Abstract

J.B.S. Haldane proposed in 1947 that the male germline may be more mutagenic than the female 1. Diverse studies have supported Haldane’s contention of a higher average mutation rate in the male germline in a variety of mammals, including humans (e.g. 2,3). Here we present the first direct comparative analysis of male and female germline mutation rates from complete genome sequences of two parent-offspring trios. Through extensive validation, we identified 49 and 35 germline de novo mutations (DNMs) in two trio offspring, as well as 1,586 non-germline DNMs arising either somatically or in the cell-lines from which DNA was derived. Most strikingly, in one family we observed that 92% of germline DNMs were from the paternal germline, while, in complete contrast, in the other family 64% of DNMs were from the maternal germline. These observations reveal considerable variation in mutation rates within and between families.

Mutation underlies all heritable genetic variation, and the observation that a mutation has arisen de novo can be highly discriminating for identifying causal pathogenic variation in patients 4-6. Attempts to measure mutation rates in humans fall into two broad categories: direct methods that estimate the number of mutations that have occurred in a known number of generations 7,8, and indirect methods that infer mutation rates from levels of genetic variation within or between species. Previous estimates of germ-line base substitution rates range from 1.1 to 3 × 10−8 per base per generation 7,9-14. This variation is due, in part, to uncertainty or assumptions in key parameters, such as divergence times between species, generation times and ancestral population sizes. Furthermore, all previous estimates represent an average across multiple generations and/or an average of male and female mutation rates. Consequently, the previous studies provide no information on how mutation rates vary between individuals of either the same or different sexes or indeed between gametes within an individual. It has been proposed that the mammalian male germline may be more mutagenic than the female, because of the greater number of cell divisions 1. Subsequent studies (e.g. 2,3) have suggested, on average, the male germline is more mutagenic than the female, with the most robust recent estimate 3 based on whole genome sequences of human and chimpanzee, suggesting a six-fold difference, averaged across ~5-7 million years of independent evolution of the two lineages.

High-throughput sequencing enables whole-genome analysis of mutation rates in human pedigrees 7, and promises to revolutionize our understanding of how mutation rates vary between sexes, individuals and families. We analyzed lymphoblastoid cell-lines from two parent-offspring trios (CEU and YRI) sequenced genome-wide to greater than 22-fold mapped depth using three different sequencing platforms during the pilot phase of the 1000 genomes project (15, Online Methods). We developed three independent probabilistic algorithms, to identify candidate de novo mutations (DNMs) from these sequence data (Supplementary Note). From the union of candidate DNMs identified by the three algorithms 3,236 and 2,750 potential DNMs were selected for experimental validation from the CEU and YRI trios respectively, far in excess of the expected number of true germline DNMs, to maximize our sensitivity to detect DNMs.

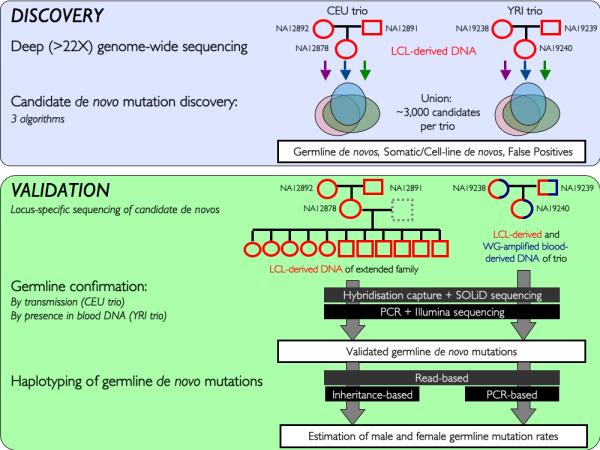

We attempted validation of every candidate DNM, using two novel experimental approaches and additional resources from each family to unambiguously distinguish germline DNMs from somatic or cell-line DNMs (Figure 1, Online Methods, Tables S1-3). For the CEU trio these validation experiments were performed on LCL-derived DNA from both the original trio and a third-generation from the same family. For the YRI trio these validation experiments were performed on LCL-derived DNA from the trio as well as whole-genome-amplified blood-derived DNA from the same individuals. Using these validation data we classified each putative DNM into one of five categories: (i) germline DNM, (ii) non-germline (somatic or arising in cell culture) DNM, (iii) inherited variant (iv) false positive, (v) inconclusive (Table 1, Supplementary Note, Table S1 and Figures S1-2). We identified 49 and 35 germline DNMs and 952 and 643 non-germline DNMs in the CEU and YRI trios respectively. The observed ~20:1 ratio of non-germline DNMs to germ-line DNMs is substantially larger than the 1:1 ratio published previously 4. This difference could be due to the age of the cell-lines (number of passages), the mutagenicity of the cell culture conditions and/or the clonality of the cell-lines. We observed differences in the mutational characteristics of germline DNMs, non-germline DNMs and inherited germline variants, in terms of the ratio of transitions and transversions, the proportion of CpG mutations, the clonality of mutations, their occurrence at sites under selective constraint and the evidence for transcription coupled repair (Table 1, Supplementary Note, Figure S3-4).

Figure 1. Overview of study design.

The two phases of the project: discovery and validation are shown schematically, including the samples from each family that were used in each phase. LCL – Lymphoblastoid Cell Line, WG – Whole Genome

Table 1. Mutational properties of different classes of validated sites.

‘Posterior Prob’, average support metric (posterior probability or LOD score) of calls reported by each discovery method; ‘Ts:Tv’, ratio of transitions to transversions; ‘CpG’, proportion of sites within CpG; ‘GERP’, average GERP score. ‘No Call’, insufficiently informative data to make a high confidence call.

| Germline DNMs |

Non-germline DNMs |

False Positives | Inherited Variant |

No Call | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (CEU/YRI) | Total (CEU/YRI) | Total (CEU/YRI) | Total (CEU/YRI) | Total (CEU/YRI) | |

| Count | 84 (49/35) | 1586 (952/634) | 2360 (1304/1065) | 464 (129/335) | 1483 (802/681) |

| Posterior Prob | |||||

| FIGL | 0.98 (1/0.96) | 0.95 (0.96/0.94) | 0.87 (0.9/0.83) | 0.78 (0.79/0.77) | 0.83 (0.86/0.78) |

| FPIR | 0.96 (0.97/0.96) | 0.9 (0.93/0.85) | 0.63 (0.72/0.52) | 0.38 (0.46/0.35) | 0.59 (0.68/0.47) |

| SIMTG | 13.38 (13.3/13.55) | 9.76 (9.68/9.91) | 10.75 (10.42/11.17) | 11.16 (10.28/11.59) | 11.06 (10.97/11.2) |

| Ts:Tv | 2.82 (2.5/3.38) | 0.98 (0.92/1.06) | 0.76 (0.8/0.72) | 1.83 (1.43/2.02) | 1.1 (0.99/1.25) |

| CpG | 0.13 (0.14/0.11) | 0.07 (0.09/0.06) | 0.06 (0.05/0.06) | 0.13 (0.14/0.13) | 0.07 (0.06/0.1) |

| GERP | −0.3 (−0.28/−0.32) | −0.18 (−0.22/−0.11) | −0.21 (−0.2/−0.22) | −0.25 (−0.45/−0.18) | −0.22 (−0.25/−0.18) |

| Function | |||||

| Coding-missense | 0 (0/0) | 16 (6/10) | 15 (10/5) | 2 (1/1) | 0 (0/0) |

| Coding-synon | 1 (1/0) | 1 (0/1) | 9 (8/1) | 0 (0/0) | 4 (1/3) |

| NMD_transcript | 0 (0/0) | 2 (1/1) | 7 (4/3) | 3 (0/3) | 4 (0/4) |

| Splice Site | 0 (0/0) | 3 (3/0) | 0 (0/0) | 0 (0/0) | 0 (0/0) |

| 5′-UTR | 0 (0/0) | 3 (3/0) | 4 (0/4) | 0 (0/0) | 4 (2/2) |

| 3′-UTR | 0 (0/0) | 5 (4/1) | 20 (14/6) | 3 (2/1) | 11 (6/5) |

| non-coding gene | 5 (4/1) | 122 (75/46) | 197 (96/102) | 36 (11/25) | 100 (54/46) |

| Intronic | 36 (19/17) | 521 (319/197) | 806 (437/374) | 177 (54/123) | 552 (305/247) |

| Intergenic | 42 (25/17) | 925 (544/378) | 1302 (735/570) | 243 (61/182) | 808 (434/374) |

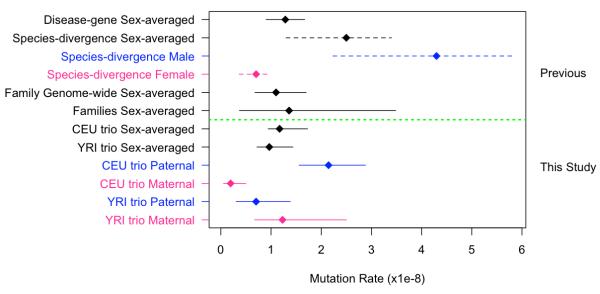

By estimating the false negative rates in discovery and validation of DNMs and quantifying the proportion of the genome that we were able to scrutinize reliably for DNMs (Supplementary Note), we estimated the germline DNM rate in each trio to be 1.17 × 10−8 (95% CI: 0.88 × 10−8 - 1.62 × 10−8) and 0.97 × 10−8 (95% CI: 0.67 × 10−8 - 1.34 × 10−8) for the CEU and YRI trios respectively. The sex-averaged germline mutation rate estimates we derived agree very closely with three other recent studies focusing on sex-averaged mutation rates in the most recent generation 4,7,13. Averaging across these four studies gives a more precise sex-averaged mutation rate of 1.18×10−8 (±0.15×10−8), which is less than half of the frequently-cited sex-averaged mutation rate derived from human-chimpanzee sequence divergence of 2.5×10−8 14. These apparently discordant, estimates can be largely reconciled if the age of the human-chimpanzee divergence is pushed back to 7 million years, as suggested by some interpretations of recent fossil finds 16, and by considering more recent (and slightly lower), robust genome-wide estimates of sequence divergence 17. These considerations suggest a plausible range for the divergence-derived mutation rate of 1.12×10−8 to 2.05×10−8, which encompasses the averaged contemporary mutation rate above. Moreover, by considering that the distribution of mutation rates in the population could contain a long tail of relatively rare individuals with considerably higher mutation rates (perhaps as a result of genetic or environmental factors), it can be appreciated that the mean rate across many generations could be considerably greater than the modal rate within a generation.

We ascertained for most germline DNMs whether they arose on a paternal or maternal haplotype, using three alternative methods (Online Methods, Supplementary Note, Table S1). Where more than one haplotyping method could be applied to the same DNM (N=17) the results were 100% concordant. Male and female germline mutation rates in the two trios (Figure 2) were significantly different (p < 3 × 10−6, Fisher exact test). In one family, 92% of germline DNMs are from the paternal germline, whereas, in the other family only 36% of DNMs were paternal in origin. Although, the confidence intervals of some of the parent-specific rates overlap, the paternal rates in the two trios do not overlap, and neither do the maternal rates. These differences could be due to extensive variation in the number of DNMs in gametes from the same individual or to considerable variation between individuals in their underlying DNM rate. With only a single offspring per family, we cannot distinguish between these two alternatives, but either would give rise to substantial variation in the number of DNMs between offspring of different families. The potential scale of this variation can be appreciated by simply considering that exchanging the paternal gamete in the CEU trio for that in the YRI trio would have resulted in a five-fold difference in the number of mutations seen in the two offspring.

Figure 2. Comparison of mutation rate estimates.

Mutation rates estimated from previous studies are shown above the dashed green line. Solid lines encompassing point estimates represent 95% confidence intervals. Dashed lines encompassing point estimates represent reported plausible ranges. ‘Disease-gene Sex-averaged’ rate comes from 13, with 95% confidence intervals calculated as 1.96 times the standard error. ‘Species-divergence Sex averaged rate’ comes from 14, which specifies the plausible range shown here. Species-divergence sex-specific rates come from scaling the sex-averaged point estimate and upper and lower bounds by the ratio of male/female mutation rate of 6.11 estimated by 3. ‘Family Genome-wide Sex-average’ comes from 7, ‘Families Sex-average’ comes from 4.

Some of this variation in mutation rates between families might be explained by differences in parental ages and a dependency of mutation rate on age. Unfortunately, parental ages at conception for these two trios were not available, nevertheless the analysis of larger sibships would be required to disentangle fully the effects of parental age from genetic and environmental factors that might also differ between families. Variation in mutation rates between individuals could also be partly explained by a recent relaxation of selective constraint on mutation rates resulting from the lower efficiency of selection in humans as compared to the most recent common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees 16, due to our small effective population size 17. Mutation is a random process and, as a result, considerable variation in numbers of mutations is to be expected between contemporaneous gametes within an individual. If modeled as Poisson process, the 95% confidence intervals on a mean number of ~30 DNMs per gamete (as expected from a mutation rate of ~1×10−8) ranges from 20 to 41, a two-fold difference. Truncating selection might act to remove the most mutated gametes and thus reduce this variation among gametes that successfully reproduce, however, any additional heterogeneity in stem cell ancestry or environment, for example, variation in the number of cell divisions leading to contemporaneous gametes, would likely increase inter-gamete variation in numbers of mutations.

In summary, while there may be growing concordance in estimates of the average mutation rate in contemporary generations, we have presented evidence of substantial variance in sex-specific mutation rates between families. The variation in mutation rates that we observed is of potential clinical significance, as it suggests that the risk of mis-diagnosing a DNM as being pathogenic could vary substantially between patients.

Advances in sequencing technologies that lower costs and increase fidelity (Supplementary Note) will empower further studies into mutational processes by applying the framework we have established here for estimating sex-specific mutation rates in families. These future studies promise to revolutionise our understanding of mutation processes, and how they vary between individuals and between families as a result of age, genetic background and environmental exposures.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Gil McVean, Tim Massingham, Jeff Thorne, Julie Hussin, Alison Motsinger, Coriell Cell Repositories and members of the 1000 genomes analysis group for their help and support. DFC, SJL, YZ, CT and MEH were funded by the Wellcome Trust [grant number: 077014/Z/05/Z]. JK, FC, YI, MZ, GAR, and PA were funded by the Ministry of Development, Exploration and Innovation (grant #PSR-SIIRI-195) in Quebec and a Genome Quebec Award for Population and Medical Genomics to PA.

Footnotes

Author contributions: MEH and PA conceived of the study; DFC, JEMK, MAD, MD, RC, EAS and PA developed statistical methodologies; DFC, JEMK, MAD, CLH, KVG, EAS, MEH and PA analysed the data; FC, YI, GAR, CT, MZ, SJL and YZ generated validation data; and DFC, PA and MEH wrote the paper.

References

- 1.Haldane JBS. The mutation rate of the gene for haemophilia, and its segregation ratios in males and females. Annals of Eugenics. 1947;13:262–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1946.tb02367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohossian HB, Skaletsky H, Page DC. Unexpectedly similar rates of nucleotide substitution found in male and female hominids. Nature. 2000;406:622–625. doi: 10.1038/35020557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor J, Tyekucheva S, Zody M, Chiaromonte F, Makova KD. Strong and weak male mutation bias at different sites in the primate genomes: insights from the human-chimpanzee comparison. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:565–73. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Awadalla P, et al. Direct measure of the de novo mutation rate in autism and schizophrenia cohorts. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;87:316–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gauthier J, et al. De novo mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 in patients ascertained for schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:7863–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906232107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee C, Iafrate AJ, Brothman AR. Copy number variations and clinical cytogenetic diagnosis of constitutional disorders. Nat Genet. 2007;39:S48–54. doi: 10.1038/ng2092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roach JC, et al. Analysis of genetic inheritance in a family quartet by whole-genome sequencing. Science. 2010;328:636–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1186802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xue Y, et al. Human Y chromosome base-substitution mutation rate measured by direct sequencing in a deep-rooting pedigree. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1453–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crow JF. How much do we know about spontaneous human mutation rates? Environ Mol Mutagen. 1993;21:122–9. doi: 10.1002/em.2850210205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haldane JBS. The rate of spontaneous mutation of a human gene. Journal of Genetics. 1935;31:317–326. doi: 10.1007/BF02717892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kondrashov AS. Direct estimates of human per nucleotide mutation rates at 20 loci causing Mendelian diseases. Hum Mutat. 2003;21:12–27. doi: 10.1002/humu.10147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kondrashov AS, Crow JF. A molecular approach to estimating the human deleterious mutation rate. Hum Mutat. 1993;2:229–34. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380020312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynch M. Rate, molecular spectrum, and consequences of human mutation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:961–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912629107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nachman MW, Crowell SL. Estimate of the mutation rate per nucleotide in humans. Genetics. 2000;156:297–304. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.1.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature. 2010;467:1061–73. doi: 10.1038/nature09534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen FC, Li WH. Genomic divergences between humans and other hominoids and the effective population size of the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2001;68:444–456. doi: 10.1086/318206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lynch M. Evolution of the mutation rate. Trends Genet. 2010;26:345–52. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper GM, et al. Distribution and intensity of constraint in mammalian genomic sequence. Genome Res. 2005;15:901–13. doi: 10.1101/gr.3577405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.