Abstract

Background

The catecholamine release-inhibitor catestatin and its precursor chromogranin A (CHGA) may constitute “intermediate phenotypes” in analysis of genetic risk for cardiovascular disease such as hypertension. Previously, the vacuolar H+-ATPase subunit gene ATP6V0A1 was found within the confidence interval for linkage with catestatin secretion in a genome-wide study, and its 3′-UTR polymorphism T+3246C (rs938671) was associated with both catestatin processing from CHGA, as well as population blood pressure (BP). Here we explored the molecular mechanism of this effect by experiments with transfected chimeric photoproteins in chromaffin cells.

Methods and Results

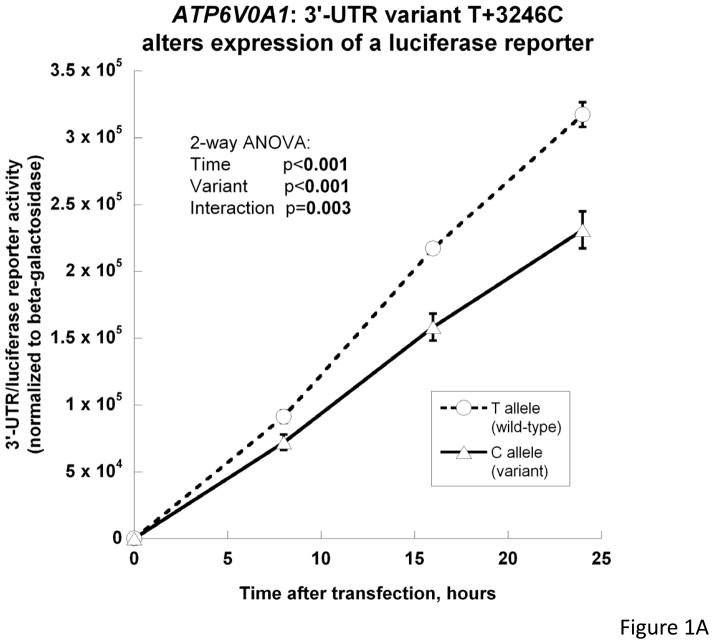

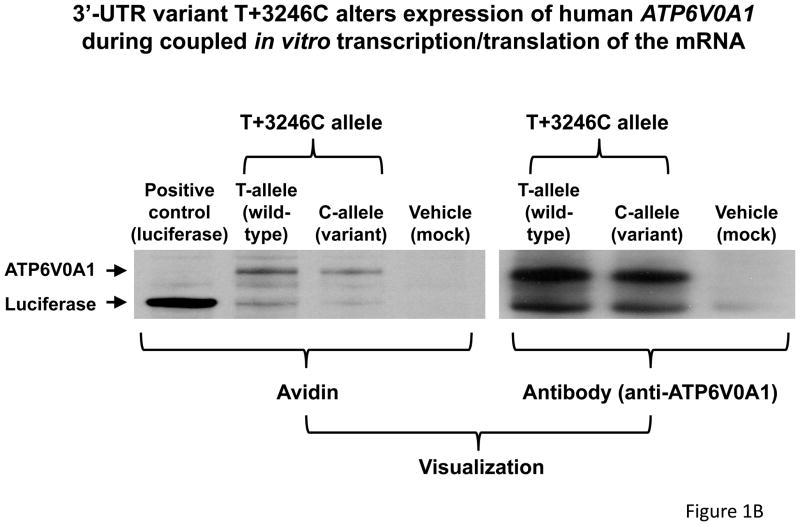

Placing the ATP6V0A1 3′-UTR downstream of a luciferase reporter, we found that the C (variant) allele decreased overall gene expression. The 3′-UTR effect was verified by coupled in vitro transcription/translation of the entire/intact human ATP6V0A1 mRNA. Chromaffin granule pH, monitored by fluorescence a CHGA/EGFP chimera during vesicular H+-ATPase inhibition by bafilomycin A1, was more easily perturbed during co-expression of the ATP6V0A1 3′-UTR C-allele than the T-allele. After bafilomycin A1 treatment, the ratio of CHGA precursor to its catestatin fragments in PC12 cells was substantially diminished, though the qualitative composition of such fragments was not affected (on immunoblot or MALDI mass spectrometry). Bafilomycin A1 treatment also decreased exocytotic secretion from the regulated pathway, monitored by a CHGA chimera tagged with embryonic alkaline phosphatase (EAP). 3′-UTR T+3246C created a binding motif for micro-RNA hsa-miR-637; co-transfection of hsa-miR-637 precursor or antagomir/inhibitor oligonucleotides yielded the predicted changes in expression of luciferase reporter/ATP6V0A1-3′-UTR plasmids varying at T+3246C.

Conclusions

The results suggest a series of events whereby ATP6V0A1 3′-UTR variant T+3246C functioned: ATP6V0A1 expression was affected likely through differential micro-RNA effects, altering vacuolar pH and consequently CHGA processing and exocytotic secretion.

Keywords: chromaffin, catecholamine, adrenal, hypertension, vacuolar pH

Introduction

Chromogranin A (CHGA), a member of the chromogranin/secretogranin family of neuroendocrine secretory proteins, is the precursor to several bioactive peptides including the catecholamine release-inhibitory catestatin (human CHGA352–372) 1, 2. Catestatin secretion may be an “intermediate phenotype” in analysis of genetic risk for cardiovascular disease 3, since it is diminished not only in hypertensive individuals but also in the still-normotensive offspring of patients with hypertension 4, and replacement of catestatin can “rescue” the severe hypertension observed in mice with targeted ablation of the Chga gene 5. The plasma ratio of CHGA/catestatin (precursor/product) was significantly higher in a hypertensive population, suggesting an impairment of CHGA processing in this disorder 6.

Previously, we studied catestatin secretion in a large series of twin and sibling pairs from North America and Australia, enabling estimation of its heritability, genome-wide linkage (positional cloning), and marker-on-trait association 6. We found that the ATP6V0A1 gene (ATP6N1, ATP6N1A, VPP1; OMIM #192130; human chromosome 17q21) was a positional candidate locus within the confidence interval for catestatin linkage. Furthermore, allelic variation at ATP6V0A1 (3′-UTR SNP T+3246C; rs938671, MAF 9–13%) is associated with catestatin concentration, the CHGA/catestatin ratio, as well as basal BP in the population 6.

ATP6V0A1 (NC_000017), initially isolated in 1995 7, encodes the α1 subunit of the vacuolar (V) H+-translocating ATPase heteromultimeric complex which mediates acidification of eukaryotic intracellular organelles; the α1 subunit is a 116 kDa integral membrane protein which participates directly in H+ translocation. The pH of organelles along the secretory pathway decreases progressively from the endoplasmic reticulum to the secretory granule 8–11, and chemical (bafilomycin A1) inhibition of the vacuolar H+-ATPase impairs chromaffin granule formation, as well as catecholamine storage and secretory protein trafficking into the regulated pathway 12.

In this study, we therefore aim to explore the molecular mechanism whereby ATP6V0A1 T+3246C influences CHGA and catestatin concentrations and their ratio. It was plausible to hypothesize that changes in control of vacuolar pH would influence such traits, through the effect of secretory pathway pH to modulate either precursor proteolytic processing or exocytotic secretion 13. Using transfected chimeric photoprotein reporters in chromaffin cells, our results reveal that ATP6V0A1 3′-UTR variant T+3246C alters gene expression through differential binding to a particular micro-RNA, thereby altering vacuolar pH, and consequently the processing of CHGA to catestatin.

Methods

Construction of human expression plasmids

See Supplemental Methods.

Cell culture and transfection

See Supplemental Methods.

Luciferase reporter activity assay

After transfection and cell growth over an 8- to 24-hour time course, cells were lysed with Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega) for sequential measurement of luciferase enzymatic activity and total protein concentration. Luciferase enzymatic activity was measured using the Luciferase Assay System (Promega) on a Luminometer Autolumat 953 (EG&G Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany). Total protein concentration was measured using a dye-binding protein assay (Bio-Rad) on a SmartSpec™ Plus spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad). Results were expressed as the ratio of luciferase activity/protein concentration to normalize luciferase activity.

In vitro transcription/translation of human ATP6V0A1

SP6-promoter-driven full-length human ATP6V0A1 cDNA (including the 3′-UTR in two versions, T+3246C) was in vitro transcribed/translated by TNT® Quick Coupled Transcription/Translation System (Promega L5080), using a rabbit reticulocyte lysate. Newly synthesized proteins were labeled by incorporation of biotinylated-lysine, and then detected by chemiluminescence with streptavidin-HRP in a Transcend™ Non-Radioactive Translation Detection System (Promega).

Measurement of intravacuolar (catecholamine storage vesicle) pH

We previously described the use of transfected/expressed human CHGA/EGFP chimeras, and their trafficking to chromaffin granules (12), as well as the use of an SCG2/EGFP chimera to monitor pH within chromaffin granules (12). Here we used a CHGA/EGFP chimera to monitor pH changes within living PC12 cells, during co-expression of human ATP6V0A1 with alternative 3′-UTR alleles. PC12 cells grown on poly-L-lysine- and collagen-coated 25-mm round glass coverslips (Warner Instruments) were transfected with pCMV-CHGA-EGFP and transferred into a perfusion chamber (Quick Exchange, Warner Instruments). Monitoring of single cell fluorescence was achieved with an ImageMaster IM-2103-6-HQ imaging system (Photon Technology International). Correlation between GFP fluorescence and pH value was obtained in situ by incubating the cells for 3 min in KCl-rich media buffered to pH values ranging from 4.5 to 8.5 (at a 0.5 pH unit interval). In cells co-transfected with CHGA/EGFP and full-length ATP6V0A1 (with 3′-UTR), pH was followed using GFP fluorescence, at baseline and after bafilomycin was added to a 100 nM final concentration. A detailed protocol was described previously 14.

Chemiluminescence detection of secretory protein/EAP chimera secretion by chromaffin cells

Detection of EAP enzymatic activity release from CHGA-EAP chimera-expressing PC12 cells was achieved using the chemiluminescent substrate 3-(4-methoxyspiro[1,2-dioxetane-3,2′-(5′chloro)tricyclo[3.3.1.1(3,7)]decan]-4-yl) phenyl phosphate (CSPD) (Phospha-Light, Applied Biosystems, Foster city, California) on a Luminometer Autolumat 953 (EG&G Berthold). EAP activities are measured in the culture supernatant and the cell lysate. Exocytotic secretion of the transfected/expressed EAP chimeras was provoked by the potent regulated pathway stimulus Ba2+ (2 mM) which acts by blocking efflux of cellular K+ and hence cell membrane repolarization 15. A detailed protocol was described previously 15. The secretion rate is calculated as supernatant EAP activity as a % of total enzymatic activity (cell plus supernate). The “sorting index” is calculated as a function of increase in secretion rate after stimulation of the regulated exocytotic pathway by Ba2+: (stimulated – basal)/basal.

Immunoblot analysis

Proteins from PC12 cell lysates were separated in a 10% SDS-PAGE (Novex precast gel; Invitrogen) gel and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Protran, BA85; Whatman Inc., Florham Park, New Jersey). The membrane was blocked with 5% (wt/vol) powdered/dry milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween-20. After incubation with primary antibody (rabbit anti-rat catestatin), the membrane was washed and incubated with secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit). The membrane was then developed by the Supersignal west pico-chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, Illinois). Anti-actin was used as internal control. Immunoreactive band quantification was done on the software Quantity One (Bio-Rad).

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

PC12 cells were treated with vehicle (DMSO) or bafilomycin A1 (100 nM; from Streptomyces griseus; Sigma B1793), which is a specific inhibitor of the V-ATPase 16, and was shown to inhibit vacuolar acidification 17 as well as dense core granule formation and secretory protein trafficking 12 effectively. After exposure for 22 hours, cells were lysed, pre-cleared with normal rabbit serum, and then subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-rat catestatin antibody. Antigen-antibody complex were then isolated using protein G plus/protein A agarose; the complexes were washed several times, and the bound peptides were eluted with acetonitrile/water/TFA. Eluted peptides were concentrated by lyophilization and subjected to MALDI-TOF analysis: reflectron mode to scan the 1,000–2,100 Da range, and linear mode to scan the 2,000–25,000 Da range, on a Voyager De™STR MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems) at a proteomics core facility <http://massspec.ucsd.edu/bioms/>. Resulting peptide masses were analyzed in the program Protein Prospector <http://prospector.ucsf.edu/> to identify the fragments of rat Chga.

Evaluation of micro-RNA function

Computational

Inter-species sequence alignments were done by Clustal-W. 3′-UTR miRNA motifs were predicted at RegRNA <http://regrna.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/>. Effect of the variant on RNA hybrid structures and predicted minimum folding energies was analyzed using BiBiServ <http://bibiserv.techfak.uni-bielefeld.de/rnahybrid/submission.html>.

Experimental

Strategies of both over-expression and knockdown were adopted to explore miRNA function in cella. For over-expression, Ambion (Austin, Texas) Pre-miR™ 24-mer specific precursor for miRNA hsa-miR-637 (PM11545) was used to increase that miRNA signal, and a pre-designed negative control precursor (#1; AM17110) was used to minimize off-target effects. For knockdown, an Exiqon (Vedbaek, Denmark) miRCURY LNA™ (“locked”, stabilized nucleic acid) 18-mer inhibitor for the specific miRNA hsa-miR-637 (412259-00) was used in an attempt to decrease the signal from that miRNA, and a pre-designed 22-mer negative control inhibitor (“Scramble-miR”; Exiqon 199002-00) was used in the control group. The identity of each synthetic oligonucleotide was verified by mass spectrometry.

Statistics

Values are given as the mean ± SEM. Numbers of experimental replicates are given in the Figure legends. Data shown are representative of typical experiments. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS-17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) by t test, or two-way ANOVA, as appropriate, after inspection of the data distribution. Differences were considered significant when p<0.05.

Results

ATP6V0A1 3′-UTR variant T+3246C influences gene expression

Evidence from isolated 3′-UTR segments on transfected 3′-UTR/luciferase reporter plasmids

Wild-type (T+3246) versus variant (+3246C) 1458 bp ATP6V0A1 3′-UTRs were ligated into the reporter plasmid pGL3-Promoter, downstream of the luciferase reporter gene (supplemental Figure 1). After transfection into PC12 cells, cellular luciferase activity was measured. The two 3′-UTR allelic plasmids gave rise to significantly different reporter activities, with wild-type > variant (i.e., T > C), and progressively greater differences in expression as a function of increasing time after transfection (p=0.003) (Figure 1A). The T > C pattern of expression was not dependent on the exact promoter driving transcription, since T > C differential expression remained when the promoter was changed from SV40 to CMV (new normalized luciferase activity: 6.52±0.25E+6 for T/wild-type versus 5.01±0.19E+6 for C/variant; p=8.64E-4 between wild-type/T and variant/C alleles).

Figure 1.

ATP6V0A1 3′-UTR variant T+3246C (rs938671) influences gene expression. In each case, results are plotted as the mean value ± SEM. A. Luciferase reporter/3′-UTR variant transfection into PC12 cells (n=4 per group at each time point). Transcription is driven by the SV40 early promoter. The structure of the reporter plasmid is given in supplemental Figure 1. B. In vitro transcription/translation of full-length human ATP6V0A1 cDNA. Full-length cDNAs for human ATP6V0A1 (including 3′-UTR in two versions: T+3246C) were subcloned into a plasmid with the prokaryotic SP6 promoter. SP6-luciferase was used as positive control, while vehicle (H2O) was used as negative control. Using a Transcend™ non-radioactive translation detection system (left panel), proteins synthesized in a rabbit reticulocyte lysate were labeled with biotinylated lysine, and then detected by streptavidin-HRP chemiluminescence. Using the immunoblot technique (right panel), ATP6V0A1 was detected by a rabbit polyclonal antibody (sc-28801, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA). Both strategies showed higher expression of ATP6V0A1 from wild-type (T-allele) than variant (C-allele) 3′-UTRs.

Evidence from coupled in vitro transcription/translation of the full-length ATP6V0A1 cDNA

Wild-type (T+3246) or variant (+3246C) ATP6V0A1 cDNAs driven by an SP6 promoter were expressed in rabbit reticulocytes in vitro. The wild-type (T-allele) cDNA exhibited greater expression than the variant (C-allele), when visualized by either the avidin/biotin method or specific anti-ATP6V0A1 immunoblotting (Figure 1B).

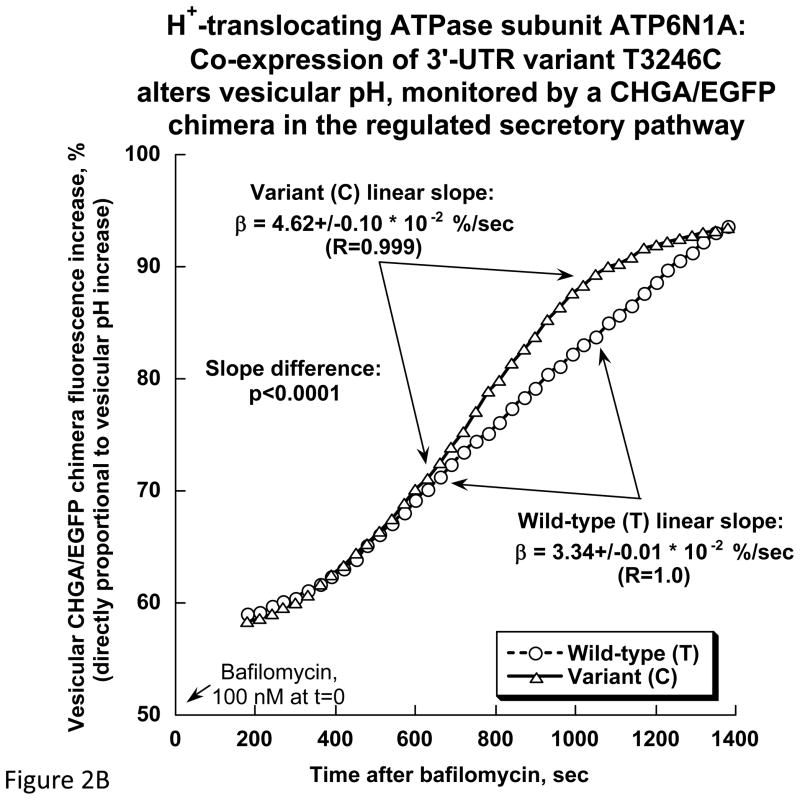

ATP6V0A1 T+3246C and chromaffin granule pH

First we used the fluorescence of transfected/expressed human CHGA/EGFP to calibrate pH within PC12 chromaffin granules, in which we confirmed its subcellular localization (in a punctate sub-plasmalemmal distribution characteristic of chromaffin granules), and estimated basal/resting granular pH at 5.8±0.3 (Figure 2A). We then co-transfected/expressed full-length human ATP6V0A1 cDNA in two 3′-UTR allelic versions (T+3246C). When granular pH was perturbed (alkalinized) by Bafilomycin A1 (100 nM), the acute rate of rise in pH was greater (p<0.0001) for the C-allele (4.62±0.10 * 10−2 %/sec) than the T-allele (3.34±0.01 * 10−2 %/sec).

Figure 2.

Chromaffin granule pH (pHves) in PC12 cells: Estimation by fluorescence intensity of a transfected/expressed human CHGA/EGFP chimera, and effects of ATP6V0A1. A. CHGA/EGFP fluorescence as a function of pH. PC12 cells expressing CHGA/EGFP were subjected to pH calibration as described in Methods. The cells display punctate fluorescence in a subplasmalemmal distribution typical of chromaffin granules, as well as a proportional log/linear relationship between fluorescence intensity and pH, over the range pH=5.0~8.0 (n=10 determinations at each calibration pH). The resting/basal intragranular pH (pHves) was estimated by interpolation at pH=5.8±0.3. B. ATP6V0A1 and chromaffin granule pH. CHGA/EGFP was co-transfected/co-expressed with the full-length ATP6V0A1 cDNA (3′-UTR T+3246C alleles) to monitor pHves using fluorescence intensity, as described in Methods and in panel 2A. Fluorescence was monitored every 30 sec over a 25-min period after exposure to bafilomycin (100 nM), with n=6 replicates per allele group.

Disruption of secretory granule core acidification alters trafficking of CHGA into the regulated secretory pathway, as well as CHGA proteolytic processing

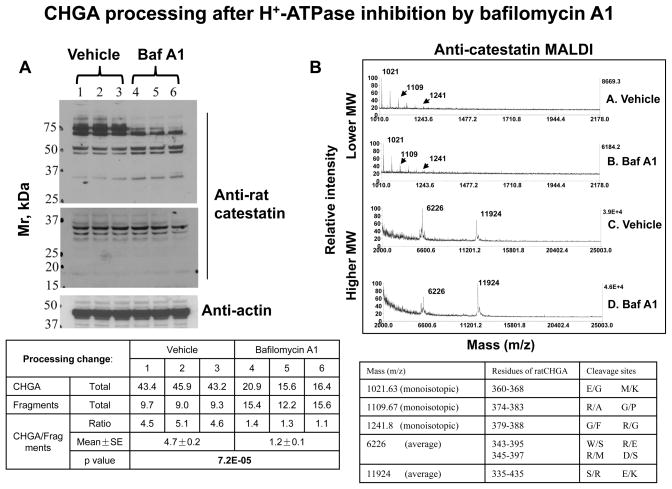

Proteolytic processing: Bafilomycin A1 alters CHGA processing in chromaffin cells

To determine whether vacuolar pH influences CHGA processing, we used immunoblots and MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry to probe the effects of V-ATPase inhibition with 22 h exposure to bafilomycin A1 (100 nM). Anti-catestatin immunoblots on PC12 lysates visualized fragments from ~20 to 75 kDa (Figure 3A), while MALDI-TOF probed derivatives from ~1 to 25 kDa (Figure 3B). No qualitative fragment changes (creation or abolition) were found between bafilomycin A1 and vehicle. However, quantification of immunoblots suggested substantially reduced CHGA (~75 kDa) coupled with similar or increased amounts of immunoreactive fragments after exposure to bafilomycin A1. Thus, the ratio of CHGA/fragments was significantly (p=7.2E-05) decreased.

Figure 3.

CHGA proteolytic processing to fragments during inhibition of the vacuolar pH gradient in chromaffin cells. A. Immunoblot after SDS-PAGE. Rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells (n=3 replicate cultures) were treated with bafilomycin A1 (100 nM) or vehicle (DMSO) for 22 hours, then lysed, subjected to SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotted with anti-rat catestatin antibody (top and middle panels). The upper panel (Mr 25–75 kDa) was exposed for 30 sec. The middle panel (Mr 15–37 kDa) shows a darker exposure (45 min) of the lower part of the same immunoblot. A parallel blot was stained with anti-actin antibody (bottom panel), to indicate comparable protein load/lane. B. Mass spectrometry. Cell lysates from the vehicle and bafilomycin A1 treated cells were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-rat catestatin antibody followed by MALDI-TOF analysis. Calculated mass (M/Z) values for fragments of the parent molecule (rat Chga) are listed in the table.

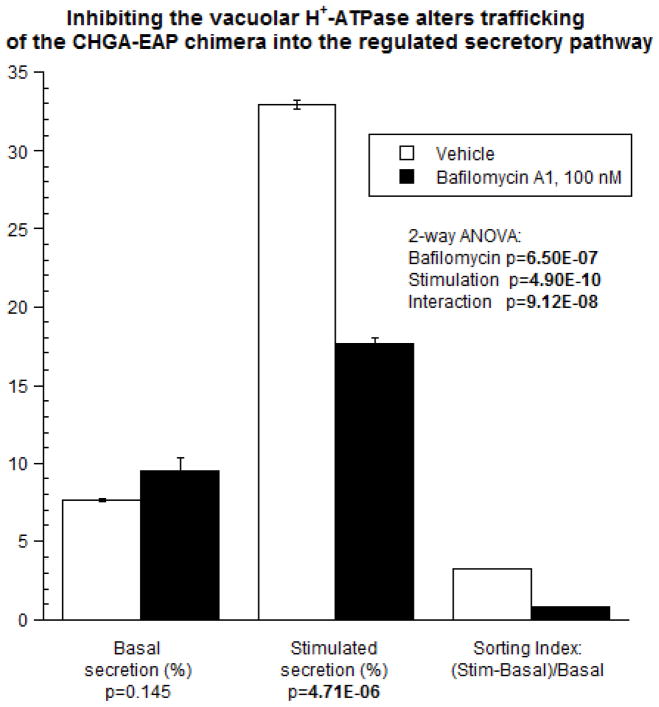

Trafficking: Bafilomycin A1 diminishes regulated secretory pathway trafficking of a CHGA-EAP chimera

To probe the potential role of the V-ATPase in protein trafficking into chromaffin granules, we inhibited the V-ATPase with bafilomycin A1 (100 nM). After 18 hours of pre-exposure of CHGA-EAP-expressing PC12 cells to bafilomycin A1, Ba2+-induced CHGA-EAP secretion was inhibited by ~1/2 (Figure 4). In contrast, unstimulated (basal) release of the fusion protein was unchanged during bafilomycin A1. Interaction of secretory stimulus and pH change (p=9.12E-08), coupled with the decline in sorting index, indicates that inhibition of V-ATPase disrupts the progress of CHGA-EAP into the regulated secretary pathway, likely diverting the chimera into the constitutive (unregulated) pathway of secretion, or even out of the secretory pathway altogether.

Figure 4.

V-ATPase inhibition by bafilomycin A1 alters trafficking of CHGA to the regulated secretory pathway in chromaffin cells. Secretion of EAP enzymatic activity of chimeric CHGA-EAP photoproteins exposed for 18 hours to bafilomycin A1 (10 nM) or vehicle (DMSO), is shown. Expression of each chimera is driven by the strong pCMV promoter. Units for basal secretion and stimulated secretion are % (of cell total stores). Sorting index is a dimensionless ratio. Values represent the mean ± SEM, for n=3 replicates per condition.

Thus, loss of the vacuolar pH gradient seems to enhance CHGA processing while impairing its regulated secretion.

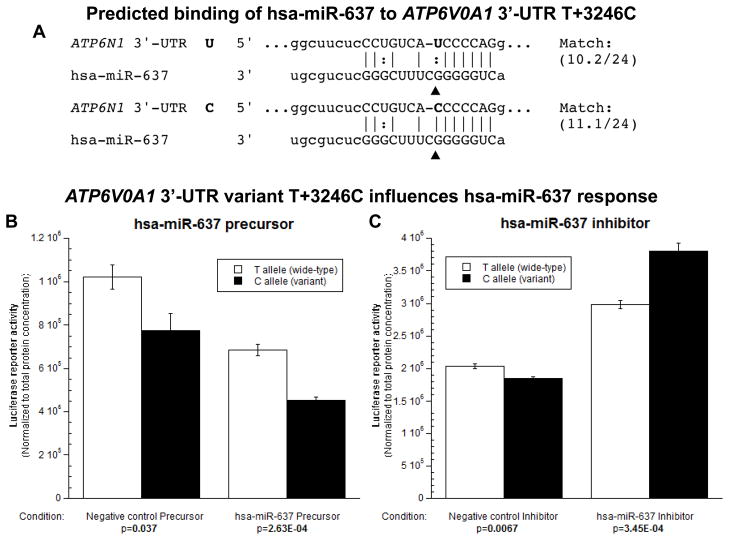

ATP6V0A1 3′-UTR variant T+3246C functions through micro-RNA hsa-miR-637

Computation

The local region of the 3′-UTR surrounding T+3246C is highly conserved (indeed, invariant) in other sequenced primate species, except for either T or C in the SNP position (supplemental Figure 2). miRNA motif predictions suggested that T+3246C is located in a region complementary to hsa-miR-637, with a superior match for the C (variant) allele (Figure 5A), raising the possibility of diminished mRNA translation 18 for transcripts bearing the C allele. The predicted minimum folding energy of hsa-miR-637 differed between T (i.e., “U” in the mRNA) and C: −24.8 vs. −27.3 kcal/mol. The lower minimum folding energy of the C allele would predict better binding of hsa-miR-637 to the +3246C mRNA, and hence more efficient translational repression (or perhaps even degradation) of the variant/C mRNA, a finding consistent with decreased reporter expression by the variant/C luciferase/3′-UTR plasmid (Figure 1).

Figure 5.

3′-UTR variant T+3246C influences miRNA hsa-miR-637 regulation of ATP6V0A1 gene expression. A. Computation. The calculated miRNA::mRNA interaction is shown, with the SNP highlighted. B and C. Luciferase reporter activity of luciferase/ATP6V0A1 3′-UTR plasmids co-transfected with hsa-miR-637 precursor (B), inhibitor (C), or their negative control; values represent the mean ± SEM in n=6 replicates for each condition.

hsa-miR-637 mimicry

To validate a differential hsa-miR-637 effect on T+3246C, a specific 24-mer miRNA precursor was co-transfected with the luciferase/3′-UTR plasmid into PC12 cells. Exogenous/co-transfected hsa-miR-637 precursor decreased reporter expression (Figure 5B). The expression difference between T and C was maintained after additional/exogenous hsa-miR-637, and the % difference between two genotypes (T→C) was amplified appreciably (32.8% in the negative controls vs. 41.6% during hsa-miR-637 treatment). By 2-way ANOVA, p=0.001 for variant, p=1.45E-05 for precursor, and p=0.757 for interaction.

hsa-miR-637 antagonism

Inhibition of hsa-miR-637 by a specific “antagomir” increased reporter expression (Figure 5C). In the baseline state (negative control group), the expression pattern was C < T, consistent with the initial transfection experiments (Figure 1). After knockdown of hsa-miR-637, however, this difference was reversed to C > T.

Both enhancement and inhibition results for hsa-miR-637 were consistent with the hypothesis that the C < T expression pattern occurs because of higher affinity of the C allele for hsa-miR-637, with consequent translational repression. By 2-way ANOVA, p=6.67E-04 for variant, p=3.07E-13 for inhibitor, and p=4.25E-06 for interaction.

Discussion

Overview

In this study, we aimed to clarify the mechanism whereby 3′-UTR (T+3246C; rs938671) genetic variation at the vacuolar H+-ATPase subunit ATP6V0A1 influences CHGA/catestatin secretion and consequently BP in the population 6. We began by isolating the ATP6V0A1 3′-UTR onto a luciferase reporter gene, revealing that +3246C decreased reporter expression (Figure 1A); the effects on gene expression were documented by coupled in vitro transcription/translation (Figure 1B), and we observed directionally coordinate effects on luciferase reporter activity in vitro and catestatin in vivo (supplemental Figure 3). The +3246C allele also impaired control of vacuolar pH, during disruption of the H+ gradient (Figure 2). When V-ATPase was inhibited by bafilomycin A1, proteolytic cleavage of CHGA seemed to be enhanced in chromaffin cells (Figure 3). Bafilomycin A1 also impaired CHGA-EAP chimera sorting into chromaffin granules for regulated secretion (Figure 4). Computation suggested that T+3246C disrupted a micro-RNA recognition motif for hsa-miR-637 (Figure 5); data from over-expression or knockdown of hsa-miR-637 were consistent with an enhanced effect of the miRNA on the C allele, to account for its diminution in ATP6V0A1 expression. Taken together, the results suggest that a 3′-UTR variant influences ATP6V0A1 expression through altered miRNA recognition, thereby changing vesicular pH with consequences for CHGA processing and regulated secretion, ultimately influencing BP in the population.

Secretory protein processing and/or trafficking: Actions of the vacuolar H+-ATPase

Previous research revealed a statistical association of ATP6V0A1 3′-UTR variant T+3246C with altered plasma concentration of CHGA and its fragment catestatin 6. Since ATP6V0A1 is an essential component of the vacuolar H+-ATPase, a change in CHGA/catestatin secretion could be envisioned to result from two kinds of alterations: proteolytic cleavage of CHGA to its fragments, and/or regulated secretory pathway trafficking of the granin.

The ratio of CHGA/fragment concentrations in chromaffin cells was substantially reduced after exposure to bafilomycin A1, as shown in the quantified immunoblot (Figure 3A); this decreased precursor/product ratio is consistent with enhanced CHGA processing to catestatin. However, bafilomycin A1 has a variety of reported effects on secretory protein processing 19, 20. Such variable results may be dependent on a variety of factors, such that secretory protein substrates are cleaved by various sets of proteases at different pH optima. In the case of CHGA, particular involved proteases may favor pH optima higher than that within secretory granules (in situ pH~5.5), such as prohormone convertase PC1 (optimum pH=6.0) 21, 22, thereby predicting better efficiency when pH is elevated by bafilomycin A1. After bafilomycin treatment, why do fragments increase only moderately while CHGA decreases more substantially? CHGA is proteolytically cleaved to other fragments which cannot be captured by anti-catestatin, since CHGA is the precursor of several other peptide fragments (e.g., pancreastatin, vasostatin).

To understand exocytosis from chromaffin granules, we followed CHGA secretion with a chemiluminescent EAP reporter fused in-frame to its carboxy-terminus. The EAP tag has multiple advantages, including high sensitivity and low background 12. Bafilomycin A1 impaired granin trafficking into and secretion from the regulated pathway (Figure 4). This result may explain why concentrations of CHGA and catestatin are lower in +3246C population. Other protein/protein interactions influence secretory pathway acidification; for example, disrupted granule acidification caused by furin ablation reduced secretion of insulin in mice 23, and V-ATPase activity regulation by HRG-1 influences trafficking of a membrane protein (transferrin receptor) 24.

3′-UTR variant T+3246C as a micro-RNAtarget site polymorphism

miRNAs are a class of non-coding small RNAs that regulate gene expression by complementary base pairing to target motifs, typically in 3′-UTR regions of mRNAs, with consequent transcript cleavage (in the case of a perfect match) or translational repression (in the case of a partial match). SNPs that reside in miRNA target motifs 25, may either abolish existing binding sites or create novel binding sites. Such variants are potentially implicated in a broad range of human traits 26, despite stronger negative selection in miRNA sites than in other motifs of the 3′-UTR 27. In our case, blood pressure-associated variant +3246C (rs938671) in the ATP6V0A1 3′-UTR created a binding site for hsa-miR-637. We confirmed predictions for such a site by both over-expression and knockdown of hsa-miR-637: differential expression between reporters with wide-type and variant 3′-UTRs was magnified after over-expressing hsa-miR-637, and was “rescued” or even reversed after knockdown hsa-miR-637 (Figure 5). These results suggest that ATP6V0A1 T+3246C does affect hsa-miR-637 binding to modulate gene expression. We also detected partial homology of the T+3246C region to another micro-RNA motif (hsa-miR-331), but the selective antagomir for that miRNA did not influence expression of the transfected luciferase/3′-UTR reporter plasmids (data not shown). Inspection of NCBI GEO datasets reveals abundant endogenous ATP6V0A1 expression in the adrenal gland (GDS1464) 28, as well as clonal chromaffin cells (GDS2555) 29.

Vacuolar H+-ATPase functions

The vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) is a multi-subunit complex which has important roles in the acidification of a variety of several intracellular compartments as well as extracellular milieus. The ATP6V0A1 which we investigate in this work encodes the a1 isoform of the “a” subunit in the V0 (H+ translocation, integral membrane) domain. There are 4 known isoforms of the “a” subunit (a1–a4) which have differential cellular localizations 30. Even the a1 subunit itself may have several alternative splice forms which are targeted to different membrane compartments of the cell 31. Such diversification may lend far-ranging functions to the H+-ATPase.

In Drosophila a functional role for the V-ATPase V0 domain α1 subunit occurs in late stages of synaptic vesicle exocytosis 32; mutation in this subunit did not affect neurotransmitter content, but impaired evoked synaptic transmission. In mice, the α3 isoform may have a regulatory function in exocytotic secretion of insulin, though not insulin processing 33. In addition to secretion, the V-ATPase participates in protein degradation and membrane fusion 34,35. Thus the vacuolar H+-ATPase is involved in a variety of physiological and anatomical systems 36, including the heart 37, kidney 38 and skeletal muscle 39.

Advantages and limitations of this study

Here we undertook functional studies at a positional candidate genetic locus on chromosome 17q, ATP6V0A1, to document biological mechanisms underlying the statistical genetic association of marker and trait. Thus ATP6V0A1 seems to be a trans-QTL (quantitative trait locus) for CHGA/catestatin secretion and BP, while T+3246C (rs938671) may represent a trans-“QTN” (Quantitative Trait Nucleotide) at that locus. Using luciferase and EAP as reporter genes allowed us to quantify expression and secretion, and so document effects of the variant as well as the trans-acting factor hsa-miR-637, thereby permitting quantitative verification to augment the plausibility of our conclusions.

Although T+3246C/rs938671 is a human variant, the functional studies conducted here were performed in rodent (rat PC12 cell) pheochromocytoma cells, since the PC12 line is well established for studies of secretory protein traffic 15. Human MIR637, the gene encoding hsa-miR-637, is located on human chromosome 19p in the fifth intron of DAPK3. While miR-637 is not yet well characterized in the rat, the homologous intronic region of rat Dapk3 displays 82% sequence identity with human miR637. Intriguingly, rat Dapk3 is also within a QTL region for blood pressure 40.

Catecholamine storage depends on the vacuolar H+-ATPase 12, but our transient transfection studies typically target only a minor % of plated cells, and thus did not permit a more global analysis of catecholamine metabolism. Finally, we did not examine the effect of other genetic variants at the positional candidate locus, ATP6V0A1, although T+3246C (rs938671) was selected for study since it is the only common (minor allele frequency >5%) variant observed so far in the transcript region (exons) of Caucasians (CEU), the source population for the original linkage and association result 6. Finally, future studies with appropriate animal models may assist in confirming the H+-ATPase mechanism in vivo.

Conclusions and perspectives

ATP6V0A1 3′-UTR common polymorphism T+3246C (rs938671) is associated with CHGA/catestatin secretion and systemic blood pressure in the population. Here we explored precisely how such genetic variation affected sympathochromaffin exocytosis. As shown in schematic supplemental Figure 4, our results support the viewpoint that T+3246C is located in a binding motif for micro-RNA hsa-miR-637, at which the C allele may impair translation of the ATP6V0A1 mRNA. Since ATP6V0A1 is a necessary subunit of the vacuolar H+-ATPase, its reduced expression may thus impair the physiological acidification of intracellular organelles such as chromaffin granules. Consequently, the processing of CHGA may be enhanced and the secretion of proteins/peptides such as CHGA/catestatin may be impaired. The results shed new light on the role of chromaffin granule acidification in processing and trafficking of secretory peptides/proteins, pointing to new molecular strategies for probing autonomic control of the circulation, and ultimately the susceptibility to and pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease states such as hypertension.

Supplementary Material

Here we explored molecular mechanisms of how a polymorphism (T+3246C) in the 3′-UTR of the proton translocating ATPase (V-ATPase) subunit ATP6V0A1 influences human cardiovascular traits, including chromogranin A (CHGA) and BP. First, using a luciferase reporter plasmid, we found that the C (variant) allele of T+3246C (rs938671) decreased overall gene expression. The 3′-UTR effect was verified by coupledin vitro transcription/translation of the entire/intact human ATP6V0A1 mRNA. Second, by over-expression and knockdown of a specific microRNA, we found that T+3246C disrupted a microRNA recognition motif for hsa-miR-637. Third, sinceATP6V0A1 is an important component of the V-ATPase, chromatin granule pH was monitored by fluorescence of a CHGA/EGFP chimera: the +3246C allele impaired control of vacuolar pH. Fourth, increased pH (caused by the C allele) was then mimicked by the V-ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin A1. After bafilomycin A1, the ratio of CHGA precursor to its catestatin fragment was diminished. Bafilomycin A1 also decreased exocytotic secretion from the regulated pathway. The results point to new molecular and mRNA translational strategies for probing autonomic control of the circulation, and ultimately the susceptibility to and pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease states such as hypertension.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: National Institutes of Health [HL58120; RR00827 (UCSD General Clinical Research Center); MD000220 (UCSD Comprehensive Research Center in Health Disparities, CRCHD)], Department of Veterans Affairs.

Glossary of abbreviations

- ATP6V0A1

Gene of vacuolar-type ATPase, H+-translocating, subunit a isoform 1

- CHGA

Chromogranin A

- EAP

Embryonic Alkaline Phosphatase

- hsa-miR-637

Human micro-RNA 637

- H+-ATPase

Proton-translocating ATPase

- miRNA

miR, micro-RNA

- PC12

Rat pheochromocytoma cell line

- SNP

Single Nucleotide Polymorphism

- 3′-UTR

3′-untranslated region (of mRNA)

- V-ATPase

Vacuolar-type ATPase

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None

References

- 1.Mahata SK, O’Connor DT, Mahata M, Yoo SH, Taupenot L, Wu H, Gill BM, Parmer RJ. Novel autocrine feedback control of catecholamine release. A discrete chromogranin a fragment is a noncompetitive nicotinic cholinergic antagonist. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1623–1633. doi: 10.1172/JCI119686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taupenot L, Harper KL, O’Connor DT. The chromogranin-secretogranin family. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1134–1149. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra021405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahata SK, Mahata M, Fung MM, O’Connor DT. Catestatin: A multifunctional peptide from chromogranin a. Regul Pept. 2010;162:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.regpep.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Connor DT, Kailasam MT, Kennedy BP, Ziegler MG, Yanaihara N, Parmer RJ. Early decline in the catecholamine release-inhibitory peptide catestatin in humans at genetic risk of hypertension. J Hypertens. 2002;20:1335–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200207000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahapatra NR, O’Connor DT, Vaingankar SM, Hikim AP, Mahata M, Ray S, Staite E, Wu H, Gu Y, Dalton N, Kennedy BP, Ziegler MG, Ross J, Mahata SK. Hypertension from targeted ablation of chromogranin a can be rescued by the human ortholog. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1942–1952. doi: 10.1172/JCI24354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connor DT, Zhu G, Rao F, Taupenot L, Fung MM, Das M, Mahata SK, Mahata M, Wang L, Zhang K, Greenwood TA, Shih PA, Cockburn MG, Ziegler MG, Stridsberg M, Martin NG, Whitfield JB. Heritability and genome-wide linkage in us and australian twins identify novel genomic regions controlling chromogranin a: Implications for secretion and blood pressure. Circulation. 2008;118:247–257. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.709105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brody LC, Abel KJ, Castilla LH, Couch FJ, McKinley DR, Yin G, Ho PP, Merajver S, Chandrasekharappa SC, Xu J, Cole JL, Struewing JP, Valdes JM, Collins FS, Weber BL. Construction of a transcription map surrounding the brca1 locus of human chromosome 17. Genomics. 1995;25:238–247. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(95)80131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JH, Johannes L, Goud B, Antony C, Lingwood CA, Daneman R, Grinstein S. Noninvasive measurement of the ph of the endoplasmic reticulum at rest and during calcium release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:2997–3002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.6.2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miesenbock G, De Angelis DA, Rothman JE. Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with ph-sensitive green fluorescent proteins. Nature. 1998;394:192–195. doi: 10.1038/28190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu MM, Grabe M, Adams S, Tsien RY, Moore HP, Machen TE. Mechanisms of ph regulation in the regulated secretory pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:33027–33035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103917200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu MM, Llopis J, Adams S, McCaffery JM, Kulomaa MS, Machen TE, Moore HP, Tsien RY. Organelle ph studies using targeted avidin and fluorescein-biotin. Chem Biol. 2000;7:197–209. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(00)00088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taupenot L, Harper KL, O’Connor DT. Role of h+-atpase-mediated acidification in sorting and release of the regulated secretory protein chromogranin a: Evidence for a vesiculogenic function. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3885–3897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishi T, Forgac M. The vacuolar (h+)-atpases--nature’s most versatile proton pumps. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:94–103. doi: 10.1038/nrm729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Courel M, Soler-Jover A, Rodriguez-Flores JL, Mahata SK, Elias S, Montero-Hadjadje M, Anouar Y, Giuly RJ, O’Connor DT, Taupenot L. Pro-hormone secretogranin ii regulates dense core secretory granule biogenesis in catecholaminergic cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10030–10043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.064196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taupenot L. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. Unit 15. Chapter 15. 2007. Analysis of regulated secretion using pc12 cells; p. 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowman EJ, Siebers A, Altendorf K. Bafilomycins; a class of inhibitors of membrane atpases from microorganisms, animal cells, and plant cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:7972–7976. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshimori T, Yamamoto A, Moriyama Y, Futai M, Tashiro Y. Bafilomycin a1, a specific inhibitor of vacuolar-type h+-atpase, inhibits acidification and protein degradation in lysosomes of cultured cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17707–17712. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pillai RS, Bhattacharyya SN, Filipowicz W. Repression of protein synthesis by mirnas: How many mechanisms? Trends Cell Biol. 2007;17:118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Horssen AM, Martens GJ. Biosynthesis of secretogranin ii in xenopus intermediate pituitary. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1999;147:57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00219-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oda K, Nishimura Y, Ikehara Y, Kato K. Bafilomycin a1 inhibits the targeting of lysosomal acid hydrolases in cultured hepatocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;178:369–377. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91823-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou Y, Lindberg I. Purification and characterization of the prohormone convertase pc1(pc3) J Biol Chem. 1993;268:5615–5623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jean F, Basak A, Rondeau N, Benjannet S, Hendy GN, Seidah NG, Chretien M, Lazure C. Enzymic characterization of murine and human prohormone convertase-1 (mpc1 and hpc1) expressed in mammalian gh4c1 cells. Biochem J. 1993;292(Pt 3):891–900. doi: 10.1042/bj2920891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Louagie E, Taylor NA, Flamez D, Roebroek AJ, Bright NA, Meulemans S, Quintens R, Herrera PL, Schuit F, Van de Ven WJ, Creemers JW. Role of furin in granular acidification in the endocrine pancreas: Identification of the v-atpase subunit ac45 as a candidate substrate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:12319–12324. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800340105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Callaghan KM, Ayllon V, O’Keeffe J, Wang Y, Cox OT, Loughran G, Forgac M, O’Connor R. Heme-binding protein hrg-1 is induced by insulin-like growth factor i and associates with the vacuolar h+-atpaseto control endosomal ph and receptor trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:381–391. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.063248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mishra PJ, Humeniuk R, Longo-Sorbello GSA, Banerjee D, Bertino JR. A mir-24 microrna binding-site polymorphism in dihydrofolate reductase gene leads to methotrexate resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13513–13518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706217104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sethupathy P, Collins FS. Microrna target site polymorphisms and human disease. Trends Genet. 2008;24:489–497. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen K, Rajewsky N. Natural selection on human microrna binding sites inferred from snp data. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1452–1456. doi: 10.1038/ng1910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friese RS, Mahboubi P, Mahapatra NR, Mahata SK, Schork NJ, Schmid-Schonbein GW, O’Connor DT. Common genetic mechanisms of blood pressure elevation in two independent rodent models of human essential hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18:633–652. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lattanzi W, Bernardini C, Gangitano C, Michetti F. Hypoxia-like transcriptional activation in tmt-induced degeneration: Microarray expression analysis on pc12 cells. J Neurochem. 2007;100:1688–1702. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schulz N, Dave MH, Stehberger PA, Chau T, Wagner CA. Differential localization of vacuolar h-atpases containing a1, a2, a3, or a4 (atp6v0a1-4) subunit isoforms along the nephron. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2007;20:109–120. doi: 10.1159/000104159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Poëa-Guyon S, Amar M, Fossier P, Morel N. Alternative splicing controls neuronal expression of v-atpase subunit a1 and sorting to nerve terminals. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:17164–17172. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600927200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hiesinger PR, Fayyazuddin A, Mehta SQ, Rosenmund T, Schulze KL, Zhai RG, Verstreken P, Cao Y, Zhou Y, Kunz J, Bellen HJ. The v-atpase v0 subunit a1 is required for a late step in synaptic vesicle exocytosis in drosophila. Cell. 2005;121:607–620. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun-wada GH, Toyomura T, Murata Y, Yamamoto A, Futai M, Wada Y. The a3 isoform of v-atpase regulates insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4531–4540. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hurtado-Lorenzo A, Skinner M, El Annan J, Futai M, Sun-Wada GH, Bourgoin S, Casanova J, Wildeman A, Bechoua S, Ausiello DA, Brown D, Marshansky V. V-atpase interacts with arno and arf6 in early endosomes and regulates the protein degradative pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:124–136. doi: 10.1038/ncb1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Williamson WR, Wang D, Haberman AS, Hiesinger PR. A dual function of v0-atpase a1 provides an endolysosomal degradation mechanism in drosophila melanogaster photoreceptors. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:885–899. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forgac M. Vacuolar atpases: Rotary proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:917–929. doi: 10.1038/nrm2272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gottlieb RA, Gruol DL, Zhu JY, Engler RL. Preconditioning in rabbit cardiomyocytes: Role of ph, vacuolar proton atpase, and apoptosis. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:2391–2398. doi: 10.1172/JCI118683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith AN, Skaug J, Choate KA, Nayir A, Bakkaloglu A, Ozen S, Hulton SA, Sanjad SA, Al-Sabban EA, Lifton RP, Scherer SW, Karet FE. Mutations in atp6n1b, encoding a new kidney vacuolar proton pump 116-kd subunit, cause recessive distal renal tubular acidosis with preserved hearing. Nat Genet. 2000;26:71–75. doi: 10.1038/79208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ramachandran N, Munteanu I, Wang P, Aubourg P, Rilstone JJ, Israelian N, Naranian T, Paroutis P, Guo R, Ren ZP, Nishino I, Chabrol B, Pellissier JF, Minetti C, Udd B, Fardeau M, Tailor CS, Mahuran DJ, Kissel JT, Kalimo H, Levy N, Manolson MF, Ackerley CA, Minassian BA. Vma21 deficiency causes an autophagic myopathy by compromising v-atpase activity and lysosomal acidification. Cell. 2009;137:235–246. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rapp JP. Genetic analysis of inherited hypertension in the rat. Physiol Rev. 2000;80:135–172. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2000.80.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.