) and CP251 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ GPX2:TAP ycf1::KanMX). TAP tag strains were purchased from Open Biosystems(Thermo) [12]. ycf1::KanMX/Tap tag strains were made via PCR amplification of the ycf1::KanMX cassette from CP60 and subsequent transformation and G418 selection of TAP tag strains. Double deletion strains of sod1Δ, sod2Δ, ctt1Δ, gpx1Δ, and gpx2Δ in combination with ycf1Δ were created by PCR-mediated, gene replacement of ycf1Δ with URA3 as previously described [10,12]. In Brief, the double knock-out strains CP257 (ycf1Δ::URA3 sod1Δ::KanMX), CP258 (ycf1Δ::URA3 sod2Δ::KanMX), CP259 (ycf1Δ::URA3 ctt1Δ::KanMX), CP260 (ycf1Δ::URA3 gpx1Δ::KanMX) and CP261 (ycf1Δ::URA3 gpx2Δ::KanMX) were created by standard homologous recombination as follows. The single deletions CP252 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ sod1Δ::KanMX), CP253 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ sod2Δ::KanMX), CP254 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ ctt1Δ::KanMX), CP255 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ gpx1Δ::KanMX) and CP256 (Mat a met3Δ leu2Δ ura3Δ his3Δ gpx2Δ::KanMX) in the BY4741 background were obtained from the MATa yeast genome deletion collection (Open Biosystems). We confirmed the replacement of each gene with the KanMX cassette by standard PCR using a forward primer within the KanMX cassette and a reverse primer within the 3′ region of each gene. A PCR product containing the URA3 coding sequence flanked by 60 bp of homology to the 5′ upstream and 3′ downstream coding sequence of YCF1 was gel-purified according to the manufacturer's directions (Omega Bio-Tek), transformed into CP252-256 and double disruptants were selected on SC-URA G418-containing plates. Standard rich yeast media (YPD) was prepared as previously described [16]. All assays described here were done in liquid YPD, with either the addition of 5mM H2O2 or 0.5M NaCl (Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Cultures were grown at 30 C unless otherwise noted.

2.2. Measurement of Oxidative Stress Markers in Cells Treated with H2O2 or NaCl

To determine the effect that deletion of ycf1Δ has on cellular oxidative stress status of normal cells and cells that are H2 O2 and NaCl stressed, WT (CP59) and ycf1Δ (CP60) cells were grown overnight to an OD600 of 0.8. Cells were immediately treated with vehicle alone, 5mM H2O2 or 0.5M NaCl for 2 h. Cell pellets were collected by slow speed centrifugation (1000 x g) for 5 min. Cell Pellets were washed 3× with 1 mL of cold H2O and subsequently cell pellets were resuspended in the appropriate buffer as directed by the manufacturer of each of the oxidative stress marker kits (either the TBARS assay, GSH/GSSG assay, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), superoxide dismutase (SOD) or catalase (CAT) kits (Cayman Chemical)) and lysed using standard bead beating (1 min beating followed by 1 min on ice, 10 times) [10,12,16]. Lysates were subsequently spun at 10,000 x g and the supernatant was placed in a new tube and frozen at −80 °C until appropriate assays for oxidative stress markers were performed.

2.3. 2,7-difluorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DFFDA) Assay

Oxidative stress in cells was measured as previously described [17]. In brief, production of reactive oxygen species was measured under three conditions: untreated, 5mM H2O2 and 0.5M NaCl treated yeast cells. Cells were incubated overnight to an OD600 of 0.8. After the addition of 15μM DFFDA and vehicle or 0.5M NaCl in YPD culture for 1 h, 2 × 108 cells were harvested. Cells were washed once with water and twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were then resuspended in 200 μL of cold PBS and lysed by bead beating at 4°C for 10 min. The supernatant was collected by centrifugation at 14,000 x g for 10 min. Fluorescence was measured in 96 well plates using an excitation wavelength of 490nm and an emission wavelength of 527nm with a Biotek Synergy 2 plate reader. The results were normalized to protein concentration using the Bradford Assay and reported as fraction of control, relative DCF fluorescence, where fraction of control was calculated as such; [Ave relative fluorescence/mg protein of sample]/[relative fluorescence/mg protein of WT], n=3 (example - [relative fluorescence/mg protein of WT]/[relative fluorescence/mg protein of WT]=1).

2.4. Carbonylation Assay

Total cellular protein carbonylation was measured as previously described [18]. In brief, total cellular protein carbonylation was measured in 0, 2.5 and 5 mM H2O2 and 0, 0.25, and 0.5M NaCl treated yeast cells. Cells were incubated overnight to an OD600 of 0.8. After the addition of vehicle, 2.5 and 5 mM H2O2 and 0.25 or 0.5M NaCl cells were cultured for 1 h, cells were harvested by slow speed centrifugation at 1000 x g. Cells were washed once with water and twice with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Cells were then resuspended in 200–500 μL of ice cold RIPA buffer and lysed by bead beating as previously described [7,12]. Total protein carbonylation was measured by slot blot [18].

2.5. Western Blot Analysis

Protein expression was measure in all TAP tag strain as previously described [7,10–11]. Briefly, cells were grown overnight to an OD600 of 0.8. Cells were immediately treated with vehicle alone, 5mM H2O2 or 0.5M NaCl, for 2 h. Cell pellets were collected by slow speak centrifugation (1000 x g) for 5 min. Cell pellets were resuspended in RIPA buffer and bead beat 10× for 1 min intervals and place on ice for 1 min in between. Lysates were spun at 500 x g for 10 min and supernatant was placed in a new tube. Protein concentration was determined by BCA assay (Pierce Scientific) and lysates were frozen at −20 °C until ready for use. 50–100 μg of total protein was run on an SDS-PAGE gel at 120 V for 1–2 h and transferred to a nitran membrane via semi-dry at 25 V and 160 mAmps for 50 min or by standard wet-transfer for 3 h at 120 V (transfer method was dependent upon size of protein). Membranes were then blocked and probed with appropriate antibodies. Bands were visualized by chemiluminescence (HyBlot, Danville Scientific).

2.6. Growth inhibition by NaCl and H2O2

Growth inhibition by NaCl and H2O2 was monitored by spot tests on plates essentially as described previously (9, 23). Briefly, cells were grown overnight to saturation in SC-dropout medium, subcultured at a 1:5000 dilution in the same medium, and grown overnight to an A600 of 1.0. The overnight culture was diluted to an A600 of 0.1, which in turn was diluted in 10-fold increments. Aliquots (4 μl) of each 10-fold dilution were spotted onto SC-dropout plates containing no drug (vehicle alone), 0.5 M,NaCl or 0.5 mM H2O2 and incubated for 2 days, respectively.

3. Results and Discussion

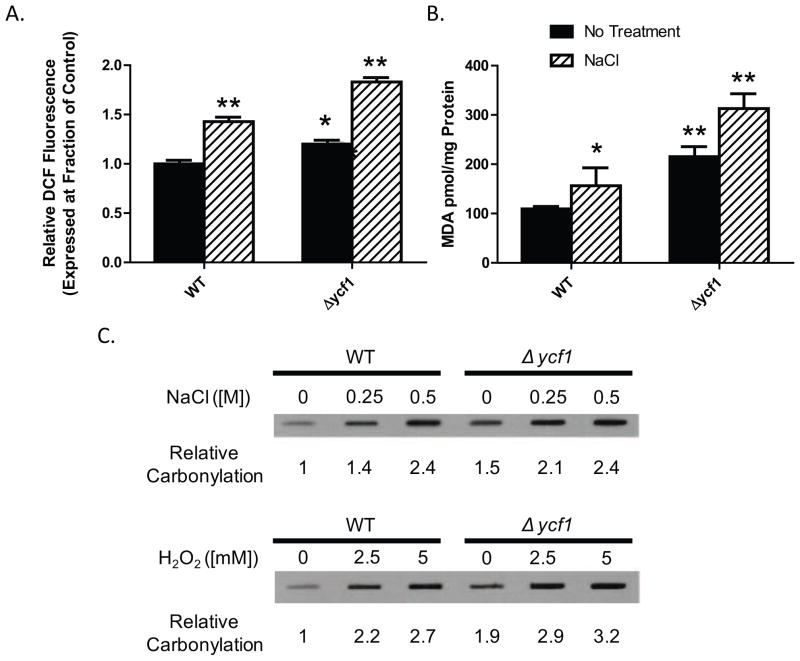

To better understand the role of Ycf1p in salt stress and salt-induced oxidative stress, we initially examined ROS formation in WT and ycf1Δ treated with vehicle alone or 0.5 M NaCl (Fig. 1A) by DCF fluorescence assay. Deletion of ycf1Δ increases cellular DCF fluorescence, indicating an increase in cellular ROS formation (Fig. 1A, compare columns 1 and 3). Upon addition of NaCl, DCF fluorescence is increased in both WT and the ycf1Δ strains as compared to their respective untreated controls (Fig. 1A, compare columns 2 and 4 to columns 1 and 3). Interestingly, treatment of the ycf1Δ strain with NaCl increases DCF fluorescence to about 1.5 fold beyond that of basal levels mirroring the 1.5 fold increase in relative DCF measured for the NaCl treated WT strain. This result suggests that the increase in DCF fluorescence in the treated ycf1Δ strain is an additive effect of what is seen in the untreated ycf1Δ and treated ycf1Δ cells. Our experiments presented in Fig. 1A suggest that Ycf1p plays a role in cellular protection against oxidative stress and that reduced expression or deletion of Ycf1p increases cellular susceptibility to oxidative stressors. To investigate this finding further, we measured two additional cellular markers of oxidative stress, malondialdehyde (MDA) formation and total protein carbonylation (using standard TBARS analysis and total carbonylation western blot) (Fig. 1B and 1C). Our analysis revealed that untreated ycf1Δ cells have increased MDA formation as compared to untreated control WT cellswhich is further exasperated by NaCl treatment (Fig. 1B). Similar to our DCF fluorescence analysis, the MDA assay revealed that Ycf1p plays a role in cellular protection against oxidative stress during basal growth conditions. Deletion of ycf1Δ results in increased MDA production as compared to WT cells. Additionally, treatment of ycf1Δ cells with NaCl increases MDA formation in ycf1Δ cells beyond basal level additively when compared to WT NaCl treated cells. NaCl-mediated protein carbonylation is increased with increasing salt concentration in ycf1Δ cells as compared to WT cells (Fig. 1C). To determine if the NaCl-mediated increase in total protein carbonylation in the ycf1Δ cells is specific to NaCl stress or more general, we examined protein carbonylation in WT and ycf1Δ H2O2 treated cells. Similar to our NaCl results, ycf1Δ cells are more sensitive to H2O2-mediated protein carbonylation. These experiments showed that in the ycf1Δ cells protein carbonylation becomes elevated more rapidly at lower salt and H2O2 concentration as compared to the WT control cells. The increase in total protein carbonylation in ycf1Δ cells is significantly increased in untreated cells and suggests that Ycf1p plays a role in regulating oxidative stress under basal growth conditions. The results from Fig. 1A and 1B suggest an underlying role for Ycf1p in general oxidative stress resistance through a combination of mechanisms; 1) a role in the regulation of GSH homeostasis and recycling, and 2) transport and sequestration of harmful toxins that increase cellular oxidative stress such as heavy metals (Cd+2 and As+3). Such a model is supported by our analysis of NaCl-mediated total protein carbonylation. In combination with our DCF assay analysis, our results strongly support a role for Ycf1p in protecting cells from oxidative stress under basal conditions in logarithmically growing cells and plays a smaller, yet important role in general cellular oxidative stress resistance via a combination of GSH transport into the vacuole and sequestration of metal-GSH complexes into the vacuole which results in decreased cytosolic GSH and reduce metal-induced oxidative stress.

Figure 1. Deletion of ycf1Δ increases intracellular NaCl-mediated ROS and oxidative stress.

A) ROS (panel A), MDA formation (panel B) and total protein carbonylation (panel C) was measured in WT and ycf1Δ cells after treatment with 0.5 M NaCl by DCF fluorescence as described in the Materials and Methods. Statistical analysis was carried-out in Prism Graphpad by One-Way and Two-Way ANOVA analysis with Bonferroni post tests (*=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, all statistics shown are with respect to untreated WT). All experiments were carried out with an n≥3. Blots shown here are representative of our findings which show that ycf1Δ has increased basal carbonylation as compared to WT which directly affects carbonylation in NaCl and H2O2 treated cells as dose increases.

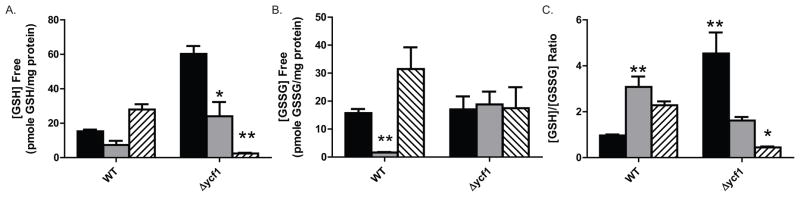

Ycf1p is a critical component of the GSH reducing and recycling system in yeast. The GSH recycling system plays a major role in reducing cellular oxidative stress via the continual renewal of reduced GSH [8,19–20]. We show that deletion of ycf1Δ results in a 4 fold increase in free GSH and a corresponding 4 fold increase in the [GSH]/[GSSG] ratio (Fig. 2A and 2C). The 4 fold increase in the [GSH]/[GSSG] ratio is due to an increase cytosolic GSH and not a decrease in GSSG as GSSG concentration is unchanged by the deletion of ycf1Δ (Fig. 2B). Treatment of WT and ycf1Δ cells with H2O2 results in a 2 fold decrease in free GSH in both strains as compared to their respective untreated controls. Interestingly, treatment of WT cells with H2O2 decreased [GSSG] eight fold and treatment of ycf1Δ with H2O2 does not alter [GSSG] from the untreated control (Fig2B). The GSH and GSSG free measurements together explain why the [GSH]/[GSSG] ratio increases in H2O2 treated WT cell and decreases in ycf1Δ cells (Fig. 2C). In WT cells treated with 5 mM H2O2, GSSG is being depleted more rapidly than GSH. One explanation for this phenomenon is that GSSG is being rapidly reduced by glutathione reductase in response to H2O2. Alternatively, glutathione synthesis is increasing in response to a cellular decrease in both GSH and GSSG. GSSG levels in ycf1Δ cells are unchanged by treatment with H2O2 suggesting that Ycf1p plays a role in GSH recycling in response against H2O2 stress. Conversely, NaCl treatment results in a two fold increase in GSH content and [GSH/[GSSG] ratio in WT cells and a ~6 fold decrease in the cellular GSH content and a corresponding 6 fold decrease in the [GSH/[GSSG] ratio of ycf1Δ cells as compared to untreated WT and ycf1Δ cells respectively. Consistent with our GSH analysis from H2O2 treated ycf1Δ cells, NaCl treatment does not change cellular GSSG levels. This result suggests that Ycf1p plays an important role in regulating cellular GSH levels under normal basal growth conditions as well as in response to NaCl. GSH cellular levels increase in WT cells and dramatically decrease in ycf1Δ cells in response to salt stress. This result suggests that Ycf1p may play an important role in both recycling GSH under normal basal conditions and in response to salt stress. Further, ycf1Δ- dependent transport of GSH into the vacuole may play an important role in regulating GSH synthesis. The most striking feature of our results is that GSSG levels do not change with either H2O2 or NaCl treatment as compared to the untreated control in ycf1Δ cells and WT cells changes in GSSG levels mirror GSH levels. Our results presented here are in line with previous studies examining the role of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (gammaGT) and Ycf1p in glutathione recycling under cadmium stress [21–22]. The [GSH]/[GSSG] ratio increases 2 fold in WT BY4741 cells in response to cadmium-induced oxidative stress, while GSH levels remain unchanged[21–22]. Further, both deletion of gammaGT and deletion of GSH synthase (Gsh1p) results in increased total protein carbonylation, lipid peroxidation, and ROS[22] and deletion of Ycf1p increases expression of gammaGT[21], suggesting that all of the proteins involved in regulating intracellular GSH levels work in a coordination. The studies described above together with our results, suggest that Ycf1p may play an important role in GSH homeostasis in normal growing cells and in response to oxidative stress. Our results also suggest that one potential mechanism by which Ycf1p regulates GSH homeostasis is in part via GSH sequestration into the vacuole as a metal complex (Cd-SG2 or As-SG3). In future studies it would be interesting to examine to interplay between Ycf1p and GSSG reductase (Glr1p) and gammaGT (Ecm38p/Cis2p) more closely.

Figure 2. NaCl treatment dramatically reduces intracellular GSH in ycf1Δ cells.

Free intracellular GSH (panel A) and the intracellular [GSH]/[GSSG] ratio (panel B) was determined in untreated (black bars) H2O2 treated (grey bars),and NaCl treated (hatched bars) WT and ycf1Δ cells, as described in the Materials and Methods. Statistical analysis was carried-out in Prism Graphpad by One-Way and Two-Way ANOVA analysis with Bonferroni post tests (*=p<0.05, **=p<0.01, all statistics shown are with respect to untreated WT).

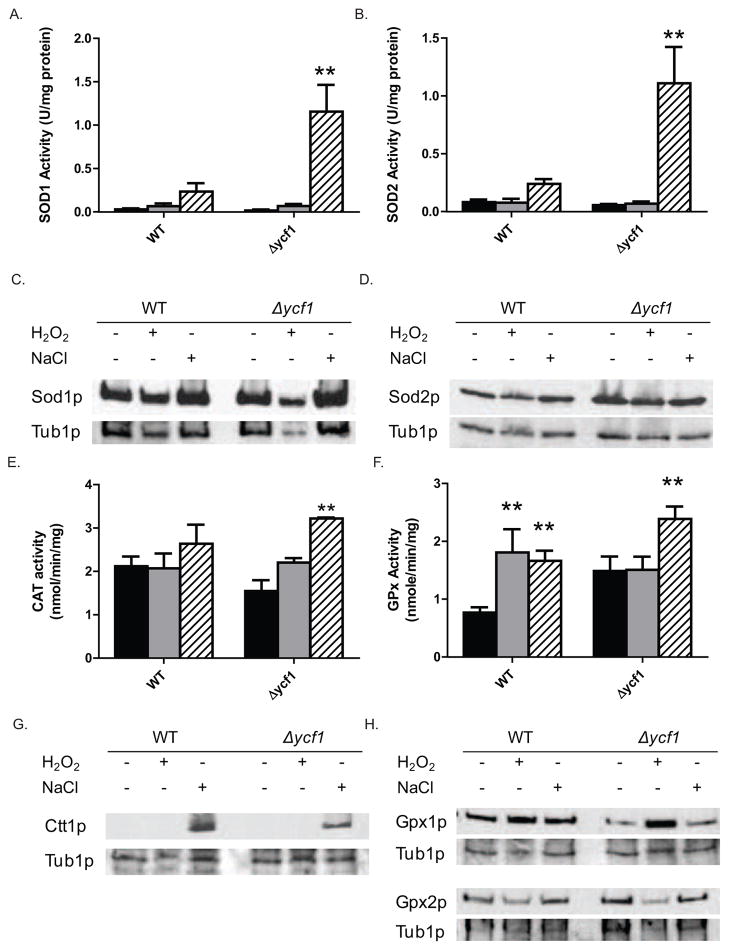

Sod1p (Cu/Zn SOD), Sod2p (Mn SOD) and Ctt1p (catalase) have been shown to be a critical component of the oxidative stress protective mechanism [15]. Interestingly, in the plant Tamarix hispida SOD1, SOD2, and catalase expression all increase in response to salt stress Deletion of Δsod1, Δsod2, or both Δsod1and Δsod2 results in increased sensitivity to salt stress in the yeast Cryptococcus neoformans viability [23]. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Δsod1and Δsod2 cells have increased sensitivity to high salt and H2O2 [13,24–25] and overexpression of Sod1p, Sod2p, and Ctt1p results in varying levels of resistance to H2O2-mediated oxidative stress [25]. The increased sensitivity of Δsod1cells to H2O2 is amplified in cells impaired in GSH synthesis [24] suggesting that the oxidative stress response system and GSH cellular levels are both playing a role in oxidative stress resistance. Further, Δsod1cells have a 2 fold increase in the [GSH]/[GSSG] ratio and Ycf1p expression is increased in Δsod1cells suggesting a role for Sod1p in GSH homeostasis [26]. Therefore, we reasoned that if SOD does indeed play a critical role in protecting cells from salt induced oxidative stress, then it is reasonable to believe that an ycf1Δ cell will have increased SOD activity to compensate for the loss of Ycf1p and GSH recycling. If true this result would explain why ycf1Δ cells are not more sensitive to NaCl stress. O ur results show this to be the case. Sod1p and Sod2p activities do not differ significantly between WT and ycf1-delta cells, both in untreated and H2O2-treated conditions. However, NaCl treatment does induce Sod1p and Sod2p activity about ten fold in ycf1Δ cells as compared to the NaCl treated WT cells (Fig. 3A and 3B). The increase in Sod1p and Sod2p activity is not the result of increased expression, as Sod1p and Sod2p expression levels in WT and ycf1Δ cells do not increase with H2O2 or NaCl treatment (Fig. 3C and 3D). Our result suggests strongly that SOD activity is not only important in cellular resistance to salt stress, but a critical compensatory mechanism for cellular protection against high salt stress in the absence of Ycf1p. Further, Sod1p and Sod2p activity is moderately increased two fold in NaCl treated WT cells as compared to untreated cells. This result supports the hypothesis that SOD plays a role in the general cellular response to salt-induced oxidative stress. Similar to Sod1p and Sod2p, catalase (Ctt1p) activity increases in WT and ycf1Δ cells when treated with NaCl (Fig. 3E). The increased Ctt1p activity in ycf1Δ cells in NaCl treated cells suggests a role for Ctt1p in the cellular response to salt in the absence of ycf1Δ. Although a small increase in Ctt1p activity is shown for WT cells, this increase is not statistically significant (p=0.353). However, the trend toward increased Ctt1p function in WT cells treated with NaCl suggests a potentially minor role in WT cellular response to NaCl and is supported by our analysis of Ctt1p expression in untreated WT and ycf1Δ cells is below detectable levels and upon treatment with NaCl, Ctt1p expression dramatically increases (Fig. 3G). This result suggests that the increase in Ctt1p activity associated with NaCl stress is the result of increased Ctt1p expression, not increase protein function. Since catalase is critical for the further detoxification of super oxide produced by SOD, it is likely that the expression of Ctt1p increases in WT and ycf1Δ cells under NaCl treatment is in response to increased superoxide production from Sod1p and Sod2p. It is important to note that upon overexposure of our Ctt1p western blots, lights bands became apparent in untreated and H2O2 treated WT and ycf1Δ cells representing low basal levels of Ctt1p.

Figure 3. The oxidative stress response systems are upregulated in response to NaCl stress in ycf1Δ cells.

Activities of Sod1p (panel A), Sod2p (panel B), Ctt1p (panel E) and GPx (panel F) were measured in untreated (black bars), H2O2 treated (grey bars) and NaCl treated (hatched bars) WT and ycf1Δ cells, as described in the Materials and Methods. Expression of Sod1p (panel C), Sod2p (panel D), Ctt1p (panel G), Gpx1p and Gpx2p (panel H) was measured by Western blot in untreated (black bars), H2O2 treated (grey bars) and NaCl treated (hatched bars) WT and ycf1Δ cells, as described in the Materials and Methods. Statistical analysis was carried-out in Prism Graphpad by Two-Way ANOVA analysis with Bonferroni post tests (*=p<0.05, **=p<0.01) where untreated WT and ycf1Δ served as controls for their respective treatment conditions, either NaCl or H2O2.

Our finding that Ycf1p plays an important role in the regulation of GSH levels under normal basal growth conditions and during salt stress is supported by our analysis of GPx activity in WT and ycf1Δ cells under unstressed and H2O2 and NaCl stress. Our analysis showed that GPx activity is increased in WT cells in response to H2O2 and NaCl (Fig. 3F). Our result showing increased GPx activity in response to H2 O2 recapitulates what has been previously reported. Deletion of ycf1Δ alone results in increased GPx activity as compared to WT cells, further emphasizing the role of Ycf1p in normal (unstressed) redox balance/maintenance. Interestingly, GPx activity does not increase in H2O2 treated ycf1Δ cells as compared to untreated ycf1Δ cells and suggests that treatment of ycf1Δ cells with H2O2 does not increase cellular stress to such an extent as to warrant an increase in GPx activity. GPx activity increases about 40% in ycf1Δ cells treated with NaCl as compared to the untreated control (Fig. 3G). The increase in GPx activity appears to be the result of two distinct pathways for H2O2 and NaCl stress. The increase in GPx activity in response to H2O2 treatment appears to be the result of increased Gpx1p expression (Fig. 3H). However, the increase in GPx activity measured in NaCl treated cells is not the result of an increase in Gpx1p or Gpx2p expression, but rather via some other mechanism, possibly post-translational regulation. Our results presented here show that increased Sod1p, Sod2p and Ctt1p activity is a major mechanism of cellular resistance to salt stress in the absence of functional Ycf1p. Again our results suggest an important role for Ycf1p in regulating cellular GSH homeostasis in response to oxidative stress

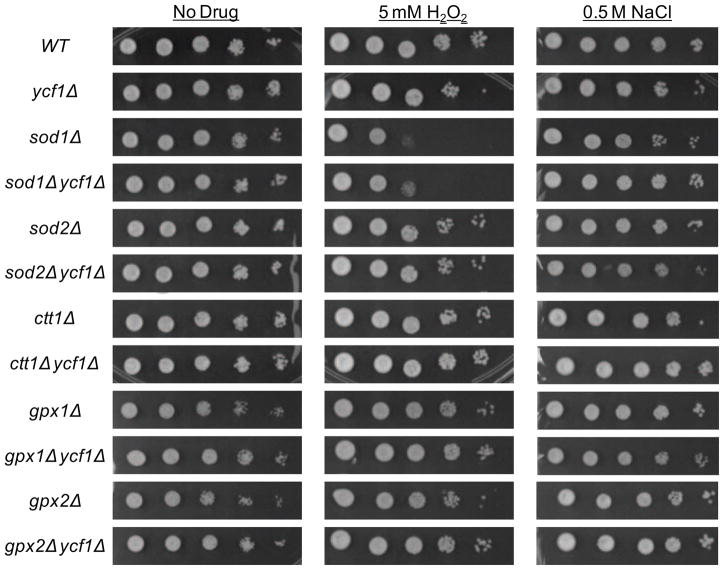

Our studies as in shown in Fig. 3 suggest that Ycf1p, Sod1p, Sod2p, Ctt1p, Gpx1p, and Gpx2p work together to protect the cell from oxidative stress from NaCl. Based on this finding it is reasonable to hypothesize that if a double deletion of Ycf1p and either Sod1p, Sod2p, Ctt1p, Gpx1p, or Gpx2p was made then this strain would have increased sensitivity to NaCl as compared to either of the single deletions alone. Therefore double deletions of Ycf1p and Sod1p, Sod2p, Ctt1p, Gpx1p, or Gpx2p were created and their ability to grow as compared to the single deletions strain was tested by spot test on 0.5 M NaCl containing plates, plates containing the general oxidant stressor H2O2, or vehicle alone (Fig. 4). Contrary to our hypothesis neither single deletions of Ycf1p, Sod1p, Sod2p, Ctt1p, Gpx1p, and Gpx2p nor double deletions of Ycf1p and Sod1p,, Sod2p, Ctt1p, Gpx1p, and Gpx2p significantly increased cellular sensitivity to NaCl. It is important to note that although no single or double deletion significantly increase cellular sensitivity to NaCl, deletion of sod1Δ and ctt1Δ slightly increased cellular sensitivity to NaCl to a level similar to that of ycf1Δ as shown by an increase in the number of colonies that grew at the most dilute concentrations of cells plated. However, deletion of sod1Δ drastically increased cell sensitivity to H2O2 and contrary to our hypothesis the double deletion of ycf1Δ sod1Δ decreased sensitivity to H2O2 as compared to the sod1Δ strain. This finding can be explained in the text of cellular GSH content. ycf1Δ cells have increased GSH content as compared to WT cells and the increased GSH will act similar to a sponge in reducing the H2O2-induced oxidative stress; therefore, in some circumstances it would stand to reason that deletion of ycf1Δ will be protective against oxidative stress agents. We see deletion of ycf1Δ creates a similar effect as overexpression of the GSH synthesis pathway genes. This resultis in agreement with the finding that increased sensitivity of Δsod1cells to H2O2 is amplified in cells impaired in GSH synthesis [24]. Further, a similar effect can be seen for the ycf1Δ sod1Δ and ycf1Δ ctt1Δ as compared to the single deletion strains sod1Δ and ctt1Δ when exposed to NaCl. The slight sensitivity to NaCl is seen in the sod1Δ and ctt1Δ and is rescued by deletion of ycf1Δ. Together these findings support roles for Ycf1p, Sod1p, Sod2p, and Ctt1p is cellular resistance against NaCl and H2O2, and strongly suggests that Ycf1p-mediated regulation of GSH levels plays an underlying role in protecting cells from normal oxidative stress during basal cell growth and a supporting role under NaCl and H2O2-induced oxidative stress conditions. Furthermore, our results suggest that Ycf1p works in cooperation with Sod1p, Sod2p, and Ctt1p to decrease NaCl and H2O2-induced oxidative stress in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. As a whole, these findings suggest the intriguing possibility that the human Ycf1p homologue, MRP1, may work together with human SOD1, SOD2, and Catalase to protect cells from a broad range of oxidative stressors under both normal basal growth conditions and when cells are exposed to toxins that induce oxidative stress.

Figure 4. Deletion of Ycf1p in Sod1p and Ctt1p deletion strains increases cellular resistance to NaCl and H2O2.

WT, ycf1Δ , sod1Δ, sod1Δ ycf1Δ, sod2Δ, sod2Δ ycf1Δ, ctt1Δ, ctt1Δ ycf1Δ, gpx1Δ, gpx1Δ ycf1Δ, and gpx2Δ, gpx2Δ ycf1Δ were tested for growth by spot test on plates containing vehicle alone,5 mM H2O2, and 0.5 M NaCl as described in the materials and methods..

Highlights.

Ycf1p plays an important role in glutathione (GSH) recycling under condition of high salt stress induced oxidative stress

Reduced glutathione recycling, resulting from deletion of Ycf1p, induces Sod1p, Sod2p, and Ctt1p activity

Increased Sod1p, Sod2p, and Ctt1p activities compensate for a reduction in cellular GSH and a reduced [GSH]/[GSSG] ratio in salt stressed ycf1Δ cells.

Acknowledgments

CMP is supported by NIH P20 RR020171. KAP is supported by a Summer Research Grant from the Centre College Faculty Development Committee.

Abbreviations

- YCF1

yeast cadmium factor 1

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- GPx

glutathione peroxidase

- CAT

catalase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- ABC

ATP binding cassette

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dean M. The genetics of ATP-binding cassette transporters. Methods Enzymol. 2005;400:409–29. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottesman MM, Ambudkar SV. Overview: ABC transporters and human disease. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2001;33:453–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1012866803188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haimeur A, Conseil G, Deeley RG, Cole SP. The MRP-related and BCRP/ABCG2 multidrug resistance proteins: biology, substrate specificity and regulation. Curr Drug Metab. 2004;5:21–53. doi: 10.2174/1389200043489199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cole SP, et al. Overexpression of a transporter gene in a multidrug-resistant human lung cancer cell line. Science. 1992;258:1650–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1360704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li ZS, Lu YP, Zhen RG, Szczypka M, Thiele DJ, Rea PA. A new pathway for vacuolar cadmium sequestration in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: YCF1-catalyzed transport of bis(glutathionato)cadmium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:42–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li ZS, Szczypka M, Lu YP, Thiele DJ, Rea PA. The yeast cadmium factor protein (YCF1) is a vacuolar glutathione S-conjugate pump. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6509–17. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.11.6509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paumi CM, Chuk M, Snider J, Stagljar I, Michaelis S. ABC transporters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and their interactors: new technology advances the biology of the ABCC (MRP) subfamily. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:577–93. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00020-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rebbeor JF, Connolly GC, Dumont ME, Ballatori N. ATP-dependent transport of reduced glutathione on YCF1, the yeast orthologue of mammalian multidrug resistance associated proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33449–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suzuki H, Sugiyama Y. Excretion of GSSG and glutathione conjugates mediated by MRP1 and cMOAT/MRP2. Semin Liver Dis. 1998;18:359–76. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paumi CM, Chuk M, Chevelev I, Stagljar I, Michaelis S. Negative regulation of the yeast ABC transporter Ycf1p by phosphorylation within its N-terminal extension. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:27079–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802569200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paumi CM, et al. Mapping protein-protein interactions for the yeast ABC transporter Ycf1p by integrated split-ubiquitin membrane yeast two-hybrid analysis. Mol Cell. 2007;26:15–25. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pickin KA, Ezenwajiaku N, Overcash H, Sethi M, Knecht MR, Paumi CM. Suppression of Ycf1p function by Cka1p-dependent phosphorylation is attenuated in response to salt stress. FEMS Yeast Res. 2010 doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00677.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dziadkowiec D, Krasowska A, Liebner A, Sigler K. Protective role of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase against high osmolarity, heat and metalloid stress in saccharomyces cerevisiae. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2007;52:120–6. doi: 10.1007/BF02932150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saha P, Chatterjee P, Biswas AK. NaCl pretreatment alleviates salt stress by enhancement of antioxidant defense system and osmolyte accumulation in mungbean (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek) Indian J Exp Biol. 2010;48:593–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang J, Wang Y, Liu G, Yang C, Li C. Tamarix hispida metallothionein-like ThMT3, a reactive oxygen species scavenger, increases tolerance against Cd(2+), Zn(2+), Cu(2+), and NaCl in transgenic yeast. Mol Biol Rep. 2011;38:1567–74. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burke D, Dawson D, Stearns T. Methods in Yeast Genetics. CSHL; Cold Spring Harbor: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Murdock G, Bagley D, Jia X, Ward DM, Kaplan J. Genetic dissection of a mitochondria-vacuole signaling pathway in yeast reveals a link between chronic oxidative stress and vacuolar iron transport. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10232–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.096859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sultana R, Newman SF, Huang Q, Butterfield DA. Detection of carbonylated proteins in two-dimensional sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis separations. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;476:153–63. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-129-1_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collinson EJ, Wheeler GL, Garrido EO, Avery AM, Avery SV, Grant CM. The yeast glutaredoxins are active as glutathione peroxidases. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16712–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111686200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mehdi K, Thierie J, Penninckx MJ. gamma-Glutamyl transpeptidase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its role in the vacuolar transport and metabolism of glutathione. Biochem J. 2001;359:631–7. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3590631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Adamis PD, Mannarino SC, Eleutherio EC. Glutathione and gamma-glutamyl transferases are involved in the formation of cadmium-glutathione complex. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:1489–92. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adamis PD, Panek AD, Eleutherio EC. Vacuolar compartmentation of the cadmium-glutathione complex protects Saccharomyces cerevisiae from mutagenesis. Toxicol Lett. 2007;173:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narasipura SD, Chaturvedi V, Chaturvedi S. Characterization of Cryptococcus neoformans variety gattii SOD2 reveals distinct roles of the two superoxide dismutases in fungal biology and virulence. Mol Microbiol. 2005;55:1782–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernandes PN, Mannarino SC, Silva CG, Pereira MD, Panek AD, Eleutherio EC. Oxidative stress response in eukaryotes: effect of glutathione, superoxide dismutase and catalase on adaptation to peroxide and menadione stresses in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Redox Rep. 2007;12:236–44. doi: 10.1179/135100007X200344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guaragnella N, Antonacci L, Giannattasio S, Marra E, Passarella S. Catalase T and Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase in the acetic acid-induced programmed cell death in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:210–4. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adamis PD, Gomes DS, Pereira MD, Freire de Mesquita J, Pinto ML, Panek AD, Eleutherio EC. The effect of superoxide dismutase deficiency on cadmium stress. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2004;18:12–7. doi: 10.1002/jbt.20000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]