Abstract

Pyrosequencing analysis of 16S rRNA genes was used to examine impacts of elevated CO2 (eCO2) on soil microbial communities from 12 replicates each from ambient CO2 (aCO2) and eCO2 settings. The results suggest that the soil microbial community composition and structure significantly altered under conditions of eCO2, which was closely associated with soil and plant properties.

TEXT

The concentration of atmospheric CO2 is increasing, largely due to human activities, and it is projected to reach 700 μmol/mol by the end of this century (15, 17). Although it is well established that elevated CO2 (eCO2) stimulates plant growth and primary productivity (2, 19, 23), the impact of eCO2 on soil microbial communities remains poorly understood (5, 7, 11–14, 18, 22, 28). Pyrosequencing of 16S rRNA genes has been used to analyze the diversity, composition, structure, and dynamics of microbial communities from different habitats, such as soil (1, 6, 10, 24, 25, 27), water (4, 21), fermented foods (16), and human gut (26). In this study, we aimed to (i) examine effects of eCO2 on the taxonomical diversity, composition, and structure of soil microbial communities and (ii) link soil and plant properties with the microbial community composition and structure by the use of tag-encoded pyrosequencing of 16S rRNA genes.

To address those issues, this study was conducted within the BioCON (Biodiversity, CO2, and Nitrogen) experiment site located at the Cedar Creek Ecosystem Science Reserve in Minnesota (23). For this study, 24 soil samples (12 from ambient CO2 [aCO2] settings, 12 from eCO2 settings, and all with 16 plant species and without an added nitrogen supply) were collected in July 2007. eCO2 plots have been treated since 1997 during the plant growing season (May to October) every year, and each sample was composited from five soil cores at a depth of 0 to 15 cm. Details are provided in Materials and Methods in the supplemental material.

The V4 and V5 regions of 16S rRNA genes were amplified using a conserved primer pair with a unique 6-mer oligonucleotide sequence (barcode) at the 5′ end for each sample (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). After preprocessing of all reads, 30,008 and 29,091 high-quality sequences were obtained for aCO2 and eCO2 samples, respectively. The numbers of sequences from different samples ranged from 1,854 to 3,087 for aCO2 samples and from 1,698 to 3,299 for eCO2 samples (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). All sequences were aligned using the RDP Infernal Aligner, and the complete linkage clustering method was used to define operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using 97% identity as a cutoff, resulting in 2,527 and 2,354 OTUs for aCO2 and eCO2, respectively (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The average Shannon indices were 6.58 and 6.51 for aCO2 and eCO2 samples, respectively (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). However, no significant (P > 0.05) differences were seen in the numbers of sequences, OTUs, or Shannon diversity index between aCO2 and eCO2 samples. In total, 3,500 OTUs were detected for at least 2 of 12 aCO2 or eCO2 samples, phylogenetically deriving from one known archaeal phylum and 16 known bacterial phyla as well as unclassified phylotypes. Most phylotypes were detected at both aCO2 and eCO2, with only a few detected at only aCO2 or eCO2 (see Table S3 and Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). At the phylum level, 811 (23.2%) OTUs were derived from Proteobacteria, a phylum with the highest number of detectable OTUs, followed by Actinobacteria (596; 17.0%), Bacteroidetes (448; 12.8%), and Acidobacteria (369; 10.5%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Numbers of OTUs detected under aCO2 and eCO2 conditions

| Domain and phylum | No. of OTUs |

P (unpaired t test) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Totala (%) | Avgb |

|||

| aCO2 | eCO2 | |||

| Archaea | ||||

| Crenarchaeota | 10 (0.28) | 4.42 ± 1.73 | 3.17 ± 1.59 | 0.08 |

| Unclassified | 1 (0.03) | |||

| Bacteria | ||||

| Acidobacteria | 369 (10.50) | 112.33 ± 20.08 | 91.08 ± 19.11 | 0.01 |

| Actinobacteria | 596 (17.00) | 179.83 ± 26.18 | 179.25 ± 25.52 | 0.96 |

| Bacteroidetes | 448 (12.80) | 105.58 ± 24.54 | 100.17 ± 21.07 | 0.57 |

| BRC1 | 2 (0.57) | 0.17 ± 0.39 | 0.25 ± 0.45 | 0.63 |

| Chlamydiae | 36 (1.03) | 3.08 ± 2.39 | 3.92 ± 3.00 | 0.46 |

| Chloroflexi | 94 (2.69) | 17.33 ± 4.23 | 14.92 ± 6.04 | 0.27 |

| Cyanobacteria | 3 (0.86) | 0.75 ± 0.87 | 0.17 ± 0.39 | 0.04 |

| Firmicutes | 118 (3.4) | 28.58 ± 5.65 | 24.33 ± 5.99 | 0.09 |

| Gemmatimonadetes | 86 (2.46) | 22.83 ± 5.81 | 17.92 ± 5.52 | 0.05 |

| Nitrospirae | 6 (0.17) | 3.00 ± 1.48 | 2.00 ± 1.04 | 0.07 |

| OP10 | 8 (0.23) | 1.42 ± 1.51 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Planctomycetes | 251 (7.17) | 42.00 ± 8.82 | 39.67 ± 12.37 | 0.60 |

| Proteobacteria | 811 (23.2) | 207.08 ± 30.79 | 220.33 ± 30.22 | 0.30 |

| TM7 | 52 (1.49) | 7.83 ± 3.79 | 6.25 ± 4.11 | 0.34 |

| Verrucomicrobia | 127 (3.63) | 29.33 ± 8.32 | 22.92 ± 8.01 | 0.07 |

| WS3 | 6 (0.17) | 1.00 ± 0.74 | 0.83 ± 1.19 | 0.68 |

| Unclassified | 454 (13.00) | |||

| Total unclassified | 22 (0.63) | |||

| Total | 3,500 (100) | 846.75 ± 108.71 | 800.5 ± 122.03 | 0.34 |

Data represent total numbers of OTUs detected by pyrosequencing across all 24 samples.

Data represent average numbers of OTUs detected using 12 samples under aCO2 or eCO2 conditions.

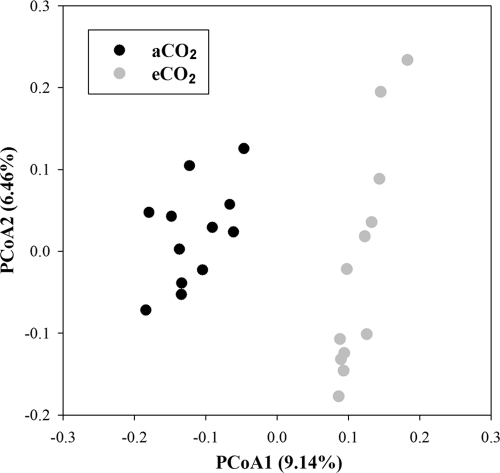

To examine whether eCO2 affects the taxonomical composition and structure of soil microbial communities, principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) was performed with the relative abundance values of 454 pyrosequencing data. Two distinct clusters were formed, and aCO2 samples were well separated from eCO2 samples (Fig. 1). The results of three nonparametric multivariate statistical tests, ANOSIM (8), Adonis (3), and MRPP (20), showed significant differences (P = 0.001 and δ = 0.481, P = 0.003 and R = 0.209, and P = 0.001 and R2 = 0.082, respectively) based on the abundance of all OTUs detected at aCO2 and eCO2, and such significances (P < 0.05) were also observed at the phylum level, including Acidobacteria, Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, DP10, Proteobacteria, TM7, and WS3 (see Table S4 in the supplemental material). The results indicated that the overall taxonomic composition and structure of soil microbial communities shifted in response to eCO2.

Fig 1.

Principal coordination analysis (PCoA) of soil microbial community structure based on the relative abundances of OTUs detected by 454 pyrosequencing.

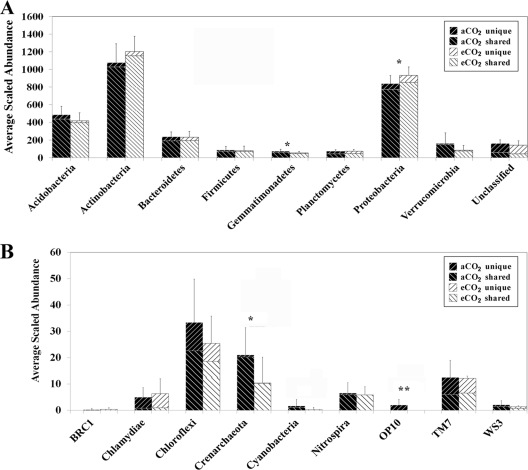

To further examine effects of eCO2 on microbial communities, we analyzed both significantly changed and unique OTUs. Among 3,500 OTUs detected, 1,381 were shared by aCO2 and eCO2 samples, and 1,146 and 973 unique OTUs were detected at aCO2 and eCO2, respectively. For those shared OTUs, 27 were significantly (P < 0.05) decreased and 36 were significantly (P < 0.05) increased at eCO2 (see Table S5 in the supplemental material). For example, 26 significantly changed OTUs were found in Actinobacteria, with 7 decreased and 19 increased at eCO2 (see Table S5 and Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Also, 11 OTUs were significantly (P < 0.05) changed at eCO2, with 9 increased and 2 decreased in Proteobacteria, and 5, 3, 2, and 1 OTUs were derived from Alpha-, Beta-, Delta-, and Gammaproteobacteria, respectively (Fig. 2; see also Table S5 in the supplemental material). In addition, significantly (P < 0.05) changed OTUs in other phyla, such as Acidobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Planctomycetes, were observed (Fig. 2; see also Table S5 in the supplemental material). A large percentage (60.5%) of unique OTUs was detected by pyrosequencing, with 1,146 (32.7%) at aCO2 and 973 (27.8%) at eCO2, and those OTUs were largely derived from the most abundant phyla (see Table S5 in the supplemental material). For example, 213 and 243 unique OTUs were detected at aCO2 and eCO2, respectively, for Proteobacteria, and 170 and 150 for Actinobacteria. The analysis of significantly changed and unique OTUs confirmed that the taxonomic composition and structure of soil microbial communities significantly changed at eCO2.

Fig 2.

Averages of scaled relative abundances of detected OTUs at the phylum level for both aCO2 and eCO2 samples. Data are presented as means ± standard errors, with 12 samples for each CO2 condition. Generally, each bar has two portions: the top part is for unique OTUs detected only at aCO2 or eCO2 and the bottom part for shared OTUs detected under both aCO2 and eCO2 conditions. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

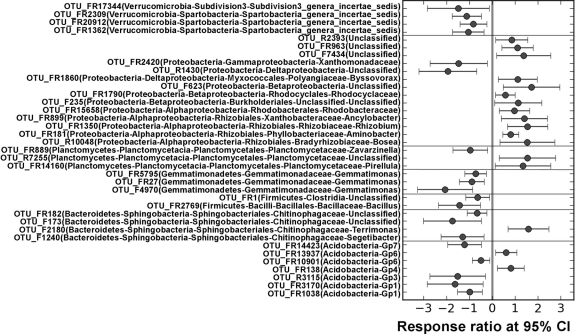

To understand whether microbial populations differentially respond to eCO2, detected OTUs were mapped to their associated populations at the phylum or lower levels. Based on relative abundances of all OTUs in a given phylotype with at least six OTUs detected, significantly changed populations were identified by response ratio (19). At the phylum level, four phyla, including one archaeal phylum (Crenarchaeota) and three bacterial phyla (Proteobacteria, Gemmatimonadetes, and DP10), showed significant (P < 0.05) changes in their relative abundances, but other phyla, including Actinobacteria, the most abundant phylum, did not show significant changes in relative abundances at eCO2 (Fig. 3). A further examination of those significantly changed phyla showed that those changes occurred in some specific microbial populations at the class or lower levels. In Proteobacteria, the relative abundances of some orders, such as Caulobacterales of Alphaproteobacteria, Myxococcales of Deltaproteobacteria, and Xanthomonadales of Gammaproteobacteria, significantly (P < 0.05) increased at eCO2 (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Also, although significant changes were not seen at eCO2 for the most abundant phyla at the phylum level, such significances were detected at class or lower taxonomic levels. For example, in Acidobacteria, significant (P < 0.05) changes were observed in the relative abundances in the classes of Gp1, Gp2, and Gp3 but not in other classes (see Fig. S4A in the supplemental material); in Verrucomicrobia, all significant (P < 0.05) changes appeared to be decreased in Spartobacteria but not in other classes (see Fig. S4B in the supplemental material); in Firmicutes, the relative abundances of unclassified phylotypes were significantly (P < 0.05) decreased (see Fig. S4C in the supplemental material). These results indicated that eCO2 might differentially affect some specific microbial populations at different taxonomic levels such as phylum, class, and order, with decreased or increased relative abundances at eCO2. Recently, a study using a comprehensive functional gene array, GeoChip 3.0 (12), demonstrated that the functional composition and structure of soil microbial communities were significantly altered at eCO2 in BioCON, which may have been due to eCO2-induced shifts in microbial populations. However, the linkage between taxonomical populations and their functions of soil microbial communities needs further investigations.

Fig 3.

Significantly changed OTUs in the phyla of Acidobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Gemmatimonadetes, Planctomycetes, Proteobacteria, Verrucomicrobia, and unclassified phylotypes at elevated CO2 determined using the response ratio method at a 95% confidence interval.

To link the microbial community structure with soil and plant properties, Mantel tests were performed. First, using the BioENV procedure (9), four plant variables, including the belowground carbon percentage (BPC), aboveground carbon percentage (APC), aboveground total biomass (ATB) and total biomass (TB), and four soil variables, including the proportion of soil moisture at the depth of 0 to 17 cm (PSM0–17), the percentage of C at the depth of 0 to 10 cm (C0–10), the percentage of N at the depth of 0 to 10 cm (N0–10), and net N mineralization, were selected for partial Mantel tests (see Table S6 in the supplemental material). Second, partial Mantel tests were performed to correlate the microbial community measured by the relative abundances of all detected 3,500 OTUs with the selected sets of plant and soil variables described above. Although the microbial community was not significantly (P > 0.05) correlated with plant variables or soil variables (see Table S6 in the supplemental material) at the community level, significant correlations were observed with specific microbial populations at different taxonomic levels (phylum, class, order, family, and genus). At the phylum level, five phyla (Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, Chlamydiae, Gemmatimonadetes, and Nitrospirae) were significantly (P < 0.05) correlated with the selected plant properties (see Table S6 in the supplemental material). At the class level, nine classes were significantly (P < 0.05) correlated with soil or plant characteristics. Bacilli, Clostridia, Alphaproteobacteria, Chlamydiae, Nitrospirae, and an unclassified phylotype from the TM7 phylum were significantly (P < 0.05) correlated with the selected plant variables, subdivision 3 of Verrucomicrobiae (P = 0.05) with soil variables, and Gammaproteobacteria (P < 0.05) with both soil and plant variables (Table 2). Similarly, significant (P < 0.05) correlations between the microbial community and the selected plant and/or soil properties were detected in 12 orders (see Table S7 in the supplemental material), 23 families (see Table S8 in the supplemental material), and 48 genera (see Table S9 in the supplemental material). In addition, many unclassified phylotypes were significantly (P < 0.05) correlated with the selected soil or/and plant variables, suggesting that soil and plant factors may also shape taxonomically uncharacterized microbial communities (Table 2; see also Table S6, S7, S8, and S9 in the supplemental material). The results presented above suggest that the variables selected greatly influenced the taxonomic composition and structure of microbial communities in this grassland ecosystem.

Table 2.

Partial Mantel analysis of the relationship between the relative abundance of class and soil or plant propertiesa

| Phylum | Class | Soil,b partial plantc |

Plant,c partial soilb |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | r | P | ||

| All detected OTUs | −0.018 | 0.508 | 0.266 | 0.065 | |

| Firmicutes | Bacilli | 0.184 | 0.118 | 0.379 | 0.020 |

| Clostridia | 0.040 | 0.380 | 0.316 | 0.014 | |

| Proteobacteria | Alphaproteobacteria | 0.137 | 0.139 | 0.300 | 0.012 |

| Betaproteobacteria | 0.220 | 0.077 | 0.470 | 0.003 | |

| Gammaproteobacteria | 0.317 | 0.023 | 0.353 | 0.021 | |

| TM7 | Unclassified | −0.065 | 0.621 | 0.415 | 0.010 |

| Chlamydiae | Chlamydiae | 0.192 | 0.157 | 0.356 | 0.026 |

| Nitrospira | Nitrospira | −0.033 | 0.520 | 0.404 | 0.013 |

| Verrucomicrobia | Subdivision 3 | 0.289 | 0.049 | −0.193 | 0.922 |

Only significantly (P < 0.05) changed phytotypes are shown.

Selected soil variables included proportion soil moisture at the depth of 0 to 17 cm (PSM0 to–17), percent C at the depth of 0 to 10 cm (C0–10), percent N at the depth of 0 to 10 cm (N0–10), and net N mineralization.

Selected plant variables included below ground carbon percent (BPC), above ground carbon percent (APC), aboveground total biomass (ATB), and total biomass (TB).

In summary, this study used pyrosequencing technologies to examine the taxonomical diversity, composition, and structure of soil microbial communities in a grassland ecosystem and their responses to eCO2. The microbial community composition and structure significantly shifted at eCO2, potentially due to differential responses of specific microbial populations to eCO2. Plant and soil properties, such as plant biomass, soil moisture, and soil C and N contents, may greatly shape the microbial community composition and structure and regulate ecosystem functioning in this grassland.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (project 2007-35319-18305) through the NSF-USDA Microbial Observatories Program, by the Department of Energy under contract DE-SC0004601 through Genomics: GTL Foundational Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Science Foundation under grants DEB-0716587 and DEB-0620652 as well as grants DEB-0322057, DEB-0080382 (the Cedar Creek Long Term Ecological Research project), DEB-0218039, DEB-0219104, DEB-0217631, and DEB-0716587 (BioComplexity), LTER and LTREB projects, the DOE Program for Ecosystem Research, and the Minnesota Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund.

We also acknowledge members of the Oklahoma University's Advanced Center for Genome Technology, in particular Chunmei Qu and Yanbo Xing, for sample manipulations for the 454/Roche GS-FLX Titanium pyrosequencing.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 February 2012

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Acosta-Martinez V, Dowd S, Sun Y, Allen V. 2008. Tag-encoded pyrosequencing analysis of bacterial diversity in a single soil type as affected by management and land use. Soil Biol. Biochem. 40:2762–2770 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ainsworth EA, Long SP. 2005. What have we learned from 15 years of free-air CO2 enrichment (FACE)? A meta-analytic review of the responses of photosynthesis, canopy properties and plant production to rising CO2. New Phytol. 165:351–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Anderson MJ. 2001. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austr. Ecol. 26:32–46 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Andersson AF, Riemann L, Bertilsson S. 2010. Pyrosequencing reveals contrasting seasonal dynamics of taxa within Baltic Sea bacterioplankton communities. ISME J. 4:171–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Austin EE, Castro HF, Sides KE, Schadt CW, Classen AT. 2009. Assessment of 10 years of CO2 fumigation on soil microbial communities and function in a sweetgum plantation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 41:514–520 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Campbell BJ, Polson SW, Hanson TE, Mack MC, Schuur EAG. 2010. The effect of nutrient deposition on bacterial communities in Arctic tundra soil. Environ. Microbiol. 12:1842–1854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Carney MC, Hungate BA, Drake BG, Megonigal JP. 2007. Altered soil microbial community at elevated CO2 leads to loss of soil carbon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:4990–4995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clarke KR. 1993. Non-parametric multivariate analyses of changes in community structure. Aust. J. Ecol. 18:117–143 [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clarke KR, Ainsworth M. 1993. A method of linking multivariate community structure to environmental variables. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 92:205–219 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eilers KG, Lauber CL, Knight R, Fierer N. 2010. Shifts in bacterial community structure associated with inputs of low molecular weight carbon compounds to soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42:896–903 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gruber N, Galloway JN. 2008. An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature 451:293–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. He Z, et al. 2010. Metagenomic analysis reveals a marked divergence in the structure of belowground microbial communities at elevated CO2. Ecol. Lett. 13:564–575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heath J, et al. 2005. Rising atmospheric CO2 reduces sequestration of root-derived soil carbon. Science 309:1711–1713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heimann M, Reichstein M. 2008. Terrestrial ecosystem carbon dynamics and climate feedbacks. Nature 451:289–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Houghton JT, et al. 2001. Climate change 2001: the scientific basis. Contribution of working group I to the third assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 16. Humblot C, Guyot J-P. 2009. Pyrosequencing of tagged 16S rRNA gene amplicons for rapid deciphering of the microbiomes of fermented foods such as pearl millet slurries. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:4354–4361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 2007. Climate change 2007: the physical science basis. Contribution of working group I to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lesaulnier C, et al. 2008. Elevated atmospheric CO2 affects soil microbial diversity associated with trembling aspen. Environ. Microbiol. 10:926–941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Luo YQ, Hui DF, Zhang DQ. 2006. Elevated CO2 stimulates net accumulations of carbon and nitrogen in land ecosystems: a meta-analysis. Ecology 87:53–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mielke PW, Berry KJ, Brockwell PJ, Williams JS. 1981. A class of nonparametric tests based on multiresponse permutation procedures. Biometrika 68:720–724 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miller SR, Strong AL, Jones KL, Ungerer MC. 2009. Bar-coded pyrosequencing reveals shared bacterial community properties along the temperature gradients of two alkaline hot springs in Yellowstone National Park. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:4565–4572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parmesan C, Yohe G. 2003. A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature 421:37–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reich PB, et al. 2001. Plant diversity enhances ecosystem responses to elevated CO2 and nitrogen deposition. Nature 410:809–812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roesch LF, et al. 2007. Pyrosequencing enumerates and contrasts soil microbial diversity. ISME J. 1:283–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schütte UM, et al. 2010. Bacterial diversity in a glacier foreland of the high Arctic. Mol. Ecol. 19:54–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Turnbaugh PJ, et al. 2009. A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 457:480–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Uroz S, Buée M, Murat C, Frey-Klett P, Martin F. 2010. Pyrosequencing reveals a contrasted bacterial diversity between oak rhizosphere and surrounding soil. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2:281–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Walther G-R, et al. 2002. Ecological responses to recent climate change. Nature 416:389–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.