Abstract

Human neurodegenerative diseases possess the temporal hallmark of afflicting the elderly population. Hence, aging is among the most significant factors to impinge on disease onset and progression1, yet little is known of molecular pathways that connect these processes. Central to understanding this connection is to unmask the nature of pathways that functionally integrate aging, chronic maintenance of the brain and modulation of neurodegenerative disease. microRNAs (miRNA) are emerging as critical players in gene regulation during development, yet their role in adult-onset, age-associated processes are only beginning to be revealed. Here we report that the conserved miRNA miR-34 regulates age-associated events and long-term brain integrity in Drosophila, presenting such a molecular link between aging and neurodegeneration. Fly miR-34 expression is adult-onset, brain-enriched and age-modulated. Whereas miR-34 loss triggers a gene profile of accelerated brain aging, late-onset brain degeneration and a catastrophic decline in survival, miR-34 upregulation extends median lifespan and mitigates neurodegeneration induced by human pathogenic polyglutamine (polyQ) disease protein. Some of the age-associated effects of miR-34 require adult-onset translational repression of Eip74EF, an essential ETS domain transcription factor involved in steroid hormone pathways. These studies indicate that miRNA-dependent pathways may impact adult-onset, age-associated events by silencing developmental genes that later have a deleterious influence on adult life cycle and disease, and highlight fly miR-34 as a key miRNA with a role in this process

Recent evidence reveals that miRNA pathways are important in the adult nervous system, notably in maintenance of neurons and in regulation of genes and pathways associated with neurodegenerative disease2,3. Given these findings, we considered that there may be a fundamental role for select miRNAs in aging. We examined flies carrying a hypomorphic mutation in loquacious (loqs), a key gene in fly miRNA processing4 (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Flies bearing the loqsf00791 mutation were viable, but detailed examination indicated a significantly shortened lifespan (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Further analysis indicated that loqsf00791 flies showed late-onset brain morphological deterioration: although normal as young adults, by 25d loqsf00791 flies developed large vacuoles in the retina and lamina of the brain (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Although developmental processes may contribute to shortened lifespan, the adult-onset brain degeneration of loqsf00791 mutants indicated that one or more specific miRNAs may be critically involved in age-associated events impacting long-term brain integrity.

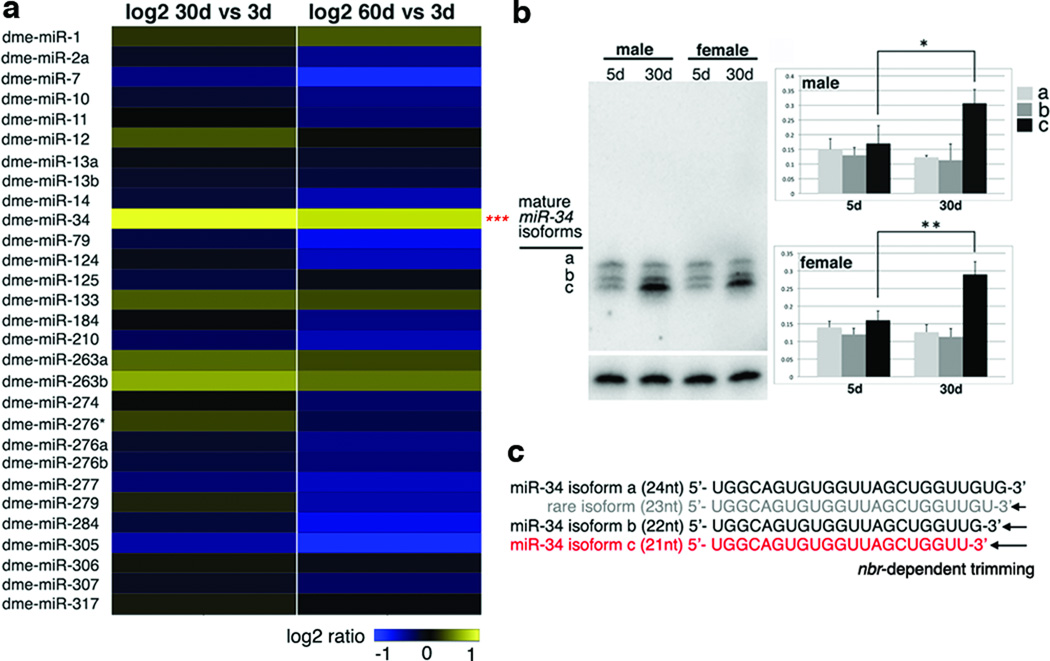

To explore this question, we determined whether specific miRNAs displayed age-modulated expression in the brain. RNA was isolated from dissected brains of adult flies of young (3d), mid (30d) and old time points (60d). Using an array for Drosophila miRNAs, 29 were expressed in the adult brain (Fig. 1a). Whereas most miRNAs maintained a steady level or decreased with age, one miRNA, miR-34, increased (Fig. 1a). Small RNA northern analysis confirmed that miR-34 expression was barely detectable during development, but became high in the adult and was further upregulated with age (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). miR-34 expression was affected in loqsf00791 (Supplementary Fig. 1d). miR-34 falls into a category of Drosophila miRNAs whose processing requires the exoribonuclease nibbler (nbr)5,6 In the adult, mature miR-34 displayed three major differentially-sized forms (21nt, 22nt and 24nt) with a uniform 5’end, descending by single nucleotides at the 3'end which result from nbr-mediated trimming; only isoform c became upregulated with age (Supplementary Fig. 2c and Fig. 1b, c; also5–7).

Figure 1. Drosophila miR-34 is upregulated with age.

a. Heat map of fold-change of Drosophila miRNAs in brains aged 3d, 30d and 60d. 29 miRNAs (shown) were flagged present of a total of 78. One-way analysis of variance defined significance for each miRNA over all time points (***=p <0.001; n=3 replicates). Genotype: iso31

b. Fly miR-34 isoform-c shows age-modulated expression in fly heads. Left panels, miR-34 shows three major mature forms (labeled a, b, and c), but only isoform c increases with age. Right panels, quantification of miR-34 isoforms with age (top: male; bottom: female). n = 3 independent experiments; signal density of all isoforms normalized at the same time point to 2S rRNA loading control. (*=p < 0.01, **=p < 0.001, one-way analysis of variance, with post test: Tukey's multiple comparison test). Genotype: 5905.

c. Sequences of miR-34 isoforms are generated through nbr-dependent 3'end trimming.

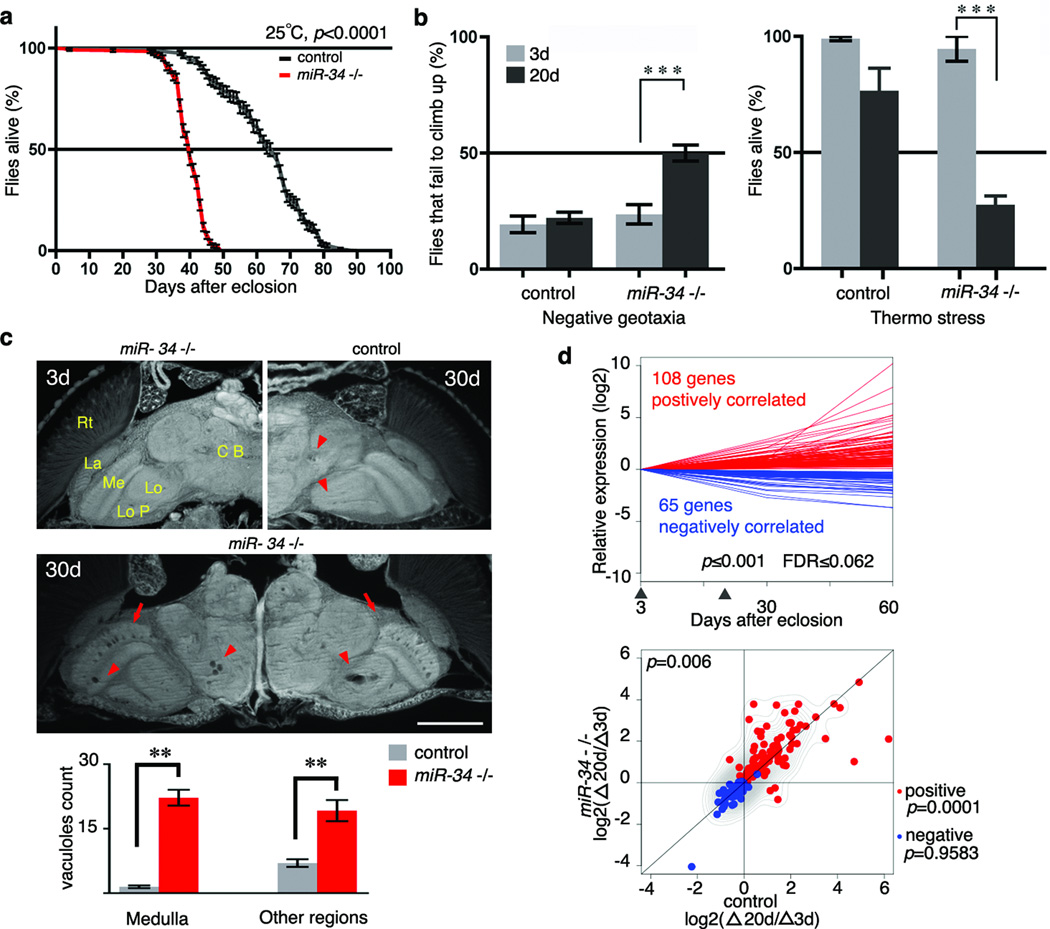

miR-34 is a markedly conserved miRNA, with identical seed sequence of orthologues among fly, C elegans, mouse, and human (Supplementary Fig. 2d). To define miR-34 function, flies deleted for the gene were generated (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The resulting miR-34 mutant flies retained normal wild-type expression of neighboring genes, but selectively lacked miR-34 (Supplementary Fig. 3b, c). To carefully interrogate age-associated phenotypes, we generated miR-34 null flies in the same uniform homogeneous genetic background (see Methods). miR-34 mutants displayed no obvious developmental defects, consistent with its adult-onset expression. However, detailed examination of adult animals indicated that miR-34 mutants, although showing normal adult appearance and early survival, displayed a catastrophic decline in viability just after 30d (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Table 4). Analysis of age-associated functions revealed that young mutants (3d) had normal locomotion and stress resistance, but by 20d the mutants had dramatic climbing deficits and were strikingly stress-sensitive compared to age-matched controls (Fig. 2b). Since miR-34 expression was brain-enriched, we also examined the brain. Typically, older flies show sporadic, age-correlated vacuoles in the brain—a morphological hallmark of neural deterioration8. miR-34 mutants were born with normal brain morphology, but showed dramatic vacuolization with age, indicative of loss of brain integrity (Fig. 2c). Rescue with a 9 kb genomic DNA fragment containing miR-34 and its endogenous cis-regulatory elements (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b) partially restored the age-associated expression of miR-34 to miR-34 null flies in the same homogeneous genetic background (Supplementary Fig. 3d). Although rescue was not complete, indicative of a complexity in genomic elements that regulate miR-34, rescue was sufficient to mitigate the mutant effects indicating that miR-34 function normally underlies these age-associated aspects (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2. miR-34 modulates age-associated processes.

a. miR-34 mutant flies have a shortened lifespan (control: 64d median, 90d maximal lifespan; miR-34: 40d medium, 64d maximal lifespan; p<0.001, log-rank test). Mean ± s.e., n≥240 male flies per curve. Genotypes: control: 5905. miR-34 −/−: miR-34 null-1 in 5905 homogenous genetic background.

b. miR-34 mutant flies have late-onset behavioral deficits. Left panel, for locomotion behavior, miR-34 mutant flies have normal climbing at 3d. At 20d, 50±3.4% miR-34 mutant flies fail to climb; in contrast, only 22.1±2.4% of control flies have defective climbing. Mean ± s.e.m. of 3 experiments, n=120–140 male flies per experiment. Right panel, for stress resistance, miR-34 mutant flies have normal resistance to heat stress at 3d. miR-34 mutant flies become strikingly sensitive to heat shock with age, such that at 20d, only 27.5±3.8% survive after heat stress. In contrast, 76.7±9.6% of control flies survive after the same treatment. Mean ± s.e.m. of 3 experiments, n=120–140 male flies. *** =p<0.0001 (two-way analysis of variance). Genotypes as in a.

c. miR-34 mutant flies show age-associated brain degeneration. Top left panel, miR-34 mutant flies have normal brain morphology at 3d. Major anatomical structures: CB (central brain), Lo (lobula), LoP (lobula plate), Me (medulla), La (lamina) and Rt (retina). At 3d, control flies have normal brain morphology (not shown), but develop a small number of sporadic vacuoles at 30d (top right panel, arrowheads). Middle panel, aged miR-34 mutants (30d) show striking vacuoles in the medulla (arrows) and other regions of the brain (arrowheads). Bottom, the number of vacuoles in miR-34 mutants is significantly higher than in controls (22.2± 1.8 vs 1.5±0.3 in medulla; 19.2±2.5 vs 7.0±0.9 in other regions of the brain; **=p < 0.001, one-way analysis of variance, with post test: Tukey's multiple comparison test). Mean ± s.e.m., n=10 independent male fly brains. Genotypes as in a. Scale bar: 0.1mm.

d. miR-34 mutant flies have a transcriptional profile indicative of accelerated aging. Top panel, 173 age-correlated probesets were defined from a transcriptional profile of fly brains at 3d, 30d, and 60d of age. Arrowheads indicate time points (3d and 20d) at which miR-34 mutants and controls were compared. Genotype: iso31 flies used for transcriptional profiles of normal aging brains. n=3 biological replicates for each time point. p≤0.001, FDR≤0.062, linear regression model. Bottom panel, scatter plot illustrates the relative expression of 173 probesets, which shows a significant difference between miR-34 mutants and age-matched controls (p=0.006, two-sample, paired Wilcoxon test). Whereas the pattern for positively-correlated probesets (red), indicated by the contour lines, is significantly different (p=0.0001) between the two genotypes, and tend to show higher expression in miR-34 mutants compared to controls, it is not for negatively-correlated probesets (blue) (p=0.9583).). Contour lines indicate that positively correlated probesets tend to show higher expression in miR-34 mutants compared to controls. Genotypes as in a. n=5 biological replicates for each time point.

These data indicated that miR-34 mutants were normal as young adults, but with age developed deficits reflective of much older animals, including loss of locomotion, stress sensitivity, and brain deterioration, coupled with shortened lifespan. We therefore hypothesized that loss of miR-34 accelerated brain aging. To address this, we transcriptionally profiled the fly brain (3d, 30d, and 60d) from wild type animals. Based on a linear regression model9, we extracted 173 probesets from this profile whose expression was tightly correlated with the progression of normal aging (Fig. 2d, Supplementary Tables 2 and 3). We next made another set of brain transcriptional profiles for miR-34 mutants and controls of matched chronological age (3d and 20d). We measured relative changes of these probesets between 3d and 20d within each genotype, and compared the extent of such changes between miR-34 mutants and controls. This indicated that the overall pattern of these probesets was significantly different between the two genotypes (p=0.006, two-sample, paired Wilcoxon test; Fig. 2d). In particular, the majority of positively-correlated probesets displayed a faster pace of increase in miR-34 mutants compared to controls—thus showing accelerated age-associated expression changes in miR-34 mutants (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Table 2). This result, combined with the physiological and histological evidence of more rapid loss of age-associated functions, suggested that miR-34 mutants were undergoing accelerated brain aging.

miRNAs function by binding to the 3’UTRs of target mRNAs and often result in downregulation of protein translation. We therefore reasoned that age-associated activities of miR-34 might be mediated through silencing of critical targets that have a negative impact on the adult animal. miRNA-target prediction algorithms indicated miR-34 binding sites within 3’UTR of the Eip74EF gene; significantly, these binding sites were conserved in the orthologous Eip74EF genes from different Drosophila species (Supplementary Fig. 4a). We confirmed the miR-34 interaction through mutations in the seed sequences of the predicted miR-34 binding sites in the 3’UTR of the Eip74EF mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 4b). The Eip74EF gene is a component of steroid hormone signaling pathways. Whereas such pathways have generally been studied for effects during development, data have implicated these pathways in lifespan regulation10.

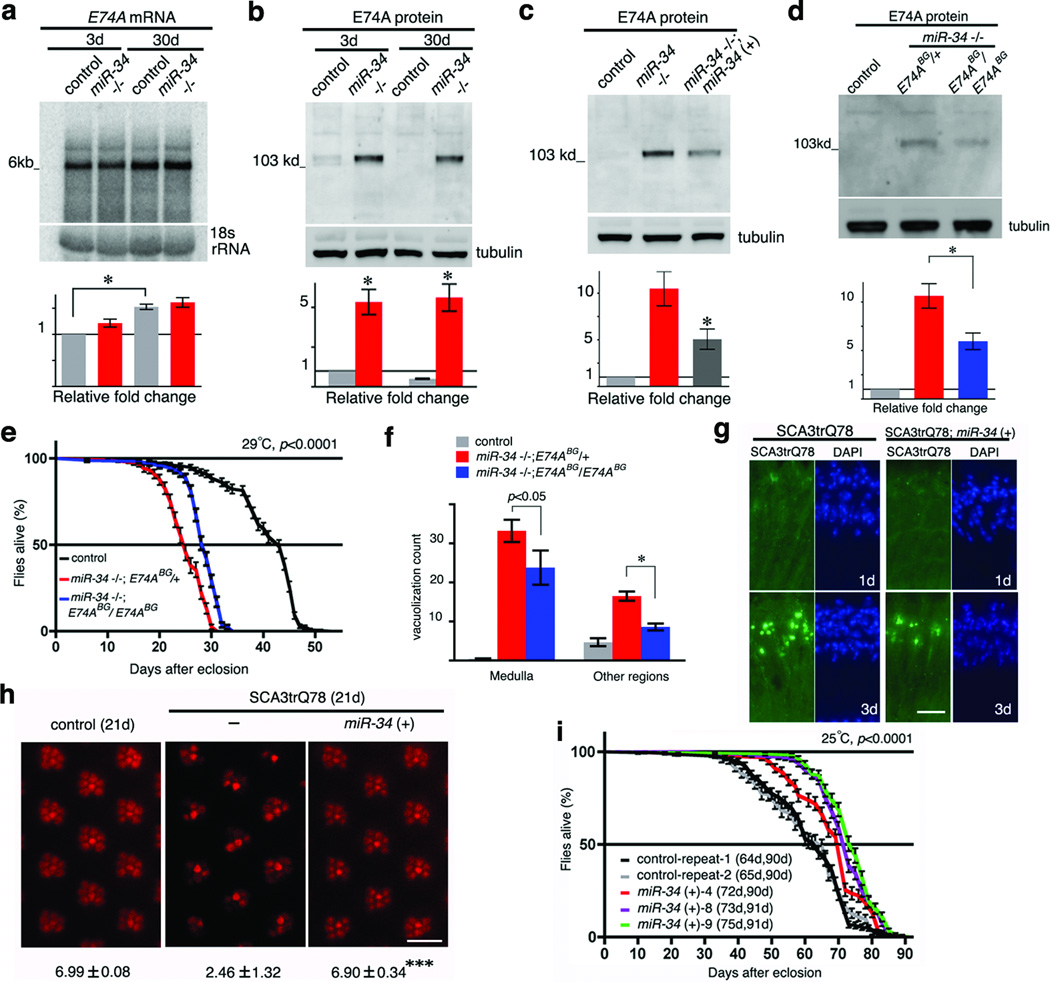

The Eip74EF gene encodes two major protein isoforms, E74A and E74B (referred to as the E74A and E74B genes, respectively11); the isoforms share the same 3’UTR (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Northern blots indicated that transcription of E74A, but not E74B, persisted in adults, overlapping the time period when miR-34 is expressed (Supplementary Fig. 4c). Given this, we focused on E74A as a regulated target of miR-34 in the adult. Despite robust expression of the mRNA transcript, the E74A protein was expressed at low levels in adult heads throughout lifespan (Fig. 3a, b and Supplementary Fig. 4d). In flies lacking miR-34, E74A protein was dramatically increased (Fig. 3b); E74A was also de-regulated in the loqsf00791 mutant (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Genomic rescue of miR-34 mitigated this de-regulation of the E74A protein (Fig. 3c). Fine temporal analysis indicated that the E74A protein was highly expressed in young flies, but underwent a dramatic decrease within a 24h time window (Supplementary Fig. 5). This temporal pattern appeared to be mutually exclusive to that of miR-34 (see Supplementary Fig. 2a). Moreover, in flies lacking miR-34, the downregulation of E74A protein during this critical period was dampened (Supplementary Fig. 5). This evidence suggests that adult-onset expression of miR-34 functions at least in part to attenuate E74A protein expression in the young adult, and maintain that repression through adulthood (Supplementary Fig. 4d).

Figure 3. The Drosophila Eip74EF gene is a target of miR-34 in modulation of the aging process.

a. E74A mRNA is robustly expressed in the adult and unchanged between age-matched controls and miR-34 mutants. In control flies, E74A mRNA is significantly upregulated in 30d compared to 3d animals. RNA was from male heads. Mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 independent experiments; signal density of E74A mRNA normalized to 18S rRNA loading control (*=p < 0.01, one-way analysis of variance, with post test: Tukey's multiple comparison test). Genotypes: control: 5905. miR-34 −/−: miR-34 null-1 in 5905 homogenous genetic background.

b. E74A protein is deregulated in miR-34 mutants. Protein was from male heads. Mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 independent experiments; signal density of E74A protein normalized to tubulin loading control (*=p < 0.01, one-way analysis of variance, with post test: Tukey's multiple comparison). Genotypes as in a.

c. De-regulation of E74A protein is diminished in miR-34 rescue flies. Protein was from male heads. Mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 independent experiments; signal density normalized to tubulin loading control (*=p < 0.05, one-way analysis of variance, with post test: Tukey's multiple comparison test). Genotypes: control: 5905. miR-34 −/−: miR-34 null-1 in 5905 homogenous genetic background. miR-34 −/−; miR-34 (+): miR-34 genomic rescue in miR-34 null-1 in 5905 homogenous genetic background.

d. miR-34 mutants homozygous for the E74ABG01805 allele have lower levels of E74A protein. Protein was from male heads of 20d flies raised at 29°C. Mean ± s.e.m., n = 3 independent experiments; signal density normalized to tubulin loading control (*=p < 0.01, one-way analysis of variance, with post test: Tukey's multiple comparison test). Genotypes: control: 5905. miR-34−/−, E74ABG/+: E74ABG01805/+, miR-34 null-1 in 5905 homogenous genetic background. miR-34−/−, E74ABG/E74ABG: E74ABG01805/E74ABG01805, miR-34 null-1 in 5905 homogenous genetic background.

e–f. Reducing E74A protein levels in the adult mitigates age-related defects of miR-34 mutants.miR-34 mutants also homozygous for the E74ABG01805 show rescued lifespan (e) and brain morphology (f), compared to miR-34 mutants heterozygous for the E74ABG01805 (these flies have a lifespan that is the same as miR-34 mutants alone; see Supplemental Table 4). Flies raised at 29°C. Lifespan: p<0.0001 (log-rank test). Mean ± s.e., n>=150 male flies. Brain vacuoles: *=p < 0.01 (one-way analysis of variance, with post test: Tukey's multiple comparison test). Mean ± s.e.m.,, n=10 independent male animals. Genotypes as in d.

g. Upregulation of miR-34 reduces accumulation of pathogenic polyQ protein inclusions. Left panels, in the retina of flies expressing SCA3trQ78 alone, pathogenic polyQ protein is initially diffuse (1d, top), but gradually accumulates into nuclear inclusions (3d, bottom). Right panels, upregulation of miR-34 reduces inclusion formation. DAPI staining highlights nuclei. 3d controls show 53.75 ± 12.55 inclusions in a retinal section, vs 23.67 ± 7.57 with miR-34 upregulation; mean ± s.d., n≥3 cryosections from independent male animals; p<0.01 (t-test). Genotypes: SCA3trQ78 is w+; rh1-gal4, UAS-SCA3trQ78/+. SCA3trQ78; miR34 (+) is w+; rh1-gal4, SCA3trQ78/+; UAS-miR-34/+. Scale bar: 0.05mm.

h. Upregulation of miR-34 prevents neural degeneration. At 21d, male flies expressing SCA3trQ78 show a dramatic loss of photoreceptor neuronal integrity (middle panel), with an average of only 2.46 ±1.32 photoreceptors per ommatidium remaining by pseudopupil analysis. Flies with upregulated miR-34 (right panel) retain 6.90 ± 0.34 photoreceptors per ommatidium. Control (left panel) and upregulation of miR-34 alone (not shown) have normal photoreceptor numbers per ommatidium. Mean ± s.d., n= 619, 722 and 700 ommatidia, for SCA3trQ78, SCA3trQ78; miR-34 (+) and control, respectively; ***=p< 0.0001 (one-way analysis of variance, with Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). Genotypes as in b; control: w+; rh1-gal4/+. Scale bar: 0.05mm.

i. Flies with upregulated miR-34 (color) have an extended median lifespan compared to control flies (black and grey curves for repeats 1 and 2, respectively) (log-rank test). Lifespan result for each genotype is indicated in median and maximal days. Mean ± s.e., n>=150 male flies per genotype, 25°C. Three independent miR-34 genomic transgenic lines (4, 8, 9) were analyzed. Genotypes: control: 5905, miR-34 (+): miR-34 genomic rescue in 5905 homogenous genetic background.

We next determined if deregulated expression of E74A protein contributed to the age-associated defects in miR-34 mutants. Because E74A function is essential during development, with strong mutations leading to pre-adult lethality11, we used the mild, but viable E74ABG01805 hypomorphic mutation (Supplementary Fig. 4a). When the E74ABG01805 mutation was combined with miR-34 mutant flies in the same homogenous genetic background, proper regulation of E74A protein partially restored (Fig. 3d), and age-associated defects due to loss of miR-34, including shortened lifespan and brain vacuolization, were mitigated (Fig. 3e, f; E74ABG01805 mutants alone have a normal lifespan (Supplementary Fig. 6a)). To further assess the adult activity of E74A, we upregulated E74A in the adult with an E74A transgene that lacks miR-34 binding sites driven by a temperature-sensitive promoter12. At 29°C, these flies demonstrated increased levels of E74A expression in the adult (Supplementary Fig. 6b). Strikingly, these animals also showed late-onset brain degeneration (Supplementary Fig. 6c), and a significantly shortened lifespan (Supplementary Fig. 6d). These data indicate that deregulated expression of E74A negatively impacts normal aging, and that one function of miR-34 is to silence E74A in the adult to prevent the adult-stage deleterious activity of E74A on brain integrity and viability.

Intriguingly, in the course of these studies, we noted that miR-34 mutants also displayed a defect in protein misfolding—a molecular process implicated in aging and common to many human neurodegenerative diseases13. Whereas normally with age, the fly brain accumulates a low level of inclusions that immunostain for stress chaperones like Hsp70/Hsc70, miR-34 mutants showed a striking increase compared to control flies of matched age (30d) (Supplementary Fig. 7). Given that miR-34 increases with age, and loss showed altered chaperone accumulation, we tested although found no evidence that miR-34 itself is upregulated by stresses like heat shock or oxidative toxins (data not shown). However, that loss of miR-34 caused an increase in protein misfolding raised the possibility that upregulating miR-34 may mitigate disease-associated protein misfolding. In Drosophila, expression of a pathogenic ataxin-3 polyQ disease protein (SCA3tr-Q78) leads to inclusion formation, a decrease in polyQ protein solubility, and progressive neural loss14 (Supplementary Fig. 8a). Upregulation of miR-34 dramatically mitigated polyQ degeneration, such that inclusion formation was slowed, the protein retained greater solubility, and neural degeneration was suppressed (Fig. 3g, h; Supplementary Fig. 8b, c, d). Lowering E74A expression by heterozygous reduction in flies expressing pathogenic polyQ protein revealed a minimal effect (data not shown) indicating E74A may not be a target of miR-34 activity in this process. However, our studies with E74A were of necessity limited to hypomorphic alleles that may not uncover the full extent of E74A function mediated by miR-34. Further, additional targets of miR-34 may be involved in different aspects of miR-34-directed pathways, including disease.

Given this effect to mitigate disease-associated neural toxicity with upregulation of miR-34, and that miR-34 expression naturally increases with age, we investigated whether enhanced expression of miR-34 in wild-type flies could modulate the aging process. We increased miR-34 dosage in wild-type animals with genomic rescue transgenes, which express miR-34 under its endogenous regulatory elements (see Supplementary Fig. 2a). Analysis of multiple independent transgenics in the same genetic background with that of control, indicated that upregulation of miR-34 levels with genomic constructs (~ 20%, Supplementary Fig. 3d) promoted median survival rate by ~10% compared to wild-type (Fig. 3i; other traits, such as the occurrence of brain vacuolization, despite being an age-associated phenomenon, are sporadic and low in normal flies, thus were difficult to assess). Thus, upregulation of miR-34 can protect from neurodegenerative disease and extend median lifespan.

In summary, our findings suggest that miR-34 in Drosophila presents a key miRNA that couples long-term maintenance of the brain with healthy aging of the organism. miR-34 activity, enhanced by its age-modulated expression and processing, is critically involved in silencing of the E74A gene through adulthood and in modulation of protein homeostasis with age, as well as in polyQ disease. Select neural cell types may be especially vulnerable in aging and disease15; miR-34 function may impact the integrity or activity of these systems. Intriguingly, E74A appears to confer sharply opposing function on animal fitness at different life stages, being essential during pre-adult development11, but harmful to the adult during aging (this study). This biological property—of a gene being beneficial at one life stage, but damaging at another—is referred to as antagonistic pleiotropy16. Genes associated with antagonistic pleiotropy are likely to be evolutionarily retained due to their earlier beneficial function17. Their adult-onset activities, however, antagonize the aging process if not properly regulated. miRNA pathways provide a tantalizing mechanism by which to suppress potentially deleterious age-related activities of such genes; a number of miRNAs have been noted to show age-modulated expression and activity18,19. Roles of select miRNAs normally expressed in the adult may be of evolutionary advantage to tune-down events that promote age-associated decline and potentially disease, in order to prolong healthy lifespan and longevity. Upregulation of lin-4, a C elegans miRNA with a known developmental role, extends nematode lifespan18, raising the possibility that this upregulation, like the natural increase of miR-34 in Drosophila, functions to silence genes that negatively impact aging and potentially promote disease. Provocatively, miR-34 is elevated with age in C elegans19,20, and mammalian miR-34 orthologues are highly expressed in the adult brain21 and have also been noted to increase with age and be misregulated in degenerative disease in humans22–26. Current data regarding miR-34 function indicate that it is neutral or adverse in C elegans19,27 , and can be either protective or contributory to age-associated events in vertebrates22–26. Thus, miR-34 appears a key miRNA poised to integrate age-associated physiology; the precise function will reflect the diverse spatiotemporal expression and activity of distinct orthologues, the mRNA target spectrum, as well as the complexity of the adult brain and life cycle. The conservation of miR-34, coupled with in-depth comparative analysis of miR-34 expression, 3'end processing, targets and pathways in the aging process of worms, flies and mammals, makes it a tempting subject for understanding features of aging and disease susceptibility.

METHODS SUMMARY

Flies were grown in standard media at 25°C unless otherwise specified. Stock lines and GAL4 driver lines were obtained from the Drosophila Stock center at Bloomington, or are described14. Deletion of miR-34 region was made by site-specific recombination. Fly transgenics were generated by standard procedures. Flies were generated or backcrossed a minimum of 5 generations into a controlled uniform homogeneous genetic background (line 5905 (Flybase ID FBst0005905, w1118), to assure that all phenotypes were robust and not associated with variation in genetic background. In this uniform homogeneous genetic background, the lifespan of control flies is highly uniform with repetition when 150 or more individuals are used for lifespan analysis. Negative geotaxis and thermo stress were used to examine fly locomotion and stress resistance, respectively. Adult male heads were processed for paraffin sections as described21. To determine lifespan, newly eclosed males were collected and maintained at 15 flies per vial, transferred to fresh vials every two days while scored for survival. A total of 150–200 flies were used per genotype per lifespan; all experiments were repeated multiple times (See Supplemental Table 4). Lifespans were analyzed in Excel (Microsoft) and by Prism software (GraphPad) for survival curves and statistics. Techniques of molecular biology, western immunoblots and histology were standard. Fly brain mRNA was prepared using Trizol reagent for array and mRNA analysis, miRNA arrays were the miRCURY™ LNA arrays version 8.1 (Exiqon), and mRNA expression was profiled using Affymetrix Drosophila 2.0 chips (Affymetrix). The microarray data can be found in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) of NCBI through accession number GSE25009.

Methods

Genetic background

To control for background effects, and to assess significance of all effects, flies were generated in the same uniform homogeneous genetic background (line 5905 (Flybase ID FBst0005905, w1118)), or backcrossed a minimum of 5 generations into this uniform genetic background. This assured that, for all phenotypes, even modest and consistent effects were associated with the gene manipulations and not a variation in background. With these carefully controlled experiments, the lifespan of control flies was highly uniform upon repetition, when 200 or more individuals were used for lifespan analysis (see Supplemental Table 4).

miR-34 deletion mutants

Deletion of miR-34 region was made by site-specific recombination between two piggyBac insertions, using FLP-FRT mediated site-specific recombination28. The loss of any other genes in the region was then fully rescued back by genomic transgenes, so that a line selectively lacking only miR-34 was generated. Two FRT-bearing insertions, PBac[XP]d02752 and PBac[RB]Fmr1e02790, were used (Exelixis collection, Harvard University), which encompass the miR-34 region. Genetic crosses were made to combine these two transposon elements with heat-inducible FLP recombinase. After 48h of egg laying, parents were removed, and vials containing progeny were placed in a 37 °C water bath for a 1h-heat shock. Progeny flies were treated with daily 1h-heat shock, for an additional 4d. Young virgin female progeny flies were collected and crossed to males with 3rd chromosome balancers. In the subsequent generation, progeny males were used to generate additional progeny for PCR confirmation. Progeny flies bearing the deletion were positive for PCR verification, using primers from neighboring genomic DNA and ones from transposons (upstream insertion: 5’-GGTCGTGCATGACGAGATTA-3’/5’-TACTATTCCTTTCACTCGCACTTATTG-3’; downstream insertion: 5’-TCCAAGCGGCGACTGAGATG-3’/5’-GTGCGTTCGAAGAAATGATG-3’). Flies having the miR-34 region deletion were viable, and were further verified for the appropriate deletion by PCR amplification, with primers for, miR-317 (5’-CGGAAAAACGGTTTGTGTCT-3’/5’-CCCGGGAACGAGTAAACGAAATGAAAATCA-3’), miR-277 (5’-TGATTTATGGTTTTTGTTTCAGTTG-3’/5’-TTGATATCATTTCACACTATCACAAAAATTGC-3’), miR-34 (5’-ACCTTGAGCGCTTCAACTCT-3’/5’-CACTCTTTCTCGTTTGCATGG-3’) and dfmr1 (5’-CACACAGAGCTTCCCAGTGA-3’/5’-AGGCCCTCCTTTTTGACATT-3’).

Fly age-associated phenotypes

Negative geotaxis and thermo stress were used to examine fly locomotion and stress resistance, respectively. To perform negative geotaxis, groups of 15 adult male flies of indicated age were transferred into a 14 ml polystyrene round-bottom tube (Falcon), and placed in the dark for 30 min recovery. The assay was conducted in the dark, with only a red light on. Climbing ability was scored as the percentage of flies failing to climb higher than 1.5cm from the bottom of the tube, within 15 sec after gently being banged to the bottom. Three repeats were performed for each group and the result averaged. For each genotype at a given age, a minimum of 200 flies were tested. For heat sensitivity, groups of 15 adult males of indicated age were transferred into 14ml polystyrene round-bottom tubes (Falcon), then placed in a 25°C incubator for 30 min recovery. Heat stress was applied by immersing the vial containing the flies into a 37°C water bath for 1h, followed by a 30 min recovery at 25°C, then another 1h heat stress at 37°C. Flies were then transferred into regular food vials and maintained at 25°C. Dead flies were counted after 24h. To assess brain morphology, adult male heads were processed for paraffin sections as described29, and brain vacuoles were counted through continuous sections generated from each head (n=10 heads counted for each genotype).

Molecular biology

Fly genomic DNA was prepared from whole flies with the Puregene DNA purification kit (Qiagen). To generate miR-34 pUAST constructs, PCR amplification was conducted using genomic DNA as template, with primer pairs of miR-34 pUAST-I (286bp, PCR primer 5’-CCGTTACACACGACTATTCTCAAT-3’/5’-CCATCTGATACAGGTCCTACATTTTCTAAAA-3’) and miR-34 pUAST-II (936bp, PCR primer 5’-ACCTTGAGCGCTTCAACTCT-3’/5’-CACTCTTTCTCGTTTGCATGG-3’). PCR products were then ligated into the pUAST vector. miR-277/dfmr1 rescue construct was made in the pCaSpeR4 vector, which contained two parts. Part 1 was a genomic DNA fragment (7530bp) harboring the miR-277 sequence (PCR primers: 5’-GGTCGTGCATGACGAGATTA-3’/5’-GGATGTTTTGCGACCAACTT-3’), and part 2 was a genomic fragment containing dfmr1 genomic sequence, derived from the pBS WTR construct (a gift from Dr. Thomas Jongens, University of Pennsylvania30), by BamH1 and Ppum1. The miR-34 genomic rescue construct was also made in the pCaSpeR4 vector, with two parts. One was a genomic DNA fragment (6855bp) upstream of miR-277 sequence (PCR primers: 5’-GGTCGTGCATGACGAGATTA-3’/5’-GGATGCATTTTATCGTTAGGC-3’), and the other was a genomic DNA fragment (2111bp) containing miR-34 sequence (PCR primers: 5’-GCAGGAAAATGCGATAAATGA-3’/5’-TCGTTACAACATGGAAATCCTC). The resultant construct, therefore, contains miR-34 sequence, including most upstream fragment, with the exclusion of 108bp of miR-277 sequence. In addition, a modified miR-34 genomic rescue construct was made (pCaSpeR4 vector), which contains same upstream and downstream ends of the original miR-34 genomic rescue construct, with a small deletion of miR-277 mature sequence. The genomic regulation of miR-34 appears complex, as despite these standard manipulations for gene rescue, the genomic rescue expression of miR-34 and extent of phenotypic rescue of miR-34 mutants was only partial. We attempted upregulation of miR-34 with the GAL4-UAS system, including with the conditional gene switch system in adults. Upregulation of miR-34 during development in non-germline tissues (when it normally is not expressed; Supplementary Fig. 2a) was deleterious, and we were unable to upregulate miR-34 expression more robustly than with the genomic constructs.

For western immunoblots, 10 adult male heads per sample were homogenized in 50 µl of Laemmli Buffer (Bio-Rad) supplemented with 5% 2-Mercaptoethanol, heated to 95°C for 5 min and 10 µl loaded onto 4–12% Bis-Tris gels (NuPage), then transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Biorad) and blotted by standard protocols. Primary antibodies used were anti-tubulin (1:10,000, E7, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), anti-E74A (a gift of Dr. Carl Thummel, University of Utah). Secondary antibodies for immunoblots were goat anti-mouse conjugated to HRP (1:2000, Chemicon), and developed by chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham). The final image was obtained by Fuji scanner (Fujifilm).

Total RNA was isolated from 50–200 male heads per genotype, by cutting off heads with a sharp razor, then putting heads into Trizol reagent. Heads were ground by pestle, then RNA was isolated following manufacturer’s protocol (Trizol reagent, Invitrogen). 5µg RNA was used per lane. Gel running (1% agarose) and blot transfer (nylon plus) were according to recommended procedures (Northernmax, Ambion). The RNA blot was then used for hybridization following standard procedures at 68°C, with prehybridization (~ 1 h), hybridization (~ 12 h or overnight) with P32 labeled probe, washed and exposed to Phosphoimager (Amersham). RNA probes were used that were made by in vitro transcription of cDNA templates using Maxiscript-T7 in vitro transcription kit (Ambion), supplemented with P32-labeled UTP. The cDNA templates were prepared from total RNA by one-step RT-PCR (SuperScript One-Step RT-PCR with Platinum Taq, Invitrogen), with primers: E74A (5’-GTGAACGTGGTGGTGGAAC-3’/ 5’-GATAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGATGTCCATTCGCTTCTCAATG-3’); E74B (5’-CATCGCTTGTCAATGTGTCC-3’/ 5’-GATAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGACTGCGGTAATCACTGAGCTG-3’);18S rRNA loading control (5’-GATAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA-3’/ 5'-AGGGAGCCTGAGAAACGGCTACCACATCTAAGGAATCTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTATC -3’)

For small RNA northerns, total RNA was isolated from male fly heads using Trizol reagent as above. For each lane, 3µg of RNA was used, and RNA was fractionated on a 15% Tris-UREA gel (NuPage) with 1XTBE buffer. The blot transfer was performed with 0.5XTBE buffer. Prior to hybridization, the RNA blots were prehybridized with Oligohyb (Ambion), and then incubated with radioactive labeled RNA probes for ~12 h to overnight. RNA probes were used, and made by in vitro transcription of oligo templates using Maxiscript-T7 in vitro transcription kit (Ambion), supplemented with P32 -labeled UTP. Oligo DNA templates were prepared by annealing two single stranded DNA oligos into duplex (99°C 5min and cool down to room temperature). Oligos used for miR-34 (5’-GATAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA-3’/5’-AAAAAATGGCAGTGTGGTTAGCTGGTTGTGTCTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTATC-3’), miR-277 (5’-GATAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA-3’/5’-TAAATGCACTATCTGGTACGACATAAATGCACTATCTGGTACGACA TCTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTATC-3’) and 2S rRNA (5’-GATAATACGACTCACTATAGGGAGA-3’/5'-TGCTTGGACTACATATGGTTGAGGGTTGTATCTCCCTATAGTGAGTCGTATTATC-3’).

Luciferase assays were performed using standard approaches 5. Specifically, 8×104 DL1 cells were plated and bathed in 30ul of serum-free medium with 60ng of dsRNA in each well of a 96 well plate. The next day, 1.6ng of pMT-Firefly, 400ng of pMT-miR-34, and 400ng of pMT-renilla-3'UTR (E74A wild type or mutant reporters) were transfected by Effectene (Qiagen). Two days post transfection, the expression of the reporters and miR-34 was induced by CuSO4. 24h after induction, luminescence assays were performed by Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega). The miR-34 seed sequences in the 3’UTR of E74A were mutated as noted in Supplementary Figure 3, using the Quik change mutagenesis system (Stratagene). Primers to knockdown Ago1 are described5.

The miRNA-target prediction algorithms TargetScan (v5.1) 31 and PicTar (fly)32 were used to determine miR-34 target mRNA candidates.

miRNA microarray analysis

For miRNA array analysis, Iso31 flies (isogenized w1118) were used. Flies were killed by brief submersion in ethanol under CO2 anesthesia, followed by two PBS washes (Sigma). To control for circadian effects, all flies were processed between 11 am and 1 pm. Brains were removed manually and collected in an Eppendorf microcentrifuge tube stored on ice. For each miRNA microarray replicate, 200–300 brains were collected for each time point, with a ~50/50 ratio of males and females. RNA was prepared using the miRvana RNA extraction system (Ambion) yielding ~2.5µg/100 brains. RNA was eluted into 80µl of RNAse free water (Fisher Scientific, NJ) and stored at −80°C. miRNA profiling was carried out at the Penn microarray core facility using miRCURY™ LNA arrays (Exiqon) and protocols. Exiqon’s Hy3/H5-labeling kit was used (Exiqon). RNA samples were labeled with Hy3 and hybridized together with a Hy5-labeled common reference standard. The common reference standard consisted of equal amounts of RNA from brains of 3d, 30d, and 60d flies. The miRNA microarray data were analyzed at the Penn Bioinformatics Core. Raw data was imported into Gene Spring 1.0 (Agilent) and normalized using a global LOESS regression algorithm (locally weighted scatterplot smoothing). Relative expression levels were calculated as the log2 normalized signal intensity difference between the Hy3 and Hy5 intensity. Present/absent flagging was analyzed by Exiqon (Exiqon). Expression levels (fold changes) for the 30d and 60d time point were calculated relative to the 3d time point. The data sets were exported into Spotfire DecisionSite 9.0 (Tibco) for visualization and filtering.

mRNA microarray analysis

For aging microarray analysis, fly stock Iso31 was used. For miR-34 mutant microarray analysis, miR-34 null line-1 in 5905 background was used, with fly 5905 line, as control. To generate an aging profile, flies were aged to 3d, 30d and 60d, and 30–50 brains dissected per time point, per replicate, as above (50-50 males and females). For each time point, 3 replicates were conducted. For miR-34 mutant microarray analysis, time points were 3d and 20d, and for each time point, 20 brains from male flies of the appropriate genotype were used, with 5 replicates in total. Microarray hybridization and reading was performed at the Penn Microarray Core Facility. For mRNA microarrays, total RNA was reverse transcribed to ss-cDNA, followed by two PCR cycles using the Ovation RNA amplification system V2 (Ovation). Quality control on both RNA and ss-cDNA was performed using an 2100 Agilent Bioanalyzer (Quantum Analytics). The cDNA was labeled using the FL-Ovation™ cDNA Biotin Module V2 (Ovation), hybridized to Affymetrix Drosophila 2.0 chips (Affymetrix) and scanned with an Axon Instruments 4000B Scanner using GenePix Pro 6.0 image acquisition software (Molecular Devices). Affymetrix .cel (probe intensity) files were exported from GeneChip Operating Software (Affymetrix). The .cel files were imported to ArrayAssist Lite (Agilent) in which GCRMA probeset expression levels and Affymetrix absent/present/marginal flags were calculated. Statistical analysis for those genes passing the flag filter was performed using Partek Genomics Suite (Partek). The signal values were log2 transformed and a 2-way ANOVA was performed.

Transcriptional analysis of aging status

We first used the wild type to extract age-associated probesets and then compared the relative changes of these probesets in a separate set of transcriptional profiles generated for the wild type and miR-34 mutant. For transcriptional profiles of normal aged brains, the GCRMA package RMA (JZ Wu, J MacDonald, J Gentry, GCRMA: Background adjustment using sequence information, R package version 2.14) for R/Bioconductor33 was used to generate log-2 expression levels for probeset IDs from the original .cel files. Then, a linear regression model was used to compute the significance of a correlation between age and gene expression9,34. This approach assumes a linear relationship between age and log-2 expression level:

In this equation, Yij is the log-2 gene expression level of probe set i in sample j, Aj is the age for individual j. The coefficients β1i is regression coefficients reflecting the rate of change in gene expression with respect to age. Probesets with expression significantly correlated with age (p≤ 0.001 for β1i) were determined. Then the same probesets were used to estimate the relative expression in separate profiles of miR34 mutants and age-matched controls. The average levels of each individual probeset were calculated for the difference between 20d and 3d, within the same genotype (i.e. Δ20d/Δ3d) for each gene in controls and miR-34 mutants, respectively. These differences were then compared between genotypes (i.e. miR-34 mutants - controls). The significance of the difference between genotypes was analyzed using a paired Wilcoxon test. The difference between control and mutant samples in positively-correlated genes (Fig. 2d) is not by chance (p<0.0001).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. C. Thummel, T. Jongens and A. Bashirullah for reagents. We are grateful to Drs. A. Cashmore, A. Burguete, J. Kim, S. Cherry, B. Gregory, A. Gitler and the Bonini laboratory for discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. We thank X. Teng for assistance with fly paraffin section. This work was funded by the NINDS (R01-NS043578) and the Ellison Foundation (to NMB). LSW and KC are supported by a pilot grant from Penn Genome Frontiers Institute. LSW is supported by NIA (U01-AG-032984-02 and RC2-AG036528-01) and a Penn Institute on Aging pilot grant (AG010124). J.R.K. received support from NIH T32 AG00255. NMB is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Author contributions

N.L. and N.M.B. conceived and designed the project. N.L., M.L., M.A., G.J.H., J.K., and Y.Z. planned, executed and analyzed experiments. K. C. and L.S-W. performed aging computational modeling. N.L. and N.M.B. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

References

- 1.Amaducci L, Tesco G. Aging as a major risk for degenerative diseases of the central nervous system. Curr Opin Neurol. 1994;7(4):283–286. doi: 10.1097/00019052-199408000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eacker SM, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Understanding microRNAs in neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10(12):837–841. doi: 10.1038/nrn2726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bilen J, Liu N, Burnett BG, Pittman RN, Bonini NM. MicroRNA pathways modulate polyglutamine-induced neurodegeneration. Mol Cell. 2006;24(1):157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang F, et al. Dicer-1 and R3D1-L catalyze microRNA maturation in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2005;19(14):1674–1679. doi: 10.1101/gad.1334005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu N, et al. The Exoribonuclease Nibbler Controls 3'End Processing of MicroRNAs in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Han BW, Hung JH, Weng Z, Zamore PD, Ameres SL. The 3'-to-5'Exoribonuclease Nibbler Shapes the 3'Ends of MicroRNAs Bound to Drosophila Argonaute1. Curr Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.09.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chung WJ, Okamura K, Martin R, Lai EC. Endogenous RNA interference provides a somatic defense against Drosophila transposons. Curr Biol. 2008;18(11):795–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kretzschmar D, Hasan G, Sharma S, Heisenberg M, Benzer S. The swiss cheese mutant causes glial hyperwrapping and brain degeneration in Drosophila. J Neurosci. 1997;17(19):7425–7432. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07425.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao K, Chen-Plotkin AS, Plotkin JB, Wang LS. Age-correlated gene expression in normal and neurodegenerative human brain tissues. PLoS One. 2010;5(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simon AF, Shih C, Mack A, Benzer S. Steroid control of longevity in Drosophila melanogaster. Science. 2003;299(5611):1407–1410. doi: 10.1126/science.1080539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fletcher JC, Thummel CS. The Drosophila E74 gene is required for the proper stage- and tissue-specific transcription of ecdysone-regulated genes at the onset of metamorphosis. Development. 1995;121(5):1411–1421. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.5.1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fletcher JC, D'Avino PP, Thummel CS. A steroid-triggered switch in E74 transcription factor isoforms regulates the timing of secondary-response gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(9):4582–4586. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.9.4582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morimoto RI. Proteotoxic stress and inducible chaperone networks in neurodegenerative disease and aging. Genes Dev. 2008;22(11):1427–1438. doi: 10.1101/gad.1657108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warrick JM, et al. Expanded polyglutamine protein forms nuclear inclusions and causes neural degeneration in Drosophila. Cell. 1998;93(6):939–949. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81200-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirth F. Drosophila melanogaster in the study of human neurodegeneration. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2010;9(4):504–523. doi: 10.2174/187152710791556104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams GC. Pleitropy, natural selection and the evolution of senescence. Evolution. 1957;11:398–411. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirkwood TB. Understanding the odd science of aging. Cell. 2005;120(4):437–447. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boehm M, Slack F. A developmental timing microRNA and its target regulate life span in C. elegans. Science. 2005;310(5756):1954–1957. doi: 10.1126/science.1115596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Lencastre A, et al. MicroRNAs both promote and antagonize longevity in C. elegans. Curr Biol. 2010;20(24):2159–2168. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibanez-Ventoso C, et al. Modulated microRNA expression during adult lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2006;5(3):235–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bak M, et al. MicroRNA expression in the adult mouse central nervous system. RNA. 2008;14(3):432–444. doi: 10.1261/rna.783108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zovoilis A, et al. microRNA-34c is a novel target to treat dementias. EMBO J. 2011;30(20):4299–4308. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Minones-Moyano E, et al. MicroRNA profiling of Parkinson's disease brains identifies early downregulation of miR-34b/c which modulate mitochondrial function. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(15):3067–3078. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, Khanna A, Li N, Wang E. Circulatory miR34a as an RNAbased, noninvasive biomarker for brain aging. Aging (Albany NY) 2011;3(10):985–1002. doi: 10.18632/aging.100371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khanna A, Muthusamy S, Liang R, Sarojini H, Wang E. Gain of survival signaling by down-regulation of three key miRNAs in brain of calorie-restricted mice. Aging (Albany NY) 2011;3(3):223–236. doi: 10.18632/aging.100276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaughwin PM, et al. Hsa-miR-34b is a plasma-stable microRNA that is elevated in pre-manifest Huntington's disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(11):2225–2237. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang J, et al. MiR-34 modulates Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan via repressing the autophagy gene atg9. Age (Dordr) 2011 doi: 10.1007/s11357-011-9324-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parks AL, et al. Systematic generation of high-resolution deletion coverage of the Drosophila melanogaster genome. Nat Genet. 2004;36(3):288–292. doi: 10.1038/ng1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li LB, Yu Z, Teng X, Bonini NM. RNA toxicity is a component of ataxin-3 degeneration in Drosophila. Nature. 2008;453(7198):1107–1111. doi: 10.1038/nature06909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dockendorff TC, et al. Drosophila lacking dfmr1 activity show defects in circadian output and fail to maintain courtship interest. Neuron. 2002;34(6):973–984. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00724-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell. 2003;115(7):787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grun D, Wang YL, Langenberger D, Gunsalus KC, Rajewsky N. microRNA target predictions across seven Drosophila species and comparison to mammalian targets. PLoS Comput Biol. 2005;1(1):e13. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gentleman RC, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5(10):R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zahn JM, et al. Transcriptional profiling of aging in human muscle reveals a common aging signature. PLoS Genet. 2006;2(7):e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.