Background: MIBP1 is a transcription factor that is involved in various biological processes.

Results: MIBP1 repressed genes in the NF-κB pathway and bound O-GlcNAc transferase.

Conclusion: MIBP1 is a modulator of the NF-κB pathway and is attenuated by O-GlcNAc signaling.

Significance: New regulatory mechanisms of the NF-κB pathway by MIBP1 and O-GlcNAc transferase are identified.

Keywords: Mass Spectrometry (MS), Microarray, Myc, NF-κB, O-GlcNAc, Transcription Factors, Transforming Growth Factor β (TGFβ), GSEA, MIBP1, OGT

Abstract

The transcription factor c-MYC intron binding protein 1 (MIBP1) binds to various genomic regulatory regions, including intron 1 of c-MYC. This factor is highly expressed in postmitotic neurons in the fetal brain and may be involved in various biological steps, such as neurological and immunological processes. In this study, we globally characterized the transcriptional targets of MIBP1 and proteins that interact with MIBP1. Microarray hybridization followed by gene set enrichment analysis revealed that genes involved in the pathways downstream of MYC, NF-κB, and TGF-β were down-regulated when HEK293 cells stably overexpressed MIBP1. In silico transcription factor binding site analysis of the promoter regions of these down-regulated genes showed that the NF-κB binding site was the most overrepresented. The up-regulation of genes known to be in the NF-κB pathway after the knockdown of endogenous MIBP1 in HT1080 cells supports the view that MIBP1 is a down-regulator of the NF-κB pathway. We also confirmed the binding of the MIBP1 to the NF-κB site. By immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry, we detected O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) transferase as a prominent binding partner of MIBP1. Analyses using deletion mutants revealed that a 154-amino acid region of MIBP1 was necessary for its O-GlcNAc transferase binding and O-GlcNAcylation. A luciferase reporter assay showed that NF-κB-responsive expression was repressed by MIBP1, and stronger repression by MIBP1 lacking the 154-amino acid region was observed. Our results indicate that the primary effect of MIBP1 expression is the down-regulation of the NF-κB pathway and that this effect is attenuated by O-GlcNAc signaling.

Introduction

The expression of genes in cells changes in response to environmental cues and/or the intrinsic transcriptional network in which many transcription factors participate. The availability of whole-genome sequence data now allows us to identify numerous candidate transcription factors and to characterize the targets of each of them in an unbiased manner to elucidate the possible interplay of transcription factors in the cell. This elucidation is a fundamentally important task of systems biology (1). Using established high throughput methods and external data sources, we characterized the transcription factor c-MYC intron binding protein 1 (MIBP1).2

MIBP1 is a large, 2,437-amino acid protein (GenBankTM accession number D37951) that contains two C2H2-type double zinc fingers in its N and C termini and is a member of a family of large zinc finger proteins that contains three members in mammals (2–5). The full-length MIBP1 cDNA was cloned, taking advantage of its ability to encode a protein that binds to a regulatory element in intron 1 of rat c-MYC (2). Several groups identified this protein and have shown that it can bind to regulatory elements located in various genes; as a result, this protein has several names, including human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enhancer-binding protein 2 (HIVEP2), MBP-2, AT-BP1, AGIE-BP1, ZAS-2, and Schnurri-2 (5–10). However, many of these early studies were based on observations using truncated proteins that were produced from partial cDNA sequences.

Our previous study using Northern blots and in situ hybridization demonstrated high MIBP1 expression in the rat brain, especially in fetal postmitotic neurons, and moderate expression in the spleen, skeletal muscle, and kidneys (2, 11). Other studies have confirmed these observations (12–14).

The binding of MIBP1 to NF-κB-like DNA motifs or TC-rich elements has been proposed by several groups (5–9, 12). Furthermore, it has been suggested that MIBP1 interacts with SMAD1/4 (15). MIBP1 knock-out mice exhibit impairment in the differentiation of T-cells, adipocytes, and osteoblasts/osteoclasts (10, 15–17) or exhibit abnormal behavior, such as hyperactivity (18). However, the mechanism underlying the MIBP1-mediated regulation of genome-wide expression profile remains to be elucidated.

In this study, we characterized the transcriptional targets of MIBP1 using microarray hybridization experiments and identified the genes in the NF-κB pathway as primary targets. Using immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry, we identified O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT) as a major protein that interacts with MIBP1. OGT is a post-translational modification enzyme that adds an O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine monosaccharide to serine or threonine residues of various proteins (19, 20), and we confirmed the O-GlcNAcylation of MIBP1. Using reporter assays, we found that the expression of the NF-κB binding site-containing reporter was reduced by MIBP1 co-transfection and that this reduction was stronger when MIBP1 lacking the OGT binding site was co-transfected.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

The details for several of the plasmids used in this study are depicted in supplemental Fig. S1 and are available upon request. In brief, the full-length rat MIBP1 coding sequence was derived from p111 (2). The N-terminal FLAG-tagged full-length rat MIBP1 coding sequence was inserted into the pCI vector (E1731, Promega, Madison, WI) to generate pCIX-FM. The C-terminal HA-tagged full-length rat MIBP1 coding sequence was inserted into the pCAGGS vector (21) to generate pCAH-MIBP16. The plasmid pCI-neo-FHM was constructed by inserting the N-terminal FLAG-HA-tagged full-length rat MIBP1 coding sequence into the pCI-neo vector (E1841, Promega). The plasmid pCI-neo-FHMΔ154 was constructed by deleting a fragment encoding amino acid residues 1567–1720 from pCI-neo-FHM. The plasmid pCI-neo-FM154 was constructed by inserting the N-terminal FLAG-tagged MIBP1 cDNA sequence encoding amino acid residues 1567–1720 into pCI-neo. The plasmid pGL4.23NF-κBx5 (supplemental Fig. S1) was constructed by inserting a fragment containing five copies of the NF-κB binding site from the rat MHC class I enhancer (gatctGCTGGGGATTCCCCATCTCg) (22) into a firefly luciferase reporter, pGL4.23 (E8411, Promega). All of the constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The TGF-β reporter p3TP-LUX (23) was provided by Joan Massagué at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. The Renilla luciferase reporter pRL-TK was purchased from Promega (E2241). An OGT expression plasmid, pLK61, and its empty vector, pLK26, were provided by Gerald W. Hart at The Johns Hopkins University (24). All of the plasmids were grown in Escherichia coli DH5α cells and prepared with an EndoFree Plasmid Maxi kit (12362, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Cell Culture and Transfection

HEK293 cells were obtained from Clontech; maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (D5796, Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (15140-122, Invitrogen); and incubated with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. HT1080 cells (CCL-121, ATCC, Manassas, VA) were maintained in minimum essential medium Eagle (M5650, Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mm glutamine (G7513, Sigma-Aldrich), and 1 mm sodium pyruvate (S8636, Sigma-Aldrich). The transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (11668-027, Invitrogen) and Opti-MEM (31985-070, Invitrogen).

Establishment of Stable Transformant Cell Lines

HEK293 cells were transfected with pCI-neo-FHM linearized with AclI or with pCI-neo (empty vector control). The cells were selected with 400 μg/ml G418 (345812, Calbiochem) for 2 weeks, cloned using cloning rings, and maintained in the presence of G418. The genomic integration and protein expression of MIBP1 were confirmed by genomic PCR and immunoblotting using an anti-FLAG M2 antibody (F3165, Sigma-Aldrich). The stable transformant cell lines used in this study were cells overexpressing MIBP1 (FHM-31, -49, and -76) or mock controls (neo-3, -6, and -11).

Expression Microarray Analysis

The genome-wide mRNA expression was measured using the GeneChip Human Gene 1.0 ST array (901086, Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) strictly following the manufacturer's instructions (GeneChip Whole Transcript Sense Target Labeling Assay Manual Version 4). The total RNA was extracted from the three cell lines overexpressing MIBP1 or the three control cell lines described above using the RNeasy Plus Mini kit (74134, Qiagen). The RNA quality was verified using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), and the RNA integrity number was 9.4 or greater for all of the samples. The total RNA (200 ng) was amplified and reverse transcribed using GeneChip WT Sense Target Labeling and Control Reagents (900652, Affymetrix). Biotin-labeled and fragmented single-stranded DNAs served as the probes for the hybridization experiments using the GeneChip Human Gene 1.0 ST array as recommended by the manufacturer.

The obtained data (cel files) were summarized and normalized using the robust multiarray average method (25) and Expression Console Software Version 1.1.1 (Affymetrix). The logarithmic signal intensities were antilog-transformed to a linear scale using the Expression Console. Welch's t tests and false discovery rate analyses (26) were performed using JMP 6.0 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). The microarray data discussed in this study have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (27) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE26420.

Gene Set Enrichment Analysis

The GSEA version 2.0 software and a Gene Sets file (c2.v2.5.gmt) were downloaded from the Broad Institute (28). The genes were ranked by their signal-to-noise ratios, which are the differences of the means of the linear signal intensities scaled by their standard deviations. The expression data sets (gct file), phenotype labels (cls file), and chip annotation files (chip file) were created using Microsoft Excel as described in the GSEA User Guide.

Quantitative RT-PCR

The coding sequences of the genes to be examined were retrieved from GenBank using the mRNA IDs, and the primers were designed using Primer3Plus or Primer Express (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) (supplemental Table S1) (29, 30). When possible, the primers were designed to span introns. RT-PCR was performed using a QuantiTect SYBR Green RT-PCR kit (204243, Qiagen) and a StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). Total RNA from stably transfected cells (100 ng) was used in a 20-μl reaction. The specific amplification of the PCR products was routinely confirmed with a melting curve analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis. All of the experiments were performed in triplicate with a no-template control and a no-reverse transcriptase control for each primer set. The relative expression level of each gene was calculated using the ΔΔCt method of the StepOne software. GAPDH was used as an internal control for normalization.

Overrepresentation of Transcription Factor Binding Sites

The overrepresentation analysis was performed using oPOSSUM version 2.0 and Pscan version 1.1 with matrices of vertebrate transcription factor binding sites (31, 32). In the analysis using oPOSSUM, the promoter sequences were from Ensembl release 41, and the matrices were from JASPAR version 3.0 (33). The source code for Pscan was downloaded and compiled using gcc 4.3.4 on cygwin 1.7.1. The background promoter sequences were obtained from the Pscan home page. The vertebrate transcription factor binding sites from JASPAR version 4 (130 matrices) (34) were also downloaded from the same site. Additional vertebrate transcription factor binding sites (881 matrices) were retrieved from Transfac Professional 2009.4 (BIOBASE, Wolfenbüttel, Germany) (35). The gene symbols were transformed to RefSeq IDs using BioMart (36).

siRNA Transfection

The siRNAs used in this study were the BTsiMAX human MIBP1 pool (bt240001, BONAC, Kurume, Japan; hereafter denoted as siMIBP1-B) and the non-targeting RNA (BSN-D5, BONAC; denoted as non-targeting-B). We also used the ON-TARGETplus siRNA pool of Dharmacon (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for human MIBP1 (L-015324-00-0005; denoted as siMIBP1-D), for human OGT (L-019111-00-0005; denoted as siOGT-D), or for the non-targeting pool (D-001810-10-05; denoted as non-targeting-D) (supplemental Table S2). The cells were plated at 6 × 104 cells (HEK293) or 1.5 × 104 cells (HT1080)/well in a 24-well plate and incubated for 24 h before transfection. The siRNA·Lipofectamine 2000 complex (containing 12 pmol of siRNAs and 1 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 in 100 μl of Opti-MEM) was added to 500 μl of cell culture medium (final concentration, 20 nm siRNA) and incubated for 48 h. When indicated, the cells were treated with the vehicle (Opti-MEM) or 10 ng/ml TNF-α (210-TA, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for the final 6 h. The total RNAs were purified using the RNeasy Plus Mini kit and characterized by their absorption spectra.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

Biotinylated or unlabeled oligonucleotides were purchased from Invitrogen or Genenet (Fukuoka, Japan), respectively (supplemental Table S3). The sense and antisense strands, each at 2 μm, were mixed at a 1:1 molar ratio, denatured at 95 °C, and annealed by cooling to 25 °C at 1 °C/min using a thermal cycler. The EBNA-binding oligonucleotide included in the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit (20148, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as an unrelated oligonucleotide. The nuclear protein was extracted from HEK293 cells stably overexpressing MIBP1 or from control cells by NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (78833, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The binding mixture contained (final concentrations) 10 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 50 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 10 μm zinc acetate, 50 ng/μl poly(dI-dC), 1 mm DTT, 2.5% glycerol, and 0.05% Nonidet P-40. Nuclear protein (9 μg) and biotinylated oligonucleotide (80 fmol) were added to 20 μl of the binding mixture and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. The electrophoresis was performed using a 3.6% polyacrylamide gel (29:1 acrylamide:bisacrylamide) containing 2.5% glycerol in 0.5× Tris borate-EDTA buffer at 100 V for 60 min. The resolved oligonucleotide in the gel was electroblotted in a Trans-Blot SD semidry electrophoretic transfer cell (170-3940, Bio-Rad) to a positively charged nylon membrane, Biodyne B (77016, Thermo Fisher Scientific). The biotinylated oligonucleotides were detected using a LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA kit. In the supershift experiment, the anti-rat MIBP1 A-20 antibody (sc-10686, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) and the corresponding peptide (sc-10686P, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) were used.

Immunoprecipitation and Mass Spectrometry

The plasmids used in the experiments are depicted in supplemental Fig. S1. In the transient expression experiments, HEK293 cells (3 × 106 cells/100-mm dish) were transfected with pCIX-FM and lysed after 24 h with 1 ml of lysis buffer (150 mm NaCl, 50 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, and 0.1% protease inhibitor mixture (P8340, Sigma-Aldrich)). Cells transfected with the vector without FLAG tag, pCAH-MIBP16, were processed simultaneously and served as a control. In the stable expression experiments, HEK293 cells transformed with pCI-neo-FHM (FHM-31) (1 × 108 cells) were used, and untransfected HEK293 cells served as a control. The nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared using a modification of the method of Dignam et al. (37) as detailed in the protocol from the Lamond laboratory.3 The lysates were immunoprecipitated using an anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (A2220, Sigma-Aldrich) and eluted with 100 ng/μl FLAG peptide (F3290, Sigma-Aldrich).

Protein identification using mass spectrometry was performed at the Laboratory for Technical Support of the Medical Institute of Bioregulation, Kyushu University. The eluate from the affinity gel was resolved using SDS-PAGE. The gel was then silver-stained. The bands of proteins specific to the FLAG-MIBP1-expressing cells as well as corresponding regions in the control lane were excised, treated with DTT and iodoacetamide, and then in-gel-digested with trypsin. The fragmented peptides were analyzed using an LCQ Deca or LTQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and searched against the NCBI nr database (May 7, 2007 update, mammal, 429,877 sequences) using Mascot version 2.2.1 (Matrix Science, Boston, MA). The mass tolerance was set to 2 Da for precursor ions and 0.8 Da for fragment ions. The carbamidomethylation of cysteine was chosen as the “fixed modification,” and the oxidation of methionine was chosen as the “variable modification.”

The proteins that had at least one unique peptide with a Mascot score greater than 40 were considered to be significant. MIBP1 and its degradation products were identified in several bands but were not considered to be MIBP1-binding proteins. The proteins that were identified in the corresponding regions in the negative control lanes were not regarded to be specific binding proteins. Trypsin, keratin, and albumin were judged to be contaminants.

Immunoblotting

HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with full-length MIBP1 or the deletion mutant constructs for 24 h. The immunoprecipitation was performed using the anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel or the anti-rat MIBP1 A-20 antibody and Protein G on Sepharose 4B Fast Flow beads (P-3296, Sigma-Aldrich). Whole-cell lysates and immunoprecipitates were separated using SDS-PAGE and blotted onto a PVDF membrane (Immobilon-P, IPVH00010, Millipore, Billerica, MA). The membrane was blocked using 5% Chemicon BLOT-QuickBlocker (B2080, Millipore) in 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm Tris-HCl at pH 8.0, and 0.05% Tween 20. For immunoblotting, the anti-FLAG M2 antibody, anti-OGT DM-17 antibody (O6264, Sigma-Aldrich), and anti-O-GlcNAc CTD110.6 antibody (MMS-248R, Covance, Princeton, NJ) were used in addition to the anti-rat MIBP1 A-20 antibody. The chemiluminescent detection was performed using ECL Plus Western Blotting Detection Reagents (RPN2132, GE Healthcare). The knockdown of endogenous MIBP1 or OGT was confirmed by immunoblotting using the anti-human MIBP1 H-20 antibody (sc-10682, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti-OGT antibody, respectively.

Luciferase Assay

Cells (6 × 104 or 1 × 105 cells/well for HEK293 or 1.5 × 104 cells/well for HT1080) were plated in a 24-well plate, incubated for 24 h, and transfected with different combinations of plasmid DNAs and siRNAs. A Renilla luciferase reporter, pRL-TK (40 ng/well), was used as an internal control in all of the experiments. Plasmid pGL4.23-NF-κBx5 or p3TP-LUX (40 ng) with 40 fmol (135–320 ng) of each MIBP1 expression plasmid was used. The plasmid pBluescript was used to adjust the total amount of DNA to 400 ng/well for each transfection. In several experiments, the amount of MIBP1 plasmid decreased to 20 fmol (68–160 ng), and 30 fmol (160 ng) of OGT expression plasmid was added. In the OGT knockdown experiments, 12 pmol (final concentration, 20 nm) of appropriate siRNA was used.

In the analyses using pGL4.23-NF-κBx5, the cells were transfected for 42 h and treated with 10 ng/ml TNF-α for 6 h before the cells were lysed. In the analyses using p3TP-LUX, the cells were transfected, serum-starved for 24 h (0.5% serum), and treated with 400 pm TGF-β (100-B, R&D Systems) for 24 h before being lysed. The luciferase activity was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (E1910, Promega) and a Lumat (LB9501, Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany) or Luminescencer Octa AB-2270 (ATTO Corp., Tokyo, Japan) luminometer according to the manufacturers' instructions. All of the experiments were performed in triplicate transfections. Plasmid DNA from two separate preparations was used to confirm the results.

RESULTS

Transcriptome Analyses of Cells Stably Overexpressing MIBP1

A systematic characterization of the effects of MIBP1 on genome-wide gene expression has never been reported, although several of the transcriptional targets of MIBP1 have been studied using a candidate approach. We compared the genome-wide expression profile of HEK293 cells stably expressing MIBP1 with the profile of control cells using Affymetrix Human Gene ST 1.0 arrays. The resultant logarithmic signal intensities were antilog-transformed to a linear scale, and a Welch's t test and false discovery rate analysis were performed. Of the 28,869 transcripts tested, 821 showed significantly different expression with a p value less than 0.05; however, none of these differences was significant after correcting for multiple comparisons (supplemental Table S4). An analysis using the logarithmic value of the expression data was also performed and showed essentially the same results.

Next, using GSEA, we tested whether any of the gene sets in the curated C2 data set of the Molecular Signature Database (MSigDB version 2.5) were differentially expressed in the presence of MIBP1. These gene sets have been defined as groups of genes that belong to various pathways in established public databases or have been reported to be co-regulated in various biological or clinical states (38). The default GSEA parameters were used. During the analysis, the gene sets were filtered by size (minimum, 15; maximum, 500), which eliminated 756 gene sets, and the remaining 1,136 sets were used in the analysis. The significance was calculated in 1,000 permutations of the gene sets. A false discovery rate of less than 0.05 was considered significant. The GSEA revealed that only one gene set was significantly up-regulated by MIBP1, whereas 383 gene sets were significantly down-regulated (supplemental Table S5). These results suggest that MIBP1 down-regulates genes that are involved in various cellular processes.

In an attempt to narrow the potential transcriptional target genes of MIBP1, we scored the genes based on the number of times they were identified in “leading edge” subsets. Leading edge subsets are the core members of a gene set that contribute to the significance (38). The significantly up- or down-regulated gene sets represent signaling pathways or cellular functions that are affected by MIBP1, and the genes that are frequently identified in the leading edge subsets across different gene sets are likely to be the targets of MIBP1. Only one gene set was up-regulated by MIBP1; therefore, this scoring method was not applied to the up-regulated gene set.

Among the 383 down-regulated gene sets, the 20 genes that were most frequently identified in the leading edge subsets are shown in Table 1 (the full list is in supplemental Table S6). As shown in Table 1, MYC was the most frequently identified gene. This observation indicates that many gene sets containing MYC are significantly down-regulated by MIBP1 (supplemental Table S5). This genome-wide transcriptional regulation is consistent with the previous observation that MIBP1 binds to intron 1 in the rat MYC locus and can repress its expression (2, 11). However, in this study, the down-regulation of MYC was not statistically significant when the array data were evaluated on a single gene basis. Other potential transcriptional targets of MIBP1 include genes involved in the NF-κB pathway (NFKBIA, NFKB1, RELA, and RIPK1) (39) or genes induced by NF-κB (MYC, NFKBIA, NFKB1, CDKN1A, CCND1, SERPINE1, and EGFR). We also observed that several of the down-regulated genes (TGFB1, TGFB2, CDKN1A, SERPINE1, CTGF, and CYR61) are members of the TGF-β pathway (40, 41).

TABLE 1.

Leading edge genes in gene sets significantly down-regulated by MIBP1

Genes in the 383 gene sets significantly down-regulated by MIBP1 (supplemental Table S5) were scored by the number of times they are identified in leading edge subsets. The 20 most frequently identified genes are shown. The full list is presented in supplemental Table S6. -Fold changes were calculated using linear scaled microarray data as the ratio of expression level in cells overexpressing MIBP1 to those in control cells.

| Gene | Number of gene sets identified in leading edge | -Fold change |

|---|---|---|

| MYCa | 62 | 0.76 |

| NFKBIAa | 49 | 0.42 |

| NFKB1 | 45 | 0.70 |

| CDKN1A | 43 | 0.75 |

| RELA | 39 | 0.78 |

| CYR61a | 36 | 0.49 |

| GADD45A | 36 | 0.79 |

| JUN | 35 | 0.82 |

| STAT1 | 35 | 0.66 |

| CTGFa | 35 | 0.50 |

| CCND1 | 35 | 0.65 |

| RIPK1 | 31 | 0.71 |

| SERPINE1a | 31 | 0.48 |

| TGFB2a | 30 | 0.44 |

| IFITM1a | 29 | 0.43 |

| DUSP1 | 28 | 0.60 |

| MAP2K1 | 27 | 0.88 |

| CASP8 | 27 | 0.74 |

| TGFB1a | 27 | 0.46 |

| EGFR | 27 | 0.69 |

a Genes further examined using quantitative RT-PCR.

Quantitative RT-PCR of Leading Edge Genes

Next, we used quantitative RT-PCR to examine the expression of leading edge genes in HEK293 cells that were stably expressing MIBP1. Among the 20 most frequently identified leading edge genes, seven genes were chosen because they showed large -fold changes in expression in the microarray analysis (Table 1). MYC, which was the most frequently identified leading edge gene, was also included. A Welch's t test (two-sided, unpaired, and unequal variance) was used to evaluate the significance of the difference in the ΔCt values. This analysis confirmed that the expression of all eight genes decreased in cells stably expressing MIBP1. Furthermore, the expression of TGFB2, SERPINE1, TGFB1, and NFKBIA was significantly down-regulated (Table 2). In contrast, the top five genes ranked by signal-to-noise ratio in the significantly up-regulated gene set were not significantly increased (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

Repression of TGFB2, SERPINE1, TGFB1, and NFKBIA expression by MIBP1

Quantitative RT-PCR was used to measure the mRNA levels of selected genes that were down-regulated by MIBP1 (Table 1). Total RNA was extracted from HEK293 cells stably transfected with pCI-neo (negative control) or pCI-neo-FHM (MIBP1). The values were normalized to GAPDH expression and are presented as the ΔCt. -Fold change is the mRNA level in cells overexpressing MIBP1 relative to that in control cells and is calculated from −ΔΔCt. S.E. indicates standard error (n = 3).

| Gene | ΔCt |

−ΔΔCt | -Fold change | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control |

MIBP1 |

||||||

| Mean | S.E. | Mean | S.E. | ||||

| TGFB2 | 2.34 | 0.13 | 3.75 | 0.13 | −1.42 | 0.37 | 0.0015a |

| SERPINE1 | 7.61 | 0.17 | 9.26 | 0.14 | −1.65 | 0.32 | 0.0018a |

| TGFB1 | 2.61 | 0.20 | 3.70 | 0.13 | −1.09 | 0.47 | 0.0138a |

| NFKBIA | 6.68 | 0.19 | 7.82 | 0.08 | −1.15 | 0.45 | 0.0151a |

| CYR61 | 3.38 | 0.04 | 4.76 | 0.35 | −1.38 | 0.38 | 0.0561 |

| CTGF | 1.56 | 0.11 | 3.20 | 0.52 | −1.64 | 0.32 | 0.0821 |

| IFITM1 | 9.94 | 1.58 | 11.47 | 0.34 | −1.53 | 0.35 | 0.4372 |

| MYC | 8.25 | 0.25 | 8.51 | 0.32 | −0.26 | 0.83 | 0.5529 |

a Indicates a p value less than 0.05 (two-sided Welch's t test).

Overrepresentation of NF-κB/REL Binding Sites in Promoter Regions

To identify the cis-elements participating in the genome-wide repression of several gene pathways by MIBP1, we used two motif analysis programs, oPOSSUM (31) and Pscan (32). The oPOSSUM program scans conserved segments in the promoter regions of the chosen genes. In this study, the regions 5,000 bp upstream and downstream of the transcriptional start sites in the top 100 genes down-regulated by MIBP1 were examined (supplemental Table S7). The significance threshold was set to 10 for the Z-score and 0.01 for the Fisher p value as recommended by the developers of oPOSSUM. Among the 79 transcription factor binding sites examined by oPOSSUM, the NF-κB/REL binding sites were the most significantly overrepresented (Table 3). This finding suggests that MIBP1 represses transcription through the NF-κB binding sites in target genes.

TABLE 3.

Overrepresentation of transcription factor binding sites in promoter regions of genes down-regulated by MIBP1

Of the top 100 genes down-regulated by MIBP1 (supplemental Table S7), 77 were in the oPOSSUM database. The enrichment of conserved transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) in the region 5000 bp upstream and downstream of the transcription start site relative to background genes was evaluated by their hits and non-hits (presence and absence) or the TFBS occupancy rate, which is the rate of nucleotide occupation by the TFBS in the background (23 Mb) or target (0.18 Mb) region. The transcription factors determined to be significant in Fisher's test (p < 0.01) of hits/non-hits and in Z-score (Z > 10) of TFBS occupancy rate are listed.

| Transcription factor | Hits/non-hits |

TFBS occupancy rate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Background (15,150 genes) | Target (77 genes) | Fisher's exact test p value | Background (23 Mb) | Target (0.18 Mb) | Z-score | |

| RELAa | 4,846/10,304 | 48/29 | 4.80e−8 | 0.0035 | 0.0063 | 20.41 |

| NF-κBa | 5,960/9,190 | 52/25 | 5.65e−7 | 0.0050 | 0.0073 | 13.95 |

| TLX1-NFIC | 811/14,339 | 16/61 | 2.99e−6 | 0.0005 | 0.0013 | 13.30 |

| MZF1_1–4 | 13,090/2,060 | 77/0 | 1.34e−5 | 0.0419 | 0.0481 | 13.13 |

| RELa | 7,798/7,352 | 58/19 | 1.60e−5 | 0.0081 | 0.0118 | 17.46 |

| SP1 | 9,192/5,958 | 64/13 | 1.90e−5 | 0.0158 | 0.0199 | 13.98 |

| ARNTa | 8,733/6,417 | 62/15 | 1.99e−5 | 0.0066 | 0.0086 | 10.07 |

| MAXa | 6,215/8,935 | 50/27 | 2.07e−5 | 0.0051 | 0.0074 | 13.30 |

| TEAD1 | 3,743/11,407 | 35/42 | 6.24e−5 | 0.0028 | 0.0046 | 13.74 |

| USF1a | 8,353/6,797 | 59/18 | 7.93e−5 | 0.0068 | 0.0089 | 10.67 |

| SRF | 713/14,437 | 10/67 | 3.38e−3 | 0.0004 | 0.0014 | 20.91 |

a Transcription factors discussed in the text.

Interestingly, MYC-related E-box sequences, such as the binding sites of MAX (JASPAR ID MA0058.1), ARNT (MA0004.1), and USF1 (MA0093.1), were also overrepresented. However, MYC-MAX (MA0059.1) was not significantly overrepresented. Perhaps broadly defining the MYC-MAX binding site matrix contributed to the failure to reach significance in this search. Because MYC can bind these overrepresented E-box sequences and was the most frequently identified gene in the leading edge analyses, we assume that the repression of MYC resulted in the down-regulation of many genes.

Motifs related to SMADs, which are transcription factors that are downstream of TGF-β signaling, were not in the oPOSSUM list and were not tested by this program. Therefore, we used Pscan to examine the promoter regions of the MIBP1-down-regulated genes for additional enriched motifs. Pscan calculates the overrepresentation of transcription factor binding sites in gene promoters using a library of matrices that can be designed by the user. Other differences between the two programs have been discussed previously (32). We prepared a library of matrices by incorporating information from the JASPAR version 4 and Transfac Professional 2009.4 databases, including SMAD binding sites. In the Pscan analysis, a region spanning 450 bp upstream and 50 bp downstream of the transcription start site for each of the same 100 genes (down-regulated by MIBP1) used in the oPOSSUM analysis was examined. The significance threshold was set to 4.9 × 10−5 based on the number of matrices tested (n = 1,011).

As a positive control, we used Pscan to examine the promoter regions of known NF-κB target genes (42) and confirmed the overrepresentation of NF-κB binding sites (supplemental Table S8). The Pscan analysis also demonstrated that all of the significantly overrepresented known binding sites in the promoter regions of the genes down-regulated by MIBP1 were the sites related to NF-κB (lowest p value = 1.7 × 10−8 for V$P50RELAP65_Q5_01) (supplemental Table S8). Several of the NF-κB sites (e.g. V$NFKAPPAB65_01) were highly overrepresented in previously defined NF-κB targets (42) but only moderately overrepresented in the MIBP1 targets characterized in this study (supplemental Table S7), suggesting that the target spectra of these two transcription factors are not exactly the same (supplemental Table S8). Several of the SMAD binding sites were also overrepresented but did not reach significant levels after correcting for multiple comparisons (lowest p value = 0.06 for V$SMAD_Q6_01). These two motif analyses suggest that the binding of MIBP1 to NF-κB binding sites is likely to be a major mechanism for the down-regulation of target genes and that the reduced expression of genes in the TGF-β pathway may be the result of the downstream effects of the repression of the NF-κB pathway.

Effects of Endogenous MIBP1 Knockdown

We next analyzed the effects of the knockdown of endogenous MIBP1 by siRNA transfection on the expression of putative MIBP1 targets. We used siRNA pools from two sources, siMIBP1-B and siMIBP1-D, for MIBP1 knockdown to minimize the risk of misinterpretation due to off-target effects (supplemental Table S2). The targets to be examined by quantitative PCR were selected from the genes shown to be down-regulated by GSEA when MIBP1 was stably overexpressed (Table 1). In addition, genes (CD44 and TNC) that were known to be NF-κB targets and that were highly repressed by stable MIBP1 overexpression (ranked within the top 100 in -fold changes according to the array experiments) were examined. We used HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cells, expecting that the effects of MIBP1 knockdown should be more clearly detected in these cells in which endogenous MIBP1 expression has been shown to be high (13). We confirmed that the endogenous MIBP1 protein was effectively knocked down in these cells (supplemental Fig. S2).

Forty-eight hours after the transfection with siMIBP1-B, the endogenous MIBP1 mRNA was decreased to 26%, and the endogenous expression of the known NF-κB targets, i.e. NFKBIA, MYC, and TNC, was significantly up-regulated (Table 4). Thus, the effects of MIBP1 on the NF-κB target genes observed in the stable overexpression experiments were confirmed.

TABLE 4.

Effects of MIBP1 knockdown on expression of various genes

HT1080 cells were transfected with siMIBP1-B (MIBP1 knockdown) or non-targeting-B (negative control) for 48 h. mRNA levels of MIBP1 and its putative targets (selected as described in the main text) were measured by quantitative RT-PCR. The values were normalized to GAPDH expression and presented as the ΔCt. -Fold change is the mRNA level in cells transfected with siMIBP1-B relative to that in control cells and is calculated from −ΔΔCt. S.E. indicates standard error (n = 3).

| Gene | ΔCt |

−ΔΔCt | -Fold change | p value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative control |

MIBP1 knockdown |

||||||

| Mean | S.E. | Mean | S.E. | ||||

| MIBP1 | 7.35 | 0.05 | 9.27 | 0.03 | −1.92 | 0.26 | 1.6e−5a |

| CTGF | 1.94 | 0.06 | 3.24 | 0.05 | −1.30 | 0.41 | 7.7e−5a |

| NFKBIA | 9.39 | 0.05 | 8.22 | 0.07 | 1.17 | 2.25 | 2.5e−4a |

| SERPINE1 | 0.56 | 0.02 | 1.03 | 0.01 | −0.48 | 0.72 | 6.5e−4a |

| TNC | 7.28 | 0.04 | 6.59 | 0.05 | 0.68 | 1.61 | 7.0e−4a |

| CD44 | 2.36 | 0.01 | 2.50 | 0.01 | −0.14 | 0.91 | 1.8e−3a |

| MYC | 6.35 | 0.04 | 6.00 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 1.28 | 2.3e−3a |

| TGFB2 | 6.64 | 0.09 | 7.00 | 0.05 | −0.35 | 0.78 | 3.6e−2a |

| TGFB1 | 2.00 | 0.10 | 2.24 | 0.03 | −0.24 | 0.85 | 1.2e−1 |

| IFITM1 | 8.03 | 0.17 | 8.12 | 0.05 | −0.08 | 0.94 | 6.8e−1 |

| CYR61 | 3.08 | 0.14 | 3.11 | 0.02 | −0.03 | 0.98 | 8.4e−1 |

a Indicates a p value less than 0.05 (two-sided Welch's t test).

Next, we examined the effects of MIBP1 knockdown when cells were treated with TNF-α. The up-regulation of MYC and TNC by MIBP1 knockdown was also observed in this condition (supplemental Table S9). However, the effect of MIBP1 knockdown was unclear for NFKBIA expression (supplemental Table S9). We believe that the excessive activation of the NF-κB pathway by the TNF-α treatment had hindered the effects of MIBP1 knockdown for certain targets (supplemental Table S10). The transfection of siMIBP1-D also successfully decreased the MIBP1 expression and tended to increase the expression of NFKBIA, MYC, and TNC, although some of these increases were not significant (supplemental Tables S11 and S12). These results are consistent with the idea that MIBP1 is a down-regulator of the genes in the NF-κB pathway. In contrast, the expression levels of members of the TGF-β signaling pathway (CTGF, SERPINE1, TGFB1, and TGFB2) were significantly down-regulated by MIBP1 knockdown (Tables 4 and supplemental Table S9). This result was contrary to the expectation from the stable MIBP1 overexpression experiments in which the genes in the TGF-β signaling pathway were repressed by MIBP1. Thus, we presume that the repression of the genes in the TGF-β signaling pathway observed in cells stably overexpressing MIBP1 was an indirect consequence.

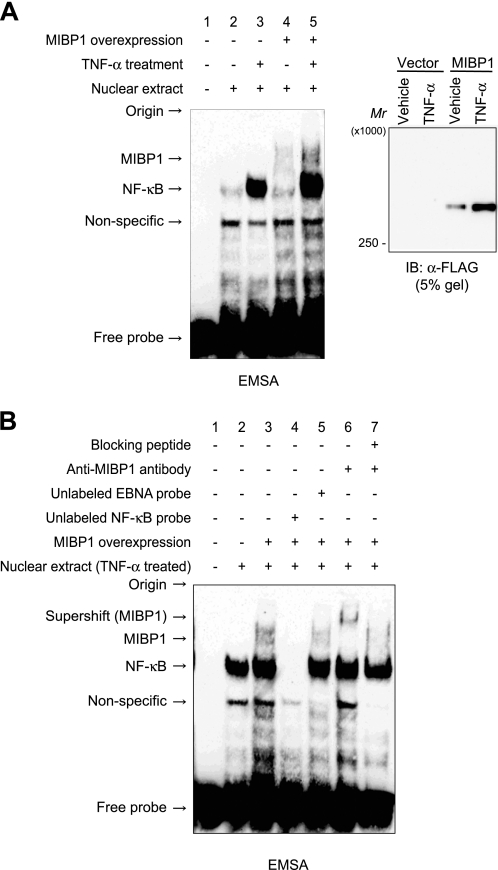

DNA Binding of MIBP1 Protein

The binding of the MIBP1 protein to an NF-κB binding sequence was shown by EMSA of a nuclear extract obtained from HEK293 cells grown in various conditions. In these analyses, the NF-κB·probe complex was observed as a band that increased after TNF-α treatment (Fig. 1A, lanes 2 and 3). The MIBP1·probe complex was seen as a slowly migrating band that was detected specifically in the cells overexpressing MIBP1 (Fig. 1A, lane 4). The complex was increased by TNF-α treatment (Fig. 1A, lane 5) probably because the CMV promoter used to overexpress MIBP1 was responsive to TNF-α (Fig. 1A, IB: α-FLAG). The shifted bands (Fig. 1B, lane 3, marked by arrows as MIBP1 and NF-κB) disappeared with the addition of excess unlabeled NF-κB binding sequence but not unrelated EBNA binding sequence (Fig. 1B, lanes 4 and 5). The supershift of the MIBP1-specific band by an anti-rat MIBP1 antibody and the inhibition of the supershift by the addition of an antigen peptide specific for the antibody (Fig. 1B, lanes 6 and 7) confirmed that the observed slowly migrating band was that of the MIBP1·probe complex. These results suggest the possibility that the repression of NF-κB target genes by MIBP1 is mediated by the competitive binding of the MIBP1 protein to NF-κB binding sites in the cis-regulatory elements of the target genes. The competition between NF-κB and MIBP1 was not observed because of the nature of EMSA experiments in which excess amount of probes were obligatorily used.

FIGURE 1.

DNA binding of MIBP1 protein. A, HEK293 cells stably overexpressing MIBP1 (lanes 4 and 5) or control HEK293 cells (lanes 2 and 3) were treated with vehicle (lanes 2 and 4) or 10 ng/ml TNF-α (lanes 3 and 5). Nuclear extracts of these cells were incubated with biotinylated oligonucleotide containing an NF-κB binding sequence in the binding condition and separated in a 3.6% gel as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Nuclear extracts were also immunoblotted (IB) using 5% SDS-PAGE and detected by anti-FLAG antibody to confirm the overexpression of MIBP1 protein. B, nuclear extracts from HEK293 cells treated with TNF-α were incubated with biotinylated NF-κB-binding oligonucleotide. Excess unlabeled NF-κB (lane 4) or EBNA-binding oligonucleotide (lane 5) was added to the DNA-protein mixture. Anti-rat MIBP1 antibody (lane 6) and specific antigen peptide for the antibody (lane 7) were also added to confirm the specificity of shifted band.

Identification of MIBP1-binding Proteins

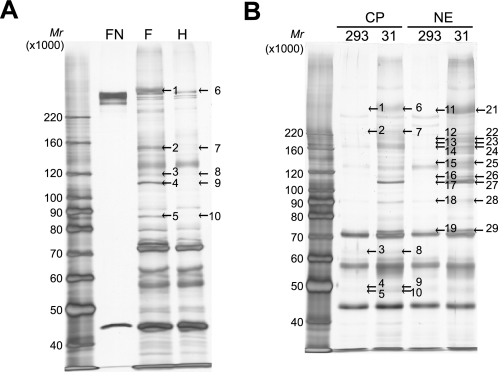

To identify regulatory cofactors of MIBP1, we screened for proteins that bind MIBP1 using immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry. FLAG-tagged MIBP1 was immunoprecipitated from lysates prepared from HEK293 cells transiently transfected with pCIX-FM (FLAG-tagged rat full-length MIBP1) and resolved by SDS-PAGE. The proteins that were detected specifically in cells expressing FLAG-tagged MIBP1 were judged to be candidate binding partners of MIBP1. Although no bands of MIBP1-binding proteins were recognizable at a molecular weight of less than 50,000 in the 4–20% gradient gel (supplemental Fig. S3), at least five bands specific to the expression of FLAG-tagged MIBP1 were detected in the 7.5% gel (Fig. 2A and supplemental Table S13). Using mass spectrometry, we determined that the bands designated as 1, 2, and 4 in Fig. 2A were full-length MIBP1, degraded MIBP1, and OGT, respectively. Band 3 was not identifiable (contained only keratin and trypsin as identifiable proteins), and band 5 was XRCC5, which we considered to be a contaminant because it has been shown to bind nonspecifically to Sepharose beads (43).

FIGURE 2.

Preparative immunoprecipitation of MIBP1-binding proteins for mass spectrometry. A, lysates from HEK293 cells transfected with pCIX-FM (lane F) or pCAH-MIBP16 (lane H) were immunoprecipitated with the anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel. The precipitated proteins were resolved by 7.5% SDS-PAGE and silver-stained. The arrows with numbers indicate the positions of the bands that were excised for enzymatic digestion and subsequent analysis using an LCQ Deca mass spectrometer. The numbered bands were identified as follows: 1, MIBP1; 2, MIBP1; 3, not identifiable; 4, OGT; and 5, XRCC5. Detailed data from the mass spectrometry analyses are shown in supplemental Table S13. Recombinant human fibronectin (lane FN) was used as a positive control for protein identification by mass spectrometry. B, nuclear (NE) and cytoplasmic (CP) fractions were prepared from HEK293 cells stably transfected with pCI-neo-FHM (lane 31) or untransfected HEK293 cells (lane 293) and immunoprecipitated with the anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel. Precipitated proteins were resolved by 7.5% SDS-PAGE and silver-stained. Protein identification was performed using an LTQ mass spectrometer. The numbered bands were identified as follows: 6, EML6, MIBP1, ubiquitin, and DSP; 7, MIBP1 and DSP; 8, FBXW11; 9, WDR77, TTN, STK38, and TRIM21; 10, TRIM21; 21, MIBP1 and ubiquitin; 22, OGT, MIBP1, and ubiquitin; 23, GLDC, MIBP1, and S100A8; 24, MIBP1 and ubiquitin; 25, MIBP1, HRNR, DSG1, and DSP; 26, OGT, IPO8, CRYAA, ubiquitin, and MIBP1; 27, OGT, POLG2, MIBP1, and LIMA1; 28, CUL1 and MIBP1; and 29, OGT and PRMT5. Detailed data from the mass spectrometry analyses are shown in supplemental Table S14.

Next, the cell lysates of a HEK293 clone (FHM-31) stably overexpressing MIBP1 were separated into nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions and examined by immunoprecipitation and mass spectrometry. Cytoplasmic bands 6–10 and nuclear bands 21–29 in the 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel appeared to be specific to MIBP1 overexpression (Fig. 2B and supplemental Table S14). More proteins were identified in the stable expression experiments than in the transient expression experiments. This difference is likely due to using a larger amount of cells and a more sensitive LTQ mass spectrometer. The results indicated that MIBP1 was localized primarily to the nucleus and that OGT, CUL1, FBXW11, and several other proteins appeared to be MIBP1-binding proteins. Several of the identified proteins were judged to be contaminants for the following reasons. 1) They are known to bind nonspecifically to the FLAG antibody (TRIM21, WDR77, PRMT5, and STK38) or Sepharose beads (DSP, LIMA1, TRIM21, and ubiquitin) (43, 44). 2) They were commonly appearing contaminants in the 766 protein fractions that were purified by tandem affinity chromatography (HRNR, LIMA1, S100A8, DSG1, DSP, and ubiquitin) (45). 3) A large protein size increases the likelihood of false identification (TTN) (46). We focused on the interaction between MIBP1 and OGT because this interaction was the most prominent in the silver-stained gels and because OGT had the highest Mascot score except for MIBP1 itself (Fig. 2, A and B, and supplemental Tables S13 and S14), indicating a high confidence in the correct identification. Furthermore, this interaction was reproducible in cells both transiently and stably overexpressing MIBP1 (Fig. 2, A, band 4, and B, band 27).

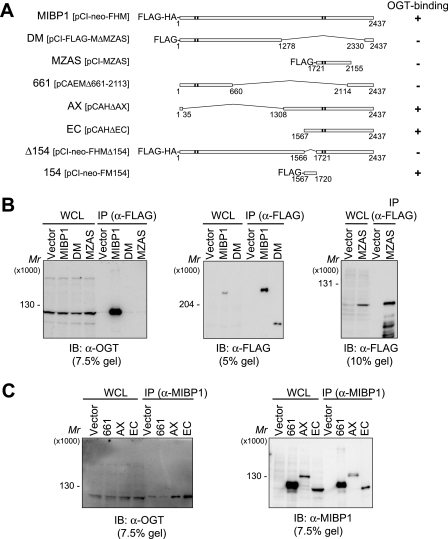

OGT-MIBP1 Interaction and O-GlcNAcylation of MIBP1

We narrowed the region of MIBP1 involved in OGT binding by examining extracts of HEK293 cells transiently transfected with various deletion mutants of MIBP1 (Fig. 3A). As the expressed proteins had sizes of widely different ranges, immunoblotting experiments were performed using gels of different concentrations. FLAG-tagged full-length MIBP1 was immunoprecipitated with an anti-FLAG antibody or an anti-rat MIBP1 antibody. In both immunoprecipitations, MIBP1 overexpression was confirmed by immunoblotting with the anti-FLAG antibody or the anti-rat MIBP1 antibody (Fig. 3B and supplemental Fig. S4). The association of OGT with MIBP1 was demonstrated by immunoblotting the same immunoprecipitates with an anti-OGT antibody (Fig. 3B and supplemental Fig. S4). The results using five deletion mutants of MIBP1 narrowed the OGT-binding region to a 154-amino acid region (amino acids 1567–1720) (Fig. 3 and supplemental Fig. S4). Furthermore, OGT could be co-precipitated with the 154-amino acid region alone but not with the deletion mutant lacking this 154-amino acid region (Fig. 4A). This evidence confirms that the 154-amino acid region is necessary and sufficient for MIBP1 binding to OGT. A sequence analysis of the 154-amino acid region using the PROSITE database did not identify any known motifs (47).

FIGURE 3.

Binding of MIBP1 with OGT. A, schematic diagram of full-length MIBP1 and its deletion mutants. The names of the respective expression plasmids are indicated in brackets. Black boxes indicate C2H2-type zinc fingers. The results of an OGT binding test using immunoblots are shown in the right column. B and C, lysates from HEK293 cells transfected with full-length MIBP1 or deletion mutants were immunoprecipitated (IP) by anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (B) or anti-rat MIBP1 antibody (C) and immunoblotted (IB) with anti-OGT antibody, anti-FLAG antibody, or anti-MIBP1 antibody, respectively, as indicated in the figures. WCL, whole-cell lysates.

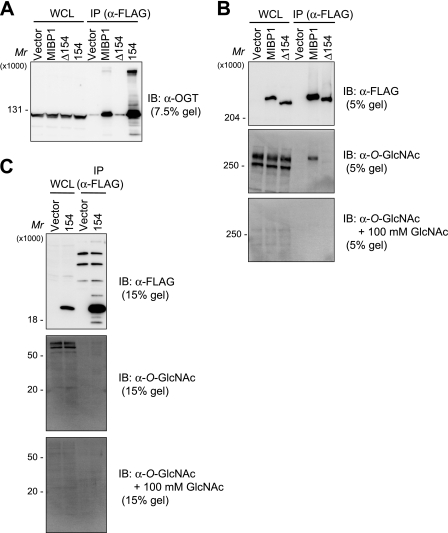

FIGURE 4.

154-amino acid region of MIBP1 required for OGT binding/O-GlcNAcylation. A–C, lysates from HEK293 cells transfected with full-length MIBP1, Δ154, or 154 were immunoprecipitated (IP) by anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel and immunoblotted (IB) with anti-OGT antibody, anti-FLAG antibody, or anti-O-GlcNAc antibody as indicated in the figures. The reactivity of anti-O-GlcNAc antibody was blocked by preincubating with 100 mm GlcNAc (B and C). WCL, whole-cell lysates.

To examine whether MIBP1 was O-GlcNAcylated by OGT, we immunoprecipitated MIBP1 and immunoblotted it with an anti-O-GlcNAc antibody. An O-GlcNAc-reactive band at a high molecular weight was detected in the immunoprecipitate from cells overexpressing full-length MIBP1 but not in the immunoprecipitate from cells overexpressing the deletion mutant lacking the 154-amino acid OGT-binding region (Fig. 4B). The specific detection of O-GlcNAcylation was supported by the inhibition of these signals through the preincubation of the antibody with 100 mm GlcNAc. The immunoprecipitated 154-amino acid peptide was not detected by the anti-O-GlcNAc antibody, although several proteins observed in a molecular weight range greater than 50,000 were detected by the antibody (Fig. 4C). From these results, we conclude that MIBP1 is O-GlcNAcylatable and that the 154-amino acid region alone is necessary and sufficient for OGT binding but is not O-GlcNAcylatable.

Transcriptional Activity of MIBP1 and Its Modulation by OGT Binding/O-GlcNAcylation

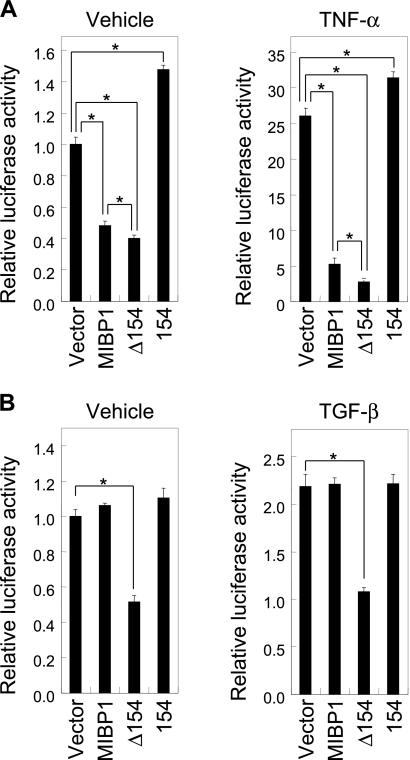

The transcriptome analyses detailed above suggest that the NF-κB and TGF-β pathways are potential targets of MIBP1. Therefore, we performed a luciferase assay using the lysates of cells co-transfected with reporter constructs and MIBP1 or its derivatives to identify direct transcriptional targets of MIBP1. First, we constructed a reporter plasmid that carried the luciferase gene under the control of five copies of the NF-κB binding site from the rat MHC class I gene. The luciferase assay confirmed that full-length MIBP1 repressed expression from this construct (Fig. 5A). A much stronger inhibition by MIBP1 was observed when the cells were treated with TNF-α, which is known to activate NF-κB-dependent transcription, suggesting that at least part of the repression by MIBP1 was through the NF-κB binding sites.

FIGURE 5.

Transcriptional activity of MIBP1 and its modulation by OGT binding/O-GlcNAcylation. A, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with pGL4.23-NF-κBx5, pRL-TK, and full-length MIBP1 or the deletion mutants and incubated for 42 h. The cells were treated with the vehicle (left) or 10 ng/ml TNF-α (right) for 6 h before the cells were lysed. B, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with p3TP-LUX, pRL-TK, and full-length MIBP1 or the deletion mutants and cultured for 24 h with serum starvation. The cells were treated with the vehicle (left) or 400 pm TGF-β (right) for 24 h before the cells were lysed. In both A and B, luciferase expression was measured using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System. All experiments were performed in triplicate transfections. The values were normalized to Renilla luciferase expression and are presented as relative luciferase activity. The error bars indicate S.E. (n = 3). The effect of expression of MIBP1 or the deletion mutants on luciferase activities was evaluated by Welch's t test between the mock transfectant and the transfectant of each expression plasmid. Cells transfected with MIBP1 were also compared with cells transfected with Δ154. The asterisks indicate a p value less than 0.05.

We also observed that the repression of NF-κB promoter activity by the MIBP1 mutant lacking the 154-amino acid region necessary for interaction with OGT was significantly stronger compared with full-length MIBP1. This difference was further enhanced when the cells were treated with TNF-α. Importantly, these effects were confirmed in experiments using different batches of plasmids. Based on these results, we propose that MIBP1 acts as a repressor of NF-κB-responsive promoters and that this activity is modulated by OGT binding and/or O-GlcNAcylation. We found that the expression of the 154-amino acid region alone weakly activated the NF-κB reporter expression possibly because of dominant negative effects of this region as discussed later.

Using the p3TP-LUX reporter, we next investigated the effects of MIBP1 expression on TGF-β signaling (23). This reporter has 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate response elements and a partial SERPINE1 promoter that carries a SMAD-binding element. Transient transfection with full-length MIBP1 did not repress reporter gene expression from p3TP-LUX in HEK293 cells (Fig. 5B). TGF-β treatment enhanced reporter expression ∼2-fold, but full-length MIBP1 did not affect the expression. Based on these results, we conclude that the MIBP1-dependent repression of the TGF-β pathway is an indirect downstream effect of the strong repression of NF-κB-dependent transcription (see “Discussion”). However, it is unclear why the Δ154 mutant reduced reporter transcription, whereas full-length MIBP1 did not.

In an attempt to further examine the effect of OGT expression on MIBP1 transcriptional activity, we conducted OGT knockdown experiments using an siRNA pool for human OGT. OGT mRNA was reduced to 13% both in HEK293 cells and HT1080 cells by the transfection of siRNA as revealed by quantitative RT-PCR. The reduction of OGT protein in HEK293 cells was also confirmed by immunoblotting (supplemental Fig. S5). We then examined the effects of this knockdown on the NF-κB reporter. When cells were transfected with non-targeting siRNA, we observed that full-length MIBP1 and Δ154 significantly repressed the expression of the NF-κB reporter (supplemental Fig. S6), confirming the results described above (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, however, OGT knockdown resulted in NF-κB reporter activation in the cells treated with TNF-α, which was contrary to the expected result if the action of OGT is solely through the attenuation of MIBP1 (supplemental Fig. S6). Perhaps, the O-GlcNAcylation of proteins other than MIBP1 had greater effects on the expression of the NF-κB reporter as discussed later.

We also tried to examine the effects of OGT overexpression on the function of MIBP1 as a transcription factor. However, the difference in OGT expression between cells transfected with the empty vector and OGT vector was small probably due to the already high level of expression of endogenous OGT in the HEK293 cells in our culture conditions (supplemental Fig. S7), and the effect of the overexpression of OGT on the repressive activity of MIBP1 measured by the reporter assay was also subtle (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Target Genes Regulated by MIBP1

In this study, we evaluated the effects of MIBP1 overexpression on the genome-wide expression profile using microarray hybridization. In general, it is difficult to detect changes in the expression of target genes following the transient expression of a transcription factor because the transfection efficiency is usually not known. This uncertainty is especially relevant for the quantification of down-regulation. Therefore, we established a stable cell line in which MIBP1 is expressed in every cell to accurately detect changes in transcription using microarray analysis, and we found that MIBP1 significantly down-regulated gene sets that are involved in the MYC, NF-κB, and TGF-β pathways. An overrepresentation analysis of transcription factor binding sites revealed that the binding site of NF-κB was the most overrepresented in the promoters of the down-regulated genes. The regulation of NF-κB target genes by MIBP1 is also supported by EMSA experiments in which MIBP1 protein binds to oligonucleotides containing the NF-κB binding site.

The disadvantage of using a stable overexpression system in the study of the function of the transcription factor is that it is difficult to distinguish between direct and indirect effects. The system also suffers from the fact that the effects observed under an unnaturally high level of expression may not be biologically significant. Therefore, we also used an siRNA system in which endogenous MIBP1 expression was specifically knocked down. We observed the enhanced expression of three NF-κB targets (NFKBIA, MYC, and TNC) due to MIBP1 knockdown. These results confirmed that the repression of NF-κB targets is the primary function of MIBP1. Among the examined NF-κB targets, CD44 was not up-regulated by MIBP1 knockdown. Thus, the target spectrum of MIBP1 may not be exactly the same as that of NF-κB. The difference in the target spectra was also shown by overrepresentation analysis (supplemental Table S8). The knockdown experiments also showed that the expression of many of the TGF-β signaling pathway members was decreased by lowered levels of MIBP1 (Table 4). These results are consistent with a recent report of CLIC4·MIBP1 complex formation and the subsequent nuclear translocation of CLIC4, leading to activation of the TGF-β signaling pathway by MIBP1 (48). However, these observations are contrary to the results of our array experiments in which gene sets of TGF-β pathways were down-regulated when MIBP1 was stably overexpressed. We assume that the down-regulation of TGF-β pathways observed in the stable transformation experiments is a secondary effect.

Co-transfection experiments using luciferase reporter plasmids further confirmed that MIBP1 represses an NF-κB-responsive reporter but not a TGF-β-responsive reporter. Based on these results, we conclude that MIBP1 down-regulates many genes that are directly regulated by NF-κB and that genes involved in other pathways, such as TGF-β, are repressed as secondary effects of NF-κB repression.

MIBP1 Binding to OGT and O-GlcNAcylation

The highly sensitive identification of protein species by mass spectrometry allowed us to identify proteins that bind to MIBP1. Truncated MIBP1 had been used in previous binding studies (11). In this study, we expressed an epitope-tagged full-length MIBP1 and found that the most prominent binding partner of MIBP1 was OGT. The 154-amino acid OGT-binding region (amino acids 1567–1720) identified in this study is upstream of the C-terminal double zinc finger of MIBP1. Because the 154-amino acid region alone was not O-GlcNAcylated, the target of this modification is likely to be located in the surrounding regions. One possible target site is Ser-1271, which has been recently identified as being O-GlcNAcylated according to a proteome analysis of murine brain synaptosomes (49).

The involvement of OGT in the modulation of the transcriptional activity of MIBP1 was indicated by the luciferase assays where Δ154, the deletion mutant of MIBP1 lacking the OGT-binding domain, showed significantly enhanced repressive action. However, the identification of which of the two processes (OGT binding or O-GlcNAcylation) has functional significance needs to be clarified by further study. OGT has also been reported to be a component of a repressor complex containing mSin3A, MeCP2, and HDAC1 (50). Thus, it is possible that MIBP1 is also a member of the repressor complex. However, we believe it is unlikely that this repressor complex contributes to the MIBP1-mediated transcriptional repression shown here as Δ154 can still repress the expression of the NF-κB-responsive reporter (Fig. 5A).

Interestingly, the 154-amino acid region alone significantly activated the NF-κB-responsive reporter. It is tempting to speculate that this region may act as a dominant negative inhibitor of OGT and may inhibit the function of the repressor complex described above.

To further investigate the effect of OGT on MIBP function, we conducted OGT knockdown experiments. OGT knockdown resulted in enhanced NF-κB reporter activation, especially under stimulation by TNF-α. These observations were contrary to the expected result if the action of OGT on the reporter is solely through the attenuation of MIBP1 (supplemental Fig. S6). We assumed that the action of OGT on proteins other than MIBP1 had greater effects on the expression of the NF-κB reporter. Supporting this assumption, OGT has been reported to modify many proteins in transcriptional machineries, including those in the NF-κB pathway (19, 20), and the involvement of OGT in NF-κB signaling is often complicated, depending on study design (51–54). Thus, an OGT knockdown experiment is inappropriate for proving the role of OGT in the MIBP1-mediated transcriptional regulation of the NF-κB reporter. We also failed to analyze the effect of OGT on the repressive activity of MIBP1 using OGT overexpression experiments likely due to the abundant expression of this protein even before forced expression.

Another possible interplay between MIBP1 and OGT is indicated by the report that both were components of the FBXW11/β-TrCP2 and BTRC/β-TrCP1 protein complexes, which may be involved in the ubiquitination process (55). Our protein interaction results also showed an interaction of MIBP1 with E3 ubiquitin ligase components, namely CUL1 and FBXW11/β-TrCP2 (56). Both MIBP1 (amino acids 397–402) and HIVEP1 (amino acids 667–672) have a DSGXXS sequence, which is required for recognition by the SCFβ-TrCP ubiquitin ligase. These findings suggest that ubiquitin ligase and OGT may be involved in the metabolism of MIBP1, although our data have not shown a difference in stability between MIBP1 and Δ154.

Biological Role of MIBP1

Our study demonstrated that MIBP1 primarily modulates NF-κB pathway through binding to NF-κB sites. This conclusion is consistent with previous studies that zinc fingers conserved among MIBP1 and its homologues bind to NF-κB-like DNA motifs in vitro (2, 4, 5). We also found that endogenous MIBP1 is significantly up-regulated by TNF-α treatment (supplemental Table S10). Thus, it is possible that MIBP1 is a component of a negative feedback loop in the NF-κB pathway.

We asked whether various reported phenotypes of MIBP1 knock-out (Shn-2−/−) mice could be accounted for by the relief of MIBP1-dependent repression of NF-κB activities. In CD4 T-cells in MIBP1 knock-out (Shn-2−/−) mice, constitutive activation of NF-κB and enhanced differentiation to Th2 cells were reported by Kimura et al. (16). Their study is consistent with our interpretation that the primary function of MIBP1 in this differentiation process is NF-κB repression. Staton et al. (57) reported that CD4+CD8+ double-positive thymocytes from Shn-2−/− mice are sensitive to T-cell antigen receptor-induced cell death. However, they did not detect constitutive activation of NF-κB in these cells. Perhaps, MIBP1-dependent NF-κB repression at limited stages of T-cell differentiation may be acting as a determinant of the cell fate.

Altered phenotypes of other cell types, such as adipocytes or osteoblasts/osteoclasts, in MIBP1 knock-out mice were interpreted to be the results of the impaired activity of the bone morphogenetic protein/Smad pathways (15, 17). This interpretation is likely based on MIBP1 being thought to be the mammalian homologue of Drosophila Schnurri, which has been established to be involved in the bone morphogenetic protein/Smad pathways during Drosophila development (58). Notably, the activation of the NF-κB pathway has been shown to decrease the DNA binding of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, a key regulator of adipogenesis (59). Therefore, the impaired adipogenesis in the knock-out mice can also be explained by increased NF-κB pathway activity because of the lack of MIBP1. Osteogenesis is also known to be under the influence of NF-κB function (60).

We previously detected high MIBP1 expression in the brain, especially during perinatal development, and assumed that MIBP1 plays a role in neuronal development (2, 61). Consistent with this observation, a recent report demonstrated that MIBP1 knock-out mice showed behavioral alterations (18). High OGT activity in the brain and the presence of O-GlcNAcylated MIBP1 in synaptosomes further suggest that the O-GlcNAcylation of MIBP1 and subsequent pathway modulation may be involved in brain function (24, 49).

All previous MIBP1 knock-out studies were carried out using mice having the same founder. Thus, the phenotypes observed in these studies may be specific to the construct of the knock-out. Also, a compensatory biological response may have hindered the primary effects of the inactivation of the gene. Thus, a knock-out mouse may not be a suitable system to address the immediate process of action of the gene of concern, such as its transcriptional target gene(s). The genome-wide analysis performed in this study highlighted that NF-κB pathway was modulated by MIBP1, which is compatible with the biochemical nature of MIBP1, that is the binding of zinc fingers to NF-κB sites.

We showed that the primary action of MIBP1 is the repression of NF-κB and proposed that the impairment of differentiation observed using various cells derived from an MIBP1 knock-out mouse can be explained by the release of this repression. A direct proof of this hypothesis is to show that the impairment of those differentiations can be recovered by the introduction of NF-κB repression at a proper time course. This verification requires establishment of a controlled NF-κB repression system in primary culture cells from the knock-out mouse and will be the subject of future study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Masaki Matsumoto (Kyushu University) for advice on mass spectroscopic analysis; Mizuho Oda, Emiko Fujimoto, and Kumiko Fukidome (Kyushu University) for technical support; and Hiroyuki Toh and Tetsuya Sato (Kyushu University) for advice on the statistical analyses. We also thank Joan Massagué (Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center) for providing reporter plasmid p3TP-LUX and Gerald W. Hart (The Johns Hopkins University) for providing OGT expression plasmid, pLK61, and its empty vector, pLK26.

This work was supported by KAKENHI 17019051 (a grant-in-aid for scientific research in priority areas, “Applied Genomics”) and KAKENHI 18310131 (a grant-in-aid for scientific research (B)).

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S7 and Tables S1–S14.

A. I. Lamond, personal communication.

- MIBP1

- c-MYC intron binding protein 1

- OGT

- O-GlcNAc transferase

- HIVEP

- human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enhancer-binding protein

- GSEA

- gene set enrichment analysis

- EBNA

- Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen

- TFBS

- transcription factor binding site.

REFERENCES

- 1. Vaquerizas J. M., Kummerfeld S. K., Teichmann S. A., Luscombe N. M. (2009) A census of human transcription factors: function, expression and evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet. 10, 252–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Makino R., Akiyama K., Yasuda J., Mashiyama S., Honda S., Sekiya T., Hayashi K. (1994) Cloning and characterization of a c-myc intron binding protein (MIBP1). Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 5679–5685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singh H., LeBowitz J. H., Baldwin A. S., Jr., Sharp P. A. (1988) Molecular cloning of an enhancer binding protein: isolation by screening of an expression library with a recognition site DNA. Cell 52, 415–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fan C. M., Maniatis T. (1990) A DNA-binding protein containing two widely separated zinc finger motifs that recognize the same DNA sequence. Genes Dev. 4, 29–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Allen C. E., Wu L. C. (2005) in Zinc Finger Proteins (Iuchi S., Kuldell N., eds) pp. 213–220, Springer, New York [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nomura N., Zhao M. J., Nagase T., Maekawa T., Ishizaki R., Tabata S., Ishii S. (1991) HIV-EP2, a new member of the gene family encoding the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 enhancer-binding protein. Comparison with HIV-EP1/PRDII-BF1/MBP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 8590–8594 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. van 't Veer L. J., Lutz P. M., Isselbacher K. J., Bernards R. (1992) Structure and expression of major histocompatibility complex-binding protein 2, a 275-kDa zinc finger protein that binds to an enhancer of major histocompatibility complex class I genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 8971–8975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mitchelmore C., Traboni C., Cortese R. (1991) Isolation of two cDNAs encoding zinc finger proteins which bind to the α1-antitrypsin promoter and to the major histocompatibility complex class I enhancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 141–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ron D., Brasier A. R., Habener J. F. (1991) Angiotensinogen gene-inducible enhancer-binding protein 1, a member of a new family of large nuclear proteins that recognize nuclear factor κB-binding sites through a zinc finger motif. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 2887–2895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Takagi T., Harada J., Ishii S. (2001) Murine Schnurri-2 is required for positive selection of thymocytes. Nat. Immunol. 2, 1048–1053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fukuda S., Yamasaki Y., Iwaki T., Kawasaki H., Akieda S., Fukuchi N., Tahira T., Hayashi K. (2002) Characterization of the biological functions of a transcription factor, c-myc intron binding protein 1 (MIBP1). J. Biochem. 131, 349–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dörflinger U., Pscherer A., Moser M., Rümmele P., Schüle R., Buettner R. (1999) Activation of somatostatin receptor II expression by transcription factors MIBP1 and SEF-2 in the murine brain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 3736–3747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Su A. I., Wiltshire T., Batalov S., Lapp H., Ching K. A., Block D., Zhang J., Soden R., Hayakawa M., Kreiman G., Cooke M. P., Walker J. R., Hogenesch J. B. (2004) A gene atlas of the mouse and human protein-encoding transcriptomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 6062–6067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lein E. S., Hawrylycz M. J., Ao N., Ayres M., Bensinger A., Bernard A., Boe A. F., Boguski M. S., Brockway K. S., Byrnes E. J., Chen L., Chen L., Chen T. M., Chin M. C., Chong J., Crook B. E., Czaplinska A., Dang C. N., Datta S., Dee N. R., Desaki A. L., Desta T., Diep E., Dolbeare T. A., Donelan M. J., Dong H. W., Dougherty J. G., Duncan B. J., Ebbert A. J., Eichele G., Estin L. K., Faber C., Facer B. A., Fields R., Fischer S. R., Fliss T. P., Frensley C., Gates S. N., Glattfelder K. J., Halverson K. R., Hart M. R., Hohmann J. G., Howell M. P., Jeung D. P., Johnson R. A., Karr P. T., Kawal R., Kidney J. M., Knapik R. H., Kuan C. L., Lake J. H., Laramee A. R., Larsen K. D., Lau C., Lemon T. A., Liang A. J., Liu Y., Luong L. T., Michaels J., Morgan J. J., Morgan R. J., Mortrud M. T., Mosqueda N. F., Ng L. L., Ng R., Orta G. J., Overly C. C., Pak T. H., Parry S. E., Pathak S. D., Pearson O. C., Puchalski R. B., Riley Z. L., Rockett H. R., Rowland S. A., Royall J. J., Ruiz M. J., Sarno N. R., Schaffnit K., Shapovalova N. V., Sivisay T., Slaughterbeck C. R., Smith S. C., Smith K. A., Smith B. I., Sodt A. J., Stewart N. N., Stumpf K. R., Sunkin S. M., Sutram M., Tam A., Teemer C. D., Thaller C., Thompson C. L., Varnam L. R., Visel A., Whitlock R. M., Wohnoutka P. E., Wolkey C. K., Wong V. Y., Wood M., Yaylaoglu M. B., Young R. C., Youngstrom B. L., Yuan X. F., Zhang B., Zwingman T. A., Jones A. R. (2007) Genome-wide atlas of gene expression in the adult mouse brain. Nature 445, 168–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jin W., Takagi T., Kanesashi S. N., Kurahashi T., Nomura T., Harada J., Ishii S. (2006) Schnurri-2 controls BMP-dependent adipogenesis via interaction with Smad proteins. Dev. Cell 10, 461–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kimura M. Y., Hosokawa H., Yamashita M., Hasegawa A., Iwamura C., Watarai H., Taniguchi M., Takagi T., Ishii S., Nakayama T. (2005) Regulation of T helper type 2 cell differentiation by murine Schnurri-2. J. Exp. Med. 201, 397–408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Saita Y., Takagi T., Kitahara K., Usui M., Miyazono K., Ezura Y., Nakashima K., Kurosawa H., Ishii S., Noda M. (2007) Lack of Schnurri-2 expression associates with reduced bone remodeling and osteopenia. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 12907–12915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Takagi T., Jin W., Taya K., Watanabe G., Mori K., Ishii S. (2006) Schnurri-2 mutant mice are hypersensitive to stress and hyperactive. Brain Res. 1108, 88–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hart G. W., Housley M. P., Slawson C. (2007) Cycling of O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine on nucleocytoplasmic proteins. Nature 446, 1017–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hart G. W., Slawson C., Ramirez-Correa G., Lagerlof O. (2011) Cross talk between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation: roles in signaling, transcription, and chronic disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 825–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Niwa H., Yamamura K., Miyazaki J. (1991) Efficient selection for high-expression transfectants with a novel eukaryotic vector. Gene 108, 193–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lambracht D., Wonigeit K. (1995) Sequence analysis of the promoter regions of the classical class I gene RT1.Al and two other class I genes of the rat MHC. Immunogenetics 41, 375–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wrana J. L., Attisano L., Cárcamo J., Zentella A., Doody J., Laiho M., Wang X. F., Massagué J. (1992) TGFβ signals through a heteromeric protein kinase receptor complex. Cell 71, 1003–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kreppel L. K., Blomberg M. A., Hart G. W. (1997) Dynamic glycosylation of nuclear and cytosolic proteins. Cloning and characterization of a unique O-GlcNAc transferase with multiple tetratricopeptide repeats. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 9308–9315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Irizarry R. A., Hobbs B., Collin F., Beazer-Barclay Y. D., Antonellis K. J., Scherf U., Speed T. P. (2003) Exploration, normalization, and summaries of high density oligonucleotide array probe level data. Biostatistics 4, 249–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 57, 289–300 [Google Scholar]

- 27. Edgar R., Domrachev M., Lash A. E. (2002) Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 207–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Subramanian A., Kuehn H., Gould J., Tamayo P., Mesirov J. P. (2007) GSEA-P: a desktop application for Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. Bioinformatics 23, 3251–3253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rozen S., Skaletsky H. (2000) Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. 132, 365–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Untergasser A., Nijveen H., Rao X., Bisseling T., Geurts R., Leunissen J. A. (2007) Primer3Plus, an enhanced web interface to Primer3. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W71–W74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ho Sui S. J., Mortimer J. R., Arenillas D. J., Brumm J., Walsh C. J., Kennedy B. P., Wasserman W. W. (2005) oPOSSUM: identification of over-represented transcription factor binding sites in co-expressed genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 3154–3164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zambelli F., Pesole G., Pavesi G. (2009) Pscan: finding over-represented transcription factor binding site motifs in sequences from co-regulated or co-expressed genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W247–W252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sandelin A., Alkema W., Engström P., Wasserman W. W., Lenhard B. (2004) JASPAR: an open-access database for eukaryotic transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D91–D94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Portales-Casamar E., Thongjuea S., Kwon A. T., Arenillas D., Zhao X., Valen E., Yusuf D., Lenhard B., Wasserman W. W., Sandelin A. (2010) JASPAR 2010: the greatly expanded open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, D105–D110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Matys V., Kel-Margoulis O. V., Fricke E., Liebich I., Land S., Barre-Dirrie A., Reuter I., Chekmenev D., Krull M., Hornischer K., Voss N., Stegmaier P., Lewicki-Potapov B., Saxel H., Kel A. E., Wingender E. (2006) TRANSFAC and its module TRANSCompel: transcriptional gene regulation in eukaryotes. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D108–D110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Haider S., Ballester B., Smedley D., Zhang J., Rice P., Kasprzyk A. (2009) BioMart Central Portal—unified access to biological data. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W23–W27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dignam J. D., Lebovitz R. M., Roeder R. G. (1983) Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 11, 1475–1489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V. K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B. L., Gillette M. A., Paulovich A., Pomeroy S. L., Golub T. R., Lander E. S., Mesirov J. P. (2005) Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15545–15550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hayden M. S., Ghosh S. (2008) Shared principles in NF-κB signaling. Cell 132, 344–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kang Y., Chen C. R., Massagué J. (2003) A self-enabling TGFβ response coupled to stress signaling: Smad engages stress response factor ATF3 for Id1 repression in epithelial cells. Mol. Cell 11, 915–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Yang Y. C., Piek E., Zavadil J., Liang D., Xie D., Heyer J., Pavlidis P., Kucherlapati R., Roberts A. B., Böttinger E. P. (2003) Hierarchical model of gene regulation by transforming growth factor β. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 10269–10274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Defrance M., Touzet H. (2006) Predicting transcription factor binding sites using local over-representation and comparative genomics. BMC Bioinformatics 7, 396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Trinkle-Mulcahy L., Boulon S., Lam Y. W., Urcia R., Boisvert F. M., Vandermoere F., Morrice N. A., Swift S., Rothbauer U., Leonhardt H. (2008) Identifying specific protein interaction partners using quantitative mass spectrometry and bead proteomes. J. Cell Biol. 183, 223–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen G. I., Gingras A. C. (2007) Affinity-purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS) of serine/threonine phosphatases. Methods 42, 298–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hutchins J. R., Toyoda Y., Hegemann B., Poser I., Hériché J. K., Sykora M. M., Augsburg M., Hudecz O., Buschhorn B. A., Bulkescher J., Conrad C., Comartin D., Schleiffer A., Sarov M., Pozniakovsky A., Slabicki M. M., Schloissnig S., Steinmacher I., Leuschner M., Ssykor A., Lawo S., Pelletier L., Stark H., Nasmyth K., Ellenberg J., Durbin R., Buchholz F., Mechtler K., Hyman A. A., Peters J. M. (2010) Systematic analysis of human protein complexes identifies chromosome segregation proteins. Science 328, 593–599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Johnson R. S., Davis M. T., Taylor J. A., Patterson S. D. (2005) Informatics for protein identification by mass spectrometry. Methods 35, 223–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hulo N., Bairoch A., Bulliard V., Cerutti L., Cuche B. A., de Castro E., Lachaize C., Langendijk-Genevaux P. S., Sigrist C. J. (2008) The 20 years of PROSITE. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D245–D249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Shukla A., Malik M., Cataisson C., Ho Y., Friesen T., Suh K. S., Yuspa S. H. (2009) TGF-β signalling is regulated by Schnurri-2-dependent nuclear translocation of CLIC4 and consequent stabilization of phospho-Smad2 and 3. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 777–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chalkley R. J., Thalhammer A., Schoepfer R., Burlingame A. L. (2009) Identification of protein O-GlcNAcylation sites using electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry on native peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 8894–8899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]