Background: Staphylococcus aureus secretes murein hydrolases with LysM domains.

Results: We show here that the LysM domains bind to the cross-wall, the mid-cell compartment for peptidoglycan synthesis, through association with its repeating disaccharide.

Conclusion: Teichoic acid modification of peptidoglycan prevents LysM domain association with the remainder of the envelope.

Significance: These findings explain how murein hydrolases complete the bacterial cell cycle.

Keywords: Bacteria, Cell Division, Peptidoglycan, Secretion, Teichoic Acid, LysM Domain, Staphylococcus aureus, Murein Hydrolase

Abstract

Cells of eukaryotic or prokaryotic origin express proteins with LysM domains that associate with the cell wall envelope of bacteria. The molecular properties that enable LysM domains to interact with microbial cell walls are not yet established. Staphylococcus aureus, a spherical microbe, secretes two murein hydrolases with LysM domains, Sle1 and LytN. We show here that the LysM domains of Sle1 and LytN direct murein hydrolases to the staphylococcal envelope in the vicinity of the cross-wall, the mid-cell compartment for peptidoglycan synthesis. LysM domains associate with the repeating disaccharide β-N-acetylmuramic acid, (1→4)-β-N-acetylglucosamine of staphylococcal peptidoglycan. Modification of N-acetylmuramic acid with wall teichoic acid, a ribitol-phosphate polymer tethered to murein linkage units, prevents the LysM domain from binding to peptidoglycan. The localization of LytN and Sle1 to the cross-wall is abolished in staphylococcal tagO mutants, which are defective for wall teichoic acid synthesis. We propose a model whereby the LysM domain ensures septal localization of LytN and Sle1 followed by processive cleavage of peptidoglycan, thereby exposing new LysM binding sites in the cross-wall and separating bacterial cells.

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus is a human commensal and a pathogen that causes significant morbidity and mortality (1). Due to the extensive use of antibiotics, S. aureus strains have evolved that are resistant to currently available therapeutics (2). Elucidation of the mechanisms of S. aureus cell wall synthesis will aid in the development of new therapies (3). Staphylococci are small, spherical microbes, surrounded by a thick cell wall envelope that is composed of highly cross-linked peptidoglycan (murein) with attached proteins and teichoic acids (4–7). Peptidoglycan is assembled from precursors into a single large macromolecule, the murein sacculus, which protects staphylococci from osmotic lysis and serves as the attachment site for sortase-anchored surface proteins (5, 8).

Peptidoglycan synthesis in the bacterial cytoplasm generates Park's nucleotide (UDP-MurNAc3-l-Ala-d-iGlu-l-Lys-d-Ala-d-Ala) (9, 10) that is linked to bactoprenol, thereby generating lipid I (C55-PP-MurNAc-l-Ala-d-iGlu-l-Lys-d-Ala-d-Ala) (11). Further incorporation of UDP-GlcNAc results in the synthesis of lipid II (C55-PP-MurNAc(l-Ala-d-iGlu-(NH2-Gly5)l-Lys-d-Ala-d-Ala)-(β1–4)-GlcNAc) (12), which is further modified by FemXAB to incorporate a pentaglycine cross-bridge from donor glycyl-tRNAs (13–16), to create the substrate for peptidoglycan assembly on the bacterial surface (17, 18). Penicillin-binding proteins catalyze the transglycosylation reaction, polymerizing lipid II into peptidoglycan strands with repeating disaccharide structure (-MurNac-GlcNac-) (19–21). This family of enzymes also cross-links neighboring peptidoglycan strands by cleaving the terminal d-Ala moiety off of wall peptides and forming amide bonds between the carboxyl group of d-Ala at position 4 and the cross-bridge amino group (NH2-Gly5-) of adjacent wall peptides (transpeptidation) (4, 17).

The bulk of staphylococcal peptidoglycan synthesis occurs at the cross-wall (22), a membrane-enclosed compartment at mid-cell that is formed following FtsZ-mediated membrane separation between daughter cells (23). Newly formed cross-wall peptidoglycan is split, separating daughter cells for subsequent division events (24). Staphylococcal cytokinesis occurs at sites that are perpendicular to previous planes of cell division (25). This mechanism and the phenomenon of incomplete separation of cell wall envelopes are responsible for the characteristic growth patterns of staphylococci (26).

Three genes have been identified to be required for staphylococcal splitting of the cross-wall and separation of the bacteria: atl (27, 28), sle1 (29), and lytN (30). Atl is synthesized as a preproprotein (31). Following initiation into the secretory pathway and signal peptide removal, Atl is cleaved into two products with enzymatic activity, Atl-amidase and Atl-glucosaminidase (31). Three repeat domains, distributed between amidase (R1-R2) and glucosaminidase (R3), are responsible for the targeting of Atl enzymatic activity to the envelope in the immediate vicinity of the cross-wall (31, 32). Wall teichoic acid (WTA) is a key determinant of Atl localization; in a tagO mutant, defective in the synthesis of the murein linkage units for polyribitol-phosphate WTA (33), Atl localization is not restricted to the cross-wall sections of the staphylococcal envelope and instead binds uniformly to the cell surface (34). S. aureus mutants lacking the atl gene are defective in cell separation and form characteristic aggregates of bacterial cells (27). A similar phenotype is observed for sle1 mutants (29). The Sle1 precursor is secreted via an N-terminal signal peptide; its mature product encompasses three LysM domains and a C-terminal CHAP (cysteine, histidine-dependent amidohydrolase/peptidase) domain (35), which cleaves staphylococcal peptidoglycan via its N-acetylmuramoyl-l-Ala amidase activity (29). The genome of S. aureus encodes only one additional murein hydrolase, LytN, with LysM and CHAP domains (30). The LytN precursor is secreted via a YSIRK(G/S) motif signal peptide (36), which directs the protein into the cross-wall compartment (30). LytN cleaves staphylococcal peptidoglycan through its N-acetylmuramyl-l-Ala amidase and d-Ala-Gly endopeptidase activities (30). Staphylococcal lytN mutants display defects in growth and murein structure, caused by the inadequate splitting of cross-wall peptidoglycan (30).

LysM domains, first identified as 44-residue repeats in Bacillus subtilis bacteriophage ø29 lysozyme (37), have also been identified in murein hydrolases responsible for cell separation of Lactococcus lactis (38, 39), Listeria monocytogenes (40), and Enterococcus faecalis (41). LysM domains have been found within chitinases from nematodes, plants, and green algae and contribute to the cleavage of chitin by directly binding poly-(1→4)-β-N-acetylglucosamine (42, 43). LysM domains have also been identified in plant legume receptors involved in recognition of Nod factors (i.e. lipochitin-oligosaccharides released by nitrogen-fixing Rhizobia) (44, 45) and in the establishment of plant-bacterial symbiosis (46). The role of the LysM domains of the major autolysin AcmA from L. lactis in binding to peptidoglycan has been investigated (39). Although the LysM domains of AcmA were not required for murein hydrolase activity, the domains were sufficient to mediate binding of reporter proteins to peptidoglycan. LysM domain binding was increased by treatment of peptidoglycan with trichloroacetic acid, which led to the proposal that lipoteichoic acids (i.e. polyglycerolphosphate polymers) (47) may play a role in modulating the association of AcmA with the bacterial envelope (39, 43). Here we investigated the role of the LysM domains in Sle1 and LytN during cross-wall splitting and cell separation of S. aureus.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Bacterial Strains and Reagents

S. aureus Newman (48) and its variant carrying a bursa aurealis insertion in lytN and sle1 are part of the Phoenix library (49). lytN and sle1 mutational lesions were transduced with bacteriophage φ85 into the wild-type S. aureus Newman isolate. Plasmid DNA was first electroporated into S. aureus RN4220 (50) and then into S. aureus Newman or lytN/sle1 mutant strains (30). S. aureus was grown in tryptic soy broth or on tryptic soy agar plates supplemented with appropriate antibiotics. Erythromycin and chloramphenicol were used at a 10 μg/ml concentration. Escherichia coli was grown in LB broth or on LB agar plates supplemented with either ampicillin (100 μg/ml) or kanamycin (50 μg/ml). All chemicals used were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Fisher, unless otherwise stated.

Plasmid Construction

Recombinant production of LytN-mCherry (prLytN-mCherry) was described previously (26). To introduce an in-frame deletion of the LysM domain on this plasmid, QuikChange mutagenesis (Stratagene) was used with primers 5′-CAGTTTTAGAGAAGCTCCAAAAACACCAATGACACCATTAGTAGAACCAA-3′ and 5′-TTGGTTCTACTAATGGTGTCATTGGTGTTTTTGGAGCTTCTCTAAAACTG-3′ to delete amino acids 175–220. This was also used to generate a deletion of the LysM domain for expression of LytN within staphylococci (ptet::lytN) (26). The CHAP domain deletion of prLytN-mCherry was created by SOE PCR using primers 5′-CCGGATCCGGATGAAATTGATAAATCTAAAGATTTTACAAGAG-3′ and 5′-CTCGCCCTTGCTACTATTACTTTTATTATTTGAAGACACTGTTTTTG-3′ to amplify lytN and 5′-AAAAGTAATAGTAGCAAGGGCGAGGAGGATAACATGG-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCC-3′ to amplify mCherry. The underlined sequence denotes complementary sequence for SOE PCR. To generate recombinant LysM-mCherry (rLysM-mCherry), the LysM domain of LytN was amplified using primers 5′-CCGGATCCGCAAATCTATACTGTAAAAAAAGGAGACACAC-3′ and 5′-CTCGCCCTTGCTTGGCACTTTTAATTTTTGACCAAT-3′ with Newman genomic DNA as a template, whereas primers 5′-TTAAAAGTGCCAAGCAAGGGCGAGGAGGATAACATGG-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCC-3′ were used to amplify mCherry. The underlined sequence denotes complementary sequence for SOE PCR. For amplification of the Sle1 LysM domains, primers 5′-CCGGATCCGCACACAGTAAAACCGGGTGAATCA-3′ and 5′-CTCGCCCTTGCTAGTTACTTTCAATTTTTGACCCGG-3′ were used, and 5′-TTGAAAGTAACTAGCAAGGGCGAGGAGGATAACATGG-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCC-3′ were used to amplify mCherry.

sle1 expression in S. aureus (ptet::sle1) was created using primers 5′-GGCCTAGGAGGAGGACAGCTATGCAAAAAAAAGTAATTGCAGCTATTA-3′ and 5′-GATCCCGCGGTTAGTGAATATATCTATAATTATTTACTTGGTAAGCTG-3′, which introduced AvrII and SacII sites, and cloned into pMF312 at these sites (26). Deletion of the LysM domains of sle1 was conducted by QuikChange mutagenesis (Stratagene) using primers 5′-ACTCAAGCAAATGCGGCTACAACTGGCTCAAGTAATTCTACGAGTAAT-3′ and 5′-ATTACTCGTAGAATTACTTGAGCCAGTTGTAGCCGCATTTGCTTGAGT-3′ (LysM1), 5′-ACTCAAGCAAATGCGGCTACAACTGGTACTGCTAGCTCAAGTAACGCT-3′ and 5′-AGCGTTACTTGAGCTAGCAGTACCAGTTGTAGCCGCATTTGCTTGAGT-3′ (LysM1-2), and 5′-ACTCAAGCAAATGCGGCTACAACTGGTAATGCATCTACGAACTCAGGA-3′ and 5′-TCCTGAGTTCGTAGATGCATTACCAGTTGTAGCCGCATTTGCTTGAGT-3′ (LysM1-3).

Recombinant Sle1-mCherry (prSle1-mCherry) was generated by SOE PCR using primers 5′-CCGGATCCGACTCACACAGTAAAACCGGGTGAAT-3′ and 5′-CTCGCCCTTGCTGTGAATATATCTATAATTATTTACTTGGTAAGCTG-3′ to amplify sle1 and using 5′-AGATATATTCACAGCAAGGGCGAGGAGGATAACATGG-3′ and 5′-GGCTCGAGCTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATGCC-3′ to amplify mCherry. Underlined sequence denotes complementary sequence for SOE reaction. All recombinant protein expression vectors were cloned using BamHI and XhoI sites and introduced into pET24b at identical sites using T4 DNA ligase. Transformants were isolated, plasmid DNA was purified, and plasmids were sequenced.

Fluorescence Cytometry, Light Microscopy, Immunofluorescence, and Electron Microscopy

For fluorescence cytometry, logarithmically growing cultures were centrifuged, staphylococcal sediment was washed in PBS, and bacteria were incubated with purified protein (e.g. LytN-mCherry) for 10 min. Cells were washed twice in PBS, fixed in paraformaldehyde, and processed on an LSRII Blue cell sorter (BD Biosciences). Light micrographs were captured from stationary phase grown cultures. Cells were sedimented by centrifugation and suspended in PBS. A 1-μl suspension was placed on a glass slide and covered with a coverslip. Cells were viewed on an Olympus AX-70 fluorescence microscope, and images were captured with a charge-coupled device camera. For immunofluorescence microscopy, cells were grown to logarithmic phase and co-stained with either concanavalin A-FITC (ConA) or BODIPY-vancomycin. For ConA staining, cells were washed in PBS and boiled for 30 min in 10% SDS. Cells were then washed three times with water and suspended in 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 6.8. 100 μg of ConA was added, together with 1 mm CaCl2 and 0.1 mm MnCl2. Cells were incubated in the dark for 30 min and washed twice in PBS. Recombinant fluorescent protein was added and allowed to adhere to cells for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were washed once with PBS, fixed in paraformaldehyde, and applied to poly-l-lysine-treated glass coverslips. BODIPY-vancomycin staining was performed as described previously (30). Images were captured on a Leica TCS SP2 AOBS laser-scanning confocal microscope with a 100× objective using identical settings and exposure times among samples. Thin section transmission electron microscopy was performed as described previously (30). Cells were harvested from logarithmic phase cells.

Peptidoglycan Isolation and Binding Studies

Peptidoglycan was isolated from S. aureus strains Newman, RN4220 and a ΔtagO variant of RN4220 (51) as described previously (30). Purified peptidoglycan samples were split and treated with hydrofluoric acid (HF) or left untreated (52). Total peptidoglycan concentration was normalized by measuring absorbance at 600 nm. Peptidoglycan was incubated with purified fluorescent protein for 10 min. Samples were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5 min and washed once with PBS, murein sacculi and bound protein were suspended in PBS, and fluorescence was quantified in a fluorescent plate reader by excitation at 540-nm and detection at 645-nm light. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

Treatment of peptidoglycan with muralytic enzymes, resolving of muropeptides by HPLC, and MALDI-TOF MS were performed as described previously (30). For competitive binding assays, peptidoglycan was treated overnight with lysostaphin, mutanolysin, or recombinant LytN (30). Soluble muropeptides were incubated with mCherry, LysMLytN-mCherry, or LysMSle1-mCherry for 10 min at room temperature; added to isolated murein sacculi; and incubated for 10 min. Samples were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 5 min, sacculi were washed and suspended in PBS, and fluorescence was quantified.

RESULTS

LysM Domain Is Required for LytN Binding to Staphylococcal Peptidoglycan

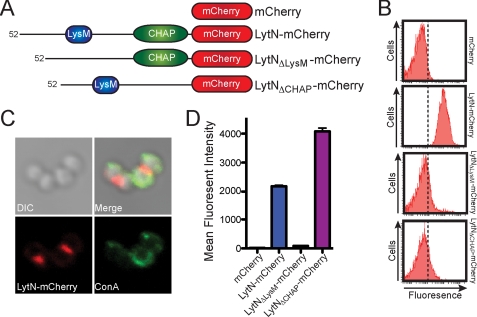

A hybrid LytN-mCherry was generated that encompasses the mature (secreted) form of LytN at the N terminus fused to fluorescent protein, mCherry, and a C-terminal His6 tag (Fig. 1A). Affinity-purified LytN-mCherry was added to staphylococci, and protein binding to the bacterial envelope was measured by fluorescence cytometry (Fig. 1B). In contrast to mCherry control, for which no fluorescence signal was detected, LytN-mCherry bound to the staphylococcal envelope and generated fluorescence signals (Fig. 1B). Removal of the N-terminal LysM domain abolished the binding of LytNΔLysM-mCherry to the cell surface (Fig. 1, A and B). Because LytN displays N-acetylmuramoyl-l-Ala amidase as well as d-Ala-Gly endopeptidase activity (30), we wondered whether LytN-mCherry binding to the staphylococcal envelope involves not only the LysM domain but also the enzymatic activity (CHAPS domain) of this enzyme. LytNΔCHAP-mCherry, a hybrid with an in-frame deletion of the catalytic domain (30) (Fig. 1A), failed to associate with the envelope of staphylococci (Fig. 1B), suggesting that murein hydrolase activity is required to promote LytN association with the cross-wall.

FIGURE 1.

LysM and CHAPS domains are both required for LytN localization to the cross-wall. A, diagram of the LytN-mCherry hybrid and its variants. Color-coded domains identify the LysM domain (blue), the CHAP domain (green), and the mCherry fusion (red). B, S. aureus Newman cells were fixed and incubated with purified mCherry, LytN-mCherry, LytNΔLysM-mCherry, or LytNΔCHAP-mCherry. Binding of proteins to the staphylococcal envelope was assessed by fluorescence cytometry. C, microscopy of S. aureus Newman stained with ConA and incubated with LytN-mCherry. The top left panel displays the DIC image of staphylococcal cells, which were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (bottom panels) for red (LytN-mCherry) and green (ConA) signals. The top right panel displays a merged image derived from all three data sets. D, purified mCherry, LytN-mCherry, LytNΔLysM-mCherry, or LytNΔCHAP-mCherry was incubated with purified peptidoglycan from S. aureus Newman, which had been isolated by glass bead disruption of murein sacculi, treated with protease, and extracted with detergent, and finally WTA was removed with HF. Protein binding to peptidoglycan was analyzed with a co-sedimentation assay and fluorescence intensity measurements. All binding assays were performed in triplicate; average data and S.E. (error bars) were recorded.

We used fluorescence microscopy to localize the binding of LytN-mCherry to the bacterial envelope (Fig. 1C). LytN-mCherry fluorescence signals were localized in merged differential interference contrast (DIC) images to the cross-walls of dividing staphylococci (Fig. 1C). In addition, we labeled staphylococci with ConA, a compound that associates with polyribitolphosphate WTA (53). LytN-mCherry binding sites were not labeled with ConA. As previously reported, ConA signals were distributed throughout the staphylococcal envelope except at the cross-walls (Fig. 1C) (54). In agreement with the data in Fig. 1B, LytNΔLysM-mCherry, LytNΔCHAP-mCherry, and mCherry did not produce a detectable fluorescent signal when analyzed for its ability to bind to staphylococci (data not shown). To determine if LytN-mCherry binds to peptidoglycan, we isolated murein sacculi of S. aureus Newman, removed proteins as well as lipids by treatment with protease and detergent, and finally hydrolyzed WTA with HF (55). Binding of fluorescent protein to the peptidoglycan layer of murein sacculi was detected with a co-sedimentation assay. LytN-mCherry and LytNΔCHAP-mCherry co-sedimented with isolated murein sacculi, which was not observed for either LytNΔLysM-mCherry or mCherry (Fig. 1D). Thus, the LysM domain of LytN is required for its binding to isolated peptidoglycan and for the localized association of this enzyme with the cross-wall section of the staphylococcal envelope. As LytNΔCHAP binds purified peptidoglycan but does not localize to the staphylococcal envelope, we surmise that both LysM domain binding to peptidoglycan and murein hydrolase activity are necessary to promote the specific localization of LytN to the cross-wall.

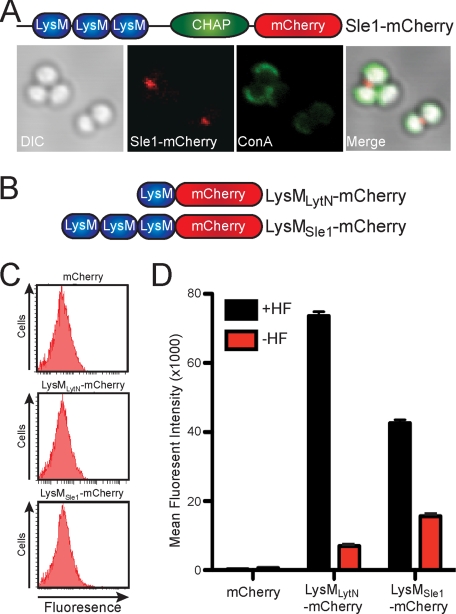

LysM Domains of LytN and Sle1 Bind to Staphylococcal Peptidoglycan Void of WTA

Sle1, the only other staphylococcal CHAP domain-containing murein hydrolase, that has been shown to be required for cell separation, also harbors LysM domains (29). We wondered whether the three LysM domains of Sle1 are sufficient to promote association of the polypeptide with the staphylococcal envelope. Sle1-mCherry, a hybrid between full-length Sle1 and mCherry (Fig. 2A), bound to the envelope of S. aureus Newman at the cross-wall between dividing cells (Fig. 2A). However, LysMSle1-mCherry (Fig. 2B), encompassing the three LysM domains of Sle1 fused to the N terminus of affinity-tagged mCherry, failed to associate with the cross-wall (see below). The hybrid LysMLytN-mCherry encompasses only the LysM domain of LytN fused to mCherry (Fig. 2B). LysMLytN-mCherry was also unable to bind to the envelope of S. aureus Newman (Fig. 2C). Thus, LytN and Sle1 association with the cross-wall of staphylococci involves both LysM and CHAP domains. Fluorescence cytometry experiments corroborated this observation, revealing that neither LysMLytN-mCherry nor LysMSle1-mCherry associated with the envelope of staphylococci (Fig. 2C). Thus, LysM domains alone are not sufficient to deliver mCherry hybrids to the cross-wall compartment of staphylococci.

FIGURE 2.

The LysM domains of LytN and Sle1 bind to staphylococcal peptidoglycan. A, purified Sle1-mCherry (see top panel diagram for the domain structure of the hybrid) was incubated with S. aureus Newman cells that had been stained with ConA. The left panel displays the DIC image of staphylococcal cells analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (middle panels) for red (Sle1-mCherry) and green (ConA) signals. The right panel displays a merged image derived from all three data sets. B, diagram for the domain structures of the LysM domains from LytN and Sle1 fused to mCherry. C, mCherry, LysMLytN-mCherry, or LysMSle1-mCherry was incubated with wild-type staphylococci and assessed for binding with fluorescence cytometry. D, mCherry, LysMLytN-mCherry, or LysMSle1-mCherry was incubated with purified peptidoglycan from S. aureus Newman, which had been isolated by glass bead disruption of murein sacculi, treated with protease, and extracted with detergent. Murein sacculi were either treated with hydrofluoric acid (+HF) or left untreated (−HF) prior to analyzing mCherry hybrids by co-sedimentation and fluorescence intensity measurements. All binding assays were performed in triplicate; average data and S.E. (error bars) were recorded.

The envelopes of intact staphylococci or their isolated murein sacculi are decorated with WTA (7), which is removed from peptidoglycan by HF treatment. Co-sedimentation experiments detected only small amounts of LysMLytN-mCherry and LysMSle1-mCherry binding to isolated murein sacculi, whereas mCherry alone did not associate with murein sacculi at all (Fig. 2D). HF-mediated removal of WTA caused a dramatic increase in the ability of LysMLytN-mCherry or LysMSle1-mCherry to associate with murein sacculi (Fig. 2D). As a control, HF treatment did not increase the association between murein sacculi and mCherry (Fig. 2D). These data suggest that the LysM domains of LytN and Sle1 bind to peptidoglycan sites that are not decorated with WTA. LysM domain association with the staphylococcal envelope was detected with isolated murein sacculi but not with intact bacterial cells (Fig. 2CD); this is presumably due to the exposure of peptidoglycan sites that are not decorated with WTA following physical rupture of the cell wall envelope with glass beads.

LysM Domain Binding to Peptidoglycan of tagO Mutant Staphylococci

WTA synthesis begins in the cytoplasm as the TagO-catalyzed transfer of GlcNAc from UDP-GlcNAc substrate to undecaprenyl pyrophosphate (C55-PP), which functions as a lipid carrier for both WTA and peptidoglycan synthesis (11, 56–58). The TagO-catalyzed reaction is reversible (57). Following a sequence of enzymatic reactions (59, 60), WTA precursor (C55-GlcNAc-ManNAc-(Gro)2–3-(ribitol-P)20–50) is translocated across the plasma membrane by a process involving the ABC transporter TagGH (61). WTA precursor is finally linked to peptidoglycan (62), a reaction that is catalyzed by the LCP family of proteins (63), which are thought to generate the phosphodiester bonds between the C6 hydroxyl group of MurNAc (peptidoglycan; PG) and the C1 hydroxyl group of GlcNAc (WTA) (64). The phosphodiester bond between PG and WTA can be hydrolyzed with HF (64, 65). Mutations in tagO or tagA, the latter of which encodes an enzyme adding ManNAc to C55-PP-GlcNAc (the first committed step of WTA synthesis) (66), abolish WTA synthesis but do not block staphylococcal growth (33). Mutations in several other WTA synthesis genes are not compatible with growth; the resulting variants accumulate undecaprenol intermediates of WTA synthesis, sequestering the lipid carrier from the essential PG synthesis pathway (67).

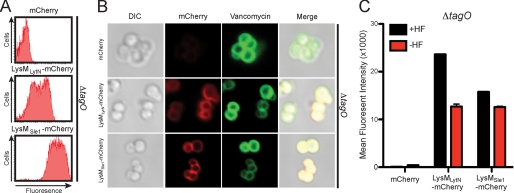

To investigate the role of WTA in LysM domain association with the staphylococcal envelope, LysMLytN-mCherry or LysMSle1-mCherry were incubated with tagO mutant staphylococci (68) and examined by fluorescence cytometry (Fig. 3A). In contrast to the mCherry control, LysMLytN-mCherry as well as LysMSle1-mCherry bound to the envelope of tagO staphylococci (Fig. 3A). Of note, LysMSle1-mCherry generated stronger fluorescence signals than LysMLytN-mCherry (Fig. 3A); this was attributed to the three tandem LysM domains at the N-terminal end of LysMSle1-mCherry. To localize the binding of fluorescent proteins, staphylococci were incubated with BODIPY-vancomycin, which binds to the two terminal d-Ala residues within cell wall pentapeptides, as well as lipid II (69) (Fig. 3B). LysMLytN-mCherry as well as LysMSle1-mCherry bound the tagO mutant staphylococci throughout their entire cell wall envelope, as evidenced by superimposable fluorescence signals for the LysM domain proteins and BODIPY-vancomycin (Fig. 3B). mCherry alone did not bind to staphylococcal tagO mutants (Fig. 3B). Thus, in the absence of WTA, LysM domain proteins bind indiscriminately to peptidoglycan and are not localized to the cross-wall compartment.

FIGURE 3.

Wall teichoic acid modification interferes with the binding of LysM domains to peptidoglycan. A, purified mCherry, LysMLytN-mCherry, or LysMSle1-mCherry was incubated with ΔtagO mutant staphylococci, and binding to the bacterial envelope was measured by fluorescence cytometry. B, purified mCherry, LysMLytN-mCherry, or LysMSle1-mCherry was incubated with ΔtagO mutant staphylococci that had been stained with BODIPY-vancomycin (Vancomycin). The left panels display the DIC image of staphylococcal cells analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (middle panels) for red (Cherry, LysMLytN-mCherry, or LysMSle1-mCherry) and green (vancomycin) signals. The right panels display merged images derived from all three data sets. C, Cherry, LysMLytN-mCherry, or LysMSle1-mCherry was incubated with purified peptidoglycan from ΔtagO mutant staphylococci, which had been isolated by glass bead disruption of murein sacculi, treated with protease, and extracted with detergent. Murein sacculi were either treated with hydrofluoric acid (+HF) or left untreated (−HF) prior to analyzing mCherry hybrids by co-sedimentation and fluorescence intensity measurements. All binding assays were performed in triplicate; average data and S.E. (error bars) were recorded.

Murein sacculi of tagO mutant staphylococci were isolated and incubated with fluorescent proteins (Fig. 3C). LysMLytN-mCherry as well as LysMSle1-mCherry, but not mCherry alone, associated with murein sacculi of tagO mutant staphylococci (Fig. 3C). HF treatment of the murein sacculi from tagO mutant staphylococci caused further increases in the binding of LysMLytN-mCherry and LysMSle1-mCherry to murein sacculi (Fig. 3C). We surmise that S. aureus harbors additional peptidoglycan modifications that can be removed by treatment with HF, thereby increasing the binding of LysM domain proteins to the bacterial envelope.

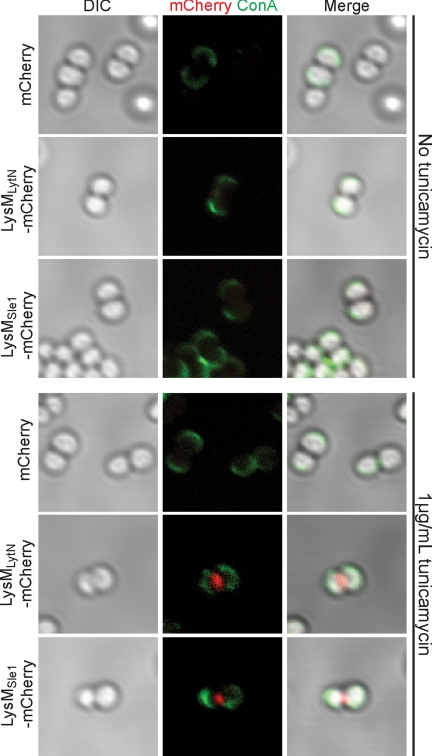

Tunicamycin Treatment Enables LysM Domain Binding to Staphylococcal Cross-wall

Tunicamycin, an antibiotic of Streptomyces spp. (70), inhibits TagO and thereby WTA synthesis (71). At higher concentrations (i.e. the minimal inhibitory concentration of 10–40 μg), tunicamycin also blocks translocase I (MraY), a key enzyme for peptidoglycan synthesis (70). S. aureus was grown to logarithmic phase and treated for 30 min with 1 μg/ml tunicamycin, a concentration that is known to specifically block TagO (52). Staphylococci were sedimented by centrifugation, and WTA was stained with ConA (Fig. 4). Incubation of ConA-labeled staphylococci with fluorescent proteins revealed that LysMLytN-mCherry as well as LysMSle1-mCherry bound to the cross-wall of staphylococci that had been treated with tunicamycin but not to untreated staphylococci (Fig. 4). As a control, mCherry did not bind to the envelope of tunicamycin-treated staphylococci. These data suggest that a block in WTA synthesis at the cross-wall enables LysM domain binding to cross-wall peptidoglycan.

FIGURE 4.

The LysM domains of LytN and Sle1 bind to the cross-wall of tunicamycin-treated staphylococci. Staphylococci were grown to logarithmic phase and treated with 1 μg/ml tunicamycin (bottom panels) or left untreated (top panels) for 30 min. Staphylococci were fixed, stained with ConA, and incubated with mCherry, LysMLytN-mCherry, or LysMSle1-mCherry recombinant proteins. Cells were then adhered to a coverslip and viewed by microscopy. Left panels display the DIC image of staphylococcal cells analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (middle panels) for red (Cherry, LysMLytN-mCherry, or LysMSle1-mCherry) and green (ConA) signals. The right panels display merged images derived from all data sets.

LysM Domains Bind to Glycan Chains of Staphylococcal Peptidoglycan

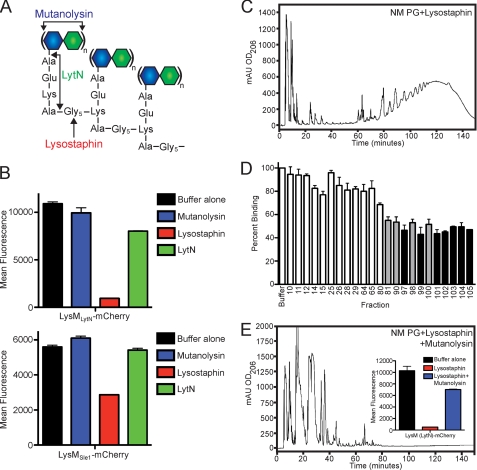

Isolated murein sacculi of S. aureus Newman were treated with protease, extracted with detergent, and then digested with any one of three muralytic enzymes: mutanolysin, lysostaphin, or LytN (Fig. 5A). Mutanolysin (muramidase) cleaves the glycosidic bonds between the repeating disaccharide units (→4)-β-MurNAc-(1→4)-β-GlcNAc-(1→)n (19), thereby releasing disaccharide with cross-linked muropeptides: MurNAc(Ala-Gln-Lys(Gly5)-Ala)n-(1→4)-β-GlcNAc (72, 73) (Fig. 5A). Lysostaphin cleaves the pentaglycine cross-bridge of staphylococci, liberating glycans with variable numbers of the repeating disaccharide units tethered to non-cross-linked wall peptides (→4)-β-MurNAc(Ala-Gln-Lys(NH2-Gly3)-Ala-Gly2)-(1→4)-β-GlcNAc-(1→)n (55, 74) (Fig. 5A). LytN cleaves the MurNAc-l-Ala amide bond as well as the d-Ala-Gly amide bond, releasing non-cross-linked wall peptides without the disaccharide units (Ala-Gln-Lys(NH2-Gly5)-Ala) (Fig. 5A). Soluble muropeptides generated from each of these three enzymes were incubated with LysMLytN-mCherry or LysMSle1-mCherry and assayed for binding to HF-treated peptidoglycan (Fig. 5B). As compared with mock (buffer control)-treated peptidoglycan, mutanolysin-derived muropeptides did not inhibit binding of LysMLytN-mCherry or of LysMSle1-mCherry to peptidoglycan. Similarly, LytN-derived muropeptides also failed to interfere with either LysMLytN-mCherry or LysMSle1-mCherry binding to peptidoglycan (Fig. 5B). In contrast, lysostaphin-solubilized muropeptides, (→4)-β-MurNAc(Ala-Gln-Lys(NH2-Gly3)-Ala-Gly2)-(1→4)-β-GlcNAc-(1→)n, blocked the binding of LysMLytN-mCherry and LysMSle1-mCherry to peptidoglycan (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

LysM domains of LytN and Sle1 bind to the repeating disaccharide strands of staphylococcal peptidoglycan. A, diagram of the structure of S. aureus peptidoglycan, identifying the cleavage sites for mutanolysin, lysostaphin, and LytN. B, HF-treated, purified peptidoglycan was digested with mutanolysin, lysostaphin, or LytN. Soluble muropeptides were incubated with LysMLytN-mCherry or LysMSle1-mCherry. Inhibition of the binding of mCherry hybrids to staphylococcal murein sacculi was measured with co-sedimentation and fluorescence intensity measurements. All binding assays were performed in triplicate; average data and S.E. were recorded. C, RP-HPLC chromatography of lysostaphin-treated S. aureus Newman (NM) PG. D, PG compounds in the fractions of the RP-HPLC experiment from C were dissolved in water and incubated with LysMLytN-mCherry. Inhibition of the binding of LysMLytN-mCherry to staphylococcal murein sacculi was measured with co-sedimentation and fluorescence intensity measurements. Gray bars, reduction of >40%; black bars, reduction of >50%. E, lysostaphin-treated peptidoglycan was incubated with mutanolysin and subjected to RP-HPLC. Inset, binding of LysMLytN-mCherry preincubated with buffer control or lysostaphin-solubilized or lysostaphin and mutanolysin-solubilized peptidoglycan to staphylococcal murein sacculi. All binding assays were performed in triplicate; average data and S.E. (error bars) were recorded.

To identify the inhibitory molecules within lysostaphin-cleaved peptidoglycan fragments, samples were subjected to RP-HPLC, and isolated fractions were dried and screened for the inhibition of LysMLytN-mCherry binding to peptidoglycan (Fig. 5C). Peptidoglycan fragments eluting after 80 min (>50% methanol) inhibited the association of LysMLytN-mCherry with peptidoglycan (Fig. 5, C and D). MALDI-TOF MS was used to identify the structure of lysostaphin-solubilized peptidoglycan fragments in individual fractions. Table 1 summarizes the findings for some of the isolated fractions. Fraction 10 harbored the wall peptide Ala-Gln-Lys(NH2-Gly1–2)-Ala-Gly1–2, whereas fraction 11 contained the muropeptide MurNAc(Ala-Gln-Lys(NH2-Gly1–2)-Ala-Gly1–2)-(1→4)-β-GlcNAc. Neither the wall peptide nor the disaccharide muropeptide inhibited LysMLytN-mCherry binding to peptidoglycan (Fig. 5D). Similar data were collected with the tetrasaccharide (→4)-β-MurNAc(Ala-Gln-Lys(NH2-Gly1–2)-Ala-Gly1-2)-(1→4)-β-GlcNAc-(1→)2. Fractions 81 and higher harbored hexa- and octasaccharides (→4)-β-MurNAc(Ala-Gln-Lys(NH2-Gly1–2)-Ala-Gly1-2)-(1→4)-β-GlcNAc-(1→)3–4. These fractions inhibited LysMLytN-mCherry binding to murein sacculi (Fig. 5D and Table 1). From this we conclude that the LysM domains of LytN or Sle1 bind to the reiterative disaccharide of the glycan strands, which must be at least six amino sugar residues in length. If so, treatment of lysostaphin-solubilized muropeptides with a muramidase would cut the glycan strands and diminish their ability to interfere with LysMLytN-mCherry binding to murein sacculi. This was tested, and muramidase treatment of lysostaphin-solubilized muropeptides indeed reduced their ability to interfere with LysM domain function (Fig. 5E).

TABLE 1.

Predicted structure of LysM binding muropeptides purified as described in the legend to Fig. 5

| Fractiona | Predicted structure | Mass/charge (m/z) |

Δ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted | Observed | |||

| 10 | AQKG3A | 588.64 | 587.96 | −0.68 |

| 10 | AQKG4A | 645.69 | 645.01 | −0.68 |

| 25 | AQKG3A2 | 659.72 | 660.00 | 0.28 |

| 25 | AQKG4A2 | 716.77 | 717.05 | 0.28 |

| 11 | (MurNAc)-AQKA2 | 762.38 | 762.20 | −0.18 |

| 11 | (MurNAc)-AQKGA2 | 819.40 | 819.27 | −0.13 |

| 65 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)2-(AQKG2A2)2 | 2141.99 | 2141.94 | −0.05 |

| 65 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)2-(AQKG2A2)-(AQKG3A2) | 2199.01 | 2199.24 | 0.23 |

| 65 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)2-(AQKG3A2)2 | 2256.03 | 2256.02 | −0.01 |

| 65 | (MurNAc3-GlcNAc2)-(AQKA)3 | 2445.16 | 2444.96 | −0.2 |

| 65 | (MurNAc3-GlcNAc2)-(AQKA)2(AQKGA) | 2502.18 | 2502.02 | −0.16 |

| 81 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)3-(AQKG3A)3 | 3163.21 | 3163.07 | −0.14 |

| 81 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)2-(AQKG3A)2-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQKG4A | 3220.23 | 3220.35 | 0.12 |

| 81 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)2-(AQKG3A)2-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQKG5A | 3277.25 | 3277.07 | −0.18 |

| 81 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)2-(AQKA)2-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQK-(MurNAc)-AQKG2A | 3366.49 | 3366.66 | 0.17 |

| 81 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)2-(AQKA)2-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQGK-(MurNAc)-AQKG2A | 3423.51 | 3423.74 | 0.23 |

| 81 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)2-(AQKA)2-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQG2K-(MurNAc)-AQKG2A | 3480.53 | 3481.74 | 1.21 |

| 81 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)2-(AQKA)2-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQG3K-(MurNAc)-AQKG2A | 3537.55 | 3538.20 | 0.65 |

| 81 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)2-(AQKA)2-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQG4K-(MurNAc)-AQKG2A | 3594.57 | 3595.26 | 0.69 |

| 81 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)2-(AQKA)2-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQKA-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQK | 3510.63 | 3509.68 | −0.95 |

| 81 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)2-(AQKA)2-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQGKA-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQK | 3567.65 | 3566.44 | −1.21 |

| 90 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)4-(AQKA)4-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQG3K | 4299.00 | 4297.80 | −1.20 |

| 90 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)4-(AQKA)4-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQG4K | 4356.02 | 4354.61 | −1.41 |

| 90 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)4-(AQKA)4-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQG5K | 4413.04 | 4411.64 | −1.40 |

| 90 | (MurNAc-GlcNAc)4-(AQKA)4-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQG3K-(MurNAc-GlcNAc)-AQKGA | 4470.06 | 4468.85 | −1.21 |

a Muropeptides were separated by RP-HPLC. Isolated fractions were analyzed for their ability to inhibit binding of LysMLytN-mCherry or LysMSle1-mCherry to staphylococcal murein sacculi (fractions 80–90). Compounds were also subjected to MALDI-MS TOF. Observed ion signals (m/z) were compared with the mass/charge ratio of predicted structures, and the differential was recorded (Δ).

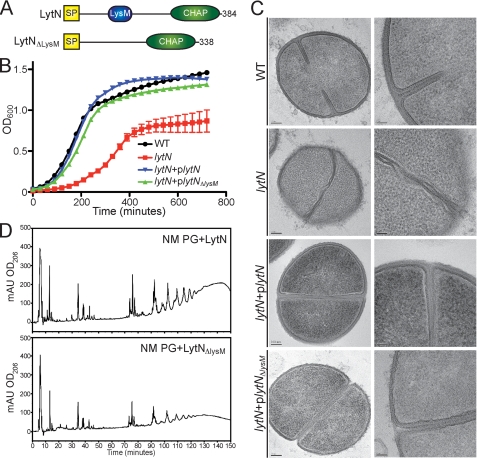

LysM Domain of LytN Is Not Absolutely Essential for Function

The lytN gene encodes a precursor with a YSIR(K/G)S signal peptide that directs the mature protein to the cross-wall compartment (Fig. 6A). An insertional mutation with the bursa aurealis minitransposon (ermC) in lytN abolishes lytN expression and impairs staphylococcal growth (Fig. 6B) (30). Transmission electron microscopy of thin sectioned staphylococci revealed that the lytN mutant displays defects in the splitting of cross-wall peptidoglycan and in the overall structure of the peptidoglycan in the bacterial envelope (30) (Fig. 6C). Both defects, in staphylococcal growth and in peptidoglycan structure, can be restored by expression of plasmid-encoded wild-type lytN in the lytN::ermC (plytN) strain (Fig. 6BC). The data in Fig. 6B suggest also that the lytN::ermC (plytN) strain grows at a similar rate to a lytN variant lacking the coding sequence for the LysM domain (lytN::ermC (plytNΔLysM)) (Fig. 6B). Because the lytN::ermC (plytNΔLysM) strain displayed the structural attributes of the cross-wall that were similar to wild type, we conclude that the LysM domain of LytN is not absolutely required for its function (Fig. 6C).

FIGURE 6.

Contribution of the LysM domain to LytN function. A, diagram of the domain structure of LytN and its LytNΔLysM variant. B, the growth of S. aureus Newman (WT) or its lytN variant with or without plytN or plytNΔLysM plasmids was measured as the increase in the absorbance at 600-nm light. C, staphylococcal strains were fixed, thin sectioned, and viewed by transmission electron microscopy to visualize the cell wall envelope and cross-wall. Images of the panels on the left display a single cell; images of the panels on the right show the cross-walls of a staphylococcal cell. D, purified LytN and LytNΔLysM were incubated with highly purified staphylococcal peptidoglycan. Soluble muropeptides were separated by RP-HPLC, and muropeptides were detected by absorbance at 206-nm light. Standard error (S.E.) of the mean recorded (error bars).

Purified recombinant LytN and a LytN variant lacking the LysM domain (LytNΔLysM) were incubated for 16 h with purified HF-treated peptidoglycan. Peptidoglycan cleavage products were subjected to RP-HPLC, and eluate fractions were analyzed for muropeptides (Fig. 6D). As reported previously, LytN generated a spectrum of muropeptides composed mostly of non-cross-linked wall peptides (Ala-Gln-Lys(NH2-Gly5)-Ala) as well as disaccharide units liberated via its d-Ala-Gly endopeptidase activity (→4)-β-MurNAc(Ala-Gln-Lys(NH2-Gly5)-Ala)-(1→4)-β-GlcNAc-(1→)n. The LytNΔLysM variant generated a spectrum of peptidoglycan cleavage fragments whose elution patterns were identical to those of LytN-treated samples, albeit the overall amount of cleaved peptidoglycan was reduced (Fig. 6D). From this we conclude that LysM domain binding to glycan strands contributes to the overall efficacy of LytN-mediated cleavage of peptidoglycan but is not essential for enzymatic activity.

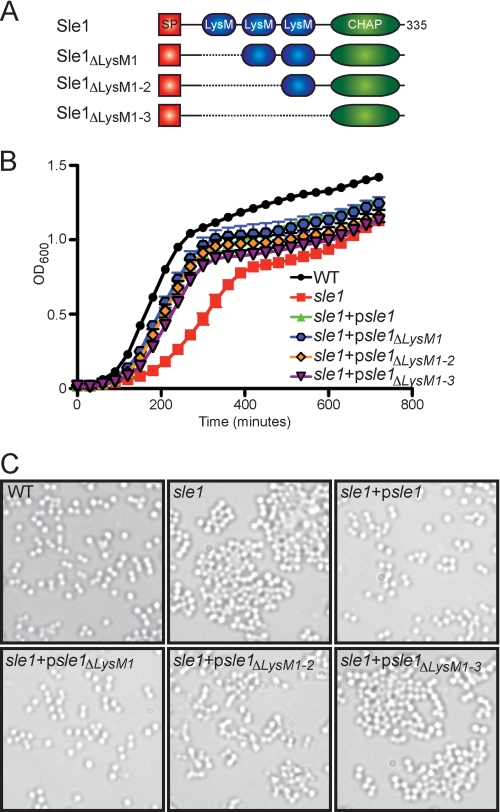

Sle1 Requires LysM Domains for Function

In contrast to the parent strain S. aureus Newman, a mutant with an insertional lesion of the bursa aurealis minitransposon at codon 125 of the 335 codon sle1 open reading frame (sle1::ermC) displays a reduction in bacterial growth and a defect in cross-wall separation (Fig. 7). This is an expected result because sle1 mutants have been reported to form clusters of incompletely separated staphylococci (Fig. 7) (29). Transformation of the sle1 mutant with a plasmid encoding wild-type sle1 (psle1), restored the growth and cell separation phenotypes to wild-type levels (Fig. 7, B and C). Removal of the coding sequence for the first of the three LysM domains in the sle1 gene (psle1ΔLysM1) had no effect on growth and cell separation. In contrast, removal of the first two (psle1ΔLysM1-2) or of all three LysM domains (psle1ΔLysM1–3) diminished or abrogated plasmid complementation for the cell separation phenotype, respectively (Fig. 7C). The psle1ΔLysM1-2 and psle1ΔLysM1–3 plasmids improved growth of sle1 mutant staphylococci, albeit not to the same levels as sle1 (psle1) or sle1 (psle1ΔLysM1) strains (Fig. 7B).

FIGURE 7.

Contribution of the LysM domains to Sle1 function. A, diagram of the structural domains for Sle1 and its expression constructs with in-frame deletions of one, two, or all three LysM domains encoded by plasmid psle1 or psle1ΔLysM1, psle1ΔLysM1-2, and psle1ΔLysM1–3. B, growth of S. aureus Newman (WT) or its sle1 variant with or without psle1 or psle1ΔLysM1, psle1ΔLysM1-2, and psle1ΔLysM1–3 plasmids was measured as the increase in the absorbance at 600-nm light. C, stationary phase aliquots of staphylococcal cultures analyzed in B were viewed by light microscopy and DIC images were captured. Error bars, S.E.

DISCUSSION

The unique spherical architecture of the staphylococcal cell wall is achieved through a replication mechanism whereby peptidoglycan synthesis occurs in the cross-wall (24), a membrane-enclosed compartment into which cell wall synthesis enzymes, lipid II, and YSIRK(G/S) signal peptide-bearing precursor proteins are being trafficked (36, 54). Until synthesis of new peptidoglycan has been completed, the cross-wall compartment is not accessible from the outside of the cell (24). Three secreted polypeptides are known to contribute to cross-wall peptidoglycan splitting and are thought to separate the progeny of staphylococcal replication: Atl (28), Sle1 (29), and LytN (30). The Atl proprotein harbors three central repeat domains (R1-R2-R3) that are cleaved between R2 and R3, thereby generating Atl amidase-R1-R2 and R3-glucosaminidase (27, 32). Both enzymes are deposited in the staphylococcal cell wall envelope in the vicinity of the cross-wall (31, 32). Recent work demonstrated that tagO mutant staphylococci, deficient in the synthesis of WTA, cannot restrict Atl localization to the cross-wall because reporter molecules with R1-R2 domain fusions were found deposited all over the bacterial envelope (34). The inability of tagO mutant staphylococci to properly localize Atl enzymes as well as penicillin-binding proteins involved in cross-linking can explain at least some of the observed defects in cell wall envelope structure and the propensity of tagO mutants for autolysis (34). We show here that inhibition of WTA, either through a tagO mutant or treatment with tunicamycin, causes mislocalization of proteins with LysM domains. Sle1, which harbors three N-terminal LysM domains and a C-terminal CHAP domain that cleaves the N-acetyl-muramoyl-l-alanine bond of peptidoglycan (29, 30), requires at least two of its three LysM domains to properly localize to the cell septum.

Earlier work suggested that the LysM domains of chitinases associate with N-acetylglucosamine or poly-N-acetylglucosamine glycans (42). The solution structure of the LysM domain from E. coli MltD revealed a fold that is composed of two short α-helices packed against two anti-parallel β-strands (75). Ohnuma et al. (42) identified a shallow groove on the surface of the LysM domain from Pteris ryukyuensis chitinase-A that interacts with chitin. There are, however, significant differences in the amino acid sequences of LysM domains from chitinases and peptidoglycan hydrolases, and the chitinase A LysM domain residues involved with poly-N-acetylglucosamine association are not a universal feature of these domains (43). We show here that the LysM domains of staphylococcal Sle1 and LytN associate with the repeating disaccharide β-N-acetylmuramic acid-(1→4)-β-N-acetylglucosamine of staphylococcal peptidoglycan. Lysostaphin-solubilized glycan strands inhibited the association of LysM domains with peptidoglycan if the repeating disaccharides were at least six or eight residues in length and were not modified with WTA at the C6 position of MurNAc. We suspect, but do not know, that the LysM domains of murein hydrolases from other microbial species may also bind to MurNAc-GlcNAc disaccharide repeats because this is a universal structural element of all bacterial peptidoglycans (19, 73).

We note that, when fused to the mCherry reporter, the LysM domains of LytN and Sle1 alone are not sufficient to achieve the same level of association with the cell wall as fusions that encompass also the enzymatic domains of these proteins. Indeed, the LytN-mCherry hybrid that is unable to cleave peptidoglycan displays a similar level of cell wall association as the LysM domain fusions. These data support a model whereby LysM domain binding of murein hydrolases enables cleavage of cross-wall peptidoglycan and exposure of peptidoglycan layers that are not yet decorated with WTA for additional binding to LytN and Sle1. Together the LysM and CHAP domains of Sle1 and LytN may thus catalyze the processive separation of the cross-wall. In support of this model, Sle1 variants lacking the N-terminal LysM domains are unable to fulfill their function. In contrast to Sle1, which is secreted into the extracellular medium and associates with surface exposed peptidoglycan, LytN is secreted directly into the cross-wall and separates the peptidoglycan from the inside (30).

We cannot yet appreciate the molecular or cellular basis for the evolution of two distinct peptidoglycan binding domains in staphylococcal Sle1 and Atl. Both the R1–R3 repeats of Atl and the LysM domains of Sle1 and LytN require peptidoglycan modification with WTA for their proper localization (34). Although the x-ray structure of the amidase domain has recently been reported (76), crystallographic or solution structures of the R1–R3 repeats of Atl have not yet been solved. Further, the peptidoglycan binding sites for the R1–R3 repeats have not yet been characterized. Considering that R1–R3 binding to the envelope is blocked by WTA modification of the glycan strands (34), it seems plausible that the Atl repeat domains may associate with the glycan strands in a manner that is similar to that described here for the LysM domains of Sle1 and LytN.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of our laboratory and Valerie Anderson for discussion and comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health, NIAID, Infectious Disease Branch, Grant AI038897 (to O. S.).

- MurNAc

- N-acetylmuramic acid

- iGlu

- isoglutamyl

- ConA

- concanavalin A-FITC

- DIC

- differential interference contrast

- HF

- hydrofluoric acid

- RP-HPLC

- reversed-phase HPLC

- SOE PCR

- splicing by overlap extension PCR

- WTA

- wall teichoic acid

- PG

- peptidoglycan.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lowy F. D. (1998) Staphylococcus aureus infections. New Engl. J. Med. 339, 520–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chambers H. F., Deleo F. R. (2009) Waves of resistance. Staphylococcus aureus in the antibiotic era. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 629–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Projan S. J., Nesin M., Dunman P. M. (2006) Staphylococcal vaccines and immunotherapy. To dream the impossible dream? Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 6, 473–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Strominger J. L., Izaki K., Matsuhashi M., Tipper D. J. (1967) Peptidoglycan transpeptidase and d-alanine carboxypeptidase. Penicillin-sensitive enzymatic reactions. Fed. Proc. 26, 9–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schneewind O., Fowler A., Faull K. F. (1995) Structure of the cell wall anchor of surface proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. Science 268, 103–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kojima N., Araki Y., Ito E. (1985) Structure of the linkage units between ribitol teichoic acids and peptidoglycan. J. Bacteriol. 161, 299–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Archibald A. R., Armstrong J. J., Baddiley J., Hay J. B. (1961) Teichoic acids and the structure of bacterial walls. Nature 191, 570–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Salton M. R. (1952) Cell wall of Micrococcus lysodeikticus as the substrate of lysozyme. Nature 170, 746–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Park J. T. (1952) Uridine-5′-pyrophosphate derivatives. III. Amino acid-containing derivatives. J. Biol. Chem. 194, 897–904 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Park J. T., Strominger J. L. (1957) Mode of action of penicillin. Science 125, 99–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Higashi Y., Strominger J. L., Sweeley C. C. (1967) Structure of a lipid intermediate in cell wall peptidoglycan synthesis. A derivative of a C55 isoprenoid alcohol. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 57, 1878–1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Matsuhashi M., Dietrich C. P., Strominger J. L. (1965) Incorporation of glycine into the cell wall glycopeptide in Staphylococcus aureus. Role of sRNA and lipid intermediates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 54, 587–594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rohrer S., Ehlert K., Tschierske M., Labischinski H., Berger-Bächi B. (1999) The essential Staphylococcus aureus gene fmhB is involved in the first step of peptidoglycan pentaglycine interpeptide formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 9351–9356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Maidhof H., Reinicke B., Blümel P., Berger-Bächi B., Labischinski H. (1991) femA, which encodes a factor essential for expression of methicillin resistance, affects glycine content of peptidoglycan in methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Bacteriol. 173, 3507–3513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Henze U., Sidow T., Wecke J., Labischinski H., Berger-Bächi B. (1993) Influence of femB on methicillin resistance and peptidoglycan metabolism in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 175, 1612–1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Roberts R. J. (1974) Staphylococcal transfer ribonucleic acids. II. Sequence analysis of isoaccepting glycine transfer ribonucleic acids IA and IB from Staphylococcus epidermidis Texas 26. J. Biol. Chem. 249, 4787–4796 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tipper D. J., Strominger J. L. (1965) Mechanism of action of penicillins. A proposal based on their structural similarity to acyl-d-alanyl-d-alanine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 54, 1133–1141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Higashi Y., Strominger J. L., Sweeley C. C. (1970) Biosynthesis of the peptidoglycan of bacterial cell walls. XXI. Isolation of free C55-isoprenoid alcohol and of lipid intermediates in peptidoglycan synthesis from Staphylococcus aureus. J. Biol. Chem. 245, 3697–3702 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ghuysen J. M., Strominger J. L. (1963) Structure of the cell wall of Staphylococcus aureus, strain Copenhagen. II. Separation and structure of disaccharides. Biochemistry 2, 1119–1125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anderson J. S., Matsuhashi M., Haskin M. A., Strominger J. L. (1965) Lipid-phosphoacetylmuramyl-pentapeptide and Lipid-phosphodisaccharide-pentapeptide. Presumed membrane transport intermediates in cell wall synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 53, 881–889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blumberg P. M., Strominger J. L. (1972) Isolation by covalent affinity chromatography of the penicillin-binding components from membranes of Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 69, 3751–3755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Giesbrecht P., Wecke J., Reinicke B. (1976) On the morphogenesis of the cell wall of staphylococci. Int. Rev. Cytol. 44, 225–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lutkenhaus J. (1993) FtsZ ring in bacterial cytokinesis. Mol. Microbiol. 9, 403–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Giesbrecht P., Kersten T., Maidhof H., Wecke J. (1998) Staphylococcal cell wall. Morphogenesis and fatal variations in the presence of penicillin. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 1371–1414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tzagoloff H., Novick R. (1977) Geometry of cell division in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 129, 343–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zapun A., Vernet T., Pinho M. (2008) The different shapes of cocci. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32, 345–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sugai M., Komatsuzawa H., Akiyama T., Hong Y. M., Oshida T., Miyake Y., Yamaguchi T., Suginaka H. (1995) Identification of endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase and N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase as cluster-dispersing enzymes in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 177, 1491–1496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Oshida T., Sugai M., Komatsuzawa H., Hong Y. M., Suginaka H., Tomasz A. (1995) A Staphylococcus aureus autolysin that has an N-acetylmuramoyl-l-alanine amidase domain and an endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase domain. Cloning, sequence analysis, and characterization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 285–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kajimura J., Fujiwara T., Yamada S., Suzawa Y., Nishida T., Oyamada Y., Hayashi I., Yamagishi J., Komatsuzawa H., Sugai M. (2005) Identification and molecular characterization of an N-acetylmuramyl-l-alanine amidase Sle1 involved in cell separation of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 58, 1087–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Frankel M. B., Hendrickx A. P., Missiakas D. M., Schneewind O. (2011) LytN, a murein hydrolase in the cross-wall compartment of Staphylococcus aureus, is involved in proper bacterial growth and envelope assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 32593–32605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baba T., Schneewind O. (1998) Targeting of muralytic enzymes to the cell division site of Gram-positive bacteria. Repeat domains direct autolysin to the equatorial surface ring of Staphylococcus aureus. EMBO J. 17, 4639–4646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Komatsuzawa H., Sugai M., Nakashima S., Yamada S., Matsumoto A., Oshida T., Suginaka H. (1997) Subcellular localization of the major autolysin, ATL, and its processed proteins in Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiol. Immunol. 41, 469–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weidenmaier C., Kokai-Kun J. F., Kristian S. A., Chanturiya T., Kalbacher H., Gross M., Nicholson G., Neumeister B., Mond J. J., Peschel A. (2004) Role of teichoic acids in Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization, a major risk factor in nosocomial infections. Nat. Med. 10, 243–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schlag M., Biswas R., Krismer B., Kohler T., Zoll S., Yu W., Schwarz H., Peschel A., Götz F. (2010) Role of staphylococcal wall teichoic acid in targeting the major autolysin Atl. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 864–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rigden D. J., Jedrzejas M. J., Galperin M. Y. (2003) Amidase domains from bacterial and phage autolysins define a family of γ-dl-glutamate-specific amidohydrolases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 28, 230–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. DeDent A., Bae T., Missiakas D. M., Schneewind O. (2008) Signal peptides direct surface proteins to two distinct envelope locations of Staphylococcus aureus. EMBO J. 27, 2656–2668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Garvey K. J., Saedi M. S., Ito J. (1986) Nucleotide sequence of Bacillus phage φ 29 genes 14 and 15: homology of gene 15 with other phage lysozymes. Nucleic Acids Res. 14, 10001–10008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Buist G., Kok J., Leenhouts K. J., Dabrowska M., Venema G., Haandrikman A. J. (1995) Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding the major peptidoglycan hydrolase of Lactococcus lactis, a muramidase needed for cell separation. J. Bacteriol. 177, 1554–1563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steen A., Buist G., Horsburgh G. J., Venema G., Kuipers O. P., Foster S. J., Kok J. (2005) AcmA of Lactococcus lactis is an N-acetylglucosaminidase with an optimal number of LysM domains for proper functioning. FEBS J. 272, 2854–2868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Carroll S. A., Hain T., Technow U., Darji A., Pashalidis P., Joseph S. W., Chakraborty T. (2003) Identification and characterization of a peptidoglycan hydrolase, MurA, of Listeria monocytogenes, a muramidase needed for cell separation. J. Bacteriol. 185, 6801–6808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mesnage S., Chau F., Dubost L., Arthur M. (2008) Role of N-acetylglucosaminidase and N-acetylmuramidase activities in Enterococcus faecalis peptidoglycan metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 19845–19853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ohnuma T., Onaga S., Murata K., Taira T., Katoh E. (2008) LysM domains from Pteris ryukyuensis chitinase-A. A stability study and characterization of the chitin-binding site. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 5178–5187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Buist G., Steen A., Kok J., Kuipers O. P. (2008) LysM, a widely distributed protein motif for binding to (peptido)glycans. Mol. Microbiol. 68, 838–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lerouge P., Roche P., Faucher C., Maillet F., Truchet G., Promé J. C., Dénarié J. (1990) Symbiotic host specificity of Rhizobium meliloti is determined by a sulfated and acylated glucosamine oligosaccharide signal. Nature 344, 781–784 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Radutoiu S., Madsen L. H., Madsen E. B., Jurkiewicz A., Fukai E., Quistgaard E. M., Albrektsen A. S., James E. K., Thirup S., Stougaard J. (2007) LysM domains mediate lipochitin-oligosaccharide recognition and Nfr genes extend the symbiotic host range. EMBO J. 26, 3923–3935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Radutoiu S., Madsen L. H., Madsen E. B., Felle H. H., Umehara Y., Grønlund M., Sato S., Nakamura Y., Tabata S., Sandal N., Stougaard J. (2003) Plant recognition of symbiotic bacteria requires two LysM receptor-like kinases. Nature 425, 585–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gründling A., Schneewind O. (2007) Synthesis of glycerol phosphate lipoteichoic acid in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 8478–8483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baba T., Bae T., Schneewind O., Takeuchi F., Hiramatsu K. (2008) Genome sequence of Staphylococcus aureus strain Newman and comparative analysis of staphylococcal genomes. Polymorphism and evolution of two major pathogenicity islands. J. Bacteriol. 190, 300–310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bae T., Banger A. K., Wallace A., Glass E. M., Aslund F., Schneewind O., Missiakas D. M. (2004) Staphylococcus aureus virulence genes identified by bursa aurealis mutagenesis and nematode killing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 12312–12317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kreiswirth B. N., Löfdahl S., Betley M. J., O'Reilly M., Schlievert P. M., Bergdoll M. S., Novick R. P. (1983) The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by a prophage. Nature 305, 709–712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Gründling A., Missiakas D. M., Schneewind O. (2006) Staphylococcus aureus mutants with increased lysostaphin resistance. J. Bacteriol. 188, 6286–6297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kern J., Ryan C., Faull K., Schneewind O. (2010) Bacillus anthracis surface-layer proteins assemble by binding to the secondary cell wall polysaccharide in a manner that requires csaB and tagO. J. Mol. Biol. 401, 757–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Reeder W. J., Ekstedt R. D. (1971) Study of the interaction of concanavalin A with staphylocccal teichoic acids. J. Immunol. 106, 334–340 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Atilano M. L., Pereira P. M., Yates J., Reed P., Veiga H., Pinho M. G., Filipe S. R. (2010) Teichoic acids are temporal and spatial regulators of peptidoglycan cross-linking in Staphylococcus aureus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 18991–18996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. de Jonge B. L., Chang Y. S., Gage D., Tomasz A. (1992) Peptidoglycan composition of a highly methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain. The role of penicillin binding protein 2A. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 11248–11254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Harrington C. R., Baddiley J. (1985) Biosynthesis of wall teichoic acids in Staphylococcus aureus H, Micrococcus varians, and Bacillus subtilis W23. Involvement of lipid intermediates containing the disaccharide N-acetylmannosaminyl N-acetylglucosamine. Eur. J. Biochem. 153, 639–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Yokoyama K., Miyashita T., Araki Y., Ito E. (1986) Structure and functions of linkage unit intermediates in the biosynthesis of ribitol teichoic acids in Staphylococcus aureus H and Bacillus subtilis W23. Eur. J. Biochem. 161, 479–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Soldo B., Lazarevic V., Karamata D. (2002) tagO is involved in the synthesis of all anionic cell wall polymers in Bacillus subtilis 168. Microbiology 148, 2079–2087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. McArthur H. A., Roberts F. M., Hancock I. C., Baddiley J. (1978) Lipid intermediates in the biosynthesis of the linkage unit between teichoic acids and peptidoglycan. FEBS Lett. 86, 193–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mauël C., Young M., Margot P., Karamata D. (1989) The essential nature of teichoic acids in Bacillus subtilis as revealed by insertional mutagenesis. Mol. Gen. Genet. 215, 388–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lazarevic V., Karamata D. (1995) The tagGH operon of Bacillus subtilis 168 encodes a two-component ABC transporter involved in the metabolism of two wall teichoic acids. Mol. Microbiol. 16, 345–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Coley J., Archibald A. R., Baddiley J. (1976) A linkage unit joining peptidoglycan to teichoic acid in Staphylococcus aureus H. FEBS Lett. 61, 240–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kawai Y., Marles-Wright J., Cleverley R. M., Emmins R., Ishikawa S., Kuwano M., Heinz N., Bui N. K., Hoyland C. N., Ogasawara N., Lewis R. J., Vollmer W., Daniel R. A., Errington J. (2011) A widespread family of bacterial cell wall assembly proteins. EMBO J. 30, 4931–4941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Poxton I. R., Tarelli E., Baddiley J. (1978) The structure of C-polysaccharide from the walls of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Biochem. J. 175, 1033–1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Liu T. Y., Gotschlich E. C. (1967) Muramic acid phosphate as a component of the mucopeptide of Gram-positive bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 242, 471–476 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. D'Elia M. A., Henderson J. A., Beveridge T. J., Heinrichs D. E., Brown E. D. (2009) The N-acetylmannosamine transferase catalyzes the first committed step of teichoic acid assembly in Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 191, 4030–4034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. D'Elia M. A., Pereira M. P., Chung Y. S., Zhao W., Chau A., Kenney T. J., Sulavik M. C., Black T. A., Brown E. D. (2006) Lesions in teichoic acid biosynthesis in Staphylococcus aureus lead to a lethal gain of function in the otherwise dispensable pathway. J. Bacteriol. 188, 4183–4189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gründling A., Schneewind O. (2006) Cross-linked peptidoglycan mediates lysostaphin binding to the cell wall envelope of Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 188, 2463–2472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Walsh C. T. (1993) Vancomycin resistance. Decoding the molecular logic. Science 261, 308–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Chen W., Qu D., Zhai L., Tao M., Wang Y., Lin S., Price N. P., Deng Z. (2010) Characterization of the tunicamycin gene cluster unveiling unique steps involved in its biosynthesis. Protein Cell 1, 1093–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Hancock I. C., Wiseman G., Baddiley J. (1976) Biosynthesis of the unit that links teichoic acid to the bacterial wall. Inhibition by tunicamycin. FEBS Lett. 69, 75–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Yokogawa K., Kawata S., Nishimura S., Ikeda Y., Yoshimura Y. (1974) Mutanolysin, bacteriolytic agent for cariogenic Streptococci. Partial purification and properties. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 6, 156–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ghuysen J. M. (1968) Use of bacteriolytic enzymes in determination of wall structure and their role in cell metabolism. Bacteriol. Rev. 32, 425–464 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Schindler C. A., Schuhardt V. T. (1964) Lysostaphin. A new bacteriolytic agent for the staphylococcus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 51, 414–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Bateman A., Bycroft M. (2000) The structure of a LysM domain from E. coli membrane-bound lytic murein transglycosylase D (MltD). J. Mol. Biol. 299, 1113–1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Zoll S., Pätzold B., Schlag M., Götz F., Kalbacher H., Stehle T. (2010) Structural basis of cell wall cleavage by a staphylococcal autolysin. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1000807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]