Abstract

This study used positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET–CT) to evaluate the effects of 4 anesthetic protocols on 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-D-glucose (18F-FDG) accumulation in the brains and hearts of miniature pigs (Sus scrofa domestica). The 18F-FDG standard uptake value was quantified by dividing the brain into 6 regions: cerebellum, brainstem, and frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes. Five (2 female and 3 male) clinically normal miniature pigs were premedicated with medetomidine (200 μg/kg IM) after which the following 4 anesthetic protocols were administered by using a crossover design: 1) propofol (4 mg/kg IV)–isoflurane inhalation; 2) propofol (4 mg/kg IV); 3) ketamine (5 mg/kg IV); 4) tiletamine–zolazepam (4.4 mg/kg IM). Compared with levels after other protocols, brain accumulation of 18F-FDG increased during propofol anesthesia but decreased with tiletamine–zolazepam. Relative to that due to other protocols, heart accumulation of 18F-FDG increased with propofol–isoflurane anesthesia but decreased with tiletamine–zolazepam. Comparing glucose accumulation in the brain and heart of miniature pigs by using PET–CT, we found that glucose accumulation varied according to the anesthetic protocol and between the 2 organs. These results can be used to evaluate how different anesthetic agents affect glucose metabolism in brain and heart of miniature pigs. Furthermore, these data should be considered when selecting an anesthetic agent for miniature pigs that will undergo PET–CT imaging with 18F-FDG.

Abbreviation: CBF, cerebral blood flow; PET–CT, positron emission tomography–computed tomography; SUV, standard uptake value

In recent years, miniature pigs have been used widely in biomedical research. Their small size relative to that of other large animals facilitates housing and handling, and their ample blood volume permits frequent serial blood collection, which can be problematic in rodents. In addition, miniature pigs are similar to humans in physiologic structure, state, and organ size.

Use of general anesthesia allows procedural ease, efficiency, and minimization of stress to the animal. Many types of anesthesia can be used for pigs during scanning procedures and surgery. To avoid possible side effects of anesthesia on research results, some investigators rely on physical restraint. However, restraint can also induce stress and affect results.27

Although imaging techniques do not cause pain, anesthesia is necessary so that animals do not move during the imaging procedure.2 Therefore, sedation and muscle relaxation are important.2 However, anesthetic drugs vary in their capacity to interfere with homeostatic mechanisms responsible for glucose metabolism.15 A glucose analog, 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-d-glucose (18F-FDG), is the most frequently used positron emission tomography (PET) radiotracer. PET coupled with computed tomography (CT) and using 18F-FDG is a valuable tool for detecting abnormal glucose metabolism and is widely applied in animal studies of the brain and heart, 2 major functional organs of glucose metabolism.17,29 However, the effects of various anesthetics during PET imaging of miniature pigs have not been reported. Furthermore, little is known about anesthetic effects on 18F-FDG accumulation in the brain and heart of miniature pigs. The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the effects of 4 anesthesia regimens on 18F-FDG accumulation in the brains and hearts of miniature pigs to establish baseline conditions for PET imaging of this animal model.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Five (2 female, 3 male) SPF miniature pigs (crossbreds of PWG micropigs and Yucatan, native, pigmy, and miniature potbelly pigs) were obtained from Medi Kinetics (Pyeongtaek, Korea). All pigs were quarantined for 4 wk before use in experiments and were clinically healthy prior to the study. The pigs (age, approximately 6 mo; weight, 9.8 to 17.62 kg) were individually housed in stainless-steel cages (152 × 92 × 102 cm) and fed ad libitum a standard commercial pig diet (Lab Pig Chow, Purina Korea, Gyeonggi, Korea) once daily. Fresh water purified by reverse osmosis was provided ad libitum. Pigs were housed in a barrier facility on a 12:12-h light:dark cycle (lights on at 0800) with a room temperature of 23 ± 1 °C, a relative humidity of 50% ± 5%, and 25 complete changes of filtered air hourly. The study protocol was approved by the University of Konkuk IACUC.

Anesthetic protocols.

This study used a crossover design, with each pig exposed to each anesthetic protocol and a 2-wk washout period between protocols. All pigs were food-fasted for 6 h prior to administration of anesthesia, with free access to drinking water. All pigs were premedicated with medetomidine (200 μg/kg IM; Domitor, Pfizer Korea, Seoul, Korea), and anesthesia was administered after the pigs became sedated. Local anesthetic cream (lidocaine 2% jelly, Astra, Sodertalje, Sweden) was applied to the pigs’ ears 45 min prior to administration of anesthesia to prevent pain during insertion of an ear-vein catheter. The 4 anesthetic protocols evaluated were as follows: 1) propofol (4 mg/kg IV; Provive 1%, Myungmoon Pharm, Hwasung, Korea) to facilitate orotracheal intubation followed by isoflurane (Ifran, Hana Pharm, Seoul, Korea) administered at 1.5 to 2% with 100% oxygen for maintenance; 2) propofol (4 mg/kg IV; Provive 1%, Myungmoon Pharm); 3) ketamine hydrochloride (5 mg/kg IV; Yuhan, Gunpo, Korea); and 4) tiletamine–zolazepam (4.4 mg/kg IM; Virbac, Carros, France). After administration of the anesthetic medication, an endotracheal tube was inserted and a mechanical ventilator connected to provide 100% O2, because arterial carbon dioxide and oxygen concentration levels need to be maintained throughout brain PET studies.32 Pigs were monitored until fully recovered from anesthesia.

These protocols and dosages were selected based on those reported previously.4,38 Blood glucose measured prior to 18F-FDG administration (mean, 104.6 ± 26.9 mg/dL) was within the normal reference range (43 to 133 mg/dL) in all pigs.4

18F-FDG–PET scanning.

18F-FDG (148 MBq, 4 mCi) was administered intravenously 1 h prior to PET–CT imaging (Gemini PET–CT, Philips, Eindhoven, The Netherlands) of the brain and heart. A 50- to 60-min interval between 18F-FDG administration and imaging is sufficient obtain a useful tumor:background ratio of the tracer.5

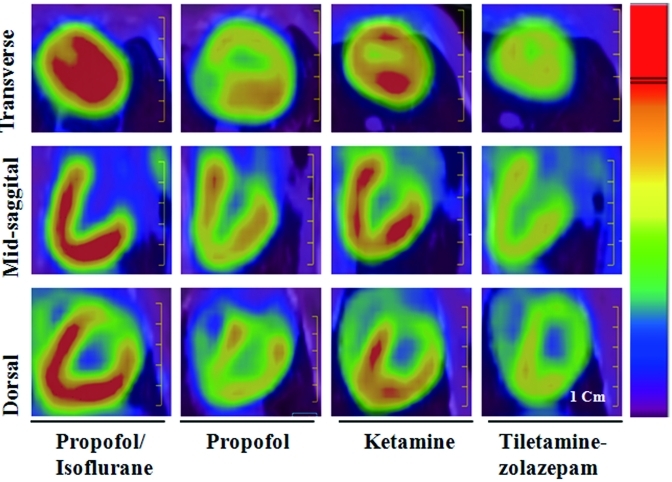

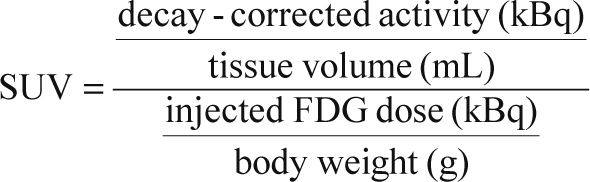

The scanning time for PET–CT was 20 min; PET scans were acquired immediately after CT imaging. The PET images were derived from section slices with a thickness of 4 mm, and 170- to 200-section images were obtained. The CT images were derived from section slices with a thickness of 3.2 mm, and 370- to 400-section images were acquired. The PET–CT images were reconstituted by using 3D Row Action Maximum Likelihood Algorithms and fused by using Syntegra software (version 2.1F; Philips). The 18F-FDG standard uptake value (SUV) was quantified by dividing the brain into 6 regions: frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes; cerebellum; and brainstem. The region of interest within each brain and heart region was determined by consensus among one laboratory animal technician, 2 veterinarians, and one person experienced in human nuclear imaging. Manual drawings of transverse, midsagittal, and dorsal images were made (Figures 1 and 2). The SUV with a region of interest around the focal 18F-FDG accumulation zone was calculated by using a whole-body protocol according to the following formula:

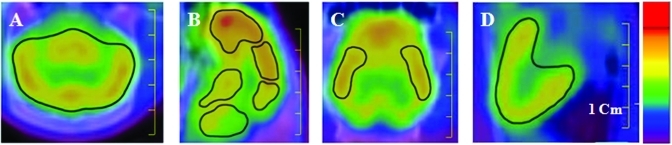

Figure 1.

Images from 18F-FDG–PET-CT of miniature pigs. Regions of interest were manually drawn from the (A) transverse (whole brain), (B) midsagittal (frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes; cerebellum; and brainstem), (C) dorsal (temporal lobe), and (D) midsagittal (heart) images. The color indicates the relative 18F-FDG concentration (from red [high] to blue [low]) in the respective image. Scale bar, 1 cm.

Figure 2.

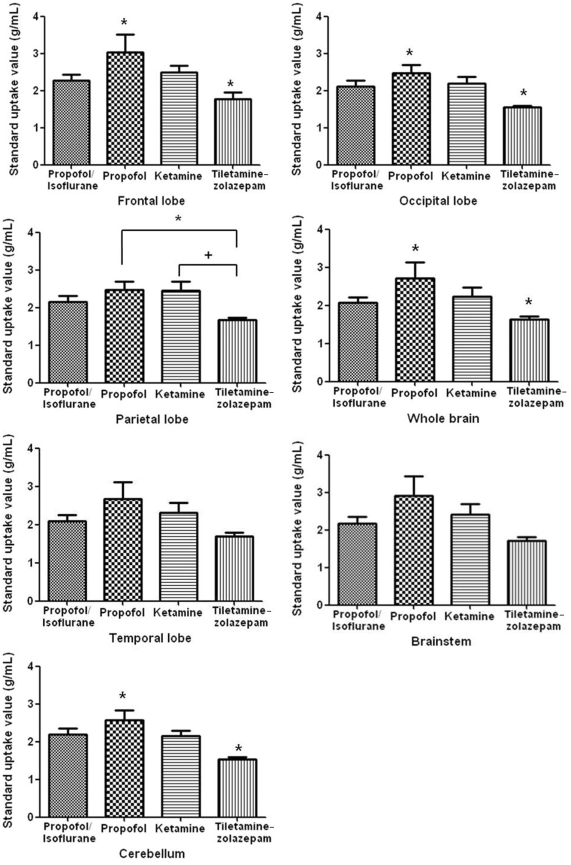

Standard uptake values of 18F-FDG in the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes; cerebellum; brainstem; and whole brain of normal miniature pigs (n = 5) anesthetized by using 4 different protocols. Values within a brain region that are indicated by similar symbols (*, +) are significantly (P < 0.05) different between anesthetic protocols.

|

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism for Windows (version 4.0; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Data were recorded as mean ± SEM and analyzed by Kruskal–Wallis test; and P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. If significant differences were detected, Dunn multiple comparisons were performed.

Results

Brain.

Each of the 6 brain regions showed at least one difference in SUV between the 4 anesthetic protocols used in the miniature pigs (Figures 2 and 3). Kruskal–Wallis tests showed significant (P < 0.05) differences between propofol and tiletamine–zolazepam and between ketamine and tiletamine–zolazepam. For all brain regions, the SUV for propofol-anesthetized miniature pigs was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than those for all other anesthetic protocols. The lowest 18F-FDG accumulation occurred in the brains of tiletamine–zolazepam-anesthetized pigs, with greater (P < 0.05) glucose accumulation in the frontal lobe than other regions. The SUV for the frontal lobe (3.03 ± 1.09 g/mL) of propofol-anesthetized miniature pigs was significantly higher than other regions; the occipital lobe of propofol-anesthetized pigs showed the lowest SUV (2.46 ± 0.53 g/mL). In tiletamine–zolazepam-anesthetized miniature pigs, SUV was significantly higher in the frontal lobe (1.78 ± 0.37 g/mL) than other regions. The lowest SUV in tiletamine–zolazepam-anesthetized miniature pigs occurred in the occipital lobe (1.54 ± 0.10 g/mL) and cerebellum (1.54 ± 0.11 g/mL).

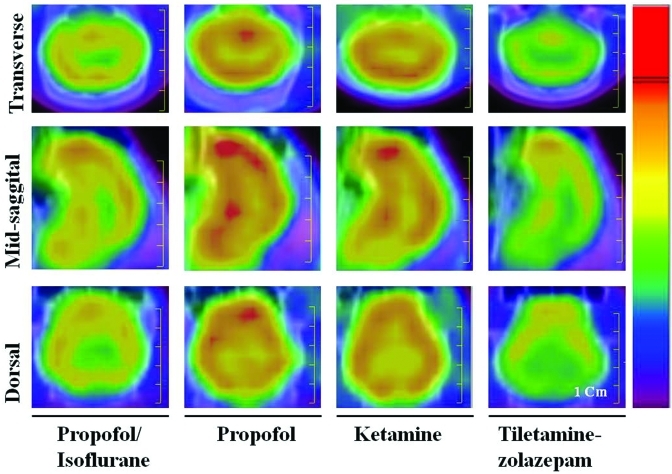

Figure 3.

Comparison of features in 18F-FDG–PET images from transverse, midsagittal, and dorsal views between propofol–isoflurane, propofol, ketamine, and tiletamine–zolazepam anesthetic protocols. The color indicates the relative 18F-FDG concentration (from red [high] to blue [low]) in the respective image. Scale bar, 1 cm.

Heart.

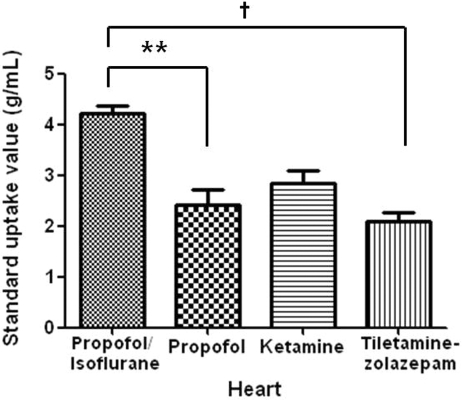

In all of the miniature pigs, the propofol–isoflurane combination (4.23 ± 0.31 g/mL) yielded the highest coronary glucose accumulation values and tiletamine–zolazepam the lowest (2.10 ± 0.38 g/mL; Figures 4 and 5). In addition, SUV were higher in the pigs anesthetized with ketamine (2.85 ± 0.55 g/mL) compared with propofol (2.43 ± 0.63 g/mL). Kruskal–Wallis tests showed significant differences between propofol–isoflurane and propofol (P < 0.05) and between propofol–isoflurane and tiletamine–zolazepam (P < 0.01).

Figure 4.

Standard uptake values of 18F-FDG obtained from hearts of normal miniature pigs (n = 5) anesthetized by using different anesthetic protocols. *, Significant (P < 0.05) difference between values for propofol–isoflurane and ketamine; †, significant (P < 0.01) difference between values for propofol–isoflurane and tiletamine–zolazepam.

Figure 5.

Comparison of features with 18F-FDG–PET images in transverse, midsagittal, and dorsal views between propofol–isoflurane, propofol, ketamine, and tiletamine–zolazepam. The color indicates the relative 18F-FDG concentration (from red [high] to blue [low]) in the respective image. Scale bar, 1 cm.

Discussion

Anesthesia has significant effects on the central nervous, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems.43 PET using radiolabeled tracers allows molecular imaging of physiologic events in living subjects.43,18F-FDG is an analog of glucose and is taken up and trapped by living cells during the first stages of the normal glucose pathway. The rationale behind the use of 18F-FDG as a tracer for cancer diagnosis is based on the increased glycolytic activity in neoplastic cells.5 In the present study, we evaluated the effects of 4 different anesthetic protocols on 18F-FDG accumulation in the brains and hearts of miniature pigs. We found that 18F-FDG accumulation varied according to the type of anesthetic agents used and between the brain and heart.

The 4 anesthetic protocols we evaluated had different effects on the hearts of miniature pigs. Specifically, isoflurane increased 18F-FDG accumulation, whereas tiletamine–zolazepam decreased accumulation. Volatile anesthetics have been shown to have cardioprotective41,42 and vasodilatory effects11,20,37 that are mediated by activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels in cardiac myocytes and vascular smooth muscle cells, respectively.40 Isoflurane currently is recommended as the primary inhalant anesthetic for use in swine36 and has been shown to increase coronary blood flow (and decrease coronary vascular resistance) in swine.9 Isoflurane-induced dilation of porcine coronary arterioles is mediated by K–ATP channels.20,40 Whereas isoflurane causes the mitochondrial K–ATP channels in cardiac myocytes to open, the intravenous anesthetics propofol and pentobarbital have been reported to have no direct effect on mitochondrial K–ATP channels.22 These mitochondrial KATP channel mechanisms may explain why isoflurane, compared with other anesthetic agents, caused 18F-FDG accumulation to increase in the hearts of the pigs in our current study.

As in the heart, the 4 anesthetic regimes we investigated had different effects on the brains of minipigs. Specifically, propofol increased 18F-FDG accumulation whereas tiletamine–zolazepam decreased accumulation compared with that due to other anesthetic protocols. In the brain, glucose is taken up by astrocytes or enters neurons, and PET–CT using 18F-FDG enables visualization of cerebral glucose metabolism. 18F-FDG is phosphorylated by hexokinase; however, unlike glucose, 18F-FDG does not participate further in the glycolysis pathway. Therefore, 18F-FDG is trapped in the cells, mainly in astrocytes.30,34 Glucose uptake into astrocytes is known to be coupled to astrocytic glutamate uptake.28 ATP generated from glycolysis is responsible for the cycling of glutamate between neurons and astrocytes.35 Consequently, glutamate regulates astrocytic glucose metabolism in a concentration-dependent manner.34,39

Anesthetics (for example, isoflurane, propofol, ketamine, and tiletamine–zolazepam) are widely recognized to act on glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons.18 Glutamate is the signal molecule at the glutamatergic neurons and is the precursor of GABA, which is released from GABAergic neurons. Anesthetics might affect the astrocytic glutamate concentration, and concomitantly, cerebral glucose metabolism; however, the mechanisms of action underlying these effects are still unknown. In addition, the transporter system involved in astrocytic glutamate uptake varies and is distributed differentially at the level of neuronal cells and brain regions.12 These differences in distribution, as well as other factors, may affect regional differences in glucose metabolism as measured by PET–CT.

No information is available on the effects of tiletamine–zolazepam on heart glucose utilization. Tiletamine (2-[ethylamino]-2-[2-thienyl] cyclohexanone hydrochloride) is a dissociative anesthetic agent with pharmacologic properties similar to those of ketamine, but the potency and duration of action of tiletamine are intermediate between those of long-acting phencyclidine and short-acting ketamine.3 Zolazepam (4-[o-fluorophenyl]-6,8-dihydro-1,3,8-trimethylpyrzolo[3,4-e] [1,4]diazepine-7[1H]-1) is a benzodiazepine derivative with pharmacologic properties similar to those of diazepam.3 Tiletamine–zolazepam is a 1:1 mixture by weight of tiletamine and zolazepam that depresses cardiorespiratory functions.14,25 These effects may explain the decreased 18F-FDG accumulation in the hearts of pigs that received tiletamine–zolazepam. Many anesthetics cause some degree of cardiovascular alteration in animals;7,8 however, little is known about the mechanism(s) of action of these drugs at relevant central autonomic sites.6,7

Anesthesia can influence brain physiology, including cerebral glucose metabolism and cerebral blood flow (CBF).32 Ketamine induces increased CBF and cerebral glucose metabolism in humans.23 Isoflurane has been reported to decrease regional cerebral glucose metabolism and CBR, leading to decreased cerebral accumulation of 18F-FDG as measured by PET imaging, in humans.1 We obtained similar results in our pigs. However, the use of isoflurane as an anesthetic in rats has been shown to increase regional brain metabolism.33 The use of propofol as an anesthetic decreases glucose metabolism and regional CBF in humans.21 The differences between CBF and 18F-FDG accumulation in response to anesthetics is not known definitively for many different species. Our results were similar to those recently reported from isoflurane-anesthetized mice, in which administration of identical doses of 18F-FDG resulted in lower 18F-FDG accumulation in brain than in heart.43 In rhesus monkeys, ketamine anesthesia increased 18F-FDG accumulation in brain, as determined by PET–CT.19 Results from a study in dogs were opposite to our findings in swine. Specifically, the SUV in brain indicated the greatest 18F-FDG accumulation for dogs anesthetized with a combination of medetomidine–tiletamine–zolazepam and the least accumulation in those given propofol–isoflurane. 26 These differences in accumulation may be due to differences in specific brain features, such as CBF, which is known to vary by species,16 sex,10 and age.13

Pigs must be anesthetized prior to administration of 18F-FDG for PET–CT imaging. We used medetomidine as premedication for all pigs and therefore did not measure the 18F-FDG SUV for this independent anesthetic agent. To our knowledge, no information is available on the effects of a medetomidine mixture on glucose utilization by the brain and heart. One of the limitations of our study was that only a small number of animals was evaluated. More animals should be tested for each anesthetic agent to accurately evaluate 18F-FDG accumulation in miniature pigs by using PET–CT imaging.

The SUV reported for abnormal human cardiac sarcoidosis (2.51 to 14.70 g/mL) were much higher than those in normal human tissue (1.86 to 1.98 g/mL).31 An SUV greater than 2.5 is considered a malignant characteristic in humans.24 The differences in heart SUV due to the different anesthetic agents (2.1 to 4.2 g/mL) used in the current study are clinically significant and has the potential to influence experimental outcomes. Therefore, the anesthetic agent for PET imaging procedures with 18F-FDG in miniature pigs should be selected carefully.

In conclusion, by using PET–CT to measuring 18F-FDG SUV, we showed that the SUV varies according to the anesthetic agent used and organ evaluated. We also found that SUV differed between various parts of the brain. These results illustrate how different anesthetic agents affect glucose metabolism in the brains and hearts of miniature pigs. Furthermore, we suggest that the predicted analytic results of each data set are important factors to consider when selecting an anesthetic agent for use during 18F-FDG–PET imaging studies in miniature swine.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant (no. 20070401034011) from the BioGreen 21 Program, Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

References

- 1.Alkire MT, Haier RJ, Shah NK, Anderson CT. 1997. Positron emission tomography study of regional cerebral metabolism in humans during isoflurane anesthesia. Anesthesiology 86:549–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alstrup AKO, Winterdahl M. 2009. Imaging techniques in large animals. Scand J Lab Anim Sci 36:55–66 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aydlek N, Ceylan C, Ipek H, Gudogdu U. 2007. Effects of xylazine-diazepam-ketamine and xylazine-tiletamine-zolazepam anesthesia on some coagulation parameters in horses. Yyu Vet Fak Derg 18:55–58 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bollen PJ, Hansen AK, Rasmussen HJ. 2000. The laboratory swine, p 14. London (UK): CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bombardieri E, Aktolun C, Baum RP, Bishof-Delaloye A, Buscombe J, Chatal JF, Maffioli L, Moncayo R, Mortelmans L, Reske SN. 2003. 18F-FDG–PET: procedure guidelines for tumour imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 30:115–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchanan KC, Burge RR, Rubble GR. 1998. Evaluation of injectable anesthetics for major surgical procedures in guinea pigs. Contemp Top Lab Anim Sci 37:58–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calderwood HW, Klide AM, Cohn BB. 1971. Cardiorespiratory effects of tiletamine in cats. Am J Vet Res 32:1511–1515 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carpati CM, Astiz ME, Saha DC, Rackow EC. 1993. Diphosphoryl lipid A from Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides induces tolerance to endotoxic shock in the rat. Crit Care Med 21:753–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng DC, Moyers JR, Knutson RM, Gomez MN, Tinker JH. 1992. Dose-response relationship of isoflurane and halothane versus coronary perfusion pressures effects on flow redistribution in a collateralized chronic swine model. Anesthesiology 76:113–122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cosgrove KP, Mazure CM, Staley JK. 2007. Evolving knowledge of sex differences in brain structure, function and chemistry. Biol Psychiatry 62:847–855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crystal GJ, Gurevicius J, Ramez Salem M, Zhou X. 1997. Role of adenosine triphosphate-sensitive potassium channels in coronary vasodilation by halothane, isoflurane, and enflurane. Anesthesiology 86:448–458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Danbolt NC. 2001. Glutamate uptake. Prog Neurobiol 65:1–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erecinska M, Cherian S, Silver IA. 2004. Energy metabolism in mammalian brain during development. propofolg Neurobiol 73:397–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrari L, Turrini G, Rostello C, Guidi A, Casartelli A, Piaia A, Sartori M. 2005. Evaluation of 2 combinations of Domitor, Zoletil100, and Euthatal to obtain long-term nonrecovery anesthesia in Sprague–Dawley rats. Comp Med 55:256–264 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia C, Julier K, Bestmann L, Zollinger A, von Segesser LK, Pasch T, Spahn DR, Zaugg M. 2005. Preconditioning with sevoflurane decrease PECAM1 expression and improves 1-year cardiovascular outcome in coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Br J Anaesth 94:159–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hardy P, Nuyt AM, Dumont I, Peri KG, Hou X, Varma DR, Chemtob S. 1999. Developmentally increased cerebrovascular NO in newborn pigs curtails cerebral blood flow autoregulation. Pediatr Res 46:375–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heim KE, Morrell JS, Ronan AM, Tagliaferro AR. 2002. Effects of ketamine–xylazine and isoflurane on insulin sensitivity in dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate-treated minipigs. Comp Med 52:233–237 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hemmings HC, Jr, Akabas MH, Goldstein PA, Trudell JR, Orser BA, Harrison NL. 2005. Emerging molecular mechanisms of general anesthetic action. Trends Pharmacol Sci 26:503–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Itoh T, Wakahara S, Suzuki K, Kobayashi K, Inoue O. 2005. Effects of anesthesia upon 18F-FDG uptake in rhesus monkey brains. Ann Nucl Med 19:373–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeong Y-B, Kim JS, Jeong S-M, Park JW, Choi IC. 2006. Comparison of the effects of sevoflurane and propofol anaesthesia on regional cerebral glucose metabolism in humans using positron emission tomography. J Int Med Res 34:374–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaisti KK, Langsjo JW, Aalto S, Oikonen V, Sipila H, Teras M, Hinkka S, Metsahonkala L, Scheinin H. 2003. Effects of sevoflurane, propofol, and adjunct nitrousoxide on regional cerebral blood flow, oxygen consumption, and blood volume in humans. Anesthesiology 99:603–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohro S, Hogan QH, Nakae Y, Yamakage M, Bosnjak ZJ. 2001. Anesthetic effects on mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K channel. Anesthesiology 95:1435–1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langsjo JW, Maksimow A, Salmi E, Kaisti K, Aalto S, Oikonen V, Hinkka S, Aantaa R, Sipila H, Viljanen T, Parkkola R, Scheinin H. 2005. S-ketamine anesthesia increases cerebral blood flow in excess of the metabolic needs in humans. Anesthesiology 103:258–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LeBlanc AK, Jakoby B, Townsend DW, Daniel GB. 2008. Thoracic and abdominal organ uptake of 2-deoxy-2[18F]fluoro-d-glucose(18FDG) with positron emission tomography in the normal dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 49:182–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee JY, Jee HC, Jeong SM, Park CS, Kim MC. 2010. Comparison of anesthetic and cardiorespiratory effects of xylazine or medetomidine in combination with tiletamine–zolazepam in pigs. Vet Rec 167:245–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee MS, Ko J, Lee AR, Lee IH, Jung MA, Austin B, Chung HW, Nahm SS, Eom KD. 2010. Effects of anesthetic protocol on normal canine brain uptake of 18F-FDG assessed by PET–CT. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 51:130–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madrigal JL, Garcia-Bueno B, Caso JR, P'erez-Nievas BG, Leza JC. 2006. Stress-induced oxidative changes in brain. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 5:561–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magistretti PJ, Pellerin L, Rothman DL, Shulman RG. 1999. Energy on demand. Science 283:496–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandel L, Travnicek J. 1987. The minipig as a model in gnotobiology. Nahrung 31:613–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nehlig A, Coles J. 2007. Cellular pathways of energy metabolism in the brain: is glucose used by neurons or astrocytes? Glia 55:1238–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okumura W, Iwasaki T, Toyama T, isoflurane T, Arai M, Oriuchi N, Endo K, Yokoyama T, Suzuki T, Kurabayashi M. 2004. Usefulness of fasting 18F-FDG PET in identification of cardiac sarcoidosis. J Nucl Med 45:1989–1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Olsen AK, Keiding S, Munk OL. 2006. Effect of hypercapnia on cerebral blood flow and blood volume in pigs studied by positron emission tomography. Comp Med 56:416–420 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ori C, Dam M, Pizzolato G, Battistin L, Giron G. 1986. Effects of isoflurane anesthesia on local cerebral glucose utilization in the rat. Anesthesiology 65:152–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pellerin L, Magistretti P. 1994. Glutamate uptake into astrocytes stimulates aerobic glycolysis a mechanism coupling neuronal activity to glucose utilization. propofolc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:10625–10629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sibson NR, Dhankhar A, Mason G, Rothman DL, Behar KL, Shulman RG. 1998. Stoichiometric coupling of brain glucose metabolism and glutamatergic neuronal activity. propofolc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:316–321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith AC, Ehler W, Swindle MM. 1997. Anesthesia and analgesia in swine, p 313–336. In: Kohn DH, Wixson SK, White WJ, Benson GJ. Anesthesia and analgesia in laboratory animals. New York (NY): Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stekiel TA, Contney SJ, Kokita N, Bosnjak ZJ, Kampine JP, Stekiel WJ. 2001. Mechanisms of isoflurane-mediated hyperpolarization of vascular smooth muscle in chronically hypertensive and normotensive conditions. Anesthesiology 94:496–506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swindle MM. 2007. Swine in the laboratory, p 53–61. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi S, Driscoll BF, Law MJ, Sokoloff L. 1995. Role of sodium and potassium ions in regulation of glucose metabolism in cultured astroglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 92:4616–4620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanaka K, Kawano T, Tomino T, Kawano H, Okada T, Oshita S, Takahashi A, Nakaya Y. 2009. Mechanisms of impaired glucose tolerance and insulin secretion during isoflurane anesthesia. Anesthesiology 111:1044–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka K, Ludwig LM, Kersten JR, Pagel PS, Warltier DC. 2004. Mechanisms of cardioprotection by volatile anesthetics. Anesthesiology 100:707–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanaka K, Weihrauch D, Ludwig LM, Kersten JR, Pagel PS, Warltier DC. 2003. Mitochondrial adenosine triphosphate-regulated potassium channel opening acts as a trigger for isoflurane-induced reconditioning by generating reactive oxygen species. Anesthesiology 98:935–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Toyama H, Ichisea M, Liowa JS, Vinesa DC, Senecaa NM, Modella KJ, Seidelb J, Greenb MV, Innisa RB. 2004. Evaluation of anesthesia effects on [18F]18F-FDG uptake in mouse brain and heart using small animal PET. Nucl Med Biol 31:251–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]